Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Long, short, and efficient titles for research articles

A Concise Guide to Communication in Science and Engineering

- By David H. Foster

- September 4 th 2018

The title of a research article has an almost impossible remit. As the freely available representative of the work, it needs to accurately capture what was achieved, differentiate it from other works, and, of course, attract the attention of the reader, who might be searching a journal’s contents list or the return from a database query. The title needs also, in passing, to signal the author’s competence and authority. Getting it right is vital. Success or otherwise is likely to decide whether the article is retrieved, read, and potentially cited by other researchers—crucial for recognition in science.

Is a long title or a short one better? A long title has obvious advantages in communicating content, but if it is too long, it may be difficult to digest, inducing the reader—with little time and commitment—to move on to the next article in his or her search. Conversely, a short title may be easy to digest, but too short to inform, leaving the reader again to move on. These considerations suggest there is an optimum number of words: enough to reflect content, yet not enough to bore.

The traditional recommendation from manuals on scientific writing and from academic publishers is that 10–12 words is about right, certainly no more, although the evidential basis is uncertain. Do authors follow this guidance? I took a sample of 4,000 article titles from the Web of Science database, published by Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters). The articles were from eight research areas: physics, chemistry, mathematics, cell biology, computer science, engineering, psychology, and general and internal medicine. The average or mean title length was 12.3 words, surprisingly close to the 10–12-word recommendation.

This estimate is necessarily subject to sampling error. Furthermore, it depends on the publication year from which the articles are taken. The mean title length of 12.3 words just quoted was for 2012. It was somewhat smaller at 10.9 words in 2002 and smaller still at 10.1 words in 1982. Mean title length also depends on the choice of subject area, the definition of journal article, and the coverage of the database (whose evolution may have contributed to the growth in mean title length). Nevertheless, reassuringly similar values emerged from an analysis of a larger sample of titles taken from the Scopus database, published by Elsevier.

On average, then, title lengths comply with expectations, possibly reflecting the wisdom of crowds, or of editors. Individually, however, title lengths vary enormously, with around 10% having either fewer than five words or more than 20. So, do articles with extreme titles—those whose lengths fall very far from the mean—succeed in attracting the attention of readers?

Here are two very short titles. The first is from a review article published in 2012 in the Annual Review of Psychology :

“Intelligence”

This article has had more than 180 citations, placing it in the top 1% in its subject area and publication year (citations and centiles for subject areas taken from Scopus for the period 2012–18). As a review article in the social sciences, though, it might be expected to be highly cited. The second title is from an original experimental research article published in 2012 in Physical Review Letters , which in spite of its name is not a review journal:

“Orthorhombic BiFeO3”

The topic addressed is less generally accessible, yet this article has had more than 40 citations and is in the top 7% for its area and year.

Importantly, adding more words to these titles to make them more specific does not seem to deliver a proportional gain in information. Consider expanding “Intelligence” to “An Overview of Contributions to Intelligence Research” or changing “Orthorhombic BiFeO3” to “Creation of a new orthorhombic phase of the multiferroic BiFeO3.” The additions, drawn from the article abstracts, just make explicit what is already largely implied.

So, do articles with extreme titles—those whose lengths fall very far from the mean—succeed in attracting the attention of readers?

By contrast with these very short titles, here are two very long ones. The first has 33 words—with hyphens treated as separators—and was published in 2012 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology :

“Cost-effectiveness of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: Results of the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial (Cohort A)”

With more than 120 citations, this article is in the top 1% for its area and year. This performance is not peculiar to general and internal medicine. Articles with very long titles from engineering disciplines can also do well. The second title is from an article published in 2012 in Optics Letters and has about 25 words, depending on definitions:

“Fiber-wireless transmission system of 108 Gb/s data over 80 km fiber and 2×2 multiple-input multiple-output wireless links at 100 GHz W-band frequency”

This article has had more than 110 citations and is in the top 1% for its area and year.

Despite the exceptional lengths of these titles, removing words or phrases, for example, from the first, “Results of the PARTNER . . . (Cohort A)” or, from the second, “at 100 GHz W-band frequency,” seems to result in a disproportionate loss in information and could actually mislead the reader.

Evidently, short titles need not fail to inform and long titles need not promote disengagement. Each can be as effective as the other and lead to high levels of recognition. The implication is that length, on its own, is a poor proxy for something more relevant and fundamental, namely how much the title tells the reader about the work given the number of words it expends.

What is being described here is a kind of efficiency. To paraphrase the statistician and artist Edward Tufte, albeit speaking in a different context, an efficient title is one that maximizes the ratio of the information communicated to its length. Accordingly, the number of words should be immaterial, or almost so. After all, it is what they communicate that really counts.

Featured image credit: Straying Thoughts by Edmund Blair Leighton. Public Domain via Flickr .

David H. Foster is Professor of Vision Systems at the University of Manchester and formerly Director of Research in the School of Electrical & Electronic Engineering. He has served as journal editor or editor in chief for over 30 years and has taught communication in science and engineering at undergraduate, postgraduate, and postdoctoral levels in the UK and elsewhere. He is a Fellow of the Institute of Physics, the Physiological Society, and the Optical Society of America. David is the author of A Concise Guide to Communication in Science and Engineering (OUP, 2017).

- Physics & Chemistry

- Science & Medicine

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

This describes the key points to decide an attractive journal title very clearly. The discussion is based on the thorough survey of recent publication and the presentation is very convincing with quantified statistical figures. I highly recommend this to anybody including the well-established academics.

Creating a good title is an art in itself – but it can be learned. The key techniques are summarized here very nicely: “Make it clear and remove the fluff” (my words). For more advice, go to David Foster’s excellent book, “A concise guide …” (see bottom of page). Good reading! One thing I would like to add: In my feeling, a short title implies that the paper is more fundamental, more general in its scope, and more accessible (my favourite title is “On Seeing Sidelong” by Gerry Lettvin, which is on peripheral vision). When, instead, the paper is rather narrow, I will be disappointed and think of it lowly. Conversely, I go to the longer titles when I search for something more specific. Of course that comes down – algorithmically so to say – to “an efficient title is one that maximizes the ratio of the information communicated to its length”. But it suggests that the optimum number of words is not independent of content and, rather, correlates with the content’s generality.

Comments are closed.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Table of Contents

Research Paper Title

Research Paper Title is the name or heading that summarizes the main theme or topic of a research paper . It serves as the first point of contact between the reader and the paper, providing an initial impression of the content, purpose, and scope of the research . A well-crafted research paper title should be concise, informative, and engaging, accurately reflecting the key elements of the study while also capturing the reader’s attention and interest. The title should be clear and easy to understand, and it should accurately convey the main focus and scope of the research paper.

