- All Teaching Materials

- New Lessons

- Popular Lessons

- This Day In People’s History

- If We Knew Our History Series

- New from Rethinking Schools

- Workshops and Conferences

- Teach Reconstruction

- Teach Climate Justice

- Teaching for Black Lives

- Teach Truth

- Teaching Rosa Parks

- Abolish Columbus Day

- Project Highlights

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

Book — Non-fiction. By Richard Rothstein. 2017. 368 pages. A history of the laws and policy decisions passed by local, state, and federal governments that promoted racial segregation.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Through extraordinary revelations and extensive research that Ta-Nehisi Coates has lauded as “brilliant” ( The Atlantic ), Rothstein comes to chronicle nothing less than an untold story that begins in the 1920s, showing how this process of de jure segregation began with explicit racial zoning, as millions of African Americans moved in a great historical migration from the South to the North.

As Jane Jacobs established in her classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities , it was the deeply flawed urban planning of the 1950s that created many of the impoverished neighborhoods we know. Now, Rothstein expands our understanding of this history, showing how government policies led to the creation of officially segregated public housing and the demolition of previously integrated neighborhoods. While urban areas rapidly deteriorated, the great American suburbanization of the post-World War II years was spurred on by federal subsidies for builders on the condition that no homes be sold to African Americans. Finally, Rothstein shows how police and prosecutors brutally upheld these standards by supporting violent resistance to Black families in white neighborhoods.

ISBN: 9781631492853 | Liveright

Teacher Testimonials

When our school district embarked on an equity initiative, some teachers had struggled to put it into practice. The initiative builds from the idea that ALL students are welcome as they are and that ultimately ALL students are provided tasks that demand production at higher levels of depth of knowledge (DOK3/4) so that they can communicate like a scientist, mathematician, historian, etc. The “meeting all students as they are…” aspect of the district initiative has been challenging.

To overcome the challenge, I worked with several high school history teachers as an instructional coach and The Color of Law has been eye opening for them. Groups of educators in the district gathered to read excerpts from Color of Law together and reflect on the history of segregation. It helped them collaboratively expand their lessons beyond the textbook and spark more interest all our students.

There are teachers who have lifted excerpts directly from The Color of Law and had students read them alongside the traditional textbook account of the New Deal. We’ve also begun to design activities that allow students to do some of the investigation of dejure discrimination and segregation right here in San Jose, California. The local library has quite a few online resources and our librarians are getting involved as we try to make our Gale Database more student accessible. One of the findings is the Chinatown that was once in the center of downtown and now is buried under the Fairmont Hotel. It’s truly becoming a collaborative project across our staff. We’re looking forward to more discoveries by students who are not only getting a “people’s perspective” but also finding history interesting and important today.

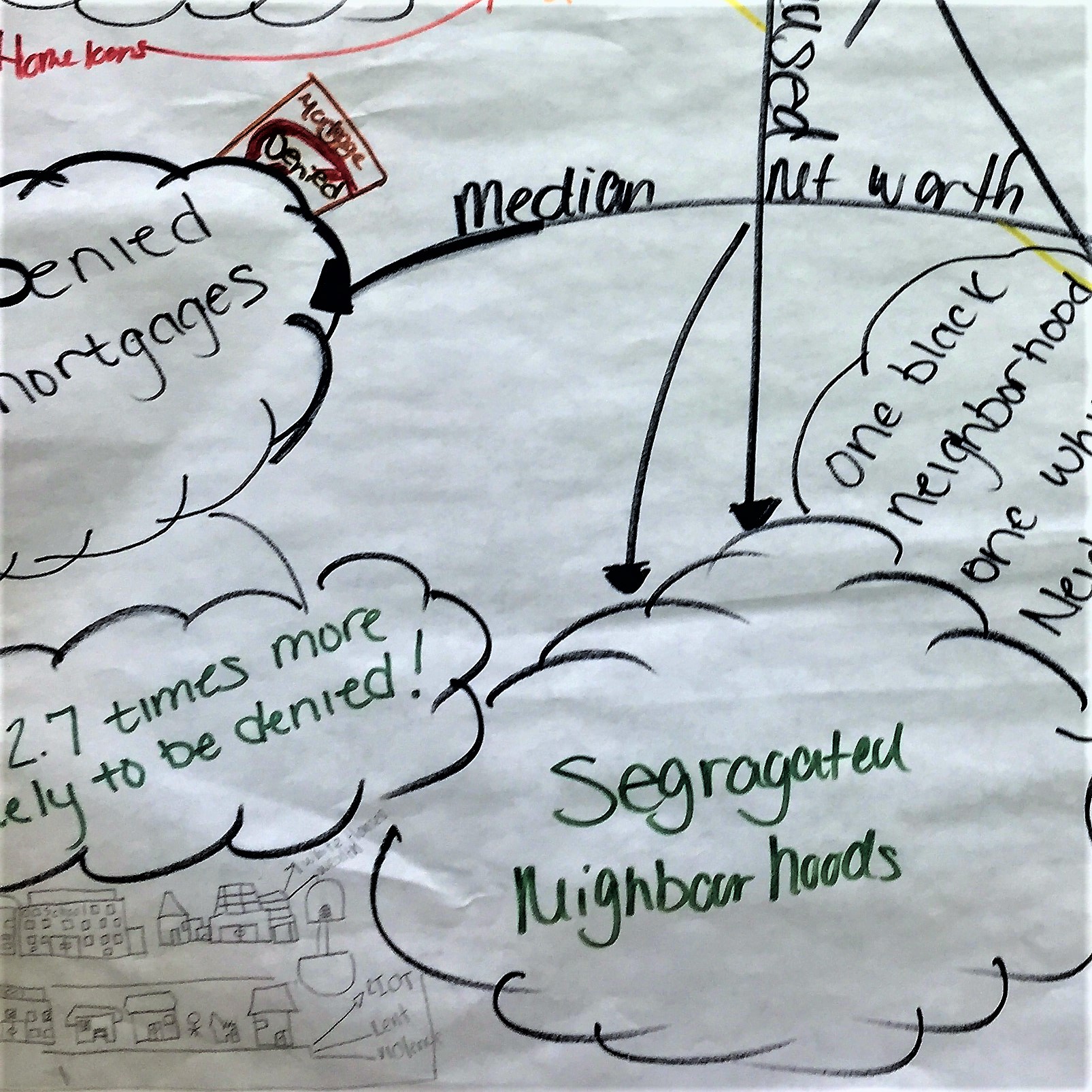

I use excerpts from The Color of Law in addition to excerpts from Thomas Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis to teach about dejure housing discrimination and segregation. Specifically, we focus on the relationship between the government, banks, neighborhood associations and the wealth discrepancy between the races that we see today.

To demonstrate this connection, scholars read sources and develop a “mind map” that shows the relationships. This is especially relevant in Detroit, which has one of the most interesting and volatile history of racialized housing segregation. We start out with general questions that raise scholars already-existent awareness of the issue such as, “where are the best public schools in the area?” “where do people of different races live?” “where are the racial boundaries in Detroit?”

Building on this knowledge, students then come up with their own questions.

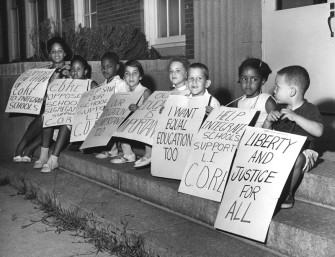

Students’ questions were “how did neighborhoods get segregated?” “why does housing segregation affect school quality?” This naturally led to diving into the texts to answer these questions, looking at demographic maps pre- and post-1967 Detroit rebellion, and reading primary source pamphlets from white neighborhood associations. These issues impact the classroom.

By the end, students realized that segregation was not of individuals choosing necessarily, but rather a planned, coordinated effort by the institutions that exist in the U.S. to keep people separate and to keep the dominant group dominant.

I teach two college courses at South High School in Denver and The Color of Law has been instrumental in discussing housing discrimination and segregation.

