Critical Thinking Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Effective Decision Making

Critical thinking models are valuable frameworks that help individuals develop and enhance their critical thinking skills . These models provide a structured approach to problem-solving and decision-making by encouraging the evaluation of information and arguments in a logical, systematic manner. By understanding and applying these models, one can learn to make well-reasoned judgments and decisions.

Various critical thinking models exist, each catering to different contexts and scenarios. These models offer a step-by-step method to analyze situations, scrutinize assumptions and biases, and consider alternative perspectives. Ultimately, the goal of critical thinking models is to enhance an individual’s ability to think critically, ultimately improving their reasoning and decision-making skills in both personal and professional settings.

Key Takeaways

Fundamentals of critical thinking.

Definition and Importance

Critical thinking is the intellectual process of logically, objectively, and systematically evaluating information to form reasoned judgments, utilizing reasoning , logic , and evidence . It involves:

Core Cognitive Skills

These skills enable individuals to consistently apply intellectual standards in their thought process, which ultimately results in sound judgments and informed decisions.

Influence of Cognitive Biases

The critical thinking process.

Stages of Critical Thinking

The critical thinking process starts with gathering and evaluating data . This stage involves identifying relevant information and ensuring it is credible and reliable. Next, an individual engages in analysis by examining the data closely to understand its context and interpret its meaning. This step can involve breaking down complex ideas into simpler components for better understanding.

Application in Decision Making

In decision making, critical thinking is a vital skill that allows individuals to make informed choices. It enables them to:

Critical Thinking Models

The red model.

The RED Model stands for Recognize Assumptions, Evaluate Arguments, and Draw Conclusions. It emphasizes the importance of questioning assumptions, weighing evidence, and reaching logical conclusions.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Paul-elder model, the halpern critical thinking assessment.

The Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment is a standardized test developed by Diane Halpern to assess critical thinking skills. The evaluation uses a variety of tasks to measure abilities in core skill areas, such as verbal reasoning, argument analysis, and decision making. Pearson, a leading publisher of educational assessments, offers this test as a means to assess individuals’ critical thinking skills ^(source) .

Evaluating Information and Arguments

Evidence assessment.

When practicing critical thinking skills, it is essential to be aware of your own biases and make efforts to minimize their influence on your decision-making process.

Logic and Fallacies

Argument analysis, enhancing critical thinking, strategies for improvement, critical thinking in education, developing a critical thinking mindset.

To truly enhance critical thinking abilities, it’s important to adopt a mindset that values integrity , autonomy , and empathy . These qualities help to create a learning environment that encourages open-mindedness, which is key to critical thinking development. To foster a critical thinking mindset:

Critical Thinking in Various Contexts

The workplace and beyond.

Moreover, critical thinking transcends the workplace and applies to various aspects of life. It empowers an individual to make better decisions, analyze conflicting information, and engage in constructive debates.

Creative and Lateral Thinking

In conclusion, critical thinking is a multifaceted skill that comprises various thought processes, including creative and lateral thinking. By embracing these skills, individuals can excel in the workplace and in their personal lives, making better decisions and solving problems effectively.

Overcoming Challenges

Recognizing and addressing bias, dealing with information overload, measuring critical thinking, assessment tools and criteria, the role of iq and tests.

It’s important to note that intelligence quotient (IQ) tests and critical thinking assessments are not the same. While IQ tests aim to measure an individual’s cognitive abilities and general intelligence, critical thinking tests focus specifically on one’s ability to analyze, evaluate, and form well-founded opinions. Therefore, having a high IQ does not necessarily guarantee strong critical thinking skills, as critical thinking requires additional mental processes beyond basic logical reasoning.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main steps involved in the paul-elder critical thinking model, can you list five techniques to enhance critical thinking skills, what is the red model of critical thinking and how is it applied, how do the ‘3 c’s’ of critical thinking contribute to effective problem-solving.

The ‘3 C’s’ of critical thinking – Curiosity, Creativity, and Criticism – collectively contribute to effective problem-solving. Curiosity allows individuals to explore various perspectives and ask thought-provoking questions, while Creativity helps develop innovative solutions and unique approaches to challenges. Criticism, or the ability to evaluate and analyze ideas objectively, ensures that the problem-solving process remains grounded in logic and relevance.

What characteristics distinguish critical thinking from creative thinking?

What are some recommended books to help improve problem-solving and critical thinking skills, you may also like, how to overcome procrastination, best careers for problem solving: top opportunities for critical thinkers, parents teaching critical thinking: effective strategies for raising independent thinkers, the psychology behind critical thinking: understanding the mental processes involved, download this free ebook.

Mental Models: How to Train Your Brain to Think in New Ways

You can train your brain to think better. One of the best ways to do this is to expand the set of mental models you use to think. Let me explain what I mean by sharing a story about a world-class thinker.

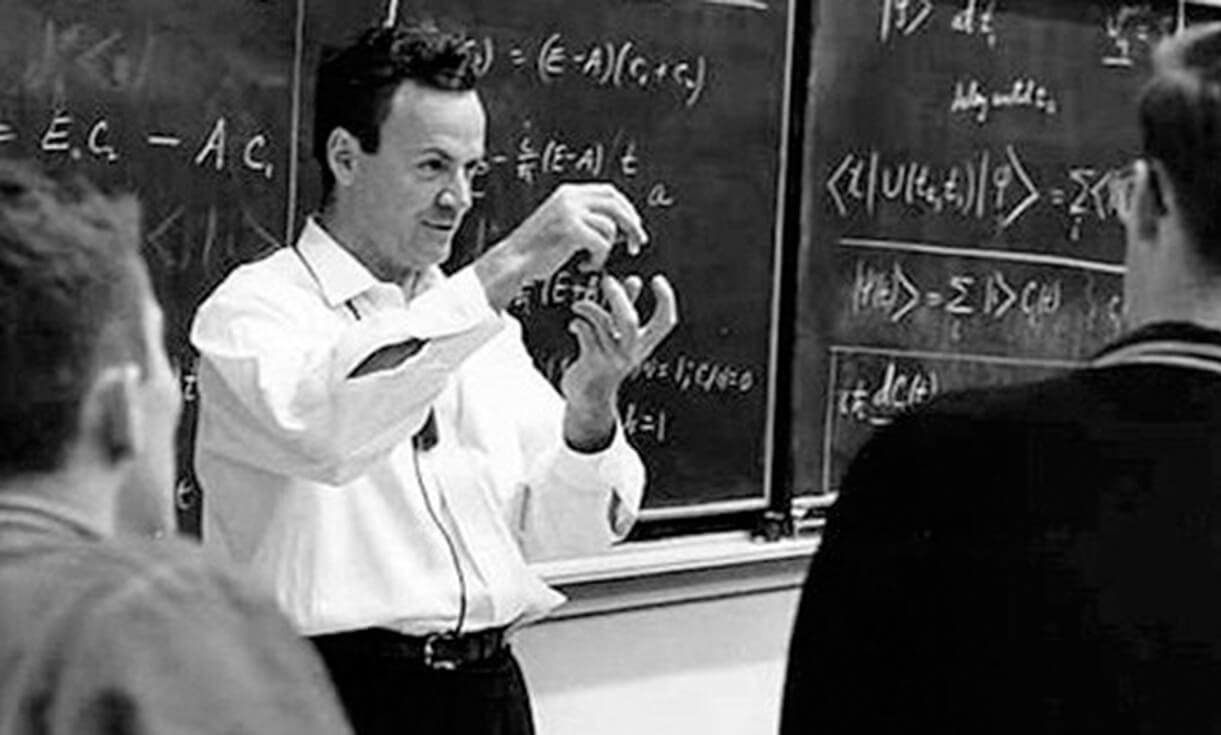

I first discovered what a mental model was and how useful the right one could be while I was reading a story about Richard Feynman, the famous physicist. Feynman received his undergraduate degree from MIT and his Ph.D. from Princeton. During that time, he developed a reputation for waltzing into the math department and solving problems that the brilliant Ph.D. students couldn’t solve.

When people asked how he did it, Feynman claimed that his secret weapon was not his intelligence, but rather a strategy he learned in high school. According to Feynman, his high school physics teacher asked him to stay after class one day and gave him a challenge.

