- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Understanding Gambling Addiction

- Steps to Getting Treatment

- Stopping a Gambling Addiction

Gambling disorder (also called gambling addiction) is characterized by repeated, problem gambling behavior that leads to problems for the individual and their loved ones. Approximately 1% of the population currently has a gambling disorder. Some common symptoms of gambling disorder include not stopping or controlling gambling, lying about gambling, being preoccupied with gambling, and spending excessive amounts of time gambling.

Gambling disorder can cause problems with mental and physical health, relationships, finances, and more. Treatment options for gambling disorder include counseling, medications, and support groups.

This article will discuss what gambling addiction is, symptoms of gambling addiction, causes and risk factors for gambling addiction, effects of gambling addiction, treatment for gambling addiction, and coping through gambling addiction treatment.

andresr / Getty Images

Defining Gambling Addiction

To meet the criteria for a diagnosis of gambling disorder, at least four of the following must have occurred during the past year and caused significant distress:

- Needing to gamble increasingly high monetary amounts to achieve the desired excitement.

- Repeated unsuccessful attempts to cut back on, control, or stop gambling.

- Restlessness or irritability when trying to cut down on or stop gambling.

- Frequently gambling when feeling distressed.

- Frequently thinking about gambling (such as reliving past gambling or planning future gambling).

- Often "chasing one's losses" (i.e., returning to "get even" after losing money gambling).

- Risking or losing a job, school or job opportunity, or close relationship because of gambling.

- Lying to hide gambling activity.

- Relying on others for help with money problems stemming from gambling.

Symptoms of gambling disorder can subside for periods and return.

Gambling problems can develop quickly or over many years. Gambling activities also occur along the following continuum:

- No gambling : People who never gamble

- Casual social gambling : The most common type of gambling. Buying an occasional lottery ticket, occasionally visiting a casino for entertainment, etc.

- Serious social gambling : Regular gambling, and gambling as a primary form of entertainment, but does not harm work or personal relationships.

- Harmful involvement : Gambling that leads to difficulties with personal, work, and social relationships.

- Pathological gambling : Gambling seriously harms all aspects of the person's life, and they are unable to control the urge to gamble despite the harm it is causing.

Typical Symptoms

Symptoms of gambling disorder can vary, but may include:

- Lying about gambling behavior

- Gambling more than you can afford to lose

- Obsessive preoccupation with gambling (excessively thinking about it even when not in the act of gambling)

- Stopping doing things you previously enjoyed

- Ignoring self-care, school, work, or family tasks

- Withdrawing from friends and family

- Missing family events

- Changes in patterns of eating, sleeping, or sex

- Regular lateness for school or work

- Increased alcohol or drug use

- Decreased willingness to spend money on things other than gambling

- Having conflicts with others over money

- Having legal problems related to gambling

- Neglecting your children's needs and welfare (such as leaving them alone, or neglecting their basic care)

- Frequently borrowing money or asking for salary advances

- Cheating or stealing to obtain money for gambling or paying debts

- Taking a second job, without a change in finances

- Cashing in assets such as savings accounts, RRSPs, or insurance plans

- Alternating between being broke and flashing money

- Organizing staff pools

- Leaving for long, unexplained periods

- Feeling anxious

- Having difficulty paying attention

- Having mood swings and sudden bursts of anger

- Feeling bored or restless

- Feeling depressed or having suicidal ideation

Suicide Prevention Hotline

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911 . For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Traits and Signs In Others

Gambling addiction can be hard to recognize, especially since signs often remain hidden until they become severe, such as a dire financial situation.

If you notice symptoms of gambling disorder, such as those mentioned above, in a friend or family member and want to talk to them about it, there are ways to approach it:

- Prepare yourself for many possible reactions from them, including anger and denial.

- Manage your expectations (don't expect them to quit right away; it can take time).

- Be honest when sharing your concerns.

- Remember that stopping their gambling behavior is their responsibility, not yours (you are there for support).

- Don't preach or lecture.

- Remain calm and keep control of your anger.

- Recognize their good qualities.

- Seek support from others in similar situations (such as a self-help group for families, like Gam-Anon).

- Let them know how the gambling is affecting you and, if applicable, the children or other family members.

- If you share finances, set boundaries in managing money (review bank and credit card statements, take control of family finances, etc.).

Causes, Triggers, and Risk Factors

Problem gambling stems from a psychological principle called Variable Ratio Reinforcement Schedule (VRRS). With VRRS, mood-stimulating rewards are variable and unpredictable. This can cause someone to gamble compulsively.

Adolescents and young adults are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of gambling compared to adults. This may be linked to their stage of brain development, with decision-making and impulse-control skills still developing.

Some factors that may contribute to problem gambling behaviors in adolescents and young adults include:

- Increased availability and access to gambling activities without supervision or physical proximity to a gambling venue (through online gambling)

- Gambling as a coping mechanism for stress and anxiety (including previously experienced trauma, abuse, or neglect, and problems with mental health)

- Family history of gambling or addiction

- Peer pressure

- High number of risk behaviors in other areas (such as alcohol and drug use)

- Problems with decision-making and impulse control

- Exposure to gambling (such as "loot boxes") or simulated gambling (such as slot machines using virtual money or points) through video games

- Seeing parents, siblings, or other family members engage in gambling

Gambling disorder can begin at any age. Males are more likely to start at an earlier age, while females are more likely to start later in life.

Some factors that can contribute to the development of (or difficulty stopping) gambling problems include:

- Having easy access to gambling

- Having an early big win, creating an expectation of future wins

- Holding erroneous beliefs about the odds of winning

- Not taking steps to monitor gambling wins and losses

- Having a history of mental health problems, especially depression and anxiety

- Often feeling bored or lonely

- Having a history of risk-taking or impulsive behavior

- Having self-esteem tied to gambling wins or losses

- Having recently had a loss or change, such as job loss, divorce, retirement, or the death of a loved one

Types of Games Associated With Gambling

Gambling activities can include:

- Casino table games

- Electronic gaming machines (such as slot machines and poker machines)

- Horse racing

- Internet gambling sites

- Charitable raffles

All forms of gambling have the potential to be addictive. But ones that are rapid, have immediate large payouts (such as slot machines), involve betting small amounts to win a huge jackpot, or allow you to place multiple bets at one time tend to be at higher risk for addiction.

Effects of Gambling Addiction

Gambling disorder can have far-reaching effects, and cause problems in a number of areas.

Self-Esteem and Mental Health

Problem gambling has been associated with mental health conditions and considerations, such as:

- Increased negative mood states

- Elevated stress levels

- Feelings of helplessness

- Changes in personality or mood

- Increased drug or alcohol use

- Bipolar disorder

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Increased risk of suicide

While gambling disorder may not cause these conditions, it can exacerbate the symptoms and effects associated with them.

Relationships

Gambling disorder can cause people to withdraw from friends and family. Behaviors associated with gambling disorder, such as asking to borrow money, lying, stealing, and not fulfilling responsibilities, can lead to conflict with others. These factors and others can strain personal relationships.

Financial losses are not necessary for a person to have gambling disorder, but they often occur.

People who have gambling disorder may experience financial issues such as:

- Credit card debt and other debts

- Lower credit scores

- Denial of mortgages and loans

- Unpaid bills

- Lack of money for food and other essentials

- Regularly borrowing money

Some people with gambling disorder reach a point they begin selling household items or stealing.

Loss of Time and Productivity

When gambling prioritizes a person's time and becomes a mental preoccupation, it can lead to a loss of productivity at work, school, home, or in other areas.

