How To Write A Sociology Research Paper Outline: Easy Guide With Template

Table of contents

- 1 What Is A Sociology Research Paper?

- 2 Sociology Paper Format

- 3 Structure of the Sociology Paper

- 4 Possible Sociology Paper Topics

- 5.1 Sociology Research Paper Outline Example

- 6 Sociology Research Paper Example

Writing a sociology research paper is mandatory in many universities and school classes, where students must properly present a relevant topic chosen with supporting evidence, exhaustive research, and new ways of understanding or explaining some author’s ideas. This type of paper is very common among political science majors and classes but can be assigned to almost every subject.

Learn about the key elements of a sociological paper and how to write an excellent piece.

Sociology papers require a certain structure and format to introduce the topic and key points of the research according to academic requirements. For those students struggling with this type of assignment, the following article will share some light on how to write a sociology research paper and create a sociology research paper outline, among other crucial points that must be addressed to design and write an outstanding piece.

With useful data about this common research paper, including topic ideas and a detailed outline, this guide will come in handy for all students and writers in need of writing an academic-worthy sociology paper.

What Is A Sociology Research Paper?

A sociology research paper is a specially written composition that showcases the writer’s knowledge on one or more sociology topics. Writing in sociology requires a certain level of knowledge and skills, such as critical thinking and cohesive writing, to be worthy of great academic recognition.

Furthermore, writing sociology papers have to follow a research paper type of structure to ensure the hypothesis and the rest of the ideas introduced in the research can be properly read and understood by teachers, peers, and readers in general.

Sociology research papers are commonly written following the format used in reports and are based on interviews, data, and text analysis. Writing a sociology paper requires students to perform unique research on a relevant topic (including the appropriate bibliography and different sources used such as books, websites, scientific journals, etc.), test a question or hypothesis that the paper will try to prove or deny, compare different sociologist’s points of view and how/why they state certain sayings and data, among other critical points.

A research paper in sociology also needs to apply the topic of current events, at least in some parts of the piece, in which writers must apply the theory to today’s scenarios. In addition to this, sociology research requires students to perform some kind of field research such as interviews, observational and participant research, and others.

Sociology research papers require a deep understanding of the subject and the ability to gather information from multiple sources. Therefore, many students seek help from experienced online essay writers to guide them through the research process and craft a compelling paper. With the help of a professional essay writer, students can craft a comprehensive sociology research paper outline to ensure they cover all the relevant points.

After explaining what this type of paper consists of, it is time to dive into one of the most searched questions online, “What format are sociology papers written in?”. Below you can find a detailed paragraph with all the information necessary.

Sociology Paper Format

A sociology paper format follows some standard requirements that can be seen on other types of papers as well. The format commonly used in college and other academic institutions consists of an appropriate citation style, which many professors ask for in the traditional APA format, but others can also require students to write in ASA style (very similar to APA, and the main difference is how you write the author’s name).

The citation is one of the major parts of any sociological research paper that needs to be understood perfectly and used according to the rules established by it. Failing to present a cohesive and correct citing format is very likely to cause the failure of the assignment.

As for the visual part of the paper, a neat and professional font is called for, and generally, the standard sociology paper outline is written in Times New Roman font (12pt and double spaced) with at least 1 inch of margin on both sides. If your professor did not specify which sociology format to use, it is safe to say that this one will be just fine for your delivery.

Sociology papers have a specific structure, just like other research pieces, which consist of an introduction , a body with respective paragraphs for each new idea, and a research conclusion . In the point below, you can find a detailed sociology research paper outline to help you write your statement as smoothly and professionally as possible.

Structure of the Sociology Paper

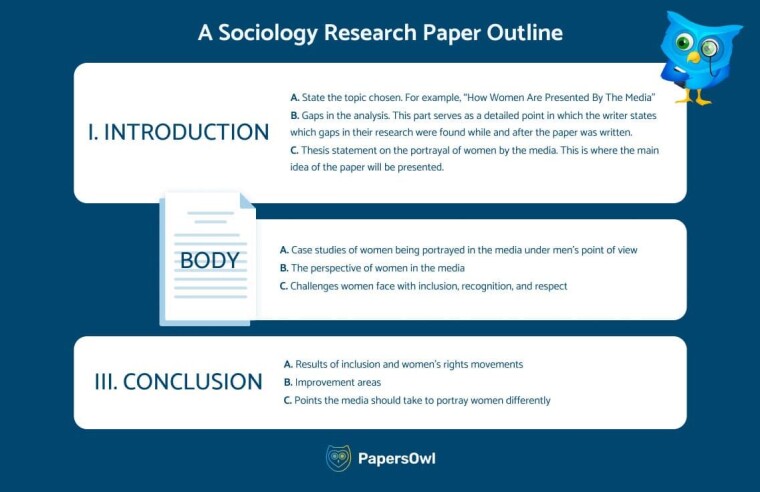

A traditional sociology research paper outline is based on a few key points that help present and develop the information and the writer’s skills properly. Below is a sociology research paper outline to start designing your project according to the standard requirements.

- Introduction. In this first part, you should state the question or problem to be solved during the article. Including a hypothesis and supporting the claim relevant to the chosen field is recommended.

- Literature review. Including the literature review is essential to a sociology research paper outline to present the authors and information used.

- Methodology. A traditional outline for a sociology research paper includes the methodology used, in which writers should explain how they approach their research and the methods used. It gives credibility to their work and makes it more professional.

- Outcomes & findings. Sociological research papers must include, after the methodology, the outcomes and findings to provide readers with a glimpse of what your paper resulted in. Graphics and tables are highly encouraged to use on this part.

- Discussion. The discussion part of a sociological paper serves as an overall review of the research, how difficult it was, and what can be improved.

- Conclusion. Finally, to close your sociology research paper outline, briefly mention the results obtained and do the last paragraph with the writer’s final words on the topic.

- Bibliography. The bibliography should be the last page (or pages) included in the article but in different sheets than the paper (this means, if you finished your article in the middle of the page, the bibliography should start on a new separate one), in which sources must be cited according to the style chosen (APA, ASA, etc.).

