- Our Mission

3 Simple Strategies to Improve Students’ Problem-Solving Skills

These strategies are designed to make sure students have a good understanding of problems before attempting to solve them.

Research provides a striking revelation about problem solvers. The best problem solvers approach problems much differently than novices. For instance, one meta-study showed that when experts evaluate graphs , they tend to spend less time on tasks and answer choices and more time on evaluating the axes’ labels and the relationships of variables within the graphs. In other words, they spend more time up front making sense of the data before moving to addressing the task.

While slower in solving problems, experts use this additional up-front time to more efficiently and effectively solve the problem. In one study, researchers found that experts were much better at “information extraction” or pulling the information they needed to solve the problem later in the problem than novices. This was due to the fact that they started a problem-solving process by evaluating specific assumptions within problems, asking predictive questions, and then comparing and contrasting their predictions with results. For example, expert problem solvers look at the problem context and ask a number of questions:

- What do we know about the context of the problem?

- What assumptions are underlying the problem? What’s the story here?

- What qualitative and quantitative information is pertinent?

- What might the problem context be telling us? What questions arise from the information we are reading or reviewing?

- What are important trends and patterns?

As such, expert problem solvers don’t jump to the presented problem or rush to solutions. They invest the time necessary to make sense of the problem.

Now, think about your own students: Do they immediately jump to the question, or do they take time to understand the problem context? Do they identify the relevant variables, look for patterns, and then focus on the specific tasks?

If your students are struggling to develop the habit of sense-making in a problem- solving context, this is a perfect time to incorporate a few short and sharp strategies to support them.

3 Ways to Improve Student Problem-Solving

1. Slow reveal graphs: The brilliant strategy crafted by K–8 math specialist Jenna Laib and her colleagues provides teachers with an opportunity to gradually display complex graphical information and build students’ questioning, sense-making, and evaluating predictions.

For instance, in one third-grade class, students are given a bar graph without any labels or identifying information except for bars emerging from a horizontal line on the bottom of the slide. Over time, students learn about the categories on the x -axis (types of animals) and the quantities specified on the y -axis (number of baby teeth).

The graphs and the topics range in complexity from studying the standard deviation of temperatures in Antarctica to the use of scatterplots to compare working hours across OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. The website offers a number of graphs on Google Slides and suggests questions that teachers may ask students. Furthermore, this site allows teachers to search by type of graph (e.g., scatterplot) or topic (e.g., social justice).

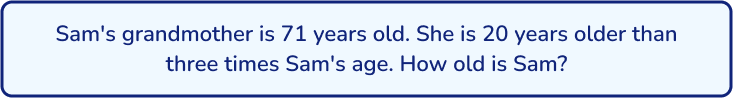

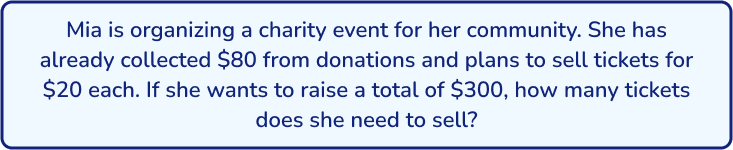

2. Three reads: The three-reads strategy tasks students with evaluating a word problem in three different ways . First, students encounter a problem without having access to the question—for instance, “There are 20 kangaroos on the grassland. Three hop away.” Students are expected to discuss the context of the problem without emphasizing the quantities. For instance, a student may say, “We know that there are a total amount of kangaroos, and the total shrinks because some kangaroos hop away.”

Next, students discuss the important quantities and what questions may be generated. Finally, students receive and address the actual problem. Here they can both evaluate how close their predicted questions were from the actual questions and solve the actual problem.

To get started, consider using the numberless word problems on educator Brian Bushart’s site . For those teaching high school, consider using your own textbook word problems for this activity. Simply create three slides to present to students that include context (e.g., on the first slide state, “A salesman sold twice as much pears in the afternoon as in the morning”). The second slide would include quantities (e.g., “He sold 360 kilograms of pears”), and the third slide would include the actual question (e.g., “How many kilograms did he sell in the morning and how many in the afternoon?”). One additional suggestion for teams to consider is to have students solve the questions they generated before revealing the actual question.

3. Three-Act Tasks: Originally created by Dan Meyer, three-act tasks follow the three acts of a story . The first act is typically called the “setup,” followed by the “confrontation” and then the “resolution.”

This storyline process can be used in mathematics in which students encounter a contextual problem (e.g., a pool is being filled with soda). Here students work to identify the important aspects of the problem. During the second act, students build knowledge and skill to solve the problem (e.g., they learn how to calculate the volume of particular spaces). Finally, students solve the problem and evaluate their answers (e.g., how close were their calculations to the actual specifications of the pool and the amount of liquid that filled it).

Often, teachers add a fourth act (i.e., “the sequel”), in which students encounter a similar problem but in a different context (e.g., they have to estimate the volume of a lava lamp). There are also a number of elementary examples that have been developed by math teachers including GFletchy , which offers pre-kindergarten to middle school activities including counting squares , peas in a pod , and shark bait .

Students need to learn how to slow down and think through a problem context. The aforementioned strategies are quick ways teachers can begin to support students in developing the habits needed to effectively and efficiently tackle complex problem-solving.

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

8 Chapter 6 Supporting Student Problem-Solving

Across content areas, the standards address problem-solving in the form of being able to improvise, decide, inquire, and research. In fact, math and science standards are premised almost completely on problem-solving and inquiry. According to the literature, however, problem-solving and inquiry are often overlooked or addressed only superficially in classrooms, and in some subject areas, are not attended to at all.

OVERVIEW OF PROBLEM-SOLVING AND INQUIRY IN K–12 CLASSROOMS

In keeping with a learning focus, this chapter first discusses problem-solving and inquiry to provide a basis from which teachers can provide support for these goals with technology.

What Is Problem-solving?

Whereas production is a process that focuses on an end-product, problem-solving is a process that centers on a problem. Students apply critical and creative thinking skills to prior knowledge during the problem-solving process. The end result of problem-solving is typically some kind of decision, in other words, choosing a solution and then evaluating it.

There are two general kinds of problems. Close-ended problems are those with known solutions to which students can apply a process similar to one that they have already used. For example, if a student understands the single-digit process in adding 2 plus 2 to make 4, she most likely will be able to solve a problem that asks her to add 1 plus 1. Open-ended or loosely structured problems, on the other hand, are those with many or unknown solutions rather than one correct answer. These types of problems require the ability to apply a variety of strategies and knowledge to finding a solution. For example, an open-ended problem statement might read:

A politician has just discovered information showing that a statement he made to the public earlier in the week was incorrect. If he corrects himself he will look like a fool, but if he doesn’t and someone finds out the truth, he will be in trouble. What should he do or say about this?

