Frequently asked questions

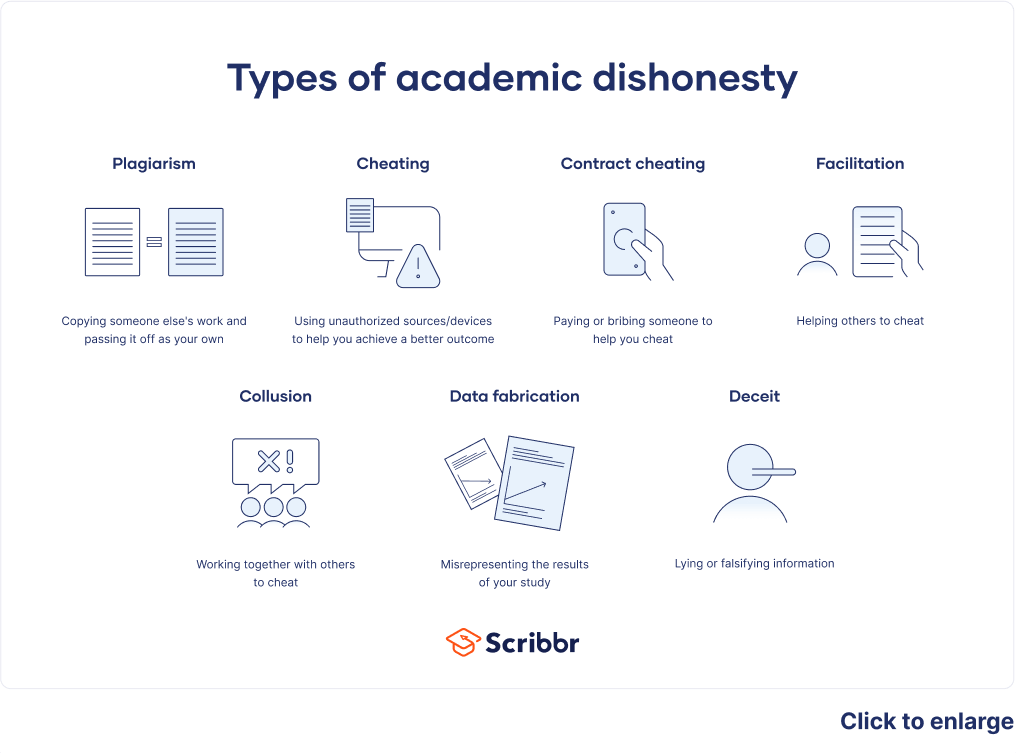

What is academic dishonesty.

Academic dishonesty refers to deceitful or misleading behavior in an academic setting. Academic dishonesty can occur intentionally or unintentionally, and varies in severity.

It can encompass paying for a pre-written essay, cheating on an exam, or committing plagiarism . It can also include helping others cheat, copying a friend’s homework answers, or even pretending to be sick to miss an exam.

Academic dishonesty doesn’t just occur in a classroom setting, but also in research and other academic-adjacent fields.

Frequently asked questions: Plagiarism

Academic integrity means being honest, ethical, and thorough in your academic work. To maintain academic integrity, you should avoid misleading your readers about any part of your research and refrain from offenses like plagiarism and contract cheating, which are examples of academic misconduct.

Plagiarism is a form of theft, since it involves taking the words and ideas of others and passing them off as your own. As such, it’s academically dishonest and can have serious consequences .

Plagiarism also hinders the learning process, obscuring the sources of your ideas and usually resulting in bad writing. Even if you could get away with it, plagiarism harms your own learning.

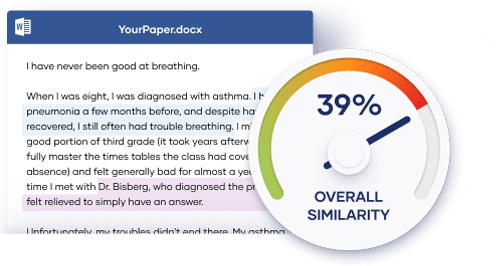

Most online plagiarism checkers only have access to public databases, whose software doesn’t allow you to compare two documents for plagiarism.

However, in addition to our Plagiarism Checker , Scribbr also offers an Self-Plagiarism Checker . This is an add-on tool that lets you compare your paper with unpublished or private documents. This way you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarized or self-plagiarized .

Compare two sources for plagiarism

Most institutions have an internal database of previously submitted student papers. Turnitin can check for self-plagiarism by comparing your paper against this database. If you’ve reused parts of an assignment you already submitted, it will flag any similarities as potential plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers don’t have access to your institution’s database, so they can’t detect self-plagiarism of unpublished work. If you’re worried about accidentally self-plagiarizing, you can use Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker to upload your unpublished documents and check them for similarities.

Yes, reusing your own work without acknowledgment is considered self-plagiarism . This can range from re-submitting an entire assignment to reusing passages or data from something you’ve turned in previously without citing them.

Self-plagiarism often has the same consequences as other types of plagiarism . If you want to reuse content you wrote in the past, make sure to check your university’s policy or consult your professor.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself just as you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for that source type in the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing your previous work can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your professor or consult your university’s handbook before doing so.

Common knowledge does not need to be cited. However, you should be extra careful when deciding what counts as common knowledge.

Common knowledge encompasses information that the average educated reader would accept as true without needing the extra validation of a source or citation.

Common knowledge should be widely known, undisputed and easily verified. When in doubt, always cite your sources.

Plagiarism has serious consequences , and can indeed be illegal in certain scenarios.

While most of the time plagiarism in an undergraduate setting is not illegal, plagiarism or self-plagiarism in a professional academic setting can lead to legal action, including copyright infringement and fraud. Many scholarly journals do not allow you to submit the same work to more than one journal, and if you do not credit a co-author, you could be legally defrauding them.

Even if you aren’t breaking the law, plagiarism can seriously impact your academic career. While the exact consequences of plagiarism vary by institution and severity, common consequences include: a lower grade, automatically failing a course, academic suspension or probation, or even expulsion.

Accidental plagiarism is one of the most common examples of plagiarism . Perhaps you forgot to cite a source, or paraphrased something a bit too closely. Maybe you can’t remember where you got an idea from, and aren’t totally sure if it’s original or not.

These all count as plagiarism, even though you didn’t do it on purpose. When in doubt, make sure you’re citing your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

Self-plagiarism means recycling work that you’ve previously published or submitted as an assignment. It’s considered academic dishonesty to present something as brand new when you’ve already gotten credit and perhaps feedback for it in the past.

If you want to refer to ideas or data from previous work, be sure to cite yourself.

If you’re concerned that you may have self-plagiarized, Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker can help you turn in your paper with confidence. It compares your work to unpublished or private documents that you upload, so you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarized.

Incremental plagiarism means inserting quotes, passages, or excerpts from other works into your assignment without properly citing the original source.

Even if the vast majority of the text is yours, including any content that isn’t without citing it is plagiarism.

Consider using a plagiarism checker yourself before submitting your work. Plagiarism checkers work by scanning your document, comparing it to a database of webpages and publications, and highlighting passages that appear similar to other texts.

Patchwork plagiarism (aka mosaic plagiarism) means copying phrases, passages, or ideas from various existing sources and combining them to create a new text. While this type of plagiarism is more insidious than simply copy-pasting directly from a source, plagiarism checkers like Turnitin’s can still easily detect it.

To avoid plagiarism in any form, remember to cite your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Verbatim plagiarism means copying text from a source and pasting it directly into your own document without giving proper credit.

Even if you delete a few words or replace them with synonyms, it still counts as verbatim plagiarism.

