What Is Applied Psychology & Why Is It Important?

Industry Advice Healthcare

In our complex and interconnected world, the study of human behavior has become crucial. These insights help us better understand consumer behaviors, public health trends, and even voting patterns.

Nearly all of these instances push us to ask the question: Why do people make the choices they do? Applied psychology is key to unlocking the answer to this question and transforming our understanding of the human experience.

What Is Applied Psychology?

Applied psychology is the practical application of psychological principles and theories from other types of psychology to address real-world challenges.

Some of these psychology fields include:

- Clinical psychology: A specialty within the field of psychology that is geared more toward populations with diagnosable mental disorders and serious psychopathologies.

- Counseling psychology: A general practice within the broader field of psychology that focuses on how patients function—both individually and in their relationships with family, friends, work, and the broader community.

- Forensic psychology: A specialty in professional psychology characterized by activities primarily intended to provide professional psychological expertise within the judicial and legal systems.

- Health psychology: A branch within the psychology field that focuses on how social, psychological, and biological factors combine to influence human health.

- Industrial-organizational psychology: The study and assessment of individual, group, and organizational dynamics within the workplace. Social psychology: The study of the mind and behavior of people, considering personality traits, interpersonal relationships, and group behaviors.

“Applied psychology is really taking some of the basic research that’s done in those fields of psychology and applying it,” says Christie Rizzo, Associate Professor of Applied Psychology at Northeastern’s Bouvé College of Health Sciences. “That’s where the term comes from.”

As a result, this multifaceted field extends its influence into nearly every aspect of our lives. Professionals leveraging applied psychology use their expertise to help individuals, organizations, and communities via assessments, interventions, and strategies to promote positive outcomes and better quality of life.

While applied psychology touches on several specialities within psychology, it’s important to note the key differences between this field of study and others.

Basic Psychology vs. Applied Psychology

Basic psychology—also known as academic psychology—studies the fundamental principles, theories, and concepts of human behavior. According to Rizzo, it’s centered around conducting research, designing experiments, and generating theories to uncover why humans behave the way they do.

Applied psychology is different in that it focuses on applying that research. “The main difference is really thinking about how the research, concepts, and tools from basic psychology should be applied,” Rizzo says.

This often takes the form of prevention, which is an important aspect of applied psychology. By using basic psychology research to design and implement interventions, you can mitigate various health and social issues.

“Prevention science is an application of psychology that designs and tests interventions that promote mental health and reduces the risk of problem behaviors,” Rizzo says.

4 Reasons Why Applied Psychology Is Important

Whether it’s preventing substance abuse, reducing the risk of mental health disorders, or addressing behavioral problems in children, applied psychology offers evidence-based strategies that empower individuals and communities to lead healthier, more fulfilling lives.

Here are a few reasons why applied psychology has become increasingly important.

1. Improves Mental Health Outcomes

Mental health has garnered increased attention within the psychology field due to growing recognition of its significance and relevance. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , the percentage of adults who received mental health treatment increased from 19 percent in 2019 to 22 percent in 2021.

Through applied psychology, mental health professionals can employ scientific principles to understand and address the root causes of mental health issues—with an emphasis on early intervention and risk reduction. This work is essential because it offers a proactive, evidence-based approach to reducing mental health problems and combating the societal challenges that can cause them.

The emergence of technology is a huge part of this prevention initiative as well.

“Using technology can move applied psychology forward because that’s where everybody’s communicating,” Rizzo says. “And that’s where folks are looking for resources. So we need to be able to take advantage of that.”

In the case of applied psychology, this can mean leveraging social media campaigns or even phone applications focused on improving mental health. With behavioral data, applied psychology can help inform these campaigns to ensure they resonate with those who statistically suffer from mental health issues .

2. Enhances Child Welfare

While mental health is incredibly important, ensuring the welfare of children is another important issue that applied psychology aims to address. In 2021, there were at least 588,229 child victims of abuse or neglect , but child welfare professionals try to leverage psychological methods to avoid these tragedies.

Child welfare professionals are pivotal in developing and applying intervention programs that prioritize the safety and well-being of children. They often work in collaboration with state and federal government agencies to ensure programs are compliant with the highest standards of ethics, efficacy, and child protection.

Much like mental health challenges, addressing a child’s welfare requires applied psychology prevention techniques to proactively avoid societal and environmental factors that negatively affect a child’s well-being.

Some examples of what applied psychology aims to prevent include:

- Child abuse and neglect

- Educational challenges

- Behavioral disorders

“Examples include programs that prevent drug use in adolescents, reform educational practices, and support families managing the stress of family violence,” Rizzo says.

Social media plays a huge role in moving these applied psychology initiatives forward. Before, psychologists focused on prevention work through face-to-face contact. In today’s digitally connected world, there’s untapped potential to leverage data from large communities and still be able to reach them outside of personal contact.

“We can harness social media for good,” Rizzo says. “Young people can seek out other individuals with similar identities to their own and create a social support system online.”

3. Prevents Substance Abuse

Substance abuse affects millions of Americans. In fact, 20.4 million people in the United States were diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder in 2019 alone.

Applied psychology is critical in the treatment and prevention of substance abuse. This is achieved through early intervention services and screenings that aim to better the individual, their relationships, and communities affected by substance abuse. By understanding risk factors and protective factors at both the individual and environmental levels, professionals can implement targeted interventions to address potential issues before they escalate.

While early intervention of substance abuse is important, addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition. Therefore community-based interventions, another element of applied psychology, are another necessary aspect of substance abuse treatment to ensure individuals don’t face long-term health consequences or legal issues.

This can involve:

- Community organizing

- Policy advocacy

- Development of support networks

Applied psychology does not just play a role in these programs execution, it also ensures substance abuse counselors and other professionals are able to evaluate and determine the efficacy of a community program.

“We’re so grateful when we have programs aimed at preventing substance abuse in the community,” Rizzo says. “But it’s difficult when those programs have never been evaluated for being useful. That’s why applied psychology trains professionals to effectively evaluate these programs.”

4. Work Performance

While work performance does not necessarily affect peoples’ well-being, there is still work that needs to be done to improve business performance and employee satisfaction in the workplace.

In fact, in the first half of 2022, productivity plunged by the sharpest rate on record going back to 1947 according to the Washington Post .

Applied psychology plays a vital role in improving an organization’s operations through psychological principles and research methods aimed at enhancing employee performance. By prioritizing the well-being of employees and applying evidence-based psychological principles, organizations can create a positive work environment conducive to productivity, resulting in long-term success and sustainability.

Take the First Step Toward a Career in Applied Psychology

While applied psychology is a relatively new field, it touches on established psychology methods and theories, making it the best educational route for those still searching for alternative career paths in psychology.