In African American history, the intentional government policies that impacted generations of Black and Latino Americans still impact Denver today. We also discussed the book in relation to the Keyes v. Denver (1973) case and subsequent desegregation of Denver Public Schools. Neighborhoods and suburbs in Denver following that decision have left schools more segregated than ever. The concept of community or neighborhood public education is heavily influenced by housing discrimination. Students were engaged and really enjoyed diving deeply into this concept.

This book led to a student-led project idea that we will develop in Denver. Students want to interview residents who were impacted by discriminatory practices and talk about how it has shaped their experiences. Additionally, they want to look at the South High School classes of 1973, 1974, 1975, and 1976 during the first years of busing to talk about how students, teachers, parents, and community members responded to the integration of schools. The Color of Law sheds light on the problems that many cities and communities face today as a result of decades of housing discrimination.

Read more 'Color of Law' classroom stories

Every Spring in my American History classes, I teach our sophomores about the history of housing discrimination and segregation in and around American cities during the 20th Century. I always have the students read an NPR article that excerpts an NPR interview with Richard Rothstein . He succinctly and effectively makes the case that The Color of Law outlines. Housing discrimination and segregation in American cities is a result of de jure, rather than de facto segregation. Rothstein also explains the history and meaning of the word, ghetto, which my students find fascinating.

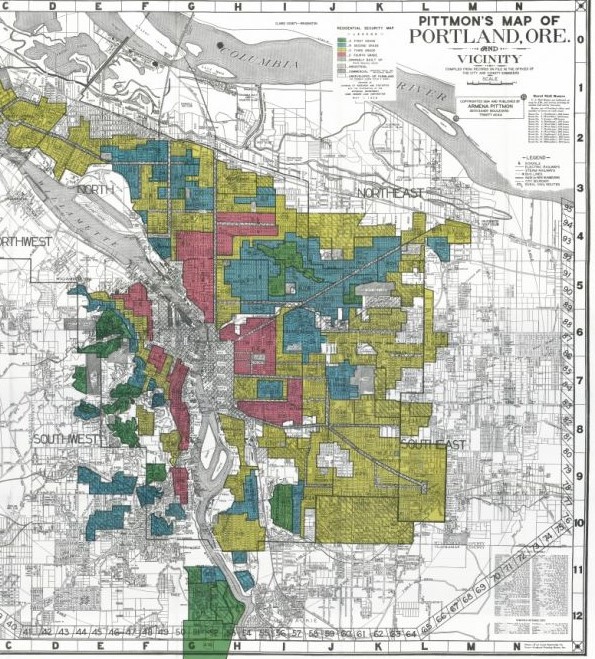

We are a diverse school in Central Illinois, a few hours from Chicago. Our community is closely linked to Chicago, with students and staff having relatives in Chicagoland, or experience living in the city. I have the students explore an online resource of compiled redlining maps from 20th century Chicago , and then we compare these to the current racial dot map of Chicago. This leads the students to want to investigate whether any redlining or other nefarious hiding discrimination still exists. We then begin an inquiry-based search for recent example of housing discrimination, even beyond racial housing discrimination. The Rothstein article is a good jumping off point for a popular lesson.

In my AP English Language class, which focuses on non-fiction, I use several texts to explore systemic injustices including The Color of Law . I use excerpts from Chapter 4, “Own Your Own Home” in conjunction with Chapter 4 from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and ask students to compare how Jurgis and his family suffer exploitation with what happened to African Americans.

I use period pamphlets and maps, particularly redlining maps, so the students can study them using graphic organizers from the Library of Congress or National History Day. It’s important for the students to explore the documents within the framework of Rothstein’s text and a guiding set of questions rather than have me tell them what they’re seeing.

I also incorporate excerpts from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow to compare the explicit government regulations that result in systemic racism with Chapter 5, “Private Agreements, Government Enforcement.” We examine government statutes to determine what the law actually says, as opposed to what is enforced. Bringing in the historical Green Book and excerpts from James Loewen’s Sundown Towns also provide students with sometimes unexpected perspectives from which to consider the past.

In my classroom activity for exploring systematic and institutional racism, students read three excerpts from Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law , watch Episode 3 of Race — the Power of An Illusion , and watch a 2018 PBS NewsHour clip about home ownership in Philadelphia . They also do their own research through internet searches to find statistics and infographics related to gentrification and loan access in the United States.

In the activity I with my students, after class discussions about unearned privilege and definitions of systemic or institutional racism, students brainstorm a list of observations of their own communities they think may be indicative of institutional racism. Students conduct a diversity census of their neighborhood and then search for data that would help answer the question, “Do we have equal opportunity for all races in the US?”

Students then read two Color of Law excerpts (p. 36-37, 64-65) for homework and watch portions of Race — the Power of An Illusion about redlining. In class, they analyz the statistics and graphs to determine what they tell us separately and collectively, what information is missing, what additional questions need to be asked, and what assumptions about race, class, and geography the data affirms or challenges.

After discussions of this material, students explore current estimates on net wealth, and list all the ways that “it takes money to make money” exists: school taxes and school quality, access to additional loans, etc. We then watch the PBS NewsHour clip to see another example of gentrification and students compared that story to their neighborhood census. Finally, they investigate local zoning and property tax laws.

I close the activity by assigning a third excerpt from The Color of Law , the Supreme Court challenges (p. 84-91), as we read or refer back to discussion of the role of the Supreme Court and three anti-canon cases woven into the course.

As a 6th grade class, we have been examining the idea of why people live where they live. I introduce Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law with the quote: “The core argument of this book is that African Americans were unconstitutionally denied the means and the right to integration in middle-class neighborhoods…”

We are a school in a suburb of Chicago, historically one of the most segregated cities in the country. In the lesson, we examined some of Rothstein’s research on redlining (albeit at a 6th grade level), mortgage inequality, and suburban white flight. We also integrated some discussion on modern social inequities such as the economic disparities within our own town (Villa Park): One school has a much higher rate of free and reduced lunch and is that correlated to demographics? Is that correlated to housing policy? Does that correspond to highway corridors connecting to the city (North Ave and Roosevelt Rd)?

As a comparison, I referenced Dr. Eve Ewing’s Ghosts in the Schoolyard which posits on the racism prevailing in Chicago politics over school closings after attending a speaking engagement to bring back information to share with the class.

As an assessment, students played the role of city planner and were tasked with mapping out an inclusive, integrated city complete with human and civil services and housing. They were to provide rationale for the location of their mapping encouraging them to think about not only who lives there but why.

My 8th grade class this year chose to investigate discrimination as part of an emergent curriculum rooted in students’ own questions and concerns. Towards the beginning of their investigations, they read an abridged version of “The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates. They prepared for and participated in a Socratic seminar on the reading. All students were interested in this essay and the stories shared in it, but some felt that it was unfair to ask people today to make reparation or amends for harms done by previous generations of Americans.

In a follow-up activity, I asked students to listen to Richard Rothstein discussing his book The Color of Law with the podcast hosts of “ Have You Heard ?” Students were by then in the early stages of production of a podcast of their own, so this was a good format for them to engage with the content, as they could use this podcast as a partial model for their own. We paused the audio periodically so that I could ask students what they understood about the role of the federal government and federal housing policy in people’s lives. How did federal policies give rise to housing segregation and housing discrimination? How did this limit Black Americans’ access to opportunities to build wealth and economic security? Why were the policies enacted? Who benefited? Who was harmed? How might the policies have had an impact on future generations?

After learning in more depth and detail about dejure segregation, students were much more likely to agree that our government today should play a role in repairing the harms of segregation and discrimination. For some, their concern shifted from the unfairness of white Americans being “punished” for actions of previous generations over which they had no control, to the unfairness visited on Black Americans who were legally barred from using their own resources to secure property and opportunity for themselves and their families.

I have actually used a variation on this lesson across all class levels, from Honors to Standard. It’s even come up in my Humanities and Sociology electives. For the US History classes, I primarily build the lesson around White Flight history in post-war America, where we examine redlining maps and FHA policies in the 1940s and 1950s. Depending on the level, students will do a close reading of some articles related to Rothstein’s book The Color of Law , and discuss whether they think this qualifies as de jure or de facto discrimination and why. The big reveal however, is when we compare the housing segregation problems of the mid-20th century to today, using the Racial Dot Map. When students see the continuing realities of segregation in current US cities and towns, they are completely floored. I’ve even had students research their own college demographics compared to this data to discuss diversity and affirmative action policies.