“Feynman,” the teacher said, “you talk too much and you make too much noise. I know why. You’re bored. So I’m going to give you a book. You go up there in the back, in the corner, and study this book, and when you know everything that’s in this book, you can talk again.” 1

So each day, Feynman would hide in the back of the classroom and study the book—Advanced Calculus by Woods—while the rest of the class continued with their regular lessons. And it was while studying this old calculus textbook that Feynman began to develop his own set of mental models.

“That book showed how to differentiate parameters under the integral sign,” Feynman wrote. “It turns out that’s not taught very much in the universities; they don’t emphasize it. But I caught on how to use that method, and I used that one damn tool again and again. So because I was self-taught using that book, I had peculiar methods of doing integrals.”

“The result was, when the guys at MIT or Princeton had trouble doing a certain integral, it was because they couldn’t do it with the standard methods they had learned in school. If it was a contour integration, they would have found it; if it was a simple series expansion, they would have found it. Then I come along and try differentiating under the integral sign, and often it worked. So I got a great reputation for doing integrals, only because my box of tools was different from everybody else’s, and they had tried all their tools on it before giving the problem to me.” 2

Every Ph.D. student at Princeton and MIT is brilliant. What separated Feynman from his peers wasn’t necessarily raw intelligence. It was the way he saw the problem. He had a broader set of mental models.

What is a Mental Model?

A mental model is an explanation of how something works. It is a concept, framework, or worldview that you carry around in your mind to help you interpret the world and understand the relationship between things. Mental models are deeply held beliefs about how the world works.

For example, supply and demand is a mental model that helps you understand how the economy works. Game theory is a mental model that helps you understand how relationships and trust work. Entropy is a mental model that helps you understand how disorder and decay work.

Mental models guide your perception and behavior. They are the thinking tools that you use to understand life, make decisions, and solve problems. Learning a new mental model gives you a new way to see the world—like Richard Feynman learning a new math technique.

Mental models are imperfect, but useful. There is no single mental model from physics or engineering, for example, that provides a flawless explanation of the entire universe, but the best mental models from those disciplines have allowed us to build bridges and roads, develop new technologies, and even travel to outer space. As historian Yuval Noah Harari puts it, “Scientists generally agree that no theory is 100 percent correct. Thus, the real test of knowledge is not truth, but utility.”

The best mental models are the ideas with the most utility. They are broadly useful in daily life. Understanding these concepts will help you make wiser choices and take better actions. This is why developing a broad base of mental models is critical for anyone interested in thinking clearly, rationally, and effectively.

The Secret to Great Thinking and Decision Making

Expanding your set of mental models is something experts need to work on just as much as novices. We all have our favorite mental models, the ones we naturally default to as an explanation for how or why something happened. As you grow older and develop expertise in a certain area, you tend to favor the mental models that are most familiar to you.

Here’s the problem: when a certain worldview dominates your thinking, you’ll try to explain every problem you face through that worldview. This pitfall is particularly easy to slip into when you’re smart or talented in a given area.

The more you master a single mental model, the more likely it becomes that this mental model will be your downfall because you’ll start applying it indiscriminately to every problem. What looks like expertise is often a limitation. As the common proverb says, “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” 3

When a certain worldview dominates your thinking, you’ll try to explain every problem you face through that worldview.

Consider this example from biologist Robert Sapolsky. He asks, “Why did the chicken cross the road?” Then, he provides answers from different experts.

- If you ask an evolutionary biologist, they might say, “The chicken crossed the road because they saw a potential mate on the other side.”

- If you ask a kinesiologist, they might say, “The chicken crossed the road because the muscles in the leg contracted and pulled the leg bone forward during each step.”

- If you ask a neuroscientist, they might say, “The chicken crossed the road because the neurons in the chicken’s brain fired and triggered the movement.”

Technically speaking, none of these experts are wrong. But nobody is seeing the entire picture either. Each individual mental model is just one view of reality. The challenges and situations we face in life cannot be entirely explained by one field or industry.

All perspectives hold some truth. None of them contain the complete truth.

Relying on a narrow set of thinking tools is like wearing a mental straitjacket. Your cognitive range of motion is limited. When your set of mental models is limited, so is your potential for finding a solution. In order to unleash your full potential, you have to collect a range of mental models. You have to build out your decision making toolbox. Thus, the secret to great thinking is to learn and employ a variety of mental models.

Expanding Your Set of Mental Models

The process of accumulating mental models is somewhat like improving your vision. Each eye can see something on its own. But if you cover one of them, you lose part of the scene. It’s impossible to see the full picture when you’re only looking through one eye.

Similarly, mental models provide an internal picture of how the world works. We should continuously upgrade and improve the quality of this picture. This means reading widely from the best books , studying the fundamentals of seemingly unrelated fields, and learning from people with wildly different life experiences. 4

The mind’s eye needs a variety of mental models to piece together a complete picture of how the world works. The more sources you have to draw upon, the clearer your thinking becomes. As the philosopher Alain de Botton notes, “The chief enemy of good decisions is a lack of sufficient perspectives on a problem.”

The Pursuit of Liquid Knowledge

In school, we tend to separate knowledge into different silos—biology, economics, history, physics, philosophy. In the real world, information is rarely divided into neatly defined categories. In the words of Charlie Munger, “All the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.” 5

World-class thinkers are often silo-free thinkers. They avoid looking at life through the lens of one subject. Instead, they develop “liquid knowledge” that flows easily from one topic to the next.

This is why it is important to not only learn new mental models, but to consider how they connect with one another. Creativity and innovation often arise at the intersection of ideas. By spotting the links between various mental models, you can identify solutions that most people overlook.

Tools for Thinking Better

Here’s the good news:

You don’t need to master every detail of every subject to become a world-class thinker. Of all the mental models humankind has generated throughout history, there are just a few dozen that you need to learn to have a firm grasp of how the world works.

Many of the most important mental models are the big ideas from disciplines like biology, chemistry, physics, economics, mathematics, psychology, philosophy. Each field has a few mental models that form the backbone of the topic. For example, some of the pillar mental models from economics include ideas like Incentives, Scarcity, and Economies of Scale.

If you can master the fundamentals of each discipline, then you can develop a remarkably accurate and useful picture of life. To quote Charlie Munger again, “80 or 90 important models will carry about 90 percent of the freight in making you a worldly-wise person. And, of those, only a mere handful really carry very heavy freight.” 6

I’ve made it a personal mission to uncover the big models that carry the heavy freight in life. After researching more than 1,000 different mental models, I gradually narrowed it down to a few dozen that matter most. I’ve written about some of them previously, like entropy and inversion , and I’ll be covering more of them in the future. If you’re interested, you can browse my slowly expanding list of mental models .

My hope is to create a list of the most important mental models from a wide range of disciplines and explain them in a way that is not only easy to understand, but also meaningful and practical to the daily life of the average person. With any luck, we can all learn how to think just a little bit better.

Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman! by Richard Feynman. Pages 86-87.

This idea is sometimes called The Law of the Instrument or Man With a Hammer Syndrome. The original phrase comes from Abraham Kaplan’s book, The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science . On page 28 he writes, “Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.”

With regards to the importance of reading widely, a quote from the wonderful writer Haruki Murakami comes to mind, “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

“A Lesson on Elementary, Worldly Wisdom As It Relates To Investment Management & Business” by Charles Munger. Speech at USC Business School. 1994.

Thanks for reading. You can get more actionable ideas in my popular email newsletter. Each week, I share 3 short ideas from me, 2 quotes from others, and 1 question to think about. Over 3,000,000 people subscribe . Enter your email now and join us.

James Clear writes about habits, decision making, and continuous improvement. He is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller, Atomic Habits . The book has sold over 20 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 60 languages.

Click here to learn more →

- Entropy: Why Life Always Seems to Get More Complicated

- Inversion: The Crucial Thinking Skill Nobody Ever Taught You

- A Margin of Safety: How to Thrive in the Age of Uncertainty

- The 1 Percent Rule: Why a Few People Get Most of the Rewards

- The Paradox of Behavior Change

- All Articles

A podcast and blog exploring the meaningful path of kodawari.

