- General Information

- Tuition fees

Application & Admission

Language requirements, program features.

- List of Universities

2734 Study programs

Study Organic Chemistry in Germany: 11 Universities with 10 English Degree Programs

All important info for international students in germany (2024/2025).

Organic Chemistry is the study of carbon-containing compounds, delving into their structure, properties, and reactions. Students explore a wide array of topics including hydrocarbons, polymerization, and stereochemistry. This field is critical for understanding life at a molecular level and creating new materials. Those who study Organic Chemistry learn about synthesis strategies, reaction mechanisms, and analytical techniques to characterize organic substances. With its applications in pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and petrochemicals, a degree in Organic Chemistry opens doors to careers in research, drug development, quality control, and beyond, enabling breakthroughs that shape our health and environment.

Study Programs in English

Universities

Universities in International Rankings

€ 0 (10 programs for EU citizens, 9 programs for Non-EU citizens)

€ 1,500 per semester (10 programs for EU citizens, 1 program for Non-EU citizens)

Winter Semester

between July 15 and June 15

Summer Semester

between July 15 and April 30

Top-ranked German Universities in Organic Chemistry

public University

No. of Students: approx. 36,000 students

Program Fees: € 0 (per semester)

No. of Students: approx. 38,000 students

No. of Students: approx. 27,000 students

Tuition Fees

3 english degree programs for organic chemistry in germany.

Clausthal University of Technology Clausthal-Zellerfeld

Justus Liebig University Giessen Giessen

Sustainable chemistry.

Ulm University Ulm

Application Deadlines

Winter Semester 2024/2025

Summer Semester 2025

Winter Semester 2025/2026

Open Programs

10 programs

Application Modes

Application process.

Friedrich Schiller University Jena Jena

Biochemistry.

University of Göttingen Göttingen

Chemistry [english & german track].

Chemistry [English track]

TOEFL Scores

Cambridge Levels

5.5 (2 programs )

72 (2 programs )

B2 First (FCE) (2 programs )

7 (2 programs )

95 (2 programs )

Hochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg Rheinbach

Applied biology.

Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Mainz

Biomedical chemistry.

4-6 semesters

→ View all programs with online courses

Master of Science

Bachelor of Science

Winter intake

Summer intake

Winter & Summer intake

List of all German Universities offering English-taught Study Programs in Organic Chemistry

Clausthal University of Technology

Program Fees: € 0

M.Sc. (Master of Science)

Freie Universität Berlin

Friedrich Schiller University Jena

Hochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg

B.Sc. (Bachelor of Science)

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

← Prev page

Next Page →

News & Articles

Tuition-free Universities in Germany in English

Master's Requirements in Germany

Scholarships for international students (2024/25)

Uni-assist: A guide for international students (2024)

How Much Does it Cost to Live in Germany?

Germany in University Rankings

DAAD Scholarships: Guide

Engineering Universities in Germany: A Guide 2024/25

- Research Groups

- Prof. Hashmi

- Prof. Kivala

- Prof. Mastalerz

- Prof. Straub

- Prof. Helmchen

- Former Lecturers

- Administration

- Mass Spectrometry

- Microanalysis

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- X-Ray Facility

- Contact information

Institute of Organic Chemistry

|

| ||

| (Honorary Professor) | ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| of the Faculty |

100 Best universities for Organic Chemistry in Germany

Updated: February 29, 2024

- Art & Design

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Liberal Arts & Social Sciences

- Mathematics

Below is a list of best universities in Germany ranked based on their research performance in Organic Chemistry. A graph of 34.8M citations received by 1.16M academic papers made by 142 universities in Germany was used to calculate publications' ratings, which then were adjusted for release dates and added to final scores.

We don't distinguish between undergraduate and graduate programs nor do we adjust for current majors offered. You can find information about granted degrees on a university page but always double-check with the university website.

1. Technical University of Munich

For Organic Chemistry

2. Heidelberg University - Germany

3. University of Gottingen

4. University of Munich

5. University of Munster

6. RWTH Aachen University

7. Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

8. University of Erlangen Nuremberg

9. University of Freiburg

10. University of Stuttgart

11. Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

12. Free University of Berlin

13. University of Tubingen

14. Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main

15. University of Marburg

16. University of Wurzburg

17. University of Hamburg

18. University of Bonn

19. Technical University of Berlin

20. Ruhr University Bochum

21. Heinrich Heine University of Dusseldorf

22. Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg

23. Friedrich Schiller University of Jena

24. Dresden University of Technology

25. University of Regensburg

26. University of Bayreuth

27. University of Cologne

28. Kiel University

29. Humboldt University of Berlin

30. University of Ulm

31. University of Giessen

32. University of Leipzig

33. Saarland University

34. University of Konstanz

35. Braunschweig University of Technology

36. Leibniz University of Hanover

37. Darmstadt University of Technology

38. TU Dortmund University

39. Charite - Medical University of Berlin

40. University of Duisburg - Essen

41. Technical University of Kaiserslautern

42. University of Rostock

43. University of Bielefeld

44. University of Bremen

45. Hannover Medical School

46. University of Hohenheim

47. Chemnitz University of Technology

48. University of Potsdam

49. Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg

50. Clausthal University of Technology

51. University of Greifswald

52. Hamburg University of Technology

53. Otto von Guericke University of Magdeburg

54. University of Wuppertal

55. University of Paderborn

56. Osnabruck University

57. Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences

58. Freiberg University of Technology

59. University of Lubeck

60. University of Augsburg

61. University of Kassel

62. Aachen University of Applied Sciences

63. Jacobs University Bremen

64. University of Siegen

65. Ilmenau University of Technology

66. Folkwang University of the Arts

67. University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover

68. Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus - Senftenberg

69. Munich University of the Federal Armed Forces

70. Merseburg University of Applied Sciences

71. Munich University of Applied Sciences

72. Witten/Herdecke University

73. Mainz University of Applied Sciences

74. German Sport University Cologne

75. University of Mannheim

76. University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg

77. Weihenstephan-Triesdorf University of Applied Sciences

78. Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences

79. Leuphana University of Luneburg

80. University of Koblenz-Landau

81. University of Trier

82. Bauhaus - University Weimar

83. Munster University of Applied Sciences

84. University of Hagen

85. Mannheim University of Applied Sciences

86. Hamburg University of Applied Sciences

87. Berlin Technical University of Applied Sciences

88. University of Applied Sciences Wildau

89. Deggendorf Institute of Technology

90. TH Bingen University of Applied Sciences

91. Furtwangen University of Applied Sciences

92. Cologne University of Applied Sciences

93. Esslingen University of Applied Sciences

94. Hannover University of Applied Sciences

95. Bremen University of Applied Sciences

96. Reutlingen University

97. Berlin University of Applied Sciences

98. Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences

99. Offenburg University of Applied Sciences

100. Mittelhessen University of Applied Sciences

The best cities to study Organic Chemistry in Germany based on the number of universities and their ranks are Munich , Heidelberg , Gottingen , and Munster .

