The strongest argument against same-sex marriage: traditional marriage is in the public interest

by German Lopez

Opponents of same-sex marriage argued that individual states are acting in the public interest by encouraging heterosexual relationships through marriage policies, so voters and legislators in each state should be able to set their own laws.

Some groups, such as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, cited the secular benefits of heterosexual marriages, particularly the ability of heterosexual couples to reproduce, as Daniel Silliman reported at the Washington Post .

”It is a mistake to characterize laws defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman as somehow embodying a purely religious viewpoint over against a purely secular one,” the bishops said in their amicus brief . “Rather, it is a common sense reflection of the fact that [homosexual] relationships do not result in the birth of children, or establish households where a child will be raised by its birth mother and father.”

Other groups, like the conservative Family Research Council, warned that allowing same-sex couples to marry would lead to the breakdown of traditional families. But keeping marriage to heterosexual couples, FRC argued in an amicus brief , allows states to “channel the potential procreative sexual activity of opposite-sex couples into stable relationships in which the children so procreated may be raised by their biological mothers and fathers.”

To defend same-sex marriage bans, opponents had to convince courts that there’s a compelling state interest in encouraging heterosexual relationships that isn’t really about discriminating against same-sex couples.

But a majority of Supreme Court justices and most of the lower courts widely rejected this argument, arguing that same-sex marriage bans are discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Most Popular

The supreme court’s disastrous trump immunity decision, explained, the supreme court also handed down a hugely important first amendment case today, hawk tuah girl, explained by straight dudes, the caribbean has a defense system against deadly hurricanes — but it’s vanishing, delete your dating apps and find romance offline, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in archives

The Supreme Court will decide if the government can ban transgender health care

On the Money

Total solar eclipse passes over US

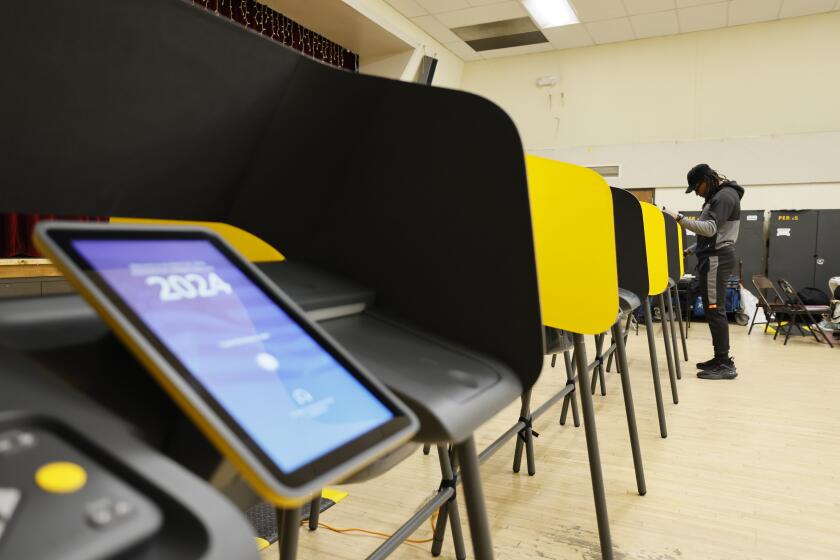

The 2024 Iowa caucuses

The Big Squeeze

Abortion medication in America: News and updates

Do other Democrats actually do better against Trump than Biden?

How white victimhood is shaping a second Trump term

If it’s 100 degrees out, does your boss have to give you a break? Probably not.

Hurricane Beryl is the terrifying storm that scientists have been expecting

5 terrible reasons for Biden to stay in the race

Good Disagreement: The Same-Sex Marriage Debate Shows We Still Have a Long Way to Go

Joel Harrison

- X (formerly Twitter)

Joel Harrison is Senior Lecturer in the Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University, Sydney.

Australia has now completed its postal survey "vote" on whether marriage should be redefined at law to include the union of two persons of the same sex. 61.6% are in favour of the change.

In the wake of the result, we should spend time reflecting on the nature of the debate and what lessons it may hold for civic - and civil - engagement. In particular, what did this debate reveal about our capacity for respectful conversation ?

Advocates on both sides of the question repeatedly used this term as an aspiration, also indicating that there was a conversation to be had. However, both No and Yes groups claimed offence, vilification and bullying .

This is not surprising. I want to suggest at least two structural and conceptual reasons why the postal survey was ill-suited to engendering respectful conversation. Both reasons transcend the current issue of same-sex marriage, relating more generally to how we engage in moral debates.

First, the debate was characterised by an emphasis on "getting out the vote" or marshalling one's own side; and second, claims of offence and bigotry are how we often stake a political argument in an age focused on rights (or, more specifically, rights-talk of a certain brand).

In contrast, I want to consider an alternative. A truly respectful conversation will be one that sees the task before us as a collective endeavour. In this case: a quest, however contested, to understand the relationship between the good of marriage, the ends of the person, and the goal of politics or formation of a community. In such a conversation, we are responsible to each other in at least two ways: first, rather than simply asserting a subjective right, we are all seeking to understand an objective, shared good, one central to our political community or common life; second, as such, we may see the other person not as an enemy (the "religious bigot" or the "radical gay propagandist"), but as an interlocutor refining our own argument or offering something for contemplation.

