- Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Evidence Synthesis Guide

- Risk of Bias by Study Design

Evidence Synthesis Guide : Risk of Bias by Study Design

- Review Types & Decision Tree

- Standards & Reporting Results

- Materials in the Mayo Clinic Libraries

- Training Resources

- Review Teams

- Develop & Refine Your Research Question

- Develop a Timeline

- Project Management

- Communication

- PRISMA-P Checklist

- Eligibility Criteria

- Register your Protocol

- Other Resources

- Other Screening Tools

- Grey Literature Searching

- Citation Searching

- Minimize Bias

- GRADE & GRADE-CERQual

- Data Extraction Tools

- Synthesis & Meta-Analysis

- Publishing your Review

Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

““Assessment of risk of bias is a key step that informs many other steps and decisions made in conducting systematic reviews. It plays an important role in the final assessment of the strength of the evidence.” 1

Risk of Bias by Study Design (featured tools)

- Systematic Reviews

- Non-RCTs or Observational Studies

- Diagnostic Accuracy

- Animal Studies

- Qualitative Research

- Tool Repository

- AMSTAR 2 The original AMSTAR was developed to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews that included only randomized controlled trials. AMSTAR 2 was published in 2017 and allows researchers to identify high quality systematic reviews, including those based on non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions. more... less... AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews)

- ROBIS ROBIS is a tool designed specifically to assess the risk of bias in systematic reviews. The tool is completed in three phases: (1) assess relevance(optional), (2) identify concerns with the review process, and (3) judge risk of bias in the review. Signaling questions are included to help assess specific concerns about potential biases with the review. more... less... ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews)

- BMJ Framework for Assessing Systematic Reviews This framework provides a checklist that is used to evaluate the quality of a systematic review.

- CASP Checklist for Systematic Reviews This CASP checklist is not a scoring system, but rather a method of appraising systematic reviews by considering: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What are the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Systematic Reviews JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- RoB 2 RoB 2 provides a framework for assessing the risk of bias in a single estimate of an intervention effect reported from a randomized trial, rather than the entire trial. more... less... RoB 2 (revised tool to assess Risk of Bias in randomized trials)

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trials Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of an RCT that require critical appraisal: 1. Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? 2. Was the study methodologically sound? 3. What are the results? 4. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CONSORT Statement The CONSORT checklist includes 25 items to determine the quality of randomized controlled trials. Critical appraisal of the quality of clinical trials is possible only if the design, conduct, and analysis of RCTs are thoroughly and accurately described in the report. more... less... CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- ROBINS-I ROBINS-I is a tool for evaluating risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness… of interventions from studies that did not use randomization to allocate units to comparison groups. more... less... ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions)

- NOS This tool is used primarily to evaluate and appraise case-control or cohort studies. more... less... NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale)

- AXIS Cross-sectional studies are frequently used as an evidence base for diagnostic testing, risk factors for disease, and prevalence studies. The AXIS tool focuses mainly on the presented study methods and results. more... less... AXIS (Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies)

- NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools for Non-Randomized Studies The NHLBI’s quality assessment tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. • Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies • Quality Assessment of Case-Control Studies • Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group • Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies more... less... NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Case Series Studies Quality Appraisal Checklist Developed by the Institute of Health Economics (Canada), the checklist is comprised of 20 questions to assess the robustness of the evidence of uncontrolled case series studies.

- Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports In this paper, Dr. Murad and colleagues present a framework for appraisal, synthesis and application of evidence derived from case reports and case series.

- MINORS The MINORS instrument contains 12 items and was developed for evaluating the quality of observational or non-randomized studies. This tool may be of particular interest to researchers who would like to critically appraise surgical studies. more... less... MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools for Non-Randomized Trials JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. • Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies • Checklist for Case Control Studies • Checklist for Case Reports • Checklist for Case Series • Checklist for Cohort Studies

- QUADAS-2 The QUADAS-2 tool is designed to assess the quality of primary diagnostic accuracy studies it consists of 4 key domains that discuss patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow of patients through the study and timing of the index tests and reference standard. more... less... QUADAS-2 (a revised tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Checklist for Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies JBI Critical Appraisal Tools help you assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which study has addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis.

- STARD 2015 The authors of the standards note that essential elements of diagnostic accuracy study methods are often poorly described and sometimes completely omitted, making both critical appraisal and replication difficult, if not impossible. The Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies was developed to help improve completeness and transparency in reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies. more... less... STARD 2015 (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies)

- CASP Diagnostic Study Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of diagnostic test studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- CEBM Diagnostic Critical Appraisal Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance, and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SYRCLE’s RoB Implementation of SYRCLE’s RoB tool will facilitate and improve critical appraisal of evidence from animal studies. This may enhance the efficiency of translating animal research into clinical practice and increase awareness of the necessity of improving the methodological quality of animal studies. more... less... SYRCLE’s RoB (SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation’s Risk of Bias)

- ARRIVE 2.0 The ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines are a checklist of information to include in a manuscript to ensure that publications on in vivo animal studies contain enough information to add to the knowledge base. more... less... ARRIVE 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments)

- Critical Appraisal of Studies Using Laboratory Animal Models This article provides an approach to critically appraising papers based on the results of laboratory animal experiments, and discusses various bias domains in the literature that critical appraisal can identify.

