- Open access

- Published: 21 December 2015

Tools and instruments for needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation of health research capacity development activities at the individual and organizational level: a systematic review

- Johanna Huber 1 ,

- Sushil Nepal 1 ,

- Daniel Bauer 1 ,

- Insa Wessels 2 ,

- Martin R Fischer 1 &

- Claudia Kiessling 1 , 3

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 13 , Article number: 80 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

24 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

In the past decades, various frameworks, methods, indicators, and tools have been developed to assess the needs as well as to monitor and evaluate (needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation; “NaME”) health research capacity development (HRCD) activities. This systematic review gives an overview on NaME activities at the individual and organizational level in the past 10 years with a specific focus on methods, tools and instruments. Insight from this review might support researchers and stakeholders in systemizing future efforts in the HRCD field.

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar. Additionally, the personal bibliographies of the authors were scanned. Two researchers independently reviewed the identified abstracts for inclusion according to previously defined eligibility criteria. The included articles were analysed with a focus on both different HRCD activities as well as NaME efforts.

Initially, the search revealed 700 records in PubMed, two additional records in Google Scholar, and 10 abstracts from the personal bibliographies of the authors. Finally, 42 studies were included and analysed in depth. Findings show that the NaME efforts in the field of HRCD are as complex and manifold as the concept of HRCD itself. NaME is predominately focused on outcome evaluation and mainly refers to the individual and team levels.

A substantial need for a coherent and transparent taxonomy of HRCD activities to maximize the benefits of future studies in the field was identified. A coherent overview of the tools used to monitor and evaluate HRCD activities is provided to inform further research in the field.

Peer Review reports

The capacity to cope with new and ill-structured situations is a crucial ability in today’s world. Developing this ability, by shaping empowered citizens, challenges individuals as well as organisations and societies. This process of empowerment is usually referred to as capacity development (CD) [ 1 ]. While this term has been commonly used for years in the field of foreign aid, other societal and political domains (e.g. social work, education and health systems) are increasingly adopting the concept of CD when developing new or existing competencies, structures, and strategies for building resilient individuals and organizations [ 2 ]. Also in the field of health research, an increasing number of activities to strengthen health research competencies and to support organizations can be observed – as demanded by the three United Nations Millennium Development Goals addressing health related issues [ 3 – 6 ]. Several frameworks are already in use that support a structured approach to health research capacity development (HRCD) and address competencies that are specific to health research [ 7 – 9 ]. These frameworks usually incorporate the individual or team, organization or institution, and society levels [ 8 , 10 , 11 ]. One conclusion that can be drawn from the available evidence is that, in such a structured approach to HRCD efforts, meaningful data collection is crucial. First, data collection incorporates the HRCD needs assessment and second, the monitoring and evaluation (NaME) of activities and programs once implemented. Therefore, HRCD activities should address the needs as assessed. Monitoring and evaluation of these activities should reflect the desired outcomes as defined beforehand [ 12 – 15 ]. Bates et al. [ 16 ] indicate how data collection tools and instruments are usually developed for a certain purpose in a certain context. The context specificity of tools and instruments has to be considered and the appropriateness of these must be determined when selecting instruments for any needs assessment for a new project. This article offers a systematic review of tools and instruments for the NaME of HRCD activities at the individual or team and the organizational levels to aid HRCD initiatives in selecting appropriate tools and instruments for data collection within their respective context. For this purpose, a range of studies published between January 1, 2003, and June 30, 2013, were chosen and analysed based on different context parameters such as the level of the CD and the nature of the HRCD activities.

We followed the PRISMA checklist for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [ 17 ]. Inclusion and analysis criteria were defined in advance and documented in a protocol (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Information sources and search strategy

We conducted the systematic literature search in July 2013. The search was done in both the literature database PubMed and the search engine Google Scholar. We applied the three search terms “capacity building” AND “research ” , “capacity development” AND “research”, and “capacity strengthening” AND “research”. We checked the first 200 hits in Google Scholar for each search term. “Health” and “evaluation” were not included in the search terms as a pre-test search had revealed this would exclude relevant literature. Articles from personal bibliographies of the authors were also included.

Inclusion categories and criteria

The inclusion process was structured along the five inclusion categories ‘capacity development’, ‘research’, ‘health profession fields’, ‘monitoring and evaluation’, and ‘level of NaME’. Table 1 gives a detailed overview of all descriptions and operationalisations used.

The category ‘capacity development’ [ 18 ] represents an exemplary definition which serves as a guideline for inclusion but should not to be applied word by word. ‘Research’ was operationalized according to the categories of the ‘research spider’ [ 19 ]. Some process-related research skills as well as communicational and interpersonal skills were added to our operationalisation [ 20 ]. Main health professions were identified and grouped within different fields. NaME was operationalized according to a self-constructed NaME framework of HRCD activities (Fig. 1 ), which summarizes 13 HRCD/NaME frameworks [ 2 , 5 , 8 , 10 – 13 , 15 , 21 – 25 ] and reflects the level of HRCD, common indicators, and the order (from needs assessment to impact evaluation) commonly used in the original frameworks.

Framework for needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation (NaME) of health research capacity development (HRCD) [ 2 , 5 , 8 , 10 – 13 , 15 , 21 – 25 ].

For the categories ‘research’, ‘health profession fields’ and ‘monitoring and evaluation’, at least one of the operationalisations of each category had to be addressed by the study. The category ‘level of NaME’ was operationalized referring to the ESSENCE framework ‘Planning, monitoring and evaluation framework for capacity strengthening in health research’ which describes three CD levels: individual and/or team, organizational, and system levels [ 10 ]. Only publications focussing on NaME on the individual/team and organizational levels were considered for this review.

Additionally, the following eligibility criteria were set: English or German language, publication period from January 1, 2003, to June 30, 2013, intervention, non-intervention and multiple design studies (Fig. 2 ). We excluded grey literature, editorials, comments, congress abstracts, letters, and similar. Articles focussing on institutional networks with external partners were excluded as well.

Categorization of the study designs. The study designs are restricted to the included studies.

Study selection

Two researchers, JH and SN, independently scanned the abstracts identified for inclusion. In case of disagreement, JH and SN discussed the abstracts in question. If consensus could still not be reached, a third reviewer, CK, was consulted. After consensus on inclusion was reached, the full-texts of all included studies were rechecked for inclusion by JH and SN.

Study analysis procedure

We analysed the included articles according to nine aspects defined in Table 2 .

The search in PubMed revealed 700 suitable records (Fig. 3 ). We removed 27 duplicates, resulting in 673 records for inclusion screening. The first 200 hits for each of the three search terms in Google Scholar were considered, resulting in two additional records after removing duplicates. Furthermore, we included articles from the personal bibliographies of the authors, adding 10 more abstracts after checking for duplicates. Of the 685 records identified, 24 did not contain an abstract, but were preliminarily included for the full-text screening. JH and SN scanned the remaining 661 abstracts in terms of the inclusion criteria, thus excluding 616 records; 45 abstracts and the 24 records without abstracts were considered for full-text screening. After the full-text screening, 42 articles were finally included for further analysis; 37 articles originated from PubMed, one from Google Scholar, and four from the personal bibliographies of the authors.

Flowchart of the inclusion process.

These 42 articles were subsequently analysed along nine aspects (Table 2 ). The results are summarized in Table 3 .

Around half of the NaME studies on HRCD activities were conducted in high-income countries (n = 24) [ 26 ]. Six studies took place in lower-middle-income and two in upper-middle-income economies. Participants of one study were from a low-income country [ 27 ]. Two studies were performed in partnerships between a high-income and several low-, lower-middle and upper-middle-income economies. Mayhew et al. [ 28 ] described a partnership study between two upper-middle income countries and Bates et al. [ 29 ] analysed case studies from two lower-middle-income and two low-income economies. Five authors did not specify the country or region of their studies.