Examples of Research Paper Title

Here are some Good Examples of Research Paper Title:

- “Investigating the Relationship Between Sleep Duration and Academic Performance Among College Students”

- “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment: A Systematic Review”

- “The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis”

- “Exploring the Effects of Social Support on Mental Health in Patients with Chronic Illness”

- “Assessing the Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial”

- “The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Behavior: A Systematic Review”

- “Investigating the Link Between Personality Traits and Leadership Effectiveness”

- “The Effect of Parental Incarceration on Child Development: A Longitudinal Study”

- “Exploring the Relationship Between Cultural Intelligence and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: A Meta-Analysis”

- “Assessing the Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Chronic Pain Management”.

- “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis”

- “The Impact of Climate Change on Global Crop Yields: A Longitudinal Study”

- “Exploring the Relationship between Parental Involvement and Academic Achievement in Elementary School Students”

- “The Ethics of Genetic Editing: A Review of Current Research and Implications for Society”

- “Understanding the Role of Gender in Leadership: A Comparative Study of Male and Female CEOs”

- “The Effect of Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial”

- “The Impacts of COVID-19 on Mental Health: A Cross-Cultural Comparison”

- “Assessing the Effectiveness of Online Learning Platforms: A Case Study of Coursera”

- “Exploring the Link between Employee Engagement and Organizational Performance”

- “The Effects of Income Inequality on Social Mobility: A Comparative Analysis of OECD Countries”

- “Exploring the Relationship Between Social Media Use and Mental Health in Adolescents”

- “The Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yield: A Case Study of Maize Production in Sub-Saharan Africa”

- “Examining the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis”

- “An Analysis of the Relationship Between Employee Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment”

- “Assessing the Impacts of Wilderness Areas on Local Economies: A Case Study of Yellowstone National Park”

- “The Role of Parental Involvement in Early Childhood Education: A Review of the Literature”

- “Investigating the Effects of Technology on Learning in Higher Education”

- “The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Opportunities and Challenges”

- “A Study of the Relationship Between Personality Traits and Leadership Styles in Business Organizations”.

How to choose Research Paper Title

Choosing a research paper title is an important step in the research process. A good title can attract readers and convey the essence of your research in a concise and clear manner. Here are some tips on how to choose a research paper title:

- Be clear and concise: A good title should convey the main idea of your research in a clear and concise manner. Avoid using jargon or technical language that may be confusing to readers.

- Use keywords: Including keywords in your title can help readers find your paper when searching for related topics. Use specific, descriptive terms that accurately describe your research.

- Be descriptive: A descriptive title can help readers understand what your research is about. Use adjectives and adverbs to convey the main ideas of your research.

- Consider the audience : Think about the audience for your paper and choose a title that will appeal to them. If your paper is aimed at a specialized audience, you may want to use technical terms or jargon in your title.

- Avoid being too general or too specific : A title that is too general may not convey the specific focus of your research, while a title that is too specific may not be of interest to a broader audience. Strive for a title that accurately reflects the focus of your research without being too narrow or too broad.

- Make it interesting : A title that is interesting or provocative can capture the attention of readers and draw them into your research. Use humor, wordplay, or other creative techniques to make your title stand out.

- Seek feedback: Ask colleagues or advisors for feedback on your title. They may be able to offer suggestions or identify potential problems that you hadn’t considered.

Purpose of Research Paper Title

The research paper title serves several important purposes, including:

- Identifying the subject matter : The title of a research paper should clearly and accurately identify the topic or subject matter that the paper addresses. This helps readers quickly understand what the paper is about.

- Catching the reader’s attention : A well-crafted title can grab the reader’s attention and make them interested in reading the paper. This is particularly important in academic settings where there may be many papers on the same topic.

- Providing context: The title can provide important context for the research paper by indicating the specific area of study, the research methods used, or the key findings.

- Communicating the scope of the paper: A good title can give readers an idea of the scope and depth of the research paper. This can help them decide if the paper is relevant to their interests or research.

- Indicating the research question or hypothesis : The title can often indicate the research question or hypothesis that the paper addresses, which can help readers understand the focus of the research and the main argument or conclusion of the paper.

Advantages of Research Paper Title

The title of a research paper is an important component that can have several advantages, including:

- Capturing the reader’s attention : A well-crafted research paper title can grab the reader’s attention and encourage them to read further. A captivating title can also increase the visibility of the paper and attract more readers.

- Providing a clear indication of the paper’s focus: A well-written research paper title should clearly convey the main focus and purpose of the study. This helps potential readers quickly determine whether the paper is relevant to their interests.

- Improving discoverability: A descriptive title that includes relevant keywords can improve the discoverability of the research paper in search engines and academic databases, making it easier for other researchers to find and cite.

- Enhancing credibility : A clear and concise title can enhance the credibility of the research and the author. A title that accurately reflects the content of the paper can increase the confidence readers have in the research findings.

- Facilitating communication: A well-written research paper title can facilitate communication among researchers, enabling them to quickly and easily identify relevant studies and engage in discussions related to the topic.

- Making the paper easier to remember : An engaging and memorable research paper title can help readers remember the paper and its findings. This can be especially important in fields where researchers are constantly inundated with new information and need to quickly recall important studies.

- Setting expectations: A good research paper title can set expectations for the reader and help them understand what the paper will cover. This can be especially important for readers who are unfamiliar with the topic or the research area.

- Guiding research: A well-crafted research paper title can also guide future research by highlighting gaps in the current literature or suggesting new areas for investigation.

- Demonstrating creativity: A creative research paper title can demonstrate the author’s creativity and originality, which can be appealing to readers and other researchers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Long research titles ‘have lower impact’

Lengthy titles of journal papers are a turn-off for fellow academics and lead to fewer citations, claims new analysis .

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

Picking a pithy title for your research paper could significantly improve its impact, new analysis suggests.

While many researchers might not worry too much about finding a memorable or eye-catching title for a new journal paper, a recently published study indicates that a longer and more convoluted title could seriously harm its chances of doing well.

According to an examination of the titles of around 155,000 journal articles submitted to the UK’s most recent research excellence framework ( REF ), papers with briefer titles tend to be cited more frequently.

Across 10 of the 11 units of assessment covering 36 disciplines in the 2014 REF, “citations significantly decline with title length”, according to the paper, “An analysis of the titles of papers submitted to the UK REF in 2014: authors, disciplines, and stylistic details”, by John Hudson, professor of economics at the University of Bath , in a recent edition of the journal Scientometrics .

That effect was more marked in certain subjects, including clinical medicine, biology and physics, and less so in disciplines such as computer science and economics, according to the study.

“A longer title generally means a paper is less likely to receive citations,” Professor Hudson told Times Higher Education .

Using a question mark in a journal paper’s title reduces the number of citations it received, he added.

However, using a colon tended to improve the citations received by a paper, Professor Hudson said.

“With a colon you have to divide up the title into two parts, so you have two messages for readers,” he said, noting that a dual title could broaden the appeal of a paper.

