Can you pass the Citizenship Test? Visit this page to test your civics knowledge!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

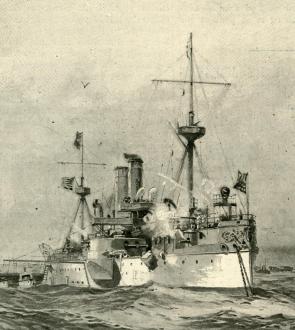

Remember the Maine, 1898

A spotlight on a primary source by harper's weekly.

The Harper’s Weekly article featured here represents a more balanced view of the event, noting:

the fate of the Maine will continue an unsolved mystery for historians to wrangle over. Meanwhile all that we shall positively know is that the explosion occurred forward, and hence that the seamen rather than the officers were the sufferers; that not more than 26 of the men remained uninjured; 57 being wounded and 246 killed, and that two of the 24 officers are certainly lost. If the disaster were the result of design and not of accident, it is considered probable that the blow would have been dealt the ship on the very spot where the explosion occurred—not because it would be more desirable to destroy the men than the officers, but because the magazine is always a preferable point of attack.

The cause of the Maine ’s sinking remains the subject of speculation. Suggestions have included an undetected fire in one of her coal bunkers, a naval mine, and sabotage to drive the US into a war with Spain.

A pdf of the article is available here .

Questions for discussion.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

Read the introduction and examine the four pages from Harper’s Weekly . Then apply your knowledge of American history to answer the following questions:

Note : It is beneficial for students to be familiar with the term “yellow press” and to have an understanding of the influence of Harper’s Weekly .

- Briefly explain what took place aboard the Maine .

- In the second paragraph of the Harper’s Weekly article, published a little over a week after the explosion aboard the Maine , it is noted that “the cause . . . is a mystery, the belief is growing that it was purely accidental.” The headline in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World on February 17, two days after the explosion, was: “MAINE EXPLOSION CAUSED BY BOMB OR TORPEDO?” The headline in William Randolph Heart’s New York Journal of the same day was: “DESTRUCTION OF THE WAR SHIP MAINE WAS THE WORK OF AN ENEMY.” How did the Harper’s Weekly article differ from the headlines in the “yellow press” newspapers controlled by Hearst and Pulitzer?

- Why is the Harper’s Weekly article considered a more balanced view of the destruction of the Maine ?

- What role did the tragedy aboard the Maine play in the decision of the United States to go to war with Spain?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Primary Sources: Major Events: USS Maine Explosion

- Irish Famine

- USS Maine Explosion

- Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

- The Titanic

- The Lusitania

- Mississippi Flood of 1927

- Great Depression (1930s)

- Hindenburgh

- Tacoma Narrows Bridge

- Pearl Harbor

- Bay of Pigs

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Munich Olympics Massacre

- Iran-Contra Affair

- September 11, 2001

Online Sources: USS Maine Explosion

- "Shameful Treachery": Hearst’s Journal Blames Spain more... less... "On February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the American battleship Maine, sinking the ship and killing 260 sailors. Americans responded with outrage, assuming that Spain, which controlled Cuba as a colony, had sunk the ship. Two months later, the slogan "Remember the Maine" carried the U.S. into war with Spain. In the midst of the hysteria, few Americans paid much attention to the report issued two weeks before the U.S. entry into the war by a Court of Inquiry appointed by President McKinley. The report stated that the committee could not definitively assign blame to Spain for the sinking of the Maine. Many historians have focused on the role of the “yellow press” (sensationalist newspapers so named because they waged cutthroat circulation battles over comic strips like the popular “Yellow Kid”) in stirring up sentiment that propelled the U.S. into its first imperialist war. This editorial in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, from February 17, 1898, pointedly blamed Spain for the sinking of the Maine, providing an example of how the “yellow press” covered the incident."

- "Suspended Judgment": A Times Editorial on the Maine Tragedy more... less... "On February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the American battleship Maine, anchored in Havana harbor, sinking the ship and killing 260 sailors. Americans responded with outrage, assuming that Spain, which controlled Cuba as a colony, had sunk the ship. By April, 1898, the slogan "Remember the Maine" carried the U.S. into war with Spain. In the midst of the hysteria, few Americans paid much attention to the report issued two weeks before the U.S. entry into the war by a Court of Inquiry appointed by President McKinley. The report stated that the committee could not definitively assign blame to Spain for the sinking of the Maine. Most historians have focused on the role of sensationalist newspapers in fomenting public support for U.S. entry into war with Spain, and perhaps even causing it by deliberately misleading the American public about the Maine explosion. But not all newspapers engaged in sensationalist coverage of the incident. This New York Times editorial, dated February 17, 1898, sounded a note of caution about blaming the Spanish government for the explosion."

- Better Late Than Never?: Rickover Clears Spain of the Maine Explosion more... less... "On February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the American battleship Maine, anchored in Havana Harbor, sinking the ship and killing 260 sailors. Americans responded with outrage, assuming that Spain, which controlled Cuba as a colony, had sunk the ship. Many newspapers presented Spanish culpability as fact, with headlines such as "The War Ship Maine was Split in Two by an Enemy’s Secret Infernal Machine.“ Two months later, the slogan ”Remember the Maine" carried the U.S. into war with Spain. In the midst of the hysteria, few Americans paid much attention to the report issued two weeks before the U.S. entry into the war by a Court of Inquiry appointed by President McKinley. The report stated that the committee could not definitively assign blame to Spain for the sinking of the Maine. In 1911, the Maine was raised in Havana harbor and a new board of inquiry again avoided a definite conclusion. In 1976, however, in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, Admiral Hyman Rickover conducted a new investigation. Rickover, something of a maverick in the Navy, came to the conclusion that the explosion was caused by spontaneous combustion in the ship’s coal bins, a problem that afflicted other ships of the period."