The evaluation focus of the studies was predominately on outcome evaluation (n = 23). Besides that, six studies surveyed the current state, three studies assessed requirements, and two studies investigated needs of HRCD activities. The remaining eight studies combined two evaluation aspects: definition of needs and outcome evaluation (n = 4), analysis of current state and outcome evaluation (n = 1), outcome evaluation and impact evaluation (n = 1), and analysis of current state and definition of needs (n = 1). Jamerson et al. [ 30 ] did not define their focus of evaluation.

Nearly half of the studies investigated HRCD on the individual/team level (n = 20); 16 studies were conducted at both the individual/team and organizational levels. The authors of six studies focused on organizational aspects of HRCD.

Almost all studies (n = 38) described and evaluated HRCD activities; 19 of these HRCD activities were training programmes of predefined duration, lasting between some hours or days up to 2 years. Another nine HRCD activities were perpetual or their duration not specified and 10 studies defined and pre-assessed the setting in preparation of an HRCD activity. The authors of four studies did not specify an HRCD activity, focussing on the development or validation of tools, instruments, and frameworks.

The participants of HRCD activities represent a wide range of health professions (e.g. laboratory scientists, physiotherapists, dentists, pharmacists); 10 studies investigated staff with management tasks in health, e.g. hospital managers, clinical research managers. Nurses participated in eight studies with another eight studies looking into ‘research staff’ and ‘scientists’ with no further description. Medical practitioners were studied in five papers. Besides all these, the background of participants was often not specified beyond general terms like ‘health professionals’, ‘ethic committee members’, ‘scholars’, ‘university faculty members’, or ‘allied health professionals’. In a different approach, Suter et al. [ 31 ] analysed reports and Bates et al. [ 29 ] investigated case studies (without specifying the material scrutinized).

A wide variety of study designs was employed by the studies included in the review. We identified 35 single-study and six multi-study approaches. Of the 35 single-study approaches, 10 were designed as intervention (three with control groups) and 25 as non-intervention studies. Four multi-study approaches combined an intervention study with a non-intervention study. Two multi-study approaches combined different non-intervention studies. Jamerson et al. [ 30 ] did not specify their study design.

Many different tools and instruments for NaME were identified and applied in quantitative, qualitative and mixed mode of analysis. No preferred approach was observed. One third of the studies (n = 16) used a combination of tools for quantitative as well as qualitative analysis. In 13 studies, tools like questionnaires and assessment sheets were applied to evaluate and monitor HRCD activities quantitatively. Evaluation tools, such as interviews, focus group discussions, document analyses, or mapping of cases against evaluation frameworks, were identified in 12 studies and commonly analysed in a qualitative approach. In one study, tools for evaluation were not described at all.

Summary of evidence

The aim of our systematic review was to give an overview on tools and instruments for NaME of HRCD activities on the individual and organizational level; 42 included articles demonstrated a large variety of tools and instruments in specific settings. Questionnaires, assessment sheets and interviews (in qualitative settings) were most commonly applied and in part disseminated for further use, development and validation.

Overall, 36 studies were either conducted on the individual/team or on both individual/team and organizational level. Within these studies, a well-balanced mixture of quantitative, qualitative and mixed tools and modes of analysis were applied. Judging from the depth of these studies, it seems as if NaME of HRCD on the individual level is quite well developed. Only six studies focused exclusively on organizational aspects, almost all with qualitative approaches, indicating that HRCD studies at this level are still mainly exploratory. The organizational level is possibly a more complex construct to measure. The fact that 13 out of 19 studies that broach organizational aspects were conducted in high-income countries might reflect the wider possibilities of these research institutions and indicates a need for more attention to NaME on the organizational level in lower-income settings. Results from these exploratory studies on the organizational level should feed into the development of standardized quantitative indicators more regularly. Qualitative approaches could be pursued for complex and specific constructs not easily covered quantitatively.

By not limiting the primary selection of articles for this review to a specific health profession, it was revealed that staff with management tasks in health research, as well as nurses, were the cohorts most frequently targeted by NaME studies. Further research should concentrate on other health professionals to determine communalities and differences of health-research related skill acquisition and development between health professions. These studies could determine whether and which parts of HRCD and NaME can be considered generic across health professions. Further, we will at some point have to ask, who is being left out and who is not getting access to HRCD programs, and why.

The focus of NaME throughout the studies included in this review was on outcome measurement, regardless of whether these were conducted in high-income, upper-middle, lower-middle, or low-income countries. However, there were only few reports of needs assessment from middle- and low-income economies, while high-income countries regularly give account of current states. While this should not be over-interpreted, it still raises the question of whether the needs assessment in the middle- and low-income countries is being done as thoroughly as warranted, but not reported in the articles, or if these countries’ needs might not always be at the very centre of the HRCD’s attention. While the evaluation of HRCD outcomes is, of course, of importance, more attention should be paid to the sustainability of programs and impact evaluation, e.g. parameters of patient care or societal aspects. Only one study, that of Hyder et al. [ 32 ], made use of one such indicator and assessed the impact of a HRCD training by considering “teaching activities after returning to Pakistan”. The development of valid impact indicators of course constitutes a methodological challenge. Some studies reporting impact evaluation on a system level might of course have been missed due to the search parameters applied.

When undertaking the review, three main methodological weaknesses of this research area became apparent. First, there is a need for common definitions and terminologies to better communicate and compare the HRCD efforts. The analysis of the studies showed that there is an inconsistent use of terms, for example, for CD activities (e.g. training, course, or workshop). Similar problems were already identified in the context of educational capacity building by Steinert et al. [ 33 ], who suggest definitions for different training settings which may also be suitable for a more precise description of CD activities. A common taxonomy for the description of health professionals (i.e. the study participants) would be just as desirable. The use of coherent terms would not only enable the accurate replication of studies but also help in determining whether tools and instruments from one setting can be easily transferred to another. A clear and coherent description of study setting and participants is thus an integral step towards scientific transparency. The incoherent categorisation of study types is probably not a new problem. It is, however, amplified by authors who choose very complex approaches to collect data at different NaME levels with deviating terms to describe these approaches [ 28 , 34 – 36 ].

The second weakness of the research area is the varying adherence to reporting standards. While there are standards available for reporting qualitative or quantitative research (e.g. Rossi et al. [ 12 ], Downing [ 37 ], Mays & Pope [ 38 ]), it seems these or similar recommendations were not frequently considered when reporting or reviewing NaME studies. This was particularly the case in studies with a mixed-method mode of analysis, where the need for more standardised reporting became apparent. Frambach et al.’s [ 39 ] “Quality Criteria in Qualitative and Quantitative Research” could provide guidance, especially for studies with mixed-method approaches. Another important aspect of transparent reporting would be the publication of the tools and instruments used in NaME studies. Of the 42 articles scrutinized during this review, only 15 either disclosed the tools and instruments within the article itself in an appendix or volunteered to have them sent to any audience interested. Of all the tools and instruments disclosed, only two were used in two or more studies. Making the tools and instruments available to the HRCD community would not only allow for their adaptation whenever necessary but, more importantly, support their validation and enhancement.

