Maintaining Your Focus

To focus your writing, you'll need to know how to narrow your focus, so you don't overwhelm your readers with unnecessary information. Knowing who your readers are and why you are writing will help you stay focused.

A Definition of Focus

Kate Kiefer, English Department, Composition Director 1992 -1995 The focus of the text is also referred to as its thesis, theme, controlling idea, main point. In effect, writers tell readers what territory they plan to cover. That's the focus. A focus can be very narrow--as when a photographer takes a close-up of one mountain flower--or it can be broad --as when the photographer takes a long-range shot of the mountain. In practical writing, the focus is often specified for the writer by the "occasion" for the writing.

In their discussions of focus, writers may use a number of terms: main point, thesis, theme, position statement, and controlling idea. What these terms have in common—and what focus is really all about—is informally known as sticking to the point.

Sticking to the point involves having a clear idea of what you want to write and how you want to write about your topic. While you write, you'll want to keep in mind your supporting details to help your readers better understand your main point.

Coordinating all the aspects of your paper requires you to make each part work with the whole. Imagine your writing is a symphony orchestra in which one out of tune instrument will ruin the sound of the entire performance.

How Audience and Purpose Affect Focus

All readers have expectations. They assume what they read will follow a logical order and support a main idea. For instance, an essay arguing for a second skating rink for hockey players should not present cost figures on how expensive new uniforms have become.

Your audience and writing purpose will help you determine your focus. While it may seem obvious to include certain details, your audience may require specific information. Further, why you are writing will also affect what information you present.

Michel Muraski, Journalism and Technical Communication By articulating the problem, you give yourself focus. You must have done your audience analysis to have asked the question, "What kinds of information does the audience need? What are they going to do with it? Are they going to use it to further their research? Are they going to use it to make a decision?" Once you've identified your audience and what they're going to do with your information, you can refine your problem statement and have a focus. It's a necessary outcome.

Different audiences require different ways of focusing. Let's look at a proposal for a second ice rink in town for hockey players only.

Audience One: City Council

This audience will want to know why another ice rink is necessary. They will need to know how practice hours were shortened due to increases in open skate and lesson hours. They will need to know about new hockey teams forming within the community and requiring practice and game time on the ice. They should also be informed of how much money is made from spectators coming to view the games, as well as of any funding raised by existing hockey teams to help support a new rink. Every detail they read should support why city council should consider building a new rink.

Audience Two: Hockey Coaches and Players

This audience should be informed of the need for a new rink to inspire their support, but chances are they already know of the need. Ultimately, they will want to know what is required of them to get a new rink. How much time will they need to donate to fundraising activities and city council meetings? In addition, they will want to know how they will benefit from a new rink. How will practice hours be increased? Every detail they read should inform them of the benefits a new rink would provide.

Steve Reid, Composition Director 1973-1977 and 1994-1996 Focus, for me, is a term we borrowed from photography. This means we narrow something down to a very sharp image. First, it's a notion of narrowing to something, but also, it's a notion of sharpness and clarity. Focus is one of the things that clarifies purpose. So once we get a sense of thesis, that helps illuminate the photography image, illuminate what the overall purpose of the paper is.

Your purpose is why you are writing about your topic. Different purposes require different ways of focusing. Let's look at a proposal for a second ice rink in town for hockey players only.

Purpose One: Arguing

Proposing a new ice rink to city council members would require convincing them the rink was necessary and affordable. You would need to acknowledge reasons for and against the rink.

Purpose Two: Informing

Informing fellow hockey coaches and players about a new rink would require telling them of the steps being taken to achieve a new rink. This audience most likely knows most of the issues, so selling them on the idea probably won't be necessary. Give them the facts and let them know what they can do to help.

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Department Typically, when I'm writing a report for a person out there, I provide them with the information they need to either increase their knowledge or make a decision. When I talk about focus, I really mean targeting. Here's an example. This comes out of a trade magazine. In Nursing '96 , you'll find articles written by nurses for other nurses. They will generally open with essentially two or three paragraphs. They will say, "You know, here is the problem I had as a nurse in this setting." They tend to set them in what I would consider, soap opera-ish kinds of settings. They set up a real life situation with real people. In other words, "I went into Sally's room and discovered she'd thrown all the covers off the bed and she was sweating profusely." the article goes on to describe what it was. Then it will come back and say, "Here's the problem. Now we've had a number of patients who did this kind of activity, and we found they fell out of bed. To minimize those injuries, here are three things we've done." Then they will give you the summary and then they will elaborate those procedures. That's very targeted. Targeting influences the kind of language used. This means the nurses in the hospital are dealing with "X" kind of patient and "X" kinds of situation. This means a lot of terms and terminology are used. The other nurses reading about this will understand it because of their interest in that topic; it's going to fit them.

Narrowing Your Focus

Writers who cover too much about a topic often overwhelm their readers with information. Take, for example, an essay focused on the tragedies of the Civil War. What tragedies? Readers have no idea what to expect from this focus, not to mention how difficult it would be to write about every tragedy of the Civil War.

After writers choose a topic to write about, they need to make sure they are not covering too much nor too little about a topic. The scope of a focus is partially dictated by the length of the writing. Obviously, a book on the Civil War will cover more than a 500 word essay. Finally, focus is also determined by its significance, that is, its ability to keep readers' interest.

What It Means to be Focused

Donna Lecourt, English Department What it means to be "focused" changes from discipline to discipline. Say for example, in literature, my "focus" comes through a novel. I want to write about Henry James's Turn of the Screw . On one hand it could come through theory. I want to do a feminist analysis and Henry James's Turn of the Screw just happens to be the text I apply it to, or I might add another text. I might just approach a novel and say, "Okay. Everybody's read it in these ways before. Here's yet another way to read it." I don't have to show that I'm adding to, in some ways, I can show I'm distinguishing or coming up with something new. What my "focus" is, is determined disciplinarily as well as by my purpose. Another example would be a typical research report where a "focus" is what's been done before because that determined what an experiment was going to be about. And so, in some ways, you're not coming up with your own "focus" the way in English, in some ways, you can. You have to look at "X," "Y," and "Z" studies to see what was done on this topic before you can prove your point. Focus comes out of what was achieved before. You have to link what you're doing to previous research studies which is a requirement of a lot of research reports.

Focus is Too Broad

Michel Muraski, Journalism and Technical Communication The biggest conceptual shift in most students is having too broad of a statement and literally finding everything they ever knew about this topic and dumping it into a term paper. They need to consider what they write a pro-active document: a document that's going to be used by a specified audience for a specified reason about a specific area of that broader topic.

Kate Kiefer, English Department, Composition Director 1992 -1995 A broad focus looks easier for students, but it turns out that a narrow focus is generally easier. General articles and essays with a broad focus require lots of background information and a pretty clear sense of the readers' goals in reading the piece. Otherwise, writing with a broad focus tends to result in pretty boring prose. Most academic writing requires a narrow focus because it's easier to move from that into the specific supporting detail highly valued in the academic community.

