Join our Newsletter

Get helpful tips and the latest information

Problem-Solving Therapy: How It Works & What to Expect

Author: Lydia Antonatos, LMHC

Lydia Angelica Antonatos LMHC

Lydia has over 16 years of experience and specializes in mood disorders, anxiety, and more. She offers personalized, solution-focused therapy to empower clients on their journey to well-being.

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an intervention with cognitive and behavioral influences used to assist individuals in managing life problems. Therapists help clients learn effective skills to address their issues directly and make positive changes. PST is used in various settings to address mental health concerns such as depression, anxiety, and more.

Find the Perfect Therapist for You, with BetterHelp.

If you don’t click with your first match, you can easily switch therapists. BetterHelp has over 30,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $65 per week. Take a free online assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you.

What Is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is based on a model that the body, mind, and environment all interact with each other and that life stress can interact with a person’s predisposition for developing a mental condition. 2 Within this context, PST contends that mental, emotional, and behavioral struggles stem from an ongoing inability to solve problems or deal with everyday stressors. Therefore, the key to preventing health consequences and improving quality of life is to become a better problem-solver. 3 , 4

The problem-solving model has undergone several revisions but upholds the value of teaching people to become better problem-solvers. Overall, the goal of PST is to provide individuals with a set of rational problem-solving tools to reduce the impact of stress on their well-being.

The two main components of problem-solving therapy include: 3 , 4

- Problem-solving orientation: This focuses on helping individuals adopt an optimistic outlook and see problems as opportunities to learn from, allowing them to believe they can solve problems.

- Problem-solving style: This component aims to provide people with constructive problem-solving tools to deal with different life stressors by identifying the problem, generating/brainstorming solution ideas, choosing a specific option, and implementing and reviewing it.

Techniques Used in Problem-Solving Therapy

PST emphasizes the client, and the techniques used are merely conduits that facilitate the problem-solving learning process. Generally, the individual, in collaboration and support from the clinician, leads the problem-solving work. Thus, a strong therapeutic alliance sets the foundation for encouraging clients to apply these skills outside therapy sessions. 4

Here are some of the most relevant guidelines and techniques used in problem-solving therapy:

Creating Collaboration

As with other psychotherapies, creating a collaborative environment and a healthy therapist-client relationship is essential in PST. The role of a therapist is to cultivate this bond by conveying a genuine sense of commitment to the client while displaying kindness, using active listening skills, and providing support. The purpose is to build a meaningful balance between being an active and directive clinician while delivering a feeling of optimism to encourage the client’s participation.

This tool is used in all psychotherapies and is just as essential in PST. Assessment seeks to gather facts and information about current problems and contributing stressors and evaluates a client’s appropriateness for PST. The problem-solving therapy assessment also examines a person’s immediate issues, problem-solving attitudes, and abilities, including their strengths and limitations. This sets the groundwork for developing an individualized problem-solving plan.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation is an integral component of problem-solving therapy and is used throughout treatment. The purpose of psychoeducation is to provide a client with the rationale for problem-solving therapy, including an explanation for each step involved in the treatment plan. Moreover, the individual is educated about mental health symptoms and taught solution-oriented strategies and communication skills.

This technique involves verbal prompting, like asking leading questions, giving suggestions, and providing guidance. For example, the therapist may prompt a client to brainstorm or consider alternatives, or they may ask about times when a certain skill was used to solve a problem during a difficult situation. Coaching can be beneficial when clients struggle with eliciting solutions on their own.

Shaping intervention refers to teaching new skills and building on them as the person gradually improves the quality of each skill. Shaping works by reinforcing the desired problem-solving behavior and adding perspective as the individual gets closer to their intended goal.

In problem-solving therapy, modeling is a method in which a person learns by observing. It can include written/verbal problem-solving illustrations or demonstrations performed by the clinician in hypothetical or real-life situations. A client can learn effective problem-solving skills via role-play exercises, live demonstrations, or short-film presentations. This allows individuals to imitate observed problem-solving skills in their own lives and apply them to specific problems.

Rehearsal & Practice

These techniques provide opportunities to practice problem-solving exercises and engage in homework assignments. This may involve role-playing during therapy sessions, practicing with real-life issues, or imaginary rehearsal where individuals visualize themselves carrying out a solution. Furthermore, homework exercises are an important aspect when learning a new skill. Ongoing practice is strongly encouraged throughout treatment so a client can effectively use these techniques when faced with a problem.

Positive Reinforcement & Feedback

The therapist’s task in this intervention is to provide support and encouragement for efforts to apply various problem-solving skills. The goal is for the client to continue using more adaptive behaviors, even if they do not get it right the first time. Then, the therapist provides feedback so the client can explore barriers encountered and generate alternate solutions by weighing the pros and cons to continue working toward a specific goal.

Use of Analogies & Metaphors

When appropriate, analogies and metaphors can be useful in providing the client with a clearer vision or a better understanding of specific concepts. For example, the therapist may use diverse skills or points of reference (e.g., cooking, driving, sports) to explain the problem-solving process and find solutions to convey that time and practice are required before mastering a particular skill.

What Can Problem-Solving Therapy Help With?

Although problem-solving therapy was initially developed to treat depression among primary care patients, PST has expanded to address or rehabilitate other psychological problems, including anxiety , post-traumatic stress disorder , personality disorders , and more.

PST theory asserts that vulnerable populations can benefit from receiving constructive problem-solving tools in a therapeutic relationship to increase resiliency and prevent emotional setbacks or behaviors with destructive results like suicide. It is worth noting that in severe psychiatric cases, PST can be effectively used when integrated with other mental health interventions. 3 , 4

PST can help individuals challenged with specific issues who have difficulty finding solutions or ways to cope. These issues can involve a wide range of incidents, such as the death of a loved one, divorce, stress related to a chronic medical diagnosis, financial stress , marital difficulties, or tension at work.

Through the problem-solving approach, mental and emotional distress can be reduced by helping individuals break down problems into smaller pieces that are easier to manage and cope with. However, this can only occur as long the person being treated is open to learning and able to value the therapeutic process. 3 , 4

Lastly, a large body of evidence has indicated that PST can positively impact mental health, quality of life, and problem-solving skills in older adults. PST is an approach that can be implemented by different types of practitioners and settings (in-home care services, telemedicine, etc.), making mental health treatment accessible to the elderly population who often face age-related barriers and comorbid health issues. 1 , 5, 6

Top Rated Online Therapy Services

BetterHelp – Best Overall

“BetterHelp is an online therapy platform that quickly connects you with a licensed counselor or therapist and earned 4 out of 5 stars.” Take a free assessment

Talkspace - Best For Insurance

Talkspace accepts many insurance plans including Optum, Cigna, and Aetna. Talkspace also accepts Medicare in some states. The average copay is $15, but many people pay $0. Visit Talkspace

Problem-Solving Therapy Examples

Due to the versatility of problem-solving therapy, PST can be used in different forms, settings, and formats. Following are some examples where the problem-solving therapeutic approach can be used effectively. 4

People who suffer from depression often evade or even attempt to ignore their problems because of their state of mind and symptoms. PST incorporates techniques that encourage individuals to adopt a positive outlook on issues and motivate individuals to tap into their coping resources and apply healthy problem-solving skills. Through psychoeducation, individuals can learn to identify and understand their emotions influence problems. Employing rehearsal exercises, someone can practice adaptive responses to problematic situations. Once the depressed person begins to solve problems, symptoms are reduced, and mood is improved.

