COPD Case Study: Patient Diagnosis and Treatment (2024)

by John Landry, BS, RRT | Updated: May 16, 2024

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease that affects millions of people around the world. It is primarily caused by smoking and is characterized by a persistent obstruction of airflow that worsens over time.

COPD can lead to a range of symptoms, including coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, which can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.

This case study will review the diagnosis and treatment of an adult patient who presented with signs and symptoms of this condition.

25+ RRT Cheat Sheets and Quizzes

Get access to 25+ premium quizzes, mini-courses, and downloadable cheat sheets for FREE.

COPD Clinical Scenario

A 56-year-old male patient is in the ER with increased work of breathing. He felt mildly short of breath after waking this morning but became extremely dyspneic after climbing a few flights of stairs. He is even too short of breath to finish full sentences. His wife is present in the room and revealed that the patient has a history of liver failure, is allergic to penicillin, and has a 15-pack-year smoking history. She also stated that he builds cabinets for a living and is constantly required to work around a lot of fine dust and debris.

Physical Findings

On physical examination, the patient showed the following signs and symptoms:

- His pupils are equal and reactive to light.

- He is alert and oriented.

- He is breathing through pursed lips.

- His trachea is positioned in the midline, and no jugular venous distention is present.

Vital Signs

- Heart rate: 92 beats/min

- Respiratory rate: 22 breaths/min

Chest Assessment

- He has a larger-than-normal anterior-posterior chest diameter.

- He demonstrates bilateral chest expansion.

- He demonstrates a prolonged expiratory phase and diminished breath sounds during auscultation.

- He is showing signs of subcostal retractions.

- Chest palpation reveals no tactile fremitus.

- Chest percussion reveals increased resonance.

- His abdomen is soft and tender.

- No distention is present.

Extremities

- His capillary refill time is two seconds.

- Digital clubbing is present in his fingertips.

- There are no signs of pedal edema.

- His skin appears to have a yellow tint.

Lab and Radiology Results

- ABG results: pH 7.35 mmHg, PaCO2 59 mmHg, HCO3 30 mEq/L, and PaO2 64 mmHg.

- Chest x-ray: Flat diaphragm, increased retrosternal space, dark lung fields, slight hypertrophy of the right ventricle, and a narrow heart.

- Blood work: RBC 6.5 mill/m3, Hb 19 g/100 mL, and Hct 57%.

Based on the information given, the patient likely has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) .

The key findings that point to this diagnosis include:

- Barrel chest

- A long expiratory time

- Diminished breath sounds

- Use of accessory muscles while breathing

- Digital clubbing

- Pursed lip breathing

- History of smoking

- Exposure to dust from work

What Findings are Relevant to the Patient’s COPD Diagnosis?

The patient’s chest x-ray showed classic signs of chronic COPD, which include hyperexpansion, dark lung fields, and a narrow heart.

This patient does not have a history of cor pulmonale ; however, the findings revealed hypertrophy of the right ventricle. This is something that should be further investigated as right-sided heart failure is common in patients with COPD.

The lab values that suggest the patient has COPD include increased RBC, Hct, and Hb levels, which are signs of chronic hypoxemia.

Furthermore, the patient’s ABG results indicate COPD is present because the interpretation reveals compensated respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia. Compensated blood gases indicate an issue that has been present for an extended period of time.

What Tests Could Further Support This Diagnosis?

A series of pulmonary function tests (PFT) would be useful for assessing the patient’s lung volumes and capacities. This would help confirm the diagnosis of COPD and inform you of the severity.

Note: COPD patients typically have an FEV1/FVC ratio of < 70%, with an FEV1 that is < 80%.

The initial treatment for this patient should involve the administration of low-flow oxygen to treat or prevent hypoxemia .

It’s acceptable to start with a nasal cannula at 1-2 L/min. However, it’s often recommended to use an air-entrainment mask on COPD patients in order to provide an exact FiO2.

Either way, you should start with the lowest possible FiO2 that can maintain adequate oxygenation and titrate based on the patient’s response.

Example: Let’s say you start the patient with an FiO2 of 28% via air-entrainment mask but increase it to 32% due to no improvement. The SpO2 originally was 84% but now has decreased to 80%, and his retractions are worsening. This patient is sitting in the tripod position and continues to demonstrate pursed-lip breathing. Another blood gas was collected, and the results show a PaCO2 of 65 mmHg and a PaO2 of 59 mmHg.

What Do You Recommend?

The patient has an increased work of breathing, and their condition is clearly getting worse. The latest ABG results confirmed this with an increased PaCO2 and a PaO2 that is decreasing.

This indicates that the patient needs further assistance with both ventilation and oxygenation .

Note: In general, mechanical ventilation should be avoided in patients with COPD (if possible) because they are often difficult to wean from the machine.

Therefore, at this time, the most appropriate treatment method is noninvasive ventilation (e.g., BiPAP).

Initial BiPAP Settings

In general, the most commonly recommended initial BiPAP settings for an adult patient include this following:

- IPAP: 8–12 cmH2O

- EPAP: 5–8 cmH2O

- Rate: 10–12 breaths/min

- FiO2: Whatever they were previously on

For example, let’s say you initiate BiPAP with an IPAP of 10 cmH20, an EPAP of 5 cmH2O, a rate of 12, and an FiO2 of 32% (since that is what he was previously getting).

After 30 minutes on the machine, the physician requested another ABG to be drawn, which revealed acute respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia.

What Adjustments to BiPAP Settings Would You Recommend?

The latest ABG results indicate that two parameters must be corrected:

- Increased PaCO2

- Decreased PaO2

You can address the PaO2 by increasing either the FiO2 or EPAP setting. EPAP functions as PEEP, which is effective in increasing oxygenation.

The PaCO2 can be lowered by increasing the IPAP setting. By doing so, it helps to increase the patient’s tidal volume, which increased their expired CO2.

Note: In general, when making adjustments to a patient’s BiPAP settings, it’s acceptable to increase the pressure in increments of 2 cmH2O and the FiO2 setting in 5% increments.

Oxygenation

To improve the patient’s oxygenation , you can increase the EPAP setting to 7 cmH2O. This would decrease the pressure support by 2 cmH2O because it’s essentially the difference between the IPAP and EPAP.

Therefore, if you increase the EPAP, you must also increase the IPAP by the same amount to maintain the same pressure support level.

Ventilation

However, this patient also has an increased PaCO2 , which means that you must increase the IPAP setting to blow off more CO2. Therefore, you can adjust the pressure settings on the machine as follows:

- IPAP: 14 cmH2O

- EPAP: 7 cmH2O

After making these changes and performing an assessment , you can see that the patient’s condition is improving.

Two days later, the patient has been successfully weaned off the BiPAP machine and no longer needs oxygen support. He is now ready to be discharged.

The doctor wants you to recommend home therapy and treatment modalities that could benefit this patient.

What Home Therapy Would You Recommend?

You can recommend home oxygen therapy if the patient’s PaO2 drops below 55 mmHg or their SpO2 drops below 88% more than twice in a three-week period.

Remember: You must use a conservative approach when administering oxygen to a patient with COPD.

Pharmacology

You may also consider the following pharmacological agents:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Albuterol)

- Long-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Formoterol)

- Anticholinergic agents (e.g., Ipratropium bromide)

- Inhaled corticosteroids (e.g., Budesonide)

- Methylxanthine agents (e.g., Theophylline)

In addition, education on smoking cessation is also important for patients who smoke. Nicotine replacement therapy may also be indicated.

In some cases, bronchial hygiene therapy should be recommended to help with secretion clearance (e.g., positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy).

It’s also important to instruct the patient to stay active, maintain a healthy diet, avoid infections, and get an annual flu vaccine. Lastly, some COPD patients may benefit from cardiopulmonary rehabilitation .

By taking all of these factors into consideration, you can better manage this patient’s COPD and improve their quality of life.

Final Thoughts

There are two key points to remember when treating a patient with COPD. First, you must always be mindful of the amount of oxygen being delivered to keep the FiO2 as low as possible.

Second, you should use noninvasive ventilation, if possible, before performing intubation and conventional mechanical ventilation . Too much oxygen can knock out the patient’s drive to breathe, and once intubated, these patients can be difficult to wean from the ventilator .

Furthermore, once the patient is ready to be discharged, you must ensure that you are sending them home with the proper medications and home treatments to avoid readmission.

Written by:

John Landry is a registered respiratory therapist from Memphis, TN, and has a bachelor's degree in kinesiology. He enjoys using evidence-based research to help others breathe easier and live a healthier life.

- Faarc, Kacmarek Robert PhD Rrt, et al. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 12th ed., Mosby, 2020.

- Chang, David. Clinical Application of Mechanical Ventilation . 4th ed., Cengage Learning, 2013.

- Rrt, Cairo J. PhD. Pilbeam’s Mechanical Ventilation: Physiological and Clinical Applications. 7th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Gardenhire Douglas EdD Rrt-Nps. Rau’s Respiratory Care Pharmacology. 10th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Heuer Al PhD Mba Rrt Rpft. Wilkins’ Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care. 8th ed., Mosby, 2017.

