How to Write the Perfect Body Paragraph

A body paragraph is any paragraph in the middle of an essay , paper, or article that comes after the introduction but before the conclusion. Generally, body paragraphs support the work’s thesis and shed new light on the main topic, whether through empirical data, logical deduction, deliberate persuasion, or anecdotal evidence.

Some English teachers will tell you good writing has a beginning, middle, and end, but then leave it at that. And that’s true—almost all good writing follows an introduction-body-conclusion format. But what no one seems to talk about is that the vast majority of your writing will be middle . That puts a lot of significance on knowing how to write a body paragraph.

Give paragraphs extra polish Grammarly helps you write your best Write with Grammarly

Don’t get us wrong—introductions and conclusions are crucial. They fulfill additional responsibilities of preparing the reader and sending them off with a lasting impression, which is why every good writer knows how to write an introduction and how to write a conclusion . But in terms of volume , body paragraphs comprise almost all of your work.

We explain precisely how to write a body paragraph so your writing has substance through and through. After all, it’s what’s on the inside that counts!

Structure of a body paragraph

Think of individual paragraphs as microcosms of the greater work; each paragraph has its own miniature introduction, body, and conclusion in the form of sentences.

Let’s break it down. A good body paragraph contains the following four elements, some of which you may recognize from our ultimate guide to paragraphs :

- Transitions: These are a few words at the beginning or end of a paragraph that connect the body paragraph to the others, creating a coherent flow throughout the entire piece.

- Topic sentence: A sentence—almost always the first sentence—introduces what the entire paragraph is about.

- Supporting sentences: These make up the “body” of your body paragraph, with usually one to three sentences that develop and support the topic sentence’s assertion with evidence, logic, persuasive opinion, or expert testimonial.

- Conclusion (Summary): This is your paragraph’s concluding sentence, summing up or reasserting your original point in light of the supporting evidence.

To understand how these components make up a body paragraph, let’s look at a sample from literary icon Kurt Vonnegut Jr. In it, he himself looks to other literary phenoms William Shakespeare and James Joyce. The following sample comes from Vonnegut’s essay “ How to write with style .” It’s a great example of how a body paragraph supports the thesis, which in this case is: To write well, “keep it simple.”

As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. “To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.” At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

In this sample, Vonnegut demonstrates the four main elements of body paragraphs in a way that makes it easy to identify them. Let’s take a closer look at each.

As for your use of language:

Rather than opening the paragraph with an abrupt change of topic, Vonnegut uses a simple, even generic, transition that softy guides the reader into a new conversation. The point of transitions is to remove any jarring distractions when moving from one paragraph to the next. They don’t need to be complicated; sometimes a quick phrase like “on the other hand” or even a single word like “however” will suffice.

Topic sentence

Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound.

Here, Vonnegut puts forth his main point, that even the greatest writers sometimes use simple language to convey complex ideas—the thesis of this particular body paragraph.

Supporting sentences

“To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.”

To support his thesis, Vonnegut pulls two direct quotes from respected writers and then dissects the wording to support his initial claim. Notice how there are a few different sentences with each exploring their own points, but they all relate to and support the paragraph’s main thesis.

At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Vonnegut ends the paragraph with a pithy statement claiming that complex language would have been less effective, reaffirming his central claim that great writers know simple language works best.

How to start a body paragraph

Often the hardest sentence to write, the first sentence of your body paragraph should act as the topic sentence, introducing the main point of the entire paragraph. Also known as the “paragraph leader,” the topic sentence opens the discussion with an underlying claim (or sometimes a question).

After reading the opening sentence, the reader should know, in no uncertain terms, what the rest of the paragraph is about. That’s why topic sentences should always be clear, concise, and to the point. Avoid distractions or tangents—there will be time for elaboration in the supporting sentences. At times you can be coy and mysterious to build suspense, opening with a question that ultimately gets answered later in the paragraph. Nonetheless, you should still reveal enough information to set the stage for the rest of the sentences.

More often than not, your first sentence should also contain a transition to bridge the gap from the preceding paragraph. Under special circumstances, you may also put a transition at the end of the sentence, but in general, putting it at the beginning is better for readability.

Don’t let transitions intimidate you; they can be quite simple and even easy to apply. Usually, a single word or short phrase will do the job. Just be careful not to overuse the same transitions one after another. To help expand your transitional vocabulary, our guide to connecting sentences collects some of the most common transition words and phrases for inspiration.

How to end a body paragraph

Likewise, the concluding sentence to your body paragraph holds extra weight. Because the reader takes a momentary pause at the end of each paragraph, that last sentence will “echo” just a bit longer in their minds while their eyes find the beginning of the next paragraph. You can take advantage of those extra milliseconds to leave a lasting impression on your reader.

In form, your concluding sentence should summarize the thesis of your topic sentence while incorporating the supporting evidence—in other words, it should wrap things up.

It’s useful to end on a meaningful or even emotional point to encourage the reader to reflect on what was discussed. Vonnegut’s conclusion from our sample makes a strong and forceful statement, invoking heartbreak (“break the heart”) and using absolute language (“no other words”). Powerful language like this might be too climactic for the supporting sentences, but in a conclusion, it fits perfectly.

