- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Quality improvement...

Quality improvement into practice

Read the full collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Adam Backhouse , quality improvement programme lead 1 ,

- Fatai Ogunlayi , public health specialty registrar 2

- 1 North London Partners in Health and Care, Islington CCG, London N1 1TH, UK

- 2 Institute of Applied Health Research, Public Health, University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

- Correspondence to: A Backhouse adam.backhouse{at}nhs.net

What you need to know

Thinking of quality improvement (QI) as a principle-based approach to change provides greater clarity about ( a ) the contribution QI offers to staff and patients, ( b ) how to differentiate it from other approaches, ( c ) the benefits of using QI together with other change approaches

QI is not a silver bullet for all changes required in healthcare: it has great potential to be used together with other change approaches, either concurrently (using audit to inform iterative tests of change) or consecutively (using QI to adapt published research to local context)

As QI becomes established, opportunities for these collaborations will grow, to the benefit of patients.

The benefits to front line clinicians of participating in quality improvement (QI) activity are promoted in many health systems. QI can represent a valuable opportunity for individuals to be involved in leading and delivering change, from improving individual patient care to transforming services across complex health and care systems. 1

However, it is not clear that this promotion of QI has created greater understanding of QI or widespread adoption. QI largely remains an activity undertaken by experts and early adopters, often in isolation from their peers. 2 There is a danger of a widening gap between this group and the majority of healthcare professionals.

This article will make it easier for those new to QI to understand what it is, where it fits with other approaches to improving care (such as audit or research), when best to use a QI approach, making it easier to understand the relevance and usefulness of QI in delivering better outcomes for patients.

How this article was made

AB and FO are both specialist quality improvement practitioners and have developed their expertise working in QI roles for a variety of UK healthcare organisations. The analysis presented here arose from AB and FO’s observations of the challenges faced when introducing QI, with healthcare providers often unable to distinguish between QI and other change approaches, making it difficult to understand what QI can do for them.

How is quality improvement defined?

There are many definitions of QI ( box 1 ). The BMJ ’s Quality Improvement series uses the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges definition. 6 Rather than viewing QI as a single method or set of tools, it can be more helpful to think of QI as based on a set of principles common to many of these definitions: a systematic continuous approach that aims to solve problems in healthcare, improve service provision, and ultimately provide better outcomes for patients.

Definitions of quality improvement

Improvement in patient outcomes, system performance, and professional development that results from a combined, multidisciplinary approach in how change is delivered. 3

The delivery of healthcare with improved outcomes and lower cost through continuous redesigning of work processes and systems. 4

Using a systematic change method and strategies to improve patient experience and outcome. 5

To make a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness, and experience of care by using understanding of our complex healthcare environment, applying a systematic approach, and designing, testing, and implementing changes using real time measurement for improvement. 6

In this article we discuss QI as an approach to improving healthcare that follows the principles outlined in box 2 ; this may be a useful reference to consider how particular methods or tools could be used as part of a QI approach.

Principles of QI

Primary intent— To bring about measurable improvement to a specific aspect of healthcare delivery, often with evidence or theory of what might work but requiring local iterative testing to find the best solution. 7

Employing an iterative process of testing change ideas— Adopting a theory of change which emphasises a continuous process of planning and testing changes, studying and learning from comparing the results to a predicted outcome, and adapting hypotheses in response to results of previous tests. 8 9

Consistent use of an agreed methodology— Many different QI methodologies are available; commonly cited methodologies include the Model for Improvement, Lean, Six Sigma, and Experience-based Co-design. 4 Systematic review shows that the choice of tools or methodologies has little impact on the success of QI provided that the chosen methodology is followed consistently. 10 Though there is no formal agreement on what constitutes a QI tool, it would include activities such as process mapping that can be used within a range of QI methodological approaches. NHS Scotland’s Quality Improvement Hub has a glossary of commonly used tools in QI. 11

Empowerment of front line staff and service users— QI work should engage staff and patients by providing them with the opportunity and skills to contribute to improvement work. Recognition of this need often manifests in drives from senior leadership or management to build QI capability in healthcare organisations, but it also requires that frontline staff and service users feel able to make use of these skills and take ownership of improvement work. 12

Using data to drive improvement— To drive decision making by measuring the impact of tests of change over time and understanding variation in processes and outcomes. Measurement for improvement typically prioritises this narrative approach over concerns around exactness and completeness of data. 13 14

Scale-up and spread, with adaptation to context— As interventions tested using a QI approach are scaled up and the degree of belief in their efficacy increases, it is desirable that they spread outward and be adopted by others. Key to successful diffusion of improvement is the adaption of interventions to new environments, patient and staff groups, available resources, and even personal preferences of healthcare providers in surrounding areas, again using an iterative testing approach. 15 16

What other approaches to improving healthcare are there?

Taking considered action to change healthcare for the better is not new, but QI as a distinct approach to improving healthcare is a relatively recent development. There are many well established approaches to evaluating and making changes to healthcare services in use, and QI will only be adopted more widely if it offers a new perspective or an advantage over other approaches in certain situations.

A non-systematic literature scan identified the following other approaches for making change in healthcare: research, clinical audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation. We also identified innovation as an important catalyst for change, but we did not consider it an approach to evaluating and changing healthcare services so much as a catch-all term for describing the development and introduction of new ideas into the system. A summary of the different approaches and their definition is shown in box 3 . Many have elements in common with QI, but there are important difference in both intent and application. To be useful to clinicians and managers, QI must find a role within healthcare that complements research, audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation while retaining the core principles that differentiate it from these approaches.

Alternatives to QI

Research— The attempt to derive generalisable new knowledge by addressing clearly defined questions with systematic and rigorous methods. 17

Clinical audit— A way to find out if healthcare is being provided in line with standards and to let care providers and patients know where their service is doing well, and where there could be improvements. 18

Service evaluation— A process of investigating the effectiveness or efficiency of a service with the purpose of generating information for local decision making about the service. 19

Clinical transformation— An umbrella term for more radical approaches to change; a deliberate, planned process to make dramatic and irreversible changes to how care is delivered. 20

Innovation— To develop and deliver new or improved health policies, systems, products and technologies, and services and delivery methods that improve people’s health. Health innovation responds to unmet needs by employing new ways of thinking and working. 21

Why do we need to make this distinction for QI to succeed?

Improvement in healthcare is 20% technical and 80% human. 22 Essential to that 80% is clear communication, clarity of approach, and a common language. Without this shared understanding of QI as a distinct approach to change, QI work risks straying from the core principles outlined above, making it less likely to succeed. If practitioners cannot communicate clearly with their colleagues about the key principles and differences of a QI approach, there will be mismatched expectations about what QI is and how it is used, lowering the chance that QI work will be effective in improving outcomes for patients. 23

There is also a risk that the language of QI is adopted to describe change efforts regardless of their fidelity to a QI approach, either due to a lack of understanding of QI or a lack of intention to carry it out consistently. 9 Poor fidelity to the core principles of QI reduces its effectiveness and makes its desired outcome less likely, leading to wasted effort by participants and decreasing its credibility. 2 8 24 This in turn further widens the gap between advocates of QI and those inclined to scepticism, and may lead to missed opportunities to use QI more widely, consequently leading to variation in the quality of patient care.