The Veterans Health Administration presently employs problem-solving therapy as a preventive approach in numerous medical centers across the United States. These programs aim to help veterans adjust to civilian life by teaching them how to apply different problem-solving strategies to difficult situations. The ultimate objective is that such individuals are at a lower risk of experiencing mental health issues and consequently need less medical and/or psychiatric care.

Psychiatric Patients

PST is considered highly effective and strongly recommended for individuals with psychiatric conditions. These individuals often struggle with problems of daily living and stressors they feel unable to overcome. These unsolved problems are both the triggering and sustaining reasons for their mental health-related troubles. Therefore, a problem-solving approach can be vital for the treatment of people with psychological issues.

Adherence to Other Treatments

Problem-solving therapy can also be applied to clients undergoing another mental or physical health treatment. In such cases, PST strategies can be used to motivate individuals to stay committed to their treatment plan by discussing the benefits of doing so. PST interventions can also be utilized to assist patients in overcoming emotional distress and other barriers that can interfere with successful compliance and treatment participation.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Therapy

PST is versatile, treating a wide range of problems and conditions, and can be effectively delivered to various populations in different forms and settings—self-help manuals, individual or group therapy, online materials, home-based or primary care settings, as well as inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Here are some of the benefits you can gain from problem-solving therapy:

- Gain a sense of control over your life

- Move toward action-oriented behaviors instead of avoiding your problems

- Gain self-confidence as you improve the ability to make better decisions

- Develop patience by learning that successful problem-solving is a process that requires time and effort

- Feel a sense of empowerment as you solve your problems independently

- Increase your ability to recognize and manage stressful emotions and situations

- Learn to focus on the problems that have a solution and let go of the ones that don’t

- Identify barriers that may hinder your progress

How to Find a Therapist Who Practices Problem-Solving Therapy

Finding a therapist skilled in problem-solving therapy is not any different from finding any qualified mental health professional. This is because many clinicians often have knowledge in cognitive-behavioral interventions that hold similar concepts as PST.

As a general recommendation, check your health insurance provider lists, use an online therapist directory , or ask trusted friends and family if they can recommend a provider. Contact any of these providers and ask questions to determine who is more compatible with your needs. 3 , 4

Are There Special Certifications to Provide PST?

Therapists do not need special certifications to practice problem-solving therapy, but some organizations can provide special training. Problem-solving therapy can be delivered by various healthcare professionals such as psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians, mental health counselors, social workers, and nurses.

Most of these clinicians have naturally acquired valuable problem-solving abilities throughout their career and continuing education. Thus, all that may be required is fine-tuning their skills and familiarity with the current and relevant PST literature. A reasonable amount of understanding and planning will transmit competence and help clients gain insight into the causes that led them to their current situation. 3 , 4

Questions to Ask a Therapist When Considering Problem-Solving Therapy

Psychotherapy is most successful when you feel comfortable and have a collaborative relationship with your therapist. Asking specific questions can simplify choosing a clinician who is right for you. Consider making a list of questions to help you with this task.

Here are some key questions to ask before starting PST:

- Is problem-solving therapy suitable for the struggles I am dealing with?

- Can you tell me about your professional experience with providing problem-solving therapy?

- Have you dealt with other clients who present with similar issues as mine?

- Have you worked with individuals of similar cultural backgrounds as me?

- How do you structure your PST sessions and treatment timeline?

- How long do PST sessions last?

- How many sessions will I need?

- What expectations should I have in working with you from a problem-solving therapeutic stance?

- What expectations are required from me throughout treatment?

- Does my insurance cover PST? If not, what are your fees?

- What is your cancellation policy?

How Much Does Problem-Solving Therapy Cost?

The cost of problem-solving therapy can range from $25 to $150 depending on the number of sessions required, severity of symptoms, type of practice, geographic location, and provider’s experience level. However, if your insurance provider covers behavioral health, the out-of-pocket costs per session may be much lower. Medicare supports PST through professionally trained general health practitioners. 1

What to Expect at Your First PST Session

During the first session, the therapist will strive to build a connection and become familiar with you. You will be assessed through a clinical interview and/or questionnaires. During this process, the therapist will gather your background information, inquire about how you approach life problems, how you typically resolve them, and if problem-solving therapy is a suitable treatment for you. 3 , 4

Additionally, you will be provided psychoeducation relating to your symptoms, the problem-solving method and its effectiveness, and your treatment goals. The clinician will likely guide you through generating a list of the current problems you are experiencing, selecting one to focus on, and identifying concrete steps necessary for effective problem-solving. Lastly, you will be informed about the content, duration, costs, and number of therapy sessions the therapist suggests. 3 , 4

Would You Like to Try Therapy?

Find a supportive and compassionate therapist ! BetterHelp has over 30,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $65 per week. Take a free online assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you.

Is Problem-Solving Therapy Effective?

Extensive research and studies have shown the efficacy of problem-solving therapy. PST can yield significant improvements within a short amount of time. PST is also useful for addressing numerous problems and psychological issues. Lastly, PST has shown its efficacy with different populations and age groups.

One meta-analysis of PST for depression concluded that problem-solving therapy was as efficient for reducing symptoms of depression as other types of psychotherapies and antidepressant medication. Furthermore, PST was significantly more effective than not receiving any treatment. 7 However, more investigation may be necessary about PST’s long-term efficacy in comparison to other treatments. 5,6

How Is PST Different From CBT & SFT?

Problem-solving, cognitive-behavioral, and solution-focused therapy belong to the cognitive-behavioral framework, sharing a common goal to modify thoughts, aptitudes, and behaviors to improve mental health and quality of life.

Problem-Solving Therapy Vs. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a short-term psychosocial treatment developed under the premise that how we think affects how we feel and behave. CBT addresses problems arising from maladaptive thought patterns and seeks to challenge and modify these to improve behavioral responses and overall well-being. CBT is the most researched approach and preferred treatment in psychotherapy due to its effectiveness in addressing various problems like anxiety, sleep disorders, substance abuse, and more.

Like CBT, PST addresses mental, emotional, and behavioral issues. However, PST may provide a better balance of cognitive and behavioral elements.

Another difference between these two approaches is that PST mostly focuses on faulty thoughts about problem-solving orientation and modifying maladaptive behaviors that specifically interfere with effective problem-solving. Usually, PST is used as an integrated approach and applied as one of several other interventions in CBT psychotherapy sessions.

Problem-Solving Therapy Vs. Solution-Focused Therapy

Solution-focused therapy (SFT) , like PST, is a goal-directed, evidence-based brief therapeutic approach that encourages optimism, options, and self-efficacy. Similarly, it is also grounded on cognitive behavioral principles. However, it differs from problem-solving therapy because SFT is a semi-structured approach that does not follow a step-by-step sequential format. 8

SFT mainly focuses on solution-building rather than problem-solving, specifically looking at a person’s strengths and previous successes. SFT helps people recognize how their lives would differ without problems by exploring their current coping skills. Community mental health, inpatient settings, and educational environments are increasing the use of SFT due to its demonstrated efficacy. 8

Final Thoughts

Problem-solving therapy can be an effective treatment for various mental health concerns. If you are considering treatment, ask your doctor for recommendations or conduct your own research to learn more about this approach and other options available.