How to write a body paragraph

First and foremost, double-check that your body paragraph supports the main thesis of the entire piece, much like the paragraph’s supporting sentences support the topic sentence. Don’t forget your body paragraph’s place in the greater work.

When it comes to actually writing a body paragraph, as always we recommend planning out what you want to say beforehand, which is a good reason to learn how to write an outline . Crafting a good body paragraph involves organizing your supporting sentences in the optimal order—but you can’t do that if you don’t know what those sentences will be!

A lot of times, your supporting sentences will dictate their own logical progression, with one naturally leading into the next, as is often the case when building an argument. Other times, you’ll have to make a choice about which evidence to present first and last, as Vonnegut did when choosing between his Shakespeare and Joyce examples. Also as with Vonnegut’s example, your choice of conclusion may help determine the best order.

This can be a lot of take in, especially if you’re still learning the fundamentals of writing. Luckily, you don’t have to do it alone! Grammarly offers suggestions beyond spelling and grammar, helping you hone clarity, tone, and conciseness in your writing. With Grammarly, ensure your writing is clear, engaging, and polished, wherever you type.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Body Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap-up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: T ransition, T opic sentence, specific E vidence and analysis, and a B rief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant ) –TTEB!

- A T ransition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

- A T opic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific E vidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A B rief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument :

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage , clear purpose , and great ), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E. Lee.

The following is a clear example of deduction gone awry:

- Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

- Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

- Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will make a good pet is invalid.

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme. Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. Therefore, the unstated premise is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic structure:

- Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

- Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

- Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid argument, you may want to look at the United States Declaration of Independence. The first section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together in a compelling conclusion.

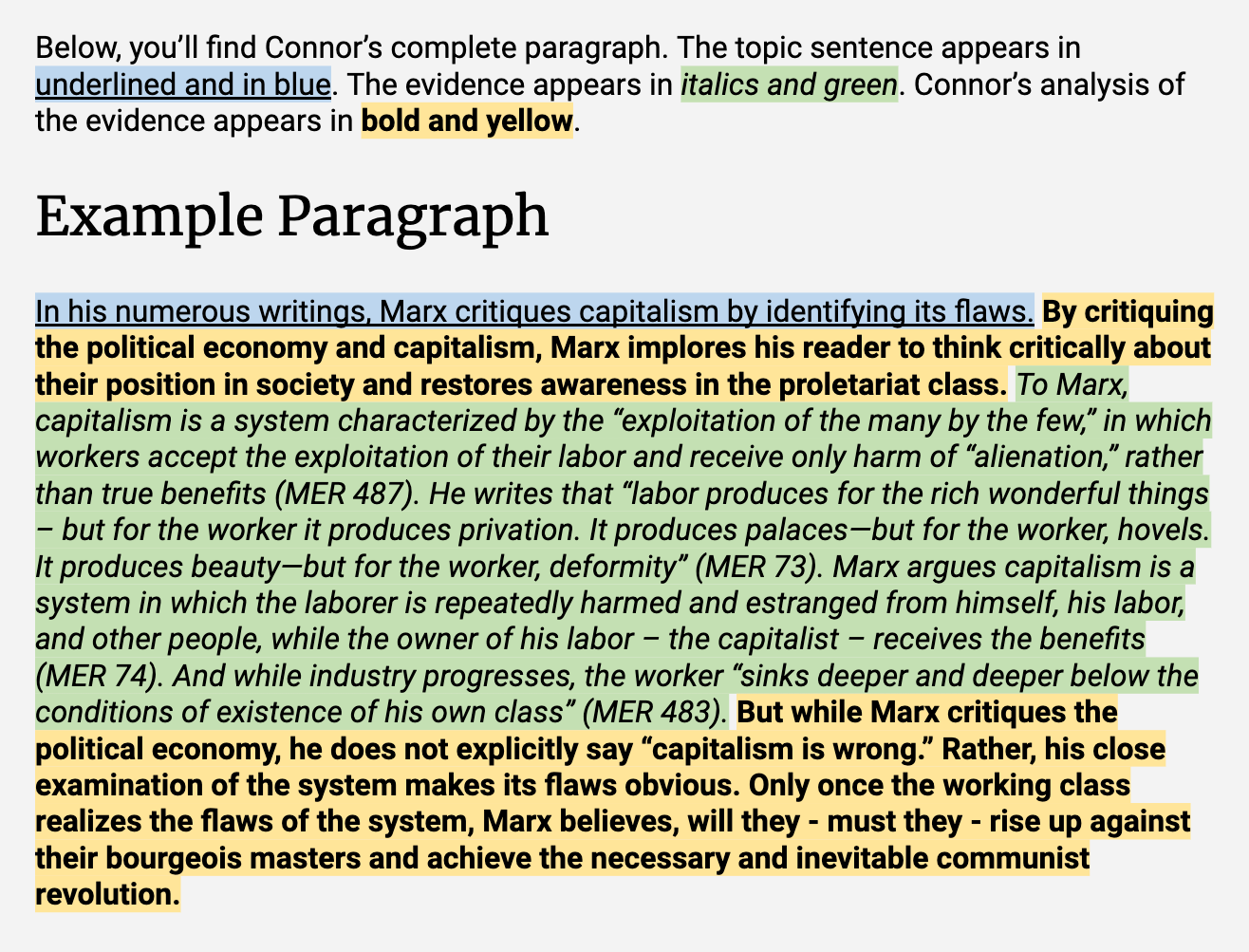

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

- Body paragraphs play an essential role in crafting a successful college essay.