To use an author’s exact words, quote the original source by putting the copied text in quotation marks and including an in-text citation .

If you’re worried about plagiarism, consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Global plagiarism means taking an entire work written by someone else and passing it off as your own. This can mean getting someone else to write an essay or assignment for you, or submitting a text you found online as your own work.

Global plagiarism is the most serious type of plagiarism because it involves deliberately and directly lying about the authorship of a work. It can have severe consequences .

To ensure you aren’t accidentally plagiarizing, consider running your work through plagiarism checker tool prior to submission. These tools work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Plagiarism can be detected by your professor or readers if the tone, formatting, or style of your text is different in different parts of your paper, or if they’re familiar with the plagiarized source.

Many universities also use plagiarism detection software like Turnitin’s, which compares your text to a large database of other sources, flagging any similarities that come up.

It can be easier than you think to commit plagiarism by accident. Consider using a plagiarism checker prior to submitting your paper to ensure you haven’t missed any citations.

Some examples of plagiarism include:

- Copying and pasting a Wikipedia article into the body of an assignment

- Quoting a source without including a citation

- Not paraphrasing a source properly, such as maintaining wording too close to the original

- Forgetting to cite the source of an idea

The most surefire way to avoid plagiarism is to always cite your sources . When in doubt, cite!

If you’re concerned about plagiarism, consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission. Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

Plagiarism means presenting someone else’s work as your own without giving proper credit to the original author. In academic writing, plagiarism involves using words, ideas, or information from a source without including a citation .

Plagiarism can have serious consequences , even when it’s done accidentally. To avoid plagiarism, it’s important to keep track of your sources and cite them correctly.

Academic dishonesty can be intentional or unintentional, ranging from something as simple as claiming to have read something you didn’t to copying your neighbor’s answers on an exam.

You can commit academic dishonesty with the best of intentions, such as helping a friend cheat on a paper. Severe academic dishonesty can include buying a pre-written essay or the answers to a multiple-choice test, or falsifying a medical emergency to avoid taking a final exam.

Consequences of academic dishonesty depend on the severity of the offense and your institution’s policy. They can range from a warning for a first offense to a failing grade in a course to expulsion from your university.

For those in certain fields, such as nursing, engineering, or lab sciences, not learning fundamentals properly can directly impact the health and safety of others. For those working in academia or research, academic dishonesty impacts your professional reputation, leading others to doubt your future work.

Paraphrasing without crediting the original author is a form of plagiarism , because you’re presenting someone else’s ideas as if they were your own.

However, paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you correctly cite the source . This means including an in-text citation and a full reference, formatted according to your required citation style .

As well as citing, make sure that any paraphrased text is completely rewritten in your own words.

Plagiarism means using someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own. Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas in your own words.

So when does paraphrasing count as plagiarism?

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if you don’t properly credit the original author.

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if your text is too close to the original wording (even if you cite the source). If you directly copy a sentence or phrase, you should quote it instead.

- Paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you put the author’s ideas completely in your own words and properly cite the source .

Try our services

If you’ve properly paraphrased or quoted and correctly cited the source, you are not committing plagiarism.

However, the word correctly is vital. In order to avoid plagiarism , you must adhere to the guidelines of your citation style (e.g. APA or MLA ).

You can use the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker to make sure you haven’t missed any citations, while our Citation Checker ensures you’ve properly formatted your citations in APA style.

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offense or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarizing seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

- MC3 Library

Academic Honesty and Avoiding Plagiarism

What is academic dishonesty.

- Introduction

- What is Plagiarism?

- What is Citation?

- When Do You Need to Cite?

- What Citation Style Do I Use?

- Citation in speeches and presentations

- To Cite or Not Cite? That is the Question!

Example #1: Cheating

Example #2: collusion, example #3: falsifying results & misrepresenting, why do students commit academically dishonest acts.

- How Do I Avoid Academic Dishonesty?

- What are the Consequences of Academic Dishonesty?

- Test Your Knowledge

- Questions? Ask a Librarian!

Plagiarism is a type of academic dishonesty. In all academic work, students are expected to submit materials that are their own and are to include attribution for any ideas or language that are not their own.

Additional examples of dishonest conduct include, but are not limited to:

- Cheating including giving and receiving information in examinations.

- Falsification of data, results or sources.

- Collusion, such as working with another person when independent work is assigned.

- Submitting the same paper or report for assignments in more than one course without permission (self-plagiarism).

Cheating is the most well-known academically dishonest behavior.

But cheating includes more than just copying a neighbor’s answers on an exam or peeking at a cheat sheet or storing answers on your phone. Giving or offering information in examinations is also dishonest.

Turning in someone else’s work as your own is also considered cheating.

Ed Dante (a pseudonym) makes a living writing custom essays that unscrupulous students buy online. You can read his story at The Chronicle of Higher Education . Purchasing someone else’s work and turning it in as your own is cheating.

Collusion , such as working with another person or persons when independent work is assigned is considered academically dishonesty.

While it is fine to work in a team if your faculty member specifically requires or allows it, be sure to communicate with your faculty about guidelines on permissible collaboration (including how to attribute the contributions of others).

In 2012, 125 Harvard students were investigated for working together on a take-home final exam. The only rule on the exam was not to work together. Almost half of those students were determined to have cheated, and forced to withdraw from school for a year.

Falsifying results in studies or experiments is a serious breach of academic honesty.

Students are sometimes tempted to make up results if their study or experiment does not produce the results they hoped for. But getting caught has major consequences.

Misrepresenting yourself or your research is, by definition, dishonest.

Misrepresentation might include inflating credentials, claiming that a study proves something that it does not, or leaving out inconvenient and/or contradictory results.

An undergraduate at the University of Kansas claimed to be a researcher and promoted his (unfortunately incorrect) research on how much a Big Mac would cost if the U.S. raised minimum wage. His study was picked up by the Huffington Post, NY Times, and other major news outlets, who then had to publish retractions.

PRESSURE & OPPORTUNITIES

Pressure is the most common reason students act dishonestly. Situations include students feeling in danger of failing a course, financial pressure and fear of losing parental approval (Malgwi and Rakovski 14).

Opportunities to cheat also influence students to act dishonestly including friends sharing information, the ease of storing information on devices, and lack of supervision in the classroom (Malgwi and Rakovski 14).

Malgwi, Charles A., and Carter Rakovski. " Behavioral Implications of Evaluating Determinants of Academic Fraud Risk Factors ." Journal of Forensic & investigative Accounting, vol. 1, no. 2, 2009, pp. 1-37. (pdf file)

- << Previous: To Cite or Not Cite? That is the Question!

- Next: How Do I Avoid Academic Dishonesty? >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 2:52 PM

- URL: https://library.mc3.edu/plagiarism

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Academic Integrity

Responsible research and writing habits

Generative ai (artificial intelligence).

- Using Sources and AI

- Academic Writing

- From Research to Writing

- GSD Writing Services

- Grants and Fellowships

- Reading, Notetaking, and Time Management

- Theses and Dissertations

Need Help? Be in Touch.

- Ask a Design Librarian

- Call 617-495-9163

- Text 617-237-6641

- Consult a Librarian

- Workshop Calendar

- Library Hours

Central to any academic writing project is crediting (or citing) someone else' words or ideas. The following sites will help you understand academic writing expectations.

Academic integrity is truthful and responsible representation of yourself and your work by taking credit only for your own ideas and creations and giving credit to the work and ideas of other people. It involves providing attribution (citations and acknowledgments) whenever you include the intellectual property of others—and even your own if it is from a previous project or assignment. Academic integrity also means generating and using accurate data.