Overall, the discipline with the longest journal titles on average was public health, whose titles averaged 117 characters including spaces, followed by clinical medicine (113) and agriculture (110). The shortest titles tended to come in social sciences and humanities, such as economics (66 characters), Classics (69) and English language (74).

Political scientists and law academics were most likely to use question marks in their journal titles (almost a fifth of papers in these disciplines used them) but these were used by less than 1 per cent of papers submitted in maths and electrical engineering.

The average number of authors per paper differed significantly between disciplines ; physics papers had 131 co-authors on average, but for history, philosophy and theology the average was 1.1 in each case, the study found.

Consistent with previous studies, those papers with multiple authorship tended to receive higher citation rates, but numerous authors also led to longer titles, Professor Hudson said.

Those longer titles may be the result of negotiation between numerous authors, he suggested.

“If they are compromising on titles, are they compromising on other aspects of research?” Professor Hudson said.

Disciplinary variation in the number of authors per paper also highlighted how it had been much more difficult for academics in certain disciplines to generate the four pieces of work required for the 2014 REF – a factor policymakers might wish to consider when finalising future research audits, he added.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

Twitter taunts over REF omission rile professor

Politics scholar angered by what he claims was ‘ruthless’ attempt to discredit him by citing non-inclusion in UK’s research excellence framework

Could refusal to reveal graduate premium lead to a fraud charge?

David Palfreyman considers how secretiveness about the benefits a graduate might expect might fall foul of trading regulations

Can the research excellence framework run on metrics?

An Elsevier analysis explores the viability of a ‘smarter and cheaper’ model

‘Use of AI in research widespread but distrust still high’ – OUP

Poll finds most researchers are using AI but only a tiny number trust technology companies on data privacy

Gender-critical scholars claim discrimination over BMJ rejections

Researchers say emails suggest disapproval of social media posts on transgender issues contributed to rejections

Sight loss should not mean a fading academic career

With the right support, academics with visual impairments are prospering, but barriers to true inclusivity remain, says Kate Armond, while a lecturer reflects on how practice on reasonable adjustments can fall short of policy

Emeritus professors ‘excluded’ from UK open access deal

Policy expert told he would have to cover publication fee himself post-retirement alleges ‘blatant age discrimination’

Featured jobs

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Make a Research Paper Title with Examples

What is a research paper title and why does it matter?

A research paper title summarizes the aim and purpose of your research study. Making a title for your research is one of the most important decisions when writing an article to publish in journals. The research title is the first thing that journal editors and reviewers see when they look at your paper and the only piece of information that fellow researchers will see in a database or search engine query. Good titles that are concise and contain all the relevant terms have been shown to increase citation counts and Altmetric scores .

Therefore, when you title research work, make sure it captures all of the relevant aspects of your study, including the specific topic and problem being investigated. It also should present these elements in a way that is accessible and will captivate readers. Follow these steps to learn how to make a good research title for your work.

How to Make a Research Paper Title in 5 Steps

You might wonder how you are supposed to pick a title from all the content that your manuscript contains—how are you supposed to choose? What will make your research paper title come up in search engines and what will make the people in your field read it?

In a nutshell, your research title should accurately capture what you have done, it should sound interesting to the people who work on the same or a similar topic, and it should contain the important title keywords that other researchers use when looking for literature in databases. To make the title writing process as simple as possible, we have broken it down into 5 simple steps.

Step 1: Answer some key questions about your research paper

What does your paper seek to answer and what does it accomplish? Try to answer these questions as briefly as possible. You can create these questions by going through each section of your paper and finding the MOST relevant information to make a research title.

Step 2: Identify research study keywords

Now that you have answers to your research questions, find the most important parts of these responses and make these your study keywords. Note that you should only choose the most important terms for your keywords–journals usually request anywhere from 3 to 8 keywords maximum.

Step 3: Research title writing: use these keywords

“We employed a case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years to assess how waiting list volume affects the outcomes of liver transplantation in patients; results indicate a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and negative prognosis after the transplant procedure.”

The sentence above is clearly much too long for a research paper title. This is why you will trim and polish your title in the next two steps.

Step 4: Create a working research paper title

To create a working title, remove elements that make it a complete “sentence” but keep everything that is important to what the study is about. Delete all unnecessary and redundant words that are not central to the study or that researchers would most likely not use in a database search.

“ We employed a case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years to assess how the waiting list volume affects the outcome of liver transplantation in patients ; results indicate a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis after transplant procedure ”

Now shift some words around for proper syntax and rephrase it a bit to shorten the length and make it leaner and more natural. What you are left with is:

“A case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcome of transplantation and showing a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis” (Word Count: 38)

This text is getting closer to what we want in a research title, which is just the most important information. But note that the word count for this working title is still 38 words, whereas the average length of published journal article titles is 16 words or fewer. Therefore, we should eliminate some words and phrases that are not essential to this title.

Step 5: Remove any nonessential words and phrases from your title

Because the number of patients studied and the exact outcome are not the most essential parts of this paper, remove these elements first:

“A case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcomes of transplantation and showing a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis” (Word Count: 19)

In addition, the methods used in a study are not usually the most searched-for keywords in databases and represent additional details that you may want to remove to make your title leaner. So what is left is:

“Assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcome and prognosis in liver transplantation patients” (Word Count: 15)

In this final version of the title, one can immediately recognize the subject and what objectives the study aims to achieve. Note that the most important terms appear at the beginning and end of the title: “Assessing,” which is the main action of the study, is placed at the beginning; and “liver transplantation patients,” the specific subject of the study, is placed at the end.

This will aid significantly in your research paper title being found in search engines and database queries, which means that a lot more researchers will be able to locate your article once it is published. In fact, a 2014 review of more than 150,000 papers submitted to the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF) database found the style of a paper’s title impacted the number of citations it would typically receive. In most disciplines, articles with shorter, more concise titles yielded more citations.

Adding a Research Paper Subtitle

If your title might require a subtitle to provide more immediate details about your methodology or sample, you can do this by adding this information after a colon:

“ : a case study of US adult patients ages 20-25”

If we abide strictly by our word count rule this may not be necessary or recommended. But every journal has its own standard formatting and style guidelines for research paper titles, so it is a good idea to be aware of the specific journal author instructions , not just when you write the manuscript but also to decide how to create a good title for it.

Research Paper Title Examples

The title examples in the following table illustrate how a title can be interesting but incomplete, complete by uninteresting, complete and interesting but too informal in tone, or some other combination of these. A good research paper title should meet all the requirements in the four columns below.

Tips on Formulating a Good Research Paper Title

In addition to the steps given above, there are a few other important things you want to keep in mind when it comes to how to write a research paper title, regarding formatting, word count, and content:

- Write the title after you’ve written your paper and abstract

- Include all of the essential terms in your paper

- Keep it short and to the point (~16 words or fewer)

- Avoid unnecessary jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords that capture the content of your paper

- Never include a period at the end—your title is NOT a sentence

Research Paper Writing Resources

We hope this article has been helpful in teaching you how to craft your research paper title. But you might still want to dig deeper into different journal title formats and categories that might be more suitable for specific article types or need help with writing a cover letter for your manuscript submission.

