Kathang Pinoy

Filipino in thoughts and words.

Famous Essays and Speeches by Filipinos

- My Husband's Roommate

- Where is the Patis?

- I Am A Filipino

- This I Believe

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part I

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part II

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part III

- The Philippines A Century Hence by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire) Part IV

- The Indolence of the Filipinos by José Rizal (Translated by Charles E. Derbyshire)

- The Filipino Is Worth Dying For

- 1983 Arrival Speech of Ninoy Aquino

TAGALOG LANG

Learn Tagalog online!

Summary of the American Colonial Period

The rule of the United States over the Philippines had two phases.

The first phase was from 1898 to 1935, during which time Washington defined its colonial mission as one of tutelage and preparing the Philippines for eventual independence. Political organizations developed quickly, and the popularly elected Philippine Assembly (lower house) and the U.S.-appointed Philippine Commission (upper house) served as a bicameral legislature. The ilustrados formed the Federalista Party, but their statehood platform had limited appeal. In 1905 the party was renamed the National Progressive Party and took up a platform of independence. The Nacionalista Party was formed in 1907 and dominated Filipino politics until after World War II. Its leaders were not ilustrados . Despite their “immediate independence” platform, the party leaders participated in a collaborative leadership with the United States. A major development emerging in the post-World War I period was resistance to elite control of the land by tenant farmers, who were supported by the Socialist Party and the Communist Party of the Philippines. Tenant strikes and occasional violence occurred as the Great Depression wore on and cash-crop prices collapsed.

The second period of United States rule—from 1936 to 1946—was characterized by the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines and occupation by Japan during World War II. Legislation passed by the U.S. Congress in 1934 provided for a 10-year period of transition to independence. The country’s first constitution was framed in 1934 and overwhelmingly approved by plebiscite in 1935, and Manuel Quezon was elected president of the commonwealth. Quezon later died in exile in 1944 and was succeeded by Vice President Sergio Osmeña.

Japan attacked the Philippines on December 8, 1941, and occupied Manila on January 2, 1942. Tokyo set up an ostensibly independent republic, which was opposed by underground and guerrilla activity that eventually reached large-scale proportions. A major element of the resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the Huks (short for Hukbalahap, or People’s Anti-Japanese Army). Allied forces invaded the Philippines in October 1944, and the Japanese surrendered on September 2, 1945.

World War II was demoralizing for the Philippines, and the islands suffered from rampant inflation and shortages of food and other goods. Various trade and security issues with the United States also remained to be settled before Independence Day. The Allied leaders wanted to purge officials who collaborated with the Japanese during the war and to deny them the right to vote in the first postwar elections. Commonwealth President Osmeña, however, countered that each case should be tried on its own merits. The successful Liberal Party presidential candidate, Manuel Roxas , was among those collaborationists. Independence from the United States came on July 4, 1946, and Roxas was sworn in as the first president. The economy remained highly dependent on U.S. markets, and the United States also continued to maintain control of 23 military installations. A bilateral treaty was signed in March 1947 by which the United States continued to provide military aid, training, and matériel.

7 thoughts on “Summary of the American Colonial Period”

Can I have the basic elements of literary pieces under american period?

Who is manual roxas? Lol

Thanks for the correction!

Who is manual roxas ser?

Filipinos are brown.

i cant understand english

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Renee Karunungan

A History of the Philippines’ official languages

This was part of my essay for a class on Language Policy and Planning. The essay was marked with a distinction. I’m publishing a part of the essay for Buwan ng Wika.

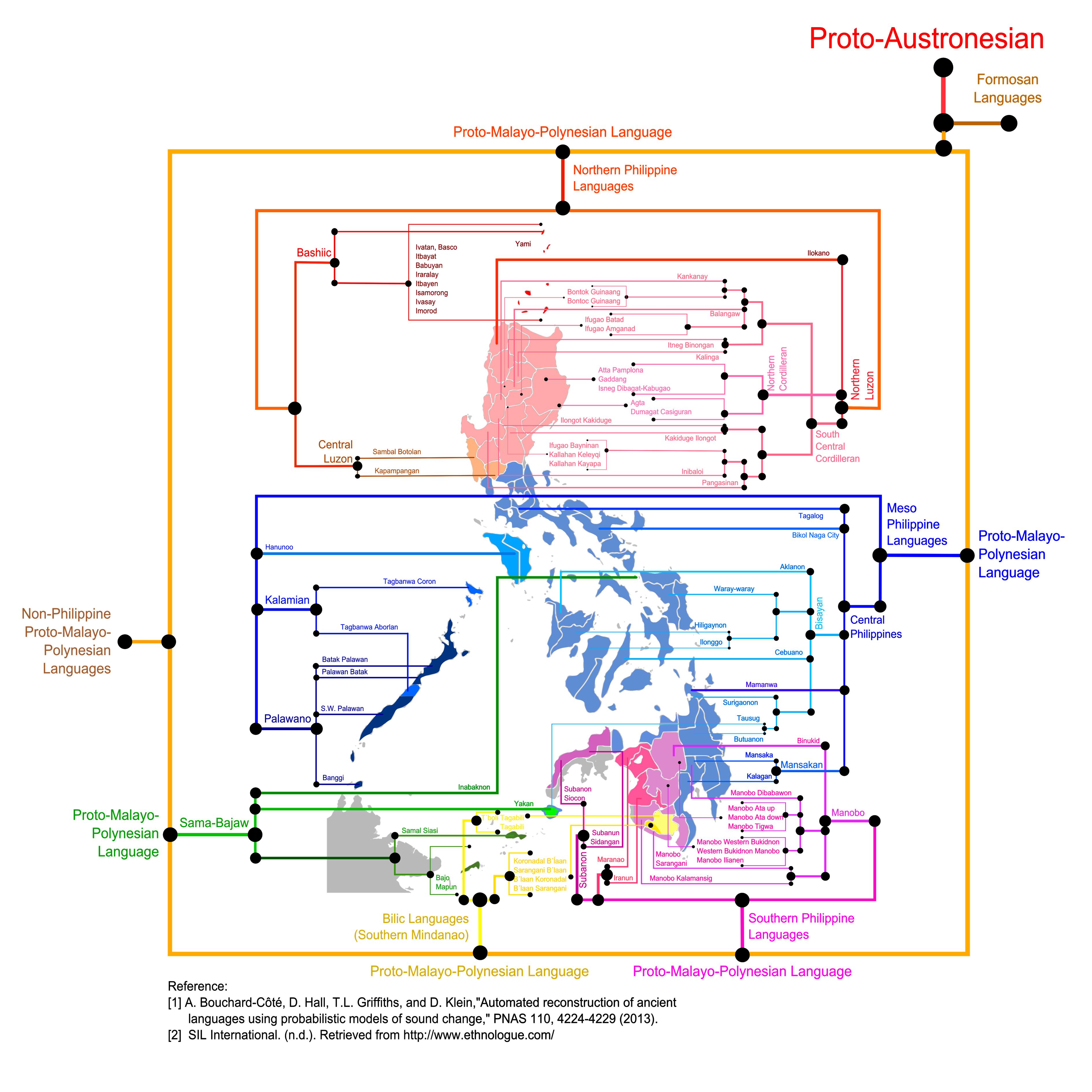

The Department of Education now has 17 designated languages that qualify for mother-language based education. The current Philippine constitution (1987) states that the national language is Filipino and as it evolves, “shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.” Further, the Philippine constitution (1987) has mandated the Government to “take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.”

However, this current policy on language has changed over the century, largely due to the Spanish, American, and Japanese colonisation, the liberation, and changes in the constitution post-dictatorship. There also remains to be contentions on whether Filipino, based on the Tagalog language, should be the national language of the Philippines. These contentions come from the non-Tagalog speaking region that have called the current language policy as “Tagalog imperialism.”

Given the rich history of the country and controversies regarding its language planning and policy throughout the century, this essay aims to explore the history of language policy and planning in the Philippines and the impacts it has had on its people, especially the non-Tagalog/Filipino speaking population. Secondary research and analysis will be used as a method of research.

History of LPP in the Philippines

The Philippines’ national language is Filipino. As mentioned earlier, de jure, it is a language that will be enriched from other languages in the Philippines. De facto , it is structurally based on Tagalog, the language of Manila and the CALABARZON (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Quezon) region (Gonzalez, 2006).