- The Disaster to the "Maine" more... less... Literary Digest February 26, 1898, page 241.

- The Maine and the World: Sailing into History more... less... "On February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the American battleship Maine, anchored in Havana harbor, sinking the ship and killing 260 sailors. Americans responded with outrage, assuming that Spain, which controlled Cuba as a colony, had sunk the ship. Two months later, the slogan "Remember the Maine" carried the U.S. into war with Spain. In the midst of the hysteria, few Americans paid much attention to the report issued two weeks before the U.S. entry into the war by a Court of Inquiry appointed by President McKinley. The report stated that the committee could not definitively assign blame to Spain for the sinking of the Maine. Publishers such as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer used their many newspapers to stir public opinion over the sinking of the Maine into a frenzy, hastenening U.S. entry into the conflict. This February 17, 1898, front page story from Pulitzer’s New York World suggested, on the basis of little evidence, the hand of the enemy in the destruction of the Maine. "

- Personal Narrative of the Maine more... less... Century Magazine, November 1898. Pages 74-96

- Secrets of the Serial Set: The Sinking of the U.S.S. Maine more... less... Provides links to U.S. Congressional Serial Set items regarding the sinking of the Maine.

- Sounding the Depths: The Times and the Sinking of the Maine more... less... "On February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the American battleship Maine, anchored in Havana Harbor, sinking the ship and killing 260 sailors. Americans responded with outrage, assuming that Spain, which controlled Cuba as a colony, had sunk the ship. A great deal of the American public’s outrage was generated by media coverage—newspapers and the emerging film industry—of the incident. The Biograph Company renamed its film The Battleships “Iowa” and “Massachusetts” the Battleships “Maine” and “Iowa,” and immediately released it to theaters. It played to cheering audiences. Newspapers, like those published by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, were even more influential in stirring American public opinion into a frenzy over the sinking of the Maine. In contrast to more sensational accounts of the Maine explosion, the staid New York Times cautiously reported on February 17, 1898, that there “was no evidence to prove or disprove treachery” as a factor in the sinking of the battleship. "

- Spanish American War - Primary Sources

- Topics in Chronicling America - The Sinking of the Maine

Book Sources: USS Maine Explosion

- A selection of books/e-books available in Trible Library.

- Click the title for location and availability information.

Search for More

- Suggested terms to look for include - diary, diaries, letters, papers, documents, documentary or correspondence.

- Combine these these terms with the event or person you are researching. (example: civil war diary)

- Also search by subject for specific people and events, then scan the titles for those keywords or others such as memoirs, autobiography, report, or personal narratives.

- << Previous: Irish Famine

- Next: Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2024 3:17 PM

- URL: https://cnu.libguides.com/primarymajorevents

- Engineering

- Mining Engineering

Centenary of the Destruction of USS Maine: A Technical and Historical Review

- Naval Engineers Journal 110(2):93 - 104

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

No full-text available

To read the full-text of this research, you can request a copy directly from the authors.

- Stephen L. Quackenbush

- Robert Erwin Johnson

- H. G. Rickover

- Wegner Dana M.

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Newspapers & Current Periodicals

Sinking of the Maine: Topics in Chronicling America

Introduction.

- Search Strategies & Selected Articles

Newspapers & Current Periodicals : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

Chat with a librarian , Monday through Friday, 12-2 pm Eastern Time (except Federal Holidays).

About Chronicling America

Chronicling America is a searchable digital collection of historic newspaper pages through 1963 sponsored jointly by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress.

Read more about it!

Follow @ChronAmLOC External and subscribe to email alerts and RSS feeds.

Also, see the Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries , a searchable index to newspapers published in the United States since 1690, which helps researchers identify what titles exist for a specific place and time, and how to access them.

Breaking residential windows and shaking the city of Havana to its core, a mysterious explosion sinks the USS Maine to the bottom of the Havana Harbor on the evening of February 15, 1898. The American "yellow press" blame Spain in banner headlines, outraging the public and inciting the rallying cry, "Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!" Over 260 crew members perish in this event, which was a contributing factor in the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. Read more about it!

The information in this guide focuses on primary source materials found in the digitized historic newspapers from the digital collection Chronicling America .

The timeline below highlights important dates related to this topic and a section of this guide provides some suggested search strategies for further research in the collection.

| January 24, 1898 | President William McKinley sends the battleship USS to Havana to protect U.S. interests in Cuba. |

|---|---|

| February 15, 1898 | The explodes in Havana Harbor, killing 266 men. |

| March 25, 1898 | An inquiry conducted by the U.S Navy concludes that the explosion was caused by the detonation of a mine under the ship. |

| April 19-20, 1898 | The U.S. Congress adopts a joint resolution for war with Spain and sends an ultimatum to the Spanish government. |

| April 21, 1898 | The U.S. orders a blockade of Cuba. |

| April 23, 1898 | Spain declares war on the United States, and the U.S. Congress responds on April 25 by issuing a formal declaration of war. |

- Next: Search Strategies & Selected Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 1, 2024 9:11 PM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-sinking-maine

Explosion of the USS Maine in 1898

After the mysterious explosion of the USS Maine in Havana, Cuba, the United States has decided to go to war with Spain. President William McKinley and his advisors now need to decide how to intervene against Spanish colonial rule in Cuba and what U.S. war aims should be.

Students will understand that war strategy stems in part from war aims.