- CEBM Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet The CEBM’s critical appraisal sheets are designed to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence. more... less... CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist This CASP checklist considers various aspects of qualitative research studies including: 1. Are the results of the study valid? 2. What were the results? 3. Will the results help locally? more... less... CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Tool Repository Created by librarians at Duke University, this extensive listing contains over 100 commonly used risk of bias tools that may be sorted by study type.

- Latitudes Network A library of risk of bias tools for use in evidence syntheses that provides selection help and training videos.

References & Recommended Reading

1. Viswanathan, M., Patnode, C. D., Berkman, N. D., Bass, E. B., Chang, S., Hartling, L., ... & Kane, R. L. (2018). Recommendations for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health-care interventions . Journal of clinical epidemiology , 97 , 26-34.

2. Kolaski, K., Logan, L. R., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2024). Guidance to best tools and practices for systematic reviews . British Journal of Pharmacology , 181 (1), 180-210

3. Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1991;302(6785):1136-1140.

4. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

5.. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:225-234.

6. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;366:l4898.

7. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63(8):e1-37.

8.. Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2016;355:i4919.

9. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458.

10. Guo B, Moga C, Harstall C, Schopflocher D. A principal component analysis is conducted for a case series quality appraisal checklist. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2016;69:199-207.e192.

11. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2018;23(2):60-63.

12. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ journal of surgery. 2003;73(9):712-716.

13. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529-536.

14. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5527.

15. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RBM, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14:43.

16. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS biology. 2020;18(7):e3000411.

17. O'Connor AM, Sargeant JM. Critical appraisal of studies using laboratory animal models. ILAR journal. 2014;55(3):405-417.

- << Previous: Minimize Bias

- Next: GRADE & GRADE-CERQual >>

- Last Updated: Aug 30, 2024 2:14 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.mayo.edu/systematicreviewprocess

- Geoffrey R. Weller Library

View complete hours

- Subject Guides

Knowledge Synthesis Guide

- Critical Appraisal

- What is Knowledge Synthesis?

- Developing your question

- Consider Eligibility Criteria

- Grey Literature

- Create Search Terms for Each Concept

- Identify Controlled Vocabulary for Each Concept

- Building Your Search

- Translating a Search Strategy

- Run Your Searches

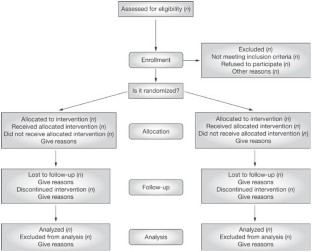

- Reporting Your Results with PRISMA

- Utilize a Screening Tool

- Data Extraction

- Information About Publishing This link opens in a new window

Tools for Critical Appraisal

Critical appraisal is the careful analysis of a study to assess trustworthiness, relevance and results of published research. Here are some tools to guide you.

- JBI Critical Appraisal

- CASP Checklists

- The AACODS checklist

Appraisal Resources - Grey Literature

Appraising Grey Literature:

- Guide to Appraising Grey Literature ( Public Health Ontario)

- << Previous: Utilize a Screening Tool

- Next: Data Extraction >>

- Last Updated: Sep 19, 2024 4:47 PM

- URL: https://libguides.unbc.ca/KnowledgeSynthesis

Geoffrey R. Weller Library University of Northern British Columbia 3333 University Way Prince George, B.C. V2N 4Z9

Circulation: (250) 960-6613 Reference: (250) 960-6475 Regional Services: 1-888-440-3440 (toll free within 250 area code)

- Suggestions Form

- Planning & Policies

- Staff Directory

- Frequently Called Numbers

- Citation Management

- Course Reserves

- Faculty Services

- Interlibrary Loans

- Open Access

- Data & Statistics

- Maps & Photos

- Research Help

Medicine: A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- About this guide

- First Year Library Essentials

- Literature Reviews and Data Management

- Systematic Search for Health This link opens in a new window

- Guide to Using EndNote This link opens in a new window

- A Brief Guide to Critical Appraisal

- Manage Research Data This link opens in a new window

- Articles & Databases

- Point of Care Tools

- Anatomy & Radiology

- Drugs and Medicines

- Diagnostic Tests & Calculators

- Health Statistics

- Multimedia Sources

- News & Public Opinion

Have you ever seen a news piece about a scientific breakthrough and wondered how accurate the reporting is? Or wondered about the research behind the headlines? This is the beginning of critical appraisal: thinking critically about what you see and hear, and asking questions to determine how much of a 'breakthrough' something really is.

The article " Is this study legit? 5 questions to ask when reading news stories of medical research " is a succinct introduction to the sorts of questions you should ask in these situations, but there's more than that when it comes to critical appraisal. Read on to learn more about this practical and crucial aspect of evidence-based practice.

What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal forms part of the process of evidence-based practice. “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” outlines the fives steps of this process. Critical appraisal is step three:

- Ask a question

- Access the information

- Appraise the articles found

- Apply the information

Critical appraisal is the examination of evidence to determine applicability to clinical practice. It considers (1) :

- Are the results of the study believable?

