An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Rev Lat Am Enfermagem

- v.23(6); Nov-Dec 2015

Child development: analysis of a new concept 1

Juliana martins de souza.

2 PhD, Assistant Professor, Departamento de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Catalão, GO, Brazil

Maria de La Ó Ramallo Veríssimo

3 PhD, Professor, Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Objectives:

to perform concept analysis of the term child development (CD) and submit it to review by experts.

analysis of concept according to the hybrid model, in three phases: theoretical phase, with literature review; field phase of qualitative research with professionals who care for children; and analytical phase, of articulation of data from previous steps, based on the bioecological theory of development. The new definition was analyzed by experts in a focus group. Project approved by the Research Ethics Committee.

we reviewed 256 articles, from 12 databases and books, and interviewed 10 professionals, identifying that: The CD concept has as antecedents aspects of pregnancy, factors of the child, factors of context, highlighting the relationships and child care, and social aspects; its consequences can be positive or negative, impacting on society; its attributes are behaviors and abilities of the child; its definitions are based on maturation, contextual perspectives or both. The new definition elaborated in concept analysis was validated by nine experts in focus group. It expresses the magnitude of the phenomenon and factors not presented in other definitions.

Conclusion:

the research produced a new definition of CD that can improve nursing classifications for the comprehensive care of the child.

Introduction

Child Development (CD) is a fundamental part of human development, emphasizing that the brain architecture is shaped in the first years, from the interaction of genetic inheritance and influences of the environment in which the child lives ( 1 - 2 ) .

To promote the health of children, it is essential to understand their peculiarities, as well as environmental conditions favorable to their development ( 3 ) . The understanding of caregivers about the characteristics and needs of children, as a result of their development process, promotes the integral development, because daily care is the major space for the promotion of CD ( 3 ) .

A valuable resource to the nurse performs their job facing all aspects of child development is the Systematization of Nursing Care. It proposes the use of the nursing classifications, standardizing the language used in assisting individuals, families and communities in different settings ( 4 ) . However, for use the nursing classifications in a plan of quality care in the approach of the CD, it is necessary that they address the entire complexity of this phenomenon.

A theoretical study of NANDA-International (NANDA-I) and of the International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP (r)) , which are the most disseminated classifications, found important limitations about the approach of CD ( 5 ) . NANDA-I aims to conduct the language standardization of nursing diagnoses ( 6 ) . ICNP (r) intends to be an unifying mark of nursing terminologies, and it was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a member of the Family of International Classifications ( 7 ) .

NANDA-I has real and risk diagnostics for CD, but there is no promotion diagnostics; these cover the development and growth in a single diagnosis, although they are separate phenomena, with different features and definitions and subject to various interventions ( 5 ) .

In ICNP, there are several focus terms related to the child development phenomenon, but these terms do not explain it. The focus terms growth and development are defined as separate terms, but their descriptions are confusing, mixing the two concepts ( 5 ) .

When considering the limitations of the CD approach in the two studied classifications, it is possible to suppose a few reasons why the topic has not yet been better studied in both classifications. One of them is the prioritization of biological aspects in health care, with few instruments and approaches that support promotion actions. In this sense, the development of the child is rarely observed in health care ( 8 - 9 ) . In addition, CD is a broad and complex process, better clarified in recent decades, including its relationship with the daily care and the influence of the environment on it ( 1 ) .

Thus, the difficulties in having nursing diagnoses related to CD can occur in the absence of an approach that encompasses the complexity of the term and the absence of a concept to support the specificity of nursing in the child health. Therefore, it is essential to perform the analysis of the CD concept, to subsidize the classifications of nursing diagnoses and provide diagnostics that enable the development of care plans aimed to CD.

This research aimed to perform the concept analysis of the term child development and analyze the new definition proposed as a product of the concept analysis.

The concept analysis aims to clarify, recognize and define concepts that describe nursing phenomena, in order to promote understanding. The clarification of a certain concept contributes to the knowledge construction of the area ( 10 ) .

The hybrid model of concept development was used in this research. It considers three interconnected stages for the development of the concept: theoretical phase, field phase and analytical phase ( 11 ) . In each one of the stages, the four categories of concept analysis must be composed of: attributes, antecedents, consequences and concept definition.

The theoretical phase corresponds to the study of literature. Since CD is a subject of study in several disciplines, it was important to consult databases which comprised other areas besides health, such as education, behavioral sciences and social sciences. Ten databases and two information portals for research were selected with expert support in information science: BVS, Lilacs, Cochrane Library, Cinahl, Pubmed, Francis, Edubase, Eric, Psycinfo, IndexPsi, Scopus and Web Of Science. Later, textbooks of pediatric nursing were consulted to contemplate some aspects of the concept that the articles from databases did not present.

Child Development and its corresponding descriptors were used, and limits that could ensure the comprehensiveness of the theme and reliability on clipping were established, reducing the number of studies to a viable volume: year of publication - 2011 and 2012; language - Portuguese, English and Spanish; and age group - under 1 year. Search issues followed the model of concept analysis. To set the antecedents of CD, we researched: What factors influence CD? To establish its attributes, the question was: What are the characteristics of CD? To find its consequences, the question was: What are the consequences of adequate CD and inadequate CD? And for its definition, the question was: What is CD?

The field phase consists of research with subjects of the practice who work with the phenomenon under study. Qualitative research was carried out, with semi-structured interviews with professionals working with child development in five municipalities of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, and who participated in earlier CD trainings, for being potentially interested in the subject and work in professional activities related to promotion of CD. The interviews followed the same issues of the bibliographic search. The data recorded and transcribed were subjected to content analysis, according to pre-established categories on hybrid method of concept analysis.