If you’re interested in studying applied psychology, Northeastern’s MS in Applied Psychology is a dynamic, forward-thinking program designed to cater to the professional aspirations of students who want a career beyond traditional psychology roles. It’s also a great program to gain exposure to a graduate-level curriculum to help students work toward their doctorate or refine their professional goals with the guidance of experienced faculty advisors.

Subscribe below to receive future content from the Graduate Programs Blog.

About samantha jones, related articles, 4 pressing global health problems we face today, global health careers: how can i make a difference.

Compliance Specialists: Who They Are and What They Earn

Did you know.

Advanced degree holders earn a salary an average 25% higher than bachelor's degree holders. (Economic Policy Institute, 2021)

Northeastern University Graduate Programs

Explore our 200+ industry-aligned graduate degree and certificate programs.

Most Popular:

Tips for taking online classes: 8 strategies for success, public health careers: what can you do with an mph, 7 international business careers that are in high demand, edd vs. phd in education: what’s the difference, 7 must-have skills for data analysts, in-demand biotechnology careers shaping our future, the benefits of online learning: 8 advantages of online degrees, how to write a statement of purpose for graduate school, the best of our graduate blog—right to your inbox.

Stay up to date on our latest posts and university events. Plus receive relevant career tips and grad school advice.

By providing us with your email, you agree to the terms of our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Keep Reading:

5 Homeland Security Careers for the Future

The Top 3 Job Requirements For a Homeland Security Career

What Are Security Studies?

Should I Go To Grad School: 4 Questions to Consider

Applied Psychology Research

About the Publisher

Editor-in-Chief

Publication Frequency

- Other Journals

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

| : Appl. Psychol. Res. : The publication frequency of (APR) is bi-annual. :Click for more details : Open Access : %-->: days : days

|

About the Journal

- Social Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Managerial Psychology

- Economic Psychology

- Environmental Psychology

- Engineering Psychology

- Sport Psychology

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Forensic and Legal Psychology

Announcements

Please follow the journal's author guideline and the required article template to prepare your manuscript. | |

| Posted: 2023-09-06 | |

Table of Contents

| Original Research Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.359 Views, PDF Downloads | 100 Views, 200 Downloads |

| Original Research Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.417 Views, PDF Downloads Frequently, the contribution of exercise to the elderly and the associated benefits of such activities are discussed. This paper deals with the contribution of exercise to the levels of quality of life, fatigue, and pain management. Then, quantitative and cross-sectional research is carried out to investigate the contribution of physical exercise to the levels of quality of life, fatigue, and pain management in women over 60 years of age. For the data collection, the questionnaire used consisted of the Missoula—VITAS Quality of Life Index (MVQOLI), the Pain Assessment Questionnaire (PSeQ), and the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS). From the statistical analysis made between exercise and quality of life, fatigue, and pain management of the women over 60 who participated in the research, it follows that women undergoing exercise show a better quality of life and less fatigue, while no statistically significant difference was detected in terms of pain management. It seems that exercise affects positively quality of life and fatigue. Potential implications must be addressed in order to organize more exercise programs, particularly for older people. | 38 Views, 76 Downloads |

| Original Research Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.390 Views, PDF Downloads | 24 Views, 48 Downloads |

| Original Research Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.504 Views, PDF Downloads | 46 Views, 92 Downloads |

| Review Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.358 Views, PDF Downloads | 200 Views, 400 Downloads |

| Review Articles , 2(1); doi: 10.59400/apr.v2i1.400 Views, PDF Downloads | 24 Views, 48 Downloads |

Address:73 Upper Paya Lebar Road #07-02B-01 Centro Bianco Singapore 534818

phone:+65 83184869

ⓒ2021-2022 by Academic Publishing Pte Ltd

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

applied psychology

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Verywell Mind - Applied Psychology Careers

applied psychology , the use of methods and findings of scientific psychology to solve practical problems of human and animal behaviour and experience. A more precise definition is impossible because the activities of applied psychology range from laboratory experimentation through field studies to direct services for troubled persons.

The same intellectual streams whose confluence produced psychology as an independent discipline toward the end of the 19th century led to the later development of applied psychology. In 1883 the publication of Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development by Francis Galton foreshadowed the measurement of individual psychological differences. In 1896 at the University of Pennsylvania , Lightner Witmer established the world’s first psychological clinic and in so doing originated the field of clinical psychology. Intelligence testing began with the work of French psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon in the Paris schools in the early 1900s. Group testing, legal problems, industrial efficiency , motivation, and delinquency were among other early areas of application. At the Carnegie Institute of Technology , a division of applied psychology was established as a teaching and research department in 1915. The Journal of Applied Psychology appeared in 1917, along with Applied Psychology , the first textbook in the field, coauthored by Harry L. Hollingworth and Albert T. Poffenberger.

Early emphases in applied psychology included vocational testing, teaching methods, evaluation of attitudes and morale, performance under stress, propaganda and psychological warfare , rehabilitation, and counseling . Educational psychologists began directing their efforts toward the early identification and discovery of talented persons. Their research complemented the work of counseling psychologists, who sought to help persons clarify and attain their educational , vocational, and personal goals. Concern for the optimum utilization of human resources contributed to the development of industrial-organizational psychology . The development of aviation and space exploration fostered rapid growth in the field of engineering psychology .

In response to society’s concern for treatment of the mentally ill and for development of preventive measures against mental illness , clinical psychology has shown tremendous growth within the broader field of psychology. Psychologists have studied the application and effects of automation , and in developing countries they have helped with the problems of rapid industrialization and human resources planning.

Regardless of applied psychologists’ professional focus, their job description is likely to overlap with those of other areas. The applied psychologist may or may not teach or engage in original research. In addition to drawing on experimental findings gleaned from psychological research, the applied psychologist uses information from many disciplines . The scope of the field is continually broadening as new types of problems arise. Other branches of applied psychology include consumer, school, and community psychology . Prevention and treatment of emotional problems have received a great deal of attention, as have medically related areas such as sports psychology and the psychology of chronic illness.

Psychometrics , or the measurement and evaluation of psychological variables such as personality , aptitude, or performance, is an integral part of applied psychology fields. For example, the clinical psychologist may be interested in measuring the traits of aggressiveness or obsessiveness; the industrial psychologist, work effectiveness under certain conditions of lighting or office design; or the community psychologist, the psychological effects of living in a high crime area. See also clinical psychology ; educational psychology ; industrial psychology .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Applied Research Is Used in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

Verywell / JR Bee

Basic vs. Applied Research

How it works, potential challenges.

- Real-World Applications

Applied research refers to scientific study and research that seeks to solve practical problems. This type of research plays an important role in solving everyday problems that can have an impact on life, work, health, and overall well-being. For example, it can be used to find solutions to everyday problems, cure illness, and develop innovative technologies.

