Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

- Full Catalog

- 1.877.585.2029

- Digital Curriculum for Middle & High School

- Digital Curriculum Career Ready Program

- Virtual Internship Program

- Knowledge Matters High School Simulations

- Knowledge Matters College Case Simulations

- Learning Blade for Middle Grades

- Ready for Industry Adult Education

- Greenways K-12 Academy

- Instructional Services

- Texas Proclamation 2024

- Summer School & Camps

- Equity & Access

- Career and Technical Education

- Industry Certifications

- STEM Careers

- Financial Literacy

- Employability Skills

- Testimonials

- Empowered Educators Program

- Educator of the Year Awards

- Student Scholarships – Sim Challenges

- Webinars & Events

- Publications & White Papers

- Free Lesson Activities

- Course Placement Resources

- Curriculum Teacher Resources

- Curriculum Student Resources

- Latest News

- State Specific Info

- General Support

Creative Writing: Unleashing the Core of Your Imagination

Writing can change the world. Think about the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and Lincoln’s 2nd In Augural Address. How have these writings shaped our country and the future? While you learn how to unleash the core of your imagination to develop your own creative writing, you’ll also explore creative writing through foundational literary works from the 18th to 20th century of Colonialism to American Gothic to Modernism, and everything in between, while evaluating original writings and their interpretations.

Units at a Glance

Unit 1: Starting the Path to Creative Writing

Do you ever feel words or stories inside your mind, swirling around like unspoken dreams looking for an escape? Creative writing is a medium for finding a release of imagination and tapping into your inner world as a writer. However, unlike closing your eyes and dreaming, effective writing that welcomes the reader in takes real work and ability. There are so many different topics to write about and so many methods to use, putting pen to paper or fingers to keyboard can feel overwhelming. But, as Shakespeare once said, “There is a method to the madness.” In this unit, you will begin to identify different types of creative writing—such as fiction, poetry, and nonfiction—and learn how you can begin to find your place in the wide, vivid world of creative writing.

What will you learn in this unit?

- Analyze how an author’s craft can create such effects as mystery, tension, or surprise.

- Analyze how an author uses source material in a specific work to illuminate a theme.

- Distinguish between genres of creative writing.

- Understand the history and origins of creative writing.

Unit 2: Finding Your Creative Light

Have you ever watched a frantic moth batter itself against a light bulb? Although there is surely a scientific reason behind this phenomenon, all we really know is that they are drawn to the light; they are so attracted to it, they will never stop seeking its warmth. Creativity is a bit like that-it is the source of what makes beauty and meaning in the world. It is the light at the center of everything because it offers a way to make sense of our feelings and experiences in a manner that communicates a bit of ourselves to the outside world. Artistic people find it impossible to live without creativity, and those less inclined are still enraptured by its power. As a society, we have always been drawn to the light-filled energy of creation, whether it be through art, music, innovation, drama, or writing – it sustains us. But in order to capture the essence of this force, there must first be inspiration – a muse, idea, or experience that emboldens us to find an outlet for our feelings. As a creative writer, you must learn how to access your own creativity and identify ways to inspire yourself. Finding your personal style and voice are just a few of the first steps in this journey.

- Understand how language functions in different contexts and how to make effective word choices.

- Recognize the importance of an author’s voice and how it affects tone and style.

- Engage in the act of free writing and journaling for inspiration.

- “Mine” for ideas from various places.

Unit 3: Fiction First

If you doubt the complexity of characterization, just sit on a park bench for a few minutes and observe the different people walking by. They are men, women, children, short, lanky, slumped, limber, old, vibrant, sluggish, distracted. Honestly, the list goes on forever. There are so many details to observe about each and every person, and so much going on in their heads that can’t be seen, it’s almost overwhelming. Every human walking by you is a complex character sketch just waiting to be described. When it comes to crafting a fictional person, there’s barely any need to look outside the real world. If you’ve ever devoured a book, you know that the people within the pages are often the most meaningful part of the story and highly essential to its overall effect. Characters are the lifeblood of fiction. Let’s think more deeply about building characters and what it takes to bring them to life in your own writing.

- Analyze how language contributes to characterization.

- Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of language.

- Describe how a theme or central idea runs through a text and develops over time.

- Understand the characteristics of fiction and its literary elements.

- Determine the strategies necessary when crafting effective characters.

Unit 4: A Fictional Place

Close your eyes and imagine your all-time favorite place, not just how it looks but how it feels . For some reason, certain locations just seem to exude a definite feeling, whether it is in real life or in the pages of a book. “Some reason” is not as cryptic as it sounds; it depends on the mastery and creativity of the writer behind the scene. A room is not just a room. Seen through the eyes of a writer, it can be gloomy with tattered furniture, brightly lit with dingy walls, or wallpapered with a roaring fire; all of these atmospheres relay the expectation of a certain experience. Places have character . Just as we discussed the importance of characterization in fiction, we must also examine the purpose and value of setting. It is the backdrop that adds texture and depth to what the characters are doing. It has the power to affect the very heart of any story and influence the tapestry of one’s imagination. Sounds like a pretty fascinating place, but what does a compelling, effective setting really look like?

- Analyze how a writer unfolds a series of ideas, events, or descriptions to enhance setting.

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases in stories, including the use of figurative language.

- Examine how a writer’s creative choices affect the tone and mood of the story.

- Understand the importance of a fictional setting and how it influences other literary elements.

Unit 5: Speech in Writing

The art of writing will require you to capture that voice inside your head and bring it to life on paper. If you’ve ever sat staring at a blank page, you know that’s sometimes easier said than done. Even more perplexing, how do you create written work that’s meant to capture the voice of someone else? Someone who is a character in your piece with an entirely different set of life circumstances, background, even race or gender? Writing dialogue presents a new layer of challenges because, as the writer, you need to essentially write in an “out loud” voice, one that is decidedly not your own. This type of precision writing also applies to another type of composition called “sketch writing,” where the entire storyline plays out quickly in a dramatic snippet. Because both dialogue and sketch writing requires a writer to accomplish certain structural goals within a short period of time, being succinct is key. In this unit, we will be focusing our attention (and our writerly abilities) on the art of being concise and learning how to create the phenomenon of fictional speech. Rather than simply describing a fictional scene with language, our challenge will be to fill the fictional mouths of characters with the right words for the job. You thought impersonation was tricky–this takes it to a whole new level!

- Analyze how characters develop over the course of a story.

- Understand the purpose and approach to writing effective dialogue.

- Utilize the strategies of writing a sketch story.

- Examine how dialogue is an integral part of both fiction and screenwriting.

Unit 6: When Truth Meets Imagination

There’s an old saying that “truth is stranger than fiction.” Just because something is not entirely made up does not mean it lacks originality or creative flair. Writers of fiction must draw deeply from their imaginary wells to create well-rounded characters, tight action, and intense scenes. You might be surprised that in some cases, nonfiction writers also use these same skills to write great stories. We tend to think of nonfiction as a place for “nothing but the truth,” and when something is all about the facts, we might be tempted to think it’s boring. But there is a type of cross-over literature known as creative nonfiction that takes the fiction writing skills you’ve been studying and applies them to stories and events that have actually happened. The motto of Creative Nonfiction , the main magazine for this genre, describes the genre as “true stories well told.” Nonfiction is a powerful, authentic medium aimed at edifying the reader in addition to entertaining them. When people share their knowledge and background through creative nonfiction, the world becomes a clearer, more understandable place filled with possibility. Through this unit, we will learn exactly how the genre of creative nonfiction can be used in different ways to share findings, explore topics, and strengthen and structure your own narrative.

