Global migration’s impact and opportunity

Migration is a key feature of our increasingly interconnected world . It has also become a flashpoint for debate in many countries, which underscores the importance of understanding the patterns of global migration and the economic impact that is created when people move across the world’s borders. A new report from the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), People on the move: Global migration’s impact and opportunity , aims to fill this need.

Refugees might be the face of migration in the media, but 90 percent of the world’s 247 million migrants have moved across borders voluntarily, usually for economic reasons. Voluntary migration flows are typically gradual, placing less stress on logistics and on the social fabric of destination countries than refugee flows. Most voluntary migrants are working-age adults, a characteristic that helps raise the share of the population that is economically active in destination countries.

By contrast, the remaining 10 percent are refugees and asylum seekers who have fled to another country to escape conflict and persecution. Roughly half of the world’s 24 million refugees are in the Middle East and North Africa, reflecting the dominant pattern of flight to a neighboring country. But the recent surge of arrivals in Europe has focused the developed world’s attention on this issue. A companion report, Europe’s new refugees: A road map for better integration outcomes , examines the challenges and opportunities confronting individual countries.

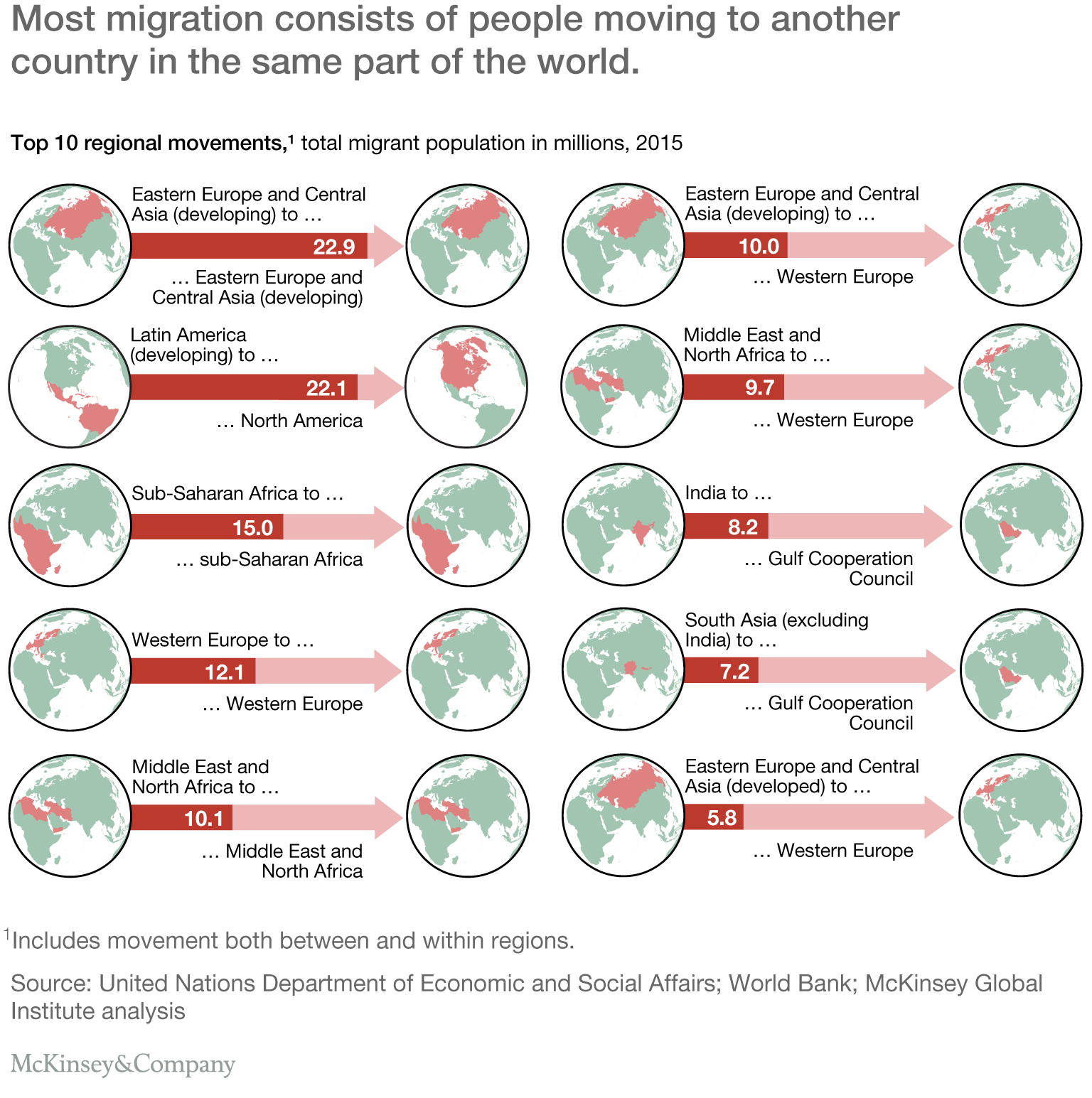

While some migrants travel long distances from their origin countries, most migration still involves people moving to neighboring countries or to countries in the same part of the world (exhibit). About half of all migrants globally have moved from developing to developed countries—indeed, this is the fastest-growing type of movement. Almost two-thirds of the world’s migrants reside in developed countries, where they often fill key occupational shortages . From 2000 to 2014, immigrants contributed 40 to 80 percent of labor-force growth in major destination countries.

Moving more labor to higher-productivity settings boosts global GDP. Migrants of all skill levels contribute to this effect, whether through innovation and entrepreneurship or through freeing up natives for higher-value work. In fact, migrants make up just 3.4 percent of the world’s population, but MGI’s research finds that they contribute nearly 10 percent of global GDP. They contributed roughly $6.7 trillion to global GDP in 2015—some $3 trillion more than they would have produced in their origin countries. Developed nations realize more than 90 percent of this effect.

Would you like to learn more about the McKinsey Global Institute ?

Employment rates are slightly lower for immigrants than for native workers in top destinations, but this varies by skill level and by region of origin. Extensive academic evidence shows that immigration does not harm native employment or wages, although there can be short-term negative effects if there is a large inflow of migrants to a small region, if migrants are close substitutes for native workers, or if the destination economy is experiencing a downturn.

Realizing the benefits of immigration hinges on how well new arrivals are integrated into their destination country’s labor market and into society. Today immigrants tend to earn 20 to 30 percent less than native-born workers. But if countries narrow that wage gap to just 5 to 10 percent by integrating immigrants more effectively across various aspects of education, housing, health, and community engagement, they could generate an additional boost of $800 billion to $1 trillion to worldwide economic output annually. This is a relatively conservative goal, but it can nevertheless produce broader positive effects, including lower poverty rates and higher overall productivity in destination economies.

People on the move: Migrant voices

A series of portraits tells migrants’ stories—part of the 'i am a migrant' campaign.

The economic, social, and civic dimensions of integration need to be addressed holistically. MGI looked at how the leading destinations perform on 18 indicators and found that no country has achieved strong integration outcomes across all of these dimensions, though some do better than others. But in destinations around the world, many stakeholders are trying new approaches. We identify more than 180 promising interventions that offer useful models for improving integration. The private sector has a central role to play in this effort—and incentives to do so. When companies participate, they stand to gain access to new markets and pools of new talent.

The stakes are high. The success or failure of integration can reverberate for many years, influencing whether second-generation immigrants become fully participating citizens who reach their full productive potential or remain in a poverty trap.

Lola Woetzel , Jacques Bughin , and James Manyika are directors of the McKinsey Global Institute, where Anu Madgavkar is a partner and Ashwin Hasyagar is a fellow; Khaled Rifai is a partner in McKinsey’s New York office, Frank Mattern is a senior partner in the Frankfurt office, and Tarek Elmasry and Amadeo Di Lodovico are senior partners in the Dubai office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

A road map for integrating Europe’s refugees

Creating a global framework for immigration

Urban world: Meeting the demographic challenge in cities

- SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

- DEVELOPMENT & SOCIETY

- PEACE & SECURITY

- HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS

- HUMAN RIGHTS

Why Migration Matters

While human mobility has been an enduring feature of our global history, it is as pertinent today as it ever was. With 232 million international migrants in the world, according to recent figures released by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), migration is one of the most important and pressing global issues of our time.