There are many different types of psychologists who perform applied research. Human factors or industrial/organizational psychologists often do this type of research.

A few examples of applied research in psychology include:

- Analyzing what type of prompts will inspire people to volunteer their time to charities

- Investigating if background music in a work environment can contribute to greater productivity

- Investigating which treatment approach is the most effective for reducing anxiety

- Researching which strategies work best to motivate workers

- Studying different keyboard designs to determine which is the most efficient and ergonomic

As you may notice, all of these examples explore topics that will address real-world issues. This immediate and practical application of the findings is what distinguishes applied research from basic research , which instead focuses on theoretical concerns.

Basic research tends to focus on "big picture" topics, such as increasing the scientific knowledge base around a particular topic. Applied research tends to work toward solving specific problems that affect people in the here and now.

For example a social psychologist may perform basic research on how different factors may contribute to violence in general. But if a social psychologist were conducting applied research, they may be tackling the question of what specific programs can be implemented to reduce violence in school settings.

However, basic research and applied research are actually closely intertwined. The information learned from basic research often builds the basis on which applied research is formed.

Basic research often informs applied research, and applied research often helps basic researchers refine their theories.

Applied research usually starts by identifying a problem that exists in the real world. Then psychologists begin to conduct research in order to identify a solution.

The type of research used depends on a variety of factors. This includes unique characteristics of the situation and the kind of problem psychologists are looking to solve.

Researchers might opt to use naturalistic observation to see the problem as it occurs in a real-world setting. They may then conduct experiments to determine why the problem occurs and to explore different solutions that may solve it.

As with any type of research, challenges can arise when conducting applied research in psychology. Some potential problems that researchers may face include:

Ethical Challenges

When conducting applied research in a naturalistic setting, researchers have to avoid ethical issues, which can make research more difficult. For example, they may come across concerns about privacy and informed consent.

In some cases, such as in workplace studies conducted by industrial-organizational psychologists, participants may feel pressured or even coerced into participating as a condition of their employment. Such factors sometimes impact the result of research studies.

Problems With Validity

Since applied research often takes place in the field, it can be difficult for researchers to maintain complete control over all of the variables . Extraneous variables can also exert a subtle influence that experimenters may not even consider could have an effect on the results.

In many cases, researchers are forced to strike a balance between a study's ecological validity (which is usually quite high in applied research) and the study's internal validity .

Since applied research focuses on taking the results of scientific research and applying it to real-world situations, those who work in this line of research tend to be more concerned with the external validity of their work.

External validity refers to the extent that scientific findings can be generalized to other populations.

Researchers don't just want to know if the results of their experiments apply to the participants in their studies, rather they want these results to also apply to larger populations outside of the lab.

External validity is often of particular importance in applied research. Researchers want to know that their findings can be applied to real people in real settings.

How It's Used in the Real-World

Here are some examples of how applied research is used to solve real-world problems:

- A hospital may conduct applied research to figure out how to best prepare patients for certain types of surgical procedures.

- A business may hire an applied psychologist to assess how to design a workplace console to maximize efficiency and productivity while minimizing worker fatigue and error.

- An organization may hire an applied researcher to determine how to select employees that are best suited for certain positions within the company.

Applied research is an important tool in the process of understanding the human mind and behavior. Thanks to much of this research, psychologists are able to investigate problems that affect people's daily lives. This kind of research specifically targets real-world issues, however it also contributes to knowledge about how people think and behave.

National Science Foundation. Definitions of research and development: An annotated compilation of official sources .

CDC. Evaluation briefs .

Helmchen H. Ethical issues in naturalistic versus controlled trials . Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2011;13(2):173‐182.

Truijens FL, Cornelis S, Desmet M, De Smet MM, Meganck R. Validity beyond measurement: Why psychometric validity is insufficient for valid psychotherapy research . Front Psychol . 2019;10:532. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00532

McBride D. The Process Of Research In Psychology . SAGE Publications; 2018.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

LET US HELP

Welcome to Capella

Select your program and we'll help guide you through important information as you prepare for the application process.

FIND YOUR PROGRAM

Connect with us

A team of dedicated enrollment counselors is standing by, ready to answer your questions and help you get started.

- Capella University Blog

What is Applied Research in psychology?

March 21, 2024

From academia and behavioral health to military and corrections, there are many ways psychology can help people.

In fact, mental health programs in hospitals, non-profits, governmental programs, and more have their origins in carefully researched data that psychology professionals have helped create.

Whether theyâre designing studies, conducting research, or interpreting the final data, a masterâs-level research psychology professional can inform best practices in psychology to tackle important issues like recidivism, PTSD, and depression.

Bethany Lohr, PhD, faculty chair of Capella Universityâs Clinical Psychology program, explains the benefits of an advanced degree in Applied Research for both clinical professionals and those following an academic path.

Q. First of all, what is applied research?

A. Applied research is a scientific study within the field of psychology that focuses on solving problems and innovating new technologies. Its main purpose is to conduct scientific research and apply it to real-world situations. As opposed to delivering mental health services, itâs about looking at human behavior and thinking of ways to meet the needs of a given situation.

Q. What type of skills could I develop with an MS in Clinical Psychology, Applied Research?

A. Skills that could help you be effective in the field of applied research include:

- Observation: The ability to observe and take note of what you observe is a critical skill.

- Data analysis: Be able to interpret statistics as well as understand trends and draw predictions based on data.

- Creative problem-solving: Be curious and able to approach a problem from different angles in the search for possible solutions.

- Interpersonal communication: Be prepared to spend time interviewing different groups and reporting findings.

- Ethical awareness: Act with integrity when factors such as privacy and informed consent come up depending on the setting.

- Adaptability: Remain level-headed amid changing circumstances.

Learn how a Master of Science in Clinical Psychology, Applied Research can help you build professional skills.

Q. What are some ways applied research can be used?

A. An applied research specialization could be used in any field where psychological research is an element.

A background in applied research in clinical psychology helps someone design and lead a study, interpret findings and advocate for programs based on those interpretations. Further, it helps make them the right person to lead training for these programs.

Applied research is often a relevant subject area for people who write government grants, such as those who write for mental health programs. An applied research background provides understanding to skillfully interpret the governmentâs massive data sets and advocate for legislation that relies on data to support it.

Pertaining to healthcare, applied research in clinical psychology could be applied to projects related to quality improvement or quality assurance in areas like emergency room waiting times, patient data collection, triage and other improvements that can impact patient care.

In the case of workforce development, applied research could be used to tailor questions to determine which strategies work best to motivate employees. When hiring, applied research could be applied to help establish job qualifications or criteria to best meet the needs of a department and screen candidates who will mesh well with team dynamics.

Applied research can help some organizations analyze what kinds of prompts might inspire people to volunteer their time and skills to charities.