- Was the study methodologically sound?

- What is the clinical importance of the study’s results?

- Are the findings sufficiently important? That is, are they practice-changing?

- Are the results of the study applicable to your patient?

- Is your patient comparable to the population in the study?

Why Critically Appraise?

If practitioners hope to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, practicing in a manner that is responsive to the discoveries of the research community, then it makes sense for the responsible, critically thinking practitioner to consider the reliability, influence, and relevance of the evidence presented to them.

While critical thinking is valuable, it is also important to avoid treading too much into cynicism; in the words of Hoffman et al. (1):

… keep in mind that no research is perfect and that it is important not to be overly critical of research articles. An article just needs to be good enough to assist you to make a clinical decision.

How do I Critically Appraise?

Evidence-based practice is intended to be practical . To enable this, critical appraisal checklists have been developed to guide practitioners through the process in an efficient yet comprehensive manner.

Critical appraisal checklists guide the reader through the appraisal process by prompting the reader to ask certain questions of the paper they are appraising. There are many different critical appraisal checklists but the best apply certain questions based on what type of study the paper is describing. This allows for a more nuanced and appropriate appraisal. Wherever possible, choose the appraisal tool that best fits the study you are appraising.

Like many things in life, repetition builds confidence and the more you apply critical appraisal tools (like checklists) to the literature the more the process will become second nature for you and the more effective you will be.

How do I Identify Study Types?

Identifying the study type described in the paper is sometimes harder than it should be. Helpful papers spell out the study type in the title or abstract, but not all papers are helpful in this way. As such, the critical appraiser may need to do a little work to identify what type of study they are about to critique. Again, experience builds confidence, but understanding the typical features of common study types certainly helps.

To assist with this, the Library has produced a guide to study designs in health research .

The following selected references will help also with understanding study types but there are also other resources in the Library’s collection and freely available online:

- The “ How to read a paper ” article series from The BMJ is a well-known source for establishing an understanding of the features of different study types; this series was subsequently adapted into a book (“ How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine ”) which offers more depth and currency than that found in the articles. (2)

- Chapter two of “ Evidence-based practice across the health professions ” briefly outlines some study types and their application; subsequent chapters go into more detail about different study types depending on what type of question they are exploring (intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, qualitative) along with systematic reviews.

- “ Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning ” unpacks the components of a paper, explaining their purpose along with key features of different study designs. (3)

- The BMJ website contains the contents of the fourth edition of the book “ Epidemiology for the uninitiated ”. This eBook contains chapters exploring ecological studies, longitudinal studies, case-control and cross-sectional studies, and experimental studies.

Reporting Guidelines

In order to encourage consistency and quality, authors of reports on research should follow reporting guidelines when writing their papers. The EQUATOR Network is a good source of reporting guidelines for the main study types.

While these guidelines aren't critical appraisal tools as such, they can assist by prompting you to consider whether the reporting of the research is missing important elements.

Once you've identified the study type at hand, visit EQUATOR to find the associated reporting guidelines and ask yourself: does this paper meet the guideline for its study type?

Which Checklist Should I Use?

Determining which checklist to use ultimately comes down to finding an appraisal tool that:

- Fits best with the study you are appraising

- Is reliable, well-known or otherwise validated

- You understand and are comfortable using

Below are some sources of critical appraisal tools. These have been selected as they are known to be widely accepted, easily applicable, and relevant to appraisal of a typical journal article. You may find another tool that you prefer, which is acceptable as long as it is defensible:

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

- JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute)

- CEBM (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine)

- SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network)

- STROBE (Strengthing the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

- BMJ Best Practice

The information on this page has been compiled by the Medical Librarian. Please contact the Library's Health Team ( [email protected] ) for further assistance.

Reference list

1. Hoffmann T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. 2nd ed. Chatswood, N.S.W., Australia: Elsevier Churchill Livingston; 2013.

2. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley; 2014.

3. Aronoff SC. Translational research and clinical practice: basic tools for medical decision making and self-learning. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- << Previous: Guide to Using EndNote

- Next: Manage Research Data >>

- Last Updated: Sep 16, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/medicine

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

Critical Appraisal tools

Critical appraisal worksheets to help you appraise the reliability, importance and applicability of clinical evidence.

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of clinical research papers in order to establish:

- Does this study address a clearly focused question ?

- Did the study use valid methods to address this question?

- Are the valid results of this study important?

- Are these valid, important results applicable to my patient or population?

If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, you can save yourself the trouble of reading the rest of it.

This section contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples.

