Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Towards a conceptual framework for the prevention of gambling-related harms: Findings from a scoping review

Contributed equally to this work with: Jamie Wheaton, Ben Ford

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

Affiliations School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom, Psychological Sciences, School of Natural and Social Sciences, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, United Kingdom, The Department of Psychology, Edge Hill University, Ormskirk, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ AN and SC also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation University of Bristol Business School, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- Jamie Wheaton,

- Ben Ford,

- Agnes Nairn,

- Sharon Collard

- Published: March 22, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The global gambling sector has grown significantly over recent years due to liberal deregulation and digital transformation. Likewise, concerns around gambling-related harms—experienced by individuals, their families, their local communities or societies—have also developed, with growing calls that they should be addressed by a public health approach. A public health approach towards gambling-related harms requires a multifaceted strategy, comprising initiatives promoting health protection, harm minimization and health surveillance across different strata of society. However, there is little research exploring how a public health approach to gambling-related harms can learn from similar approaches to other potentially harmful but legal sectors such as the alcohol sector, the tobacco sector, and the high in fat, salt and sugar product sector. Therefore, this paper presents a conceptual framework that was developed following a scoping review of public health approaches towards the above sectors. Specifically, we synthesize strategies from each sector to develop an overarching set of public health goals and strategies which—when interlinked and incorporated with a socio-ecological model—can be deployed by a range of stakeholders, including academics and treatment providers, to minimise gambling-related harms. We demonstrate the significance of the conceptual framework by highlighting its use in mapping initiatives as well as unifying stakeholders towards the minimization of gambling-related harms, and the protection of communities and societies alike.

Citation: Wheaton J, Ford B, Nairn A, Collard S (2024) Towards a conceptual framework for the prevention of gambling-related harms: Findings from a scoping review. PLoS ONE 19(3): e0298005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005

Editor: Francis Xavier Kasujja, Medical Research Council / Uganda Virus Research Institute & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Uganda Research Unit, UGANDA

Received: July 14, 2023; Accepted: January 16, 2024; Published: March 22, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Wheaton et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All files are available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/d7js2/ .

Funding: JW, BF, AN, and SC carried out this work as part of the Bristol Hub for Gambling Harms Research, which is funded by a grant from the national charity GambleAware. GambleAware is funded by voluntary donations from the gambling industry. Governance procedures and due diligence provide safeguards to ensure the Hub’s independence from GambleAware and the gambling industry. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. https://www.begambleaware.org/about-us .

Competing interests: All the co-authors (JW, BF, AN and SC) have received funding from GambleAware through their work at the Bristol Hub for Gambling Harms Research. The Bristol Hub for Gambling Harms Research (2022-2027) is funded by GambleAware which is funded by voluntary donations from the gambling industry to build capacity in interdisciplinary gambling harms research. Governance procedures and due diligence provide safeguards to ensure the Hub’s independence from GambleAware and the gambling industry. Neither GambleAware nor the gambling industry have any input to the strategic, operational or research activities of the Hub. SC has also received research funding from the Gambling Commission Regulatory Settlement funds. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Introduction

The gambling sector has seen significant growth in recent years due to liberal deregulation and digital transformation [ 1 ]. As of 2021, the global online gambling industry alone was worth US$61.5 billion, forecast to rise to US$114.4 billion by 2028 [ 2 ]. The increasing accessibility of gambling—such as the products available through smartphones [ 3 ]—increases the possibility of gambling-related harms (GRH) [ 4 ]. These harms are wide-ranging, covering numerous dimensions (such as financial, emotional or cultural) and they are not restricted to the gambler, also affecting their families and social networks [ 5 ]. There is therefore a growing support for a public health (PH) approach to GRH [ 4 , 6 – 9 ]. Thomas et al. [ 7 ] highlight five key pillars of a PH approach to GRH [ 7 ]: the development and implementation of a comprehensive public health framework to prevent gambling harm; the elimination of industry influence from research policy and practice; the addressing of structural characteristics which impede gambling harm prevention; strong restrictions on gambling-related marketing; and an independent public health-based education programme. Additionally, Price et al. [ 8 ] argue that operationalising a public health approach to gambling harms also requires five strategies: health promotion; health protection; disease prevention and harm minimisation; population health assessment; and health surveillance.

As the above examples highlight, a PH approach requires a multifaceted response with a range of initiatives and interventions not only to treat GRH on presentation, but also to prevent them from occurring in the first instance. Recent reports have identified that the targets and strategies of PH approaches to GRH must: recognise that the input of those with lived experience is integral [ 10 ]; understand product-based risks [ 11 – 13 ]; and include targeted advocacy and campaigning [ 14 , 15 ]. Other authors have suggested that initiatives should target affected others, wider communities [ 16 ] and entire populations [ 9 , 17 ] whilst also targeting specific at-risk communities [ 18 – 20 ].

To minimise GRH most effectively, frameworks which identify problems and present potential mitigating strategies are necessary [ 7 ]. A range of frameworks already exist, but they vary in their content and intent. These frameworks are introduced in Table 1 . Some frameworks have applied a pre-existing theoretical or methodological lens to describe gambling behaviour in relation to underpinning mechanisms or explanatory factors [ 21 – 25 ]. Several have focused predominantly on the conceptualization of harm and subsequent harm minimization strategies [ 17 , 26 – 29 ] with others focusing almost exclusively on strategies to minimise harm [ 30 , 31 ]. These harms-focused frameworks generally agree upon the types of harms experienced, even if demarcations between categories vary. Finally, several harms frameworks recognise the importance of targeting different sections of society [ 5 , 9 , 17 , 26 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.t001

There are, however, two themes which appear consistently throughout the frameworks in Table 1 : (1) a socio-ecological approach which recognises the need to focus on the relationship between harms and individual, community and societal determinants, and (2) the use of an established harms framework that is specific to the complex impacts of gambling [ 9 ]. Far less prominent are the range of goals and strategies that might make up a ‘public health’ approach to GRH. Thus, the construction of a comprehensive conceptual framework which can unify stakeholders towards GRH requires an exploration of the breadth of possible PH goals and strategies. Additionally, a comprehensive conceptual framework should be nuanced for the different strata of society which may experience GRH [ 7 ].

Our proposed conceptual model for GRH as a PH issue can help to overcome two significant barriers. First, the absence of a synthesizing framework makes mapping and evaluating the discrete aims of cross-disciplinary research or applied settings difficult. Secondly, no tool exists for organizations to evaluate current resource and service allocation. A PH approach requires rigorous and high-quality research evidence to inform decision-making [ 32 – 36 ]. Tools to support this understanding will help to identify opportunities for new organizations or future initiatives [ 37 , 38 ]. A shared or common conceptual framework would facilitate knowledge transfer between key stakeholders within different disciplines. Therefore, a shared framework would support the mapping of key research and initiatives in the gambling landscape and make communication and coordination easier amongst a variety of stakeholders.