Chemistry subfields in Germany

- Zur Metanavigation

- Zur Hauptnavigation

- Zur Subnavigation

- Zum Seitenfuss

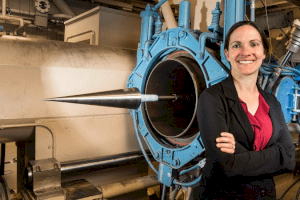

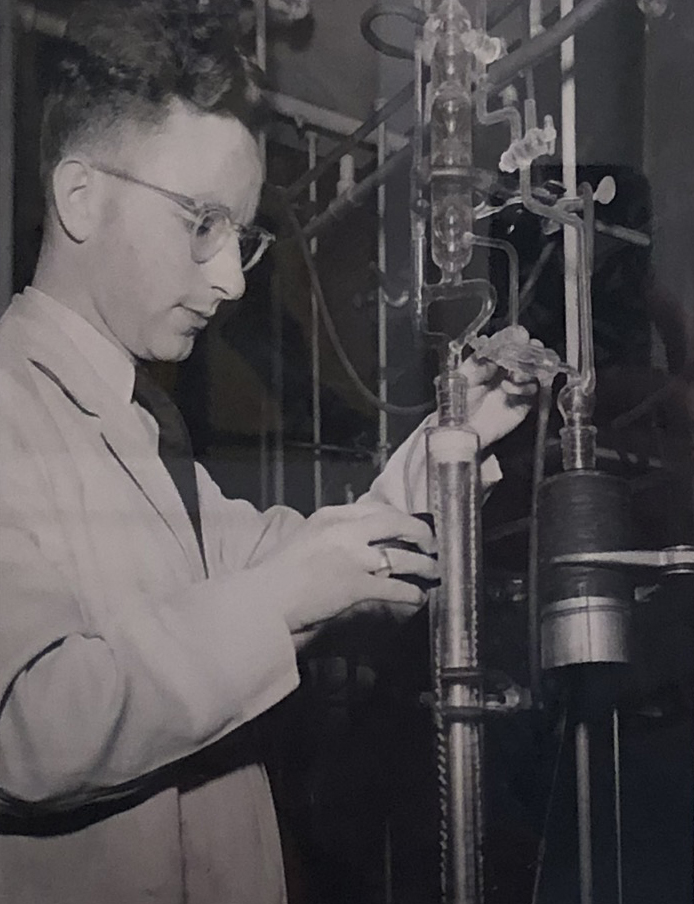

Photo: Gunnar Ehrlich

Institute of Organic Chemistry

These are the current research groups at the Institute of Organic Chemistry:

- Prof. Dr. Daria Berdnikova

- Prof. Dr. Ralph Holl

- Prof. Dr. Chris Meier ,

- Prof. Christian B. W. Stark

- Prof. Dr. Volkmar Vill

The research groups are supported by the NMR service directed by Dr. Thomas Hackl and the MS department directed by Dr. Jennifer Menzel . Dr. Brita Werner and Dr. Gunnar Ehrlich are charge of the basic education.

Technology transfer

How to find us, institute management.

Director: Prof. Dr. Ralph Holl Tel: +49 40 42838-2825 E-mail: ralph.holl "AT" uni-hamburg.de

Deputy: Prof. Dr. Chris Meier Tel.: +49 40 42838-4324 E-mail: chris.meier "AT" uni-hamburg.de

Secretary’s office

Tel: +49 40 42838-6218 E-mail: gd-oc.chemie "AT" uni-hamburg.de

Useful links

Academic services:.

- Department of Mass Spectrometry

- NMR Facility

- Chemical store

Practical modules:

- Dr. B. Werner / Basic practical module in organic chemistry

- Dr. G. Ehrlich / Practical module in organic chemistry (minor)

Organic Synthesis

Research in the Ritter group focuses on the development of novel reaction chemistry. We seek to discover molecular structure and reactivity that can contribute to interdisciplinary solutions for challenges in science. The lab focuses on synthetic organic and organometallic chemistry, complex molecule synthesis, and mechanistic studies to develop practical access to molecules of interest in catalysis, medicine, and materials.

Research Topics:

Late-stage functionalization, late-stage fluorination, unappreciated redox reactivity of palladium.

Safer alternative for an explosive reaction

The chemical industry has been using a reaction with explosive chemicals for over 100 years - now Mülheim scientists have discovered a safer alternative. more

Thiel Award 2024 goes to Philipp Hartmann

Philipp Hartmann, PhD candidate in the group of Prof. Tobias Ritter, has been awarded the Thiel Award. Each year the Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung honors a young talent in the field of chemistry with this prestigious prize. more

Thianthrenium chemistry allows for reactivity switch of a nucleophilic amino acid into a versatile intermediate

Ritter group publishes their findings with “Nature Chemistry” more

Teenagers experience extraordinary holidays

Local school students visit the institute for a whole week more

Minerva’s daughters: Optimistic for the future

Beatrice Lansbergen works as PhD student in the Department of Organic Synthesis more

Working in the radionuclide laboratory

Research report:.

- Research Report Ritter 2017-2019 523.46 kB

- Research Report Ritter 2014-2016 1.16 MB

Prospective and Current Students

Are you interested in one of our degree programs? Are you a student at TU Berlin looking for information? You can find extensive useful information about our degree programs, courses, introductory events, and mentoring program on our pages about studies and teaching. You can also find information about our offers for school students. We recommend regularly visiting our website to stay up to date.

Research at Our Institute

On our pages on research and transfer you can find exciting topics for your final thesis, doctorate, or post-doc project. You can also learn about our working groups and their areas of focus, opportunities to network with industry, and the benefits (and risks) of founding a start-up.

Sustainability and Green Chemistry

Our institute has a long tradition of conducting research into the development of sustainable chemical processes and syntheses of methods. There is no future without chemistry! The issues of sustainability and Green Chemistry also play a central role in our teaching. You’ll find here an overview of our activities in these areas.

Institute Infrastructure

Several central facilities and services form the heart of our institute. In addition to countless analytical centers, which offer special techniques for characterizing molecules and materials, we also have our own workshops and central IT infrastructure. In addition, we have a chemical and material storage facility and are responsible for the central disposal of hazardous waste.

News ticker

Girls' day at the tu berlin we were part of it.

On 25 April 2024, interested girls were able to get to know the Institute of Chemistry.

Prof. Dr. Matthias Drieß receives Reinhart Koselleck project: Innovative fixation and functionalisation of dinitrogen

1 million euros for Prof. Drieß' team on "Nitrogen fixation, (electro)reduction and functionalisation based on silicon systems"

Chemical Invention Factory to be Built on TU Berlin Charlottenburg Campus

Pre-seed center for green chemistry approved, construction to begin in 2025

We are sad to announce the passing of Prof. Dr. Dieter Ziessow (1940 – 2024)

The Institute of Chemistry at Technische Universität Berlin mourns the loss of Prof. Dr. Dieter Ziessow who passed away on February 28, 2024 at the age of 83.

We are sad to announce the passing of Prof. Dr. Jörn Müller (1936 – 2024)

The Technical University of Berlin has lost Professor Dr Jörn Müller, who worked at its Institute of Chemistry for decades.

Lecture Dr. Jan Michael Schuller (Department of Chemistry,...

Lecture prof. dr. vinh nguyen (university of new south....

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin - Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences - Department of Chemistry

Analytical and environmental chemistry.

- Micro & Nano Analytical Sciences: Kannan Balasubramanian

- Instrumental Analytical Chemistry: Ulrich Panne

- Bioanalytical Chemistry: Dietrich Volmer

Chemistry Education

- Empirical Analysis of Teaching/Learning Processes: Rüdiger Tiemann

General and Inorganic Chemistry

- Organometallic Chemistry and Homogeneous Catalysis: Thomas Braun

- Coordination Chemistry / Catalysis: Christian Limberg

- Functional Materials: Nicola Pinna

- Inorganic Reaction Mechanism and Spectroscopy (Heisenberg Professor): Kallol Ray

Organic and Bioorganic Chemistry

- Bioorganic Chemistry: Christoph Arenz

- Organic Synthesis of Functional Systems: Hans Börner

- Chemical Biology I: Dorothea Fiedler

- Chemical Biology II: Christian Hackenberger

- Organic Chemistry and Functional Materials: Stefan Hecht

- Bioorganic Synthesis: Oliver Seitz

Physical Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry of Materials / Electrochemistry: Philipp Adelhelm

- Nanoscale Optical Spectroscopy: Janina Kneipp

- Hybrid Devices: Emil List-Kratochvil

- Nanostructured Materials: Klaus Rademann

- Ultrafast Spectroscopy: Julia Stähler

- Hybrid Materials - Forming and Scaling: Eva Unger

Theoretical Chemistry

- Molecular Quantum Chemistry: Michael Römelt

- Solid-State Quantum Chemistry / Catalysis: Joachim Sauer

INTEGRATED RESEARCH GROUPS

Analytical chemistry .