Physical Health

Gambling disorder, and the stress that comes with it, can lead to health problems such as:

- Sleep disturbances and deprivation

- Poor hygiene and self-care

- Stomach or bowel issues

- Overeating or loss of appetite

A Word From Verywell

If your loved one seems increasingly preoccupied by gambling, is withdrawing from other areas of their life, or is noticing negative consequences to their finances, work, or relationships, it could be a sign that this is something to pay closer attention to.

Steps to Get Gambling Addiction Treatment

Treatment for gambling disorder usually involves counseling, and often support groups. In some cases, medication may also be helpful.

Counseling and Psychotherapy

Counseling and forms of psychotherapy (talk therapy) are first-line approaches to gambling disorder treatment. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most common and frequently studied form of treatment for gambling disorder.

CBT helps people with gambling disorder to identify damaging thought patterns and behavior and modify them into more productive patterns.

CBT for gambling can include components such as:

- Correcting cognitive distortions about gambling

- Developing problem-solving skills

- Learning social skills

- Learning relapse prevention

Other forms of therapy that may be used include:

- Psychodynamic therapy

- Group therapy

- Family therapy

Counseling can help you:

- Deal with gambling urges

- Manage stress and handle other problems

- Gain control over your gambling

- Heal family relationships

- Maintain recovery

- Avoid triggers

Family members affected by a loved one's gambling may also benefit from counseling. Financial counseling can be helpful for those in need of financial recovery and management.

Medications

While there are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for treating gambling disorders, medications that treat co-occurring conditions which can make gambling behavior worse, such as depression or anxiety , can be helpful.

Currently, medications are being studied for their potential in treating gambling disorder, particularly in reducing urges and cravings for gambling. Certain opioid antagonists have been found in randomized trials to be more successful than placebo in the treatment of gambling disorder.

More research is needed to determine if medications can be effectively used as a primary treatment for gambling disorder.

Support Groups

Some people with gambling disorder find peer support through groups such as Gamblers Anonymous to be helpful.

Gamblers Anonymous is a 12-step program in which participants attend meetings, share experiences, and offer each other support as they abstain from gambling.

Gambling Therapy is another organization, similar to Gamblers Anonymous, that offers online support groups to people with gambling disorder and their families.

Support groups are not a substitute for professional treatment.

How to Stop a Gambling Addiction

The first step to stopping gambling addiction is recognizing the problem . Once you realize you have a problem with gambling, it's time to reach out for help.

You can start by contacting your healthcare provider, a mental healthcare professional, or support groups and resources for gambling disorder. From there, you can be put in touch with the programs and resources you will need to start your recovery.

Resources and Support

Places to find resources and support for gambling disorder include:

- Gamblers Anonymous

- National Council on Problem Gambling

- National Problem Gambling Helpline

- Gambling Therapy

Coping Through Gambling Addiction Treatment

Getting professional help for gambling addiction is paramount, but there are strategies you can use at home to help you cope while you go through treatment.

Give yourself actionable, realistic short and long-term goals to help you stay focused.

Distract Yourself

Keep yourself busy with other activities, and look for alternative ways to fill the time you used to spend gambling.

Practice Relaxation

Activities such as yoga , physical activity, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation, can help foster relaxation.

Avoid High-Risk Situations and Triggers

Stay away from gaming venues, avoid carrying cash and credit cards, or anything else that makes you more tempted to gamble . Some gambling venues and apps have options for you to have yourself voluntarily banned from using their services.

Contact Your Supports

Talk to friends and family, or other people you trust. Or go to a Gamblers Anonymous meeting.

Gambling disorder is associated with a number of symptoms, such as being excessively preoccupied with gambling, intense cravings to gamble, and gambling more than you can afford to lose. Gambling disorder can cause problems with relationships, mental and physical health, finances, productivity, and more. Treatments for gambling disorder include counseling, support groups, and medication.

American Psychiatric Association. Gambling disorder .

American Psychiatric Association. What is gambling disorder?

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Problem gambling .

Yale Medicine. Gambling disorder .

ConnexOntario. Five signs you may have a gambling problem .

ConnexOntario. Signs your loved one has a gambling addiction .

Gateway Foundation. How to help someone you know that has a gambling problem .

Rizzo A, La Rosa VL, Commodari E, et al. Wanna bet? Investigating the factors related to adolescent and young adult gambling . EJIHPE. 2023;13(10):2202-2213. doi:10.3390/ejihpe13100155

American Psychological Association. How gambling affects the brain and who is most vulnerable to addiction .

University of California, Los Angeles. Gambling addiction can cause psychological, physiological health challenges .

Healthdirect. Gambling addiction .

University of Nevada. Gambling addiction: Resources, statistics, and hotlines .

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Treatment recommendations for gambling disorders .

Better Help. Gambling - how to regain control .

By Heather Jones Jones is a freelance writer with a strong focus on health, parenting, disability, and feminism.

Exploring experiences of psychological treatments for gambling addiction

--> Marvin, Joshua (2023) Exploring experiences of psychological treatments for gambling addiction. DClinPsy thesis, University of Sheffield.

Literature Review Gambling addiction is now a growing public health concern. However, our understanding of how individuals experience psychological treatment for gambling addiction is limited. It is important to understand such experiences more deeply, particularly as treatment guidance is under development. This qualitative review explored individual experiences of psychological treatment for gambling and what may be found helpful or challenging. A structured search was performed using three research databases. Eight studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included. These were analysed using a method called thematic synthesis. Four themes about individual’s experience of psychological treatment for gambling addiction were found: getting the treatment you need is difficult, treatment can make a difference, obstacles along the way, and gaining treatment perspectives. Participants experienced challenges when seeking and accessing psychological treatment. However, it was found that psychological treatment can be helpful. These helpful experiences were not without both practical and internal challenges. Through their lived experiences, participants gained treatment perspectives. Such unique perspectives informed their knowledge and understanding of different gambling treatments and ongoing recovery from gambling addiction. These findings hold clinical implications and future recommendations for research. It was recommended to assess treatment accessibility, availability of support, psychological treatment approaches, helpful techniques, and online treatment delivery, including support networks, and recognising the value of lived experience was considered important. Future research should aim to focus on better quality qualitative studies which explore individual experiences of psychological treatment, comparing various gambling treatments, and reasons why individuals may drop out of psychology treatment. Empirical Project The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic led to significant impacts on individuals’ daily lives. Individuals living with a gambling addiction were particularly vulnerable in the pandemic. Psychological treatment guidance is currently under development, and qualitative research exploring such experiences in the context of the pandemic is limited. This study aimed to make sense of individual experiences of psychological treatment for adults living with a gambling addiction in the United Kingdom in the context of the pandemic. The study analysed data using a method called interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eight participants took part, and semi-structured interviews were used. Participants were recruited from the Northern Gambling Service and had received psychological treatment since the pandemic. Qualitative findings included three themes: out of control, taking back control, and a gambling shadow remains. Most participants experienced significant negative challenges in their relationship with gambling during the pandemic. Participants sought psychological treatment, which helped them limit their gambling harms. Therapeutic relationships and family support further supported this. Participants spoke about ongoing vulnerabilities in their gambling recovery. Further gambling harms were risked by continued exposure to gambling advertising and limited wider gambling support available. The findings have implications for healthcare and policy. It is important to screen to see if individuals experienced difficulties with their gambling during the pandemic. This research supported the delivery of flexible psychological treatment. Wider support and further reviews of limiting gambling exposure and gambling harms are needed. Future research should explore the experiences of harder-to-reach participants and different treatment options.

--> Final eThesis - complete (pdf) -->

Embargoed until: 30 January 2025

Please use the button below to request a copy.