This sociology research paper outline serves as a great guide for those who want to properly present a sociological piece worthy of academic recognition. Furthermore, to achieve a good grade, it is essential to choose a great topic.

Below you can find some sociology paper topics to help you decide how to begin writing yours.

Possible Sociology Paper Topics

To present a quality piece, choosing a relevant topic inside the sociological field is essential. Here you can find unique sociology research paper topics that will make a great presentation.

- Relationship Between Race and Class

- How Ethnicity Affects Education

- How Women Are Presented By The Media

- Sexuality And Television

- Youth And Technology: A Revision To Social Media

- Technology vs. Food: Who Comes First?

- How The Cinema Encourages Unreachable Standards

- Adolescence And Sex

- How Men And Women Are Treated Different In The Workplace

- Anti-vaccination: A Civil Right Or Violation?

These sociology paper topics will serve as a starting point where students can conduct their own research and find their desired approach. Furthermore, these topics can be studied in various decades, which adds more value and data to the paper.

Writing a Great Sociology Research Paper Outline

If you’re searching for how to write a sociology research paper, this part will come in handy. A good sociology research paper must properly introduce the topic chosen while presenting supporting evidence, the methodology used, and the sources investigated, and to reach this level of academic excellence, the following information will provide a great starting point.

Three main sociology research paper outlines serve similar roles but differ in a few things. The traditional outline utilizes Roman numerals to itemize sections and formats the sub-headings with capital letters, later using Arabic numerals for the next layer. This one is great for those who already have an idea of what they’ll write about.

The second sample is the post-draft outline, where writers mix their innovative ideas and the actual paper’s outline. This second type of draft is ideal for those with a few semi-assembled ideas that need to be developed around the paper’s main idea. Naturally, a student will end up finding their way through the research and structuring the piece smoothly while writing it.

Lastly, the third type of outline is referred to as conceptual outline and serves as a visual representation of the text written. Similar to a conceptual map, this outline used big rectangles that include the key topics or headings of the paper, as well as circles that represent the sources used to support those headings. This one is perfect for those who need to visually see their paper assembled, and it can also be used to see which ideas need further development or supporting evidence.

Furthermore, to write a great sociology paper, the following tips will be of great help.

- Introduction. An eye-catching introduction calls for an unknown or relevant fact that captivates the reader’s attention. Apart from conducting excellent research, students worthy of the highest academic score are those able to present the information properly and in a way that the audience will be interested in reading.

- Body. The paragraphs presented must be written attractively, to make readers want to know more. It is important to explain theories and add supporting evidence to back up your sayings and ideas; empirical data is highly recommended to be added to give the research paper more depth and physical recognition. A great method is to start a paragraph presenting an idea or theory, develop the paragraph with supporting evidence and close it with findings or results. This way, readers can easily understand the idea and comprehend what you want to portray.

- Conclusion. For the conclusion, it is highly important, to sum up the key points presented in the sociology research paper, and after doing so, professors always recommend adding further readings or suggested bibliography to help readers who are interested in continuing their education on the topic just read.

No matter the method you choose to plan out your sociological papers, you’ll need to cover a few bases of how to assemble your final draft. If you’re stuck on where to begin your work, you can always buy sociology research paper from professional writers. Many students go to the pros to shore up their grades and make time when deadlines become overwhelming. If you do it independently, double-check your assignment’s requirements and fit them into the following sections.

Sociology Research Paper Outline Example

The following sociology research paper outline example will serve as an excellent guide and template which students can customize to fit their topics and key points. The outline above follows the topic “How Women Are Presented By The Media”.

Sociology Research Paper Example

PapersOwl website is an excellent resource if you’re looking for more detailed examples of sociology research papers. We provide a wide range of sample research papers that can serve as a guide and template for your own work.

“Changing Demographics Customer Service to Millennials” Example

Students who structure their sociological papers before conducting in-depth research are more likely to succeed. This happens because it is easier and more efficient to research specific key points rather than diving into the topic without knowing how to approach it or presenting the information, data, statistics, and others found.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

How to Write a Sociological Essay: Explained with Examples

This article will discuss “How to Write a Sociological Essay” with insider pro tips and give you a map that is tried and tested. An essay writing is done in three phases: a) preparing for the essay, b) writing the essay, and c) editing the essay. We will take it step-by-step so that nothing is left behind because the devil, as well as good grades and presentation, lies in the details.

Those who belong to the world of academia know that writing is something that they cannot escape. No writing is the same when it comes to different disciplines of academia. Similarly, the discipline of sociology demands a particular style of formal academic writing. If you’re a new student of sociology, it can be an overwhelming subject, and writing assignments don’t make the course easier. Having some tips handy can surely help you write and articulate your thoughts better.

[Let us take a running example throughout the article so that every point becomes crystal clear. Let us assume that the topic we have with us is to “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” .]

Phase I: Preparing for the Essay

Step 1: make an outline.

[Explanation through example, assumed topic: “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” . Your outline will look something like this:

Step 2: Start Reading

Once you have prepared an outline for your essay, the next step is to start your RESEARCH . You cannot write a sociological essay out of thin air. The essay needs to be thoroughly researched and based on facts. Sociology is the subject of social science that is based on facts and evidence. Therefore, start reading as soon as you have your outline determined. The more you read, the more factual data you will collect. But the question which now emerges is “what to read” . You cannot do a basic Google search to write an academic essay. Your research has to be narrow and concept-based. For writing a sociological essay, make sure that the sources from where you read are academically acclaimed and accepted.

Step 3: Make Notes

This is a step that a lot of people miss when they are preparing to write their essays. It is important to read, but how you read is also a very vital part. When you are reading from multiple sources then all that you read becomes a big jumble of information in your mind. It is not possible to remember who said what at all times. Therefore, what you need to do while reading is to maintain an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY . Whenever you’re reading for writing an academic essay then have a notebook handy, or if you prefer electronic notes then prepare a Word Document, Google Docs, Notes, or any tool of your choice to make notes.