The last point concerns the study designs implemented. The majority of articles are mainly descriptive, non-intervention studies that only allow for low evidence according to Cochrane standards [ 40 ]. While most HRCD studies conducted in high-income economies were of non-interventional nature, those from low- and middle-income countries were a mix of non-intervention, intervention and multi-study approaches, yielding higher levels of evidence. Of all interventional studies, most employed a quasi-experimental design with only one randomized controlled trial [ 23 ]. The studies reporting HRCD on the institutional level were also primarily on a descriptive level. Cook et al. [ 41 ], however, demand going beyond describing what one did (descriptive studies) or whether an intervention worked or not (justification studies). Instead, they call for analysing how and why a program worked or failed (clarification studies). An in-depth analysis of the effectiveness of different HRCD activities is, however, still lacking.

Limitations of the systematic review

This systematic review displays some methodological limitations itself. The issue of deviating terminologies has been raised earlier. In most cases, we adopted the terms used in the studies themselves, e.g. when reporting the authors’ denoted study designs. In very few cases, we changed or completed terms to make the studies more comparable to others. One example is changing the wording from Green et al.’s [ 35 ] “case study approach” into a “multi-study approach” to match Flyvberg’s taxonomy [ 42 ]. Other limitations typical for reviews may also apply. Relevant sources might not have been detected due to the selected search terms, the range of the data sources, the exclusion of grey literature, and the restriction to English and German sources.

A systematic review on studies from the field of HRCD activities was conducted, with 42 studies being fully analysed. The analysis revealed that a variety of terms and definitions used to describe NaME efforts impedes the comparability and transferability of results. Nevertheless, insight from this review can help to inform researchers and other stakeholders in the HRCD community. A coherent overview on tools and instruments for NaME of HRCD was developed and is provided (Table 3 ).

Furthermore, it is time to set standards for NaME in the HRCD community. Researchers and stakeholders should develop a common research agenda to push, systematise and improve the research efforts in the field of NaME of HRCD activities. To do so, a common language and terminology is required. The conceptualizations used for the purpose of these review can inform this development. On the other hand, we have to critically analyse research gaps in terms of generalizable versus context-specific theories, methods, tools, and instruments. To maximize the benefits and to incorporate different research traditions, these undertakings should be done internationally and multi-professionally within the HRCD community.

Lusthaus C, Adrien M-H, Perstinger M. Capacity Development: Definitions, Issues and Implications for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. Universalia Occasional Paper. 1999;35:[about 21 p.]. http://preval.org/documentos/2034.pdf . Accessed 2 July 2015.

Labin SN, Duffy JL, Meyers DC, Wandersman A, Lesesne CA. A research synthesis of the evaluation capacity building literature. Am J Eval. 2012;33(3):307–38.

Article Google Scholar

Gadsby EW. Research capacity strengthening: donor approaches to improving and assessing its impact in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26(1):89–106. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1031 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bailey J, Veitch C, Crossland L, Preston R. Developing research capacity building for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander health workers in health service settings. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(4):556.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Lansang MA, Dennis R. Building capacity in health research in the developing world. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(10):764–70.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

United Nations. Millennium Development Goals and Beyond. 2015. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ . Accessed 2 July 2015.

Google Scholar

Banzi R, Moja L, Pistotti V, Facchini A, Liberati A. Conceptual frameworks and empirical approaches used to assess the impact of health research: an overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-26 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cooke J. A framework to evaluate research capacity building in health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-44 .

Trostle J. Research capacity building in international health: definitions, evaluations and strategies for success. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35(11):1321–4.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

ESSENCE (Enhancing Support for Strengthening the Effectiveness of National Capacity Efforts). Planning, monitoring and evaluation framework for capacity strengthening in health research. Geneva: ESSENCE Good practice document series; 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/TDR_essence_11.1_eng.pdf?ua = 1. Accessed 2 July 2015.

Ghaffar A, IJsselmuiden C, Zicker F. Changing mindsets: Research capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED), Global Forum for Health Research, INICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR); 2008. http://www.cohred.org/downloads/cohred_publications/Changing_Mindsets.pdf . Accessed 30 November 2015.

Rossi PH, Lipsey MW, Freeman HE. Evaluation. A systematic approach. 7th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2004.

Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? 1988. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121(11):1145–50.

McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB. Logic models: a tool for telling your programs performance story. Eval Program Plan. 1999;22(1):65–72.

Best A, Terpstra JL, Moor G, Riley B, Norman CD, Glasgow RE. Building knowledge integration systems for evidence-informed decisions. J Health Organ Manage. 2009;23(6):627–41.

Bates I, Boyd A, Smith H, Cole DC. A practical and systematic approach to organisational capacity strengthening for research in the health sector in Africa. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-11 .

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 . Epub 2009 Jul 21.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. Capacity WORKS: The Management Model for Sustainable Development. Eschborn: GTZ; 2009.

Smith H, Wright D, Morgan S, Dunleavey J. The ‘Research Spider’: a simple method of assessing research experience. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2002;3:139–40.

Bauer D, Wessels I, Huber J, Fischer MR, Kiessling C. Current State and Needs Assessment for Individual and Organisational Research Capacity Strengthening in Africa: A Case Report from Mbeya (TZ), and Kumasi (GH). Eschborn: Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH; 2013.

Bates I, Akoto AY, Ansong D, Karikari P, Bedu-Addo G, Critchley J, et al. Evaluating health research capacity building: An evidence-based tool. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8), e299.

Golenko X, Pager S, Holden L. A thematic analysis of the role of the organisation in building allied health research capacity: a senior managers’ perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:276. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-276 .

Ijsselmuiden C, Marais DL, Becerra-Posada F, Ghannem H. Africa’s neglected area of human resources for health research - the way forward. S Afr Med J. 2012;102(4):228–33.

Levine R, Russ-Eft D, Burling A, Stephens J, Downey J. Evaluating health services research capacity building programs: Implications for health services and human resource development. Eval Program Plan. 2013;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.12.002 . Epub 2012 Dec 12.

Mahmood S, Hort K, Ahmed S, Salam M, Cravioto A. Strategies for capacity building for health research in Bangladesh: Role of core funding and a common monitoring and evaluation framework. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-31 .

The World Bank. Data: Country and Lending Groups. 2015. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups . Accessed 2 July 2015.

Njie-Carr V, Kalengé S, Kelley J, Wilson A, Muliira JK, Nabirye RC, et al. Research capacity-building program for clinicians and staff at a community-based HIV clinic in Uganda: a pre/post evaluation. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(5):431–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.11.002 .

Mayhew SH, Doherty J, Pitayarangsarit S. Developing health systems research capacities through north–south partnership: an evaluation of collaboration with South Africa and Thailand. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-8 .

Bates I, Taegtmeyer M, Squire BS, Ansong D, Nhlema-Simwaka B, Baba A, et al. Indicators of sustainable capacity building for health research: analysis of four African case studies. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-14 .

Jamerson PA, Fish AF, Frandsen G. Nursing Student Research Assistant Program: A strategy to enhance nursing research capacity building in a Magnet status pediatric hospital. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(2):110–3. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.08.004 .

Suter E, Lait J, Macdonald L, Wener P, Law R, Khalili H, et al. Strategic approach to building research capacity in inter-professional education and collaboration. Healthc Q. 2011;14(2):54–60.

Hyder AA, Akhter T, Qayyum A. Capacity development for health research in Pakistan: the effects of doctoral training. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18(3):338–43.

Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, Dolmans D, Spencer J, Gelula M, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526.

Ajuwon AJ, Kass N. Outcome of a research ethics training workshop among clinicians and scientists in a Nigerian university. BMC Medical Ethics. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-9-1 .

Green B, Segrott J, Hewitt J. Developing nursing and midwifery research capacity in a university department: case study. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):302–13.

Janssen J, Hale L, Mirfin-Veitch B, Harland T. Building the research capacity of clinical physical therapists using a participatory action research approach. Phys Ther. 2013;93(7):923–34. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120030 .