- Rrt, Des Terry Jardins MEd, and Burton George Md Facp Fccp Faarc. Clinical Manifestations and Assessment of Respiratory Disease. 8th ed., Mosby, 2019.

Recommended Reading

How to prepare for the clinical simulations exam (cse), faqs about the clinical simulation exam (cse), 7+ mistakes to avoid on the clinical simulation exam (cse), copd exacerbation: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epiglottitis scenario: clinical simulation exam (practice problem), guillain barré syndrome case study: clinical simulation scenario, drugs and medications to avoid if you have copd, the pros and cons of the zephyr valve procedure, the 50+ diseases to learn for the clinical sims exam (cse).

Living with COPD - My Story

Whether you are a patient, carer, clinician or interested bystander, my hope is that what I share in my story about living with COPD resonates with you in some way.

That was then: My way to diagnosis and beyond

I was born in the 40s and like many of my generation, I was a regular smoker until I quit in when I was in my 50s. By quitting I believed that I had dodged a bullet because for eight years I enjoyed good health. In 2003 I began to experience subtle symptoms, such as shortness of breath, cough and chest congestion and infections, which belied the seriousness of the condition that I now live with. It wasn’t until my mid-fifties that I was told I had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and had lost more than 25 % of my lung capacity. At this point, no mention was made of rehabilitation or structured exercise in addition to medication, but I still felt well. I took the required inhalants and medication as prescribed so I thought I had stopped the disease in its tracks. I also still held a demanding and responsible job, and retirement was a distant vision. So much for blissful ignorance!

In 2011 I was forced to confront reality. My breathing became considerably worse and began to impact my everyday life. Things took longer to do and I worked hard to hide the worst of my symptoms from my greatest supporter and most severe critic, my significant other. Fortunately for me, my wife is far smarter than I am and insisted that I consult another respiratory specialist and plan an exit from work, enabling us to share what I had almost lost sight of, a now uncertain future for us to enjoy. With another breathing test result showing a 50 per cent loss of predicted capacity, I faced reality and my own mortality squarely in the eye for the very first time.

My advice: Knowledge is power, so educate yourself on your condition. And be prepared to question your doctors. It’s not just your right, it is your responsibility.

It was good fortune that the specialist had on his desk a copy of LungNet News, the official newsletter of Lung Foundation Australia . I took the copy and contacted them directly and was referred to the Royal Brisbane Hospital Thoracic Department where I soon after began pulmonary rehabilitation. For those not familiar with these programs, they typically comprise an initial assessment, a review of individual physical capability based on age or disability, followed by an eight week, twice weekly class including tailored gym exercise for an hour which is usually complemented by education sessions covering a variety of topics like lung pathology, medication, diet, breathing techniques and management of anxiety.

Following the pulmonary rehabilitation program, I kept up the routine and since then I religiously attend this class twice weekly. I believe this is one of the most critical factors in maintaining good health for people with COPD. Evidence points to exercise being more beneficial or effective than many prescribed medications. The other very important step during pulmonary rehabilitation is the preparation of a patient driven action plan based on a ‘traffic light’ system. The patient and their doctor establish green, amber, red, symptom levels with corresponding escalating levels of action the patient must take. In doing so the patient is empowered to take ownership of their own condition and immediate responsibility for their health. It’s all about listening to your body and getting to know it well.

Giving back

I decided that now retired, I would become a member of Lung Foundation Australia and perhaps help out to give back. I was asked to help update the national data base for patient support groups. This enabled me to talk directly to other sufferers and carers throughout Australia. I learned a lot about lung disease in general, and came to appreciate the great work the people of this organisation do on behalf of the patients, carers and the community as a whole. I was invited to join the national CPAG (COPD Patient Advocacy Group) to support patients and carers to have a voice within the Foundation on goal setting and priorities.

My personal experience at the Lung Foundation opened my eyes to how much patients ourselves can bring a unique perspective to lung disease awareness, research and self-management by virtue of first-hand experience. My continued philosophy was that if I can assist in preventing any future cases of lung disease or through advocacy improve awareness, diagnosis, management and quality of life for my fellow suffers, then I consider my time well spent.

This is now: Taking part in shaping the future of COPD management

Twelve years post diagnosis and after completing pulmonary rehabilitation and commencing my volunteer work with Lung Foundation Australia, I can look back with some satisfaction at where I am and what I have achieved.

My COPD is stable, despite having suffered a couple of exacerbations over the last couple of years. I repeated pulmonary rehabilitation after my first flare up and continue to learn more about lung disease. I have completed a clinical medication trial and will continue to look for further tests or trials in which I can participate. I have also informally counselled others who approached me to help them better understand their condition and recalled my experiences on a similar journey of discovery.

I participated in the COPD Global Foundation Summit in France, which has the goal of driving worldwide change in the recognition, diagnosis and treatment of COPD. It was an honour to represent Australia at the forum. It was very interesting to see how COPD is managed in different cultures and nations.

My hope is that the COPD Global Foundation and its network of patients, carers and clinicians will develop into a well-respected, accessible resource with a voice that will reach the most remote communities to help, and indeed be the catalyst for change, in improving the lives and conditions of people with COPD, no matter where they are in the world.

My advice: Take Responsibility for Your Health

In retrospect, it would be easy but unfair to single out doctors for their often reactive approach to the management of chronic diseases such as COPD. More often than not, they have an abundance of patients, multiple critical cases and time pressures to deal with. As patients we must learn to help ourselves by demanding the time of our doctors, educating ourselves on diseases prior to consultations and preparing questions. We are generally not keen to hear bad news, the rationale being that if we need to hear more, the doctor will tell us all. If he does not then all is well. There can be fatal flaws in that belief. If we do not show initiative and purpose in our dealings with clinicians, or take responsibility for the management of our own health, we deserve the treatment we get. My advice is simple. Knowledge is power, so educate yourself on your condition. And be prepared to question your doctors: it’s not just your right, it is your responsibility.

Ian Venamore was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in his mid-fifties. Today he is an active volunteer member of Lung Foundation Australia and chair of the associated COPD Patient Advocacy Group (CPAG).He also participates in international meetings with the goal to change the future of COPD recognition, diagnosis and treatment. He is a strong advocate for pulmonary rehabilitation and attends his gym classes “religiously.” He is also a firm believer in and proponent of patient education and self management.

Other Stories

Nothing About Me Without Me

Whereas in the past, patients were only regarded as study "subjects", nowadays they are playing an increasingly important role in healthcare and clinical research.

Listening to patients and what matters to them

The use of Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) in clinical research

Patients Becoming Partners in Research

When it comes to clinical trials, everyone knows the drill: experts create and patients participate. Right?

Please Login to Comment

Forgot your password?

This website intends to use cookies to improve the site and your experience.

By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to accept our use of cookies. If you require further information and/or do not wish to have cookies placed when using the site, click here: About Cookies .

It seems you are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser to improve your experience on this website.

A COPD Case Study: Jim B.

This post was written by Jane Martin, BA, LRT, CRT, Assistant Director of Education at the COPD Foundation .

We're interested in your thoughts on our latest COPD case study: Jim B., a 68-year-old man here for his Phase II Pulmonary Rehabilitation intake interview.

A bit more about Jim:

Medical history: COPD, FEV1 six weeks ago was 38% of normal predicted, recent CXR shows flattened diaphragm with increased AP diameter, appendectomy age 34, broken nose and broken right arm as a child.

Labs: Lytes plus and CBC all within normal limits.

Physical exam: Breath sounds markedly diminished bilaterally with crackles right lower lobe and wheeze left upper lobe. Visible use of accessory muscles. O2 Saturation 93% room air, 95% O2 on 2lpm. Respiratory rate 24 and shallow, HR 94, BP 150/88, 1+ pitting pedal edema.

Current Medications: Prednisone 10mg q day / DuoNeb q 4 hrs. / Ibuprofen 400mg BID / Tums prn (estimates he takes two per day).

Respiratory history: 80-pack-year cigarette history, quit last year. He has developed a dry, hacking, non-productive cough over the last six months. Had asthma as a child and was exposed to second-hand smoke and cooking fumes while working at family-owned restaurant as a child. Lately, he has noticed slight chest tightness and increased cough when visiting his wife’s art studio.

Family history: Father had emphysema, died at age 69, mother died of breast cancer at 62. Grandfather died at age 57, grandmother died in her 40s of suicide. Six adult children, alive and well.

Previous respiratory admissions: Inpatient admission for six days last winter for acute exacerbation of COPD with bacterial pneumonia requiring 24-hour intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Psych: Jim presents to his Phase II Pulmonary Rehab intake interview appearing disheveled, wearing a sweatshirt, pajama pants and bedroom slippers. He is accompanied by his wife and adult daughter who appear neat, clean and well dressed. Patient states, “I don’t think you people can do anything to help me. I’m only here because they (referring to wife and daughter) made me go.” Jim states that he has been doing less and less at home since discharged from the hospital last winter. Wife states, “He walked outside a little with our grandchildren last Sunday and got so short of breath, he almost collapsed.” Became emotional when saying, “It scared the kids. It tore me up for them to see me that way. Besides that, with this darn shoulder I can’t even pick up the little ones anymore.”