There’s also a C-SPAN lesson plan available on their educator website that includes some short clips of a book talk between Richard Rothstein and Ta-Nehisi Coates about The Color of Law . The clips are short enough to use with a variety of students at different learning levels. It allows students to not only read portions of the book, but hear Rothstein’s emphasis on what he determined to be the most consequential policies in shaping segregated housing in America.

Related Resources

How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century

Teaching Activity. By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. Rethinking Schools. The mixer role play is based on Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law , which shows in exacting detail how government policies segregated every major city in the United States with dire consequences for African Americans.

Burned Out of Homes and History: Unearthing the Silenced Voices of the Tulsa Massacre

Teaching Activity. By Linda Christensen. Rethinking Schools. 20 pages. Teaching about racist patterns of murder, theft, displacement, and wealth inequality through the 1921 Tulsa Massacre.

Stealing Home: Eminent Domain, Urban Renewal, and the Loss of Community

Teaching Activity. By Linda Christensen. Rethinking Schools. 9 pages. Teaching about patterns of displacement and wealth inequality through the history of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop communities and the building of Dodger Stadium.

“Why Is This the Only Place in Portland I See Black People?”: Teaching Young Children About Redlining

Teaching Activity. By Katharine Johnson. Rethinking Schools. 10 pages. An elementary school teacher introduces the history of redlining through a role play designed for 1st and 2nd graders.

Our House Divided: What U.S. Schools Don’t Teach About U.S.-Style Apartheid

Article. By Richard Rothstein. 2013. If We Knew Our History Series. Housing segregation was not just the product of poverty or even biased attitudes; it was created largely by U.S. government policy.

More Teaching Resources

Advertisement

Supported by

The Color of Law : A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

Book • By Richard Rothstein • 2017

Share this page:

Order the book

You can also purchase the book at Amazon.com , Barnes & Noble , IndieBound.org , or your local bookseller.

In The Color of Law (published by Liveright in May 2017), Richard Rothstein argues with exacting precision and fascinating insight how segregation in America—the incessant kind that continues to dog our major cities and has contributed to so much recent social strife—is the byproduct of explicit government policies at the local, state, and federal levels.

Rothstein was a panelist on an EPI webinar, July 9, 2020, discussing his book and Reconstruction 2020: Valuing Black Lives and Economic Opportunities for All. Click here to see watch the webinar.

The Color of Law was designated one of ten finalists on the National Book Awards’ long list for the best nonfiction book of 2017.

Highlighted media

- Richard Rothstein discusses The Color of Law on Fresh Air

- Richard Rothstein in conversation with Ta-Nehisi Coates

To scholars and social critics, the racial segregation of our neighborhoods has long been viewed as a manifestation of unscrupulous real estate agents, unethical mortgage lenders, and exclusionary covenants working outside the law. This is what is commonly known as “ de facto segregation,” practices that were the outcome of private activity, not law or explicit public policy. Yet, as Rothstein breaks down in case after case, private activity could not have imposed segregation without explicit government policies ( de jure segregation) designed to ensure the separation of African Americans from whites.

A former columnist for the New York Times and a research associate at the Economic Policy Institute, as well as a Fellow at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Rothstein has spent years documenting the evidence that government not merely ignored discriminatory practices in the residential sphere, but promoted them. The impact has been devastating for generations of African-Americans who were denied the right to live where they wanted to live, and raise and school their children where they could flourish most successfully.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 provided modest enforcement to prevent future discrimination, it did nothing to reverse or undo a century’s worth of state-sanctioned violations of the Bill of Rights, particularly the Thirteenth Amendment which banned treating former slaves as second-class citizens. So the structural conditions established by 20th century federal policy endure to this day.

At every step of the way, Rothstein demonstrates, the government and our courts upheld racist policies to maintain the separation of whites and blacks—leading to the powder keg that has defined Ferguson, Baltimore, Charleston, and Chicago. The Color of Law is not a tale of Red versus Blue states. It is sadly the story of America in all of its municipalities, large and small, liberal and reactionary.

As William Julius Wilson has stated: “ The Color of Law is one of those rare books that will be discussed and debated for many decades.”

What readers of The Color of Law have written:

“Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law is one of those rare books that will be discussed and debated for many decades. Based on careful analyses of multiple historical documents, Rothstein has presented what I consider to be the most forceful argument ever published on how federal, state and local governments gave rise to and reinforced neighborhood segregation.” (William Julius Wilson, author of The Truly Disadvantaged )

“Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law offers an original and insightful explanation of how government policy in the United States intentionally promoted and enforced residential racial segregation. The central premise of his argument, which calls for a fundamental reexamination of American constitutional law, is that the Supreme Court has failed for decades to understand the extent to which residential racial segregation in our nation is not the result of private decisions by private individuals, but is the direct product of unconstitutional government action. The implications of his analysis are revolutionary.” (Geoffrey R. Stone, author of Sex and the Constitution )

“A masterful explication of the single most vexing problem facing black America: the concentration of the poor and middle class into segregated neighborhoods. Rothstein documents the deep historical roots and the continuing practices in law and social custom that maintain a profoundly un-American system holding down the nation’s most disadvantaged citizens.” (Thomas B. Edsall, author of The Age of Austerity )

“Through meticulous research and powerful human stories, Richard Rothstein reveals a history of racism hiding in plain sight and compels us to confront the consequences of the intentional, decades-long governmental policies that created a segregated America. The American landscape will never look the same to readers of this important book.” (Sherrilyn A. Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund)

“Racial segregation does not just happen; it is made. Written with a spatial imagination, this exacting and exigent book traces how public policies across a wide spectrum―including discriminatory zoning, taxation, subsidies, and explicit redlining―have shaped the racial fracturing of America. At once analytical and passionate, The Color of Law discloses why segregation has persisted, even deepened, in the post–civil rights era, and thoughtfully proposes how remedies might be pursued. A must-read.” (Ira Katznelson, author of the Bancroft Prize–winning Fear Itself)

“This wonderful, important book could not be more timely. It shows how federal, state, and local government housing policies made the United States two societies, separate and unequal, and used public power to impose unfair, profoundly damaging injuries on African Americans. The book is filled with history that’s been deliberately buried even as its tragic consequences make headlines in Ferguson, Tulsa, Dallas, Staten Island, Charleston―and throughout the country. With its clarity and breadth, the book is literally a page-turner: once one begins on this journey with Richard Rothstein, one is not likely to stop before the conclusion, with a determination that the injustices described must be redressed fully and immediately.” (Florence Roisman, William F. Harvey Professor of Law, Indiana University)

See more work by Richard Rothstein

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

44 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Preface-Chapter 4

Chapters 5-8

Chapter 9-Epilogue

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Compare how de jure segregation was implemented and enforced on the local, state, and federal level. How did discriminatory legislation affect de facto segregation within neighborhoods and in society?

The Color of Law includes examples of de jure segregation from across the United States. Is your community segregated or integrated? How did discriminatory zoning laws shape your community, and do they still exist? How did segregation or integration impact your life? If you live outside the United States, consider other forms of racial, ethnic, or class divisions in housing.

Rothstein makes a forceful case for the importance of knowing the history of segregation, writing, “only if we can develop a broadly shared understanding of our common history will it be practical to consider steps we could take to fulfill our obligations” (198). Using examples from The Color of Law and your own experience, describe what role education plays in antidiscrimination.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Books on Justice & Injustice

View Collection

The Best of "Best Book" Lists

The Color of Law

Richard rothstein, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

In The Color of Law , historian Richard Rothstein notes that every single American city is segregated on racial lines and argues that this segregation is de jure rather than de facto : it is the deliberate product of “systemic and forceful” government action, and so the government has a “constitutional as well as a moral obligation” to remedy it. Planned and implemented by all levels of American government, residential racial segregation impoverishes and disempowers African Americans by confining them to ghettos and blocking them out of homeownership . And this segregation continues well into the 21st century. Since residential segregation pertains to where and how people live their lives, the issue is harder to undo than injustices like the deprivation of voting rights, public services, and equal legal protection to African Americans. To make matters worse, governments, financial institutions, and the real estate industry continue to actively segregate American cities, to African Americans’ disadvantage. Throughout The Color of Law , Rothstein traces the history of this phenomenon in the 20th century and explains what the American citizenry and government must do in this century to remedy it.