- Structural and Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy: André Dallmann

- Activation of small molecules with main group and transition metal compounds: Josh Abbenseth

- Organometallic and Fluorine Chemistry Alberto Pérez-Bitrián

- Cluster Chemistry Yu Wang

- Functional Nanomaterials: Michael Bojdys

- Synthesis of Supramolecular Materials: Oliver Dumele

- Molecular Machines: Michael Kathan

- Molecular Nanoparticles: Wolfgang Christen

- Electrochemical and Thermal Energy Storage: Gustav Graeber

HU on the internet

- Humboldt University on Facebook

- Die Humboldt-Universität bei BlueSky

- Humboldt University on Instagram

- Humboldt University on YouTube

- Humboldt University on LinkedIn

- RSS-Feeds of the Humboldt University

- Humboldt University on Twitter

We have 9 Chemistry PhD Projects, Programmes & Scholarships in Germany

Institution

All Institutions

All PhD Types

All Funding

Chemistry PhD Projects, Programmes & Scholarships in Germany

Research assistant (m/f/d) (salary grade e 13 tv-l, 65%), phd research project.

PhD Research Projects are advertised opportunities to examine a pre-defined topic or answer a stated research question. Some projects may also provide scope for you to propose your own ideas and approaches.

Funded PhD Project (Students Worldwide)

This project has funding attached, subject to eligibility criteria. Applications for the project are welcome from all suitably qualified candidates, but its funding may be restricted to a limited set of nationalities. You should check the project and department details for more information.

PhD Position / Research Assistent (f/m/d) on Development and characterization of a reaction device for NMR measurements under harsh process conditions

Phd student (f/m/d) center for optogenetic therapies, materials for the detection of minority species in optofluidic waveguides, funded phd project (european/uk students only).

This project has funding attached for UK and EU students, though the amount may depend on your nationality. Non-EU students may still be able to apply for the project provided they can find separate funding. You should check the project and department details for more information.

Responsive biomaterials based on biogenic resources

Material investigation of living biogenic hydrogels towards artificial biofilms, 1 phd student position: new concepts in electrocatalysis and energy storage, phd student positions at international max planck research school for molecules of life, munich, funded phd programme (students worldwide).

Some or all of the PhD opportunities in this programme have funding attached. Applications for this programme are welcome from suitably qualified candidates worldwide. Funding may only be available to a limited set of nationalities and you should read the full programme details for further information.

Germany PhD Programme

A German PhD usually takes 3-4 years. Traditional programmes focus on independent research, but more structured PhDs involve additional training units (worth 180-240 ECTS credits) as well as placement opportunities. Both options require you to produce a thesis and present it for examination. Many programmes are delivered in English.

Max Planck Research Programme

Max Planck Research Programmes are structured PhD opportunities set up by the Max Planck Society, an independent non-profit German research organisation. Max Planck Institutes and universities collaborate to offer interdisciplinary and international PhD opportunities providing high standards of training and support as well as generous funding.

FindAPhD. Copyright 2005-2024 All rights reserved.

Unknown ( change )

Have you got time to answer some quick questions about PhD study?

Select your nearest city

You haven’t completed your profile yet. To get the most out of FindAPhD, finish your profile and receive these benefits:

- Monthly chance to win one of ten £10 Amazon vouchers ; winners will be notified every month.*

- The latest PhD projects delivered straight to your inbox

- Access to our £6,000 scholarship competition

- Weekly newsletter with funding opportunities, research proposal tips and much more

- Early access to our physical and virtual postgraduate study fairs

Or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

or begin browsing FindAPhD.com

*Offer only available for the duration of your active subscription, and subject to change. You MUST claim your prize within 72 hours, if not we will redraw.

Do you want hassle-free information and advice?

Create your FindAPhD account and sign up to our newsletter:

- Find out about funding opportunities and application tips

- Receive weekly advice, student stories and the latest PhD news

- Hear about our upcoming study fairs

- Save your favourite projects, track enquiries and get personalised subject updates

Create your account

Looking to list your PhD opportunities? Log in here .

Filtering Results

By using the Google™ Search you agree to Google's privacy policy

Open Positions

The Obenchain research group, in the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the University of Göttingen seeks applications for one PhD position (all genders welcome) (65 % E13 TV-L, limited contract of 3 years, earliest starting date April 1, 2024). In this project, the PhD candidate will focus on understanding the structure and dynamics of weakly bound complexes containing molecular hydrogen. The experiments will make use of a combination of different methods, including chirped-pulse microwave spectroscopy and cavity-type microwave spectroscopy. The experiments will be benchmarked with quantum chemical calculations. The project is associated with the Research Training Group BENCh (Benchmark experiments for numerical quantum chemistry, https://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/587836.html ), which offers unique training for PhD students as well as the group support from the larger project. Required qualifications: • You hold (or are in the process of concluding) a Master's degree in Chemistry. • You have previous experience in gas-phase spectroscopy. • You have an interest in weakly bound complexes. • You are proficient in English and/or in German. • You enjoy working in a team. Further qualifications of superior candidates would include: • Experience in gas-phase rotational spectroscopy. • Experience in running computational calculations (DFT, ab initio) and comparing between theoretical and experimental results in a rigorous manor. Project goals include: • Testing the viability in measuring H2 complexes in the gas-phase by the H¬2 frequency shift in cooperation with the projects of the current working group. • Measuring pure rotational spectra of H2 complexes with halogen containing molecules and aromatic molecules. • Rigorous benchmarking of experimental results against high-level computational methods. Please send your application documents (CV, motivation letter, academic certificates/transcripts thereof, publication list, 2 references, and proof of language proficiency all combined in a single pdf document) to Prof. Daniel Obenchain ( [email protected] ) by February 15, 2024. Please put the subject as “PhD Application H2 Complexes” in the subject line. The Obenchain group is a welcoming to all diverse peoples. The University of Göttingen is an equal opportunities employer and places particular emphasis on fostering career opportunities for women. Qualified women are therefore strongly encouraged to apply in fields in which they are underrepresented. The university has committed itself to being a family-friendly institution and supports their employees in balancing work and family life. The mission of the University is to employ a greater number of severely disabled persons. Applications from severely disabled persons with equivalent qualifications will be given preference.

- Crimson Careers

- For Employers

- Harvard College

- Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts & Sciences

- Harvard Extension School

- Premed / Pre-Health

- Families & Supporters

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- First Generation / Low Income

- International Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Undocumented Students

- Explore Interests & Make Career Decisions

- Create a Resume/CV or Cover Letter

- Expand Your Network

- Engage with Employers

- Search for a Job

- Find an Internship

- January Experiences (College)

- Find & Apply for Summer Opportunities Funding

- Prepare for an Interview

- Negotiate an Offer

- Apply to Graduate or Professional School

- Access Resources

- AI for Professional Development and Exploration

- Arts & Entertainment

- Business & Entrepreneurship

- Climate, Sustainability, Environment, Energy

- Government, Int’l Relations, Education, Law, Nonprofits

- Life Sciences & Health

- Technology & Engineering

- Still Exploring

- Talk to an Advisor

Technische Universität Braunschweig

Postdoc in organic chemistry and natural products.