Students will understand that intervention inevitably shapes future relations with a country

The Situation

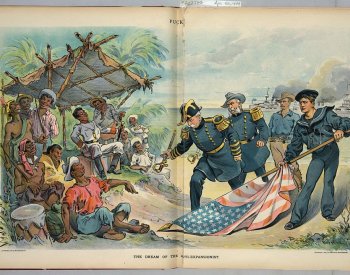

By the 1870s, tensions between the United States and Spain were growing. Once a vast empire, Spain had lost much of its overseas territory over the nineteenth century. The decline of the Spanish Empire left Cuba as one of its last remaining footholds in the Western Hemisphere. But Madrid’s grasp had begun to slip there as well. Starting in 1868, Cubans waged three successive liberation wars, culminating in the 1895 Cuban War of Independence. To quell the rebellion, Spanish forces acted harshly to suppress the revolutionary fervor on the island. The Spanish forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of Cuban civilians to concentration camps and practiced scorched-earth tactics to starve the rebels of supplies. More than two hundred thousand Cuban civilians died as a result of this policy. Back on the mainland, U.S. journalists were quick to bring the story of Cuban liberation to American readers. The American media stoked widespread sympathy for the Cuban cause and anger toward the Spanish empire. As the war dragged on, public outrage began to spur calls for U.S intervention on behalf of the Cubans.

Although public interest in Cuba was mainly humanitarian, the United States had economic interests in the island as well. In the wake of a major depression in 1873, the United States sought economic opportunities to aid recovery. Spain’s waning power in Cuba gave U.S. businesses a chance to invest in the island’s lucrative sugar and tobacco industries. Consequently, the U.S. and Cuban economies grew increasingly interconnected. By the 1890s, U.S. investments in Cuba amounted to roughly $50 million. At that time, nearly 95 percent of Cuban sugar exports went to the United States. Some Americans feared that continued Cuban imports would hurt certain domestic producers. However, most U.S. policymakers were more concerned that instability in Cuba would endanger U.S. investments and harm the overall U.S. economy. Intervention, therefore, offered an opportunity to protect U.S. economic interests. Moreover, the United States would also benefit from strengthened ties with a newly independent Cuba by aiding in the defeat of Spanish forces.

Policymakers also had strategic interests in Cuba. Specifically, the United States was eager to expand its sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere. Cuba presented a strategically valuable location for a naval outpost. An expanded U.S. naval presence in the Caribbean could protect regional trade. Moreover, a military presence in Cuba would aid U.S. efforts to develop a canal through Nicaragua or Panama to connect trade routes in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Spanish domination over the island, though, curtailed the United States’ ability to advance its political and strategic ties with Cuba. Some policymakers hoped that the removal of Spanish control in Cuba could enable a long-term U.S. presence in the region. Others, however, worried that intervention in Cuba was not worthwhile. In addition to the immense cost of a war, the United States had no way to ensure that intervention would lead to an independent Cuba friendly to U.S. interests. Policymakers, therefore, needed to consider how to prioritize various U.S. interests to determine how Washington’s relationship with a newly independent Havana would look.

Decision Point

Set in April 1898

The USS Maine —an American battleship sent to protect U.S. interests in Cuba—has exploded in Havana Harbor. The explosion killed 260 American sailors. Although the source of the explosion is unknown, the blast has sparked a media frenzy in the United States. Many in the American public are accusing Spain of orchestrating the incident and demand retribution. Diplomatic efforts with Spain following the explosion have failed, and public fury is growing. As a result, President William McKinley’s administration has concluded intervention in Cuba is now inevitable. Congress has approved the intervention, with an amendment forbidding any U.S. attempt to annex Cuba. With the United States on the path to war, President McKinley has convened his cabinet to determine what the United States’ aims should be and how best to pursue them. Policymakers will need to consider and prioritize the varying U.S. interests in Cuba and weigh the costs and benefits of pursuing those interests.

Cabinet members should consider any combination of the following policy options:

- Intervene for humanitarian purposes by aiding the Cuban resistance unconditionally to force Spanish withdrawal. This option most directly appeals to U.S. public sentiment and would be favorable to the Cuban resistance. However, this policy decision forgoes opportunities to secure advantageous economic arrangements. Humanitarian intervention also fails to advance strategic naval expansion in the region.

- Intervene for economic purposes by deploying forces to protect U.S. investments. This policy decision would also aid Cuban forces in the hope of cultivating a favorable postwar trade relationship. The goal of this intervention is to promote continued U.S. investment in Cuba. This option would protect U.S. economic interests in Cuba but could face opposition from competing U.S. industries. Additionally, the United States cannot guarantee that Cuban independence leaders will desire economic ties with the United States.

- Intervene for strategic purposes by strongly supporting Cuban forces. The purpose of this policy decision is to influence Cuban leaders to support the development of a U.S. naval base on the island. Control of a Cuban harbor would allow the United States to project power throughout the Caribbean. Moreover, a U.S. naval outpost would help facilitate the construction of a canal through Central America to expand trade. However, garnering the goodwill necessary to achieve this outcome is not guaranteed. This policy option could therefore require more robust involvement in the war than other options.

- Take limited action in retaliation for Spain’s suspected involvement in the USS Maine explosion by launching one or more isolated attacks on Spanish forces. This option would fail to aid Cuba or expand U.S. economic or strategic interests. However, this policy option would signal U.S. focus on preserving domestic interests and appease public desire for retribution against Spain.

Additional Resources

USS Maine – ‘Remember The Maine!’