Annotate and divide your notes based on the outline you made. Having organized notes will help you directly apply the concepts where they are needed rather than you going and searching for them again.]

Phase II: Write a Sociological Essay

Now let us get into the details which go into the writing of a sociological essay.

Step 4: Writing a Title, Subtitle, Abstract, and Keywords

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Make the font color of your subtitle Gray instead of Black for it to stand out.

[Explanation through example, assumed topic: “Explore Culinary Discourse among the Indian Diasporic Communities” .

Your abstract should highlight all the points that you will further discuss. Therefore your abstract should mention how diasporic communities are formed and how they are not homogeneous communities. There are differences within this large population. In your essay, you will talk in detail about all the various aspects that affect food and diasporic relationships. ]

Keywords are an extension of your abstract. Whereas in your abstract you will use a paragraph to tell the reader what to expect ahead, by stating keywords, you point out the essence of your essay by using only individual words. These words are mostly concepts of social sciences. At first, glance, looking at your keywords, the reader should get informed about all the concepts and themes you will explain in detail later.

Your keywords could be: Food, Diaspora, Migration, and so on. Build on these as you continue to write your essay.]

Step 5: Writing the Introduction, Main Body, and Conclusion

Your introduction should talk about the subject on which you are writing at the broadest level. In an introduction, you make your readers aware of what you are going to argue later in the essay. An introduction can discuss a little about the history of the topic, how it was understood till now, and a framework of what you are going to talk about ahead. You can think of your introduction as an extended form of the abstract. Since it is the first portion of your essay, it should paint a picture where the readers know exactly what’s ahead of them.

Since your focus is on “food” and “diaspora”, your introductory paragraph can dwell into a little history of the relationship between the two and the importance of food in community building.]

The main body is mostly around 4 to 6 paragraphs long. A sociological essay is filled with debates, theories, theorists, and examples. When writing the main body it is best to target making one or two paragraphs about the same revolving theme. When you shift to the other theme, it is best to connect it with the theme you discussed in the paragraph right above it to form a connection between the two. If you are dividing your essay into various sub-themes then the best way to correlate them is starting each new subtheme by reflecting on the last main arguments presented in the theme before it. To make a sociological essay even more enriching, include examples that exemplify the theoretical concepts better.

The main body can here be divided into the categories which you formed during the first step of making the rough outline. Therefore, your essay could have 3 to 4 sub-sections discussing different themes such as: Food and Media, Caste and Class influence food practices, Politics of Food, Gendered Lens, etc.]

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: As the introduction, the conclusion is smaller compared to the main body. Keep your conclusion within the range of 1 to 2 paragraphs.

Step 6: Citation and Referencing

This is the most academic part of your sociological essay. Any academic essay should be free of plagiarism. But how can one avoid plagiarism when their essay is based on research which was originally done by others. The solution for this is to give credit to the original author for their work. In the world of academia, this is done through the processes of Citation and Referencing (sometimes also called Bibliography). Citation is done within/in-between the text, where you directly or indirectly quote the original text. Whereas, Referencing or Bibliography is done at the end of an essay where you give resources of the books or articles which you have quoted in your essay at various points. Both these processes are done so that the reader can search beyond your essay to get a better grasp of the topic.

How to add citations in Word Document: References → Insert Citations

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: Always make sure that your Bibliography/References are alphabetically ordered based on the first alphabet of the surname of the author and NOT numbered or bulleted.

Phase III: Editing

Step 7: edit/review your essay.

Pro Tip by Sociology Group: The more you edit the better results you get. But we think that your 3rd draft is the magic draft. Draft 1: rough essay, Draft 2: edited essay, Draft 3: final essay.

What this handout is about

This handout introduces you to the wonderful world of writing sociology. Before you can write a clear and coherent sociology paper, you need a firm understanding of the assumptions and expectations of the discipline. You need to know your audience, the way they view the world and how they order and evaluate information. So, without further ado, let’s figure out just what sociology is, and how one goes about writing it.

What is sociology, and what do sociologists write about?

Unlike many of the other subjects here at UNC, such as history or English, sociology is a new subject for many students. Therefore, it may be helpful to give a quick introduction to what sociologists do. Sociologists are interested in all sorts of topics. For example, some sociologists focus on the family, addressing issues such as marriage, divorce, child-rearing, and domestic abuse, the ways these things are defined in different cultures and times, and their effect on both individuals and institutions. Others examine larger social organizations such as businesses and governments, looking at their structure and hierarchies. Still others focus on social movements and political protest, such as the American civil rights movement. Finally, sociologists may look at divisions and inequality within society, examining phenomena such as race, gender, and class, and their effect on people’s choices and opportunities. As you can see, sociologists study just about everything. Thus, it is not the subject matter that makes a paper sociological, but rather the perspective used in writing it.

So, just what is a sociological perspective? At its most basic, sociology is an attempt to understand and explain the way that individuals and groups interact within a society. How exactly does one approach this goal? C. Wright Mills, in his book The Sociological Imagination (1959), writes that “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” Why? Well, as Karl Marx observes at the beginning of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), humans “make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” Thus, a good sociological argument needs to balance both individual agency and structural constraints. That is certainly a tall order, but it is the basis of all effective sociological writing. Keep it in mind as you think about your own writing.

Key assumptions and characteristics of sociological writing

What are the most important things to keep in mind as you write in sociology? Pay special attention to the following issues.

The first thing to remember in writing a sociological argument is to be as clear as possible in stating your thesis. Of course, that is true in all papers, but there are a couple of pitfalls common to sociology that you should be aware of and avoid at all cost. As previously defined, sociology is the study of the interaction between individuals and larger social forces. Different traditions within sociology tend to favor one side of the equation over the other, with some focusing on the agency of individual actors and others on structural factors. The danger is that you may go too far in either of these directions and thus lose the complexity of sociological thinking. Although this mistake can manifest itself in any number of ways, three types of flawed arguments are particularly common:

- The “ individual argument ” generally takes this form: “The individual is free to make choices, and any outcomes can be explained exclusively through the study of their ideas and decisions.” While it is of course true that we all make our own choices, we must also keep in mind that, to paraphrase Marx, we make these choices under circumstances given to us by the structures of society. Therefore, it is important to investigate what conditions made these choices possible in the first place, as well as what allows some individuals to successfully act on their choices while others cannot.

