Statistics Tutorial

Descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, stat reference, statistics - hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing is a formal way of checking if a hypothesis about a population is true or not.

Hypothesis Testing

A hypothesis is a claim about a population parameter .

A hypothesis test is a formal procedure to check if a hypothesis is true or not.

Examples of claims that can be checked:

The average height of people in Denmark is more than 170 cm.

The share of left handed people in Australia is not 10%.

The average income of dentists is less the average income of lawyers.

The Null and Alternative Hypothesis

Hypothesis testing is based on making two different claims about a population parameter.

The null hypothesis (\(H_{0} \)) and the alternative hypothesis (\(H_{1}\)) are the claims.

The two claims needs to be mutually exclusive , meaning only one of them can be true.

The alternative hypothesis is typically what we are trying to prove.

For example, we want to check the following claim:

"The average height of people in Denmark is more than 170 cm."

In this case, the parameter is the average height of people in Denmark (\(\mu\)).

The null and alternative hypothesis would be:

Null hypothesis : The average height of people in Denmark is 170 cm.

Alternative hypothesis : The average height of people in Denmark is more than 170 cm.

The claims are often expressed with symbols like this:

\(H_{0}\): \(\mu = 170 \: cm \)

\(H_{1}\): \(\mu > 170 \: cm \)

If the data supports the alternative hypothesis, we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis.

If the data does not support the alternative hypothesis, we keep the null hypothesis.

Note: The alternative hypothesis is also referred to as (\(H_{A} \)).

The Significance Level

The significance level (\(\alpha\)) is the uncertainty we accept when rejecting the null hypothesis in the hypothesis test.

The significance level is a percentage probability of accidentally making the wrong conclusion.

Typical significance levels are:

- \(\alpha = 0.1\) (10%)

- \(\alpha = 0.05\) (5%)

- \(\alpha = 0.01\) (1%)

A lower significance level means that the evidence in the data needs to be stronger to reject the null hypothesis.

There is no "correct" significance level - it only states the uncertainty of the conclusion.

Note: A 5% significance level means that when we reject a null hypothesis:

We expect to reject a true null hypothesis 5 out of 100 times.

Advertisement

The Test Statistic

The test statistic is used to decide the outcome of the hypothesis test.

The test statistic is a standardized value calculated from the sample.

Standardization means converting a statistic to a well known probability distribution .

The type of probability distribution depends on the type of test.

Common examples are:

- Standard Normal Distribution (Z): used for Testing Population Proportions

- Student's T-Distribution (T): used for Testing Population Means

Note: You will learn how to calculate the test statistic for each type of test in the following chapters.

The Critical Value and P-Value Approach

There are two main approaches used for hypothesis tests:

- The critical value approach compares the test statistic with the critical value of the significance level.

- The p-value approach compares the p-value of the test statistic and with the significance level.

The Critical Value Approach

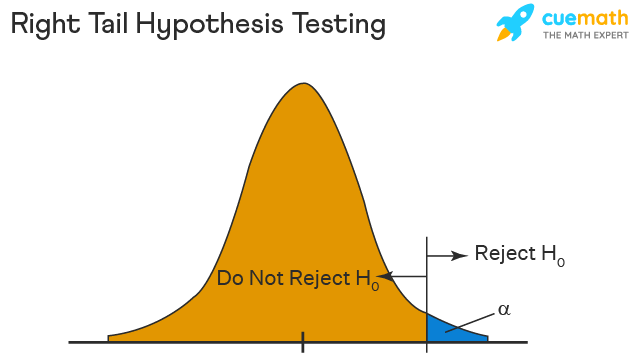

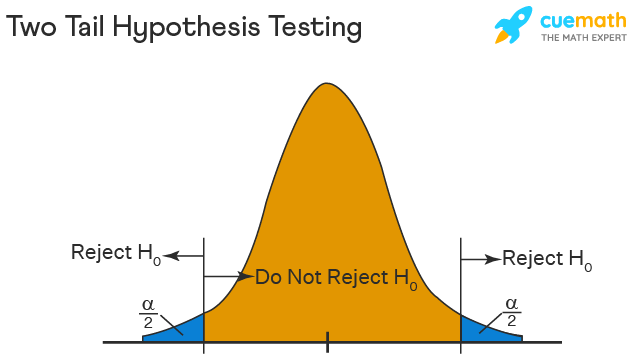

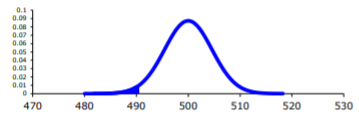

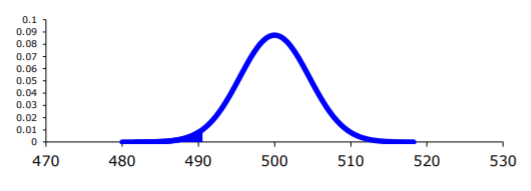

The critical value approach checks if the test statistic is in the rejection region .

The rejection region is an area of probability in the tails of the distribution.

The size of the rejection region is decided by the significance level (\(\alpha\)).

The value that separates the rejection region from the rest is called the critical value .

Here is a graphical illustration:

If the test statistic is inside this rejection region, the null hypothesis is rejected .

For example, if the test statistic is 2.3 and the critical value is 2 for a significance level (\(\alpha = 0.05\)):

We reject the null hypothesis (\(H_{0} \)) at 0.05 significance level (\(\alpha\))

The P-Value Approach

The p-value approach checks if the p-value of the test statistic is smaller than the significance level (\(\alpha\)).

The p-value of the test statistic is the area of probability in the tails of the distribution from the value of the test statistic.

If the p-value is smaller than the significance level, the null hypothesis is rejected .

The p-value directly tells us the lowest significance level where we can reject the null hypothesis.

For example, if the p-value is 0.03:

We reject the null hypothesis (\(H_{0} \)) at a 0.05 significance level (\(\alpha\))

We keep the null hypothesis (\(H_{0}\)) at a 0.01 significance level (\(\alpha\))

Note: The two approaches are only different in how they present the conclusion.

Steps for a Hypothesis Test

The following steps are used for a hypothesis test:

- Check the conditions

- Define the claims

- Decide the significance level

- Calculate the test statistic

One condition is that the sample is randomly selected from the population.

The other conditions depends on what type of parameter you are testing the hypothesis for.

Common parameters to test hypotheses are:

- Proportions (for qualitative data)

- Mean values (for numerical data)

You will learn the steps for both types in the following pages.

COLOR PICKER

Contact Sales

If you want to use W3Schools services as an educational institution, team or enterprise, send us an e-mail: [email protected]

Report Error

If you want to report an error, or if you want to make a suggestion, send us an e-mail: [email protected]

Top Tutorials

Top references, top examples, get certified.

Statistics Made Easy

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter .

For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

A hypothesis test is a formal statistical test we use to reject or fail to reject a statistical hypothesis.

The Two Types of Statistical Hypotheses

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

There are two types of statistical hypotheses:

The null hypothesis , denoted as H 0 , is the hypothesis that the sample data occurs purely from chance.

The alternative hypothesis , denoted as H 1 or H a , is the hypothesis that the sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

Hypothesis Tests

A hypothesis test consists of five steps:

1. State the hypotheses.

State the null and alternative hypotheses. These two hypotheses need to be mutually exclusive, so if one is true then the other must be false.

2. Determine a significance level to use for the hypothesis.

Decide on a significance level. Common choices are .01, .05, and .1.