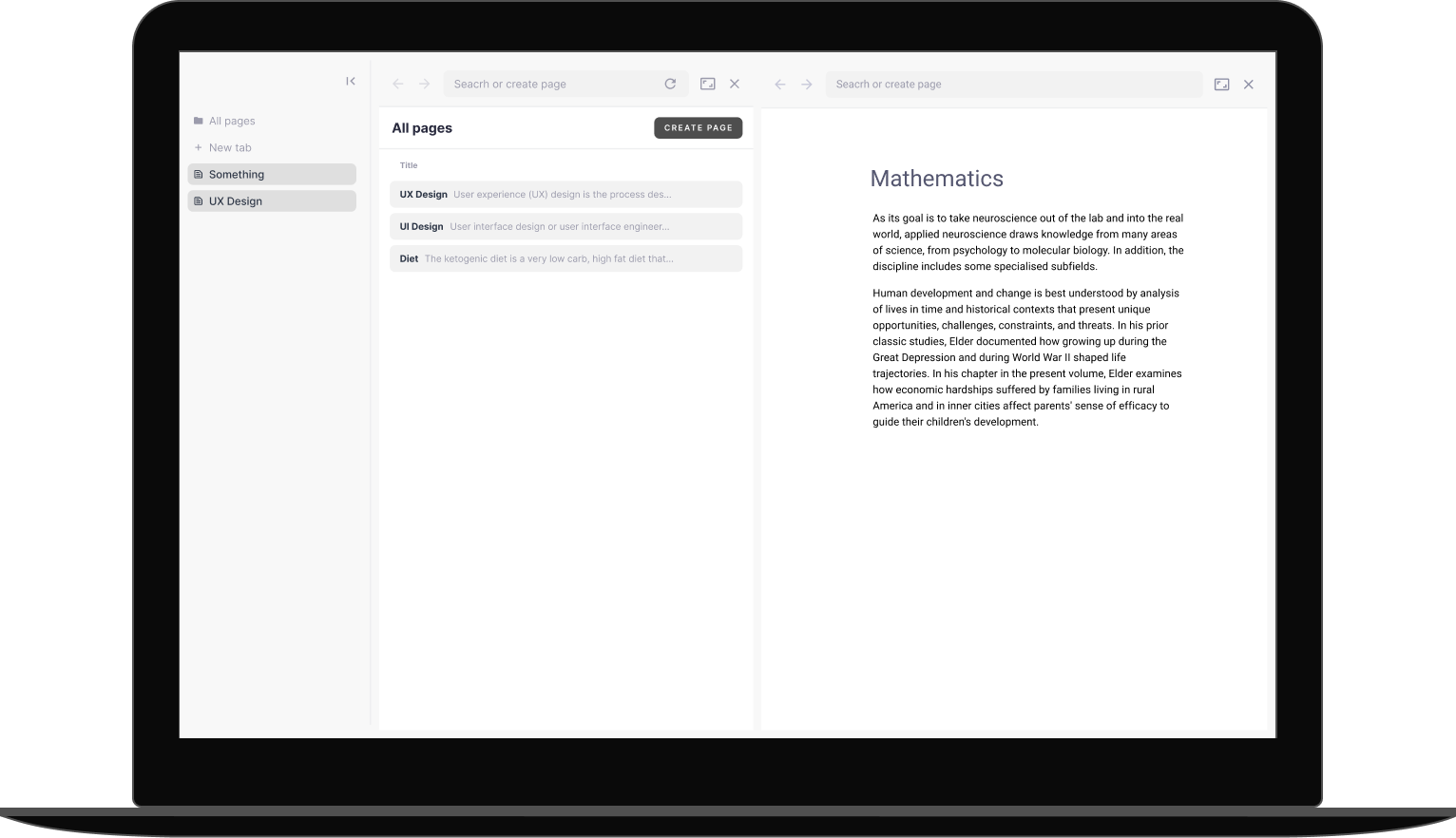

Mental Models And Critical Thinking

On May 13, 2021

In Mental Frameworks , Self-Improvement

More important than learning what to think is learning how to think ( critical thinking). So in this article, we will examine one approach that’s been useful to us—that critical thinking is learning how to use mental models. Mental models are the frameworks that we use to simplify and understand the world. And building a robust toolbox of these is a great way to think more clearly and make better decisions.

At his trial, Socrates apparently uttered the famous words that “the unexamined life is not worth living”. It means that we should strive to understand ourselves in order to have a deep and meaningful life. This includes examining and being critical of our thinking.

And one way to get better at critical thinking is to build up a database of mental models.

Mental models help us by reducing complexity in the world. We can’t pay attention to everything, and models help show us what is important—they block out the noise and boost the signal. At Exploring Kodawari, we refer to them as mental frameworks, and you can view our growing list of them here .

But in order to improve our critical thinking, we must first understand how mental models work. So this article is a kind of “meta” mental framework explaining what models are and why we need so many of them.

Mental Models And How They Help With Critical Thinking

Mental models are representations of how human beings think. They can be loose concepts with a wide utility or very narrow concepts for specific applications. But in all cases, they help us understand the world by highlighting certain information within it.

Mental models also highlight the connections we see in the world. For all intents and purposes, the world is infinitely complex, and mental models allow us to let go of most of that complexity so that we can pay attention to the relevant bits.

Without mental models, we would be completely overwhelmed—we wouldn’t have a hierarchy of what to pay attention to. With them, though, we have a better chance at figuring out what’s important and how to act.

While each model by itself is biased, critical thinking is having multiple models that compete against each other. This helps us to cancel out that bias by seeing reality from as many perspectives as possible.

One way of understanding mental models is to understand heuristics. A heuristic is a fancy term for what is commonly called a rule of thumb. These are rules or models of reality that are easily learned and broadly accurate. By definition, they are not completely accurate and they do not work all of the time.

So heuristics are approximations of reality that allow us to be more efficient with our thinking. They lower our cognitive demand by blocking out the complexity of each individual situation and focusing on the broadly true pattern.

For a heuristic to be good, it either has to be true most of the time or has to have a bias in the direction of safety. For example, the rule of thumb to treat every gun as if it’s loaded might be literally false most of the time, but still pragmatically true enough to prevent horrible gun accidents.

And mental models are like heuristics in that they don’t have to be completely right—they just need utility. As British statistician George Box once said, “All models are wrong, some are useful.”

As long as we are aware that heuristics can bias our thinking, they are safe to use. And when we have to make fast decisions, they are really our only choice.

Compressing Reality

When an image or sound file is digitally compressed, information is strategically removed in order to create a smaller file. Due to redundant information and limitations in human perception, compressed files can be many times smaller while retaining almost the same fidelity.

And a good mental model is similar—it simplifies reality by removing unnecessary information and focusing on what is useful. This overlaps with the psychological concept of cognitive schema . Schemas are how our brains interpret and categorize information in the world. For example, a chair and a beanbag have little in common objectively, yet our brains see them both through the same schema of “something to sit on”.

Like heuristics, schemas/frameworks/models are about utility. Our brains did not evolve to objectively understand the world—to find the ultimate truth. Instead, they evolved to build models that are true enough . Like digital compression, successful cognitive models simplify reality by maintaining sufficient complexity—that is, they are true/accurate enough to remain useful.

As soon as they are not useful, we either have to use a different model or update our model to accommodate new information.

Your Toolbox For Critical Thinking

We’ve already said that because of bias, critical thinking requires you to have multiple models (or categories of models) that see reality from different perspectives. For example, a biologist might rely too heavily on evolutionary models (incentives, hierarchies, niches, etc) while an engineer might rely too heavily on systems thinking (feedback loops, emergence, critical mass, etc).

So having a toolbox of multiple models, including those outside your specialization, helps you find the right tool for the right job. Or at least, because different models highlight different patterns, you’ll find a model that best fits your goals.

Plus, having more schemas/models also means that you can learn and retain information more quickly. This is why I prefer the term framework. Like Charlie Munger says, frameworks give you a place to hang information:

“Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models.” Charlie Munger, A Lesson on Elementary Worldly Wisdom

Just like your skeleton gives your body a structure, mental frameworks structure your knowledge in an organized way. And the more frameworks you have, the more organized and useful your knowledge will be.