Critical Appraisal Worksheets

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostics Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCT) Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies Sheet

- IPD Review Sheet

Chinese - translated by Chung-Han Yang and Shih-Chieh Shao

- Systematic Reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnostic Study Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognostic Critical Appraisal Sheet

- RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

- IPD reviews Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Qualitative Studies Critical Appraisal Sheet

German - translated by Johannes Pohl and Martin Sadilek

- Systematic Review Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Diagnosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Prognosis Critical Appraisal Sheet

- Therapy / RCT Critical Appraisal Sheet

Lithuanian - translated by Tumas Beinortas

- Systematic review appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Diagnostic accuracy appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- Prognostic study appraisal Lithuanian (PDF)

- RCT appraisal sheets Lithuanian (PDF)

Portugese - translated by Enderson Miranda, Rachel Riera and Luis Eduardo Fontes

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Diagnostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Prognostic Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – RCT Study Appraisal Worksheet

- Portuguese – Systematic Review Evaluation of Individual Participant Data Worksheet

- Portuguese – Qualitative Studies Evaluation Worksheet

Spanish - translated by Ana Cristina Castro

- Systematic Review (PDF)

- Diagnosis (PDF)

- Prognosis Spanish Translation (PDF)

- Therapy / RCT Spanish Translation (PDF)

Persian - translated by Ahmad Sofi Mahmudi

- Prognosis (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

- PICO Critical Appraisal Sheet (MS-Word)

- Educational Prescription Critical Appraisal Sheet (PDF)

Explanations & Examples

- Pre-test probability

- SpPin and SnNout

- Likelihood Ratios

CASP Checklists

- How to use our CASP Checklists

- Referencing and Creative Commons

- Online Training Courses

- CASP Workshops

- What is Critical Appraisal

- Study Designs

- Useful Links

- Bibliography

- View all Tools and Resources

- Testimonials

Critical appraisal tools and resources

CASP has produced simple critical appraisal checklists for the key study designs. These are not meant to replace considered thought and judgement when reading a paper but are for use as a guide and aide memoire. All CASP checklists cover three main areas: validity , results and clinical relevance.

What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical Appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context. It is an essential skill for evidence-based medicine because it allows people to find and use research evidence reliably and efficiently.

Learn more about what critical appraisal is, why we need it and more

A complete list (published & unpublished) of articles and research papers about CASP and other critical appraisal tools and approaches, covering from 1993-2012.

- CASP Checklist

Need more information?

- Online Learning

- Privacy Policy

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) will use the information you provide on this form to be in touch with you and to provide updates and marketing. Please let us know all the ways you would like to hear from us:

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

Copyright 2024 CASP UK - OAP Ltd. All rights reserved Website by Beyond Your Brand

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Critical Appraisal Tools and Reporting Guidelines for Evidence-Based Practice

Affiliations.

- 1 Professor, School of Nursing & Health Professions, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- 2 Reference Librarian and Primary Liaison, School of Nursing & Health Professions, Gleeson Library, Geschke Center, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA.

- PMID: 28898556

- DOI: 10.1111/wvn.12258

Background: Nurses engaged in evidence-based practice (EBP) have two important sets of tools: Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines. Critical appraisal tools facilitate the appraisal process and guide a consumer of evidence through an objective, analytical, evaluation process. Reporting guidelines, checklists of items that should be included in a publication or report, ensure that the project or guidelines are reported on with clarity, completeness, and transparency.

Purpose: The primary purpose of this paper is to help nurses understand the difference between critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines. A secondary purpose is to help nurses locate the appropriate tool for the appraisal or reporting of evidence.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted to find commonly used critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for EBP in nursing.

Rationale: This article serves as a resource to help nurse navigate the often-overwhelming terrain of critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines, and will help both novice and experienced consumers of evidence more easily select the appropriate tool(s) to use for critical appraisal and reporting of evidence. Having the skills to select the appropriate tool or guideline is an essential part of meeting EBP competencies for both practicing registered nurses and advanced practice nurses (Melnyk & Gallagher-Ford, 2015; Melnyk, Gallagher-Ford, & Fineout-Overholt, 2017).

Results: Nine commonly used critical appraisal tools and eight reporting guidelines were found and are described in this manuscript. Specific steps for selecting an appropriate tool as well as examples of each tool's use in a publication are provided.

Linking evidence to action: Practicing registered nurses and advance practice nurses must be able to critically appraise and disseminate evidence in order to meet EBP competencies. This article is a resource for understanding the difference between critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines, and identifying and accessing appropriate tools or guidelines.

Keywords: critical appraisal tools; evidence-based nursing; evidence-based practice; reporting guidelines.

© 2017 Sigma Theta Tau International.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Differences Between Magnet and Non-Magnet-Designated Hospitals in Nurses' Evidence-Based Practice Knowledge, Competencies, Mentoring, and Culture. Melnyk BM, Zellefrow C, Tan A, Hsieh AP. Melnyk BM, et al. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2020 Oct;17(5):337-347. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12467. Epub 2020 Oct 6. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2020. PMID: 33022875

- Endorsement and Validation of the Essential Evidence-Based Practice Competencies for Practicing Nurses in Finland: An Argument Delphi Study. Saunders H, Gallagher-Ford L, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Saunders H, et al. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019 Aug;16(4):281-288. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12377. Epub 2019 Jun 4. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2019. PMID: 31162823

- Evidence-Based Practice Competencies for RNs and APNs: How Are We Doing? Bell SG. Bell SG. Neonatal Netw. 2020 Aug 1;39(5):299-302. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.39.5.299. Neonatal Netw. 2020. PMID: 32879046

- Facilitating interprofessional evidence-based practice in paediatric rehabilitation: development, implementation and evaluation of an online toolkit for health professionals. Glegg SM, Livingstone R, Montgomery I. Glegg SM, et al. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(4):391-9. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1041616. Epub 2015 Apr 29. Disabil Rehabil. 2016. PMID: 25924019 Review.