Obviously, there is no simple answer to this question, and there is a lot of information to consider.

Many textbooks, teachers, and tests present or ask only for the results of problem-solving and not the whole process that students must go through in thinking about how to arrive at a viable solution. As a result, according to the literature, most people use their personal understandings to try to solve open-ended problems, but the bias of limited experience makes it hard for people to understand the trade-offs or contradictions that these problems present. To solve such problems, students need to be able to use both problem-solving skills and an effective inquiry process.

What Is Inquiry?

Inquiry in education is also sometimes called research, investigation, or guided discovery. During inquiry, students ask questions and then search for answers to those questions. In doing so, they come to new understandings in content and language. Although inquiry is an instructional strategy in itself, it is also a central component of problem-solving when students apply their new understandings to the problem at hand. Each question that the problem raises must be addressed by thorough and systematic investigation to arrive at a well-grounded solution. Therefore, the term “problem-solving” can be considered to include inquiry.

For students to understand both the question and ways of looking at the answer(s), resources such as historical accounts, literature, art, and eyewitness experiences must be used. In addition, each resource must be examined in light of what each different type of material contributes to the solution. Critical literacy, or reading beyond the text, then, is a fundamental aspect of inquiry and so of problem-solving. Search for critical literacy resources by using “critical literacy” and your grade level, and be sure to look at the tools provided in this text’s Teacher Toolbox.

What Is Problem-Based Learning?

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a teaching approach that combines critical thinking, problem- solving skills, and inquiry as students explore real-world problems. It is based on unstructured, complex, and authentic problems that are often presented as part of a project. PBL addresses many of the learning goals presented in this text and across the standards, including communication, creativity, and often production.

Research is being conducted in every area from business to education to see how we solve problems, what guides us, what information we have and use during problem-solving, and how we can become more efficient problem solvers. There are competing theories of how people learn to and do solve problems, and much more research needs to be done. However, we do know several things. First, problem-solving can depend on the context, the participants, and the stakeholders. In addition, studies show that content appears to be covered better by “traditional” instruction, but students retain better after problem-solving. PBL has been found effective at teaching content and problem-solving, and the use of technology can make those gains even higher (Chauhan, 2017). Research clearly shows that the more parts of a problem there are, the less successful students will be at solving it. However, effective scaffolding can help to support students’ problem-solving and overcomes some of the potential issues with it (Belland, Walker, Kim, & Lefler, 2017).

The PBL literature points out that both content knowledge and problem-solving skills are necessary to arrive at solutions, but individual differences among students affect their success, too. For example, field-independent students in general do better than field-dependent students in tasks. In addition, students from some cultures will not be familiar with this kind of learning, and others may not have the language to work with it. Teachers must consider all of these ideas and challenges in supporting student problem-solving.

Characteristics of effective technology-enhanced problem-based learning tasks

PBL tasks share many of the same characteristics of other tasks in this book, but some are specific to PBL. Generally, PBL tasks:

Involve learners in gaining and organizing knowledge of content. Inspiration and other concept-mapping tools like the app Popplet are useful for this.

Help learners link school activities to life, providing the “why” for doing the activity.

Give students control of their learning.

Have built-in and just-in-time scaffolding to help students. Tutorials are available all over the Web for content, language, and technology help.

Are fun and interesting.

Contain specific objectives for students to meet along the way to a larger goal.

Have guidance for the use of tools, especially computer technologies.

Include communication and collaboration (described in chapter 3).

Emphasize the process and the content.

Are central to the curriculum, not peripheral or time fillers.

Lead to additional content learning.

Have a measurable, although not necessarily correct, outcome.

More specifically, PBL tasks:

Use a problem that “appeals to human desire for resolution/stasis/harmony” and “sets up need for and context of learning which follows” (IMSA, 2005, p. 2).

Help students understand the range of problem-solving mechanisms available.

Focus on the merits of the question, the concepts involved, and student research plans.

Provide opportunities for students to examine the process of getting the answer (for example, looking back at the arguments).

Lead to additional “transfer” problems that use the knowledge gained in a different context.

Not every task necessarily exhibits all of these characteristics completely, but these lists can serve as guidelines for creating and evaluating tasks.

Student benefits of problem-solving

There are many potential benefits of using PBL in classrooms at all levels; however, the benefits depend on how well this strategy is employed. With effective PBL, students can become more engaged in their learning and empowered to become more autonomous in classroom work. This, in turn, may lead to improved attitudes about the classroom and thus to other gains such as increased abilities for social-problem solving. Students can gain a deeper understanding of concepts, acquire skills necessary in the real world, and transfer skills to become independent and self-directed learners and thinkers outside of school. For example, when students are encouraged to practice using problem-solving skills across a variety of situations, they gain experience in discovering not only different methods but which method to apply to what kind of problem. Furthermore, students can become more confident when their self-esteem and grade does not depend only on the specific answer that the teacher wants. In addition, during the problem-solving process students can develop better critical and creative thinking skills.

Students can also develop better language skills (both knowledge and communication) through problems that require a high level of interaction with others (Verga & Kotz, 2013). This is important for all learners, but especially for ELLs and others who do not have grade-level language skills. For students who may not understand the language or content or a specific question, the focus on process gives them more opportunities to access information and express their knowledge.

The problem-solving process

The use of PBL requires different processes for students and teachers. The teacher’s process involves careful planning. There are many ways for this to happen, but a general outline that can be adapted includes the following steps:

After students bring up a question, put it in the greater context of a problem to solve (using the format of an essential question; see chapter 4) and decide what the outcome should be–a recommendation, a summary, a process?

Develop objectives that represent both the goal and the specific content, language, and skills toward which students will work.

List background information and possible materials and content that will need to be addressed. Get access to materials and tools and prepare resource lists if necessary.

Write the specific problem. Make sure students know what their role is and what they are expected to do. Then go back and check that the problem and task meet the objectives and characteristics of effective PBL and the relevant standards. Reevaluate materials and tools.

Develop scaffolds that will be needed.

Evaluate and prepare to meet individual students’ needs for language, assistive tools, content review, and thinking skills and strategies

Present the problem to students, assess their understanding, and provide appropriate feedback as they plan and carry out their process.