A broad focus covers too much about a topic. It never discusses the fine details necessary to adequately present a topic and keep readers' interest. A good way to narrow a broad topic is to list the subcategories of the topic. For example, two subcategories of Civil War tragedies are:

- The breakdown of families as a result of divided loyalties.

- How the small details of battle strategies affected the outcome of the war.

When you list subcategories, be careful not to narrow your topic too much, otherwise you won't have enough to write about it.

Focus is Too Narrow

A narrow focus covers too little about a topic. It gets so close to the topic that the writer cannot possibly say more than a few words. For example, writing about gender interactions in one of your classes is too narrow. You can use your class to make a point about gender interactions, but chances are, you'll find nothing specific in the library about your particular class. Instead, you might look at gender interactions in group settings, and then use your class as an example to either agree or disagree with your research. Be careful not to make your focus too broad as a result.

As you refine your focus, check to see if you pass the "So What?" test. To do so, you should know who will read what you write. Readers have to care about your topic in order to continue reading, otherwise they may look at what you have written and respond "So what?" You need to determine what readers need to stay interested in your writing. Ask yourself why readers will be interested in your specific topic. Is it significant enough to hold their attention? Why or why not?

Citation Information

Stephen Reid and Dawn Kowalski. (1994-2024). Maintaining Your Focus. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-2024 Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors . Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.

How to Focus on Writing an Essay (Ultimate Guide)

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on Published: February 19, 2022 - Last updated: March 25, 2022

Categories Education , Self Improvement , Writing

One of the main problems students face when writing an essay is a lack of concentration. There is nothing worse than a lack of concentration during a school exam – it can be equally difficult to write an essay when you are already behind and feeling the pressure. Before you start academic writing, whether for school or for college, it is important to find a way to focus on the task at hand. The following tips will help any student focus in order to write a good essay.

Why We Lose Focus

Believe it or not, our minds are programmed by evolution to lose focus because it is a mechanism essential for survival. After processing something we have paid attention to, our brain notices things that are either dangerous or desirable.

In our hunter-gatherer days, when we saw a wild animal, our brain focused on that dangerous animal. When something tasty grew in the forest, our brain focused on that tasty plant.

In the modern world, our brains still try to do their job when we try to write a school paper. But instead of focusing on wild animals, they focus on social media sites, Facebook, and anything else that is considered desirable.

As a result, we pay a high price: It takes anywhere from 5 minutes to 15 minutes or more before we can focus again. Distractions are poison for long periods of concentrated work.

Nor are all distractions external. The opposite is true. About 40 percent of all distractions are internal thought processes. We can get lost in a sea of thoughts that take up all of our attention, which can cause us to stop paying attention to what we should be doing.

This makes it all the more important to find ways to focus on writing the essay, as this helps to keep our thoughts in the right place. And to make sure we write the essays the right way!

7 Ways to Focus While Writing Essays

Essays are an essential writing skill for all students – whether at the level of a college essay or in school. There are a number of things that help us stay focused.

The most important thing is not to wait until the moment before writing to decide what you actually want to say. When writing an essay, you should have a good idea of what you want to say, how you want to say it, and how you want to support your thesis.

If you follow a specific outline when writing your essay, you are much less likely to suffer from writer’s block. You will also be better able to present your arguments clearly and engage in good writing practices, that will serve you well whether you need to tackle an essay or even a research paper.

1. Understand the Esssay Process

It will help you to have a clear idea of the whole process of essay (and non-fiction) writing.

The process is:

- Research : sift through existing arguments and background information relevant to the essay prompt.

- Ideas : Formulate your own arguments and ideas about the essay topic. The main idea will go in your thesis statement, and usually will appear in the Introduction of your essay.

- Outline : create an outline of your main arguments to guide your writing, including citations and references.

- Writing : Write your essay with as much clarity as possible. From the essay introduction all the way down to your final conclusion.

- Revising : Review and edit your essay, getting each body paragraph to flow well and progress your overall argument.

Anyone who has ever written an essay can probably recite these steps in their sleep. But it’s not enough to memorize the process.

2. Avoid Research Recursion Syndrome

Cal Newton, in his book How to Become a Straight-A Student , describes a phenomenon that can lead to endlessly searching for research sources, either out of fear of not having enough – or out of a desire to constantly improve one’s work.

When you do not complete the research process, you embark on a search for sources that consume too much time and energy, which is detrimental to the rest of the essay writing process.

The best way to avoid getting into endless research loops is to be clear about how much research is actually required for the various points you make in your essay.

For critical points, you may need two or more citations; for less important ones, only one source.

Take a broad research approach first: find a readable general source on the topic first, perhaps use an AI summary tool to get an overview (see the “Tools” section later in this article), and search the bibliography for interesting specific sources to consult.

You can use the Internet to your advantage, but you should avoid citing it unless absolutely necessary. For academic papers, you are usually better served by citing academic books and papers that are referenced and perhaps even peer-reviewed. Google Scholar is a tool you can use to help find these sources.

3. Be Clear About the Topic of the Essay

Nothing undermines your efforts to focus on the topic more than writing a bunch of stuff only to find that you do not quite address the essay question!

The first thing you should do is take the time to digest FULLY the essay question or topic. What exactly does it mean? What angle is best suited to answer the question? Do you already have initial ideas about how to bring the topic to life? Think about all of this – and jot it down in bullet points – before you start researching, outlining, and writing.

For a complex sentence, it can be helpful to break down the sections in parentheses – and then represent them visually, e.g., as a drawing, mind map, Venn diagram, doodle… The point is that you have used an active technique to take the sentence apart and see how one part relates to the other. A kind of theme analysis.

It’s also important to keep your focus on the topic while researching and writing.

It’s amazing how quickly you can lose sight of the topic if you do not make sure it’s always at the forefront of your mind while writing.

The best way to keep the prompt in front of you is to keep it in front of you! I personally use a notebook, but you can also use a PostIt on your screen, a whiteboard, or other ways to have a simple statement and maybe 3-5 bullet points that you really want to address.

4. Be Clear About the Type of Essay You Want to Write

There are a number of different terms associated with an academic essay, and it’s a good idea to know them in order to write the best response.

- Expository Essay : requires the student to investigate an idea, evaluate evidence, expound on the idea and set forth an argument.

- Descriptive Essay : requires the student to describe something, in order to develop the student’s written accounts of particular experiences.

- Narrative Essay : requires the student to tell a story – whether anecdotal, personal, or experiential. Often requires creative writing.

- Timed Essay : require a writing sample within a limited time period.

- Persuasive Essay : requires the student to attempt to get the reader to agree with his or her point of view.

- Argumentative Essay : requires the student to establish a position on the essay topic.

5. Use Essay Structure to Help You Focus

Some back and forth examinations of arguments are useful in academic papers to show that you know the different sides of an argument. However, you usually choose one side or the other and support it with evidence and arguments.