SPANISH COLONISATION

What was the language policy and planning like during the Spanish colonisation? According to Rodriguez (2013), the Spanish Crown issued several contradictory laws on language: missionaries were asked to learn the vernacular but were then required to teach Spanish. The friars continued to learn the local languages for evangelisation which turned out to be a success (Gonzalez, 2006). Thus, teaching Spanish teaching remained limited for the elites and wealthy Filipinos ready to conform to Spanish colonial agendas (Martin, 1999).

This was a way for the Spanish to control the country, and as Mahboob and Cruz (2013) suggest, a means to divide the rich and the poor. Arguably, this can also be the reason why the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) supported Philippine independence. Gonzalez (2006) writes,

In spite of repeated language instructions From the Crown on teaching the natives the Spanish language, there was only a little compliance. Instead the friars using common sense, kept employing the local languages, so much that in the period of intense nationalism in the nineteenth century, the failure of the Spanish friars to teach Spanish was used by some of the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) as a reason to accuse the friars of deliberately keeping Spanish away from the natives so as to prevent them from advancing themselves. Gonzales, 2006

AMERICAN COLONISATION

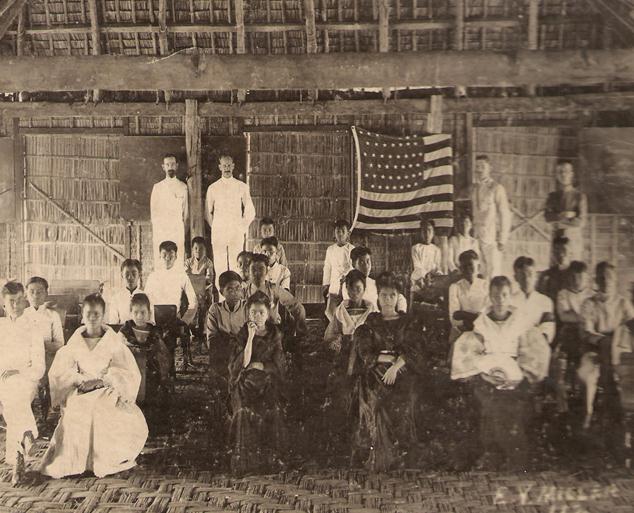

Shortly after the independence from Spain, the Philippines came under the American rule from 1898-1946. In the beginning Filipinos saw Americans as allies against Spain. The Americans saw the perfect opportunity for colonisation that Spain did not: education. While the Spanish eventually established schools through the Royal Decree of 1863, these were literacy schools teaching reading and writing in Spanish, religious studies, and numeracy not leading to any degrees (Gonzalez, 2006). Martin (1999) notes that the Americans, on the other hand, saw education as a powerful weapon and in the Philippines they found subjects receptive to the opportunities given by the English language. Gonzalez (1980, p.27-28) writes, “the positive attitude of Filipinos towards Americans; and the incentives given to Filipinos to learn English in terms of career opportunities, government service, and politics.”

American policy allowed for compulsory education for all Filipinos in English but was hostile to local languages. Although President McKinley ordered the use of English as well as mother tongue languages in education, the Americans found Philippine languages too many and too difficult to learn thus creating a monolingual system in English (Gonzalez, 2006). Manhit (1980) notes that during this time, students who used their mother tongue while in school premises were imposed with penalties. Media of instruction were in English, teachers were trained to teach English, and instructional materials were all in English. Local languages were used as “auxiliary languages to teach character education, good manners, and right conduct” (Martin, 1999, p.133). Ricento (2000 p. 198) argues that LPP during American colonisation led to a “stable digglosia” where English became the language of higher education, socioeconomic, and political opportunities still visible today.

Constantino (2002, p. 181) writes about how the acceptance of the English language eventually allowed Filipinos to embrace colonialism:

The first and perhaps the masterstroke in the plan to use education as an instrument of colonial policy was the decision to use English as the medium of instruction. English became the wedge that separate Filipinos from their past and later was to separate educated Filipinos from the masses of their countrymen… With American textbooks, Filipinos started learning not only a new language but also a new way of life, alien to their traditions and yet a caricature of their model. This was the beginning of their education. At the same time, it was the beginning of their miseducation, for they learned no longer as Filipinos but as colonials. Constantino, 2002

INDEPENDENCE

With the Commonwealth constitution being drafted, then Camarines Norte representative Wenceslao Vinzons proposed to include an article on the adoption of a national language. Article XIII section 3 of the 1935 Commonwealth Constitution directed the National Assembly to “take steps toward the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.” In 1936, the Institute of National Language (INL) was founded to study existing languages and select one of them as the basis of the national language. In 1937, the INL recommended Tagalog as the basis of the national language because it was found to be widely spoken and was accepted by Filipinos and it had a large literary tradition. By 1939, it was officially proclaimed and ordered to be disseminated in schools and by 1940 was taught as a subject in high schools across the country.

There was resistance to Tagalog , especially among speakers of Cebuano (Baumgartner, 1989). Baumgartner (1989, p.169) summarises the sentiments of other ethnic groups and asks, “With what right could the language of one ethnic group, even if that ethnic group lived in the national capital, be imposed on others?” Hau and Tinio (2003), however, point out that this opposition to Tagalog was not a manifestation of an ethnic conflict but rather reflects battles over resource allocations parceled out by regions. This has led for anti- Tagalog forces to ally themselves with the pro-English lobby (Lorente, 2013).

60’s and 70’s

The 60’s and the 70’s saw nationalist movements critical of the English language (Mahboob and Cruz, 2013). However, English remained a dominant language even at the peak of linguistic nationalism and height of student activism in the 70’s (Hau and Tinio, 2003). In 1974, a Bilingual Education Policy (BEP) was formally introduced, using English for Science and Mathematics and Filipino for all other subjects taught in school (Lorente, 2013). Gonzalez (1998) notes that this was a compromise to the demands of both nationalism and internationalism: English would ensure that Filipinos stay connected to the world while Filipino would help in the strengthening of the Filipino identity. This had little success, with English still dominant and Filipinos feared an “English deprived future.”

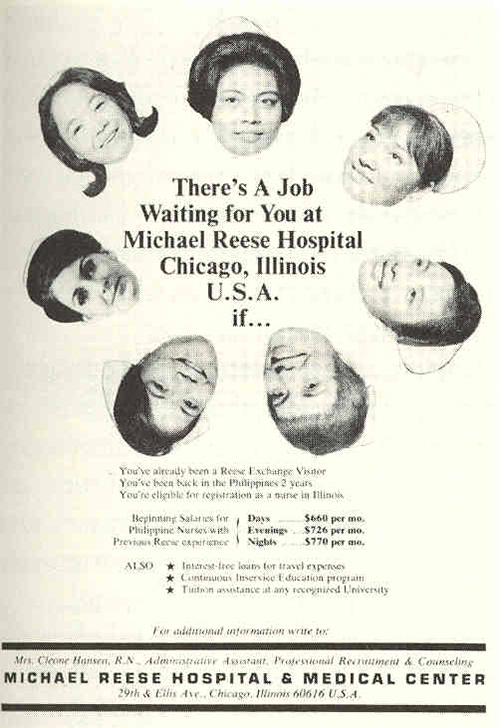

The year 1974 saw the start of the Philippines adhering to neoliberal policies, where the government started to promote cheap labour to other countries, advertising Filipinos’ ability to speak English. This was the year the first batch of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) was deployed to the Middle Least. An advertisement in The New York Times said: “We like multinationals … Local staff? Clerks with a college education start at $35 … accountants come for $67, executive secretaries for $148 … Our labor force speaks your language” (Lorente, 2013).

The 70’s, which was also the time of the dictatorship in the Philippines, saw changes in the education system, restructured to answer to export-oriented industrialisation (Lorente, 2013). With cheap export labour in mind, then President Ferdinand Marcos had a strong support for English and shifted English education to vocational and technical English training (Tollefson, 1991).

POST-DICTATORSHIP

After the dictatorship, the 1987 Constitution was written. Tagalog was changed to Pilipino and then Filipino for it to be less regionalistic, or less connected to the Tagalog region. According to this Constitution, Filipino was to be developed from all local languages of the Philippines.

According to this new BEP, Filipino and English shall be used as the medium of instruction while regional languages shall be used as auxiliary media of instruction and as initial language for literacy. Filipino was mandated to be the language of literacy and scholarly discourse while English, the “international language” of science and technology. However, nothing changed and implementation of the policy failed at most levels of education (Bernardo, 2004).