- Share This: Share Postdoc in Organic Chemistry and Natural Products on Facebook Share Postdoc in Organic Chemistry and Natural Products on LinkedIn Share Postdoc in Organic Chemistry and Natural Products on X

With more than 16,000 students and 3,800 employees, the Technische Universität Braunschweig is one of Germany´s leading institutes of technology. It stands for strategic and performance-oriented thinking and acting, relevant research, committed teaching, and the successful transfer of knowledge and technologies to the economy and society. We consistently advocate for family friendliness and equal opportunities.

Our research focuses are mobility, engineering for health, metrology, and city of the future. Strong engineering and natural sciences are our core disciplines. These are closely interconnected with economics, social and educational sciences and humanities.

Our campus is located in the midst of one of the most research-intensive regions in Europe. We work successfully together with over 20 research institutions in our neighborhood as we do with our international partner universities.

Starting from August 15, the Institute of Organic Chemistry is looking for a

Postdoc (m/f/d) in the field of Organic Chemistry and Natural Products (EG 13 TV-L, full-time)

The position is to be filled on a fixed-term basis for a period of 2 years, non-extendable. The successful applicant will be given the opportunity for further scientific qualification.

Our research group is interested in the Chemistry of communication of various organisms ranging from butterflies to bacteria. We identify volatile and semi-volatile secondary metabolites from limited amounts of material, using GC/MS, GC/IR, and other methods. Proposed structures have to be verified by synthesis. Research is done in cooperation with biologists. The project aims at the identification and synthesis of volatiles from various sources. Therefore, the candidate has to perform both total synthesis and organic trace analysis, as well as microbial fermentation. An interest in biological questions is a prerequisite. The project is funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG) and will be performed in close cooperation with partners. Our research can be found here: www.oc.tu-bs.de/schulz/index_en.html

- You will carry out research in the area of Natural Product synthesis and analytics.

- You will publish research findings and participate in conferences.

- You will be involved in teaching at the University (supervision of students’ work).

- Work on exciting future-oriented research topics in an inspiring work environment as part of the university community

- A vibrant campus life in an international atmosphere with lots of intercultural offers and international cooperation

- Pay in accordance with the collective agreement EG13 TV-L (a special payment at the end of the year as well as a supplementary benefit in the form of a company pension, comparable to a company pension in the private sector) including 30 days’ vacation per year

- Flexible working hours and a family-friendly university culture, awarded the “Family-friendly university” audit since 2007

- Special continuing education programs for young scientists, a postdoc program, as well as other offerings from the Central Personnel Development Department and sports activities.

Further notes We welcome applicants of all nationalities. At the same time, we encourage people with severe disabilities to apply. Applications from severely disabled persons will be given preference if they are equally qualified. Please attach a proof of disability to your application. We are also working on the fulfilment of the Central Equality Plan based on the Lower Saxony Equal Rights Act (Niedersächsisches Gleichberechtigungsgesetz—NGG) and strive to reduce under-representation in all areas and positions as defined by the NGG. Therefore, applications from women are particularly welcome in this case.

The personal data will be stored for the purpose of processing the application. By submitting your application, you agree that your data may be stored and processed electronically for application purposes in compliance with the provisions of data protection law. Further information on data protection can be found in our data protection regulations at www.tu-braunschweig.de/datenschutzerklaerung-bewerbungen . Application costs cannot be reimbursed.

Questions and Answers For more information, please send an email to [email protected]

Deadline for applications is July 31th

Are you interested? Please send your application preferably via email to [email protected]

Please send only one PDF file including all necessary forms (letter, final grade certificates, curriculum vitae, PhD certificate, publications, two recommendation letters, …).

Prof. Dr. Stefan Schulz Institut für Organische Chemie TU Braunschweig Hagenring 30 38106 Braunschweig Germany

- Postdoc India

- Postdoc Abroad

- Postdoc (SS)

- RESEARCHERSJOB

- Post a position

- JRF/SRF/Project

- Science News

Postdoctoral: Organic Chemistry and Catalysis, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Postdoctoral: Organic Chemistry and Catalysis: The University of Amsterdam’s Organic Chemistry Group (SOC) at the Van ‘t Hoff Institute for Molecular Sciences (HIMS) invites applications for a postdoctoral researcher to collaborate on the project “C-H Methylation for late-stage drug discovery” in partnership with AstraZeneca.

Postdoctoral Position in Organic Chemistry and Catalysis

Designation: Postdoctoral Researcher Research Area: Organic Chemistry and Catalysis Location: University of Amsterdam, Science Park, Amsterdam, Netherlands Closing Date: August 1, 2024

Eligibility/Qualification:

- PhD degree in organic chemistry and catalysis .

- Background in organic synthesis and catalysis, particularly in metal-catalyzed C-H functionalization processes.

- Strong communication skills in English (written and spoken).

- Ability to work effectively in an international and collaborative research environment.

Job Description: The postdoctoral researcher will work within the SOC group at HIMS, collaborating closely with AstraZeneca. The project aims to develop general C-H methylation reactions to enhance the biological potency of lead compounds. Responsibilities include conducting research experiments, data analysis, presenting findings at conferences, and contributing to collaborative research efforts.

How to Apply: Interested candidates are invited to apply online by August 1st with the following documents in PDF format:

- Curriculum vitae, including a list of publications.

- Letter of motivation (max 1 page).

- Contact information (email, phone number) for the direct supervisor in the previous academic position.

Benefits and Terms: The position offers a temporary contract for 38 hours per week, initially for 12 months with the possibility of extension based on performance and funding availability. Salary ranges from € 3,226 to € 5,090 per month (scale 10), excluding allowances. Additional benefits include 232 holiday hours per year, professional development opportunities, and various secondary employment benefits.

About us: The University of Amsterdam is renowned for its research excellence and offers a stimulating academic environment at Science Park. HIMS conducts internationally recognized research in molecular sciences, collaborating closely with industry partners.

Contact: For further information or inquiries about the position, please contact: Tati Fernandez Ibanez, Associate Professor Email: [email protected]

The University of Amsterdam is committed to diversity and encourages applications from all qualified individuals. We look forward to receiving your application.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Postdoctoral associate in cell envelope, university of oxford, uk, postdoctoral research scientist (signalling), babraham institute, uk, postdoctoral position in medicinal chemistry, iit, genova, italy, postdoctoral researcher in evolutionary biology, university of jyväskylä, finland, postdoctoral researcher in microbiology/immunology, washington university, usa, postdoctoral scientist – medicinal chemistry, university of oxford, uk, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Follow us on Instagram @researchersjob_rj

- Terms Of Service

- Privacy Policy

LJMU-VC PhD Studentship Opportunity 2025, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

- Posted on: 19 June 2024

Postdoctoral Researcher at the Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Ljubljana; Slovenia

Job information, offer description.

The Košmrlj Lab ( https://www.kosmrlj-group.com/ ) at the Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Technology (FCCT) is mainly focused on organic chemistry and the development of new catalysts. We seek a highly motivated postdoctoral research fellow to join our collaborative team working on the immobilization of catalysts within continuous flow systems (project J7-50041 “ ImCatD ” funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency). The successful candidate will work closely with the MicroProcess Engineering Group ( https://chemeng.fkkt.uni-lj.si/ ) as well as collaborators around Europe (U.K., Sweden, Germany) and in the U.S.