- A systematic review of how studies describe educational interventions for evidence-based practice: stage 1 of the development of a reporting guideline. Phillips AC, Lewis LK, McEvoy MP, Galipeau J, Glasziou P, Hammick M, Moher D, Tilson JK, Williams MT. Phillips AC, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2014 Jul 24;14:152. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-152. BMC Med Educ. 2014. PMID: 25060160 Free PMC article. Review.

- Exploring measurement tools used to assess knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pregnant women toward prenatal screening: A systematic review. Sacca L, Zerrouki Y, Burgoa S, Okwaraji G, Li A, Arshad S, Gerges M, Tevelev S, Kelly S, Knecht M, Kitsantas P, Hunter R, Scott L, Reynolds AP, Colon G, Retrouvey M. Sacca L, et al. Womens Health (Lond). 2024 Jan-Dec;20:17455057241273557. doi: 10.1177/17455057241273557. Womens Health (Lond). 2024. PMID: 39206551 Free PMC article.

- Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Song D, Hightow-Weidman L, Yang Y, Wang J. Song D, et al. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2024 Jan-Dec;23:23259582241275819. doi: 10.1177/23259582241275819. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2024. PMID: 39155592 Free PMC article.

- Promoting patient-centered care in CAR-T therapy for hematologic malignancy: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Xie C, Duan H, Liu H, Wang Y, Sun Z, Lan M. Xie C, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2024 Aug 16;32(9):591. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08799-3. Support Care Cancer. 2024. PMID: 39150486 Free PMC article. Review.

- Clinical Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Interventions. Hogg HDJ, Martindale APL, Liu X, Denniston AK. Hogg HDJ, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024 Aug 1;65(10):10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.65.10.10. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024. PMID: 39106058 Free PMC article. Review.

- Acceptability, Effectiveness, and Roles of mHealth Applications in Supporting Cancer Pain Self-Management: Integrative Review. Wu W, Graziano T, Salner A, Chen MH, Judge MP, Cong X, Xu W. Wu W, et al. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024 Jul 18;12:e53652. doi: 10.2196/53652. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024. PMID: 39024567 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Searching with critical appraisal tools

Glasofer, Amy DrNP(c), MSN, RN, ONC

Amy Glasofer is a senior educator for Virtua Center for Learning in Mt. Laurel, N.J.

CATs help journal club members rate the quality of research

The author has disclosed that she has no financial relationships related to this article.

Nurses rank feeling unable to judge the quality of research as one of the greatest hurdles to using research in practice. Participation in a journal club improves members' ability to critically appraise the quality of research.

Critical appraisal is “the process of assessing and interpreting evidence by systematically considering its validity, results and relevance to an individual's work.” 1 Nurses rank feeling incapable of assessing the quality of research as one of the greatest barriers to using research in practice. 2 Participation in a journal club (JC) can improve members' abilities to critically appraise the quality of research. 3,4 The use of a formalized critical appraisal tool (CAT) during JC facilitates improvement in appraisal skills. 3,4 The purpose of this article is to review the literature on selecting a CAT.

Literature review

CATs are designed to help readers rate the quality of research. 5 In reference to research, quality is the extent to which a study has minimized biases in the selection of subjects and measurement of outcomes, as well as minimized influence of anything outside of the factors being studied on the results. 6 CATs are superior to informal appraisal in bringing readers with different levels and types of knowledge to a similar conclusion about a research paper. 5 Their utility in a JC seems obvious; however, selecting a CAT isn't a simple task.

As a component of the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999, Congress charged the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) with developing methods to ensure that reviews of healthcare literature are scientifically and clinically sound. 6 To fulfill this charge, the AHRQ commissioned a study to describe systems that rate the quality of evidence and to provide guidance on best practices. This report analyzed over 120 published CATs. 6 The AHRQ review, and others published since, have come to the same conclusions: there's no “gold standard” CAT for any specific study design, there's no generic tool that can be applied equally across study designs, and users of CATs should be careful about the CAT they select and how they use it. 6–8

The AHRQ developed standard categories that any CAT should address to adequately rate specific research designs (see AHRQ critical rating categories for CATs by research design ). 6 Based on these criteria, they put forth 19 recommended CATs depending on research design (see AHRQ recommended CATs ). Aside from being potentially outdated, the AHRQ-recommended CATs may be difficult to use in a nursing JC. Although different research designs require varying criteria for appraisal, it would be simpler to use CATs of similar formats across designs. Additionally, the CATs put forth by the AHRQ aren't inclusive of some forms of research and nonresearch evidence that JCs might wish to cover, including qualitative research, meta-synthesis, clinical practice guidelines, consensus or position statements, literature reviews, expert opinions, organizational experience, or case reports. 28 Lastly, all of the CATs recommended by the AHRQ were developed for appraising medical literature. These tools may not translate easily for use in a nursing JC.