In Chapter One, Rothstein illustrates the problem of de jure segregation with the representative story of Frank Stevenson , an African American man living in Richmond, California in the mid-20th century. A former manufacturing town, Richmond grew rapidly during World War II. To keep up with demand, the government built public housing—for white people, it built a comfortable suburb called Rollingwood , but black working families were crowded into “poorly constructed” apartments in industrial neighborhoods, or even left to live on the street. Stevenson worked at a Ford Motor factory, which was soon relocated an hour away to Milpitas after the war. Stevenson was out of luck, because it was impossible for black people to live in Milpitas: Federal Housing Administration (FHA) funds were only allocated to all-white neighborhoods, so while housing options multiplied for white people in places like Milpitas, nobody built housing for African Americans. African Americans were thus confined to certain neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods consequently became entirely African American over time. The government subsequently withdrew services from those black neighborhoods, turning them into the “ slum[s] ” that they remain today.

Rothstein next dedicates one chapter to each strategy the government has used to segregate America over time. In Chapter Two, he looks at public housing, which the government began constructing on a large scale during Franklin D. Roosevelt ’s New Deal . Under these social programs of the 1930s, the government only constructed segregated housing, and only built white housing in white neighborhoods (and vice versa). All across the United States, federal housing programs specifically targeted integrated neighborhoods for demolition and built segregated projects where they used to stand. From the 1950s onwards, as white residents progressively “depart[ed] for the suburbs”—aided by federal mortgage protections exclusively for them—African American became the primary residents of public housing, and now nearly all new public housing is built in predominantly black neighborhoods.

In Chapter Three, Rothstein shows how zoning laws have been used to segregate American cities block-by-block. In the 1910s, cities invented a wide variety of clever laws to prevent white families from buying on majority-African American blocks, and vice versa. Although the Supreme Court outlawed this practice in 1917, cities continued doing it for more than half a century through more underhanded tactics like banning the construction of apartment buildings in white neighborhoods and zoning African American neighborhoods for “industrial” development (or even “toxic waste”).

In Chapter Four, Rothstein explains how government prevented well-off African Americans from moving into white suburbs. Like public housing, homeownership first became truly accessible through the New Deal. Roosevelt’s government began issuing a new kind of loan that was affordable for middle-class Americans, which gradually turned homeownership into a stepping-stone to the middle class—but only for white people. Roosevelt’s administration redlined African American neighborhoods, refusing to issue loans or insure bank mortgages to anyone who lived there.

But Rothstein notes that loan restrictions were not the only factor keeping middle-class African Americans out of the suburbs: in Chapter Five, he recounts the history of “ restrictive covenants ,” contractual clauses that prohibited a property from being sold to nonwhite people. Builders, homeowners, and homeowners’ associations used these clauses to keep neighborhood segregated, with the full support of the Federal Housing Administration. In fact, the FHA continued promoting such covenants even after the Supreme Court ruled them unconstitutional in 1948.

In Chapter Six, Rothstein looks at the actual justification for all this policy: the idea that African Americans moving into a neighborhood “would cause the value of the white-owned properties [there] to decline.” Not only is there no evidence for this claim, but all studies actually point to its opposite: because of segregation and discrimination, African Americans have always had to pay more than white people for the same housing, and they actually increase property values when they move into a neighborhood. In fact, this fact is what allowed the shady practice of blockbusting to thrive: real estate agents scared white homeowners with racist threats of “Negro invasion,” bought white people’s homes for low prices, and then sold the same homes for higher prices to African Americans, often on the predatory contract sale system .

In Chapter Seven, Rothstein explains how the tax system enforces segregation: for a century, the IRS has gladly awarded tax-exempt status to segregationist churches and universities, as well as refused to stop racist practices by banks and insurance companies. This continues into the 21st century: the extension of predatory subprime loans to poor Americans was the principal cause behind the 2008 economic collapse, and government investigations have shown that banks specifically targeted black buyers.

In Chapter Eight, Rothstein shows how local governments can stop integration. He returns to Milpitas, California, where a group spent several years struggling to build an integrated suburb for Ford Motor employees in the 1950s. The “delays, legal fees, and financing problems” the suburb faced from landowners, rival builders, and the local government made it prohibitively expensive. This story is common: U.S. local governments have long used “extraordinary creativity” to exclude African Americans. Historically, local governments have rezoned proposed black neighborhoods as parks, built freeways through them, or (in segregated Southern states) shut down all public services for black people in all but a small part of town.

In Chapter Nine, Rothstein looks at the role of “state-sanctioned violence” in campaigns to prevent integration. From the 1950s through the 1980s, it was not uncommon for mobs of angry white people to camp out on the lawns of black people who moved into their neighborhoods. Numerous black families’ houses were burned down, and the police always either supported the mobs or ignored the victims’ petitions for protection. In many cases, black homeowners were themselves arrested and punished.

In Chapter Ten, Rothstein explains why many black people simply cannot afford to move to white neighborhoods. This, too, is a result of policy: for instance, the government prevented African Americans from accessing employment in the decades after slavery, excluded them from New Deal and post-World War II work programs, and failed to enforce nondiscrimination laws against racist companies and labor unions. Local governments systematically overtax African American communities, who often pay several times what they legally should in property taxes. And housing has always been overpriced in African American ghettos: throughout the 20th century, landlords knew black tenants would pay several times more in rent, compared to white tenants.

In Chapter Eleven, Rothstein asks what it would take to address housing segregation in the present day, which will be a difficult feat because it “requires undoing past actions.” While the 1968 Fair Housing Act removed all legal barriers to integration, the United States remains just as segregated as before, and moving into the middle class remains exceedingly difficult, especially for African Americans. A few additional factors exacerbate this problem: property appreciates more rapidly in white neighborhoods, and most white families bought their first homes before 1973, when wages for most Americans stopped growing. Now, new public housing continues to be built in what are already the poorest and most segregated neighborhoods, and government programs like Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers only exacerbate these neighborhoods’ isolation, rather than funding residents’ integration into middle-class areas.

In Chapter Twelve, Rothstein asks what can be done about residential segregation now . While most Americans are too cowardly or cynical to face history, he argues, it is still possible to push for more integration. He points out easy fixes, like rewriting misleading textbooks and actually enforcing the Fair Housing Act. Then, he offers some concrete policy proposals: the government could sell African Americans homes at lower prices that reflect what they lost out on because of segregation, encourage real estate agents to help integrate neighborhoods, limit localities’ zoning powers, and suspend tax incentives for all-white neighborhoods in order to persuade them to integrate. In fact, some cities have already improved public housing voucher programs on a smaller scale and reaped the benefits of integration in select neighborhoods.

In the Epilogue, Rothstein points out that even the Supreme Court has disastrously misinterpreted American history and declared residential segregation “a product not of state action but of private choices.” This “comfortable delusion,” he concludes, is no longer sustainable, and he summarizes all the profound harms caused by the government’s active segregation of the U.S.

The Color of Law

By richard rothstein, the color of law analysis.

These notes were contributed by members of the GradeSaver community. We are thankful for their contributions and encourage you to make your own.

Written by Maria Stephen

African-Americans have had a tough life in the U.S. In the Colour of Law, Richard Rothstein evaluates segregation, discrimination, injustices, and oppression subjected to people of color in America. Neighborhoods are separated by de jure segregation. In short, all levels of government passed laws that upheld prejudiced patterns.

Despite the Supreme Court banning segregation of cities based on color, legislators enacted policies to certify the separation of blacks from whites. Richard gives the story of Frank Stevenson to justify his claim. Frank was employed at the Ford Motor factory. The government constructed public housing for whites at Milpitas. Frank found it difficult to settle in Milpitas because the place was preserved for whites only.