Social: Lives at home with his wife of 43 years who works as an artist. Two out of his six children live within 30 miles of Jim’s home.

Occupation: Building contractor, retired three years ago. Jim states, “I made a good living. All the kids were able to go to college. I was strong. I could work circles around anybody in my crew. And now look at me. I’m tied to that darn breathing machine (referring to nebulizer) and I might as well hang it up.” Wife states, “He used to have all kinds of energy. Now all he does is sit in his chair watching TV, eating potato chips and peanuts.”

Tell us your impressions!

- What co-morbidities should be explored?

- How would you change Jim’s medication regime?

- What psych/social recommendations would you make?

- What other medical disciplines should do a consult on this patient?

- This is a real case. What are your thoughts on what took place following Jim’s pulmonary rehab intake interview?

This page was reviewed on March 3, 2020 by the COPD Foundation Content Review and Evaluation Committee

15 Comments

Join Us on COPD360social

Join the Conversation

Already a Member?

- Login / Register

‘Much will be said and promised over the next six weeks’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: COPD

Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study

04 May, 2020

This case study explains the symptoms, causes, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This article uses a case study to discuss the symptoms, causes and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, describing the patient’s associated pathophysiology. Diagnosis involves spirometry testing to measure the volume of air that can be exhaled; it is often performed after administering a short-acting beta-agonist. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease involves lifestyle interventions – vaccinations, smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation – pharmacological interventions and self-management.

Citation: Price D, Williams N (2020) Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study. Nursing Times [online]; 116: 6, 36-38.

Authors: Debbie Price is lead practice nurse, Llandrindod Wells Medical Practice; Nikki Williams is associate professor of respiratory and sleep physiology, Swansea University.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is used to describe a number of conditions, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although common, preventable and treatable, COPD was projected to become the third leading cause of death globally by 2020 (Lozano et al, 2012). In the UK in 2012, approximately 30,000 people died of COPD – 5.3% of the total number of deaths. By 2016, information published by the World Health Organization indicated that Lozano et al (2012)’s projection had already come true.

People with COPD experience persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that can be due to airway or alveolar abnormalities, caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases, commonly from tobacco smoking. The projected level of disease burden poses a major public-health challenge and primary care nurses can be pivotal in the early identification, assessment and management of COPD (Hooper et al, 2012).

Grace Parker (the patient’s name has been changed) attends a nurse-led COPD clinic for routine reviews. A widowed, 60-year-old, retired post office clerk, her main complaint is breathlessness after moderate exertion. She scored 3 on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (Fletcher et al, 1959), indicating she is unable to walk more than 100 yards without stopping due to breathlessness. Ms Parker also has a cough that produces yellow sputum (particularly in the mornings) and an intermittent wheeze. Her symptoms have worsened over the last six months. She feels anxious leaving the house alone because of her breathlessness and reduced exercise tolerance, and scored 26 on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT, catestonline.org), indicating a high level of impact.

Ms Parker smokes 10 cigarettes a day and has a pack-year score of 29. She has not experienced any haemoptysis (coughing up blood) or chest pain, and her weight is stable; a body mass index of 40kg/m 2 means she is classified as obese. She has had three exacerbations of COPD in the previous 12 months, each managed in the community with antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol.

Ms Parker was diagnosed with COPD five years ago. Using Epstein et al’s (2008) guidelines, a nurse took a history from her, which provided 80% of the information needed for a COPD diagnosis; it was then confirmed following spirometry testing as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) guidance.

The nurse used the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model, as it combines the pathological description of COPD with the patient’s subjective experience of the illness (Silverman et al, 2013). Effective communication skills are essential in building a trusting therapeutic relationship, as the quality of the relationship between Ms Parker and the nurse will have a direct impact on the effectiveness of clinical outcomes (Fawcett and Rhynas, 2012).

In a national clinical audit report, Baxter et al (2016) identified inaccurate history taking and inadequately performed spirometry as important factors in the inaccurate diagnosis of COPD on general practice COPD registers; only 52.1% of patients included in the report had received quality-assured spirometry.

Pathophysiology of COPD

Knowing the pathophysiology of COPD allowed the nurse to recognise and understand the physical symptoms and provide effective care (Mitchell, 2015). Continued exposure to tobacco smoke is the likely cause of the damage to Ms Parker’s small airways, causing her cough and increased sputum production. She could also have chronic inflammation, resulting in airway smooth-muscle contraction, sluggish ciliary movement, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting goblet cells, as well as release of inflammatory mediators (Mitchell, 2015).

Ms Parker may also have emphysema, which leads to damaged parenchyma (alveoli and structures involved in gas exchange) and loss of alveolar attachments (elastic connective fibres). This causes gas trapping, dynamic hyperinflation, decreased expiratory flow rates and airway collapse, particularly during expiration (Kaufman, 2013). Ms Parker also displayed pursed-lip breathing; this is a technique used to lengthen the expiratory time and improve gaseous exchange, and is a sign of dynamic hyperinflation (Douglas et al, 2013).

In a healthy lung, the destruction and repair of alveolar tissue depends on proteases and antiproteases, mainly released by neutrophils and macrophages. Inhaling cigarette smoke disrupts the usually delicately balanced activity of these enzymes, resulting in the parenchymal damage and small airways (with a lumen of <2mm in diameter) airways disease that is characteristic of emphysema. The severity of parenchymal damage or small airways disease varies, with no pattern related to disease progression (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2018).

Ms Parker also had a wheeze, heard through a stethoscope as a continuous whistling sound, which arises from turbulent airflow through constricted airway smooth muscle, a process noted by Mitchell (2015). The wheeze, her 29 pack-year score, exertional breathlessness, cough, sputum production and tiredness, and the findings from her physical examination, were consistent with a diagnosis of COPD (GOLD, 2018; NICE, 2018).

Spirometry is a tool used to identify airflow obstruction but does not identify the cause. Commonly measured parameters are:

- Forced expiratory volume – the volume of air that can be exhaled – in one second (FEV1), starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres);

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) – the total volume of air that can be forcibly exhaled – at timed intervals, starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres).

Calculating the FEV1 as a percentage of the FVC gives the forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC). This provides an index of airflow obstruction; the lower the ratio, the greater the degree of obstruction. In the absence of respiratory disease, FEV1 should be ≥70% of FVC. An FEV1/FVC of <70% is commonly used to denote airflow obstruction (Moore, 2012).

As they are time dependent, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC are reduced in diseases that cause airways to narrow and expiration to slow. FVC, however, is not time dependent: with enough expiratory time, a person can usually exhale to their full FVC. Lung function parameters vary depending on age, height, gender and ethnicity, so the degree of FEV1 and FVC impairment is calculated by comparing a person’s recorded values with predicted values. A recorded value of >80% of the predicted value has been considered ‘normal’ for spirometry parameters but the lower limit of normal – equal to the fifth percentile of a healthy, non-smoking population – based on more robust statistical models is increasingly being used (Cooper et al, 2017).

A reversibility test involves performing spirometry before and after administering a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) such as salbutamol; the test is used to distinguish between reversible and fixed airflow obstruction. For symptomatic asthma, airflow obstruction due to airway smooth-muscle contraction is reversible: administering a SABA results in smooth-muscle relaxation and improved airflow (Lumb, 2016). However, COPD is associated with fixed airflow obstruction, resulting from neutrophil-driven inflammatory changes, excess mucus secretion and disrupted alveolar attachments, as opposed to airway smooth-muscle contraction.

Administering a SABA for COPD does not usually produce bronchodilation to the extent seen in someone with asthma: a person with asthma may demonstrate significant improvement in FEV1 (of >400ml) after having a SABA, but this may not change in someone with COPD (NICE, 2018). However, a negative response does not rule out therapeutic benefit from long-term SABA use (Marín et al, 2014).

NICE (2018) and GOLD (2018) guidelines advocate performing spirometry after administering a bronchodilator to diagnose COPD. Both suggest a FEV1/FVC of <70% in a person with respiratory symptoms supports a diagnosis of COPD, and both grade the severity of the condition using the predicted FEV1. Ms Parker’s spirometry results showed an FEV1/FVC of 56% and a predicted FEV1 of 57%, with no significant improvement in these values with a reversibility test.

GOLD (2018) guidance is widely accepted and used internationally. However, it was developed by medical practitioners with a medicalised approach, so there is potential for a bias towards pharmacological management of COPD. NICE (2018) guidance may be more useful for practice nurses, as it was developed by a multidisciplinary team using evidence from systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, providing a holistic approach. NICE guidance may be outdated on publication, but regular reviews are performed and published online.