Selecting our CAT

For these reasons, the JC at our institution opted to evaluate additional CATs. One of the JC facilitators who was completing her doctoral coursework took on this task. Several resources were utilized including searching academic databases and the Internet, and consulting with mentors and evidence-based practice texts. Ultimately, the CATs selected for our JC came from the Johns Hopkins Model for Evidence Based Practice. 28 This reference contains two tools for appraising individual articles. The first is for appraising research evidence (randomized control trials, quasi-experimental studies, nonexperimental studies, qualitative studies, systematic reviews, and systematic reviews with meta-analysis or meta-synthesis). All of the categories considered critical for systematic reviews, randomized control trials, and observational studies by the AHRQ are covered in this CAT, with the exception of assessing for funding or sponsorship. The AHRQ allowed for the absence of funding criteria in recommended CATs as this category was so often not addressed. 6 The second Johns Hopkins CAT is for evaluating nonresearch articles. 28 There's less guidance available for evaluating a nonresearch CAT. However, the Johns Hopkins tool is based on established criteria for appraising nonresearch evidence. 28–30

There are some limitations to the Johns Hopkins CATs. First, the research appraisal tool applies a single set of questions across multiple research designs and depends on the user to determine if the question is appropriate. The AHRQ cautioned that utilizing such a generalized tool could weaken the analysis. Although our JC had received education on critical appraisal and the use of the tools, members did struggle initially with determining which questions applied to the study they were critiquing. As they grew more comfortable with the CAT, with various research designs, and with research terminology, JC members did become more fluent with utilizing the tool. Additionally, the research appraisal tool doesn't contain the AHRQ-recommended criteria for evaluating research on a diagnostic study, such as the reliability and validity of a new blood test. This hasn't yet been an issue for our JC because the group hasn't selected any diagnostic studies for review. We would have to choose a different CAT should this ever occur. Finally, when our JC formed, we weren't utilizing the most current version of the Johns Hopkins CATs. 31 These older versions rely on the user to determine if the study is a research study versus a quality improvement project, for example. At the onset of our JC, members had difficulty in naming the study design. However, the CATs from the second edition include an algorithm to assist the user in defining the research design and selecting the appropriate CAT. 28 This feature would be very helpful to novice JC members.

Aside from these few limitations, the Johns Hopkins CATs have proven to be excellent tools for critical appraisal in our JC. Having only two forms to choose from, members were quickly able to select the appropriate CAT for each study and readily grew accustomed to the tool formats. It also eased the logistics of ensuring that each participant had the necessary forms. Though conversation in JC initially focused on summaries of the article and whether participants liked the article or not, content shifted to truly being an analysis of the quality of the research and its applicability to practice as members became more skilled in critical appraisal. Surveys of participants' perceptions of barriers to research utilization were conducted at baseline, at 6 months, and at 2 years after initiation of the JC. 33 Participant perception of their own research values, skills, and awareness as barriers to research utilization decreased by 18% at 6 months, and 22% after the JC had been established for 2 years. During an unrelated meeting regarding a practice change, one clinical nurse remarked that she had recently read a randomized controlled trial on the topic, and that she actually understood what that meant thanks to JC. Participation in a JC, utilizing a formalized CAT, can help nurses feel more capable of assessing the quality of research, an important step in promoting the use of research in practice.

- Cited Here |

- PubMed | CrossRef

- View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Determining the level of evidence: experimental research appraisal, caring for hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, a guide to critical appraisal of evidence, the roper-logan-tierney model of nursing.

Justice Studies Research: Critical Appraisal

- APA 7th edition

Critical Appraisal

Video: get lit: the literature review.

Critical Thinker Mind Map

Doing a Literature Review

There are many different resources to help you conduct a thorough literature review. A good one is available from the University of Toronto Library .

How to read a Journal Article from the University of Michigan .

Thinking Critically

Critically appraising articles is vital to evaluating best practice for your population. There are many resources and checklists that can be used to critically appraise for clinical significance such as these Cochrane appraisal tools.

Common questions to ask when critically appraising an article:

- Is my research question clear and concise?

- Are the articles supporting my argument I am articulating in my research question?

- Was the sample size large enough for you to make some general results?

- Are the results statistically significant?

- Are the results clinically significant?

- Did the authors address potential bias in the study?

- Did the researchers identify confounding variables? If so, explain how they authors use control factors.

In addition to appraising the research methodology and quality of your research, social workers should also consider the clinical application to their individual client and client population. Consider the following while you read through your research:

Before reading

- Do I have everything I need about the client’s history, culture, priorities

- Am I making assumptions or bringing forward any personal bias?

- Is my searching accurate to describe the context and history of my clients’ problems? (e.g., “racism AND health” or “structural racism AND mental health” or “racial discrimination AND mental health”)

- Am I really prepared to assess the research?

- Am I using a broad range of knowledge sources and strategies for ways of knowing about a client?

During reading

- Document any questions that I have.

- Is each article/policy really showing the client’s experience and supporting what I my research question?

- Am I noting any structural racism or health inequities in the practices proposed in this policy or article?

- Does the intervention include any internalized scripts of racial, gender or other superiority and inferiority?

- Are there cultural or power contexts that need to be considered?

After reading

- Have I considered using multiple perspectives/disciplines to better understand the problem?