3. Find the test statistic.

Find the test statistic and the corresponding p-value. Often we are analyzing a population mean or proportion and the general formula to find the test statistic is: (sample statistic – population parameter) / (standard deviation of statistic)

4. Reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Using the test statistic or the p-value, determine if you can reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis based on the significance level.

The p-value tells us the strength of evidence in support of a null hypothesis. If the p-value is less than the significance level, we reject the null hypothesis.

5. Interpret the results.

Interpret the results of the hypothesis test in the context of the question being asked.

The Two Types of Decision Errors

There are two types of decision errors that one can make when doing a hypothesis test:

Type I error: You reject the null hypothesis when it is actually true. The probability of committing a Type I error is equal to the significance level, often called alpha , and denoted as α.

Type II error: You fail to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false. The probability of committing a Type II error is called the Power of the test or Beta , denoted as β.

One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Tests

A statistical hypothesis can be one-tailed or two-tailed.

A one-tailed hypothesis involves making a “greater than” or “less than ” statement.

For example, suppose we assume the mean height of a male in the U.S. is greater than or equal to 70 inches. The null hypothesis would be H0: µ ≥ 70 inches and the alternative hypothesis would be Ha: µ < 70 inches.

A two-tailed hypothesis involves making an “equal to” or “not equal to” statement.

For example, suppose we assume the mean height of a male in the U.S. is equal to 70 inches. The null hypothesis would be H0: µ = 70 inches and the alternative hypothesis would be Ha: µ ≠ 70 inches.

Note: The “equal” sign is always included in the null hypothesis, whether it is =, ≥, or ≤.

Related: What is a Directional Hypothesis?

Types of Hypothesis Tests

There are many different types of hypothesis tests you can perform depending on the type of data you’re working with and the goal of your analysis.

The following tutorials provide an explanation of the most common types of hypothesis tests:

Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test Introduction to the One Proportion Z-Test Introduction to the Two Proportion Z-Test

Featured Posts

Hey there. My name is Zach Bobbitt. I have a Masters of Science degree in Applied Statistics and I’ve worked on machine learning algorithms for professional businesses in both healthcare and retail. I’m passionate about statistics, machine learning, and data visualization and I created Statology to be a resource for both students and teachers alike. My goal with this site is to help you learn statistics through using simple terms, plenty of real-world examples, and helpful illustrations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Statology Community

Sign up to receive Statology's exclusive study resource: 100 practice problems with step-by-step solutions. Plus, get our latest insights, tutorials, and data analysis tips straight to your inbox!

By subscribing you accept Statology's Privacy Policy.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Hypothesis Testing: Uses, Steps & Example

By Jim Frost 4 Comments

What is Hypothesis Testing?

Hypothesis testing in statistics uses sample data to infer the properties of a whole population . These tests determine whether a random sample provides sufficient evidence to conclude an effect or relationship exists in the population. Researchers use them to help separate genuine population-level effects from false effects that random chance can create in samples. These methods are also known as significance testing.

For example, researchers are testing a new medication to see if it lowers blood pressure. They compare a group taking the drug to a control group taking a placebo. If their hypothesis test results are statistically significant, the medication’s effect of lowering blood pressure likely exists in the broader population, not just the sample studied.

Using Hypothesis Tests

A hypothesis test evaluates two mutually exclusive statements about a population to determine which statement the sample data best supports. These two statements are called the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . The following are typical examples:

- Null Hypothesis : The effect does not exist in the population.

- Alternative Hypothesis : The effect does exist in the population.

Hypothesis testing accounts for the inherent uncertainty of using a sample to draw conclusions about a population, which reduces the chances of false discoveries. These procedures determine whether the sample data are sufficiently inconsistent with the null hypothesis that you can reject it. If you can reject the null, your data favor the alternative statement that an effect exists in the population.

Statistical significance in hypothesis testing indicates that an effect you see in sample data also likely exists in the population after accounting for random sampling error , variability, and sample size. Your results are statistically significant when the p-value is less than your significance level or, equivalently, when your confidence interval excludes the null hypothesis value.

Conversely, non-significant results indicate that despite an apparent sample effect, you can’t be sure it exists in the population. It could be chance variation in the sample and not a genuine effect.

Learn more about Failing to Reject the Null .

5 Steps of Significance Testing

Hypothesis testing involves five key steps, each critical to validating a research hypothesis using statistical methods:

- Formulate the Hypotheses : Write your research hypotheses as a null hypothesis (H 0 ) and an alternative hypothesis (H A ).

- Data Collection : Gather data specifically aimed at testing the hypothesis.

- Conduct A Test : Use a suitable statistical test to analyze your data.

- Make a Decision : Based on the statistical test results, decide whether to reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject it.

- Report the Results : Summarize and present the outcomes in your report’s results and discussion sections.

While the specifics of these steps can vary depending on the research context and the data type, the fundamental process of hypothesis testing remains consistent across different studies.

Let’s work through these steps in an example!

Hypothesis Testing Example

Researchers want to determine if a new educational program improves student performance on standardized tests. They randomly assign 30 students to a control group , which follows the standard curriculum, and another 30 students to a treatment group, which participates in the new educational program. After a semester, they compare the test scores of both groups.

Download the CSV data file to perform the hypothesis testing yourself: Hypothesis_Testing .

The researchers write their hypotheses. These statements apply to the population, so they use the mu (μ) symbol for the population mean parameter .

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are equal (μ 1 = μ 2 ).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are unequal (μ 1 ≠ μ 2 ).

Choosing the correct hypothesis test depends on attributes such as data type and number of groups. Because they’re using continuous data and comparing two means, the researchers use a 2-sample t-test .

Here are the results.

The treatment group’s mean is 58.70, compared to the control group’s mean of 48.12. The mean difference is 10.67 points. Use the test’s p-value and significance level to determine whether this difference is likely a product of random fluctuation in the sample or a genuine population effect.

Because the p-value (0.000) is less than the standard significance level of 0.05, the results are statistically significant, and we can reject the null hypothesis. The sample data provides sufficient evidence to conclude that the new program’s effect exists in the population.

Limitations

Hypothesis testing improves your effectiveness in making data-driven decisions. However, it is not 100% accurate because random samples occasionally produce fluky results. Hypothesis tests have two types of errors, both relating to drawing incorrect conclusions.

- Type I error: The test rejects a true null hypothesis—a false positive.

- Type II error: The test fails to reject a false null hypothesis—a false negative.

Learn more about Type I and Type II Errors .

Our exploration of hypothesis testing using a practical example of an educational program reveals its powerful ability to guide decisions based on statistical evidence. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or professional, understanding and applying these procedures can open new doors to discovering insights and making informed decisions. Let this tool empower your analytical endeavors as you navigate through the vast seas of data.

Learn more about the Hypothesis Tests for Various Data Types .

Share this:

Reader Interactions

June 10, 2024 at 10:51 am

Thank you, Jim, for another helpful article; timely too since I have started reading your new book on hypothesis testing and, now that we are at the end of the school year, my district is asking me to perform a number of evaluations on instructional programs. This is where my question/concern comes in. You mention that hypothesis testing is all about testing samples. However, I use all the students in my district when I make these comparisons. Since I am using the entire “population” in my evaluations (I don’t select a sample of third grade students, for example, but I use all 700 third graders), am I somehow misusing the tests? Or can I rest assured that my district’s student population is only a sample of the universal population of students?

June 10, 2024 at 1:50 pm

I hope you are finding the book helpful!