- Determine how an author uses point of view to attain certain goals.

- Recognize and understand the various areas of creative nonfiction.

- Analyze how certain details within the text shape and refine the overall message.

- Identify how to treat facts and truths when creating a narrative.

Unit 7: Finding Your Inner Poet

Not all writing is the same. As a creative person, you probably have different goals for your work and ways of expressing yourself. As writers, we are always looking for just the right words to illustrate what’s happening in our hearts and minds. There may be times when we just want to dig deeper and bring forth the wonder and profundity of the human experience. Poetry allows us to focus on our writing at the word level. It opens a meaningful exploration not only of time and place, but the considerable emotions and impressions that reside there. A poet doesn’t just write about the wind, the poem becomes the wind. As a writer, exploring the secrets of poetry can add tremendous value to your creative writing repertoire.

- Analyze and define the way a subject can vary depending on how it is told.

- Determine how and where details are emphasized in various accounts.

- Identify how poetry can access significant ideas through imagery and other literary devices.

- Understand the key strategies of poetic structure.

Unit 8: Revision and Purpose

There is one unique element to writing that is not present in a lot of other art forms: revision. Without it, prose would suffer greatly from lack of clarity, meaning, and structure because as much as we hate to admit it, our first words are not always our best. Through a variety of methods, writers develop many skills for how they can “revisit” their work and see it with new eyes, objectively, and with the intent to make it stronger and more effective. Although they may not admit it,there is unlikely to be an author who doesn’t go through it on some level. The point is: Revision is a stepping stone to the larger goal of publishing or at least reaching a point of satisfaction with the final result. Writing that has consumed part of your heart and soul should see the light of day, right? It deserves to be appreciated by others and validated as meaningful on some level, so let’s explore some ways you can employ revision in your writerly life and possibly seek the golden ring of being published.

- Explain the difference between a revision and a critique.

- List several approaches to revision that allow you to see your first draft with more objectivity.

- Explain what professional expectations there are for the different types of writing-related careers.

- Demonstrate the purpose and process of drafting and editing.

Required Materials

- Word or similar document software

We Recommend These Companion Courses

Privacy Overview

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Garrett Moore

Cognition, and the cognitive processes which allow for and produce creativity, is much broader than any one skill such as language. Rather it is an integration of all of a person’s sensory systems. The words that creative writing students craft for their audiences paint a picture in their minds, a private movie that only they can see. Imagine then, how much richer such stories would be for the audience, if we took full advantage of our knowledge about cognition, that it is embodied and entwined in all of our sensory motor engagements, and applied it to how we teach creative writing students. To do so requires changing up how we typically teach creative writing, based on an understanding of cognition and cognitive processes. The very nature of the writing process, of putting words on a page, would seem to be antithetical to the idea of integrating additional sensory information into what the students learn. But if we break away from the idea of the writing process being bound to just words on a page, we may find that there is much to be gained from doing so.

When you read a creative writing piece, it is like the writer is placing a movie right into your head through the words on a page. So let us take that one step further, and see if we can make the next generation of creative writers, and the stories that they craft, something truly like an experience out of a blockbuster movie.

Kesteren, M. T., & Meeter, M. (2020). How to optimize knowledge construction in the brain. Npj Science of Learning, 5(1). doi:10.1038/s41539-020-0064-y

Kleinknecht, E. (2020). Educational psychology week 1 Wednesday [PowerPoint slides]. Moodle@PacU. https://sso.pacificu.edu/cas/login?service=https%3A%2F%2Fmoodle.pacificu.edu%2Flogin%2FFinde.php

Kleinknecht, E. (2020). Educational psychology week 1 Friday [PowerPoint slides]. Moodle@PacU. https://sso.pacificu.edu/cas/login?service=https%3A%2F%2Fmoodle.pacificu.edu%2Flogin%2FFinde.php

Kleinknecht, E. (2014, January 18). Embracing Embodiment. Cognitioneducation. https://cognitioneducation.me/2014/01/18/embracing-embodiment/ .

Kleinknecht, E. (2012, February 24). Labels on the Brain. Cognitioneducation. https://cognitioneducation.me/2012/02/24/labels-on-the-brain/

Setting the Stage: A Guidebook for Optimizing Learning Contexts Copyright © 2020 by Garrett Moore is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

CREATIVE WRITING

Take your writing to soaring new heights. explore the various styles of writing with imagination and creativity.

Monthly themes such as narrative, expository, and non-fiction help students delve into various writing styles effectively and thoroughly. In Creative Writing classes, students are encouraged to become confident writers who can master the planning, preparation, and final completion of their pieces. The aim is to nurture independent writers who can start shaping their unique voices and effectively convey their ideas through written prose.

AI + Writing

These experiments set out to explore whether machine learning could be used by writers to inspire, unblock and enrich their process.

Read the blog post about the experiment and how to build machine learning tools for writers.

Experiments

Once upon a lifetime, between the lines.

Visit our sister organization:

THE LEARNING CURVE

a magazine devoted to gaining skills and knowledge.

THE LEARNING AGENCY LAB ’S LEARNING CURVE COVERS THE FIELD OF EDUCATION AND THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING. READ ABOUT METACOGNITIVE THINKING OR DISCOVER HOW TO LEARN BETTER THROUGH OUR ARTICLES, MANY OF WHICH HAVE INSIGHTS FROM EXPERTS WHO STUDY LEARNING.

How To Teach Writing To Anyone

- March 19, 2020

Writing is a key skill. The ability to put words down on paper is a critical skill for success in college and career, but few students graduate high school as proficient writers. Less than a third of high school seniors are proficient writers, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Low-income, and Black and Hispanic students fare far worse and less than 15 percent scoring proficient.

So how can students learn to write better? What tools do they need to become better at making an argument on paper? In this document, we’re largely focused on argumentative writing, which is central to, well, just about every aspect of modern life, from emails to workplace memos to empowered citizens.

Teaching argumentative writing involves teaching both argumentation and writing. This means there’s research on how to teach writing, there’s research on how to teach argumentation, and there’s research on the intersection of the two.

Earlier research in this topic often referred to it as “persuasive” writing. More recent research seems to prefer and use the term “argumentative” writing. One reason why is that “argumentative” is seen as a broader term. Persuasion is a particular goal that argumentative writing might have. But argumentative writing is seen to encompass many possible goals: persuasion, but also analysis, collaborative problem-solving, and conceptual clarity.

Main takeaways

There are important nuances further below, but the general picture of best practice based on experimental and quasi-experimental research looks something like the following:

- Students need sufficient foundational skills and knowledge (in spelling, typing, content-specific knowledge) and may be taught some of this knowledge in the course of writing . This means that educators in early grades should work on building basic skills in hand-writing, spelling, and typing, and that educators in later grades spend some time focusing on sentence-building skills and incorporate content learning into writing assignments.