Applied research could even come into play in theme park design when deciding where to place trash cans or queue line management to keep guests engaged.

All these situations rely on the analysis of human behavior and predictions and proposals based on those observations.

Q. Beyond the workplace, who else is the MS in Clinical Psychology, Applied Research for?

A. A Master of Science in Clinical Psychology, Applied Research program involves coursework that teaches the research skills and knowledge that may help you prepare when pursuing a PhD . Major topics in a PhD program could include research methodology, psychotherapy theories, tests and measurement, psychopathology, human development, ethical principles and diversity.

Additionally, the applied research specialization can help prepare you to pursue a PsyD in Clinical Psychology .

Q. Is this specialty just for academics and non-therapy professionals? Would therapy professionals benefit from this knowledge as well?

A. Someone in the therapy field can also benefit from understanding applied research, especially if they think theyâll want to pursue a doctoral degree down the road. If they want to continue in therapy practice, this masterâs can help them interpret psychology research that may inform their therapeutic treatment plans.

In short, applied research may be a good option for expanding professional expertise. It all depends on your professional goals.

Learn more about Capellaâs Masterâs in Clinical Psychology, Applied Research degree program.

You may also like

The difference between school counselors and school psychologists

Which psychology career path is best for me?

Start learning today.

Get started on your journey now by connecting with an enrollment counselor. See how Capella may be a good fit for you, and start the application process.

Please Exit Private Browsing Mode

Your internet browser is in private browsing mode. Please turn off private browsing mode if you wish to use this site.

Are you sure you want to cancel?

- Applied Psychology

Subject Area and Category

- Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous)

- Developmental and Educational Psychology

Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Publication type

0269994X, 14640597

1955, 1961-1992, 1996-2023

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

| Category | Year | Quartile |

|---|---|---|

| Applied Psychology | 1999 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2000 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2001 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2002 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2003 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2004 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2005 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2006 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2007 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2008 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2009 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2010 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2011 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2012 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2013 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2014 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2015 | Q2 |

| Applied Psychology | 2016 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2017 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2018 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2019 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2020 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2021 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2022 | Q1 |

| Applied Psychology | 2023 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 1999 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2000 | Q2 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2001 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2002 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2003 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2004 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2005 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2006 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2007 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2008 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2009 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2010 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2011 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2012 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2013 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2014 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2015 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2016 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2017 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2018 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2019 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2020 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2021 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2022 | Q1 |

| Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous) | 2023 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 1999 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2000 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2001 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2002 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2003 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2004 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2005 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2006 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2007 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2008 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2009 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2010 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2011 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2012 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2013 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2014 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2015 | Q2 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2016 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2017 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2018 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2019 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2020 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2021 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2022 | Q1 |

| Developmental and Educational Psychology | 2023 | Q1 |

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

| Year | SJR |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 0.767 |

| 2000 | 0.599 |

| 2001 | 0.626 |

| 2002 | 0.789 |

| 2003 | 0.813 |

| 2004 | 0.829 |

| 2005 | 0.724 |

| 2006 | 0.957 |

| 2007 | 1.113 |

| 2008 | 0.952 |

| 2009 | 0.871 |

| 2010 | 0.889 |

| 2011 | 1.325 |

| 2012 | 1.481 |

| 2013 | 1.571 |

| 2014 | 1.510 |

| 2015 | 1.020 |

| 2016 | 1.228 |

| 2017 | 1.406 |

| 2018 | 1.958 |

| 2019 | 1.457 |

| 2020 | 1.497 |

| 2021 | 1.590 |

| 2022 | 2.279 |

| 2023 | 2.664 |

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

| Year | Documents |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 29 |

| 2000 | 35 |

| 2001 | 31 |

| 2002 | 29 |

| 2003 | 36 |

| 2004 | 33 |

| 2005 | 34 |

| 2006 | 30 |

| 2007 | 44 |

| 2008 | 50 |

| 2009 | 35 |

| 2010 | 31 |

| 2011 | 30 |

| 2012 | 33 |

| 2013 | 29 |

| 2014 | 29 |

| 2015 | 27 |

| 2016 | 25 |

| 2017 | 25 |

| 2018 | 28 |

| 2019 | 26 |

| 2020 | 60 |

| 2021 | 70 |

| 2022 | 65 |

| 2023 | 94 |

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

| Cites per document | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 1999 | 1.049 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2000 | 1.333 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2001 | 1.404 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2002 | 1.033 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2003 | 1.371 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2004 | 1.718 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2005 | 1.659 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2006 | 2.068 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2007 | 2.338 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2008 | 3.156 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2009 | 2.854 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2010 | 3.189 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2011 | 3.650 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2012 | 4.904 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2013 | 3.488 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2014 | 3.496 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2015 | 3.215 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2016 | 3.246 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2017 | 3.473 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2018 | 4.358 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2019 | 4.105 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2020 | 4.558 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2021 | 4.928 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2022 | 7.391 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2023 | 9.475 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 1999 | 1.049 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2000 | 1.230 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2001 | 1.043 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2002 | 1.063 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2003 | 1.347 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2004 | 1.313 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2005 | 1.418 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2006 | 2.117 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2007 | 2.474 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2008 | 2.528 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2009 | 2.500 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2010 | 3.093 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2011 | 3.879 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2012 | 3.146 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2013 | 3.117 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2014 | 3.413 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2015 | 2.890 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2016 | 2.812 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2017 | 3.469 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2018 | 4.013 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2019 | 3.897 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2020 | 4.152 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2021 | 4.614 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2022 | 7.564 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2023 | 9.667 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 1999 | 0.978 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2000 | 0.754 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2001 | 1.047 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2002 | 1.015 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2003 | 0.983 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2004 | 1.108 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2005 | 1.145 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2006 | 2.343 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2007 | 1.906 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2008 | 1.676 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2009 | 2.330 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2010 | 3.412 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2011 | 2.076 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2012 | 2.230 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2013 | 3.127 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2014 | 2.903 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2015 | 2.086 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2016 | 2.393 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2017 | 2.962 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2018 | 3.660 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2019 | 3.132 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2020 | 3.444 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2021 | 4.360 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2022 | 7.954 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2023 | 9.533 |