But such a conversation arguably also requires shared space for deliberation. We not only need a shared language or goal, but sites for encountering one another in order to cultivate the sense that the other person is someone whose flourishing I have an interest in or care for.

This kind of conversation was arguably not evident recently in Australia, but it is possible.

"Get out the vote"

The very use of a plebiscite - or, in this case, a postal survey - was contentious . In our parliamentary democracy, persons are elected to take part in deliberation orientated towards passing laws for the common good. This entails exercising wisdom - leading popular opinion as much as reflecting on it - in order to discern what that good requires. Indeed, such an exercise requires being attentive to different communities and their claims.

Instead, before reaching this form of deliberation, we have had a postal survey. Here, deliberation is largely replaced with attempting to marshal one's side or "get out the vote." Campaigners have been explicit , stating they were targeting those likely to have sympathy for their position.

This follows from reducing moral and political deliberation down to, ultimately, a yes-no binary. Of course, there may be attempts to engage with and persuade those who disagree, but such attempts are surely rarer when the task is simply one of securing votes.

Doing so can largely take the form of galvanising the base with (sometimes ambiguous) horror stories, explosive wording, "right side of history" claims, or blatant attempts to engage in civic alienation - determining who are the friends and who are the enemies. Such galvanising tactics have typified the Coalition for Marriage , campaigning for a No vote. Its repeated exhortations against "radical gay sex" during the postal survey can only be understood as attempts to rally the troops against a spectre of ambiguous import.

Indeed, the act of persuasion becomes almost entirely an appeal to caution, if not fear. Of course, changing the definition of marriage does raise important questions concerning education and religious liberty. But the Coalition for Marriage's campaign, judging by its publicly available resources, explicitly targeted these concerns alone and did so more in the vein of political slogans - flyers and videos to stir those already committed or those amenable to the messaging. Perhaps ironically, given it is the Coalition for Marriage, material on what marriage is and why this is a good - indeed, something attractive - did not feature heavily in its campaign. Such attempts were instead made by individuals .

Within this context, appeals to respectful conversation appear to have a distinct meaning. They largely seem to concern the liberty to state a view, arguably in order to marshal the base, with the proviso that this must not amount to vilification. Here, the postal survey, with its crystallising of our current debate into a push for Yes and No votes, highlighted how for some the political task has become simply the goal of winning through securing numbers.

Rights-talk

But there is, I think, a second reason why respectful conversation has become difficult: the reigning concepts employed arguably hinder it. In our current debate, rights-talk is particularly prominent. In one banal sense, this is inevitable. Amending the Marriage Act 1961 would create a new rights-claim, entailing a duty on the part of the state to recognise a union between any two persons under the Act as a valid legal marriage.

But the appeal to rights ordinarily says much more than this; typically rights-talk is appealed to as the justification for changing the Marriage Act . For example, in her Monthly essay , Senator Penny Wong principally refers to the "equal treatment of people" which requires "granting the same rights."

What, then, does equality of rights mean? Of course, rights discourse is complicated by different strands or traditions of argument that shape the purpose and content of rights-claims; there is no settled meaning. For example, some have argued that a right to marry is a right to participate in a conditioned role or responsibility that entails certain duties to the spouse and children. On this (typically more Catholic) view, the duty is primary. The purpose of marriage is inferred from the natural relations between men and women, and the building of a community; marriage exists to sustain children and a tradition. But appeals to rights in the current debate typically draw from a different tradition of argument - call it liberal egalitarian .

Senator Wong goes on to appeal to Obergefell , the United States Supreme Court's decision holding that states must extend the status of marriage to same-sex couples. For the majority in that decision, Justice Kennedy stated, "the right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy." This was not the Court's sole proposition; however, it was the guiding light or principle. A right is linked to the "liberty ... to define and express ... identity." Marriage is cast as one form of intimate decision central to this. It thus serves the underlying goal of what others have referred to as self-actualisation, self-fashioning, or facilitating different lifestyles. Equality consequently means equal regard or respect for a person's (at least intimate) choices.

Rights-talk is often characterised as a neutral language, transcending different religious and non-religious views. It appears well-suited to the reality of no single view achieving universal acceptance. But I suggest that rights-talk of the kind just described, arguably a dominant strand, can engender conflict and inhibit dialogue.

A person may argue that a choice is not conducive to human flourishing, personally and socially. However, if rights are directed towards equal respect for an individual's freedom to cultivate his or her understanding of the good life, then this moral claim may be characterised as imposing an "external preference" (to borrow from the late Ronald Dworkin) upon the ethical preferences of another individual. Such claims then register in public discourse, and legal decisions, as statements that the other is of less worth because an ethical choice is not being respected.

Framed in this way, rights-talk can contribute to what Steven Smith has called a "discourse of denigration." The strongest available argument is to cast one's opponent as engaging in hate. Thus the prevalence of "bigot" in public discourse. Of course, such bigotry and denigration does exist - homophobia is real, as is animus against religious persons. But the label is frequently extended to an opposing view as such. The person arguing marriage is a union between persons of the opposite sex is not simply raising a definitional or ontological argument, but is rights-limiting, imposing a preference on the freedom of another, and thus denigrating another's identity. In return, this precipitates a counter-claim of bigotry, sourced both in the original claim - labelling one's opponent a bigot is itself a form of bigotry - and any attendant denial of the right to religious liberty.