- The “ human nature argument ” seeks to explain social behavior through a quasi-biological argument about humans, and often takes a form such as: “Humans are by nature X, therefore it is not surprising that Y.” While sociologists disagree over whether a universal human nature even exists, they all agree that it is not an acceptable basis of explanation. Instead, sociology demands that you question why we call some behavior natural, and to look into the social factors which have constructed this “natural” state.

- The “ society argument ” often arises in response to critiques of the above styles of argumentation, and tends to appear in a form such as: “Society made me do it.” Students often think that this is a good sociological argument, since it uses society as the basis for explanation. However, the problem is that the use of the broad concept “society” masks the real workings of the situation, making it next to impossible to build a strong case. This is an example of reification, which is when we turn processes into things. Society is really a process, made up of ongoing interactions at multiple levels of size and complexity, and to turn it into a monolithic thing is to lose all that complexity. People make decisions and choices. Some groups and individuals benefit, while others do not. Identifying these intermediate levels is the basis of sociological analysis.

Although each of these three arguments seems quite different, they all share one common feature: they assume exactly what they need to be explaining. They are excellent starting points, but lousy conclusions.

Once you have developed a working argument, you will next need to find evidence to support your claim. What counts as evidence in a sociology paper? First and foremost, sociology is an empirical discipline. Empiricism in sociology means basing your conclusions on evidence that is documented and collected with as much rigor as possible. This evidence usually draws upon observed patterns and information from collected cases and experiences, not just from isolated, anecdotal reports. Just because your second cousin was able to climb the ladder from poverty to the executive boardroom does not prove that the American class system is open. You will need more systematic evidence to make your claim convincing. Above all else, remember that your opinion alone is not sufficient support for a sociological argument. Even if you are making a theoretical argument, you must be able to point to documented instances of social phenomena that fit your argument. Logic is necessary for making the argument, but is not sufficient support by itself.

Sociological evidence falls into two main groups:

- Quantitative data are based on surveys, censuses, and statistics. These provide large numbers of data points, which is particularly useful for studying large-scale social processes, such as income inequality, population changes, changes in social attitudes, etc.

- Qualitative data, on the other hand, comes from participant observation, in-depth interviews, data and texts, as well as from the researcher’s own impressions and reactions. Qualitative research gives insight into the way people actively construct and find meaning in their world.

Quantitative data produces a measurement of subjects’ characteristics and behavior, while qualitative research generates information on their meanings and practices. Thus, the methods you choose will reflect the type of evidence most appropriate to the questions you ask. If you wanted to look at the importance of race in an organization, a quantitative study might use information on the percentage of different races in the organization, what positions they hold, as well as survey results on people’s attitudes on race. This would measure the distribution of race and racial beliefs in the organization. A qualitative study would go about this differently, perhaps hanging around the office studying people’s interactions, or doing in-depth interviews with some of the subjects. The qualitative researcher would see how people act out their beliefs, and how these beliefs interact with the beliefs of others as well as the constraints of the organization.

Some sociologists favor qualitative over quantitative data, or vice versa, and it is perfectly reasonable to rely on only one method in your own work. However, since each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, combining methods can be a particularly effective way to bolster your argument. But these distinctions are not just important if you have to collect your own data for your paper. You also need to be aware of them even when you are relying on secondary sources for your research. In order to critically evaluate the research and data you are reading, you should have a good understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the different methods.

Units of analysis

Given that social life is so complex, you need to have a point of entry into studying this world. In sociological jargon, you need a unit of analysis. The unit of analysis is exactly that: it is the unit that you have chosen to analyze in your study. Again, this is only a question of emphasis and focus, and not of precedence and importance. You will find a variety of units of analysis in sociological writing, ranging from the individual up to groups or organizations. You should choose yours based on the interests and theoretical assumptions driving your research. The unit of analysis will determine much of what will qualify as relevant evidence in your work. Thus you must not only clearly identify that unit, but also consistently use it throughout your paper.

Let’s look at an example to see just how changing the units of analysis will change the face of research. What if you wanted to study globalization? That’s a big topic, so you will need to focus your attention. Where would you start?

You might focus on individual human actors, studying the way that people are affected by the globalizing world. This approach could possibly include a study of Asian sweatshop workers’ experiences, or perhaps how consumers’ decisions shape the overall system.

Or you might choose to focus on social structures or organizations. This approach might involve looking at the decisions being made at the national or international level, such as the free-trade agreements that change the relationships between governments and corporations. Or you might look into the organizational structures of corporations and measure how they are changing under globalization. Another structural approach would be to focus on the social networks linking subjects together. That could lead you to look at how migrants rely on social contacts to make their way to other countries, as well as to help them find work upon their arrival.

Finally, you might want to focus on cultural objects or social artifacts as your unit of analysis. One fine example would be to look at the production of those tennis shoes the kids seem to like so much. You could look at either the material production of the shoe (tracing it from its sweatshop origins to its arrival on the showroom floor of malls across America) or its cultural production (attempting to understand how advertising and celebrities have turned such shoes into necessities and cultural icons).

Whichever unit of analysis you choose, be careful not to commit the dreaded ecological fallacy. An ecological fallacy is when you assume that something that you learned about the group level of analysis also applies to the individuals that make up that group. So, to continue the globalization example, if you were to compare its effects on the poorest 20% and the richest 20% of countries, you would need to be careful not to apply your results to the poorest and richest individuals.

These are just general examples of how sociological study of a single topic can vary. Because you can approach a subject from several different perspectives, it is important to decide early how you plan to focus your analysis and then stick with that perspective throughout your paper. Avoid mixing units of analysis without strong justification. Different units of analysis generally demand different kinds of evidence for building your argument. You can reconcile the varying levels of analysis, but doing so may require a complex, sophisticated theory, no small feat within the confines of a short paper. Check with your instructor if you are concerned about this happening in your paper.