According to UNDESA, the definition of an international migrant is a person living outside of their country of birth. Migration is often driven by the search for better livelihoods and new opportunities. Indeed, global and regional social and economic inequalities are expressed most powerfully through the figure of the migrant, as one who crosses borders in search of work, education and new horizons.

Many people who migrate, however, have not necessarily chosen to do so. Forced migration is becoming ever more prevalent as a result of civil, political and religious persecution and conflict. In 2012, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that there were 10.4 million refugees in the world. There is, moreover, a growing need to understand the important relationship between environmental change and forced migration and displacement , and the experiences of stateless persons .

Crossing borders and seas involves grave risks, with many migrants not able to complete safe journeys. We can see this most starkly in the numerous tragedies involving migrants that have occurred in recent years. As borders become increasingly securitised, the proliferation of recruitment networks that endanger and profit from migrants and the increasing use of private migration management agencies in border control and security are worrying trends. This ought to make us reflect urgently on how migration is being governed in the world today and on the responsibilities of states in this regard.

Addressing the challenges

As societies become more diverse, there are both opportunities and challenges. Experiences of discrimination on the basis of one’s socio-economic, cultural or religious background continue to be commonplace. A priority will be to promote the means for intercultural dialogue and the inclusion of migrants into the economic, social and cultural lives of the societies in which they live. It is also crucial to mention the striking feminization of migration. As women now comprise 48 percent of all international migrants, efforts to promote the inclusion of migrants must also adequately address the particular experiences of female migrants across the world.

There are key ways in which the international community is addressing these challenges. The October 2013 High-Level Dialogue on International Migration and Development recognized migration as a central part of the international development agenda. Under the heading of ‘Making Migration Work’, discussions revolved around how migration contributes to global development and to poverty alleviation. They also considered how migration could benefit individuals, families, communities and states. Migration will only work for all, however, if greater commitment is shown to eliminating all forms of exploitation and discrimination that migrants experience and to ensuring that their fundamental human rights are upheld.

While the role of migrants in economic development through remittance and knowledge transfers has been acknowledged, recent debates in civil society have emphasized an understanding of migration in human development terms. As the synergies between states, policymakers, researchers and civil society organizations gain momentum, it is imperative to remember the human face of migration and to keep migrants themselves at the centre of discussions.

In order to address these pressing concerns, the United Nations University (UNU) institutes have come together to form a migration research network. The network features migration research experts from different disciplinary backgrounds who examine the complexities of migration at regional and global scales. Current research themes include: the health of migrants, migrants’ inclusion and exclusion from social and cultural life, the consequences of migration on those left behind, human security, migration and development, and the experiences of vulnerable groups such as stateless persons and forced migrants.

The aim of this network is to ensure solid collaborations and the sharing of migration-related research across the different institutes of the UNU. The unique vantage point of the UNU means that research findings will also be shared widely with policymakers and civil society organizations. The launch of the UNU Migration Network’s website promises to be an important first step in the network’s activities to put migration at the heart of research and policy agendas.

Megha Amrith

Megha Amrith is a Research Fellow at the United Nations University Institute on Globalization, Culture and Mobility in Barcelona . She holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Cambridge and researches international migration, cultural diversity and cities.

Related Articles

Climate Migration ‘a Complex Problem’

A Man Leaves His Island

Understanding the Islanders: Climate Migration in Context

How Rainfall Variability, Food Security and Migration Interact

Displaced Indigenous Malaysians Face Uncertain Future

How-to Guide for Environmental Refugees

How immigration has changed the world – for the better

Image: A migrant holds his passport and a train ticket in Freilassing, Germany September 15, 2015. REUTERS/Dominic Ebenbichler

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Ian Goldin

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Migration is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

Is immigration good or bad? Some argue that immigrants flood across borders, steal jobs, are a burden on taxpayers and threaten indigenous culture. Others say the opposite: that immigration boosts economic growth, meets skill shortages, and helps create a more dynamic society.

Evidence clearly shows that immigrants provide significant economic benefits. However, there are local and short-term economic and social costs. As with debates on trade, where protectionist instincts tend to overwhelm the longer term need for more open societies, the core role that immigrants play in economic development is often overwhelmed by defensive measures to keep immigrants out. A solution needs to be found through policies that allow the benefits to compensate for the losses.

Around the world, there are an estimated 230 million migrants, making up about 3% of the global population. This share has not changed much in the past 100 years. But as the world’s population has quadrupled, so too has the number of migrants. And since the early 1900s, the number of countries has increased from 50 to over 200. More borders mean more migrants.

Of the global annual flow of around 15 million migrants, most fit into one of four categories: economic (6 million), student (4 million), family (2 million), and refugee/asylum (3 million). There are about 20 million officially recognized refugees worldwide, with 86% of them hosted by neighbouring countries, up from 70% 10 years ago.

In the US, over a third of documented immigrants are skilled. Similar trends exist in Europe. These percentages reflect the needs of those economies. Governments that are more open to immigration assist their country’s businesses, which become more agile, adaptive and profitable in the war for talent. Governments in turn receive more revenue and citizens thrive on the dynamism that highly-skilled migrants bring.

Yet it is not only higher-skilled migrants who are vital. In the USA and elsewhere, unskilled immigrants are an essential part of the construction, agriculture and services sector.

If immigrants play such a vital role, why is there so much concern?

Some believe that immigrants take jobs and destroy economies. Evidence proves this wrong. In the United States, immigrants have been founders of companies such as Google, Intel, PayPal, eBay, and Yahoo! In fact, skilled immigrants account for over half of Silicon Valley start-ups and over half of patents, even though they make up less than 15% of the population. There have been three times as many immigrant Nobel Laureates, National Academy of Science members, and Academy Award film directors than the immigrant share of the population would predict. Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco concluded that “immigrants expand the economy’s productive capacity by stimulating investment and promoting specialization, which produces efficiency gains and boosts income per worker”.

Research on the net fiscal impact of immigration shows that immigrants contribute significantly more in taxes than the benefits and services they receive in return. According to the World Bank , increasing immigration by a margin equal to 3% of the workforce in developed countries would generate global economic gains of $356 billion. Some economists predict that if borders were completely open and workers were allowed to go where they pleased, it would produce gains as high as $39 trillion for the world economy over 25 years.

In the future, it will become even more imperative to ensure a strong labour supply augmented by foreign workers. Globally, the population is ageing. There were only 14 million people over the age of 80 living in 1950. There are well over 100 million today and current projections indicate there will be nearly 400 million people over 80 by 2050. With fertility collapsing to below replacement levels in all regions except Africa, experts are predicting rapidly rising dependency ratios and a decline in the OECD workforce from around 800 million to close to 600 million by 2050. The problem is particularly acute in North America, Europe and Japan.

There are, however, legitimate concerns about large-scale migration. The possibility of social dislocation is real. Just like globalization – a strong force for good in the world – the positive aspects are diffuse and often intangible, while the negative aspects bite hard for a small group of people.

Yes, those negative aspects must be managed. But that management must come with the recognition that migration has always been one of the most important drivers of human progress and dynamism. Immigration is good. And in the age of globalization, barriers to migration pose a threat to economic growth and sustainability. Free migration, like totally free trade, remains a utopian prospect, even though within regions (such as Europe) this has proved workable.

As John Stuart Mill forcefully argued, we need to ensure that the local and short-term social costs of immigration do not detract from their role “as one of the primary sources of progress”.