Making Them Personal

Just because you read about a mental model, it doesn’t make it “yours”. To really own a model, you have to integrate it into your mind through personal experience. Otherwise, the model is just a shell—a name without enough depth. But this changes once you make it personal.

Personal models become deeply rooted in your mind. It evolves from a name to a complex network of connections and examples.

For example, I use the mental framework of the modular mind almost every day. This model says that, even though we feel like a unified mind, we are actually comprised of multiple “modules” competing for our conscious attention. It has a long and complicated scientific history, but the main takeaway is simpler: you have subpersonalities inside your head and many of them are shortsighted and selfish.

So with this model, critical thinking is realizing that certain thoughts are not even your thinking at all. Yes, they come from your brain, but the modular mind reminds us that evolution makes us think things that we don’t have to believe.

But just understanding the psychology of it is not enough. You have to also sit down and notice this mental framework in your own life. You have to subjectively feel how your modules try to control you. And this is true of all models—if you don’t make them personal their utility will be mostly limited.

Categories of Mental Models

As a person just looking to think more critically, make better decisions, and generally improve themselves, I’ve found that broader categories of models are often more useful than specific ones. You can use specific frameworks, but sometimes the larger category gives you enough perspective.

So here are some broad categories of mental models and a short description of how that framework can be useful.

Evolutionary Framework

It’s easy for human beings to feel like they are somehow separate from nature. But the evolutionary framework reminds us that we are a product of nature—gradual change due to evolution by natural selection. And this applies not just to our bodies but also to parts of our psychology.

Psychological traits that occur universally across cultures are good candidates for being adaptations. Certain cultural practices work this way too—you can think of culture as “idea software” that evolved to run on the hardware of the brain. When we learn to view ourselves through the evolutionary lens, a lot of our behavior and motivation make way more sense.

This doesn’t mean that evolved behavior is good just because it’s natural (the naturalistic fallacy). Instead, it’s a way to understand ourselves so that we can be more consistently moral.

Hedonic adaptation , the modular mind , and consciousness are all mental models that fit into this category.

Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are the classic thinking traps that our brains can fall into. We are especially susceptible to these in arguments and debates. While fallacious arguments might appear legit and persuasive on the surface, they contain logical errors that invalidate whatever is being argued.

A logical fallacy may be committed on purpose (deceptive) or on accident (just sloppy thinking). But the point is that either way, an argument based on a logical fallacy is false—although a claim can still be true even if its reasoning is false.

So logical fallacies are great mental models to learn about and notice in your thinking. They highlight the common patterns of how we tend to be sloppy with our thinking, and being familiar with them will improve your critical thinking skills.

Some popular examples of logical fallacies are ad hominem, the slippery slope, and the straw man. Aim to learn them and notice them in yourself and others. This will definitely improve your critical thinking skills.

This category refers to general laws or concepts from physics that we can personify in our human lives. One example is inertia. Inertia states that an object will resist changes in velocity and direction unless acted on by an outside force. And this principle of motion also applies to individuals and organizations.

Relativity is another powerful physics concept that we can export into our thinking. You don’t have to understand Einstein to realize that our frame of reference biases us. For example, if we’re in a plane at cruising altitude, we don’t realize that we’re going nearly 600 mph. But an outside observer would notice this immediately. And this effect occurs in our social lives as well. Critical thinking requires that we be aware of how relativity biases us.

Engineering Frameworks

Engineering frameworks are similar to physics (because engineers rely on physics to build things). But they tend to involve concepts that reveal themselves in more complex systems.

For example, emergence says that sometimes lower-level parts create unexpected higher-level phenomena. And often we can’t even reduce that higher-level emergence to truths from the lower-level domain.

Another engineering principle is feedback loops (A causes B which loops back to A). A classic example of this is when you place a microphone next to its speaker, quickly resulting in a high pitch screech (positive feedback). Positive feedback loops run out of control whereas negative loops (like a thermostat) maintain equilibrium.

These types of frameworks apply not just to engineering systems but also to ourselves and the organizations we create.

Conclusion: Critical Thinking Is Critical

Critical thinking is not just knowing what to think but knowing how to think. It is understanding more consciously how the human mind learns and makes sense of the world. And because mental models are how we do this, learning them more consciously will allow you to think more clearly and make better decisions.

So if you want to get better at critical thinking, consider adding more and more mental models to your toolbox. Study them and make them personal. Over time, they will help you to live a more balanced and consistent life.

Mental Model Resources

- Farnam Street’s List of Mental Models

- James Clear’s List of Mental Models

- Farnam Street’s Shane Parrish on the Making Sense Podcast

- Exploring Kodawari’s Growing List of Mental Models

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

The Mindful Pause

Stoicism as a philosophy of life.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén

- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

Farnam Street

Mastering the best of what other people have already figured out

Mental Models: The Best Way to Make Intelligent Decisions (~100 Models Explained)

What are mental models.

A mental model is a compression of how something works. Any idea, belief, or concept can be distilled down. Like a map, mental models reveal key information while ignoring irrelevant details. Models concentrate the world into understandable and useable chunks.

Mental models help us understand the world. For example, velocity is a mental model that helps you understand that both speed and direction matter. Reciprocity is a mental model that helps you understand how going positive and going first gets the world to do most of the work for you. Margin of Safety is a mental model that helps you understand that things don’t always go as planned. Relativity is a mental model that shows us we have blind spots and how a different perspective can reveal new information. The list goes on.

Coming October 2024: Pre-order all 4 volumes of The Great Mental Models now.

Eliminating Blind Spots

In life and business, the person with the fewest blind spots wins.

The source of all poor choices is blind spots. Think about it. If you had perfect information, you would always make the best decision. You’d play your hand perfectly in a poker game where you could see everyone’s cards. You wouldn’t make any mistakes.

How do we eliminate blind spots?

The best way to reduce our blind spots is to change our perspective. Just as knowing where to stand can turn a good photo into a great one, changing your perspective on a situation reveals critical information and offers new solutions.

Think of each model as a lens through which you can see the world. Each lens offers a different perspective, revealing new information. Looking through one lens lets you see one thing, and looking through another reveals something different. Looking through them both reveals more than each one individually.

While there are a lot of specific mental models, only a handful of general ones come from the big disciplines. Understanding them positions you to make fewer errors, see things others miss, and take better actions.

Let’s take a look at the best general models.

You’ve got to have models in your head and you’ve got to array you experience – both vicarious and direct – onto this latticework of mental models. Charlie munger

A Latticework of Mental Models

Worldly wisdom is not simply memorizing things and repeating them back. The people that do that fail at work and fail in life. Wisdom is knowing the consequences of your actions, which comes from the alignment between facts and reasoning.

The world is not divided into distinct disciplines. For example, business professors won’t discuss physics in their lectures, but they should. Velocity teaches us that speed and direction matter. Kinetic energy teaches us that velocity matters more than mass when creating a force. Understanding these insights helps you outperform.

In the real world, everything is connected like a latticework. Just because our teachers didn’t show us how to use the big ideas from all the disciplines in life and business doesn’t mean we can’t learn them ourselves. That’s why we created The Great Mental Models project.

Here are the big ideas that can help you make better decisions, avoid problems, and spot opportunities others miss.

- Core Thinking Concepts

- Physics and Chemistry

- Microeconomics

- Military and War

- Human Nature and Judgment

The Core Mental Models

1. The Map is Not the Territory The map of reality is not reality. Even the best maps are imperfect. That’s because they are reductions of what they represent. If a map were to represent the territory with perfect fidelity, it would no longer be a reduction and thus would no longer be useful to us. A map can also be a snapshot of a point in time, representing something that no longer exists. This is important to keep in mind as we think through problems and make better decisions.

2. Circle of Competence When ego and not competence drive what we undertake, we have massive blind spots. If you know what you understand, you know where you have an edge over others. When you are honest about where your knowledge is lacking, you know where you are vulnerable and where you can improve. Understanding your circle of competence improves decision-making and outcomes.