Unsurprisingly, then, much of our current political argument registers as claims of offence and protest. By this I do not mean protest necessarily linked to a shared good - for example, care of the planet or a cessation of war. Rather, what we now increasingly see in a debate like this is the potential for an almost wholly "negative" phenomenon of protesting against offence occasioned by the rejection of one's own ethical choices. Solidarity is found - and votes marshalled - in mutual offence at, for example, someone believing that children are ideally raised by a biological father and mother or questioning the influence of a person's religious beliefs.

This is deeply ironic. Rights-talk of the kind I am discussing is grounded in equal regard for another's identity. And yet what we actually have much of the time is mutual disrespect . Indeed, if rights-talk refers to respecting an individual's self-actualisation or ethical freedom, then we arguably do not need to engage the substance of the person's actual argument. Rather, each claim is simply a matter of respecting, as far as possible, self-defining.

This presents questions of law: how do we "balance" what are arguably structurally similar claims, if our concern is ethical freedom, namely same-sex marriage and religious liberty? But we are arguably beyond respecting - by, in fact, engaging - the other person's substantive view.

Good disagreement

The alternative is to understand our conversation as a shared endeavour. I have argued that our current debate has two features: politics as simply an interest in securing one's base to win, and a focus on a rights discourse that reflects arguments of personal autonomy and private choice. In contrast, focusing together on the substantive moral question (what is marriage? how does it relate to our common life?) allows, I suggest, for a kind of displaced agreement. Participants may not agree on a particular conclusion - here, whether marriage can extend to a same-sex couple. Nevertheless, they may agree in part, agree on the moral vocabulary, or agree that the differing party is conscientiously pursuing a real human good. This would contribute to what the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, calls "good disagreement."

A conversation of this kind can be fruitful. Here, I am drawing from the structuring of debates within parts of the Anglican Communion. Some churches have grappled with what it means to disagree, while nevertheless seeking and affirming a "right" position. While these debates are not perfect, I think they offer potential insights for our political communities.

Consider, first, how the argument of "traditionalists" argument clearly points to two matters that may make a "revisionist" pause: the status of objective goods in our common life, and the importance of marriage to a civil society independent of the sway of government and market.

Traditionalists argue marriage points to a fundamental unity-in-differentiation. Marriage draws together the two halves of the human race (as the typical cases) in a union that gives positive meaning to gender difference: we need each other, which is then most centrally expressed in the common endeavour of procreation and child-rearing. On this account, marriage is fundamentally "traditional." As John Milbank has argued, it entails forming kinship structures, transmitting virtue and a tradition, and the continuity of humanity itself from one generation to the next.

Framed in this way, the traditionalist argument clearly points to genuine, desirable human goods. Indeed, importantly, it typically contends that marriage is an objective good purposed towards particular ends. This raises a fundamental question in our debates: are there goods whose nature or shaping is not simply a matter of individual will?

Liberal-egalitarian rights-talk in this field can be construed as respecting the choice to enter into a status (marriage). However, there is also more than a hint that this respect extends to the individual's own understanding of what that status is. Such a determination is part of a person's capacity to "define one's own concept of existence." Some commentators then echo this by grounding marriage in contract, which casts marriage as an agreement entailing the allocation of rights and duties as determined by individual willing.

For the traditionalist, this is rank individualism. It adopts a mistaken view of freedom as the absence of restraint, rather than the pursuit of what is truly good. And this view, at one with a neo-liberal focus on choice, then clearly relates to changing practices of child-bearing, which in turn affects the political meaning of the family.

On the traditionalist account, marriage as an objective good entails the potential for a child who is uniquely of these two people. Marriage is political because it is the basis for forming and extending communities; it is our first society. But uncoupling marriage from gender-differentiation (for example, rendering it a matter of contract) potentially transforms parenthood from a matter of natural affinity, with a relative independence and authority, into a subject under the sway of commercial enterprise, contractual design, and state regulation and recognition.

Revisionists can and have responded to these claims.

For example, I have noted previously a consistent thread of argument that characterises marriage as a school of virtue. Marriage on this account is a humanising act - it teaches us, through intimacy with a spouse, what it means to be a person, rightly formed. It orientates us towards our right end of human flourishing - a life characterised by fidelity, patience and charity, for example. It teaches us the disciplines necessary to achieve this. It awakens "knowing yourself to be seen in a certain way: as significant, as wanted." And, in turn, it entails learning to accord and recognise the worth of the other. Thus the Book of Common Prayer states, "With my body, I thee worship."

Grounded in such mutual love and support, the marriage partners can then be a gift to the community. On this, the biopolitical concern of state and market sway over parenthood can be accepted as real, but not inevitable. As a gift to our common life, the marriage may not entail child-rearing at all, or, if it does, it may focus on adoption as a vocation. (Indeed, this would be consistent with biblical images of marriage, which typically do not depend on child-bearing, but point to faithfulness and a place for erotic desire.)

Importantly, here traditionalist claims are not "overcome" by an appeal to rights discourse. Rather, the traditionalist claims are taken seriously, as a partner seeking common meaning. This means the revisionist argument, focused in this way, also discusses marriage as an objective good fundamental to our common life. As Sarah Coakley has noted, it remains "traditional."