If you structure your essay clearly and have a clear line of argument, you will work better overall and be able to concentrate more easily. This is where a clear and detailed outline and perhaps the use of mind mapping (as I do) can help.

As an example, take a look at the mind map and outline I created before writing this article.

The rough ideas were brainstormed before I did more detailed research and recorded the subtopics. The subtopics, by the way, are not strictly in the order I wrote them – but my first draft follows the order of the main topics as I laid them out in the mind map.

The trick to developing a good, clear structure is to first capture the main line in an essay outline, and then start fleshing out that outline.

6. Include Source Material Directly in Your Outline

Make sure you can easily move blocks around to get a clearer overall line through your essay.

A clear outline will also help you get your essay to the right length: Know how many words you need for each section, so you can make sure you do not write one section too much and another too little. This way, you’ll have a balanced essay that covers the different points well.

Think of quotes and citations as blocks that you can insert into the structure of your essay – set aside a source and incorporate it when it makes sense to you. Do not be afraid to swap them out if you find a better quote.

7. Some Additional Structure Tips for Essay Focus

Effective structuring will make the difference between a good essay and a great essay. It’ll help you deliver a successful essay that will win you points, and boost your confidence.

Write clearly and simply. Use an active tense. Use quality sources.

Look for surprises and really interesting points – chances are, if they surprise and stimulate you, they will do the same for others when you write about them!

Write the introductory paragraph and conclusion last!

Learn to Sift Through Ideas and Concepts Quickly

The following advice is very useful not only for essay writing but also for learning in general.

Chunking is a very valuable concept when it comes to gathering research material, sorting it into buckets, using it, and writing with it.

Think of it as large pieces and small pieces.

A whole section of an essay can be one big chunk into which you insert a whole series of smaller chunks.

In nonfiction writing, which includes essay writing, you can think of a small section as a specific idea expressed in a few sentences at most.

Breaking your ideas down into individual paragraphs (even if you group them later) can do wonders for gaining clarity of thought flow and connections.

Nonlinear Work

Working non-linearly is important: It’s a fact that we can not write down all of our ideas one by one in one sitting; at least, most of us do not.

If we have a system for putting ideas and evidence we encounter in the right place in our essay structure, we make our lives much easier.

Broadly speaking, it will help you to stick roughly to the following work structure:

1. Define the objective

2. Research

I say “roughly” because in practice there will be some overlap with other areas. But if you have a rough flow, you can better manage your overall process and energy.

As a general rule, it’s a good idea to write first drafts before tweaking grammar, spelling, structure, etc. The faster you can get an overview of your essay, the more motivated and original your work is likely to be.

Quick Questions to Keep Asking as You Write

In journalism, there are classic questions that are asked at every stage of research and writing: Who, What, When, How, and Why.

These questions are also very useful in essay writing because if you remember to ask (and answer) the “how” and the “why” at each stage of your essay, you will bring your essay to life.

These simple questions will help you focus on your argument and the evidence you have to support it.

Sometimes it can be easy to get lost in details and not see the forest for the trees.

A good solution to this is to step back from writing. Literally, stop for a few moments or minutes and remember K.I.S.S.: Keep It Super Simple (in the original it’s Keep It Simple Stupid – but I prefer my wording!).

Ask yourself: does the basic argument make sense? What is the main point you want to make? What is the main point that is missing? What is the most important thing the essay needs now to make it work better?

If you can not find the answer to any of these questions, ask yourself, “ How can I figure this out quickly? ” – let your mind find a solution.

If THAT does not work, you can try saying to yourself, “ If I had the answer to this question, what would it be? ” Basically, this is a psychological trick to enable yourself (and your mind) to find the right connections and name them.

Methods to Help You Focus Better When Studying and Writing Essays

There are a number of things you can do to help your overall concentration, which will also help you when writing your essays.

The Pomodoro Technique

You can use the ” Pomodoro Technique” to complete short, focused periods of work (sprints) each day that will help you get into the right frame of mind.

The basic idea is that you set a timer for 25 minutes and then work during that time without distractions. There are free and paid apps available on various mobile device stores to act as timers. During those 25 minutes, do not check email, Twitter, Facebook, or other websites.

Once the 25 minutes are up, take a 5-minute break. Repeat this process four times and then take a 15-minute break.

The reason is that it’s very hard to concentrate for more than 25 minutes – but after that, you have a nice break before starting a new 25-minute burst. You’ll find that you can get a lot more done in those 25-minute periods than you normally would. This gets you into the flow.

It also increases the total amount of work you get done over multiple sprints, making you much more productive. The short concentration phases make it easier for you to focus.

Although 25 minutes is the default setting, some people find that other time intervals work better for them; I personally tend to set mine to 45 minutes with a 5-minute break. Otherwise, it’s too short for me to be able to write sufficiently.

This technique is especially helpful for those of us who are easily distracted.

It’s not just about concentration. The Pomodoro technique has the added benefit of giving you a physical break from the screen and keyboard, allowing your muscles to rest and your body to stretch.

The v for Victory Technique

Posture is very important when learning and writing. Firstly for general health, and secondly for writing efficiency.

But that’s not all.

Did you know that you can literally program your mind for success by using a body language hack?

Try this: Stand up and stretch your arms above your head in a V shape. Hold them for a few seconds and breathe normally. Bonus points if you close your eyes and imagine success.

Now go back to doing what you were doing before. Do you feel better? Do you feel more positive?

This is a great technique for all kinds of situations.

Eliminate Auditory Distractions

As we learned above, any kind of distraction can seriously disrupt your work. It’s important to learn how to study peacefully.

Related: Where Can I Study Peacefully

Auditory distractions are especially troublesome because, while they may not be loud, they can be intrusive when you are trying to concentrate hard.

There are several obvious solutions: Close doors and windows, work in a room away from the source of the noise and ask the person making the noise to stop.

Less obvious, perhaps, is the use of noise-canceling headphones. Especially if you combine them with focused music or sound effects like forest rain or wind. I personally use YouTube Premium, which has several Focus playlists built-in. You can also try using the headphones without music, but with noise cancelation turned on.

Some people also report great success with binaural beats. If you search for “binaural beats focus,” you’ll find many options, including hour-long soundtracks.

These binaural tracks have the advantage of not only eliminating the source of the interference but also programming your brain’s waves to help you focus and write better.

Once you find a soundtrack or playlist that works for you, add it to your favorites and repeat if that helps.

Eliminate Visual Distractions

Ideally, remove all visual distractions from your workspace and leave only what is actually relevant to the work in front of you. In most cases, a tidy desk means a tidy mind.

In practice, it’s not always that simple. What you can do, however, is move the unimportant things to the edge of your desk and keep the area directly in front of you clear so you do not have a connection to the keyboard and screen.

