Quantitative study designs: Case Studies/ Case Report/ Case Series

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

- Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

Case Study / Case Report / Case Series

Some famous examples of case studies are John Martin Marlow’s case study on Phineas Gage (the man who had a railway spike through his head) and Sigmund Freud’s case studies, Little Hans and The Rat Man. Case studies are widely used in psychology to provide insight into unusual conditions.

A case study, also known as a case report, is an in depth or intensive study of a single individual or specific group, while a case series is a grouping of similar case studies / case reports together.

A case study / case report can be used in the following instances:

- where there is atypical or abnormal behaviour or development

- an unexplained outcome to treatment

- an emerging disease or condition

The stages of a Case Study / Case Report / Case Series

Which clinical questions does Case Study / Case Report / Case Series best answer?

Emerging conditions, adverse reactions to treatments, atypical / abnormal behaviour, new programs or methods of treatment – all of these can be answered with case studies /case reports / case series. They are generally descriptive studies based on qualitative data e.g. observations, interviews, questionnaires, diaries, personal notes or clinical notes.

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using Case Studies/ Case Reports and Case Series ?

What are the pitfalls to look for.

One pitfall that has occurred in some case studies is where two common conditions/treatments have been linked together with no comprehensive data backing up the conclusion. A hypothetical example could be where high rates of the common cold were associated with suicide when the cohort also suffered from depression.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with critically appraising Case studies / Case reports / Case series there are some tools / checklists you can use.

JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series

JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports

Real World Examples

Some Psychology case study / case report / case series examples

Capp, G. (2015). Our community, our schools : A case study of program design for school-based mental health services. Children & Schools, 37(4), 241–248. A pilot program to improve school based mental health services was instigated in one elementary school and one middle / high school. The case study followed the program from development through to implementation, documenting each step of the process.

Cowdrey, F. A. & Walz, L. (2015). Exposure therapy for fear of spiders in an adult with learning disabilities: A case report. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(1), 75–82. One person was studied who had completed a pre- intervention and post- intervention questionnaire. From the results of this data the exposure therapy intervention was found to be effective in reducing the phobia. This case report highlighted a therapy that could be used to assist people with learning disabilities who also suffered from phobias.

Li, H. X., He, L., Zhang, C. C., Eisinger, R., Pan, Y. X., Wang, T., . . . Li, D. Y. (2019). Deep brain stimulation in post‐traumatic dystonia: A case series study. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 1-8. Five patients were included in the case series, all with the same condition. They all received deep brain stimulation but not in the same area of the brain. Baseline and last follow up visit were assessed with the same rating scale.

References and Further Reading

Greenhalgh, T. (2014). How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Heale, R. & Twycross, A. (2018). What is a case study? Evidence Based Nursing, 21(1), 7-8.

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. (2019). Study design 101: case report. Retrieved from https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/casereports.cfm

Hoffmann T., Bennett S., Mar C. D. (2017). Evidence-based practice across the health professions. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

Robinson, O. C., & McAdams, D. P. (2015). Four functional roles for case studies in emerging adulthood research. Emerging Adulthood, 3(6), 413-420.

- << Previous: Cross-Sectional Studies

- Next: Study Designs Home >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 11:37 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Study Design 101: Case Report

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

- Case Reports

An article that describes and interprets an individual case, often written in the form of a detailed story. Case reports often describe:

- Unique cases that cannot be explained by known diseases or syndromes

- Cases that show an important variation of a disease or condition

- Cases that show unexpected events that may yield new or useful information

- Cases in which one patient has two or more unexpected diseases or disorders

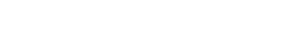

Case reports are considered the lowest level of evidence, but they are also the first line of evidence, because they are where new issues and ideas emerge. This is why they form the base of our pyramid. A good case report will be clear about the importance of the observation being reported.

If multiple case reports show something similar, the next step might be a case-control study to determine if there is a relationship between the relevant variables.

- Can help in the identification of new trends or diseases

- Can help detect new drug side effects and potential uses (adverse or beneficial)

- Educational - a way of sharing lessons learned

- Identifies rare manifestations of a disease

Disadvantages

- Cases may not be generalizable

- Not based on systematic studies

- Causes or associations may have other explanations

- Can be seen as emphasizing the bizarre or focusing on misleading elements

Design pitfalls to look out for

The patient should be described in detail, allowing others to identify patients with similar characteristics.