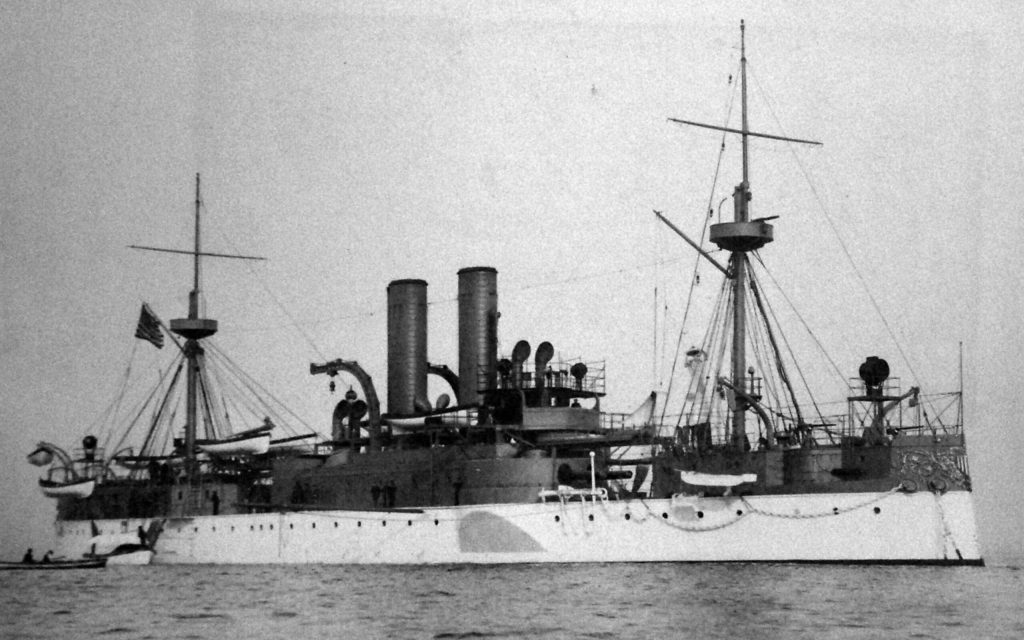

The USS Maine, launched in 1889, was a United States Navy battleship whose tragic explosion in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, played a pivotal role in precipitating the Spanish-American War.

The ship’s sinking, resulting in significant loss of life, became a rallying point for U.S. intervention in Cuba, underscored by the iconic slogan, “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!”

The Explosion On USS Maine

The catalyst for war, the legacy of uss maine.

In the late 19th century, the world’s major powers were engaged in rapid naval armament and modernization. The United States, seeking to assert its maritime strength and global presence, initiated a program to build a more powerful and technologically advanced navy. This period marked a transition from wooden sailing ships to steel-hulled, steam-powered vessels, a change that fundamentally altered naval warfare.

The USS Maine was conceptualized as part of this modernization effort. It was intended to be a formidable presence on the high seas, capable of both offensive and defensive roles. This was a time when naval power was increasingly seen as a symbol of national strength, and the Maine was to be a testament to America’s growing industrial and military capabilities.

Read More Truk Lagoon – The Biggest Graveyard Of Ships In The World

The design of the USS Maine was a product of its time, showcasing both innovation and the limitations of contemporary naval architecture. As a pre-dreadnought battleship, it represented a crucial phase in the evolution of warship design. The Maine combined aspects of traditional ship design with new technological advancements.

The Maine was equipped with a main battery of large-caliber guns, typical of battleships of the era. These guns were designed to deliver powerful broadsides, a naval tactic where all guns on one side of a ship are fired simultaneously. In addition to its main artillery, the ship also carried a number of secondary and smaller caliber guns, which were intended for shorter-range engagements.

The hull of the Maine was reinforced with armor plating, a relatively new feature in ship design at that time. This armor was intended to provide protection against enemy fire, particularly from the increasingly powerful artillery being mounted on other naval vessels.

The propulsion system of the USS Maine was a significant departure from older sailing ships. It was powered by a combination of steam and other emerging technologies, which provided greater speed and maneuverability. This shift to steam power was part of a broader trend in naval warfare.

The Maine was also notable for its use of electricity, a novel feature at the time. Electric power was used for a variety of onboard systems, including lighting and communications.

The USS Maine was constructed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, New York. The construction process involved significant challenges, as it required new techniques and materials to accommodate the ship’s advanced design.

The Maine was launched in 1889, amid great fanfare and public interest. Its commissioning was a proud moment for the U.S. Navy.

On the night of February 15, 1898, the USS Maine, anchored in Havana Harbor, Cuba, suddenly exploded. The ship was on a friendly visit, ostensibly showing American support for the Cuban people during their struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule. The presence of the Maine in Cuban waters was also a clear signal of American interest in the political situation in the region.

Read More Peter Tordenskjold – The Captain That Asked To Borrow Ammo From His Enemy

The explosion was catastrophic. A significant portion of the forward section of the ship was obliterated. Witnesses reported a massive blast followed by a series of smaller explosions. The destruction was so severe that it led to the rapid sinking of the vessel.

The explosion claimed the lives of 266 officers and sailors, over two-thirds of the ship’s crew. This tragic loss of life not only devastated the families of the deceased but also sent shockwaves across the United States.

Immediate efforts were undertaken to rescue survivors and recover the bodies of the deceased. The U.S. Navy, local Cuban authorities, and other ships in the harbor participated in these efforts. The recovery operation was grim and challenging, given the extent of the destruction.

An official U.S. Navy inquiry was swiftly launched to determine the cause of the explosion. The Sampson Board, named after its head, Captain William T. Sampson, concluded that the explosion was caused by an external mine, which in turn ignited the ship’s forward magazines.

The conclusion that a mine caused the explosion fueled speculation and accusations, particularly towards Spain, which controlled Cuba at the time. The lack of definitive evidence and the charged political environment of the era led to widespread rumors and theories about the incident.

Read More Germany Built A Weather Station In Canada During WWII

The American press, particularly the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, sensationalized the event, often engaging in what is now known as “yellow journalism.” They portrayed the explosion as an act of Spanish aggression, inflaming public opinion and stirring calls for revenge.