Typical writing assignments in sociology

So how does all of this apply to an actual writing assignment? Undergraduate writing assignments in sociology may take a number of forms, but they typically involve reviewing sociological literature on a subject; applying or testing a particular concept, theory, or perspective; or producing a small-scale research report, which usually involves a synthesis of both the literature review and application.

The critical review

The review involves investigating the research that has been done on a particular topic and then summarizing and evaluating what you have found. The important task in this kind of assignment is to organize your material clearly and synthesize it for your reader. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but looks for patterns and connections in the literature and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of what others have written on your topic. You want to help your reader see how the information you have gathered fits together, what information can be most trusted (and why), what implications you can derive from it, and what further research may need to be done to fill in gaps. Doing so requires considerable thought and organization on your part, as well as thinking of yourself as an expert on the topic. You need to assume that, even though you are new to the material, you can judge the merits of the arguments you have read and offer an informed opinion of which evidence is strongest and why.

Application or testing of a theory or concept

The application assignment asks you to apply a concept or theoretical perspective to a specific example. In other words, it tests your practical understanding of theories and ideas by asking you to explain how well they apply to actual social phenomena. In order to successfully apply a theory to a new case, you must include the following steps:

- First you need to have a very clear understanding of the theory itself: not only what the theorist argues, but also why they argue that point, and how they justify it. That is, you have to understand how the world works according to this theory and how one thing leads to another.

- Next you should choose an appropriate case study. This is a crucial step, one that can make or break your paper. If you choose a case that is too similar to the one used in constructing the theory in the first place, then your paper will be uninteresting as an application, since it will not give you the opportunity to show off your theoretical brilliance. On the other hand, do not choose a case that is so far out in left field that the applicability is only superficial and trivial. In some ways theory application is like making an analogy. The last thing you want is a weak analogy, or one that is so obvious that it does not give any added insight. Instead, you will want to choose a happy medium, one that is not obvious but that allows you to give a developed analysis of the case using the theory you chose.

- This leads to the last point, which is the analysis. A strong analysis will go beyond the surface and explore the processes at work, both in the theory and in the case you have chosen. Just like making an analogy, you are arguing that these two things (the theory and the example) are similar. Be specific and detailed in telling the reader how they are similar. In the course of looking for similarities, however, you are likely to find points at which the theory does not seem to be a good fit. Do not sweep this discovery under the rug, since the differences can be just as important as the similarities, supplying insight into both the applicability of the theory and the uniqueness of the case you are using.

You may also be asked to test a theory. Whereas the application paper assumes that the theory you are using is true, the testing paper does not makes this assumption, but rather asks you to try out the theory to determine whether it works. Here you need to think about what initial conditions inform the theory and what sort of hypothesis or prediction the theory would make based on those conditions. This is another way of saying that you need to determine which cases the theory could be applied to (see above) and what sort of evidence would be needed to either confirm or disconfirm the theory’s hypothesis. In many ways, this is similar to the application paper, with added emphasis on the veracity of the theory being used.

The research paper

Finally, we reach the mighty research paper. Although the thought of doing a research paper can be intimidating, it is actually little more than the combination of many of the parts of the papers we have already discussed. You will begin with a critical review of the literature and use this review as a basis for forming your research question. The question will often take the form of an application (“These ideas will help us to explain Z.”) or of hypothesis testing (“If these ideas are correct, we should find X when we investigate Y.”). The skills you have already used in writing the other types of papers will help you immensely as you write your research papers.

And so we reach the end of this all-too-brief glimpse into the world of sociological writing. Sociologists can be an idiosyncratic bunch, so paper guidelines and expectations will no doubt vary from class to class, from instructor to instructor. However, these basic guidelines will help you get started.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing About Social Science , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Research Paper

Category: sociology research paper examples.

The sample research papers on sociology have been designed to serve as model papers for most sociology research paper topics . These papers were written by several well-known discipline figures and emerging younger scholars who provide authoritative overviews coupled with insightful discussion that will quickly familiarize researchers and students alike with fundamental and detailed information for each sociology topic.

Browse sociology research paper examples below.

How to Write Sociology Papers

| Writing Sociology Papers |

Writing Sociology Papers

Writing is one of the most difficult and most rewarding of all scholarly activities. Few of us, students or professors, find it easy to do. The pain of writing comes largely as a result of bad writing habits. No one can write a good paper in one draft on the night before the paper is due. The following steps will not guarantee a good paper, but they will eliminate the most common problems encountered in bad papers.

1. Select a topic early. Start thinking about topics as soon as the paper is assigned and get approval of your topic choice from the professor before starting the research on the paper. When choosing a topic, think critically. Remember that writing a good sociology paper starts with asking a good sociological question.

2. Give yourself adequate time to do the research. You will need time to think through the things you read or to explore the data you analyze. Also, things will go wrong and you will need time to recover. The one book or article which will help make your paper the best one you've ever done will be unavailable in the library and you have to wait for it to be recalled or to be found through interlibrary loan. Or perhaps the computer will crash and destroy a whole afternoon's work. These things happen to all writers. Allow enough time to finish your paper even if such things happen.

3. Work from an outline. Making an outline breaks the task down into smaller bits which do not seem as daunting. This allows you to keep an image of the whole in mind even while you work on the parts. You can show the outline to your professor and get advice while you are writing a paper rather than after you turn it in for a final grade.

4. Stick to the point. Each paper should contain one key idea which you can state in a sentence or paragraph. The paper will provide the argument and evidence to support that point. Papers should be compact with a strong thesis and a clear line of argument. Avoid digressions and padding.

5. Make more than one draft. First drafts are plagued with confusion, bad writing, omissions, and other errors. So are second drafts, but not to the same extent. Get someone else to read it. Even your roommate who has never had a sociology course may be able to point out unclear parts or mistakes you have missed. The best papers have been rewritten, in part or in whole, several times. Few first draft papers will receive high grades.

6. Proofread the final copy, correcting any typographical errors. A sloppily written, uncorrected paper sends a message that the writer does not care about his or her work. If the writer does not care about the paper, why should the reader?