Yes, the purpose of hypothesis testing is to infer the properties of a population while accounting for random sampling error.

In your case, it comes down to how you want to use the results. Who do you want the results to apply to?

If you’re summarizing the sample, looking for trends and patterns, or evaluating those students and don’t plan to apply those results to other students, you don’t need hypothesis testing because there is no sampling error. They are the population and you can just use descriptive statistics. In this case, you’d only need to focus on the practical significance of the effect sizes.

On the other hand, if you want to apply the results from this group to other students, you’ll need hypothesis testing. However, there is the complicating issue of what population your sample of students represent. I’m sure your district has its own unique characteristics, demographics, etc. Your district’s students probably don’t adequately represent a universal population. At the very least, you’d need to recognize any special attributes of your district and how they could bias the results when trying to apply them outside the district. Or they might apply to similar districts in your region.

However, I’d imagine your 3rd graders probably adequately represent future classes of 3rd graders in your district. You need to be alert to changing demographics. At least in the short run I’d imagine they’d be representative of future classes.

Think about how these results will be used. Do they just apply to the students you measured? Then you don’t need hypothesis tests. However, if the results are being used to infer things about other students outside of the sample, you’ll need hypothesis testing along with considering how well your students represent the other students and how they differ.

I hope that helps!

June 10, 2024 at 3:21 pm

Thank you so much, Jim, for the suggestions in terms of what I need to think about and consider! You are always so clear in your explanations!!!!

June 10, 2024 at 3:22 pm

You’re very welcome! Best of luck with your evaluations!

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

S.3 hypothesis testing.

In reviewing hypothesis tests, we start first with the general idea. Then, we keep returning to the basic procedures of hypothesis testing, each time adding a little more detail.

The general idea of hypothesis testing involves:

- Making an initial assumption.

- Collecting evidence (data).

- Based on the available evidence (data), deciding whether to reject or not reject the initial assumption.

Every hypothesis test — regardless of the population parameter involved — requires the above three steps.

Example S.3.1

Is normal body temperature really 98.6 degrees f section .

Consider the population of many, many adults. A researcher hypothesized that the average adult body temperature is lower than the often-advertised 98.6 degrees F. That is, the researcher wants an answer to the question: "Is the average adult body temperature 98.6 degrees? Or is it lower?" To answer his research question, the researcher starts by assuming that the average adult body temperature was 98.6 degrees F.

Then, the researcher went out and tried to find evidence that refutes his initial assumption. In doing so, he selects a random sample of 130 adults. The average body temperature of the 130 sampled adults is 98.25 degrees.

Then, the researcher uses the data he collected to make a decision about his initial assumption. It is either likely or unlikely that the researcher would collect the evidence he did given his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees:

- If it is likely , then the researcher does not reject his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees. There is not enough evidence to do otherwise.

- either the researcher's initial assumption is correct and he experienced a very unusual event;

- or the researcher's initial assumption is incorrect.

In statistics, we generally don't make claims that require us to believe that a very unusual event happened. That is, in the practice of statistics, if the evidence (data) we collected is unlikely in light of the initial assumption, then we reject our initial assumption.

Example S.3.2

Criminal trial analogy section .

One place where you can consistently see the general idea of hypothesis testing in action is in criminal trials held in the United States. Our criminal justice system assumes "the defendant is innocent until proven guilty." That is, our initial assumption is that the defendant is innocent.

In the practice of statistics, we make our initial assumption when we state our two competing hypotheses -- the null hypothesis ( H 0 ) and the alternative hypothesis ( H A ). Here, our hypotheses are:

- H 0 : Defendant is not guilty (innocent)

- H A : Defendant is guilty

In statistics, we always assume the null hypothesis is true . That is, the null hypothesis is always our initial assumption.

The prosecution team then collects evidence — such as finger prints, blood spots, hair samples, carpet fibers, shoe prints, ransom notes, and handwriting samples — with the hopes of finding "sufficient evidence" to make the assumption of innocence refutable.

In statistics, the data are the evidence.

The jury then makes a decision based on the available evidence:

- If the jury finds sufficient evidence — beyond a reasonable doubt — to make the assumption of innocence refutable, the jury rejects the null hypothesis and deems the defendant guilty. We behave as if the defendant is guilty.

- If there is insufficient evidence, then the jury does not reject the null hypothesis . We behave as if the defendant is innocent.

In statistics, we always make one of two decisions. We either "reject the null hypothesis" or we "fail to reject the null hypothesis."

Errors in Hypothesis Testing Section

Did you notice the use of the phrase "behave as if" in the previous discussion? We "behave as if" the defendant is guilty; we do not "prove" that the defendant is guilty. And, we "behave as if" the defendant is innocent; we do not "prove" that the defendant is innocent.

This is a very important distinction! We make our decision based on evidence not on 100% guaranteed proof. Again:

- If we reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the alternative hypothesis is true.

- If we do not reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the null hypothesis is true.

We merely state that there is enough evidence to behave one way or the other. This is always true in statistics! Because of this, whatever the decision, there is always a chance that we made an error .

Let's review the two types of errors that can be made in criminal trials:

| Jury Decision | Truth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Guilty | Guilty | ||

| Not Guilty | OK | ERROR | |

| Guilty | ERROR | OK | |

Table S.3.2 shows how this corresponds to the two types of errors in hypothesis testing.

| Decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | ||

| Do not Reject Null | OK | Type II Error | |

| Reject Null | Type I Error | OK | |

Note that, in statistics, we call the two types of errors by two different names -- one is called a "Type I error," and the other is called a "Type II error." Here are the formal definitions of the two types of errors:

There is always a chance of making one of these errors. But, a good scientific study will minimize the chance of doing so!

Making the Decision Section

Recall that it is either likely or unlikely that we would observe the evidence we did given our initial assumption. If it is likely , we do not reject the null hypothesis. If it is unlikely , then we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. Effectively, then, making the decision reduces to determining "likely" or "unlikely."

In statistics, there are two ways to determine whether the evidence is likely or unlikely given the initial assumption:

- We could take the " critical value approach " (favored in many of the older textbooks).

- Or, we could take the " P -value approach " (what is used most often in research, journal articles, and statistical software).

In the next two sections, we review the procedures behind each of these two approaches. To make our review concrete, let's imagine that μ is the average grade point average of all American students who major in mathematics. We first review the critical value approach for conducting each of the following three hypothesis tests about the population mean $\mu$:

| : = 3 | : > 3 | |

| : = 3 | : < 3 | |

| : = 3 | : ≠ 3 |

In Practice

- We would want to conduct the first hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is more than 3.

- We would want to conduct the second hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is less than 3.

- And, we would want to conduct the third hypothesis test if we were only interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group differs from 3 (without caring whether it is more or less than 3).

Upon completing the review of the critical value approach, we review the P -value approach for conducting each of the above three hypothesis tests about the population mean \(\mu\). The procedures that we review here for both approaches easily extend to hypothesis tests about any other population parameter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Test statistics | Definition, Interpretation, and Examples

Published on July 17, 2020 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

The test statistic is a number calculated from a statistical test of a hypothesis. It shows how closely your observed data match the distribution expected under the null hypothesis of that statistical test.

The test statistic is used to calculate the p value of your results, helping to decide whether to reject your null hypothesis.

Table of contents

What exactly is a test statistic, types of test statistics, interpreting test statistics, reporting test statistics, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about test statistics.