Additional Resources

To help our readers take the next step in their mental health journey, Choosing Therapy has partnered with leaders in mental health and wellness. Choosing Therapy is compensated for marketing by the companies included below.

Online Therapy

BetterHelp – Get support and guidance from a licensed therapist. BetterHelp has over 30,000 therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. Take a free online assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you. Free Assessment

Online Psychiatry

Hims / Hers If you’re living with anxiety or depression, finding the right medication match may make all the difference. Connect with a licensed healthcare provider in just 12 – 48 hours. Explore FDA-approved treatment options and get free shipping, if prescribed. No insurance required. Get Started

Medication + Therapy

Brightside Health – Together, medication and therapy can help you feel like yourself, faster. Brightside Health treatment plans start at $95 per month. United Healthcare, Anthem, Cigna, and Aetna accepted. Following a free online evaluation and receiving a prescription, you can get FDA approved medications delivered to your door. Free Assessment

Starting Therapy Newsletter

A free newsletter for those interested in learning about therapy and how to get the most benefits out of therapy. Get helpful tips and the latest information. Sign Up

Choosing Therapy Directory

You can search for therapists by specialty, experience, insurance, or price, and location. Find a therapist today .

For Further Reading

- 12 Strategies to Stop Using Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

- Depression Therapy: 4 Effective Options to Consider

- CBT for Depression: How It Works, Examples, & Effectiveness

Best Online Therapy Services

There are a number of factors to consider when trying to determine which online therapy platform is going to be the best fit for you. It’s important to be mindful of what each platform costs, the services they provide you with, their providers’ training and level of expertise, and several other important criteria.

Best Online Psychiatry Services

Online psychiatry, sometimes called telepsychiatry, platforms offer medication management by phone, video, or secure messaging for a variety of mental health conditions. In some cases, online psychiatry may be more affordable than seeing an in-person provider. Mental health treatment has expanded to include many online psychiatry and therapy services. With so many choices, it can feel overwhelming to find the one that is right for you.

Problem-Solving Therapy Infographics

A free newsletter for those interested in starting therapy. Get helpful tips and the latest information.

Choosing Therapy strives to provide our readers with mental health content that is accurate and actionable. We have high standards for what can be cited within our articles. Acceptable sources include government agencies, universities and colleges, scholarly journals, industry and professional associations, and other high-integrity sources of mental health journalism. Learn more by reviewing our full editorial policy .

Beaudreau, S. A., Gould, C. E., Sakai, E., & Terri Huh, J. W. (2017). Problem-Solving Therapy. In N. A. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of geropsychology : with 148 figures and 100 tables . Singapore: Springer.

Broerman, R. (2018). Diathesis-Stress Model. In T. Shackleford & V. Zeigler-Hill (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (Living Edition, pp. 1–3). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_891-1

Mehmet Eskin. (2013). Problem solving therapy in the clinical practice . Elsevier.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-Solving Therapy A Treatment Manual . Springer Publishing Company.

Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis. European Psychiatry 48 , 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006

Kirkham, J. G., Choi, N., & Seitz, D. P. (2015). Meta-analysis of problem-solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 31 (5), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4358

Bell, A. C., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2009). Problem-solving therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review , 29 (4), 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.003

Proudlock, S. (2017). The Solution Focused Way Incorporating Solution Focused Therapy Tools and Techniques into Your Everyday Work . Routledge.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Gerber, H. R. (2019). (Emotion‐centered) problem‐solving therapy: An update. Australian Psychologist , 54 (5), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12418

We regularly update the articles on ChoosingTherapy.com to ensure we continue to reflect scientific consensus on the topics we cover, to incorporate new research into our articles, and to better answer our audience’s questions. When our content undergoes a significant revision, we summarize the changes that were made and the date on which they occurred. We also record the authors and medical reviewers who contributed to previous versions of the article. Read more about our editorial policies here .

Your Voice Matters

Can't find what you're looking for.

Request an article! Tell ChoosingTherapy.com’s editorial team what questions you have about mental health, emotional wellness, relationships, and parenting. The therapists who write for us love answering your questions!

Leave your feedback for our editors.

Share your feedback on this article with our editors. If there’s something we missed or something we could improve on, we’d love to hear it.

Our writers and editors love compliments, too. :)

FOR IMMEDIATE HELP CALL:

Medical Emergency: 911

Suicide Hotline: 988

© 2024 Choosing Therapy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Solving problems the cognitive-behavioral way, problem solving is another part of behavioral therapy..

Posted February 2, 2022 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

- Take our Your Mental Health Today Test

- Find a therapist who practices CBT

- Problem-solving is one technique used on the behavioral side of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

- The problem-solving technique is an iterative, five-step process that requires one to identify the problem and test different solutions.

- The technique differs from ad-hoc problem-solving in its suspension of judgment and evaluation of each solution.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, cognitive behavioral therapy is more than challenging negative, automatic thoughts. There is a whole behavioral piece of this therapy that focuses on what people do and how to change their actions to support their mental health. In this post, I’ll talk about the problem-solving technique from cognitive behavioral therapy and what makes it unique.

The problem-solving technique

While there are many different variations of this technique, I am going to describe the version I typically use, and which includes the main components of the technique:

The first step is to clearly define the problem. Sometimes, this includes answering a series of questions to make sure the problem is described in detail. Sometimes, the client is able to define the problem pretty clearly on their own. Sometimes, a discussion is needed to clearly outline the problem.

The next step is generating solutions without judgment. The "without judgment" part is crucial: Often when people are solving problems on their own, they will reject each potential solution as soon as they or someone else suggests it. This can lead to feeling helpless and also discarding solutions that would work.

The third step is evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This is the step where judgment comes back.

Fourth, the client picks the most feasible solution that is most likely to work and they try it out.

The fifth step is evaluating whether the chosen solution worked, and if not, going back to step two or three to find another option. For step five, enough time has to pass for the solution to have made a difference.

This process is iterative, meaning the client and therapist always go back to the beginning to make sure the problem is resolved and if not, identify what needs to change.

Advantages of the problem-solving technique

The problem-solving technique might differ from ad hoc problem-solving in several ways. The most obvious is the suspension of judgment when coming up with solutions. We sometimes need to withhold judgment and see the solution (or problem) from a different perspective. Deliberately deciding not to judge solutions until later can help trigger that mindset change.

Another difference is the explicit evaluation of whether the solution worked. When people usually try to solve problems, they don’t go back and check whether the solution worked. It’s only if something goes very wrong that they try again. The problem-solving technique specifically includes evaluating the solution.

Lastly, the problem-solving technique starts with a specific definition of the problem instead of just jumping to solutions. To figure out where you are going, you have to know where you are.

One benefit of the cognitive behavioral therapy approach is the behavioral side. The behavioral part of therapy is a wide umbrella that includes problem-solving techniques among other techniques. Accessing multiple techniques means one is more likely to address the client’s main concern.

Salene M. W. Jones, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist in Washington State.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Problem-Solving Therapy

Streaming options.

- Description

- Contributor bios

- Suggested resources

- Video details

In Problem-Solving Therapy , Drs. Arthur Nezu and Christine Maguth Nezu demonstrate their positive, goal-oriented approach to treatment. Problem-solving therapy is a cognitive–behavioral intervention geared to improve an individual's ability to cope with stressful life experiences. The underlying assumption of this approach is that symptoms of psychopathology can often be understood as the negative consequences of ineffective or maladaptive coping.