- Do I still need to learn more about my client's language, customs, history or context to better understand the problem?

- If I act on the evidence, am I contributing to dismantling structural racism, power inequities?

- If I move forward with these practices, am I contributing to create conditions where my client can thrive?

Once you have considered all these questions, you are ready to begin writing your paper.

Resource: NASW Evidence-based practice https://www.socialworkers.org/News/Research-Data/Social-Work-Policy-Research/Evidence-Based-Practice

- << Previous: APA 7th edition

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2024 10:41 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.nau.edu/justicestudies

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Introduction

- Related Guides

- Getting Help

Critical Appraisal of Studies

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value/relevance in a particular context by providing a framework to evaluate the research. During the critical appraisal process, researchers can:

- Decide whether studies have been undertaken in a way that makes their findings reliable as well as valid and unbiased

- Make sense of the results

- Know what these results mean in the context of the decision they are making

- Determine if the results are relevant to their patients/schoolwork/research

Burls, A. (2009). What is critical appraisal? In What Is This Series: Evidence-based medicine. Available online at What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal is included in the process of writing high quality reviews, like systematic and integrative reviews and for evaluating evidence from RCTs and other study designs. For more information on systematic reviews, check out our Systematic Review guide.

- Next: Critical Appraisal Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/critappraise

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 27, Issue Suppl 2

- 12 Critical appraisal tools for qualitative research – towards ‘fit for purpose’

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Veronika Williams 1 ,

- Anne-Marie Boylan 2 ,

- Newhouse Nikki 2 ,

- David Nunan 2

- 1 Nipissing University, North Bay, Canada

- 2 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Qualitative research has an important place within evidence-based health care (EBHC), contributing to policy on patient safety and quality of care, supporting understanding of the impact of chronic illness, and explaining contextual factors surrounding the implementation of interventions. However, the question of whether, when and how to critically appraise qualitative research persists. Whilst there is consensus that we cannot - and should not – simplistically adopt existing approaches for appraising quantitative methods, it is nonetheless crucial that we develop a better understanding of how to subject qualitative evidence to robust and systematic scrutiny in order to assess its trustworthiness and credibility. Currently, most appraisal methods and tools for qualitative health research use one of two approaches: checklists or frameworks. We have previously outlined the specific issues with these approaches (Williams et al 2019). A fundamental challenge still to be addressed, however, is the lack of differentiation between different methodological approaches when appraising qualitative health research. We do this routinely when appraising quantitative research: we have specific checklists and tools to appraise randomised controlled trials, diagnostic studies, observational studies and so on. Current checklists for qualitative research typically treat the entire paradigm as a single design (illustrated by titles of tools such as ‘CASP Qualitative Checklist’, ‘JBI checklist for qualitative research’) and frameworks tend to require substantial understanding of a given methodological approach without providing guidance on how they should be applied. Given the fundamental differences in the aims and outcomes of different methodologies, such as ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenological approaches, as well as specific aspects of the research process, such as sampling, data collection and analysis, we cannot treat qualitative research as a single approach. Rather, we must strive to recognise core commonalities relating to rigour, but considering key methodological differences. We have argued for a reconsideration of current approaches to the systematic appraisal of qualitative health research (Williams et al 2021), and propose the development of a tool or tools that allow differentiated evaluations of multiple methodological approaches rather than continuing to treat qualitative health research as a single, unified method. Here we propose a workshop for researchers interested in the appraisal of qualitative health research and invite them to develop an initial consensus regarding core aspects of a new appraisal tool that differentiates between the different qualitative research methodologies and thus provides a ‘fit for purpose’ tool, for both, educators and clinicians.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm-2022-EBMLive.36

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Your web browser is outdated and may be insecure

The RCN recommends using an updated browser such as Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome

Critical Appraisal

Use this guide to find information resources about critical appraisal including checklists, books and journal articles.

Key Resources

- This online resource explains the sections commonly used in research articles. Understanding how research articles are organised can make reading and evaluating them easier View page

- Critical appraisal checklists

- Worksheets for appraising systematic reviews, diagnostics, prognostics and RCTs. View page

- A free online resource for both healthcare staff and patients; four modules of 30–45 minutes provide an introduction to evidence based medicine, clinical trials and Cochrane Evidence. View page

- This tool will guide you through a series of questions to help you to review and interpret a published health research paper. View page

- The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a literature review. It maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for exclusions. View page

- A useful resource for methods and evidence in applied social science. View page

- A comprehensive database of reporting guidelines. Covers all the main study types. View page

- A tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. View page

Book subject search

- Critical appraisal

Journal articles

- View article

Shea BJ and others (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions or both, British Medical Journal, 358.

- An outline of AMSTAR 2 and its use for as a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews. View article (open access)

- View articles

Editor of this guide

RCN Library and Museum

Upcoming events relating to this subject guide

Stay up to date with online journals

Learn how RCN members can stay up to date with online journals quickly and easily using our fantastic BrowZine tool.

Easy referencing ... in 45 minutes

Learn how to generate quick references and citations using free, easy to use, online tools.

Introduction to RCN Library Services

Discover the library service for RCN members

Know How to Search CINAHL

Learn about using the CINAHL database for literature searches at this event for RCN members.