A test statistic describes how closely the distribution of your data matches the distribution predicted under the null hypothesis of the statistical test you are using.

The distribution of data is how often each observation occurs, and can be described by its central tendency and variation around that central tendency. Different statistical tests predict different types of distributions, so it’s important to choose the right statistical test for your hypothesis.

The test statistic summarizes your observed data into a single number using the central tendency, variation, sample size, and number of predictor variables in your statistical model.

Generally, the test statistic is calculated as the pattern in your data (i.e., the correlation between variables or difference between groups) divided by the variance in the data (i.e., the standard deviation ).

- Null hypothesis ( H 0 ): There is no correlation between temperature and flowering date.

- Alternate hypothesis ( H A or H 1 ): There is a correlation between temperature and flowering date.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a summary of the most common test statistics, their hypotheses, and the types of statistical tests that use them.

Different statistical tests will have slightly different ways of calculating these test statistics, but the underlying hypotheses and interpretations of the test statistic stay the same.

| Test statistic | Null and alternative hypotheses | Statistical tests that use it |

|---|---|---|

| value | The means of two groups are equal The means of two groups are not equal | test |

| value | The means of two groups are equal The means of two groups are not equal | test |

| value | The variation among two or more groups is greater than or equal to the variation between the groups The variation among two or more groups is smaller than the variation between the groups | |

| -value | Two samples are independent Two samples are not independent (i.e., they are correlated) | correlation tests |

In practice, you will almost always calculate your test statistic using a statistical program (R, SPSS, Excel, etc.), which will also calculate the p value of the test statistic. However, formulas to calculate these statistics by hand can be found online.

- a regression coefficient of 0.36

- a t value comparing that coefficient to the predicted range of regression coefficients under the null hypothesis of no relationship

The t value of the regression test is 2.36 – this is your test statistic.

For any combination of sample sizes and number of predictor variables, a statistical test will produce a predicted distribution for the test statistic. This shows the most likely range of values that will occur if your data follows the null hypothesis of the statistical test.

The more extreme your test statistic – the further to the edge of the range of predicted test values it is – the less likely it is that your data could have been generated under the null hypothesis of that statistical test.

The agreement between your calculated test statistic and the predicted values is described by the p value . The smaller the p value, the less likely your test statistic is to have occurred under the null hypothesis of the statistical test.

Because the test statistic is generated from your observed data, this ultimately means that the smaller the p value, the less likely it is that your data could have occurred if the null hypothesis was true.

Test statistics can be reported in the results section of your research paper along with the sample size, p value of the test, and any characteristics of your data that will help to put these results into context.

Whether or not you need to report the test statistic depends on the type of test you are reporting.

| Which statistics to report | |

|---|---|

| Correlation and regression tests | or regression coefficient for each predictor variable value for each predictor |

| Tests of difference between groups | value for the test statistic |

By surveying a random subset of 100 trees over 25 years we found a statistically significant ( p < 0.01) positive correlation between temperature and flowering dates ( R 2 = 0.36, SD = 0.057).

In our comparison of mouse diet A and mouse diet B, we found that the lifespan on diet A ( M = 2.1 years; SD = 0.12) was significantly shorter than the lifespan on diet B ( M = 2.6 years; SD = 0.1), with an average difference of 6 months ( t (80) = -12.75; p < 0.01).

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Confidence interval

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

A test statistic is a number calculated by a statistical test . It describes how far your observed data is from the null hypothesis of no relationship between variables or no difference among sample groups.

The test statistic tells you how different two or more groups are from the overall population mean , or how different a linear slope is from the slope predicted by a null hypothesis . Different test statistics are used in different statistical tests.

The formula for the test statistic depends on the statistical test being used.

Generally, the test statistic is calculated as the pattern in your data (i.e. the correlation between variables or difference between groups) divided by the variance in the data (i.e. the standard deviation ).

The test statistic you use will be determined by the statistical test.

You can choose the right statistical test by looking at what type of data you have collected and what type of relationship you want to test.

The test statistic will change based on the number of observations in your data, how variable your observations are, and how strong the underlying patterns in the data are.

For example, if one data set has higher variability while another has lower variability, the first data set will produce a test statistic closer to the null hypothesis , even if the true correlation between two variables is the same in either data set.

Statistical significance is a term used by researchers to state that it is unlikely their observations could have occurred under the null hypothesis of a statistical test . Significance is usually denoted by a p -value , or probability value.

Statistical significance is arbitrary – it depends on the threshold, or alpha value, chosen by the researcher. The most common threshold is p < 0.05, which means that the data is likely to occur less than 5% of the time under the null hypothesis .

When the p -value falls below the chosen alpha value, then we say the result of the test is statistically significant.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Test statistics | Definition, Interpretation, and Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/test-statistic/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, understanding p values | definition and examples, choosing the right statistical test | types & examples, what is effect size and why does it matter (examples), what is your plagiarism score.

Tutorial Playlist

Statistics tutorial, everything you need to know about the probability density function in statistics, the best guide to understand central limit theorem, an in-depth guide to measures of central tendency : mean, median and mode, the ultimate guide to understand conditional probability.

A Comprehensive Look at Percentile in Statistics

The Best Guide to Understand Bayes Theorem

Everything you need to know about the normal distribution, an in-depth explanation of cumulative distribution function, a complete guide to chi-square test, what is hypothesis testing in statistics types and examples, understanding the fundamentals of arithmetic and geometric progression, the definitive guide to understand spearman’s rank correlation, a comprehensive guide to understand mean squared error, all you need to know about the empirical rule in statistics, the complete guide to skewness and kurtosis, a holistic look at bernoulli distribution.

All You Need to Know About Bias in Statistics

A Complete Guide to Get a Grasp of Time Series Analysis

The Key Differences Between Z-Test Vs. T-Test

The Complete Guide to Understand Pearson's Correlation

A complete guide on the types of statistical studies, everything you need to know about poisson distribution, your best guide to understand correlation vs. regression, the most comprehensive guide for beginners on what is correlation, what is hypothesis testing in statistics types and examples.

Lesson 10 of 24 By Avijeet Biswal

Table of Contents

In today’s data-driven world , decisions are based on data all the time. Hypothesis plays a crucial role in that process, whether it may be making business decisions, in the health sector, academia, or in quality improvement. Without hypothesis & hypothesis tests, you risk drawing the wrong conclusions and making bad decisions. In this tutorial, you will look at Hypothesis Testing in Statistics.

The Ultimate Ticket to Top Data Science Job Roles

What Is Hypothesis Testing in Statistics?

Hypothesis Testing is a type of statistical analysis in which you put your assumptions about a population parameter to the test. It is used to estimate the relationship between 2 statistical variables.

Let's discuss few examples of statistical hypothesis from real-life -

- A teacher assumes that 60% of his college's students come from lower-middle-class families.

- A doctor believes that 3D (Diet, Dose, and Discipline) is 90% effective for diabetic patients.

Now that you know about hypothesis testing, look at the two types of hypothesis testing in statistics.

Hypothesis Testing Formula

Z = ( x̅ – μ0 ) / (σ /√n)

- Here, x̅ is the sample mean,

- μ0 is the population mean,

- σ is the standard deviation,

- n is the sample size.

How Hypothesis Testing Works?

An analyst performs hypothesis testing on a statistical sample to present evidence of the plausibility of the null hypothesis. Measurements and analyses are conducted on a random sample of the population to test a theory. Analysts use a random population sample to test two hypotheses: the null and alternative hypotheses.