Responsible and ethical use of information is foundational to a successful teaching, learning, and research community. Not only does it promote an environment of trust and respect, it also facilitates intellectual conversations and inquiry. Citing your sources shows your expertise and assists others in their research by enabling them to find the original material. It is unfair and wrong to claim or imply that someone else’s work is your own.

Failure to uphold the values of academic integrity at the GSD can result in serious consequences, ranging from re-doing an assignment to expulsion from the program with a sanction on the student’s permanent record and transcript. Outside of academia, such infractions can result in lawsuits and damage to the perpetrator’s reputation and the reputation of their firm/organization. For more details see the Academic Integrity Policy at the GSD.

The GSD’s Academic Integrity Tutorial can help build proficiency in recognizing and practicing ways to avoid plagiarism.

- Avoiding Plagiarism (Purdue OWL) This site has a useful summary with tips on how to avoid accidental plagiarism and a list of what does (and does not) need to be cited. It also includes suggestions of best practices for research and writing.

- How Not to Plagiarize (University of Toronto) Concise explanation and useful Q&A with examples of citing and integrating sources.

This fast-evolving technology is changing academia in ways we are still trying to understand, and both the GSD and Harvard more broadly are working to develop policies and procedures based on careful thought and exploration. At the moment, whether and how AI may be used in student work is left mostly to the discretion of individual instructors. There are some emerging guidelines, however, based on overarching values.

- Always ask first if AI is allowed and specifically when and how.

- Always check facts and sources generated by AI as these are not reliable.

- Cite your use of AI to generate text or images. Citation practices for AI are described in Using Sources and AI.

Since policies are changing rapidly, we recommend checking the links below often for new developments, and this page will continue to update as we learn more.

- Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) from HUIT Harvard's Information Technology team has put together this webpage explaining AI and curating resources about initial guidelines, recommendations for prompts, and recommendations of tools with a section specifically on image-based tools.

- Generative AI in Teaching and Learning at the GSD The GSD's evolving policies, information, and guidance for the use of generative AI in teaching and learning at the GSD are detailed here. The policies section includes questions to keep in mind about privacy and copyright, and the section on tools lists AI tools supported at the GSD.

- AI Code of Conduct by MetaLAB A Harvard-affiliated collaborative comprised of faculty and students sets out recommendations for guidelines for the use of AI in courses. The policies set out here are not necessarily adopted by the GSD, but they serve as a good framework for your own thinking about academic integrity and the ethical use of AI.

- Prompt Writing Examples for ChatGPT+ Harvard Libraries created this resource for improving results through crafting better prompts.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Using Sources and AI >>

- Last Updated: Jun 24, 2024 11:19 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Staff Directory

- Workshops and Events

- For Students

Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem

by Thomas Keith | Feb 16, 2022 | Instructional design , Services

The Aims of This Series

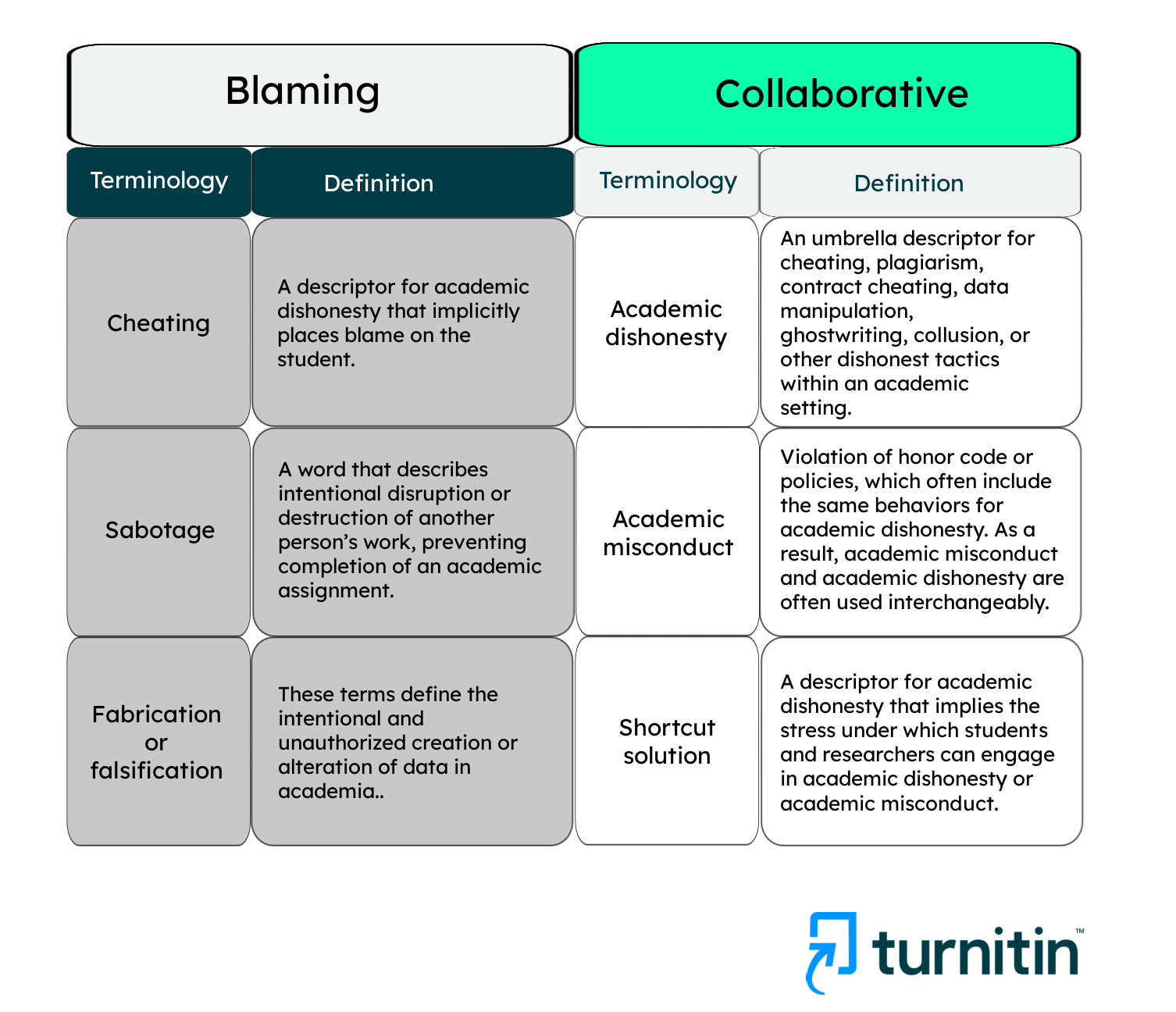

Academic dishonesty – a term that encompasses a wide range of behaviors, from unauthorized collaboration and falsifying bibliographies to cheating on exams and buying pre-written essays – is a serious problem for higher education. Left unchecked, academic dishonesty can damage the culture of integrity that colleges and universities seek to promote, and it can even undermine the value of a degree from a given institution.

Not surprisingly, much attention has been paid to how to combat academic dishonesty. Literature on the subject, especially articles aimed at a general audience, tends to echo certain assumptions: that dishonest behavior is on the rise; that technologies such as the Internet and online learning have exacerbated the problem; and that technological tools for surveillance, such as online proctoring software or plagiarism checkers, are vital if the problem is to be curbed.

In this blog series, we will examine – and challenge – these assumptions. In the first installment, we will explore the scholarly literature to consider whether academic dishonesty is truly a growing problem and what its causes are. Subsequent installments will present strategies for promoting academic integrity in the classroom, with a focus on technology. We will consider what technology can do, and (just as importantly) what it cannot do, to prevent academic dishonesty.