- The basic body paragraph structure has six parts, including a topic sentence and evidence.

- Key paragraphing tips include moving transitions and avoiding repetition in your essay.

Paragraphing is an essential key to successful academic writing. A writer’s organizing decisions control the reader’s (i.e., your professor’s) attention by raising or decreasing engagement with the subject. Writing an effective paragraph includes determining what goes into each paragraph and how your paragraphs and ideas relate to one another.

The first paragraph in any academic essay is the introduction , and the last is the conclusion, both of which are critical to crafting a compelling essay. But what is a body paragraph? The body paragraphs — all the paragraphs that come between the intro and conclusion — comprise the bulk of the essay and together form the student’s primary argument.

In this article, we look at the function of a body paragraph and provide guidance on how to write a good body paragraph for any college essay.

What Is the Purpose of a Body Paragraph?

Body paragraphs play an indispensable role in proving the essay’s thesis , which is presented in the introduction. As a sequence, body paragraphs provide a path from the introduction — which forecasts the structure of the essay’s content — to the conclusion, which summarizes the arguments and looks at how final insights may apply in different contexts. Each body paragraph must therefore relate logically to the one immediately before and after it.

If you can eliminate a paragraph without losing crucial information that supports your thesis claim, then that paragraph is a divergence from this path and should be edited so that it fits with the rest of your essay and contains necessary evidence, context, and/or details.

Each body paragraph must relate logically to the one immediately before and after it, and must also focus on a single topic or idea.

Each paragraph must also focus on a single topic or idea. If the topic is complex or has multiple parts, consider whether each would benefit from its own paragraph.

People tend to absorb information in short increments, and readers usually time mental breaks at paragraph ends. This stop is also where they pause to consider content or write notes. As such, you should avoid lengthy paragraphs.

Finally, most academic style conventions frown upon one-sentence paragraphs. Similar to how body paragraphs can be too long and messy, one-sentence paragraphs can feel far too short and underdeveloped. Following the six steps below will allow you to avoid this style trap.

Popular Online Programs

Learn about start dates, transferring credits, availability of financial aid, and more by contacting the universities below.

6 Steps for Writing an Effective Body Paragraph

There are six main steps to crafting a compelling body paragraph. Some steps are essential in every paragraph and must appear in a fixed location, e.g., as the first sentence. Writers have more flexibility with other steps, which can be delayed or reordered (more on this later).

Step 1: Write a Topic Sentence

Consider the first sentence in a body paragraph a mini-thesis statement for that paragraph. The topic sentence should establish the main point of the paragraph and bear some relationship to the essay’s overarching thesis statement.

In theory, by reading only the topic sentence of every paragraph, a reader should be able to understand a summary outline of the ideas that prove your paper’s thesis. If the topic sentence is too complex, it’ll confuse the reader and set you up to write paragraphs that are too long-winded.

Step 2: Unpack the Topic Sentence

Now, it’s time to develop the claims in your paragraph’s topic sentence by explaining or expanding all the individual parts. In other words, you’ll parse out the discussion points your paragraph will address to support its topic sentence.

You may use as many sentences as necessary to achieve this step, but if there are too many components, consider writing a paragraph for each of them, or for a few that fit particularly well together. In this case, you’ll likely need to revise your topic sentence. The key here is only one major idea per paragraph.

Step 3: Give Evidence

The next step is to prove your topic sentence’s claim by supplying arguments, facts, data, and quotations from reputable sources . The goal is to offer original ideas while referencing primary sources and research, such as books, journal articles, studies, and personal experiences.

Step 4: Analyze the Evidence

Never leave your body paragraph’s evidence hanging. As the writer, it’s your job to do the linking work, that is, to connect your evidence to the main ideas the paragraph seeks to prove. You can do this by explaining, expanding, interpreting, or commentating on your evidence. You can even debunk the evidence you’ve presented if you want to give a counterargument.

Step 5: Prove Your Objective

This next step consists of two parts. First, tie up your body paragraph by restating the topic sentence. Be sure to use different language so that your writing is not repetitive. Whereas the first step states what your paragraph will prove, this step states what your paragraph has proven .

Second, every three or four paragraphs, or where it seems most fitting, tie your proven claim back to the paper’s thesis statement on page 1. Doing so makes a concrete link between your discussion and the essay’s main claim.

Step 6: Provide a Transition

A transition is like a bridge with two ramps: The first ramp takes the reader out of a topic or paragraph, whereas the second deposits them into a new, albeit related, topic. The transition must be smooth, and the connection between the two ideas should be strong and clear.

Purdue University lists some of the most commonly used transition words for body paragraphs.

Body Paragraph Example

Here is an example of a well-structured body paragraph, and the beginning of another body paragraph, from an essay on William Shakespeare’s play “Twelfth Night.” See whether you can identify the topic sentence and its development, the evidence, the writer’s analysis and proof of the objective, and the transition to the next paragraph.