Downing SM. Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37(9):830–7.

Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):50–2.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Frambach JM, van der Vleuten CP, Durning SJ. AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):552. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f .

Cochrane Consumer Network. Levels of Evidence. 2015. http://consumers.cochrane.org/levels-evidence#about-cochrane . Accessed 30 November 2015.

Cook DA, Bordage G, Schmidt HG. Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(2):128–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02974.x . Epub 2008 Jan 8.

Bent Flyvbjerg. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual Inq. 2006;12:219. doi: 10.1177/1077800405284363 .

Ali J, Hyder AA, Kass NE. Research ethics capacity development in Africa: exploring a model for individual success. Dev World Bioeth. 2012;12(2):55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00331.x .

Barchi FH, Kasimatis-Singleton M, Kasule M, Khulumani P, Merz JF. Building research capacity in Botswana: a randomized trial comparing training methodologies in the Botswana ethics training initiative. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-14 .

Bates I, Ansong D, Bedu-Addo G, Agbenyega T, Akoto AY, Nsiah-Asare A, et al. Evaluation of a learner-designed course for teaching health research skills in Ghana. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:18.

Bullock A, Morris ZS, Atwell C. Collaboration between health services managers and researchers: making a difference? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17 Suppl 2:2–10. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011099 .

Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs. Mumbai: Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 1998.

Kirkpatrick DL. Techniques for evaluating training programs. Training Dev J. 1979;33:78–92.

Cooke J, Nancarrow S, Dyas J, Williams M. An evaluation of the ‘Designated Research Team’ approach to building research capacity in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-37 .

Corchon S, Portillo MC, Watson R, Saracíbar M. Nursing research capacity building in a Spanish hospital: an intervention study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17–18):2479–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03744.x .

Dodani S, La Porte RE. Ways to strengthen research capacity in developing countries: effectiveness of a research training workshop in Pakistan. Public Health. 2008;122(6):578–87. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.09.003 .

du Plessis E, Human SP. Reflecting on ‘meaningful research’: a qualitative secondary analysis. Curationis. 2009;32(3):72–9.

Finch E, Cornwell P, Ward EC, McPhail SM. Factors influencing research engagement: research interest, confidence and experience in an Australian speech-language pathology workforce. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:144. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-144 .

Holden L, Pager S, Golenko X, Ware RS, Weare R. Evaluating a team-based approach to research capacity building using a matched-pairs study design. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-16 .

Henderson-Smart DJ, Lumbiganon P, Festin MR, Ho JJ, Mohammad H, McDonald SJ, et al. Optimising reproductive and child health outcomes by building evidence-based research and practice in South East Asia (SEA-ORCHID): study protocol. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:43.

Holden L, Pager S, Golenko X, Ware RS. Validation of the research capacity and culture (RCC) tool: measuring RCC at individual, team and organisation levels. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18(1):62–7. doi: 10.1071/PY10081 .

Hyder AA, Harrison RA, Kass N, Maman S. A case study of research ethics capacity development in Africa. Acad Med. 2007;82(7):675–83.

Jones A, Burgess TA, Farmer EA, Fuller J, Stocks NP, Taylor JE, et al. Building research capacity. An exploratory model of GPs’ training needs and barriers to research involvement. Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32(11):957–60.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kwon S, Rideout C, Tseng W, Islam N, Cook WK, Ro M, et al. Developing the community empowered research training program: building research capacity for community-initiated and community-driven research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(1):43–52. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0010 .

Lazzarini PA, Geraghty J, Kinnear EM, Butterworth M, Ward D. Research capacity and culture in podiatry: early observations within Queensland Health. J Foot Ankle Res. 2013;6(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-6-1 .

McIntyre E, Brun L, Cameron H. Researcher development program of the primary health care research, evaluation and development strategy. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(1):114–21. doi: 10.1071/PY10049 .

Minja H, Nsanzabana C, Maure C, Hoffmann A, Rumisha S, Ogundahunsi O, et al. Impact of health research capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries: the case of WHO/TDR programmes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(10):e1351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001351 .

Moore J, Crozier K, Kite K. An action research approach for developing research and innovation in nursing and midwifery practice: building research capacity in one NHS foundation trust. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.01.014 .

Otiniano AD, Carroll-Scott A, Toy P, Wallace SP. Supporting Latino communities’ natural helpers: a case study of promotoras in a research capacity building course. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):657–63. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9519-9 .

Pager S, Holden L, Golenko X. Motivators, enablers, and barriers to building allied health research capacity. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:53–9. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S27638 .

Perry L, Grange A, Heyman B, Noble P. Stakeholders’ perceptions of a research capacity development project for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(3):315–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00801.x .

Priest H, Segrott J, Green B, Rout A. Harnessing collaboration to build nursing research capacity: a research team journey. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27(6):577–87.

Green B, Segrott J, Coleman M, Cooke A. Building the research capacity of an academic department of nursing. Occasional Paper 1a. Swansea: School of Health Sciences, University of Wales; 2005.

Segrott J, Green B, McIvor M. Challenges and strategies in developing nursing research capacity: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(5):637–51.

Redman-MacLaren M, MacLaren DJ, Harrington H, Asugeni R, Timothy-Harrington R, Kekeubata E, et al. Mutual research capacity strengthening: a qualitative study of two-way partnerships in public health research. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-79 .

Ried K, Farmer EA, Weston KM. Setting directions for capacity building in primary health care: a survey of a research network. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:8.

Salway S, Piercy H, Chowbey P, Brewins L, Dhoot P. Improving capacity in ethnicity and health research: report of a tailored programme for NHS Public Health practitioners. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013;14(4):330–40. doi: 10.1017/S1463423612000357 .

Webster E, Thomas M, Ong N, Cutler L. Rural research capacity building program: capacity building outcomes. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17(1):107–13. doi: 10.1071/PY10060 .

Wilson LL, Rice M, Jones CT, Joiner C, LaBorde J, McCall K, et al. Enhancing research capacity for global health: evaluation of a distance-based program for international study coordinators. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2013;33(1):67–75. doi: 10.1002/chp.21167 .

Wootton R. A simple, generalizable method for measuring individual research productivity and its use in the long-term analysis of departmental performance, including between-country comparisons. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-2 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institut für Didaktik und Ausbildungsforschung in der Medizin, Klinikum der Universität München, Ziemssenstraße 1, 80336, Munich, Germany

Johanna Huber, Sushil Nepal, Daniel Bauer, Martin R Fischer & Claudia Kiessling

bologna.lab, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Hausvogteiplatz 5-7, 10117, Berlin, Germany

Insa Wessels

Medizinische Hochschule Brandenburg Theodor Fontane, Fehrbelliner Straße 38, 16816, Neuruppin, Germany

Claudia Kiessling

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Johanna Huber .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JH and SN designed and conducted the systematic review. JH wrote the draft of the systematic review and revised it according to the commentaries of SN, DB, IW, MF, and CK. JH provided the final version of the manuscript. SN additionally critically reviewed the manuscript and substantially contributed to the final version of the manuscript. DB critically reviewed both the design of the systematic review as well as the manuscript. He was involved in the development of meaningful inclusion criteria. DB contributed substantially to the final version of the manuscript. IW critically reviewed the design of the study and made important suggestions for improvement. She also critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed substantially to the final version of the manuscript. MF critically reviewed the design of the study and the manuscript. He suggested important improvements for the design of the study and substantially contributed to the final version of the manuscript. CK made substantial contributions to the design, conduction and review of the study, and was the third reviewer during the inclusion process of the identified studies. She critically reviewed the manuscript and delivered important improvements for the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Huber, J., Nepal, S., Bauer, D. et al. Tools and instruments for needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation of health research capacity development activities at the individual and organizational level: a systematic review. Health Res Policy Sys 13 , 80 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0070-3