In 1991, the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (Commission on the Filipino Language) was established. They have led the celebration of Buwan ng Wika (National Language Month) every August. It is a regulating body whose job includes developing, preserving, and promoting the various local Philippine languages. The commission has published dictionaries, manuals, guides, and collection of literature in Filipino and other Philippine languages.

Both English and Filipino have dominated the education system in the Philippines. English is seen as the language of opportunities, and have been used by Filipinos to work abroad and find opportunities in the age of globalisation. Filipino , on the other hand, is seen as the language that can give identity to Filipinos, although not everyone agrees.

Will English and Filipino continue to dominate the country? With the current ideologies and policies put in place, it will. However, as other language speakers continue to fight for their identity and the right to be taught in their mother tongue, we might be able to see some changes, allowing for recognition of other languages in the country, and maybe even be given the same status as English and Filipino.

2 Replies to “A History of the Philippines’ official languages”

- Pingback: Is Filipino a growing language? - Inform Content Club

- Pingback: HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE IN THE PHILIPPINES – MY TEACHING KIT

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- The UP Charter

- University Seal

- University Administration

- UP Strategic Plan 2023-2029

- UP and the SDGs

- University Quality Policy

- Principles on Artificial Intelligence

- International Linkages

- Budget and Finances

- Academic Programs

- Constituent Universities

- Undergraduate Admissions | UPCAT

- Varsity Athletic Admission System

- Graduate Admissions

- Philosophy of Education

- Student Learning Assistance System

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Academics and Research

- Public Service

- Search for: Search Button

I am a Filipino

I am a Filipino is an essay written by Carlos Peña Romulo, Sr. which was printed in The Philippines Herald on August 16, 1941.

A Pulitzer Prize winner, passionate educator, intrepid journalist and effective diplomat, Romulo graduated from the University of the Philippines in 1918 with a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences degree. He earned his Master of Arts degree in Philosophy from Columbia University in 1921. He would join the ranks of the UP faculty in 1923 as an Associate Professor in what was then the English Department. He would be later be appointed to the Board of Regents in 1931. Almost three decades later, he would once again be reunited with the University, serving as its 11th President in 1962.

I am a Filipino–inheritor of a glorious past, hostage to the uncertain future. As such I must prove equal to a two-fold task–the task of meeting my responsibility to the past, and the task of performing my obligation to the future.

I sprung from a hardy race, child many generations removed of ancient Malayan pioneers. Across the centuries the memory comes rushing back to me: of brown-skinned men putting out to sea in ships that were as frail as their hearts were stout. Over the sea I see them come, borne upon the billowing wave and the whistling wind, carried upon the mighty swell of hope–hope in the free abundance of new land that was to be their home and their children’s forever.

This is the land they sought and found. Every inch of shore that their eyes first set upon, every hill and mountain that beckoned to them with a green-and-purple invitation, every mile of rolling plain that their view encompassed, every river and lake that promised a plentiful living and the fruitfulness of commerce, is a hallowed spot to me.

By the strength of their hearts and hands, by every right of law, human and divine, this land and all the appurtenances thereof–the black and fertile soil, the seas and lakes and rivers teeming with fish, the forests with their inexhaustible wealth in wild life and timber, the mountains with their bowels swollen with minerals–the whole of this rich and happy land has been, for centuries without number, the land of my fathers. This land I received in trust from them and in trust will pass it to my children, and so on until the world is no more.

I am a Filipino. In my blood runs the immortal seed of heroes–seed that flowered down the centuries in deeds of courage and defiance. In my veins yet pulses the same hot blood that sent Lapulapu to battle against the first invader of this land, that nerved Lakandula in the combat against the alien foe, that drove Diego Silang and Dagohoy into rebellion against the foreign oppressor.

That seed is immortal. It is the self-same seed that flowered in the heart of Jose Rizal that morning in Bagumbayan when a volley of shots put an end to all that was mortal of him and made his spirit deathless forever, the same that flowered in the hearts of Bonifacio in Balintawak, of Gregorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass, of Antonio Luna at Calumpit; that bloomed in flowers of frustration in the sad heart of Emilio Aguinaldo at Palanan, and yet burst forth royally again in the proud heart of Manuel L. Quezon when he stood at last on the threshold of ancient Malacañan Palace, in the symbolic act of possession and racial vindication.

The seed I bear within me is an immortal seed. It is the mark of my manhood, the symbol of dignity as a human being. Like the seeds that were once buried in the tomb of Tutankhamen many thousand years ago, it shall grow and flower and bear fruit again. It is the insignia of my race, and my generation is but a stage in the unending search of my people for freedom and happiness.

I am a Filipino, child of the marriage of the East and the West. The East, with its languor and mysticism, its passivity and endurance, was my mother, and my sire was the West that came thundering across the seas with the Cross and Sword and the Machine. I am of the East, an eager participant in its spirit, and in its struggles for liberation from the imperialist yoke. But I also know that the East must awake from its centuried sleep, shake off the lethargy that has bound his limbs, and start moving where destiny awaits.

For I, too, am of the West, and the vigorous peoples of the West have destroyed forever the peace and quiet that once were ours. I can no longer live, a being apart from those whose world now trembles to the roar of bomb and cannon-shot. I cannot say of a matter of universal life-and-death, of freedom and slavery for all mankind, that it concerns me not. For no man and no nation is an island, but a part of the main, there is no longer any East and West–only individuals and nations making those momentous choices which are the hinges upon which history resolves.

At the vanguard of progress in this part of the world I stand–a forlorn figure in the eyes of some, but not one defeated and lost. For, through the thick, interlacing branches of habit and custom above me, I have seen the light of the sun, and I know that it is good. I have seen the light of justice and equality and freedom, my heart has been lifted by the vision of democracy, and I shall not rest until my land and my people shall have been blessed by these, beyond the power of any man or nation to subvert or destroy.

I am a Filipino, and this is my inheritance. What pledge shall I give that I may prove worthy of my inheritance? I shall give the pledge that has come ringing down the corridors of the centuries, and it shall be compounded of the joyous cries of my Malayan forebears when first they saw the contours of this land loom before their eyes, of the battle cries that have resounded in every field of combat from Mactan to Tirad Pass, of the voices of my people when they sing:

Land of the morning, Child of the sun returning– Ne’er shall invaders Trample thy sacred shore.

Out of the lush green of these seven thousand isles, out of the heartstrings of sixteen million people all vibrating to one song, I shall weave the mighty fabric of my pledge. Out of the songs of the farmers at sunrise when they go to labor in the fields, out of the sweat of the hard-bitten pioneers in Mal-lig and Koronadal, out of the silent endurance of stevedores at the piers and the ominous grumbling of peasants in Pampanga, out of the first cries of babies newly born and the lullabies that mothers sing, out of the crashing of gears and the whine of turbines in the factories, out of the crunch of plough-shares upturning the earth, out of the limitless patience of teachers in the classrooms and doctors in the clinics, out of the tramp of soldiers marching, I shall make the pattern of my pledge:

“I am a Filipino born to freedom, and I shall not rest until freedom shall have been added unto my inheritance—for myself and my children and my children’s children—forever.”

Share this:

University of the philippines.

University of the Philippines Media and Public Relations Office Fonacier Hall, Magsaysay Avenue, UP Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Telephone number: (632) 8981-8500 Comments and feedback: [email protected]

University of the Philippines © 2024

UP would continue expanding under Villamor’s watch, with the Conservatory of Music; the University High School; the College of Education; and, the Junior College in Cebu City added under his watch

The School of Fine Arts (1909), the College of Liberal Arts (1909), the College of Veterinary Medicine (1910), the College of Engineering (1910), the College of Agriculture (1906, in Los Baños, Laguna) follow to form the initial core of the newly established UP.