- Students benefit from a writing environment where they write and edit frequently using word processing software on long pieces of writing that generate student interest. Although students in early grades may by predominantly writing by hand, as they move on to late elementary school and middle school they should transition to typing, which enables more rapid editing. Although work on basic transcription and sentence-building skills is vital, educators also need to assign longer pieces of work as students progress.

- Students benefit from clear writing purposes and from having well-defined goals for improvement. This suggests that educators choose writing assignments that have larger purposes beyond simply being submitted for a grade—student writing that is published, displayed, or otherwise shared can improve student motivation. It also suggests that educators carefully structure the revision process. For instance, revision goals like “come up with two more reasons in favor of your argument and one reason in favor of an opposing argument” help students meaningfully revise their papers.

- Students benefit from instruction on models of good and bad writing, and through explicit strategies in the writing process: for example, pre-writing techniques, ways of organizing the material, making their reasoning explicit. Educators must correct misperceptions of what writing that focus on the product of writing (instead of the process). And they must be explicit about the strategies that good writers use to ultimately create solid writing.

- Students benefit from guidance in genre-specific practices (for instance, diagrams that help students “fill out” both sides of an argument, character sheets that help students flesh out the characters in their narratives, etc.). Educators can’t assume that skill in one genre of writing will necessarily transfer to others; students have to be taught about the expectations and norms of the writing community.

- Students benefit from collaborating with each other: editing, receiving feedback, and editing again, or even working in groups to co-write material. Providing feedback to others seems to provide as much or more benefit to writing skill as editing one’s own paper. Educators should focus on teaching students how to edit judiciously and provide feedback in a supportive way.

Learning to Write

There is also an increasing recognition of the discipline- and genre-specific nature of writing. It’s not about teaching a single, relatively discrete skill — “writing” — but about teaching ways writing in science , ways of writing in history , ways of writing in literature. Writing in any genre is not a fully transferable skill—it requires contextual knowledge (about the purpose and the audience of the work), content knowledge (about the subject of the work), and writing process knowledge.

Methods and Approaches

Experimental and quasi-experimental work in this area has been the subject of many meta-analyses, with slightly differing emphases. These are fairly comprehensive quantitative summaries of the work in this area, but a substantial number of the underlying studies have methodological problems of one sort or another: e.g., no random assignment, no controlling for the Hawthorne effect, no measures of whether the intervention was implemented with fidelity, or simply no descriptions of the control condition.

More recent studies tend to be of higher quality, and also result in higher effect sizes than older studies (suggesting that earlier studies may have been understating the effect of some of the proposed interventions).

Meta-analyses look at broad swaths of different studies and group studies into categories to be able to calculate the effects of individual types of interventions. These categories are not always mutually exclusive. For instance, the distinction between “writing process” models (which focus on the process of writing — prewriting, organizing, drafting, editing, revising, etc.), “self-regulation” models (which focus on setting writing goals and teaching students to monitor their writing and editing to achieve those goals), and “peer writing” models (where student co-write and edit each others work) can overlap substantially. In other cases, single categories encompass quite a diverse set of practices. For instance, the “strategy instruction” model includes interventions involving pre-writing activities, peer writing, persuasive writing structures, etc.

Another complexity is how writing outcomes are measured. Rubric-based instruction may help students improve their writing when measured by the rubric, but not necessarily when evaluated through other means.

Research evaluating the popular 6+1 trait writing model, for example, shows little improvement in student outcomes when those outcomes are not measured with the 6+1 writing rubric.

Main Takeaways About Learning To Write

Teachers don’t assign enough writing..

The survey’s results, however, suggest some improvements in teacher practice compared to 40 years ago. Compared to an assessment made in 1979-80, teachers are giving students more questions that ask for more original analysis, they’re incorporating more research-backed strategies like process writing, explicit strategy instruction, and collaborative writing in the curriculum, and they use technology more often.

These findings dovetail with another recent large-scale survey of 361 high school teachers across several disciplines. Again, the main finding is that students don’t compose texts that are long enough (most writing practice asks students to compose texts one-paragraph in length or less), and that few writing assignments as students for analysis and interpretation. Moreover, most teachers say they are not prepared to teach writing (71% say they had either no or minimal college-level training in the subject in their teacher preparation programs).

Although experts argue that argumentative writing should happen across all disciplines, English teachers have often shouldered the main responsibility for teaching writing skills of all sorts (at least as judged by the surveys mentioned earlier). This emphasis, however, clashes with a tradition of emphasizing the literary tradition in English language arts classes (e.g., fiction and narrative), rather than argumentation. One way of providing students with more opportunities to write is to have teachers across many disciplines assign writing tasks. This has been a common aim of several reforms.

Time and expertise seem to be the main obstacles to teachers assigning more writing. Teacher workloads are high, while providing meaningful feedback on long pieces of writing takes considerable effort. Teachers report simply not having enough time to assign long pieces of writing, provide feedback on them, and providing lots of opportunities for revision.

Many teachers also report not being very confident in their ability to teach writing, not having the training or experience to teach writing well, or both. This lack of expertise (or at least lack of confidence) also likely discourages teachers from assigning more challenging pieces of writing.

Research has also revealed a number of best practices. The following best practices all improve student outcomes, and are listed in approximate order of effect size (largest to smallest) based on several recent meta-analyses of existing studies

Explicit strategy instruction helps students.

That said, authors of the survey view the overall amount of class time spent on research-backed strategies to be insufficient: for instance, about 3 minutes out of every 50 minute English class period would be devoted to one of the most support strategies—explicit writing strategy instruction.

Teachers should illustrate each strategy and facilitate students’ independent use of each strategy over time. For instance, a pre-writing activity like brainstorming might be initially presented to the students: the teacher can explain what the strategy is, why writers do it, and present a model of the practice to students. Then, the teacher would have students practice brainstorming in small groups, with occasional teacher guidance. After that, students would brainstorm on their own, while the teacher would provide occasional support. Finally, the teacher would encourage students to use brainstorming completely independently (revisiting aspects of the strategy if needed).

Self-regulation strategies can improve outcomes.

The most popular self-regulation strategy is the SRSD (self-regulation and strategy development) model. This integrates both explicit strategy instruction and self-regulation strategies into a classroom context. Teachers don’t just introduce a strategy—they track student progress towards mastery in using the strategy over time, aiming to motivate students and build self-confidence. The SRSD approach uses mnemonics, graphic organizers, and other scaffolds, in addition to developing prior knowledge about specific writing genres as students are taught them. Evidence suggests that the program is one of the most effective classroom programs, but outcome measures stop short of long trajectories (stopping at six months).

Process Writing improves student outcomes. Process writing involves getting students involved in pre-writing, organizing, drafting, revising, re-drafting, and editing their papers. It’s about engaging students in a relatively long-term writing process involving multiple drafts, rounds of peer and/or teacher feedback, and a finalized product. It’s also helpful to have students explain why they made their edits.

Process writing seems to be a key part of many successful writing interventions (such as SRSD), but the evidence on the efficacy of process writing alone is somewhat contradictory.

Most meta-analyses that evaluate process writing as a separate category of intervention find that process writing is a best practice and has substantial effect sizes. This effect, however, seems modulated by professional development — when teachers are not taught how to use process writing approaches effectively, the benefit disappears. A meta-analysis that focused solely on process writing found modest effects for students of average ability, but no significant effects on writing outcomes for struggling writers, which contrasts with qualitative research suggesting the benefits of process writing for struggling writers in particular. Many of the studies in the process-writing-specific meta-analysis also had weak study designs making the claim that process writing doesn’t help struggling writers at best preliminary.