Download citation

Received : 23 July 2015

Accepted : 07 December 2015

Published : 21 December 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0070-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health research capacity development

- Individual level

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Needs assessment

- Organizational level

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A guiding framework for needs assessment evaluations to embed digital platforms in partnership with Indigenous communities

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft

Affiliation School of Occupational and Public Health, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Île-à-la-Crosse School Division, The Northern Village of Île-à-la-Crosse, Île-à-la-Crosse, SK, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Supervision

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations DEPtH Lab, Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University, London, ON, Canada, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada, Lawson Health Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada

- Jasmin Bhawra,

- M. Claire Buchan,

- Brenda Green,

- Kelly Skinner,

- Tarun Reddy Katapally

- Published: December 22, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282

- Reader Comments

Introduction

In community-based research projects, needs assessments are one of the first steps to identify community priorities. Access-related issues often pose significant barriers to participation in research and evaluation for rural and remote communities, particularly Indigenous communities, which also have a complex relationship with academia due to a history of exploitation. To bridge this gap, work with Indigenous communities requires consistent and meaningful engagement. The prominence of digital devices (i.e., smartphones) offers an unparalleled opportunity for ethical and equitable engagement between researchers and communities across jurisdictions, particularly in remote communities.

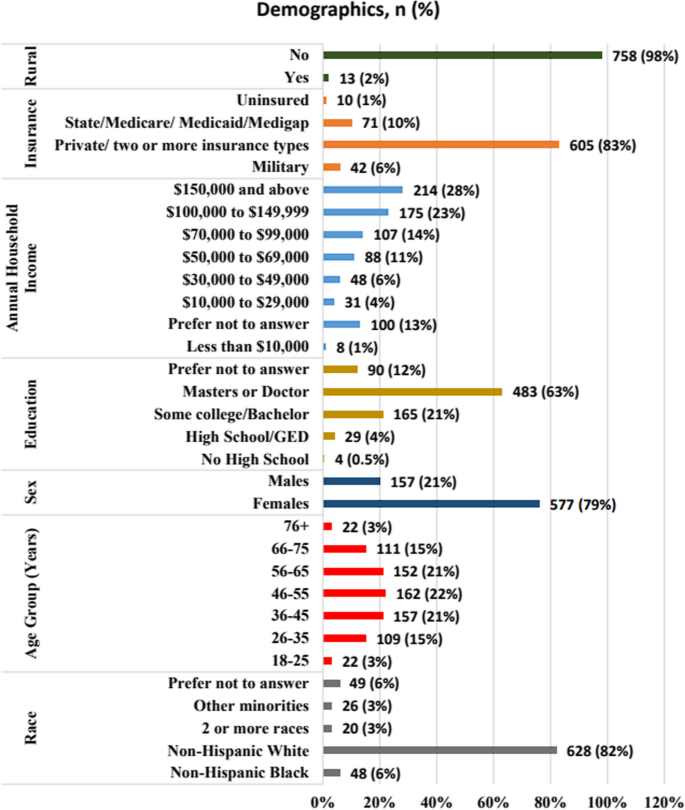

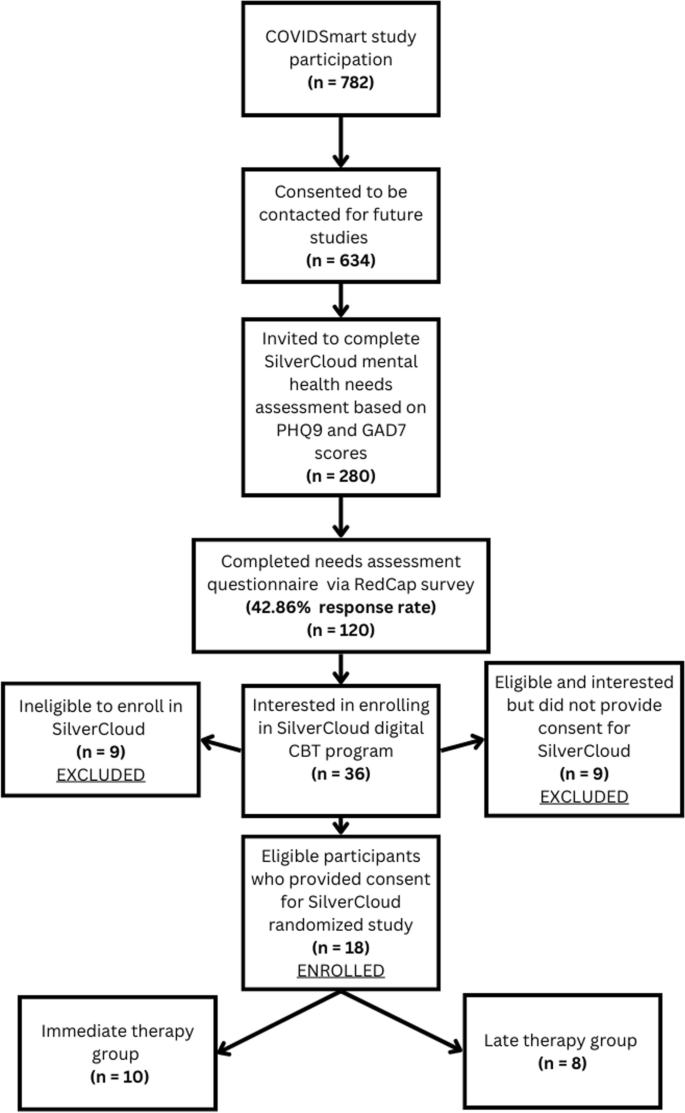

This paper presents a framework to guide needs assessments which embed digital platforms in partnership with Indigenous communities. Guided by this framework, a qualitative needs assessment was conducted with a subarctic Métis community in Saskatchewan, Canada. This project is governed by an Advisory Council comprised of Knowledge Keepers, Elders, and youth in the community. An environmental scan of relevant programs, three key informant interviews, and two focus groups (n = 4 in each) were conducted to systematically identify community priorities.

Through discussions with the community, four priorities were identified: (1) the Coronavirus pandemic, (2) climate change impacts on the environment, (3) mental health and wellbeing, and (4) food security and sovereignty. Given the timing of the needs assessment, the community identified the Coronavirus pandemic as a key priority requiring digital initiatives.

Recommendations for community-based needs assessments to conceptualize and implement digital infrastructure are put forward, with an emphasis on self-governance and data sovereignty.

Citation: Bhawra J, Buchan MC, Green B, Skinner K, Katapally TR (2022) A guiding framework for needs assessment evaluations to embed digital platforms in partnership with Indigenous communities. PLoS ONE 17(12): e0279282. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282

Editor: Stephane Shepherd, Swinburne University of Technology, AUSTRALIA

Received: June 1, 2022; Accepted: December 2, 2022; Published: December 22, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Bhawra et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data are co-owned by the community and all data requests should be approved by the Citizen Scientist Advisory Council and the University of Regina Research Office. Citizen Scientist Advisory Council Contact: Mr. Duane Favel, Mayor of Ile-a-lacrosse, email: [email protected] ; [email protected] University of Regina Research Office contact: Ara Steininger, Research Compliance Officer; E-mail: [email protected] . Those interested can access the data in the same manner as the authors.