Author: Ian Goldin is Director of the Oxford Martin School and Professor of Globalization and Development at the University of Oxford. This article draws on his book Exceptional people: How migration shaped our world and will define our future , co-authored with Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan and published by Princeton University Press. Twitter: @oxmartinschool . He is participating in the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Jobs and the Future of Work .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Why companies who pay a living wage create wider societal benefits

Sanda Ojiambo

May 14, 2024

Age diversity will define the workforce of the future. Here’s why

Susan Taylor Martin

May 8, 2024

From start-ups to digital jobs: Here’s what global leaders think will drive maximum job creation

Simon Torkington

May 1, 2024

70% of workers are at risk of climate-related health hazards, says the ILO

Johnny Wood

International Workers' Day: 3 ways trade unions are driving social progress

Giannis Moschos

Policy tools for better labour outcomes

Maria Mexi and Mekhla Jha

April 30, 2024

2021 Theses Doctoral

Three Essays on International Migration

Huang, Xiaoning

Today, there are about 250 million international migrants globally, and the number is increasing each year. Immigrants have contributed to the global economy, bridged cultural and business exchanges between host and home countries, and increased ethnic, racial, social, and cultural diversity in the host societies. Immigrants have also been overgeneralized about, misunderstood, scapegoated, and discriminated against. Understanding what drives international migration, who migrate, and how immigrants fare in destination has valuable theoretical, practical, and policy implications. This dissertation consists of three essays on international immigration. The first paper aims to test a series of immigration theories by studying immigrant skill-selection into South Africa and the United States. Most of the research on the determinants of immigrant skill selection has been focusing on immigrants in the United States and other developed destination countries. However, migration has been growing much faster in recent years between developing countries. This case study offers insights into the similarities and differences of immigration theories within the contexts of international migration into South Africa and the US. This project is funded by the Hamilton Research Fellowship of Columbia School of Social Work. The second paper narrows down the focus onto Asian immigrants in the United States, studying how the skill-selection of Asian immigrants from different regions has evolved over the past four decades. Asian sending countries have experienced tremendous growth in their economy and educational infrastructure. The rapid development provides an excellent opportunity to test the theories on the associations between emigrants’ skill-selection and sending countries’ income, inequality, and education level. On the other hand, during the study period, the United States has had massive expansion employment-based immigration system, followed by cutbacks in immigration policies. I study the association between immigration patterns and these policies to draw inferences on how the changes in immigration policies have affected the skill selection of Asian immigrants. This research is funded by Columbia University Weatherhead East Asia Institute’s Dorothy Borg Research Program Dissertation Research Fellowship. The third paper centers on the less-educated immigrant groups in the US and investigates the gap in welfare use between less-educated immigrant and native households during 1995-2018, spanning periods of economic recessions and recoveries, changes in welfare policy regimes, and policies towards immigrants. I use “decomposition analysis” to study to what extend demographic factors, macroeconomic trends, and welfare and immigration policy could explain the disparities in welfare participation between immigrants and natives. This paper is co-authored with Dr. Neeraj Kaushal from Columbia School of Social Work and Dr. Julia Shu-Huah Wang from the University of Hong Kong. The work has been published in Population Research and Policy Review (doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09621-8).

Geographic Areas

- South Africa

- United States

- Social service

- Immigrants--Economic aspects

- Immigrants--Social conditions

- Race discrimination

- Immigrants--Education

More About This Work

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

- Development

- Asia and the Pacific

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Western Asia

- عربي

- 中文

- Français

- Русский

- Español

United Nations

Department of economic and social affairs desa.

- PUBLICATIONS

Global importance of migration for development

“We must guard against the adoption of protectionist and isolationist policies: history has shown us the cost of those. We must make sure that we guarantee the rights of migrants and assure them of decent lives and working conditions,” said H.E. Mr. Joseph Deiss, President of the 65th session of the United Nations General Assembly, as he opened the Informal Thematic Debate on International Migration and Development.

The one day event was hosted by Mr. Deiss on 19 May at UN Headquarters in New York. The debate discussed policies that attempt to maximize the opportunities of international migration for development and reduce its negative impacts ahead of the 2013 High-level Dialogue on Migration and Development. The first round table discussed the contribution of migrants to development and the second focused on improving international cooperation on migration and development.

Approximately 214 million people or about three per cent of the world’s population is currently living outside their countries of origin. Noting that we live in an age of mobility, a time when more people are on the move than any other time in human history, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon stressed the need to garner the positives of migration for the global good.

Migrant labor is desirable and necessary to sustain economic growth and rise out of the current recession. Migration is important for the transfer of manpower and skills and provides the needed knowledge and innovation for global growth.

In order to address the issues raised by global migration, it is necessary to improve international coordination. Mr. Abdelhamid El Jamri, Chairperson of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families explained “We need to examine issues faced by migrants in order to help in countries of countries.”

Mr. Anthony Lake, UNICEF Executive Director and Chair-in-Office of the Global Migration Group, of which UN/DESA is a member, concluded, “As we take stock and look ahead to the 2013 High-level Dialogue on International Migration and Development, it is clear that much more remains to be done. Dialogue, consultation and partnerships have never been more important and we have more to learn from each other than ever before.”

Related information

- Informal Thematic Debate on International Migration and Development

- 2015 (128)

- 2014 (136)

- 2013 (133)

- 2012 (138)

- 2011 (140)

- 2010 (68)

- Capacity Development

- Financing for Development

- Policy Analysis

- Public Administration

- Social Development

- Sustainable Development

UN DESA offers a range of issue specific newsletters. Sign Up and receive your customized newsletters.

READ DESA NEWS

- Office for ECOSOC Support and Coordination

- Division for Sustainable Development

- Population Division

- Division for Public Administration and Development Management

- Financing for Development Office

- Division for Social Policy and Development

- Statistics Division

- Development Policy and Analysis Division

- United Nations Forum on Forests

- Capacity Development Office

- DESA e-Brochure

- Civil Society

- Funds and Programmes

- Copyright |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

An Introduction to Migration Studies: The Rise and Coming of Age of a Research Field

- Open Access

- First Online: 04 June 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Peter Scholten 2 ,

- Asya Pisarevskaya 3 &

- Nathan Levy 3

Part of the book series: IMISCOE Research Series ((IMIS))

29k Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Migration studies has contributed significantly to our understanding of mobilities and migration-related diversities. It has developed a distinct body of knowledge on why people migrate, how migration takes place, and what the consequences are of migration in a broad sense, both for migrants themselves and for societies involved in migration. As a broadly-based research field, migration studies has evolved at the crossroads of a variety of disciplines. This includes disciplines such as sociology, political science, anthropology, geography, law and economics, but increasingly it expands to a broader pool of disciplines also including health studies, development studies, governance studies and many more, building on insights from these disciplines.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Changing Perspectives on Migration History and Research in Switzerland: An Introduction

15 Internal Migration

Introduction: Contemporary Insights on Migration and Population Distribution

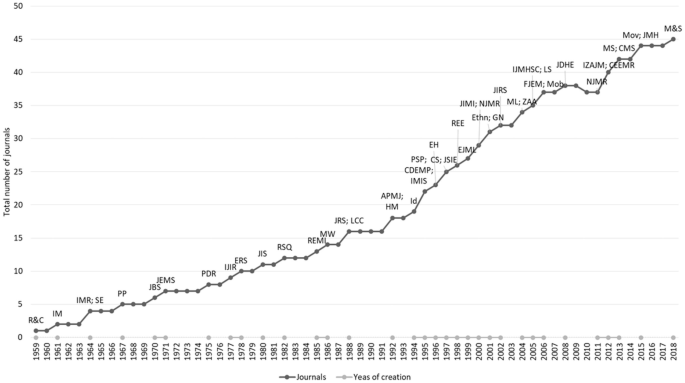

Migration is itself in no way a new phenomenon; but the specific and interdisciplinary study of migration is relatively recent. Although the genesis of migration studies goes back to studies in the early twentieth century, it was only by the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century that the number of specialised master programmes in migration studies increased, that the number of journal outlets grew significantly, that numerous specialised research groups and institutes emerged all over the world, and that in broader academia migration studies was recognised as a distinct research field in its own right. By 2018 there were at least 45 specialised journals in migration studies (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , p. 462). The field has developed its own international research networks, such as IMISCOE (International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe), NOMRA (Network of Migration Research on Africa), and the global more policy-oriented network Metropolis. Students at an increasingly broad range of universities can study dedicated programs as well as courses on migration studies. Slowly but gradually the field is also globalising beyond its European and North American roots.

Migration studies is a research field, which means that it is not a discipline in itself with a core body of knowledge that applies to various topics, but an area of studies that focus on a specific topic while building on insights from across various disciplines. It has clear roots in particular in economics, geography, anthropology and sociology. However, when looking at migration publications and conferences today, the disciplinary diversity of the field has increased significantly, for instancing bringing important contributions from and to political sciences, law, demography, cultural studies, languages, history, health studies and many more. It is hard to imagine a discipline to which migration studies is not relevant; for instance, even for engineering studies, migration has become a topic of importance when focusing on the role that social media play as migration infrastructures. Beyond being multidisciplinary (combining insights from various disciplines), the field has become increasing interdisciplinary (with its own approach that combines aspects from various disciplines) or even transdisciplinary (with an approach that systematically integrates knowledge and methods from various disciplines).