NHS England (2016) holds a national register of all health professionals certified in spirometry. It was set up to raise spirometry standards across the country.

Assessment and management

The goals of assessing and managing Ms Parker’s COPD are to:

- Review and determine the level of airflow obstruction;

- Assess the disease’s impact on her life;

- Risk assess future disease progression and exacerbations;

- Recommend pharmacological and therapeutic management.

GOLD’s (2018) ABCD assessment tool (Fig 1) grades COPD severity using spirometry results, number of exacerbations, CAT score and mMRC score, and can be used to support evidence-based pharmacological management of COPD.

When Ms Parker was diagnosed, her predicted FEV1 of 57% categorised her as GOLD grade 2, and her mMRC score, CAT score and exacerbation history placed her in group D. The mMRC scale only measures breathlessness, but the CAT also assesses the impact COPD has on her life, meaning consecutive CAT scores can be compared, providing valuable information for follow-up and management (Zhao, et al, 2014).

After assessing the level of disease burden, Ms Parker was then provided with education for self-management and lifestyle interventions.

Lifestyle interventions

Smoking cessation.

Cessation of smoking alongside support and pharmacotherapy is the second-most cost-effective intervention for COPD, when compared with most other pharmacological interventions (BTS and PCRS UK, 2012). Smoking cessation:

- Slows the progression of COPD;

- Improves lung function;

- Improves survival rates;

- Reduces the risk of lung cancer;

- Reduces the risk of coronary heart disease risk (Qureshi et al, 2014).

Ms Parker accepted a referral to an All Wales Smoking Cessation Service adviser based at her GP surgery. The adviser used the internationally accepted ‘five As’ approach:

- Ask – record the number of cigarettes the individual smokes per day or week, and the year they started smoking;

- Advise – urge them to quit. Advice should be clear and personalised;

- Assess – determine their willingness and confidence to attempt to quit. Note the state of change;

- Assist – help them to quit. Provide behavioural support and recommend or prescribe pharmacological aids. If they are not ready to quit, promote motivation for a future attempt;

- Arrange – book a follow-up appointment within one week or, if appropriate, refer them to a specialist cessation service for intensive support. Document the intervention.

NICE (2013) guidance recommends that this be used at every opportunity. Stead et al (2016) suggested that a combination of counselling and pharmacotherapy have proven to be the most effective strategy.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Ms Parker’s positive response to smoking cessation provided an ideal opportunity to offer her pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) – as indicated by Johnson et al (2014), changing one behaviour significantly increases a person’s chance of changing another.

PR – a supervised programme including exercise training, health education and breathing techniques – is an evidence-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary intervention that:

- Improves exercise tolerance;

- Reduces dyspnoea;

- Promotes weight loss (Bolton et al, 2013).

These improvements often lead to an improved quality of life (Sciriha et al, 2015).

Most relevant for Ms Parker, PR has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, which are linked to an increased risk of exacerbations and poorer health status (Miller and Davenport, 2015). People most at risk of future exacerbations are those who already experience them (Agusti et al, 2010), as in Ms Parker’s case. Patients who have frequent exacerbations have a lower quality of life, quicker progression of disease, reduced mobility and more-rapid decline in lung function than those who do not (Donaldson et al, 2002).

“COPD is a major public-health challenge; nurses can be pivotal in early identification, assessment and management”

Pharmacological interventions

Ms Parker has been prescribed inhaled salbutamol as required; this is a SABA that mediates the increase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in airway smooth-muscle cells, leading to muscle relaxation and bronchodilation. SABAs facilitate lung emptying by dilatating the small airways, reversing dynamic hyperinflation of the lungs (Thomas et al, 2013). Ms Parker also uses a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) inhaler, which works by blocking the bronchoconstrictor effects of acetylcholine on M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle; release of acetylcholine by the parasympathetic nerves in the airways results in increased airway tone with reduced diameter.

At a routine review, Ms Parker admitted to only using the SABA and LAMA inhalers, despite also being prescribed a combined inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 -agonist (ICS/LABA) inhaler. She was unaware that ICS/LABA inhalers are preferred over SABA inhalers, as they:

- Last for 12 hours;

- Improve the symptoms of breathlessness;

- Increase exercise tolerance;

- Can reduce the frequency of exacerbations (Agusti et al, 2010).

However, moderate-quality evidence shows that ICS/LABA combinations, particularly fluticasone, cause an increased risk of pneumonia (Suissa et al, 2013; Nannini et al, 2007). Inhaler choice should, therefore, be individualised, based on symptoms, delivery technique, patient education and compliance.

It is essential to teach and assess inhaler technique at every review (NICE, 2011). Ms Parker uses both a metered-dose inhaler and a dry-powder inhaler; an in-check device is used to assess her inspiratory effort, as different inhaler types require different inhalation speeds. Braido et al (2016) estimated that 50% of patients have poor inhaler technique, which may be due to health professionals lacking the confidence and capability to teach and assess their use.

Patients may also not have the dexterity, capacity to learn or vision required to use the inhaler. Online resources are available from, for example, RightBreathe (rightbreathe.com), British Lung Foundation (blf.org.uk). Ms Parker’s adherence could be improved through once-daily inhalers, as indicated by results from a study by Lipson et al (2017). Any change in her inhaler would be monitored as per local policy.

Vaccinations

Ms Parker keeps up to date with her seasonal influenza and pneumococcus vaccinations. This is in line with the low-cost, highest-benefit strategy identified by the British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society UK’s (2012) study, which was conducted to inform interventions for patients with COPD and their relative quality-adjusted life years. Influenza vaccinations have been shown to decrease the risk of lower respiratory tract infections and concurrent COPD exacerbations (Walters et al, 2017; Department of Health, 2011; Poole et al, 2006).

Self-management

Ms Parker was given a self-management plan that included:

- Information on how to monitor her symptoms;

- A rescue pack of antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol;

- A traffic-light system demonstrating when, and how, to commence treatment or seek medical help.

Self-management plans and rescue packs have been shown to reduce symptoms of an exacerbation (Baxter et al, 2016), allowing patients to be cared for in the community rather than in a hospital setting and increasing patient satisfaction (Fletcher and Dahl, 2013).

Improving Ms Parker’s adherence to once-daily inhalers and supporting her to self-manage and make the necessary lifestyle changes, should improve her symptoms and result in fewer exacerbations.

The earlier a diagnosis of COPD is made, the greater the chances of reducing lung damage through interventions such as smoking cessation, lifestyle modifications and treatment, if required (Price et al, 2011).

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive respiratory condition, projected to become the third leading cause of death globally

- Diagnosis involves taking a patient history and performing spirometry testing

- Spirometry identifies airflow obstruction by measuring the volume of air that can be exhaled

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is managed with lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, as well as self-management

Related files

200506 diagnosis and management of copd – a case study.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2023

The patient journey in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): a human factors qualitative international study to understand the needs of people living with COPD

- Nicola Scichilone 1 ,

- Andrew Whittamore 2 ,

- Chris White 3 ,

- Elena Nudo 4 ,

- Massimo Savella 4 &

- Marta Lombardini 4

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 23 , Article number: 506 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common condition that causes irreversible airway obstruction. Fatigue and exertional dyspnoea, for example, have a detrimental impact on the patient’s daily life. Current research has revealed the need to empower the patient, which can result in not only educated and effective decision-making, but also a considerable improvement in patient satisfaction and treatment compliance.

The current study aimed to investigate the perspectives and requirements of people living with COPD to possibly explore new ways to manage their disease.

Adults with COPD from 8 European countries were interviewed by human factor experts to evaluate their disease journey through the gathering of information on the age, performance, length, and impact of diagnosis, symptoms progression, and family and friends' reactions. The assessment of present symptoms, services, and challenges was performed through a 90-min semi-structured interview. To identify possible unmet needs of participants, a generic thematic method was used to explore patterns, themes, linkages, and sequences within the data collected. Flow charts and diagrams were created to communicate the primary findings. Following analysis, the data was consolidated into cohesive insights and conversation themes relevant to determining the patient's unmet needs.

The 62, who voluntarily accepted to be interviewed, were patients (61% females, aged 32–70 years) with a COPD diagnosis for at least 6 months with stable symptoms of different severity. The main challenges expressed by the patients were the impact on their lifestyle, reduced physical activity, and issues with their mobility. About one-fourth had challenges with their symptoms or medication including difficulty in breathing. Beyond finding a cure for COPD was the primary goal for patients, their main needs were to receive adequate information on the disease and treatments, and to have adequate support to improve physical activity and mobility, helpful both for patients and their families.

Conclusions

These results could aid in the creation of new ideas and concepts to improve our patient’s quality of life, encouraging a holistic approach to people living with COPD and reinforcing the commitment to understanding their needs.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by irreversible airway obstruction linked with comorbidities or systemic effects [ 1 ]. COPD is a worldwide epidemic that contributes significantly to healthcare expenses due to high morbidity and mortality rates [ 2 , 3 ]. The clinical assessment of fixed airflow limitation and symptoms such as coughing and wheezing determine a COPD diagnosis; nevertheless, COPD symptoms negatively impact the patient's daily activities and lifestyle [ 4 ]. Patients may encounter a variety of debilitating physical symptoms, resulting in functional loss and high degrees of psychosocial anguish [ 5 , 6 , 7 ].