In addition to getting English proofreading services , including paper editing services , before submission to journals, be sure to visit our academic resources papers. Here you can find dozens of articles on manuscript writing, from drafting an outline to finding a target journal to submit to.

Titles in research articles and doctoral dissertations: cross-disciplinary and cross-generic perspectives

- Published: 29 February 2024

- Volume 129 , pages 2285–2307, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Jialiang Hao ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0006-5980-4451 1 , 2

219 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

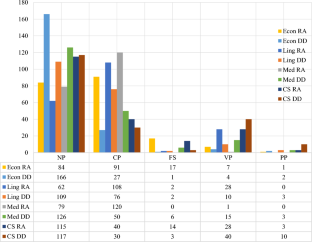

Although titles are often regarded as a minimal aspect of academic discourse, they play a crucial role in knowledge construction across various disciplines and genres. This study examined four features of titles, namely, title length, punctuation usage, structure, and content information, with a corpus comprising 1600 titles of research articles (RAs) from top journals and doctoral dissertations (DDs) from prestigious universities across four soft and hard science disciplines. The results confirm disciplinary and generic variations within the titles of these two critical academic genres. Titles in linguistics and medicine are generally longer than those in economics and computer science (CS). Slightly more titles in hard disciplines contain punctuation than do those in soft disciplines. The average title length of RAs is longer than that of DDs, and more RA titles than DD titles have punctuation in all four disciplines, with no apparent difference in the punctuation variety across the two genres, except for CS titles. Nominal group titles and compound titles are the two most common types, and prepositional phrase titles are the least common in all four disciplines and genres. The content information in titles is different in each discipline and genre. These findings are partially congruent with those of previous studies, indicating the significance of further investigating titles across disciplines and genres.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Balancing AI and academic integrity: what are the positions of academic publishers and universities?

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

This paper follows US conventions.

https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php

The impact factor is from the 2022 Journal Citation Reports .

https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2022

https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/74/2014/09/guidelines-for-the-PhD-dissertation.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the american psychological association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

Google Scholar

Anthony, L. (2001). Characteristic features of research article titles in computer science. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44 (3), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1109/47.946464

Article Google Scholar

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Kashfi, K., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The principles of biomedical scientific writing: Title. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 17 , e98326. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.98326

Ball, R. (2009). Scholarly communication in transition: The use of question marks in the titles of scientific articles in medicine, life sciences and physics 1966–2005. Scientometrics, 79 (3), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1984-5

Berkenkotter, C., & Huckin, T. N. (1995). News value in scientific journal articles. In C. Berkenkotter & T. N. Huckin (Eds.), Genre knowledge in disciplinary communication: Cognition, culture, power (pp. 27–44). Routledge.

Bramoullé, Y., & Ductor, L. (2018). Title length. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 150 , 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.01.014

Braticevic, M. N., Babic, I., Abramovic, I., Jokic, A., & Horvat, M. (2020). Title does matter: A cross-sectional study of 30 journals in the medical laboratory technology category. Biochemia Medica, 30 (1), 128–133. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2020.010708

Bunton, D. (2002). Generic moves in PhD theses introductions. In J. Flowerdew (Ed.), Academic discourse (pp. 57–75). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315838069

Chapter Google Scholar

Chen, X., & Liu, H. (2023). Academic “click bait”: A diachronic investigation into the use of rhetorical part in pragmatics research article titles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 66 , 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101306

Cheng, S. W., Kuo, C.-W., & Kuo, C.-H. (2012). Research article titles in applied linguistics. Journal of Academic Language and Learning, 6 (1), A1–A14.

Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: looks matter! Indian Pediatrics, 53 (3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-016-0827-y

Diao, J. (2021). A lexical and syntactic study of research article titles in library science and scientometrics. Scientometrics, 126 , 6041–6058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04018-6

El-Dakhs, D. A. S. (2018). Why are abstracts in PhD theses and research articles different? A genre-specific perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 36 , 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2018.09.005

Finlay, C. S., Sugimoto, C. R., Li, D., & Russell, T. G. (2012). LIS dissertation titles and abstracts (1930–2009): Where have all the librar* gone? The Library Quarterly, 82 (1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1086/662945

Fox, C. W., & Burns, C. S. (2015). The relationship between manuscript title structure and success: Editorial decisions and citation performance for an ecological journal. Ecology and Evolution, 5 , 1970–1980. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1480

Gesuato, S. (2008). Encoding of information in titles: Academic practices across four genres in linguistics. In C. Taylor (Ed.), Ecolingua. The role of E-corpora in translation and language learning (pp. 127–157). EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste.

Gnewuch, M., & Wohlrabe, K. (2017). Title characteristics and citations in economics. Scientometrics, 110 (3), 1573–1578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2216-7

Goodman, R. A., Thacker, S. B., & Siegel, P. Z. (2001). What’s in a title? A descriptive study of article titles in peer-reviewed medical journals. Science Editor, 24 (3), 75–78.

Guo, S., Zhang, G., Ju, Q., Chen, Y., Chen, Q., & Li, L. (2015). The evolution of conceptual diversity in economics titles from 1890 to 2012. Scientometrics, 102 , 2073–2088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1501-6

Habibzadeh, F., & Yadollahie, M. (2010). Are shorter article titles more attractive for citations? Cross-sectional study of 22 scientific journals. Croatian Medical Journal, 51 (2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2010.51.165

Haggan, M. (2004). Research paper titles in literature, linguistics and science: Dimensions of attractions. Journal of Pragmatics, 36 , 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(03)00090-0

Hallock, R. M., & Dillner, K. M. (2016). Should title lengths really adhere to the American Psychological Association’s twelve word limit? American Psychologist, 71 (3), 240–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040226

Hartley, J. (2005). To attract or to inform: What are titles for? Journal Technical Writing & Communication, 35 , 203–213. https://doi.org/10.2190/NV6E-FN3N-7NGN-TWQT

Hartley, J. (2007a). Planning that title: Practices and preferences for titles with colons in academic articles. Library & Information Science Research, 29 (4), 553–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.05.002

Hartley, J. (2007b). Colonic titles! The Write Stuff, 16 (4), 147–149.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13 , 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2004.02.001

Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2005). Hooking the reader: A corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. English for Specific Purposes, 24 (2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2004.02.002

Hyland, K., & Zou, H. (2022). Titles in research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 56 , 101094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101094

Jacques, T. S., & Sebire, N. J. (2009). The impact of article titles on citation hits: An analysis of general and specialist medical journals. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Short Reports, 1 (2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1258/shorts.2009.100020

Jalilifar, A. (2010). Writing titles in applied linguistics: A comparative study of theses and research articles. Taiwan International ESP Journal, 2 (1), 27–52.