I am suggesting, then, that a more respectful conversation - if that is our goal - is furthered by attending to and cultivating a shared language. Here our disagreements may not amount to simply claims of rights-limited, but rather contested conclusions in a shared project: understanding marriage and its importance. Indeed, each side may then be pointing to something right, something of a shared concern or even desire. This does not mean agreement, but it does point to the possibility of some shared norms. And if there can be mutual recognition of the other's argument this should make us more open to the possibility of conscientious difference and disagreement, even as we continue to seek to persuade.

But a respectful conversation arguably requires more than attentiveness to the contours of a debate; it requires a context for this. It requires, in other words, time, space and encounter - all things that arguably were lacking in the compressed context of a postal survey.

For those who see same-sex marriage as a pressing matter of justice, the wait has been too long. This is understandable, but if we are to take conscientious difference seriously and engender a respectful conversation, then time is needed. One unfortunate characteristic of the current debate is the absence of the rhetorical virtue of decorum . Speaking generally, John Perry describes "the arrogant assumption by some that they have been there from the beginning and therefore control the terms of discussion, as well as the foolishness of the newcomer who doesn't wait and listen for long enough to hear what the argument is about." Simply understanding the moral claims, lines of argument and implications from argument found in this debate takes time. But the need for time extends also to building relationships across an "opposing" side.

Reflecting on the parallel debates in the Anglican Communion, Justin Welby refers to "an honest reinforcement of the bonds of relationship." Our moral debates, while fraught, are also an exercise in virtue . Respecting the other person in conversation means cultivating the capacity to care for the other person. This is consistent with understanding our conversation as shared . We share a common life, and so should be concerned with sustaining bonds of trust and even affection. We may come to understand our interlocutors as not simply the holder of a competing view, but as someone who as a member of my community may be a gift to me. They may illuminate a question in surprising ways. Moreover, they may contribute to what Iris Murdoch called "moral perfection." Through active attending to the other person, I may come to see them "justly and lovingly" - virtues that, as she argued, are fundamental to being a person.

That would typically mean cultivating shared spaces for encounter. We may think of this tangibly. Rather than the echo chamber of social media, let alone the world of robocalls and pamphleteering, actively attending to those who share with us the project of discerning and debating right is more likely done in the act of sitting at a table (or in a pew), at which the other person is immediately before us and concrete.

This is not to say that conversation will lead to some kind of middle-of-the-road agreement. Such conversations are not divorced from pursuing the truth. Indeed, from a perspective of Christian political ethics, if not more widely, we are concerned with articulating right - that is, asking what justice requires, understood as discerning right relations within a created order. This requires engaging in criticism where justice goes awry and then arguing for what is right.

However, Christian thought emphasises within this the cultivation of virtues. We are in right relationship not simply when we have reinforced a position with those in agreement, but when we have acted out of an attentive love or else care for mutual flourishing. Respectful conversation consequently means understanding that what is cultivated - the character of the person and of the polity - is an end in itself.

Opinion: As conservatives target same-sex marriage, its power is only getting clearer

- Copy Link URL Copied!

It’s been two years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Dobbs case that overturned the federal right to an abortion, and the troubling concurring opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas in which he expressed a desire to “revisit” other landmark precedents, including the freedom to marry for same-sex couples, codified nationally by the Obergefell Supreme Court decision, nine years ago Wednesday

Since that ruling, the LGBTQ+ and allied community has done much to protect the fundamental freedom to marry — passing the Respect for Marriage Act in Congress in 2022; sharing their stories this year to mark the 20th anniversary of the first state legalization of same-sex marriages, in Massachusetts; and in California , Hawaii and Colorado launching ballot campaigns to repeal dormant but still-on-the-books anti-marriage constitutional amendments.

California Democratic Party endorses ballot measures on same-sex marriage, taxes, rent control

The party’s executive board voted Sunday on which measures they would endorse.

May 19, 2024

This winter, I worked with a team at the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law to survey nearly 500 married LGBTQ+ people about their relationships. Respondents included couples from every state in the country; on average they had been together for more than 16 years and married for more than nine years. Sixty-two percent married after the court’s 2015 Obergefell marriage decision, although their relationships started before before that. More than 30% of the couples had children and another 25% wanted children in the future.

One finding that jumped out of the data: Almost 80% of married same-sex couples surveyed said they were “very” or “somewhat” concerned about the Obergefell decision being overturned. Around a quarter of them said they’d taken action to shore up their family’s legal protections — pursuing a second-parent adoption, having children earlier than originally planned or marrying on a faster-than-expected timeline — because of concerns about marriage equality being challenged. One respondent said, “We got engaged the day that the Supreme Court ruled on the Dobbs decision and got married one week after.”

World & Nation

Same-sex marriage ruling creates new constitutional liberty

The Supreme Court’s historic ruling Friday granting gays and lesbians an equal right to marry nationwide puts an exclamation point on a profound shift in law and public attitudes, and creates the most significant and controversial new constitutional liberty in more than a generation.