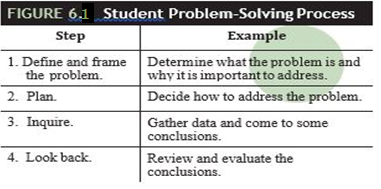

The student process focuses more on the specific problem-solving task. PBL sources list different terms to describe each step, but the process is more or less the same. Students:

Define and frame the problem: Describe it, recognize what is being asked for, look at it from all sides, and say why they need to solve it.

Plan: Present prior knowledge that affects the problem, decide what further information and concepts are needed, and map what resources will be consulted and why.

Inquire: Gather and analyze the data, build and test hypotheses.

Look back: Review and evaluate the process and content. Ask “What do I understand from this result? What does it tell me?”

These steps are summarized in Figure 6.1.

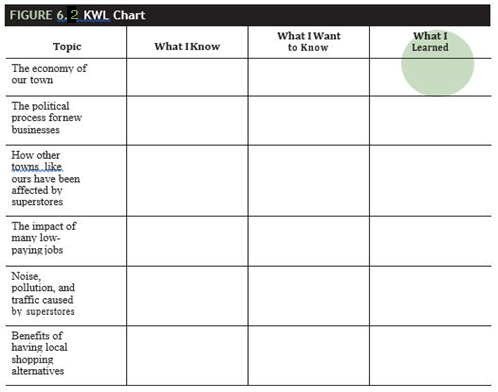

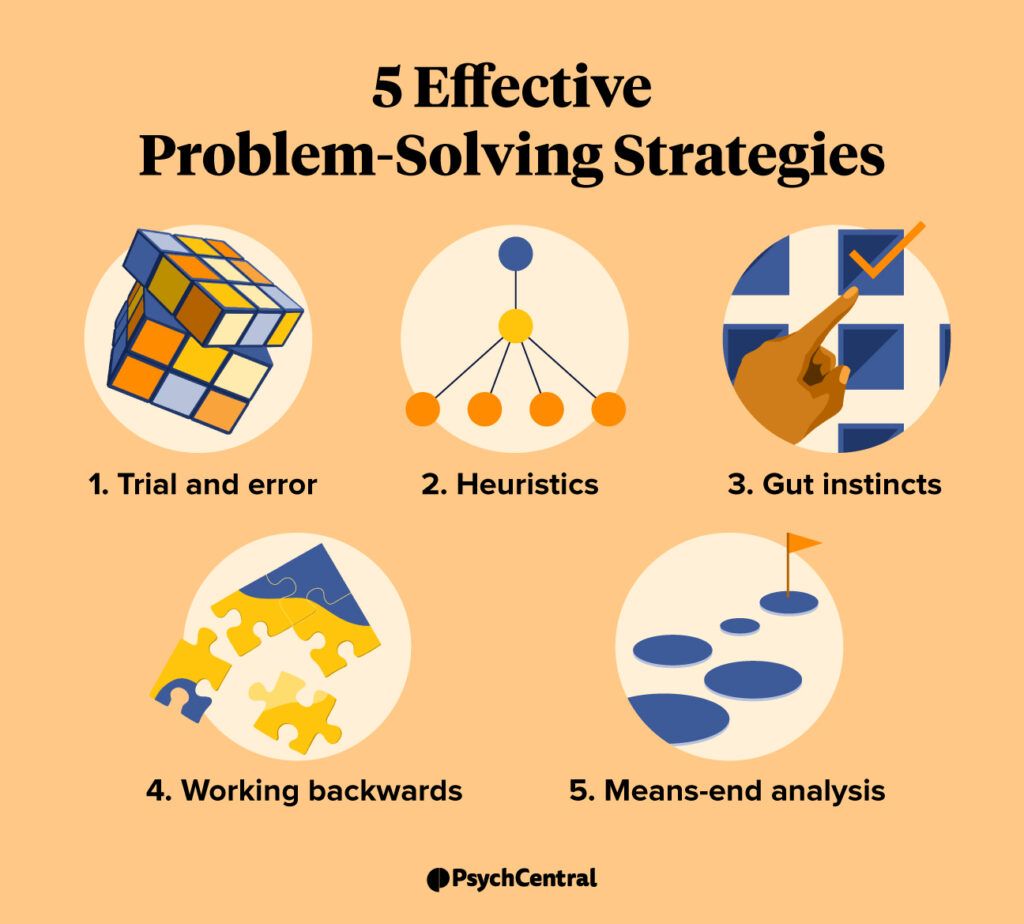

Problem-solving strategies that teachers can demonstrate, model, and teach directly include trial and error, process of elimination, making a model, using a formula, acting out the problem, using graphics or drawing the problem, discovering patterns, and simplifying the problem (e.g., rewording, changing the setting, dividing it into simpler tasks). Even the popular KWL (Know, Want to Know, Learned) chart can help students frame questions. A KWL for a project asking whether a superstore should be built in the community might look like the one in Figure 6.2. Find out more about these strategies at http://literacy.kent.edu/eureka/strategies/discuss-prob.html .

Teaching problem-solving in groups involves the use of planning and other technologies. Using these tools, students post, discuss, and reflect on their joint problem-solving process using visual cues that they create. This helps students focus on both their process and the content. Throughout the teacher and student processes, participants should continue to examine cultural, emotional, intellectual, and other possible barriers to problem-solving.

Teachers and Problem-solving

The teacher’s role in PBL

During the teacher’s process of creating the problem context, the teacher must consider what levels of authenticity, complexity, uncertainty, and self-direction students can access and work within. Gordon (1998) broke loosely structured problems into three general types with increasing levels of these aspects. Still in use today, these are:

Academic challenges. An academic challenge is student work structured as a problem arising directly from an area of study. It is used primarily to promote greater understanding of selected subject matter. The academic challenge is crafted by transforming existing curricular material into a problem format.

Scenario challenges. These challenges cast students in real-life roles and ask them to perform these roles in the context of a reality-based or fictional scenario.

Real-life problems. These are actual problems in need of real solutions by real people or organizations. They involve students directly and deeply in the exploration of an area of study. And the solutions have the potential for actual implementation at the classroom, school, community, regional, national, or global level. (p. 3)

To demonstrate the application of this simple categorization, the learning activities presented later in this chapter follow this outline.