It’s worth thinking about the overall placement and ergonomics of your workspace. For me, a good amount of natural daylight falling on the desk is helpful. I make sure it comes from the side and not the front.

I also use a small blue light on the desk when I am working, which helps me think positively and focus.

If you have the space, you might want to try putting your desk in the middle of the room. I first noticed this when I visited the home of Charles Darwin, the famous English naturalist. The first thing I noticed in his study was that the desk was right in the middle of the room. The same was true of Churchill’s desk in the attic of his country residence.

The point is that regardless of your particular circumstances, you can have a considerable amount of control over your visual environment. I would advise you to try different configurations and find one that works best for you. You may also find that changing the configuration of your room from time to time helps your motivation and concentration.

Screen Arrangement

I find that the arrangement of windows and applications on the screen I use for studying and writing is very important for efficiency when working and writing.

Right now, I have a 27-inch iMac right in front of me with two windows on it: On the left side of the screen is my mind map and outline, and on the right side is the writing surface where I am currently writing this article. To the right of the iMac is a laptop on which I have the mind map of this article at a glance.

Although I have experimented with 3 and even 4 screens, I personally find that two screens are sufficient for my particular needs. With more than 2 screens, I feel distracted. Of course, you should experiment and find out what works best for you.

I find that having the most important data immediately in view makes it all the better. I like to avoid switching back and forth between different applications and windows as much as possible.

I also find that having a clear visual memory system (a bit like muscle memory for the mind) helps a lot with writing. That’s why I always have the writing surface on the right side of the iMac screen, while the various research windows are always on the left.

Movement and Posture

What writers and students sometimes forget is the importance of posture and movement while working.

It is very important for motivation and health to move around during a workday, especially to protect your back.

I use a sit-stand desk for this purpose. This allows me to use different types of stands, chairs, and standing positions throughout the day to vary my posture and the angle at which my back moves throughout the day. This allows me to write for long periods of time without harming my body.

If you use the Pomodoro technique described above, you could use the 15-minute breaks for sprints to do a short exercise session. This could be a few short stretches combined with some push-ups, planks, sit-ups, or something similar.

Cold Therapy

It may sound like a terrible cliché, but the value of cold showers is incredible. I had the privilege of going to a British private school called Stonyhurst College when I was young. Stonyhurst has, I believe, the very first school swimming pool, which in my day was nicknamed The Plunge . When I was at Stonyhurst, the pool was surrounded by scary-looking showers and enormous baths with invariably cold water.

What I did not know then, but know now, is the value of cold water for overall mood, health, and learning performance. You may have heard of Wim Hof, the Iceman, who advocates cold therapy for health. If not, check out his videos on YouTube. They are incredible.

The way I practice it is not by jumping straight into the cold shower in the morning, although that’s probably the best method, but by washing with warm water for a few minutes and then turning the water to cold for 1 or 2 minutes. This always makes me feel more invigorated and better prepared for the morning’s work.

All I can say is: try it!

One technique that I think really contributes to efficiency in writing is dictation.

I personally use the app VoiceIn for this, but there’s also a free alternative from Google that I describe later in the “Tools” section of this article.

I either handwrite or type out the outline for the essays and articles I write and then I use a combination of typing and dictation when I write the article or essay.

I find that the decision whether I dictate or not is psychological. Sometimes I feel like dictating the article, sometimes I find it better to type it. Often I have found it helpful to start writing and then move to dictate when I am in the flow.

It’s a matter of trial and error, and I encourage you to keep a regular journal of what works and does not work for you personally to discover the best methods for you.

If you find that dictation is helpful, my advice is to get a good microphone on a stand that you can swivel in and out, and position the microphone very close to your mouth for much better results with the dictation software or app.

Finding Flow When Writing Essays

The ideal state when writing – including essay writing – is a flow state. This is the state where everything comes easily to you and you feel like you are doing your best while fully concentrating on what you are doing.

There are some things that can help you achieve this state:

Awareness of Resistance

Resistance is the enemy of flow. Resistance is anything that distracts you from your work and causes you to turn your attention away from what you are doing. The more you are aware of it, the more you can avoid it.

I think it’s important not to give up too soon when resistance comes in the form of procrastination or motivation. In the short term, it’s worse to give in to resistance and procrastinate, so you need to be prepared for it.

I find the easiest way to deal with resistance is to acknowledge it, then just ignore it and get on with the task.

Forming Habits

To make learning and writing a habit, which then makes everything easier, it’s good to understand how habits can be formed.

Habits are formed through three steps:

- the routine

The best way to form a habit is to choose a cue that is so repetitive that you can not help but do the routine every time you encounter the cue. The best cue is often a place, time, person, or feeling. For example, if I write in the same place at the same time in the morning and I feel a certain way, I can not help but do it, and so a habit loop is formed.

So if you want to make it a habit to write in the morning, you have to find a cue that you can not ignore. Perhaps the moment you finish breakfast.

However, make sure you have a reward at the end of the routine that you look forward to. This will make it easier for you to motivate yourself to do the routine, and encourage the formation of a new habit.

Learn Keyboard Shortcuts

One of the best favors you can do for yourself as a writer is to learn keyboard shortcuts.

If you do not know them yet, you should figure them out and use them. You’ll be amazed at how easy it all is.

Sleep, Diet and Hydration

This may sound familiar, but it’s worth reiterating how important it is to eat right, get enough sleep, and drink enough water.

When you are in optimal condition, you can make better use of the time you have.

A good tip is to darken the room where you sleep as much as possible. You will then have a deeper and more restful sleep.

Use Mental Management Techniques

Top athletes and their coaches use mental management and visualization techniques for a reason. It works.

If you spend a little time visualizing the feeling of success, what it will bring you and how you will get there, the actual process will be easier for you.

Instead of racking your brain over the steps, you’ll have them pre-programmed in your head – and you’ll just do them.

An important part of mental management is to NOT focus on failures, but instead focus on and celebrate when you do something well. This has the effect of anchoring in your mind the practices that lead to success, while not anchoring those that lead to failure.

Tools and Apps That Help With Essay Writing

When writing nonfiction, I use a number of apps on a daily basis that helps me immensely with my work.

This is a powerful research database app (unfortunately only for Mac) that uses AI to find useful snippets of information.

Related: Is DEVONThink Worth It

This is an amazing app that allows you to review and edit text very quickly and adapt to any tone of voice you want.

Related: What Is InstaText

This is the mind mapping and thought development app I use to brainstorm and outline my non-fiction writing. In fact, all my writing.

A very useful AI summary app that gives you a useful snapshot of a PDF file or book.

A reliable dictation extension that lets me dictate directly into my writing canvas. Or you can use the free Google Docs tool.

Something of a secret among writers. It is one of the best, if not the best AI GPT -3 app.

Related: What Is Sudowrite

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- Focus and Precision: How to Write Essays that Answer the Question

About the Author Stephanie Allen read Classics and English at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and is currently researching a PhD in Early Modern Academic Drama at the University of Fribourg.