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

| Cites | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Self Cites | 1999 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2000 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2001 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2002 | 5 |

| Self Cites | 2003 | 1 |

| Self Cites | 2004 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2005 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2006 | 13 |

| Self Cites | 2007 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2008 | 16 |

| Self Cites | 2009 | 2 |

| Self Cites | 2010 | 5 |

| Self Cites | 2011 | 7 |

| Self Cites | 2012 | 3 |

| Self Cites | 2013 | 21 |

| Self Cites | 2014 | 21 |

| Self Cites | 2015 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2016 | 12 |

| Self Cites | 2017 | 7 |

| Self Cites | 2018 | 7 |

| Self Cites | 2019 | 8 |

| Self Cites | 2020 | 12 |

| Self Cites | 2021 | 27 |

| Self Cites | 2022 | 39 |

| Self Cites | 2023 | 54 |

| Total Cites | 1999 | 64 |

| Total Cites | 2000 | 91 |

| Total Cites | 2001 | 96 |

| Total Cites | 2002 | 101 |

| Total Cites | 2003 | 128 |

| Total Cites | 2004 | 126 |

| Total Cites | 2005 | 139 |

| Total Cites | 2006 | 218 |

| Total Cites | 2007 | 240 |

| Total Cites | 2008 | 273 |

| Total Cites | 2009 | 310 |

| Total Cites | 2010 | 399 |

| Total Cites | 2011 | 450 |

| Total Cites | 2012 | 302 |

| Total Cites | 2013 | 293 |

| Total Cites | 2014 | 314 |

| Total Cites | 2015 | 263 |

| Total Cites | 2016 | 239 |

| Total Cites | 2017 | 281 |

| Total Cites | 2018 | 309 |

| Total Cites | 2019 | 304 |

| Total Cites | 2020 | 328 |

| Total Cites | 2021 | 526 |

| Total Cites | 2022 | 1180 |

| Total Cites | 2023 | 1885 |

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

| Cites | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| External Cites per document | 1999 | 1.049 |

| External Cites per document | 2000 | 1.176 |

| External Cites per document | 2001 | 1.000 |

| External Cites per document | 2002 | 1.011 |

| External Cites per document | 2003 | 1.337 |

| External Cites per document | 2004 | 1.271 |

| External Cites per document | 2005 | 1.378 |

| External Cites per document | 2006 | 1.990 |

| External Cites per document | 2007 | 2.433 |

| External Cites per document | 2008 | 2.380 |

| External Cites per document | 2009 | 2.484 |

| External Cites per document | 2010 | 3.054 |

| External Cites per document | 2011 | 3.819 |

| External Cites per document | 2012 | 3.115 |

| External Cites per document | 2013 | 2.894 |

| External Cites per document | 2014 | 3.185 |

| External Cites per document | 2015 | 2.846 |

| External Cites per document | 2016 | 2.671 |

| External Cites per document | 2017 | 3.383 |

| External Cites per document | 2018 | 3.922 |

| External Cites per document | 2019 | 3.795 |

| External Cites per document | 2020 | 4.000 |

| External Cites per document | 2021 | 4.377 |

| External Cites per document | 2022 | 7.314 |

| External Cites per document | 2023 | 9.390 |

| Cites per document | 1999 | 1.049 |

| Cites per document | 2000 | 1.230 |

| Cites per document | 2001 | 1.043 |

| Cites per document | 2002 | 1.063 |

| Cites per document | 2003 | 1.347 |

| Cites per document | 2004 | 1.313 |

| Cites per document | 2005 | 1.418 |

| Cites per document | 2006 | 2.117 |

| Cites per document | 2007 | 2.474 |

| Cites per document | 2008 | 2.528 |

| Cites per document | 2009 | 2.500 |

| Cites per document | 2010 | 3.093 |

| Cites per document | 2011 | 3.879 |

| Cites per document | 2012 | 3.146 |

| Cites per document | 2013 | 3.117 |

| Cites per document | 2014 | 3.413 |

| Cites per document | 2015 | 2.890 |

| Cites per document | 2016 | 2.812 |

| Cites per document | 2017 | 3.469 |

| Cites per document | 2018 | 4.013 |

| Cites per document | 2019 | 3.897 |

| Cites per document | 2020 | 4.152 |

| Cites per document | 2021 | 4.614 |

| Cites per document | 2022 | 7.564 |

| Cites per document | 2023 | 9.667 |

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

| Year | International Collaboration |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 3.45 |

| 2000 | 25.71 |

| 2001 | 12.90 |

| 2002 | 17.24 |

| 2003 | 19.44 |

| 2004 | 30.30 |

| 2005 | 32.35 |

| 2006 | 30.00 |

| 2007 | 25.00 |

| 2008 | 24.00 |

| 2009 | 45.71 |

| 2010 | 25.81 |

| 2011 | 60.00 |

| 2012 | 45.45 |

| 2013 | 44.83 |

| 2014 | 58.62 |

| 2015 | 25.93 |

| 2016 | 52.00 |

| 2017 | 48.00 |

| 2018 | 46.43 |

| 2019 | 46.15 |

| 2020 | 58.33 |

| 2021 | 50.00 |

| 2022 | 58.46 |

| 2023 | 54.26 |

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Non-citable documents | 1999 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2000 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2001 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2002 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2003 | 7 |

| Non-citable documents | 2004 | 9 |

| Non-citable documents | 2005 | 9 |

| Non-citable documents | 2006 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2007 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2008 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2009 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2010 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2011 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2012 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2013 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2014 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2015 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2016 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2017 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2018 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2019 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2020 | 2 |

| Non-citable documents | 2021 | 11 |

| Non-citable documents | 2022 | 11 |

| Non-citable documents | 2023 | 14 |

| Citable documents | 1999 | 61 |

| Citable documents | 2000 | 74 |

| Citable documents | 2001 | 92 |

| Citable documents | 2002 | 95 |

| Citable documents | 2003 | 88 |

| Citable documents | 2004 | 87 |

| Citable documents | 2005 | 89 |

| Citable documents | 2006 | 101 |

| Citable documents | 2007 | 97 |

| Citable documents | 2008 | 108 |

| Citable documents | 2009 | 123 |

| Citable documents | 2010 | 128 |

| Citable documents | 2011 | 115 |

| Citable documents | 2012 | 95 |

| Citable documents | 2013 | 92 |

| Citable documents | 2014 | 90 |

| Citable documents | 2015 | 90 |

| Citable documents | 2016 | 84 |

| Citable documents | 2017 | 79 |

| Citable documents | 2018 | 75 |

| Citable documents | 2019 | 76 |

| Citable documents | 2020 | 77 |

| Citable documents | 2021 | 103 |

| Citable documents | 2022 | 145 |

| Citable documents | 2023 | 181 |

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Uncited documents | 1999 | 29 |