Is the Problem Getting Worse?

Many media narratives take for granted that academic dishonesty – usually referred to by the popular term “cheating” – is worse today than it has ever been. Explanations for this include the easy availability of information on the Internet; the ubiquity of cell phones, which make sending and receiving messages easy; and, more broadly, a moral decline in society, with students taking an instrumentalist view of their education: grades are all that matter, and any method of securing a good grade is legitimate.

Going hand in hand with this narrative is a valorization of the notion of “control”. Bluntly put, if students are given the opportunity to cheat (so the thinking runs) they invariably will cheat. Thus, the key to academic integrity is hemming students in with controls that deprive them of any opportunity to behave dishonestly. Take away their laptops and cell phones; proctor them closely, whether in-person or online; check their work against databases of previous student work to find possible plagiarism; and so forth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has proven to be something of a laboratory for testing these claims. In the early days of the pandemic, when most colleges and universities made an emergency shift to remote instruction, there was an astronomical jump (nearly 200%) in questions submitted to the controversial “homework help” website Chegg (Redden 2021). Such data appeared to confirm widespread fears that students were taking advantage of the online environment to behave dishonestly. Deprived of the ability to proctor exams in-person, many institutions that had not previously used an online proctoring solution raced to adopt one (Flaherty 2020). Their decision found support in scholarly literature that argued proctoring is necessary, as students are more likely to consider cheating acceptable when an exam is unproctored (Dyer, Pettyjohn, and Saladin 2020). The University of Chicago itself set up an agreement with the online proctoring service Proctorio , although Academic Technology Solutions did not encourage its use.

This approach, however, has not been without pushback. Advocates of “compassionate pedagogy,” such as Jesse Stommel in his keynote at the 2021 Symposium for Teaching with Technology , have pointed out that claims of rampant cheating are often based on emotion rather than evidence. Furthermore, in the unprecedented and nightmarish circumstances of the pandemic, students reaching out for help wherever they can find it should not be taken as evidence of a moral collapse, but rather as an understandable coping strategy.

There is also empirical evidence that problematizes the narrative of skyrocketing academic dishonesty. Donald McCabe and Linda Trevino, in a longitudinal study, found that the percentage of students self-reporting dishonest behavior remained fairly constant between 1963 and 1993 (McCabe and Trevino 1996). Admittedly, this study predated the Internet and other technologies that may enable academic dishonesty, and it did find that certain types of cheating (notably unauthorized collaboration, which we will delve into in greater detail in future installments) were on the rise; nonetheless, it remains suggestive.

On a more fundamental level, though, it is worth considering why students may commit acts of academic dishonesty. If we look beyond a straightforward narrative of moral decline, we see that there are contextual factors that can make academic dishonesty more or less likely; most of these factors are not new, but they have long shaped the classroom environment. This discovery has important implications for our attitude toward technology. It can be argued (and, in subsequent installments, will be argued) that while technology does have a role to play in helping to promote academic integrity, no tool or piece of software is a panacea. Furthermore, we will show that many of the most important steps faculty and administrators can take to combat academic dishonesty have nothing to do with technology and everything to do with thoughtful, compassionate pedagogy.

Why Do Students Cheat?

There is, of course, no one answer to why students may choose to engage in academically dishonest behaviors. Empirical research, however, has identified certain factors that increase the likelihood of academic dishonesty. Some of these are personal; others are contextual. Our focus here will be on the latter, inasmuch as the individual faculty member or administrator has more control over them.

It has been shown repeatedly that peer attitudes and behavior are vital. If students perceive that their peers consider academic dishonesty acceptable, they are significantly more likely to behave dishonestly themselves (McCabe and Trevino 1997). Conversely, when a college or university has a strong culture of integrity – for example, an honor code that spells out student privileges and obligations – peer pressure can be a positive force, discouraging students from behaving dishonestly (McCabe, Trevino, and Butterfield 1999).

Problems of understanding what, in fact, academic dishonesty is can also lead to trouble. Many students come out of high school with a weak, if not nonexistent, understanding of such basic academic notions as how to cite sources properly. They may consider some academically dishonest behaviors as perfectly acceptable that faculty and administrators would condemn (Nelson, Nelson, and Tichenor 2013). Cultural differences can further cloud the picture. If a student is a non-native English speaker, for instance, he or she may struggle to understand the very concept of plagiarism – which, it must be borne in mind, is based upon a distinctly Western understanding of proper source usage (Click 2012).

Finally, the classroom environment itself is a powerful factor in shaping student attitudes. Student engagement is vital: if students feel that they are receiving personal attention and that the tasks their instructor assigns are meaningful, they are less likely to behave dishonestly. Conversely, if they feel a sense of alienation or “depersonalization,” or if they believe they are merely being given “busy work” with no pedagogical worth, the chances of their behaving dishonestly increase markedly (Pulvers and Diekhoff 1999). This danger is particularly acute in very large classes and in classes held online. The more a student feels that he or she is just a number (or a grade), the less restraint he or she is likely to feel about violating norms of conduct.

These conclusions will shape our analysis going forward. In Part 2, “Small Steps to Discourage Academic Dishonesty,” we will look at immediate, short-term steps that faculty and instructors can take to make academic dishonesty less likely. In Part 3, “Towards a Pedagogy of Academic Integrity,” we will step back and introduce broader pedagogical considerations, which require more time and effort to implement but which are also likely to have greater impact overall in reducing dishonest behavior.

Works Cited

Click, Amanda. “Issues of Plagiarism and Academic Integrity for Second-Language Students.” MELA Notes no. 85 (2012), pp. 44-53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23392491

Dyer, Jarrett A., Heidi C. Pettyjohn, and Steve Saladin. “Academic Dishonesty and Testing: How Student Beliefs and Test Settings Impact Decisions to Cheat”. Journal of the National College Testing Association vol. 4 issue 1 (2020), pp. 1-30. https://www.ncta-testing.org/assets/docs/JNCTA/2020%20-%20JNCTA%20-%20Academic%20Dishonesty%20and%20Testing.pdf

Flaherty, Colleen. Online proctoring is surging during COVID-19 ( Inside Higher Ed , May 11, 2020)

McCabe, Donald L., and Linda Klebe Trevino. “What We Know about Cheating in College: Longitudinal Trends and Recent Developments.” Change vol. 28 no. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1996), pp. 28-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40177789

McCabe, Donald L., and Linda Klebe Trevino. “Individual and Contextual Influences on Academic Dishonesty: A Multicampus Investigation.” Research in Higher Education vol. 38 no. 3 (Jun. 1997), pp. 379-396. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40196302

McCabe, Donald L., Linda Klebe Trevino, and Kenneth D. Butterfield. “Academic Integrity in Honor Code and Non-Honor Code Environments: A Qualitative Investigation.” Journal of Higher Education vol. 70 no. 2 (Mar.-Apr. 1999), pp. 211-234. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2649128

Nelson, Lynda P., Rodney K. Nelson, and Linda Tichenor. “Understanding Today’s Students: Entry-Level Science Student Involvement in Academic Dishonesty.” Journal of College Science Teaching vol. 42 no. 3 (Jan./Feb. 2013), pp. 52-57. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43631795

Pulvers, Kim, and George M. Diekhoff. “The Relationship between Academic Dishonesty and College Classroom Environment.” Research in Higher Education vol. 40 no. 4 (Aug. 1999), pp. 487-498. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40196358

Redden, Elizabeth. Study finds nearly 200 percent jump in questions submitted to Chegg after start of pandemic ( Inside Higher Ed , Feb. 5, 2021)

(Splash image by Okta_Aderama_Putra on Pixabay )

Search Blog

Subscribe by email.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Recent Posts

- New Features and Updates in Poll Everywhere

- Assess Programming Assignments with Gradescope

- Use Commonplacing to Help Students Better Understand Difficult Texts: Habits of Mind Series, Part One

- Text-to-Speech Is for Everyone

- What’s New in Canvas-Summer 2024

- A/V Equipment

- Accessibility

- Canvas Features/Functions

- Digital Accessibility

- Faculty Success Stories

- Instructional design

- Multimedia Development

- Poll Everywhere

- Surveys and Feedback

- Symposium for Teaching with Technology

- Uncategorized

- Universal Design for Learning

- Visualization

Plagiarism & Academic Integrity

- Academic Integrity

Types of Academic Dishonesty

- How to Avoid Plagiarism: Citing

- Citing Direct Quotes

- Paraphrasing

- Summarizing

- Try It! Identifying Plagiarism

- Understanding a Turnitin Report

There are many types of academic dishonesty - some are obvious, while some are less obvious.