3. First Principles Thinking First-principles thinking is one of the best ways to reverse-engineer complicated situations and unleash creative possibility. Sometimes called reasoning from first principles, it’s a tool to help clarify complicated problems by separating the underlying ideas or facts from any assumptions based on them. What remains are the essentials. If you know the first principles of something, you can build the rest of your knowledge around them to produce something new.

4. Thought Experiment Thought experiments can be defined as “devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things.” Many disciplines, such as philosophy and physics, make use of thought experiments to examine what can be known. In doing so, they can open up new avenues for inquiry and exploration. Thought experiments are powerful because they help us learn from our mistakes and avoid future ones. They let us take on the impossible, evaluate the potential consequences of our actions, and re-examine history to make better decisions. They can help us both figure out what we really want and the best way to get there.

5. Second-Order Thinking Almost everyone can anticipate the immediate results of their actions. This type of first-order thinking is easy and safe, but it’s also a way to ensure you get the same results that everyone else gets. Second-order thinking is thinking farther ahead and thinking holistically. It requires us to consider not only our actions and their immediate consequences but the subsequent effects of those actions as well. Failing to consider the second and third-order effects can unleash disaster.

6. Probabilistic Thinking Probabilistic thinking is essentially trying to estimate, using some tools of math and logic, the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass. It is one of the best tools we have to improve the accuracy of our decisions. In a world where each moment is determined by an infinitely complex set of factors, probabilistic thinking helps us identify the most likely outcomes. When we know these, our decisions can be more precise and effective.

7. Inversion Inversion is a powerful tool to improve your thinking because it helps you identify and remove obstacles to success. The root of inversion is “invert,” which means to upend or turn upside down. As a thinking tool, it means approaching a situation from the opposite end of the natural starting point. Most of us tend to think one way about a problem: forward. Inversion allows us to flip the problem around and think backward. Sometimes it’s good to start at the beginning, but it can be more useful to start at the end.

8. Occam’s Razor Simpler explanations are more likely to be true than complicated ones. This is the essence of Occam’s Razor, a classic principle of logic and problem-solving. Instead of wasting your time trying to disprove complex scenarios, you can make decisions more confidently by basing them on the explanation that has the fewest moving parts.

9. Hanlon’s Razor Hard to trace in its origin, Hanlon’s Razor states that we should not attribute to malice that which is more easily explained by stupidity. In a complex world, using this model helps us avoid paranoia and ideology. By not generally assuming that bad results are the fault of a bad actor, we look for options instead of missing opportunities. This model reminds us that people do make mistakes. It demands that we ask if there is another reasonable explanation for the events that have occurred. The explanation most likely to be right is the one that contains the least amount of intent.

The Mental Models of Physics and Chemistry

1. Relativity Relativity has been used in several contexts in the world of physics, but the important aspect to study is the idea that an observer cannot truly understand a system of which he himself is a part. For example, a man inside an airplane does not feel like he is experiencing movement, but an outside observer can see that movement is occurring. This form of relativity tends to affect social systems in a similar way.

2. Reciprocity If I push on a wall, physics tells me that the wall pushes back with equivalent force. In a biological system, if one individual acts on another, the action will tend to be reciprocated in kind. And of course, human beings act with intense reciprocity demonstrated as well.

3. Thermodynamics The laws of thermodynamics describe energy in a closed system. The laws cannot be escaped and underlie the physical world. They describe a world in which useful energy is constantly being lost, and energy cannot be created or destroyed. Applying their lessons to the social world can be a profitable enterprise.

4. Inertia An object in motion with a certain vector wants to continue moving in that direction unless acted upon. This is a fundamental physical principle of motion; however, individuals, systems, and organizations display the same effect. It allows them to minimize the use of energy, but can cause them to be destroyed or eroded.

5. Friction and Viscosity Both friction and viscosity describe the difficulty of movement. Friction is a force that opposes the movement of objects that are in contact with each other, and viscosity measures how hard it is for one fluid to slide over another. Higher viscosity leads to higher resistance. These concepts teach us a lot about how our environment can impede our movement.

6. Velocity Velocity is not equivalent to speed; the two are sometimes confused. Velocity is speed plus vector: how fast something gets somewhere. An object that moves two steps forward and then two steps back has moved at a certain speed but shows no velocity. The addition of the vector, that critical distinction, is what we should consider in practical life.

7. Leverage Most of the engineering marvels of the world were accomplished with applied leverage. As famously stated by Archimedes, “Give me a lever long enough and I shall move the world.” With a small amount of input force, we can make a great output force through leverage. Understanding where we can apply this model to the human world can be a source of great success.

8. Activation Energy A fire is not much more than a combination of carbon and oxygen, but the forests and coal mines of the world are not combusting at will because such a chemical reaction requires the input of a critical level of “activation energy” in order to get a reaction started. Two combustible elements alone are not enough.

9. Catalysts A catalyst either kick-starts or maintains a chemical reaction but isn’t itself a reactant. The reaction may slow or stop without the addition of catalysts. Social systems, of course, take on many similar traits, and we can view catalysts in a similar light.

10. Alloying When we combine various elements, we create new substances. This is no great surprise, but what can be surprising in the alloying process is that 2+2 can equal not 4 but 6 – the alloy can be far stronger than the simple addition of the underlying elements would lead us to believe. This process leads us to engineer great physical objects, but we understand many intangibles in the same way; a combination of the right elements in social systems or even individuals can create a 2+2=6 effect similar to alloying.

The Mental Models of Biology

1. Evolution Part One: Natural Selection and Extinction Evolution by natural selection was once called “the greatest idea anyone ever had.” In the 19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace simultaneously realized that species evolve through random mutation and differential survival rates. If we call human intervention in animal breeding an example of “artificial selection,” we can call Mother Nature deciding the success or failure of a particular mutation “natural selection.” Those best suited for survival tend to be preserved. But of course, conditions change.

2. Evolution Part Two: Adaptation and The Red Queen Effect Species tend to adapt to their surroundings in order to survive, given the combination of their genetics and their environment – an always-unavoidable combination. However, adaptations made in an individual’s lifetime are not passed down genetically, as was once thought: Populations of species adapt through the process of evolution by natural selection, as the most-fit examples of the species replicate at an above-average rate.

The evolution-by-natural-selection model leads to something of an arms race among species competing for limited resources. When one species evolves an advantageous adaptation, a competing species must respond in kind or fail as a species. Standing still can mean falling behind. This arms race is called the Red Queen Effect for the character in Alice in Wonderland who said, “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

3. Ecosystems An ecosystem describes any group of organisms coexisting with the natural world. Most ecosystems show diverse forms of life taking on different approaches to survival, with such pressures leading to varying behavior. Social systems can be seen in the same light as the physical ecosystems and many of the same conclusions can be made.

4. Niches Most organisms find a niche: a method of competing and behaving for survival. Usually, a species will select a niche for which it is best adapted. The danger arises when multiple species begin competing for the same niche, which can cause an extinction – there can be only so many species doing the same thing before limited resources give out.

5. Self-Preservation Without a strong self-preservation instinct in an organism’s DNA, it would tend to disappear over time, thus eliminating that DNA. While cooperation is another important model, the self-preservation instinct is strong in all organisms and can cause violent, erratic, and/or destructive behavior for those around them.

6. Replication A fundamental building block of diverse biological life is high-fidelity replication. The fundamental unit of replication seems to be the DNA molecule, which provides a blueprint for the offspring to be built from physical building blocks. There are a variety of replication methods, but most can be lumped into sexual and asexual.

7. Cooperation Competition tends to describe most biological systems, but cooperation at various levels is just as important a dynamic. In fact, the cooperation of a bacterium and a simple cell probably created the first complex cell and all of the life we see around us. Without cooperation, no group survives, and the cooperation of groups gives rise to even more complex versions of organization. Cooperation and competition tend to coexist at multiple levels.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a famous application of game theory in which two prisoners are both better off cooperating with each other, but if one of them cheats, the other is better off cheating. Thus the dilemma. This model shows up in economic life, in war, and in many other areas of practical human life. Though the prisoner’s dilemma theoretically leads to a poor result, in the real world, cooperation is nearly always possible and must be explored.