Problem-solving therapy aims to help individuals adopt a realistically optimistic view of coping, understand the role of emotions more effectively, and creatively develop an action plan geared to reduce psychological distress and enhance well-being. Interventions include psychoeducation, interactive problem-solving exercises, and motivational homework assignments.

In this session, Christine Maguth Nezu works with a woman in her 50s who is depressed and deeply concerned about her son's drug addiction. Dr. Nezu first assesses her strengths and weaknesses and then helps her to clarify the problem she is facing so she can begin to move toward a solution.

The overarching goal of problem-solving therapy (PST) is to enhance the individual's ability to cope with stressful life experiences and to foster general behavioral competence. The major assumption underlying this approach, which emanates from a cognitive–behavioral tradition, is that much of what is viewed as "psychopathology" can be understood as consequences of ineffective or maladaptive coping behaviors. In other words, failure to adequately resolve stressful problems in living can engender significant emotional and behavioral problems.

Such problems in living include major negative events (e.g., undergoing a divorce, dealing with the death of a spouse, getting fired from a job, experiencing a major medical illness), as well as recurrent daily problems (e.g., continued arguments with a coworker, limited financial resources, diminished social support). How people resolve or cope with such situations can, in part, determine the degree to which they will likely experience long-lasting psychopathology and behavioral problems (e.g., clinical depression, generalized anxiety, pain, anger, relationship difficulties).

For example, successfully dealing with stressful problems will likely lead to a reduction of immediate emotional distress and prevent long-term psychological problems from occurring. Alternatively, maladaptive or unsuccessful problem resolution, either due to the overwhelming nature of events (e.g., severe trauma) or as a function of ineffective coping attempts, will likely increase the probability that long-term negative affective states and behavioral difficulties will emerge.

Social Problem Solving and Psychopathology

According to this therapy approach, social problem solving (SPS) is considered a key set of coping abilities and skills. SPS is defined as the cognitive–behavioral process by which individuals attempt to identify or discover effective solutions for stressful problems in living. In doing so, they direct their problem-solving efforts at altering the stressful nature of a given situation, their reactions to such situations, or both. SPS refers more to the metaprocess of understanding, appraising, and adapting to stressful life events, rather than representing a single coping strategy or activity.

Problem-solving outcomes in the real world have been found to be determined by two general but partially independent processes—problem orientation and problem-solving style.

Problem orientation refers to the set of generalized thoughts and feelings a person has concerning problems in living, as well as his or her ability to successfully resolve them. It can either be positive (e.g., viewing problems as opportunities to benefit in some way, perceiving oneself as able to solve problems effectively), which serves to enhance subsequent problem-solving efforts, or negative (e.g.,viewing problems as a major threat to one's well-being, overreacting emotionally when problems occur), which functions to inhibit attempts to solve problems.

Problem-solving style refers to specific cognitive–behavioral activities aimed at coping with stressful problems. Such styles are either adaptive, leading to successful problem resolution, or dysfunctional, leading to ineffective coping, which then can generate myriad negative consequences, including emotional distress and behavioral problems. Rational problem solving is the constructive style geared to identify an effective solution to the problem and involves the systematic and planful application of specific problem-solving tasks. Dysfunctional problem-solving styles include (a) impulsivity/carelessness (i.e., impulsive, hurried, and incomplete attempts to solve a problem), and (b) avoidance (i.e.,avoiding problems, procrastinating, and depending on others to solve one's problems).

Important differences have been identified between individuals characterized as "effective" versus "ineffective" problem solvers. In general, when compared to effective problem solvers, persons characterized by ineffective problem solving report a greater number of life problems, more health and physical symptoms, more anxiety, more depression, and more psychological maladjustment. In addition, a negative problem orientation has been found to be associated with negative moods under both routine and stressful conditions, as well as pessimism, negative emotional experiences, and clinical depression. Further, persons with negative orientations tend to worry and complain more about their health.

Problem-Solving Therapy Goals

PST teaches individuals to apply adaptive coping skills to both prevent and cope with stressful life difficulties. Specific PST therapy objectives include

- enhancing a person's positive orientation

- fostering his or her application of specific rational problem-solving tasks (i.e., accurately identifying why a situation is a problem, generating solution alternatives, conducting a cost-benefit analysis in order to decide which ideas to choose to include as part of an overall solution plan, implementing the solution, monitoring its effects, and evaluating the outcome)

- reducing his or her negative orientation

- minimizing one's tendency to engage in dysfunctional problem-solving style activities (i.e., impulsively attempting to solve the problem or avoiding the problem)

PST interventions involve psychoeducation, interactive problem-solving training exercises, practice opportunities, and homework assignments intended to motivate patients to apply the problem-solving principles outside of the therapy sessions.

PST has been shown to be effective regarding a wide range of clinical populations, psychological problems, and the distress associated with chronic medical disorders. Scientific evaluations have focused on unipolar depression, geriatric depression, distressed primary-care patients, social phobia, agoraphobia, obesity, coronary heart disease, adult cancer patients, adults with schizophrenia, mentally retarded adults with concomitant psychiatric problems, HIV-risk behaviors, drug abuse, suicide, childhood aggression, and conduct disorder.

Moreover, PST is flexible with regard to treatment goals and methods of implementation. For example, it can be conducted in a group format, on an individual and couples basis, as part of a larger cognitive–behavioral treatment package, over the phone, as well as on the Internet. It can also be applied as a means of helping patients to overcome barriers associated with successful adherence to other medical or psychosocial treatment protocols (e.g., adhering to weight-loss programs, diabetes regulation).

Arthur M. Nezu, PhD, ABPP, is currently professor of psychology, medicine, and community health and prevention at Drexel University in Philadelphia. He is one of the codevelopers of a cognitive–behavioral approach to teaching social problem-solving skills and has conducted multiple RCTs testing its efficacy across a variety of populations. These populations include clinically depressed adults, depressed geriatric patients, adults with mental retardation and concomitant psychopathology, distressed cancer patients and their spousal caregivers, individuals in weight-loss programs, breast cancer patients, and adult sexual offenders.

Dr. Nezu has contributed to more than 175 professional and scientific publications, including the books Solving Life's Problems: A 5-Step Guide to Enhanced Well-Being , Helping Cancer Patients Cope: A Problem-Solving Approach , and Problem-Solving Therapy: A Positive Approach to Clinical Intervention . He also codeveloped the self-report measure Social Problem-Solving Inventory—Revised . Dr. Nezu is on numerous editorial boards of scientific and professional journals and a member of the Interventions Research Review Committee of the National Institute of Mental Health.

An award-winning psychologist, he was previously president of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, the Behavioral Psychology Specialty Council, the World Congress of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, and the American Board of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology. He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association, the Association for Psychological Science, the Society for Behavior Medicine, the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, and the Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology. Dr. Nezu was awarded the diplomate in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology from the American Board of Professional Psychology and currently serves as a trustee of that board.

He has been in private practice for over 25 years, and is currently conducting outcome studies to evaluate the efficacy of problem-solving therapy to treat depression among adults with heart disease.

Christine Maguth Nezu, PhD, ABPP, is currently professor of psychology, associate professor of medicine, and director of the masters programs in psychology at Drexel University in Philadelphia. She previously served as director of the APA-accredited Internship/Residency in Clinical Psychology, as well as the Cognitive–Behavioral Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, at the Medical College of Pennsylvania/Hahnemann University.