Know How to Reference Accurately

Learn how to use the Harvard referencing style and why referencing is important at this event for RCN members.

Learn how to generate quick references and citations using a free, easy to use, online tool.

Library essentials: finding books and articles online

Learn how to find and access online books and articles using the RCN library search tool.

Know How to Evaluate Healthcare Information

This workshop is led by RCN librarians, who will help you develop the important skill of evaluating healthcare information.

Page last updated - 17/09/2024

Your Spaces

- RCNi Profile

- Steward Portal

- RCN Foundation

- RCN Library

- RCN Starting Out

Work & Venue

- RCNi Nursing Jobs

- Work for the RCN

- RCN Working with us

Further Info

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- Modern slavery statement

- Accessibility

- Press office

Connect with us:

© 2024 Royal College of Nursing

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

99 Citations

446 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Clin Res

- v.12(2); Apr-Jun 2021

Critical appraisal of published research papers – A reinforcing tool for research methodology: Questionnaire-based study

Snehalata gajbhiye.

Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Raakhi Tripathi

Urwashi parmar, nishtha khatri, anirudha potey.

1 Department of Clinical Trials, Serum Institute of India, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Background and Objectives:

Critical appraisal of published research papers is routinely conducted as a journal club (JC) activity in pharmacology departments of various medical colleges across Maharashtra, and it forms an important part of their postgraduate curriculum. The objective of this study was to evaluate the perception of pharmacology postgraduate students and teachers toward use of critical appraisal as a reinforcing tool for research methodology. Evaluation of performance of the in-house pharmacology postgraduate students in the critical appraisal activity constituted secondary objective of the study.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in two parts. In Part I, a cross-sectional questionnaire-based evaluation on perception toward critical appraisal activity was carried out among pharmacology postgraduate students and teachers. In Part II of the study, JC score sheets of 2 nd - and 3 rd -year pharmacology students over the past 4 years were evaluated.

One hundred and twenty-seven postgraduate students and 32 teachers participated in Part I of the study. About 118 (92.9%) students and 28 (87.5%) faculties considered the critical appraisal activity to be beneficial for the students. JC score sheet assessments suggested that there was a statistically significant improvement in overall scores obtained by postgraduate students ( n = 25) in their last JC as compared to the first JC.

Conclusion:

Journal article criticism is a crucial tool to develop a research attitude among postgraduate students. Participation in the JC activity led to the improvement in the skill of critical appraisal of published research articles, but this improvement was not educationally relevant.

INTRODUCTION

Critical appraisal of a research paper is defined as “The process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, value and relevance in a particular context.”[ 1 ] Since scientific literature is rapidly expanding with more than 12,000 articles being added to the MEDLINE database per week,[ 2 ] critical appraisal is very important to distinguish scientifically useful and well-written articles from imprecise articles.

Educational authorities like the Medical Council of India (MCI) and Maharashtra University of Health Sciences (MUHS) have stated in pharmacology postgraduate curriculum that students must critically appraise research papers. To impart training toward these skills, MCI and MUHS have emphasized on the introduction of journal club (JC) activity for postgraduate (PG) students, wherein students review a published original research paper and state the merits and demerits of the paper. Abiding by this, pharmacology departments across various medical colleges in Maharashtra organize JC at frequent intervals[ 3 , 4 ] and students discuss varied aspects of the article with teaching faculty of the department.[ 5 ] Moreover, this activity carries a significant weightage of marks in the pharmacology university examination. As postgraduate students attend this activity throughout their 3-year tenure, it was perceived by the authors that this activity of critical appraisal of research papers could emerge as a tool for reinforcing the knowledge of research methodology. Hence, a questionnaire-based study was designed to find out the perceptions from PG students and teachers.

There have been studies that have laid emphasis on the procedure of conducting critical appraisal of research papers and its application into clinical practice.[ 6 , 7 ] However, there are no studies that have evaluated how well students are able to critically appraise a research paper. The Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Seth GS Medical College has developed an evaluation method to score the PG students on this skill and this tool has been implemented for the last 5 years. Since there are no research data available on the performance of PG Pharmacology students in JC, capturing the critical appraisal activity evaluation scores of in-house PG students was chosen as another objective of the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the journal club activity.

JC is conducted in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at Seth GS Medical College once in every 2 weeks. During the JC activity, postgraduate students critically appraise published original research articles on their completeness and aptness in terms of the following: study title, rationale, objectives, study design, methodology-study population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, duration, intervention and safety/efficacy variables, randomization, blinding, statistical analysis, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and abstract. All postgraduate students attend this activity, while one of them critically appraises the article (who has received the research paper given by one of the faculty members 5 days before the day of JC). Other faculties also attend these sessions and facilitate the discussions. As the student comments on various sections of the paper, the same predecided faculty who gave the article (single assessor) evaluates the student on a total score of 100 which is split per section as follows: Introduction –20 marks, Methodology –20 marks, Discussion – 20 marks, Results and Conclusion –20 marks, References –10 marks, and Title, Abstract, and Keywords – 10 marks. However, there are no standard operating procedures to assess the performance of students at JC.

Methodology