Without articulating the differences between QI and other approaches, there is a risk of not being able to identify where a QI approach can best add value. Conversely, we might be tempted to see QI as a “silver bullet” for every healthcare challenge when a different approach may be more effective. In reality it is not clear that QI will be fit for purpose in tackling all of the wicked problems of healthcare delivery and we must be able to identify the right tool for the job in each situation. 25 Finally, while different approaches will be better suited to different types of challenge, not having a clear understanding of how approaches differ and complement each other may mean missed opportunities for multi-pronged approaches to improving care.

What is the relationship between QI and other approaches such as audit?

Academic journals, healthcare providers, and “arms-length bodies” have made various attempts to distinguish between the different approaches to improving healthcare. 19 26 27 28 However, most comparisons do not include QI or compare QI to only one or two of the other approaches. 7 29 30 31 To make it easier for people to use QI approaches effectively and appropriately, we summarise the similarities, differences, and crossover between QI and other approaches to tackling healthcare challenges ( fig 1 ).

How quality improvement interacts with other approaches to improving healthcare

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

QI and research

Research aims to generate new generalisable knowledge, while QI typically involves a combination of generating new knowledge or implementing existing knowledge within a specific setting. 32 Unlike research, including pragmatic research designed to test effectiveness of interventions in real life, QI does not aim to provide generalisable knowledge. In common with QI, research requires a consistent methodology. This method is typically used, however, to prove or disprove a fixed hypothesis rather than the adaptive hypotheses developed through the iterative testing of ideas typical of QI. Both research and QI are interested in the environment where work is conducted, though with different intentions: research aims to eliminate or at least reduce the impact of many variables to create generalisable knowledge, whereas QI seeks to understand what works best in a given context. The rigour of data collection and analysis required for research is much higher; in QI a criterion of “good enough” is often applied.

Relationship with QI

Though the goal of clinical research is to develop new knowledge that will lead to changes in practice, much has been written on the lag time between publication of research evidence and system-wide adoption, leading to delays in patients benefitting from new treatments or interventions. 33 QI offers a way to iteratively test the conditions required to adapt published research findings to the local context of individual healthcare providers, generating new knowledge in the process. Areas with little existing knowledge requiring further research may be identified during improvement activities, which in turn can form research questions for further study. QI and research also intersect in the field of improvement science, the academic study of QI methods which seeks to ensure QI is carried out as effectively as possible. 34

Scenario: QI for translational research

Newly published research shows that a particular physiotherapy intervention is more clinically effective when delivered in short, twice-daily bursts rather than longer, less frequent sessions. A team of hospital physiotherapists wish to implement the change but are unclear how they will manage the shift in workload and how they should introduce this potentially disruptive change to staff and to patients.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article?

Adopting a QI approach, the team realise that, although the change they want to make is already determined, the way in which it is introduced and adapted to their wards is for them to decide. They take time to explain the benefits of the change to colleagues and their current patients, and ask patients how they would best like to receive their extra physiotherapy sessions.

The change is planned and tested for two weeks with one physiotherapist working with a small number of patients. Data are collected each day, including reasons why sessions were missed or refused. The team review the data each day and make iterative changes to the physiotherapist’s schedule, and to the times of day the sessions are offered to patients. Once an improvement is seen, this new way of working is scaled up to all of the patients on the ward.

The findings of the work are fed into a service evaluation of physiotherapy provision across the hospital, which uses the findings of the QI work to make recommendations about how physiotherapy provision should be structured in the future. People feel more positive about the change because they know colleagues who have already made it work in practice.

QI and clinical audit

Clinical audit is closely related to QI: it is often used with the intention of iteratively improving the standard of healthcare, albeit in relation to a pre-determined standard of best practice. 35 When used iteratively, interspersed with improvement action, the clinical audit cycle adheres to many of the principles of QI. However, in practice clinical audit is often used by healthcare organisations as an assurance function, making it less likely to be carried out with a focus on empowering staff and service users to make changes to practice. 36 Furthermore, academic reviews of audit programmes have shown audit to be an ineffective approach to improving quality due to a focus on data collection and analysis without a well developed approach to the action section of the audit cycle. 37 Clinical audits, such as the National Clinical Audit Programme in the UK (NCAPOP), often focus on the management of specific clinical conditions. QI can focus on any part of service delivery and can take a more cross-cutting view which may identify issues and solutions that benefit multiple patient groups and pathways. 30

Audit is often the first step in a QI process and is used to identify improvement opportunities, particularly where compliance with known standards for high quality patient care needs to be improved. Audit can be used to establish a baseline and to analyse the impact of tests of change against the baseline. Also, once an improvement project is under way, audit may form part of rapid cycle evaluation, during the iterative testing phase, to understand the impact of the idea being tested. Regular clinical audit may be a useful assurance tool to help track whether improvements have been sustained over time.

Scenario: Audit and QI

A foundation year 2 (FY2) doctor is asked to complete an audit of a pre-surgical pathway by looking retrospectively through patient documentation. She concludes that adherence to best practice is mixed and recommends: “Remind the team of the importance of being thorough in this respect and re-audit in 6 months.” The results are presented at an audit meeting, but a re-audit a year later by a new FY2 doctor shows similar results.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this paper?

Contrast the above with a team-led, rapid cycle audit in which everyone contributes to collecting and reviewing data from the previous week, discussed at a regular team meeting. Though surgical patients are often transient, their experience of care and ideas for improvement are captured during discharge conversations. The team identify and test several iterative changes to care processes. They document and test these changes between audits, leading to sustainable change. Some of the surgeons involved work across multiple hospitals, and spread some of the improvements, with the audit tool, as they go.

QI and service evaluation

In practice, service evaluation is not subject to the same rigorous definition or governance as research or clinical audit, meaning that there are inconsistencies in the methodology for carrying it out. While the primary intent for QI is to make change that will drive improvement, the primary intent for evaluation is to assess the performance of current patient care. 38 Service evaluation may be carried out proactively to assess a service against its stated aims or to review the quality of patient care, or may be commissioned in response to serious patient harm or red flags about service performance. The purpose of service evaluation is to help local decision makers determine whether a service is fit for purpose and, if necessary, identify areas for improvement.

Service evaluation may be used to initiate QI activity by identifying opportunities for change that would benefit from a QI approach. It may also evaluate the impact of changes made using QI, either during the work or after completion to assess sustainability of improvements made. Though likely planned as separate activities, service evaluation and QI may overlap and inform each other as they both develop. Service evaluation may also make a judgment about a service’s readiness for change and identify any barriers to, or prerequisites for, carrying out QI.

QI and clinical transformation

Clinical transformation involves radical, dramatic, and irreversible change—the sort of change that cannot be achieved through continuous improvement alone. As with service evaluation, there is no consensus on what clinical transformation entails, and it may be best thought of as an umbrella term for the large scale reform or redesign of clinical services and the non-clinical services that support them. 20 39 While it is possible to carry out transformation activity that uses elements of QI approach, such as effective engagement of the staff and patients involved, QI which rests on iterative test of change cannot have a transformational approach—that is, one-off, irreversible change.