She is the coauthor or editor of more than 100 scholarly publications, including 15 books. Her publications cover a wide range of topics in mental health and behavioral medicine, many of which have been translated into a variety of foreign languages.

Dr. Maguth Nezu is currently the president-elect of the American Board of Professional Psychology, on the board of directors for the American Board of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology, and on the board of directors for the American Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology. She is the recipient of numerous grant awards supporting her research and program development, particularly in the area of clinical interventions. She serves as an accreditation site visitor for APA for clinical training programs and is on the editorial boards of several leading psychology and health journals.

Dr. Maguth Nezu has conducted workshops on clinical interventions and case formulation both nationally and internationally. She is currently the North American representative to the World Congress of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies. She holds a diplomate in Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology from the American Board of Professional Psychology and has been active in private practice for more than 20 years.

Her current areas of interest include the treatment of depression in medical patients, the integration of cognitive and behavioral therapies with patients' spiritual beliefs and practices, interventions directed toward stress, coping, and health, and cognitive behavior therapy and problem-solving therapy for individuals with personality disorders.

- D'Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (2007). Problem-solving therapy: A positive approach to clinical intervention (3rd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Co.

- D'Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A. M., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2002). Social Problem-Solving Inventory—Revised (SPSI-R): Technical manual . North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems.

- Nezu, A. M. (2004). Problem solving and behavior therapy revisited. Behavior Therapy, 35 , 1–33.

- Nezu, A. M., & Nezu, C. M. (in press). Problem-solving therapy. In S. Richards & M. G. Perri (Eds.), Relapse prevention for depression . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Clark, M. (in press). Problem solving as a risk factor for depression. In K. S. Dobson & D. Dozois (Eds.), Risk factors for depression . New York: Elsevier Science.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Perri, M. G. (2006). Problem solving to promote treatment adherence. In W. T. O'Donohue & E. Livens (Eds.), Promoting treatment adherence: A practical handbook for health care providers (pp. 135–148). New York: Sage Publications.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D'Zurilla, T. J. (2007). Solving life's problems: A 5-step guide to enhanced well-being . New York: Springer Publishing Co.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., Friedman, S. H., Faddis, S., & Houts, P. S. (1998). Helping cancer patients cope: A problem-solving approach . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Nezu, C. M., D'Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (2005). Problem-solving therapy: Theory, practice, and application to sex offenders. In M. McMurran & J. McGuire (Eds.), Social problem solving and offenders: Evidence, evaluation and evolution (pp. 103–123). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Nezu, C. M., Palmatier, A., & Nezu, A. M. (2004). Social problem-solving training for caregivers. In E. C. Chang, T. J. D'Zurilla, & L. J. Sanna (Eds.), Social problem solving: Theory, research, and training (pp. 223–238). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Cognitive–Behavioral Relapse Prevention for Addictions G. Alan Marlatt

- Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy With Donald Meichenbaum Donald Meichenbaum

- Depression With Older Adults Peter A. Lichtenberg

- Depression Michael D. Yapko

- Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression Leslie S. Greenberg

- Relapse Prevention Over Time G. Alan Marlatt

- Behavioral Interventions in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Practical Guidance for Putting Theory Into Action, Second Edition Richard F. Farmer and Alexander L. Chapman

- Experiences of Depression: Theoretical, Clinical, and Research Perspectives Sidney J. Blatt

- Preventing Youth Substance Abuse: Science-Based Programs for Children and Adolescents Edited by Patrick Tolan, José Szapocznik, and Soledad Sambrano

You may also like

Existential–Humanistic Case Formulation

Strengths and Flourishing in Psychotherapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression

The Basics of Group Therapy

Constructive Therapy in Practice

Legal Notice

Not a mental health professional.

View APA videos for the public

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Problem-solving interventions and depression among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of the effectiveness of problem-solving interventions in preventing or treating depression

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Centre for Evidence and Implementation, London, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology

Roles Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Centre for Evidence and Implementation, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Social Work, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- Kristina Metz,

- Jane Lewis,

- Jade Mitchell,

- Sangita Chakraborty,

- Bryce D. McLeod,

- Ludvig Bjørndal,

- Robyn Mildon,

- Aron Shlonsky

- Published: August 29, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285949

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Problem-solving (PS) has been identified as a therapeutic technique found in multiple evidence-based treatments for depression. To further understand for whom and how this intervention works, we undertook a systematic review of the evidence for PS’s effectiveness in preventing and treating depression among adolescents and young adults. We searched electronic databases ( PsycINFO , Medline , and Cochrane Library ) for studies published between 2000 and 2022. Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (a) the intervention was described by authors as a PS intervention or including PS; (b) the intervention was used to treat or prevent depression; (c) mean or median age between 13–25 years; (d) at least one depression outcome was reported. Risk of bias of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool. A narrative synthesis was undertaken given the high level of heterogeneity in study variables. Twenty-five out of 874 studies met inclusion criteria. The interventions studied were heterogeneous in population, intervention, modality, comparison condition, study design, and outcome. Twelve studies focused purely on PS; 13 used PS as part of a more comprehensive intervention. Eleven studies found positive effects in reducing depressive symptoms and two in reducing suicidality. There was little evidence that the intervention impacted PS skills or that PS skills acted as a mediator or moderator of effects on depression. There is mixed evidence about the effectiveness of PS as a prevention and treatment of depression among AYA. Our findings indicate that pure PS interventions to treat clinical depression have the strongest evidence, while pure PS interventions used to prevent or treat sub-clinical depression and PS as part of a more comprehensive intervention show mixed results. Possible explanations for limited effectiveness are discussed, including missing outcome bias, variability in quality, dosage, and fidelity monitoring; small sample sizes and short follow-up periods.

Citation: Metz K, Lewis J, Mitchell J, Chakraborty S, McLeod BD, Bjørndal L, et al. (2023) Problem-solving interventions and depression among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of the effectiveness of problem-solving interventions in preventing or treating depression. PLoS ONE 18(8): e0285949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285949

Editor: Thiago P. Fernandes, Federal University of Paraiba, BRAZIL

Received: January 2, 2023; Accepted: May 4, 2023; Published: August 29, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Metz et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant methods and data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This work was commissioned by Wellcome Trust and was conducted independently by the evaluators (all named authors). No grant number is available. Wellcome Trust had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors declare no financial or other competing interests, including their relationship and ongoing work with Wellcome Trust. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Depression among adolescents and young adults (AYA) is a serious, widespread problem. A striking increase in depressive symptoms is seen in early adolescence [ 1 ], with rates of depression being estimated to almost double between the age of 13 (8.4%) and 18 (15.4%) [ 2 ]. Research also suggests that the mean age of onset for depressive disorders is decreasing, and the prevalence is increasing for AYA. Psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), have shown small to moderate effects in preventing and treating depression [ 3 – 6 ]. However, room for improvement remains. Up to half of youth with depression do not receive treatment [ 7 ]. When youth receive treatment, studies indicate that about half of youth will not show measurable symptom reduction across 30 weeks of routine clinical care for depression [ 8 ]. One strategy to improve the accessibility and effectiveness of mental health interventions is to move away from an emphasis on Evidence- Based Treatments (EBTs; e.g., CBT) to a focus on discrete treatment techniques that demonstrate positive effects across multiple studies that meet certain methodological standards (i.e., common elements; 9). Identifying common elements allows for the removal of redundant and less effective treatment content, reducing treatment costs, expanding available service provision and enhancing scability. Furthermore, introducing the most effective elements of treatment early may improve client retention and outcomes [ 9 – 13 ].