We’ve all been there. You’ve handed in an essay and you think it’s pretty great: it shows off all your best ideas, and contains points you’re sure no one else will have thought of.

You’re not totally convinced that what you’ve written is relevant to the title you were given – but it’s inventive, original and good. In fact, it might be better than anything that would have responded to the question. But your essay isn’t met with the lavish praise you expected. When it’s tossed back onto your desk, there are huge chunks scored through with red pen, crawling with annotations like little red fire ants: ‘IRRELEVANT’; ‘A bit of a tangent!’; ‘???’; and, right next to your best, most impressive killer point: ‘Right… so?’. The grade your teacher has scrawled at the end is nowhere near what your essay deserves. In fact, it’s pretty average. And the comment at the bottom reads something like, ‘Some good ideas, but you didn’t answer the question!’.

If this has ever happened to you (and it has happened to me, a lot), you’ll know how deeply frustrating it is – and how unfair it can seem. This might just be me, but the exhausting process of researching, having ideas, planning, writing and re-reading makes me steadily more attached to the ideas I have, and the things I’ve managed to put on the page. Each time I scroll back through what I’ve written, or planned, so far, I become steadily more convinced of its brilliance. What started off as a scribbled note in the margin, something extra to think about or to pop in if it could be made to fit the argument, sometimes comes to be backbone of a whole essay – so, when a tutor tells me my inspired paragraph about Ted Hughes’s interpretation of mythology isn’t relevant to my essay on Keats, I fail to see why. Or even if I can see why, the thought of taking it out is wrenching. Who cares if it’s a bit off-topic? It should make my essay stand out, if anything! And an examiner would probably be happy not to read yet another answer that makes exactly the same points. If you recognise yourself in the above, there are two crucial things to realise. The first is that something has to change: because doing well in high school exam or coursework essays is almost totally dependent on being able to pin down and organise lots of ideas so that an examiner can see that they convincingly answer a question. And it’s a real shame to work hard on something, have good ideas, and not get the marks you deserve. Writing a top essay is a very particular and actually quite simple challenge. It’s not actually that important how original you are, how compelling your writing is, how many ideas you get down, or how beautifully you can express yourself (though of course, all these things do have their rightful place). What you’re doing, essentially, is using a limited amount of time and knowledge to really answer a question. It sounds obvious, but a good essay should have the title or question as its focus the whole way through . It should answer it ten times over – in every single paragraph, with every fact or figure. Treat your reader (whether it’s your class teacher or an external examiner) like a child who can’t do any interpretive work of their own; imagine yourself leading them through your essay by the hand, pointing out that you’ve answered the question here , and here , and here. Now, this is all very well, I imagine you objecting, and much easier said than done. But never fear! Structuring an essay that knocks a question on the head is something you can learn to do in a couple of easy steps. In the next few hundred words, I’m going to share with you what I’ve learned through endless, mindless crossings-out, rewordings, rewritings and rethinkings.

Top tips and golden rules

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told to ‘write the question at the top of every new page’- but for some reason, that trick simply doesn’t work for me. If it doesn’t work for you either, use this three-part process to allow the question to structure your essay:

1) Work out exactly what you’re being asked

It sounds really obvious, but lots of students have trouble answering questions because they don’t take time to figure out exactly what they’re expected to do – instead, they skim-read and then write the essay they want to write. Sussing out a question is a two-part process, and the first part is easy. It means looking at the directions the question provides as to what sort of essay you’re going to write. I call these ‘command phrases’ and will go into more detail about what they mean below. The second part involves identifying key words and phrases.

2) Be as explicit as possible

Use forceful, persuasive language to show how the points you’ve made do answer the question. My main focus so far has been on tangential or irrelevant material – but many students lose marks even though they make great points, because they don’t quite impress how relevant those points are. Again, I’ll talk about how you can do this below.

3) Be brutally honest with yourself about whether a point is relevant before you write it.

It doesn’t matter how impressive, original or interesting it is. It doesn’t matter if you’re panicking, and you can’t think of any points that do answer the question. If a point isn’t relevant, don’t bother with it. It’s a waste of time, and might actually work against you- if you put tangential material in an essay, your reader will struggle to follow the thread of your argument, and lose focus on your really good points.

Put it into action: Step One

Let’s imagine you’re writing an English essay about the role and importance of the three witches in Macbeth . You’re thinking about the different ways in which Shakespeare imagines and presents the witches, how they influence the action of the tragedy, and perhaps the extent to which we’re supposed to believe in them (stay with me – you don’t have to know a single thing about Shakespeare or Macbeth to understand this bit!). Now, you’ll probably have a few good ideas on this topic – and whatever essay you write, you’ll most likely use much of the same material. However, the detail of the phrasing of the question will significantly affect the way you write your essay. You would draw on similar material to address the following questions: Discuss Shakespeare’s representation of the three witches in Macbeth . How does Shakespeare figure the supernatural in Macbeth ? To what extent are the three witches responsible for Macbeth’s tragic downfall? Evaluate the importance of the three witches in bringing about Macbeth’s ruin. Are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? “Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, there is profound ambiguity about the actual significance and power of their malevolent intervention” (Stephen Greenblatt). Discuss. I’ve organised the examples into three groups, exemplifying the different types of questions you might have to answer in an exam. The first group are pretty open-ended: ‘discuss’- and ‘how’-questions leave you room to set the scope of the essay. You can decide what the focus should be. Beware, though – this doesn’t mean you don’t need a sturdy structure, or a clear argument, both of which should always be present in an essay. The second group are asking you to evaluate, constructing an argument that decides whether, and how far something is true. Good examples of hypotheses (which your essay would set out to prove) for these questions are:

- The witches are the most important cause of tragic action in Macbeth.

- The witches are partially, but not entirely responsible for Macbeth’s downfall, alongside Macbeth’s unbridled ambition, and that of his wife.

- We are not supposed to believe the witches: they are a product of Macbeth’s psyche, and his downfall is his own doing.

- The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is shaky – finally, their ambiguity is part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. (N.B. It’s fine to conclude that a question can’t be answered in black and white, certain terms – as long as you have a firm structure, and keep referring back to it throughout the essay).

The final question asks you to respond to a quotation. Students tend to find these sorts of questions the most difficult to answer, but once you’ve got the hang of them I think the title does most of the work for you – often implicitly providing you with a structure for your essay. The first step is breaking down the quotation into its constituent parts- the different things it says. I use brackets: ( Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, ) ( there is profound ambiguity ) about the ( actual significance ) ( and power ) of ( their malevolent intervention ) Examiners have a nasty habit of picking the most bewildering and terrifying-sounding quotations: but once you break them down, they’re often asking for something very simple. This quotation, for example, is asking exactly the same thing as the other questions. The trick here is making sure you respond to all the different parts. You want to make sure you discuss the following:

- Do you agree that the status of the witches’ ‘malevolent intervention’ is ambiguous?