The rallying cry “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!” emerged, reflecting the public’s anger and desire for retribution. This sentiment played a critical role in shaping American attitudes toward Spain and the situation in Cuba.

The sinking of the USS Maine in February 1898 acted as a significant catalyst in the mounting tensions between the United States and Spain. While the U.S. had other interests and concerns in the region, the dramatic loss of the Maine and its crew provided a tangible focus for American indignation and calls for action against Spain.

The explosion galvanized public opinion in the United States. Amidst a wave of nationalistic fervor and heightened by sensationalist newspaper reports, the American public began to clamor for a response against Spain. This public pressure played a crucial role in shaping the decisions of U.S. political leaders, including President William McKinley, who were initially hesitant to engage in war.

The role of the “yellow press,” particularly newspapers run by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, in the lead-up to the Spanish-American War was significant. These publications used the Maine incident to stoke public anger and advocate for war, often employing sensationalist and sometimes unverified reporting to sway public opinion.

The phrase “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain!” became a rallying cry for those advocating for American intervention. This slogan, widely circulated by newspapers and public speeches, encapsulated the emotional response to the Maine tragedy and solidified the incident as a casus belli in the minds of many Americans.

The Maine incident exacerbated already strained relations between the United States and Spain. While Spain denied any involvement in the explosion and even proposed an international inquiry into the incident, the prevailing mood in the U.S. was increasingly bellicose.

Read More Three U-Boats Missing Until 1985, Now Under a Car Park

The cumulative effect of the Maine explosion, along with America’s long-standing interest in Cuba led to the U.S. Congress declaring war on Spain on April 25, 1898. This declaration marked the beginning of the Spanish-American War, a conflict that would have significant implications for both nations and signal the emergence of the United States as a colonial power.

The sinking of the USS Maine marked a critical juncture in American history, particularly in the context of U.S. foreign policy. The event and its aftermath catalyzed a shift from a more isolationist stance to an assertive, interventionist approach. This change was emblematic of America’s burgeoning role as a global power at the turn of the 20th century.

The Spanish-American War, precipitated in part by the Maine incident, resulted in the United States acquiring overseas territories. This expansion marked the beginning of an era of American imperialism, a significant departure from the country’s earlier reluctance to engage in colonial ventures.

Memorials dedicated to the USS Maine and its lost crew members have been erected in various locations, including Arlington National Cemetery and Havana. These memorials serve as poignant reminders of the tragedy and its impact on American history.

The phrase “Remember the Maine” has endured in American cultural memory, symbolizing not just a rallying cry for war but also a reminder of the costs of conflict and the complexities of historical events.

Read More The Halifax Explosion

Over the years, the USS Maine has continued to attract interest from historians, researchers, and the public. Its story is revisited in various forms, including books, documentaries, and academic studies.

With advancements in technology and historical research methods, the cause of the Maine’s explosion continues to be a subject of speculation and study. These reassessments contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the event and its significance in the broader tapestry of history.

You may also like

Nelson and HMS Victory: The Legacy of a Hero and his Ship

New Interpretations of How the USS Maine Was Lost

Cite this chapter.

- Dana Wegner

Part of the book series: The Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute Series on Diplomatic and Economic History ((WOOROO))

64 Accesses

2 Citations

T he U.S. battleship Maine exploded in H avana H arbor at 9:40 p . m . on February 15, 1898. Within six days of the explosion a U.S. naval court of inquiry was convened to establish the cause of the explosion. One month later the court found that the ship, in all probability, was destroyed by an underwater mine that ignited parts of the forward magazines. The act had been done by unknown persons. Relations between the United States and Spain were tense during a period of Cuban colonial rebellion and Spanish repression. On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spain and “Remember the Maine ” became a familiar call to arms. Between 1910 and 1912 the wreck of the Maine was raised from Havana Harbor and the Navy briefly reexamined the case, essentially rubber-stamping the 1898 findings.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Crimean War’s First Shots in the Baltic, 1854

Disaster Ahead

A Course of National Infamy: May to August 1915

Allen, Thomas B. “Remember the Maine?” National Geographic 193, no. 2 (Feb 1998): 92–111.

Google Scholar

Allen, Thomas B. “A Special Report: What Really Sank the Maine?” Naval History 12, no. 2 (Mar/Apr 1998): 30–39.

Arnot, Laurence A., comp. “USS Maine (1887–1898) in Contemporary Plans, Descriptions, and Photographs.” Nautical Research Journal 36, no. 3 (Sep 1991): 131–47.

Blandin, John J. “Don’t Publish This Letter.” Naval History 12, no. 4 (Jul/Aug 1998): 30.

Blow, Michael. A Ship to Remember (New York: William Morrow, 1992).

Crawford, Michael J., Mark L. Hayes, and Michael D. Sessions. The Spanish-American War: Historical Overview and Selected Bibliography (Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1998).

Hansen, IbS. “In Contact.” Naval History 12, no. 3 (May/Jun 1998): 8–16.

Hansen, Ib S. and Dana M. Wegner. “Centenary of the Destruction of the Maine : A Technical and Historical Review.” Naval Engineers Journal 110, no. 2 (Mar 1998): 93–104.

Article Google Scholar

Haydock, Michael D. “This Means War.” American History 32, no. 1 (Feb 1998): 42–63.

Miller, Tom. “Remember the Maine,” Smithsonian 28, no. 11 (Feb 1998): 24.

Price, Robert S. “Forum.” National Geographic 193, no. 6 (Jun 1998): 30.

Remesal, Augustin. El Enigma del Maine (Barcelona: Plaza & Janes Editores, 1998).