| Uncited documents | 2000 | 36 |

| Uncited documents | 2001 | 47 |

| Uncited documents | 2002 | 51 |

| Uncited documents | 2003 | 51 |

| Uncited documents | 2004 | 52 |

| Uncited documents | 2005 | 41 |

| Uncited documents | 2006 | 30 |

| Uncited documents | 2007 | 30 |

| Uncited documents | 2008 | 31 |

| Uncited documents | 2009 | 33 |

| Uncited documents | 2010 | 30 |

| Uncited documents | 2011 | 26 |

| Uncited documents | 2012 | 16 |

| Uncited documents | 2013 | 16 |

| Uncited documents | 2014 | 24 |

| Uncited documents | 2015 | 24 |

| Uncited documents | 2016 | 16 |

| Uncited documents | 2017 | 9 |

| Uncited documents | 2018 | 9 |

| Uncited documents | 2019 | 16 |

| Uncited documents | 2020 | 9 |

| Uncited documents | 2021 | 17 |

| Uncited documents | 2022 | 26 |

| Uncited documents | 2023 | 20 |

| Cited documents | 1999 | 32 |

| Cited documents | 2000 | 38 |

| Cited documents | 2001 | 45 |

| Cited documents | 2002 | 44 |

| Cited documents | 2003 | 44 |

| Cited documents | 2004 | 44 |

| Cited documents | 2005 | 57 |

| Cited documents | 2006 | 73 |

| Cited documents | 2007 | 67 |

| Cited documents | 2008 | 77 |

| Cited documents | 2009 | 91 |

| Cited documents | 2010 | 99 |

| Cited documents | 2011 | 90 |

| Cited documents | 2012 | 80 |

| Cited documents | 2013 | 78 |

| Cited documents | 2014 | 68 |

| Cited documents | 2015 | 67 |

| Cited documents | 2016 | 69 |

| Cited documents | 2017 | 72 |

| Cited documents | 2018 | 68 |

| Cited documents | 2019 | 62 |

| Cited documents | 2020 | 70 |

| Cited documents | 2021 | 97 |

| Cited documents | 2022 | 130 |

| Cited documents | 2023 | 175 |

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

| Year | Female Percent |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 41.51 |

| 2000 | 36.11 |

| 2001 | 25.93 |

| 2002 | 34.88 |

| 2003 | 36.49 |

| 2004 | 35.48 |

| 2005 | 30.43 |

| 2006 | 29.87 |

| 2007 | 36.56 |

| 2008 | 35.25 |

| 2009 | 41.67 |

| 2010 | 50.50 |

| 2011 | 39.05 |

| 2012 | 48.11 |

| 2013 | 50.00 |

| 2014 | 46.60 |

| 2015 | 50.82 |

| 2016 | 26.98 |

| 2017 | 55.00 |

| 2018 | 52.27 |

| 2019 | 53.75 |

| 2020 | 42.21 |

| 2021 | 49.79 |

| 2022 | 54.80 |

| 2023 | 50.76 |

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overton | 1999 | 2 |

| Overton | 2000 | 13 |

| Overton | 2001 | 10 |

| Overton | 2002 | 7 |

| Overton | 2003 | 6 |

| Overton | 2004 | 19 |

| Overton | 2005 | 15 |

| Overton | 2006 | 9 |

| Overton | 2007 | 16 |

| Overton | 2008 | 24 |

| Overton | 2009 | 10 |

| Overton | 2010 | 10 |

| Overton | 2011 | 6 |

| Overton | 2012 | 4 |

| Overton | 2013 | 5 |

| Overton | 2014 | 10 |

| Overton | 2015 | 2 |

| Overton | 2016 | 5 |

| Overton | 2017 | 6 |

| Overton | 2018 | 7 |

| Overton | 2019 | 5 |

| Overton | 2020 | 5 |

| Overton | 2021 | 8 |

| Overton | 2022 | 4 |

| Overton | 2023 | 1 |

Evoution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| SDG | 2018 | 2 |

| SDG | 2019 | 5 |

| SDG | 2020 | 9 |

| SDG | 2021 | 8 |

| SDG | 2022 | 13 |

| SDG | 2023 | 13 |

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

Psychology Research Guide

Applied psychology.

Applied psychology is a branch of psychology that includes research to address real-world issues. Areas of applied psychology include business, community, forensic, environment, health, sports, and technology. The following resources can help you narrow your topic, learn about the language used to describe psychology topics, and get you up to speed on the major advancements in this field. To read more about this area of psychology, visit the Office of Applied Psychology on the American Psychological Association website This link opens in a new window . To find ideas for paper/research topics within child & adolescent development, visit these sites:

- Applied Psychology Topics: Education This link opens in a new window

- Applied Psychology Topics: Environment This link opens in a new window

- Applied Psychology Topics: Human Rights This link opens in a new window

- Applied Psychology Topics: Sports and Exercise This link opens in a new window

Applied Psychology Databases

Research in applied psychology utilizes core psychology resources, as well as resources in business, education, the environment, sports, and technology. You may find it helpful to search the following databases for your applied psychology topics or research questions, in addition to the core resources listed on the home page.

Applied Psychology Subject Headings

You may find it helpful to take advantage of predefined subjects or subject headings in Shapiro Databases. These subjects are applied to articles and books by expert catalogers to help you find materials on your topic. Learn more about subject searching:

- Subject Searching

Consider using databases to perform subject searches, or incorporating words from applicable subjects into your keyword searches. Here are some applied psychology subjects to consider:

- emotional health

- health and well-being

- human rights

- interventions

- sports and exercise

Applied Psychology Example Search

Not sure what you want to research exactly, but want to get a feel for the resources available? Try the following searches in any of the databases listed above:

Applied Psych*

(Consumer OR Applied) AND Psych*

There isn't just one accepted word for this area of psychology, so we use OR boolean operators to tell the database any of the listed terms are relevant to our search. We use parenthesis to organize our search, and we stem or truncate the word psychology with the asterisk to tell the database that any ending of the word, as long as the letters psych are at the beginning of the word, will do. This way, the word psychological and other related terms will also be included.

- Learn more about Boolean Operators/Boolean Searching

Applied Psychology Organization Websites

- Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) This link opens in a new window Founded in 1985, the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) is the leading organization for sport psychology consultants and professionals who work with athletes, coaches, non-sport performers (dancers, musicians), business professionals, and tactical occupations (military, firefighters, police) to enhance their performance from a psychological standpoint.

- International Association of Applied Psychology This link opens in a new window Founded in 1920, the International Association of Applied Psychology is the oldest and largest international association of individual members and affiliate international associations. As stated in Article 1 of its Constitution, its mission is: ...to promote the science and practice of applied psychology and to facilitate interaction and communication among applied psychologists around the world.

- Office of Applied Psychology - APA This link opens in a new window APA's Office of Applied Psychology leads the association's efforts for issues related to applied psychology, a branch of the field that uses psychological research, theory, and methods to address real-world issues.

- << Previous: Addictions

- Next: Child & Adolescent Development >>

Search NYU Steinhardt

Research Entities/Labs/Projects

Applied psychology.