- What is its significance?

- How powerful is it?

Step Two: Plan

Having worked out exactly what the question is asking, write out a plan (which should be very detailed in a coursework essay, but doesn’t have to be more than a few lines long in an exam context) of the material you’ll use in each paragraph. Make sure your plan contains a sentence at the end of each point about how that point will answer the question. A point from my plan for one of the topics above might look something like this:

To what extent are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? Hypothesis: The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is uncertain – finally, they’re part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. Para.1: Context At the time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth , there were many examples of people being burned or drowned as witches There were also people who claimed to be able to exorcise evil demons from people who were ‘possessed’. Catholic Christianity leaves much room for the supernatural to exist This suggests that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might, more readily than a modern one, have believed that witches were a real phenomenon and did exist.

My final sentence (highlighted in red) shows how the material discussed in the paragraph answers the question. Writing this out at the planning stage, in addition to clarifying your ideas, is a great test of whether a point is relevant: if you struggle to write the sentence, and make the connection to the question and larger argument, you might have gone off-topic.

Step Three: Paragraph beginnings and endings

The final step to making sure you pick up all the possible marks for ‘answering the question’ in an essay is ensuring that you make it explicit how your material does so. This bit relies upon getting the beginnings and endings of paragraphs just right. To reiterate what I said above, treat your reader like a child: tell them what you’re going to say; tell them how it answers the question; say it, and then tell them how you’ve answered the question. This need not feel clumsy, awkward or repetitive. The first sentence of each new paragraph or point should, without giving too much of your conclusion away, establish what you’re going to discuss, and how it answers the question. The opening sentence from the paragraph I planned above might go something like this:

Early modern political and religious contexts suggest that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might more readily have believed in witches than his modern readers.

The sentence establishes that I’m going to discuss Jacobean religion and witch-burnings, and also what I’m going to use those contexts to show. I’d then slot in all my facts and examples in the middle of the paragraph. The final sentence (or few sentences) should be strong and decisive, making a clear connection to the question you’ve been asked:

Contemporary suspicion that witches did exist, testified to by witch-hunts and exorcisms, is crucial to our understanding of the witches in Macbeth. To the early modern consciousness, witches were a distinctly real and dangerous possibility – and the witches in the play would have seemed all-the-more potent and terrifying as a result.

Step Four: Practice makes perfect

The best way to get really good at making sure you always ‘answer the question’ is to write essay plans rather than whole pieces. Set aside a few hours, choose a couple of essay questions from past papers, and for each:

- Write a hypothesis

- Write a rough plan of what each paragraph will contain

- Write out the first and last sentence of each paragraph

You can get your teacher, or a friend, to look through your plans and give you feedback . If you follow this advice, fingers crossed, next time you hand in an essay, it’ll be free from red-inked comments about irrelevance, and instead showered with praise for the precision with which you handled the topic, and how intently you focused on answering the question. It can seem depressing when your perfect question is just a minor tangent from the question you were actually asked, but trust me – high praise and good marks are all found in answering the question in front of you, not the one you would have liked to see. Teachers do choose the questions they set you with some care, after all; chances are the question you were set is the more illuminating and rewarding one as well.

Image credits: banner ; Keats ; Macbeth ; James I ; witches .

Comments are closed.

Writing Studio

Finding your focus in a writing project.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Finding Focus in a Writing Project Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Each writing project presents its own organizational challenges. Sometimes a writer can go on and on for pages with examples that prove a point…only she hasn’t quite figured out what that point is or noticed that all of her examples make the same basic illustration.

Other times a writer has great ideas, but can’t quite figure out how to begin writing (ever try explaining a five-hundred-page novel AND its relation to jazz in just under 7 pages?). For such assignments, it’s important to find your focus .

Having a focus will help make the purpose of your writing clear and allow readers to follow your reasoning with ease.

Defining Focus and How to Find It

Focus is the controlling idea, main point, or guiding principle of your writing. Strong writing has a very clear focus with secondary and related ideas positioned in order to supplement or support it.

Focus is not something a writer necessarily has at the beginning of the writing process, but something she “finds” and refines through exploration, drafting, and revision. If you find yourself making broad generalizations, rather than specific claims, you should check on your focus.

Questions To Help Bring Your Writing Into Focus

There is no exact formula for finding focus within your writing, but a few questions might help you zero in on your topic:

Question 1: What’s Most Important?

- If I have two divergent ideas, which one do I find more compelling? For analyses, do I need to explain the entire text being analyzed to make my point, or can it be made by using a few sections?

Question 2: What does the assignment ask me to do?

- What will my readers be looking for? Are they more concerned with my textual arguments, my contextual arguments, my explanation or summary of the issue, or my own view? Will they be looking for breadth, depth, or something else? Should I focus on one aspect of a particular issue rather than taking on the entire problem?

Question 3: What will my readers need to know more about?

- Have I provided complete and detailed explanations that will guide my readers forward and keep the argument on course?

Question 4: How well does my organization and structure serve my larger purpose?

- Can I identify a logical progression of ideas within the essay? Might there be a better order for the content / argument?

- Do I develop my points with minimal distraction? Or do I get muddled in tangential explanations and extraneous information?

Additional Techniques to Help You Find Focus

Technique 1: listing.

When you have several broad ideas to contend with, sometimes it’s best to just get them onto the page and out of your system. Listing allows you to categorize your ideas before committing to one. Here’s how it works:

- Start with the overarching idea. It could be about the main character, an important theme, a major scene, a particular argument, etc.

- Under that idea, begin listing whatever comes to mind in association with it. As you go, your list items may or may not become more specific.

- If your items are becoming more and more specific, you might have the beginnings of an outline. Step back and see which items might make a more manageable topic.

- If your items are not becoming more specific, try to circle and connect any related terms that you have listed. Do any patterns begin to emerge? If several words or concepts seem to be related, begin a new list with these as your starting point.

Technique 2: Outlining

Outlining is great when your topic is fairly well developed, but you aren’t quite sure how you want to tackle it. It allows you to roughly map the progress of your paper before committing to the actual writing. The trick, of course, is knowing when to follow it and when to modify it (know when to hold ‘em; know when to fold ‘em). For a standard 5-7 page paper, your outline should not exceed one page. If you find that your subheadings are growing exponentially, it’s a good bet that your main headings are too broad.

Technique 3: Draft Map

Draft maps are great when you’ve already written a first draft and want to examine the larger structure of your paper. They allow you to see which paragraphs support your thesis and which paragraphs do not.

- Identify your thesis statement or controlling ideas in the introduction. If you have more than one major claim, label each one (e.g. A, B, C or color code them).

- Identify the topic sentence or main idea of each of your paragraphs.

- Once you’ve identified the main idea of each paragraph, label them according to the main ideas outlined in your introduction. If a paragraph doesn’t fit, give it another label (i.e. if your paragraph doesn’t fit major claims A-C, give it the letter D).