As discussed in other chapters in this book, during student work the teacher’s role can vary from director to shepherd, but when the teacher is a co-learner rather than a taskmaster, learners become experts. An often-used term for the teacher’s role in the literature about problem-solving is “coach.” As a coach, the teacher works to facilitate thinking skills and process, including working out group dynamics, keeping students on task and making sure they are participating, assessing their progress and process, and adjusting levels of challenge as students’ needs change. Teachers can provide hints and resources and work on a gradual release of responsibility to learners.

Challenges for teachers

For many teachers, the roles suggested above are easier said than done. To use a PBL approach, teachers must break out of the content-dissemination mode and help their students to do the same. Even when this happens, in many classrooms students have been trained to think that problem-solving is getting the one right answer, and it takes time, practice, and patience for them to understand otherwise. Some teachers feel that they are obligated to cover too much in the curriculum to spend time on PBL or that using real-world problems does not mesh well with the content, materials, and context of the classroom. However, twenty years ago Gordon (1998) noted, “whether it’s a relatively simple matter of deciding what to eat for breakfast or a more complex one such as figuring out how to reduce pollution in one’s community, in life we make decisions and do things that have concrete results. Very few of us do worksheets” (p. 2). He adds that not every aspect of students’ schoolwork needs to be real, but that connections should be made from the classroom to the real world. Educators around the world are still working toward making school more like life.

In addition, many standardized district and statewide tests do not measure process, so students do not want to spend time on it. However, teachers can overcome this thinking by demonstrating to students the ways in which they need to solve problems every day and how these strategies may transfer to testing situations.

Furthermore, PBL tasks and projects may take longer to develop and assess than traditional instruction. However, teachers can start slowly by helping students practice PBL in controlled environments with structure, then gradually release them to working independently. The guidelines in this chapter address some of these challenges.

GUIDELINES FOR TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED PROBLEM-SOLVING

Obviously, PBL is more than simply giving students a problem and asking them to solve it. The following guidelines describe other issues in PBL.

Designing Problem-Solving Opportunities

The guidelines described here can assist students in developing a PBL opportunity.

Guideline #1: Integrate reading and writing. Although an important part of solving problems, discussion alone is not enough for students to develop and practice problem-solving skills. Effective problem-solving and inquiry require students to think clearly and deeply about content, language, and process. Reading and writing tasks can encourage students to take time to think about these issues and to contextualize their thinking practice. They can also provide vehicles for teachers to understand student progress and to provide concrete feedback. Students who have strengths in these areas will be encouraged and those who need help can learn from their stronger partners, just as those who have strengths in speaking can model for and assist their peers during discussion. Even in courses that do not stress reading and writing, integrating these skills into tasks and projects can promote successful learning.

Guideline #2: Avoid plagiarism. The Internet is a great resource for student inquiry and problem-solving. However, when students read and write using Internet resources, they often cut and paste directly from the source. Sometimes this is an innocent mistake; students may be uneducated about the use of resources, perhaps they come from a culture where the concept of ownership is completely different than in the United States, or maybe their language skills are weak and they want to be able to express themselves better. In either case, two strategies can help avoid plagiarism: 1) The teacher can teach directly about plagiarism and copyright issues. Strategies including helping students learn how to cite sources, paraphrase, summarize, and restate; 2) The teacher can be as familiar as possible with the resources that students will use and check for plagiarism when it is suspected. To do so, the teacher can enter a sentence or phrase into any Web browser with quote marks around it and if the entry is exact, the original source will come up in the browser window. Essay checkers such as Turnitin (http://turnitin.com/) are also available online that will check a passage or an entire essay.

Guideline #3: Do not do what students can do. Teaching, and particularly teaching with technology, is often a difficult job, due in part to the time it takes teachers to prepare effective learning experiences. Planning, developing, directing, and assessing do not have to be solely the teacher’s domain, however. Students should take on many of these responsibilities, and at the same time gain in problem-solving, language, content, critical thinking, creativity, and other crucial skills. Teachers do not always need to click the mouse, write on the whiteboard, decide

criteria for a rubric, develop questions, decorate the classroom, or perform many classroom and learning tasks. Students can take ownership and feel responsibility. Although it is often difficult for teachers to give up some of their power, the benefits of having more time and shared responsibility can be transformational. Teachers can train themselves to ask, “Is this something students can do?”

Guideline #4: Make mistakes okay. Problem-solving often involves coming to dead ends, having to revisit data and reformulate ideas, and working with uncertainty. For students used to striving for correct answers and looking to the teacher as a final authority, the messiness of problem-solving can be disconcerting, frustrating, and even scary. Teachers can create environments of acceptance where reasoned, even if wrong, answers are recognized, acknowledged, and given appropriate feedback by the teacher and peers. Teachers already know that students come to the task with a variety of beliefs and information. In working with students’ prior knowledge, they can model how to be supportive of students’ faulty ideas and suggestions. They can also ask positive questions to get the students thinking about what they still need to know and how they can come to know it. They can both encourage and directly teach students to be supportive of mistakes and trials as part of their team-building and leadership skills.

In addition, teachers may need to help students to understand that even a well-reasoned argument or answer can meet with opposition. Students must not feel that they have made a bad decision just because everyone else, particularly the teacher, does not agree. Teachers can model for students that they are part of the learning process and they are impartial as to the outcome when the student’s position has been well defended.

PROBLEM-SOLVING AND INQUIRY TECHNOLOGIES

As with all the goals in this book, the focus of technology in problem-solving is not on the technology itself but on the learning experiences that the technology affords. Different tools exist to support different parts of the process. Some are as simple as handouts that students can print and complete, others as complex as modeling and visualization software. Many software tools that support problem-solving are made for experts in the field and are relatively difficult to learn and use. Examples of these more complicated programs include many types of computer-aided design software, advanced authoring tools, and complex expert systems. In the past there were few software tools for K–12 students that addressed the problem-solving process directly and completely, but more apps are being created all the time that do so. See the Teacher Tools for this text for examples.

Simple inquiry tools that help students perform their investigations during PBL are much more prevalent. The standard word processor, database, concept mapping/graphics and spreadsheet software can all assist students in answering questions and organizing and presenting data, but there are other tools more specifically designed to support inquiry. Software programs that can be used within the PBL framework are mentioned in other chapters in this text. These programs, such as the Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic programs mentioned in chapter 2 address the overlapping goals of collaboration, production, critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving. Interestingly, even video games might be used as problem-solving tools. Many of these games require users to puzzle out directions, to find missing artifacts, or to follow clues that are increasingly difficult to find and understand. One common tool with which students at all levels might be familiar is Minecraft (Mojang; https://minecraft.net/en-us/). The Internet has as many resources as teachers might need to use Minecraft across the disciplines to teach whole units and even gamify the classroom.