1 A Pluralist Perspective on Migration Studies

Migration studies is a broad and diverse research field that covers many different topics, ranging from the economics of migration to studies of race and ethnicity. As with many research fields, the boundaries of the field cannot be demarcated very clearly. However, this diversity does also involve a fair degree of fragmentation in the field. For instance, the field features numerous sub-fields of study, such as refugee studies, multicultural studies, race studies, diversity studies, etc. In fact, there are many networks and conferences within the field with a specific focus, for instance, on migration and development. So, the field of migration studies also encompasses, in itself, a broad range of subfields.

This diversity is not only reflected in the topics covered by migration studies, but also in theoretical and methodological approaches. It is an inherently pluralistic field, bringing often fundamentally different theoretical perspectives on key topics such as the root causes of integration. It brings very different methods, for instance ranging from ethnographic fieldwork with specific migrant communities to large-n quantitative analyses of the relation between economics and migration.

Therefore, this book is an effort to capture and reflect on this pluralistic character of field. It resists the temptation to bring together a ‘state of the art’ of knowledge on topics, raising the illusion that there is perhaps a high degree of knowledge consensus. Rather, we aim to bring to the foreground the key theoretical and methodological discussions within the field, and let the reader appreciate the diversity and richness of the field.

However, the book will also discuss how this pluralism can complicate discussions within the field based on very basic concepts. Migration studies stands out from most other research fields in terms of a relatively high degree of contestation of some of its most basic concepts. Examples include terms as ‘integration’, ‘multiculturalism’, ‘cohesion’ but perhaps most pertinent also the basic concept of ‘migration.’ Many of the field’s basic concepts can be defined as essentially contested concepts. Without presuming to bring these conceptual discussions to a close, this book does bring an effort to map and understand these discussions, aiming to prevent conceptual divides from leading to fragmentation in the field.

This conceptual contestation reflects broader points on how the field has evolved. Various studies have shown that the field’s development in various countries and at various moments has been spurred by a policy context in which migration was problematised. Many governments revealed a clear interest in research that could help governments control migration and promote the ‘integration’ of migrants into their nation-states (DeWind, 2000 ). The field’s strong policy relevance also led to a powerful dynamic of coproduction in specific concepts such as ‘integration’ or ‘migrant.’ At the same time, there is also clear critical self-reflection in the field on such developments, and on how to promote more systematic theory building in migration studies. This increase of reflexivity can be taken as a sign of the coming of age of migration studies as a self-critical and self-conscious research field.

An introduction to migration studies will need to combine a systematic approach to mapping the field with a strong historical awareness of how the field has developed and how specific topics, concepts and methods have emerged. Therefore, in this chapter, we will do just that. We will start with a historical analysis of how the field emerged and evolved, in an effort to show how the field became so diverse and what may have been critical junctures in the development of the field. Subsequently, we will try to define what is migration studies, by a systematic approach towards mapping the pluralism of the field without losing grip of what keeps together the field of migration studies. Therefore, rather than providing one sharp definition of migration studies, we will map that parts that together are considered to constitute migration studies. Finally, we will map the current state of the research field.

To provide a comprehensive overview of such a pluralist and complex field of study, we employ a variety of methods. Qualitative historical analysis of key works that shaped the formation and development of the field over the years is combined with novel bibliometric methods to give a birds-eye view of the structure of the field in terms of volume of publications, internationalisation and epistemic communities of scholarship on migration. The bibliometric analysis presented in this chapter is based on our previous articles, in which we either, used Scopus data from 40 key journals (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , or a complex key-word query to harvest meta-data of relevant publications from Web of Science (Levy et al., 2020 ). Both these approaches to meta-data collection were created and reviewed with the help of multiple experts of migration studies. You can consult the original publications for more details. Our meta-data contained information on authors, years of publication, journals, titles, and abstracts of articles and books, as well as reference lists, i.e. works that were cited by each document in the dataset.

In this chapter you will see the findings from these analyses, revealing the growth trends of migration specific journals, and yearly numbers of articles published on migration-related topics, number and geographical distribution of international co-authorships, as well as referencing patterns of books and articles – the “co-citation analysis”. The colourful network graphs you will see later in the chapter, reveal links between scholars, whose writings are mentioned together in one reference list. When authors are often mentioned together in the publications of other scientists, it means that their ideas are part of a common conversation. The works of the most-cited authors in different parts of the co-citation networks give us an understanding of which topics they specialise in, which methods they use in their research, and also within which disciplinary traditions they work. All in all, co-citation analysis provides an insight on the conceptual development of epistemic communities with their distinct paradigms, methods and thematic foci.

In addition, we bring in some findings from the Migration Research Hub, which hosts an unprecedented number of articles, book chapters, reports, dissertation relevant to the field. All these items are brought together with the help of IT technologies, integration with different databases such as Dimensions, ORCID, Crossref, and Web of Science, as well as submitted by the authors themselves. At the end of 2020, this database contains around 90,000 of items categorised into the taxonomy of migration studies, which will be presented below.

2 What Is Migration Studies?

The historical development of migration studies, as described in the next section, reveals the plurality of the research field. Various efforts to come up with a definition of the field therefore also reflect this plurality. For instance, King ( 2012 ) speaks of migration studies as encompassing ‘all types of international and internal migration, migrants, and migration-related diversities’. This builds on Cohen’s ( 1996 , p. xi–xii) nine conceptual ‘dyads’ in the field. Many of these have since been problematised – answering Cohen’s own call for critical and systematic considerations – but they nonetheless provide a skeletal overview of the field as it is broadly understood and unfolded in this book and in the taxonomy on which it is based:

Individual vs. contextual reasons to migrate

Rate vs. incidence

Internal vs. international migration

Temporary vs. permanent migration

Settler vs. labour migration

Planned vs. flight migration

Economic migrants vs. political refugees

Illegal vs. legal migration

Push vs. pull factors

Therefore, the taxonomy provides the topical structure—elaborated below—by which we approach this book. We do not aim to provide a be-all and end-all definition of migration studies but rather seek to capture its inherent plurality by bringing together chapters which provide a state-of-the-art of different meta-topics within the field.

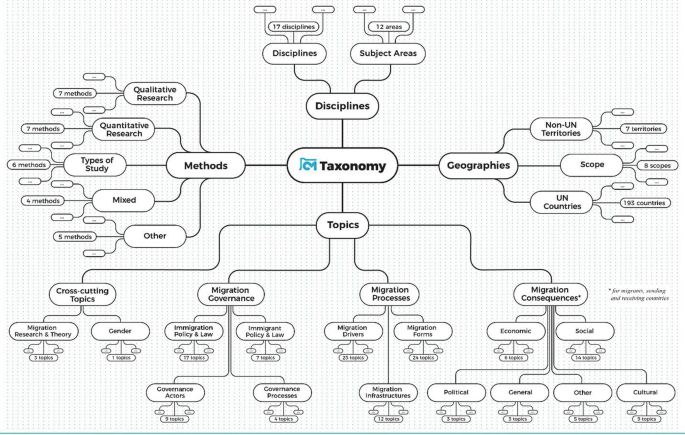

The taxonomy of migration studies was developed as part of a broader research project, led by IMISCOE, from 2018 to 2020 aimed at comprehensively taking stock of and providing an index for the field (see the Migration Research Hub on www.migrationresearch.com ). It was a community endeavour, involving contributors from multiple methodological, disciplinary, and geographical backgrounds at several stages from beginning to end.

It was built through a combination of two methods. First, the taxonomy is based on a large-scale computer-based inductive analysis of a vast number—over 23,000—of journal articles, chapters, and books from the field of migration studies. This led to an empirical clustering of topics addressed within the dataset, as identified empirically in terms of keywords that tend to go together within specific publications.

Secondly, this empirical clustering was combined with a deductive approach with the aim of giving logical structure to the inductively developed topics. Engaging, at this stage, with several migration scholars with specific expertise facilitated a theory-driven expansion of the taxonomy towards what it is today, with its hierarchical categorisation not only of topics and sub-categories of topics, but also of methods, disciplines, and geographical focuses (see Fig. 1.1 below).

The structure of the taxonomy of migration studies

In terms of its content, the taxonomy that has been developed distinguishes various meta-topics within migration studies. These include:

Why do people migrate ? This involves a variety of root causes of migration, or migration drivers.

How do people migrate ? This includes a discussion of migration trajectories but also infrastructures of migration.