Jalilifar, A., Hayati, A., & Mayahi, N. (2010). An exploration of generic tendencies in Applied Linguistics titles. Journal of Faculty of Letters and Humanities, 5 (16), 35–57.

Jamali, H. R., & Nikzad, M. (2011). Article title type and its relation with the number of downloads and citations. Scientometrics, 88 (2), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0412-z

Jiang, F. K., & Hyland, K. (2023). Titles in research articles: Changes across time and discipline. Learned Publishing, 36 , 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1498

Jiang, G. K., & Jiang, Y. (2023). More diversity, more complexity, but more flexibility: Research article titles in TESOL Quarterly , 1967–2022. Scientometrics, 128 , 3959–3980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04738-x

Kawase, T. (2015). Metadiscourse in the introductions of PhD theses and research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20 , 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.08.006

Kawase, T. (2018). Rhetorical structure of the introductions of applied linguistics PhD theses. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 31 , 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2017.12.005

Kerans, M. E., Marshall, J., Murray, A., & Sabaté, S. (2020). Research article title content and form in high-ranked international clinical medicine journals. English for Specific Purposes, 60 , 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.06.001

Kerans, M. E., Murray, A., & Sabaté, S. (2016). Content and phrasing in titles of original research and review articles in 2015: Range of practice in four clinical journals. Publications, 4 (2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications4020011

Koutsantoni, D. (2006). Rhetorical strategies in engineering research articles and research theses: Advanced academic literacy and relations of power. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 5 (1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2005.11.002

Lewison, G., & Hartley, J. (2005). What’s in a title? Numbers of words and the presence of colons. Scientometrics, 63 (2), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-005-0216-0

Li, Z., & Xu, J. (2019). The evolution of research article titles: The case of Journal of Pragmatics 1978–2018. Scientometrics, 121 , 1619–1634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03244-3

Méndez, D. I., ÁngelesAlcaraz, M., & Salager-Meyer, F. (2014). Titles in English-medium Astrophysics research articles. Scientometrics, 98 (3), 2331–2351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1174-6

Milojevic, S. (2017). The length and semantic structure of article titles—evolving disciplinary practices and correlations with impact. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analysis, 2 , 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2017.00002

Morales, O. A., Perdomo, B., Cassany, D., Tovar, R. M., & Izarra, É. (2020). Linguistic structures and functions of thesis and dissertation titles in dentistry. Lebende Sprachen, 65 (1), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2020-0003

Moslehi, S., & Kafipour, R. (2022). Syntactic structure and rhetorical combinations of Iranian English research article titles in medicine and applied linguistics: A cross-disciplinary study. Frontiers in Education, 7 , 935274. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.935274

Nagano, R. L. (2015). Research article titles and disciplinary conventions: A corpus study of eight disciplines. Journal of Academic Writing, 5 , 133–144. https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v5i1.168

Nair, L. B., & Gibbert, M. (2016). What makes a “good” title and (how) does it matter for citations? A review and general model of article title attributes in management science. Scientometrics, 107 (3), 1331–1359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1937-y

Nieuwenhuis, J. (2023). Another article titled “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” or, the mass production of academic research titles. The Information Society, 39 (2), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2022.2152916

Paiva, C., Lima, J., & Paiva, B. (2012). Articles with short titles describing the results are cited more often. Clinics, 67 (5), 509–513. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2012(05)17

Paltridge, B. (2002). Thesis and dissertation writing: An examination of published advice and actual practice. English for Specific Purposes, 21 (2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(00)00025-9

Paré, A. (2019). Re-writing the doctorate: New contexts, identities, and genres. Journal of Second Language Writing, 43 , 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.08.004

Paré, A., Starke-Meyerring, D., & McAlpine, L. (2009). The dissertation as multi-genre: Many readers, many readings. In C. Bazerman, A. Bonini, & D. Figueiredo (Eds.), Genre in a changing world (pp. 179–193). The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press.

Pearson, W. S. (2020). Research article titles in written feedback on English as a second language writing. Scientometrics, 123 , 997–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03388-7

Pearson, W. S. (2021). Quoted speech in linguistics research article titles: Patterns of use and effects on citations. Scientometrics, 126 , 3421–3442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03827-5

Qiu, X., & Ma, X. (2019). Disciplinary enculturation and authorial stance: comparison of stance features among master’s dissertations, doctoral theses, and research articles. Ibérica, 38 , 327–348.

Sahragard, R., & Meihami, H. (2016). A diachronic study on the information provided by the research titles of applied linguistics journals. Scientometrics, 108 , 1315–1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2049-4

Salager-Meyer, F., Alcaraz-Ariza, M. A., & Briceño, M. L. (2013). Titling and authorship practices in medical case reports: A diachronic study (1840–2009). Communication & Medicine, 10 (1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.v10i1.63

Soler, V. (2007). Writing titles in science: An exploratory study. English for Specific Purposes, 26 (1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.001

Soler, V. (2011). Comparative and contrastive observations on scientific titles written in English and Spanish. English for Specific Purposes, 30 (2), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2010.09.002

Soler, V. (2018). Estudio exploratorio de títulos de tesis doctorales redactados en lengua Española [Exploratory study of Ph.D. thesis titles written in Spanish]. Lebende Sprachen, 63 (2), 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2018-0022

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research setting . Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press . https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524827

Swales, J., & Feak, C. B. (2012). Academic writing for graduate students . Ann Arbor, MI, The University of Michigan Press.

Book Google Scholar

Taş, E. E. I. (2008). A corpus-based analysis of genre-specific discourse of research: The PhD thesis and the research article in ELT. Doctorate thesis at Middle East Technical University (Turkey) . http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.633.4476&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Thompson, P. (2005). Points of focus and position: Intertextual reference in PhD theses. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4 (4), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2005.07.006

Thompson, P. (2013). Thesis and dissertation writing. In B. Paltridge & S. Starfield (Eds.), The handbook of English for specific purposes (pp. 283–299). West Essex.

Wang, Y., & Bai, Y. (2007). A corpus-based syntactic study of medical research article titles. System, 35 , 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.01.005

Whissell, C. (2012). The trend toward more attractive and informative titles: American psychologist 1946–2010. Psychological Reports, 110 (2), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.2466/17.28.pr0.110.2.427-444

Whissell, C. (2013). Titles in highly ranked multidisciplinary psychology journals 1966–2011: More words and punctuation marks allow for the communication of more information. Psychological Reports, 113 (3), 969–986. https://doi.org/10.2466/28.17.PR0.113x30z5

Xiang, X., & Li, J. (2020). A diachronic comparative study of research article titles in linguistics and literature journals. Scientometrics, 122 , 847–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03329-z

Xiao, W., & Sun, S. (2020). Dynamic lexical features of PhD theses across disciplines: A text mining approach. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 27 (2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1531618

Xie, S. (2020). English research article titles: Cultural and disciplinary perspectives. SAGE Open, 10 (2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020933614

Yang, W. (2019). A diachronic keyword analysis in research article titles and cited article titles in applied linguistics from 1990 to 2016. English Text Construction, 12 (1), 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1075/etc.00019.yan

Yitzhaki, M. (2002). Relation of the title length of a journal article to the length of the article. Scientometrics, 54 , 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016038617639

Zhou, H., & Jiang, F. K. (2023). “The study has clear limitations”: Presentation of limitations in conclusion sections of PhD dissertations and research articles in applied linguistics. English for Specific Purposes, 71 , 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2023.02.001

Download references

Acknowledgements

The researcher thanks the handling editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which significantly contributed to enhancing the quality of the manuscript.