Filename: final thesis_Marvin Josh, 200183725.pdf

Request a copy

Embargo Date:

Please use the 'Request a copy' link(s) in the 'Downloads' section above to request this thesis. This will be sent directly to someone who may authorise access. You can contact us about this thesis . If you need to make a general enquiry, please see the Contact us page.

Prevalence of Problem Gambling: A Meta-analysis of Recent Empirical Research (2016–2022)

- Original Paper

- Published: 31 December 2022

- Volume 39 , pages 1027–1057, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Eliana Gabellini 1 ,

- Fabio Lucchini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6092-1907 1 &

- Maria Elena Gattoni 2

2074 Accesses

10 Citations

16 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Gambling is widely considered a socially acceptable form of recreation. However, for a small minority of individuals, it can become both addictive and problematic with severe adverse consequences. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to provide an overview of prevalence studies published between 2016 and the first quarter of 2022 and an updated estimate of problem gambling in the general adult population. A systematic review and a meta-analysis were carried out using academic databases, Internet, and governmental websites. Following this search and utilizing exclusion criteria, 23 studies on adult gambling prevalence were identified, distinguishing between moderate risk/at risk gambling and problem/pathological gambling. This study found a prevalence of moderate risk/at risk gambling to be 2.43% and of problem/pathological gambling to be 1.29% in the adult population. As difficult as it may be to compare studies due to different methodological procedures, cutoffs, and time frames, the present meta-analysis highlights the variations of prevalence across different countries, giving due consideration to the differences between levels of risk and severity. This work intends to provide a starting point for policymakers and academics to fill the gaps on gambling research—more specifically in some countries where the lack of research in this field is evident—and to study the effectiveness of policies implemented to mitigate gambling harm.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Pornography Consumption in People of Different Age Groups: an Analysis Based on Gender, Contents, and Consequences

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD

Data availability.

Not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Allami, Y., Hodgins, D. C., Young, M., Brunelle, N., Currie, S., Dufour, M., Flores-Pajot, M., & Nadeau, L. (2021). A meta-analysis of problem gambling risk factors in the general adult population. Addiction, 116 (11), 2968–2977. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15449

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

Assanangkornchai, S., McNeil, E. B., Tantirangsee, N., Kittirattanapaiboon, P., Thai National Mental Health Survey Team. (2016). Gambling disorders, gambling type preferences, and psychiatric comorbidity among the Thai general population: Results of the 2013 National Mental Health Survey. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5 (3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.066

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22 , 153–160.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Barbaranelli, C., Vecchione, M., Fida, R., & Podio-Guidugli, S. (2013). Estimating the prevalence of adult problem gambling in Italy with SOGS and PGSI. Journal of Gambling Issues, 28 , 1–24. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2013.28.3

Article Google Scholar

Bijker, R., Booth, N., Merkouris, S. S., Dowling, N. A., & Rodda, S. N. (2022). Global prevalence of help-seeking for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15952

Bilevicius, E., Edgerton, J. D., Sanscartier, M. D., Jiang, D., & Keough, M. T. (2020). Examining gambling activity subtypes over time in a large sample of young adults. Addiction Research and Theory, 28 (4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2019.1647177

Brunborg, G. S., Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Molde, H., & Pallesen, S. (2016). Problem gambling and the five-factor model of personality: A large population-based study: Personality and gambling problems. Addiction, 111 (8), 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13388

Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bates, R., Sayle, M., & Ewart, H. (2018). Isle of man gambling survey 2017: Prevalence, methods, attitudes . Publich Health Institute.

Google Scholar

Calado, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000–2015). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5 (4), 592–613. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.073

Chóliz, M., Marcos, M., & Lázaro-Mateo, J. (2021). The risk of online gambling: A study of gambling disorder prevalence rates in Spain. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19 (2), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00067-4

Cochran, W. G. (1950). The comparison of percentages in matched samples. Biometrika, 37 (3/4), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/2332378

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Colasante, E., Gori, M., Bastiani, L., Siciliano, V., Giordani, P., Grassi, M., & Molinaro, S. (2013). An assessment of the psychometric properties of Italian version of CPGI. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29 (4), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9331-z

Cosgrave, J. (2022). Gambling ain’t what it used to be: The instrumentalization of gambling and late modern culture. Critical Gambling Studies, 3 (1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs81

Dowling, N. A., Youssef, G. J., Jackson, A. C., Pennay, D. W., Francis, K. L., Pennay, A., & Lubman, D. I. (2016). National estimates of Australian gambling prevalence: Findings from a dual-frame omnibus survey: Australian dual-frame gambling survey. Addiction, 111 (3), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13176

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., & Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 51 , 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.008

Dunne, S., Flynn, C., & Sholdis, J. (2017). 2016 Northern Ireland gambling prevalence survey . Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

Economou, M., Souliotis, K., Malliori, M., Peppou, L. E., Kontoangelos, K., Lazaratou, H., Anagnostopoulos, D., Golna, C., Dimitriadis, G., Papadimitriou, G., & Papageorgiou, C. (2019). Problem gambling in Greece: Prevalence and risk factors during the financial crisis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35 (4), 1193–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09843-2

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report . Ottawa Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Gambling Commission. (2018). Participation in gambling and rates of problem gambling—Scotland 2017 . Gambling Commission.

Gambling Commission. (2019). Gambling behaviour in Wales: Findings from the welsh problem gambling survey 2018 . NHS Digital.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36 (5), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491884

Harrison, G. W., Jessen, L. J., Lau, M. I., & Ross, D. (2018). Disordered gambling prevalence: Methodological innovations in a general Danish population survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34 (1), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9707-1

Hodgins, D. C., & El-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95 (5), 777–789. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95577713.x

Hunter, J. P., Saratzis, A., Sutton, A. J., Boucher, R. H., Sayers, R. D., & Bown, M. J. (2014). In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67 (8), 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003

Johansson, A., Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., Odlaug, B. L., & Götestam, K. G. (2009). Risk factors for problematic gambling: A critical literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25 (1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-008-9088-6

Lesieur, H., & Blume, S. (1987). The South Oaks gambling screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144 , 1184–1188. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184

Massatti, R. R., Starr, S., Frohnapfel-Hasson, S., & Martt, N. (2017). A baseline study of past-year problem gambling prevalence among Ohioans. Journal of Gambling Issues . https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2016.34.3

Merkouris, S., Greenwood, C., Manning, V., Oakes, J., Rodda, S., Lubman, D., & Dowling, N. (2020). Enhancing the utility of the problem gambling severity index in clinical settings: Identifying refined categories within the problem gambling category. Addictive Behaviors, 103 , 106257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106257

Minutillo, A., Mastrobattista, L., Pichini, S., Pacifici, R., Genetti, B., Vian, P., Andreotti, A., & Mortali, C. (2021). Gambling prevalence in Italy: Main findings on epidemiological study in the Italian population aged 18 and over. Minerva Forensic Medicine . https://doi.org/10.23736/S2784-8922.21.01805-7

Mongan, D., Millar, S. R., Doyle, A., Chakraborty, S., & Galvin, B. (2022). Gambling in the Republic of Ireland results from the 2019–20 National Drug and Alcohol Survey . Health Research Board.

Mori, T., & Goto, R. (2020). Prevalence of problem gambling among Japanese adults. International Gambling Studies . https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1713852

Neal, P., Del-fabbro, P. H., & O’Neill, M. (2005). Problem gambling and harm towards a national definition. Final report . Gambling Research Australia.