Integrated approaches to disease assessment and management are required to better understand and address the burden of COPD symptoms from a patient's perspective [ 8 ].

According to a recent observational study, regardless of disease severity, more than half of COPD patients experienced symptoms during the whole 24-h day, and almost 80% of patients reported experiencing symptoms at least twice a day. Symptoms are linked to poor health, depression, anxiety, and poor sleep quality [ 9 , 10 ].

Patients with COPD and comorbidities remain particularly challenging to manage because in Europe there is, generally, no guidance at the national level except in the UK, Slovenia, and Germany [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. In Nordic countries and France, the management of patients with COPD is mainly performed by general practitioners with an inadequate level of assistance [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. In other countries, patient management is performed at the discretion of the local structures, and the need for a comprehensive, holistic approach is looked forward [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Other chronic conditions increase symptom load, impair functional performance, and negatively impact health status; thus, management strategies must be adjusted accordingly [ 10 ].

Care plans, within the healthcare system, emphasize the importance of addressing these patients' particular physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs through holistic supportive input offered as person-centered care [ 21 ]. Understanding the patient's perspective on their support requirements (those areas of living with COPD for which they require assistance, such as help controlling symptoms or accessing financial benefits) is critical to facilitating this approach. A recent systematic literature review has identified a whole range of support needs for COPD patients, based on the perspectives of the patients themselves [ 7 ].

Our human factor study aims to explore how COPD has affected the patients’ daily lives and the lives of those around them, through the assessment of symptoms, treatment, and service availability, identifying what challenges the patient faces in living with COPD, and which are the unmet needs in the different stages of the journey of care.

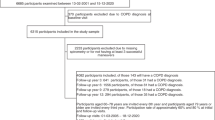

This human factors COPD patient needs study was conducted in November 2022 by an ISO 13485 certified specialist human factors consultant (Rebus Medical Ltd), both in-person or remotely, via video call using the Zoom platform. Remote interviews were needed to enable more severe patients to attend the sessions and to ensure that the intended study sample was achieved. As for other qualitative analyses, a minimum of 48 participants were planned to be interviewed.

Interviews were conducted on a 1–1 basis, with patients who voluntarily accepted to be interviewed from 8 countries: Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. Each interview was 90 min long and followed a semi-structured approach allowing for unscripted discussion when the participants’ responses raised new questions. For interviews that took place outside of the UK, a native-speaking moderator conducted the interview, whilst an interpreter translated the conversation live to a data analyst (Fig. 1 ).

Summary of the study methods. Countries involved in the study are indicated in grey

Participants included in the study, aged 18 years or older, with a current COPD diagnosis, were screened for COPD severity according to GOLD criteria-2020-document [ 22 ] and voluntarily provided their informed consent.

Because the objectives were connected to identifying unmet requirements through video conference, the formative interviews were deemed low to minimal risk to participants and, thus, no formal approval to an Ethical Committee was required.

For interviews conducted in a language other than English, a simultaneous translator was recruited to enable a member of Rebus Medical staff to watch the interview listen to the translation, and record notes. Digital video recordings were collected to accurately account for each test session. Notes were verified at the end of each interview, while participant faces recorded on the videos were blurred to anonymize the footage. When all interviews were complete, the raw notes from each interview were collated and verified using the recorded videos in a master data capture spreadsheet.

The interviews were conducted to evaluate the journey of care through the collection of information on the gender, age, performance, length, and impact of diagnosis, symptoms progression, and family and friends’ reactions through questions that were designed on purpose to identify the unmet need and main challenges of each step of the patient’s journey. The evaluation of the current symptoms (fluctuations, flare-ups, alleviations, effect on sleep and daily activities including the use of electronic devices), services (health care providers support, insurance, available information on COPD), and challenges (in lifestyle, daily activities, treatments, symptoms management, emotional and environmental) was included in the semi-structured interview (Table 1 ).

As this was an exploratory insight interview, protocol deviations like alterations to the interviewer’s script to reformulate questions, ad hoc addition of questions and probes to the interviewer’s script to focus on points of interest specific to each participant, and changes to the interviewer’s script as the study progresses to allow for study learnings were permitted and expected.

A generic thematic approach was employed to uncover patterns, themes, links, and sequences within the data collected to identify probable unmet needs of participants through the patient journey of people living with COPD.

To communicate the major findings, flow charts, and diagrams were constructed. Following analysis, the data were synthesized and refined into cohesive insights and discussion themes pertinent to identifying the patient's unmet needs along the different stages of the patient journey.

A total of 62 patients (38—61% females) with COPD aged between 32 and 70 years ( N = 1 aged 25–40 years, N = 42 aged 41–65 years, N = 19 aged > 65 years) were interviewed. Most of the patients (35—56%) had severe COPD (Table 2 ).

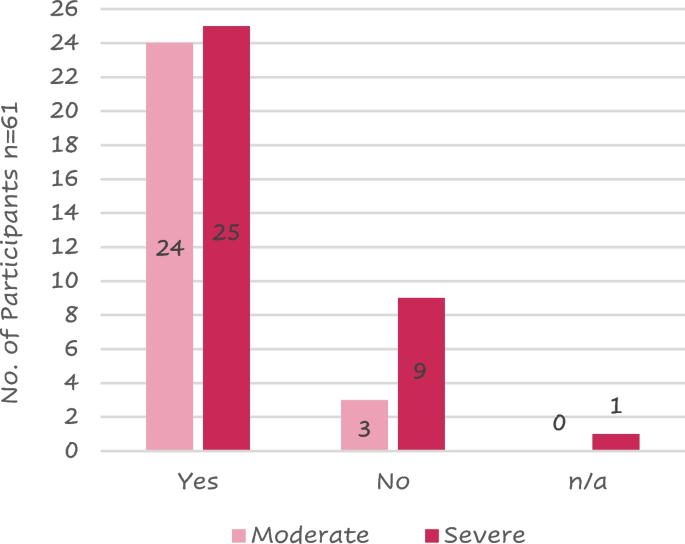

Current- or past smokers were 49 (80%) of the 61 respondents. A larger proportion of patients with severe COPD (9/35, 26%) had never smoked compared to the moderate COPD patient group (3/27, 11%); in fact, 26 (74%) severe patients and 24 (89%) moderate were smokers or had smoked in the past (Fig. 2 ).

Distribution of patients that have ever been a smoker against COPD severity

Legend: n/a = not available

Patient journey

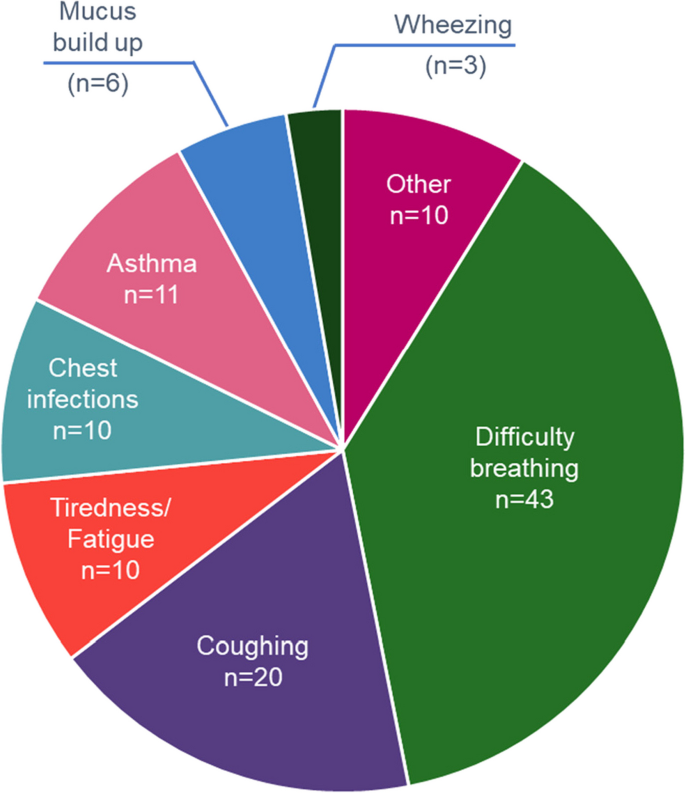

A total of 113 symptoms of COPD were recorded because most patients reported more than 1 symptom at the onset of the disease; 78 (69%) of these symptoms were related to dyspnoea. The highest reported symptoms were difficulty breathing and coughing (Fig. 3 ).