- Misrepresentation ;

- Conspiracy ;

- Fabrication ;

- Collusion ;

- Duplicate Submission ;

- Academic Misconduct ;

- Improper Computer/Calculator Use ;

- Improper Online, TeleWeb, and Blended Course Use ;

- Disruptive Behavior ;

- and last, but certainly not least, PLAGIARISM .

We will discuss each of these types of academic dishonesty in more detail below. Plagiarism is the most common type of academic dishonesty, and also the easiest type to commit on accident! See the plagiarism page for more info about what plagiarism is and how to avoid it in your work.

Cheating is taking or giving any information or material which will be used to determine academic credit.

Examples of cheating include:

- Copying from another student's test or homework.

- Allowing another student to copy from your test or homework.

- Using materials such as textbooks, notes, or formula lists during a test without the professor's permission.

- Collaborating on an in-class or take-home test without the professor's permission.

- Having someone else write or plan a paper for you.

Bribery takes on two forms:

- Bribing someone for an academic advantage, or accepting such a bribe (i.e. a student offers a professor money, goods, or services in exchange for a passing grade, or a professor accepts this bribe).

- Using an academic advantage as a bribe (i.e. a professor offers a student a passing grade in exchange for money, goods, or services, or a student accepts this bribe).

Misrepresentation

Misrepresentation is any act or omission that is intented to deceive an instructor for academic advantage. Misrepresentation includes lying to an instructor in an attempt to increase your grade, or lying to an instructor when confronted with allegations of academic dishonesty.

Conspiracy means working together with one or more persons to commit or attempt to commit academic dishonesty.

Fabrication

Fabrication is the use of invented or misrepresentative information. Fabrication most often occurs in the sciences, when students create or alter experimental data. Listing a source in your works cited that you did not actually use in your research is also fabrication.

Collusion is the act of two or more students working together on an individual assignment.

Duplicate Submission

A duplicate submission means a student submits the same paper for two different classes. If a student submits the same paper for two different classes within the same semester, the student must have the permission of both instructors. If a student submits the same paper for two different classes in different semesters, the student must have the permission of their current instructor.

Academic Misconduct

Academic misconduct is the violation of college policies by tampering with grades or by obtaining and/or distributing any part of a test or assignment. For example:

- Obtaining a copy of a test before the test is admisistered.

- Distributing, either for money or for free, a test before it is administered.

- Encouraging others to obtain a copy of a test before the test is administered.

- Changing grades in a gradebook, on a computer, or on an assignment.

- Continuing to work on a test after time is called.

Improper Computer/Calculator Use

Improper computer/calculator use includes:

- Unauthorized use of computer or calculator programs.

- Selling or giving away information stored on a computer or calculator which will be submitted for a grade.

- Sharing test or assignment answers on a calculator or computer.

Improper Online, TeleWeb, and Blended Course Use

Improper online, teleweb, and blended course use includes:

- Accepting or providing outside help on online assignments or tests.

- Obtaining test materials or questions before the test is administered.

Disruptive Behavior

Disruptive behavior is any behavior that interfers with the teaching/learning process. Disruptive bahavior includes:

- Disrespecting a professor or another student, in class or online.

- Talking, texting, or viewing material unrelated to the course during a lecture.

- Failing to silence your cell phone during class.

- Posting inappropriate material or material unrealted to the course on discussion boards.

- << Previous: Academic Integrity

- Next: Plagiarism >>

- Last Updated: Jan 2, 2024 11:53 AM

- URL: https://spcollege.libguides.com/avoidplagiarism

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Promoting Academic Integrity

While it is each student’s responsibility to understand and abide by university standards towards individual work and academic integrity, instructors can help students understand their responsibilities through frank classroom conversations that go beyond policy language to shared values. By creating a learning environment that stimulates engagement and designing assessments that are authentic, instructors can minimize the incidence of academic dishonesty.

Academic dishonesty often takes place because students are overwhelmed with the assignments and they don’t have enough time to complete them. So, in addition to being clear about expectations and responsibilities related to academic integrity, instructors should also invite students to plan accordingly and communicate with them in the event of an emergency. Instructors can arrange extensions and offer solutions in case that students have an emergency. Communication between instructors and students is vital to avoid bad practices and contribute to hold on to the academic integrity values.

The guidance and strategies included in this resource are applicable to courses in any modality (in-person, online, and hybrid) and includes a discussion of addressing generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT with students.

On this page:

What is academic integrity, why does academic dishonesty occur, strategies for promoting academic integrity, academic integrity in the age of artificial intelligence, columbia university resources.

- References and Additional Resources

- Acknowledgment

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Promoting Academic Integrity. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/academic-integrity/

According to the International Center for Academic Integrity , academic integrity is “a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage.” We commit to these values to honor the intellectual efforts of the global academic community, of which Columbia University is an integral part.

Academic dishonesty in the classroom occurs when one or more values of academic integrity are violated. While some cases of academic dishonesty are committed intentionally, other cases may be a reflection of something deeper that a student is experiencing, such as language or cultural misunderstandings, insufficient or misguided preparation for exams or papers, a lack of confidence in their ability to learn the subject, or perception that course policies are unfair (Bernard and Keith-Spiegel, 2002).

Some other reasons why students may commit academic dishonesty include:

- Cultural or regional differences in what comprises academic dishonesty

- Lack or poor understanding on how to cite sources correctly

- Misunderstanding directions and/or expectations

- Poor time management, procrastination, or disorganization

- Feeling disconnected from the course, subject, instructor, or material

- Fear of failure or lack of confidence in one’s ability

- Anxiety, depression, other mental health problems

- Peer/family pressure to meet unrealistic expectations

Understanding some of these common reasons can help instructors intentionally design their courses and assessments to pre-empt, and hopefully avoid, instances of academic dishonesty. As Thomas Keith states in “Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem.” faculty and administrators should direct their steps towards a “thoughtful, compassionate pedagogy.”

The CTL is here to help!

The CTL can help you think through your course policies and ways to create community, design course assessments, and set up CourseWorks to promote academic integrity. Email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

In his research on cheating in the college classroom, James Lang argues that “the amount of cheating that takes place on our campuses may well depend on the structures of the learning environment” (Lang, 2013a; Lang, 2013b). Instructors have agency in shaping the classroom learning experience; thus, instances of academic dishonesty can be mitigated by efforts to design a supportive, learning-oriented environment (Bertam, 2017 and 2008).