Does the case report provide information about the patient's age, sex, ethnicity, race, employment status, social situation, medical history, diagnosis, prognosis, previous treatments, past and current diagnostic test results, medications, psychological tests, clinical and functional assessments, and current intervention?

Case reports should include carefully recorded, unbiased observations.

Does the case report include measurements and/or recorded observations of the case? Does it show a bias?

Case reports should explore and infer, not confirm, deduce, or prove. They cannot demonstrate causality or argue for the adoption of a new treatment approach.

Does the case report present a hypothesis that can be confirmed by another type of study?

Fictitious Example

A physician treated a young and otherwise healthy patient who came to her office reporting numbness all over her body. The physician could not determine any reason for this numbness and had never seen anything like it. After taking an extensive history the physician discovered that the patient had recently been to the beach for a vacation and had used a very new type of spray sunscreen. The patient had stored the sunscreen in her cooler at the beach because she liked the feel of the cool spray in the hot sun. The physician suspected that the spray sunscreen had undergone a chemical reaction from the coldness which caused the numbness. She also suspected that because this is a new type of sunscreen other physicians may soon be seeing patients with this numbness.

The physician wrote up a case report describing how the numbness presented, how and why she concluded it was the spray sunscreen, and how she treated the patient. Later, when other doctors began seeing patients with this numbness, they found this case report helpful as a starting point in treating their patients.

Real-life Examples

Hymes KB. Cheung T. Greene JB. Prose NS. Marcus A. Ballard H. William DC. Laubenstein LJ. (1981). Kaposi's sarcoma in homosexual men-a report of eight cases. Lancet. 2 (8247),598-600.

This case report was published by eight physicians in New York city who had unexpectedly seen eight male patients with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). Prior to this, KS was very rare in the U.S. and occurred primarily in the lower extremities of older patients. These cases were decades younger, had generalized KS, and a much lower rate of survival. This was before the discovery of HIV or the use of the term AIDS and this case report was one of the first published items about AIDS patients.

Wu, E. B., & Sung, J. J. Y. (2003). Haemorrhagic-fever-like changes and normal chest radiograph in a doctor with SARS. Lancet, 361 (9368), 1520-1521.

This case report is written by the patient, a physician who contracted SARS, and his colleague who treated him, during the 2003 outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong. They describe how the disease progressed in Dr. Wu and based on Dr. Wu's case, advised that a chest CT showed hidden pneumonic changes and facilitate a rapid diagnosis.

Related Terms

Case Series

A report about a small group of similar cases.

Preplanned Case-Observation

A case in which symptoms are elicited to study disease mechanisms. (Ex. Having a patient sleep in a lab to do brain imaging for a sleep disorder).

Now test yourself!

1. Case studies are not considered evidence-based even though the authors have studied the case in great depth.

2. When are Case reports most useful?

When you encounter common cases and need more information When new symptoms or outcomes are unidentified When developing practice guidelines When the population being studied is very large

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- << Previous: Welcome to Study Design 101

- Next: Case Control Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.

- Phineas Gage – One of the most famous neuropsychology case studies analyzes personality changes in railroad worker Phineas Gage after an 1848 brain injury involving a tamping iron piercing his skull.

Clinical Case Studies

- Studying the effectiveness of psychotherapy approaches with an individual patient

- Assessing and treating mental illnesses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD

- Neuropsychological cases investigating brain injuries or disorders

Child Psychology Case Studies

- Studying psychological development from birth through adolescence

- Cases of learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, ADHD

- Effects of trauma, abuse, deprivation on development

Types of Case Studies

- Explanatory case studies : Used to explore causation in order to find underlying principles. Helpful for doing qualitative analysis to explain presumed causal links.

- Exploratory case studies : Used to explore situations where an intervention being evaluated has no clear set of outcomes. It helps define questions and hypotheses for future research.

- Descriptive case studies : Describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. It is helpful for illustrating certain topics within an evaluation.

- Multiple-case studies : Used to explore differences between cases and replicate findings across cases. Helpful for comparing and contrasting specific cases.

- Intrinsic : Used to gain a better understanding of a particular case. Helpful for capturing the complexity of a single case.

- Collective : Used to explore a general phenomenon using multiple case studies. Helpful for jointly studying a group of cases in order to inquire into the phenomenon.

Where Do You Find Data for a Case Study?

There are several places to find data for a case study. The key is to gather data from multiple sources to get a complete picture of the case and corroborate facts or findings through triangulation of evidence. Most of this information is likely qualitative (i.e., verbal description rather than measurement), but the psychologist might also collect numerical data.