As well as harmony between parent and child, music represents the lasting bond between romantic couples. Shakespeare illustrates this tunefulness in the relationship between Viola and Orsino. Viola’s name evokes a musical instrument that fits between violin and cello when it comes to the depth of tone. Orsino always wants to hear sad songs until he meets Viola, whose wit forces him to be less gloomy. The viola’s supporting role in an orchestra, and Orsino’s need for Viola to break out of his depression, foreshadow the benefits of the forthcoming marriage between the two. The viola is necessary in both lamenting and celebratory music. Shakespeare uses the language of orchestral string music to illustrate how the bonds of good marriages often depend on mediating between things.

The play also references cacophonous music. The unharmonious songs that Sir Toby and Andrew sing illustrate how indulging bad habits is bad for society as a whole. These characters are always drunk, do no work, play mean tricks, and are either broke or squander their money. …

Strategies for Crafting a Compelling Body Paragraph

Break down complex topic sentences.

A topic sentence with too many parts will force you to write a lot of support. But as you already know, readers typically find long paragraphs more difficult to absorb. The solution is to break down complicated topic sentences into two or more smaller ideas, and then devote a separate paragraph for each.

Move the Transition to the Following Paragraph

Though a body paragraph should always begin with a topic sentence and end with proof of your objective — sometimes with a direct connection to the essay’s thesis — you don’t need to include the transition in that paragraph; instead, you may insert it right before the topic sentence of the next paragraph.

For example, if a body paragraph is already incredibly long, you might want to avoid adding a transition at the end.

Your body paragraphs should be no longer than half to three-quarters of a double-spaced page with 1-inch margins in Times New Roman 12-point font. A little longer is sometimes acceptable, but you should generally avoid writing paragraphs that fill or exceed one page.

Shift Around Some of the Paragraph Steps Above

The steps above are a general guide, but you may change the order of them (to an extent). For instance, if your topic sentence is fairly complicated, you might need to unpack it into several parts, with each needing its own evidence and analysis.

You could also swap steps 3 and 4 by starting with your analysis and then providing evidence. Even better, consider alternating between giving evidence and providing analysis.

The idea here is that using more than one design for your paragraphs usually makes the essay more engaging. Remember that monotony can make a reader quickly lose interest, so feel free to change it up.

Don’t Repeat the Same Information Between Paragraphs

If similar evidence or analysis works well for other paragraphs too, you need to help the reader make these connections. You can do this by incorporating signal phrases like “As the following paragraph also indicates” and “As already stated.”

Explore More College Resources

How to Choose Your College Class Schedule

Learn how to create the best class schedule each semester by considering important academic and nonacademic factors.

by Steve Bailey

Updated March 22, 2023

Full-Time vs. Part-Time Student: What’s the Difference?

Discover the challenges and opportunities full-time vs. part-time students face and get tips on which college experience is right for you.

by Marisa Upson

Updated October 12, 2023

Summer Semester: When Does It Start? And Should You Enroll?

School’s out — or, rather, in — for summer. Discover the pros and cons of enrolling in an optional summer semester in college.

by Anne Dennon

Updated March 20, 2023

- Generating Ideas

- Practical Strategies for Composing and Editing Papers

- Practical Tips for Composing and Editing Papers

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWS Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement (Writing in the Majors)

- Course Application for Instructors

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- What Students Learn in UWS

- Teaching Resources

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Constructing effective body paragraphs.

A paragraph is a collection of related sentences dealing with a single topic. This handout breaks the paragraph down into its conceptual and structural components.

Conceptual Components

The entire paragraph should push toward proving a single idea. In other words, its analysis should move in one direction toward proving the claim laid out in the topic sentence. If it begins with one focus or major point for discussion, it should not end with another or wander within different ideas.

It is useful to envision body paragraphs as links in the chain of reasoning that forms the overall argument of your essay. In order to get to the next link, each paragraph must establish a claim that moves your overall argument one step closer to its ultimate goal (i.e., proving its thesis). Though the topic sentence will announce your paragraph’s direction, the movement of your analysis within the paragraph will consist of pushing this claim from being unproven at the outset of the paragraph to logically compelling at the end.

Bridges establish the coherence that makes the movement between your ideas easily understandable to the reader. Logical bridges ensure that the same idea is carried over from sentence to sentence. Verbal bridges use language — repetition of keywords and synonyms, use of transitions, etc. — that makes the logical connections between your ideas clear to your reader.

Structural Components

Topic sentence.

The first sentence in a paragraph should clearly announce the thesis of the paragraph (i.e., its direction), the claim that will be supported by the content of the paragraph. Effective topic sentences will often link this local claim back to the overall thesis of the essay.

Transitions (Movement)

Transitions are verbal bridges that use language to make the logical movement and structure of an essay clear to the reader. The topic sentence will often contain a transition that links the argument of the paragraph to the one made in the previous paragraph. This is most often accomplished by opening the paragraph with a prepositional phrase or by retaining some important language from the previous paragraph. The final sentence of a paragraph may also suggest a logical link to the argument to come. Transitions do not always link adjacent paragraphs. Good writers will refer back to relevant points made several paragraphs earlier. Especially long or complex papers will often contain several sentences (even entire paragraphs) of transitional material summarizing what the essay has sought to establish up to that point.