Feedback Drives Achievement.

For feedback to be effective, students must be motivated to use feedback to improve and they must know how to use the feedback effectively. The first is a challenge of classroom culture. The second is a challenge of student knowledge.

Surveys suggest that many students feel like they don’t have enough guidance on what to do with the feedback they receive. One study at the undergraduate level suggests that the main factor influencing whether students implemented changes based on feedback was whether the problem described by the feedback was understood. Problem understanding increased when teachers identified where the problem was, proposed some solutions, and gave a summary of the students’ work.

Even generic automated feedback to scientific arguments can improve students subsequent arguments (e.g., feedback that reads something like “You haven’t provided enough evidence for your argument. You should add more evidence.” The effects, however, were most pronounced for students that had high scores to begin with, suggesting that receptiveness to feedback may also be playing a role.

One of the values of outside feedback (from either peers or teachers) is that students are more likely to make deeper, meaning-related changes in response to outside feedback than they are when making individual revisions.

Peer Collaboration Can Make A Difference.

Peer feedback offers several proposed benefits . Students often perceive peer feedback as more understandable (and therefore, more actionable) than teacher feedback. Students often feel that teacher feedback is insufficient or unhelpful, and, in higher education at least, students report that peers provide more (and more helpful) feedback. Peer feedback is also a way of providing more overall feedback to students (on early or intermediate drafts of a piece of writing, for instance), as it requires less teacher time. Some reports even suggest that peer feedback encourages students to redouble their efforts because of the social pressure to do well on the assignment.

There are, however, also some challenges to peer feedback. Peers can offer valuable feedback, but it’s not quite up to the standards of expert feedback. For instance, in a study where peers used a predefined assessment guideline, peer and expert feedback was structurally comparable, although peers suggested fewer changes, gave more positive judgments and gave less evidential support for their negative judgments.

Another challenge is to develop a classroom culture where feedback is perceived to be helpful and non-threatening. In one study , English Language Learners report liking peer feedback, but also being concerned about hurting their partners feelings or lacking enough knowledge to be helpful. In that study, students preferred online forms of feedback over face-to-face feedback.

Teaching students how to give valuable feedback is a critical step. Not only does this make the peer feedback more valuable for the writer, but it also helps the peer reviewer develop their own revision skills. For instance, a teacher might give peer reviewers some questions to guide their revision process. Questions like: Is the piece suitable for the intended audience—does it use the right tone, the right kinds of vocabulary words and text complexity? Is the overall structure of the argument clear? Etc.

In some cases, learning to provide peer feedback seems to have more benefits to students than receiving feedback. In a study from 2009, one group of students gave feedback on written work throughout the semester while the other group received feedback. Both groups improved over the course of the semester, but the givers improved more than the receivers when they had no prior experience in giving peer feedback.

Foundational skills and knowledge enable students to engage deeply with the material.

Students also need to know genre-specific writing structures and topic-specific vocabulary. For instance, young children have a better understanding of the narrative genre compared to other genres of writing (argumentative writing, scientific reports, poems). When students don’t know enough about the genre expectations, they can’t produce work that’s recognizably within the genre (e.g., when asked for a science report or an argument, they might produce something that’s more like a story).

Genre learning is something that continues throughout careers and later schooling (e.g., imagine learning about the “business case” genre, the “legal memo” genre or the “economic theory paper” genre); it’s part of the overall development of meta-cognitive knowledge. Explicitness about genre expectations also helps marginalized groups (who may not be as familiar with the genres they’re asked to produce) participate more fully.

Word processing lets students edit and revise more easily.

The commonly accepted explanation is that word processing makes editing and organizing a paper easier, and so encourages revision.

Although seventy-five percent of teachers report having students turn in their final draft through a computer, less than half of students use word processing for drafting, editing, and collaborating on written work. This is particularly notable given the presumed mechanism behind the advantage of using word processors over paper-and-pencil to draft and edit: word processors make editing and re-organizing far easier.

More Frequent Practice. Perhaps the simplest intervention that seems to improve writing outcomes is more practice (especially given the evidence on the little amount of practice that students typically get at long-form writing). Establishing writing routines (for example, having students write for fifteen minutes more a day than they currently do) and ensuring that the writing tasks are interesting to students — that the writing has some larger relevance or purpose — seem like important keys to having students write more.

Multiple drafts improve essay quality.

Writing can also improve reading..

Researchers have proposed several explanations for the deep relationship between reading and writing. They both involve common processes. Spelling, for example, helps students read and write. Sentence-combining helps students write complex sentences and comprehend more complex sentences. The writer also has to re-organize what she’s read, leading to deeper reflection of the material. And finally, writing provides insight into what a writer might be thinking, which helps students interpret written work.

Evaluations of programs that integrate reading and writing programs show positive writing outcomes. These programs typically involve professional development and peer collaboration on reading and writing assignments. Part of the explanation may be that reading helps students anticipate what readers may believe as they write. Reading texts that students will write about also increases their prior knowledge of the issues.

Grammar instruction is important but not that helpful for more advanced writers.

Research on common practices among exceptional writing teachers largely complement or confirm the best practices listed above. Exceptional teachers:

- Are excited about teaching writing, making it clear to students that they enjoy the subject and enjoy teaching the subject.

- Publish student work by sharing it with others, displaying it on walls, or publishing it in collections.

- Encourage students to try hard and attribute success to effort (a component of the SRSD approach).

- Reinforce classroom routines that help students progress along the writing process (peer editing, co-writing, revising, etc.) (a component of process writing and peer writing)

- Have high but realistic expectations (a component of the SRSD approach).

- Adapt writing assignments to student needs and interests.

- Use activities that encourage deep processing (critiquing ideas about their papers) as opposed to shallow processing (filling out a worksheet that can be filled out mindlessly).

- Encourage students to do as much as possible on their own. (a component of the SRSD approach)

Still, Some Open Questions About Learning to Write

For instance, at what age should students begin formulating structured arguments (either through discussion, as preparation for later writing assignments, or in writing itself)? Under certain contexts, even young children can reason well, which suggests that early, more comprehensive practice could substantially improve student reasoning in the long term. But there are also developmental considerations. There’s relatively little evidence on this question.

What’s the proper role of writing rubrics? Rubrics can help students set goals and perceive differences between their work and an ideal piece of writing. But such rubrics can become formulaic substitutes for deep engagement with the issues.

How should argument-structuring scaffolds be used? There’s little doubt that argument diagrams can help students formulate counter-arguments and rebuttals, and that they help lower-ability students in particular. Whether the benefits of such scaffolds extend beyond the assignments that use the scaffolding, however, is an open question: in some transfer tasks, students who have been using argument diagrams don’t write any better arguments than those who haven’t. They can, however, also limit reformulations and of the argument by making the issue seem “black and white” as opposed to “gray” and promote linear, less open approaches, particularly for higher ability students. How to fade these scaffolds over the long trajectory of student development is largely unexplored.