Nelson, S. E., Gebauer, L., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2009). Gambling problem symptom patterns and stability across individual and timeframe. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23 (3), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016053

Park, K. H., & Losch, M. E. (2019). A prevalence of gambling attitudes and behaviors: A 2018 survey of adult Iowans . Iowa Department of Public Health Protecting and Improving the Health of Iowans.

Petry, N. M., & O’Brien, C. P. (2013). Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction, 108 (7), 1186–1187. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12162

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2002). Pathological gambling. Clinical Psychology Review, 22 (7), 1009–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00101-0

Sagoe, D., Griffiths, M. D., Erevik, E. K., Høyland, T., Leino, T., Lande, I. A., Sigurdsson, M. E., & Pallesen, S. (2021). Internet-based treatment of gambling problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10 (3), 546–565. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00062

Schellinck, T., Schrans, T., Schellinck, H., & Bliemel, M. (2015). Instrument development for the focal adult gambling screen (FLAGS-EGM): A measurement of risk and problem gambling associated with electronic gambling machines. Journal of Gambling Issues, 30 , 174. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2015.30.8

Shaffer, H. J., Hall, M. N., & Vander Bilt, J. (1999). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: A research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 89 (9), 1369–1376.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stevens, M. (2017). 2015 Northern territory gambling prevalence and wellbeing survey report . Berlin: Northern Territory Government.

Suurvali, H., Hodgins, D., Toneatto, T., & Cunningham, J. (2008). Treatment seeking among Ontario problem gamblers: Results of a population survey. Psychiatric Services, 59 (11), 1343–1346. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1343

Suvarnapathaki, S. (2021). Meta-analysis of prevalence studies using R. International Journal of Scientific Research, 10 (8), 74–77. https://doi.org/10.36106/ijsr

Costes, J.-M., Richard, J.-B., Eroukmanoff, V., Le Nézet, O., & Philippon, A. (2020). Les Francais et les jeux d’argent et de hasard Résultats du Baromètre de Santé publique France 2019 . Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies.

Gerstein, D., Murphy, S., Toce, M., Volberg, R., Harwood, H., Tucker, A., Christiansen, E., Cummings, W., & Sinclair, S. (1999). Gambling impact and behavior study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission .

Gisle, L., & Drieskens, S. (2019). Pratique des jeux de hasard et d’argent . Bruxelles, Belgique: Sciensano. Numéro de rapport: D/2019/14.440/69. HIS 2018.

Meyer, G., Hayer, T., & Griffiths, M. (Eds.). (2009). Problem gambling in Europe: Challenges, prevention, and interventions . Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1

NHS Digital. (2019). Health Survey for England 2018—Supplementary analysis on gambling .

Nower, L., Volberg, R., & Caler, K. R. (2017). The prevalence of online and land‐based gambling in New Jersey . Report to the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement.

RStudio Team. (2022). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R . Boston: RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/

Salonen, A., Hagfors, H., Lind, K., & Jukka, K. (2020). Gambling and problem gambling—Finnish Gambling 2019 . Statistical Report THL.

Tracy, J. K., Maranda, L., & Scheele, C. (2018). Statewide gambling prevalence in Maryland: 2017 . https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/36127

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends [Technical Report] . Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. https://opus.uleth.ca/handle/10133/3068

Woods, A., Sproston, K., Brook, K., Delfabbro, P., & O’Neil, M. (2019). Gambling prevalence in South Australia (2018): Final report (South Australia) [Report] . Department of Human Services (SA). https://apo.org.au/node/237946

Download references

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Specific Prevention Unit, Agency for Health Protection of Milan, Milan, Italy

Eliana Gabellini & Fabio Lucchini

Epidemiology Unit, Agency for Health Protection of Milan, Milan, Italy

Maria Elena Gattoni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Although this article is the result of a common reflection among the authors, Introduction and Discussion are attributable to FL, Methods and Conclusion are attributable to MEG, Results are attributable to EG.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fabio Lucchini .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

No ethical approval was needed because data from previous published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators were retrieved and analyzed.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

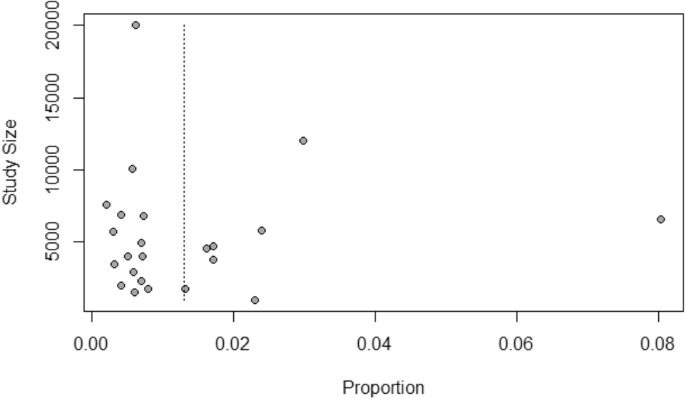

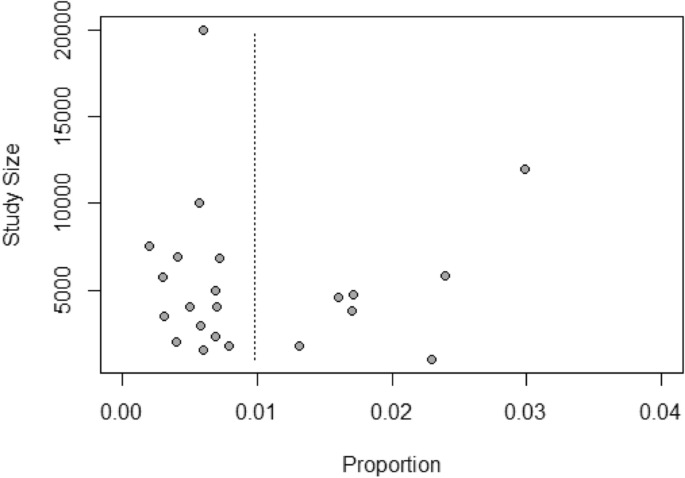

Funnel Plots

To assess publication bias, funnel plots were created for the prevalence estimates. As Hunter et al. ( 2014 ) recommended for meta-analyses of proportions, sample size (study size) was employed as measure of accuracy on the y-axis.

Funnel plots suggest a certain asymmetry, mainly due to the consistent heterogeneity characterizing the studies, both for cultural, socio-economic issues related to each national/territorial reality, and for reasons related to the different types of sampling, different methods of administration and screening instruments used (Figs. 6 , 7 and 8 ).

Funnel plot—estimates of problem/pathological gambling

Funnel plot—estimates of problem/pathological gambling without the Mori and Goto study (Japan, 2020 )

Funnel plot—estimates of moderate/at risk gambling

Meta-regression and Subgroup Analyses

A series of subgroup analyses using a random effects model were performed to investigate possible factors explaining the variability in meta-analytic estimates. First, a meta-regression was conducted to test the overall effect of the following moderators on the mean effect size:

origin (European vs. non-European)

screening instrument (PGSI/CPGI vs other instruments

interview method (telephone interview—CATI or other types; online survey; face-to-face survey—CAPI or other types).

The results of this technique are reported in the table below.

- Bold parts are the statistically significant data according to the meta-regression

Regarding problem/pathological gambling, the meta-regression did not yield a significant association for the Origin ( p = 0.5028) and for the Method ( p = 0.1601; 0.3696). Concerning moderate risk/at-risk gambling, meta-regression showed no significant association for Origin ( p = 0.3470) and Measure ( p = 0.2930).