Quotations, examples, data, testimony, etc. should be cited as evidence in support of your paragraph’s central claim. In order to avoid generalization, you should strive to use evidence that is as specific as possible. Evidence should be preceded by an introduction to its source and relevance and followed by analysis of its significance to your overall argument.

Evidence alone does not make your argument for you. Evidence requires analysis to make it relevant to an argument. Analyzing effectively requires showing or explaining how the evidence you have cited actually supports the larger claims your essay is making, both on the paragraph level and the thesis level. Because analytical sections are the places where your essay does real argumentative work, they should constitute the bulk of your paragraph (and essay).

Like the conclusion to the essay as a whole, the final sentence of a paragraph is a chance to sum up and solidify for your reader that your paragraph has established the claim it set out to. A concluding sentence will revisit the material from the topic sentence, but with an enhanced perspective.

Example Body Paragraph

Here is an example of an body paragraph that we will analyze sentence by sentence:

Swift undermines Gulliver's negative view of humankind by making his hero devolve, in the grip of that view, into an irrational and sadly comic character, unable to appreciate acts of genuine human goodness. Upon leaving the Houyhnhnms at the end of the story, Gulliver's disillusionment with humanity and desire for withdrawal seem, at first, understandable, if not darkly humorous. He wants to find some "small Island uninhabited" in which to isolate himself from human society, "so horrible was the Idea ... of returning to live in the Society and under the Government of Yahoos" (248). But this disillusionment escalates to sociopathia. When he returns home to his wife and children, "the Sight of them filled [him] only with Hatred, Disgust, and Contempt; and the more, by reflecting on the near alliance [he] had to them" (253). Just as Gulliver is disgusted with humanity, by this point Swift is clearly disgusted with Gulliver. Once affably curious, after his departure from the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver loses touch with natural human feelings, values, and priorities. His wife welcomes him home with love, patience, and forbearance, taking him "in her arms and kiss[ing]" him (253). Instead of embracing her in return, Gullivers falls into a "Swoon" for having been touched by an "odious Animal" (253) — a shameful epithet for a loved one. Rather than trying to integrate himself into human society, Gulliver pathologically withdraws from human contact and spends his time talking to a pair of stable horses (254). Here Swift shows us the danger of an excessive sensitivity to human feelings.

Example Body Paragraph: Structural Components

In this table, each structural component of the body paragraph is listed in the left column, and the corresponding sample text is on the right:

Example Body Paragraph: Analysis

Analysis of each structural component of the example paragraph.

Swift undermines Gulliver's negative view of humankind by making his hero devolve, in the grip of that view, into an irrational and sadly comic character, unable to appreciate acts of genuine human goodness.

Explanation

The paragraph's opening sentence clearly establishes the claim that will be argued throughout: that Swift undercuts Gulliver's rejection of humanity by using his authorial power to turn the hero of his novel into a comical figure of pity. This topic sentence reproduces the tension at the heart of the essay's thesis that "there is an ironic disconnect between Swift as author and Gulliver as narrator and critic of humankind." The topic sentence also forges a subtle transition. The reference to "Gulliver's negative view of humankind" refers back to the central claim of the previous paragraph.

- But this disillusionment escalates to sociopathia.

- Just as Gulliver is disgusted with humanity, by this point Swift is clearly disgusted with Gulliver.

- ... Gulliver pathologically withdraws from human contact and spends his time talking to a pair of stable horses.

Can you see what these three examples have in common?

The logical movement of this paragraph is announced by the word "devolve" in the topic sentence. As the author presents and analyzes the novelistic evidence of Gulliver's mental unraveling, he makes the logic of his argument clear to his reader through the use of effective transitions. The author inserts sentences and phrases into his paragraph that trace Gulliver's path from disillusionment, to sociopathia, to antisocial pathology. The author's transitions also expose the logic of Swift's changing attitude toward Gulliver. It is worth noting that these transitions are full integrated into the author's analysis, simultaneously serving as conclusions to one argument as they form introductions to the next. For example, the line "this disillusionment escalates into sociopathia" sums up the section of the author's analysis dealing with Gulliver's disillusionment while introducing the following section that focuses on his sociopathia.

- He wants to find some "small Island uninhabited" in which to isolate himself from human society, "so horrible was the Idea ... of returning to live in the Society and under the Government of Yahoos" (248).

- When he returns home to his wife and children, "the Sight of them filled [him] only with Hatred, Disgust, and Contempt; and the more, by reflecting on the near alliance [he] had to them" (253).

- His wife welcomes him home with love, patience, and forbearance, taking him "in her arms and kiss[ing]" him (253). Instead of embracing her in return, Gullivers falls into a "Swoon" for having been touched by an "odious Animal" (253)

What do all these examples use as evidence? How does the author present them?

Note how the evidence about Gulliver's welcome by his wife is introduced; the author tells the reader what to look for in the evidence — Gulliver's loss of touch with human feelings, values, and priorities — before presenting it. This makes the paper easier to read because the reader is able to assess the adequacy of the evidence while reading it. In addition, the author is careful to present all of the necessary evidence — both the wife's welcome and Gulliver's reaction — before moving on to analysis. Note, in the use of phrases like "odious Animal," how the author is careful to reproduce the specific pieces of Swift's language that will be relevant for his later analysis.