What forms of migration can be distinguished ? This involves an analytical distinction of a variety of migration forms

What are major consequences of migration , and whom do these consequences concern? This includes a variety of contributions on the broader consequences of migration, including migration-related diversities, ethnicity, race, the relation between migration and the city, the relation between migration and cities, gendered aspects of migration, and migration and development.

How can migration be governed ? This part will cover research on migration policies and broader policies on migration-related diversities, as well as the relation between migration and citizenship.

What methods are used in migration studies ?

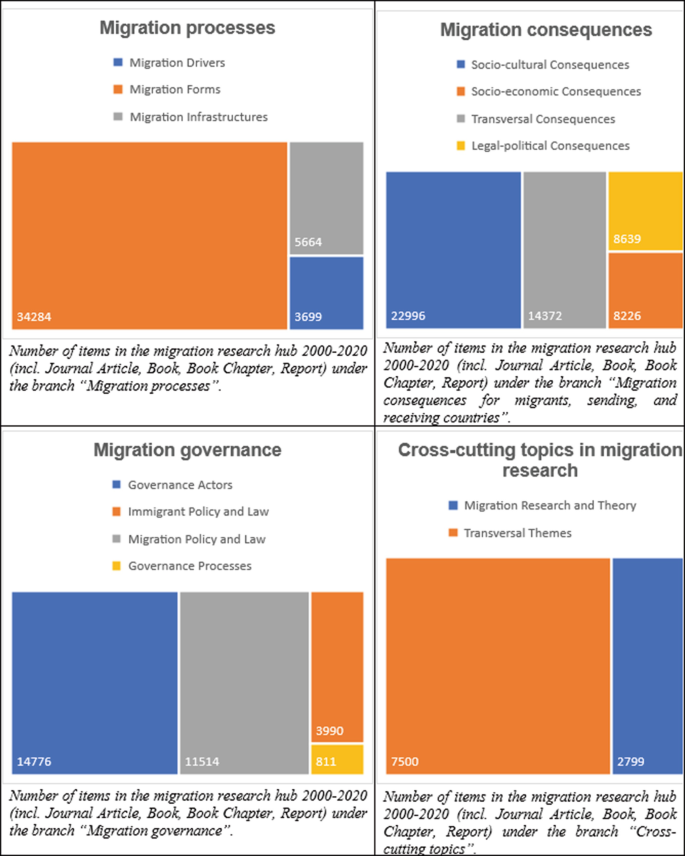

All the topics in the taxonomy are grouped into several branches: Migration processes, Migration Consequences, Migration governance and Cross-cutting. In Fig. 1.2 below you can see how many journal articles, books, book chapters and reports can be found in the migration research hub just for the period of the last 20 years. The number of items belonging to each theme can vary significantly, because some of them are broader than others. Broader themes can be related to larger numbers of items, for instance ‘migration forms’ is very broad, because it includes many types and forms of migration on which scientific research in this field chooses to focus on. On the contrary, the theme of ‘governance processes’ is narrower because less studies are concerned with specific processes of migration management, such as criminalisation, externalisation or implementation.

Distribution of taxonomy branches in the Migration Research Hub

The various chapters in this book can of course never fully represent the full scope of the field. Therefore, the chapters will include various interactive links with the broader literature. This literature is made accessible via the Migration Research Hub, which aims to represent the full scope of migration studies. The Hub is based on the taxonomy and provides a full overview of relevant literature (articles, chapters, books, reports, policy briefs) per taxonomy item. This not only includes works published in migration journals or migration books, but also a broader range of publications, such as disciplinary journals.

Because the Hub is being constantly updated, the taxonomy—along with how we approach the question of ‘what is migration studies?’ in this book—is interactive; it is not dogmatic, but reflexive. As theory develops, new topics and nomenclature emerge. In fact, several topics have been added and some topics have been renamed since “Taxonomy 1.0” was launched in 2018. In this way, the taxonomy is not a fixed entity, but constantly evolving, as a reflection of the field itself.

3 The Historical Development of Migration Studies

3.1 an historical perspective on “migration studies”.

A pluralist perspective on an evolving research field, therefore, cannot rely on one single definition of what constitutes that research field. Instead, a historical perspective can shed light on how “migration studies” has developed. Therefore, we use this introductory chapter to outline the genesis and emergence of what is nowadays considered to be the field of migration studies. This historical perspective will also rely on various earlier efforts to map the development of the field, which have often had a significant influence on what came to be considered “ migration studies ”.

3.2 Genesis of Migration Studies

Migration studies is often recognised as having originated in the work of geographer Ernst Ravenstein in the 1880s, and his 11 Laws of Migration ( 1885 ). These laws were the first effort towards theorising why (internal) migration takes place and what different dynamics of mobility look like, related, for instance, to what happens to the sending context after migrants leave, or differing tendencies between men and women to migrate. Ravenstein’s work provided the foundation for early, primarily economic, approaches to the study of migration, or, more specifically, internal or domestic migration (see Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 ; Massey et al., 1998 ).

The study of international migration and migrants can perhaps be traced back to Znaniecki and Thomas’ ( 1927 ) work on Polish migration to Europe and America. Along with Ravenstein’s Laws , most scholars consider these volumes to mark the genesis of migration studies.

The Polish Peasant and the Chicago School

The Polish Peasant in Europe and America —written by Florian Znaniecki & William Thomas, and first published between 1918 and 1920—contains an in-depth analysis of the lives of Polish migrant families. Poles formed the biggest immigrant group in America at this time. Thomas and Znaniecki’s work was not only seminal for migration research, but for the wider discipline of sociology. Indeed, their colleagues in the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago, such as Robert Park, had a profound impact on the discipline with their groundbreaking empirical studies of race and ethnic relations (Bulmer, 1986 ; Bommes & Morawska, 2005 ).

Greenwood and Hunt ( 2003 ) provide a helpful overview of the early decades of migration research, albeit through a primarily economic disciplinary lens, with particular focus on America and the UK. According to them, migration research “took off” in the 1930s, catalysed by two societal forces—urbanisation and the Great Depression—and the increased diversity those forces generated. To illustrate this point, they cite the bibliographies collated by Dorothy Thomas ( 1938 ) which listed nearly 200 publications (119 from the USA and UK, 72 from Germany), many of which focused on migration in relation to those two societal forces, in what was already regarded as a “broadly based field of study” (Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 , p. 4).

Prior to Thomas’ bibliography, early indications of the institutionalisation of migration research came in the US, with the establishment of the Social Science Research Council’s Committee on Scientific Aspects of Human Migration (see DeWind, 2000 ). This led to the publication of Thornthwaite’s overview of Internal Migration in the United States ( 1934 ) and one of the first efforts to study migration policymaking, Goodrich et al’s Migration and Economic Opportunity ( 1936 ).

In the case of the UK in the 1930s, Greenwood and Hunt observe an emphasis on establishing formal causal models, inspired by Ravenstein’s Laws . The work of Makower et al. ( 1938 , 1939 , 1940 ), which, like Goodrich, focused on the relationship of migration and unemployment, is highlighted by Greenwood and Hunt as seminal in this regard. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics regards Makower and Marschak as having made a “pioneering contribution” to our understanding of labour mobility (see also the several taxonomy topics dealing with labour).

3.3 The Establishment of a Plural Field of Migration Studies (1950s–1980s)

Migration research began to formalise and expand in the 1950s and 1960s (Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 ; Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ). A noteworthy turning point for the field was the debate around assimilation which gathered pace throughout the 1950s and is perhaps most notably exemplified by Gordon’s ( 1964 ) typology of this concept.

Gordon’s Assimilation Typology and the Problematisation of Integration

Assimilation, integration, acculturation, and the question of how migrants adapt and are incorporated into a host society (and vice versa), has long been a prominent topic in migration studies.

Gordon ( 1964 ) argued that assimilation was composed of seven aspects of identification with the host society: cultural, structural, martial, identificational, behavioural, attitudinal, and civic. His research marked the beginning of hundreds of publications on this question of how migrants and host societies adapt. The broader discussions with which Gordon interacted evolved into one of the major debates in migration studies.

By the 1990s, understandings of assimilation evolved in several ways. Some argued that process was context- or group-dependent (see Shibutani & Kwan, 1965 ; Alba & Nee, 1997 ). Others recognised that there was not merely one type nor indeed one direction of integration (Berry, 1997 ).