The following section presents brief descriptions of tools that can support the PBL process. The examples are divided into stand-alone tools that can be used on one or more desktops and Web-based tools.

Stand-Alone Tools

Example 1: Fizz and Martina’s Math Adventures (Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic)

Students help Fizz and Martina, animated characters in this software, to solve problems by figuring out which data is relevant, performing appropriate calculations, and presenting their solutions. The five titles in this series are perfect for a one-computer classroom. Each software package combines computer-based video, easy navigation, and handouts and other resources as scaffolds. This software is useful in classrooms with ELLs because of the combination of visual, audio, and text-based reinforcement of input. It is also accessible to students with physical disabilities because it can run on one computer; students do not have to actually perform the mouse clicks to run the software themselves.

This software is much more than math. It includes a lot of language, focuses on cooperation and collaboration in teams, and promotes critical thinking as part of problem-solving. Equally important, it helps students to communicate mathematical ideas orally and in writing. See Figure 6.6 for the “getting started” screen from Fizz and Martina to view some of the choices that teachers and students have in using this package.

Example 2: I Spy Treasure Hunt, I Spy School Days, I Spy Spooky Mansion (Scholastic)

The language in these fun simulations consists of isolated, discrete words and phrases, making these programs useful for word study but not for overall concept learning. School Days, for example, focuses on both objects and words related to school. However, students work on extrapolation, trial and error, process of elimination, and other problem-solving strategies. It is difficult to get students away from the computer once they start working on any of the simulations in this series. Each software package has several separate hunts with a large number of riddles that, when solved, allow the user to put together a map or other clues to find the surprise at the end. Some of the riddles involve simply finding an item on the screen, but others require more thought such as figuring out an alternative representation for the item sought or using a process of elimination to figure out where to find it. All of the riddles are presented in both text and audio and can be repeated as many times as the student requires, making it easier for language learners, less literate students, and students with varied learning preferences to access the information. Younger students can also work with older students or an aide for close support so that students are focused. Free versions of the commercial software and similar types of programs such as escape rooms (e.g., escapes at 365 Escape {http://www.365escape.com/Room-Escape-Games.html] and www.primarygames.com) can be found across the Web.

There are many more software packages like these that can be part of a PBL task. See the Teacher Toolbox for ideas.

Example 3: Science Court (Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic)

Twelve different titles in this series present humorous court cases that students must help to resolve. Whether the focus is on the water cycle, soil, or gravity, students use animated computer-based video, hands-on science activities, and group work to learn and practice science and the inquiry process. As students work toward solving the case, they examine not only the facts but also their reasoning processes. Like Fizz and Martina and much of TSP’s software, Science Court uses multimedia and can be used in the one-computer classroom (as described in chapter 2), making it accessible to diverse students.

Example 4: Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

The use of GIS to track threatened species, map hazardous waste or wetlands in the community, or propose solutions for other environmental problems supports student “spatial literacy and geographic competence” (Baker, 2005, n.p.), in addition to experimental and inquiry techniques, understanding of scale and resolution, and verification skills. Popular desktop-based GIS that students can access include Geodesy and ArcVoyager; many Web-based versions also exist. A GIS is not necessarily an easy tool to learn or use, but it can lead to real-world involvement and language, concept, and thinking skills development.

Web-Based Tools

Many technology-enhanced lessons and tools on the Web come premade. In other words, they were created for someone else’s students and context. Teachers must adapt these tools to fit their own teaching styles, student needs, goals, resources, and contextual variables. Teachers must learn to modify these resources to make them their own and help them to work effectively in their unique teaching situation. With this in mind, teachers can take advantage of the great ideas in the Web-based tools described below.

Example 1: WebQuest

A WebQuest is a Web-based inquiry activity that is highly structured in a preset format. Most teachers are aware of WebQuests—a Web search finds them mentioned in every state, subject area, and grade level, and they are popular topics at conferences and workshops. Created by Bernie Dodge and Tom March in 1995 (see http://webquest.org/), this activity has proliferated wildly.

Each WebQuest has six parts. The Quest starts with an introduction to excite student interest. The task description then explains to students the purpose of the Quest and what the outcome will be. Next, the process includes clear steps and the scaffolds, including resources, that students will need to accomplish the steps. The evaluation section provides rubrics and assessment guidelines, and the conclusion section provides closure. Finally, the teacher section includes hints and tips for other teachers to use the WebQuest.

Advantages to using WebQuests as inquiry and problem-solving tools include:

Students are focused on a specific topic and content and have a great deal of scaffolding.

Students focus on using information rather than looking for it, because resources are preselected.

Students use collaboration, critical thinking, and other important skills to complete their Quest.

Teachers across the United States have reported significant successes for students participating in Quests. However, because Quests can be created and posted by anyone, many found on the Web do not meet standards for inquiry and do not allow students autonomy to work in authentic settings and to solve problems. Teachers who want to use a WebQuest to meet specific goals should examine carefully both the content and the process of the Quest to make sure that they offer real problems as discussed in this chapter. A matrix of wonderful Quests that have been evaluated as outstanding by experts is available on the site.

Although very popular, WebQuests are also very structured. This is fine for students who have not moved to more open-ended problems, but to support a higher level of student thinking, independence, and concept learning, teachers can have students work in teams on Web Inquiry Projects ( http://webinquiry.org/ ).

Example 2: Virtual Field Trips

Virtual field trips are great for concept learning, especially for students who need extra support from photos, text, animation, video, and audio. Content for field trips includes virtual walks through museums, underwater explorations, house tours, and much more (see online field trips suggested by Steele-Carlin [2014] at http://www.educationworld.com/a_tech/tech/tech071.shtml ). However, the format of virtual field trips ranges from simple postcard-like displays to interactive video simulations, and teachers must review the sites before using them to make sure that they meet needs and goals.

With a virtual reality headset (now available for sale cheaply even at major department stores), teachers and students can go on Google Expeditions ( https://edu.google.com/expeditions/ ), 3D immersive field trips from Nearpod ( http://nearpod.com ), and even create their using resources from Larry Ferlazzo’s “Best Resources for Finding and Creating Virtual Field Trips” at http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org/2009/08/11/the-best-resources-for-finding-and-creating-virtual-field-trips/.