Funding: TRK received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canada Research Chairs Program to conduct this research. The funding organization had no role to play in any part of the study implementation of manuscript generation.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Community engagement has been the cornerstone of participatory action research in a range of disciplines. Every community has a unique culture and identity, hence community members are the experts regarding their diverse histories, priorities, and growth [ 1 – 3 ]. As a result, the successful uptake, implementation, and longevity of community-based research initiatives largely depends on meaningful community engagement [ 4 – 9 ]. There is a considerable body of evidence establishing the need for ethical community-research partnerships which empower citizens and ensure relevant and sustainable solutions [ 1 – 3 , 10 ]. For groups that have been marginalized or disadvantaged, community-engaged research that prioritizes citizens’ control in the research process can provide a platform to amplify citizens’ voices and ensure necessary representation in decision-making [ 11 ]. Such initiatives must be developed in alignment with a community’s cultural framework, expectations, and vision [ 12 ] to support continuous and meaningful engagement throughout the project. In particular, when partnering with Indigenous communities, a Two-Eyed Seeing approach can provide valuable perspective to combine the strengths of Indigenous and Western Knowledges, including culturally relevant methods, technologies, and tools [ 13 – 15 ].

Many communities have a complicated relationship with research as a result of colonialism, and the trauma of exploitation and discrimination has continued to limit the participation of some communities in academic partnerships [ 16 ]. Indigenous Peoples in Canada experience a disproportionate number of health, economic, and social inequalities compared to non-Indigenous Canadians [ 17 ]. Many of these health (e.g., elevated risk of chronic and communicable diseases) [ 18 – 21 ]), socioeconomic (e.g., elevated levels of unemployment and poverty) [ 19 , 22 – 24 ], and social (e.g., racism and discrimination) [ 19 , 22 – 24 ]) inequities can be traced back to the long-term impacts of assimilation, colonization, residential schools, and a lack of access to healthcare [ 19 , 20 , 22 – 24 ]. To bridge this gap, and more importantly, to work towards Truth and Reconciliation [ 25 ], work with Indigenous Peoples must be community-driven, and community-academia relationship building is essential before exploring co-conceptualization of initiatives [ 26 ].

One of the first steps in building a relationship is to learn more about community priorities by conducting a needs assessment [ 27 , 28 ]. A needs assessment is a research and evaluation method for identifying areas for improvement or gaps in current policies, programs, and services [ 29 ]. When conducted in partnership with a specific community, needs assessments can identify priorities and be used to develop innovative solutions, while leveraging the existing knowledge and systems that communities have in place [ 30 ]. Needs assessments pave the path for understanding the value and applicability of research for community members, incorporating key perspectives, and building authentic partnerships with communities to support effective translation of research into practice.

For rural, remote, and northern communities within Canada, issues related to access (e.g., geographic location, transportation, methods of communication, etc.) pose significant barriers to participation in research and related initiatives [ 31 ]. Digital devices, and in particular, the extensive usage of smartphones [ 32 ] offers a new opportunity to ethically and equitably engage citizens [ 33 ]. Digital platforms (also referred to as digital tools) are applications and software programs accessible through digital devices. Digital platforms can be used for a variety of purposes, ranging from project management, to healthcare delivery or mass communication [ 34 ]. Digital infrastructure–the larger systems which support access and use of these digital platforms, including internet, satellites, cellular networks, and data storage centres [ 34 ]. The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has catalyzed the expansion of digital technology, infrastructure and the use of digital devices in delivering essential services (e.g., healthcare) and programs to communities [ 35 , 36 ].

While digital platforms have been used in Indigenous communities for numerous initiatives, including environmental mapping initiatives (e.g., research and monitoring, land use planning, and wildlife and harvest studies) [ 37 , 38 ] and telehealth [ 39 ], there has largely been isolated app development without a corresponding investment in digital infrastructure. This approach limits the sustainability of digital initiatives, and importantly does not acknowledge an Indigenous world view of holistic solutions [ 39 ].

Thus given the increasing prominence of digital devices [ 39 , 40 ], it is critical to evaluate the conceptualization, implementation, and knowledge dissemination of digital platforms. To date, there is little guidance on how to evaluate digital platforms, particularly in partnership with rural and remote communities [ 41 ]. A review of recent literature on community-based needs assessments uncovered numerous resources for conducting evaluations of digital platforms, however, a key gap is the lack of practical guidance for conducting needs assessments in close collaboration with communities in ways that acknowledge existing needs, resources, supports and infrastructure that also incorporates the potential role of digital platforms in addressing community priorities.

This paper aims to provide researchers and evaluators with a framework (step-by-step guide) to conduct needs assessments for digital platforms in collaboration with Indigenous communities. To achieve this goal, a novel needs assessment framework was developed using a Two-Eyed Seeing approach [ 13 – 15 ] to enable the identification of community priorities, barriers and supports, as well as existing digital infrastructure to successfully implement digital solutions. To demonstrate the application of this framework, a community-engaged needs assessment conducted with a subarctic Indigenous community in Canada is described and discussed in detail.

Framework design and development

This project commenced with the design and development of a new framework to guide community-based needs assessments in the digital age.

Needs assessments

Needs assessments are a type of formative evaluation and are often considered a form of strategic or program planning, even more than they are considered a type of evaluation. Needs assessments can occur both before and during an evaluation or program implementation; however, needs assessments are most effective when they are conducted before a new initiative begins or before a decision is made about what to do (e.g., how to make program changes) [ 29 ]. Typically, a needs assessment includes: 1) collecting information about a community; 2) determining what needs are already being met; and 3) determining what needs are not being met and what resources are available to meet those needs [ 42 ].

Framework development

Based on existing literature, community consultation, and drawing expertise from our team of evaluation experts who have over a decade of experience working with Indigenous communities on a range of research and evaluation projects, a novel framework was developed to guide community-based needs assessments focused on the application of digital platforms.

This framework (see Fig 1 ) is driven by core questions necessary to identify community priorities that can be addressed by developing and implementing digital platforms. Through team discussion and community consultation, five key topic areas for the assessment of community needs were identified: i) current supports; ii) desired supports; iii) barriers; iv) community engagement; and v) digital access and connectivity. A series of general questions across the five needs assessment topic areas were developed. Thereafter, a set of sub-questions were embedded in each key topic area.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282.g001

The Guiding Framework outlines an approach for conducting community needs assessments which can be adapted across communities and jurisdictions. This framework offers a flexible template that can be used iteratively and applied to various community-engaged needs assessments in a range of areas, including but not limited to community health and wellness projects. The questions assigned to each topic area can be used to guide needs assessments of any priority identified by community stakeholders as suitable for addressing with digital platforms.

Needs assessment methods

The Guiding Framework was implemented in collaboration with a subarctic Indigenous community in Canada, and was used to identify key community priorities, barriers, supports, and existing digital infrastructure which could inform the design and implementation of tailored digital platforms.

Using an environmental scan of relevant documents and qualitative focus groups and interviews, a needs assessment was conducted with the Northern Village of Île-à-la-Crosse, Saskatchewan, Canada between February and May 2020.

This project is governed by a Citizen Scientist Advisory Council which included researchers, Knowledge Keepers, Elders, and youth from Île-à-la-Crosse. The study PI (TRK) and Co-Investigator (JB) developed a relationship with key decision-makers in Île-à-la-Crosse in 2020. Through their guidance and several community visits, the decision-makers introduced the research team to Elders, youth, and other community members to gain a better understanding of current priorities and needs in Île-à-la-Crosse. The research team developed relationships with these community members and invited them to join the Council to formally capture feedback and plan ongoing projects to promote health and wellbeing in the community. The Council represents the needs and interests of the community, and guides the project development, implementation, and evaluation. Council members were provided with Can $150 (US $119.30) as honoraria for each meeting to respect their time, knowledge, and contributions.