Advocacy and Community-Based Trauma Studies (ACTS) Lab

The ACTS Lab is directed by Alisha Ali, Ph.D. Our lab conducts research on treatments and interventions designed to help groups and individuals who have experienced trauma, violence, discrimination, and other forms of oppression. We are currently conducting a series of studies on the DE-CRUIT program which uses techniques from theatre and classical actor training in combination with elements from cognitive and narrative therapy modalities to treat trauma in military veterans. These studies are supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Military Psychology Division of the American Psychological Association, the Humanities Council of New York, and the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.

Chicago School Readiness Project

Launched in 2003, CSRP is a federally-funded randomized control-trial intervention, which included low-income, preschool-aged children living in Chicago. The aim of CSRP is to improve preschool-aged children's chances of success in school. CSRP targets young children's emotional and behavioral adjustment through a comprehensive, classroom-based intervention in Head Start.

CSRP is currently following the children from the original sample through high school, offering a rich opportunity to model children’s trajectories of both their self-regulation and behavioral health from preschool through high school. The study is also exploring the impact of the intervention on college and career readiness.

Chinese Families Lab (CFL)

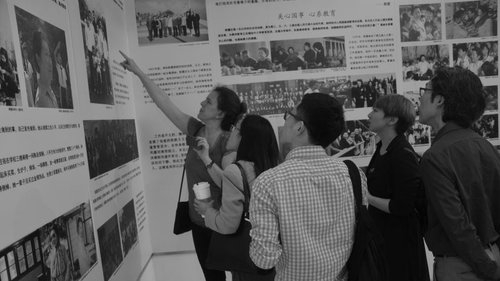

The project draws from both the Nanjing Adolescent and Nanjing MetroBaby study, which are longitudinal, mix-methods studies with over 1100 Chinese families and children starting at 7th grade for the adolescent study and birth for the MetroBaby study. The project is led by Dr. Niobe Way, Dr. Hirokazu Yoshikawa , Dr. Sumie Okazaki, and Dr. Sebastian Cherng from NYU, and is a collaboration across NYU, NYU-Shanghai, NYU-Abu Dhabi, University of Pennsylvania, and Southeast University in China. We are interested in how the changing social, economic, and cultural context influences Chinese parents' parenting practices and children’s development. The project has finished a ten-year follow-up from the MetroBaby project in 2016. Ongoing research papers under development include examining Chinese mothers’ and fathers gender socialization, adolescents' gender beliefs and their academic achievements, gender beliefs and friendship quality, parents' workplace climate and families' mental health, etc.

Strengthening Connections & Opportunities for Learning in and out of Schools

The CONNECT lab at NYU conducts research to understand and strengthen contexts for learning and mental health in low-income education settings. We study natural opportunities for academic, social, and emotional learning via productive relationships and quality interactions.

Using social network approaches, we investigate and enhance connections among children, between children and non-familial adults (educators, practitioners), and among adults who work with youth. We collaborate with school and community partners to activate internal resources to support children with and without behavioral difficulties.

The long-term goal is to increase the likelihood that more young people will have the connections and opportunities they need to succeed in school and life.

The CONNECT lab is led by Dr. Elise Cappella , Associate Professor of Applied Psychology at NYU Steinhardt and Director of the Institute of Human Development and Social Change.

The Culture, Emotion, and Health Lab (CEH)

CEH is directed by William Tsai, Ph.D. The lab studies how people regulate their emotions, cope with stress, and how these processes lead to health and well-being. We focus our research questions on how cultural tendencies and values can shape the development and use of these processes. Our work is interdisciplinary, spanning across social, clinical, and health psychology. Recently, we have begun a line of research with ethnic minority cancer survivors, which is a population that experiences significant cancer health disparities. We are interested in applying cultural psychology theories with psychosocial interventions to overcome cultural barriers to reduce the undue burden of cancer experienced by ethnic minority cancer survivors.

Culture, Families and Early Development (CFD) lab

CFD is directed by Dr. Gigliana Melzi . Our research focuses on family practices and the role these play in young children’s early learning and development. In our scholarship, we adopt a collaborative research stance, working in partnership with families from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Our goal is to identify and understand the unique ways primary caregivers, especially those from Spanish-speaking and Spanish-English bilingual families, support their young children’s early learning at home and at school.

Through our research, we aim to contribute to the current body of knowledge by centering culturally and linguistically diverse families’ voices and perspectives. The priorities of the CFD lab stem from our commitment to address systemic inequities faced by children from minoritized and marginalized communities. Our work focuses on three main areas: Family Literacy Practices, Family STEM Practices, and Family-School Connections.

Exploring People in Context

The E.P.I.C. Lab (Exploring People in Context) is directed by Selçuk Şirin Ph.D., Professor in the Applied Psychology Department at NYU Steinhardt. The primary focus of the lab is to better understand and to enhance the lives of marginalized youth, including immigrant-origin children in New York, Muslim youth in the U.S, refugees in Turkey and Norway, and students at risk in U.S schools. Using empirical methods with development in context as a general framework, our mission is to better understand children’s and families’ needs and to arm professionals and policymakers with this knowledge to better address the needs of the most vulnerable.

The Families and Children Experiencing Success (FACES) Lab

FACES is directed by Anil Chacko, Ph.D . The lab was developed to serve the families of youth exhibiting disruptive behavior disorders such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional-Defiant Disorder, and other conduct disorders. Its research aims to understand how to develop the most effective prevention, intervention, and service models for youth with disruptive behavior disorders and related conditions, or those at high risk for developing them.

Global TIES for Children

NYU Global TIES for Children is an international research center embedded within NYU’s Institute of Human Development and Social Change (IHDSC) and supported by the NYU Abu Dhabi Research Institute and NYU New York. Established in 2014, Global TIES for Children was developed to lead efforts in generating rigorous evidence to support the best and most effective humanitarian and development aid. To date, Global TIES for Children has secured a position at the front lines of advances in methods and measures for assessing child development and for understanding variation in program impacts at multiple levels in low-income and crisis-affected contexts.

The Homeplace Research Collective (Homeplace)

The Homeplace Research Collective (Homeplace), directed by Dr. Lauren Mims, studies the brilliance of Black children and their families through community-engaged, child-centered Black child development research. The Homeplace Research Collective’s name is inspired by a bell hooks essay, “Homeplace (a site of resistance).” In the essay, hooks explains that for African-American people, having a homeplace meant having a place “to restore to ourselves the dignity denied to us on the outside in the public world.

Homeplace in hooks’ articulation and our research collective is a space where Black children and Black families are prioritized, valued, and affirmed. Homeplace is resistance. Homeplace is liberation. Homeplace is “where we can heal our wounds and become whole.”