There is opportunity to use QI to identify and test ideas before full scale clinical transformation is implemented. This has the benefit of engaging staff and patients in the clinical transformation process and increasing the degree of belief that clinical transformation will be effective or beneficial. Transformation activity, once completed, could be followed up with QI activity to drive continuous improvement of the new process or allow adaption of new ways of working. As interventions made using QI are scaled up and spread, the line between QI and transformation may seem to blur. The shift from QI to transformation occurs when the intention of the work shifts away from continuous testing and adaptation into the wholesale implementation of an agreed solution.

Scenario: QI and clinical transformation

An NHS trust’s human resources (HR) team is struggling to manage its junior doctor placements, rotas, and on-call duties, which is causing tension and has led to concern about medical cover and patient safety out of hours. A neighbouring trust has launched a smartphone app that supports clinicians and HR colleagues to manage these processes with the great success.

This problem feels ripe for a transformation approach—to launch the app across the trust, confident that it will solve the trust’s problems.

Before continuing reading think about your own organisation— What do you think will happen, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article for this situation?

Outcome without QI

Unfortunately, the HR team haven’t taken the time to understand the underlying problems with their current system, which revolve around poor communication and clarity from the HR team, based on not knowing who to contact and being unable to answer questions. HR assume that because the app has been a success elsewhere, it will work here as well.

People get excited about the new app and the benefits it will bring, but no consideration is given to the processes and relationships that need to be in place to make it work. The app is launched with a high profile campaign and adoption is high, but the same issues continue. The HR team are confused as to why things didn’t work.

Outcome with QI

Although the app has worked elsewhere, rolling it out without adapting it to local context is a risk – one which application of QI principles can mitigate.

HR pilot the app in a volunteer specialty after spending time speaking to clinicians to better understand their needs. They carry out several tests of change, ironing out issues with the process as they go, using issues logged and clinician feedback as a source of data. When they are confident the app works for them, they expand out to a directorate, a division, and finally the transformational step of an organisation-wide rollout can be taken.

Education into practice

Next time when faced with what looks like a quality improvement (QI) opportunity, consider asking:

How do you know that QI is the best approach to this situation? What else might be appropriate?

Have you considered how to ensure you implement QI according to the principles described above?

Is there opportunity to use other approaches in tandem with QI for a more effective result?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

This article was conceived and developed in response to conversations with clinicians and patients working together on co-produced quality improvement and research projects in a large UK hospital. The first iteration of the article was reviewed by an expert patient, and, in response to their feedback, we have sought to make clearer the link between understanding the issues raised and better patient care.

Contributors: This work was initially conceived by AB. AB and FO were responsible for the research and drafting of the article. AB is the guarantor of the article.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ , including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Olsson-Brown A

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Batalden PB ,

- Berwick D ,

- Øvretveit J

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

- Nelson WA ,

- McNicholas C ,

- Woodcock T ,

- Alderwick H ,

- ↵ NHS Scotland Quality Improvement Hub. Quality improvement glossary of terms. http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/qi-basics/quality-improvement-glossary-of-terms.aspx .

- McNicol S ,

- Solberg LI ,

- Massoud MR ,

- Albrecht Y ,

- Illingworth J ,

- Department of Health

- ↵ NHS England. Clinical audit. https://www.england.nhs.uk/clinaudit/ .

- Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership

- McKinsey Hospital Institute

- ↵ World Health Organization. WHO Health Innovation Group. 2019. https://www.who.int/life-course/about/who-health-innovation-group/en/ .

- Sheffield Microsystem Coaching Academy

- Davidoff F ,

- Leviton L ,

- Taylor MJ ,

- Nicolay C ,

- Tarrant C ,

- Twycross A ,

- ↵ University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. Is your study research, audit or service evaluation. http://www.uhbristol.nhs.uk/research-innovation/for-researchers/is-it-research,-audit-or-service-evaluation/ .

- ↵ University of Sheffield. Differentiating audit, service evaluation and research. 2006. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.158539!/file/AuditorResearch.pdf .

- ↵ Royal College of Radiologists. Audit and quality improvement. https://www.rcr.ac.uk/clinical-radiology/audit-and-quality-improvement .

- Gundogan B ,

- Finkelstein JA ,

- Brickman AL ,

- Health Foundation

- Johnston G ,

- Crombie IK ,

- Davies HT ,

- Hillman T ,

- ↵ NHS Health Research Authority. Defining research. 2013. https://www.clahrc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/defining-research.pdf .

- Log In / Register

- Education Platform

- Newsletter Sign Up

Case Studies

- How to Improve

- Improvement Stories

- Publications

- IHI White Papers

- Audio and Video

Case studies related to improving health care.

first < > last

- An Extended Stay A 64-year-old man with a number of health issues comes to the hospital because he is having trouble breathing. The care team helps resolve the issue, but forgets a standard treatment that causes unnecessary harm to the patient. A subsequent medication error makes the situation worse, leading a stay that is much longer than anticipated.

- Mutiny The behavior of a superior starts to put your patients at risk. What would you do? The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the final installment in a series of case studies for the IHI Open School.

- On Being Transparent You are the CEO and a patient in your hospital dies from a medication error. What do you do next? The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the fourth in a series of case studies.

- Locked In A cancer diagnosis leads to tears and heartache. But is it correct? Dr. Paul Griner, Professor Emeritus of Medicine at the University of Rochester, presents the third in a series of case studies for the IHI Open School.

- Confidentiality and Air Force One A difficult patient. A difficult decision. The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the second in a series of case studies.

- The Protective Parent During a 50-year career in medicine, Dr. Paul Griner accumulated hundreds of patient stories. Most of his stories – including this case study "The Protective Parent" - are from the 1950s and 1960s, prior to what we now refer to as “modern medicine.”

- Advanced Case Study Between Sept. 30th and Oct. 14th, 2010, students and residents all over the world gathered in interprofessional teams and analyzed a complex incident that resulted in patient harm. Selected teams presented their work to IHI faculty during a series of live webinars in October.

- A Downward Spiral: A Case Study in Homelessness Thirty-six-year-old John may not fit the stereotype of a homeless person. Not long ago, he was living what many would consider a healthy life with his family. But when he lost his job, he found himself in a downward spiral, and his situation dramatically changed. John’s story is a fictional composite of real patients treated by Health Care for the Homeless. It illustrates the challenges homeless people face in accessing health care and the characteristics of high-quality care that can improve their lives.

- What Happened to Alex? Alex James was a runner, like his dad. One day, he collapsed during a run and was hospitalized for five days. He went through lots of tests, but was given a clean bill of health. Then, a month later, he collapsed again, fell into a deep coma, and died. His father wanted to know — what had gone wrong? Dr. John James, a retired toxicologist at NASA, tells the story of how he uncovered the cause of his son’s death and became a patient safety advocate.