June 26, 2015

As we examined the survey results, it became clearer than ever why LGBTQ+ families and same-sex couples are fighting so hard to protect marriage access — and the answer is really quite simple: The freedom to marry has been transformative for them. It has not only granted them hundreds of additional rights and responsibilities, but it has also strengthened their bonds in very real ways.

Nearly every person surveyed (93%) said they married for love; three-quarters added that they married for companionship or legal protections. When asked how marriage changed their lives, 83% reported positive changes in their sense of safety and security, and 75% reported positive changes in terms of life satisfaction. “I feel secure in our relationship in a way I never thought would be possible,” one participant told us. “I love being married.”

The evolution of same-sex marriage

I’ve been studying LGBTQ+ people and families for my entire career — and even still, many of the findings of the survey touched and inspired me.

Individual respondents talked about the ways that marriage expanded their personal family networks, granting them (for better and worse!) an additional set of parents, siblings and loved ones. More than 40% relied on each other’s families of origin in times of financial or healthcare crisis, or to help out with childcare. Some told of in-laws who provided financial assistance to buy a house, or cared for them while they were undergoing chemotherapy for cancer.

Analysis:: Antonin Scalia’s dissent in same-sex marriage ruling even more scornful than usual

The legal world may have become inured to wildly rhetorical opinions by Justice Antonin Scalia, but his dissent in the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage decision Friday reaches new heights for its expression of utter contempt for the majority of his colleagues.

And then there was the effect on children. Many respondents explained that their marriage has provided security for their children, and dignity and respect for the family unit. Marriage enabled parents to share child-rearing responsibilities — to take turns being the primary earner (and carrying the health insurance), and spending more time at home with the kids.

The big takeaway from this study is that same-sex couples have a lot on the line when it comes to the freedom to marry — and they’re going to do everything possible to ensure that future political shifts don’t interfere with their lives. As couples across the country continue to speak out, share their stories — and in California, head to the ballot box in November to protect their hard-earned freedoms — it’s clear to me that it’s because they believe wholeheartedly, and with good reason, that their lives depend on it.

Abbie E. Goldberg is an affiliated scholar at the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law and a psychology professor at Clark University, where she directs the women’s and gender studies.

More to Read

Opinion: Interracial marriage went from criminal to commonplace. Could it go back?

June 9, 2024

Newsom urges California voters to protect same-sex marriage amid Supreme Court distrust

June 7, 2024

The U.S. has caught up to California on views of LGBTQ+ rights, poll shows

June 6, 2024

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

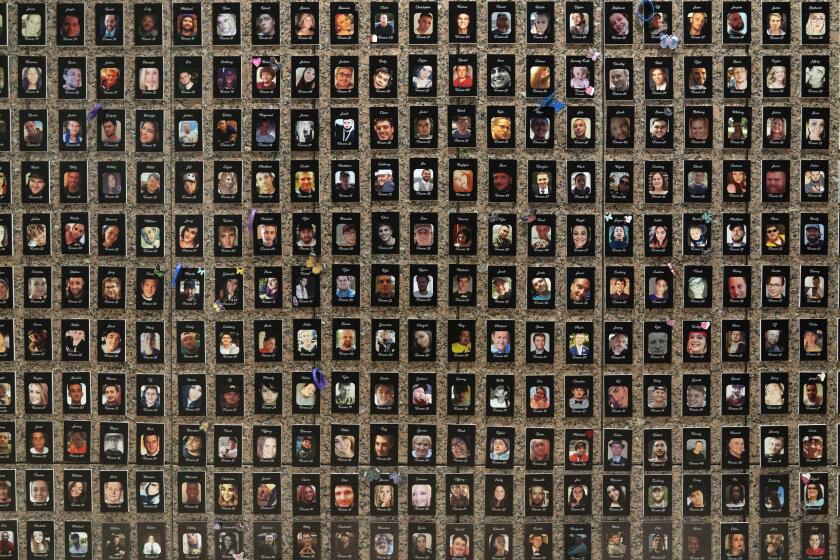

Opinion: Fentanyl could fuel another cycle of loss in L.A.’s Black communities. It doesn’t have to

July 2, 2024

Opinion: Wildfire smoke kills thousands of Californians a year. It doesn’t have to be so deadly

Goldberg: How Democrats’ defense of Biden reminds me of Republicans rallying around Trump

Litman: After the Supreme Court’s immunity ruling, can Donald Trump still be tried for Jan. 6?

July 1, 2024

Evidence is clear on the benefits of legalising same-sex marriage

PhD Candidate, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University

Disclosure statement

Ryan Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

James Cook University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Emotive arguments and questionable rhetoric often characterise debates over same-sex marriage. But few attempts have been made to dispassionately dissect the issue from an academic, science-based perspective.

Regardless of which side of the fence you fall on, the more robust, rigorous and reliable information that is publicly available, the better.

There are considerable mental health and wellbeing benefits conferred on those in the fortunate position of being able to marry legally. And there are associated deleterious impacts of being denied this opportunity.

Although it would be irresponsible to suggest the research is unanimous, the majority is either noncommittal (unclear conclusions) or demonstrates the benefits of same-sex marriage.

Further reading: Conservatives prevail to hold back the tide on same-sex marriage

What does the research say?

Widescale research suggests that members of the LGBTQ community generally experience worse mental health outcomes than their heterosexual counterparts. This is possibly due to the stigmatisation they receive.