Furthermore, a conceptual PH framework for GRH could benefit from lessons learned in other commercial, legal but potentially harmful, sectors, such as the alcohol, tobacco, and products high in fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) sectors. Although these comparisons are not widely prevalent within the frameworks highlighted in Table 1 , previous research has explored how specific interventions or approaches within other sectors can inspire similar strategies towards GRH. Friend and Ladd [ 39 ] evaluate how a PH approach to GRH could learn from interventions to curb tobacco advertising. Thomas et al. [ 40 ] explore the opinions of PH experts within these industries and find that industry actors provide a barrier to the instigation of PH policies through political lobbying and donations, thus highlighting the need for a delineation between policymakers and industry. Other work highlights how industry actors use messages around the complexities involved with deploying a PH approach to deter such an approach being taken [ 41 ]. A successful PH approach to GRH—with inspiration from other sectors—should be informed by approaches in those sectors which are successful in reducing harms. Accordingly, the aim of this paper is to explore how PH approaches to GRH could learn from the tobacco, alcohol and HFSS sectors. We propose a conceptual framework which aligns disparate PH strategies and approaches—and potentially unites sector stakeholders—towards the prevention of gambling-related harms. Moving beyond the frameworks we have explored above, our framework was constructed first of all by carrying out a scoping review of extant PH approaches towards alcohol-, HFSS-, tobacco-, and gambling-related harms. This explored—and developed a categorisation of—PH approaches found within each sector. Approaches to crime were also part of the original research focus but were excluded as we are concentrating only on legal products. We then categorised the PH approaches found during our scoping review and intersected them with the socio-ecological gambling-harms model proposed by Wardle et al. [ 17 ], allowing conceptual relationships to be drawn between potential PH strategies and goals, different levels of society, and different forms of GRH.

This paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we outline the methodology of the scoping review of previous PH approaches towards alcohol-, tobacco-, HFSS-, and gambling-related harms. Secondly, we evaluate the findings of the review, derived from a narrative analysis of the strategies prevalent within the sample of literature. Thirdly, the strategies and goals which emerged from our scoping review are developed into a conceptual framework for GRH. This also incorporates a socio-ecological model and a categorization of GRH outcomes by type of harm as well as severity and temporal experience of harm. Finally, we highlight how the framework can be used by a range of stakeholders towards the development of interventions which minimise GRH.

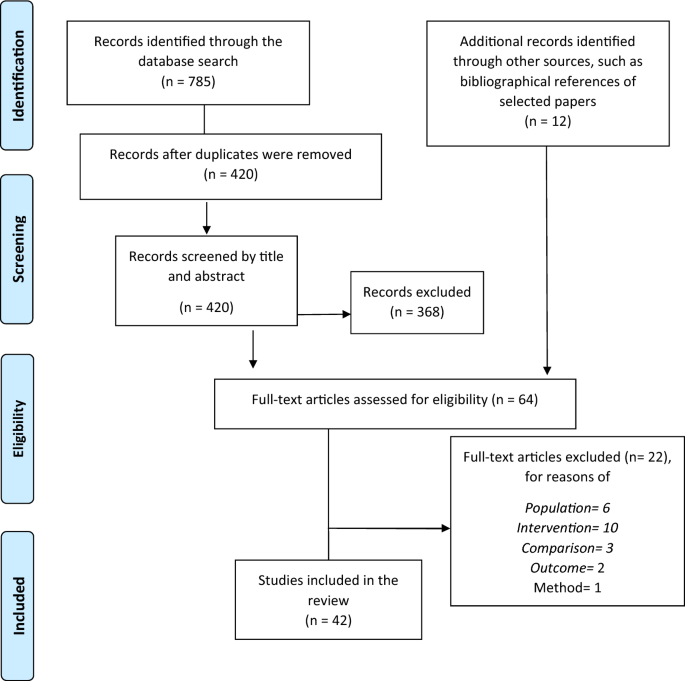

We conducted a scoping review to explore existing PH approaches to GRH, and how they could learn from the tobacco, alcohol and HFSS sectors. Our initial focus also included crime-related harms, given their impact on society, communities and individuals alike. However, the decision was made during the initial search to concentrate only on legal products. This was because the significantly different regulatory and economic relationship that industries supporting crime have with society and government given their illegality meant this topic was considered the ‘least’ relevant. We followed PRISMA guidelines [ 63 ] for the identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of papers, detailed in Fig 1 . We preregistered the scoping review on the Open Science Framework (OSF) ( https://osf.io/d7js2 ), and broadly followed the five stages as recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [ 64 ]. Our first stage consisted of the identification of the scoping review’s guiding research question: what is a public health approach to GRH and how can it learn from other sectors? To answer this question, our aim was to identify existing PH approaches towards tobacco-related, HFSS-related, alcohol-related harms alongside those towards GRH. These approaches would then be synthesized to develop a categorisation of PH approaches to GRH that would be developed into a collaborative framework.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.g001

The second stage was the identification of relevant studies. We (BF; JW) began this process with an initial search in November 2022, with search terms (public health) AND (approach OR framework OR tackling)) AND (gambl* OR tobacco OR alcohol OR crime OR fast food) entered into the Web of Science, PsycInfo, Scopus, Ovid Medline and Ovid Embase databases. We first selected ‘fast food’ as a search term but our initial search omitted research focused on other HFSS products such as sweet, salty and high fat food and beverages. We therefore conducted an additional search in January 2023 for papers related to HFSS products, using search terms ((public health) AND (approach OR framework OR tackling)) AND (food AND fast OR processed OR (high AND sugar OR salt OR fat) into the aforementioned databases. Eligible papers were those which adopted a specific PH focus towards the respective harms of each sector. The other inclusion criteria stipulated a focus on highly developed economies and articles written in English. With the research conducted within Great Britain, we sought papers published after 2005, the year in which the Gambling Act—which controls gambling in Great Britain—was given royal assent and which transformed gambling in Britain into a heavily advertised, deregulated commercial activity [ 1 ]. Once records had been identified from academic databases, we downloaded citation files and added them to Mendeley. We removed duplicates and then imported the remaining citation information into Excel. Additionally, we searched relevant websites for grey literature (see S1 Appendix ), using the search terms “public health approach” or “public health framework” or “public health”. Grey literature was sought from relevant organisations to provide insight beyond peer-reviewed journals. We downloaded relevant grey literature full texts and stored them in an online folder. Citation information was added into the Excel file by hand. We used the grey literature to compare approaches explored in peer-reviewed journals with those highlighted by non-academic organisations such as Alcohol Focus Scotland [ 65 ], or the Gambling-Related Harm All Party Parliamentary Group [ 66 ]. However, given the difference in robustness between peer-reviewed and grey literature, our findings are based solely upon those found within peer-reviewed literature.

Our initial searches returned a working sample of 15,378 titles after deduplication. We (JW and BF) then sifted through the working sample (N = 15,378) according to the inclusion criteria by title, abstract and full text. Our first sift by title saw the working sample reduced, according to the aforementioned criteria, to a new working sample of 1,037. At this point, we retained and separated alcohol-, HFSS- and tobacco-related review papers and gambling-related research papers into a new Excel sheet. We prioritised review papers for alcohol-, HFSS-, and tobacco-related harms (rather than papers describing individual studies) due to the short timeframe of the scoping review, and the inclusive nature of these reviews. Our second sift across both searches involved screening abstracts against the inclusion criteria and resulted in retaining 255 papers. Full details of excluded papers—and the reasons for exclusion—can be accessed through the OSF link. We (JW and BF) screened 231 alcohol-, tobacco- or HFSS- review papers by title, abstract and full-text, resulting in 43 retained for the fourth stage of data charting. One example of inclusion was Crombie et al.’s [ 67 ] review of interventions designed to prevent or reduce alcohol-related harms. Published after 2005, their review highlighted the range of interventions deployed in a range of advanced economies which can be adopted as a PH approach.

We reviewed individual gambling articles as per the original protocol, seeking empirical studies which either sought to explore the implementation of a public health strategy, or explored the requirements for such a strategy with findings drawn from participants’ behaviours or against the background of wider socio-economic, or commercial determinants. We also retained conceptual articles which we felt provided context to the strategies found within empirical articles. We screened 24 gambling-focused articles by full-text (two additional articles were identified from full-text reading), resulting in 20 being retained for data charting. An example of a gambling-related paper that fulfilled the inclusion criteria was Kolandai-Matchett et al.’s [ 33 ] study, which explored the implementation of a PH approach towards GRH in New Zealand.