1. Primary sources

- Interviews – Interviewing key people related to the case to get their perspectives and insights. The interview is an extremely effective procedure for obtaining information about an individual, and it may be used to collect comments from the person’s friends, parents, employer, workmates, and others who have a good knowledge of the person, as well as to obtain facts from the person him or herself.

- Observations – Observing behaviors, interactions, processes, etc., related to the case as they unfold in real-time.

- Documents & Records – Reviewing private documents, diaries, public records, correspondence, meeting minutes, etc., relevant to the case.

2. Secondary sources

- News/Media – News coverage of events related to the case study.

- Academic articles – Journal articles, dissertations etc. that discuss the case.

- Government reports – Official data and records related to the case context.

- Books/films – Books, documentaries or films discussing the case.

3. Archival records

Searching historical archives, museum collections and databases to find relevant documents, visual/audio records related to the case history and context.

Public archives like newspapers, organizational records, photographic collections could all include potentially relevant pieces of information to shed light on attitudes, cultural perspectives, common practices and historical contexts related to psychology.

4. Organizational records

Organizational records offer the advantage of often having large datasets collected over time that can reveal or confirm psychological insights.

Of course, privacy and ethical concerns regarding confidential data must be navigated carefully.

However, with proper protocols, organizational records can provide invaluable context and empirical depth to qualitative case studies exploring the intersection of psychology and organizations.

- Organizational/industrial psychology research : Organizational records like employee surveys, turnover/retention data, policies, incident reports etc. may provide insight into topics like job satisfaction, workplace culture and dynamics, leadership issues, employee behaviors etc.

- Clinical psychology : Therapists/hospitals may grant access to anonymized medical records to study aspects like assessments, diagnoses, treatment plans etc. This could shed light on clinical practices.

- School psychology : Studies could utilize anonymized student records like test scores, grades, disciplinary issues, and counseling referrals to study child development, learning barriers, effectiveness of support programs, and more.

How do I Write a Case Study in Psychology?

Follow specified case study guidelines provided by a journal or your psychology tutor. General components of clinical case studies include: background, symptoms, assessments, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Interpreting the information means the researcher decides what to include or leave out. A good case study should always clarify which information is the factual description and which is an inference or the researcher’s opinion.

1. Introduction

- Provide background on the case context and why it is of interest, presenting background information like demographics, relevant history, and presenting problem.

- Compare briefly to similar published cases if applicable. Clearly state the focus/importance of the case.

2. Case Presentation

- Describe the presenting problem in detail, including symptoms, duration,and impact on daily life.

- Include client demographics like age and gender, information about social relationships, and mental health history.

- Describe all physical, emotional, and/or sensory symptoms reported by the client.

- Use patient quotes to describe the initial complaint verbatim. Follow with full-sentence summaries of relevant history details gathered, including key components that led to a working diagnosis.

- Summarize clinical exam results, namely orthopedic/neurological tests, imaging, lab tests, etc. Note actual results rather than subjective conclusions. Provide images if clearly reproducible/anonymized.

- Clearly state the working diagnosis or clinical impression before transitioning to management.

3. Management and Outcome

- Indicate the total duration of care and number of treatments given over what timeframe. Use specific names/descriptions for any therapies/interventions applied.

- Present the results of the intervention,including any quantitative or qualitative data collected.

- For outcomes, utilize visual analog scales for pain, medication usage logs, etc., if possible. Include patient self-reports of improvement/worsening of symptoms. Note the reason for discharge/end of care.

4. Discussion

- Analyze the case, exploring contributing factors, limitations of the study, and connections to existing research.

- Analyze the effectiveness of the intervention,considering factors like participant adherence, limitations of the study, and potential alternative explanations for the results.

- Identify any questions raised in the case analysis and relate insights to established theories and current research if applicable. Avoid definitive claims about physiological explanations.

- Offer clinical implications, and suggest future research directions.

5. Additional Items

- Thank specific assistants for writing support only. No patient acknowledgments.

- References should directly support any key claims or quotes included.

- Use tables/figures/images only if substantially informative. Include permissions and legends/explanatory notes.

- Provides detailed (rich qualitative) information.

- Provides insight for further research.

- Permitting investigation of otherwise impractical (or unethical) situations.

Case studies allow a researcher to investigate a topic in far more detail than might be possible if they were trying to deal with a large number of research participants (nomothetic approach) with the aim of ‘averaging’.