The mental health benefits of marriage generally are well-documented . In 2009, the American Medical Association officially recognised that excluding sexual minorities from marriage was significantly contributing to the overall poor health among same-sex households compared to heterosexual households.

Converging lines of evidence also suggest that sexual orientation stigma and discrimination are at least associated with increased psychological distress and a generally decreased quality of life among lesbians and gay men.

A US study that surveyed more than 36,000 people aged 18-70 found lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals were far less psychologically distressed if they were in a legally recognised same-sex marriage than if they were not. Married heterosexuals were less distressed than either of these groups.

So, it would seem that being in a legally recognised same-sex marriage can at least partly overcome the substantial health disparity between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

The authors concluded by urging other researchers to consider same-sex marriage as a public health issue.

A review of the research examining the impact of marriage denial on the health and wellbeing of gay men and lesbians conceded that marriage equality is a profoundly complex and nuanced issue. But, it argued that depriving lesbians and gay men the tangible (and intangible) benefits of marriage is not only an act of discrimination – it also:

disadvantages them by restricting their citizenship;

hinders their mental health, wellbeing, and social mobility; and

generally disenfranchises them from various cultural, legal, economic and political aspects of their lives.

Of further concern is research finding that in comparison to lesbian, gay and bisexual respondents living in areas where gay marriage was allowed, living in areas where it was banned was associated with significantly higher rates of:

mood disorders (36% higher);

psychiatric comorbidity – that is, multiple mental health conditions (36% higher); and

anxiety disorders (248% higher).

But what about the kids?

Opponents of same-sex marriage often argue that children raised in same-sex households perform worse on a variety of life outcome measures when compared to those raised in a heterosexual household. There is some merit to this argument.

In terms of education and general measures of success, the literature isn’t entirely unanimous. However, most studies have found that on these metrics there is no difference between children raised by same-sex or opposite-sex parents.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association released a brief reviewing research on same-sex parenting. It unambiguously summed up its stance on the issue of whether or not same-sex parenting negatively impacts children:

Not a single study has found children of lesbian or gay parents to be disadvantaged in any significant respect relative to children of heterosexual parents.

Further reading: Same-sex couples and their children: what does the evidence tell us?

Drawing conclusions

Same-sex marriage has already been legalised in 23 countries around the world , inhabited by more than 760 million people.

Despite the above studies positively linking marriage with wellbeing, it may be premature to definitively assert causality .

But overall, the evidence is fairly clear. Same-sex marriage leads to a host of social and even public health benefits, including a range of advantages for mental health and wellbeing. The benefits accrue to society as a whole, whether you are in a same-sex relationship or not.

As the body of research in support of same-sex marriage continues to grow, the case in favour of it becomes stronger.

- Human rights

- Same-sex marriage

- Same-sex marriage plebiscite

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Lecturer in Visual Art

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

An Overview of the Same-Sex Marriage Debate

by David Masci, Senior Research Fellow, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ignited a nationwide debate in late 2003 when it ruled that the state must allow gay and lesbian couples to marry. Almost overnight, same-sex marriage became a major national issue, pitting religious and social conservatives against gay-rights advocates and their allies. Over the next year, the ensuing battle over gay marriage could be heard in the halls of the U.S. Congress, in dozens of state legislatures and in the rhetoric of election campaigns at the national and state level.

The debate over same-sex marriage shows no signs of abating. In California, for instance, a high-profile case challenging the constitutionality of a state law banning same-sex marriage was argued before the state’s highest court in early March 2008, with a decision expected by May. 1 A similar suit is on the verge of being decided by Connecticut’s Supreme Court. In addition, Florida will hold a referendum during the November 2008 election on a state constitutional amendment that would prohibit gay marriage. Other states, such as Arizona and Indiana, are considering putting similar referenda on the November ballot.

Supporters of same-sex marriage contend that gay and lesbian couples should be treated no differently than their heterosexual counterparts and that they should be able to marry like anyone else. Beyond wanting to uphold the principle of nondiscrimination and equal treatment, supporters say that there are very practical reasons behind the fight for marriage equity. They point out, for instance, that homosexual couples who have been together for years often find themselves without the basic rights and privileges that are currently enjoyed by heterosexual couples who legally marry — from the sharing of health and pension benefits to hospital visitation rights.

Social conservatives and others who oppose same-sex unions assert that marriage between a man and a woman is the bedrock of a healthy society because it leads to stable families and, ultimately, to children who grow up to be productive adults. Allowing gay and lesbian couples to wed, they argue, will radically redefine marriage and further weaken it at a time when the institution is already in deep trouble due to high divorce rates and the significant number of out-of-wedlock births. Moreover, they predict, giving gay couples the right to marry will ultimately lead to granting people in polygamous and other nontraditional relationships the right to marry as well.