Following Arksey and O’Malley [ 64 ], the final stage of our scoping review was the narrative analysis of themes prevalent within the sample of literature. We (JW and BF) analysed the specific PH-related approaches within each individual study or review paper. The full categories of data we extracted are introduced in Table 2 . We focused on the data extracted under the category of ‘Summary of Findings and Themes of Public Health’. Our narrative analysis grouped PH approaches by coding strategies and interventions according to type, thus developing a broader categorization of strategies which can be applied to reduction or prevention of GRH. We also coded the end goals or aims of strategies, thus resulting in broad PH goals which, when achieved, may result in the prevention or reduction GRH. We (JW and BF) coded strategies and goals separately, but found upon comparison that our respective analyses of goals and strategies returned similar results. After negotiation over the definition and categorization of goals and strategies, we ended with three broad PH goals which could be achieved by three broad PH strategies. We define these PH goals and strategies in the results of the narrative analysis section that follows below. These goals and strategies apply across tobacco, alcohol, HSSF and gambling.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.t002

Results of narrative analysis

The sample of alcohol-, HFSS-, and tobacco-focused reviews and gambling-focused studies (N = 63) is introduced within Table 3 , alongside the interventions explored within each paper. Table 3 highlights the wide range of journals and jurisdictions present within the sample. Whilst the interventions and approaches varied, our analysis of data from the scoping review found that interventions were driven towards achieving three broad PH goals and three broad PH strategies. These are discussed in the following two sections.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.t003

Three broad public health goals across potentially harmful product sectors

The PH Goals identified were (1) the prevention of harms, (2) the regulation of industry, and (3) support for those experiencing harms. This reflects the need to include both health promotion and an understanding of the epidemiology of non-communicable diseases. We discuss these three goals below.

We define the goal of prevention of harms as the need to prevent harms from occurring at the earliest opportunity through societal level awareness and destigmatisation . We highlighted prevention-focused strategies as occurring through health promotion campaigns which sought to denormalise harmful behaviours, whether through ‘responsible drinking’ campaigns [ 67 , 68 ], the provision of healthier alternatives to HFSS products [ 69 , 70 ] or the delivery of school-based awareness campaigns to reduce tobacco consumption [ 71 , 72 ]. Also prevalent across the reviews into alcohol-, HFSS-, and tobacco-related harms, was evidence of mass-media or educational campaigns which generate societal-level awareness. Our analysis, however, highlighted a lack of evidence of strategies which seek to destigmatise GRH. There is a perceived need according to stakeholders to increase public awareness of GRH [ 33 , 73 ], as well as to understand how different contexts may lead to GRH [ 74 – 76 ].

We define the goal of the regulation of industry as the need to prevent harms through the central management of industries and their products . How regulation should occur differed within the sample depending on the harm under study. Themes common across the alcohol-, HFSS-, and tobacco-focused reviews included the management of political lobbying [ 77 ], and the taxation of products [ 70 , 78 – 85 ]. As with the goal of prevention of harms, studies into the prevention or reduction of GRH identified a need for stronger regulation of the gambling industry, as opposed to offering evidence of the efficacy of legislative or regulatory measures already in place. Studies of stakeholders within the industry highlight the need to manage industry involvement within political lobbying processes [ 74 ], and the need to regulate specific products which are perceived as harmful [ 74 , 75 ]. Regulatory measures towards the prevention of GRH could therefore learn from approaches to harms within other sectors. Whilst the PH goal of regulation was prevalent across all sectors, only studies into GRH were unable to provide any evidence of the efficacy of regulatory measures.

We define the overarching goal of support of those experiencing harm as the need to treat harms already experienced through targeted , specialist help . This theme of targeted support was prevalent across every sector, although the strongest evidence linking targeted support to the reduction of harms was found within tobacco-related reviews [ 70 , 82 , 86 , 87 ]. There was also evidence within the other sectors of targeted support incorporating family or affected others [ 88 ] or community involvement [ 89 ]. Data from our scoping review again found that evidence bases within the other sectors were more developed in relation to support, than within the gambling sector. In contrast to the other sectors under study, studies into GRH provided evidence from stakeholders on how fulfilling the goal of support could lead to the reduction of harms [ 33 , 73 , 74 , 90 , 91 ]. However, the evidence linking targeted support to GRH still highlights the need to upscale support-led initiatives towards the reduction of societal-level harms [ 91 ].

Three broad public health strategies across potentially harmful product sectors

In addition to delineating three common public health goals across harmful product sectors, our narrative analysis of scoping review data also identified three broad types of public health strategy that can be used to achieve these goals: (1) education and awareness (EA), (2) screening, measurement and intervention (SMI) and (3) understanding environment and product (UEP).

The strategy of ‘education and awareness’ (EA) comprises initiatives which seek to prevent or reduce harms through the provision of research-led information . Within the alcohol sector, EA initiatives were aimed at children and adolescents [ 92 , 93 ], whilst also seeking to encourage ‘responsible drinking’ [ 67 , 68 ]. Within HFSS-related reviews, EA strategies were found within the provision of calorie or nutrition information [ 94 , 95 ], access to healthier alternatives [ 69 ], and the use of widespread awareness campaigns [ 78 , 96 – 98 ]. Widespread awareness campaigns on the harms of tobacco consumption were analysed as effective [ 71 , 72 , 82 , 99 ], particularly when used to encourage changes in harmful behaviours at a young age [ 100 ]. EA strategies identified within gambling-related studies highlighted a need for initiatives and evidence towards the destigmatisation of GRH through their recognition as a PH issue [ 33 ], and increased awareness of GRH amongst healthcare and service providers [ 73 ]. Research also concurred that EA-led, mass awareness should be disseminated free from commercial discourse such as ‘responsible gambling’ which enables the industry’s avoidance of responsibility and promotes the continuation of gambling regardless of level of harms experienced [ 75 ].

Secondly, Screening, Measurement, and Intervention (SMI) strategies are concerned with the screening of harms , the subsequent intervention where required , and the measurement required to track the prevalence of harms . SMI strategies—specifically intervention strategies—also comprise the management of industry practices, and their involvement within policymaking. Within alcohol-related reviews, interventions were geared towards the prevention of drink-driving [ 67 , 101 ], as well as support for those who are already experiencing alcohol-related harms [ 67 , 88 , 92 ]. Within HFSS-focused reviews, SMI strategies consisted of the management of industry involvement within policymaking [ 77 ] and targeted dietary interventions [ 96 ]. SMI strategies explored within tobacco-focused reviews included targeted, cessation interventions [ 82 , 86 , 88 ], advice given to patients and the training of staff [ 70 , 87 ], and the management of industry practice [ 77 ]. SMI strategies were also explored within tobacco-focused reviews through the adoption of the World Health Organisation’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) [ 84 ]. Within gambling-related studies, SMI strategies were again found, to provide targeted support to patients—and affected others [ 91 ]—through the need for more widespread support services [ 33 , 73 ] whilst also being linked with treatment for other comorbidities. Targeted, specialist support would also be aided by the deployment of an easily accessible screening tool [ 73 , 90 ]. The evidence shows strong support for the clear separation of the gambling industry from the government, as well as the transparency of lobbying by the industry itself [ 74 ]; and conceptual papers agree that regulation and policy should be immune to industry influence [ 32 , 102 , 103 ]. The separation of government and industry influence could also include the deployment of self-exclusion schemes which allow individuals to exclude themselves from gambling to avoid harms. Evidence presented by Kraus et al. [ 104 ] suggests that the state and the industry alike are ineffective at enforcing self-exclusion registers which can be easily circumvented. On the other hand, the authors still conclude that state-regulated registers are more likely to be effective at maintaining self-exclusion compared to those maintained by operators whose primary focus is revenue over harm limitation.