This is a full-time, 1-year position (with a possibility of extension) located in our research institute (Chair of Organic Chemistry) in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Where to apply

Requirements.

- A degree in Organic or Polymer Chemistry or related field (Ph.D.).

- A keen interest in and knowledge of organic and polymer chemistry, and a strong background in synthetic chemistry, to enable the delivery of immobilized catalysts for flow systems.

- Experience with characterization of organic molecules and macromolecules (e.g., using TLC, 1D and 2D NMR, FTIR, mass spec, GPC).

- Able to work independently as well as in a collaborative team environment.

- Excellent organizational and prioritization skills. Strong attention to detail.

- Excellent communication and presentation skills.

- Evidence of consistent scientific innovation. Proven track record of publications in peer reviewed journals.

- Highly motivated to advance in his/her career.

- Willingness to contribute to the writing of grant proposals.

Additional Information

International work environment

Parking at the building

Cafeteria at the building

Chemistry Researcher Duties

- Carry out synthetic work (polymers/dendrimers/small molecules) and the associated purification and characterization of desired intermediates and final products.

- Analyse and interpret experimental data.

- Prepare reports on research findings and give presentations on these results at group meetings. Write up results in manuscript form for publication in leading journals.

- Assist with the maintenance of laboratory equipment, removal of chemical waste, and the procurement of chemicals and consumables.

Suitable candidates will be invited to live or online interview

More information about the work:

Work Location(s)

Share this page.

- Apply to UMaine

Organic Chemistry Instructor of Record at UMaine Farmington 2024-2025 (Hybrid)

The University of Maine at Farmington seeks a current UMaine graduate student to serve as the Instructor of Record for CHY 241 Organic Chemistry I during Fall 2024 and/or CHY 242 Organic Chemistry II during Spring 2025. In Fall 2024, the instructor will deliver three weekly lectures MWF 11-11:50 am, either in person or on Zoom (according to the instructor’s preference), and facilitate a lab that meets in person in Farmington on Tuesdays from 12:30-3:15 pm. The timing of lectures and lab for the Spring 2025 semester can be determined in consultation with the instructor.

Essential Duties

Skills and qualifications, compensation and benefits.

This is a 5-month (1-semester) or 10-month (2-semester) position, requiring a commitment of 20 hours per week. The appointment carries a monthly stipend of $2,222.25/month for a doctoral student or $1,888.89 for a master’s degree student, plus a tuition waiver for up to 9 graduate credits per semester and coverage of 100% of the graduate student health insurance premium. Free on-campus (dormitory) housing at UMF will be available to the instructor during this assistantship, due to the required in-person labs on Tuesdays.

Additional Details

This is not a federal work-study position. International graduate students are eligible to apply. Applicants must be admitted to a UMaine master’s or doctoral degree program and enrolled full-time.

How to Apply

Interested applicants should submit a cover letter, resume, and contact information for two references via an email jointly addressed to Chris Magri ([email protected]) , Chair of the Division of Science, Psychology, and Mathematics at UMaine Farmington; Jen Swalec ( [email protected] ); and your graduate advisor . Review of applications will begin on July 15 and will continue until the positions for both semesters have been filled.

College of Liberal Arts & Sciences

Department of Chemistry

- Undergraduate

- Meet Our Undergraduates

- Meet Our Graduate Students

- Why Study Chemistry

- Student Financial Aid

- Undergraduate Application

- Graduate Application

- Visit Illinois

- Undergraduate Studies

- General Chemistry

- Graduate Studies

- Bylaws & Policy Manual

- Chemistry Learning Center

- Course Listing

- SCS Academic Advising Office

- Research Overview

- Analytical Chemistry

- Chemical Biology

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Research Concentrations

- Undergraduate Research

- Annual Report

- Chemistry Master Calendar

- E-newsletter

- Public Engagement and Outreach

- Sesquicentennial Archives

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Student Organizations

- Illini Chemists

- In Memoriam

- Merchandise

- Nobel Prize Winners

- Teachers Ranked as Excellent by their Students

- Graduate Diversity and Program Climate

- Climate and Diversity Action Plan

- Community Values & Expectations

- Initiatives

- Organizations

- Alumni News

- Alumni Resources

- Donate to Chemistry

Chemistry students receive 2023 ACS Undergraduate Awards in organic, inorganic, and physical chemistry

A May 2023 graduate of the Department of Chemistry with a B.S. in Specialized Chemistry and an undergraduate researcher in Professor Liviu MIrica's group, Garvey has been awarded the ACS Division of Inorganic Chemistry Undergraduate Award in Inorganic Chemistry for the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Garvey also received the John C. Bailar Award for excellence in undergraduate research. In the Mirica lab, Garvey worked primarily on the synthesis and characterization of a new bidentate pyridinophane ligand, followed by a slew of para substituted derivatives. These ligands were then used to make novel low-valent Nickel complexes, which could have promising reactivity and applications in catalysis. Garvey presented his research at the 2022 Chemistry Summer Undergraduate Poster Session on the UIUC campus. Garvey will be p ursuing a PhD in chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in Shannon Stahl’s lab, where Garvey will start research this summer.

Morgan Kennebeck

A May 2023 graduate of the Department of Chemistry with a B.S. in Specialized Chemistry and an undergraduate researcher in Professor Scott Silverman's group, Kennebeck has been awarded the 2023 American Chemical Society Division of Organic Chemistry's Undergraduate Award in Organic Chemistry for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

This award recognizes senior students who display a significant aptitude in the field. In her nearly four years of undergraduate research in the Silverman laboratory, Kennebeck studied DNAzymes that modify oligonucleotides. With her research accomplishments, she is first author on one forthcoming manuscript and second author on another manuscript.

Kennebeck is the outgoing vice president of the UIUC campus ACS student chapter, and she was a teaching assistant and peer mentor for the First Semester Success in Chemistry freshman course. At the May 14, 2023, Chemistry Convocation ceremony, Kennebeck received the Reynold C. Fuson award for excellence in undergraduate research. In the fall, Kennebeck will be attending the University of California Berkeley to earn her PhD in chemistry.

Aidan Lindsay

A sophomore in the Department of Chemistry and an undergraduate researcher in Professor Prashant Jain's group, Lindsay has been awarded the 2023 American Chemical Society’s Undergraduate Award in Physical Chemistry for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The ACS Division of Physical Chemistry started the undergraduate award in 2017 to recognize and honor talented young physical chemists across the country. Awardees are chosen for their demonstrated excellence in physical chemistry and related fields based on research, coursework, and a commitment to a career in chemistry.

In the Jain laboratory, Lindsay has been studying the electronic properties of oxygen-deficient oxide-based photocatalysts by optical spectroscopy and electronic structure simulations. For his academic accomplishments, Aidan has received several accolades including most recently a Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship . Aidan aspires to pursue graduate studies in preparation of a research career in computational materials science.

Ippolitti Shares in Horizon Prize

Written by Staff

July 1, 2024

Francesca Ippoliti, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, is one of the recipients of the 2024 Organic Chemistry Horizon Prize: Perkin Prize in Physical Organic Chemistry from the Royal Society of Chemistry. The prize was awarded to the team for the creative advancement of strained intermediates involving cumulated cyclic dienes and trienes, research that Dr. Ippoliti worked on during graduate school. Horizon Prizes are international awards that recognize teams for their exceptional achievements in advancing the chemical sciences.