The analytical phase was the articulation of the results of theoretical and field stages and allowed the characterization of the concept components more broadly, as well as the elaboration of a definition of the CD term.

The CD definition elaborated was subjected to review by experts. Although the hybrid model does not propose this step, it was considered that it would give greater consistency to the concept created. To facilitate and intensify the discussion, we decided to perform the analysis of the definition of the concept in a focus group.

The experts were located from a group of people registered in the database of the research group Health Care and Child's Development Promotion, of the School of Nursing at the University of São Paulo, for being considered potential collaborators and meeting the selection criteria. The invitation to take part in the focus group was sent to 30 people who met the inclusion criteria: work with child health for over three years and be an expert, master or doctor in the area of child health. To encourage the participation of professionals outside São Paulo, the focus group was planned for the same day of other event of the research group, aiming to optimize the cost of transportation, since there would be no reimbursement of expenses for participants. The discussion was recorded and transcribed to support the description of the results.

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing at the University of São Paulo (protocol CEP 0114.0.196000-11), and all the participants signed a Free and Informed Consent Term.

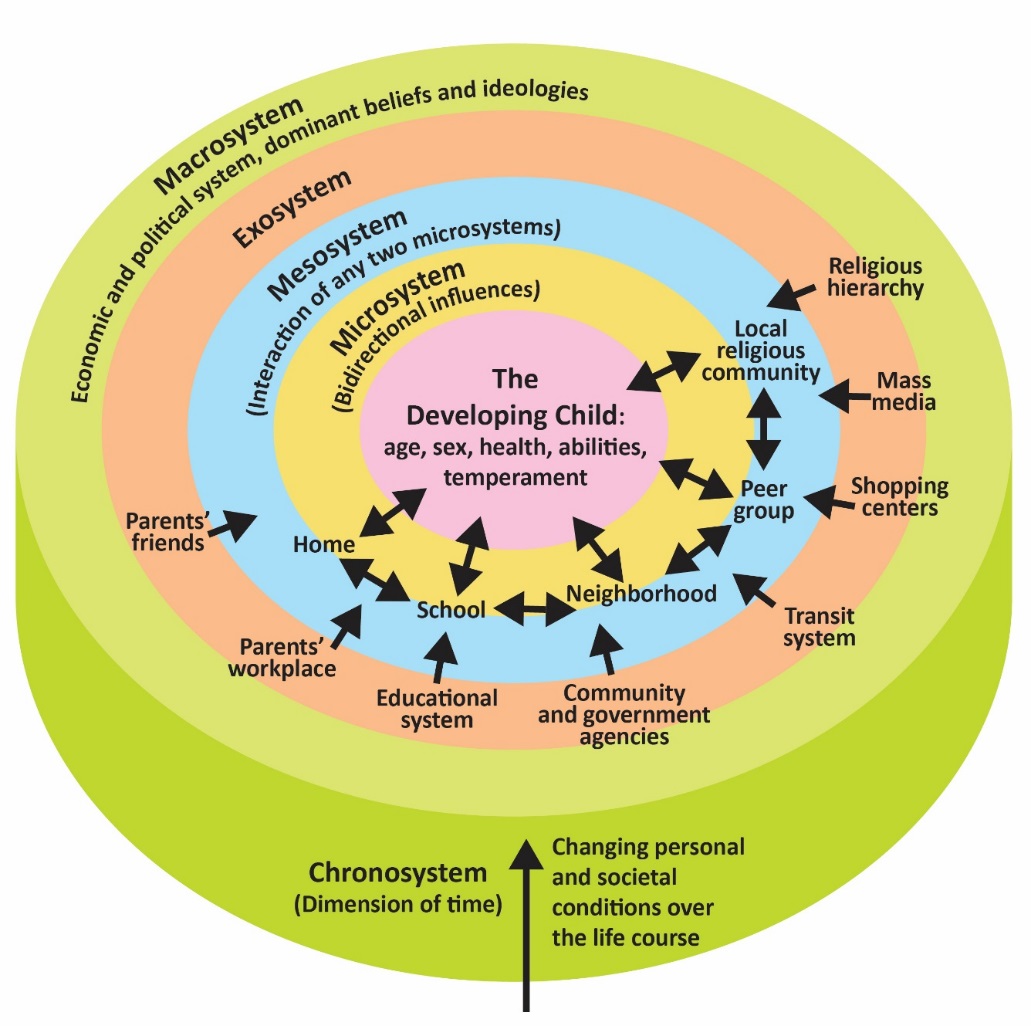

The results were discussed according to the Bioecological Theory of Human Development ( 12 - 13 ) , composed of four interconnected elements: process-person-context-time. The development process involves the relationship between the individual and context, considers all interactions and conditions of these interactions with any implication for the development of the human being; the person is considered with all biological, cognitive, behavioral and emotional characteristics; the context refers to all environments that influence development; and the time involves the issues of temporality, constituting the cronosystem that suppress the changes throughout life ( 13 ) . The context is comprised in a broadened form, composed of: microsystem, which includes the nearest environments in which the child lives; mesosystem, which includes interaction of microsystems in which the child is present; exosystems, the environments in which the child is not inserted, but that affect their development, as the work of parents; and macrosystem, which encompasses social and cultural structures and socioeconomic conditions ( 12 - 13 ) .

In the theoretical phase, 256 articles that met the criteria were selected and classified according to the four categories of concept analysis: concept antecedents (228 studies), concept attributes (5 studies), concept consequences (32 studies) and concept definition (23 studies). Of the 256 articles analyzed, only 12 were Brazilian. Most articles (210) were published in the year of 2011 and 46 were published until April 2012. Publishing journals were very varied, only two articles were published in journals in the nursing field, three in education, 16 in journals of child development, 23 in journals about human development, 29 in behavioral sciences and 183 in journals in the health area - 80 of these specific to pediatrics.