Richard proposes several actions that need to be taken to end housing segregation. Fair Housing Act should be enforced and the houses belonging to blacks need to be sold at cheap price. Real estate agents should be motivated to assimilate neighborhoods. Tax incentives for all-whites neighborhood should be suspended to compel them to incorporate blacks. The proposals suggested by Richard can help integrate blacks in the neighborhoods belonging to whites. The move can reduce or end residential segregation.

Local, state, and federal governments enacted policies that deliberately enhanced and endorsed housing segregation. Racist policies were endorsed by legislators to promote and enforce the segregation. Whites should prepare to integrate their residential homes with blacks. However, the bigger problem lies in the perception held by whites. Some of these white people believe that integrating their neighborhoods would bring more troubles. Without undoing past mistakes, it will be hard to end racism in the U.S.

Update this section!

You can help us out by revising, improving and updating this section.

After you claim a section you’ll have 24 hours to send in a draft. An editor will review the submission and either publish your submission or provide feedback.

The Color of Law Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Color of Law is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for The Color of Law

The Color of Law study guide contains a biography of Richard Rothstein, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Color of Law

- The Color of Law Summary

- Character List

color of law

Primary tabs.

Color of law refers to the appearance of legal authority or an apparently legal right that may not exist. The term is often used to describe the abuse of power under the guise of state authority , and is therefore illegal . The term was used in the Civil Rights Act of 1871 , where the color of law was synonymous with state action and referred to an official whose conduct was so closely associated with a state that the conduct was deemed to be the action of that state. The Act grants citizens the right to sue government officials and their agents for using their power to violate civil rights . An example is the history of redlining , which can be seen in this map from Syracuse, New York .

[Last updated in July of 2022 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

- civil rights

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- criminal law

- criminal procedure

- civil procedure

- group rights

- legal education and practice

- wex definitions

- Volume 70 Masthead

- Volume 69 Masthead

- Volume 68 Masthead

- Volume 67 Masthead

- Volume 66 Masthead

- Volume 65 Masthead

- Volume 64 Masthead

- Volume 63 Masthead

- Volume 62 Masthead

- Volume 61 Masthead

- Volume 60 Masthead

- Volume 59 Masthead

- Volume 58 Masthead

- Volume 57 Masthead

- Volume 56 Masthead

- Volume 55 Masthead

- Volume 54 Masthead

- Volume 53 Masthead

- Volume 52 Masthead

- Volume 51 Masthead

- Volume 50 Masthead

- Sponsorship

- Subscriptions

- Print Archive

- Forthcoming: 2021-2022

- Special Issue: Law Meets World Vol. 68

- Symposia Topics

Professionalism as a Racial Construct

This Essay examines professionalism as a tool to subjugate people of color in the legal field. Professionalism is a standard with a set of beliefs about how one should operate in the workplace. While professionalism seemingly applies to everyone, it is used to widely police and regulate people of color in various ways including hair, tone, and food scents. Thus, it is not merely that there is a double standard in how professionalism applies: It is that the standard itself is based on a set of beliefs grounded in racial subordination and white supremacy. Through this analysis, professionalism is revealed to be a racial construct.

This Essay examines three main aspects of legal professionalism: (1) threshold to withstand bias and discrimination, (2) selective offense, and (3) the reasonable person standard. Each Subpart starts with a day in my life as an attorney to illustrate how these elements play out. The final section details ways to disrupt professionalism as a racial construct.

Introduction

On a Friday afternoon, I appeared with a colleague in New York City Housing Court on behalf of a client in an eviction proceeding. Aside from the unfortunate nature of the case, it was supposed to be a routine court appearance. But Housing Court is known to be unpredictable, and that afternoon, it lived up to its reputation. While appearing before the judge, opposing counsel—a white woman—yelled at me, interrupted me, talked over me, sighed and rolled her eyes when I spoke. Before this appearance, we had only seen each other in passing. Dumbfounded, I spent half of the time making legal arguments and the other half wondering whether my presence in court, as a Black woman, was the main factor in the attorney’s scorn. Curiosity inched closer to certainty when I learned that my junior colleague, who is white, appeared by herself on the same case just weeks before. We danced around it—“That was ridiculous!” “Oh man, Housing Court”—until we finally made our way to: “She wasn’t like that with me. She treated me with respect.”

That weekend, still reeling from humiliation, I reimagined the court appearance. Would I have appeared too sensitive if I said that opposing counsel’s conduct is racist? Is it professional to use the court’s time to address racism and misogynoir when the negotiations for my client are still in progress? The answers were unclear, but what was certain was that if I had behaved like opposing counsel, I would have been seen as unprofessional and aggressive, and likely admonished by the judge. [1] Professionalism was a one way street—it applied to me but not my opposing counsel.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to tell both the judge and opposing counsel that they upheld systems of racial hierarchy. I did not. Instead, I shouted words on paper.

These words are my screams.

I am one of the 4.7 percent of Black attorneys in the United States [2] and have been practicing law for the past decade. [3] In this Essay, I question whether professionalism is a tool to subjugate people of color in the legal field. Professionalism encompasses: (1) communication style, (2) interpersonal skills, (3) appearance, (4) how well a person adheres to the standards of their field and employer, and (5) efficacy at the job. Through this analysis, professionalism is revealed to be a racial construct.

The canon of Critical Race Theory shifted the understanding of racism from intentional hatred by individual actors to a set of systems and institutions that produce racial inequality and subordination. [4] Criminal justice is a system of laws and individuals who enforce them. While everyone is beholden to the laws, the criminal justice system disproportionately ensnares people of color within its grasp, resulting in harsher punishment. Similarly, professionalism is a standard with a set of beliefs about how one should operate in the workplace. While professionalism seemingly applies to everyone, it is used to widely police and regulate people of color in various ways including hair, tone, and food scents. [5] Thus, it is not merely that there is a double standard in how professionalism applies; it is that the standard itself is based on a set of beliefs grounded in racial subordination and white supremacy.

In Part I, I examine three main aspects of legal professionalism: (1) threshold to withstand bias and discrimination, (2) selective offense, and (3) the reasonable person standard. Each Subpart starts with a day in my life as an attorney to illustrate how these elements play out. Professionalism in the legal industry often carries the silent expectation that people of color, women, people with disabilities and people who identify as LGBTQIA have a high threshold to withstand discrimination. [6] Professionalism as a racial construct is not limited to attorneys and paralegals—it also extends to individuals participating in the legal process. For example, Black people have been excluded from serving on a jury because they “failed to make eye contact, lived in a poor part of town, had served in the military, had a hyphenated last name, displayed bad posture, were sullen, disrespectful or talkative, had long hair, wore a beard”—many of which are under the guise of professionalism. [7] In addition, I discuss how harmful and racist behavior in the legal profession are normalized to the point that challenges to such conduct are seen as unprofessional. Lastly, I analyze how the law functions in a colorblind fashion, having the effect of making any emphasis or focus on race seem impolite or—unprofessional. In Part II, I explore recommendations of how to deconstruct professionalism as a tool of white supremacy.

I. Constructing the Concept of Professionalism in the Legal Profession

a. bias and discrimination threshold.

In June 2018, a group of legal service organizations sent a letter to the Supervising and Administrative Judges of Housing Court. Typewritten words on paper laid bare the experiences that many tenant attorneys and paralegals endured for years: over eighty examples of alleged bias, microaggressions and incivility which took place in Bronx Housing Court by landlord attorneys, court clerks, officers and judges. [8] The purpose of the letter was to demand accountability. As a result, the Supervising Judge convened a meeting for tenant and landlord attorneys to discuss bias and incivility.

More than anything, this meeting revealed that there were at least two perceptions of what it meant to be a professional attorney. In one view, an attorney’s inability to laugh and move along from microaggressions indicated that they were too unpolished or hypersensitive for the field. In the other, an attorney was race and equity conscious and when those norms were eschewed, readily called for accountability to create a workable and inclusive environment. During the meeting, it became clear that the former had been the standard for many years.