Example 3: Raw Data Sites

Raw data sites abound on the Web, from the U.S. Census to the National Climatic Data Center, from databases full of language data to the Library of Congress. These sites can be used for content learning and other learning goals. Some amazing sites can be found where students can collect their own data. These include sites like John Walker’s (2003) Your Sky (www.fourmilab.to/yoursky) and Water on the Web (2005, waterontheweb.org). When working with raw data students have to draw their own conclusions based on evidence. This is another important problem-solving skill. Note that teachers must supervise and verify that data being entered for students across the world is accurate or

Example 4: Filamentality

Filamentality (https://keithstanger.com/filamentality.html) presents an open-ended problem with a lot of scaffolding. Students and/or teachers start with a goal and then create a Web site in one of five formats that range in level of inquiry and problem-solving from treasure hunts to WebQuests. The site provides lots of help and hints for those who need it, including “Mentality Tips” to help accomplish goals. It is free and easy to use, making it accessible to any teacher (or student) with an Internet connection.

Example 5: Problem Sites

Many education sites offer opportunities for students to solve problems. Some focus on language (e.g., why do we say “when pigs fly”?) or global history (e.g., what’s the real story behind Tut’s tomb?); see, for example, the resources and questions in The Ultimate STEM Guide for Students at http://www.mastersindatascience.org/blog/the-ultimate-stem-guide-for-kids-239-cool-sites-about-science-technology-engineering-and-math/. These problems range in level from very structured, academic problems to real-world unsolved mysteries.

The NASA SciFiles present problems in a format similar to WebQuests at https://knowitall.org/series/nasa-scifiles. In other parts of the Web site there are video cases, quizzes, and tools for problem-solving.

There is an amazing number of tools, both stand-alone and Web-based, to support problem-solving and inquiry, but no tool can provide all the features that meet the needs of all students. Most important in tool choice is that it meets the language, content, and skills goals of the project and students and that there is a caring and supportive teacher guiding the students in their choice and use of the tool.

Teacher Tools

There are many Web sites addressed specifically to teachers who are concerned that they are not familiar enough with PBL or that they do not have the tools to implement this instructional strategy. For example, from Now On at http://www.fno.org/ toolbox.html provides specific suggestions for how to integrate technology and inquiry. Search “problem-solving” on the amazing Edutopia site ( https://www.edutopia.org/ ) for ideas, guidelines, examples, and more.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES: PROBLEM-SOLVING AND INQUIRY

In addition to using the tools described in the previous section to teach problem-solving and inquiry, teachers can develop their own problems according to the guidelines throughout this chapter. Gordon’s (1998) scheme of problem-solving levels (described previously)—academic, scenario, and real life—is a simple and useful one. Teachers can refer to it to make sure that they are providing appropriate structure and guidance and helping students become independent thinkers and learners. This section uses Gordon’s levels to demonstrate the variety of problem-solving and inquiry activities in which students can participate. Each example is presented with the question/problem to be answered or solved, a suggestion of a process that students might follow, and some of the possible electronic tools that might help students to solve the problem.

Academic problems

Example 1: What Will Harry Do? (Literature)

Problem: At the end of the chapter, Harry Potter is faced with a decision to make. What will he do?

Process: Discuss the choices and consequences. Choose the most likely, based on past experience and an understanding of the story line. Make a short video to present the solution. Test it against Harry’s decision and evaluate both the proposed solution and the real one.

Tools: Video camera and video editing software.

Example 2: Treasure Hunt (History)

Problem: Students need resources to learn about the Civil War.

Process: Teacher provides a set of 10 questions to find specific resources online.

Tools: Web browser.

Example 3: Problem of the Week (Math)

Problem: Students should solve the math problem of the week.

Process: Students simplify the problem, write out their solution, post it to the site for feedback, then revise as necessary.

Tools: Current problems from the Math Forum@Drexel, http://mathforum.org/pow/

Example 1: World’s Best Problem Solver

Problem: You are a member of a committee that is going to give a prestigious international award for the world’s best problem-solver. You must nominate someone and defend your position to the committee, as the other committee members must do.

Process: Consult and list possible nominees. Use the process of elimination to determine possible nominees. Research the nominees using several different resources. Weigh the evidence and make a choice. Prepare a statement and support.

Tools: Biography.com has over 25,000 biographies, and Infoplease (infoplease.com) and the Biographical Dictionary (http://www.s9.com/) provide biographies divided into categories for easy searching.

Example 2: Curator

Problem: Students are a committee of curators deciding what to hang in a new community art center. They have access to any painting in the world but can only hang 15 pieces in their preset space. Their goals are to enrich art appreciation in the community, make a name for their museum, and make money.

Process: Students frame the problem, research and review art from around the world, consider characteristics of the community and other relevant factors, choose their pieces, and lay them out for presentation to the community.

Tools: Art museum Web sites, books, and field trips for research and painting clips; computer-aided design, graphics, or word processing software to lay out the gallery for viewing.

Example 3: A New National Anthem

Problem: Congress has decided that the national anthem is too difficult to remember and sing and wants to adopt a new, easier song before the next Congress convenes. They want input from musicians across the United States. Students play the roles of musicians of all types.

Process: Students define the problem (e.g., is it that “The Star-Spangled Banner” is too difficult or that Congress needs to be convinced that it is not?). They either research and choose new songs or research and defend the current national anthem. They prepare presentations for members of Congress.

Tools: Music sites and software, information sites on the national anthem.

Real-life problems

Example 1: Racism in School

Problem: There have been several incidents in our school recently that seem to have been racially motivated. The principal is asking students to consider how to make our school a safe learning environment for all students.

Process: Determine what is being asked—the principal wants help. Explore the incidents and related issues. Weigh the pros and cons of different solutions. Prepare solutions to present to the principal.

Tools: Web sites and other resources about racism and solutions, graphic organizers to organize the information, word processor or presentation software for results. Find excellent free tools for teachers and students at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance Web site at www.tolerance.org.

Example 2: Homelessness vs. Education

Problem: The state legislature is asking for public input on the next budget. Because of a projected deficit, political leaders are deciding which social programs, including education and funding for the homeless, should be cut and to what extent. They are interested in hearing about the effects of these programs on participants and on where cuts could most effectively be made.

Process: Decide what the question is (e.g., how to deal with the deficit? How to cut education or funding for the homeless? Which programs are more important? Something else?). Perform a cost-benefit analysis using state data. Collect other data by interviewing and researching. Propose and weigh different solution schemes and propose a suggestion. Use feedback to improve or revise.