Such rules may seem demanding and constricting, but they provide the liberation of self discipline. By choosing a topic, doing the research, and writing the paper you take control over a vital part of your own education. What you learn in the process, if you do it conscientiously, is far greater that what shows up in the paper or what is reflected in the grade.

EMPIRICAL RESEARCH PAPERS

Some papers have an empirical content that needs to be handled differently than a library research paper. Empirical papers report some original research. It may be based on participant observation, on secondary analysis of social surveys, or some other source. The outline below presents a general form that most articles published in sociology journals follow. You should get specific instructions from professors who assign empirical research papers.

1. Introduction and statement of the research question.

2. Review of previous research and theory.

3. Description of data collection including sample characteristics and the reliability and validity of techniques employed.

4. Presentation of the results of data analysis including explicit reference to the implications the data have for the research question.

5. Conclusion which ties the loose ends of the analysis back to the research question.

6. End notes (if any).

7. References cited in the paper.

Tables and displays of quantitative information should follow the rules set down by Tufte in the work listed below.

Tufte, Edward. 1983. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information . Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press. (lib QA 90 T93 1983)

How To Write A Sociology Research Paper Outline

Sociology can be both a very interesting topic, as well as a very confusing one. For those who are tasked with writing a sociology paper, there is a starting point that you must begin with: Sociology research paper outline. Without this, you’re going to find it challenging to keep yourself (as well as your paper) on track. With that in mind, you can learn how to take the first step of writing a sociology paper.

What is a Sociology Research Paper?

Of course, if you want to write sociological papers, you’re going to need to look at both the writing aspect as well as the more in-depth understanding of the topic that you’ll be covering. If you find yourself worried and keep searching the internet for “ buy research paper online ,” relax. It’s simple. To make it easy to understand, we’ll look at the two parts.

The first ingredient, for a sociology research paper, is, of course, sociology. If you’re writing about it, it’s likely you know what the topic is already. However, we’ll go ahead and give it a concise definition: Sociology is the study of human society. It covers how we developed it, the structure, and its crucial functions. That’s a very broad definition, but it’s all you need to know to get ready to write your sociology term paper.

The second part of this project is going to be the paper part. You’re likely as familiar with the definition of papers as you are with the meaning of sociology. In this instance, a concrete example of what you’ll need to provide is difficult. Most have the same basic makeup such as arguments along with supporting facts as well as the main thesis.

Sociology Paper Format

When writing in sociology class, whether it’s for a term paper or just a general essay, sociology paper will follow the same basic format: An introduction, several body paragraphs, and a conclusion. For those wondering how to write a research summary , this is a secure place to start.

The introduction is where you’ll state to your reader the topic that you will be writing about. As well, you should give the purpose of the piece. Make the reason for the paper clear. It shouldn’t be dull; you need to keep it interesting, so they don’t zone out halfway through. It should also be informative. What good is a paper that doesn’t teach? If you’re worried about how to choose a topic for a research paper, it’s not as difficult as it seems. Simply searching for “research question sociology” can get you there. Even if it isn’t assigned, you can usually choose something involving.

The body paragraphs are what most would consider being “the paper.” This consists of multiple paragraphs and gives individual ideas along with the supporting evidence for them, which is what will make your sociology papers and their arguments strong. Each part should cover one topic and provide all of the information that the reader would need for it. Good investigations make it easy to understand what’s being written about, after all. There should be at least three, but not many more. You don’t want to lose their interest, after all!

The last part of your paper is going to be the conclusion. This is usually relatively brief but delivers the final consensus of your work. You should make it very plain focus readers’ attention on your findings, how your supporting evidence (found in the body paragraphs) led to it, and what it means. There should be no misunderstandings by the time the conclusion is finished.

Sociology Research Paper Outline Template

There are three types of sociology paper outline that you can use: Traditional, conceptual, and post-draft. All of them are different and have their uses. Conceptual outlines are great for those who like to think outside of the box. Instead of just writing, you’re drawing! Here, a circle represents the source, a rectangle – the central theme, and a triangle – the conclusion. They are all interconnected with lines and arrows. A post-draft outline involves writing out what you want to cover on a piece of paper. Do this as the ideas come to you. Write how these are supported. You don’t have to worry about being orderly; just get everything down! Afterward, you can neatly arrange everything by bullet points. By far, the most widely used and best-known is what is called “the traditional outline.” Here, you break down the paper by the format you’ll be writing in. There is generally an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The body paragraphs contain both the main idea for the paragraph and the supporting information for it. Just like in your essay. Generally, it is presented as headings (such as Introduction, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusion shown below) with the numbered or lettered lists beneath them that contain the information needed. This is just a summary, so it should be condensed. You can be a bit lost with it as long as it makes sense to you. Since it’s the most widely used, that’s what we’ll focus on. You can see an example of one below.

Introduction

- What is the topic of your paper? What is the thesis statement or the main question? Make sure to include it here and to make it clear to the reader.

- What do you intend to do in this paper? Are you arguing for or against something? Or are you simply informing the reader? You should state your intended purpose.

Body Paragraphs

- This is where you will discuss your topic. Try to keep it clear and concise and not overly broad.

- Include any information that supports the topic.

- What is the summary of your paper? What, exactly, did you cover while writing it? Summarize it fairly, but briefly. You don’t need to restate the entire thing!

- What were your conclusions? Lay them out plainly, so that everyone can understand them. Make sure they were supported.

When it’s time to write your sociological paper outline, you need to put some thoughts and efforts into it. A good framework will keep your writing on track; keep your information organized and in one place. Make everything step-by-step through the writing process until you can back up your findings at the end. With the right amount of planning ahead as well as work, you can turn a daunting task into the one that can be easily managed.

Related posts:

- 6 Step Process for Essay Writing

- How to Write an Appendix for a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

- Footnotes 101: A Guide to Proper Formatting

Improve your writing with our guides

How to Write a Scholarship Essay

Definition Essay: The Complete Guide with Essay Topics and Examples

Critical Essay: The Complete Guide. Essay Topics, Examples and Outlines

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Describe the function and importance of an interpretive framework.