- Tally your results: Is there a vast difference between your introduction and the ideas in your paragraphs? Is one idea treated significantly more than another? If so, perhaps you should consider refocusing on this idea rather than attempting to tackle the others or consider devoting more time to the other ideas.

Last revised: 07/2008 | Adapted for web delivery: 12/2021 In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Focus an Essay

Last Updated: October 11, 2022 References

This article was co-authored by Megan Morgan, PhD . Megan Morgan is a Graduate Program Academic Advisor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She earned her PhD in English from the University of Georgia in 2015. This article has been viewed 47,500 times.

Do your essays seem unfocused? Do you tend to ramble while writing? Stating a clear thesis and providing a well-structured argument will help you convey your points to the reader in a focused manner. Create an outline to bring different sections together into a cohesive, flowing piece of work. Be sure to read and revise your material as you write it. This will help you keep your work focused.

Essay Template and Sample Essays

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- If your essay is part of an exam, read the question carefully. Underline the action words like “explain,” “compare,” “analyze.” Be sure you understand how you are supposed to prove your answer.

- See if the essay prompt has multiple parts. For example, it could say, “First, discuss Mary’s emotions upon being rejected at the ball. Then compare her father’s behavior in this situation to his behavior towards Elizabeth’s engagement. Is he showing the same paternal instincts? How so?” For this question, you should answer the first part and then proceed to offer a comparison.

- You should not cite Wikipedia as a source. You can, however, use Wikipedia to find scientific sources for your topic. Look at the references section at the end of a Wikipedia article for links.

- Under each section, write your main arguments as bullet points.

- Under each argument, use secondary bullet points to write out your supporting points and create footnote or in-text citations.

- Include additional information that you think might be useful in an “Other” bullet point even if you don’t have a place for it. You might discard this information or find a use for it later.

- For example, if you must write a five paragraph essay about housing at the Sochi Olympics, you might organize your outline by having paragraphs that provide the following information: I. Introduction to Sochi Olympics and housing II. Discussion of housing financing III. Analysis of contractors, laborers, and their schedules for completion IV. Media reaction to unfinished housing V. Conclusion and overall assessment of housing at Sochi Olympics. Under each paragraph you would have additional sub-points.

Focusing Your Thesis Statement

- Your thesis statement is your opinion it is not a statement of fact. [4] X Research source For example, "Mr. Bennet's wife is Mrs. Bennet" is an indisputable fact and not a thesis statement. Your opinion might be, "By providing a time diary of Mr. Bennet's daily activities, I argue that he prefers to spend time with Elizabeth rather than Mrs. Bennet. Additional quotations work to prove that Mr. Bennet is intellectually attracted to more intelligent females. In this regard, he is a man living beyond his time."

- Your thesis statement is not a question. [5] X Research source You can ask questions in an introduction to pique the readers' interest but you must state directly what you want to prove. For example, you cannot ask, "Was the housing finished in time for the Sochi Olympics?" Most people know it wasn't. Instead, theorize or investigate why it was not finished on time and produce your unique opinion on the underlying reasons.

- Has someone proved the same thing previously or is your thought a well-established fact? If so, try to take a different angle on a topic. For example, instead of writing, "Pride & Prejudice is a beloved book especially for young women," ask yourself why? What is it about this particular book that has captured generations of young women's imaginations? Is it the characters? Do the strong female leads help girls of the past and today to identify with the story?

Writing the Introduction

- The length of your introduction depends on the size of your entire essay. For example, a five page essay should have a short introduction with only a few paragraphs. If you are doing a longer paper, however, your introduction could be a few pages. [9] X Research source

- It is often most effective to write your introduction after you have written the rest of your paper. While it is okay to write a draft of your introduction right away, you should edit your introduction later to reflect your paper's final appearance.

- Your explanation of the context should also be focused. For instance, in a shorter essay, you do not need to give an exhaustive explanation of 19th century gender roles. You can, however, provide a few sentences or paragraphs (depending on your essay size) to ground the reader. Specify the gender dynamics that impact the character you are examining. For example, in the context of Pride and Prejudice, discuss gender politics of the upper middle class as this is the class to which the Bennets belong. You might discuss women's dowries and their lack of occupations and thus need to marry. Choose the most relevant points that will help your reader understand your argument more.

Developing a Focused Argument

- For a five paragraph essay, each separate argument should have its own paragraph.

- Reread your supporting sentences aloud and ask yourself whether they relate to the topic sentence. If they do not, delete them. If they somewhat but not entirely relate, revise them.

- Check for the logical order of your supporting sentences. They should follow one another in a way that makes your argument clear. If you skip around in your explanation, even topically relevant sentences will not help the reader.

- Transitional words could be “furthermore,” “nevertheless,” “additionally,” or “in contrast.”

Writing the Conclusion

- Do not mention your future plans in a homework or exam essay. This step is appropriate for academic essays.

Finishing Your Essay

- If possible, wait a day or two before doing a thorough proofreading. You tend to catch more mistakes when you are less tired.

- Insert page numbers.

- Printing typed essays is another good way to find mistakes. Sometimes we see more mistakes on printed copies.

- Check for redundancies in language. Do you use the same verbs or transitional words all the time?

- It is helpful to collect your sources while you write. This way, if you have a “working bibliography,” it will only take a small time to proofread it before submission.

Expert Q&A

- Don't write your essay the night before it's due, as you will be stressed and have an immediate deadline, which never helps focus. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.clarion.edu/academics/academic-support/writing-center/Focusing-an-Essay-with-a-Thesis.pdf

- ↑ http://naropa.edu/documents/programs/jks/naropa-writing-center/thesis.pdf

- ↑ http://www.petco.com/Content/ArticleList/Article/30/17/433/Natural-Ferret-Behavior.aspx

- ↑ http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/beginning-academic-essay

- ↑ https://www.oxford-royale.co.uk/articles/how-to-answer-essay-questions.html

About this article

Reader Success Stories

Nathalie Mondsir

Mar 15, 2020

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Focus: Relate Sentences to a Paragraph’s Main Idea

Few things are more frustrating than reading a paragraph, reaching its end, and then wondering, “What the #@*% did I just read?”

There are a number of reasons why this might happen. One of them is a lack of focus in the writing. When a paragraph meanders from topic to topic, tries to fit in too many topics, or fails to clearly make the connection between its topic sentence and its supporting sentences, the writing isn’t focused. Unfocused writing often leaves readers puzzled and wondering what information they were supposed to take from it.

Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What does an unfocused paragraph look like?

Unfocused paragraphs come in a variety of forms. Some are longer than they should be and never reach a coherent point. Others are too short to make a strong statement. For some, it’s not the length that makes the paragraph unfocused but the content. The sentences might not flow together or support each other, making the text feel disjointed. Alternatively, the sentences might be so dense—packed with technical terms, multiple clauses, or nuanced concepts lacking explanation—that the reader can’t wrap their mind around them.