Because of their in-depth, multi-sided approach, case studies often shed light on aspects of human thinking and behavior that would be unethical or impractical to study in other ways.

Research that only looks into the measurable aspects of human behavior is not likely to give us insights into the subjective dimension of experience, which is important to psychoanalytic and humanistic psychologists.

Case studies are often used in exploratory research. They can help us generate new ideas (that might be tested by other methods). They are an important way of illustrating theories and can help show how different aspects of a person’s life are related to each other.

The method is, therefore, important for psychologists who adopt a holistic point of view (i.e., humanistic psychologists ).

Limitations

- Lacking scientific rigor and providing little basis for generalization of results to the wider population.

- Researchers’ own subjective feelings may influence the case study (researcher bias).

- Difficult to replicate.

- Time-consuming and expensive.

- The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources.

Because a case study deals with only one person/event/group, we can never be sure if the case study investigated is representative of the wider body of “similar” instances. This means the conclusions drawn from a particular case may not be transferable to other settings.

Because case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative (i.e., descriptive) data , a lot depends on the psychologist’s interpretation of the information she has acquired.

This means that there is a lot of scope for Anna O , and it could be that the subjective opinions of the psychologist intrude in the assessment of what the data means.

For example, Freud has been criticized for producing case studies in which the information was sometimes distorted to fit particular behavioral theories (e.g., Little Hans ).

This is also true of Money’s interpretation of the Bruce/Brenda case study (Diamond, 1997) when he ignored evidence that went against his theory.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria . Standard Edition 2: London.

Curtiss, S. (1981). Genie: The case of a modern wild child .

Diamond, M., & Sigmundson, K. (1997). Sex Reassignment at Birth: Long-term Review and Clinical Implications. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 151(3), 298-304

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Freud, S. (1909b). Bemerkungen über einen Fall von Zwangsneurose (Der “Rattenmann”). Jb. psychoanal. psychopathol. Forsch ., I, p. 357-421; GW, VII, p. 379-463; Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis, SE , 10: 151-318.

Harlow J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39 , 389–393.

Harlow, J. M. (1868). Recovery from the Passage of an Iron Bar through the Head . Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. 2 (3), 327-347.

Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl : The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Money, J., & Tucker, P. (1975). Sexual signatures: On being a man or a woman.

Further Information

- Case Study Approach

- Case Study Method

- Enhancing the Quality of Case Studies in Health Services Research

- “We do things together” A case study of “couplehood” in dementia

- Using mixed methods for evaluating an integrative approach to cancer care: a case study

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Case Study vs. Research

What's the difference.

Case study and research are both methods used in academic and professional settings to gather information and gain insights. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or situation, aiming to understand the unique characteristics and dynamics involved. It often involves qualitative data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. On the other hand, research is a systematic investigation conducted to generate new knowledge or validate existing theories. It typically involves a larger sample size and employs quantitative data collection methods such as surveys, experiments, or statistical analysis. While case studies provide detailed and context-specific information, research aims to generalize findings to a broader population.

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to conducting studies and gathering information, researchers have various methods at their disposal. Two commonly used approaches are case study and research. While both methods aim to explore and understand a particular subject, they differ in their approach, scope, and the type of data they collect. In this article, we will delve into the attributes of case study and research, highlighting their similarities and differences.

A case study is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, event, or phenomenon. It involves a detailed examination of a particular case to gain insights into its unique characteristics, context, and dynamics. Case studies often employ multiple sources of data, such as interviews, observations, and documents, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation.

One of the key attributes of a case study is its focus on a specific case, which allows researchers to explore complex and nuanced aspects of the subject. By examining a single case in detail, researchers can uncover rich and detailed information that may not be possible with broader research methods. Case studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unique phenomena, as they provide an opportunity to deeply analyze and understand them.

Furthermore, case studies often employ qualitative research methods, emphasizing the collection of non-numerical data. This qualitative approach allows researchers to capture the subjective experiences, perspectives, and motivations of the individuals or groups involved in the case. By using open-ended interviews and observations, researchers can gather rich and detailed data that provides a holistic view of the subject.

However, it is important to note that case studies have limitations. Due to their focus on a specific case, the findings may not be easily generalized to a larger population or context. The small sample size and unique characteristics of the case may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the subjective nature of qualitative data collection in case studies may introduce bias or interpretation challenges.