8. Hierarchical Organization Most complex biological organisms have an innate feel for how they should organize. While not all of them end up in hierarchical structures, many do, especially in the animal kingdom. Human beings like to think they are outside of this, but they feel the hierarchical instinct as strongly as any other organism. This includes the Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram Experiments, which demonstrated what humans learned practically many years before: the human bias towards being influenced by authority. In a dominance hierarchy such as ours, we tend to look to the leader for guidance on behavior, especially in situations of stress or uncertainty. Thus, authority figures have a responsibility to act well, whether they like it or not.

9. Incent ives All creatures respond to incentives to keep themselves alive. This is the basic insight of biology. Constant incentives will tend to cause a biological entity to have constant behavior to an extent. Humans are included and are particularly great examples of the incentive-driven nature of biology; however, humans are complicated in that their incentives can be hidden or intangible. The rule of life is to repeat what works and has been rewarded.

10. Tendency to Minimize Energy Output (Mental and physical) In a physical world governed by thermodynamics and competition for limited energy and resources, any biological organism that was wasteful with energy would be at a severe disadvantage for survival. Thus, we see in most instances that behavior is governed by a tendency to minimize energy usage when at all possible.

The Mental Models of Systems Thinking

1. Feedback L oops All complex systems are subject to positive and negative feedback loops whereby A causes B, which in turn influences A (and C), and so on – with higher-order effects frequently resulting from the continual movement of the loop. In a homeostatic system, a change in A is often brought back into line by an opposite change in B to maintain the balance of the system, as with the temperature of the human body or the behavior of an organizational culture. Automatic feedback loops maintain a “static” environment unless and until an outside force changes the loop. A “runaway feedback loop” describes a situation in which the output of a reaction becomes its own catalyst (auto-catalysis).

2. Equilibrium Homeostasis is the process through which systems self-regulate to maintain an equilibrium state that enables them to function in a changing environment. Most of the time, they over or undershoot it by a little and must keep adjusting. Like a pilot flying a plane, the system is off course more often than on course. Everything within a homeostatic system contributes to keeping it within a range of equilibrium, so it is important to understand the limits of the range.

3. Bottlenecks A bottleneck describes the place at which a flow (of a tangible or intangible) is stopped, thus constraining it from continuous movement. As with a clogged artery or a blocked drain, a bottleneck in the production of any good or service can be small but have a disproportionate impact if it is in the critical path. However, bottlenecks can also be a source of inspiration as they force us to reconsider if there are alternate pathways to success.

4. Scale One of the most important principles of systems is that they are sensitive to scale. Properties (or behaviors) tend to change when you scale them up or down. In studying complex systems, we must always be roughly quantifying – in orders of magnitude, at least – the scale at which we are observing, analyzing, or predicting the system.

5. Margin of Safety Similarly, engineers have also developed the habit of adding a margin for error into all calculations. In an unknown world, driving a 9,500-pound bus over a bridge built to hold precisely 9,600 pounds is rarely seen as intelligent. Thus, on the whole, few modern bridges ever fail. In practical life outside of physical engineering, we can often profitably give ourselves margins as robust as the bridge system.

6. Churn Churn is the silent killer of businesses. It’s the slow leak, the constant drip of customers slipping away, of users drifting off to find something new. It’s the attrition that eats away at your growth, that forces you to keep running just to stay in place. The thing about churn is that it’s often hidden. It’s not like a sudden crisis that grabs your attention. It’s a slow, quiet process that happens in the background.

Churn can present opportunity. Like a snake shedding its skin, replacing components of a system is a natural part to keeping it healthy. New parts can improve functionality.

When we use this model as a lens, we see that new people bring new ideas, and counterintuitively, some turnover allows us to maintain stability. Replacing what is worn out also allows us to upgrade and expand our capabilities, creating new opportunities.

Some churn is inevitable. Too much can kill you.

7. Algorithms Algorithms are recipes. A list of crisp, unambiguous steps that tell you how to get from point A to point B. But they’re more than just directions. Algorithms are if‑then machines for tuning out the noise and zeroing in on the signal. Have the specs been met? Follow the algorithm and find out. Thinking algorithmically means searching for processes that reliably spit out the results you want, like a vending machine dispensing the same candy bar every time someone punches in E4.

8. Critical mass Critical mass isn’t just a science term; it’s a guide for understanding that often things happen slowly and then all at once. It’s the moment when a system goes from sputtering along to explosive growth. Like a nuclear chain reaction, once you hit critical mass, the reaction becomes self-sustaining.

Through this lens we gain insight into the amount of material needed for a system to change from one state to another. Material can be anything from people and effort to raw material. When enough material builds up, systems reach their tipping point. When we keep going, we get sustainable change.

Using critical mass as a lens for situations in which you want different outcomes helps you identify both the design elements you need to change and the work you need to put in.

9. Emergence Nearly everything is an emergent effect— table, a space shuttle, even us— combinations of ingredients that come together in a specific way to create something new. Emergence is the universe’s way of reminding us that when we combine different pieces in new ways, we get results that are more than the sum of their parts, often in the most unexpected and thrilling ways.

Using this mental model is not about trying to predict emergent properties but rather acknowledging they are possible. There is no need to stick with what you know; mix it up and see what happens. Learn new skills, interact with new people, read new things.

10. Irreducibility Irreducibility is about essence. It’s the idea that some things can’t be broken down into smaller parts without losing what makes them tick. It’s the idea that not everything can be explained by looking at its components. Emergent properties arise from complex systems that can’t be predicted by studying the individual parts.

Grappling with irreducibility requires a shift in thinking. Instead of trying to break things down, sometimes you have to zoom out. Look at the big picture. Embrace the complexity. Because some problems don’t have neat, modular solutions. They’re irreducibly messy.

Using irreducibility as a lens helps you focus on what you can change by understanding what really matters.

11. Law of Diminishing Returns Diminishing returns is the idea that the easy wins usually come first. The more you optimize a system, the harder it gets to eke out additional improvements. Like squeezing juice from a lemon. The first squeeze is easy. The second takes a bit more work. By the tenth squeeze, you’re fighting for every last drop.

When you’re a beginner, every bit of effort translates into significant gains. But as you level up, progress becomes more incremental. It takes more and more work to get better and better. That’s why going from good to great is often harder than going from bad to good.

Understanding diminishing returns is crucial for allocating resources efficiently. You want to focus on the areas where you can get the biggest bang for your buck. Sometimes, that means knowing when to stop optimizing and move on to something else.

The Mental Models of Numeracy

1. Distributions The normal distribution is a statistical process that leads to the well-known graphical representation of a bell curve, with a meaningful central “average” and increasingly rare standard deviations from that average when correctly sampled. (The so-called “central limit” theorem.) Well-known examples include human height and weight, but it’s just as important to note that many common processes, especially in non-tangible systems like social systems, do not follow this pattern. Normal distributions can be contrasted with power law, or exponential, distributions.

2. Compounding Compounding is the magic of exponential growth. It’s the idea that small, consistent gains can snowball into massive results over time. Like a tiny snowball rolling down a hill, picking up more and more snow until it’s an avalanche.

Compounding requires us to think long- term about our knowledge, experiences, and relationships. It tells us that the small stuff we learn, the people we meet, and the connections we deepen, when reinvested into our lives, build up our fortunes in wisdom and relationships, not by chance, but by the steady, patient accumulation of efforts. The majority of success doesn’t happen by accident, and the lens of compounding illuminates the investments we need to make to get there.

Compounding is how you turn ordinary into extraordinary, one tiny gain at a time.

3. Sampling When we want to get information about a population (meaning a set of alike people, things, or events), we usually need to look at a sample (meaning a part of the population). It is usually not possible or even desirable to consider the entire population, so we aim for a sample that represents the whole. As a rule of thumb, more measurements mean more accurate results, all else being equal. Small sample sizes can produce skewed results.

4. Randomness Though the human brain has trouble comprehending it, much of the world is composed of random, non-sequential, non-ordered events. We are “fooled” by random effects when we attribute causality to things that are actually outside of our control. If we don’t course-correct for this fooled-by-randomness effect – our faulty sense of pattern-seeking – we will tend to see things as being more predictable than they are and act accordingly.