What constitutes too dense depends on your intended reader. Writing that uses lots of jargon might be perfectly fine if your reader has the expertise to understand that jargon, but it might be too dense for readers without that background.

Signs that may point to a lack of focus in writing include:

- Meandering sentences

- No topic sentence

Why is focused writing important?

Focused writing is important because it’s effective. By effective , we mean the writing clearly expresses its topic. When writing is focused, it’s easy for readers to understand.

On a small scale, focused writing means a paragraph’s topic sentence is clear and supported. On a larger scale, focused writing means each paragraph fits into the larger work coherently. After the introductory paragraph states the piece’s thesis, each following paragraph should support that thesis by expanding on it.

How to focus your writing

It might sound like a circular argument , but the way to focus your writing is by defining a clear focal point before you start writing .

Here’s what we mean by that: Before you begin to write, determine exactly what you’re going to write about. You might have a clear assignment to work with, or you may need to do some brainstorming to find the right topic for your work. Once you’ve determined your topic, craft your outline around it. Note each supporting paragraph’s topic, how it bolsters your writing’s main topic, and the information you’ll include in the paragraph. When it’s time to write your first draft, your outline will be like a road map to follow to keep your writing focused. Your finished outline should look like a skeleton for a finished paper , with each paragraph’s topic sentence listed to show how the paragraphs fit together and relate back to your thesis statement .

Use smooth transition sentences

Transition sentences are the sentences that bridge gaps between other sentences. In many cases, this bridge is what turns two seemingly unrelated sentences into a focused paragraph. Here’s an example with the transition sentence bolded:

That company routinely touts efficiency as one of its core brand values. However, the current requirement that all employees work on site is inefficient and slows down employee productivity. Changing to a primarily remote structure with flexible working hours would increase productivity by improving efficiency.

Transition sentences improve focus in writing by making the relationships between sentences clear. This makes it easier for the reader to understand the author’s position.

Fix run-on sentences

Run-on sentence isn’t just another way of saying long sentence. A run-on sentence is a sentence that:

- Contains two or more independent clauses

- Does not have grammatically correct punctuation or a conjunction connecting those clauses

Here is an example of a run-on sentence:

I took two literature courses last semester even though I already satisfied my humanities elective requirements because I like reading.

Here’s the non-run-on version of the same sentence:

I took two literature courses last semester, even though I already satisfied my humanities elective requirements, because I like reading.

An easy way to tell if you’ve got a run-on sentence is to read it and see if it can be separated into two or more distinct thoughts. If it can, see where it needs punctuation, a conjunction, or to be split into two sentences.

Eliminate unnecessary information

One of the easiest ways to correct a lack of focus in writing is to eliminate any tangents. A tangent is a thought that has little or nothing to do with the work’s main topic. In certain kinds of writing, like stream-of-consciousness writing, tangents are perfectly acceptable and even encouraged. But in any kind of focused work, like an essay, research paper, article, or even an email or another kind of business or academic communication, tangents only distract the reader.

As you proofread your work, remove any sentences that aren’t related to your main topic.

Examples of focused and unfocused paragraphs

The best days of my childhood were the days I spent up at my grandparents’ cabin on the lake. I learned how to swim. My grandfather took me to a small, shallow cove where I practiced all the basics. I was a confident swimmer.

The best days of my childhood were the days I spent up at my grandparents’ cabin on the lake. That’s where I learned how to swim. Every afternoon, my grandfather took me to a small, shallow cove where I practiced all the basics. By the time I was eight, I was a confident swimmer.

Next semester, I’m going to take Intro to Poetry Workshop. I wonder why I never took a poetry class before? I always liked writing fiction, and I even won an award for the best short story when I was in eleventh grade. Writing fiction is easy for me because I can easily think of story ideas. I can’t wait to take Intro to Poetry Workshop!

Next semester, I’m going to take Intro to Poetry Workshop. It will be a new experience for me; I’ve never taken a poetry workshop before. However, I’m not new to writing. I’ve always enjoyed writing fiction and found it comes very easily to me. Let’s see if the same is true for poetry—I’m looking forward to taking my first poetry course!

Keys to focused writing

Focused writing is all about staying on topic and removing unnecessary concepts and words.

- Define your topic and scope before you start writing.

- Choose topic sentences to set the stage for each paragraph.

- Use transition sentences to make a cohesive point.

- Fix run-on sentences.

- Eliminate unnecessary information.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

II. Getting Started

2.3 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso

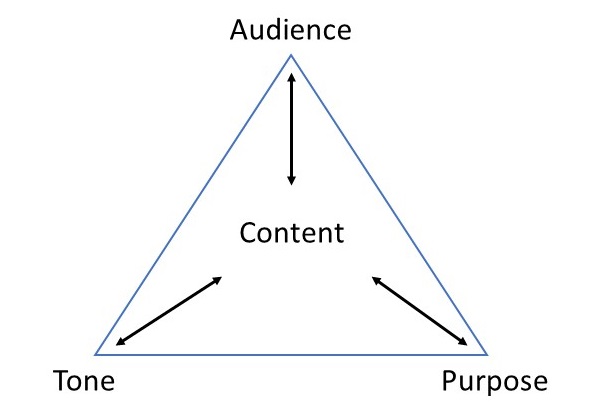

Now that you have determined the assignment parameters , it’s time to begin drafting. While doing so, it is important to remain focused on your topic and thesis in order to guide your reader through the essay. Imagine reading one long block of text with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. Keep in mind that three main elements shape the content of each essay (see Figure 2.3.1). [1]

- Purpose: The reason the writer composes the essay.

- Audience: The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

- Tone: The attitude the writer conveys about the essay’s subject.

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what each paragraph of the essay covers and how the paragraph supports the main point or thesis.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write it by, basically, answering the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing typically fulfill four main purposes:

- to classify

- to synthesize

- to evaluate

A classification shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials , using your own words; although shorter than the original piece of writing, a classification should still communicate all the key points and key support of the original document without quoting the original text. Keep in mind that classification moves beyond simple summary to be informative .

An analysis , on the other hand, separates complex materials into their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. In the sciences, for example, the analysis of simple table salt would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride: simple table salt.

In an academic analysis , instead of deconstructing compounds, the essay takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

The third type of writing— synthesis —combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Take, for example, the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document by considering the main points from one or more pieces of writing and linking the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Finally, an evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday life are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge such as a supervisor’s evaluation of an employee in a particular job. Academic evaluations, likewise, communicate your opinion and its justifications about a particular document or a topic of discussion. They are influenced by your reading of the document as well as your prior knowledge and experience with the topic or issue. Evaluations typically require more critical thinking and a combination of classifying , analysis , and synthesis skills.

You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure and, because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. Remember that the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of your paper, helping you make decisions about content and style .

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs that ask you to classify, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate. Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience —the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.