The concept itself has been increasingly problematised since the turn of the century. One prominent example of this is Favell ( 2003 ). Favell’s main argument was that integration as a normative policy goal structured research on migration in Western Europe. Up until then, migration research had reproduced what he saw as nation-state-centred power structures. It is worth reading this alongside Wimmer and Glick Schiller (2003) to situate it in broader contemporary debates, but there is plenty more to read on this topic.

For more on literature around this topic, see Chaps. 19 , 20 , and 21 of this book.

Indeed, these debates and discussions were emblematic of wider shifts in approaches to the study of migration. The first of these was towards the study of international (as opposed to internal) migration in the light of post-War economic dynamics, which also established a split in approaches to migration research that has lasted several decades (see King & Skeldon, 2010 ). The second shift was towards the study of ethnic and race relations, which continued into the 1970s, and was induced by the civil rights movements of these decades (Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ). These two shifts are reflected in the establishment of some of the earliest journals with a migration and diversity focus in the 1960s—the establishment of journals being an indicator of institutionalisation—as represented in Fig. 1.3 . Among these are journals that continue to be prominent in the field, such as International Migration (1961-), International Migration Review (1964-), and, later, the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (1970-) and Ethnic & Racial Studies (1978-).

Number of journals focused on migration and migration-related diversity (1959–2018). (Source: Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 , p. 462) ( R&C Race & Class, IM International Migration, IMR International Migration Review, SE Studi Emigrazione, PP Patterns of Prejudice, JBS Journal of Black Studies, JEMS Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, PDR Population and Development Review, IJIR International Journal of Intercultural Relations, ERS Ethnic & Racial Studies, JIS Journal of Intercultural Studies, RSQ Refugee Survey Quarterly, REMI Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, MW Migration World, JRS Journal of Refugee Studies, LCC Language, Culture, and Curriculum, APMJ Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, HM Hommes et Migrations, Id . Identities, PSP Population, Space, and Place, CDEMP Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, IMIS IMIS-Beitrage, EH Ethnicity & Health, CS Citizenship Studies, JSIE Journal of Studies in International Education, REE Race, Ethnicity, and Education, EJML European Journal of Migration and Law, JIMI Journal of International Migration and Integration, NJMR Norwegian Journal of Migration Research, Ethn . Ethnicities, GN Global Networks, JIRS Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, ML Migration Letters, ZAA Zeitschrift für Ausländerrecht und Ausländerpolitik, IJMHSC International Journal of Migration, Health, and Social Care, LS Latino Studies, FJEM Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration, Mob . Mobilities, JDHE Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, NJMR Nordic Journal of Migration Research (merger of NJMR and FJEM), IZAJM IZA Journal of Migration, CEEMR Central and Eastern European Migration Review, MS Migration Studies, CMS Comparative Migration Studies, Mov . Movements, JMH Journal of Migration History, M&S Migration & Society. For more journals publishing in migration studies, see migrationresearch.com )

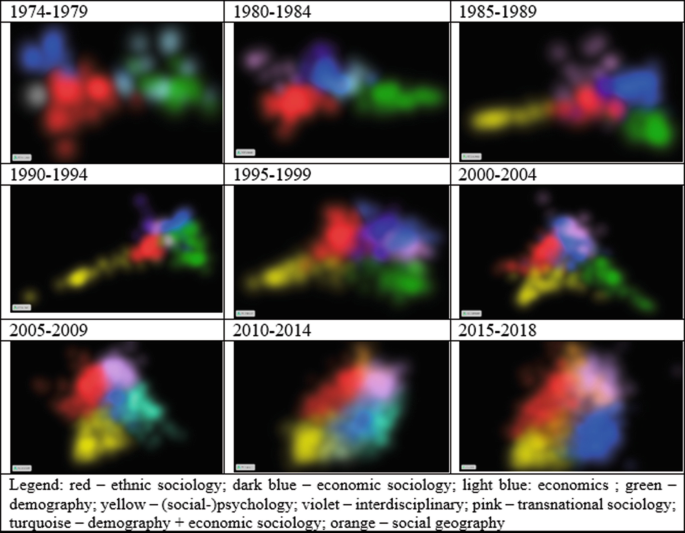

By the 1970s, although several new journals of migration studies had emerged and the field was maturing in terms of theory-building, there remained a lack of interdisciplinary “synthesis” (Kritz et al., 1981 ; King, 2012 ). This is reflected in the research of Levy et al. ( 2020 ). Based on citation data showing who migration researchers cited over the years, Fig. 1.4 maps the embryo-like development of migration studies every half-decade from 1975 to the present day. In the early decades it shows distinct “epistemic communities” (represented by colours) clustered together based on disciplines in migration research. For example, the earlier decades show economists focused on development (sky blue); economic sociologists analysing the labour market behaviour of migrants (royal blue); demographers (green); and sociologists studying the assimilation topic (red) mentioned above. By the late 1980s, a new cluster of social psychologists (yellow) emerged, with a combination of demographers and economists clustering (pink) in the 1990s. The figure shows an increasing coherence to the field since then, as the next section elaborates, but the 1970s and 1980s was a period of disciplinary differentiation within migration studies.

Co-citation clusters of authors cited in migration studies literature 1975–2018. (From Levy et al., 2020 , p. 18)

Although the field may not have been interdisciplinary in the 1980s, it was indeed multi disciplinary, and research was being conducted in more and more countries: This period entailed a “veritable boom” of contributions to migration research from several disciplines, according to Pedraza-Bailey ( 1990 ), along with a degree of internationalisation, in terms of European scholarship “catching up” with hitherto dominant North American publications, according to Bommes & Morawska, ( 2005 ). English-language migration research was still, however, dominated by institutes based in the global North and the ‘West’.

Interdisciplinarity and Internationalisation in Migration Studies: Key Readings

There have been several publications dealing with the development of migration studies over the years. These readings identify some of the key points related to interdisciplinarity in the field, and how the field has evolved internationally.

Brettell, C. B., & Hollifield, J. F. (2000). Migration theory: Talking across disciplines (1st ed.). Abingdon: Routledge; 2 nd ed. (2008); 3 rd ed. (2015).

Talking Across Disciplines has been used as a standard textbook in migration studies for several years. It represents the first effort towards highlighting the key ideas of the multiple disciplines in the field. It offers an introduction to the contributions these disciplines, as well as critical reflections on how those disciplines have interacted.

Bommes, M., & Morawska, E. (2005). International migration research: Constructions, omissions and the promises of Interdisciplinarity. Farnham: Ashgate.

International Migration Research is one of the first attempts to explore and synthesise migration studies from an interdisciplinary perspective. In this book, scholars from multiple disciplines provide a state of the art of the field which illuminates the contrasts between how these disciplines approach migration studies. It is one of the first works in which migration studies is understood to be an institutionalised field of study.

Thränhardt, D., & Bommes, M. (2010). National Paradigms of migration research. Osnabrück: V&R.

In this book, readers are introduced to the idea that migration studies developed as a policy-driven field in several countries in the twentieth century. Not only did this entail diverse policy priorities, but also diverse “paradigms” of knowledge production in terms of terminology, concepts, and measures. This diversity reflects different national science policies. There are chapters reflecting on these processes from multiple continents, and from both “old” and “new” immigration countries.

In the decades before the 1990s—with a heavy reliance on census and demographic data—quantitative research abounded in migration studies (Greenwood & Hunt, 2003 ). But by the beginning of the 1990s, a “qualitative turn”, linked more broadly to the “cultural turn” in social sciences, had taken place (King, 2012 ). In other words, migration studies broadly shifted from migration per se, to migrants. King notes the example of geographical research: “human geography research on migration switched from quantitatively inclined population geography to qualitatively minded cultural geographers […] this epistemological shift did not so much re-make theories of the causes of migration as enrich our understanding of the migrant experience ” (King, 2012 , p. 24). Indeed, this is also reflected in how Pedraza-Bailey ( 1990 , p. 49) mapped migration research by the end of the 1980s into two main categories: (i) the migration process itself and (ii) the (subjective) processes that follow migration.

Even though it is clear that migration studies is made up of multiple communities—we have already made the case for its pluralist composition—it is worth re-emphasising this development through the changing shape and structure of the ‘embryos’ in Fig. 1.4 above. The positioning of the clusters relative to each other denotes the extent to which different epistemic communities cited the same research, while the roundness of the map denotes how the field can be considered an integrated whole. We clearly see that in the period 1975–1979, the disciplinary clusters were dispersed, with loose linkages between one another. In the 1980s through to the mid-1990s, while some interdisciplinarity was emerging, several clusters, such as demographers and psychologists, were working largely within their own disciplines. In other words, in the 1970s and 1980s, authors working on migration referred to and were cited by other scholars primarily within their own disciplinary traditions. In this time, although a few migration journals had been established, this number was small compared to today. Without many scientific journals specialised in their topic, migration scholars were largely reading and publishing in disciplinary journals. By today—particularly in Europe—this has changed, as the increasing roundness of the maps demonstrate and as the rest of this chapter substantiates.