Home School Connections Research Team

Directed by Dr. Adina Schick , the Home School Connections Team broadly addresses the socio-cultural context of children’s early literacy development, focusing on children from culturally and/or linguistically diverse backgrounds. Our work spans two main areas: (1) ways in which classrooms can incorporate culturally grounded family practices to support children’s school-based learning, and (2) discourse and linguistic features of early literacy home and school interactions, in particular oral storytelling and book sharing between teachers and the children in their classes, as well as between caregivers and children.

The Infant Studies of Language and Neurocognitive Development (ISLAND)

The Infant Studies of Language and Neurocognitive Development, directed by Dr. Natalie Brito is a developmental psychology lab interested in the impact of the social and language environment on early neurocognitive development. The ultimate goal of the lab is to understand how to best support caregivers and create environments that foster optimal child development.

Mindful Education Lab

Housed within the Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, the Mindful Education Lab oversees two parallel but connected programs - research and teacher training. Our Mindful Research Lab looks at the psychological and neurological effects of mindfulness on student learning, teacher effectiveness, and school and classroom climate. This work, in turn, informs our Mindful Teacher Program (MTP), which offers professional development to schools by training educators (teachers, principals, school staff) in techniques to improve their lives both in and out of school. We also train high school students in mindfulness as part of the College Prep Academy, which prepares urban youth for success in college.

Educational interventions developed by Aronson and colleagues have been successful in boosting student achievement, well being, tests scores, and learning, and have been inducted into the Department of Education’s exclusive “What Works Clearinghouse,” a collection of school interventions of carefully vetted practices deemed worthy of using in America’s schools. Dr. Hill is among the nation’s most well respected and influential statisticians and methodologists.

Play & Language Lab

The Play & Language Lab, directed by Catherine Tamis-LeMonda, Ph.D. studies children’s learning and development across the first years of life, with a focus on how social and cultural contexts influence the skills that children acquire and how they engage with their physical and social environments. Our observations of children and parents in structured tasks and the natural setting of their home environments, provide us with rich video records for detailed coding of children, caregivers, and context.

The Project for the Advancement of our Common Humanity (PACH)

PACH is directed by Niobe Way, Ph.D . PACH is an emerging think tank, funded by the NoVo Foundation and based at New York University, that is designed to engage researchers, policymakers, practitioners, activists, educators, artists, and journalists in a series of conversations focused on what we have learned from science and practice regarding what lies at the root of our crisis of connection and what we can do to create a more just and humane world. Presently, PACH entails a public lecture series and monthly conversations with 50 senior-level professionals.

The Purpose Learning Action Young Children Lab (playLab)

The playLab is directed by Jennifer Astuto, Ph.D. Their research designed to engage in the rigorous and socially responsible scientific examination of play in young children’s lives. We utilize randomized control designs, multilevel modeling, interviews and ethnographic methods to explore the unique context of play in promoting school readiness, learning and civic engagement for children who are growing up in poverty and/or are from immigrant families. By cultivating strong partnerships with the communities we work in, we generate empirically-driven knowledge that is culturally relevant and socially just. The playLab strives to produce actionable research and develop collaborations that are used to empower and strengthen the lives of young children through education and policy.

The Researching Inequity in Society Ecologically (RISE)

RISE is directed by Erin Godfrey, Ph.D., and Shabnam Javdani, Ph.D . The team’s research and activities serve traditionally marginalized populations, focusing on health and mental health disparities in women and youth who are involved, or at risk of involvement, with the justice system. As such, the RISE Team takes a contextual, multi-level and interdisciplinary approach to systems change and implementing evidence-based practices promoting health and well-being, working closely with community partners to bridge the gap between research and practice.

SAFE Spaces: Systems Aligning For Equity

Developed in partnership with the NYC Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), SAFE Spaces uses evidence-based principles to provide training and coaching support for frontline staff working in ACS Close to Home (CTH) non-secure and limited-secure placement facilities.

Through unique skills-based staff training activities and guidance from a trained coach, SAFE Spaces aims to increase the professional development, job satisfaction, retention, and well-being in CTH staff who work directly with youth. By focusing on these staff outcomes and the environment in which they work, we also help to promote and encourage a healthier environment for youth’s lives and promote their safety, well-being and positive development. The efficacy of SAFE Spaces is being assessed through a cluster-randomized control trial supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH).

SMART Beginnings

The SMART Beginnings project tests a comprehensive approach to the promotion of school readiness in low-income families, beginning shortly after the birth of the child, through enhancement of positive parenting practices (and when present, reduction of psychosocial stressors) within the pediatric primary care platform. We do so by integrating two evidence-based interventions: 1) a universal primary prevention strategy (Video Interaction Project [VIP]); and 2) a targeted secondary/tertiary prevention strategy (Family Check-up [FCU]) for families identified as having additional risks. Drs. Pamela Morris-Perez (NYU) , Alan Mendelsohn (NYU School of Medicine), and Daniel Shaw (University of Pittsburgh) have received support and funding for this project from the National Institutes of Health.

Strengthening the Architecture for High Quality Universal Pre-K (NYU UPK)

Since 2014, senior leaders in education research and practice at both New York University and the NYC Department of Education Division of Early Childhood Education (DOE-DECE) have fostered a research-practice partnership to support roll out of universal pre-kindergarten through Pre-K For All improving the quality of its programming. The purpose of this partnership is to provide quantitative and capacity-building solutions to educational problems faced by the DOE-DECE.

Case Study Research Method in Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. Typically, data is gathered from various sources using several methods (e.g., observations & interviews).

The case study research method originated in clinical medicine (the case history, i.e., the patient’s personal history). In psychology, case studies are often confined to the study of a particular individual.

The information is mainly biographical and relates to events in the individual’s past (i.e., retrospective), as well as to significant events that are currently occurring in his or her everyday life.

The case study is not a research method, but researchers select methods of data collection and analysis that will generate material suitable for case studies.

Freud (1909a, 1909b) conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

This makes it clear that the case study is a method that should only be used by a psychologist, therapist, or psychiatrist, i.e., someone with a professional qualification.

There is an ethical issue of competence. Only someone qualified to diagnose and treat a person can conduct a formal case study relating to atypical (i.e., abnormal) behavior or atypical development.

Famous Case Studies

- Anna O – One of the most famous case studies, documenting psychoanalyst Josef Breuer’s treatment of “Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) for hysteria in the late 1800s using early psychoanalytic theory.

- Little Hans – A child psychoanalysis case study published by Sigmund Freud in 1909 analyzing his five-year-old patient Herbert Graf’s house phobia as related to the Oedipus complex.

- Bruce/Brenda – Gender identity case of the boy (Bruce) whose botched circumcision led psychologist John Money to advise gender reassignment and raise him as a girl (Brenda) in the 1960s.

- Genie Wiley – Linguistics/psychological development case of the victim of extreme isolation abuse who was studied in 1970s California for effects of early language deprivation on acquiring speech later in life.