5. Regression to the Mean In a normally distributed system, long deviations from the average will tend to return to that average with an increasing number of observations: the so-called Law of Large Numbers. We are often fooled by regression to the mean, as with a sick patient improving spontaneously around the same time they begin taking an herbal remedy, or a poorly performing sports team going on a winning streak. We must be careful not to confuse statistically likely events with causal ones.

6. Multiplying by Zero Any reasonably educated person knows that any number multiplied by zero, no matter how large the number, is still zero. This is true in human systems as well as mathematical ones. In some systems, a failure in one area can negate great effort in all other areas. As simple multiplication would show, fixing the “zero” often has a much greater effect than does trying to enlarge the other areas.

7. Equivalence The introduction of algebra allowed us to demonstrate mathematically and abstractly that two seemingly different things could be the same. By manipulating symbols, we can demonstrate equivalence or inequivalence, the use of which led humanity to untold engineering and technical abilities. Knowing at least the basics of algebra can allow us to understand a variety of important results.

8. Surface Area The surface area of a three dimensional object is the amount of space on the outside of it. Thus, the more surface area you have, the more contact you have with your environment. Sometimes a high surface area is desirable: Our lungs and intestines have a huge surface area to increase the absorption of oxygen and nutrients. Other times we want to reduce our exposure, such as limiting our internet exposure to reduce the attack surface.

9. Global and Local Maxima The maxima and minima of a mathematical function are the largest and smallest values over its domain. Although there is one maximum value, the global maximum, there can be smaller peaks of value in a given range, the local maxima. Global and local maxima help us identify peaks, and if there is still potential to go higher or lower. It also reminds us that sometimes we have to go down to go back up.

The Mental Models of Microeconomics

1. Opportunity Costs Doing one thing means not being able to do another. We live in a world of trade-offs, and the concept of opportunity cost rules all. Most aptly summarized as “there is no such thing as a free lunch.”

2. Creative Destruction Coined by economist Joseph Schumpeter, the term “creative destruction” describes the capitalistic process at work in a functioning free-market system. Motivated by personal incentives (including but not limited to financial profit), entrepreneurs will push to best one another in a never-ending game of creative one-upmanship, in the process destroying old ideas and replacing them with newer technology. Beware getting left behind.

3. Comparative Advantage The Scottish economist David Ricardo had an unusual and non-intuitive insight: Two individuals, firms, or countries could benefit from trading with one another even if one of them was better at everything. Comparative advantage is best seen as an applied opportunity cost: If it has the opportunity to trade, an entity gives up free gains in productivity by not focusing on what it does best.

4. Specialization (Pin Factory) Another Scottish economist, Adam Smith, highlighted the advantages gained in a free-market system by specialization. Rather than having a group of workers each producing an entire item from start to finish, Smith explained that it’s usually far more productive to have each of them specialize in one aspect of production. He also cautioned, however, that each worker might not enjoy such a life; this is a trade-off of the specialization model.

5. Seizing the Middle In chess, the winning strategy is usually to seize control of the middle of the board, so as to maximize the potential moves that can be made and control the movement of the maximal number of pieces. The same strategy works profitably in business, as can be demonstrated by John D. Rockefeller’s control of the refinery business in the early days of the oil trade and Microsoft’s control of the operating system in the early days of the software trade.

6. Trademarks, Patents, and Copyrights These three concepts, along with other related ones, protect the creative work produced by enterprising individuals, thus creating additional incentives for creativity and promoting the creative-destruction model of capitalism. Without these protections, information and creative workers have no defense against their work being freely distributed.

7. Double-Entry Bookkeeping One of the marvels of modern capitalism has been the bookkeeping system introduced in Genoa in the 14th century. The double-entry system requires that every entry, such as income, also be entered into another corresponding account. Correct double-entry bookkeeping acts as a check on potential accounting errors and allows for accurate records and thus, more accurate behavior by the owner of a firm.

8. Utility (Marginal, Diminishing, Increasing) The usefulness of additional units of any good tends to vary with scale. Marginal utility allows us to understand the value of one additional unit, and in most practical areas of life, that utility diminishes at some point. On the other hand, in some cases, additional units are subject to a “critical point” where the utility function jumps discretely up or down. As an example, giving water to a thirsty man has diminishing marginal utility with each additional unit, and can eventually kill him with enough units.

9. Bribery Often ignored in mainstream economics, the concept of bribery is central to human systems: Given the chance, it is often easier to pay a certain agent to look the other way than to follow the rules. The enforcer of the rules is then neutralized. This principal/agent problem can be seen as a form of arbitrage.

10. Arbitrage Given two markets selling an identical good, an arbitrage exists if the good can profitably be bought in one market and sold at a profit in the other. This model is simple on its face, but can present itself in disguised forms: The only gas station in a 50-mile radius is also an arbitrage as it can buy gasoline and sell it at the desired profit (temporarily) without interference. Nearly all arbitrage situations eventually disappear as they are discovered and exploited.

11. Supply and Demand The basic equation of biological and economic life is one of limited supply of necessary goods and competition for those goods. Just as biological entities compete for limited usable energy, so too do economic entities compete for limited customer wealth and limited demand for their products. The point at which supply and demand for a given good are equal is called an equilibrium; however, in practical life, equilibrium points tend to be dynamic and changing, never static.

12. Scarcity Game theory describes situations of conflict, limited resources, and competition. Given a certain situation and a limited amount of resources and time, what decisions are competitors likely to make, and which should they make? One important note is that traditional game theory may describe humans as more rational than they really are. Game theory is theory, after all.

13. Mr. Market Mr. Market was introduced by the investor Benjamin Graham in his seminal book The Intelligent Investor to represent the vicissitudes of the financial markets. As Graham explains, the markets are a bit like a moody neighbor, sometimes waking up happy and sometimes waking up sad – your job as an investor is to take advantage of him in his bad moods and sell to him in his good moods. This attitude is contrasted to an efficient-market hypothesis in which Mr. Market always wakes up in the middle of the bed, never feeling overly strong in either direction.

The Mental Models of Military and War

1. Seeing the Front One of the most valuable military tactics is the habit of “personally seeing the front” before making decisions – not always relying on advisors, maps, and reports, all of which can be either faulty or biased. The Map/Territory model illustrates the problem with not seeing the front, as does the incentive model. Leaders of any organization can generally benefit from seeing the front, as not only does it provide firsthand information, but it also tends to improve the quality of secondhand information.

2. Asymmetric Warfare The asymmetry model leads to an application in warfare whereby one side seemingly “plays by different rules” than the other side due to circumstance. Generally, this model is applied by an insurgency with limited resources. Unable to out-muscle their opponents, asymmetric fighters use other tactics, as with terrorism creating fear that’s disproportionate to their actual destructive ability.

3. Two-Front War The Second World War was a good example of a two-front war. Once Russia and Germany became enemies, Germany was forced to split its troops and send them to separate fronts, weakening their impact on either front. In practical life, opening a two-front war can often be a useful tactic, as can solving a two-front war or avoiding one, as in the example of an organization tamping down internal discord to focus on its competitors.

4. Counterinsurgency Though asymmetric insurgent warfare can be extremely effective, over time competitors have also developed counterinsurgency strategies. Recently and famously, General David Petraeus of the United States led the development of counterinsurgency plans that involved no additional force but substantial additional gains. Tit-for-tat warfare or competition will often lead to a feedback loop that demands insurgency and counterinsurgency.

5. Mutually Assured Destruction Somewhat paradoxically, the stronger two opponents become, the less likely they may be to destroy one another. This process of mutually assured destruction occurs not just in warfare, as with the development of global nuclear warheads, but also in business, as with the avoidance of destructive price wars between competitors. However, in a fat-tailed world, it is also possible that mutually assured destruction scenarios simply make destruction more severe in the event of a mistake (pushing destruction into the “tails” of the distribution).

The Mental Models of Human Nature and Judgment

1. Trust Fundamentally, the modern world operates on trust. Familial trust is generally a given (otherwise we’d have a hell of a time surviving), but we also choose to trust chefs, clerks, drivers, factory workers, executives, and many others. A trusting system is one that tends to work most efficiently; the rewards of trust are extremely high.