- Improving Care in Rural Rwanda When Dr. Patrick Lee and his teammates began their quality improvement work in Kirehe, Rwanda, last year, the staff at the local hospital was taking vital signs properly less than half the time. Today, the staff does that task properly 95% of the time. Substantial resource and infrastructure inputs, combined with dedicated Rwandan partners and simple quality improvement tools, have dramatically improved staff morale and the quality of care in Kirehe.

A quality improvement evaluation case study: impact on public health outcomes and agency culture

Affiliation.

- 1 Center for Health Equity & Quality Research, University of Florida College of Medicine-Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32209, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 23597806

- DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.011

Background: Quality improvement (QI) is increasingly recognized as an important strategy to improve healthcare services and health outcomes, including reducing health disparities. However, there is a paucity of evidence documenting the value of QI to public health agencies and services.

Purpose: The purpose of this project was to support and assess the impact on the outcomes and organizational culture of a QI project to increase immunization rates among children aged 2 years (4:3:1:3:3:1 series) within a large public health agency with a major pediatric health mission.

Methods: The intervention consisted of the use of a model-for-improvement approach to QI for the delivery of immunization services in public health clinics, utilizing plan-do-study-act cycles and multiple QI techniques. A mixed-method (qualitative and quantitative) model of evaluation was used to collect and analyze data from June 2009 to July 2011 to support both summative and developmental evaluation. The Florida Immunization Registry (Florida SHOTS [State Health Online Tracking System]) was used to monitor and analyze changes in immunization rates from January 2009 to July 2012. An interrupted time-series application of covariance was used to assess significance of the change in immunization rates, and paired comparison using parametric and nonparametric statistics were used to assess significance of pre- and post-QI culture items.

Results: Up-to-date immunization rates increased from 75% to more than 90% for individual primary care clinics and the overall county health department. In addition, QI stakeholder scores on ten key items related to organizational culture increased from pre- to post-QI intervention. Statistical analysis confirmed significance of the changes.

Conclusions: The application of QI combined with a summative and developmental evaluation supported refinement of the QI approach and documented the potential for QI to improve population health outcomes and improve public health agency culture.

Copyright © 2013 American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Child, Preschool

- Immunization / statistics & numerical data*

- Organizational Case Studies

- Organizational Culture

- Outcome Assessment, Health Care*

- Public Health

- Quality Improvement*

Patient Safety and Quality Improvement in Healthcare

A Case-Based Approach

- © 2021

- Rahul K. Shah 0 ,

- Sandip A. Godambe 1

Children’s National Health System, Washington, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Children's Hospital of The King's Daughters, Norfolk, USA

- Provides case-based approaches with tangible examples

- Includes diagrams and images to enhance learning

- Includes key learning points within each chapter

- Provides a question and answer section at the conclusion of each chapter

36k Accesses

6 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (22 chapters)

Front matter, introduction: a case-based approach to quality improvement.

- Sandip A. Godambe, Rahul K. Shah

Organizational Safety Culture: The Foundation for Safety and Quality Improvement

- Michael F. Gutzeit, Holly O’Brien, Jackie E. Valentine

Creation of Quality Management Systems: Frameworks for Performance Excellence

- Adam M. Campbell, Donald E. Lighter, Brigitta U. Mueller

Reliability, Resilience, and Developing a Problem-Solving Culture

- David P. Johnson, Heather S. McLean

Building an Engaging Toyota Production System Culture to Drive Winning Performance for Our Patients, Caregivers, Hospitals, and Communities

- Jamie P. Bonini, Sandip A. Godambe, Christopher D. Mangum, John Heer, Susan Black, Denise Ranada et al.

What to Do When an Event Happens: Building Trust in Every Step

- Michaeleen Green, Lee E. Budin

Communication with Disclosure and Its Importance in Safety

- Kristin Cummins, Katherine A. Feley, Michele Saysana, Brian Wagers

Using Data to Drive Change

- Lisa L. Schroeder

Quality Methodology

- Michael T. Bigham, Michael W. Bird, Jodi L. Simon

Designing Improvement Teams for Success

- Nicole M. Leone, Anupama Subramony

Handoffs: Reducing Harm Through High Reliability and Inter-Professional Communication

- Kheyandra D. Lewis, Stacy McConkey, Shilpa J. Patel

Safety II: A Novel Approach to Reducing Harm

- Thomas Bartman, Jenna Merandi, Tensing Maa, Tara C. Cosgrove, Richard J. Brilli

Bundles and Checklists

- Gary Frank, Rustin B. Morse, Proshad Efune, Nikhil K. Chanani, Cindy Darnell Bowens, Joshua Wolovits

Pathways and Guidelines: An Approach to Operationalizing Patient Safety and Quality Improvement

- Andrew R. Buchert, Gabriella A. Butler

Accountable Justifications and Peer Comparisons as Behavioral Economic Nudges to Improve Clinical Practice

- Jack Stevens

Diagnostic Errors and Their Associated Cognitive Biases

- Jennifer E. Melvin, Michael F. Perry, Richard E. McClead Jr.

An Improvement Operating System: A Case for a Digital Infrastructure for Continuous Improvement

- Daniel Baily, Kapil Raj Nair

Patient Flow in Healthcare: A Key to Quality

- Karen Murrell

It Takes Teamwork: Consideration of Difficult Hospital-Acquired Conditions

- J. Wesley Diddle, Christine M. Riley, Darren Klugman

- Emergency Preparedness

- Workforce and Patient Experience

- Performance Excellence

- Incident Reporting

- Hand Hygiene and Stethoscope Hygiene

- Clinical Effectiveness

- STEEP Principles

About this book

Editors and affiliations.

Rahul K. Shah

Children's Hospital of The King's Daughters, Norfolk, USA

Sandip A. Godambe

About the editors

Bibliographic information.

Book Title : Patient Safety and Quality Improvement in Healthcare

Book Subtitle : A Case-Based Approach

Editors : Rahul K. Shah, Sandip A. Godambe

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55829-1

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Medicine , Medicine (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-55828-4 Published: 16 December 2020

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-55831-4 Published: 17 December 2021

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-55829-1 Published: 15 December 2020

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIX, 383

Number of Illustrations : 11 b/w illustrations, 118 illustrations in colour

Topics : Practice and Hospital Management , General Practice / Family Medicine , Primary Care Medicine

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Call for Papers

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 7, Issue 2

- Continuous quality improvement methodology: a case study on multidisciplinary collaboration to improve chlamydia screening

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Allison Ursu 1 ,

- Grant Greenberg 2 and

- Michael McKee 3

- 1 Department of Family Medicine , University of Michigan Medical School , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- 2 Department of Family Medicine , Lehigh Valley Health Network , Allentown , Pennsylvania , USA

- 3 Family Medicine , University of Michigan Medical School , Ann Arbor , MI , United States