Professionalism was based on the notion that one withstood microaggressions and bias with grace and lightheartedness. The higher the threshold one had to tolerate bias, the more polished the attorney or paralegal appeared. This was particularly the case for women, [9] people of color, LGBTQIA people, and people with disabilities. Professionalism as a racial construct manifests itself in two ways. First, that professionalism is measured by how well a person adapts to a hostile work environment is in of itself a racial construct because that system is built for people of color to fail. Second, that professionalism incorporates the ideology to have a thick skin manifests as a racial construct because even the definition of thick skin aligns with who holds the most power. For example, if attorneys on the receiving end of microaggressions, bias, and racism are considered sensitive for not laughing along, why are the attorneys who engage in harmful behavior not also considered sensitive for their inability to handle criticism about their conduct? Thus, even in defining tolerance, whose feelings are prioritized and validated and whose are minimized within the context of professionalism shapes the narrative that people of color—not their white peers—need to develop thicker skin.

It was not coincidental that this meeting took place almost a year after the passage of the right to counsel law, which provides low-income tenants the right to free legal representation. [10] With the city’s investment, there was a new legion of attorneys and paralegals of color in court that stood apart from the mostly white male landlord bar, many of whom had practiced in housing court for a decade of more prior to the demographic shift. [11]

These views on professionalism were not neatly cut along landlord and tenant attorney lines, or even by race. There were larger issues at play here. In the American capitalist economy, enduring a toxic and abusive work environment can be a rite of passage in some workplaces. Even in the sphere of public interest law, a gripe about the astronomical case dockets could be met with quips that “back in my day, I had two times as many cases.” In both the nonprofit industrial complex and law firms, the measure of a good attorney was not only how much of an impact they had on their clients’ lives, but also the quantity of cases they were able to handle at once. [12] In fact, some would say that a high number of cases is the impact. Beyond enduring microaggressions, racism and other discriminatory behavior, there seemed to be a wider expectation to tolerate abusive practices that was woven into the fabric of the American workforce.

In an attempt to navigate Housing Court better, I sought guidance from Black attorneys whom I admired and revered. They all practiced in different areas of law for over a decade. Their advice all started with “Don’t let them make you look unprofessional.” I spoke with at least ten Black attorneys with decades of experience in courtrooms and every single one understood and iterated that despite white opposing counsels or peers acting in the most inappropriate and unprofessional manner, I was the one who would look unprofessional if I came close to or matched their behavior. Professionalism did not apply to them, but it applied to me. Moreover, since racism permeated the profession, consistently complaining or challenging it would not necessarily indicate that it was pervasive; instead it would likely reflect that I was not cut out to be an attorney.

None of these attorneys advised me to file grievances. Racism is a reality and dealing with it meant survival. Survival meant avoiding direct challenges to racism which could lead to negative career consequences. Reflecting on their words, it became clear to me that they began their legal careers at a time when there were even fewer Black attorneys, and in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Act and other laws. There had been so much fight to get their foot in the door that appearing unnerved was not an option. Most advised indirect ways to challenge macro- or microaggressions—speedy, humorous comebacks in response to certain situations to assert dominance and show I was impermeable to anyone’s discomfort of my existence. If I was mistaken for my client or any other Black person, a response could be, “Well, I can tell you apart from Brad Pitt. Now, where’s the rent breakdown, Charles?”

I followed their approach, but its effectiveness quickly wore off. At the time, I was a new staff attorney making $50,000 with a docket of nearly forty eviction cases. I was navigating my own emotions of sometimes overhearing in Spanish in court “I’m getting evicted but at least I’m not Black,” and dealing with helping many of those same tenants navigate the bureaucratic maze of government agencies. The job presented a rude awakening that the role of staff attorney also included hidden duties such as social worker, government agency advocate, and case administrative coordinator. Given the breadth of the position, I did not have the energy or bandwidth to engage in witty banter with opposing counsel during routine negotiations—it felt like playing the sassy Black woman and providing a form of entertainment where I was not the one amused. [13]

Moreover, the societal expectation of Black forgiveness seemed to be endemic to having a thick skin in the workplace. [14] Fear of Black rage spurred vagrancy and loitering laws, after all. [15] Black forgiveness soothed anxiety that there was not any rage, thus hug your brother’s murderer, proclaim a church bomber has been forgiven—be gracious and dignified. The question remained: Why did I have to build my tolerance threshold to acclimate to a hostile environment but the people creating that environment could remain the same?

Perhaps the greatest irony is that the threshold standard is seen in the remedy for discrimination itself. The American Bar Association adopted a rule that incorporated discrimination as misconduct. Under 8.4(g), it is professional misconduct for a lawyer to:

[E]ngage in conduct that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know is harassment or discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status or socioeconomic status in conduct related to the practice of law. [16]

Most states have adopted the ABA ’s rules on professional conduct, thereby incorporating a measure for disciplinary procedures. The Chair of the Committee on Standards of Attorney Conduct of the New York State Bar Association stated: “Although Rule 8.4(g) does not expressly state that a complainant must exhaust administrative and judicial remedies before filing a discrimination complaint with a grievance committee, that is how the rule operates on a practical level.” [17] The expectation to exhaust all remedies before filing a complaint under the rule effectively operates to force individuals to withstand bias and discrimination for a longer period of time than they would if they immediately sought relief. The abusive conduct is deprioritized, and the burden is placed on the complainant to prove that they tolerated a sufficient amount of it.

One of the main mistakes of the legal profession is to approach bias and discrimination complaints as personality conflicts. For example, sexual harassment in a legal office may be seen as two attorneys who do not get along rather than one lawyer harassing the other. Since attorneys, particularly from a marginalized group, are expected to have a high threshold to absorb bias, the imbalance of power in these situations may be ignored. The same happens in the courtroom. In my case when opposing counsel yelled and talked over me, the judge kindly asked her at least eight times to allow me to finish my sentence. There was no admonishment: “If you do not stop, I will hold you accountable, hold you in contempt, or stop the proceeding.” Instead, it appeared as two attorneys sparring during a case rather than abusive and unprofessional behavior that should be addressed to prevent further disruption. Treating racist, misogynistic, transphobic, or other discriminatory behavior as two people in disagreement equalizes behavior where there is often an imbalance of power. The effect is that it allows the decisionmaker—whether it be a judge or head of a legal office—to avoid taking responsibility for stopping the unprofessional conduct.

B. Selective Offense: Constructing What Is Unprofessional

In a meeting, a white male colleague called me derogatory names. I reacted the way many do during an attack: I froze. This behavior was not new for him and as it wore on, my bias threshold reached its capacity. Later that day, I challenged his behavior openly as misogynistic and racist. He was clearly unprofessional—or so I thought. As I sat in various conversations processing while simultaneously explaining what happened, reality slowly sunk in that his behavior was not offensive to everyone. Lips moved, but I only heard garbled words in twos: “team player,” “get along,” “minor bump,” “take personally,” “right approach.” These words pieced together an ugly truth—one that my elders long warned. Some are more offended by a Black woman challenging racism than by a white person perpetuating it.

Selective offense is the normalization of racist, misogynistic, ableist or otherwise discriminatory behavior while the denunciation of said behavior is seen as disruptive. For example, this is seen when employees sit in meetings for months or years with a known problematic colleague who engages in harmful racist, misogynistic, or transphobic behavior and take no action to meaningfully admonish or halt the behavior; yet the same employees are suddenly—or selectively—offended when someone from a marginalized group challenges the problematic employee’s behavior. This manifests professionalism as a racial construct because the problematic employee who engages in racist, misogynistic, or transphobic behavior is not deemed unprofessional, yet the tone, approach, and timing of the person who challenges said behavior is so scrutinized. [18]

There are four stages to selective offense. First, people minimize and fail to admonish the harmful behavior. Second, people impute charm or innocence to the harmful behavior. Even the most clear-cut inappropriate behavior could be likened to humor or quirk. Not deemed harmful, it is instead attributed to the personality of the person perpetuating the harm. The distinction between personality and behavior is crucial because many believe a person can correct another’s behavior—but not their personality. Third, people accept the harmful behavior. Fourth, any challenges to the harmful behavior are seen as a personal character attack rather than rectifying harm.