The UP College of Medicine (then known as the Philippine Medical School) opens. It predates the opening of the University proper by 3 years.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The philippines: an overview of the colonial era.

| Interested in Philippine history? Purchase a copy of the AAS Key Issues in Asian Studies book: . |

In the Beginning

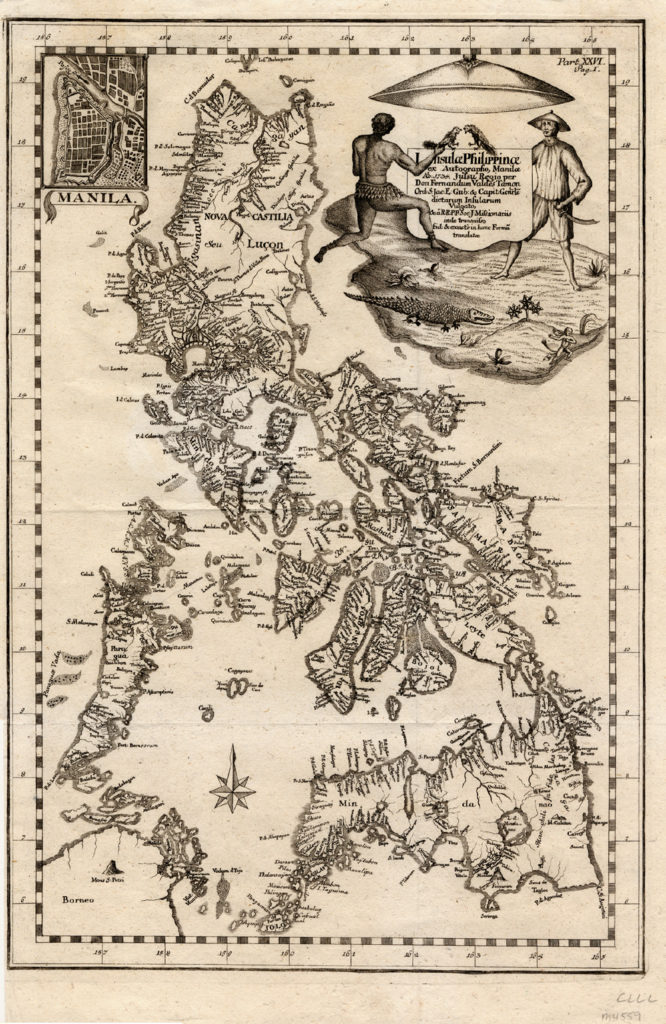

Although the details vary in the retelling, one Philippine creation myth focuses on this core element: a piece of bamboo, emerging from the primordial earth, split apart by the beak of a powerful bird. From the bamboo a woman and man come forth, the progenitors of the Filipino people. The genesis of the Philippine nation, however, is a more complicated historical narrative. During their sixteenth-century expansion into the East, Ferdinand Magellan and other explorers bearing the Spanish flag encountered several uncharted territories. Under royal decree, Spanish colonizers eventually demarcated a broad geographical expanse of hundreds of islands into a single colony, thus coalescing large groups of cultural areas with varying degrees of familiarity with one another as Las Islas Filipinas. Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, claiming this area for the future King Philip II of Spain in the mid-1500s, took possession of the islands while imagining the first borders of the future Philippine state. During Spanish rule, the boundaries of the empire changed as Spain conquered, abandoned, lost, and regained several areas in the region. Had other colonies been maintained or certain battles victorious, Las Islas Filipinas could have included, for example, territory in what is now Borneo and Cambodia. When, during the Seven Years’ War, Spain lost control of Manila from 1762–64, the area effectively became part of the British Empire. The issue of shifting boundaries notwithstanding, the modern-day cartographic image of the Philippine archipelago as a unified whole was credited to Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde, Francisco Suarez, and Nicolas de la Cruz who, in 1734, conceptualized, sketched, and engraved the first accurate map of the territory.

Explorers for Spain were not the first to encounter the islands. Chinese, Arabic, and Indian traders, for example, engaged in extensive commerce with local populations as early as 1000 AD. Yet it was the Spanish government that bound thousands of islands under a single colonial rule. The maps delineating Las Islas Filipinas as a single entity belied the ethnolinguistic diversity of the area. Although anthropological investigations continue, scholars believe Spain claimed territory encompassing over 150 cultural, ethnic, and linguistic groups. Within this colonial geography, however, Spain realized that the actual distance between the capital center of Manila and areas on the margins (as well as the very real problems with overcoming difficult terrain between communities) made ruling difficult. Socially and geographically isolated communities retained some indigenous traditions while experiencing Spanish colonial culture in varying degrees. Vicente Rafael’s White Love and Other Events in Filipino History (2000) chronicles this disconnection between the rule of the colonial center and those within the territorial borders. 1 His conclusions suggest in part that although the naming and mapping of Filipinas afforded the Spanish a certain legitimacy when claiming the islands, this was in some ways a cosmetic gesture. Instead of unifying the diverse local populations under one banner during the almost 400 years of Spanish rule, various groups remained fiercely independent or indifferent to the colonizer; some appropriated and reinterpreted Spanish customs, 2 while others toiled as slaves to the empire. 3

As they spread throughout the islands, Spanish conquistadors encountered a variety of religions; during the sixteenth century, the areas now referred to as the Luzon and Visayas cluster of islands were home to several belief systems that were chronicled by the Christian friars and missionaries who came into contact with them. Famed Philippine historian William Henry Scott (1994) recounts, for instance, examples of Visayans who “worshiped nature spirits, gods of particular localities or activities, and their own ancestors”; 4 Bikolanos whose “female shamans called baliyan . . . spoke with the voice of departed spirits, and delivered prayers in song”; 5 and Tagalogs whose pantheon included “Lakapati, fittingly represented by a hermaphrodite image with both male and female parts, [who] was worshipped in the fields at planting time.” 6 Over time, however, Spain’s colonial hegemony, power, and influence used to consolidate their rule spread through the vehicle of Catholicism, supplanting or heavily influencing several of the local spiritual traditions, which were transformed to fit the new religious paradigm. In the 1560s, Spaniard Miguel López de Legazpi introduced Catholic friars to the north. Christianity redefined the worldview and relationships of some of the locals, implementing a social structure heavily based on Biblical perspectives and injunctions. By the eighteenth century, indigenous people caught practicing so-called pagan rituals were punished; local histories written on bamboo or other materials were burned, and cultural artifacts were destroyed. Church edifices dominated the landscape as the symbolic and psychological center of the permanent villages and towns that sprung up around them. Once firmly established, the Catholic Church, through various religious orders with their own agendas, clearly shared power with Spain, and the two jointly administered the colonization of the islands.

However, Spanish Catholic colonial rule was incomplete. Domination of the southern half of the archipelago proved impossible due in large part to the earlier introduction of Islam in approximately 1380. Muslim traders traveled in and around the southern islands, and over time, these merchants likely married into wealthy local families, encouraging permanent settlements while spreading Islam throughout the area. By the time of Spanish arrival in the sixteenth century, the Islamic way of life was already well-established; for example, the Kingdom of Maynila (site of present-day Manila) was ruled by Rajah Sulayman, a Muslim who fought against Spanish conquest. Scholars agree that the Spanish arrival profoundly affected the course of Philippine history. Had Magellan or other colonizers never arrived or landed much later, they may have encountered a unified Muslim country. As history would have it, however, Spain encountered serious resistance in the Filipinas south, sowing the seeds of one of the oldest and bitterest divisions in contemporary Philippine society. Spanish colonizers soon realized they were against a strong, although not entirely uniform or unified, Muslim people. The constant struggle to extend Spanish hegemony to the south spawned the Spanish-Moro Wars, a series of long-standing hostilities between Muslims and Spanish. From the late 1500s until the late 1800s, Spain attempted to gain a foothold in the area— succeeding only to the extent that some soldiers were eventually allowed by local leaders to maintain a small military presence. Spanish colonial leaders, however, never dominated or governed the local area, despite laying claim to the territory.

Gabriela Silang Monument on Ayala Avenue, Manila. Source: Ayala Triangle website at http://tinyurl.com/kf5teob . The Catholic Church, through various religious orders with their own agendas, clearly shared power with Spain, and the two jointly administered the colonization of the islands.

Revolutionary Narratives

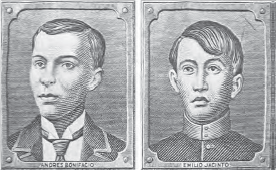

During the late eighteenth century, revolutionaries such as Gabriela and Diego Silang fought for a free Ilocano nation in the northern Philippines. Other revolutionaries emerged, and by the end of the nineteenth century, leaders such as Andrés Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto were pressuring Spanish leadership on several fronts. Future national hero José Rizal incurred the wrath of the colonial government with the publication of Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not, 1887) and El Filibusterismo (The Filibustering, 1891). Rizal, born to a relatively prosperous family of Filipino, Spanish, Chinese, and Japanese descent, was well-educated in the Philippines and in parts of Europe. A true renaissance man, Rizal was an ophthalmologist, scientist, writer, artist, and multilinguist whose works were written in several languages, including Spanish and Latin. Noli Me Tángere and El Filibusterismo , first published in Germany and Belgium, respectively, brought international attention to the abuses of the Filipino people by the colonial government and Catholic Church. Throughout Rizal’s life, he continued writing and advocating reforms such as the recognition of Filipinos as free and equal citizens to the Spanish. Rizal’s popularity grew amongst Filipinos fighting against Spanish oppression, drawing the suspicion of local officials who accused him of associating with armed insurgents. In 1896, Rizal was arrested and convicted of several crimes, including inciting rebellion, and was executed by firing squad on December 30. However, rather than suppressing the revolution, Rizal’s death cast him as a martyr for the cause, and his works were more widely disseminated and read by leaders fighting for an independent Philippines.