- Correspondence to Dr Allison Ursu; awessel{at}med.umich.edu

This article illustrates quality improvement (QI) methodology using an example intended to improve chlamydia screening in women. QI projects in healthcare provide great opportunities to improve patient quality and safety in a real-world healthcare setting, yet many academic centres lack training programmes on how to conduct QI projects. The choice of chlamydia screening was based on the significant health burden chlamydia poses despite simple ways to screen and treat. At the University of Michigan, we implemented a multidepartment process to improve the chlamydia screening rates using the plan-do-check-act model. Steps to guide QI projects include the following: (1) assemble a motivated team of stakeholders and leaders; (2) identify the problem that is considered a high priority; (3) prepare for the project including support and resources; (4) set a goal and ways to evaluate outcomes; (5) identify the root cause(s) of the problem and prioritise based on impact and effort to address; (6) develop a countermeasure that addresses the selected root cause effectively; (7) pilot a small-scale project to assess for possible modifications; (8) large-scale roll-out including education on how to implement the project; and (9) assess and modify the process with a feedback mechanism. Using this nine-step process, chlamydia screening rates increased from 29% to 60%. QI projects differ from most clinical research projects by allowing clinicians to directly improve patients’ health while contributing to the medical science body. This may interest clinicians wishing to conduct relevant research that can be disseminated through academic channels.

- chlamydia screening

- quality improvement

- healthcare delivery

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0

https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000085

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Healthcare organisations continually strive to improve patient care services and quality through initiatives driven by their leadership and healthcare payers (eg, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 1 Quality improvement (QI) projects in healthcare provide opportunities to advance best practices and enhance the redesign of healthcare to improve patient quality and safety. 2 3

The modern study of QI has its origins in industry dating back to the first automotive assembly lines designed by Henry Ford in the early 1900s. Subsequently, work by Edwards Deming led to what is now commonly referred to as the ‘Plan/Do/Check/Adjust’ (PDCA) cycle. 4 Concurrent to the development of PDCA, Juran 5 developed what would become known as ‘total quality management’, which led to further developments in quality management methodology and philosophy such as Lean and Six Sigma. The same principles that apply to industry are now commonly applied to healthcare models of improvement. Unlike most research projects, QI tends to lack a true ‘control’ arm, but QI still lends itself to rigorous academic reporting. To facilitate this, the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines were developed to provide a standard structure for reporting and publishing QI. 6

Despite the growth in knowledge around QI, and the development of QI as an academic discipline, many clinicians lack the training, skills and access to resources to conduct QI. QI projects require a blend of social science, engineering and research methodology skills. Academic healthcare institutions now recognise this need, and many offer training to their medical students, residents, faculty and staff. 7–9 Unlike many clinical research projects, QI projects are often smaller scale and occur on a compressed time frame.

While there are several tools to facilitate a QI project, here we focus on the standard PDCA methodology as defined by Deming. In our example, we engaged clinicians to participate by also coupling the project with the opportunity to obtain continuing medical educational credits. By aligning the QI need with the ability to meet board recertification requirements, active participation in the QI project is directly rewarded, and facilitates broader perspectives and more robust solutions.

The PDCA model follows a four-step cycle to achieve continuous improvement. 10 This method is also applicable to new projects or processes, products, or services. When followed, PDCA facilitates more robust project planning, root cause analysis, data collection and review, and ability to maintain focus. ‘Plan’ signifies developing an understanding of the possible countermeasure leading to an improvement. ‘Do’ is implementing the countermeasure. ‘Check’ is analysing the data that inform the effectiveness of the countermeasure on the topic of improvement. ‘Adjust’ is applying the learning from the data analysis and either developing refinements to the original countermeasure or developing a new countermeasure.

Incorporating a tool such as ‘The Model for Improvement’ can help QI teams focus on what they are seeking to achieve. The Model for Improvement has three key questions:

What are we trying to accomplish?

How will we know if a change is an improvement?

What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

Chlamydia screening QI project for illustrating the features of a QI project

There were 1.5 million chlamydia infections reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2015, with nearly 80% of these being reported from outside of sexually transmitted diseases clinics. 11 Adolescents and young adults between the ages of 16 and 24 account for half of these infections; they also have the highest burden of the disease in the USA, four times higher than the general public. Rates of infection have continued to increase since 2013. In 2017, the rate for women is approximately 687 per 100 000. 12 The estimated annual cost of chlamydia infection in the USA is estimated to be between $250 and $770 million. 13

Multiple national physician and public health groups recommend chlamydia screening for sexually active women younger than 25 years old in order to reduce the rates of infection and sequelae of the disease. These sequelae include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), chronic pelvic pain, tubo-ovarian abscesses and infertility. There is also evidence that chlamydia infection facilitates the transmission of HIV. 14 Randomised control trials have shown that screening for chlamydia can reduce PID rates. 15 However, screening rates remain low.

The objective of this paper is to provide readers an overview on what resources and training programmes are recommended to support these QI endeavours. The following section provides a step-by-step process on how a specific QI project was designed and implemented to address poor chlamydia screening and treatment for young women at a large healthcare institution. Improvement in screening for chlamydia was chosen as a QI effort as this infection is the most commonly reported sexually transmitted disease in the USA, occurring at a rate of over 3265.7 cases per 100 000 in women aged 15–19, and 3985.8 cases per 100 000 in women aged 20–24. 16 Untreated chlamydia infection can lead to complications such as PID, infertility and tubal pregnancy.

We used PDCA and the Model for Improvement steps to implement QI to improve chlamydia screening in women aged 16–24, and use this project as an exemplar to illustrate the steps of QI. We chose a focus on chlamydia screening due to the health burden that the infection poses, the availability of non-invasive screening tests, success of treatment and our institution’s low rates of screening which needed improvement. The chlamydia screening QI project was a multidepartment collaboration (ie, family medicine, internal medicine, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, and the University Health Service) of the University of Michigan Health System, an academic institution located in Midwestern USA. Representatives from each department worked together to produce a standard approach to develop the workflow, educational materials and a clinical decision support tool that was integrated into the electronic health record (EHR). To gain skills in QI, several members (GG and so on) of our team gained training in Lean healthcare, epidemiology and process change. For data collection we used outputs from our EHR, conducted interviews of clinicians and staff to understand the current state and challenges in chlamydia screening, and conducted clinical observations in the involved specialties. We assessed progress continually, with quarterly reporting to local clinical teams. The focus of this report is a 1-year period from 21 May 2014 to 31 May 2015.

Here we illustrate nine essential steps for conducting a QI project.

Step 1. Assemble the team of stakeholders

The first step for implementing a QI project is to assemble a team of stakeholders and strong leaders ( figure 1 ). Effective teams are diverse, interdisciplinary and share a common goal. It is critically important to have buy-in from leadership to ensure that adequate resources and time are allocated towards the proposed QI project.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Quality improvement step-by-step chart.

In our example we engaged all primary care-based departments caring for women aged 16–24 in an outpatient setting. This allowed us to standardise screening. A team was organised by a physician leader who had Lean training as well as a master’s degree in health system administration. The team included a project manager as well as other primary care stakeholders. Selection for local project leaders focused on recruiting individuals who were respected, visible and trusted within their own departments.