How should we be evaluating written argumentation skills? Researchers have used a variety of methods to distinguish “good” essays from “bad” essays, but the diversity of measurement approaches makes it challenging to compare studies. Articulating counter-arguments has been a major focus, but so have measures of elaboration and organizational structure. In some cases, it’s difficult to tell what aspect of the essays have improved because the descriptions are simply too vague.

What are interesting cases and authentic contexts for students in different classroom settings? A big hurdle for teaching written argumentation seems to be engagement. Students who feel that the writing has some larger purpose (and have some relevant experience) produce stronger written arguments, and presumably become better arguers because of it. But, as far as I can tell, there is no collection of vetted cases across the variety of classroom situations (and levels of prior knowledge) that teachers encounter.

Successful writing intervention programs involve extensive professional development, but what kinds of professional development is best, and how should successful professional development programs be scaled?

Are there other complexities to teaching students with learning disabilities that haven’t surfaced because of lack of research? The research on teaching writing to students with learning disabilities is particularly sparse. A relatively recent review of the research (2009) found only 9 studies that met their inclusion criteria for a total of 31 students.

- Ulrich Boser

8 thoughts on “How To Teach Writing To Anyone”

This is a wonderful article that’s very helpful. I have been assigned to teaching 7th and 8th grade students that have very low lexile levels. These students do not know how to write and they don’t want to learn how to write. So, I’m searching for understanding and resources. I have started with building sentences, you know, writing complete sentences instead of fragments and run-on sentences.

good post, keep it up.

Great work, keep it yp.

nice work, keep it up

GREAT services

Thank you for this. Indeed writing is not a natural skill but one that is built upon. Contact My Homework Writers for help on writing should you feel you need that extra hand.

The skill of writing is a very important for everyone to excel in!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Build Your Own Summer EdVenture Through Personalized Summer Camps & Programs For Your Child!

Creative Writing

Strong writers are often more successful in all aspects of life. LifeReader’s Creative Writing package is meant to help students develop their creative writing skills by crafting their own blog. Students will also be given the opportunity to submit their work in multiple writing contests and create a personal portfolio.

8 th -12 th grade; Minimum of 3 students; 10 group sessions

The official news and events source for the University of Indianapolis

Filter results:

Writing Lab Celebrates 40 Years of Building Better Writers

May 13, 2024 in Campus News

Written by Troi Watts

The Writing Lab at the University of Indianapolis celebrated its 40th anniversary this year.

Founded in 1983 under the leadership of Richard M. Marshall, the Writing Lab supports UIndy students through individualized tutoring at any stage of the writing process, from brainstorming topics to fine tuning a final draft. While a lot has changed since its inception, the goal of the Writing Lab remains the same: to produce better writers.

“We always need good writers,” said Rebecca McKanna , interim director of the Writing Lab. “Students may not realize how much room there is for them to grow as writers until they get into some of their college courses.”

“Writing is meant to be collaborative,” added Dawn Hershberger, associate director of the Writing Lab. “We always tell people it’s not like Stephen King pops out a book and it goes right on the shelf without going through editing and lots of other revisions. Writing is a process, no matter where you think your strengths lie, or don’t lie in that process. You can benefit from having another set of eyes on your work, and from talking about your writing. That’s really the Writing Lab’s main function.”

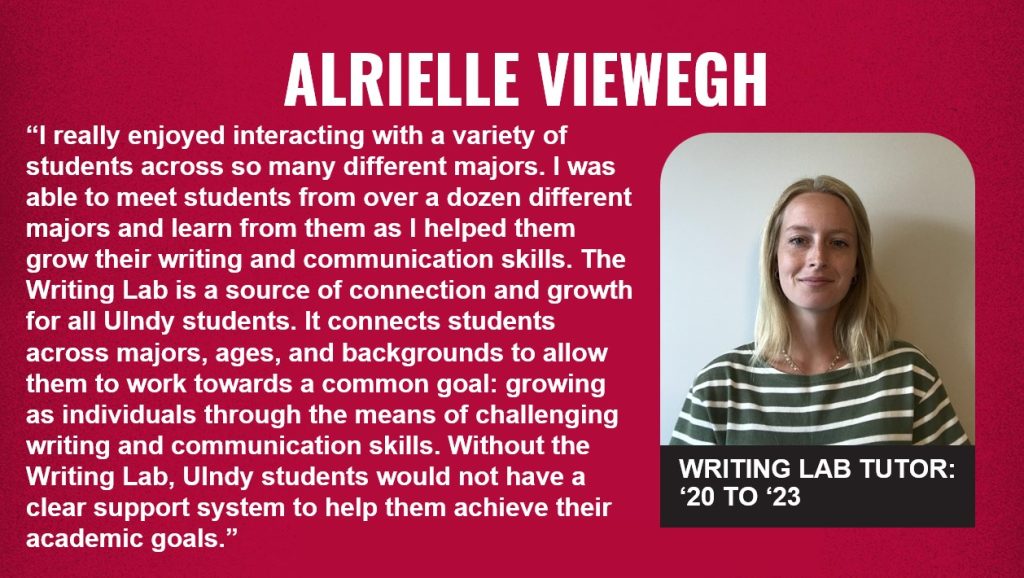

Unlike other university writing centers, the Writing Lab at UIndy is staffed by tutors from a variety of programs in addition to English, including biology, nursing, and other STEM-related majors. This allows the Lab to support a wider variety of students working on a variety of writing projects. When requesting an appointment, students can select a tutor from their program or a similar program, to provide a more personalized tutoring experience.

“In the future, I hope that the Writing Lab can reach more students from STEM majors and that it becomes known to those students that we are here for them,” said tutor Annabelle Curylo ‘24 (Biology). “Just because you’re a biology student writing a biology paper doesn’t mean that the Writing Lab can’t help you. We’re not all English majors and you don’t have to come for an English paper.”

The Writing Lab continues to honor its legacy while supporting its future with the establishment of the Richard M. Marshall Tutor of the Year Award. This award recognizes the Writing Lab tutor who went above and beyond to support the Writing Lab. Curylo was the inaugural recipient of this year’s award, presented at the Writing Lab’s 40th Anniversary Celebration.

“Annabelle was always excited about stepping up to fill in for someone or represent the Writing Lab at an event,” said Hershberger. “She’s also one of our assistants to the director. She had more responsibilities than other tutors, and even then she would go above and beyond that. She was really invested in the success of the Writing Lab.”

Today, the Writing Lab proudly staffs 29 tutors, including graduate-level and faculty tutors, to support the campus community. Looking ahead, Hershberger and McKanna hope to continue expanding graduate-level offerings.

While its tutoring services are the primary focus of the Writing Lab, it has also expanded its offerings to build belonging amongst students on campus. For the past decade, the Writing Lab has hosted Conversation Circles, a program of regular meetings for students and community members to come together to practice their English.

“It’s an opportunity for our international students to be able to practice spoken English in a low-stakes situation,” explained Hershberger, who founded the program. “It also gives international students a way to meet other people on campus, and it gives everybody a chance for global exchange.”

In the spirit of collaboration and community building, the Writing Lab plans to partner with the Ron and Laura Strain Honors College to staff designated Honors tutors. These tutors will be Honors students themselves and will provide tutoring specifically for Honors-related projects, such as the required Honors thesis.

These new initiatives highlight McKanna and Hershberger’s favorite part of leading the Writing Lab: working and connecting with their students.