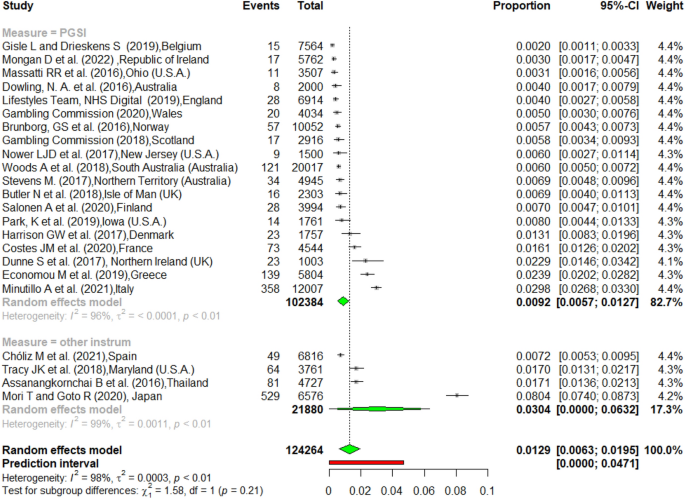

Below are the analyses for the categories that have yielded a significant association according to the meta-regression: the subgroup analysis by screening instrument for problem/pathological gambling (Fig. 9 ) and the subgroup analysis by interview method for moderate risk/at-risk gambling (Fig. 10 ).

Subgroup analysis for screening instrument (problem/pathological gambling)

The subgroup analysis by screening instrument provides strong evidence of variation. The pooled estimate derived from the PGSI (0.92%; 95% CI 0.57; 1.27) turns out to be significantly lower compared to that of studies employing other screening tools (DSM-IV, SOGS, NODS) (3.04%; 95% CI 0.00; 6.32). This difference can be mainly due to the very high estimate obtained in the study conducted in Japan. There were high levels of between-study heterogeneity in each of these subgroups (I 2 Measure = PGSI: 96.1% and I 2 Measure = other instruments: 99.3%).

Subgroup analysis by methods (moderate risk/at risk gambling )

The subgroup analysis by interview method involves three subgroups: telephone interview (CATI or other types), online survey and face-to-face survey (CAPI or other types). Substantial variations are observed depending on the interview method. In particular, the pooled prevalence of the studies involving face-to-face interview is of a considerably lower magnitude (1.53%; 95% CI 0.40–2.66) compared with the other two interview modes. Studies using online surveys have a value almost twice as high (3.20%; 95% CI 1.45–4.95) compared to face-to-face interviews, while studies using telephone interviews have a high estimate in a middle position between the two modes (2.78%, 95% CI 1.90–3.67). High levels of heterogeneity between studies were also found in each of these subgroups (I 2 Method = Telephone interview 96.6%; I 2 Method = Online survey: 97.8%; I 2 Method = Face-to-face survey: 98.5%).

Below are the analyses for subgroups whose effect was not significant according to the meta-regression (Figs. 11 , 12 and 13 ).

Subgroup analysis by origin—problem/pathological gambling

First, when looking at the world region dichotomy (e.g. European/Non-European prevalence study variable), a higher pooled estimate of the non-European countries (1.64%, 95% CI 0.06; 3.23) is noted compared to the lower result of the European studies (1.06%, 95% CI 0.60; 1.52) (Fig. 11 ).

Subgroup analysis by method (problem/pathological gambling)

There is also statistically significant variation on the interview modes. Specifically, the pooled estimate of the studies that used online survey as the method of collection stands out (2.65, 95% CI 0.00; 6.17) (Fig. 12 ).

Subgroup analysis by origin (moderate risk gambling/at risk gambling)

There was no evidence of systematic variation in the prevalence estimates by origin. An analysis for the moderator method was not performed because in the case of moderate risk and at risk gambling estimates, only two studies employing instruments other than PGSI are available.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gabellini, E., Lucchini, F. & Gattoni, M.E. Prevalence of Problem Gambling: A Meta-analysis of Recent Empirical Research (2016–2022). J Gambl Stud 39 , 1027–1057 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10180-0

Download citation

Accepted : 26 November 2022

Published : 31 December 2022

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10180-0

Most Popular

10 days ago

How to Write a Hook

12 days ago

QuillBot VS Turnitin

13 days ago

Neuroscience vs Psychology

How to cite a letter.

11 days ago

How to Cite Yourself

Gambling essay sample, example.

Addictions have always been a problem to humanity. Many people tend to explain them as weaknesses, sicknesses, or on the contrary, something not worth attention. People tend to think that addictions are mostly connected to substance consumption; everyone is aware of alcohol or drug addiction, for example. Recently, there have also been talks about Internet addiction, video game addiction, sexual addiction, selfie addiction, and so on. Although they pose a serious threat to one’s mental and physical wellbeing as well, rather often they are not taken as seriously as substance abuse. Among them is also gambling addiction, which can ruin lives, and can be difficult to detect and treat.

So, what exactly is gambling addiction, and why is it considered to be so dangerous? Generally speaking, gambling addiction is a compulsive act of gambling. In other words, occasional gambling is not an addiction; systematic, frequent, and harmful gambling is. Compulsive gambling occurs regardless of a person’s financial status, family’s attitude, or work-related problems; a gambling addict will feel the urge to gamble even if he/she is already bankrupt, divorced, and fired—entirely for the thrill of the act of gambling itself. According to the American National Council on Problem Gambling, only in the United States, there are over two million people who meet the criteria of pathological gambling (meaning full-scale addiction), and about five more million whose gambling habits can be described as “problem gambling” ( LiveStrong.com ).

So, there is “healthy” gambling (meaning a gambling person does it for fun, has full control over this activity, and never harms themselves or other people through gambling, usually stopping when a money loss limit is reached, or earlier), and there is compulsive gambling; the latter possesses a number of attributes which allow to diagnose it rather accurately. These attributes are: constantly thinking about gambling, or about where to find more money to gamble (including theft and fraud); asking other people for money to continue gambling; gambling in an attempt to recover lost money; similarly to substance addiction, a pathological gambler needs the increasing amounts of money to feel the same thrill; gambling mostly is done to cope with difficult feelings such as anxiety, guilt, depression, or to get distracted from existing problems (including the gambling problem as well); lying to one’s family members about the scales of one’s gambling, or about the fact of gambling itself; losing precious relationships, jobs, reputations, and so on because of gambling ( MayoClinic ).

As it can be seen, gambling possesses attributes rather typical for any kind of addiction, so the reasons standing behind it may also resemble those causing other forms of addictive behavior. In particular, gambling may help a person escape from feelings of depression and anxiety; a gambler may dream of winning a significant sum of money, thus instantly increasing their own self-esteem, reputation, financial status, and achieving the sensation of accomplishing something important in life. Escaping from mundane reality may also be the subconscious purpose of a gambler; shiny casinos, loud arcades, being surrounded by people who occasionally actually win money—all this can create an illusion of welfare, luxury, and belonging to an elite society. Or, as it is in human nature to look for excitement (meaning thrilling or pleasant emotions and “the taste of life” they cause), gambling is often seen as a source of such emotions. Anticipating a jackpot, a gambler’s body produces large amounts of hormones responsible for pleasure and thrill (dopamine and adrenaline, for instance) causing a natural “high” not too much different from the one caused by substances. Besides, western society tolerates gambling much more than other forms of addiction, such as alcoholism or drug abuse. In fact, gambling is often seen as something thrilling but not dangerous, and mass media and advertising agencies only contribute to this image, producing pictures of a fashionable and stylish life connected to gambling; besides, many young people get introduced to gambling at a rather early age—for example, by playing cards or bingo with their parents; these family activities may look rather innocent, but it is important to remember they may also help a young person develop addiction at some point ( HealthyPlace ). If possible, it is better for parents to spend time with their children in some other ways.