Step 2. Define the problem

Through a consensus decision-making process, prioritise the highest yield countermeasures which make the largest impact with the least effort ( figure 2 ). Methods for identifying a problem can come from chart review and clinical audit. In many places this can be facilitated through the use of EHR. Reports can be run that identify areas for improvement, for example patients needing cervical cancer screening, and these can be broken down by department, clinic and even provider. Epidemiological data can also identify problems. These could come from insurers or public health groups, for example, the Department of Public Health tracking chlamydia rates. Looking to the ‘Model for Improvement’, this step should partly answer the question of ‘What are we trying to achieve?’

Plan-do-check-adjust graph.

When we began the project, the study practices were screening 29% of eligible patients according to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). The eligible patients were women aged 16–24 who were deemed sexually active by a HEDIS algorithm. Our problem was defined as underperforming on chlamydia screening for women aged 16–24 years old.

Step 3. Identify stakeholders to build support for the project and assess level of interest

The next step is to prepare for the project ( figure 2 ). Research examples of similar projects and look for resources such as clinical guidelines to assist in developing your solution. The team needs to decide on a budget and timeline, determine if relevant data are already being collected, and establish what are the baseline data.

Our team began by identifying and recruiting clinician leaders from each of the stakeholder departments. From here we coordinated the work both with the operational leadership and clinical leadership of the local clinics as they would be responsible for insuring the process was in place and functioning. We also paired this QI project with the Part IV Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credit through the American Board of Medical Specialties Multi-Specialty Portfolio Program (MSPP). 17 An MOC project through MSPP provides physicians required credit towards maintaining board certification by conducting a QI project using the PDCA methodology. Additionally, we identified a toolkit for improving chlamydia screening. 18 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has several examples on their website. 19

Step 4. Determine a goal and decide how to assess progress towards the goal and achievement of success

This involves deciding on a goal that is concrete, measurable, achievable and clinically important. This should be a discussion among the stakeholders, as what is important or achievable for one group may be different for another. Decide how to measure progress towards the goal, for example having monthly reports on screening rates that are reviewed by the stakeholders. This step fits into the ‘Model for Improvement’ under the first two questions noted in the Introduction section.

Our goal was to screen 57% (HEDIS 95th percentile) of eligible patients. Our measure of interest was the proportion of female patients aged 16–24 who had a chlamydia screen in the last 12 months. We planned to evaluate the project during an initial pilot period and once it was rolled out to all clinics, using the PDCA methodology. We agreed to meet monthly to review department-level data to allow for any further adjustments as needed. One example of an adjustment was changing the workflow to have a urine sample collected for any eligible patient prior to the visit. A model such as the above helped the team stay focused even in chaotic and demanding healthcare environments in which schedules and resources changed from day to day.

Step 5. Identify barriers

This can be done through brainstorming with stakeholders, surveying staff and through a root cause analysis ( figure 2 ). Physicians and non-physicians tend to jump to solutions instead of doing a root cause analysis. Root cause analysis is important to do so that the solution is sustainable. Root causes are underlying, can be controlled and managed. 20 They explain the what, why and how something occurs. The analysis involves data collection, recommendations and implementation very similar to the PDCA cycle. This process is slow and must be deliberate in order to create a new normal and ensure sustainability. This step addresses the ‘Model for Improvement’s’ last question.

In our case simply telling physicians to increase chlamydia screening will not work. The entire process must be changed. Some of the barriers we were able to identify were lack of knowledge of the screening recommendation, lack of knowledge of a non-invasive urine test for screening (no requirement for a pelvic exam), fear of breaking confidentiality for minors, not understanding the process of insurance coverage and insurances’ explanation of benefits to the parents of minors, discomfort discussing sexually transmitted infections during a clinic visit, lack of time in the visit to address sensitive issues, and a lack of a standardised approach to screening.

Step 6. Develop a countermeasure

As with defining the problem, a consensus among the team is crucial for success of the solution. This step is made easier when the problem and barriers have been clearly defined. The potential solution(s) must address the underlying causes of the problem. Solutions will also be more robust with input from the whole team. For example, if the front desk staff is responsible for giving patients information on screening, then input on how this is done best comes from them. There likely will be multiple solutions and they may vary by stakeholder.

We developed a standard approach for workflow, educational materials and a clinical decision support tool within the EHR to overcome our obstacles to screening. While not required for all QIs, a workflow was essential to our project. 21 The workflow streamlines discussion of screening, collection of screening sample, ordering test, follow-up of results and treatment. Because the workflow is standardised and easily visualised in the included flow sheet, it can be readily adapted to other clinical sites. The newly developed educational materials for staff, patients and parents explained the importance of screening, as well as the process for screening, and notification of results and treatment. These materials are also easily transferable to other sites. Lastly, the clinical decision support tool was an alert that is displayed in an area of the EHR called ‘best practice advisories’ (BPA). This notification is visible whenever the chart of an eligible patient is accessed. The automated alerts can easily be transferred to any healthcare system using an Epic EHR system ( figure 3 ).

Example of Chlamydia screening workflow. BPA, best practice advisories; MA, medical assistant; RN, registered nurseof M, University of Michigan.

Step 7. Test the process in a limited setting

Assessing the results and modifying the process on a small scale helps inform how the project is working ( figure 2 ). Typically, this involves conducting a pilot project. This is like a mini-PDCA cycle within the larger PDCA cycle of your QI project. This is where to test your initial problem, barriers, solutions and data collection, identify new barriers and solutions, and refine your process.

We carried out a pilot in three of our clinics: one family medicine, one paediatric and one internal medicine. These departments had representatives on the chlamydia QI team which facilitated the introduction and monitoring of the project. After 8 months the pilot clinics improved their chlamydia screening to 60% of eligible patients. During this time, feedback from the three clinics was used to adjust the process. For example, in paediatrics they felt that the discussion around chlamydia testing was too burdensome for all office visits given their high percentage of minor patients. They elected to use the workflow for chlamydia screening, and have the EHR alert, only during well-child exams rather than at all visits.

Step 8. Large scale project rollout

As illustrated in figure 1 , evaluating and modifying the project is a critical process more than a single step ( figure 2 ). This involves review of the data by the project team and by those who are doing the work, that is, medical assistants, office managers, physicians and nurses. All participants should be encouraged to provide feedback on the process, new barriers and new solutions. This can be done by surveying or interviewing the staff and by reviewing internal policies. 22–24

Following modifications informed by our pilot, we launched the project by activating the BPA and providing educational materials in all primary care clinics. This included presentations to educate the clinical providers and staff on the importance and need for process change to improve our low chlamydia screening rates. These occurred in the participating departments in large and small settings, for example at Grand Rounds as well as at medical assistant meetings for individual clinics.

Step 9. Evaluate and modify the QI project

As illustrated in figure 1, evaluating and modifying the project is a critical process more than a single step ( figure 2 ). This involves review of the data by the project team and by those who are doing the work, that is, medical assistants, office managers, physicians and nurses. All participants should be encouraged to provide feedback on the process, new barriers and new solutions. This can be done by surveying or interviewing the staff and by reviewing internal policies. 22–24

We met monthly to discuss the results from each of the participating departments. Shortly after a standard workflow and BPA had been implemented, the screening rate for women between 16 and 24 years old improved to 66% of eligible patients in family medicine clinics. We noticed an immediate improvement as soon as the process went live, and hypothesised the build-up and discussion of the project led to improvement before the process actually changed.