- Upon leaving the Houyhnhnms at the end of the story, Gulliver's disillusionment with humanity and desire for withdrawal seem, at first, understandable, if not darkly humorous.

- Once affably curious, after his departure from the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver loses touch with natural human feelings, values, and priorities.

- ... — a shameful epithet for a loved one. Rather than trying to integrate himself into human society, Gulliver pathologically withdraws from human contact.

Can you see why we classify these examples of analysis rather than evidence? How can analysis, like transitions, contribute to movement?

The burden on the author to analyze is lightened significantly by the way in which he introduced his evidence. However, he is still careful to reflect analytically on what he has cited. His assessment of "odious Animal" as a "shameful epithet for a love one" goes beyond simply explicating the obvious meaning of this phrase; he also succinctly relates what the use of the phrase "odious Animal" says about Swift's attitude toward Gulliver. In addition, note how the author's analysis mingles illuminatingly with his presentation of new pieces of evidence. The "pathological withdrawal from human contact" that the author derives from Gulliver's reaction to his wife is reinforced by the description of Gulliver's proclivity to socialize with his horses.

Here Swift shows us the danger of an excessive sensitivity to human feelings.

The author makes sure the reader understands the main argument of the paragraph by restating it before moving on. However, the author does not simply reproduce his initial contention that Swift undermines Gulliver's antihumanism at the end of Gulliver's Travels. He pushes his proper claim one step further by turning Swift's rejection of Gulliver into a social commentary. This subtle addition serves as a transition to the following paragraph in which the author discusses Swift's attitude toward human society.

- Drafting and Revision

- Professional Writing

- Resources for Faculty

- Research and Pedagogy

4c. Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs present the reasoning and evidence to demonstrate your thesis. In academic essays, body paragraphs are typically a bit more substantial than in news reporting so a writer can share their own ideas, develop their reasoning, cite evidence, and engage in conversation with other writers and scholars. A typical body paragraph in a college essay contains the following elements, which can be remembered through the useful acronym TREAT.

The TREAT Method

- T opic Sentence – an assertion that supports the thesis and presents the main idea of the paragraph

- R easoning – critical thinking and rhetorical appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos

- E vidence – facts, examples, and other evidence integrated into the paragraph using summaries, paraphrases, and quotations

- A nalysis – examination and contextualization of the evidence and reasoning

- T ransition – the flow of ideas from one paragraph to the next

Effective body paragraphs are:

- Specific and narrow . Topic sentences provide your audience a point of transition and flow from paragraph to paragraph. Topic sentences help you expand and develop your thesis and set up the organization of each paragraph. Developing specific reasoning and specific, concrete examples and evidence in each paragraph will build your credibility with readers. If used properly, well-developed reasoning and evidence are more compelling than general facts and observations.

- Relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Body paragraphs should show, explain, and prove your thesis without delving into irrelevant details. With practice and the understanding that there is always another essay, effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Keeping your audience and purpose in mind when choosing examples will help you make sure to stay focused on your thesis.

- Detailed . Academic paragraphs are typically longer than newspaper and magazine paragraphs because scholars need space to develop their reasoning and provide sufficiently detailed evidence to support their claims. Using multiple examples and precise details shows readers that you have considered the facts carefully and enhances the impact of your ideas.

- Organized . If your paragraph starts to include information or ideas that stray from your topic sentence, either the paragraph or the topic sentence might need to change.

Reasoning and Evidence

In written and oral communication, we demonstrate our critical thinking skills through the various types of rhetorical appeals we make to our audience. The purpose and audience for a writing task shape the way writers develop reasoning and select evidence to support their ideas. Writers develop reasoning in body paragraphs through three primary methods: ethos, logos, and pathos. Writers can deploy many forms of evidence to support their reasoning, including: facts, examples, judgments, testimony, and personal experience.

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle developed a simple method for categorizing forms of reasoning by identifying three primary modes of argumentative reasoning: ethos, logos, and pathos.

- Ethos is reasoning that establishes a writer’s credibility. By showing yourself to be a critical and sympathetic reader, who considers multiple perspectives and demonstrates ethical thinking, you can establish ethos in your body paragraphs.

- Logos is reasoning that develops logical arguments and demonstrates a writer’s command of the facts. Demonstrating your knowledge of the facts and showing that you can distinguish between competing claims at truth will ground your writing in common sense and objectivity.

- Pathos is reasoning that appeals to human emotions and psychological motivations. Humans are subjective animals, and our ability to develop an emotional connection with an audience can have a powerful or subtle impact on whether they will agree with a writer’s reasoning.

A fourth form of reasoning, kairos , can occasionally be used to make an appeal to an audience that the perfect moment or right opportunity has arisen for action. Arguments for changing policies, ending wars, starting revolutions, or engaging in radical social change typically deploy kairos in addition to ethos, logos, and pathos in order to motivate people to take action a critical times in history.