The null hypothesis is typically an equality hypothesis between population parameters; for example, a null hypothesis may claim that the population means return equals zero. The alternate hypothesis is essentially the inverse of the null hypothesis (e.g., the population means the return is not equal to zero). As a result, they are mutually exclusive, and only one can be correct. One of the two possibilities, however, will always be correct.

Your Dream Career is Just Around The Corner!

Null Hypothesis and Alternate Hypothesis

The Null Hypothesis is the assumption that the event will not occur. A null hypothesis has no bearing on the study's outcome unless it is rejected.

H0 is the symbol for it, and it is pronounced H-naught.

The Alternate Hypothesis is the logical opposite of the null hypothesis. The acceptance of the alternative hypothesis follows the rejection of the null hypothesis. H1 is the symbol for it.

Let's understand this with an example.

A sanitizer manufacturer claims that its product kills 95 percent of germs on average.

To put this company's claim to the test, create a null and alternate hypothesis.

H0 (Null Hypothesis): Average = 95%.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The average is less than 95%.

Another straightforward example to understand this concept is determining whether or not a coin is fair and balanced. The null hypothesis states that the probability of a show of heads is equal to the likelihood of a show of tails. In contrast, the alternate theory states that the probability of a show of heads and tails would be very different.

Become a Data Scientist with Hands-on Training!

Hypothesis Testing Calculation With Examples

Let's consider a hypothesis test for the average height of women in the United States. Suppose our null hypothesis is that the average height is 5'4". We gather a sample of 100 women and determine that their average height is 5'5". The standard deviation of population is 2.

To calculate the z-score, we would use the following formula:

z = ( x̅ – μ0 ) / (σ /√n)

z = (5'5" - 5'4") / (2" / √100)

z = 0.5 / (0.045)

We will reject the null hypothesis as the z-score of 11.11 is very large and conclude that there is evidence to suggest that the average height of women in the US is greater than 5'4".

Steps of Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a statistical method to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample of data to infer that a certain condition is true for the entire population. Here’s a breakdown of the typical steps involved in hypothesis testing:

Formulate Hypotheses

- Null Hypothesis (H0): This hypothesis states that there is no effect or difference, and it is the hypothesis you attempt to reject with your test.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1 or Ha): This hypothesis is what you might believe to be true or hope to prove true. It is usually considered the opposite of the null hypothesis.

Choose the Significance Level (α)

The significance level, often denoted by alpha (α), is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true. Common choices for α are 0.05 (5%), 0.01 (1%), and 0.10 (10%).

Select the Appropriate Test

Choose a statistical test based on the type of data and the hypothesis. Common tests include t-tests, chi-square tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis . The selection depends on data type, distribution, sample size, and whether the hypothesis is one-tailed or two-tailed.

Collect Data

Gather the data that will be analyzed in the test. This data should be representative of the population to infer conclusions accurately.

Calculate the Test Statistic

Based on the collected data and the chosen test, calculate a test statistic that reflects how much the observed data deviates from the null hypothesis.

Determine the p-value

The p-value is the probability of observing test results at least as extreme as the results observed, assuming the null hypothesis is correct. It helps determine the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis.

Make a Decision

Compare the p-value to the chosen significance level:

- If the p-value ≤ α: Reject the null hypothesis, suggesting sufficient evidence in the data supports the alternative hypothesis.

- If the p-value > α: Do not reject the null hypothesis, suggesting insufficient evidence to support the alternative hypothesis.

Report the Results

Present the findings from the hypothesis test, including the test statistic, p-value, and the conclusion about the hypotheses.

Perform Post-hoc Analysis (if necessary)

Depending on the results and the study design, further analysis may be needed to explore the data more deeply or to address multiple comparisons if several hypotheses were tested simultaneously.

Types of Hypothesis Testing

To determine whether a discovery or relationship is statistically significant, hypothesis testing uses a z-test. It usually checks to see if two means are the same (the null hypothesis). Only when the population standard deviation is known and the sample size is 30 data points or more, can a z-test be applied.

A statistical test called a t-test is employed to compare the means of two groups. To determine whether two groups differ or if a procedure or treatment affects the population of interest, it is frequently used in hypothesis testing.

Chi-Square

You utilize a Chi-square test for hypothesis testing concerning whether your data is as predicted. To determine if the expected and observed results are well-fitted, the Chi-square test analyzes the differences between categorical variables from a random sample. The test's fundamental premise is that the observed values in your data should be compared to the predicted values that would be present if the null hypothesis were true.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Intervals

Both confidence intervals and hypothesis tests are inferential techniques that depend on approximating the sample distribution. Data from a sample is used to estimate a population parameter using confidence intervals. Data from a sample is used in hypothesis testing to examine a given hypothesis. We must have a postulated parameter to conduct hypothesis testing.

Bootstrap distributions and randomization distributions are created using comparable simulation techniques. The observed sample statistic is the focal point of a bootstrap distribution, whereas the null hypothesis value is the focal point of a randomization distribution.

A variety of feasible population parameter estimates are included in confidence ranges. In this lesson, we created just two-tailed confidence intervals. There is a direct connection between these two-tail confidence intervals and these two-tail hypothesis tests. The results of a two-tailed hypothesis test and two-tailed confidence intervals typically provide the same results. In other words, a hypothesis test at the 0.05 level will virtually always fail to reject the null hypothesis if the 95% confidence interval contains the predicted value. A hypothesis test at the 0.05 level will nearly certainly reject the null hypothesis if the 95% confidence interval does not include the hypothesized parameter.

Become a Data Scientist through hands-on learning with hackathons, masterclasses, webinars, and Ask-Me-Anything! Start learning now!

Simple and Composite Hypothesis Testing

Depending on the population distribution, you can classify the statistical hypothesis into two types.

Simple Hypothesis: A simple hypothesis specifies an exact value for the parameter.

Composite Hypothesis: A composite hypothesis specifies a range of values.

A company is claiming that their average sales for this quarter are 1000 units. This is an example of a simple hypothesis.

Suppose the company claims that the sales are in the range of 900 to 1000 units. Then this is a case of a composite hypothesis.

One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The One-Tailed test, also called a directional test, considers a critical region of data that would result in the null hypothesis being rejected if the test sample falls into it, inevitably meaning the acceptance of the alternate hypothesis.

In a one-tailed test, the critical distribution area is one-sided, meaning the test sample is either greater or lesser than a specific value.

In two tails, the test sample is checked to be greater or less than a range of values in a Two-Tailed test, implying that the critical distribution area is two-sided.

If the sample falls within this range, the alternate hypothesis will be accepted, and the null hypothesis will be rejected.

Become a Data Scientist With Real-World Experience

Right Tailed Hypothesis Testing

If the larger than (>) sign appears in your hypothesis statement, you are using a right-tailed test, also known as an upper test. Or, to put it another way, the disparity is to the right. For instance, you can contrast the battery life before and after a change in production. Your hypothesis statements can be the following if you want to know if the battery life is longer than the original (let's say 90 hours):

- The null hypothesis is (H0 <= 90) or less change.

- A possibility is that battery life has risen (H1) > 90.

The crucial point in this situation is that the alternate hypothesis (H1), not the null hypothesis, decides whether you get a right-tailed test.