Today, Rizal’s immortality extends to national hero status, with numerous awards, national monuments, parks, associations, movies, poems, and books dedicated to his memory. Philippine government poster from the 1950s. Source: National Archives and Records Administration at http://tinyurl.com/moosqsu .

Today, Rizal’s immortality extends to national hero status, with numerous awards, national monuments, parks, associations, movies, poems, and books dedicated to his memory. Rizal’s writings proliferate on the Internet. His works, once considered seditious propaganda by some, are now available as free downloads. 7 Admirers who take to social media characterize Rizal as their hero and post facts about his background and achievements or quotes from his texts. 8 The power of Rizal’s narratives transcend the paper documents handwritten 125 years ago. He is remembered as a Filipino writing for his people, a native son who used the tools of storytelling to expose the truth about life under colonial rule.

Colonialism: The Sequel

Scholars argue that the execution of Rizal inspired a broader fight for freedom from the Spanish government. Led by heroes such as Bonifacio, the Philippine Revolution began in 1896 and included numerous battles against Spanish forces on multiple fronts. By 1898, as Spain was fighting to quell the uprisings in the Philippines, it became embroiled in the Spanish-American War. After losing to the United States in several land and naval battles, Spain released the Philippines and other colonies to the US in exchange for US $20 million, as agreed upon in the Treaty of Paris of 1898. During the negotiation of the treaty, the American Anti-Imperialist League opposed the annexation of the Philippines. Composed of social, political, and economic luminaries of the era (for example, activist Jane Addams and former President Grover Cleveland), the league organized a series of publications criticizing the US government’s colonial policies. Mark Twain, prominent author, wrote for the The New York Herald in 1900:

I have read carefully the Treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . . . It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land. 9

The treaty was hotly debated by the Senate. Ultimately, ratification of the treaty was approved on February 6, 1899, by a vote of fifty-seven in favor and twenty-seven against—a single vote more than the required twothirds majority. Meanwhile in the Philippines, Emilio Aguinaldo, a Filipino leader in the fight for freedom, declared an independent Philippine government—which neither the Spanish nor United States governments acknowledged. When the final version of the Treaty of Paris was enacted, the islands once again became subject to the laws and policies of another distant nation.

Americans who supported annexing the Philippines viewed the archipelago as a doorway through which the United States could gain more of a financial foothold in Asia while extending its empire overseas. Before the US could begin fully establishing control of the islands, a new war began. Some scholars have termed it “the first Việt Nam,” referencing the extended armed conflict which ended in 1975 between North Việt Nam and the US, whom many North Vietnamese also perceived as an imperialist aggressor. The Philippine-American war began on February 4, 1899, when American soldiers opened fire on Filipinos in Manila. In the first years of US occupation, the battles were fought between the new US colonizers and Filipino guerrilla armies tired of existing under any foreign rule. James Hamilton-Paterson, a British travel writer and commentator on the Philippines, estimates that the war’s death toll included over 4,000 American and 16,000 Filipino soldiers, as well as almost one million civilians who perished from hunger and disease. 10 Although the war officially ended in 1902, skirmishes continued for several years afterward.

Under the rule of the United States, a plethora of people, ideas, and changes to the infrastructure flooded the archipelago. During this era, Christian groups flourished as Protestants and other denominations began proselytizing via missionary expeditions. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the YMCA began operations in the Philippines; the so-called “Big Three” of American voluntary associations, the Lions Club, Kiwanis, and Rotary, also quickly spread throughout the islands. The United States military sponsored the establishment of hospitals and funded improvements to roads and bridges. Prominent urban planner Daniel Burnham visited the Philippines in 1904 and designed the capital city of Manila for redevelopment. 11 US culture dominated Philippine life. Linguist Bonifacio P. Sibayan, for example, discusses the introduction of English by American colonial authorities as the medium of instruction in schools: “English thus became the only medium of instruction in the schools, the only language approved for use in the school, work, in public school buildings, and on public school playgrounds.” 12 Sibayan further explains that while English-only eventually changed to bilingual instruction, English usage had become pervasive throughout the whole of society. Throughout the business and government sector, English became the dominant language, as well as the language that bridged communication gaps between regional Filipino cultural groups who did not share an indigenous language.Today, English, along with Filipino, is recognized as a national language of the Philippines. Renato Constantino, Filipino scholar, characterized the introduction of English as a detriment to Filipino society: “With American textbooks, Filipinos started learning not only the new language but also a new way of life, alien to their traditions . . . This was the beginning of their education, and at the same time, their miseducation.” 13 Filipino linguists and other social scientists continue researching and debating the extent to which indigenous cultural values and traditions were lost with the change in language. 14 Nevertheless, English proved beneficial to at least some Filipinos. The US government sponsored some students from the elite upper class to study in American schools and, upon their return, work in the government. Other Filipinos, recruited by US companies beginning in the colonial era, migrated to California, Hawai`i, and other states, lured by the promise of lucrative work compared to wage rates picking sugarcane and pineapple in the Philippines. With at least some familiarity with the language, Filipinos were able to communicate with their foreign employers.

In 1935, the United States designated the Philippines as a commonwealth and established a Philippine government that was meant to transition to full independence. During World War II, however, Japan attacked the Philippines and held the country from 1941 to 45. Lydia N. Yu-Jose in “World War II and the Japanese in the Prewar Philippines” (1996) describes an immigrant population of approximately 20,000 Japanese people living in the islands prior to the war. 15 Some were temporary migrants, content to work in the Philippines for several years and then return to Japan with their earnings. Others were permanent settlers, many of whom would go on, for example, to establish agricultural operations, open factories, and begin logging operations. Some of these Japanese business owners, Yu-Jose explains, were utilized as advisers and installed as local leaders by the occupying army. Initially, some regarded the Japanese as liberators, freeing the Philippines from the United States and bringing the islands into the Japanese empire. However, in light of the subsequent war atrocities, harsh realities came to light. In October 1943, the Japanese established what is now referred to as the Second Philippine Republic, with José P. Laurel as president. Widely recognized as simply a puppet government, the dominating Japanese military continued occupying the area. Local factories under Japanese control produced goods for the war effort while Filipinos suffered food shortages.

Against this backdrop, Filipinos once again organized widespread resistance throughout the islands. Over 250,000 people used guerrilla warfare tactics against Japanese occupiers, who steadily lost control as the war continued. During the war, famed General Douglas MacArthur also organized American troops to fight alongside the Filipinos. From February to March 1945, Filipino soldiers and US troops fought in the Battle of Manila, which would eventually mark the end of the occupation. During this month, at least 100,000 civilians died at the hands of Japanese soldiers. Overall, scholars estimate between 500,000 and one million deaths of Filipinos during the World War II Japanese occupation.

After the end of the war, the United States and the Philippines signed the Treaty of Manila on July 4, 1946; Manuel Roxas transitioned from the President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines to first President of an independent Philippine Republic.

Guide to the Present

Yet while “independent” implied a Philippines officially free from foreign rule, many contemporary narratives of Filipino identity, citizenship, and statehood are inevitably influenced by the colonial past and, some say, the continuing undue influence of other countries. The political, social, and economic elites of the country, for example, are often members of the same families that have held power in the country for generations. Gavin Shatkin’s “Obstacles to Empowerment: Local Politics and Civil Society in Metropolitan Manila, the Philippines” 16 traces how Spanish and US colonial authorities granted extensive rights and privileges to favored landowners. Many of these families later leveraged their power into political and economic dynasties, leading to a contemporary Philippine government mired in nepotism, cronyism, and corruption. 17

After war reparations were paid in the 1950s, Japanese businesses and investors soon returned to the islands. Today, Japan is a strategic economic and political partner of the Philippine government. However, as in the aftermath of Spanish and United States colonialism, Filipinos still struggle with defining a national identity after such widespread traumas. Other challenges for the Philippine state today include settling a territorial dispute regarding areas of the South China Sea with the People’s Republic of China; allowing the return of the United States military to the islands; brokering a lasting peace with the historically Muslim-dominated south; coping with the increasing number of Filipinos working overseas, as well as the subsequent social and economic consequences of this migration; and reducing poverty. These realities, juxtaposed against the Philippine Department of Tourism slogan, “It’s more fun in the Philippines,” suggests that understanding today’s Republic of the Philippines means studying the historical roots of power and influences born from the imposition of colonial structures.