This research was supported and funded by the Scientific Research Program Funded by Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (Program No. 23JK0100).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Xi’an International Studies University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

Jialiang Hao

Weinan Normal University, Weinan, Shaanxi, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jialiang Hao .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hao, J. Titles in research articles and doctoral dissertations: cross-disciplinary and cross-generic perspectives. Scientometrics 129 , 2285–2307 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04941-4

Download citation

Received : 10 July 2023

Accepted : 09 January 2024

Published : 29 February 2024

Issue Date : April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04941-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research articles

- Doctoral dissertations

- Disciplines

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

How Long Should a Research Paper Be? Data from 61,519 Examples

I analyzed a random sample of 61,519 full-text research papers, uploaded to PubMed Central between the years 2016 and 2021, in order to answer the questions:

What is the typical overall length of a research paper? and how long should each section be?

I used the BioC API to download the data (see the References section below).

Here’s a summary of the key findings

1- The median length of a research paper is 4,133 words (equivalent to 166 sentences or 34 paragraphs), excluding the abstract and references, with 90% of papers being between 2,023 and 8,284 words.

2- A typical article is divided in the following way:

- Introduction section: 14.6% of the total word count.

- Methods section: 29.7% of the total word count.

- Results section: 26.2% of the total word count.

- Discussion section: 29.4% of the total word count.

Notice that the Materials and methods is the longest section of a professionally written article. So always write this section in enough depth to provide the readers with the necessary details that allow them to replicate your study if they wanted to without requiring further information.

Overall length of a research paper

Let’s start by looking at the maximum word count allowed in some of the well-known journals. Note that the numbers reported in this table include the Abstract , Figure legends and References unless otherwise specified:

[1] excluding figure legends [2] excluding references

⚠ Note A review paper is either a systematic review or a meta-analysis, and an original research paper refers to either an observational or an experimental study conducted by the authors themselves.

Notice the large variability between these journals: The maximum number of words allowed ranges between 3,000 and 9,000 words.

Next, let’s look at our data.

Here’s a table that describes the length of a research paper in our sample:

90% of research papers have a word count between 2,023 and 8,284. So it will be a little weird to see a word count outside of this range.

Our data also agree that a typical review paper is a little bit longer than a typical original research paper but not by much (3,858 vs 3,708 words).

Length of each section in a research article

The median article with an IMRaD structure (i.e. contains the following sections: Introduction , Methods , Results and Discussion ) is in general characterized by a short 553 words introduction. And the methods, results and discussion sections are about twice the size of the introduction:

For more information, see:

- How Long Should a Research Title Be? Data from 104,161 Examples

- How Long Should the Abstract Be? Data 61,429 from Examples

- How Long Should the Introduction of a Research Paper Be? Data from 61,518 Examples

- How Long Should the Methods Section Be? Data from 61,514 Examples

- How Long Should the Results Section Be? Data from 61,458 Examples

- How Long Should the Discussion Section Be? Data from 61,517 Examples

- Length of a Conclusion Section: Analysis of 47,810 Examples

- Comeau DC, Wei CH, Islamaj Doğan R, and Lu Z. PMC text mining subset in BioC: about 3 million full text articles and growing, Bioinformatics , btz070, 2019.

- Research guides

Writing an Educational Research Paper

Research paper sections, customary parts of an education research paper.

There is no one right style or manner for writing an education paper. Content aside, the writing style and presentation of papers in different educational fields vary greatly. Nevertheless, certain parts are common to most papers, for example:

Title/Cover Page

Contains the paper's title, the author's name, address, phone number, e-mail, and the day's date.

Not every education paper requires an abstract. However, for longer, more complex papers abstracts are particularly useful. Often only 100 to 300 words, the abstract generally provides a broad overview and is never more than a page. It describes the essence, the main theme of the paper. It includes the research question posed, its significance, the methodology, and the main results or findings. Footnotes or cited works are never listed in an abstract. Remember to take great care in composing the abstract. It's the first part of the paper the instructor reads. It must impress with a strong content, good style, and general aesthetic appeal. Never write it hastily or carelessly.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

A good introduction states the main research problem and thesis argument. What precisely are you studying and why is it important? How original is it? Will it fill a gap in other studies? Never provide a lengthy justification for your topic before it has been explicitly stated.

Limitations of Study

Indicate as soon as possible what you intend to do, and what you are not going to attempt. You may limit the scope of your paper by any number of factors, for example, time, personnel, gender, age, geographic location, nationality, and so on.

Methodology

Discuss your research methodology. Did you employ qualitative or quantitative research methods? Did you administer a questionnaire or interview people? Any field research conducted? How did you collect data? Did you utilize other libraries or archives? And so on.

Literature Review

The research process uncovers what other writers have written about your topic. Your education paper should include a discussion or review of what is known about the subject and how that knowledge was acquired. Once you provide the general and specific context of the existing knowledge, then you yourself can build on others' research. The guide Writing a Literature Review will be helpful here.

Main Body of Paper/Argument

This is generally the longest part of the paper. It's where the author supports the thesis and builds the argument. It contains most of the citations and analysis. This section should focus on a rational development of the thesis with clear reasoning and solid argumentation at all points. A clear focus, avoiding meaningless digressions, provides the essential unity that characterizes a strong education paper.

After spending a great deal of time and energy introducing and arguing the points in the main body of the paper, the conclusion brings everything together and underscores what it all means. A stimulating and informative conclusion leaves the reader informed and well-satisfied. A conclusion that makes sense, when read independently from the rest of the paper, will win praise.

Works Cited/Bibliography

See the Citation guide .

Education research papers often contain one or more appendices. An appendix contains material that is appropriate for enlarging the reader's understanding, but that does not fit very well into the main body of the paper. Such material might include tables, charts, summaries, questionnaires, interview questions, lengthy statistics, maps, pictures, photographs, lists of terms, glossaries, survey instruments, letters, copies of historical documents, and many other types of supplementary material. A paper may have several appendices. They are usually placed after the main body of the paper but before the bibliography or works cited section. They are usually designated by such headings as Appendix A, Appendix B, and so on.