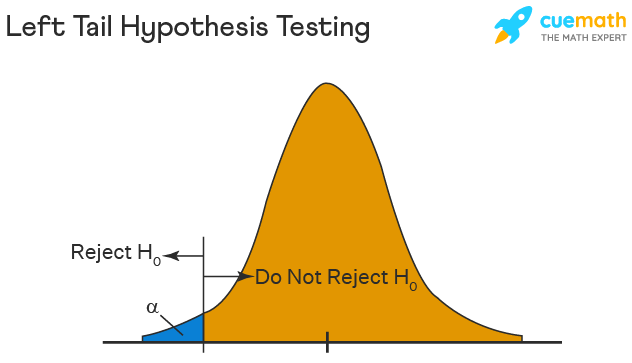

Left Tailed Hypothesis Testing

Alternative hypotheses that assert the true value of a parameter is lower than the null hypothesis are tested with a left-tailed test; they are indicated by the asterisk "<".

Suppose H0: mean = 50 and H1: mean not equal to 50

According to the H1, the mean can be greater than or less than 50. This is an example of a Two-tailed test.

In a similar manner, if H0: mean >=50, then H1: mean <50

Here the mean is less than 50. It is called a One-tailed test.

Type 1 and Type 2 Error

A hypothesis test can result in two types of errors.

Type 1 Error: A Type-I error occurs when sample results reject the null hypothesis despite being true.

Type 2 Error: A Type-II error occurs when the null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false, unlike a Type-I error.

Suppose a teacher evaluates the examination paper to decide whether a student passes or fails.

H0: Student has passed

H1: Student has failed

Type I error will be the teacher failing the student [rejects H0] although the student scored the passing marks [H0 was true].

Type II error will be the case where the teacher passes the student [do not reject H0] although the student did not score the passing marks [H1 is true].

Level of Significance

The alpha value is a criterion for determining whether a test statistic is statistically significant. In a statistical test, Alpha represents an acceptable probability of a Type I error. Because alpha is a probability, it can be anywhere between 0 and 1. In practice, the most commonly used alpha values are 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1, which represent a 1%, 5%, and 10% chance of a Type I error, respectively (i.e. rejecting the null hypothesis when it is in fact correct).

A p-value is a metric that expresses the likelihood that an observed difference could have occurred by chance. As the p-value decreases the statistical significance of the observed difference increases. If the p-value is too low, you reject the null hypothesis.

Here you have taken an example in which you are trying to test whether the new advertising campaign has increased the product's sales. The p-value is the likelihood that the null hypothesis, which states that there is no change in the sales due to the new advertising campaign, is true. If the p-value is .30, then there is a 30% chance that there is no increase or decrease in the product's sales. If the p-value is 0.03, then there is a 3% probability that there is no increase or decrease in the sales value due to the new advertising campaign. As you can see, the lower the p-value, the chances of the alternate hypothesis being true increases, which means that the new advertising campaign causes an increase or decrease in sales.

Our Data Scientist Master's Program covers core topics such as R, Python, Machine Learning, Tableau, Hadoop, and Spark. Get started on your journey today!

Why Is Hypothesis Testing Important in Research Methodology?

Hypothesis testing is crucial in research methodology for several reasons:

- Provides evidence-based conclusions: It allows researchers to make objective conclusions based on empirical data, providing evidence to support or refute their research hypotheses.

- Supports decision-making: It helps make informed decisions, such as accepting or rejecting a new treatment, implementing policy changes, or adopting new practices.

- Adds rigor and validity: It adds scientific rigor to research using statistical methods to analyze data, ensuring that conclusions are based on sound statistical evidence.

- Contributes to the advancement of knowledge: By testing hypotheses, researchers contribute to the growth of knowledge in their respective fields by confirming existing theories or discovering new patterns and relationships.

When Did Hypothesis Testing Begin?

Hypothesis testing as a formalized process began in the early 20th century, primarily through the work of statisticians such as Ronald A. Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, and Egon Pearson. The development of hypothesis testing is closely tied to the evolution of statistical methods during this period.

- Ronald A. Fisher (1920s): Fisher was one of the key figures in developing the foundation for modern statistical science. In the 1920s, he introduced the concept of the null hypothesis in his book "Statistical Methods for Research Workers" (1925). Fisher also developed significance testing to examine the likelihood of observing the collected data if the null hypothesis were true. He introduced p-values to determine the significance of the observed results.

- Neyman-Pearson Framework (1930s): Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson built on Fisher’s work and formalized the process of hypothesis testing even further. In the 1930s, they introduced the concepts of Type I and Type II errors and developed a decision-making framework widely used in hypothesis testing today. Their approach emphasized the balance between these errors and introduced the concepts of the power of a test and the alternative hypothesis.

The dialogue between Fisher's and Neyman-Pearson's approaches shaped the methods and philosophy of statistical hypothesis testing used today. Fisher emphasized the evidential interpretation of the p-value. At the same time, Neyman and Pearson advocated for a decision-theoretical approach in which hypotheses are either accepted or rejected based on pre-determined significance levels and power considerations.

The application and methodology of hypothesis testing have since become a cornerstone of statistical analysis across various scientific disciplines, marking a significant statistical development.

Limitations of Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing has some limitations that researchers should be aware of:

- It cannot prove or establish the truth: Hypothesis testing provides evidence to support or reject a hypothesis, but it cannot confirm the absolute truth of the research question.

- Results are sample-specific: Hypothesis testing is based on analyzing a sample from a population, and the conclusions drawn are specific to that particular sample.

- Possible errors: During hypothesis testing, there is a chance of committing type I error (rejecting a true null hypothesis) or type II error (failing to reject a false null hypothesis).

- Assumptions and requirements: Different tests have specific assumptions and requirements that must be met to accurately interpret results.

Learn All The Tricks Of The BI Trade

After reading this tutorial, you would have a much better understanding of hypothesis testing, one of the most important concepts in the field of Data Science . The majority of hypotheses are based on speculation about observed behavior, natural phenomena, or established theories.

If you are interested in statistics of data science and skills needed for such a career, you ought to explore the Post Graduate Program in Data Science.

If you have any questions regarding this ‘Hypothesis Testing In Statistics’ tutorial, do share them in the comment section. Our subject matter expert will respond to your queries. Happy learning!

1. What is hypothesis testing in statistics with example?

Hypothesis testing is a statistical method used to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample data to draw conclusions about a population. It involves formulating two competing hypotheses, the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (Ha), and then collecting data to assess the evidence. An example: testing if a new drug improves patient recovery (Ha) compared to the standard treatment (H0) based on collected patient data.

2. What is H0 and H1 in statistics?

In statistics, H0 and H1 represent the null and alternative hypotheses. The null hypothesis, H0, is the default assumption that no effect or difference exists between groups or conditions. The alternative hypothesis, H1, is the competing claim suggesting an effect or a difference. Statistical tests determine whether to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis based on the data.

3. What is a simple hypothesis with an example?

A simple hypothesis is a specific statement predicting a single relationship between two variables. It posits a direct and uncomplicated outcome. For example, a simple hypothesis might state, "Increased sunlight exposure increases the growth rate of sunflowers." Here, the hypothesis suggests a direct relationship between the amount of sunlight (independent variable) and the growth rate of sunflowers (dependent variable), with no additional variables considered.

4. What are the 2 types of hypothesis testing?

- One-tailed (or one-sided) test: Tests for the significance of an effect in only one direction, either positive or negative.

- Two-tailed (or two-sided) test: Tests for the significance of an effect in both directions, allowing for the possibility of a positive or negative effect.

The choice between one-tailed and two-tailed tests depends on the specific research question and the directionality of the expected effect.