Patient’s reported signs and symptoms leading to COPD diagnosis

Note—Other includes chest tightness, hereditary respiratory issues, persistent flare ups, unable to walk upstairs, difficulty talking, difficulty walking, difficulty swallowing, bronchitis as a child and headaches

Fourteen (30%) of the 46 respondents referred to being diagnosed with COPD more than 1 year after initial symptoms, while 6 (13%) were diagnosed from 7 to 12 months from the onset of symptoms. Ten (64%) of the 14 requiring > 1 year for their diagnosis had severe COPD.

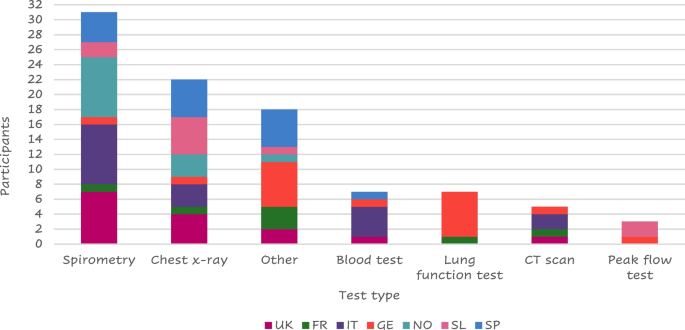

Most of the 56 patients who answered (41 – 73%) were diagnosed by a lung specialist mainly using spirometry (Fig. 4 ).

Tests performed at the visit of diagnosis

Legend: FR = France, GE = Germany, IT = Italy, SL = Slovenia, SP = Spain, NO = Northern (Sweden Denmark), UK = United Kingdom. “Other” includes: MRI, pressure cabin test, swabs collected, endoscope to check lungs, chamber, PET scan, Blood taken from the ear, blood gas test, oxygen saturation, walking/ running tests, echocardiogram, pulse oximeter/O 2 saturation, sleep test

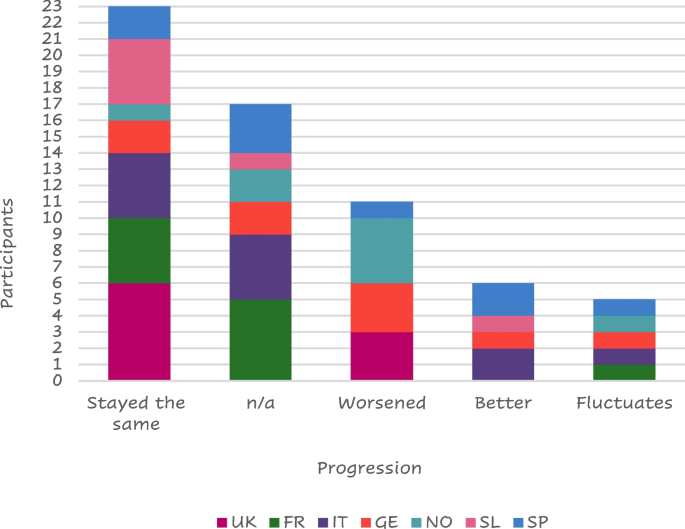

About half of the responders (23 of 45 – 51%) felt their symptoms stable from the diagnosis (Fig. 5 ).

Symptom progression

Legend: FR = France, GE = Germany, IT = Italy, SL = Slovenia, SP = Spain, NO = Northern (Sweden Denmark), UK = United Kingdom, n/a = not available

Thirteen (29%) of those interviewed stated that their family and friends were supportive at the time of COPD diagnosis while 8 (18%) were worried about the diagnosis. Seven of them received no reaction from their family or friends and a further 7 did not tell anyone about their diagnosis. ‘Other’ reactions that were received from family and friends included: acceptance, anger, fear, shock, anguish, and expected, while some patients “prefer not to speak about it”.

The COPD diagnosis hurt 26 (58%) of the responders who described a negative impact of their COPD diagnosis, mainly because of their inability to be active, while 13 of them (29%) felt a positive impact mainly because they stopped or reduced smoking (Table 3 ).

Six (19%) of the 31 patients who provided details on the reason for quitting smoking reported they received more information about how to give up smoking and the risks associated with smoking, 3 patients mentioned some form of medication to support smoking cessation may have helped them give up, and 2 patients reported that they would give up for a family member but would struggle to have the motivation to do it themselves. Three patients reported that nothing would have helped them stop smoking while 8 patients reported that, despite knowing the impact smoking has, they still chose to smoke. Other suggestions to stop smoking reported by participants included: the threat of death, vaping if the smoking affected their fitness, cigarettes stopped being sold, stopping because of asthma and its diagnosis, quitting when they were in the hospital for a week giving it up after then, or because the smell was horrible.

A total of 59 patients answered about their changes in symptoms throughout the day; seventeen (29%) felt no changes while 13 (22%) worsened in the morning, 11 (19%) worsened at night, and 6 (10%) worsened both in the morning and at night.

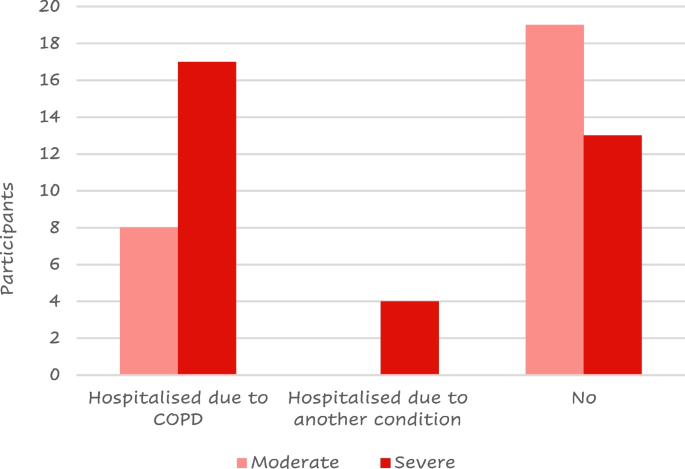

Twenty-five (41%) of the 61 responders were hospitalized due to a COPD flare-up at least once after their COPD diagnosis; most of them had severe disease (Fig. 6 ).

Number of patients that have experienced a COPD flare-up by COPD severity

Seven (30%) of the 23 patients who took any action to alleviate their symptoms, before seeing a doctor and getting a diagnosis, reduced their physical exercise to not trigger symptoms. While others were more vigilant with their health, received help from family and friends, or used inhalers, a rescue pack, or menthol sweets.

Thirty seven out of 58 participants reported sleep disruption. Of these, 12 (32%), reported disruption due to COPD while 10 (17%) had sleep negatively affected by another condition. Other causes for patients’ sleep disruption included coughing, the need to change sleeping positions, and cold weather.

Patients reported needing more support including more information about their condition, financial support for transportation, improved treatment options, accessibility badges, and help in carrying out chores in the house such as cooking, cleaning, and general housekeeping. Some patients also indicated a wish for personal training. Some patients were unaware of what type of support they may require or what type of support could be available to them while others were looking for a different inhaler or treatment to alleviate their cough or a device that assists deep breathing, transplant, a dog or a sport requiring a limited physical effort that would help them be more active, and/or meeting a COPD support group.

About half of the respondents (26/56 – 46%) used electronic devices to monitor their health status including a finger pulse oximeter ( n = 9), smartwatch ( n = 8), or a blood pressure cuff ( n = 5).

A total of 64 responses were collected from the 58 patients who shared their opinion on the treatment they were utilizing; 33 (52%) of the feedback was positive (Table 4 ).

While 20 (31%) of the respondents felt neutral about their current prescribed treatment, 11 (17%) reported either that their medicine had "no therapeutic impact", that they faced "psychological restraint" with their prescribed regime, or that they had issues with treatment compliance.

Six (12%) of the 52 respondents confirmed using digital or analogic reminders to take their dose. Three patients were currently using a dose counter on their device to remind them if their doses had not been taken, and two patients were using a timer on their mobile phones to remind them when their next dose was due. One participant used digital/analogic support but did not indicate which.

The main strategies used to remind them to take their medication include:

leaving the medication in a specific location to prompt them to take their dose at the correct time,

relying on habit or routine to prompt them to take their medication,

taking the COPD medication at the same time as other medications,

feeling unwell to prompt themselves to take their medication.

A total of 32 (56%) of the 57 respondents reported missing a medicine dose; eight of them cited a change in their schedule or routine as its cause. Other reasons for missing a dose reported by patients included: not taking the medication seriously, forgetting to take their dose in the evening, forgetting to bring their medication with them when leaving the house, a change in their environment, a missed medication delivery, and “not taking regular doses”.

The primary reasons why patients appreciate their present treatments were the drug's functionality ( n = 18), the device design ( n = 10), the convenience of use ( n = 8), and the medication's quick and uncomplicated administration ( n = 5). Other patients expressed liking for current medication including feeling comfortable with their present treatment, feeling in charge, and independence.

On the other hand, the device design ( n = 14), the necessity to take their medication ( n = 8), and the side effects of the drug ( n = 5) were the most reported characteristics that patients disliked therapy. Other reported reasons included uncertainty about what the treatment is supposed to do, a sense of guilt when their medication is forgotten, the fact that they are still limited in their activity, and the sensation or taste inside their mouth. Three patients stated that they did not enjoy their current prescribed treatment. "You have to accept what is available," one patient said. Other patients referred detest having to take their medications daily.