Philippines

Geography and population.

Area: 120,000 square miles; slightly larger than Arizona

Population: 107 million

Freedom House rating from “ Freedom in the World 2015” (ranking of political rights and civil liberties in 195 countries): Partly Free

Type: Republic

Chief of State and Head of Government: President Benigno Aquino (since June 30, 2010)

Elections: President elected by popular vote and serves a single six-year term

Legislative Branch: Bicameral Congress; Senate (twenty-four seats, half of the seats are elected every three years, elected by popular vote, serving six-year terms) and House of Representatives (287 seats, all seats elected by popular vote every three years, serving three-year terms)

Judicial Highest Courts: Supreme Court (chief justice and fourteen associate justices)

Judges: Appointed by president on recommendations by the Judicial and Bar Council and serve until age seventy

The Philippines’ economy is continuing to grow and is moving away from agriculture exports and toward electronics and oil.

GDP: $694.5 billion

Per Capita Income: $7,000

Unemployment Rate : 7.2 percent

Population Below Poverty Line: 26.5 percent Inflation Rate: 4.5 percent

Agricultural Products: Sugarcane, coconuts, rice, corn, bananas, pork, beef, fish

Industries: Electronics assembly, garments, footwear, petroleum refining

Religion: 82.9 percent Catholic, 5 percent Muslim, 2.8 percent Evangelical Christian, 2.3 percent Iglesia ni Kristo (English translation: Church of Christ [different from US Church of Christ]), 4.5 percent other Christian

Life Expectancy: Approximately 72 years

Literacy Rate: 95.4 percent

Major Contemporary Issues

Security: The Philippine government has been dealing with insurgent groups throughout the past couple of decades. Peace talks with the Moro insurgents have brought some stability to the islands, but the government also must deal with the New People’s Army, a Communist insurgent group inspired by Maoist principles. The Philippines and China are also in a dispute over sovereignty for the Spratly Islands.

Drugs: The Philippines are a major consumer and producer of methamphetamines, as well as a producer of marijuana. The government has attempted crackdowns on both but has been unsuccessful so far.

CIA. “The World Factbook: Philippines.” Last modified June 20, 2014. http://tinyurl.com/2y58zo .

Freedom house. “freedom in the world 2015.” accessed february 11, 2015. http://tinyurl.com/ knwvzk6 ., share this:.

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

1. Vicente Rafael, White Love and Other Events in Filipino History (Manila: Ateneo de Manila Press, 2000).

2. Reinhard Wendt, “Philippine Fiesta and Colonial Culture,” Philippine Studies 46, no. 1 (1998) 3–23.

3. Rosario M. Cortes, Celestina P. Boncan, and Ricardo T. Jose, The Filipino Saga: History as Social Change (Quezon City: New Day Publisher, 2000); Vicente L. Rafael, Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society Under Early Spanish Rule (Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1998); William H. Scott, “The Spanish Occupation of the Cordillera in the 19th Century” in Philippine Social History: Global Trade and Local Transformations , ed. A.W. McCoy et al. (Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1982).

4. William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society (Manila: Ateneo de Manila Press, 1994), 77.

5. Ibid., 185.

6. Ibid., 234.

7. “Books by Rizal, José (sorted by popularity),” Project Gutenberg, accessed March 10, 2014, http://tinyurl.com/ku7fygt .

8. “José Rizal: Not Your Ordinary One Peso Guy,” accessed March 10, 2014, http://tinyurl.com/lr9gvht.

9. Excerpt from the October 15, 1900 New York Herald. See “Mark Twain— The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War,” Library of Congress, accessed September 13, 2014, http://tinyurl.com/y4zyea.

10. James Hamilton-Paterson, America’s Boy: A Century of Colonialism in the Philippines (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 1998), 33.

11. Ian Morley, “America and the Philippines,” Education About Asia 16, no. 2 (2011) 34–38.

12. Bonifacio P. Sibayan, The Intellectualization of Filipino and Other Essays on Education and Sociolinguistics (Manila: De La Salle University Press, 1999), 543.

13. Renato Constantino, The Miseducation of the Filipino (Quezon City: Foundation for Nationalist Studies, 1982), 6; quoted in ibid., 551.

14. See Laura M. Ahearn, “Language, Thought, and Culture,” in Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology (Malden: Wiley-Backwell, 2012), 65–98 for a general overview of the research regarding language, local traditions, and culture change.

15. Lydia N. Yu-Jose, “World War II and the Japanese in Prewar Philippines,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 64.

16. Gavin Shatkin, “Obstacles to Empowerment: Local Politics and Civil Society in Metropolitan Manila, the Philippines,” Urban Studies 37, no. 12 (2000): 2357–2375.

17. “Transparency International: the Global Coalition Against Corruption,” accessed September 13, 2014, http://tinyurl.com/qfms53j .

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

The AAS Secretariat is closed on Monday, September 2 in observance of the Labor Day holiday

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Adobo is ‘paksiw,’ and other terms in Filipino food history

The great historian and anthropologist of Filipino food, Doreen Fernandez, wrote many classics in her quest to promote the idea of Filipino food as a cuisine, rather than the simple food of a backwater country in Southeast Asia. In a sense, her work was in line with the work of the indigenization movements elsewhere in Philippine academia. Her influence on the transformation in Filipinos’ eyes of their own cuisine into something worthy of reverence cannot be overstated.

However, her discussion of adobo in the hugely important book “Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture,” betrays a common belief that seems to be based on language, and something that she avoided in all other cases. In fact, while the book itself is largely about native cuisine, the book takes great care in one of its chapters to show how certain foods and food terms from Mexico came to be in the Philippines. Which makes the entry on adobo rather curious to me.

Fernandez says that adobo seems to have been indigenized from Mexican adobo, but her only real rationale is the word “adobo” itself, after noting how divergent the actual foods are: one is pickled with spices, lemon juice, and condiments, while the other is pickled with vinegar and spices. There does not seem to be a clear relationship in a culinary sense. She also notes that the American food historian Raymond Sokolov thinks the term “adobo” was applied to a native Filipino cooking style by Spanish colonizers.

But we already know that preserving food in “suka” is common throughout the Philippines, for example with “kinilaw.” Kinilaw was actually indigenized by Mexicans as ceviche, when Filipinos were brought as enslaved shipbuilders to Mexico. Vinegar is a staple of food preparation throughout Southeast Asia, supporting the idea that adobo is indigenous.

But aside from this we can also consult the linguist Carl Rubino, an expert on Philippine languages who has done extensive dictionaries for Tagalog, Ilokano, and an entire academic study of Tausug grammar. It is in Rubino’s work on Tagalog that we can piece together some interesting history. Rubino gathers a definition of “paksiw” as: “n. fish or meat cooked in vinegar, garlic, and salt.” This simple, anthropologically gathered definition explains a lot about precolonial food and the origins of adobo. Paksiw is a class of food in modern Tagalog. Kinilaw, for example, would also be a type of paksiw in this sense. Of course there are well-known dishes such as paksiw na isda, even today.

Many sources, including Fernandez, say that (assuming Sokolov is correct) the indigenous word for adobo is lost and only the imported word from Mexico is used today. However, the answer to this modern question about adobo’s origins or naming history has actually been in everyone’s faces for many decades, if not at least a century. It is that adobo is paksiw, and that paksiw is the original native term for adobo. This makes a lot of sense once someone considers a dish such as adobong puti. Adobong puti is often considered the original, precolonial adobo, since “toyo” seems to have been added as a variation by Chinese migrants during the colonial period. Adobong puti is literally the textbook definition of what paksiw is in its bare bones form.

Some implications from this: Adobo is indigenous with an indigenous name that is still in usage, such as in paksiw na isda or paksiw na baboy. Also, as Fernandez discussed in her overarching argument for that section of her book, indigenization and term swapping was common in the Philippines. Menudo has very little in common with Mexican menudo (i.e., the “original,” which is a spicy soup made with tripe). In my opinion, menudo as a word could be similar to adobo, since there is a precolonial word still used today that also describes what menudo is: “kare.” Kare comes from the Tamil word, “kari,” which is also where the English word “curry” originates.