Strategies relating to the understanding of environment and product (UEP) explore how harmful behaviours emerge within specific contexts or from specific products , in order to prevent or reduce further harms . UEP strategies therefore seek to understand the social and environmental contexts which may lead to GRH and how these might be addressed. Alcohol-focused reviews provided three specific UEP strategies, namely reduced hours of sale [ 67 , 105 ], reduced outlet density [ 67 ], and the adoption of tax and price controls to deter harmful consumption [ 106 ]. HFSS-focused reviews also explored the effect of taxes on the consumption of unhealthy products [ 79 , 80 ], the effective protection of children from marketing [ 70 , 78 , 96 , 97 , 107 ], the display of calorie information on menus [ 94 , 95 ], and the impact of traffic light system labelling on the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages [ 81 ]. Tobacco-focused reviews highlighted the efficacy of tax and price controls alongside the deployment of smoke-free spaces which denormalises smoking [ 82 , 99 ]. As with the other two categories of PH strategy, gambling-focused studies highlighted a need for further UEP strategies to reduce harm, including more effective regulation of specific products—such as EGMs which were highlighted within the sample of studies as more harmful—which may encourage initial and continued harmful gambling behaviours [ 74 , 75 ], as well as the social cues which may encourage a pathway to harmful gambling behaviours [ 76 ]. Indeed, interactions with specific products may also be intertwined with various social interactions with friends [ 76 ], or with staff [ 74 ], and a deeper understanding of how GRH may arise from specific environments would allow best practice (from stakeholders) or regulation to protect those at risk.

Conceptual papers

Aside from the PH goals and strategies highlighted above, our scoping review also uncovered peer-reviewed papers whose approach was conceptual in nature. Conceptual approaches were mainly prevalent within papers whose focus was on the reduction or prevention of GRH. For the purposes of this paper, our grouping of conceptual papers included those which developed frameworks [ 36 , 49 ], highlighted the necessary collaborations for a PH approach [ 35 ], or viewpoints which underlined the need for clear delineation between industry and policymaking bodies [ 103 ]. These papers were retained within the initial sample thanks to their valuable insight.

Identifying existing frameworks

The categorisation of PH approaches that emerged from our scoping review was then used to develop a collaborative framework to address GRH. Our scoping review sought to identify literature that made recommendations for PH approaches or acknowledged wider socio-economic determinants of health in the gambling, tobacco, alcohol, and HFSS sectors. In many cases, the impact of PH interventions was not targeted at specific harms and approaches were intentionally operationalised to have general far-reaching impact. However, we recognised following our review that a framework that relates specific GRH to approaches requires categories of harms to be discernible. We also aimed to ensure that PH strategies identified from other areas were made relevant to gambling. It was thus necessary to include frameworks which have conceptualised GRH as this was not apparent in the articles identified from the scoping review. Therefore, separately from the scoping review but using the same databases, we identified a number of existing gambling-harm frameworks using the terms “gambl* AND harm AND (framework OR concept* OR strategy)”. We then evaluated the commonalities and differences and made a pragmatic decision about which conceptualisation to incorporate into our framework.

The PH goals and strategies outlined above constitute the core of our conceptual framework. However, such strategies and goals often only target specific levels of society [ 9 , 17 , 27 , 29 , 124 , 125 ] and individual categories of GRH [ 5 , 26 ]. There are also considerable differences between gambling and the other sectors reviewed. Approaches to alcohol-, HFSS-, and tobacco-related harms generally focused on the amendment of products such as the reduction of fat content in HFSS foods, the regulation of marketing, education to encourage behaviour change, and taxation. GRH-related papers, on the other hand, highlighted the need to counter industry interests, the need for more effective awareness of—and screening for—GRH within healthcare systems, and developing societal-level messaging that destigmatises GRH. Additionally, digitalisation affects gambling activities in a way that does not apply to alcohol, tobacco or HFSS consumption [ 1 , 3 ]. Therefore, we do not wish to suggest that the PH approaches evident in the scoping review represent an exhaustive list, nor that all approaches in other sectors are necessarily effective for, or relevant to, gambling. Rather, by grouping the existing approaches into broad overarching categories, we hope the conceptual framework is able to categorise the variety of approaches currently in-focus, as well as those yet to be proposed. Furthermore, for those wanting specific strategy proposals, researchers have made attempts to list numerous potential strategies to tackle GRH from a PH approach [ 7 , 8 ]. Our proposed conceptual framework is different because it offers a way to incorporate, and systematically organise, multiple PH goals and strategies while also taking into account the different social strata described in socio-ecological models and focusing on multiple categories of GRH.

In this section, we describe the process we followed to produce our conceptual framework. Firstly, we incorporate the socio-ecological model with the PH goals and strategies identified from the scoping review. Secondly, we then incorporate different GRH-related outcome categories, whilst also developing the framework to measure the severity and timescale over which GRH may be experienced. Following this process ensured that our framework was fully developed from the identification of PH goals and strategies, towards their application at different levels of society, and the prevention of GRH which may be wide-ranging and complex in nature.

Incorporating the socio-ecological model of gambling

Previous discussions of PH approaches highlight the necessity for a framework to understand gambling impacts at various levels of society [ 9 , 17 , 27 , 29 , 124 , 125 ]. The socio-ecological model is appropriate given its links to other PH domains [ 125 – 128 ] and its acknowledgement of the social and environmental determinants encountered by individuals which may also lead to GRH or shape people’s experiences of them [ 125 ]. The socio-ecological model emphasises that situational factors interact with an individual’s biopsychological characteristics [ 17 ]. For a long time, the focus of GRH research has been an individualised approach. We agree with others [ 7 , 8 ] who argue that focus should be shifted to wider determinants of GRH. Our model draws on similar strata highlighted by Wardle et al. [ 17 ], moving from ‘Individual’ to ‘Interpersonal’ to ‘Community’ and ‘Societal’, as introduced in Fig 2 . This stratification allows the targeting of intervention and treatment at specific parts of the population [ 9 , 17 , 29 ], and the understanding and mapping of the relations between various approaches or outcome goals. Public Health England (PHE) [ 129 ] used the socio-ecological model for a gap analysis of gambling risk factors, thus demonstrating the utility of the model as a tool to map research. For gambling specifically, the model shifts the focus from individual treatment approaches and explicitly recognises the harm caused to affected others [ 91 ], social groups [ 76 ], and at a societal level [ 9 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.g002

The ‘Individual’ level focuses on biopsychological characteristics that might be classified as ‘risk-factors’ as well as issues such as individualised interventions. The ‘Interpersonal’ level focuses attention on the social and family structures of at-risk individuals, such as the partners of pathological gamblers or interpersonal interventions. The ‘Community’ level relates to local or online environments, community groups, alongside institutions such as schools, banks and workplaces. Crucially, the ‘Community’ level targets ‘not-at-risk’ groups as well as identified ‘at-risk’ groups. Finally, the ‘Societal’ level encompasses whole-population approaches such as public policy decisions, national campaigns, and macro-structures that determine legal and cultural practices [ 9 , 17 ].

Connecting the conceptual framework to different categories, severity, and timeframes of harm

Whilst developed against a socio-economic model to explore impacts against individuals, communities and societies, our framework still requires development in its relationship with specific harms. We therefore firstly developed the framework in accordance with categories of harm outcomes that are already well-established within gambling-related research. Secondly, we addressed how specific GRH can be experienced more or less intensely over different periods of time.