Gambling is a form of addiction no different from substance abuse. It is a huge problem for the western world—just in the United States, there are roughly seven million people with varying degrees of pathological gambling behavior. Possessing a number of symptoms similar to less tolerated forms of addiction such as drug abuse, gambling is still seen as a relatively harmless activity. Mass media portrays gambling as an element of luxury, and many people having personal problems and trying to escape from them visit casinos, attempting to run away from their mundane lives. American society would benefit from gambling being treated as a form of behavior that can cause harm to both gamblers and their family members and friends, as it is already happens with alcoholism or drug addiction.

Works Cited

- Bergeson, Boyd. “What Causes Gambling Addiction?” LIVESTRONG.COM. Leaf Group, 17 Aug. 2015. Web. 24 Apr. 2017.

- “Compulsive Gambling.” Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 22 Oct. 2016. Web. 24 Apr. 2017.

- Gluck, Samantha. “Psychology of Gambling: Why Do People Gamble?” HealthyPlace. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2017.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Analytical Essay Examples and Samples 2024

Nov 28 2023

Hirschi’s Social Bond Theory

Nov 27 2023

Another Brick In The Wall Meaning

Themes in The Crucible

Related writing guides, writing an analysis essay.

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- Erasmus School of Economics

- Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication

- Erasmus School of Law

- Erasmus School of Philosophy

- Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences

- Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management

- International Institute of Social Studies

- Rotterdam School of Management

- Tinbergen Institute

- Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies

- RSM Parttime Master Bedrijfskunde

- Erasmus University Library

- Thesis Repository.

- Erasmus School of Economics /

- Business Economics /

- Bachelor Thesis

- Search: Search

Vorm, F.W. van der

The causes of gambling addiction: an examination of what characteristics and ways of thinking drive gambling issues

Publication.

Add Content

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

‘Getting addicted to it and losing a lot of money… it’s just like a hole.’ A grounded theory model of how social determinants shape adolescents’ choices to not gamble

- Nerilee Hing 1 ,

- Hannah Thorne 2 ,

- Lisa Lole 1 ,

- Kerry Sproston 3 ,

- Nicole Hodge 3 &

- Matthew Rockloff 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1270 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

313 Accesses

Metrics details

Gambling abstinence when underage lowers the risk of harmful gambling in later life. However, little research has examined why many young people refrain from gambling, even though this knowledge can inform protective strategies and lower risk factors to reduce underage gambling and subsequent harm. This study draws on the lived experience of adolescent non-gamblers to explore how social determinants while growing up have shaped their reasons and choices to not gamble.

Fourteen Australian non-gamblers, aged 12–17 years, participated in an in-depth individual interview (4 girls, 3 boys) or online community (4 girls, 3 boys). Questions in each condition differed, but both explored participants’ gambling-related experiences while growing up, including exposure, attitudes and behaviours of parents and peers, advertising, simulated gambling and motivations for not gambling. The analysis used adaptive grounded theory methods.

The grounded theory model identifies several reasons for not gambling, including not being interested, being below the legal gambling age, discouragement from parent and peers, concern about gambling addiction and harm, not wanting to risk money on a low chance of winning, and moral objections. These reasons were underpinned by several social determinants, including individual, parental, peer and environmental factors that can interact to deter young people from underage gambling. Key protective factors were parental role modelling and guidance, friendship groups who avoided gambling, critical thinking, rational gambling beliefs, financial literacy and having other hobbies and interests.

Conclusions

Choices to not gamble emanated from multiple layers of influence, implying that multi-layered interventions, aligned with a public health response, are needed to deter underage gambling. At the environmental level, better age-gating for monetary and simulated gambling, countering cultural pressures, and less exposure to promotional gambling messages, may assist young people to resist these influences. Interventions that support parents to provide appropriate role modelling and guidance for their children are also important. Youth education could include cautionary tales from people with lived experience of gambling harm, and education to increase young people’s financial literacy, ability to recognise marketing tactics, awareness of the risks and harms of gambling, and how to resist peer and other normalising gambling influences.

Peer Review reports

Most research into gambling amongst adolescents has focused on the prevalence and predictors of harmful gambling [ 1 , 2 ]. Since early engagement in gambling is a risk factor for gambling problems in adulthood [ 3 , 4 ], studies have also examined the reasons that adolescents participate in gambling when underage [ 5 , 6 ]. However, little attention has focused on understanding why many young people refrain from gambling. Approximately 50–70% of adolescents report no past-year gambling [ 7 , 8 ], even though underage access to many gambling products is reportedly easy [ 9 ]. Understanding why these adolescents choose to refrain from gambling can inform protective strategies against underage gambling and subsequent gambling harm.

Numerous theoretical models identify the key types of influences on youth developmental outcomes [ 10 , 11 ], health outcomes [ 12 , 13 ], and the development of gambling behaviours and subsequent harms [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. These models all recognise that these behaviours and outcomes are influenced by complex interactions between multiple factors (e.g., individual attributes; physical, cultural and social circumstances) and at multiple levels (e.g., individuals, relationships, organisations, society). This recognition that multiple and multi-level factors impact on health behaviours and outcomes can inform an understanding of how various influences interact to shape young people’s decisions to refrain from gambling.

Young people’s self-reported reasons for not gambling

To our knowledge, only two survey studies have examined reasons for not gambling amongst young people. Rash and McGrath [ 18 ] conducted a content analysis of responses to an open-ended survey question asked of 196 Canadian undergraduates (mean age = 21.2 years, SD = 3.7) who reported no past-year gambling. They were asked to ‘think about what motivates you to NOT gamble and briefly list the top three reasons in rank order.’ The most common motive was financial reasons and risk aversion (33.1%), followed by disinterest/other priorities (21.1%), personal and religious objections (12.2%), addiction concerns (9.6%), influence of others’ values (9.1%), awareness of the odds (8.9%), lack of access, opportunity or skill (2.1%) and emotional distress (1.7%).

Another study focused specifically on young people under the legal gambling age [ 7 ]. It surveyed a weighted sample of 2559 students aged 11–16 years in England, Scotland and Wales. Those who reported no past-year gambling were asked: ‘You said that you have never gambled or never spent your own money on gambling. Why is that?’ and were provided with multiple response options. The most endorsed reasons were lack of interest in gambling (39%), because it is illegal or they thought they were too young (37%), not wanting to play with real money/rather play with free games (25%), not being allowed to gamble by their parents (24%), and because it may lead to future problems (22%). Less common reasons were expecting to lose more than they will win (21%), because they ‘don’t agree with gambling and/or it is not right’ (21%), thinking they were unlikely to win money (19%), not knowing enough about gambling games (11%) and religious objections (10%). Girls tended to report less interest in gambling, while boys were more likely to cite that gambling may lead to future problems. Younger participants were more likely to endorse that they did not agree with gambling and that their parents do not allow them to gamble. These findings align with observations that adolescent non-gamblers tend to be female and younger, compared to adolescent gamblers [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Social determinants of adolescent non-gambling

Social determinants of health are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes [ 22 ]. Several social determinants may directly and indirectly shape the reasons for not gambling that many young people report, although this linkage has not previously been examined. Nonetheless, studies that compare non-gamblers to gamblers amongst adolescents provide some insights into social factors associated with non-gambling.