A potential common element for depression intervention is problem-solving (PS). PS refers to how an individual identifies and applies solutions to everyday problems. D’Zurilla and colleagues [ 14 – 17 ] conceptualize effective PS skills to include a constructive attitude towards problems (i.e., a positive problem-solving orientation) and the ability to approach problems systematically and rationally (i.e., a rational PS style). Whereas maladaptive patterns, such as negative problem orientation and passively or impulsively addressing problems, are ineffective PS skills that may lead to depressive symptoms [ 14 – 17 ]. Problem Solving Therapy (PST), designed by D’Zurilla and colleagues, is a therapeutic approach developed to decrease mental health problems by improving PS skills [ 18 ]. PST focuses on four core skills to promote adaptive problem solving, including: (1) defining the problem; (2) brainstorming possible solutions; (3) appraising solutions and selecting the best one; and (4) implementing the chosen solution and assessing the outcome [ 14 – 17 ]. PS is also a component in other manualized approaches, such as CBT and Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), as well as imbedded into other wider generalized mental health programming [ 19 , 20 ]. A meta-analysis of over 30 studies found PST, or PS skills alone, to be as effective as CBT and IPT and more effective than control conditions [ 21 – 23 ]. Thus, justifying its identification as a common element in multiple prevention [ 19 , 24 ] and treatment [ 21 , 25 ] programs for adult depression [ 9 , 26 – 28 ].

PS has been applied to youth and young adults; however, no manuals specific to the AYA population are available. Empirical studies suggest maladaptive PS skills are associated with depressive symptoms in AYA [ 5 , 17 – 23 ]. Furthermore, PS intervention can be brief [ 29 ], delivered by trained or lay counsellors [ 30 , 31 ], and provided in various contexts (e.g., primary care, schools [ 23 ]). Given PS’s versatility and effectiveness, PS could be an ideal common element in treating AYA depression; however, to our knowledge, no reviews or meta-analyses on PS’s effectiveness with AYA specific populations exist. This review aimed to examine the effectiveness of PS as a common element in the prevention and treatment of depression for AYA within real-world settings, as well as to ascertain the variables that may influence and impact PS intervention effects.

Identification and selection of studies

Searches were conducted using PsycInfo , Medline , and Cochrane Library with the following search terms: "problem-solving", “adolescent”, “youth”, and” depression, ” along with filters limiting results to controlled studies looking at effectiveness or exploring mechanisms of effectiveness. Synonyms and derivatives were employed to expand the search. We searched grey literature using Greylit . org and Opengrey . eu , contacted experts in the field and authors of protocols, and searched the reference lists of all included studies. The search was undertaken on 4 th June 2020 and updated on 11 th June 2022.

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (a) the intervention was described by authors as a PS intervention or including PS; (b) the intervention was used to treat or prevent depression; (c) mean or median age between 13–25 years; and (d) at least one depression outcome was reported. Literature in electronic format published post 2000 was deemed eligible, given the greater relevance of more recent usage of PS in real-world settings. There was no exclusion for gender, ethnicity, or country setting; only English language texts were included. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental designs (QEDs), systematic reviews/meta-analyses, pilots, or other studies with clearly defined comparison conditions (no treatment, treatment as usual (TAU), or a comparator treatment) were included. We excluded studies of CBT, IPT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), and modified forms of these treatments. These treatments include PS and have been shown to demonstrate small to medium effects on depression [ 13 , 14 , 32 ], but the unique contribution of PS cannot be disentangled. The protocol for this review was not registered; however, all data collection forms, extraction, coding and analyses used in the review are available upon inquiry from the first author.

Study selection

All citations were entered into Endnote and uploaded to Covidence for screening and review against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Reviewers with high inter-rater reliability (98%) independently screened the titles and abstracts. Two reviewers then independently screened full text of articles that met criteria. Duplicates, irrelevant studies, and studies that did not meet the criteria were removed, and the reason for exclusion was recorded (see S1 File for a list of excluded studies). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with the team leads.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data that included: (i) study characteristics (author, publication year, location, design, study aim), (ii) population (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, family income, depression status), (iii) setting, (iv) intervention description (therapeutic or preventative, whether PS was provided alone or as part of a more comprehensive intervention, duration, delivery mode), (v) treatment outcomes (measures used and reported outcomes for depression, suicidality, and PS), and (vi) fidelity/implementation outcomes. For treatment outcomes, we included the original statistical analyses and/or values needed to calculate an effect size, as reported by the authors. If a variable was not included in the study publication, we extracted the information available and made note of missing data and subsequent limitations to the analyses.

RCTs were assessed for quality (i.e., confidence in the study’s findings) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool [ 33 ] which includes assessment of the potential risk of bias relating to the process of randomisation; deviations from the intended intervention(s); missing data; outcome measurement and reported results. Risk of bias pertaining to each domain is estimated using an algorithm, grouped as: Low risk; Some concerns; or High risk. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of included studies, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

We planned to conduct one or more meta-analyses if the studies were sufficiently similar. Data were entered into a summary of findings table as a first step in determining the theoretical and practical similarity of the population, intervention, comparison condition, outcome, and study design. If there were sufficiently similar studies, a meta-analysis would be conducted according to guidelines contained in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook of Systematic Reviews, including tests of heterogeneity and use of random effects models where necessary.

The two searches yielded a total number of 874 records (after the removal of duplicates). After title and abstract screening, 184 full-text papers were considered for inclusion, of which 25 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review ( Fig 1 ). Unfortunately, substantial differences (both theoretical and practical) precluded any relevant meta-analyses, and we were limited to a narrative synthesis.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285949.g001

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessments were conducted on the 23 RCTs ( Fig 2 ; assessments by study presented in S1 Table ). Risk of bias concerns were moderate, and a fair degree of confidence in the validity of study findings is warranted. Most studies (81%) were assessed as ‘some concerns’ (N = 18), four studies were ‘low risk’, and one ‘high risk’. The most frequent areas of concern were the selection of the reported result (n = 18, mostly due to inadequate reporting of a priori analytic plans); deviations from the intended intervention (N = 17, mostly related to insufficient information about intention-to-treat analyses); and randomisation process (N = 13).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285949.g002

Study designs and characteristics

Study design..

Across the 25 studies, 23 were RCTs; two were QEDs. Nine had TAU or wait-list control (WLC) comparator groups, and 16 used active control groups (e.g., alternative treatment). Eleven studies described fidelity measures. The sample size ranged from 26 to 686 and was under 63 in nine studies.

Selected intervention.