Different categories of harm.

There are various conceptualizations of GRH. For example, PHE [ 129 ] classifies harms into financial; relationship; mental and physical health; employment and education; crime and anti-social behaviour; and cultural, with similar categories seen in other works [ 5 , 29 ]. The discrete categories proposed by Langham et al. [ 5 ], PHE [ 129 ], and Marionneau et al. [ 29 ] are useful if GRH is the focus of a framework, although even they rely on further sub-categorisation to encompass specific outcomes. However, in seeking to develop an overarching conceptual framework with a considerable number of intersecting goals, strategies and approaches, we decided to adopt Wardle et al.’s [ 17 ] concise approach which categorises harms into three broad categories: resources , relationships , and health , underneath which sit six sub-categories and fifty indicators. Table 4 maps the more detailed GRH categorisations against Wardle et al.’s [ 17 ] simplified three-category framework. Crime is defined by Wardle et al. [ 17 ] as a resource-based GRH, as emphasis is placed on measuring the impact of gambling behaviour on organisations, systems and victims through the medium of money or resource cost. However, whilst we agree that this is useful for the measurement of harm and for public health decision making [ 130 ], it is important to note that the relationship between gambling and crime is itself multifaceted and complex [ 131 ] and, as it is not a legal activity, it was excluded as an area of focus from the scoping review. Crime that results from gambling, however, is still categorised as a GRH. Crimes that result from gambling may consist of anti-social behaviour, entail gambling as a contributory factor [ 17 ], or systemic crimes where regulations are not followed by operators (for example, non-compliance in relation to unfair practices, underage gambling, or unfair advertising) [ 131 ]. All categories of harm—resources, relationships, and health—may arise as outcomes from gambling behaviour, as well as forming determinants which influence gambling behaviour itself.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.t004

Different severities and timescales.

Existing harms frameworks acknowledge that GRHs exist on a temporal continuum [ 5 , 27 ] from brief (or episodic) to long-term, or even intergenerational. Additionally, the harms experienced from gambling at any level of society can range from inconsequential, to general or crisis-level [ 5 ]. As before, we have adapted Wardle et al.’s [ 17 ] categorization of harms within our conceptual framework for measurement across this continuum, introduced in Fig 3 . These dimensions are a vitally important consideration when evaluating the implications or impact of gambling behaviour on individuals, social groups, communities, and societies in order to inform decision-making.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.g003

PH approaches encompass a range of goals and strategies, allowing for an understanding of complexity and nuance of societal health issues whilst retaining synergism. The core PH goals and strategies which emerged from our scoping review form the central interacting strands of a comprehensive conceptual framework for the prevention of GRH. This conceptual framework could also be helpful given that our analysis has demonstrated that the evidence base of a PH approach to GRH may be behind the curve compared to other sectors. To cement the shift away from focusing on individuals and reflect that public health approaches aim to minimise harm across families, social groups, communities and whole populations, our conceptual framework nests the PH goals and strategies within the socio-ecological model. To make it comprehensive, the conceptual framework also incorporates different categories of GRH as proposed by Wardle et al. [ 17 ], along with different severities and time scales.

Our full conceptual framework is introduced in Fig 4 . By mapping how PH goals and strategies intersect with gambling harms and how the intersections can be stratified by the socio-ecological model, we propose a highly interactive framework that can be used in research, policy and practice. The three broad PH strategies intersect with the three PH goals. At each intersection, the model recognises their relationship to gambling outcomes: either resource-based, relationship-based, or health-based harms. Importantly, each strategy-goal intersection and related GRH can be differentiated by level of socio-ecological model, spanning from individual to family and social networks , community , and society . Whilst many reports focus on ‘selective’ or ‘at-risk groups’ in the community [ 9 ], our framework additionally focuses on ‘untargeted’ approaches, given the importance of preventative measures in public health approaches at a societal level.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.g004

At a conceptual level, the tool allows researchers from varied disciplines to understand how their work intersects with society, specific GRH, and the wider gambling field. The framework will support the understanding of project related implications and impact. Furthermore, for stakeholders wishing to understand how a PH approach to gambling can be delivered or the types of considerations that need to be addressed, this conceptual mapping should prove useful. However, the framework’s utility is most evident through its use as a tool for applied and research settings. The framework can be used for organising, evaluating, and strategising in a research or service setting, with the subsequent benefit of facilitating communication and coordinated effort.

By populating the various intersections of the framework, stakeholders can systematically map research, policies, or services. The framework therefore serves four important functions, introduced in Fig 5 . Firstly, the framework facilitates mapping of the breadth and depth of initiatives designed to prevent or reduce GRH, and, in doing so, identifies gaps in research or provision. Secondly, the framework enables the evaluation of interventions and approaches in relation to different levels of society or against the different PH goals or strategies. Thirdly, the framework enables stakeholders to identify relationships between different intersections of the framework, service provisions, research areas within or across disciplines, or the aims of research and applied settings. Finally, the framework facilitates the understanding relationships and establishes potential avenues for communication and cooperation across different stakeholder groups or disciplines. These functions are introduced in further detail below.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.g005

The conceptual framework as a mapping tool

The primary function of the framework is that of mapping . Stakeholders could map support services at the intersection of SMI strategies towards the overarching goal of support at various levels of the socio-ecological model, in relation to specific GRH. Stakeholders could use the framework to understand how provision varies across society. For example, the framework may highlight a lack of services focused at the ‘families and social network’ level, suggesting a need for greater provision for affected others. Additionally, stakeholders may find that services are focusing predominantly on ’health’-related harms such as psychological distress whilst the mapping highlights that greater focus should be placed on reducing financial harms. In this sense, interacting with the framework can provide information to support informed resource allocation and decision-making. Mapping could be done using a matrix, as demonstrated in Table 5 below, which demonstrates the interaction between socio-ecological model, PH goals and strategies, as well as gambling-related outcomes, including ‘non-specific’ outcomes identified by stakeholders outside of the broad categorization offered by Wardle et al. [ 17 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.t005

The conceptual framework as an evaluation tool

A further, subsequent function for the conceptual framework is that of evaluation . Researchers could use the framework in a similar way to evaluate published literature. For example, a researcher may wish to evaluate the strength of evidence for awareness campaigns focused on safer gambling practices at different levels of society. This evaluation could focus on the intersections of EA strategies and the goal of prevention, as well as synthesise and evaluate the strength of evidence for other targeted, community, and whole population campaigns. This could then be easily translated into future campaign research or resource allocation in applied settings.

The conceptual framework as a means to identify relationships

The third function is identifying relationships . The relationships between the aims and implications of research can be easily translated to the goals of applied settings, if the framework is shared by research and applied settings. For example, researchers might compile evidence which supports more restrictive regulation of advertising, and therefore find their work situated at the intersection of UEP strategies and the goal of regulation of industry. On the other hand, they might be unsure of the number of organizations who could advocate and raise awareness for their proposals. The mapping of campaign and advocacy groups at such intersections of the framework could therefore identify potential relationships between research and applied efforts and bolster their impact.

The conceptual framework as a facilitator of communication and cooperation

Finally, the framework also facilitates communication and cooperation . Collating research and services on a common landscape highlights relationships between different areas of work and has the potential to cultivate productive interaction between stakeholders. A common framework facilitates a common language to discuss specific issues or initiatives. Furthermore, top-down organization can be facilitated through the mapping of provision to support the coordination of multiple stakeholder groups. For example, an organization focused on treatment and support for a specific group of individuals may wish to partner with other services to increase awareness of service availability. Having an easy-to-understand map of relevant organizations that offer similar provision in different sub-populations or regions, or a map of organizations whose focus is specifically education and awareness, could improve the impact of any action undertaken.