Research, on the other hand, is a systematic investigation aimed at discovering new knowledge or validating existing theories. It involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. Research can be conducted using various methods, including surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis, depending on the nature of the study.

One of the primary attributes of research is its emphasis on generating generalizable knowledge. By using representative samples and statistical techniques, researchers aim to draw conclusions that can be applied to a larger population or context. This allows for the identification of patterns, trends, and relationships that can inform theories, policies, or practices.

Research often employs quantitative methods, focusing on the collection of numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. Surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis allow researchers to measure variables, establish correlations, and test hypotheses. This objective approach provides a level of objectivity and replicability that is crucial for scientific inquiry.

However, research also has its limitations. The focus on generalizability may sometimes sacrifice the depth and richness of understanding that case studies offer. The reliance on quantitative data may overlook important qualitative aspects of the subject, such as individual experiences or contextual factors. Additionally, the controlled nature of research settings may not fully capture the complexity and dynamics of real-world situations.

Similarities

Despite their differences, case studies and research share some common attributes. Both methods aim to gather information and generate knowledge about a particular subject. They require careful planning, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Both case studies and research contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

Furthermore, both case studies and research can be used in various disciplines, including social sciences, psychology, business, and healthcare. They provide valuable insights and contribute to evidence-based decision-making. Whether it is understanding the impact of a new treatment, exploring consumer behavior, or investigating social phenomena, both case studies and research play a crucial role in expanding our understanding of the world.

In conclusion, case study and research are two distinct yet valuable approaches to studying and understanding a subject. Case studies offer an in-depth analysis of a specific case, providing rich and detailed information that may not be possible with broader research methods. On the other hand, research aims to generate generalizable knowledge by using representative samples and quantitative methods. While case studies emphasize qualitative data collection, research focuses on quantitative analysis. Both methods have their strengths and limitations, and their choice depends on the research objectives, scope, and context. By utilizing the appropriate method, researchers can gain valuable insights and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

PH717 Module 1B - Descriptive Tools

Descriptive epidemiology & descriptive statistics.

- Page:

- 1

- | 2

- | 3

- | 4

- | 5

- | 6

- | 7

- | 8

- | 9

Case Reports and Case Series

Case reports, case series, test yourself.

Categories of Descriptive Epidemiology

A case report is a detailed description of disease occurrence in a single person. Unusual features of the case may suggest a new hypothesis about the causes or mechanisms of disease.

Example: Acquired Immunodeficiency in an Infant; Possible Transmission by Means of Blood Products

In April 1983 it had not yet been shown that AIDS could be transmitted by blood or blood products. An infant born with Rh incompatibility; required blood products from 18 donors over 8 weeks and subsequently developed unusual recurrent infections with opportunistic agents such as Candida. The infant's T cell count was low, suggesting AIDS. There was no family history of immunodeficiency, but one of the blood donors was found to have died of AIDS. This led the investigators to hypothesize that AIDS could be transmitted by blood transfusion.

Link to article by Ammann AJ et al: Acquired immunodeficiency in an infant: possible transmission by means of blood products. The Lancet 1:956-958, 1983.

A case series is a report on the characteristics of a group of subjects who all have a particular disease or condition. Common features among the group may suggest hypotheses about disease causation. Note that the "series" may be small (as in the example below) or it may be large (hundreds or thousands of "cases"). However, the chief limitation is that there is no comparison group. Consequently, common features may suggest hypotheses, but these need to be tested with some sort of analytical study before an association can be accepted as valid.

Example: Discovery of HIV in the United States

This was an extraordinarily important case series (a detailed description of characteristics of a series of people who all have the same disease) that suggested that this new syndrome was associated with sexual activity in male homosexuals. Alerting the medical establishment and proposing a hypothesis was an important milestone in the AIDS epidemic.

Link to article by Gottlieb MS, et al: Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med 1981;305:1425-1431.

There had been a number of case reports of liver cancers in young women taking oral contraceptives. A study was undertaken by contacting all of the cancer registries collaborating with the American College of Surgeons. The investigators wanted to collect information on as many of these rare liver tumors as possible across the US.

Table - Oral Contraceptive Use Among Women Who Developed Liver Cancer

What conclusions can you draw from these data regarding a possible increased risk of liver cancer in woman taking oral contraceptives? Think about it before you look at the answer.

return to top | previous page | next page

Content ©2020. All Rights Reserved. Date last modified: September 10, 2020. Wayne W. LaMorte, MD, PhD, MPH

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A student guide to writing a case report

- Maeve McAllister 1

BDJ Student volume 30 , pages 12–13 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

26 Accesses

Metrics details

As a student, it can be hard to know where to start when reading or writing a clinical case report either for university or out of special interest in a Journal. I have collated five top tips for writing an insightful and relevant case report.