“Rick Marshall created a really special place,” said McKanna. “At the anniversary celebration, we heard from people who were tutors back when the Writing Lab first started, and it was so amazing to hear how it touched their lives.”

You can help the Writing Lab expand its offerings and support even more writers. Give today at https://getinvolved.uindy.edu/writing_lab .

What to Expect at New Hounds Day (New Student Orientation)

Uindy faculty, staff provide expert insight to local & national media in april.

Festivals of Invention and Creativity - FIC Toolkit

Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

Brazilian Creative Learning Network

Festivals of Invention and Creativity (FICs) are local celebrations to share and actively engage in creative learning experiences.

FICs bring together educators, school leaders, students, and families to recognize local talent and foster supportive communities of practice in formal and informal educational settings. Children and adults can explore high and low tech tools and materials as they participate in interactive, hands-on activities. As educators engage in these activities, they have opportunity to explore new ways to foster innovation as an alternative to more traditional education approaches. Teacher designers who share their creative projects gain recognition from colleagues for their efforts to transform the learning opportunities of their students.

Since 2017, the Lifelong Kindergarten, through its Brazilian Creative Learning Network initiative, has been promoting FICs across Brazil, reaching over 96,000 participants in six years. The FIC Toolkit project builds upon this success in Brazil by elaborating on the model for a global audience . The Toolkit includes a set of resources and guides developed in collaboration with partners in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, India, and South Africa to help educators around the world create their own Festivals.

Promoting Creative Learning through Festivals of Invention and Creativity: Building on a Successful Model from Brazil receives support from the Jameel World Education Lab.

Brazilian Creative Learning Network / Aprendizagem Criativa no Brasil

The Brazilian Creative Learning Network (BCLN -- https://aprendizagemcriativa.org/) is a grassroots movement that promotes and supports the…

Festival of Invention and Creativity

The Festival of Invention and Creativity (FIC) is a great celebration of the inventive, collaborative, and hands-on spirit of B…

In the News

The MIT Bike Lab: A place for community, hands-on learning

Bianca Champenois SM ’22 learned to ride a bike when she was 5 years old. She can still hear her sister yelling “equal elbows!” as she pushed her off into the street. Although she started young, her love of bikes really materialized when she was in college.

Champenois studied mechanical engineering (MechE) at the University of California at Berkeley, but with a first-year schedule comprising mostly prerequisites, she found herself wanting more hands-on opportunities. She stumbled upon BicyCal, the university’s bike cooperative.

“I loved the club because it was a space where learning was encouraged, mistakes were forgiven, and vibes were excellent,” explains Champenois. “I loved how every single bike that came into the shop was slightly different, which meant that no two problems were the same.”

Through the co-op’s hands-on learning experience, the few long rides she took across some of California’s bridges like the Golden Gate, and the lively evening “Bike Parties” drafting behind friends, Champenois’s love for biking continued to grow. When she arrived at MIT for her master’s studies, she joined the cycling team.

Champenois, who is also passionate about climate action, enjoyed the sense of community the cycling team offered, but was looking for something that also allowed her to solve problems and work on bikes again.

After discovering there wasn’t a comparable cooperative bike program at the Institute, Champenois was determined to start one herself. It wasn’t long before she secured club funding from The Coop’s Public Service Grant with the support of her peer, Haley Higginbotham ’21, who was also passionate about the cause. By the end of the year, the team had gained two more volunteers, civil and environmental engineering graduate student Matthew Goss and materials science and engineering grad student Gavin Winter, and the MIT Bike Lab was born.

"The idea is to empower people to learn how to fix their own bike so that they are motivated to use biking as a reliable transportation method," says Champenois. The volunteer mechanic has a vested interest in promoting sustainability and improving urban infrastructure.

Champenois is a graduate student in the joint Mechanical Engineering and Computational Science/Engineering program, and her research involves applying data science and machine learning to fluid dynamics, with a specific focus on ocean and climate modeling. The NSF Graduate Research Fellow is now building upon prior research focused on ocean acidification as part of her PhD thesis, while she is also involved in other projects within Professor Themis Sapsis’s Stochastic Analysis and Nonlinear Dynamics (SAND) Lab .

“I appreciate that my research strikes a balance between more applied environmental projects and more theoretical statistics and computational science,” she explains while referencing a recent research contribution to a project focused on improving global climate simulations.

Champenois’s academic research focus may be specific, but she stresses that the Bike Lab isn’t targeted to any particular interest and welcomes all who are eager to learn.

“If you're interested in solid mechanics, you can think about bike frames. If you're interested in material science, you can think about brake pads. If you're interested in fluids, you can think about hydraulic brakes,” she says. “I think there's something for everyone, and there's always something to learn.”

In the last year-and-a-half, the Bike Lab is estimated to have serviced over 150 bikes, and they’re only getting started. Champenois is ambitious about the Bike Lab’s future.

“I hope to teach classes, maybe throughout the semester or as a standalone IAP [Independent Activities Period] course. I am also really interested in the idea of managing a vending machine for parts,” states Champenois.

In the winter, the Bike Lab stores its tools in N52-318, but the club lacks the space needed to expand. “Without our own space, it is difficult for us to store parts, which means that people are required to bring their own parts if their repair requires a replacement,” explains Champenois.

While physical space isn’t required to build a sense of community, Champenois envisions the Bike Lab exuding the same sort of camaraderie as the Banana Lounge , another of one MIT’s student-run spaces, one day.

“I like to think of the Bike Lab as more than just a bike shop. It's also a place for community,” she says.

Champenois hopes to complete her degree in the next year or two and would like to become a professor someday. She is excited by a career in academia, but she says she could also see herself working on a climate or weather research team or joining an ocean technology startup.

Many have heard the expression that being a student at MIT is like “drinking from a firehose,” but that is one of the things Champenois will miss most when she leaves.

“I have had the opportunity to discover so many new hobbies and been able to learn so much through sponsored activities,” she recalls. “Most importantly, I'll miss the great people I have met. Everyone at MIT is so curious and hardworking in a way that is truly energizing.”

Related News

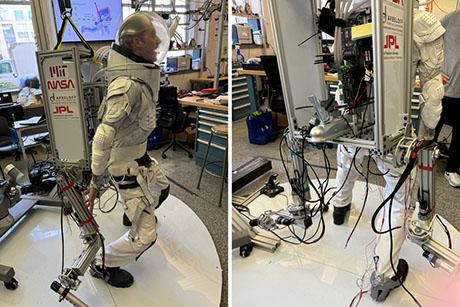

Robotic “SuperLimbs” could help moonwalkers recover from falls

How light can vaporize water without the need for heat

Content Tags

- Fee Payment

- PARENT PORTAL LOGIN

How Do I Make Writing Fun for My Kindergarten Child?

Writing is a fun activity which requires your child to exercise creativity and delve into his or her imagination.

At the kindergarten levels, students are introduced to stories through storytelling or picture books.

They tend to interpret the meaning of a story with the aid of visuals (pictures) and sounds (the story being read aloud to them). This results in them quickly picking up the ability to verbally share their own stories and recounts.

However, when it comes to writing, they often struggle to put their ideas and thoughts into words or full sentences.

Furthermore, being able to structure a story can prove difficult for these young learners — especially without guiding pictures or helping phrases.