This paper has outlined our proposed conceptual framework for the prevention of GRH which was developed from the narrative analysis of findings from our scoping review. Our proposed framework aligns PH goals and strategies with existing harm frameworks and allows for differentiation at various ‘levels’ of society. By combining these features under a single overarching framework, stakeholders across disciplines can use a common language and work within a shared conceptual frame. The framework’s utility is clearest as an applied tool that promotes the mapping of research, provision, or organizational focus. Doing so facilitates evaluative exercises which can identify important gaps in research and provision through an understanding of depth and breadth of coverage, and leading to informed decision-making and resource allocation. Moreover, mapping can identify relationships between work across disciplines and settings, which has potential to facilitate cross-sectoral communication and coordination. This could strengthen collective efforts, lead to the development of opportunities and initiatives, and encourage both research informed practice and stakeholder involvement in research.

There are four main considerations when critically evaluating the outcome of the current paper. Firstly, we acknowledge that other studies or reviews—depending on the sector under focus—may not have been returned under the search terms used within our scoping review, and there thus may be other approaches which have not been explored here. However, given the variety of sectors explored within our scoping review, we contend that the broad categorisations developed as the base of our collaborative framework would allow the inclusion of other approaches as part of any mapping exercises.

This links to the second consideration, which is that the categories that compose each strand of the framework are broad. However, as each strand (socio-ecological model; PH goals; PH strategies; GRH) is synthesised or adopted from current research, it is possible to dissect these components in greater detail by reviewing the appropriate literature. Thus, researchers within specific disciplines may wish to sub-categorise strands relevant to them. However, this broad categorization has been done intentionally and for pragmatic reasons. Our framework is designed to be highly interactable and for use across disciplines, sectors and settings. It is the intention that broad categories will encourage the framework to be a collaborative platform that is inclusive to all. As long as the intersections described in this paper remain at the heart of further refinements, the framework’s utility as a tool for mapping, evaluation, coordination and communication persists. Further sub-categorization within disciplines should only serve to demonstrate the flexibility of the framework and encourage greater and more nuanced understanding. Similarly, for applied settings, whether the full extent of non-academic activities (e.g., those activities of charities, financial institutions, advocacy groups or services) fall within the proposed public health strategies. Therefore, as the framework is intended to support stakeholders to reduce GRH, this initial proposition should act as a starting point for further refinement.

Thirdly, the distinctions between certain intersections of the conceptual framework are not always exclusive. Strategies can benefit more than one level of the social-ecological model, improve outcomes for more than a single harm or benefit, or can be both preventative and supportive from a PH perspective. The framework is not intended to place restrictions on classification and duplicating information across sections should not be seen as an issue. Although, we recommend that when this occurs in relation to mapping GRH, it would be useful to incorporate an understanding of harm taxonomies [ 5 ] when deciding where to best place a specific research paper.

Finally, the framework’s conceptual utility is inherent in its depiction of how the component strands interact, and these relationships can be understood in greater detail as knowledge and research develops. The framework’s use as a mapping tool for research and practice relies on an ongoing and systematic process of populating and updating information at the various intersections. This can be achieved by individual organizations and researchers if they are using the framework for a specific goal. Given that each individual organization or researcher will have a specific focus due to time constraints or speciality, there is also potential benefit from the development of an online application that can serve the whole community. Therefore, a future initiative could include the creation of such an application.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. grey literature..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.s001

S1 Checklist. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298005.s002

- 1. Cassidy R. Vicious Games. London: Pluto Press; 2020.

- 2. Statista. Market size of the online gambling and betting industry worldwide in 2021, with a forecast for 2028. 2022 [Accessed 2023 April 24]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/270728/market-volume-of-online-gaming-worldwide/ .

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 9. Hilbrecht M. Prevention and Education Evidence Review: Gambling-Related Harm. Report prepared in support of the National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms in Great Britain. 2021 [cited 12 December 2022] https://doi.org/10.33684/2021.006 .

- 16. Walton B. A public health approach to gambling harms. The Scottish Parliament Information Centre. 2022 [cited 2022 December 15]. https://sp-bpr-en-prod-cdnep.azureedge.net/published/2022/12/12/bd948f62-f371-4af1-b54a-f1b2044a7eb4/SB%2022-67.pdf .

- 30. Costes JM. A logical framework for the evaluation of a harm reduction policy for gambling. In Bowden-Jones H, Dickson C, Dunand C, Simon C. Harm reduction for gambling. Routledge. 2019. Pp. 143–152.

- 37. Buck D, Dixon A. Improving the allocation of health resources in England. London: Kings Fund. 2013.

- 55. Province of British Columbia. BC’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2005–2008). 2006 [Retrieved 2023 January 4]. BC’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2005–2008) (gov.bc.ca).

- 56. Province of British Columbia. B.C.’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2008/09–2010/11). 2009 [Retrieved 2023 January 4]. BC’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2008/09-2010/11) (gov.bc.ca).

- 57. Province of British Columbia. B.C.’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2011/12–2013/14). 2011 [Retrieved 2023 January 4] https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/sports-recreation-arts-and-culture/gambling/gambling-in-bc/reports/plan-rg-three-yr-2011-2014.pdf .

- 58. Province of British Columbia. B.C.’s Responsible Gambling Strategy (2014/15-17/18). 2015 [Retrieved 2023 January 4] BC’s Responsible Gambling Strategy and Three Year Plan (2014–2018) (gov.bc.ca).

- 59. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Strategy to Prevent and Minimise Gambling Harm 2016/17-2018/19. 2016 [Retrieved 2023 January 4]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/strategy-prevent-and-minimise-gambling-harm-2016-17-2018-19 .

- 60. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Strategy to Prevent and Minimise Gambling Harm 2019/20-2021/22. 2019 [Retrieved 2023 January 4]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/strategy-prevent-and-minimise-gambling-harm-2019-20-.2021-22

- 61. New Zealand Ministry of Health. Strategy to Prevent and Minimise Gambling Harm 2012/23-2024/25. 2022 [Retrieved 2023 January 4]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/strategy-prevent-and-minimise-gambling-harm-2022-23-2024-25 .

- 62. Gambling Commission. National Strategy to Reduce Gambling Harms. 2019 [Retrieved 2022 November]. https://assets.ctfassets.net/j16ev64qyf6l/6Eupf9uXRQxBMPPvPP66QO/bb233acf9afd18c3169dc244557c0ad3/national-strategy-to-reduce-gambling-harms__2_.pdf .

- 65. Alcohol Focus Scotland. Tackling harm from alcohol: Alcohol policy priorities for the next Parliament. 2021 [Retrieved 2022 November 7]. low-res-4806-afs-manifesto-tackling-harm-from-alcohol.pdf (alcohol-focus-scotland.org.uk).

- 66. Gambling Related Harm All Party Parliamentary Group. Online Gambling Harm Inquiry: Final Report. 2020 [Retrieved 2022 November 4]. http://www.grh-appg.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Online-report-Final-June162020.pdf .

- 90. Nguyen THL, McGhie N, Bestman A, Ly J, Roberts M, Gibbeson S, et al. Enhancing gambling harm screening and referrals to gambling support services in general practice and community service settings in Fairfield LGA: a pilot study. Fairfield City Health Alliance. 2020 [Retrieved 2022 November 22]. https://swsphn.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Fairfield-City-Health-Alliance-Gambling-Screening-Final-Report.pdf .

- 129. Public Health England. (2021). Gambling-related harms evidence review: the economic and social cost of harms. 2021 [Retrieved 2022 December 5]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review .

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Contentious issues and future directions in adolescent gambling research.