About two-thirds ( n = 34 – 67%) of those polled ( n = 51) claimed no involvement with the selection of their present treatment option.

Most of the patients ( n = 42 – 69% of the 61 respondents) reported receiving training for the use of their current treatment. The remaining 31% of the patients did not receive any training, reporting that they “would have liked more formal training, the current device is more complex”, or believed it “could have been useful to receive training and would have loved the explanation, demo training”. Three patients also stated that they did not need training, whether they received it or not.

Twenty-two (52%) of the 42 patients that received training, thought that it was effective and only 5 (12%) did not believe their training to be effective. Fifteen (36%) of patients who received training did not provide feedback on the efficacy of the training they received.

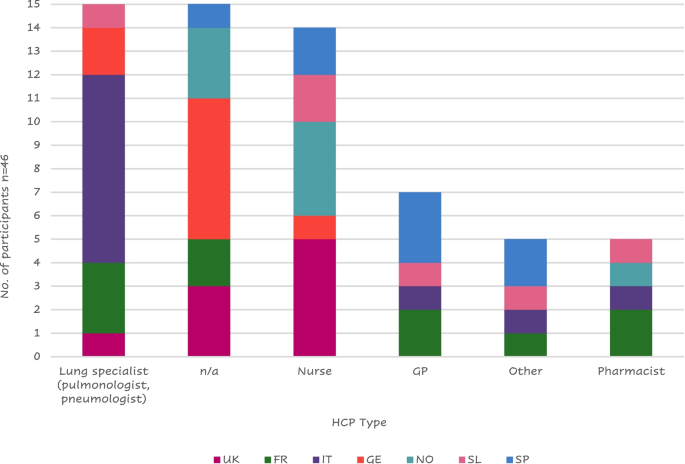

Eight Italian patients reported receiving instruction mostly from a lung specialist, while the majority of British ( n = 5) and Nordic ( n = 4) patients reported receiving training primarily from a nurse (Fig. 7 ); this is probably due to the different structures of the national health systems.

Health care provider (HCP) that administered training to patients by country

Legend: FR = France, GE = Germany, GP = General Practitioner; IT = Italy, SL = Slovenia, SP = Spain, n/a = not applicable; NO = Northern (Sweden Denmark), UK = United Kingdom

One Italian patient stated he received no specific training but was told by his pneumologist to look inside the package and read the instructions; a Frenchman mentioned that his wife was a doctor, so she just showed him how to use the device. Other participants’ training was received at meetings of a lung association from the pharmacists or at a live course organized by the doctor or during rehabilitation.

Six (18% of the 34 respondents) received help from their family or friends to find training materials or treatment information. Most patients received help to find further information and one participant mentioned that he was able to speak to a relative with COPD.

Six (15%) of the 41 respondents had gone online for help with their equipment (looking for tutorials online on forums and finding animated videos on how to use their inhalers). The main reasons for not using the internet for support were a lack of trust in online information ("would rather trust a doctor than go online"), an unwillingness to read more about their condition due to a fear of "reading too much" and becoming "depressed" if they investigated their disease. Other patients did not feel the need for additional support from the internet because their devices were "easy to use" or they wouldn't need further support due to their disease. One patient stated that he looked online and "found it strange that the messages were exclusively for persons with moderate to severe COPD, with only a few messages from people with mild COPD".

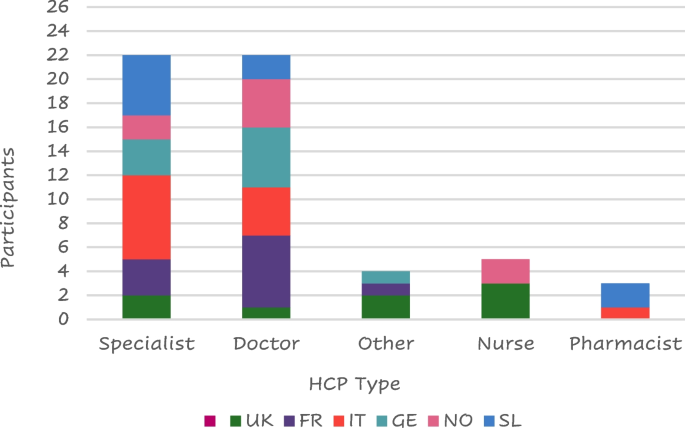

Lung specialists were the health care providers (HCPs) who most frequently provided support to patients with COPD ( n = 24/60—40%) followed by general practitioners (23 – 38%) (Fig. 8 ); only 3 patients reported not having received any support.

Type of HCP support by country

Legend: FR = France, GE = Germany, IT = Italy, SL = Slovenia, SP = Spain, NO = Northern (Sweden Denmark), UK = United Kingdom

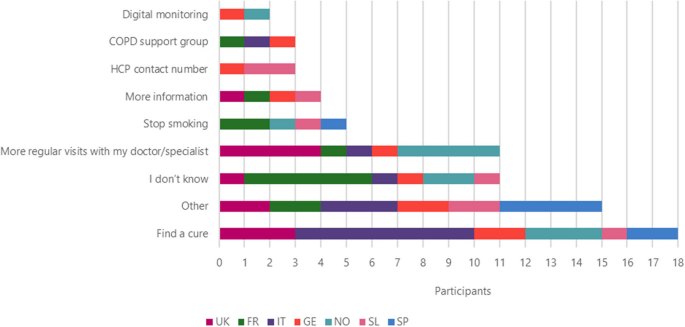

The most frequent answers to the question “If you had a magic wand what would you wish for to improve your life with COPD?” were to find a cure ( n = 18), followed by more regular visits from their doctor/specialist ( n = 11), stop smoking ( n = 5), more information ( n = 4), HCP contact number and COPD support group ( n = 3), and digital monitoring ( n = 2) (Fig. 9 ).

Improvements that patients wish to be made to improve their life by country

Other improvements that patients wish for include: access to new drugs, information about COPD, current and new drugs, reduced side effects, holding COPD workshops, investment in more research, provide cheaper treatment options, new lungs, something to help be more active, to be told that they would not need to take medication anymore, a new type of drug delivery that wouldn’t need to be taken with patient everywhere (like a nicotine patch), instant relief and doctors and nurses to be more humane.

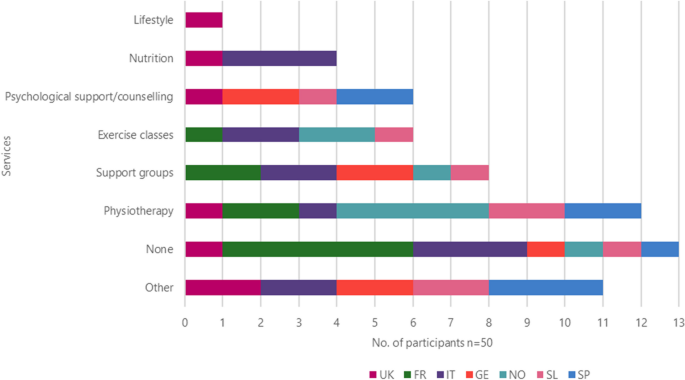

Other services they felt were useful for them included physiotherapy ( n = 12), the use of support groups ( n = 8), exercise classes and psychological assistance ( n = 6), nutrition ( n = 4) while 1 patient from the UK suggested lifestyle (Fig. 10 ).

Other services the patient would like to use by country

Other services that patients would like to use included easier access to their HCP, paid, private physiotherapy sessions, smoking cessation support, disability card, training (videos and tutorials) including emergencies, lung transplants, more information about new drugs and the benefits of medication, hear more from doctors and pharmacists, and workshops for families and friends to help them understand what patients are going through.

Even if 3 patients reported having insurance covering additional services, they were generally unaware of the support they could receive through medical insurance. Many had concerns that such services would cost more money.

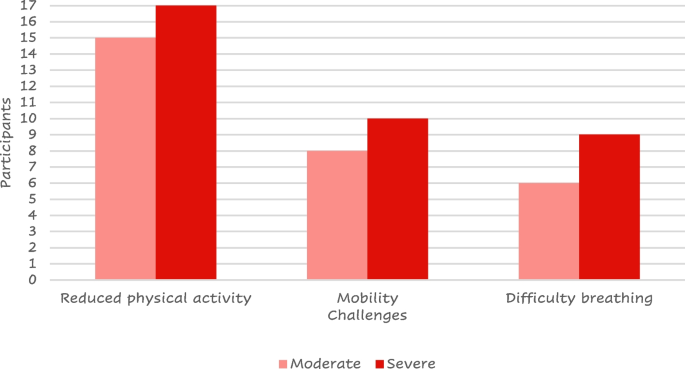

All the patients included in the study provided a total of 122 daily challenges they must face. 53 (43%) of the responses were related to their lifestyle. Reduced physical activity was referred by more than half ( n = 32) of them and difficulty in mobility was reported by 16; 28 (23%) reported challenges with their symptoms or medication (mainly difficult breathing, n = 15) (Fig. 11 ) while 13 (11%) reported emotional challenges including anxiety, depression, embarrassment due to symptoms or treatment, fear of the conditioning worsening, people recognizing they have a condition, acceptance of the condition and dependence on the medication.