Understanding Student’s Perceptions about Cheating

It is important to know how students understand critical concepts related to academic integrity such as: cheating, transparency, attribution, intellectual property, etc. As much as they know and understand these concepts, they will be able to show good academic integrity practices.

1. Acknowledge the importance of the research process, not only the outcome, during student learning.

Although the research process is slow and arduous, students should understand the value of the different processes involved during academic writing: investigation, reading, drafting, revising, editing and proof-reading. For Natalie Wexler, using generative Artificial Intelligence tools like ChatGPT as a substitute of writing itself is beyond cheating, an act of self cheating: “The process of writing itself can and should deepen that knowledge and possibly spark new insights” (“‘ Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete” ).

Ways to understand the value of writing their own work without external help, either from external sources, peers or AI, hinge on prioritizing the process over the product:

- Asking students to present drafts of their work and receive feedback can help students to gain confidence to continue researching and writing.

- Allowing students the freedom to choose or change their research topic can increase their investment in an assignment, which can motivate them to conduct their own writing and research rather than relying on AI tools.

2. Create a supportive learning environment

When students feel supported in a course and connected to instructors and/or TAs and their peers, they may be more comfortable asking for help when they don’t understand course material or if they have fallen behind with an assignment.

Ways to support student learning include:

- Convey confidence in your students’ ability to succeed in your course from day one of the course (this may ease student anxiety or imposter syndrome ) and through timely and regular feedback on what they are doing well and areas they can improve on.

- Explain the relevance of the course to students; tell them why it is important that they actually learn the material and develop the skills for themselves. Invite students to connect the course to their goals, studies, or intended career trajectories. Research shows that students’ motivation to learn can help deter instances of academic dishonesty (Lang, 2013a).

- Teach important skills such as taking notes, summarizing arguments, and citing sources. Students may not have developed these skills, or they may bring bad habits from previous learning experiences. Have students practice these skills through exercises (Gonzalez, 2017).

- Provide students multiple opportunities to practice challenging skills and receive immediate feedback in class (e.g., polls, writing activities, “boardwork”). These frequent low-stakes assessments across the semester can “[improve] students’ metacognitive awareness of their learning in the course” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 145).

- Help students manage their time on course tasks by scheduling regular check-ins to reduce students’ last minute efforts or frantic emails about assignment requirements. Establish weekly online office hours and/or be open to appointments outside of standard working hours. This is especially important if students are learning in different time zones. Normalize the use of campus resources and academic support resources that can help address issues or anxieties they may be facing. (See the Columbia University Resources section below for a list of support resources.)

- Provide lists of approved websites and resources that can be used for additional help or research. This is especially important if on-campus materials are not available to online learners. Articulate permitted online “study” resources to be used as learning tools (and not cheating aids – see McKenzie, 2018) and how to cite those in homework, writing assignments or problem sets.

- Encourage TAs (if applicable) to establish good relationships with students and to check-in with you about concerns they may have about students in the course. (Explore the Working with TAs Online resource to learn more about partnering with TAs.)

3. Clarify expectations and establish shared values

In addition to including Columbia’s academic integrity policy on syllabi, go a step further by creating space in the classroom to discuss your expectations regarding academic integrity and what that looks like in your course context. After all, “what reduces cheating on an honor code campus is not the code itself, but the dialogue about academic honesty that the code inspires. ” (Lang, 2013a, pp. 172)

Ways to cultivate a shared sense of responsibility for upholding academic integrity include:

- Ask students to identify goals and expectations around academic integrity in relation to course learning objectives.

- Communicate your expectations and explain your rationale for course policies on artificial intelligence tools, collaborative assignments, late work, proctored exams, missed tests, attendance, extra credit, the use of plagiarism detection software or proctoring software, etc. It will make a difference to take the time at the beginning of the course to explain differences between quoting, summarizing and paraphrasing. Providing examples of good and bad quotation/paraphrasing will help students to know what constitutes good academic writing.

- Define and provide examples for what constitutes plagiarism or other forms of academic dishonesty in your course.

- Invite students to generate ideas for responding to scenarios where they may be pressured to violate the values of academic integrity (e.g.: a friend asks to see their homework, or a friend suggests using chat apps during exams), so students are prepared to react with integrity when suddenly faced with these situations.

- State clearly when collaboration and group learning is permitted and when independent work is expected. Collaboration and group work provide great opportunities to build student-student rapport and classroom community, but at the same time, it can lead students to fall into academic misconduct due to unintended collaboration/failure to safeguard their work.

- Discuss the ethical, academic, and legal repercussions of posting class recordings, notes and/or class materials online (e.g., to sites such as Chegg, GitHub, CourseHero – see Lederman, 2020).

- Partner with TAs (if applicable) and clarify your expectations of them, how they can help promote shared values around academic integrity, and what they should do in cases of suspected cheating or classroom difficulties

4. Design assessments to maximize learning and minimize pressure

High stakes course assessments can be a source of student anxiety. Creating multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning, and spreading assessments throughout the semester can lessen student stress and keep the focus on student learning (see Darby, 2020 for strategies on assessing students online). As Lang explains, “The more assessments you provide, the less pressure you put on students to do well on any single assignment or exam. If you maintain a clear and consistent academic integrity policy, and ensure that all students caught cheating receive an immediate and substantive penalty, the benefit of cheating on any one assessment will be small, while the potential consequences will be high” (Lang, 2013a and Lang, 2013c). For support with creating online exams, please please refer to our Creating Online Exams resource .

Ways to enhance one’s assessment approach:

- Design assignments based on authentic problems in your discipline. Ask students to apply course concepts and materials to a problem or concept.

- Structure assignments into smaller parts (“scaffolding”) that will be submitted and checked throughout the semester. This scaffolding can also help students learn how to tackle large projects by breaking down the tasks.

- Break up a single high-stakes exam into smaller, weekly tests. This can help distribute the weight of grades, and will lessen the pressure students feel when an exam accounts for a large portion of their grade.

- Give students options in how their learning is assessed and/or invite students to present their learning in creative ways (e.g., as a poster, video, story, art project, presentation, or oral exam).

- Provide feedback prior to grading student work. Give students the opportunity to implement the feedback. The revision process encourages student learning, while also lowering the anxiety around any one assignment.

- Utilize multiple low-stakes assignments that prepare students for high-stakes assignments or exams to reduce anxiety (e.g., in-class activities, in-class or online discussions)

- Create grading rubrics and share them with your students and TAs (if applicable) so that expectations are clear, to guide student work, and aid with the feedback process.

- Use individual student portfolio folders and provide tailored feedback to students throughout the semester. This can help foster positive relationships, as well as allow you to watch students’ progress on drafts and outlines. You can also ask students to describe how their drafts have changed and offer rationales for those decisions.

- For exams , consider refreshing tests every term, both in terms of organization and content. Additionally, ground your assignments by having students draw connections between course content and the unique experience of your course in terms of time (unique to the semester), place (unique to campus, local community, etc. ), personal (specific student experiences), and interdisciplinary opportunities (other courses students have taken, co-curricular activities, campus events, etc.). (Lang, 2013a, pp. 77).

Since its release, ChatGPT has raised concern in universities across the country about the opportunity it presents for students to cheat and appropriate AI ideas, texts, and even code as their own work. However, there are also potential positive uses of this tool in the learning process–including as a tool for teachers to rely on when creating assessments or working with repetitive and time-consuming tasks.

Possible Advantages of ChatGPT

Due to the novelty of this tool, the possible advantages that might present in the teaching-learning process should be under the control of each instructor since they know exactly what they expect from students’ work.