During my tenure in the legal field, I have observed how these four stages unfold, particularly when the person engaging in harmful conduct is a white male. Once in conversation with attorneys, one mentioned a white male judge who was known to have a moody disposition. He remarked with a chuckle, “We call him Grumpy Grandpa.” The judge’s disgruntled disposition was transformed into a charming quirk that humanized him. For all intents and purposes, his behavior was unprofessional. A judge’s demeanor is essential to the role, especially when interfacing with litigants who are traumatized or stressed by the eviction process. Yet not only was the harmful effect ignored, it was turned into an attribute of his personality. There is also another layer as to why this harmful behavior is attributed to charm or humor. The act of humiliating, regulating, or rebuking people of color, especially in a public setting, has historically been a form of entertainment. From lynching as an American pastime to interactions with the police to degrading interactions in the workplace, inflicting pain on people of color is a public sport. Thus, when a person perpetuates this harm, they are seen as humorous because their actions are amusing for some to watch.

This begged the question: If a person of color or woman judge came in every day for years with a grouchy disposition, would they also be likened to charming or would they be perceived as unprofessional and temperamental? [19] Conversely, I have also observed some judges of color attempt to implement order in their courtrooms by chiding attorneys who engage in conduct that is racist, misogynistic, or otherwise discriminatory. In response, their judicial temperament and bias threshold are scrutinized as much or more than the attorneys’ harmful conduct. It is yet another example of how inappropriate behavior is normalized.

An additional contributing factor to selective offense is the use of public interest work as cover for racism or bias. Why challenge a person’s harmful behavior when they are supposedly doing the work of social or racial justice? [20] The “my best friend is Black” defense to allegations of racism becomes “my clients are Black,” “my staff is Black,” or “my courtroom litigants are Black.” Proximity to people of color or any marginalized group is weaponized to inoculate the person engaging in harmful conduct. And so it becomes offensive and even unprofessional when a person identifies racism against such a person. The spoken truth: “I’m not like the virulent racists on our TV screen.” The unspoken truth: “I could be like them thus I deserve recognition for even moderately attempting to be racially aware.”

C. Justice Is Blind and the Reasonable Person Is White

On June 1, 2020, I learned that police officers killed a Black man in Minneapolis. Against my better judgment, I watched the video of the murder circulating on social media. The video depicted hatred, violence, and a visual display of antiblackness.

During the first days after George Floyd’s murder, I questioned whether everyone watched the same video. There was unusual silence in the American workplace, including the legal sector. I am part of many different communities in the legal profession such as working groups, boards, and coalitions. Routine business emails continued. Since I spent years internalizing the bias threshold discussed in Subpart I.A, I began to wonder whether I was unprofessional for my inability to complete work due to trauma. I was jarred back to reality in an unexpected way. A former client of mine, a Black woman, emailed me: “Ms. Goodridge, with all that’s going on, I just wanted to see if you were okay.” I had been operating on the lie that I was justified in ignoring the pangs of anxiety quietly roaring inside of me while I continued working to protect my clients. In five words—“with all that’s going on”—my client forced me to confront the underbelly of American racism. In that moment of vulnerability, I replied that I was not okay. She responded with a lengthy Bible passage and words of encouragement that we will get through this.

I called Black colleagues and friends who also worked in public interest law in various positions to inquire if they were experiencing the same silence. I was not alone. One friend said, “I just saw a Black man get lynched on television and people are sending emails about service and motions. What is going on ?” In almost all instances that I knew of, legal organizations were mostly silent until a person of color raised that the murder of George Floyd required more than a cursory mention—this was a racial reckoning.

Many people adhere to the axiom that discussion of politics in the workplace must be avoided in order to maintain a harmonious environment. In the legal profession, however, it goes beyond politics. Lawyers have been taught for centuries that thinking like a lawyer means putting all emotions aside. [21] Divesting of emotion for the sake of legal reasoning in and of itself is an exercise of privilege. For example, law students have been forced to complete exam questions that reenact situations such as Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri. [22] Even the way law students are taught to view defendants and their circumstances is through the narrow prism of the reasonable person standard. The reasonable person is supposedly a raceless and genderless blank slate which parallels with the ideology that justice is blind. However, stripping identity from the reasonable person means that whiteness becomes the norm and lens which legal advocates look through. Though fictional and imaginary, the reasonable person in “its present manifestation, applied within the trappings of the past, becomes less reflective of the population that will soon become the majority, becomes less legitimate if law’s purpose is to serve the People.” [23]

Even in antiracist, progressive spaces, I observed how the law was envisioned as motion-writing, research, and oral arguments while racial and social justice were ancillary. Activities such as attending a protest related to the attorney’s field or engaging in racial justice learning were seen as additional tasks to the legal work—even though they helped an attorney to have cultural competency to better understand their clients. I also observed that courts often inferred a dichotomy between the fields of housing and fair housing. Housing denotes Housing Court, which typically handles eviction and repair cases. Fair housing applies to cases pertaining to antidiscrimination laws such as the Fair Housing Act. In my experience, housing operates in a more colorblind fashion than fair housing. Some legal organizations have a racial justice best practice to name the client’s race in legal motions. Other than the mention of a client’s race in a motion, race or the role it plays is rarely emphasized in housing cases, even in a practice where people of color comprise the majority of tenants facing eviction, the effects of gentrification and systemic racism. [24] In contrast, a client’s disability, income and contours of reasonable accommodation are more readily understood. I noticed that the actual teaching of race discrimination was not common and often referred to as a fair housing issue, even if the legal claims pertaining to race were squarely in legal codes related to eviction. This, of course, is a function of how the law and the reasonable person centers whiteness.

This occurs in other areas as well. After the murder of George Floyd, many legal institutions such as law firms, courts, and legal service organizations provided ongoing antiracism initiatives for their employees. Though there are multiple ways to discuss antiracism, equity, and inclusion, I noticed that in many instances, the framing focused almost entirely on white allyship. This meant that there were only rudimentary discussions of racism, (centering questions like: What does racism look like?) which did not allow for a more nuanced understanding of concepts like colorism, featurism, intraracial violence, and intersectional identities. [25] In addition, the tailoring of racial justice education for a white audience often resulted in examining race only through a Black and white binary. This excluded other racial groups such as Asian American and Pacific Islander and Native American. As a result, the only way for people of color in those rooms to participate was to be of service to the learning experience of their white peers rather than to process their own pain or even learn themselves. [26] This functions to make the purpose of the presence of marginalized groups to be useful to the education of their white peers. [27]

In fact, when I later asked non-Black people why there was stifling silence when the news first showed the murder, the responses were: “I did not know what to say,” “I did not feel I had license to speak because I am not Black,” “I thought it might be impolite to raise this topic at work,” and “I did not think it was related to our work of eviction.” Attorneys who represent people of color everyday still felt they did not have license to talk about race. This is a systemic reflection of how legal practice functions in a largely colorblind fashion.

II. Accountability: Deconstructing Professionalism as a Racial Construct

After laying out my experiences and thoughts on professionalism as a racial construct, it is time for you to take action. The first step is to absorb this Essay in its entirety and identify what your role has been: target, bystander, accomplice, challenger, or perpetuator of professionalism as a racial construct. If it is difficult to identify your role, ask yourself how you are reacting to this Essay. Are you defensive? Ready to share it privately to an individual colleague? Ready to share it publicly to all of your colleagues? Or are you reticent about sharing this Essay with colleagues because you believe it will negatively impact your career? Will you ignore this Essay entirely? How you react to this Essay—the experiences of a Black woman attorney speaking on professionalism as a tool for white supremacy—may correlate with the role you play in challenging it within your own institution.

Next, send the Essay to family or friends to discuss ways that you can (further) challenge professionalism as a racial construct. The basis of professionalism as a racial construct is the belief that the racial hierarchy which produces the phenomenon will remain the same and that practitioners will adapt to it rather than challenge it. Since it has been deeply inculcated into the legal practice and American workforce, these conversations may prove difficult and enlightening because fear of change undergirds much of the perpetuation of professionalism as a racial construct.