Additional barriers across departments identified were lack of adoption of the standard workflow among check-in staff, medical assistants and physicians. Our intervention to address this barrier was to standardise medical assistant workflow from intake to utilisation of the BPA particularly when the patient is 16–17 years old. A new standard workflow was agreed on and disseminated to each clinic. Two months after this intervention, our screening rates for 16–17 years old improved from 42% to 48%. Significantly, 4 years after our intervention, we have been able to maintain the rates of chlamydia screening well above our initial rate of 29%.

QI projects benefit from the step-by-step process outlined in the PDCA and Model for Improvement theories to effectively tackle potential challenges and improve the overall project’s relevance and success. The scale of the QI project can vary from a single clinical site to a large multispecialty group as the above example used. For example, Wakai et al 25 conducted a QI project in a single site but included an intervention. Focused on improvement of periodic assessments, they identified and addressed barriers and threats to the project’s success. QI projects can benefit from a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative analyses to better determine the next steps to the QI process. 22

Regardless of the model or the design used by the QI project, effective communication with all involved parties is key to successful QI projects. In hindsight, our project might have been more effective if we had communicated with our Department of Public Health about our change in approach to chlamydia screening. For example, in 2015, chlamydia incidence reached a record high prompting the Department of Public Health to declare an epidemic. The rate of positive screening tests was tracked by our microbiology lab and remained between 3.3% and 3.6%, although the number of tests increased by nearly 10 000 in 2015 compared with 2014, the year of our intervention. The increased positive tests were likely related to our increased screening efforts rather than a true outbreak.

Four years after intervening, the rates for chlamydia screening in our clinics ranged between 49% and 80% for 18–24 years old but 32%–63% for 16–17 years old. This is remarkable as achieving screening rates above 55% is difficult even in a research setting. 26 Despite the success in increasing screening rates for chlamydia, certain groups (ie, younger aged females) were still low. This highlights that QI projects may necessitate additional QI projects to address areas of concern that were discovered. For example, it was quickly noted that screening rates for 16–17 years old remained lower than for 18–24 years old. These data were not initially separated prior to our QI project or at the start of our intervention, limiting the ability to fully address this issue. We did however identify unique barriers mainly with the paediatric department that required modifications from the standard workflow that was working effectively for the chlamydia screening programme in other departments. The younger women, aged 16–17 years old, have special considerations for confidentiality, privacy and explanation of benefits forms designed to prevent accidental parent disclosures. In light of these findings, we plan to complete another MSPP MOC project for chlamydia screening to fully address these issues.

QI projects, including the one described above, have the ability to change healthcare delivery systems. Our QI project demonstrated the importance of chlamydia screening to the clinicians, and provided a feasible way to deliver care effectively to women aged 16–24 when coming for medical appointments. The use of a well-integrated BPA decreased clinicians’ mental demands by simply reminding and offering them of an evidence-based screening recommendation that could be selected with a single click.

There are several challenges and limitations to conducting QI projects. These projects require special skills that many clinicians lack. Furthermore, QI projects, similar to other research projects, need time, resources and commitment from multiple involved parties to successfully complete. The development and the design of QI projects should be carefully thought out, including how the project will be implemented, assessed, if needed, modified and communicated to others. QI projects, if not carefully designed, can be doomed by insufficient training or participation of all involved parties, poor fit with existing structural clinical flow or a perceived low priority of the project (eg, not a relevant or significant clinical issue). Also, if publication is a possibility, institutional review board approval should be requested.

Other resources

The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Conference of Practice Improvement is provided annually and features practical skills and resources for practice change. The STFM also has a rich online resource catalogue of courses, presentations and handouts on QI. Some academic institutions cover courses in business, public health and/or engineering schools. Furthermore, international organisations such as the World Organisation of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians 27 are committed to the improvement of patients’ quality of life and have offered QI workshops in the past. 28

Conclusions

Incorporating QI training programmes is a good investment for healthcare organisations and academic centres since they generate useful projects that will likely positively impact the overall healthcare system and improve dissemination of helpful and high-quality clinical strategies. The QI approach presented here can be applied to a myriad of clinical scenarios. Potential areas for improvement include any disease with a screening recommendation, for example lung cancer screening with low-dose CT scan. This project could also work for situations other than screening, such as triage of patient phone calls to clinic, or increasing uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine. While QI projects require commitment and resources, as demonstrated here, these projects have the potential for primary care physicians to improve the health of the entire populations.

- Strategy CQ

- Hurtado MP SE ,

- Corrigan JM

- Juran JM GA

- Goodman D , et al

- Education QT

- Exchange AHCI

- Leaders APSfC

- Prevention CfDCa

- Incidence P and Cost of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States

- Fleming DT ,

- Wasserheit JN

- Gottlieb SL ,

- Chlamydia Statistics

- Program STatAM-SP

- Administration USDoHaHSHRaS

- Rooney JJ ,

- Bravata DM ,

- Sundaram V ,

- Lewis R , et al

- Creswell JC HM

- DeJonckheere M VL

- Engelman A ,

- Meeks LM MDF

- Simasek M ,

- Nakagawa U , et al

- Reid M , et al

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval This study was deemed not regulated by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

QOF quality improvement case studies

Three case studies developed by the Royal College of General Practitioners, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Health Foundation which provide examples of how practices could approach their quality improvement activity.

QOF 2020/21 quality improvement cases studies

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- 10 Essential Public Health Services

- Cooperative Agreements, Grants & Partnerships

- Public Health Professional: Programs

- Health Assessment: Index

- Research Summary

- COVID-19 Health Disparities Grant Success Stories Resources

- Communication Resources

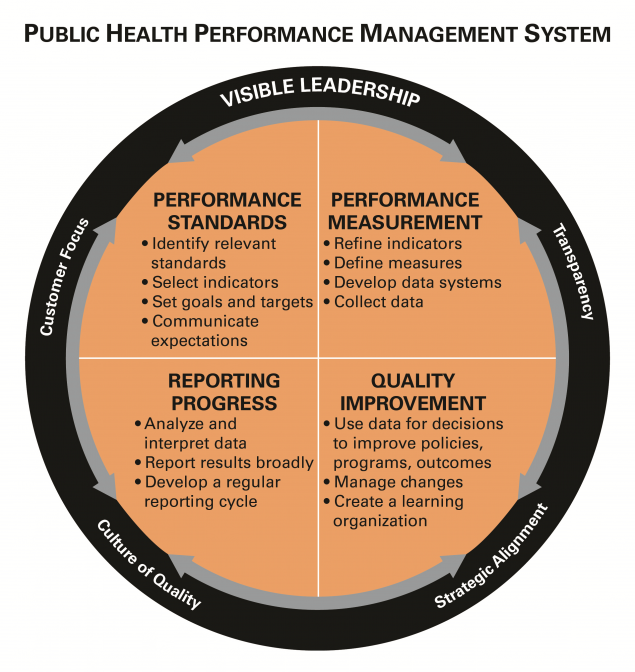

Performance Management and Quality Improvement: Definitions and Concepts

At a glance.