1536 Hewitt Ave

Saint Paul, MN 55104

General Information

Undergraduate Admission

Public Safety Office

Graduate Admission

ITS Central Service Desk

© 2024 Hamline University

In association with Mitchell | Hamline School of Law ®. Mitchell Hamline School of Law ® has more graduate enrollment options than any other law school in the nation.

- On-Campus Transfer

- Online Degree Completion

- International

- Admitted Students

- How to Apply

- Grants & Scholarships

- First-Year and Transfer Aid

- Online Degree Completion Aid

- Graduate Aid

- International Aid

- Military & Veteran Aid

- Undergraduate Tuition

- Online Degree Completion Tuition

- Graduate Tuition

- Housing & Food Costs

- Net Price Calculator

- Payment Info

- Undergraduate

- Continuing Education

- Program Finder

- Faculty by Program

- College of Liberal Arts

- School of Business

- School of Education & Leadership

- Mitchell Hamline School of Law

- Academic Bulletin

- Academic Calendars

- Bush Library

- Registration & Records

- Study Away & Study Abroad

- Housing & Dining

- Counseling & Health

- Service, Spiritual Life, & Recreation

- Activities & Organizations

- Diversity Resources

- Arts at Hamline

- Meet Our Students

- The Neighborhood

- The Hamline Academic Experience

- Student Research Opportunities

- Paid Internships

- Career Development Center

- Alumni Success Stories

- Center for Academic Success & Achievement

- Writing Center

- Why Hamline?

- Mission & History

- Fast Facts and Rankings

- University Leadership

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Alumni and Donors

- Request Info

Texas Tech Now

Rise and shine.

July 1, 2024

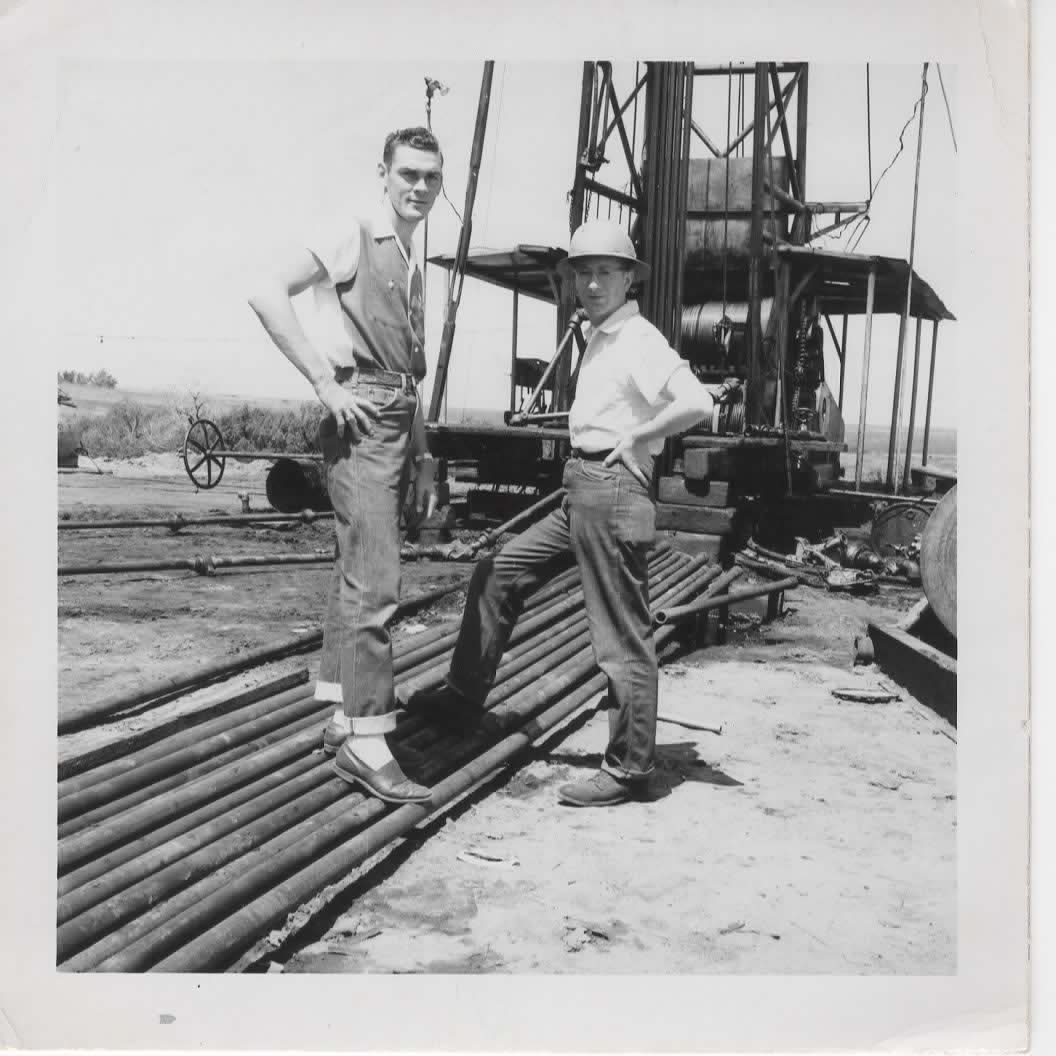

Young Henry Shine knew nothing of higher education. A century later he reflected on how it became his life.

This article originally appeared on Texas Tech Today in Feb. 2023 as a celebration of Henry Shine's 100th birthday. Shine passed away in June 2024, but his impact will be felt at Texas Tech for generations to come.

If you don't know the name Henry J. Shine , you're not alone.

“The university, as a whole, is unaware that I exist,” Shine says, matter-of-factly. “The president of the university is well aware, and the provost and the dean and the department, and the Southwest Collection, but as for the rest of the university, I probably don't exist. That's the way of life.”

It doesn't particularly concern him. After all, the 100-year-old has been retired from Texas Tech University for longer than most undergraduate students have been alive. But even so, his contributions during his 44 years at the university – as well as those in the 25 years since – are undoubtedly worth remembering.

You see, Shine came to higher education in a most unlikely way, arrived at Texas Tech by chance and made it his home. He made discoveries that put Texas Tech, his students and himself on the map; for that work, he was named one of the earliest Horn Professors at the university. He played important roles in some of the university's biggest turning points of the last half-century. And now, even decades after stepping away from the classroom, Shine is still helping future generations of scientists follow in his footsteps.

So, Red Raiders, here is your long-overdue reintroduction to Henry Shine.

A Stranger to Education

Texas Technological College was founded on Feb. 10, 1923. On the other side of the globe, Shine was already a month old.

Born in January 1923 in London's predominantly Jewish East End, Shine was one of four children in a decidedly working-class family. They lived in a tenement-style row house, and he attended Stepney Jewish Boys School.

At the time, it was customary for children to take an examination at age 11 to determine their educational future. Students who scored well continued into central and possibly even secondary school; students who did not left education at age 14 to start working. Shine performed well enough to earn a place in central school.

At age 13, he and his family moved to London's West End, a more sophisticated area near the theater district. He enrolled at Lyulph Stanley Central School, where he learned to work with his hands, probably training for low-level technical positions. However, a particularly wise teacher there, Mr. Taylor, saw more potential in Shine and a few other students.

He singled out five to teach privately with a tougher curriculum. Shine ruefully gave up metalworking and woodworking – two of his favorite classes – to instead study mathematics, German, chemistry and physics.

He was probably well on his way to a future in higher education – except that he was totally unaware of that path. With his blue-collar background, Shine didn't know anything about college; to him, Oxford and Cambridge was an annual boat race on the River Thames. His life experiences to that point had shown him only one option: working to earn a living. And, as a 15-year-old, he had already passed the age at which he should have started working. So, in 1938, Shine left school.