Written consent was obtained from all focus group participants and verbal consent was obtained from all key informants participating in interviews. This study received ethics clearance from the research ethics boards of the University of Regina and the University of Saskatchewan through a synchronized review protocol (REB# 2017–29).

Established in 1776, Île-à-la-Crosse is a northern subarctic community with road access in northwest Saskatchewan. Sakitawak, the Cree name for Île-à-la-Crosse, means “where the rivers meet,” hence the community was an historically important meeting point for the fur trade in the 1800s [ 43 , 44 ] The community lies on a peninsula on the Churchill River, near the intersections with the Beaver River and Canoe River systems. Île-à-la-Crosse has a rich history dating back to the fur trade. Due to its strategic location, Montreal-based fur traders established the first trading point in Île-à-la-Crosse in 1776, making the community Saskatchewan’s oldest continually inhabited community next to Cumberland House [ 45 ]. In 1821, Île-à-la-Crosse became the headquarters for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s operations in the territory. In 1860, the first convent was established bringing Western culture, medical services, and education to the community.

Île-à-la-Crosse has a population of roughly 1,300 people [ 19 ]. Consistent with Indigenous populations across Canada, the average age of the community is 32.7 years, roughly 10 years younger than the Canadian non-Indigenous average [ 19 ]. Census data report that just under half (44%) of the community’s population is under the age of 25, 46.3% are aged 25–64, and 9.3% aged 65 and over [ 19 ]. Members of the community predominantly identify as Métis (77%), with some identifying as First Nations (18%), multiple Indigenous responses (1.2%), and non-Indigenous (2.7%) [ 19 ]. Many community members are employed in a traditional manner utilizing resources of the land (e.g., hunting, fishing, trapping), others in a less traditional manner (e.g., lumbering, tourism, wild rice harvesting), and some are employed through the hospital and schools. The community currently has one elementary school with approximately 200 students from preschool to Grade 6, and one high school serving Grades 7–12 with adult educational programming. Île-à-la-Crosse has a regional hospital with Emergency Services, which includes a health services centre with a total of 29 beds. Other infrastructure of the community includes a Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) station, a village office, volunteer fire brigade, and a catholic church [ 46 ].

Needs assessment approach

Île-à-la-Crosse shared their vision of integrating digital technology and infrastructure as part of its growth, thus the needs assessment was identified as an appropriate method to provide the formative information necessary to understand what the needs are, including who (i.e., players, partners), and what (i.e., information sources) would need to be involved, what opportunities exist to address the needs, and setting priorities for action with key community stakeholders [ 47 ]. As a starting point and rationale for this needs assessment, the community of Île-à-la-Crosse values the potential of technology for improving health communication, information reach, access to resources, and care, and was interested in identifying priorities to begin building digital infrastructure. Given the timing of the COVID-19 pandemic, being responsive to community health needs were key priorities that they wanted to start addressing using a digital platform. This needs assessment facilitated and enabled new conversations around key priorities and next steps.

The evaluation approach was culturally-responsive and included empowerment principles [ 48 – 50 ]. Empowerment evaluation intends to foster self-determination. The empowerment approach [ 50 ] involved community members–represented through the Citizen Scientist Advisory Council–engaging in co-production of the evaluation design and implementation by establishing key objectives for the evaluation, informing evaluation questions, building relevant and culturally responsive indicators, developing focus group guides, leading recruitment and data collection, and interpreting results [ 51 ]. In this way, the approach incorporated local community and Indigenous Knowledges as well as Western knowledge, in a similar approach to Two-Eyed Seeing [ 13 – 15 ]. Using these needs assessment evaluation results, the community will identify emerging needs and potential application issues, and work with the researchers to continue shaping project development and implementation.

Two-Eyed Seeing to embed digital platforms

Two-Eyed Seeing as described by Elder Albert Marshall [ 13 , 14 ], refers to learning to see with the strengths of Indigenous and Western Knowledges. Our engagement and overall approach to working with the community of Île-à-la-Crosse takes a Two-Eyed Seeing lens, from co-conceptualization of solutions, which starts with understanding the needs of the community. All needs are a result of direct Indigenous Knowledge that was provided by the Advisory Council. Indigenous Knowledge is not limited to the knowledge of Elders and Traditional Knowledge Keepers; however, they play a critical role in guiding that knowledge through by providing historical, geographic, and cultural context. Moreover, the Knowledge Keepers can be key decision-makers in the community, and in our case, they were key informants who participated in this needs assessment. Every aspect of needs assessment was dependent on the Advisory Council and Key informants providing the Indigenous Knowledge that the research team needed to tailor digital solutions. As a result, Two-Eyed Seeing approach informed all aspects of the research process.

As we are working to develop, and bring digital platforms and technologies (i.e., Western methods) to address key community priorities, Indigenous Knowledge is central to the overall project. Indigenous Elders, decision-makers, and Advisory Council members are bringing both their historical and lived experience to inform project goals, key priority areas, target groups, and methods. Île-à-la-Crosse is a predominantly Metis community, which differs in culture from other Indigenous communities in Canada—First Nations and Inuit communities. Ceremony is not a key part of community functioning; thus, specific cultural ceremonies were not conducted upon advice of the Advisory Council. Instead, the knowledge of historical issues, challenges, and success stories in the community is considered Indigenous Knowledge for this needs assessment, and more importantly, this Indigenous Knowledge informed the focus areas and next steps for this project. Overall, the spirit of collaboration and co-creation which combined Western research methods/technology with Indigenous Knowledge and expertise is considered Two-Eyed Seeing in this project. This lens was taken at all phases, from the engagement stage to Advisory Council meetings, to planning and executing the needs assessment and next steps.

Data collection

In order to obtain an in-depth understanding of the key priorities and supports within the community of Île-à-la-Crosse, this needs assessment used a qualitative approach. An environmental scan was conducted in February 2020 of current school and community policies and programs. Published reports, meeting memos, community social media accounts, and the Île-à-la-Crosse website were reviewed for existing policies and programs. The Citizen Scientist Advisory Council identified appropriate data sources for the document review and corroborated which programs and initiatives were currently active in the community.

Qualitative data were collected from key decision-makers and other members within the community. A purposeful convenience sampling approach was employed to identify members of the community who could serve on the Council and participate in focus group discussions. Key decision makers and existing Council members recommended other community members who could join the focus group discussions to provide detailed and relevant information on community priorities, digital infrastructure, supports, and challenges. Two focus groups were conducted by members of the research team in Île-à-la-Crosse with the Council in May 2020. Focus group participants were asked to describe community priorities, supports, and barriers, as well as experience and comfort with digital platforms. Each focus group had four participants, were two-hours in length, and followed an unstructured approach. Three key informant interviews were conducted in Île-à-la-Crosse between February and April 2020. One-hour interviews were conducted one-on-one and followed a semi-structured interview format. The focus groups and key informant interviews were led by the study PI, TRK, and Co-Investigator, JB, who have extensive training and experience with qualitative research methods, particularly in partnership with Indigenous communities. Focus groups and key informant interviews were conducted virtually using Zoom [ 52 ]. The key informant interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. All data were aggregated, anonymized, and securely stored in a cloud server. Data are owned by the community. Both the Council and the research team have equal access to the data.

Data analysis

All documents identified through the environmental scan were reviewed for key themes. A list of existing school and community programs was compiled and organized by theme (i.e., education-focused, nutrition-focused, health-focused, etc.). Follow-up conversations with key informants verified the continued planning and provision of these programs.