The American religious community is deeply divided over the issue of same-sex marriage. The Catholic Church and evangelical Christian groups have played a leading role in public opposition to gay marriage, while mainline Protestant churches and other religious groups wrestle with whether to ordain gay clergy and perform same-sex marriage ceremonies. Indeed, the ordination and marriage of gay persons has been a growing wedge between the socially liberal and conservative wings of the Episcopal and Presbyterian churches, leading some conservative congregations and even whole dioceses to break away from their national churches. 2

Polls show that frequency of worship service attendance is a factor in the opposition to gay marriage. According to an August 2007 survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life and the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 55% of Americans oppose gay marriage, with 36% favoring it. But those with a high frequency of church attendance oppose it by a substantially wider margin (73% in opposition vs. 21% in favor). Opposition among white evangelicals, regardless of frequency of church attendance, is even higher — at 81%. A majority of black Protestants (64%) and Latino Catholics (52%) 3 also oppose gay marriage, as do pluralities of white, non-Hispanic Catholics (49%) and white mainline Protestants (47%). Only among Americans without a religious affiliation does a majority (60%) express support.

However, a 2006 Pew survey found that sizable majorities of white mainline Protestants (66%), Catholics (63%) and those without a religious affiliation (78%) favor allowing homosexual couples to enter into civil unions that grant most of the legal rights of marriage without the title. The general public also supports civil unions (54% in favor vs. 42% in opposition). As with gay marriage, white evangelicals (66%), black Protestants (62%) and frequent church attenders (60%) stand out for their opposition to civil unions. 4

The same-sex marriage debate is not solely an American phenomenon. Many countries, especially in Europe, have grappled with the issue as well. And since 2001, four nations — the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and South Africa — have legalized gay marriage. In addition, the provinces of Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec in Canada now allow same-sex couples to legally marry. 5

The Debate Begins

Gay Americans have been calling for the right to marry, or at least to create more formalized relationships, since the 1960s, but same-sex marriage has only emerged as a national issue in the last 15 years. The spark that started the debate came from Hawaii in 1993 when the state’s Supreme Court ruled that an existing law banning same-sex marriage would be unconstitutional unless the state government could show that it had a compelling reason for discriminating against gay and lesbian couples.

Even though this decision did not immediately lead to the legalization of gay marriage in the state (the case was sent back to a lower court for further consideration), it did spark a nationwide backlash. Over the next decade, legislatures in more than 40 states passed what are generally called Defense of Marriage Acts (DOMAs), which define marriage solely as the union between a man and a woman. Today, 42 states have DOMAs on the books. In addition, in 1996 the U.S. Congress passed, and President Bill Clinton signed, a federal DOMA that defines marriage for purposes of federal law as the union between a man and a woman. The law also asserts that no state can be forced to legally recognize a same-sex marriage performed in another state.

Beginning in the late 1990s, Alaska, Nebraska and Nevada amended their state constitutions to prohibit same-sex marriage. These constitutional changes were aimed at taking the issue out of the hands of judges. Conservatives, in particular, feared that without constitutional language specifically defining marriage, many judges would take it upon themselves to read other constitutional provisions broadly and “create” a right to same-sex marriage.

Amid widespread efforts in many states to prevent same-sex marriage, there was at least one notable victory for gay-rights advocates during this period. In 1999, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that gay and lesbian couples are entitled to all of the rights and protections associated with marriage. However, the court left it up to the state legislature to determine how to grant these rights to same-sex couples. The following year, the Vermont legislature approved a bill granting gay and lesbian couples the right to form civil unions. Under Vermont’s law, same-sex couples who enter into a civil union accrue all the rights, benefits and responsibilities of marriage, though they are not technically married.

The Goodridge Case and its Aftermath

Although the debate over gay marriage for a while seemed to fade from the public eye, the issue was suddenly and dramatically catapulted back into the headlines in November 2003 when the highest state court in Massachusetts ruled that the state’s constitution guaranteed gay and lesbian couples the right to marry. Unlike the Vermont high court’s decision four years earlier, the ruling in this case, Goodridge v. Massachusetts Department of Public Health , left the legislature no options, requiring it to pass a law granting full marriage rights to same-sex couples. 6

In the days and weeks following the 2003 Massachusetts decision, some cities and localities — including San Francisco, CA; Portland, Ore.; and New Paltz, N.Y. — began issuing marriage licenses to gay couples. Television images of long lines of same-sex couples waiting for marriage licenses outside of government offices led some social conservatives and others to predict that same-sex marriage would soon be a reality in many parts of the country. But these predictions proved premature.

To begin with, all the marriage licenses issued to gay couples outside of Massachusetts were later nullified since none of the mayors and other officials involved had the authority to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples. More significantly, the Massachusetts decision led to another major backlash at the federal and state level. In the U.S. Congress, conservative lawmakers, with support from President Bush, attempted to pass an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would have banned same-sex marriage nationwide. But efforts to obtain the two-thirds majority needed in both houses to pass the amendment fell short in 2004 and again in 2006.

Gay-marriage opponents had better luck at the state level, where voters in 13 states passed referenda in 2004 amending their constitutions to prohibit same-sex marriage. Ten more states took the same step in 2005 and 2006, bringing the total number of states with amendments prohibiting gay marriage to 26. So far, voters in only one state — Arizona in 2006 — have rejected a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. And only New Mexico, New York and Rhode Island have no law either banning or allowing gay marriage.