What are some of the main challenges preschoolers face when writing stories? What can you do to make the writing process more fun and exciting for your child? Sue Lynn Lee, our Academic Director for the Early Years and lower primary programmes, addresses your concerns in this article.

Top Challenges Students Face When Writing a Story and How Your Child Can Overcome Them

Based on our years of experience in teaching, some of the top challenges that preschool students struggle with when it comes to writing are:

- They are unable to think of ideas for a storyline

- They find it difficult to express themselves in writing

- They struggle to arrange their points logically or chronologically

- They are unable to spell the words they want to use

- They use the wrong punctuation or grammar in sentences.

Although most preschool children may find it a struggle at times, there are ways to get around the challenges they face to bring out the fun in writing.

To help your child with some of these challenges, here are some of Ms Lee's recommendations.

Get Inspiration from Books

Firstly, your child may find writing tough if they are unable to come up with sufficient ideas for their stories. This is similar to writer’s block and usually comes about when students do not have enough exposure to stories or plots.

To help your child with this, you can read more storybooks together to expose him or her to as many creative storylines as possible.

While watching television may be frowned upon at times, exposure to healthy kids' programmes can also help children overcome their “writer’s block”.

You can also try having conversations with your child about his or her favourite stories or books that he or she is already familiar with. Children have a lot of fun imagining a different ending or imagining what happens when the villain triumphs at the end of the story.

Start with Bite-sized Writing Exercises

One other struggle that takes the fun out of writing is having too many ideas and stories to share, but being unable to express them in writing.

This usually happens when your child can't pen his or her thoughts in a clear and coherent manner. If your child faces this problem, remember not to inhibit his or her creativity.

Children can be encouraged to first share their stories verbally before being tasked to start writing a short part of it.

They could choose to write their favourite part, the most exciting part, or even just the conclusion of the story as a bite-sized writing exercise. Encouraging preschoolers to use drawings to put their thoughts onto paper before getting them to write about their ideas could work too.

Encourage Your Child to Verbalise His or Her Thoughts

Then comes the problem of creating a logical storyline.

Many children struggle with putting their story together in a logical manner, especially if they wish to write about multiple occurrences within the same story. Their interesting ideas then slowly evolve into an unrealistic and illogical plot.

Again, remember not to discourage your child by pointing this out.

Over time, you can help your child improve on this by speaking to him or her more about the little events that happen in school or during family outings. This helps your child learn to describe events logically, as they would have happened in real life.

Try this simple activity at home. Get your child to arrange the sequence of a series of pictures that form a story.

This builds their ability to rationalise logic flow and gaps. We have put together a special guide to help your child with this.

Download this fun guide to hone your child's writing skills from the comfort of home.

Get Creative with Spelling

Children often feel discouraged with writing when they struggle with spelling.

Learning to spell accurately will take time, especially as your child's vocabulary expands. It should not be something that holds him or her back in using a certain word in a story.

At the kindergarten level, it is okay for your child to use his or her own spelling when writing stories, as long as you share how each word is supposed to be spelled afterward.

Help Your Child with Grammar and Punctuation

Lastly, we should not nitpick on too many grammar and punctuation errors in their writing.

These mistakes are very common for preschool children and can take the fun out of writing if they are pointed out too often.

Similar to spelling, learning to use proper grammar and phrasing will take time, so encourage your child to continue writing in spite of these mistakes.

This builds their ability in descriptive writing. When reading storybooks with them, draw their attention to the use of full stops in the story. When writing with them, encourage them to use short sentences and to put a full stop at the end of every “idea” that they come up with.

Find out more about our English programmes here.

The Learning Lab is now at 8 locations . Find a location that suits your needs.

If you have any questions about our programmes, please email us at [email protected] or call us at 6733 8711 and we will be happy to assist you.

Recent Posts

Find Out More about Our Programmes

- Get Started

Learning Lab Collections

- Collections

- Assignments

My Learning Lab:

Forgot my password.

Please provide your account's email address and we will e-mail you instructions to reset your password. For assistance changing the password for a child account, please contact us

You are about to leave Smithsonian Learning Lab.

Your browser is not compatible with site. do you still want to continue.

- Yekaterinburg

- Novosibirsk

- Vladivostok

- Tours to Russia

- Practicalities

- Russia in Lists

Rusmania • Deep into Russia

Out of the Centre

Savvino-storozhevsky monastery and museum.

Zvenigorod's most famous sight is the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, which was founded in 1398 by the monk Savva from the Troitse-Sergieva Lavra, at the invitation and with the support of Prince Yury Dmitrievich of Zvenigorod. Savva was later canonised as St Sabbas (Savva) of Storozhev. The monastery late flourished under the reign of Tsar Alexis, who chose the monastery as his family church and often went on pilgrimage there and made lots of donations to it. Most of the monastery’s buildings date from this time. The monastery is heavily fortified with thick walls and six towers, the most impressive of which is the Krasny Tower which also serves as the eastern entrance. The monastery was closed in 1918 and only reopened in 1995. In 1998 Patriarch Alexius II took part in a service to return the relics of St Sabbas to the monastery. Today the monastery has the status of a stauropegic monastery, which is second in status to a lavra. In addition to being a working monastery, it also holds the Zvenigorod Historical, Architectural and Art Museum.

Belfry and Neighbouring Churches

Located near the main entrance is the monastery's belfry which is perhaps the calling card of the monastery due to its uniqueness. It was built in the 1650s and the St Sergius of Radonezh’s Church was opened on the middle tier in the mid-17th century, although it was originally dedicated to the Trinity. The belfry's 35-tonne Great Bladgovestny Bell fell in 1941 and was only restored and returned in 2003. Attached to the belfry is a large refectory and the Transfiguration Church, both of which were built on the orders of Tsar Alexis in the 1650s.

To the left of the belfry is another, smaller, refectory which is attached to the Trinity Gate-Church, which was also constructed in the 1650s on the orders of Tsar Alexis who made it his own family church. The church is elaborately decorated with colourful trims and underneath the archway is a beautiful 19th century fresco.

Nativity of Virgin Mary Cathedral

The Nativity of Virgin Mary Cathedral is the oldest building in the monastery and among the oldest buildings in the Moscow Region. It was built between 1404 and 1405 during the lifetime of St Sabbas and using the funds of Prince Yury of Zvenigorod. The white-stone cathedral is a standard four-pillar design with a single golden dome. After the death of St Sabbas he was interred in the cathedral and a new altar dedicated to him was added.

Under the reign of Tsar Alexis the cathedral was decorated with frescoes by Stepan Ryazanets, some of which remain today. Tsar Alexis also presented the cathedral with a five-tier iconostasis, the top row of icons have been preserved.

Tsaritsa's Chambers

The Nativity of Virgin Mary Cathedral is located between the Tsaritsa's Chambers of the left and the Palace of Tsar Alexis on the right. The Tsaritsa's Chambers were built in the mid-17th century for the wife of Tsar Alexey - Tsaritsa Maria Ilinichna Miloskavskaya. The design of the building is influenced by the ancient Russian architectural style. Is prettier than the Tsar's chambers opposite, being red in colour with elaborately decorated window frames and entrance.