Evidence includes anything that can help you support your reasoning and develop your thesis. As you develop body paragraphs, you reveal evidence to your readers and then provide analysis to help the reader understand how the evidence supports the reasoning and assertions you are making in each body paragraph. Be sure to check with each instructor to confirm what types of evidence are appropriate for each writing task you are assigned. The following kinds of evidence are commonly used in academic essays:

- Facts . Facts are the best kind of evidence to use for academic essays because they often cannot be disputed or distorted. Facts can support your stance by providing background information or a solid evidence-based foundation for your point of view. Remember that facts need explanations. Be sure to use signal phrases like “according to” and “as demonstrated by” to introduce facts and use analysis to explain the relevance of facts to your readers.

- Examples show readers that your ideas are grounded in real situations and contexts. Examples help you highlight general trends and ground your facts in the real world. Be careful not to take examples out of context or overgeneralize based on individual cases.

- Judgments . Judgments are the conclusions of experts drawn from a set of examples or evidence. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and a thorough examination of a topic. Citing a credible expert to support your opinion can be a powerful way to build ethos in your writing.

- Testimony . Testimony consists of direct quotations from eyewitnesses or expert witnesses. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; they add authenticity and credibility to an argument or perspective based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive expertise or experience with a topic. This person provides commentary based on their interpretation of the facts or extensive knowledge on a topic or event.

- Personal Experience . Personal observation is similar to eyewitness or expert testimony but consists of your own experiences and/or expertise. Personal experience can be effective in academic essays if directly relevant to the topic and suited to the purpose of a writing task.

Key Takeaways

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be up to a page long, as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your prewriting and outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas.

Addressing Counterarguments and Different Perspectives

“Few things are more difficult than to see outside the bounds of your own perspective—to be able to identify assumptions that you take as universal truths but which, instead, have been crafted by your own unique identity and experiences in the world.”

~David Takacs

Why acknowledge and respond to other points of view?

- Address potential weaknesses in your argument before others can point them out to you.

- Acknowledge the complexity of an issue by considering different perspectives and aspects of an issue. No issue has a simple solution or is just Side A versus Side B.

- Establish your writing ethos (can your reader trust you?): your reader is more likely to trust you if you thoughtfully analyze an issue from multiple angles.

- Add to your essay’s word count!

Four steps to acknowledging and responding to other points of view

Step one: know your standpoint, what is my standpoint and why should i know it.

- Standpoint is the unique perspective from which you view the world. It includes: your background and experiences, your political and religious beliefs, your identity (gender, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and ability), your relationship to others, and your social privilege. These are things that will affect how you view and understand an issue.

- It’s important to acknowledge your standpoint because it affects what and how you argue.

Good writers are good readers! And good readers. . .

- Who are you?

- Make a list of what you’ll bring to a conversation about the issue on which you’re writing. What are your assumptions, your background and experience, your knowledge and expertise? Be honest!

Consider writing your standpoint into your essay

- Writing your standpoint into your essay builds trust with your readers. Even if they have a different standpoint, they will respect your honesty and hopefully listen respectfully to what you have to say.

- Writing from your standpoint can make your writing feel more authentic , to you and your reader. “This is me!”

Even if you don’t explicitly reveal your standpoint to your reader, you’ll want to know your standpoint so that you are aware of your own implicit bias as you write.

How do I write in my standpoint? Can I use “I”?

Try one of these templates:

- “What concerns me as a business major . . .”

- “I write this essay during a time when . . .”

- “I am concerned about. . .”

See how other writers we’ve read have done it:

- “Now, as a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education , I. . .” [From Anthony Abraham Jack, “I Was a Low-Income College Student. Classes Weren’t the Hard Part.” The New York Times Magazine ]

- “From my first day as a sociology professor at a university with a Division I football and men’s basketball team , education and athletics struck me as being inherently at odds. . .” [From Jasmine Harris, “It’s Naive to Think College Athletes Have Time for School,” The Conversation ]

- “In this society, that norm is usually defined as white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure. It is within this mythical norm that the trappings of power reside. Those of us who stand outside that power , for any reason, often identify one way in which we are different, and we assume that quality to be the primary reason for all oppression. . .” [From Audre Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”]

- “I might not carry with me the feeling of my audience in stating my own belief. . .” [From Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”]

Step Two: C onsider potential weaknesses in your argument and different points of view on the issue

What potential weaknesses in your argument might you address.

- Logic : would a reader question any of your assumptions?

- between your reasoning and your claim: your main unstated assumption

- or between your evidence and your reasoning: is there evidence or types of evidence a reader might be skeptical of?

- Does the reader hold false assumptions about the issue?

- Could a reader give a different explanation of the issue ?

- Could a reader draw a different conclusion from the evidence ?

- Is there a specific reader who would disagree?

What alternative points of view on the issue might you consider?

- How might someone think differently about the issue?

- How might someone approach the issue from a different standpoint?

- What might keep someone from trusting or believing a claim or point you make?

- What might make someone tentative about taking action?

- What might keep a person from having an open mind?

Which one should I choose to address?

It depends on the essay’s length. You might consider 1-2 counterarguments that are most important for you to address in a paper (depending on the length).

- this could be a view your audience/community is likely to hold themselves

- or a common-knowledge one you think everyone will think of while reading

- and of course the one that is most specific to your argument

- if you can get one that fits more than one of these criteria, that’s even better!

What NOT to do when considering a counterargument

Build a straw man counterargument

- A straw man argument is a logical fallacy where the writer misrepresents or oversimplifies someone else’s argument in order to make it easier to refute.