A case report is a structured report of the clinical process of a patient's diagnostic pathway, including symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment planning (short and long term), clinical outcomes and follow-up. 1 Some of these case reports can sometimes have simple titles, to the more unusual, for example, 'Oral Tuberculosis', 'The escapee wisdom tooth', 'A difficult diagnosis'. They normally begin with the word 'Sir' and follow an introduction from this.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Guidelines To Writing a Clinical Case Report. Heart Views 2017; 18 , 104-105.

British Dental Journal. Case reports. Available online at: www.nature.com/bdj/articles?searchType=journalSearch&sort=PubDate&type=case-report&page=2 (accessed August 17, 2022).

Chate R, Chate C. Achenbach's syndrome. Br Dent J 2021; 231: 147.

Abdulgani A, Muhamad, A-H and Watted N. Dental case report for publication; step by step. J Dent Med Sci 2014; 3 : 94-100.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queen´s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

Maeve McAllister

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maeve McAllister .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McAllister, M. A student guide to writing a case report. BDJ Student 30 , 12–13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Download citation

Published : 30 January 2023

Issue Date : 30 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Case Report vs Case-Control Study: A Simple Explanation

A case report is the description of the clinical story of a single patient, whereas a case-control study compares 2 groups of participants differing in outcome in order to determine if a suspected exposure in their past caused that difference.

Here’s the evidence pyramid showing the level of evidence for different study designs:

Further reading

- Case Report: A Beginner’s Guide with Examples

- Case Report vs Cross-Sectional Study

- Cohort vs Cross-Sectional Study

- How to Identify Different Types of Cohort Studies?

- Matched Pairs Design

- Randomized Block Design

Case Reports Vs Clinical Studies

Uncategorized

This post discusses questions validity if authored by an employee of the reporting company, Roho. This blog will answer these questions regarding clinical studies and clinical evidence:

- What is the difference between a clinical study and a case report?

- Who can observe and document the results of a clinical study?

- What circumstance would beg questioning the validity of a case report?

(Information below was take from the site clinical trials .gov a service of the National Institute of Health)

Definition of case report and clinical study

In medicine, a case report is a detailed report of the symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of an individual patient. Case reports may contain a demographic profile of the patient, but usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence.

The case report is written on one individual patient.

Clinical Study

A research study using human subjects to evaluate biomedical or health-related outcomes. Two types of clinical studies are Interventional Studies (or clinical trials) and Observational Studies . A clinical study involves multiple patients.

Observational Clinical Studies have a qualified investigator.

In an observational study, investigators assess health outcomes in groups of participants according to a research plan or protocol. Participants may receive interventions (which can include medical products such as drugs or devices) or procedures as part of their routine medical care, but participants are not assigned to specific interventions by the investigator (as in a clinical trial).

The Key Responsibilities of a Clinical Study Investigator:

- Be qualified to practice medicine or psychiatry and meet the qualifications specified by applicable national regulatory requirements(s)

- Be qualified by education, training, and experience to assume responsibility for the proper conduct of the study,

- Be familiar with and compliant with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) ICH E6 Guideline and applicable ethical and regulatory requirements prior to commencement of work on the study.

- Provide evidence of his/her qualification using the Abbreviated TransCelerate Curriculum Vitae (CV) form

The internal validity of a medical device case report is questioned if bias is present. One must consider bias in a case report authored by an employee of the company that makes the device described in the report.

These are the facts on clinical studies published on the roho website.

- There are 15 of what roho calls clinical studies on the roho website. Based on the above definitions, these are not clinical studies but rather case reports.

- Of these 15 case reports only one pertains a seat cushion improving a pressure ulcer.

This one single case report is written by Cynthia Fleck, an employee of crown therapeutics which is a division of roho

After selling 1 million cushions over the span of 45 years in business roho has exactly 1 case report which was written by an employee of roho which then begs the question of validity of this report.

Related Posts

Pressure Injury Prevention , SofTech , Uncategorized

Considerations with a standing chair mechanism in fighting pressure sores.

Inspirational people in wheelchairs to follow on social media, get relief & healing from pressure injuries.

Order Your Pressure Relief Wheelchair Cushion Today

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.