Prof. Ethan Mollick teaches innovation and entrepreneurship at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and has been openly sharing on his Twitter account his journey incorporating ChatGPT into his classes. Prof. Mollick advises his students to experiment with this tool, trying and retrying prompts. He recognizes the importance of acknowledging its limits and the risks of violating academic honesty guidelines if the use of this tool is not stated at the end of the assignment.

Prof. Mollick uncovers four possible uses of this AI tool, ranging from using ChatGPT as an all-knowing intern, as a game designer, as an assistant to launch a business, or even to “hallucinate” together ( “Four Paths to the Revelation” ). For Prof. Mollick, ChatGPT is a useful technology to craft initial ideas, as long as the prompts are given within a specific field, include proper context, step-by-step directions and have the proper changes and edits.

Resources for faculty:

- Academic Integrity Best Practices for Faculty (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

- Faculty Statement on Academic Integrity (Columbia College)

- FAQs: Academic Integrity from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Ombuds Office for assistance with academic dishonesty issues.

- Columbia Center of Artificial Intelligence Technology

Resources for students:

- Policies from Columbia Student Conduct and Community Standards

- Understanding the Academic Integrity Policy (Columbia College & School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

Student support resources:

- Maximizing Student Learning Online (Columbia Online)

- Center for Student Advising Tutoring Service (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Help Rooms and Private Tutors by Department (Berick Center for Student Advising

- Peer Academic Skills Consultants (Berick Center for Student Advising)

- Academic Resource Center (ARC) for School of General Studies

- Center for Engaged Pedagogy (Barnard College)

- Writing Center (for Columbia undergraduate and graduate students)

- Counseling and Psychological Services

- Disability Services

For graduate students:

- Writing Studio (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Student Center (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

- Teachers College

Columbia University Information Technology (CUIT) CUIT’s Academic Services provides services that can be used by instructors in their courses such as Turnitin , a plagiarism detection service and online proctoring services such as Proctorio , a remote proctoring service that monitors students taking virtual exams through CourseWorks.

Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) The CTL can help you think through your course policies, ways to create community, design course assessments, and setting up CourseWorks to promote integrity, among other teaching and learning facets. To schedule a one-on-one consultation, please contact the CTL at [email protected] .

References

Bernard, W. Jr. and Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic Dishonesty: An Educator’s Guide . Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press.

Bertram Gallant, T. (2017). Academic Integrity as a Teaching and Learning Issue: From Theory to Practice . Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 88-94.

Bertram Gallant, T. (Ed.). (2008). Academic Integrity in the Twenty-First Century: A Teaching and Learning Imperative . ASHE Higher Education Report . 33(5), 1-143.

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Creating Online Exams .

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2020). Working with TAs online .

Darby, F. (2020). 7 Ways to Assess Students Online and Minimize Cheating . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Gonzalez, J. (2017, February). Teaching Students to Avoid Plagiarism . Cult of Pedagogy, 26.

International Center for Academic Integrity (2023). Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity .

International Center on Academic Integrity (2023). https://academicintegrity.org/

Keith, T. Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. (2022, Feb 16).

Lang, J.M. (2013a). Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty . Harvard University Press.

Lang, J. M. (2013b). Cheating Lessons, Part 1 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lang, J. M. (2013c). Cheating Lessons, Part 2 . The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Lederman, D. (2020, February 19). Course Hero Woos Professors . Inside Higher Ed.

McKenzie, L. (2018, May 8). Learning Tool or Cheating Aid? Inside Higher Ed.

Marche, S. (2022, Dec 6). The College Essay is Dead. The Atlantic.

Mollick, E. (2023, Jan 17). All my Classes Suddenly Became AI Classes. One Useful Thing.

Mollick, Ethan. (2022, Dic 8). Four Paths to the Revelation. One Useful Thing.

Wexler, N. Bots’ Can Write Good Essays, But That Doesn’t Make Writing Obsolete. Minding the Gap.

Additional Resources

Bretag, T. (Ed.). (2016). Handbook of Academic Integrity. Singapore: Springer Publishing.

Ormand, C. (2017 March 6). SAGE Musings: Minimizing and Dealing with Academic Dishonesty . SAGE 2YC: 2YC Faculty as Agents of Change.

WCET (2009). Best Practice Strategies to Promote Academic Integrity in Online Education .

Thomas, K. (2022 February 16). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 1 – Understanding the Problem. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 February 25). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 2: Small Steps to Discourage Academic Dishonesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 April 28). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 3: Towards a Pedagogy of Academic Integrity. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

______. (2022 June 7). Combating Academic Dishonesty, Part 4: Library Services to Support Academic Honesty. The University of Chicago. Academic Technology Solutions.

Acknowledgement

This resource was adapted from the faculty booklet Promoting Academic Integrity & Preventing Academic Dishonesty: Best Practices at Columbia University developed by Victoria Malaney Brown, Director of Academic Integrity at Columbia College and Columbia Engineering, Abigail MacBain and Ramón Flores Pinedo, PhD students in GSAS. We would like to thank them for their extensive support in creating this academic integrity resource.

Want to communicate your expectations around AI tools?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Academic Integrity at MIT

A handbook for students, search form, what are the consequences.

The consequences for cheating, plagiarism, unauthorized collaboration, and other forms of academic dishonesty can be very serious, possibly including suspension or expulsion from the Institute. Any violation of the rules outlined in this handbook, established by the instructor of the class, or deviating from responsible conduct of research, may be considered violations of academic integrity. The MIT Policy on Student Academic Dishonesty is outlined in MIT’s Policies and Procedures 10.2 .

Instructors, research or thesis supervisors decide how to handle violations of academic integrity on a case-by-case basis, and three options exist. Questions about these options should be directed to the Office of Student conduct ( [email protected] ).

Academic consequences within a class or research project

Within a class, the instructor determines what action is appropriate to take. Such action may include:

requiring the student to redo the assignment for a reduced grade.

assigning the student a failing grade for the assignment.

assigning the student a failing grade for the class.

For a research project, the supervisor determines what action is appropriate to take. Such action may include:

- terminating the student's participation in the research project.

The instructor or supervisor may also submit documentation to the Office of Student Citizenship in the form of a letter to file or a formal complaint. These options are outlined below.

Letter to file

The instructor or supervisor writes a letter describing the nature of the academic integrity violation, which is placed in the student’s discipline file. The student’s discipline file is maintained by the Office of Student Citizenship (OSC) and is not associated with the student’s academic record .

A letter may be filed with the OSC in addition to the action already taken in the class or research project.

If a student receives a letter to file, s/he has the right to:

submit a reply, that is added to the student’s file.

appeal the letter to the Committee on Discipline (COD) for a full hearing.

In resolving the violation described in the letter, the OSC reviews any previous violations which are documented in the student’s discipline file.

Committee on Discipline (COD) complaint

The instructor or supervisor submits a formal complaint to the COD, which resolves cases of alleged student misconduct.

This complaint may be filed with the OSC in addition to the action already taken in the class or research project.

A COD complaint is reviewed by the COD Chair and considered for a hearing. Any previous violations documented in the student’s discipline file are reviewed as part of this process.

Cases resulting in a hearing are subject to a full range of sanctions, including probation, suspension, dismissal, or other educational sanctions.

Policies, Procedures, and Contacts

- MIT Policy on Student Academic Dishonesty

- Typical MIT Student Discipline Process Outline

- Committee on Discipline Rules and Regulations

- Office of Student Conduct and Community Standards

- For Faculty and Staff: What You Should Know about Academic Integrity

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

Academic integrity vs. academic dishonesty: understanding the key differences.