Tools: Spreadsheet for calculations, word processor for written solution, various Web sites and databases for costs, electronic discussion list or email for interviews.

Example 3: Cleaning Up

Problem: Visitors and residents in our town have been complaining about the smell from the university’s experimental cattle farms drifting across the highway to restaurants and stores in the shopping center across the street. They claim that it makes both eating and shopping unpleasant and that something must be done.

Process: Conduct onsite interviews and investigation. Determine the source of the odor. Measure times and places where the odor is discernible. Test a variety of solutions. Choose the most effective solution and write a proposal supported by a poster for evidence.

Tools: Online and offline sources of information on cows, farming, odor; database to organize and record data; word processing and presentation software for describing the solution.

These activities can all be adapted and different tools and processes used. As stated previously, the focus must be both on the content to be learned and the skills to be practiced and acquired. More problem-solving activity suggestions and examples can be found at site at http://www.2learn.ca/.

ASSESSING LEARNER PROBLEM-SOLVING AND INQUIRY

Many of the assessments described in other chapters of this text, for example, rubrics, performance assessments, observation, and student self-reflection, can also be employed to assess problem-solving and inquiry. Most experts on problem-solving and inquiry agree that schools need to get away from testing that does not involve showing process or allowing students to problem-solve; rather, teachers should evaluate problem-solving tasks as if they were someone in the real-world context of the problem. For example, if students are studying an environmental issue, teachers can evaluate their work throughout the project from the standpoint of someone in the field, being careful that their own biases do not cloud their judgment on controversial issues. Rubrics, multiple-choice tests, and other assessment tools mentioned in other chapters of this text can account for the multiple outcomes that are possible in content, language, and skills learning. These resources can be used as models for assessing problem-solving skills in a variety of tasks. Find hundreds of problem-solving rubrics by searching the Web for “problem-solving rubrics” or check Pinterest for teacher-created rubrics.

In addition to the techniques mentioned above, many teachers suggest keeping a weekly problem-solving notebook (also known as a math journal or science journal), in which students record problem solutions, strategies they used, similarities with other problems, extensions of the problem, and an investigation of one or more of the extensions. Using this notebook to assess students’ location and progress in problem-solving could be very effective, and it could even be convenient if learners can keep them online as a blog or in a share cloud space.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

Research and Plagiarism

We’ve been working on summaries all year and the idea that copying word for word is plagiarism. When they come to me (sixth grade) they continue to struggle with putting things in their own words so [Microsoft Encarta] Researcher not only provides a visual (a reference in APA format) that this is someone else’s work, but allows me to see the information they used to create their report as Researcher is an electronic filing system. It’s as if students were printing out the information and keeping it in a file that they will use to create their report. But instead of having them print everything as they go to each individual site they can copy and paste until later. When they finish their research they come back to their file, decide what information they want to use, and can print it out all at once. This has made it easier for me because the students turn this in with their report. So, I would say it not only allows students to learn goals of summarizing, interpreting, or synthesizing, it helps me to address them in greater depth and it’s easier on me! (April, middle school teacher)

I evaluated a WebQuest for middle elementary (third–fourth grades), although it seems a little complicated for that age group. The quest divides students into groups and each person in the group is given a role to play (a botanist, museum curator, ethnobotanist, etc.). The task is for students to find out how plants were used for medicinal purposes in the Southwest many years ago. Students then present their findings, in a format that they can give to a national museum. Weird. It was a little complicated and not well done. I liked the topic and thought it was interesting, but a lot of work would need to be done to modify it so that all students could participate. (Jennie, first-grade teacher).

CHAPTER REVIEW

Define problem-solving and inquiry.

The element that distinguishes problem-solving or problem-based learning from other strategies is that the focal point is a problem that students must work toward solving. A proposed solution is typically the outcome of problem-solving. During the inquiry part of the process, students ask questions and then search for answers to those questions.

Understand the interaction between problem-solving and other instructional goals. Although inquiry is also an important instructional strategy and can stand alone, it is also a central component of problem-solving because students must ask questions and investigate the answers to solve the problem. In addition, students apply critical and creative thinking skills to prior knowledge during the problem-solving process, and they communicate, collaborate, and often produce some kind of concrete artifact.

Discuss guidelines and tools for encouraging effective student problem-solving.

It is often difficult for teachers to not do what students can do, but empowering students in this way can lead to a string of benefits. Other guidelines, such as avoiding plagiarism, integrating reading and writing, and making it okay for students to make mistakes, keep the problem-solving process on track. Tools to assist in this process range from word processing to specially designed inquiry tools.

Create and adapt effective technology-enhanced tasks to support problem-solving. Teachers can design their own tasks following guidelines from any number of sources, but they can also find ready-made problems in books, on the Web, and in some software pack-ages. Teachers who do design their own have plenty of resources available to help. A key to task development is connecting classroom learning to the world outside of the classroom.

Assess student technology-supported problem-solving.

In many ways the assessment of problem-solving and inquiry tasks is similar to the assessment of other goals in this text. Matching goals and objectives to assessment and ensuring that students receive formative feedback throughout the process will make success more likely.

Baker, T. (2005). The history and application of GIS in education. KANGIS: K12 GIS Community. Available from http://kangis.org/learning/ed_docs/gisNed1.cfm.

Belland, B., Walker, A., Kim, N., & Lefler, M. (2017). Synthesizing results from empirical research on computer-based scaffolding in STEM education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), pp. 309-344.

Chauhan, S. (2017). A meta-analysis of the impact of technology on learning effectiveness of elementary students. Computers & Education, 105, pp. 14-30.

Dooly, M. (2005, March/April). The Internet and language teaching: A sure way to interculturality? ESL Magazine, 44, 8–10.

Gordon, R. (1998, January).Balancing real-world problems with real-world results. Phi Delta Kappan, 79(5), 390–393. [electronic version]

IMSA (2005). How does PBL compare with other instructional approaches? Available: http://www2 .imsa.edu/programs/pbln/tutorials/intro/intro7.php.

Molebash, P., & Dodge, B. (2003). Kickstarting inquiry with WebQuests and web inquiry projects. Social Education, 671(3), 158–162.

Verga, L., & Kotz, S. A. (2013). How relevant is social interaction in second language learning? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 550. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00550

Share This Book

Feedback/errata, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Increase Font Size

New Designs for School 5 Steps to Teaching Students a Problem-Solving Routine

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Students can use the 5 steps in this simple routine to solve problems across the curriculum and throughout their lives.