In a survey of 506 students from six schools in South Australia (mean age = 16.5, SD = 0.77 years), non-gamblers rated gambling as more unprofitable, compared to gamblers, and were significantly less likely to have family or friends who approved of gambling or who gambled a lot [ 23 ]. In another Australian study of students aged 12–17 years in Queensland and Victoria ( N = 6377), those who had not gambled in the past month were significantly more likely than past-month gamblers to report having less spending money available, lower alcohol consumption, less exposure to gambling advertisements, and fewer peers or family members who had recently gambled [ 20 ]. Also in Australia, unique predictors of past-year non-gambling identified in two non-probability samples of youth aged 12–17 years ( N = 826, N = 843) were parental disapproval of gambling, not gambling with their parents while growing up, not having friends who gambled, and avoidance of simulated gambling [ 8 ].

In New Zealand, Rossen [ 21 ] surveyed students from 12 secondary schools ( N = 2005; mean age = 15.2 years, SD = 1.45). Compared to gamblers, non-gamblers tended to have lower rates of internet and computer game usage, alcohol usage, and recall of seeing gambling advertising. They were also less likely to have family members or friends who gambled or had a gambling problem. Further, less liberal attitudes to gambling, lower perceived ease of access to gambling, and lower perceived role of skill in gambling were associated with non-gambling status. Non-gambling was also associated with being required to contribute to household chores, higher importance of spiritual beliefs, higher parental attachment, trust and communication, and lower maternal, paternal and peer alienation.

In the US, a survey of 15,865 eighth-graders in Oregon (mean age = 13.7 years, SD = 0.50) focused on health behaviours, including gambling during the previous three months [ 24 ]. Good personal safety habits, non-involvement in antisocial behaviour, and strong personal health beliefs predicted non-gambling in both girls and boys. Amongst girls, non-gamblers were also more likely than gamblers to report less screen time on school nights, no tobacco use, and to speak English at home. Amongst boys, living in neighbourhoods with strong social control and non-Hispanic ethnicity also predicted non-gambling. Also in North America, a study of students aged 13–19 years in Canada ( N = 10,035) found that non-gamblers were less likely to engage in simulated gambling, compared to those who gambled [ 19 ].

In summary, two studies have examined qualitative self-reported reasons given by young people for not gambling, while quantitative research identifies social factors that differ between adolescent non-gamblers and gamblers. However, a detailed exploration linking reasons for not gambling with social factors is lacking. This study therefore aims to draw on the lived experience of adolescent non-gamblers to explore how social determinants can shape their reasons and choices to not gamble as they grow up.

We use a grounded theory methodology in this study, which is appropriate when a research topic lacks a theoretical foundation. This approach allows us to expand upon previous reasons that adolescents report for not gambling to also identify underlying social determinants and processes. The study was approved by our institutional ethics committee (number 23,445).

Recruitment

Participants were adolescents aged 12–17 years who lived in NSW and provided their own and their legal guardian’s informed consent. Due to ethical concerns surrounding anonymity, confidentiality, and minimising legal risk to underage participants, detailed information on participants was not collected. Sampling ensured reasonably even representation from younger (12–14 years) and older (15–17 years) ages, boys and girls, as well as regional and metropolitan locations (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Parents/guardians in the recruitment agency’s database were the initial point of contact to recruit the adolescents to participate in either an interview or online community. The funding agency requested these options be offered, based on the rationale that the strengths and weaknesses of each method would complement each other. The parents were contacted via email with an information sheet and invited to ask their adolescent to complete a brief online recruitment screener, which included questions confirming no past-year adolescent gambling, basic demographics, and confirmation of their and their parent’s consent to participate in the study. Eligible candidates were fully informed of what was expected of them, that their participation was entirely voluntary, and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Data collection

Seven participants opted for an interview. The interviews, each lasting about 45 min, explored each participant’s gambling-related experiences during their childhood and adolescence. Participants were asked about their exposure to gambling, attitudes to and participation in gambling while growing up, factors that facilitated or hindered any gambling, motivations for not currently gambling, the impacts of gambling on their lives, their family and social environments, their experiences with simulated gambling, and protective factors. Supplement A contains the full list of questions. Participants were compensated with an AU$60 GiftPay voucher.

Seven additional participants participated in an online community. The online community was convened over seven days, using the Visions Live platform which resembles a social media platform. Participants were asked to participate for about one hour each day in activities and discussions designed to capture their gambling-related experiences while growing up. Nine topics were covered: (1) gambling behaviours and attitudes; (2) parental and family gambling attitudes and behaviours; (3) peer influence; (4) gaming and simulated gambling; (5) their ‘gambling journey’, including key milestones and influences over time; (6) gambling advertising; (7) gambling harms; (8) protective strategies; and (9) future gambling intentions. Supplement B contains the full list of questions. All participants used anonymous avatars. Tiered compensation was based on the number of days they participated, with a maximum of AU$140 in GiftPay vouchers available.

Individual interviews enabled an in-depth oral and narrative account of developmental influences on each participant’s choice to not gamble, while the online communities enabled participants to consider their answers over a more extended time period, to share information on sensitive topics in an anonymous way, and to discuss the topics with the other participants. While the format of questions was adapted to suit the conversational vs. written format of these activities, all were designed to address the same research aims so the two datasets were combined for analysis.

An adaptive grounded theory method was used which combines inductive and deductive analysis [ 25 ]. We used inductive methods to initially openly code and analyse emergent findings from the data, which were also informed by the literature review on sources of influence on young people’s gambling (parents, peers, marketing, etc.). After data familiarisation, we used the constant comparative method to code phrases, sentences and paragraphs in the data to identify relevant features, refine the codes as the analysis progressed, and group and collapse similar codes into broader themes. For example, codes related to ‘parents not gambling,’ ‘parents talking about gambling risks and harm,’ and ‘parental restrictions’ were grouped into a broader theme of ‘parental modelling, rules and guidance shape gambling attitudes and behaviours.’ Deductive consolidation of themes into multiple levels of influence was informed by a public health, socio-ecological systems approach [ 12 , 13 ] to understand the complex multifaceted nature of factors that contribute to adolescent gambling beliefs, behaviours and attitudes. This process allowed us to identify meaningful patterns in the data. While there were some differences in wording and phrasing of codes between the researchers at the preliminary, inductive stages of data analysis, there were no conflicts when consolidating and coding themes in later stages of the analysis.

Trustworthiness of the research was enhanced by collecting data from participants with lived experience, using open-ended questions, and allowing participants to have control over the experiences they shared. Multiple researchers reviewed each analysis draft to ensure confirmability. Participants’ quotes increase authenticity. These are tagged by gender (male, female), age group in years (12–14, 15–17), and data collection method (IDI = interviews, OLC = online community).

Eight themes emerged from the analysis that were grouped into four socio-ecological levels (Fig. 1 ). Environmental influences that shaped reasons for not gambling included age restrictions on gambling. Peer influences comprised having friendship groups with little interest in gambling. Parental influences entailed parental modelling, rules and guidance. Individual factors included having other interests and having little interest in sport, financial literacy and financial priorities, fear of addiction and harmful consequences, reasoned perceptions about gambling and critical evaluations of advertising, and caution about simulated gambling. These influences underpinned several reasons for not gambling articulated by the participants (Fig. 1 ).

Social determinants of reasons for not gambling amongst adolescents

Age restrictions are seen as an unequivocal barrier to gambling

In Australia, it is illegal for people under 18 years to gamble on commercial gambling products. Nearly all participants were quick to note that being under the legal gambling age was the most obvious deterrent to them gambling. They appeared to accept these age restrictions as an unequivocal barrier, based on an implicit trust that the rules exist for a reason: ‘I always… thought that it’s a grown-up thing’ (#1, male, 15–17, IDI). No participants indicated any interest in circumventing age requirements for gambling, even though this was said to be easy:

[Young people] probably could easily get a fake licence or ID, could probably influence an adult or an adult wants to let them into this… [and] some places don’t have the best security in the front entrances, so someone could probably sneak in if they looked a bit older. (#8, male, 12–14, OLC)

Participating only in age-appropriate activities was also an expectation set out by their parents. These young people appeared eager to meet their parents’ expectations and to not break any rules. Accepting that gambling when underage was forbidden was said to lower their interest in gambling.