Six nurses, two pedagogues, one psychologist and one social worker attended the field phase; all were women, with an average age of 42.2 years. Half the participants had more than 10 years and three more than 25 years of academic completion. The time of work with child care ranged from two to more than 20 years.

The category antecedents of the concept was composed of factors related to CD found in literature and in the talks of professionals, not differing in content ( Figure 1 ). Theoretical and field phases were complementary, since sometimes the talk of professionals was more generic, but brought additional data to literature.

The category attributes of the concept demonstrates the characteristics present when the concept occurs, and such characteristics were verified both in the literature and field research, as the range of abilities in various development areas ( Figure 1 ). Searching the literature, few studies have addressed these abilities and they focused on evaluation and analysis of the achievement of certain abilities, such as language, to walk, pincer grasp and cognitive development, and was therefore necessary to complement the content by searching in textbooks about the major theories of CD.

Scholars and theorists whose studies are widely used in the CD approach, as Sigmund Freud, Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget explained the development in stages according to the approximate age, describing the characteristics of behavior or abilities of various areas of development, such as motor, cognitive, and emotional ( 14 - 15 ) . We concluded that such areas are the characteristics or attributes of development, so it is by the observation of behaviors and abilities in the areas of development that the course of development of the child can be verified.

For the category concept consequences, we selected articles that addressed evaluations of long term CD or in higher age groups, such as school children and teenagers. There were formed two sets of consequences: those relating to adequate CD and those relating inadequate CD. The interviews adressed the same two sets of consequences and the same topics ( Figure 1 ).

In the category definition of the concept, initially, we grouped articles that discussed more conceptual factors. However, we observed, both in these and in other studied articles, that there were no new definitions to the term child development, once they based on classical definitions of scholars to development. Seeking more data about the concept definition, we revised the main approaches of the development and principal authors of reference on the subject ( 14 - 15 ) .

Figure 1 summarizes the analytical phase of the study, of articulation between the data of the field and theoretical phases. The category antecedents is indicated by the connective "is influenced by"; the category attributes is indicated by the connective "is characterized by"; the category consequences is indicated by the connectives "when adequate leads to" and "when inadequate leads to"; and the category definition is indicated by the connective "is defined as".

As a product of the concept analysis, according to the hybrid model, the following definition of the term child development was elaborated:

"Child development is part of human development, a unique process of each child that aims to insert him/her in the society where he/she lives. It is expressed by continuity and changes in motor, psychosocial, cognitive and language abilities, with progressively more complex acquisitions in the daily life functions. The prenatal period and the first years of life are the foundation of this process, which arises from the interaction of biopsychological characteristics genetically inherited, and experiences offered by the environment. The experiences are constituted by the care that the child receives and the opportunities that the child has to actively exercise his/hers abilities. The care aimed at the needs of development enables the child to reach full potential at every stage of development, with positive repercussions in adult life" ( 16 ) .

This definition was submitted to the analysis of a group of experts. The focus group had nine participants, besides the researcher who coordinated the group, and her mentor as an observer. Seven nurses, one doctor and one physical therapist participated. There were people from the states of: São Paulo (five), Minas Gerais (two) and Paraná (two). They concluded their undergraduate courses from six to 30 years, but most of them (seven) had from 5 to 15 years of experience. As to professional qualification, one participant had specialization in the area of Neonatal and Pediatric Intensive Care and Public Health Management; two had specialization and master's degree; one had specialization, master's and doctoral degrees; and five had master's degree. Seven participants had publications in the pediatrics area.

The group considered that the definition should be more concise, highlighting child development as fundamental to human development, the active role of children in the development process and care as a key element for the promotion of child development. The considerations on the definition of the concept were compatible with the results of the concept analysis, but we realize that they had not been properly incorporated in the first definition proposal.

The definition was rewritten as:

"Child development is a fundamental part of human development, an active and unique process for each child, expressed by continuity and changes in motor, psychosocial, cognitive and language abilities, with acquisitions progressively more complex in the functions of daily life and in the exercise of their social role. The prenatal period and the first years of child life are crucial in the development process, which is constituted by the interaction of biopsychological characteristics genetically inherited, and experiences offered by the environment. The achievement of the potential of every child depends on the care responsive to their needs of development" ( 16 ) .

The results of the concept analysis showed the incorporation of knowledge consistent with the bioecological theory, both in analyzed studies and in the interviews, as pointed out in this discussion, which was structured according to the four elements of the theory process-person-context-time ( 13 ) .

In relation to the process, the interactions of the child, recognized as a central component of development, have achieved great prominence in the field phase. In the theoretical phase, studies that analyzed the bond and the interaction of the parents with the child also showed this relationship. However, we observed in the two data sets an emphasis on the role of caregivers and less emphasis on the active role of the child in the interactions with people, objects and symbols present in their immediate environment, as is highlighted by the bioecological theory.

Interaction is crucial to development. When relationships are imbued with affection, they allow the formation of a bond that will continue to exist, even when these individuals are not together, being fundamental to the child in the establishment of relations in other social contexts beyond the familiar environment ( 13 ) .

Still concerning the process, the characteristics of caregivers, especially their mental health, directly affect their interaction with the child. In this sense, the role of the professional can be a factor of support to assist in improving this relationship.

A second element of the bioecological theory is the person, considering his/her biopsychological characteristics and those built when interacting with the environment ( 12 ) . In the bioecological model, the characteristics of the person are both producers and products of development, because they are one of the elements that influence the form, content and direction of the proximal processes. The person is in the center of the ecological system ( 12 ) .