An Unlikely Route

Using his mathematical prowess and fluency in German, Shine became a bookkeeping clerk, first for a Romanian company that dealt in imports and exports and, later, for the Warner Bros. and First National film studios. He spent hours upon hours calculating long columns of numbers to determine the amount of rental money theaters owed to the film studios. He added up the pence and divided by 12 to convert to shillings, added the shillings and divided by 20 to convert to pounds – all without a calculator.

Then, on Sept. 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain declared war against Germany, effectively beginning World War II. That very day, Shine's family moved to what they thought would be a safer location: a peaceful suburb 17 miles upriver, Sunbury-on-Thames. He commuted in and out of the city each workday until the German bombings of London caused Warner Bros. to flee to the outskirts as well.

However, when the bombings became so commonplace they lost their ability to terrorize the Britons, Warner Bros. moved back to London. Unwilling to go back to commuting, Shine instead went to the Labor Exchange to seek a new job. There he learned about an opening for a routine analytical chemist – a low-level chemistry job he was ideally situated for because of his training at Lyulph Stanley.

So, he went to work for Maclean's, a pharmaceutical company that made toothpaste, analyzing the raw materials going into toothpaste and cosmetics. That led him into a similar position with the Pears soapmaking company, assessing the amounts of fatty acids in their products.

“It was nothing great in the way of chemistry,” Shine noted, “but I just loved that work.”

In those labs, he encountered other young chemists who were taking classes at night toward an Intermediate B.Sc. Certificate, essentially the first half of a bachelor's degree in chemistry. His curiosity piqued, and still completely unaware the program was part of a college curriculum, Shine enrolled.

Working days and taking classes at night, he progressed toward the exams that culminated the certificate program. Then, in January 1941, he turned 18 and his draft notice arrived in the mail.

So close to achieving his goal, Shine applied for a deferment of six months, hoping he could finish the program before joining the army. In response, he was summoned to the University of London Senate House. A group of fearsome-looking men dressed in suits sat around a huge, oval table. Why, they asked, did he want to delay his service to his country?

When he explained the situation, they caught him completely off guard. They allowed him the desired six months to finish the certificate on one condition: that he would go to the university an additional two years to finish a bachelor's degree.

“I was astonished,” he recalled. “I didn't know what ‘going to the university' meant. It meant, in fact, leaving work and going to a university, of which I was quite unaware.

“But I did it.”

Finding a Job

He was accepted into the highly regarded chemistry department at University College, part of the University of London system, and began classes in 1942. The college, however, was not in London at the time. Because of the bombings, it had been relocated to the University College of Wales campus in the seaside resort town of Aberystwyth on the coast of Wales.

Unlike college curriculums in the U.S., under the British university system, students take courses only related to their degree area. So, Shine's program didn't include humanities or language courses – he took only chemistry and physics, and he excelled in them. In 1944, he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in chemistry and physics with first-class honors.

Then, true to his word, he went back to the draft board. When he thanked them for the time and said it was now his turn to join up, they surprised him yet again.

“No,” they said. “We did not allow you to go to the university and get a first-class degree in chemistry to serve in the army. We want you to find a job in chemistry.”

There was a likely explanation.

“In World War I, the first people to volunteer for the army were the university people, and they were wiped out,” Shine explained. “So, Great Britain did not want to wipe out another generation of scientists.”

Whatever the reason for their order, Shine did as he was told.

He had been offered a position doing research at University College with Christopher Ingold and Edward Hughes, two of the most famous organic chemists in the world. But, thinking he needed to get to work and earn a living, he turned them down.

He also turned down an offer from a company called Tube Alloys after visiting their site and deciding he didn't like it. He later found out Tube Alloys was a cover name for the British efforts in atomic energy.

Instead, he found a job studying lubricating oils in the labs of Shell Oil Company in the nearby town of Hook. He was thoroughly bored and, within six months, went back to Ingold and Hughes to see if the research position was still available.

It was not. But, they said, Professor E.E. Turner needed a research assistant for a wartime project he was working on. After discussing the project, Turner offered Shine the position, and Shine joined him at Bedford College for Women, situated in London's beautiful Regent's Park. Shine turned his research work into a doctorate in 1947.

“I had noticed that, with a particular reaction I was employing, the Grignard reaction, strange things would happen on certain occasions, and I wanted to find out why that was,” Shine said. “So, that's what I did for three years at Bedford College. I never did find out what happened, but it led me to the U.S.”

Coming to America

After earning his doctorate, Shine wanted to continue his investigation of the Grignard reaction, so he applied to conduct postdoctoral research with Frank Whitmore at Penn State University, a leader in organometallic chemistry whose work Shine had read frequently. But after learning of Whitmore's death a month later, Shine applied instead to another well-known researcher, Henry Gilman at Iowa State College in Ames, Iowa.

Gilman later became known as the father of organometallic chemistry.

“He welcomed me to come and do research there, and he was going to pay my way as a research fellow,” Shine said. “And that's how I got to America.”

Shine arrived in January 1948, while Gilman was away having retinal surgery. When Gilman returned, he was partly blind.

“He asked me, as a postdoctoral fellow, to look after his organic graduate student labs,” Shine recalled. “He had 20 students, and this was my first training in how to listen to and respond to graduate students.”

But Shine soon realized checking on and advising 20 graduate students, and then reporting back to Gilman at his home every night, left precious little time to conduct research.

“I found that so burdensome, so time-consuming, that I couldn't do any work,” he said.

Although Gilman reluctantly agreed when Shine told him he could no longer oversee the graduate students, Shine still found himself taking care of things in Gilman's absence, even cleaning out cupboards under the benches in the research labs that were cluttered with bottles of chemicals and old-fashioned non-tapered glassware. Eventually, it came to a head.

“I couldn't do the research I wanted to do and look after Gilman's interests, so we parted,” Shine said. “He told me to go back to England; he was through with me.”

The head of the department, however, was not in agreement – especially after the only other organic chemist in the department, George Hammond, vouched for Shine. Shine agreed to teach one organic quiz section in exchange for full control of his own research. Little did he know then that quiz section would change the trajectory of his future work.

The Benzidine Rearrangement

In Hammond's lectures, students learned about chemical rearrangements, through which chemicals change their natures. One student in the quiz section asked Shine how the benzidine rearrangement took place.

The compound hydrazobenzene has two parts joined in the middle by two nitrogen atoms. In the presence of acids, the compound essentially turns itself inside out to be joined instead by two carbon atoms. Through this process, called the benzidine rearrangement, the hydrazobenzene is converted into benzidine.

This much they knew – but the student wanted to know exactly how it happened: the mechanisms and timing.

“Fortunately, I had enough sense to say, ‘I really don't know, but I will ask George Hammond. He will know,' because he'd come from Harvard,” Shine remembered.

But Hammond didn't know either. He suggested Shine read about it and present the information in a Tuesday evening seminar.

“I did some library research, and I found that nobody really knew, but there were famous people trying to find an answer,” Shine said. “One was my former teacher in England, Professor Ingold, and another was a professor in this country, Michael Dewar. They both had ideas but couldn't prove them.

“So, I had to tell George Hammond, the other research students and also the undergraduate who asked me, nobody really knew how this rearrangement took place.”

Hammond recommended that Shine should take up the search for an answer and first tackle what is known as the kinetic order in acid catalysis. Within two months, Shine had the answer: in contrast to a widespread assumption that only one proton was required to cause the rearrangement, it actually took two. This was the beginning of many years of research Shine revisited later at Texas Tech.