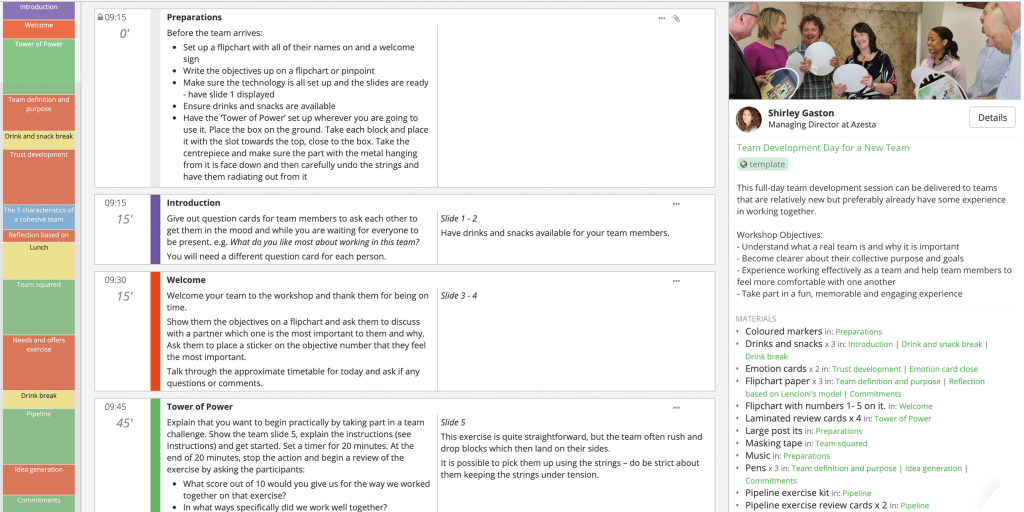

Twenty interventions were described across the 25 studies ( Table 1 ). Ten interventions focused purely on PS. Of these 10 interventions: three were adaptations of models proposed by D’Zurilla and Nezu [ 20 , 34 ] and D’Zurilla and Goldfried [ 18 ], two were based on Mynors-Wallis’s [ 35 ] Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) guide, one was a problem-orientation video intervention adapted from D’Zurilla and Nezu [ 34 ], one was an online intervention adapted from Method of Levels therapy, and three did not specify a model. Ten interventions used PS as part of a larger, more comprehensive intervention (e.g., PS as a portion of cognitive therapy). The utilization and dose of PS steps included in these interventions were unclear. Ten interventions were primary prevention interventions–one of these was universal prevention, five were indicated prevention, and four were selective prevention. Ten interventions were secondary prevention interventions. Nine interventions were described as having been developed or adapted for young people.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285949.t001

Intervention delivery.

Of the 20 interventions, eight were delivered individually, eight were group-based, two were family-based, one was mixed, and in one, the format of delivery was unclear. Seventeen were delivered face-to-face and three online. Dosage ranged from a single session to 21, 50-minute sessions (12 weekly sessions, then 6 biweekly sessions); the most common session formar was once weekly for six weeks (N = 5).

Intervention setting and participants.

Seventeen studies were conducted in high-income countries (UK, US, Australia, Netherlands, South Korea), four in upper-middle income (Brazil, South Africa, Turkey), and four in low- and middle-income countries (Zimbabwe, Nigeria, India). Four studies included participants younger than 13 and four older than 25. Nine studies were conducted on university or high school student populations and five on pregnant or post-partum mothers. The remaining 11 used populations from mental health clinics, the community, a diabetes clinic, juvenile detention, and a runaway shelter.

Sixteen studies included participants who met the criteria for a depressive, bipolar, or suicidal disorder (two of these excluded severe depression). Nine studies did not use depression symptoms in the inclusion criteria (one of these excluded depression). Several studies excluded other significant mental health conditions.

Outcome measures.

Eight interventions targeted depression, four post/perinatal depression, two suicidal ideation, two resilience, one ‘problem-related distress’, one ‘diabetes distress’, one common adolescent mental health problem, and one mood episode. Those targeting post/perinatal depression used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as the outcome measure. Of the others, six used the Beck Depression Inventory (I or II), two the Children’s Depression Inventory, three the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21, three the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, one the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, one the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, one the depression subscale on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, one the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, one the Youth Top Problems Score, one the Adolescent Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation and Psychiatric Status Ratings, one the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, and one the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

Only eight studies measured PS skills or orientation outcomes. Three used the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised, one the Problem Solving Inventory, two measured the extent to which the nominated problem had been resolved, one observed PS in video-taped interactions, and one did not specify the measure.

The mixed findings regarding the effectiveness of PS for depression may depend on the type of intervention: primary (universal, selective, or indicated), secondary or tertiary prevention. Universal prevention interventions target the general public or a population not determined by any specific criteria [ 36 ]. Selective prevention interventions target specific populations with an increased risk of developing a disorder. Indicated prevention interventions target high-risk individuals with sub-clinical symptoms of a disorder. Secondary prevention interventions include those that target individuals diagnosed with a disorder. Finally, tertiary prevention interventions refer to follow-up interventions designed to retain treatment effects. Outcomes are therefore grouped by intervention prevention type and outcome. Within these groupings, studies with a lower risk of bias (RCTs) are presented first. According to the World Health Organisation guidelines, interventions were defined as primary, secondary or tertiary prevention [ 36 ].

Universal prevention interventions

One study reported on a universal prevention intervention targeting resilience and coping strategies in US university students. The Resilience and Coping Intervention, which includes PS as a primary component of the intervention, found a significant reduction in depression compared to TAU (RCT, N = 129, moderate risk of bias) [ 37 ].

Selective prevention interventions

Six studies, including five RCTs and one QED, tested PS as a selective prevention intervention. Two studies investigated the impact of the Manage Your Life Online program, which includes PS as a primary component of the intervention, compared with an online programme emulating Rogerian psychotherapy for UK university students (RCT, N = 213, moderate risk of bias [ 38 ]; RCT, N = 48, moderate risk of bias [ 39 ]). Both studies found no differences in depression or problem-related distress between groups.

Similarly, two studies explored the effect of adapting the Penn Resilience Program, which includes PS as a component of a more comprehensive intervention for young people with diabetes in the US (RCT, N = 264, moderate risk of bias) [ 40 , 41 ]. The initial study showed a moderate reduction in diabetes distress but not depression at 4-, 8-, 12- and 16-months follow-up compared to a diabetes education intervention [ 40 ]. The follow-up study found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared to the active control from 16- to 40-months; however, this did not reach significance at 40-months [ 41 ].

Another study that was part of wider PS and social skills intervention among juveniles in state-run detention centres in the US found no impacts (RCT, N = 296, high risk of bias) [ 42 ]. A QED ( N = 32) was used to test the effectiveness of a resilience enhancement and prevention intervention for runaway youth in South Korea [ 43 ]. There was a significant decrease in depression for the intervention group compared with the control group at post-test, but the difference was not sustained at one-month follow-up.

Indicated prevention interventions

Six studies, including five RCTs and one QED, tested PS as an indicated prevention intervention. Four of the five RCTs tested PS as a primary component of the intervention. A PS intervention for common adolescent mental health problems in Indian high school students (RCT, N = 251, low risk of bias) led to a significant reduction in psychosocial problems at 6- and 12 weeks; however, it did not have a significant impact on mental health symptoms or internalising symptoms compared to PS booklets without counsellor treatment at 6- and 12-weeks [ 31 ]. A follow-up study showed a significant reduction in overall psychosocial problems and mental health symptoms, including internalizing symptoms, over 12 months [ 44 ]. Still, these effects no longer reached significance in sensitivity analysis adjusting for missing data (RCT, N = 251, low risk of bias). Furthermore, a 2x2 factorial RCT ( N = 176, moderate risk of bias) testing PST among youth mental health service users with a mild mental disorder in Australia found that the intervention was not superior to supportive counselling at 2-weeks post-treatment [ 30 ]. Similarly, an online PS intervention delivered to young people in the Netherlands to prevent depression (RCT, N = 45, moderate risk of bias) found no significant difference between the intervention and WLC in depression level 4-months post-treatment [ 45 ].