For the professionals who participated in this study, it seems that environmental aspects supersede the individual, since they stood out. Intrinsic factors of the child were cited in the field phase as factors influencing CD, but with superficial narratives; in the theoretical phase many studies showed the influence of prematurity and low birth weight, child nutrition, growth and diseases.

In relation to the context, the environment in which the child is inserted had highlights in the theoretical and field phases, in line with Bronfenbrenner, who stresses the importance of the environment in the context, dividing it into mesosystem, microsystem, exosystem and macrosystem (12-13). In this study, the factors cited as influential for child development are parts of all these systems:

- - Microsystem: evidenced in the family environment and in some studies in shelters. The importance of the bond, parental interaction with the child and features of the environment in which the child lives were also highlighted;

- - Mesosystem: the influence of environments in which the child in development is inserted, such as day nurseries, was identified in several studies and in professionals' statements;

- - Exosystem: the relationship between exosystem and development was not referred to directly in the field phase. We did not find studies in the theoretical phase that referred to this focus. However, it is possible to identify the existence of this level, although not explained, when considered the influence of interactions, since the exosystems directly influence these relationships, as an event in the work of parents or school of the brothers which reverberate in the microsystem and existing relations;

- - Macrosystem: some studies and professionals' statements point out the broader structure factors that influence development, such as socioeconomic and cultural conditions.

The fourth element of the theory (time) showed up in the results as the data referred to a development process that does not occur instantly during children's interactions and experiences, but are being built in their life time. The two sets of data mentioned only the individual development processes, without referring to the idea of continuities and changes in the development of children that could be identified as products of socio-historical changes between generations.

All aspects of the process, context and person can be classified as protectors, when offering favorable influences to CD or as a risk or vulnerability to CD, when their influences are potentially harmful. Therefore, all these aspects should be the focus of attention in public policies and in social and community practices.

To cover the search results, the proposed definition incorporated factors that are not explored in other definitions, such as mention children as active in their development and care as a central element of this process. This definition is compatible with the bioecological theory of development, because it presents the concept of person in development, environment and interaction between them, and also evidences the four theory elements: process, person, context and time, as follows.

- - Process: explicit throughout the concept, emphasizing the importance of care aimed at the needs of development; is related to interactions, bonds, and affection, stressing the importance of the experiences of the child.

- - Context: all levels of context are considered essential because they determine child's experiences and the care they receive; includes family and other environments that will share this care and experiences.

- - Person: development is an unique process for each child, of continuity and changes of motor, psychosocial, cognitive and language abilities, and of biopsychological characteristics, genetically inherited.

- - Time: the definition presents research findings from neuroscience and contemporary researches for child development as a fundamental part of human development, highlighting the prenatal period and the first years of life as a milestone of this process. The definition of the concept reflects current science.

Thus, this definition may subsidize nursing classifications in the elaboration of diagnoses, interventions and outcomes related to child development.

It is important to stress that the choice of the focus group as a technique for performing the analysis by experts was crucial, because it provided discussion among experts and immediate result, without requiring new steps of data analysis and re-evaluation by the experts, which is observed in the literature as a difficulty of methods that require several steps of analysis ( 17 ) . The experience of the participants in the research and academic writing, whether in graduate studies or guidance of students of undergraduate research, in their role as teachers, favored the discussion of the concept presented, achieving great depth of analysis.

It is possible to point out as a limitation of this study the need to delimit the search time on literature review for a year, but by observing the quality of the results obtained, it was considered that there were no losses and, therefore, the search expansion for this research was not considered. The inclusion of textbooks to compose the attributes and definitions of the concept could also be limiting, however, criteria were used for choice of references, assuring the content quality.

The selection of subjects involved in the CD training project of the municipalities was important because, for the concept analysis, it is crucial that participants have extensive experience in the matter. However, it can be one of the limitations of the study, since the statements incorporated knowledge covered during training, and research with professionals with other experiences may differ.

The performance of concept analysis, according to the hybrid model, was crucial for the elaboration of a concept that took into account the complexity of the phenomenon, since data from the literature review and field phase were complementary and demonstrated the incorporation of updated knowledge among professionals. Such analysis, in addition to the expert analysis, contributed to the construction of a concept applicable in practice, because, when presenting the development as a result of the interaction of the child with the environment and the relationships existing therein. This will subsidize the revision of nursing diagnoses and the appropriate selection of actions to promote CD, a fundamental aspect to the actions of the nurse in monitoring the health of the child.

1 Paper extracted from doctoral dissertation "Child development: concept analysis and NANDA-I's diagnoses review", presented to Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil, process # 2011/51012-3.

What Is Early Childhood Development? A Guide to the Science (ECD 1.0)

Healthy development in the early years (particularly birth to three) provides the building blocks for educational achievement, economic productivity, responsible citizenship, lifelong health, strong communities, and successful parenting of the next generation. What can we do during this incredibly important period to ensure that children have a strong foundation for future development? The Center on the Developing Child created this Guide to Early Childhood Development (ECD) to help parents, caregivers, practitioners, and policymakers understand the importance of early childhood development and learn how to support children and families during this critical stage.

Visit “ Introducing ECD 2.0 ” for new resources that build on the knowledge presented below.

Step 1: Why Is Early Childhood Important?

This section introduces you to the science that connects early experiences from birth (and even before birth) to future learning capacity, behaviors, and physical and mental health.

This 3-minute video portrays how actions taken by parents, teachers, policymakers, and others can affect life outcomes for both the child and the surrounding community.

InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

This video from the InBrief series addresses basic concepts of early childhood development, established over decades of neuroscience and behavioral research.