The same-sex marriage debate may have had an impact on the outcome of the 2004 presidential election. Ohio, which in 2004 was holding a referendum on a constitutional ban on gay marriage, was the state that ultimately gave President Bush the electoral votes he needed to beat Sen. John Kerry. Bush, who narrowly won the state, opposed gay marriage and supported a federal constitutional amendment banning it. Kerry also came out against gay marriage but opposed the constitutional ban and supported civil unions. It has been noted that the president’s share of the black vote in Ohio (16%) was more than his share of the black vote nationwide (11%). Many political analysts attribute Bush’s narrow victory in Ohio at least in part to the fact that some pastors, particularly black pastors, made same-sex marriage a campaign issue, prompting more of their congregants to vote for Bush.

Most of the states that approved constitutional amendments banning gay marriage are in the more socially conservative South and Midwest. In more socially liberal states, the cause for same-sex marriage has fared somewhat better. Since 2005, three Northeastern states — Connecticut, New Hampshire and New Jersey — have joined Vermont and passed laws authorizing civil unions. In addition, Maine, Oregon, Washington state and California have enacted domestic partnership statutes that grant many, though not all, the benefits of marriage to registered domestic partners. In 2006, the California legislature also passed legislation authorizing same-sex marriage — so far the only state legislature to do so. But the measure was vetoed by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who said that the issue was best left to the courts.

But state high courts have, so far, declined to follow Massachusetts’ lead and mandate same-sex marriage. Indeed, in the last two years, a number of top courts in more socially liberal states –New York, Washington state and Maryland — have rejected arguments in favor of gay unions. Thus Massachusetts remains the only state that allows same-sex marriage; more than 10,000 gay and lesbian couples have married there since 2004.

The immediate future of the same-sex marriage debate appears, to a large degree, to mirror the recent past. On one hand, gay-rights advocates are now pushing for court victories in California and Connecticut. Meanwhile, opponents are looking to the November 2008 election, seeking to have constitutional gay-marriage bans placed on the ballot in as many as 10 states, including Arizona and Indiana. No one knows how these various efforts will ultimately end. But it is a safe bet that the issue will likely remain a part of the nation’s political and legal landscape for years to come.

Find More Resources on Gay Marriage at pewresearch.org/pewresearch-org/religion

| The constitutional dimensions of the same-sex marriage debate. | Americans continue to oppose gay marriage, but most support civil unions. | ||

| Maps showing state laws on gay marriage, civil unions and domestic partnerships. | A breakdown of 17 major religious groups’ views on gay marriage and the ordination of gay clergy. | ||

| Religion & Politics ’08 offers a comparison of each candidate’s stance on gay marriage. | The legal definition of marriage is in flux, particularly in the developed world. | ||

| A panel of experts discusses the same-sex marriage case before the California Supreme Court. | A history of same-sex marriage laws and court decisions. |

1 See From Griswold to Goodridge : The Constitutional Dimensions of the Same-Sex Marriage Debate .

2 See Religious Groups’ Official Positions on Gay Marriage .

3 See: “ Changing Faiths: Latinos and the Transformation of American Religion ,” Pew Forum and Pew Hispanic Center, conducted in 2006 and published in 2007.

4 See A Stable Majority: Most Americans Still Oppose Same-Sex Marriage .

5 See Same-Sex Marriage: Redefining Marriage Around the World .

6 See From Griswold to Goodridge : The Constitutional Dimensions of the Same-Sex Marriage Debate .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Religion & Social Values

- Same-Sex Marriage

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in Europe

Public opinion on abortion, 8 in 10 americans say religion is losing influence in public life, how people around the world view same-sex marriage, the pope is concerned about climate change. how do u.s. catholics feel about it, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

COMMENTS

But a majority of Supreme Court justices and most of the lower courts widely rejected this argument, arguing that same-sex marriage bans are discriminatory and unconstitutional.

The debate over same-sex marriage in the United States is a contentious one, and advocates on both sides continue to work hard to make their voices heard. To explore the case against gay marriage, the Pew Forum has turned to Rick Santorum, a former U.S. senator from Pennsylvania and now a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Australia has now completed its postal survey on whether marriage should be redefined at law to include the union of two persons of the same sex. What did this debate reveal about our capacity for ...

The debate over same-sex marriage in the United States is a contentious one, and advocates on both sides continue to work hard to make their voices heard. To explore the case for gay marriage, the Pew Forum has turned to Jonathan Rauch, a columnist at The National Journal and guest scholar at The Brookings Institution.

Same-sex marriage undermines the meaning of the traditional family. I oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage. I support a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. Same-sex couples should have the same legal rights to get married as heterosexual couples.

If there is a due process right to marriage, it should be understood as a fundamental right to choose one's spouse-a freedom that same-sex couples should share. But we see a deeper flaw with this argument: there may be no due process right to civil marriage at all, even for different-sex couples.

This ambitious framing paved the way for a gay marriage law in 2005 that made Spain, as The New York Times reported, “the first nation to eliminate all legal distinctions between same-sex and ...

Same-sex marriage ruling creates new constitutional liberty. June 26, 2015. As we examined the survey results, it became clearer than ever why LGBTQ+ families and same-sex couples are fighting so ...

Published: August 21, 2017 3:24pm EDT. Emotive arguments and questionable rhetoric often characterise debates over same-sex marriage. But few attempts have been made to dispassionately dissect...

The same-sex marriage debate is not solely an American phenomenon. Many countries, especially in Europe, have grappled with the issue as well. And since 2001, four nations — the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and South Africa — have legalized gay marriage.