1. Introduction: Underage Gambling

2. summary and aims of paper, 2.1. issue 1: elevated prevalence rates in adolescent samples, 2.2. issue 2: limited evidence of harm, 2.3. issue 3: low help-seeking rates, 2.4. issue 4: precursor to adult gambling: longitudinal evidence, 2.5. issue 5: the gateway hypothesis and activity transitions, 2.6. issue 6: sampling and the visibility of adolescent gambling, 3. enhancing adolescent gambling research and reporting, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L.; Derevensky, J. Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: Prevalence, current issues and concerns. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2016 , 3 , 268–274. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Derevensky, J.L.; Gupta, R. Adolescent gambling behavior: A prevalence study and examination of the correlates associated with problem gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 1998 , 14 , 319–345. [ Google Scholar ]

- Derevensky, J.L.; Gupta, R. Prevalence estimates of adolescent gambling: A comparison of the SOGS-RA, DSM-IV-J, and the GA 20 questions. J. Gambl. Stud. 2000 , 16 , 227–251. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Volberg, R.A.; Gupta, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Olason, D.T.; Delfabbro, P. An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. In Youth Gambling: The Hidden Addiction ; Derevensky, J.L., Shek, D.T.L., Merrick, J., Eds.; DeGruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 21–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Temcheff, C.E.; Derevensky, J.L.; St-Pierre, R.A.; Gupta, R. Beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals with respect to gambling and other high risk behaviors in schools. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2014 , 12 , 716–729. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Calado, F.; Alexandre, J.; Griffiths, M.D. Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: A systematic review of recent research. J. Gambl. Stud. 2017 , 33 , 397–424. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; Thrupp, L. The social determinants of gambling in South Australian adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2003 , 26 , 313–330. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rossen, F.V.; Clark, T.; Denny, S.J.; Fleming, T.M.; Peiris-John, R.; Robinson, E.; Lucassen, M.F.G. Unhealthy gambling amongst New Zealand secondary school students: An exploration of risk and protective factors. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2016 , 14 , 95–110. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Shaffer, H.J.; Hall, M.N. Estimating the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorders: A quantitative synthesis and guide toward standard gambling nomenclature. J. Gambl. Stud. 1996 , 12 , 193–214. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- UK Gambling Commission. Young People and Gambling 2018: A Research Study among 11–16 Year Olds in Great Britain ; UK Gambling Commission: London, UK, 2018.