This brief explains how the science of early brain development can inform investments in early childhood, and helps to illustrate why child development—particularly from birth to five years—is a foundation for a prosperous and sustainable society.

Step 2: How Does Early Child Development Happen?

Now that you understand the importance of ECD, this section digs deeper into the science, including how early experiences and relationships impact and shape the circuitry of the brain, and how exposure to toxic stress can weaken the architecture of the developing brain.

Three Core Concepts in Early Development

Advances in neuroscience, molecular biology, and genomics now give us a much better understanding of how early experiences are built into our bodies and brains, for better or worse. This three-part video series explains.

8 Things to Remember about Child Development

In this important list, featured in the From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts report, the Center on the Developing Child sets the record straight about some aspects of early child development.

InBrief: The Science of Resilience

This brief summarizes the science of resilience and explains why understanding it will help us design policies and programs that enable more children to reach their full potential.

Step 3: What Can We Do to Support Child Development?

Understanding how important early experiences and relationships are to lifelong development is one step in supporting children and families. The next step is to apply that knowledge to current practices and policies. This section provides practical ways that practitioners and policymakers can support ECD and improve outcomes for children and families.

From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

This report synthesizes 15 years of dramatic advances in the science of early childhood and early brain development and presents a framework for driving science-based innovation in early childhood policy and practice.

Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families

Understanding how the experiences children have starting at birth, even prenatally, affect lifelong outcomes—as well as the core capabilities adults need to thrive—provides a strong foundation upon which policymakers and civic leaders can design a shared and more effective agenda.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

Chapter objectives.

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Evaluate issues in development.

- Distinguish the different methods of research.

- Explain what a theory is.

- Compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Introduction

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn.

We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence. 1

Principles of Development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). And early experiences affect later development.

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development, while showing loss in other areas.

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and social and emotional.

- The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness.

- The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language.

- The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains.

- Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

- Development is multicontextual. 2 We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. 3

Now let’s look at a framework for examining development.

Periods of Development

Think about what periods of development that you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers. Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through two years)

- Early Childhood (3 to 5 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 11 years)

- Adolescence (12 years to adulthood)

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adolescence that will be explored in this book. So while both an 8 month old and an 8 year old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Figure 1.1 – A tiny embryo depicting some development of arms and legs, as well as facial features that are starting to show. 4

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Figure 1.2 – A swaddled newborn. 5

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Figure 1.3 – Two young children playing in the Singapore Botanic Gardens 6

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. And children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Figure 1.4 – Two children running down the street in Carenage, Trinidad and Tobago 7

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. 8

Figure 1.5 – Two smiling teenage women. 9

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated. Let’s explore these.

Issues in Development

Nature and nurture.

Why are people the way they are? Are features such as height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc. the result of heredity or environmental factors-or both? For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the side of Nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of Nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

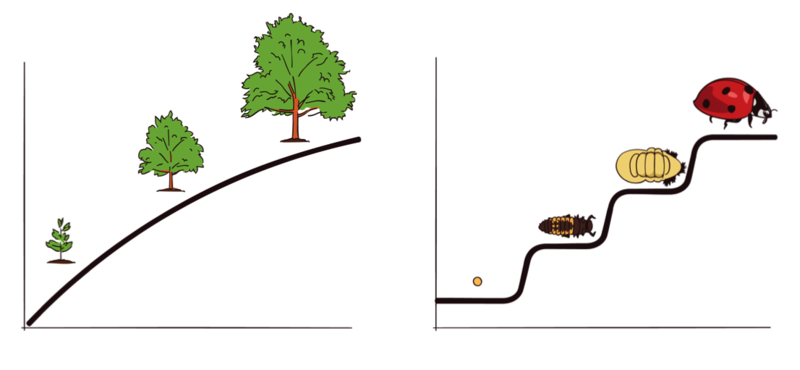

Continuity versus Discontinuity

Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

Figure 1.6 – The graph to the left shows three stages in the continuous growth of a tree. The graph to the right shows four distinct stages of development in the life cycle of a ladybug. 10

Active versus Passive

How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their own development. Piaget, for instance believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process. 11

How do we know so much about how we grow, develop, and learn? Let’s look at how that data is gathered through research

Research Methods

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Some people are hesitant to trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality) or based on what others have told you or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry. Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the

Are you sure that is what it said? Read it again:

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence. Popper suggests that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). Theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons guard against bias.

Scientific Methods

One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making your findings available to others (both to share information and to have your work scrutinized by others)

Your findings can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest and through this process a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantifying or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Many academic journals publish reports on studies conducted in this manner.

Another model of research referred to as qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest

- Ask open ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers are to be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

Let’s look more closely at some techniques, or research methods, used to describe, explain, or evaluate. Each of these designs has strengths and weaknesses and is sometimes used in combination with other designs within a single study.

Observational Studies

Observational studies involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play at a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event (such as observing children in a classroom and capturing the details about the room design and what the children and teachers are doing and saying). In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. What people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. Children tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect) and may not survey well.

Experiments

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables) in a controlled setting in efforts to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research, which means that the researcher must specify exactly what is going to be measured in the study.

Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions.

The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. (The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.)

The cause must come before the effect. Experiments involve measuring subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events, which makes understanding causality problematic with these designs.)

The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables are actually causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, diet might really be creating the change in stress level rather than exercise.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group. The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable.

The major advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what happens in a laboratory setting into real life.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison.

Figure 1.7 – Illustrated poster from a classroom describing a case study. 12

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” This is known as Likert Scale . Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many independent and dependent variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. Analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report or what people say they do rather than on observation and this can limit accuracy.