Rickover, H. G. How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1995). Includes new information not found in the original 1976 edition published by the Naval Historical Center. Also, Como Fue Hundido ElAlcorazado Maine (Madrid: Editorial Naval, 1985). Spanish-language translation of the 1976 edition.

Smith, Roy C. III. “In Contact.” Naval History 12, no. 4 (Jul/Aug 1998): 30.

Wegner, Dana. “In Contact.” Naval History $112, no. 4 (Jul/Aug 1998): 15–17.

Allen, Thomas B. “Raising Maine and the Last Farewell.” Nautical Research Journal . 42, no. 4 (Dec 1997): 220–36.

Allen, Thomas B. Review of Remembering the Maine, by Peggy and Harold Samuels. Naval Engineers Journal 107, no. 5 (Nov 1995): 98–102.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 2001 Edward J. Marolda

About this chapter

Wegner, D. (2001). New Interpretations of How the USS Maine Was Lost. In: Marolda, E.J. (eds) Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy, and the Spanish-American War. The Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute Series on Diplomatic and Economic History. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-05501-9_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-05501-9_2

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-63344-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-05501-9

eBook Packages : Palgrave History Collection History (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A Special Report: What Really Sank the Maine?

After a period of uneasy peace, Cuban rebels in 1895 renewed their struggle against the Spanish rulers of the island. To quell this latest insurrection, Spain sent General Valeriano Weyler, who forced thousands of Cubans into concentration camps. Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal thundered with demands for U.S. intervention to aid the Cuban guerrillas. The sensationalist newspapers dubbed Weyler "the Butcher" and published stories—some true, some not—about his atrocities against Cubans. Spain, reacting to U.S. loathing of Weyler, removed him, temporarily easing tension between the two nations. But in January 1898, anti-American rioting broke out, and U.S. Consul Fitzhugh Lee (nephew of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and himself a Major General in the Confederate Army) urged official Washington to protect the lives of U.S. citizens on the volatile island. President William McKinley ordered the Maine to Cuba. On 25 January 1898, the battleship steamed into Havana Harbor. McKinley, trying to still the war drums, wanted the Maine to show the flag, prove that U.S. warships had the right to enter Havana, and then get out. On 15 February the Maine was to head for New Orleans in time for Mardi Gras. By then, McKinley hoped, anti-Spain fervor should have died down. But at 2140 on the night of 15 February, a massive explosion tore through the ship, killing 250 men and two officers. (Mortal injuries raised the final toll to 266.) A Court of Inquiry questioned survivors—including commanding officer Captain Charles D. Sigsbee—and interpreted the reports of divers. The theory that a mine had destroyed the ship stemmed primarily from eyewitness testimony. The report of diver W. H. F. Schluter was particularly significant. He said he could see green paint on a bottom plate that was "all torn ragged and it looked to be inward." Bottom plates on the outside were painted with antifouling green paint. So this produced the image of a plate being blasted from the outside and turned inward. "You are sure they were not bent out?" the court asked Schluter. "Yes, sir; I am sure," he replied. "And the green paint you saw was on the part bent inward?" "The green paint was on the part bent inboard. . . . My opinion is, I believe that she was blown up from the outside and in, because there was no explosion from the inside [that] could make a hole like that, from the way them plates stood around in different directions." The Court concluded that the extensive damage "could have been produced only by the explosion of a mine." But it was "unable to obtain evidence fixing the responsibility . . . upon any person or persons." After the court's finding was revealed in March, McKinley no longer could ignore the call for war. "Remember the Maine and the hell with Spain" became a rallying cry. But was it a mine? The question lingered until 1911, after the U.S. Corps of Engineers, in an unprecedented feat, built a cofferdam around the ship, pumped out the water, and exposed the wreckage. A Board of Inquiry based much of its analysis on photographs of physical evidence that the previous investigation had sensed but not seen: bottom plates that were bent inward, presumably by an external force, such as a mine. The board focused on a section of outside plating that "was displaced inward and aft and crumpled in numerous folds." Although the 1911 report placed the location of the explosion farther aft, the 1911 inquiry's conclusion agreed with that of 1898: "The board believes that the condition of the wreckage . . . can be accounted for by the action of gases of low explosives such as the black and brown powders with which the forward magazine were stored. The protective deck and hull of the ship formed a closed chamber in which the gases were generated and partially expanded before rupture." The question disappeared. Historians writing after 1911 took for granted that someone—Spanish sympathizers, perhaps, or disgruntled guerrillas hoping to goad the United States into war—had set a mine that blew up the Maine. After reading a newspaper story in 1974 about the sinking of the Maine, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover decided to reexamine the issue. He recruited historians, archivists, and two Navy experts on ship design: Robert S. Price, a research physicist at the Naval Surface Weapons Center at White Oak, Maryland, and Ib S. Hansen, assistant for design applications in the Structures Department at the David W. Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center at Cabin John, Maryland. Among Price's Navy projects had been an analysis of the wreckage of the nuclear-propelled submarine Scorpion (SSN-589), which was lost in May 1968. The Hansen-Price analysis, as Rickover called it, was the heart of a short book published in 1976. The 23-page analysis reached this conclusion: "We found no technical evidence . . . that an external explosion initiated the destruction of the Maine. The available evidence is consistent with an internal explosion alone. We therefore conclude that an internal source was the cause of the explosion. The most likely source was heat from a fire in a coal bunker adjacent to the 6-inch reserve magazine. However, since there is no way of proving this, other internal causes cannot be eliminated as possibilities." Again, historians rallied around the Rickover solution, and after 1976 most discussions of the Spanish-American War concluded that there was no mine. As the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Maine approached, David W. Wooddell, senior researcher on the editorial planning council of National Geographic magazine, suggested that the magazine commission an analysis of the disaster based on computer modeling not available to Rickover and his team. Advanced Marine Enterprises (AME), a marine engineering firm often used by the U.S. Navy, accepted the mission. The AME analysis, which was announced in the February 1998 issue of National Geographic, examined both the mine and the coal bunker theories. The report declared that "it appears more probable, than was previously concluded, that a mine caused the inward bent bottom structure and detonation of the magazines." Some experts, including Rickover's researcher Hansen and respected analysts in AME itself, do not accept the conclusions of the AME report. Following are excerpts, published in cooperation with National Geographic, to give readers a chance to judge for themselves.

1. Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen, Rickover: Controversy and Genius (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982).

2. H. G. Rickover, How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1976). A revised edition was published in 1995 by the Naval Institute Press, with a new foreword by Francis Duncan, Dana M. Wegner, Ib S. Hansen, and Robert S. Price. A new appendix gives details of World War II ship damage not available in 1976. The authors use this data to bolster their findings that a mine did not destroy the Maine.

3. Handbook 1081, Primer On Spontaneous Heating And Pyrophoricity (U.S. Department Of Energy (DOE).

4. Environment Safety and Health Bulletin EH-93 -4, The Fire Below: Spontaneous Combustion in Coal; U.S. Department Of Energy.

5. Handbook 1081 (U.S. DOE).

6. William H. Garzke Jr., David K. Brown, Arthur D. Sandiford, John Woodward, and Peter K. Hsu, "The Titanic And Lusitania: Final Forensic Analysis," Marine Technology, October 1996.

7. Fire Protection Handbook, 16th edition (National Fire Protection Association [NFPA]).

9. Handbook 1081 (U.S. DOE).

10. Fire Protection Handbook (NFPA).

11. The Report of the Naval Court of Inquiry Upon the Destruction of the United States Battleship Maine in Havana Harbor February 15, 1898, Together With Testimony Taken Before the Court (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1898-Library of Congress).

12. The Report of the Naval Court of Inquiry, 1898.

13. Report on the Wreck of the Maine, 14 December 1911.

14. All figures in table from Cooper and Kurowski, Introduction to the Technology of Explosives (VCH Publishers, 1996) or Explosives and Demolitions (Department of the Army, FM 5-25, Feb. 1971).

15. T. L. Davis, The Chemistry of Powder and Explosives (New York: J. Wiley & Sons, 1941).

16. Cooper and Kurowski, Introduction to the Technology of Explosives.

17. Sax and Lewis, Hazardous Chemicals Desk Reference (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987).

18. N. Cary, Head, Curator Branch, Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

19. S. Hering, M. Mat. Sci., B. Met. E., Advanced Marine Enterprises, Arlington, Virginia.

20. D. A. Fisher, The Epic of Steel (New York: Harper & Row, 1963) Chapter 18.

21. D. Wegner, Curator of Models, Carderock Division, Naval Surface Warfare Center, Bethesda, Maryland.

22. H. Keith, Ph.D., Forensic Metallurgist, Marathon, Florida; T. Foecke, Materials Scientist, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland.

23. The Report of the Naval Court of Inquiry; Rickover.

24. Robert H. Cole, Underwater Explosions, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1948).

25. Rickover analysis.

Thomas B. Allen

Mr. Allen is a prolific writer and military historian and is the author of "Remember the Maine?" which appears in the February 1998 issue of National Geographic magazine. Mr. Allen and the U.S. Naval Institute gratefully acknowledge National Geographic—particularly the magazine's Senior Researcher, David W. Wooddell—for allowing Mr. Allen to adapt its Maine report for publication in Naval History.

View the discussion thread.

Receive the Newsletter

Sign up to get updates about new releases and event invitations.

You've read 1 out of 5 free articles of Naval History this month.

Non-subscribers can read five free Naval History articles per month. Subscribe now and never hit a limit.

Register today!

Alternative versions of assessment, opposition to the philippine-american war, the kkk in the 1870s, clay's american system, the rockefeller foundation, the role of women, mexican immigration in the 1920s, haitian revolution, united farm workers, women's liberation, explosion of the uss maine.

Like Opposition to the Philippine-American War , this assessment gauges students’ ability to reason about how evidence supports a historical argument. Students must explain how a report by the Naval Court of Inquiry and a San Francisco newspaper article both support the conclusion that confusion surrounded the sinking of the USS Maine at the time.

Download Materials

Historical Research and Study: The USS Maine

Historical Research and Study: The USS Maine Quiz Active 2 5 6 7 Jo TIME REMAINING 46:49 Pilar is doing research on the USS Maine for a paper. What would be the best choice as a source for information? a history textbook with a chapter on life in the late 1800s a historical novel about the sinking of the USS Maine a design book with a chapter devoted to shipbuilding a nonfiction book written by an expert on the USS Maine

Snowysound66 is waiting for your help., expert-verified answer.

- 116 answers

- 3.5K people helped

Final answer:

The best source for information on the USS Maine would be a nonfiction book written by an expert on the subject.

Explanation:

The best choice as a source for information on the USS Maine would be a nonfiction book written by an expert on the USS Maine . This type of book would provide accurate and in-depth information about the history, events, and significance of the USS Maine. A history textbook with a chapter on life in the late 1800s could also be a good source, but it may not provide as detailed information specifically about the USS Maine. A historical novel about the sinking of the USS Maine would be a fictional account and not suitable as a reliable source for historical research. A design book with a chapter devoted to shipbuilding would offer insights into shipbuilding techniques but might not cover the historical context and events surrounding the USS Maine.

Learn more about Researching the USS Maine here:

brainly.com/question/10061351

Still have questions?