I don’t gamble because I don’t find it interesting and it is illegal for someone my age, my parents would not want me to gamble. (#13, female, 15–17, OLC) I’ve always been told to not go anywhere near it. I mean I’m also underage so not allowed to, but then it’s also like I’ve always been told that it’s bad and that you could lose a lot of money. (#4, female, 15–17, IDI.)

Parental modelling, rules and guidance shape gambling attitudes and behaviours

In the current study, parental influence was said to be critically important in shaping the participants’ gambling attitudes and behaviours from early childhood onwards. Most participants reported that their parents did not gamble or did so only occasionally. This limited parental gambling was usually associated with having negative opinions of gambling which, in turn, were said to shape the young person’s attitudes and behaviours.

My parents always despised gambling as my uncle wasted all his money on it and went off the rails. So that early instilling of the bad rep of gambling has stuck with me. (#10, male, 15–17, OLC) I think that my parents don’t gamble, and don’t have anything good to say about gambling, has influenced me a lot… Parents think it’s a waste of money as much more likely to lose money than win it… it makes me feel like it’s all fake and everyone who goes there comes back home with empty pockets. (#12, female, 12–14, OLC)

Because the participants tended to recognise how their parents’ opinions, advice and behaviour have influenced their own aversion to gambling, some were highly critical of parents who gambled in front of children.

It sucks that people think it’s ok to do this kind of stuff around kids, who are largely influenced by their parents, as they will view them as heroic figures, and will adopt these bad traits onto themselves. (#8, male, 12–14, OLC)

As well as protecting their child from socialisation into gambling through the family, educating them on the risks and harms of gambling was another protective parental influence that participants recalled. They typically recounted that early childhood messages from their parents focused mostly on conveying a general disapproval of gambling, and then progressed to more detailed conversations about gambling risks and harms as the participants became older. They particularly remembered the cautionary tales that their parents related, usually during the participants’ early adolescence when their exposure to gambling was increasing. These conversations were often reactive, in response to an external cue such as a gambling advertisement. Participants recalled being especially responsive to stories based on real experiences.

My mum is a police officer, so I’ve heard… stories about the dark sides of gambling… and getting addicted to it… [Gambling] hasn’t really interested me that much because I know what can go wrong. (#1, male, 15–17, IDI)

Some participants reported that witnessing harm from gambling made an impression by raising their awareness of the likelihood of gambling losses and the risk of addiction.

I know now that… you’re more likely to lose lots of money than win lots of money… when I saw my Pop losing heaps of money, I’m like, ‘Oh, it’s not all win, win, win.’ (#2, male, 12–14, IDI). Going to Las Vegas, seeing people betting and all the machines… It made me realise how addicted people are. (#12, female, 12–14, OLC) On a school excursion, we had a guest speaker who had experienced gambling… he had taken money out of his workplace… then gambled the money… then he was trying to get it back through gambling… his experience of how that really forced him to experience a lot of hardship with his family and trying to find support with that. So, I’d seen, through those kind of things, the ways that it can negatively impact on people and the way that you can lose control. (#5, female, 15–17, IDI)

Most participants reported parental monitoring and control over their gambling, online gaming and simulated gambling. One participant described how his parents had a ‘no gambling’ rule, and another reported that his mother monitored and limited his spending on in-game items when playing video games. Some parents were also aware of simulated gambling elements in online games and were cautious about their child’s engagement.

It looked like a pokies machine. That’s why my mum was concerned with me playing it because you pulled down the lever and the thing spun, and then if you collected three of those things then you got a reward. (#4, female, 15–17, IDI)

Protective influences from friendship groups with little interest in gambling

As young people enter and advance through their teenage years, peer influences on gambling tend to become more significant. However, while the participants recognised that peer influences could encourage gambling, most reported that their friends did not gamble or that gambling was not part of the interests, activities or conversations in their friendship groups: ‘Me and my friends never really bring up the topic “gambling” and I have never seen them talk about it to anyone else’ (#11, female, 12–14, OLC).

One participant explained that the moral values associated with her cultural background were her main deterrent. Having friends with a similar background also limited her interest in gambling because this friendship group shared other hobbies.

My friends come from backgrounds where gambling is highly discouraged and they have carried that out through our friendship, we don’t talk about gambling often and so I tend not to associate with it, this has also discouraged me from gambling. We have other interests and activities to do that don’t involve gambling. (#13, female, 15–17, OLC) Peers were also said to influence the participants’ attitudes to gambling through vicarious experiences of gambling losses. For example, this participant reported that seeing or hearing about friends losing increased his awareness of the negative consequences that gambling could have: ‘I saw my friends… if they lost then they’d be all like upset… so I started to see like the downsides of it as well’ (#1, male, 15–17, IDI). Some older participants noticed increased peer involvement in gambling in their later teens, alongside more opportunities to gamble. However, the attendant risks appeared to be offset by other environmental, parental and peer protective factors.

Having other interests, and little interest in sport

Many participants discussed how having other hobbies and activities left them with little time or interest in gambling. These activities included dancing, painting, drawing, music and skateboarding, which they might do alone or with friends: ‘My activities outside of school keep me occupied and less likely to take an interest in gambling’ (#12, female, 12–14, OLC). Alternatively, some participants commented that gambling could distract young people from more productive interests and pursuits. Participants recognised that having gambling-related interests might override an adolescent’s interest in other activities, including schoolwork: ‘People start gambling from a young age and set this as their future job [instead] of… focusing on school and their studies and setting a good career’ (#11, female, 12–14, OLC).

Further, an interest in following professional sport was said to expose young people to gambling influences and act as a ‘gateway’ to an interest in gambling. Some participants commented that their own lack of interest in sport helped to protect them from frequent exposure to betting influences and activities. They did not see the point in betting on sporting competitions that they had no interest in. Other participants did report an interest in sport but resisted its gambling influences, possibly due to other protective factors such as parental influences.

Financial literacy and financial priorities

Numerous participants referred to gambling as ‘a waste of money’, a view most said had been conveyed by their parents. These adolescents did not see the point of engaging in chance activities where they risked losing their money: ‘Why waste your money on something that won’t necessarily work?’ (#14, female, 15–17, OLC). Several explained they understood there was a greater chance of losing than winning.

If I were to work hard every day, I would not want to waste it on a low chance of winning more and a high chance of losing most of my money… The closest thing I have done to gambling is just carnival stuff. (#8, male, 12–14, OLC)

These participants typically reported they had better things to spend their money on, both now and in the future. Older participants, in particular, appeared to have a well-developed sense of financial literacy, financial responsibility and future orientation. They believed that their appreciation of the value of money had been instilled by their parents. The following participant’s views on money demonstrate her high level of financial responsibility and her financial priorities that discouraged her from gambling.

I’m very like cautious about where my money goes… I don’t want to lose a lot of money because I like to save all of my money… I very much like to keep my money, because I love to travel and at the end of school, I want to travel around the world a bit. And then I also need to save up for uni and everything, because I don’t want to have a lot of debts… I very much like to know where my money is… Because money is very valuable, especially now when houses cost like tonnes of money, and you need to save up to buy a lot of things, and like inflation is making things more expensive. (#4, female, 15–17, IDI)

Fear of addiction and harmful consequences