Developmental Designs

Developmental designs are techniques used in developmental research (and other areas as well). These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

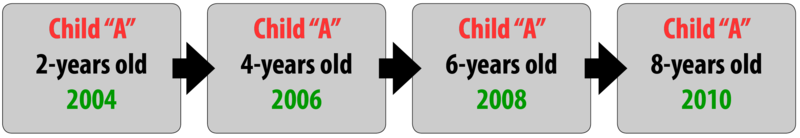

Longitudinal Research

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background, and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with them when they were younger.

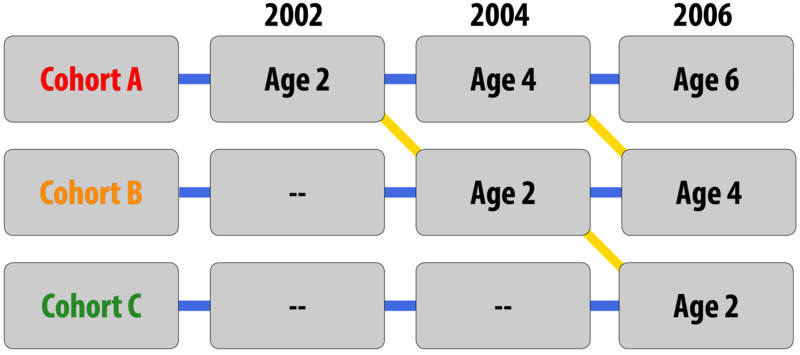

Figure 1.8 – A longitudinal research design. 13

A problem with this type of research is that it is very expensive and subjects may drop out over time. The Perry Preschool Project which began in 1962 is an example of a longitudinal study that continues to provide data on children’s development.

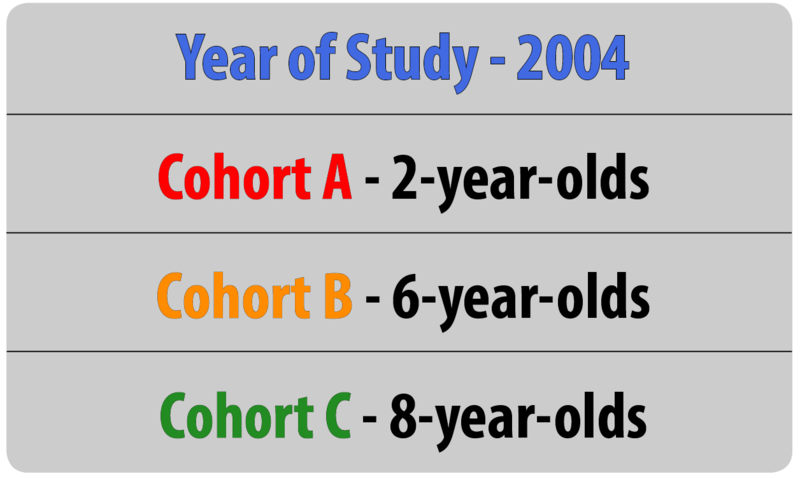

Cross-sectional Research

Cross-sectional research involves beginning with a sample that represents a cross-section of the population. Respondents who vary in age, gender, ethnicity, and social class might be asked to complete a survey about television program preferences or attitudes toward the use of the Internet. The attitudes of males and females could then be compared, as could attitudes based on age. In cross-sectional research, respondents are measured only once.

Figure 1.9 – A cross-sectional research design. 14

This method is much less expensive than longitudinal research but does not allow the researcher to distinguish between the impact of age and the cohort effect. Different attitudes about the use of technology, for example, might not be altered by a person’s biological age as much as their life experiences as members of a cohort.

Sequential Research

Sequential research involves combining aspects of the previous two techniques; beginning with a cross-sectional sample and measuring them through time.

Figure 1.10 – A sequential research design. 15

This is the perfect model for looking at age, gender, social class, and ethnicity. But the drawbacks of high costs and attrition are here as well. 16

Table 1 .1 – Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Research Designs 17

Consent and Ethics in Research

Research should, as much as possible, be based on participants’ freely volunteered informed consent. For minors, this also requires consent from their legal guardians. This implies a responsibility to explain fully and meaningfully to both the child and their guardians what the research is about and how it will be disseminated. Participants and their legal guardians should be aware of the research purpose and procedures, their right to refuse to participate; the extent to which confidentiality will be maintained; the potential uses to which the data might be put; the foreseeable risks and expected benefits; and that participants have the right to discontinue at any time.

But consent alone does not absolve the responsibility of researchers to anticipate and guard against potential harmful consequences for participants. 18 It is critical that researchers protect all rights of the participants including confidentiality.

Child development is a fascinating field of study – but care must be taken to ensure that researchers use appropriate methods to examine infant and child behavior, use the correct experimental design to answer their questions, and be aware of the special challenges that are part-and-parcel of developmental research. Hopefully, this information helped you develop an understanding of these various issues and to be ready to think more critically about research questions that interest you. There are so many interesting questions that remain to be examined by future generations of developmental scientists – maybe you will make one of the next big discoveries! 19

Another really important framework to use when trying to understand children’s development are theories of development. Let’s explore what theories are and introduce you to some major theories in child development.

Developmental Theories

What is a theory.

Students sometimes feel intimidated by theory; even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories…” is met with blank stares and other indications that the audience is now lost. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior; in fact they are proposed explanations for the “how” and “whys” of development. Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3 year old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Developmental theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time and the kinds of influences that impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help one piece together smaller parts more easily than if trial and error are used.

Theories can be developed using induction in which a number of single cases are observed and after patterns or similarities are noted, the theorist develops ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them. 20

Let’s take a look at some key theories in Child Development.