At present the Tsaritsa's Chambers houses the Zvenigorod Historical, Architectural and Art Museum. Among its displays is an accurate recreation of the interior of a noble lady's chambers including furniture, decorations and a decorated tiled oven, and an exhibition on the history of Zvenigorod and the monastery.

Palace of Tsar Alexis

The Palace of Tsar Alexis was built in the 1650s and is now one of the best surviving examples of non-religious architecture of that era. It was built especially for Tsar Alexis who often visited the monastery on religious pilgrimages. Its most striking feature is its pretty row of nine chimney spouts which resemble towers.

Plan your next trip to Russia

Ready-to-book tours.

Your holiday in Russia starts here. Choose and book your tour to Russia.

REQUEST A CUSTOMISED TRIP

Looking for something unique? Create the trip of your dreams with the help of our experts.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

P3 Creative Writing. While not intended as examination preparation, Creative Writing is designed to teach students the fundamentals of good story writing. This includes having a good plot with a climax, as well as using literary devices to add interest to their stories. Students get to write around their favourite genre, which will help ...

Mission. The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives.

In creative writing, this usually comprises an introduction, climax and conclusion. For argumentative essays, it will likely involve a stand, pointers for or against a statement, as well as a rebuttal strategy. This ensures that the introduction connects with its following paragraphs cohesively. A clear overview also helps to confirm that you ...

This collection was created to accompany the Cultivating Learning session, Inspiring Creative, Narrative, and Argumentative Writing with Art, facilitated by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Smithsonian Office of Educational Technology. In the interactive session, educators model transferrable techniques through three distinct ...

Creative writing is a medium for finding a release of imagination and tapping into your inner world as a writer. However, unlike closing your eyes and dreaming, effective writing that welcomes the reader in takes real work and ability. ... (and our writerly abilities) on the art of being concise and learning how to create the phenomenon of ...

30 likes, 1 comments - thelearninglab on May 3, 2024: " Dive into the deep sea of creative writing with Volume 2 of The Learning Lab's collection of exemplary essays written by our very ...". The Learning Lab | 🌊 Dive into the deep sea of creative writing with Volume 2 of The Learning Lab's collection of exemplary essays written by our ...

Creative writing is, by its very nature, a process of learning. Students who take creative writing classes learn proper grammar and syntax uses, the details of composition, and how to write in a way that is engaging to the audience. ... Transform the writing lab into a sensation, perception, and writing lab. One where sensory experiences, motor ...

Pre-Phonics. Phonics. Writing & Grammar

Creative Learning Revising and Polishing Your Work: Tips from Professional Writers Revising and polishing your work is an essential step in the writing process.

AI + Writing. These experiments set out to explore whether machine learning could be used by writers to inspire, unblock and enrich their process. ... by Google Creative Lab . Chat to your character while you write them. Overview. Once Upon A Lifetime. by Google Creative Lab . Once Upon A Lifetime helps you explore options for a character's ...

Process writing involves getting students involved in pre-writing, organizing, drafting, revising, re-drafting, and editing their papers. It's about engaging students in a relatively long-term writing process involving multiple drafts, rounds of peer and/or teacher feedback, and a finalized product.

Here are 5 tips from The Learning Lab that will help you improve your writing and your chance at an A for the General Paper. 1. Read the Questions Carefully. You get a total of 12 questions to choose from for your GP essay. Take a moment to read all of them carefully. While you should choose a topic that you are familiar with or passionate ...

Explore different styles of writing in response to American art! This digital collection suggests artworks from the Smithsonian American Art Museum to use to inspire creative, narrative, and argumentative writing, along with suggested thinking routines and writing prompts.

Why Learning Lab? Gateway Academy; Test Prep; Tutoring; LifeCore; Assessment; Events; Articles; Careers; Contact Us; Search for: Nashville: 615-321-7272 Brentwood: 615-377-2929. ... LifeReader's Creative Writing package is meant to help students develop their creative writing skills by crafting their own blog. Students will also be given the ...

Writing Center. The Writing Center (located in the library) offers help on any kind of writing, from essays to lab reports, creative writing to cover letters. Drop-in anytime we're open to work with the peer Writing Coaches on brainstorming a topic, creating an outline, structuring a draft, checking for grammar mistakes, or properly citing your sources.

10K Followers, 50 Following, 1,232 Posts - The Learning Lab (@thelearninglab) on Instagram: "Get a head start for 2024 🏻Class registration 👨👩👦👦 Must-read articles for parents" ... 🌊 Dive into the deep sea of creative writing with Volume 2 of The Learning Lab's collection of exemplary essays written by our very own ...

The Writing Lab at the University of Indianapolis celebrated its 40th anniversary this year. Founded in 1983 under the leadership of Richard M. Marshall, the Writing Lab supports UIndy students through individualized tutoring at any stage of the writing process, from brainstorming topics to fine tuning a final draft.

According to the Poetry Foundation, "An ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art. Through the imaginative act of narrating and reflecting on the "action" of a painting or sculpture, the poet may amplify and expand its meaning". This collection is based on a lesson plan from the Smithsonian American Art ...

Festivals of Invention and Creativity (FICs) are local celebrations to share and actively engage in creative learning experiences.FICs bring together educators, school leaders, students, and families to recognize local talent and foster supportive communities of practice in formal and informal educational settings.Children and adults can explore high and low tech tools and materials as they ...

MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering (MechE) offers a world-class education that combines thorough analysis with hands-on discovery. One of the original six courses offered when MIT was founded, MechE faculty and students conduct research that pushes boundaries and provides creative solutions for the world's problems.

Writing is a fun activity which requires your child to exercise creativity and delve into his or her imagination. At the kindergarten levels, students are introduced to stories through storytelling or picture books. They tend to interpret the meaning of a story with the aid of visuals (pictures) and sounds (the story being read aloud to them).

Keywords: NCTE, National Writing Day, creative writing Describe Your Collection: take a minute to help others find and use what you made By adding or enhancing your collection description and adding information about its subject(s), age levels, educational features, and standards alignments, you can help other Smithsonian Learning Lab users ...

Zvenigorod's most famous sight is the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery, which was founded in 1398 by the monk Savva from the Troitse-Sergieva Lavra, at the invitation and with the support of Prince Yury Dmitrievich of Zvenigorod. Savva was later canonised as St Sabbas (Savva) of Storozhev. The monastery late flourished under the reign of Tsar ...

Elektrostal. Elektrostal ( Russian: Электроста́ль) is a city in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It is 58 kilometers (36 mi) east of Moscow. As of 2010, 155,196 people lived there.

Animals and Pets Anime Art Cars and Motor Vehicles Crafts and DIY Culture, Race, and Ethnicity Ethics and Philosophy Fashion Food and Drink History Hobbies Law Learning and Education Military Movies Music Place Podcasts and Streamers Politics Programming Reading, Writing, and Literature Religion and Spirituality Science Tabletop Games ...

Unit Paid Faculty teach additional courses on an as needed basisThe University of Virginia's Department of English/Writing and Rhetoric Program seeks qualified applicants to teach first-year undergraduate writing, usually ENWR 1510, a one-semester course that fulfills the College of Arts and Sciences' writing requirement offered each fall, spring, and summer. A master's degree in rhetoric ...

Dmitriy V. Mikheev, Karina A. Telyants, Elena N. Klochkova, Olga V. Ledneva; Affiliations Dmitriy V. Mikheev