5. What are the 3 major types of hypothesis?

The three major types of hypotheses are:

- Null Hypothesis (H0): Represents the default assumption, stating that there is no significant effect or relationship in the data.

- Alternative Hypothesis (Ha): Contradicts the null hypothesis and proposes a specific effect or relationship that researchers want to investigate.

- Nondirectional Hypothesis: An alternative hypothesis that doesn't specify the direction of the effect, leaving it open for both positive and negative possibilities.

Find our PL-300 Microsoft Power BI Certification Training Online Classroom training classes in top cities:

| Name | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Jul -21 Jul 2024, Weekend batch | Your City | ||

| 20 Jul -4 Aug 2024, Weekend batch | Your City | ||

| 10 Aug -25 Aug 2024, Weekend batch | Your City |

About the Author

Avijeet is a Senior Research Analyst at Simplilearn. Passionate about Data Analytics, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning, Avijeet is also interested in politics, cricket, and football.

Recommended Resources

Free eBook: Top Programming Languages For A Data Scientist

Normality Test in Minitab: Minitab with Statistics

Machine Learning Career Guide: A Playbook to Becoming a Machine Learning Engineer

- PMP, PMI, PMBOK, CAPM, PgMP, PfMP, ACP, PBA, RMP, SP, and OPM3 are registered marks of the Project Management Institute, Inc.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a tool for making statistical inferences about the population data. It is an analysis tool that tests assumptions and determines how likely something is within a given standard of accuracy. Hypothesis testing provides a way to verify whether the results of an experiment are valid.

A null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis are set up before performing the hypothesis testing. This helps to arrive at a conclusion regarding the sample obtained from the population. In this article, we will learn more about hypothesis testing, its types, steps to perform the testing, and associated examples.

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | |

| 4. | |

| 5. | |

| 6. | |

| 7. | |

| 8. |

What is Hypothesis Testing in Statistics?

Hypothesis testing uses sample data from the population to draw useful conclusions regarding the population probability distribution . It tests an assumption made about the data using different types of hypothesis testing methodologies. The hypothesis testing results in either rejecting or not rejecting the null hypothesis.

Hypothesis Testing Definition

Hypothesis testing can be defined as a statistical tool that is used to identify if the results of an experiment are meaningful or not. It involves setting up a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis. These two hypotheses will always be mutually exclusive. This means that if the null hypothesis is true then the alternative hypothesis is false and vice versa. An example of hypothesis testing is setting up a test to check if a new medicine works on a disease in a more efficient manner.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a concise mathematical statement that is used to indicate that there is no difference between two possibilities. In other words, there is no difference between certain characteristics of data. This hypothesis assumes that the outcomes of an experiment are based on chance alone. It is denoted as \(H_{0}\). Hypothesis testing is used to conclude if the null hypothesis can be rejected or not. Suppose an experiment is conducted to check if girls are shorter than boys at the age of 5. The null hypothesis will say that they are the same height.

Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is an alternative to the null hypothesis. It is used to show that the observations of an experiment are due to some real effect. It indicates that there is a statistical significance between two possible outcomes and can be denoted as \(H_{1}\) or \(H_{a}\). For the above-mentioned example, the alternative hypothesis would be that girls are shorter than boys at the age of 5.

Hypothesis Testing P Value

In hypothesis testing, the p value is used to indicate whether the results obtained after conducting a test are statistically significant or not. It also indicates the probability of making an error in rejecting or not rejecting the null hypothesis.This value is always a number between 0 and 1. The p value is compared to an alpha level, \(\alpha\) or significance level. The alpha level can be defined as the acceptable risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis. The alpha level is usually chosen between 1% to 5%.

Hypothesis Testing Critical region

All sets of values that lead to rejecting the null hypothesis lie in the critical region. Furthermore, the value that separates the critical region from the non-critical region is known as the critical value.

Hypothesis Testing Formula

Depending upon the type of data available and the size, different types of hypothesis testing are used to determine whether the null hypothesis can be rejected or not. The hypothesis testing formula for some important test statistics are given below:

- z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\). \(\overline{x}\) is the sample mean, \(\mu\) is the population mean, \(\sigma\) is the population standard deviation and n is the size of the sample.

- t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\). s is the sample standard deviation.

- \(\chi ^{2} = \sum \frac{(O_{i}-E_{i})^{2}}{E_{i}}\). \(O_{i}\) is the observed value and \(E_{i}\) is the expected value.

We will learn more about these test statistics in the upcoming section.

Types of Hypothesis Testing

Selecting the correct test for performing hypothesis testing can be confusing. These tests are used to determine a test statistic on the basis of which the null hypothesis can either be rejected or not rejected. Some of the important tests used for hypothesis testing are given below.

Hypothesis Testing Z Test

A z test is a way of hypothesis testing that is used for a large sample size (n ≥ 30). It is used to determine whether there is a difference between the population mean and the sample mean when the population standard deviation is known. It can also be used to compare the mean of two samples. It is used to compute the z test statistic. The formulas are given as follows:

- One sample: z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

- Two samples: z = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

Hypothesis Testing t Test

The t test is another method of hypothesis testing that is used for a small sample size (n < 30). It is also used to compare the sample mean and population mean. However, the population standard deviation is not known. Instead, the sample standard deviation is known. The mean of two samples can also be compared using the t test.

- One sample: t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

- Two samples: t = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{s_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{s_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

Hypothesis Testing Chi Square

The Chi square test is a hypothesis testing method that is used to check whether the variables in a population are independent or not. It is used when the test statistic is chi-squared distributed.

One Tailed Hypothesis Testing

One tailed hypothesis testing is done when the rejection region is only in one direction. It can also be known as directional hypothesis testing because the effects can be tested in one direction only. This type of testing is further classified into the right tailed test and left tailed test.

Right Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The right tail test is also known as the upper tail test. This test is used to check whether the population parameter is greater than some value. The null and alternative hypotheses for this test are given as follows:

\(H_{0}\): The population parameter is ≤ some value

\(H_{1}\): The population parameter is > some value.

If the test statistic has a greater value than the critical value then the null hypothesis is rejected

Left Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The left tail test is also known as the lower tail test. It is used to check whether the population parameter is less than some value. The hypotheses for this hypothesis testing can be written as follows:

\(H_{0}\): The population parameter is ≥ some value

\(H_{1}\): The population parameter is < some value.

The null hypothesis is rejected if the test statistic has a value lesser than the critical value.

Two Tailed Hypothesis Testing

In this hypothesis testing method, the critical region lies on both sides of the sampling distribution. It is also known as a non - directional hypothesis testing method. The two-tailed test is used when it needs to be determined if the population parameter is assumed to be different than some value. The hypotheses can be set up as follows:

\(H_{0}\): the population parameter = some value

\(H_{1}\): the population parameter ≠ some value

The null hypothesis is rejected if the test statistic has a value that is not equal to the critical value.

Hypothesis Testing Steps

Hypothesis testing can be easily performed in five simple steps. The most important step is to correctly set up the hypotheses and identify the right method for hypothesis testing. The basic steps to perform hypothesis testing are as follows:

- Step 1: Set up the null hypothesis by correctly identifying whether it is the left-tailed, right-tailed, or two-tailed hypothesis testing.

- Step 2: Set up the alternative hypothesis.

- Step 3: Choose the correct significance level, \(\alpha\), and find the critical value.

- Step 4: Calculate the correct test statistic (z, t or \(\chi\)) and p-value.