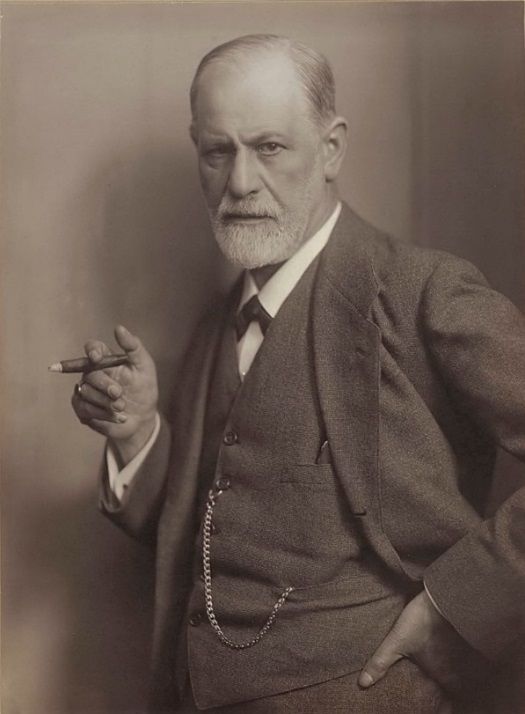

Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

We begin with the often controversial figure, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud has been a very influential figure in the area of development; his view of development and psychopathology dominated the field of psychiatry until the growth of behaviorism in the 1950s. His assumptions that personality forms during the first few years of life and that the ways in which parents or other caregivers interact with children have a long-lasting impact on children’s emotional states have guided parents, educators, clinicians, and policy-makers for many years. We have only recently begun to recognize that early childhood experiences do not always result in certain personality traits or emotional states. There is a growing body of literature addressing resilience in children who come from harsh backgrounds and yet develop without damaging emotional scars (O’Grady and Metz, 1987). Freud has stimulated an enormous amount of research and generated many ideas. Agreeing with Freud’s theory in its entirety is hardly necessary for appreciating the contribution he has made to the field of development.

Figure 1.11 – Sigmund Freud. 21

Freud’s theory of self suggests that there are three parts of the self.

The id is the part of the self that is inborn. It responds to biological urges without pause and is guided by the principle of pleasure: if it feels good, it is the thing to do. A newborn is all id. The newborn cries when hungry, defecates when the urge strikes.

The ego develops through interaction with others and is guided by logic or the reality principle. It has the ability to delay gratification. It knows that urges have to be managed. It mediates between the id and superego using logic and reality to calm the other parts of the self.

The superego represents society’s demands for its members. It is guided by a sense of guilt. Values, morals, and the conscience are all part of the superego.

The personality is thought to develop in response to the child’s ability to learn to manage biological urges. Parenting is important here. If the parent is either overly punitive or lax, the child may not progress to the next stage. Here is a brief introduction to Freud’s stages.

Table 1. 2 – Sigmund Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

Strengths and Weaknesses of Freud’s Theory

Freud’s theory has been heavily criticized for several reasons. One is that it is very difficult to test scientifically. How can parenting in infancy be traced to personality in adulthood? Are there other variables that might better explain development? The theory is also considered to be sexist in suggesting that women who do not accept an inferior position in society are somehow psychologically flawed. Freud focuses on the darker side of human nature and suggests that much of what determines our actions is unknown to us. So why do we study Freud? As mentioned above, despite the criticisms, Freud’s assumptions about the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping our psychological selves have found their way into child development, education, and parenting practices. Freud’s theory has heuristic value in providing a framework from which to elaborate and modify subsequent theories of development. Many later theories, particularly behaviorism and humanism, were challenges to Freud’s views. 22

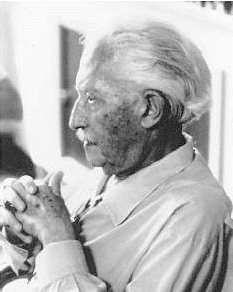

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Now, let’s turn to a less controversial theorist, Erik Erikson. Erikson (1902-1994) suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development. Erikson was a student of Freud’s but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and we consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Figure 1.12 – Erik Erikson. 23

Erikson expanded on his Freud’s by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages. In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living. Here is a brief overview of the eight stages:

Table 1. 3 – Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the life span. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices. 24

Behaviorism

While Freud and Erikson looked at what was going on in the mind, behaviorism rejected any reference to mind and viewed overt and observable behavior as the proper subject matter of psychology. Through the scientific study of behavior, it was hoped that laws of learning could be derived that would promote the prediction and control of behavior. 25

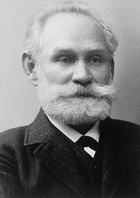

Ivan Pavlov

Ivan Pavlov (1880-1937) was a Russian physiologist interested in studying digestion. As he recorded the amount of salivation his laboratory dogs produced as they ate, he noticed that they actually began to salivate before the food arrived as the researcher walked down the hall and toward the cage. “This,” he thought, “is not natural!” One would expect a dog to automatically salivate when food hit their palate, but BEFORE the food comes? Of course, what had happened was . . . you tell me. That’s right! The dogs knew that the food was coming because they had learned to associate the footsteps with the food. The key word here is “learned”. A learned response is called a “conditioned” response.

Figure 1.13 – Ivan Pavlov. 26

Pavlov began to experiment with this concept of classical conditioning . He began to ring a bell, for instance, prior to introducing the food. Sure enough, after making this connection several times, the dogs could be made to salivate to the sound of a bell. Once the bell had become an event to which the dogs had learned to salivate, it was called a conditioned stimulus . The act of salivating to a bell was a response that had also been learned, now termed in Pavlov’s jargon, a conditioned response. Notice that the response, salivation, is the same whether it is conditioned or unconditioned (unlearned or natural). What changed is the stimulus to which the dog salivates. One is natural (unconditioned) and one is learned (conditioned).