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 6:23 PM

- Subjects: Education

- Tags: education , education_paper , education_research_paper

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.6(21); 2016 Nov

Citations increase with manuscript length, author number, and references cited in ecology journals

Charles w. fox.

1 Department of Entomology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA

C. E. Timothy Paine

2 Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK

Boris Sauterey

Most top impact factor ecology journals indicate a preference or requirement for short manuscripts; some state clearly defined word limits, whereas others indicate a preference for more concise papers. Yet evidence from a variety of academic fields indicates that within journals longer papers are both more positively reviewed by referees and more highly cited. We examine the relationship between citations received and manuscript length, number of authors, and number of references cited for papers published in 32 ecology journals between 2009 and 2012. We find that longer papers, those with more authors, and those that cite more references are cited more. Although paper length, author count, and references cited all positively covary, an increase in each independently predicts an increase in citations received, with estimated relationships positive for all the journals we examined. That all three variables covary positively with citations suggests that papers presenting more and a greater diversity of data and ideas are more impactful. We suggest that the imposition of arbitrary manuscript length limits discourages the publication of more impactful studies. We propose that journals abolish arbitrary word or page limits, avoid declining papers (or requiring shortening) on the basis of length alone (irrespective of content), and adopt the philosophy that papers should be as long as they need to be.

1. Introduction

Scholarly papers are the primary medium through which scientific researchers communicate ideas and research outcomes to their peers. The number of papers published in the scholarly scientific literature has been increasing exponentially, at a rate of approximately 3% per year, since 1980 (Bornmann & Mutz, 2015 ). This growth rate has been slightly higher in ecology and evolution than in other biological disciplines (Pautasso, 2012 ). At many journals, submissions are growing at a faster pace than are the page allocations necessary to publish those submissions (Fox & Burns, 2015 ). This disparity drives down acceptance rates (Fox & Burns, 2015 ; Fox, Burns, & Meyer, 2016 ; Wardle, 2012 ), but also puts pressure on editors to allocate fewer pages to each published manuscript so that journals can publish more papers while staying within contractual page budgets.

Most top impact factor ecology journals indicate a preference or requirement for short manuscripts (25 of the 32 journals in Appendix Table A1 ). Some state clearly defined word limits, generally requiring manuscripts to contain fewer than 6000–8000 words, although which elements of the paper this includes (e.g., including references or just the main text), and the degree to which these are guidelines versus absolute limits, varies among journals. Other journals have less specific word or page limits but nonetheless emphasize that shorter papers are preferable. Ecology , for example, warns that “many manuscripts submitted to Ecology are rejected without review for being overly long” and Functional Ecology notes that “preference is given to shorter, more concise papers” (Appendix Table A1 ). Also, because evaluations of researcher performance commonly consider publication counts more than publication length when quantifying researcher impact, authors may choose to split complex studies into smaller publication units to increase their number of publications. Journals and authors thus commonly prefer shorter papers. How does this influence the impact of papers?

The perspective that short manuscripts have greater impact is likely driven by the observation that the highest profile journals, such as Science and Nature for general science, or Ecology Letters within ecology, publish relatively short articles. Evidence also suggests that social media attention is greater for shorter paper (Haustein, Costas, & Larivière, 2015 ). However, few research papers receive attention on social media (in contrast to editorials and news items; Haustein et al., 2015 ), especially if published outside the major multidisciplinary journals (Zahedi, Costas, & Wouters, 2014 ), and social media attention (except for Mendeley) generally only weakly correlates with citations received in the scholarly literature (Haustein et al., 2014 ). Evidence in a variety of academic fields indicates that, within journals, longer papers are both more positively reviewed by referees (Card & DellaVigna, 2012 ) and more highly cited (Ball, 2008 ; Falagas, Zarkali, Karageorgopoulos, Bardakas, & Mavros, 2013 ; Haustein et al., 2015 ; Leimu & Koricheva, 2005b ; Perneger, 2004 ; Robson & Mousquès, 2014 ; Schwarz & Kennicutt, 2004 ; Vanclay, 2013 ; Xiao, Yuan, & Wu, 2009 ). Many research projects produce complex data that does not lend itself to concise presentation of a single or simple message. It is thus likely that longer papers contain more ideas and a greater diversity of results, which provides more opportunity for citation (Leimu & Koricheva, 2005b ), and thus have more diverse and possibly greater impact on the scientific community.

The objective of this study was to examine the relationships between citations received, a proxy for academic impact, and manuscript length at major ecology journals. However, manuscript length covaries positively with a variety of other features that have been shown to predict citation frequency. In particular, papers with more authors are commonly better cited (Leimu & Koricheva, 2005a , b ; Schwarz & Kennicutt, 2004 ; Borsuk, Budden, Leimu, Aarssen, & Lortie, 2009 ; Webster, Jonason, & Schember, 2009 ; Gazni & Didegah, 2011 ; Didegah & Thelwall, 2013 ; Robson & Mousquès, 2014 ; Haustein et al., 2015 ; Larivière, Gingras, Sugimoto, & Tsou, 2014 ; but see Stremersch, Verniers, & Verhoef, 2007 ; Rao, 2011 ). It is possible that this occurs because more authors on a paper leads to more self‐citation and/or citation by colleagues and collaborators, but it is more likely that collaborative projects present more diverse data and ideas and are of higher quality (Katz & Martin, 1997 ). Also, longer papers tend to cite more references (Abt & Garfield, 2002 ) and papers that cite more references tend to be better cited (Webster et al., 2009 ; Mingers & Xu, 2010 ; Rao, 2011 ; Bornmann, Schier, Marx, & Daniel, 2012 ; Robson & Mousquès, 2014 ; Ale Ebrahim, Ebrahimian, Mousavi, & Tahriri, 2015 ; Haustein et al., 2015 ; review of earlier work in Alimohammadi & Sajjadi, 2009 ). There is even evidence that papers with longer abstracts are better cited (Weinberger, Evans, & Allesina, 2015 ), possibly because more data‐ or idea‐rich papers have longer abstracts, or just because longer abstracts touch on more points and are thus more likely attract reader interest. These various relationships make it difficult to determine causality in analyses of how manuscript length predicts citation frequency.

We examine the relationships between citations received and manuscript length, number of authors, and number of references cited for papers published in 32 ecology journals between 2009 and 2012 (inclusive). We find that, within journals, longer papers, papers with more authors, and papers with more references are better cited. We argue that the preference by journal editors for short papers (and short abstracts), and journal‐imposed limits on manuscript length, are likely to reduce the scientific impact of published articles.