2. Bias from Incentives Highly responsive to incentives, humans have perhaps the most varied and hardest to understand set of incentives in the animal kingdom. This causes us to distort our thinking when it is in our own interest to do so. A wonderful example is a salesman truly believing that his product will improve the lives of its users. It’s not merely convenient that he sells the product; the fact of his selling the product causes a very real bias in his own thinking.

3. Pavlovian Association Ivan Pavlov very effectively demonstrated that animals can respond not just to direct incentives but also to associated objects; remember the famous dogs salivating at the ring of a bell. Human beings are much the same and can feel positive and negative emotion towards intangible objects, with the emotion coming from past associations rather than direct effects.

4. Tendency to Feel Envy & Jealousy Humans have a tendency to feel envious of those receiving more than they are, and a desire “get what is theirs” in due course. The tendency towards envy is strong enough to drive otherwise irrational behavior, but is as old as humanity itself. Any system ignorant of envy effects will tend to self-immolate over time.

5. Tendency to Distort Due to Liking/Loving or Disliking/Hating Based on past association, stereotyping, ideology, genetic influence, or direct experience, humans have a tendency to distort their thinking in favor of people or things that they like and against people or things they dislike. This tendency leads to overrating the things we like and underrating or broadly categorizing things we dislike, often missing crucial nuances in the process.

6. Denial Anyone who has been alive long enough realizes that, as the saying goes, “denial is not just a river in Africa.” This is powerfully demonstrated in situations like war or drug abuse, where denial has powerful destructive effects but allows for behavioral inertia. Denying reality can be a coping mechanism, a survival mechanism, or a purposeful tactic.

7. Availability Heuristic One of the most useful findings of modern psychology is what Daniel Kahneman calls the Availability Bias or Heuristic: We tend to most easily recall what is salient, important, frequent, and recent. The brain has its own energy-saving and inertial tendencies that we have little control over – the availability heuristic is likely one of them. Having a truly comprehensive memory would be debilitating. Some sub-examples of the availability heuristic include the Anchoring and Sunk Cost Tendencies.

8. Representativeness Heuristic The three major psychological findings that fall under Representativeness, also defined by Kahneman and his partner Tversky, are:

a. Failure to Account for Base Rates An unconscious failure to look at past odds in determining current or future behavior.

b. Tendency to Stereotype The tendency to broadly generalize and categorize rather than look for specific nuance. Like availability, this is generally a necessary trait for energy-saving in the brain.

c. Failure to See False Conjunctions Most famously demonstrated by the Linda Test, the same two psychologists showed that students chose more vividly described individuals as more likely to fit into a predefined category than individuals with broader, more inclusive, but less vivid descriptions, even if the vivid example was a mere subset of the more inclusive set. These specific examples are seen as more representative of the category than those with the broader but vaguer descriptions, in violation of logic and probability.

9. Social Proof (Safety in Numbers) Human beings are one of many social species, along with bees, ants, and chimps, among many more. We have a DNA-level instinct to seek safety in numbers and will look for social guidance of our behavior. This instinct creates a cohesive sense of cooperation and culture which would not otherwise be possible but also leads us to do foolish things if our group is doing them as well.

10. Narrative Instinct Human beings have been appropriately called “the storytelling animal” because of our instinct to construct and seek meaning in narrative. It’s likely that long before we developed the ability to write or to create objects, we were telling stories and thinking in stories. Nearly all social organizations, from religious institutions to corporations to nation-states, run on constructions of the narrative instinct.

11. Curiosity Instinct We like to call other species curious, but we are the most curious of all, an instinct which led us out of the savanna and led us to learn a great deal about the world around us, using that information to create the world in our collective minds. The curiosity instinct leads to unique human behavior and forms of organization like the scientific enterprise. Even before there were direct incentives to innovate, humans innovated out of curiosity.

12. Language Instinct The psychologist Steven Pinker calls our DNA-level instinct to learn grammatically constructed language the Language Instinct. The idea that grammatical language is not a simple cultural artifact was first popularized by the linguist Noam Chomsky. As we saw with the narrative instinct, we use these instincts to create shared stories, as well as to gossip, solve problems, and fight, among other things. Grammatically ordered language theoretically carries infinite varying meaning.

13. First-Conclusion Bias As Charlie Munger famously pointed out, the mind works a bit like a sperm and egg: the first idea gets in and then the mind shuts. Like many other tendencies, this is probably an energy-saving device. Our tendency to settle on first conclusions leads us to accept many erroneous results and cease asking questions; it can be countered with some simple and useful mental routines.

14. Tendency to Overgeneralize from Small Samples It’s important for human beings to generalize; we need not see every instance to understand the general rule, and this works to our advantage. With generalizing, however, comes a subset of errors when we forget about the Law of Large Numbers and act as if it does not exist. We take a small number of instances and create a general category, even if we have no statistically sound basis for the conclusion.

15. Relative Satisfaction/Misery Tendencies The envy tendency is probably the most obvious manifestation of the relative satisfaction tendency, but nearly all studies of human happiness show that it is related to the state of the person relative to either their past or their peers, not absolute. These relative tendencies cause us great misery or happiness in a very wide variety of objectively different situations and make us poor predictors of our own behavior and feelings.

16. Commitment & Consistency Bias As psychologists have frequently and famously demonstrated, humans are subject to a bias towards keeping their prior commitments and staying consistent with our prior selves when possible. This trait is necessary for social cohesion: people who often change their conclusions and habits are often distrusted. Yet our bias towards staying consistent can become, as one wag put it, a “hobgoblin of foolish minds” – when it is combined with the first-conclusion bias, we end up landing on poor answers and standing pat in the face of great evidence.

17. Hindsight Bias Once we know the outcome, it’s nearly impossible to turn back the clock mentally. Our narrative instinct leads us to reason that we knew it all along (whatever “it” is), when in fact we are often simply reasoning post-hoc with information not available to us before the event. The hindsight bias explains why it’s wise to keep a journal of important decisions for an unaltered record and to re-examine our beliefs when we convince ourselves that we knew it all along.

18. Sensitivity to Fairness Justice runs deep in our veins. In another illustration of our relative sense of well-being, we are careful arbiters of what is fair. Violations of fairness can be considered grounds for reciprocal action, or at least distrust. Yet fairness itself seems to be a moving target. What is seen as fair and just in one time and place may not be in another. Consider that slavery has been seen as perfectly natural and perfectly unnatural in alternating phases of human existence.

19. Tendency to Overestimate Consistency of Behavior ( Fundamental Attribution Error ) We tend to over-ascribe the behavior of others to their innate traits rather than to situational factors, leading us to overestimate how consistent that behavior will be in the future. In such a situation, predicting behavior seems not very difficult. Of course, in practice this assumption is consistently demonstrated to be wrong, and we are consequently surprised when others do not act in accordance with the “innate” traits we’ve endowed them with.

20. Influence of Stress (Including Breaking Points) Stress causes both mental and physiological responses and tends to amplify the other biases. Almost all human mental biases become worse in the face of stress as the body goes into a fight-or-flight response, relying purely on instinct without the emergency brake of Daniel Kahneman’s “System 2” type of reasoning. Stress causes hasty decisions, immediacy, and a fallback to habit, thus giving rise to the elite soldiers’ motto: “In the thick of battle, you will not rise to the level of your expectations, but fall to the level of your training.”

21. Survivorship Bias A major problem with historiography – our interpretation of the past – is that history is famously written by the victors. We do not see what Nassim Taleb calls the “silent grave” – the lottery ticket holders who did not win. Thus, we over-attribute success to things done by the successful agent rather than to randomness or luck, and we often learn false lessons by exclusively studying victors without seeing all of the accompanying losers who acted in the same way but were not lucky enough to succeed.

22. Tendency to Want to Do Something (Fight/Flight, Intervention, Demonstration of Value, etc.) We might term this Boredom Syndrome: Most humans have the tendency to need to act, even when their actions are not needed. We also tend to offer solutions even when we do not have knowledge to solve the problem.