Let’s think about how classical conditioning is used on us. One of the most widespread applications of classical conditioning principles was brought to us by the psychologist, John B. Watson.

John B. Watson

John B. Watson (1878-1958) believed that most of our fears and other emotional responses are classically conditioned. He had gained a good deal of popularity in the 1920s with his expert advice on parenting offered to the public.

Figure 1.14 – John B. Watson. 27

He tried to demonstrate the power of classical conditioning with his famous experiment with an 18 month old boy named “Little Albert”. Watson sat Albert down and introduced a variety of seemingly scary objects to him: a burning piece of newspaper, a white rat, etc. But Albert remained curious and reached for all of these things. Watson knew that one of our only inborn fears is the fear of loud noises so he proceeded to make a loud noise each time he introduced one of Albert’s favorites, a white rat. After hearing the loud noise several times paired with the rat, Albert soon came to fear the rat and began to cry when it was introduced. Watson filmed this experiment for posterity and used it to demonstrate that he could help parents achieve any outcomes they desired, if they would only follow his advice. Watson wrote columns in newspapers and in magazines and gained a lot of popularity among parents eager to apply science to household order.

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, looks at the way the consequences of a behavior increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. So let’s look at this a bit more.

B.F. Skinner and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner (1904-1990), who brought us the principles of operant conditioning, suggested that reinforcement is a more effective means of encouraging a behavior than is criticism or punishment. By focusing on strengthening desirable behavior, we have a greater impact than if we emphasize what is undesirable. Reinforcement is anything that an organism desires and is motivated to obtain.

Figure 1.15 – B. F. Skinner. 28

A reinforcer is something that encourages or promotes a behavior. Some things are natural rewards. They are considered intrinsic or primary because their value is easily understood. Think of what kinds of things babies or animals such as puppies find rewarding.

Extrinsic or secondary reinforcers are things that have a value not immediately understood. Their value is indirect. They can be traded in for what is ultimately desired.

The use of positive reinforcement involves adding something to a situation in order to encourage a behavior. For example, if I give a child a cookie for cleaning a room, the addition of the cookie makes cleaning more likely in the future. Think of ways in which you positively reinforce others.

Negative reinforcement occurs when taking something unpleasant away from a situation encourages behavior. For example, I have an alarm clock that makes a very unpleasant, loud sound when it goes off in the morning. As a result, I get up and turn it off. By removing the noise, I am reinforced for getting up. How do you negatively reinforce others?

Punishment is an effort to stop a behavior. It means to follow an action with something unpleasant or painful. Punishment is often less effective than reinforcement for several reasons. It doesn’t indicate the desired behavior, it may result in suppressing rather than stopping a behavior, (in other words, the person may not do what is being punished when you’re around, but may do it often when you leave), and a focus on punishment can result in not noticing when the person does well.

Not all behaviors are learned through association or reinforcement. Many of the things we do are learned by watching others. This is addressed in social learning theory.

Social Learning Theory

Albert Bandura (1925-) is a leading contributor to social learning theory. He calls our attention to the ways in which many of our actions are not learned through conditioning; rather, they are learned by watching others (1977). Young children frequently learn behaviors through imitation

Figure 1.16 – Albert Bandura. 29

Sometimes, particularly when we do not know what else to do, we learn by modeling or copying the behavior of others. A kindergartner on his or her first day of school might eagerly look at how others are acting and try to act the same way to fit in more quickly. Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role-models. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. They were operantly conditioned, but we engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. This is referred to as vicarious reinforcement (Bandura, Ross and Ross, 1963).

Bandura (1986) suggests that there is interplay between the environment and the individual. We are not just the product of our surroundings, rather we influence our surroundings. Parents not only influence their child’s environment, perhaps intentionally through the use of reinforcement, etc., but children influence parents as well. Parents may respond differently with their first child than with their fourth. Perhaps they try to be the perfect parents with their firstborn, but by the time their last child comes along they have very different expectations both of themselves and their child. Our environment creates us and we create our environment. 30

Theories also explore cognitive development and how mental processes change over time.

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists. Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Figure 1.17 – Jean Piaget. 32

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium . This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour”. All of these are schema. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schema and to modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation . So the person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our mind. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation . Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schema. Adults tend to look for similarity in their experience and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.”

Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this into four stages:

Table 1.4 – Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) plays in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances. 33

Lev Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s. Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development . 34 His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning. 35

Figure 1.18- Lev Vygotsky. 36

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern day educators. 37

Comparing Piaget and Vygotsky

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities. 38

Like Vygotsky’s, Bronfenbrenner looked at the social influences on learning and development.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

Figure 1.19 – Urie Bronfenbrenner. 39

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.

Table 1.5 – Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

For example, in order to understand a student in math, we can’t simply look at that individual and what challenges they face directly with the subject. We have to look at the interactions that occur between teacher and child. Perhaps the teacher needs to make modifications as well. The teacher may be responding to regulations made by the school, such as new expectations for students in math or constraints on time that interfere with the teacher’s ability to instruct. These new demands may be a response to national efforts to promote math and science deemed important by political leaders in response to relations with other countries at a particular time in history.

Figure 1.20 – Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. 40

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model challenges us to go beyond the individual if we want to understand human development and promote improvements. 41

In this chapter we looked at:

underlying principles of development

the five periods of development

three issues in development

Various methods of research

important theories that help us understand development

Next, we are going to be examining where we all started with conception, heredity, and prenatal development.

Child Growth and Development Copyright © by Jean Zaar is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- NAEYC Login