- How to Use AI to Enhance Your Thesis

- Guide to Structuring Your Narrative Essay for Success

- How to Hook Your Readers with a Compelling Topic Sentence

- Is a Thesis Writing Format Easy? A Comprehensive Guide to Thesis Writing

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

- How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

Academic integrity and academic dishonesty are terms that are frequently mentioned in educational settings, but understanding their full implications is essential for students, educators, and institutions alike. This article explores what academic integrity is, the principles of academic honesty and what academic dishonesty entails, and provides examples of both to clarify the key differences.

What is Academic Integrity?

Academic integrity refers to the ethical standards and moral code followed in the academic world. It encompasses values such as honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility. Upholding academic integrity means that students and scholars commit to producing work that is genuine, original, and reflective of their own understanding and effort.

Core Principles of Academic Integrity

- Honesty : Being truthful in all academic endeavours.

- Trust : Establishing mutual respect and confidence between educators and students.

- Fairness : Ensuring equal opportunities and treatment for all students.

- Responsibility : Taking accountability for one’s actions and learning process.

Academic Integrity Examples

- Proper Citation : Correctly citing all sources of information and ideas that are not your own.

- Original Work : Submitting assignments and research that are entirely your own creation.

- Honest Collaboration : Working with peers only when it is allowed and making sure to acknowledge their contributions.

- Reporting Misconduct : Informing authorities about any instances of academic dishonesty you encounter.

- Preparation and Effort : Completing all assignments to the best of your ability without resorting to shortcuts or unethical practices.

What is Academic Dishonesty?

Academic dishonesty, on the other hand, involves actions that violate these ethical standards and principles. It includes any form of cheating, plagiarism, fabrication, and other deceitful practices that compromise the integrity of the educational process.

Academic Dishonesty Examples

- Plagiarism : Using someone else's work, ideas, or expressions without proper acknowledgement. This can include copying text from a book, website, or another student's paper.

- Cheating : Using unauthorised materials or receiving assistance during an examination. This can involve anything from bringing notes into an exam to obtaining answers from another student.

- Fabrication : Falsifying or inventing information, data, or citations in academic assignments.

- Collusion : Collaborating with others on assignments that are meant to be completed individually.

- Impersonation : Pretending to be another student or having someone else pretend to be you in an examination or other academic activity.

Consequences of Academic Dishonesty

Engaging in academic dishonesty can have severe consequences, impacting a student's academic and professional future. These repercussions can include:

Academic Penalties : Institutions often impose strict penalties on those found guilty of academic dishonesty. These can range from failing the assignment or course to suspension or even expulsion from the institution.

Loss of Reputation : A record of academic dishonesty can tarnish a student’s reputation, affecting relationships with peers, professors, and future employers. It can also result in loss of scholarships or other academic honours.

Legal Ramifications : In some cases, particularly those involving significant fraud or impersonation, legal action may be taken against the offending student.

Personal Consequences : Beyond institutional and legal penalties, students may suffer from personal guilt, loss of self-respect, and damaged relationships due to their dishonest actions.

The Importance of Academic Integrity

When students commit to academic honesty, they develop critical thinking skills by engaging deeply with the material, which enhances understanding and fosters critical analysis. Additionally, maintaining integrity in academic work helps build a strong reputation, benefiting future educational and career opportunities. Furthermore, honest efforts lead to genuine learning and self-improvement, fostering personal growth.

Maintaining high standards of academic integrity ensures that institutions preserve academic standards by protecting the value and credibility of their qualifications. It also promotes a culture of trust, encouraging honesty and responsibility to foster a positive learning environment. Additionally, adhering to ethical standards helps prevent legal disputes and maintains the institution's reputation.

How to Uphold Academic Integrity

To maintain academic integrity, it is essential to understand your institution's policies and ensure you are clear about what is expected of you. Developing good study habits is equally important; allocate sufficient time for studying and completing assignments to avoid the temptation of taking shortcuts. Additionally, learning how to cite sources correctly is crucial for avoiding plagiarism . If you find yourself struggling with your coursework, seek help from tutors, professors, or academic support services instead of resorting to dishonest practices. Reflect on the importance of integrity in both your personal and professional life, and let these values guide your academic endeavours.

Understanding the key differences between academic integrity and academic dishonesty is fundamental for anyone involved in education. Academic integrity is about committing to honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility, while academic dishonesty undermines these values and compromises the educational process.

A freshers’ guide to money and work

A freshers’ guide to university and mental health

How to Make the Most of Your Easter Break

Writing services.

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

Academic Honesty Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Academic honesty, dishonest conduct, preventing academic dishonesty.

Lately, academic honesty has become a major issue among the elite in the academic environments. It can no longer be simply defined as the carrying of illegal materials into the exam rooms or copying someone else’s work. Indeed, with growth in technology like smart phones and emergence of the use of internet in research work has caused administrators in universities and colleges to extend the definition of academic honesty or dishonesty.

Academic honesty involves the students submitting work that is originally theirs and inclusion of the cited sources in their work. The academic community is generally aware that it is not possible for students to come up with their own original work and therefore, allow inclusion of other people’s work in form of direct quotes of paraphrases only if the original author is appropriately acknowledged. Academic honesty takes different forms and addresses in various aspects in schools and colleges.

Academic honesty is considered important because the results obtained from schools or colleges are referred to in future. Future employers refer to these documents when assessing the abilities and gifts of the students before actual employment.

Therefore, high levels of integrity should be adhered to in order to ensure quality reports and accurate assessment of the student’s abilities and potential (Vegh, 2009). Students commit academic dishonesty when they engage in activities that are classified in four general types; namely, cheating, dishonest conduct, plagiarism and collusion.

Cheating is the most ancient form of academic dishonesty known in history. It takes different forms whereby the rules and regulations governing formal or informal examinations are violated. For instance, copying other people’s work during examination, sharing one’s answers with another during examinations, or submission of other people’s work, as one’s own original work.

During examinations, invigilators are placed strategically in the exam room to monitor the behavior of students but some students attempt to share answers (Vegh, 2009). A student is not allowed to communicate to their fellow students in an exam room without the express permission of the invigilator and a violation of these rule amounts to cheating. Taking an examination on behalf of another student also amounts to cheating. Generally, cheating offers unfair advantage to the students involved over the rest.

Unfair advantage could also be meted on students when they commit dishonest conducts like stealing examination or answer keys from the instructor. Desperate times call for desperate measures and students are capable of doing anything to rescue their dreams of scooping first class honors.

Such cases have been reported severally and they can be classified as dishonest conduct (“What is Academic Dishonesty”, 1996, p.77). Further, students who try to change official academic results without following the procedures laid by the respective academic institutions commit dishonest conducts. Obtaining answers before the actual exam or altering records after certification leads to low academic standards.

Plagiarism is the recent form of violating academic honesty and defined as intellectual theft. The crime comes in when one makes use of another person’s findings, as if his/hers, without giving the due credit to the source. Plagiarism takes the form of stealing other people’s ideas or words and the form of use of other people’s work without crediting the source properly.

The sources mentioned here include articles from electronic journals, newspaper articles, published books, and even websites (Bouchard, 2010). The internet has become a source of information for research and the easy accessibility and convenience of the same provides a temptation to the students to copy and paste other people’s work.

However, it amounts to plagiarism and is classified as a violation of academic honesty. Though plagiarism can be either intentional or unintentional on the part of the student, it still amounts to academic dishonesty either way. Students should therefore be careful to ensure that their work is free of any form of plagiarism.

Academic institutions have come up with measures to curb the spread of academic dishonesty to maintain the credibility of their programs. Academic dishonesty leads to production of half-baked graduates who lower the standards of education hence that of the university (Staats, Hupp, & Hagley, 2008, p.360).