When I visited a fifth-grade class recently, the students were tackling the following problem:

If there are nine people in a room and every person shakes hands exactly once with each of the other people, how many handshakes will there be? How can you prove your answer is correct using a model or numerical explanation?

There were students on the rug modeling people with Unifix cubes. There were kids at one table vigorously shaking each other’s hand. There were kids at another table writing out a diagram with numbers. At yet another table, students were working on creating a numeric expression. What was common across this class was that all of the students were productively grappling around the problem.

On a different day, I was out at recess with a group of kindergarteners who got into an argument over a vigorous game of tag. Several kids were arguing about who should be “it.” Many of them insisted that they hadn’t been tagged. They all agreed that they had a problem. With the assistance of the teacher they walked through a process of identifying what they knew about the problem and how best to solve it. They grappled with this very real problem to come to a solution that all could agree upon.

Then just last week, I had the pleasure of watching a culminating showcase of learning for our 8th graders. They presented to their families about their project exploring the role that genetics plays in our society. Tackling the problem of how we should or should not regulate gene research and editing in the human population, students explored both the history and scientific concerns about genetics and the ethics of gene editing. Each student developed arguments about how we as a country should proceed in the burgeoning field of human genetics which they took to Capitol Hill to share with legislators. Through the process students read complex text to build their knowledge, identified the underlying issues and questions, and developed unique solutions to this very real problem.

Problem-solving is at the heart of each of these scenarios, and an essential set of skills our students need to develop. They need the abilities to think critically and solve challenging problems without a roadmap to solutions. At Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., we have found that one of the most powerful ways to build these skills in students is through the use of a common set of steps for problem-solving. These steps, when used regularly, become a flexible cognitive routine for students to apply to problems across the curriculum and their lives.

The Problem-Solving Routine

At Two Rivers, we use a fairly simple routine for problem solving that has five basic steps. The power of this structure is that it becomes a routine that students are able to use regularly across multiple contexts. The first three steps are implemented before problem-solving. Students use one step during problem-solving. Finally, they finish with a reflective step after problem-solving.

Problem Solving from Two Rivers Public Charter School

Before Problem-Solving: The KWI

The three steps before problem solving: we call them the K-W-I.

The “K” stands for “know” and requires students to identify what they already know about a problem. The goal in this step of the routine is two-fold. First, the student needs to analyze the problem and identify what is happening within the context of the problem. For example, in the math problem above students identify that they know there are nine people and each person must shake hands with each other person. Second, the student needs to activate their background knowledge about that context or other similar problems. In the case of the handshake problem, students may recognize that this seems like a situation in which they will need to add or multiply.

The “W” stands for “what” a student needs to find out to solve the problem. At this point in the routine the student always must identify the core question that is being asked in a problem or task. However, it may also include other questions that help a student access and understand a problem more deeply. For example, in addition to identifying that they need to determine how many handshakes in the math problem, students may also identify that they need to determine how many handshakes each individual person has or how to organize their work to make sure that they count the handshakes correctly.

The “I” stands for “ideas” and refers to ideas that a student brings to the table to solve a problem effectively. In this portion of the routine, students list the strategies that they will use to solve a problem. In the example from the math class, this step involved all of the different ways that students tackled the problem from Unifix cubes to creating mathematical expressions.

This KWI routine before problem solving sets students up to actively engage in solving problems by ensuring they understand the problem and have some ideas about where to start in solving the problem. Two remaining steps are equally important during and after problem solving.

The power of teaching students to use this routine is that they develop a habit of mind to analyze and tackle problems wherever they find them.

During Problem-Solving: The Metacognitive Moment

The step that occurs during problem solving is a metacognitive moment. We ask students to deliberately pause in their problem-solving and answer the following questions: “Is the path I’m on to solve the problem working?” and “What might I do to either stay on a productive path or readjust my approach to get on a productive path?” At this point in the process, students may hear from other students that have had a breakthrough or they may go back to their KWI to determine if they need to reconsider what they know about the problem. By naming explicitly to students that part of problem-solving is monitoring our thinking and process, we help them become more thoughtful problem solvers.

After Problem-Solving: Evaluating Solutions

As a final step, after students solve the problem, they evaluate both their solutions and the process that they used to arrive at those solutions. They look back to determine if their solution accurately solved the problem, and when time permits they also consider if their path to a solution was efficient and how it compares to other students’ solutions.

The power of teaching students to use this routine is that they develop a habit of mind to analyze and tackle problems wherever they find them. This empowers students to be the problem solvers that we know they can become.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About New Designs for School

Cultivating Equitable Learners: Why Pathway and Literacy Partners are Key to BPS Student’s Success

Nika Hollingsworth (she/her/hers)

June 5, 2024

NGLC Invites Applications from New England High School Teams for Our Fall 2024 Learning Excursion

March 21, 2024

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

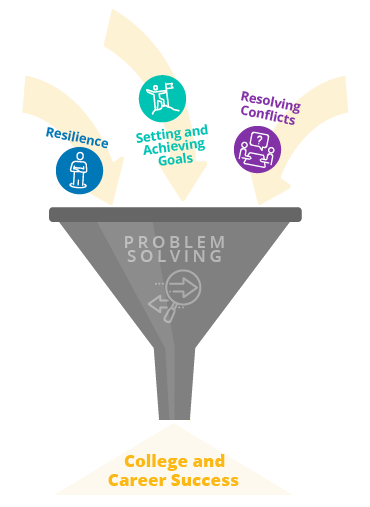

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- Problem Solving in STEM

Solving problems is a key component of many science, math, and engineering classes. If a goal of a class is for students to emerge with the ability to solve new kinds of problems or to use new problem-solving techniques, then students need numerous opportunities to develop the skills necessary to approach and answer different types of problems. Problem solving during section or class allows students to develop their confidence in these skills under your guidance, better preparing them to succeed on their homework and exams. This page offers advice about strategies for facilitating problem solving during class.

How do I decide which problems to cover in section or class?

In-class problem solving should reinforce the major concepts from the class and provide the opportunity for theoretical concepts to become more concrete. If students have a problem set for homework, then in-class problem solving should prepare students for the types of problems that they will see on their homework. You may wish to include some simpler problems both in the interest of time and to help students gain confidence, but it is ideal if the complexity of at least some of the in-class problems mirrors the level of difficulty of the homework. You may also want to ask your students ahead of time which skills or concepts they find confusing, and include some problems that are directly targeted to their concerns.

You have given your students a problem to solve in class. What are some strategies to work through it?