Following the 6-step method by Braun and Clarke (2006), a thematic analysis was conducted to systematically identify key topic areas and patterns across discussions [ 53 ]. A shortlist of themes was created for the key informant interviews and focus groups, respectively. A manual open coding process was conducted by two reviewers who reached consensus on the final coding manual and themes. Separate analyses were conducted for key informant interviews and focus group discussions; however, findings were synthesized to identify key themes and sub-themes in key priorities for the community, community supports and barriers, as well as digital connectivity and infrastructure needs.

Needs assessment findings

The needs assessment guiding framework informed specific discussions of key issues in the community of Île-à-la-Crosse. Key informant interviews and focus group discussions commenced by asking about priorities–“what are the key areas of focus for the community?” In all conversations–including a document review of initiatives in Île-à-la-Crosse–health was highlighted as a current priority; hence, questions in the guiding framework were tailored to fit a needs assessment focused on community health. The following five overarching evaluation questions were used to guide the evaluation: i) What are the prominent health issues facing residents of Île-à-la-Crosse?; ii) What supports are currently available to help residents address prominent health issues in the community?; iii) What types of barriers do community members face to accessing services to manage their health?; iv) How is health-related information currently shared in the community?; and v) To what extent are health services and information currently managed digitally/electronically? The evaluation questions were kept broad to capture a range of perspectives. An evaluation matrix linking the proposed evaluation questions to their respective sub-questions, indicators, and data collection tools is outlined in Table 1 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282.t001

Feedback on each needs assessment topic area is summarized in the sections below. Sample quotes supporting each of the key topic areas is provided in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282.t002

Key priorities

Four priorities were identified through the focus groups, key informant interviews, and document review ( Fig 2 ). Given the timing of the discussion, the primary issue of concern was the COVID-19 pandemic. Many community members were worried about contracting the virus, and the risk it posed to Elders in the community. Of greater concern, however, was how COVID-19 exacerbated many existing health concerns including diabetes and hypertension in the community. For example, routine procedures were postponed and community members with other health conditions were not receiving routine healthcare during the height of the pandemic. The St. Joseph’s Hospital and Health Centre services Île-à-la-Crosse and bordering communities, hence maintaining capacity for COVID-19 patients was a priority. COVID-19 exposed existing barriers in the healthcare system which are described in greater detail in the barriers to community health section.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279282.g002

Another priority discussed by many community members was climate change and the environment. Community members noted that changes in wildlife patterns, land use, and early winter ice road thaw were areas of concern, particularly due to the impact these factors have on traditional food acquisition practices (i.e., hunting) and food access. For instance, the geographic location of Île-à-la-Crosse is surrounded by a lake, and the main highway which connects the community to the land has experienced increased flooding in the past few years.

In addition to posing immediate danger to community members, food security and sovereignty are also closely linked to road access. While the community produces some of its own food through the local fishery and greenhouses, Île-à-la-Crosse is still dependent on a food supply from the south (i.e., Saskatoon). During COVID-19, food access was further restricted due to limited transport and delivery of food products, which increased the risk of food insecurity for community members. Food insecurity was believed to be of bigger concern for Elders in the community compared to younger members. Younger community members expressed having the ability to source their own food in a variety of capacities (e.g., fishing in the lake), whereas Elders rely more heavily on community resources and support (e.g., grocery stores, friends, and family).

Community members also discussed issues surrounding mental health and wellbeing. This topic was of particular concern for youth and Elders in the community. Community members discussed the importance of identifying covert racism (vs. discrimination) that exists within health services that exacerbated mental health issues and care, as well as developing coping strategies, resilience, and supports to prevent mental health crises. Key informants emphasized the need to minimize the stigma around mental health and focus on holistic wellbeing as they work to develop strategies to improve community wellness.

Community health supports

Île-à-la-Crosse has been working on developing supports to improve community health through various initiatives. A document review identified a community-specific wellness model which has informed program development and planning over the past few years. The key components of the Île-à-la-Crosse wellness model are: i) healthy parenting; ii) healthy youth; iii) healthy communities; iv) Elders; v) healing towards wellness; and vi) food sovereignty. The Elders Lodge in the community provides support for holistic wellbeing by promoting intergenerational knowledge transmission, guidance to youth and community members, as well as land-based activities which improve bonding, cultural awareness, and mental and spiritual well-being among community members. The Elders Lodge hosts both drop-in and organized events.

Several initiatives have been developed to support food sovereignty in the community, including a greenhouse program where fruits and vegetables are grown and shared locally. This program is run in partnership with the school to increase food knowledge and skills among youth. In addition, after-school programs including traditional food education (i.e., cooking classes) and land-based activities (i.e., berry picking) led by Elders support the goals of the wellness model. The community is currently working on developing additional programs dedicated to improving mental wellness among adults, youth, and Elders.

Barriers to community health

When key informants were asked to identify barriers to community health, they described delays in access to timely health information. For example, daily COVID-19 tests conducted at the regional health centre in Île-à-la-Crosse were relayed to the provincial health authority; however, information about the total number of COVID-19 cases could take up to one week to be sent back to the community. This time lag restricted community decision-makers’ ability to enact timely policy (i.e., contact tracing) and rapidly respond to managing cases.

A second barrier that was raised by community members was a delay in access to timely healthcare. The Île-à-la-Crosse hospital is a regional health service centre serving the community as well as surrounding areas. Community members noted that the load often exceeded the capacity of the single hospital, and some patients and procedures were relocated to hospitals and clinics in the larger city of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. This was reported to be challenging for many community members as it was associated with longer wait times, long commutes, and sometimes required time off work. Many of these challenges were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of the pandemic, many medical centres and hospitals postponed routine and elective medical procedures in an attempt to accommodate the overwhelming influx of patients who contracted COVID-19. In addition, community members were advised to avoid spending time in health centres to limit risk of exposure to the virus. These COVID-related changes further delayed access to timely healthcare for many community members of Île-à-la-Crosse.

Several community members reported experiencing institutional racism in healthcare and social service settings outside of Île-à-la-Crosse. This was particularly exacerbated during the COVID-19 movement restrictions, where community members faced significant difficulties in accessing services and care in larger urban centres, and experienced further discrimination due to the stigma of COVID-19-related rumours about communities in the north.

Lastly, community members discussed a lack of awareness about some health topics, including where and how to access reliable health information. Some community members attributed this lack of awareness to a general distrust in government health information due to a history of colonialism and exploitation in Canada, which likely contributed to increased misinformation about COVID-19 risk and spread.

Health communication

The primary modes of communication within Île-à-la-Crosse are radio and social media. These platforms were used throughout the pandemic to communicate health information about COVID-19 case counts and trends. Community members also reported obtaining health information from healthcare practitioners (i.e., for those already visiting a healthcare provider), Elders, and the internet. Key informants indicated an interest in improving digital infrastructure to enable sharing of timely and accurate health information with community members and minimize misinformation. Key informants also reported room for improvement in the community’s digital health infrastructure, particularly in improving timely communication with community members, and to inform decision-making in crisis situations.

Digital infrastructure and connectivity

Île-à-la-Crosse has its own cell tower which offers reliable access to cellular data. The community also has access to internet via the provincial internet provider–SaskTel, as well as a local internet provider—Île-à-la-Crosse Communications Society Inc. Key informants and community members confirmed that most individuals above 13 years of age have access to smartphones, and that these mobile devices are the primary mode of internet access. However, it was unclear whether everyone who owns smartphones also has consistent data plans or home internet connections. Key informants described the great potential of digital devices like smartphones to increase the speed and accuracy of information sharing. Discussions with both key informants and community members suggested the need for a community-specific app or platform which could provide timely health information that was tailored to the community’s needs.