3.4 Expansion of Migration Studies Since the Turn of the Century

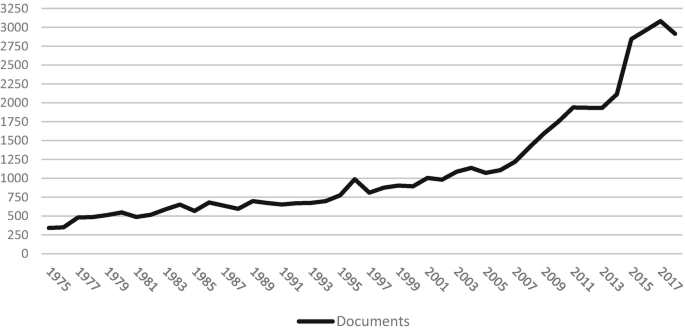

In the 2000s the expansion of migration studies accelerated further (see Fig. 1.5 ). In 1975, there were just under 350 articles published on migration; there were 900 published in 2000; in 2017, over 3000 articles were published. This growth not only involved a diversification of the field, but also various critical conceptual developments and the rise of an increasingly self-critical approach to migration studies. One of these critical developments involved a move beyond a strong focus on the national dimension of migration and diversities, for example in terms of understanding migration as international migration, on integration as a phenomenon only within nation-states, and on migrants as either being connected to the ‘home’ or ‘host’ society.

Number of articles, per year, in migration studies dataset based on advanced query of Web of Science for Migration Research Hub, 12 March 2019. (Based on Levy et al., 2020 , p. 8)

Several key publications marked this important turn. Wimmer and Glick-Schiller ( 2002 ) refer to “ methodological nationalism ” and critique the notion of taking the nation-state as a given as if it were a natural entity. In fact, for Wimmer and Glick Schiller, this way of understanding reality helps contribute to nation-state building more than it enhances scientific knowledge. In a similar contribution, Favell ( 2003 ) critiques the concept of ‘integration’ as naturalising the nation-state in relation to migration. Favell’s main argument was that integration as a normative policy goal structured research on migration in Western Europe. Up until then, migration research had reproduced what he saw as nation-state-centred power structures. Thranhardt and Bommes ( 2010 ) further substantiate this point by showing empirically how migration studies developed within distinct national context leading to the reification of distinct national models of integration/migration.

Where did this turn beyond methodological nationalism lead to? Several important trends can be defined in the literature. One involves the rise of perspectives that go beyond nation-states, such as transnationalist (Faist 2000 , Vertovec 2009 ) and postnationalist (Soysal & Soyland, 1994 ) perspectives. Such perspectives have helped reveal how migration and migrant communities can also be shaped in ways that reach beyond nation-states, such as in transnational communities that connect communities from across various countries or in the notion of universal personhood that defines the position of migrants regardless of the state where they are from or where they reside.

Another perspective takes migration studies rather to the local (regional, urban, or neighbourhood) level of migration and diversity. Zapata-Barrero et al. speak in this regard of the local turn in migration studies (2010). They show how migration-related diversities take shape in specific local settings, such as cities or even neighbourhoods, in ways that cannot be understood from the traditional notion of distinct national models.

Also, in the study of migration itself, an important trend can be identified since the 2000s. Rather than focusing on migration as a phenomenon where someone leaves one country to settle in another, the so-called “mobility turn” (Boswell & Geddes, 2010 ) calls for a better comprehension of the variation in mobility patterns. This includes for instance variation in temporalities of migration (temporary, permanent, circular), but also in the frequency of migration, types of migration, etc. In this book we will address such mobilities in the forms of different types of migration, frequencies and temporalities by discussing very different migration forms .

3.5 Growing Self-Critical Reflection in Migration Studies

Since the 2000s, there has also been a growing reflexive and self-critical approach within migration studies. Studies like those of Wimmer and Glick-Schiller, Favell, and Dahinden are clear illustrations of this growing conceptual self-consciousness. The field of migration studies has itself become an object of critical reflection. In the context of this book, we take this as a signal of the coming of age of migration studies.

This critical reflection touches upon a variety of issues in the field. One is how the field has conceptualised ethnicity, which was criticised as “ethnic lensing” (Glick Schiller & Çağlar, 2009 ). This would involve an inherent tendency to connect and problematise a broad range of issues with ethnicity, such as studies on how ethnic communities do on the labour market or the role that ethnicity plays in policies. The core argument to move beyond ethnic lensing is that focusing only on ethnicity risks defying social complexity and the importance of intersectionalities between ethnicity and, for instance, class, citizenship, education, location, cultural, or political disposition, etc. Dahinden ( 2016 ) calls in this context for a “ de-migrantisation ” of migration studies to avoid the naturalisation of migrants in relation to all sorts of issues and problems. Vertovec ( 2007 ) develops the concept “ super-diversity ” in this context to capture the social complexity of migration-related diversities.

Another strand of critical reflection concerns the field’s relationship to policymaking . Studies like those by Scholten et al. ( 2015 ) and Ruhs et al. ( 2019 ) offer critical reflection on the role that the relationship between migration studies and broader policy settings has played in the conceptual and methodological development of the field. On the one hand, the evolution of the field has been spurred on in its policy relevance, for instance in research on migration management or ‘migrant integration’. This relationship has contributed to the co-production of knowledge and key concepts, such as ‘integration’, and impeded the critical and independent development of the field. On the other hand, the field also leaves important gaps in research-policy relations, leaving important areas of knowledge production hardly connected to knowledge utilisation. Such studies have raised awareness of the necessity of research-policy relations for the societal impact of the field, while also problematising the nature of research-policy relations and their impact on the development of the field itself.

Finally, also in the context of growing public awareness on racism, the field has increasingly become self-reflexive in terms of how it deals with issues of discrimination and racism . This includes a growing awareness of institutional racism in the field itself, such as in institutes or training programs. Besides contributing to the broader field, there has been an increase of instances where institutes revise their own management and procedures in order to enhance racial justice. This includes participation of scholars from the global south, but also a proliferation of diversity policies in the field. At the same time, criticism remains on the extent to which the field has acknowledged issues of racial justice, for instance in studies on integration, migration management, or social cohesion.

4 Mapping Migration Studies Today

4.1 co-citation communities.

Nowadays, migration studies has become a more interdisciplinary field. In the last 15 years, as the “embryo” development in Fig. 1.4 shows, it became more oval-shaped without sharp “tails”. This form indicates a cross-disciplinary osmosis ; a growing interlinkage of epistemic communities. Co-referencing of authors from different disciplinary orientations became more common in the twenty-first century. Such developments can be attributed, on one hand, to the rapid digitisation of libraries and journals, as well as the multiplication of migration-focused journals, which accepted relevant contributions to discussion on migration, no matter the discipline. On the other hand, interdisciplinary endeavours were encouraged externally, for instance via grants (see European Union, 2016) and interdisciplinary master programmes created in various universities. It became fashionable to work at the intersection of disciplines, to an extent that nowadays it is often difficult to determine the disciplinary origin of a publication about migration. Whether such developments have yielded any theoretical or empirical breakthroughs is yet to be seen. In any case, it is clear that migration studies moved from being a multi-disciplinary field (with few connections between them) to an interdisciplinary field (with more connections between multiple disciplines) (Levy et al., 2020 ).