- Dowling, N.A.; Shandley, K.A.; Oldenhof, E.; Affleck, J.M.; Youssef, G.J.; Frydenberg, E.; Thomas, S.A.; Jackson, A.C. The intergenerational transmission of at-risk/problem gambling: The moderating role of parenting practices. Am. J. Addict. 2017 , 26 , 707–712. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dowling, N.A.; Oldenhof, E.; Shandley, K.; Youssef, G.J.; Vasiliadis, S.; Thomas, S.A.; Frydenberg, E.; Jackson, A.C. The intergenerational transmission of problem gambling: The mediating role of offspring gambling expectancies and motives. Addict. Behav. 2018 , 77 , 16–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wijesingha Leatherdale, S.T.; Turner, N.E.; Elton-Marshall, T. Factors associated with adolescent online and land-based gambling in Canada. Addict. Res. Theory 2017 , 25 , 525–532. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Elton-Marshall, T.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Turner, N.E. An examination of internet and land-based gambling among adolescents in three Canadian provinces: Results from the youth gambling survey (YGS). BMC Public Health 2016 , 16 , 277. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Canale, N.; Griffiths, M.D.; Siciliano, V. Impact of Internet gambling on problem gambling among adolescents in Italy: Findings from a large nationally representative survey. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016 , 57 , 99–106. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Olason, D.T.; Kristjansdottir, E.; Einarsdottir, H.; Haraldsson, H.; Bjarnason, G.; Derevensky, J. Internet gambling and problem gambling among 13 to 18 year old adolescents in Iceland. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011 , 9 , 257–263. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gainsbury, S.M.; Hing, N.; Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L. A taxonomy of gambling and casino games via social media and other online technologies. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2014 , 14 , 196–213. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Drummond, A.; Sauer, J.D. Video game loot boxes are psychologically akin to gambling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018 , 2 , 530–532. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Dreier, M.; Greer, N.; Billieux, J. Unfair play? Video games as exploitative monetized services: An examination of game patents from a consumer protection perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019 , 101 , 131–143. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Predatory monetization features in video games (e.g., ‘loot boxes’) and Internet gaming disorder. Addiction 2018 , 113 , 1967–1969. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Kaptsis, D.; Zwaans, T. Simulated gambling via digital and social media in adolescence: An emerging problem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014 , 31 , 305–313. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zendle, D.; Meyer, R.; Over, H. Adolescents and loot boxes: Links with problem gambling and motivations for purchase. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019 , 6 , 190049. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Derevensky, J.; Gupta, R.; Winters, K. Prevalence rates of youth gambling problems: Are the current rates inflated? J. Gambl. Stud. 2003 , 19 , 405–425. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fisher, S.E. Measuring pathological gambling in children: The case of fruit machines in the UK. J. Gambl. Stud. 1992 , 8 , 263–285. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fisher, S.E. Gambling and pathological gambling in adolescents. J. Gambl. Stud. 1993 , 9 , 277–287. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fisher, S.E. A prevalence study of gambling and problem gambling in British adolescents. Addict. Res. 1999 , 7 , 509–538. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Volberg, R.A.; Moore, W.L. Gambling and Problem Gambling among Washington State Adolescents: A Replication Study, 1993 to 1999 ; Washington State Lottery: Olympia, WA, USA, 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Winters, K.C.; Stinchfield, R.D.; Fulkerson, J. Patterns and characteristics of adolescent gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 1993 , 9 , 371–386. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wynne, H.; Smith, G.; Jacobs, D. Adolescent Gambling and Problem Gambling in Alberta ; A Report Prepared for the Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission; Wynne Resources Ltd.: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta, R.; Derevensky, J. Gambling practices among youth: Etiology, prevention and treatment. In Adolescent Addiction: Epidemiology, Assessment and Treatment ; Essau, C., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 207–230. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore, S.; Ohtsuka, K. Gambling activities of young Australians: Developing a model of behavior. J. Gambl. Stud. 1997 , 13 , 207–236. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L. Is there a continuum of behavioural dependence in problem gambling? Evidence from 15 years of Australian prevalence research. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021 , 8 , 1–3. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thomas, S.L.; Bestman, A.; Pitt, H.; Cassidy, R.; McCarthy, S.; Nyemcsok, C.; Cowlishaw, S.; Daube, M. Young people’s awareness of the timing and placement of gambling advertising on traditional and social media platforms: A study of 11–16-year-olds in Australia. Harm Reduct. J. 2018 , 15 , 51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.; Griffiths, M.D. From adolescent to adult gambling: An analysis of longitudinal gambling patterns in South Australia. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014 , 30 , 547–563. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Fisher, S. Developing the DSM-IV Criteria to Identify Adolescent Problem Gambling in Non-Clinical Populations. J. Gambl. Stud. 2000 , 16 , 253–273. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Poulin, C. An assessment of the validity and reliability of the SOGS-RA. J. Gambl. Stud. 2002 , 18 , 67–93. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tremblay, J.; Stinchfield, R.; Wiebe, J.; Wynne, H. Canadian Adolescent Gambling Inventory (CAGI): Phase III Final Report. Canadian Consortium on Gambling Research (CCGR). 2010. Available online: http://www.ccgr.ca/en/projects/canadian-adolescent-gambling-inventory--cagi-.aspx (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- King, D.L.; Russell, A.; Hing, N. Adolescent land-based and online gambling: Australian and international prevalence rates and measurement issues. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020 , 7 , 137–148. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ladouceur, R.; Bouchard, C.; Rheaume, N.; Jacques, C.; Ferland, F.; Leblond, L.; Walker, M. Is the SOGS an accurate measure of pathological gambling among children, adolescents and adults? J. Gambl. Stud. 2000 , 16 , 1–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lambos, C.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Pulgies, S.; Department for Education and Children’s Services, Adelaide. Adolescent gambling in South Australia. In Report Prepared for the Independent Gambling Authority of South Australia ; Department for Education and Children’s Services: Adelaide, Australia, 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Delfabbro/publication/242769067_Adolescent_Gambling_in_South_Australia/links/0c9605293bbe4e8574000000/Adolescent-Gambling-in-South-Australia.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Griffiths, M.; Sutherland, I. Adolescent gambling and drug use. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998 , 8 , 423–427. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yeoman, T.; Griffiths, M.D. Adolescent machine gambling and crime. J. Adolesc. 1996 , 19 , 99–104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Burnett, J.; Ong, B.; Fuller, A. Correlates of gambling by adolescents. In Proceedings of the Developing Strategic Alliances: Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference of the National Association for Gambling Studies, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 25–27 November 1999; McMillen, J., Laker, L., Eds.; pp. 84–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; Lahn, J.; Grabosky, P. Further evidence concerning the prevalence of adolescent gambling and problem gambling in Australia. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2005 , 5 , 209–228. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ladouceur, R.; Mireault, C. Gambling behavior among high school students in the Quebec area. J. Gambl. Stud. 1988 , 4 , 3–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lesieur, H.; Klein, R. Pathological gambling among high school students. Addict. Behav. 1987 , 12 , 129–135. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Latvala, T.; Castren, S.; Alho, H.; Salonen, A. Compulsory school achievement and gambling among men and women aged 18–29 in Finland. Scand. J. Public Health 2018 , 46 , 505–513. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hardoon, K.; Gupta, R.; Derevensky, J. Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004 , 18 , 170–179. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Stinchfield, R. Gambling and correlates of gambling among Minnesota public school students. J. Gambl. Stud. 2000 , 16 , 153–173. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Girard, A.; Dionne, G.; Boivin, M. Longitudinal links between gambling participation and academic performance in youth: A test of four models. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018 , 34 , 881–892. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Raisamo, S.; Kinnunen, J.M.; Pere, L.; Lindfors, P.; Rimpelä, A. Adolescent Gambling, Gambling Expenditure and Gambling–Related Harms in Finland, 2011–2017. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019 , 36 , 597–610. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Griffiths, M.D. Adolescent Gambling ; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chevalier, S.; Griffiths, M.D. Why don’t adolescents turn up for gambling treatment (revisited)? J. Gambl. Issues 2004 , 11 , 1–11. Available online: www.camh.net/egambling/issue11/jgi_11_chevalier_griffiths.html (accessed on 24 August 2021). [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Griffiths, M. Why adolescents don’t turn up for treatment. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference of the European Association for Gambling Studies, Munich, Germany; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rigbye, J. Barriers to Treatment Access for Young Problem Gamblers. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dowling, N.; Merkouris, S.; Greenwood, C.; Oldenhof, E.; Toumbourou, J.; Youssef, G. Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016 , 51 , 109–124. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Stinchfield, R.; Cassuto, N.; Winters, K.; Latimer, W. Prevalence of gambling among Minnesota public school students in 1992 and 1995. J. Gambl. Stud. 1997 , 13 , 25–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Moore, S.; Ohtsuka, K. Youth gambling in Melbourne’s West: Changes between 1996 and 1998 for Anglo-European background and Asian background school based youth. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2001 , 1 , 87–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Slutske, W.S.; Jackson, K.M.; Sher, K.J. The natural history of problem gambling from age 18 to 29. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003 , 112 , 263–274. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Winters, K.C.; Stichfield, R.D.; Kim, L.G. Monitoring adolescent gambling in Minnesota. J. Gambl. Stud. 1995 , 11 , 165–183. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Winters, K.C.; Stinchfield, R.D.; Botzet, A.; Anderson, N. Prospective study of youth gambling behaviours. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002 , 16 , 3–9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Winters, K.C.; Stinchfield, R.D.; Botzet, A.; Slutske, W.S. Pathways of youth gambling problem severity. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005 , 19 , 104–107. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Carbonneau, R.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Variety of gambling activities from adolescence to age 30 and association with gambling problems: A 15-year longitudinal study of a general population sample. Addiction 2015 , 110 , 1985–1993. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; Winefield, A.H.; Anderson, S. Once a gambler- always a gambler- longitudinal analysis of adolescent gambling patterns. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2009 , 9 , 151–164. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hollen, L.; Dorner, R.; Griffiths, M.; Emond, A. Gambling in young adults aged 17–24 years: A population based study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2020 , 36 , 347–366. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goudriaan, A.; Slutske, W.; Krull, J.; Sher, K. Longitudinal patterns of gambling activities and associated risk factors. Addiction 2009 , 104 , 1219–1232. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Dussault, F.; Brunelle, N.; Kairouz, S.; Rousseau, M.; Leclerc, D.; Tremblay, J.; Cousineau, M.-M.; Dufour, M. Transition from playing with simulated gambling games to gambling with real money: A longitudinal study in adolescence. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2017 , 17 , 386–400. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gainsbury, S.M.; King, D.L.; Russell, A.; Delfabbro, P.; Hing, N. The cost of virtual wins: An examination of gambling-related risks in youth who spend money on social casino games. J. Behav. Addict. 2016 , 5 , 401–409. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayer, T.; Kalke, J.; Meyer, G.; Brosowski, G. Do simulated gambling activities predict gambling with real money during adolescence? Empirical findings from a longitudinal study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018 , 34 , 929–947. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, H.S.; Hollingshead, S.; Wohl, M.J. Who spends money to play for free? Identifying who makes micro-transactions on social casino games (and why). J. Gambl. Stud. 2017 , 33 , 525–538. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Molde, H.; Holmøy, B.; Merkesdal, A.G.; Torsheim, T.; Mentzoni, R.A.; Hanns, D.; Sagoe, D.; Pallesen, S. Are video games a gateway to gambling? A longitudinal study based on a representative Norwegian sample. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019 , 35 , 545–557. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Video game monetization (e.g., ‘loot boxes’): A blueprint for practical social responsibility measures. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019 , 17 , 166–179. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Derevensky, J.L.; Griffiths, M.D. A review of Australian classification practices for commercial video games featuring simulated gambling. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2012 , 12 , 231–242. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zendle, D.; Cairns, P. Loot box spending in video games is again linked to problem gambling. PLoS ONE 2019 , 13 , e0206767. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zendle, D.; Cairns, P.; Barnett, H.; McCall, C. Paying for loot boxes is linked to problem gambling, regardless of specific features such as cash-out or pay-to-win. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020 , 102 , 181–191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kim, H.S.; Wohl, M.J.; Salmon, M.M.; Gupta, R.; Derevensky, J. Do social casino gamers migrate to online gambling? An assessment of migration rate and potential predictors. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015 , 31 , 1819–1831. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Delfabbro, P.H.; King, D.L. Gaming-gambling convergence: Evaluating evidence for the ‘gateway’ hypothesis. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2020 , 20 , 380–392. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Campbell, C.; Derevensky, J.; Meerkamper, E.; Cutajar, J. Parents’ perceptions of adolescent gambling: A Canadian national study. J. Gambl. Issues 2011 , 25 , 36–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]