- Describe the differences in accuracy, reliability and validity in a research study.

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries, in families that have enlightened family members, and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of six prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scientific scholarship.

Sociological research does not reduce knowledge to right or wrong facts. Results of studies tend to provide people with insights they did not have before—explanations of human behaviors and social practices and access to knowledge of other cultures, rituals and beliefs, or trends and attitudes.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This does not mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in collecting and analyzing data in research studies.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963). Typically, the scientific method has 6 steps which are described below.

Step 1: Ask a Question or Find a Research Topic

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?”

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study crime, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, prison information, interviews with criminals, guards, wardens, etc. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variables (IV) , which are the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV) , which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

| Hypothesis | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. | Affordable Housing | Homeless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighborhood. | Police Patrol Presence | Safer Neighborhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of media coverage, the higher the public awareness. | Observation | Public Awareness |

Taking an example from Table 12.1, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Note, however, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. A sociologist might predict that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying related two topics or variables is not enough. Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis.

Step 4: Design and Conduct a Study

Researchers design studies to maximize reliability , which refers to how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced. Reliability increases the likelihood that what happens to one person will happen to all people in a group or what will happen in one situation will happen in another. Cooking is a science. When you follow a recipe and measure ingredients with a cooking tool, such as a measuring cup, the same results is obtained as long as the cook follows the same recipe and uses the same type of tool. The measuring cup introduces accuracy into the process. If a person uses a less accurate tool, such as their hand, to measure ingredients rather than a cup, the same result may not be replicated. Accurate tools and methods increase reliability.

Researchers also strive for validity , which refers to how well the study measures what it was designed to measure. To produce reliable and valid results, sociologists develop an operational definition , that is, they define each concept, or variable, in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept. By operationalizing the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. Moreover, researchers can determine whether the experiment or method validly represent the phenomenon they intended to study.

A study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, might define “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” However, one researcher might define a “good” grade as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for “good.” For the results to be replicated and gain acceptance within the broader scientific community, researchers would have to use a standard operational definition. These definitions set limits and establish cut-off points that ensure consistency and replicability in a study.

We will explore research methods in greater detail in the next section of this chapter.

Step 5: Draw Conclusions

After constructing the research design, sociologists collect, tabulate or categorize, and analyze data to formulate conclusions. If the analysis supports the hypothesis, researchers can discuss the implications of the results for the theory or policy solution that they were addressing. If the analysis does not support the hypothesis, researchers may consider repeating the experiment or think of ways to improve their procedure.

However, even when results contradict a sociologist’s prediction of a study’s outcome, these results still contribute to sociological understanding. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns. In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding rewarding careers. While many assume that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results may substantiate or contradict it.

Sociologists carefully keep in mind how operational definitions and research designs impact the results as they draw conclusions. Consider the concept of “increase of crime,” which might be defined as the percent increase in crime from last week to this week, as in the study of Swedish crime discussed above. Yet the data used to evaluate “increase of crime” might be limited by many factors: who commits the crime, where the crimes are committed, or what type of crime is committed. If the data is gathered for “crimes committed in Houston, Texas in zip code 77021,” then it may not be generalizable to crimes committed in rural areas outside of major cities like Houston. If data is collected about vandalism, it may not be generalizable to assault.

Step 6: Report Results

Researchers report their results at conferences and in academic journals. These results are then subjected to the scrutiny of other sociologists in the field. Before the conclusions of a study become widely accepted, the studies are often repeated in the same or different environments. In this way, sociological theories and knowledge develops as the relationships between social phenomenon are established in broader contexts and different circumstances.

Interpretive Framework

While many sociologists rely on empirical data and the scientific method as a research approach, others operate from an interpretive framework . While systematic, this approach doesn’t follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to find generalizable results. Instead, an interpretive framework, sometimes referred to as an interpretive perspective , seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, which leads to in-depth knowledge or understanding about the human experience.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings. Rather than formulating a hypothesis and method for testing it, an interpretive researcher will develop approaches to explore the topic at hand that may involve a significant amount of direct observation or interaction with subjects including storytelling. This type of researcher learns through the process and sometimes adjusts the research methods or processes midway to optimize findings as they evolve.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociology focuses on deconstruction of existing sociological research and theory. Informed by the work of Karl Marx, scholars known collectively as the Frankfurt School proposed that social science, as much as any academic pursuit, is embedded in the system of power constituted by the set of class, caste, race, gender, and other relationships that exist in the society. Consequently, it cannot be treated as purely objective. Critical sociologists view theories, methods, and the conclusions as serving one of two purposes: they can either legitimate and rationalize systems of social power and oppression or liberate humans from inequality and restriction on human freedom. Deconstruction can involve data collection, but the analysis of this data is not empirical or positivist.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/2-1-approaches-to-sociological-research

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Quick links

- Directories

- Make a Gift

Writing Papers That Apply Sociological Theories or Perspectives

This document is intended as an additional resource for undergraduate students taking sociology courses at UW. It is not intended to replace instructions from your professors and TAs. In all cases follow course-specific assignment instructions, and consult your TA or professor if you have questions.

About These Assignments

Theory application assignments are a common type of analytical writing assigned in sociology classes. Many instructors expect you to apply sociological theories (sometimes called "perspectives" or "arguments") to empirical phenomena. [1] There are different ways to do this, depending upon your objectives, and of course, the specifics of each assignment. You can choose cases that confirm (support), disconfirm (contradict), [2] or partially confirm any theory.

How to Apply Theory to Empirical Phenomena

Theory application assignments generally require you to look at empirical phenomena through the lens of theory. Ask yourself, what would the theory predict ("have to say") about a particular situation. According to the theory, if particular conditions are present or you see a change in a particular variable, what outcome should you expect?

Generally, a first step in a theory application assignment is to make certain you understand the theory! You should be able to state the theory (the author's main argument) in a sentence or two. Usually, this means specifying the causal relationship (X—>Y) or the causal model (which might involve multiple variables and relationships).