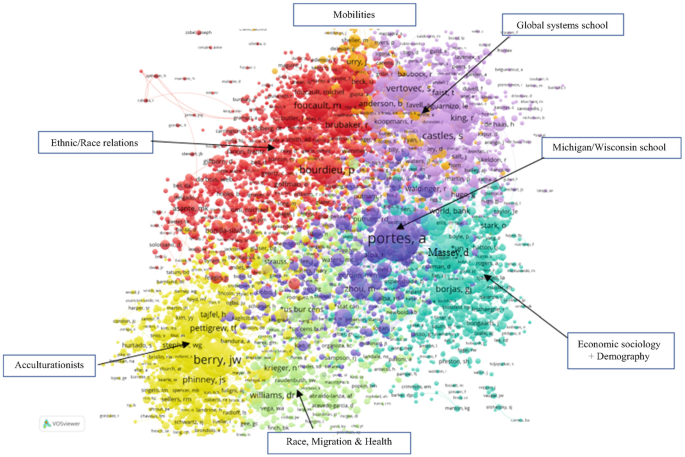

Let us now dive into the most recent co-citation clusters. Such clusters are, of course, not only categorised in terms of disciplines. They also have certain topical focuses. Figure 1.6 below zooms in to the data from Fig. 1.4 and shows the co-citation network in the period 2005–2014 in more detail. We can see seven different groups of migration scholarship that are nevertheless rather interlinked, as the oval shape of the network indicates. At 1 o’clock we can see the cluster we have elsewhere called the “Global systems school”, which has developed around such scholars as Vertovec, Soysal, Levitt, Favell, Faist, and Glick-Schiller, who introduced and developed the concept of transnationalism since the late 1990s. Contrasting with longstanding conventions of looking at migration as having an ‘endpoint’ in the countries of reception, they developed a different view of migration as a global, on-going, and dynamic process impacting receiving as well as sending societies, along with the identities, belonging, and ‘sense of home’ of migrants themselves. Nowadays, this cluster includes a very diverse group of scholars with different thematic focuses, such as the migration-development nexus (see also Chap. 18 , this volume) including de Haas, Carling, and Castles; prominent scholars on Asian migration, such as Ong and Yeoh; and many others, Guarnizo, King, Anderson, Sassen, Joppke and Baubock. Yet, the fact that they all belong to one cluster, proves that their work has been cited in the same reference lists, thus constituting an interlinked conversation on migration as global phenomenon.

Co-citation map of authors with 10+ citations in migration research in the period 2005–2014. (From Levy et al. 2020 , p. 17)

Closer to the centre of the network, we find a blue cluster, centred around Portes, a widely-cited founding father of migration studies in the USA. Next to him we also see other leading American scholars such as Waldinger, Alba and Zhou, Waters, Rumbaut, and Putnam, whose primary concern is the (economic) integration of immigrants. This cluster of scholars has elsewhere been understood as the “Michigan-Wisconsin” school of migration research, given the two universities’ success in training migration scholars in the US (cf. Hollifield, 2020 ). Traditionally this scholarship has developed in the USA and has been very prominent in the field for decades. Especially Portes is cited extensively, and widely co-cited across the epistemic communities of the whole field.

This cluster is closely interlinked with the neighbouring (at 4 o’clock) cluster of economists, demographers, and other quantitative social scientists (turquoise). At the centre of it is Massey , another giant of migration studies, who mainly conducted his migration research from a demographic perspective. Here we also see economists such as Borjas, Chiswick, and Stark, who predominantly studied the immigration reality of the USA.

Then, at 6 o’clock, we see a light-green cluster. The highly cited scholars in its core are Williams and Krieger, who study migration- and race-related differences in health. For instance, Williams’ highly-cited paper is about the experiences of racism and mental health problems of African Americans, while Krieger investigated how racism and discrimination causes high-blood pressure. Health is one of the ‘younger’ topics in contemporary migration studies; the amount of research on the intersection of migration and health has increased significantly in the last decade (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 ).

Closely interlinked with ‘health’ is the cluster of ‘acculturationists’, positioned at 7 o’clock. The cluster is formed around J.W. Berry, a social-psychologist who introduced a theory of immigrant acculturation ( 1997 ). Scholars in this cluster investigate cross-cultural and intercultural communication from the psychological perspective. Other prominent authors in this cluster include Phinney, Pettigrew, Ward and Tajfel who studied cognitive aspects of prejudice, and Stephan famous for their integrated threat theory of prejudice (Stephan & Stephan, 2000 ).

Another significant group of scholars is positioned between 9 and 12 o’clock of the co-citation network. These are scholars focused on the politics of ethnic and race relations; prominent critical sociologists such as Foucault and Bourdieu are frequently co-cited in this cluster. Among the key authors in this group are Hall, Gilroy, Brubaker, Kymlicka, Asante, Du Bois, and Bonilla-Silva.

At 12 o’clock, we can see an orange cluster, positioned between the ethnic/race relations cluster and the “Global systems school” – this is a relatively new cluster of scholars working on the topic of mobility, developed by Urry, Scheller, and T. Cresswell. Other researchers within this loosely connected cluster focus in their research on mobilities from related to work and studies from the perspective of social and economic geography. The focus on mobility has been on the rise; it entered top three most prominent topics in migration studies in the period 2008–2017 (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 ).

Overall, in the twenty-first century, the scholarship of migration in its variety of approaches and intertwined themes has seemed to move away from “‘ who’- and ‘what’- questions, to ‘how’- and ‘why’-questions”, compared to the early days of this field. Efforts towards quantifying and tracing geographies of migration flows and describing migrant populations in the receiving countries have somewhat declined in academic publications, while research on the subjective experiences of migrants, perceptions of migrants’ identity and belonging, as well as attention to the cultural (super)diversity of societies has become more prominent (ibid. ).

4.2 Internationalisation

Since migration is a global phenomenon, it is important that it is studied in different countries and regions, by scholars with different academic and personal backgrounds, as well as for knowledge to be transferred around the world. Only by bringing together the diversity of perspectives and contexts in which migration is studied we can achieve a truly global and nuanced understanding of migration, its causes, and its consequences.

Over the course of the field’s development, migration studies has internationalised. Even though analysis of internationalisation trends has only been conducted on English-language literature, the trends seem to be rather coherent. The number of the countries producing publications on migration has increased from 47 to 104 in the past 20 years. Publications from non-Anglophone European countries have increased by 15%, to constitute by today almost a third of English-language publications on migration, while the relative share of developed Anglophone countries (USA, UK, Canada, Australia) has declined (Pisarevskaya et al., 2019 ). The proportion of migration research that is internationally co-authored has also increased over the past 20 years, from 5% of articles in 1998 to over 20% in 2018 (Levy et al., 2020 ).

Nevertheless, international collaboration is not equally spread across the world. European and North American migration scholars have produced the highest absolute number of international collaborations between 1998 and 2018, though the relative share of collaborations among Europe-based scholars is much higher (36%) than that of their North American colleagues (15%). The suggested reasons behind these trends could be that critiques of national paradigms in migration studies have been taken up in Europe more eagerly than in North America. This has not happened without facilitation by broader science policies , particularly in the European Union, which funded the creation of the IMISCOE Network of Excellence, a network which intensified international collaborations between the research institutes working on migration and integration issues in various European countries.

In the global south, similar initiatives have been established, such as the Network for Migration Research on Africa and the Asia Pacific Knowledge Network on Migration. In these regions, international co-authorships are not uncommon, but the absolute number of publications in English compared to those from the north is small. We have thus observed an “uneven internationalisation” of migration studies (Levy et al., 2020 ); in the case of the gender and migration nexus, for instance, Kofman ( 2020 ) argues that the concentration of institutions and publishers in migration studies headquartered in the north perpetuates such inequalities.

5 An Outlook on This Interactive Guide to Migration Studies

This book is structured so as to provide an overview of key topics within the pluralist field of migration studies. It is not structured according to specific theories or disciplines, but along topics, such as why and how people migrate, what forms of migration are there, what the consequences of migration are, and how migration can be governed. Per topic, it brings an overview of key concepts and theories as well as illustrations of how these help to understand concrete empirical cases. After each chapter, the reader will have a first overview of the plurality of perspectives developed in migration studies on a specific theme as well as first grasp of empirical case studies.

The book is designed as an ‘interactive guide’; it will help connect readers to readings, projects, and reports for the selected themes via interactive links. To this aim, the book outline largely follows the official taxonomy of migration studies at migrationresearch.com . Throughout the text, there will be interactive links to overview pages on the Migration Research Hub, as well as to specific key readings. This marks the book as a point of entry for readers to get to know the field of migration studies.

Bibliography

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (1997). Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration. International Migration Review, 31 (4), 826–874.

Article Google Scholar

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46 (1), 5–34.

Google Scholar

Bommes, M., & Morawska, E. T. (2005). International migration research: Constructions, omissions, and the promises of Interdisciplinarity . Ashgate.

Boswell, C., & Geddes, A. (2010). Migration and mobility in the European Union . Macmillan International Higher Education.