- Step 5: Compare the test statistic with the critical value or compare the p-value with \(\alpha\) to arrive at a conclusion. In other words, decide if the null hypothesis is to be rejected or not.

Hypothesis Testing Example

The best way to solve a problem on hypothesis testing is by applying the 5 steps mentioned in the previous section. Suppose a researcher claims that the mean average weight of men is greater than 100kgs with a standard deviation of 15kgs. 30 men are chosen with an average weight of 112.5 Kgs. Using hypothesis testing, check if there is enough evidence to support the researcher's claim. The confidence interval is given as 95%.

Step 1: This is an example of a right-tailed test. Set up the null hypothesis as \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 100.

Step 2: The alternative hypothesis is given by \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) > 100.

Step 3: As this is a one-tailed test, \(\alpha\) = 100% - 95% = 5%. This can be used to determine the critical value.

1 - \(\alpha\) = 1 - 0.05 = 0.95

0.95 gives the required area under the curve. Now using a normal distribution table, the area 0.95 is at z = 1.645. A similar process can be followed for a t-test. The only additional requirement is to calculate the degrees of freedom given by n - 1.

Step 4: Calculate the z test statistic. This is because the sample size is 30. Furthermore, the sample and population means are known along with the standard deviation.

z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

\(\mu\) = 100, \(\overline{x}\) = 112.5, n = 30, \(\sigma\) = 15

z = \(\frac{112.5-100}{\frac{15}{\sqrt{30}}}\) = 4.56

Step 5: Conclusion. As 4.56 > 1.645 thus, the null hypothesis can be rejected.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Intervals

Confidence intervals form an important part of hypothesis testing. This is because the alpha level can be determined from a given confidence interval. Suppose a confidence interval is given as 95%. Subtract the confidence interval from 100%. This gives 100 - 95 = 5% or 0.05. This is the alpha value of a one-tailed hypothesis testing. To obtain the alpha value for a two-tailed hypothesis testing, divide this value by 2. This gives 0.05 / 2 = 0.025.

Related Articles:

- Probability and Statistics

- Data Handling

Important Notes on Hypothesis Testing

- Hypothesis testing is a technique that is used to verify whether the results of an experiment are statistically significant.

- It involves the setting up of a null hypothesis and an alternate hypothesis.

- There are three types of tests that can be conducted under hypothesis testing - z test, t test, and chi square test.

- Hypothesis testing can be classified as right tail, left tail, and two tail tests.

Examples on Hypothesis Testing

- Example 1: The average weight of a dumbbell in a gym is 90lbs. However, a physical trainer believes that the average weight might be higher. A random sample of 5 dumbbells with an average weight of 110lbs and a standard deviation of 18lbs. Using hypothesis testing check if the physical trainer's claim can be supported for a 95% confidence level. Solution: As the sample size is lesser than 30, the t-test is used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 90, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) > 90 \(\overline{x}\) = 110, \(\mu\) = 90, n = 5, s = 18. \(\alpha\) = 0.05 Using the t-distribution table, the critical value is 2.132 t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\) t = 2.484 As 2.484 > 2.132, the null hypothesis is rejected. Answer: The average weight of the dumbbells may be greater than 90lbs

- Example 2: The average score on a test is 80 with a standard deviation of 10. With a new teaching curriculum introduced it is believed that this score will change. On random testing, the score of 38 students, the mean was found to be 88. With a 0.05 significance level, is there any evidence to support this claim? Solution: This is an example of two-tail hypothesis testing. The z test will be used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 80, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) ≠ 80 \(\overline{x}\) = 88, \(\mu\) = 80, n = 36, \(\sigma\) = 10. \(\alpha\) = 0.05 / 2 = 0.025 The critical value using the normal distribution table is 1.96 z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\) z = \(\frac{88-80}{\frac{10}{\sqrt{36}}}\) = 4.8 As 4.8 > 1.96, the null hypothesis is rejected. Answer: There is a difference in the scores after the new curriculum was introduced.

- Example 3: The average score of a class is 90. However, a teacher believes that the average score might be lower. The scores of 6 students were randomly measured. The mean was 82 with a standard deviation of 18. With a 0.05 significance level use hypothesis testing to check if this claim is true. Solution: The t test will be used. \(H_{0}\): \(\mu\) = 90, \(H_{1}\): \(\mu\) < 90 \(\overline{x}\) = 110, \(\mu\) = 90, n = 6, s = 18 The critical value from the t table is -2.015 t = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}\) t = \(\frac{82-90}{\frac{18}{\sqrt{6}}}\) t = -1.088 As -1.088 > -2.015, we fail to reject the null hypothesis. Answer: There is not enough evidence to support the claim.

go to slide go to slide go to slide

Book a Free Trial Class

FAQs on Hypothesis Testing

What is hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis testing in statistics is a tool that is used to make inferences about the population data. It is also used to check if the results of an experiment are valid.

What is the z Test in Hypothesis Testing?

The z test in hypothesis testing is used to find the z test statistic for normally distributed data . The z test is used when the standard deviation of the population is known and the sample size is greater than or equal to 30.

What is the t Test in Hypothesis Testing?

The t test in hypothesis testing is used when the data follows a student t distribution . It is used when the sample size is less than 30 and standard deviation of the population is not known.

What is the formula for z test in Hypothesis Testing?

The formula for a one sample z test in hypothesis testing is z = \(\frac{\overline{x}-\mu}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}}\) and for two samples is z = \(\frac{(\overline{x_{1}}-\overline{x_{2}})-(\mu_{1}-\mu_{2})}{\sqrt{\frac{\sigma_{1}^{2}}{n_{1}}+\frac{\sigma_{2}^{2}}{n_{2}}}}\).

What is the p Value in Hypothesis Testing?

The p value helps to determine if the test results are statistically significant or not. In hypothesis testing, the null hypothesis can either be rejected or not rejected based on the comparison between the p value and the alpha level.

What is One Tail Hypothesis Testing?

When the rejection region is only on one side of the distribution curve then it is known as one tail hypothesis testing. The right tail test and the left tail test are two types of directional hypothesis testing.

What is the Alpha Level in Two Tail Hypothesis Testing?

To get the alpha level in a two tail hypothesis testing divide \(\alpha\) by 2. This is done as there are two rejection regions in the curve.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Crit Care Med

- v.23(Suppl 3); 2019 Sep

An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors

Priya ranganathan.

1 Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

The second article in this series on biostatistics covers the concepts of sample, population, research hypotheses and statistical errors.

How to cite this article

Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS. An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(Suppl 3):S230–S231.

Two papers quoted in this issue of the Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine report. The results of studies aim to prove that a new intervention is better than (superior to) an existing treatment. In the ABLE study, the investigators wanted to show that transfusion of fresh red blood cells would be superior to standard-issue red cells in reducing 90-day mortality in ICU patients. 1 The PROPPR study was designed to prove that transfusion of a lower ratio of plasma and platelets to red cells would be superior to a higher ratio in decreasing 24-hour and 30-day mortality in critically ill patients. 2 These studies are known as superiority studies (as opposed to noninferiority or equivalence studies which will be discussed in a subsequent article).

SAMPLE VERSUS POPULATION

A sample represents a group of participants selected from the entire population. Since studies cannot be carried out on entire populations, researchers choose samples, which are representative of the population. This is similar to walking into a grocery store and examining a few grains of rice or wheat before purchasing an entire bag; we assume that the few grains that we select (the sample) are representative of the entire sack of grains (the population).