For those taking sociological theory classes, in particular, you need to be aware that theories are constituted by more than causal relationships. Depending upon the assignment, you may be asked to specify the following:

- Causal Mechanism: This is a detailed explanation about how X—>Y, often made at a lower level of analysis (i.e., using smaller units) than the causal relationship.

- Level of Analysis: Macro-level theories refer to society- or group-level causes and processes; micro-level theories address individual-level causes and processes.

- Scope Conditions: These are parameters or boundaries specified by the theorist that identify the types of empirical phenomena to which the theory applies.

- Assumptions: Most theories begin by assuming certain "facts." These often concern the bases of human behavior: for example, people are inherently aggressive or inherently kind, people act out of self-interest or based upon values, etc.

Theories vary in terms of whether they specify assumptions, scope conditions and causal mechanisms. Sometimes they can only be inferred: when this is the case, be clear about that in your paper.

Clearly understanding all the parts of a theory helps you ensure that you are applying the theory correctly to your case. For example, you can ask whether your case fits the theory's assumptions and scope conditions. Most importantly, however, you should single out the main argument or point (usually the causal relationship and mechanism) of the theory. Does the theorist's key argument apply to your case? Students often go astray here by latching onto an inconsequential or less important part of the theory reading, showing the relationship to their case, and then assuming they have fully applied the theory.

Using Evidence to Make Your Argument

Theory application papers involve making a claim or argument based on theory, supported by empirical evidence. [3] There are a few common problems that students encounter while writing these types of assignments: unsubstantiated claims/generalizations; "voice" issues or lack of attribution; excessive summarization/insufficient analysis. Each class of problem is addressed below, followed by some pointers for choosing "cases," or deciding upon the empirical phenomenon to which you will apply the theoretical perspective or argument (including where to find data).

A common problem seen in theory application assignments is failing to substantiate claims, or making a statement that is not backed up with evidence or details ("proof"). When you make a statement or a claim, ask yourself, "How do I know this?" What evidence can you marshal to support your claim? Put this evidence in your paper (and remember to cite your sources). Similarly, be careful about making overly strong or broad claims based on insufficient evidence. For example, you probably don't want to make a claim about how Americans feel about having a black president based on a poll of UW undergraduates. You may also want to be careful about making authoritative (conclusive) claims about broad social phenomena based on a single case study.

In addition to un- or under-substantiated claims, another problem that students often encounter when writing these types of papers is lack of clarity regarding "voice," or whose ideas they are presenting. The reader is left wondering whether a given statement represents the view of the theorist, the student, or an author who wrote about the case. Be careful to identify whose views and ideas you are presenting. For example, you could write, "Marx views class conflict as the engine of history;" or, "I argue that American politics can best be understood through the lens of class conflict;" [4] or, "According to Ehrenreich, Walmart employees cannot afford to purchase Walmart goods."

Another common problem that students encounter is the trap of excessive summarization. They spend the majority of their papers simply summarizing (regurgitating the details) of a case—much like a book report. One way to avoid this is to remember that theory indicates which details (or variables) of a case are most relevant, and to focus your discussion on those aspects. A second strategy is to make sure that you relate the details of the case in an analytical fashion. You might do this by stating an assumption of Marxist theory, such as "man's ideas come from his material conditions," and then summarizing evidence from your case on that point. You could organize the details of the case into paragraphs and start each paragraph with an analytical sentence about how the theory relates to different aspects of the case.

Some theory application papers require that you choose your own case (an empirical phenomenon, trend, situation, etc.), whereas others specify the case for you (e.g., ask you to apply conflict theory to explain some aspect of globalization described in an article). Many students find choosing their own case rather challenging. Some questions to guide your choice are:

- Can I obtain sufficient data with relative ease on my case?

- Is my case specific enough? If your subject matter is too broad or abstract, it becomes both difficult to gather data and challenging to apply the theory.

- Is the case an interesting one? Professors often prefer that you avoid examples used by the theorist themselves, those used in lectures and sections, and those that are extremely obvious.

Where You Can Find Data

Data is collected by many organizations (e.g., commercial, governmental, nonprofit, academic) and can frequently be found in books, reports, articles, and online sources. The UW libraries make your job easy: on the front page of the library website ( www.lib.washington.edu ), in the left hand corner you will see a list of options under the heading "Find It" that allows you to go directly to databases, specific online journals, newspapers, etc. For example, if you are choosing a historical case, you might want to access newspaper articles. This has become increasingly easy to do, as many are now online through the UW library. For example, you can search The New York Times and get full-text online for every single issue from 1851 through today! If you are interested in interview or observational data, you might try to find books or articles that are case-studies on your topic of interest by conducting a simple keyword search of the UW library book holdings, or using an electronic database, such as JSTOR or Sociological Abstracts. Scholarly articles are easy to search through, since they contain abstracts, or paragraphs that summarize the topic, relevant literature, data and methods, and major findings. When using JSTOR, you may want to limit your search to sociology (which includes 70 journals) and perhaps political science; this database retrieves full-text articles. Sociological Abstracts will cast a wider net searching many more sociology journals, but the article may or may not be available online (find out by clicking "check for UW holdings"). A final word about using academic articles for data: remember that you need to cite your sources, and follow the instructions of your assignment. This includes making your own argument about your case, not using an argument you find in a scholarly article.

In addition, there are many data sources online. For example, you can get data from the US census, including for particular neighborhoods, from a number of cites. You can get some crime data online: the Seattle Police Department publishes several years' worth of crime rates. There are numerous cites on public opinion, including gallup.com. There is an online encyclopedia on Washington state history, including that of individual Seattle neighborhoods ( www.historylink.org ). These are just a couple options: a simple google search will yield hundreds more. Finally, remember that librarian reference desks are expert on data sources, and that you can call, email, or visit in person to ask about what data is available on your particular topic. You can chat with a librarian 24 hours a day online, as well (see the "Ask Us!" link on the front page of UW libraries website for contact information).

[1] By empirical phenomena, we mean some sort of observed, real-world conditions. These include societal trends, events, or outcomes. They are sometimes referred to as "cases." Return to Reading