In the public health field, many initiatives and organizations focus on improving public health practice, using different terms. This page provides common definitions for public health performance management.

Definitions and concepts

There has been a rapidly growing interest in performance and quality improvement within the public health community, and different names and labels are often used to describe similar concepts or activities. Other sectors, such as industry and hospitals, have embraced a diverse and evolving set of terms but which generally have the same principles at heart (i.e., continuous quality improvement, quality improvement, performance improvement, six sigma, and total quality management).

In the public health field, an array of initiatives has set the stage for attention to improving public health practice, using assorted terms. The Turning Point Collaborative focused on performance management, the National Public Health Performance Standards Program created a framework to assess and improve public health systems, while the US Department of Health and Human Services has provided recommendations on how to achieve quality in healthcare . In 2011, the Public Health Accreditation Board launched a national voluntary accreditation program that catalyzes quality improvement but also acknowledges the importance of performance management within public health agencies. Regardless of the terminology, a common thread has emerged—one that focuses on continuous improvement and operational excellence within public health programs, agencies, and the public health system.

To anchor common thinking, below are links to some of the definitions that are frequently used throughout these pages.

Key definitions

- Riley et al, "Defining Quality Improvement in Public Health", JPHMP, 2010, 16(10), 5-7.

- Public Health Accreditation Board Acronyms and Glossary of Terms, Version 2022 [PDF]

Public Health Gateway

CDC's National Center for State, Tribal, Local, and Territorial Public Health Infrastructure and Workforce helps drive public health forward and helps HDs deliver services to communities.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 13 September 2017

Domains associated with successful quality improvement in healthcare – a nationwide case study

- Aleidis Skard Brandrud 1 ,

- Bjørnar Nyen 2 ,

- Per Hjortdahl 3 ,

- Leiv Sandvik 4 ,

- Gro Sævil Helljesen Haldorsen 5 ,

- Maria Bergli 1 ,

- Eugene C. Nelson 6 &

- Michael Bretthauer 7

BMC Health Services Research volume 17 , Article number: 648 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

26 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is a distinct difference between what we know and what we do in healthcare: a gap that is impairing the quality of the care and increasing the costs. Quality improvement efforts have been made worldwide by learning collaboratives, based on recognized continual improvement theory with limited scientific evidence. The present study of 132 quality improvement projects in Norway explores the conditions for improvement from the perspectives of the frontline healthcare professionals, and evaluates the effectiveness of the continual improvement method.

An instrument with 25 questions was developed on prior focus group interviews with improvement project members who identified features that may promote or inhibit improvement. The questionnaire was sent to 189 improvement projects initiated by the Norwegian Medical Association, and responded by 70% (132) of the improvement teams. A sub study of their final reports by a validated instrument, made us able to identify the successful projects and compare their assessments with the assessments of the other projects. A factor analysis with Varimax rotation of the 25 questions identified five domains. A multivariate regression analysis was used to evaluate the association with successful quality improvements.

Two of the five domains were associated with success: Measurement and Guidance ( p = 0.011), and Professional environment ( p = 0.015). The organizational leadership domain was not associated with successful quality improvements ( p = 0.26).

Our findings suggest that quality improvement projects with good guidance and focus on measurement for improvement have increased likelihood of success. The variables in these two domains are aligned with improvement theory and confirm the effectiveness of the continual improvement method provided by the learning collaborative. High performing professional environments successfully engaged in patient-centered quality improvement if they had access to: (a) knowledge of best practice provided by professional subject matter experts, (b) knowledge of current practice provided by simple measurement methods, assisted by (c) improvement knowledge experts who provided useful guidance on measurement, and made the team able to organize the improvement efforts well in spite of the difficult resource situation (time and personnel). Our findings may be used by healthcare organizations to develop effective infrastructure to support improvement and to create the conditions for making quality and safety improvement a part of everyone’s job.

Peer Review reports

Healthcare is suffering from serious unsolved problems that are threatening lives, increasing costs, and making the care unpredictable to the patient [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Improvement of quality in health care, is probably one of the greatest challenges of modern healthcare leadership. Quality improvement strategies sometimes fail to focus the changes on clinical, patient oriented improvements, and to involve the frontline healthcare professionals at an early stage of the change process [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

The role of qualified improvement guidance has received little attention in the quality improvement literature [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. A recent analysis of 35 systematic reviews explored the influence of context on the effectiveness of different quality improvement strategies. Improvement guidance was not found among a broad range of associated contextual factors that contribute to successful improvement. The analysis organized the findings based on the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ) model [ 16 , 17 ]. The MUSIQ model itself was based on a systematic review that included continual improvement interventions, but did not cover the role of improvement knowledge guidance [ 14 , 17 ]. A cluster-randomized trial aimed to compare clinic-level coaching with other learning collaborative components, found coaching to be equally effective with interest circle calls (group telephone conferences) in achieving clinical outcome improvements, but coaching was more cost-effective [ 18 ]. Godfrey did also find positive effects of systematic clinic-level coaching [ 19 , 20 ].

In a case study of 182 improvement teams Strating found that creating measurable targets is a crucial task in quality improvement [ 21 ]. In a systematic review of quality measurement . Thor et al. found statistical process control (SPC), to be a useful method for those who mastered the technique [ 22 ]. This underscores the importance of good measurement guidance.

Many healthcare organizations do not have a basic infrastructure to support improvement, and contextual factors generally receive scant attention in the current literature on quality improvement strategies [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 22 , 23 ]. Kringos et al. found that the availability and functionality of information technology and facilitated data collection improved the effectiveness of quality improvement intervention, as well as the involvement of multidisciplinary improvement teams [ 16 ].

Little evidence is found that leadership support is associated with successful quality improvement [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. This may be typical for external initiated learning collaboratives, because we found a few studies where the frontline leaders have been directly included in the project planning and improvement guidance, with a positive leadership influence on the effectiveness of the improvement efforts [ 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Since 1994, and in spite of a limited underpinning of scientific evidence , the continual improvement method has been spread worldwide by thousands of improvement collaboratives [ 13 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Relatively little of that work is reported in the biomedical literature [ 30 ]. Systematic reviews and single studies of quality improvement efforts that are reported, indicate that a systematic and knowledge based approach is not enough to succeed without the presence of certain conditions for improvement, also described as context factors [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 31 ]. To meet these challenges, additional improvement approaches, including instruments for evaluating the underlying conditions for improvement, have been described [ 12 , 17 , 32 ]. In 2004 a systematic review recommended further research on factors that tend to produce adoptable changes in healthcare organizations [ 33 ]. A recent umbrella review of 35 systematic reviews of the influence of context factors on the effectiveness of (any) quality improvement intervention recommend further research to report the context factors in a systematic way to better appreciate their relative importance [ 16 ].