Most reported challenges by COPD severity

The objective of this human factors research was to identify the unmet needs along the different stages of people living with COPD through a one-to-one, semi-structured interview exploring the patient’s feelings and attitudes toward their journeys with the disease.

Differently from other studies exploring similar aspects of the impact of the disease on patient’s daily life where the data belong to medical databases, [ 4 , 6 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 23 ] the current approach is unique, in that it systematically investigates the patient’s feelings in a structured fashion, thus allowing us to better understand the patient’s emotions, which is becoming a relevant aspect of COPD management [ 7 , 24 ]. Furthermore, because of the consistent and wide heterogeneity between the different countries, patients included in this study could have been considered representative of the entire population of European patients with COPD.

The patient reported feelings highlighted that reduced physical activity, mobility challenges, and difficulty breathing resulted as the main challenges in daily life. According to the current international guidelines on COPD management, [ 22 , 25 , 26 ] physical activity is encouraged and monitored to evaluate the prognosis or looked forward to as a target for the evaluation of the treatment efficacy. [ 25 ] Our results confirm that patients perceive COPD as the cause of their reduced physical activity, [ 27 ] having a strong impact on their self-perception. Differently from other studies where increased physical activity was observed independently from patients’ counseling, [ 28 ] general psychological support and accepting their mobility challenges were described as important aims by the patients. Our patients felt reduced mobility as one of their main challenges; aids to improve mobility were described in the available literature as crucial to maintaining the patient’s independence [ 7 ] and have been included in the 2023 GOLD guidelines [ 29 ].

The HCP approach is mainly focused on improving the patient’s breathlessness and exercise intolerance [ 22 , 25 ]; the feeling depicted by the interviewed patients confirms the lack of information about how to manage breathlessness. [ 30 ] The only positive aspect of the COPD diagnosis, reported by 6 of the interviewees, was smoke quitting. Patients frequently feel angry and depressed when they think about the difficulties they have described. Participants discussed a variety of coping mechanisms to deal with these difficulties, including cutting back on physical activity, making sure they stayed active (as much as possible), and utilizing their rescue inhaler as a preventative step.

About one-fourth of the patients did not report having performed spirometry at diagnosis; as spirometry is the landmark of diagnosis; any other method is not gold standard and subjected to criticism [ 22 ]. Because of the qualitative nature of this study, we cannot exclude that this issue was linked to the patient’s reduced memory at the time of diagnosis.

As observed in other studies, [ 31 ] negative behavior has a strong influence on the patient’s quality of life. Patients in the current study generally felt negative emotions before receiving their diagnosis; however, a supportive role of relatives and caregivers was referred by interviewed subjects at the time of diagnosis. About forty percent of patients complained of having waited long before the diagnosis. When asked about the impact of their current treatment, participants gave primarily positive feedback and commonly described their current therapy as “good” and doing its job. Even if most of the patients included in our study felt stable symptoms, some were still looking for a “miraculous” cure. The need for support beyond just pharmacological treatments, such as psychological support and physiotherapy, became clear through the in-depth discussions with patients, confirming the requirement for an integrated and patient-tailored interview to identify the profile of each patient [ 27 , 32 ] to share the most appropriate interventions in the periodic visits, without the need of the patient’s hospitalizations to allow the introduction of new therapies suggested by other research [ 33 ].

As expected, our results show that the information about COPD and the training on both the disease and treatment were provided by different HCPs in various European countries. However, patients often felt that they were not provided with enough information at the point of diagnosis regarding the condition itself or the range of treatment options available. Some felt they did not receive adequate training on how to take their medication correctly, whereas others highlighted that the public should be made more aware of the condition, in general, to help them feel accepted and understood by their family and friends. When asked about the current support they were receiving for their disease, patients reported wanting more information about their clinical condition or treatment options, more regular visits with their HCP, smoking cessation assistance, and support in their day-to-day lives such as housework and improved accessibility, confirming the need of self-management education and skills training highlighted by other authors [ 22 , 25 , 26 ]. However, many patients were unsure or unaware of what support/services were available to them or did not feel they needed any additional support.

This study had a qualitative approach and was, thus, not designed to provide any definitive answer to a study hypothesis. Differently from other studies on general populations of patients with COPD where males and elderly are the most frequent patients [ 34 , 35 ], those who agreed to participate in this study were mostly women and aged between 42 and 65 years. Due to the inclusion of patients that could not be fully representative of the global patients with COPD and the study approach, the outcomes have to be properly generalized. Furthermore, the nature of the study required interviews to be carried out in the participant’s local language with the use of translators to support analysis leading to a potential loss of nuance in meaning.

In conclusion, the current findings show that an apparent discrepancy exists between the traditional lung functional and pharmacological approaches in diagnosing and managing COPD and patient’s needs and challenges in daily activities. In this respect, human factor studies play a relevant role in intercepting gaps in the care of people suffering from COPD, encouraging a novel holistic approach when designing clinical research or shepherding patients along their COPD daily journey.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Chris White (Rebus Medical), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are not available without permission of Chiesi Farmaceutici.

Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012 [cited 2023 May 29];379(9823):1341–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22314182/ .

Roggeri A, Micheletto C, Roggeri DP. Outcomes and costs of treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with inhaled fixed combinations: the Italian perspective of the PATHOS study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014 Jun 5 [cited 2023 May 29];9:569–76. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24940053/ .

Blasi F, Cesana G, Conti S, Chiodini V, Aliberti S, Fornari C, et al. The clinical and economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cohort of hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2014 Jun 27 [cited 2023 May 29];9(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24971791/ .

Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PMA, Pride NB, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002 Oct 1 [cited 2023 May 29];20(4):799–805. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12412667/ .

Sundh J, Ekström M. Persistent disabling breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016 Nov 9 [cited 2023 May 29];11(1):2805–12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27877034/ .

Ouellette DR, Lavoie K. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of cognitive and psychiatric disorders in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017 Feb [cited 2023 May 29];12:639–50. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28243081/ .

Gardener AC, Ewing G, Kuhn I, Farquhar M. Support needs of patients with COPD: a systematic literature search and narrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018 Mar 26 [cited 2023 May 29];13:1021–35. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29628760/ .

Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, Zu Wallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Oct 15 [cited 2023 May 29];188(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24127811/ .

Miravitlles M, Worth H, Soler Cataluña JJ, Price D, De Benedetto F, Roche N, et al. Observational study to characterise 24-hour COPD symptoms and their relationship with patient-reported outcomes: results from the ASSESS study. Respir Res. 2014 Oct 21 [cited 2023 May 29];15(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25331383/ .

Jones PW, Watz H, Wouters FM, Cazzola M, COPD: the patient perspective. cited 2023 May 29. Available from: 2016. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S85977 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Škrgat S, Triller N, Košnik M, Susič TP, Petek D, Jamšek VV, et al. Priporočila za obravnavo bolnika s kronično obstruktivno pljučno boleznijo na primarni in specialistični pulmološki ravni v Sloveniji. Zdravniski Vestnik. 2017;86(1–2):1–12.

Google Scholar

Mehring M, Donnachie E, Fexer J, Hofmann F, Schneider A. Disease management programs for patients with COPD in Germany: a longitudinal evaluation of routinely collected patient records. Respir Care. 2014 [cited 2023 Nov 15];59(7):1123–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24222706/ .

Overview | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE. [cited 2023 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115 .

Molin KR, Søndergaard J, Lange P, Egerod I, Langberg H, Lykkegaard J. Danish general practitioners’ management of patients with COPD: a nationwide survey. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020 [cited 2023 Nov 15];38(4):391–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33164618/ .

Sandelowsky H, Natalishvili N, Krakau I, Modin S, Ställberg B, Nager A. COPD management by Swedish general practitioners – baseline results of the PRIMAIR study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2018 Jan 2 [cited 2023 Nov 15];36(1):5. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5901441/.

Meeraus W, Wood R, Jakubanis R, Holbrook T, Bizouard G, Despres J, et al. COPD treatment pathways in France: a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record data from general practitioners. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018 Dec 18 [cited 2023 Nov 15];14:51–63. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/copd-treatment-pathways-in-france-a-retrospective-analysis-of-electron-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-COPD .

Come migliorare la qualità di vita dei pazienti colpiti da bronco-pneumopatia cronica e dei loro caregiver? | Azienda Ospedaliera Nazionale SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo Alessandria. [cited 2023 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.ospedale.al.it/it/comunicazione/notizie/come-migliorare-qualita-vita-pazienti-colpiti-bronco-pneumopatia-cronica-loro-caregiver .