The next step is to send this Essay to your colleagues for a discussion at the next staff meeting. You can discuss the Essay generally or discuss the Subparts over multiple meetings. The main question should be: How does professionalism as a racial construct manifest at this institution?

Moving forward, in order to disrupt professionalism as a racial construct, you must name it by using the framework in this Essay to identify the conduct as it happens. For example, you can say:

Why are you so bothered that Jane, a Black woman, called out an attorney for his racist conduct but you do not have this same reaction towards John, a white man, who still cannot correctly pronounce the names of people of color after ten years of working here? This seems like selective offense. Your Honor, opposing counsel has interrupted me several times and there has been no warning of contempt or forcing them to leave the courtroom. Are my client and I expected to silently endure this—a high bias threshold—during this proceeding? Respondent is Chinese American and lives in the Soho section of New York. The area has historically been comprised of 70 percent Asian American and Pacific Islanders; however in the last decade, that population has drastically declined due to gentrification, redlining and displacement. This eviction case is not divorced from that. Respondent would like to remain in her community.

In writing this Essay, I had an internal tug of war in speaking about my experiences and those of many people of color in the legal profession. I struggled with the reality that some will be more offended by reading the truth of professionalism as a racial construct on these pages than the fact that it exists in the halls of courthouses, law firms and legal organizations. I almost quelled my own voice and the fire within. Then I remembered the court appearance in 2020, after George Floyd’s murder, where the Black judge and I both had weary eyes which met, for a moment, as opposing counsel rattled on about the eviction moratorium. I remembered brunch with friends when they spoke about being the first generation of Black, Latinx, and Asian immigrant parents and internalizing the bias threshold—sacrifices their parents made to come to this country meant ignoring and tolerating racism at work. I remembered the many times I watched people of color shy away from staunch racially progressive positions under a belief that disassociation would help them appear more professional. I remembered the conversations with relatives, friends, and colleagues of color, venting and processing a racist incident and in determining how to respond, the pendulum swinging between comfort of white peers, self-respect, and rage. And I remembered using chemicals to destroy and straighten my natural hair during job interviews in law school in the hopes of increasing my chances of securing employment. I remembered all of these contours of professionalism as a racial construct. And I remembered my own duty to disrupt the system and get in good trouble.

[1] . See Amanda Luz Henning Santiago, How Can New York Change Its Court Culture? , City & State N.Y. (Oct. 27, 2020), https://www.cityandstateny.com/politics/2020/10/how-can-new-york-change-its-court-culture/175516 [ https://perma.cc/W3DP-PH5C ] (“For many working within the court system, it’s understood that in order to maintain a sense of professionalism, employees have to ignore blatant racism. ‘It (racism and sexism) has become so ingrained into the culture (of the court system) that there is an underlying and silent expectation that people just put up with it and it’s part of being professional, having a thicker skin,’ Leah Goodridge, a supervising attorney at Mobilization for Justice, who has spent years working in Housing Court, told City & State. ‘So instead of people challenging the racist behavior, for example, the burden has shifted to the person who bears it—and that is not limited to attorneys; sometimes it’s judges as well.’”).

[2] . See Am. Bar Ass’n, Profile of the Legal Profession 2021 (2021); see also Karen Sloan, New Lawyer Demographics Show Modest Growth in Minority Attorneys , Reuters (July 29, 2021, 3:12 PM), https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/new-lawyer-demographics-show-modest-growth-minority-attorneys-2021-07-29 (last visited Mar. 20, 2022).

[3] . Deborah L. Rhode, Law is the Least Diverse Profession in the Nation. And Lawyers Aren’t Doing Enough to Change That. , Wash. Post (May 27, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/ wp/2015/05/27/law-is-the-least-diverse-profession-in-the-nation-and-lawyers-arent-doing-enough-to-change-that [ https://perma.cc/P6S6-F6YU ].

[4] . Richard Delgado, Liberal McCarthyism and the Origins of Critical Race Theory , 94 Iowa L. Rev. 1505, 1511 (2009).

[5] . See Shannon Cumberbatch, When Your Identity is Inherently “Unprofessional”: Navigating Rules of Professional Appearance Rooted in Cisheteronormative Whiteness as Black Women and Gender Non-Conforming Professionals , 34 J.C.R. & Econ. Dev. 81 (2021).

[6] . Dylan Jackson, George Floyd’s Death Ushered in a New Era of Law Firm Activism and There’s No Going Back , Am. Law. (May 25, 2021, 5:00 AM), https://www.law.com/Americanlawyer/2021/05/25/george-floyds-death-ushered-in-a-new-era-of-law-firm-activism-and-theres-no-going-back-405-84104 [ https://perma.cc/P7A3-V8CZ ].

[7] . Adam Liptak, Exclusion of Blacks From Juries Raises Renewed Questions , N.Y. Times (Aug. 16, 2015), https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/17/us/politics/exclusion-of-blacks-from-juries-raises-renewed-scrutiny.html [ https://perma.cc/WR97-4T2N ].

[8] . The examples included court staff frequently mistaking attorneys for litigant-respondents or confusing two people of color, opposing counsel yelling or making racist comments. Many of the experiences noted in the letter were later reflected in a wider and first of its kind report on racism in the courts published in 2020. Jeh Charles Johnson, Report From the Special Adviser on Equal Justice in the New York State Courts 61–66 (2020).

[9] . The roots of the “toughen up, buttercup” mentality for women as lawyers run deep. See, e.g. , Maryam Ahranjani, “ Toughen Up, Buttercup” Versus #TimesUp: Initial Findings of the ABA Women in Criminal Justice Task Force , 25 Berkeley J. Crim. L. 99, 108 (2020) (“In the 1920s, the President of the Women’s Bar Association reportedly told recently admitted women to never let anyone refer to them as a ‘woman lawyer’ because that in and of itself is an obstacle to practice. The idea was to mimic men as much as possible in order to fit in.”).

[10] . Press Release, New York City Office of the Mayor, New York City’s First-in-Nation Right-to-Counsel Program Expanded Citywide Ahead of Schedule, (Nov. 17, 2021), https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/769-21/new-york-city-s-first-in-nation-right-to-counsel-program-expanded-citywide-ahead-schedule [ https://perma.cc/JS3E-E6GL ].

[11] . After a white male landlords’ attorney referred to COVID -19 as “Chinese cooties” in a long email chain including judges, landlords, and tenants attorneys, several articles were published describing the incident. See Jane Wester, Racist Comment by New York Landlords’ Attorney is Symptom of Larger Problem, Bronx Tenants’ Lawyers Say , N.Y. L.J. (Aug. 31, 2020, 5:57 PM), https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2020/08/31/racist-comment-by-new-york-landlords-attorney-is-symptom-of-larger-problem-bronx-tenants-lawyers-say (last visited Mar. 19, 2022) (“Several tenants’ attorneys said Rogers’ comment was an example of pervasive behavior they face in Bronx Housing Court. The number of tenants’ attorneys working in housing court has grown since the city passed its Universal Access to Legal Services law in 2017, and the tenants’ bar tends to be younger and more diverse than the landlords’ bar, which is largely white and male, several lawyers said.”).

[12] . See generally The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond The Non-Profit Industrial Complex (INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence eds., 2017).

[13] . One example of a macro-aggression is when a landlords’ attorney filed at least forty eviction cases in Housing Court with termination notices referencing coronavirus as the “Chinese Wuhan Virus.” The Court dismissed almost all of the notices. In an article for a legal publication, the landlords’ attorney declined to comment on the offensive conduct but did say “I’m just waiting for them to pass universal rent control where they completely take away landlords’ rights to do what they want with private property.” See Emma Whitford, NYC Eviction Judge Tosses Cases with “Wuhan Virus” Notice , Law360 (May 21, 2021, 9:54 PM), https://www.law360.com/realestate/articles/ 1387338/nyc-judge-tosses-eviction-cases-with-wuhan-virus-notice [ https://perma.cc/CZ7U-Y7J2 ].