It also reflects the relationship between “lugaw,” “goto,” and “arroz caldo,” and “champurrado.” From the names of arroz caldo and champurrado, one would think they are Spanish or Mexican dishes, but they are both ultimately variations of lugaw or goto, which are Tagalog terms for rice porridge. “Inihaw” and “lechon” have a similar relationship.

My conclusion is that the influence of Spain on Filipino cuisine is actually not particularly exceptional when compared to other Asian countries. They seem to be mere names added by the Spaniards, rather than actual food additions. Filipino foods and flavors are certainly “Asian” in character.

—————-

Sterling V. Herrera Shaw received his master’s degree in Philippine Studies from the University of the Philippines Diliman, where his focus is on sociocultural and development studies.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Pre-Spanish history of the Philippines

The spanish period in the philippines, the 19th century in the philippines, the philippine revolution, the period of u.s. influence.

- World War II

- The early republic

- Martial law

- The downfall of Marcos and return of democratic government

- The Philippines since c. 1990

history of the Philippines

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- American Historical Association - When Did Philippine History Begin?

- GlobalSecurity.org - Philippines History

- Philippine History - Synopsis of Philippine History

- Association for Asian Studies - The Philippines: An Overview of the Colonial Era

- Marimari.com - History of Philippines

- he Philippines and the University of Michigan, 1870-1935! - The Philippines: Historical Overview

- Table Of Contents

history of the Philippines , a survey of notable events and people in the history of the Philippines . The Philippines takes its name from Philip II , who was king of Spain during the Spanish colonization of the islands in the 16th century. Because it was under Spanish rule for 333 years and under U.S. tutelage for a further 48 years, the Philippines has many cultural affinities with the West. The country was wracked by political turmoil in the last quarter of the 20th century. After enduring more than a decade of authoritarian rule under Pres. Ferdinand Marcos , the broadly popular People Power movement in 1986 led a bloodless uprising against the regime. The confrontation resulted not only in the ouster and exile of Marcos but also in the restoration of democratic government to the Philippines.

The Philippines is the only country in Southeast Asia that was subjected to Western colonization before it had the opportunity to develop either a centralized government ruling over a large territory or a dominant culture . In ancient times the inhabitants of the Philippines were a diverse agglomeration of peoples who arrived in various waves of immigration from the Asian mainland and who maintained little contact with each other. Contact with Chinese traders was recorded in 982, and some cultural influences from South Asia , such as a Sanskrit -based writing system, were carried to the islands by the Indonesian empires of Srivijaya (7th–13th century) and Majapahit (13th–16th century); but in comparison with other parts of the region, the influence of both China and India on the Philippines was of little importance. The peoples of the Philippine archipelago, unlike most of the other peoples of Southeast Asia, never adopted Hinduism or Buddhism .

According to what can be inferred from somewhat later accounts, the Filipinos of the 15th century must have engaged primarily in shifting cultivation , hunting , and fishing . Sedentary cultivation was the exception. Only in the mountains of northern Luzon , where elaborate rice terraces were built some 2,000 years ago, were livelihood and social organization linked to a fixed territory. The lowland peoples lived in extended kinship groups known as barangay s , each under the leadership of a datu , or chieftain. The barangay , which ordinarily numbered no more than a few hundred individuals, was usually the largest stable economic and political unit.

Within the barangay the status system, though not rigid, appears to have consisted of three broad classes: the datu and his family and the nobility, freeholders, and “dependents.” This third category consisted of three levels—sharecroppers, debt peons , and war captives—the last two levels being termed “slaves” by Spanish observers. The status of the debt peons and war captives was inherited but, through manumission and interclass marriage, seldom extended over more than two generations. The fluidity of the social system was in part the consequence of a bilateral kinship system in which lineage was reckoned equally through the male and female lines. Marriage was apparently stable, though divorce was socially acceptable under certain circumstances.

Early Filipinos followed various local religions, a mixture of monotheism and polytheism in which the latter dominated. The propitiation of spirits required numerous rituals, but there was no obvious religious hierarchy . In religion, as in social structure and economic activity, there was considerable variation between—and even within—islands.

This pattern began to change in the 15th century, however, when Islam was introduced to Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago through Brunei on the island of Borneo . Along with changes in religious beliefs and practices came new political and social institutions. By the mid-16th century two sultanates had been established, bringing under their sway a number of barangay s. A powerful datu as far north as Manila embraced Islam. It was in the midst of this wave of Islamic proselytism that the Spanish arrived. Had the Spanish come a century later or had their motives been strictly commercial, Filipinos today might be a predominantly Muslim people.

Spanish colonial motives were not, however, strictly commercial. The Spanish at first viewed the Philippines as a stepping-stone to the riches of the East Indies (Spice Islands), but, even after the Portuguese and Dutch had foreclosed that possibility, the Spanish still maintained their presence in the archipelago.

The Portuguese navigator and explorer Ferdinand Magellan headed the first Spanish foray to the Philippines when he made landfall on Cebu in March 1521; a short time later he met an untimely death on the nearby island of Mactan . After King Philip II had dispatched three further expeditions that ended in disaster, he sent Miguel López de Legazpi , who established the first permanent Spanish settlement, in Cebu, in 1565. The Spanish city of Manila was founded in 1571, and by the end of the 16th century most of the coastal and lowland areas from Luzon to northern Mindanao were under Spanish control. Friars marched with soldiers and soon accomplished the nominal conversion to Roman Catholicism of all the local people under Spanish administration. But the Muslims of Mindanao and Sulu, whom the Spanish called Moros , were never completely subdued by Spain.

Spanish rule for the first 100 years was exercised in most areas through a type of tax farming imported from the Americas and known as the encomienda . But abusive treatment of the local tribute payers and neglect of religious instruction by encomenderos (collectors of the tribute), as well as frequent withholding of revenues from the crown, caused the Spanish to abandon the system by the end of the 17th century. The governor-general, himself appointed by the king, began to appoint his own civil and military governors to rule directly.

Central government in Manila retained a medieval cast until the 19th century, and the governor-general was so powerful that he was often likened to an independent monarch. He dominated the Audiencia , or high court, was captain-general of the armed forces, and enjoyed the privilege of engaging in commerce for private profit.

Manila dominated the islands not only as the political capital. The galleon trade with Acapulco , Mexico , assured Manila’s commercial primacy as well. The exchange of Chinese silks for Mexican silver not only kept in Manila those Spanish who were seeking quick profit, but it also attracted a large Chinese community . The Chinese, despite being the victims of periodic massacres at the hands of the Spanish, persisted and soon established a dominance of commerce that survived through the centuries.

Manila was also the ecclesiastical capital of the Philippines. The governor-general was civil head of the church in the islands, but the archbishop vied with him for political supremacy. In the late 17th and 18th centuries the archbishop, who also had the legal status of lieutenant governor, frequently won. Augmenting their political power, religious orders, Roman Catholic hospitals and schools, and bishops acquired great wealth, mostly in land. Royal grants and devises formed the core of their holdings, but many arbitrary extensions were made beyond the boundaries of the original grants.

The power of the church derived not simply from wealth and official status. The priests and friars had a command of local languages rare among the lay Spanish, and in the provinces they outnumbered civil officials. Thus, they were an invaluable source of information to the colonial government. The cultural goal of the Spanish clergy was nothing less than the full Christianization and Hispanization of the Filipino. In the first decades of missionary work, local religions were vigorously suppressed; old practices were not tolerated. But as the Christian laity grew in number and the zeal of the clergy waned, it became increasingly difficult to prevent the preservation of ancient beliefs and customs under Roman Catholic garb. Thus, even in the area of religion, pre-Spanish Filipino culture was not entirely destroyed.

Economic and political institutions were also altered under Spanish impact but perhaps less thoroughly than in the religious realm. The priests tried to move all the people into pueblos, or villages, surrounding the great stone churches. But the dispersed demographic patterns of the old barangay s largely persisted. Nevertheless, the datu ’s once hereditary position became subject to Spanish appointment.

Agricultural technology changed very slowly until the late 18th century, as shifting cultivation gradually gave way to more intensive sedentary farming, partly under the guidance of the friars. The socioeconomic consequences of the Spanish policies that accompanied this shift reinforced class differences. The datu s and other representatives of the old noble class took advantage of the introduction of the Western concept of absolute ownership of land to claim as their own fields cultivated by their various retainers, even though traditional land rights had been limited to usufruct. These heirs of pre-Spanish nobility were known as the principalia and played an important role in the friar-dominated local government.