Get more answers for free, you might be interested in, new questions in history.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Pilar is doing research on the USS Maine for a paper. What would be the best choice as a source for information? D. a nonfiction book written by an expert on the USS Maine. An investigation of the Maine sinking was held in 1911 because. C. many people did not trust the first investigation. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like An investigation of the Maine sinking was held in 1911 because, Eyewitnesses often have different accounts of events, so historians must, The five questions historians ask to investigate the past are,_________ what, where, when, and why. and more.

a nonfiction book written by an expert on the USS Maine. The National Geographic findings on the sinking of the Maine were mostly based on. advanced computer modeling. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like An investigation of the Maine sinking was held in 1911 because, Eyewitnesses often have different accounts of ...

Remember the Maine, 1898 | | On February 15, 1898, the battleship USS Maine exploded in Havana's harbor in Cuba, killing nearly two-thirds of her crew. The tragedy occurred after years of escalating tensions between the United States and Spain, and the "yellow press" and public opinion were quick to blame Spain. While the sinking of the Maine was not a direct cause of the Spanish ...

CUBA - CIRCA 1897: The sinking of the Maine on February 15, 1898 precipitated the Spanish-American War and also popularized the phrase Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain! In subsequent years, the cause of the sinking of the Maine became the subject of much speculation. The cause of the explosion that sank the ship remains an unsolved mystery.

Abstract. The USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898 with the loss of 266 lives. Its loss sparked the battle cry "Remember the Maine," it became one of the causes of the ...

President William McKinley sends the battleship USS Maine to Havana to protect U.S. interests in Cuba. February 15, 1898: The Maine explodes in Havana Harbor, killing 266 men. March 25, 1898: An inquiry conducted by the U.S Navy concludes that the explosion was caused by the detonation of a mine under the ship. April 19-20, 1898

Set in April 1898. The USS Maine—an American battleship sent to protect U.S. interests in Cuba—has exploded in Havana Harbor.The explosion killed 260 American sailors. Although the source of the explosion is unknown, the blast has sparked a media frenzy in the United States.

The USS Maine, launched in 1889, was a United States Navy battleship whose tragic explosion in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, played a pivotal role ... With advancements in technology and historical research methods, the cause of the Maine's explosion continues to be a subject of speculation and study. These reassessments contribute to a ...

historian's office of the Energy Research and Development Agency, bran dishing the newspaper. At that time I was a historical researcher on Admiral Rickover's staff reporting to Dr. Francis Duncan, an Atomic Energy Com mission historian. Our assignment was to prepare a study of the naval nu clear propulsion program.

A new study commissioned by National Geographic magazine—excerpted here for the first time—advances conclusions that could help explain the explosion that sank the battleship in Havana Harbor 100 years ago. ... archivists, and two Navy experts on ship design: Robert S. Price, a research physicist at the Naval Surface Weapons Center at White ...

The USS Maine anchored in the Havana harbor on January 25, 1898. As security precautions, two of the USS Maine's boilers remained on, and ammunition was stored adjacent to its guns for quick access. For almost three weeks, the battleship and its 355-member crew remained without incident. Then, unexpectedly on the evening of February 15, 1898, an

ABSTRACT The USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898 with the loss of 266 lives. ... was member of the origial team Admiral Rickover assembled to study the Maine. He holds on M.S. degree in Civil and Structural Engineering from the Technical University of Denmark. ... Mr. Wegner began his government career in 1974 as a ...

Tim Yoder. 4.8. (43) $3.00. PDF. The U.S.S. Maine was a battleship that was sent to Havana Harbor in January, 1898, to protect American lives and property during the revolt of Cubans against the Spanish government. At 9:40 P.M. on February 15, 1898, an explosion ripped through the ship, killing 266 sailors.

Explosion of the USS Maine. To successfully complete this assessment, students must examine the source information and consider the context in which these documents were created. To answer Question 1, students must conclude that a Navy inquiry into the explosion of the Maine provides evidence that there was confusion over the explosion of the ...

a nonfiction book written by an expert on the USS Maine. Which can help historians decide if a source is reliable? determining the author's point of view on the subject. National Geographic commissioned a study of the Maine sinking in. 1998. The first investigators determined the USS Maine sank because of. an outside mine.

a tendency to view things in a particular way, especially in a way that is prejudiced. feasible. able to be completed. interpret. to explain or understand the meaning of something. magazine. the room on a warship where ammunition is stored. mine. a bomb placed in water that explodes when touched by a ship.

Like Opposition to the Philippine-American War, this assessment gauges students' ability to reason about how evidence supports a historical argument. Students must explain how a report by the Naval Court of Inquiry and a San Francisco newspaper article both support the conclusion that confusion surrounded the sinking of the USS Maine at the time.

The Maine may not have suffered a boiler malfunction or an intentional attack [be it an external mine/torpedo or an internal act of sabotage]. There is a third possibility: Spontaneous detonation of explosives. The USS Maine was equipped to fire armor-piercing shells from its big guns, and the explosive type used in these big shells was wet gun ...

Quizlet has study tools to help you learn anything. Improve your grades and reach your goals with flashcards, practice tests and expert-written solutions today. ... Historical Research and Study: The USS Maine. Log in. Sign up. Get a hint. An investigation of the Maine sinking was held in 1911 because. Click the card to flip. many people did ...

Ince 1877 A-CR Historical Research and Study: The USS Maine Assignment Active Yellow Journalism Which are characteristics of yellow journalism? Check all that apply. sensational language well-supported, fact-based arguments O exaggeration eye-catching headlines telling both sides of a story

A history textbook with a chapter on life in the late 1800s could also be a good source, but it may not provide as detailed information specifically about the USS Maine. A historical novel about the sinking of the USS Maine would be a fictional account and not suitable as a reliable source for historical research.