One RCT tested PS approaches in a more comprehensive manualized programme for postnatal depression in the UK and found no significant differences in depression scores between intervention and TAU at 3-months post-partum (RCT, N = 292, moderate risk of bias) [ 46 ].

A study in Turkey used a non-equivalent control group design (QED, N = 62) to test a nursing intervention against a PS control intervention [ 47 ]. Both groups showed a reduction in depression, but the nursing care intervention demonstrated a larger decrease post-intervention than the PS control intervention.

Secondary prevention interventions

Twelve studies, all RCTs, tested PS as a secondary prevention intervention. Four of the 12 RCTs tested PS as a primary component of the intervention. An intervention among women in Zimbabwe (RCT, N = 58, moderate risk of bias) found a larger decrease in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score for the intervention group compared to control (who received the antidepressant amitriptyline and peer education) at 6-weeks post-treatment [ 48 ]. A problem-orientation intervention covering four PST steps and involving a single session video for US university students (RCT, N = 110, moderate risk of bias), compared with a video covering other health issues, resulted in a moderate reduction in depression post-treatment; however, results were no longer significant at 2-weeks, and 1-month follow up [ 49 ].

Compared to WLC, a study of an intervention for depression and suicidal proneness among high school and university students in Turkey (RCT, N = 46, moderate risk of bias) found large effect sizes on post-treatment depression scores for intervention participants post-treatment compared with WLC. At 12-month follow-up, these improvements were maintained compared to pre-test but not compared to post-treatment scores. Significant post-treatment depression recovery was also found in the PST group [ 12 ]. Compared to TAU, a small but high-quality (low-risk of bias) study focused on preventing suicidal risk among school students in Brazil (RCT, N = 100, low risk of bias) found a significant, moderate reduction in depression symptoms for the treatment group post-intervention that was maintained at 1-, 3- and 6-month follow-up [ 50 ].

Seven of the 12 RCTs tested PS as a part of a more comprehensive intervention. Two interventions targeted mood episodes and were compared to active control. These US studies focused on Family-Focused Therapy as an intervention for mood episodes, which included sessions on PS [ 51 , 52 ]. One of these found that Family-Focused Therapy for AYA with Bipolar Disorder (RCT, N = 145, moderate risk of bias) had no significant impact on mood or depressive symptoms compared to pharmacotherapy. However, Family-Focused Therapy had a greater impact on the proportion of weeks without mania/hypomania and mania/hypomania symptoms than enhanced care [ 53 ]. Alternatively, while the other study (RCT, N = 127, low risk of bias) found no significant impact on time to recovery, Family-Focused Therapy led to significantly longer intervals of wellness before new mood episodes, longer intervals between recovery and the next mood episode, and longer intervals of randomisation to the next mood episode in AYA with either Bipolar Disorder (BD) or Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), compared to family and individual psychoeducation [ 52 ].

Two US studies used a three-arm trial to compare Systemic-behavioural Family Therapy (SBFT) with elements of PS, to CBT and individual Non-directive Supportive therapy (NST) (RCT, N = 107, moderate risk of bias) [ 53 , 54 ]. One study looked at whether the PS elements of CBT and SFBT mediated the effectiveness of these interventions for the remission of MDD. It found that PS mediated the association between CBT, but not SFBT, and remission from depression. There was no significant association between SBFT and remission status, though there was a significant association between CBT and remission status [ 53 ]. The other study found no significant reduction in depression post-treatment or at 24-month follow-up for SBFT [ 54 ].

A PS intervention tested in maternal and child clinics in Nigeria RCT ( N = 686, moderate risk of bias) compared with enhanced TAU involving psychosocial and social support found no significant difference in the proportion of women who recovered from depression at 6-months post-partum [ 55 ]. However, there was a small difference in depression scores in favour of PS averaged across the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up points. Cognitive Reminiscence Therapy, which involved recollection of past PS experiences and drew on PS techniques used for 12-25-year-olds in community mental health services in Australia (RCT, N = 26, moderate risk of bias), did not reduce depression symptoms compared with a brief evidence-based treatment at 1- or 2-month follow-up [ 56 ]. Additionally, the High School Transition Program in the US (RCT, N = 497, moderate risk of bias) aimed to prevent depression, anxiety, and school problems in youth transitioning to high school [ 57 ]. There was no reduction in the percentage of intervention students with clinical depression compared to the control group. Similarly, a small study focused on reducing depression symptoms, and nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women with HIV in South Africa (RCT, N = 23, some concern) found a significant reduction in depression symptoms compared to TAU, with the results being maintained at the 3-month follow-up [ 58 ].

Reduction in suicidality

Three studies measured a reduction in suicidality. A preventive treatment found a large reduction in suicidal orientation in the PS group compared to control post-treatment. In contrast, suicidal ideation scores were inconsistent at 1-,3- and 6- month follow-up, they maintained an overall lower score [ 50 ]. Furthermore, at post-test, significantly more participants in the PS group were no longer at risk of suicide. No significant differences were found in suicide plans or attempts. In a PST intervention, post-treatment suicide risk scores were lower than pre-treatment for the PST group but unchanged for the control group [ 12 ]. An online treatment found a moderate decline in ideation for the intervention group post-treatment compared to the control but was not sustained at a one-month follow-up [ 49 ].

Mediators and moderators

Eight studies measured PS skills or effectiveness. In two studies, despite the interventions reducing depression, there was no improvement in PS abilities [ 12 , 52 ]. One found that change in global and functional PS skills mediated the relationship between the intervention group and change in suicidal orientation, but this was not assessed for depression [ 50 ]. Three other studies found no change in depression symptoms, PS skills, or problem resolution [ 38 – 40 ]. Finally, CBT and SBFT led to significant increases in PS behaviour, and PS was associated with higher rates of remission across treatments but did not moderate the relationship between SBFT and remission status [ 53 ]. Another study found no changes in confidence in the ability to solve problems or belief in personal control when solving problems. Furthermore, the intervention group was more likely to adopt an avoidant PS style [ 46 ].

A high-intensity intervention for perinatal depression in Nigeria had no treatment effect on depression remission rates for the whole sample. Still, it was significantly effective for participants with more severe depression at baseline [ 55 ]. A PS intervention among juvenile detainees in the US effectively reduced depression for participants with higher levels of fluid intelligence, but symptoms increased for those with lower levels [ 42 ].The authors suggest that individuals with lower levels of fluid intelligence may have been less able to cope with exploring negative emotions and apply the skills learned.

This review has examined the evidence on the effectiveness of PS in the prevention or treatment of depression among 13–25-year-olds. We sought to determine in what way, in which contexts, and for whom PS appears to work in addressing depression. We found 25 studies involving 20 interventions. Results are promising for secondary prevention interventions, or interventions targeting clinical level populations, that utilize PS as the primary intervention [ 12 , 47 – 49 ]. These studies not only found a significant reduction in depression symptoms compared to active [ 48 , 49 ] and non-active [ 12 , 47 ] controls but also found a significant reduction in suicidal orientation and ideation [ 12 , 47 , 49 ]. These findings are consistent with meta-analyses of adult PS interventions [ 21 , 22 , 23 ], highlighting that PS interventions for AYA can be effective in real-world settings.