By the late 18th century, political and economic changes in Europe were finally beginning to affect Spain and, thus, the Philippines. Important as a stimulus to trade was the gradual elimination of the monopoly enjoyed by the galleon to Acapulco. The last galleon arrived in Manila in 1815, and by the mid-1830s Manila was open to foreign merchants almost without restriction. The demand for Philippine sugar and abaca (hemp) grew apace, and the volume of exports to Europe expanded even further after the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869.

The growth of commercial agriculture resulted in the appearance of a new class. Alongside the landholdings of the church and the rice estates of the pre-Spanish nobility there arose haciendas of coffee , hemp , and sugar , often the property of enterprising Chinese-Filipino mestizos. Some of the families that gained prominence in the 19th century have continued to play an important role in Philippine economics and politics.

Not until 1863 was there public education in the Philippines, and even then the church controlled the curriculum. Less than one-fifth of those who went to school could read and write Spanish, and far fewer could speak it properly. The limited higher education in the colony was entirely under clerical direction, but by the 1880s many sons of the wealthy were sent to Europe to study. There, nationalism and a passion for reform blossomed in the liberal atmosphere. Out of this talented group of overseas Filipino students arose what came to be known as the Propaganda Movement . Magazines , newspapers , poetry , and pamphleteering flourished , most notably the biweekly paper La Solidaridad , which began publication in 1889. José Rizal , this movement’s most brilliant figure, produced two political novels— Noli me tangere (1887; Touch Me Not ) and El filibusterismo (1891; The Reign of Greed )—which had a wide impact in the Philippines. In 1892 Rizal returned home and formed the Liga Filipina, a modest reform-minded society, loyal to Spain, that breathed no word of independence. But Rizal was quickly arrested by the overly fearful Spanish, exiled to a remote island in the south, and executed in 1896. Meanwhile, within the Philippines there had developed a firm commitment to independence among a somewhat less privileged class.

Shocked by the arrest of Rizal in 1892, these activists quickly formed the Katipunan under the leadership of Andres Bonifacio , a self-educated warehouseman. The Katipunan was dedicated to the expulsion of the Spanish from the islands, and preparations were made for armed revolt. Filipino rebels had been numerous in the history of Spanish rule, but now for the first time they were inspired by nationalist ambitions and possessed the education needed to make success a real possibility.

In August 1896, Spanish friars uncovered evidence of the Katipunan’s plans, and its leaders were forced into premature action. Revolts broke out in several provinces around Manila. After months of fighting, severe Spanish retaliation forced the revolutionary armies to retreat to the hills. In December 1897 a truce was concluded with the Spanish. Emilio Aguinaldo , a municipal mayor and commander of the rebel forces, was paid a large sum and was allowed to go to Hong Kong with other leaders; the Spanish promised reforms as well. But reforms were slow in coming, and small bands of rebels, distrustful of Spanish promises, kept their arms; clashes grew more frequent.

Meanwhile, war had broken out between Spain and the United States (the Spanish-American War ). After the U.S. naval victory in the Battle of Manila Bay in May 1898, Aguinaldo and his entourage returned to the Philippines with the help of Adm. George Dewey . Confident of U.S. support, Aguinaldo reorganized his forces and soon liberated several towns south of Manila. Independence was declared on June 12 (now celebrated as Independence Day). In September a constitutional congress met in Malolos , north of Manila, which drew up a fundamental law derived from European and Latin American precedents. A government was formed on the basis of that constitution in January 1899, with Aguinaldo as president of the new country, popularly known as the “Malolos Republic.”

Meanwhile, U.S. troops had landed in Manila and, with important Filipino help, forced the capitulation in August 1898 of the Spanish commander there. The Americans, however, would not let Filipino forces enter the city. It was soon apparent to Aguinaldo and his advisers that earlier expressions of sympathy for Filipino independence by Dewey and U.S. consular officials in Hong Kong had little significance. They felt betrayed.

U.S. commissioners to the peace negotiations in Paris had been instructed to demand from Spain the cession of the Philippines to the United States; such cession was confirmed with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. Ratification followed in the U.S. Senate in February 1899, but with only one vote more than the required two-thirds. Arguments of “ manifest destiny ” could not overwhelm a determined anti-imperialist minority.

By the time the treaty was ratified, hostilities had already broken out between U.S. and Filipino forces. Since Filipino leaders did not recognize U.S. sovereignty over the islands and U.S. commanders gave no weight to Filipino claims of independence, the conflict was inevitable. It took two years of counterinsurgency warfare and some wise conciliatory moves in the political arena to break the back of the nationalist resistance. Aguinaldo was captured in March 1901 and shortly thereafter appealed to his countrymen to accept U.S. rule.

The Filipino revolutionary movement had two goals, national and social. The first goal, independence, though realized briefly, was frustrated by the American decision to continue administering the islands. The goal of fundamental social change , manifest in the nationalization of friar lands by the Malolos Republic, was ultimately frustrated by the power and resilience of entrenched institutions. Share tenants who had rallied to Aguinaldo’s cause, partly for economic reasons, merely exchanged one landlord for another. In any case, the proclamation of a republic in 1898 had marked the Filipinos as the first Asian people to try to throw off European colonial rule.

The juxtaposition of U.S. democracy and imperial rule over a subject people was sufficiently jarring to most Americans that, from the beginning, the training of Filipinos for self-government and ultimate independence—the Malolos Republic was conveniently ignored—was an essential rationalization for U.S. hegemony in the islands. Policy differences between the two main political parties in the United States focused on the speed with which self-government should be extended and the date on which independence should be granted.

In 1899 Pres. William McKinley sent to the Philippines a five-person fact-finding commission headed by Cornell University president Jacob G. Schurman. Schurman reported back that Filipinos wanted ultimate independence, but this had no immediate impact on policy. McKinley sent the Second Philippine Commission in 1900, under William Howard Taft ; by July 1901 it had established civil government.

In 1907 the Philippine Commission , which had been acting as both legislature and governor-general’s cabinet, became the upper house of a bicameral body. The new 80-member Philippine Assembly was directly elected by a somewhat restricted electorate from single-member districts, making it the first elective legislative body in Southeast Asia. When Gov.- Gen. Francis Burton Harrison appointed a Filipino majority to the commission in 1913, the American voice in the legislative process was further reduced.

Harrison was the only governor-general appointed by a Democratic president in the first 35 years of U.S. rule. He had been sent by Woodrow Wilson with specific instructions to prepare the Philippines for ultimate independence, a goal that Wilson enthusiastically supported. During Harrison’s term, a Democratic-controlled Congress in Washington, D.C., hastened to fulfill long-standing campaign promises to the same end. The Jones Act , passed in 1916, would have fixed a definite date for the granting of independence if the Senate had had its way, but the House prevented such a move. In its final form the act merely stated that it was the “purpose of the people of the United States” to recognize Philippine independence “as soon as a stable government can be established therein.” Its greater importance was as a milestone in the development of Philippine autonomy . Under Jones Act provisions, the commission was abolished and was replaced by a 24-member Senate, almost wholly elected. The electorate was expanded to include all literate males.

Some substantial restrictions on Philippine autonomy remained, however. Defense and foreign affairs remained exclusive U.S. prerogatives . American direction of Philippine domestic affairs was exercised primarily through the governor-general and the executive branch of insular government. There was little more than one decade of thoroughly U.S. administration in the islands, however—too short a time in which to establish lasting patterns. Whereas Americans formed 51 percent of the civil service in 1903, they were only 29 percent in 1913 and 6 percent in 1923. By 1916 Filipino dominance in both the legislative and judicial branches of government also served to restrict the U.S. executive and administrative roles.

By 1925 the only American left in the governor-general’s cabinet was the secretary of public instruction, who was also the lieutenant governor-general. This is one indication of the high priority given to education in U.S. policy. In the initial years of U.S. rule, hundreds of schoolteachers came from the United States. But Filipino teachers were trained so rapidly that by 1927 they constituted nearly all of the 26,200 teachers in public schools. The school population expanded fivefold in a generation; education consumed half of governmental expenditures at all levels, and educational opportunity in the Philippines was greater than in any other colony in Asia.

As a consequence of this pedagogical explosion, literacy doubled to nearly half in the 1930s, and educated Filipinos acquired a common language and a linguistic key to Western civilization. By 1939 some one-fourth of the population could speak English, a larger proportion than for any of the native dialects . Perhaps more important was the new avenue of upward social mobility that education offered. Educational policy was the only successful U.S. effort to establish a sociocultural basis for political democracy.