2.1. Dataset

Citation data were retrieved from Web of Science for 32 ecology journals between 29 September and 2 October 2014 (Monday–Thursday). Extraction of citation data was completed before the weekly update of the Web of Science database that occurred on 2 October, and thus data are from the same Web of Science update for all journals. Citation counts are an imperfect metric of manuscript impact. They do not capture influence on practitioners (Stremersch et al., 2007 ) and can covary with many variables unrelated to manuscript quality or influence, such as author reputation (Mingers & Xu, 2010 ). However, citations covary with other measures of scientific influence (Mingers & Xu, 2010 ) and article downloads (Perneger, 2004 ; although this relationship varies among journals and disciplines, Bollen, Van de Sompel, Smith, & Luce, 2005 ), and they can be objectively quantified.

The journals were chosen from the list of all journals that received an impact factor and were categorized as ecology journals by Thomson Reuters in 2013. We included journals based on the following criteria. The journal must have (i) published at least 400 research articles in the 4‐year window of this study, (ii) had a 2013 two‐year impact factor of 2.5 or greater (as low impact factors indicate that many articles go uncited), and (iii) publish primarily research papers (e.g., we exclude the Annual Review and Trends series). Limiting our analyses to journals with an impact factor >2.5 could introduce bias into measures of the relationship between manuscript length and citations because it excludes a large number of low citation papers. However, journals with higher impact factors are those under the most pressure to publish shorter papers (because they receive far more submissions than they can publish). Also, relationships described below (in 3 ) are consistent across all journals in our dataset, including those with higher and lower impact factors. Nonetheless, we must be cautious extrapolating from our analysis of journals with higher impact factors to the broader ecological literature. We also excluded journals that publish primarily in a language other than English (e.g., Interciencia ), those with a primarily methodological focus (e.g., Molecular Ecology Resources ) and those with a primary focus in another discipline than ecology (e.g., Ecological Engineering , Ecological Economics and Ecology and Society ). These criteria yielded 26,539 articles.

We include in analyses all regular papers (those identified as “articles” in Web of Science) published between 2009 and 2012 (inclusive); we exclude all papers not tagged as an “article,” which includes reviews, editorials, and a variety of other nonstandard manuscript types. We chose these years, 2009–2012, rather than older publication years (which had more time to accumulate citations), so that our analyses to reflect the current state of ecology publishing. We also exclude all papers that were categorized as an “article” but that cited no references, had titles of fewer than three words, were fewer than two pages long, had more than 200 references, or had abstracts of fewer than 10 words. These were papers likely to be miscategorized by Web of Science. The final dataset includes 26,088 articles.

2.2. Analyses

As an initial exploration of the data, we performed an ANCOVA predicting the number of citations an article received as a function of its page length and the journal in which it was published. These factors were allowed to interact to determine the degree to which the citation–page length relationship varied among journals. We also included year of publication, as articles published in early 2009 had 5.8 years to accumulate citations, whereas those published in late 2012 had only 1.8 years to do so. We note that citations obtained by a manuscript soon after publication are predictive of the citations it will obtain later (Adams, 2005 ). Thus, the form of the ANCOVA was Number_of_citations ~ Year + Page_length * Journal.

Page length, however, covaries with other factors, including the number of authors and number of references, that may also influence an article's impact on the scientific community (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). Therefore, we next built a mixed‐effect model to assess the relative importance of page length, the number of authors, and the number of references on the number of citations received by an article, together with all their interactions. Year and journal were included as random effects. We also allowed for random variation in the three main effects among journals. Thus, the form of the mixed‐effect model was Number_of_citations ~ Number_of_references * Number_of_pages * Author_count + (1|Year) + (Number_of_pages + Number_of_references + Author_count|Journal), where the brackets around the last two terms indicate that they are random effects, with the grouping factors to the right of the vertical bar. Note that it was not possible to include “page count excluding references” in our models because we only have access to the total page count and number of references, and not how many pages are allocated to each manuscript's reference section. All fixed effects were standardized to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one to allow comparisons of their relative contributions to the number of citations received. In both analyses, the number of citations (+1), the number of pages, and the author count were log‐transformed to reduce heteroscedasticity. Year was included as a factor with four levels to allow free variation in citations received among years. Confidence intervals and p ‐values were estimated with 1000 parametric bootstrap replicates. Analyses were performed in the R language and environment version 3.2.3. The mixed‐effect model was implemented using the lme4 package (Bates, 2005 ).

Scatterplot matrix showing intercorrelations of predictor variables. Points have been jittered for legibility. Red lines are smoothed lowess regressions. Number of pages and number of authors are presented on log‐transformed axes.

3.1. Longer papers are better cited than shorter papers

Across all journals, longer papers were consistently more highly cited than shorter papers (Figure 1 ). The slope of the relationships between citations and page length varied substantially among journals, as would be expected due to variation in manuscript formatting, mean paper lengths, and citation counts among journals (See Appendix Table A1 ). It is notable that the relationships between citations and page count were particularly steep for the shorter‐format journals (e.g., Ecology Letters and Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B ; Figure 1 ).

The relationship between total citations received and manuscript length for papers published 2009–2012 in 32 ecology journals. Lines represent the predictions for all journals from the ANCOVA model. Journals mentioned in the text are denoted with red‐dashed lines and are labeled.

However, this relationship could be a consequence of covariance between manuscript length and other variables that influence citations. In particular, the number of references cited by papers and the number of authors on papers have both been demonstrated to influence citation rates.

3.2. Papers that cite more references and have more authors are better cited

For ecology journals, page count, author count, and references cited all covary positively (Figure 2 ). Papers with more authors tend to be longer ( r absolute = .16; p < .001) and cite more references ( r absolute = .09; p < .001), and longer papers tend to cite more references ( r absolute = .56; p < .001). We thus used a mixed‐effect model to assess their relative contribution to citation frequency.

The model including these three variables indicated that manuscript length, author count, and references cited all covary positively with the number of citations received by an article (Figure 3 , Table 1 ). On average, a 10% increase in page count from the median (from 10 to 11 pages) generated a 1.8% increase in the number of times an article was cited. This increase varied among journals from a high of a 3.8% increase in citations for a 10% increase in manuscript length above the median in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology to a low of just 0.1% for Ecological Applications —the relationship is always positive but often small. A 10% increase in author count (from a median of 4 to 4.4 authors) had a similar effect, increasing the number of times an article was cited by 1.9%. A 10% increase in the number of references in the average journal (from a median of 54 to 59.4 references) increased the number of times an article was cited by 3.3%.

The relationship between total citations received and (a) manuscript length, (b) number of authors, and (c) number of references for papers published 2009–2012 in 32 ecology journals. Overall relationships from the mixed‐effect model are shown with heavy solid lines and confidence intervals, whereas relationships for individual journals are shown in thin lines. Lines are partial regressions after controlling for other effects in the full model presented in Table 1 . Journals highlighted in Figure 1 are denoted with red‐dashed lines and are labeled. All other variables are held at their medians. Note that the X‐axes of panels (a) and (b), as well as all Y‐axes, are log‐transformed.

The influence of manuscript length (pages), the number of authors, and reference count on the number of citations received