- Writers also create straw man arguments when they make up a potential counterargument that is easy to refute, but isn’t something most people would reasonably believe.

Step Three: It’s time to write your counterargument into your essay

An exemplary counterargument:.

- exists as its own paragraph

- you fully acknowledge and respond to it

- Note: You don’t have to refute a counterargument for your argument to work. Our world is big enough to hold multiple points of view. The paragraph should ultimately support your thesis, but you may amend, qualify, complicate, or open up your claim, which is often why, organizationally, discussion of counterarguments or different points of view work best in the introduction of your essay to set up your claim or as the last body paragraph to lead into your conclusion.

- relates to your audience/community’s likely concerns and interests

- seems like a realistic thing someone might think (is not a straw man or caricature)

- ideally, is specific to your argument, not your topic in general

- considers both sides respectfully

- may be more than one counterargument or different perspective, but you’d need a separate paragraph for each in order to give them full consideration

Addressing a counterargument versus a different perspective

A true counterargument is the opposing claim on an issue:

- Claim: Academic probation does not help students progress.

- Counterargument: Academic probation does help students progress.

Different perspectives might offer different reasoning, consider different factors or conditions, or ask about different groups of people or situations.

A counterargument needs to be rebutted. Different perspectives can help you amend, qualify, complicate, or open up your claim.

You might use a counterargument to qualify your thesis

An example:

Reasoned thesis : Hook-up culture is now at the center of the institution of higher education because it is thick, palpable, the air students breathe, and we find it on almost every residential campus in America. [From Lisa Wade, “Sociology and the New Culture of Hooking Up on College Campuses“]

A counterargument : Research findings suggest that the sexual practices of college students haven’t changed much since the 1980s. [From David Ludden, “Is Hook-Up Culture Dominating College Campuses?”]

Qualified claim : Although sexual practices of college students haven’t changed much in the last few decades , hook-up culture is now at the center of the institution of higher education because it is thick, palpable. . .

Counterargument paragraph : “The topic of my book, then, isn’t just hooking up; it’s hook-up culture . . .” (Wade).

A template for a counterargument paragraph

I recognize that others may have a different perspective than [state your claim*]. They might believe that [state their claim]. They believe this because [provide several sentences of support]. However, [restate your claim and explain in several sentences why you believe the way you do].

*You can also consider counterpoints to your reasoning, evidence, or standpoint.

Step Four: Decide where to organize your counterargument paragraph

Being aware of different perspectives can also help you develop your conclusion paragraph. In your conclusion, you can reaffirm your claim and then:

- amend part of your claim

- qualify your claim

- complicate your claim

- open up your claim

Writing as collaboration

Think of adding in counterarguments or different perspectives as collaborating with others on addressing an issue. . .

Brazuca illustrations by Cezar Berje, CC0

Opening up our minds and our hearts to different perspectives makes us stronger.

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

COMMENTS

A body paragraph is any paragraph in the middle of an essay, paper, or article that comes after the introduction but before the conclusion.Generally, body paragraphs support the work's thesis and shed new light on the main topic, whether through empirical data, logical deduction, deliberate persuasion, or anecdotal evidence.

The body is the longest part of an essay. This is where you lead the reader through your ideas, elaborating arguments and evidence for your thesis. The body is always divided into paragraphs. You can work through the body in three main stages: Create an outline of what you want to say and in what order.

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB) A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: Transition, Topic sentence, specific Evidence and analysis, and a Brief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant) -TTEB! A Transition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading.This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

A strong paragraph in an academic essay will usually include these three elements: A topic sentence. The topic sentence does double duty for a paragraph. First, a strong topic sentence makes a claim or states a main idea that is then developed in the rest of the paragraph. Second, the topic sentence signals to readers how the paragraph is ...

Body Paragraph Structure. There is a standard basic structure of a body paragraph that helps bring together unity, coherence, and flow. This structure works well for the standard five-paragraph format of academic writing, but more creative pieces of writing (like a narrative essay) may deviate from this structure and have more than the standard three body paragraphs.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you'll organize the information within the body. Parts of an essay. The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below. ... paragraphs. For example, you might write ...

Developing Body Paragraphs, Spring 2014. 1 of 4 Developing Body Paragraphs Within an essay, body paragraphs allow a writer to expand on ideas and provide audiences with support for a chosen topic or argument. Under most circumstances, body paragraphs can be divided into three basic parts: a topic sentence, an illustration, and an explanation.

Body paragraphs play an indispensable role in proving the essay's thesis, which is presented in the introduction.As a sequence, body paragraphs provide a path from the introduction — which forecasts the structure of the essay's content — to the conclusion, which summarizes the arguments and looks at how final insights may apply in different contexts.

Constructing Effective Body Paragraphs. A paragraph is a collection of related sentences dealing with a single topic. This handout breaks the paragraph down into its conceptual and structural components. The conceptual components — direction, movement and bridges — form the logical makeup of an effective paragraph.

4c. Body Paragraphs Body paragraphs present the reasoning and evidence to demonstrate your thesis. In academic essays, body paragraphs are typically a bit more substantial than in news reporting so a writer can share their own ideas, develop their reasoning, cite evidence, and engage in conversation with other writers and scholars.