A Horatio Alger Story

Shine ultimately spent two years at Iowa State, followed by two years at the California Institute of Technology with Carl Niemann. At the end of those two years, he searched for another job in academia but came up empty handed. Instead, in the fall of 1951, he took an industry job in Passaic, New Jersey, working as a chemist for the United States Rubber Company.

Shine found an apartment in Ridgewood, New Jersey, but it was an area full of families and, for a single man, was quite lonely. So, when he wasn't working, Shine spent a lot of time in New York City. A friend from Gilman's lab named Irving Zarember had moved to Greenwich Village and lived in an apartment above a liquor store. That's where Shine met the captivating Sellie Schneider.

“She came with a friend to have dinner at Zarember's apartment,” he remembered. “We got to know each other, and I just fell for her. She came to dinner and we never parted.”

They were married in June 1953, but the bliss of Shine's marriage didn't extend into his work.

“I didn't enjoy the work for U.S. Rubber,” he explained. “I spent three years there, and they actually were very nice to me; they just let me do whatever I wanted. But, finally, they said, ‘Henry, you need to do some work to make money for us.' And that's when I said it was time for me to leave.”

At that time, most networking was done either through the convergence of research paths or by connecting at academic conferences. Recognizing that Shine's work was better suited to higher education than industry, his supervisors, Pliny O. Tawney and Bob Snyder, sent him to the 1954 American Chemical Society meeting in New York City. While there, Shine interviewed with someone from South Dakota State University, someone from one of the military academies and someone from Texas Tech – Professor William Moore Craig from Texas Tech's chemistry department.

During their interview, Craig said he regarded Shine as a sort of Horatio Alger story – a rags-to-riches narrative.

“I didn't know what he was talking about,” Shine said. “Apparently, he was impressed I'd come up from nowhere to be a chemist.”

Craig offered Shine a job at $4,400 for nine months. Shine asked for $4,800. After getting approval from department head Joe Dennis, Craig agreed. Shine and Sellie began celebrating, but about 11 p.m., the phone rang at their apartment. It was Texas Tech President E.N. Jones.

“He said he couldn't meet the budget of $4,800, and would I please come for $4,400?” Shine said. “Since I was full of martinis at that time, I said yes. Fortunately, I hadn't asked Dr. Craig to join me and my wife for martinis. It turned out he was an earnest teetotaler, and had I asked him to have a drink, he probably would have told the people in Lubbock, ‘This guy's no good.'”

The Benzidine Rearrangement Revisited

When Shine arrived in Lubbock in September 1954, Craig and Dennis welcomed him off the plane.

“As soon as I stepped out of the airport, they told me they thought I would enjoy not only lecturing, but also looking after the organic labs,” Shine said. “And I was too innocent to know what that meant, so I was deposited at the hotel downtown, given the textbook and told that lessons were already underway.”

There were only about 40 organic students at that time, so overseeing the labs and preparing his lectures still left Shine with plenty of time to pursue the research he'd begun at U.S. Rubber – so he did. Within his first years at Texas Tech, he made significant advancements in organic chemistry.

“I started studying the reactions of a very unstable compound called diacetyl peroxide in cyclohexene,” he said.

Until that time, scientists believed an intermediate in the decomposition of diacetyl peroxide, called the acetoxy radical, was so unstable that as soon as it was formed, it would decompose into carbon dioxide and an entity called the methyl radical. But, working with two other young chemists, Shine showed the acetoxy radical had a long enough life that it could be trapped by alkenes.

Once that was settled, Shine turned to another still-unanswered question: the benzidine rearrangement.

“When I got to Texas Tech, recalling my experience with the benzidine rearrangement in Ames, I decided I would take up the challenge to find out how it took place, and it took me years to really solve that problem,” Shine said. “To solve it, I had to learn to do mass spectrometry, which we couldn't do at Texas Tech in the early days because we didn't have an appropriate mass spectrometer, nor did we have a suitable scintillation counter for doing radioactive carbon work.”

Working with partners, A. N. Bourns of McMaster University in Canada, who did have a suitable mass spectrometer, and Clair Collins of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, who had the scintillation counter, Shine ultimately proved that in the presence of an acid, the two nitrogen atoms in hydrazobenzene parted at the same time as the two end carbon atoms of the benzene rings joined together, an occurrence called a concerted intramolecular rearrangement. Along the way, he learned how to do mass spectrometry and eventually won grant money to purchase Texas Tech's first quadrupole mass spectrometer.

“The benzidine rearrangement was so successfully solved it led me to study, by the same means, many other molecular rearrangements known to organic chemists,” Shine said. “I spent part of my life doing that.”

The Thianthrene Cation Radical

The history of his work on the benzidine rearrangement was later summarized in The Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. But it was in studying one of those other rearrangements that Shine made arguably his greatest discovery.

“Research is like that,” he noted. “You start doing something and you're led down an entirely different pathway.”

Because the benzidine rearrangement turns the molecule inside out when a nitrogen-nitrogen chemical bond breaks in the presence of acids, Shine suggested trying something similar with a different compound, diphenyl disulfide, in which two parts of the molecule are joined together by two sulfur atoms.

“Let's see if, in the presence of a strong acid, we can make that molecule turn inside out, so instead of being joined by two sulfur atoms, it will be joined by two carbon atoms and the sulfur atoms will be at the ends of the newly created molecule, one at each end,” Shine explained to a graduate student.

“When he tried that reaction, it was distressingly complicated,” Shine recalled. “If you dissolve diphenyl disulfide in concentrated sulfuric acid, you get the most beautifully purple-colored solution. And if you try to recover recognizable organic compounds from that, you fail – I was puzzled by this.”

The student was so frustrated that he quit his research with Shine and transferred to another professor, so Shine took up the challenge himself. He wanted to know why the purple solution was formed and why it gave such unrecognizable results.

“I was led to discover something called the thianthrene cation radical,” Shine explained.

In concentrated sulfuric acid, diphenyl disulfide is converted in part into a compound called thianthrene, which is then oxidized by the acid into a molecule that is positively charged – a cation – and has an unpaired electron – a radical. The name of that purple compound is the thianthrene cation radical.

“I became well-known for that,” Shine said, “and I started studying cation radical chemistry thereafter for years and years.”

Like the benzidine rearrangement, this research required instrumentation that Texas Tech didn't have – in this case, an electron spin spectrometer. So, with more grant funding from the U.S. Air Force's Office of Scientific Research, he purchased one, learned to use it and ultimately taught his students. The history of that discovery, Shine said, is recorded in the seminal 1998 book “Foundation of Modern EPR” by Gareth and Sandra Eaton and Kev Salikhov.

These early efforts were transformational, not only in the chemistry department, but also in organic chemistry as a whole.

“Professor Shine's pioneering work on the benzidine rearrangement reaction led synthetic chemists to make a variety of building blocks of chemical and biomedical importance,” said Guigen Li , a Horn Distinguished Professor in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry. “This reaction can result in high chemical yields and complete regioselective control, benefiting greener synthesis and production. Obviously, his groundwork showed a real-world impact and is still playing an important role in chemical synthesis today.

“His early research grants enabled the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry to obtain its first quadrupole mass spectrometer and first electron spin spectrometer, two key instruments that have promoted research productivity and creativity in chemistry and materials science here at Texas Tech University. Professor Shine's research achievements accelerated the process of Texas Tech's transferring from a mainly teaching college to a tier-one research university.”

A Horn Distinguished Professor

So perhaps it was only natural that the university rewarded his efforts.

Each summer, Shine returned to England for chemistry meetings or lecture tours – and above all, to see his family still there. When he returned from his annual trip in 1968, Dennis told Shine he must report to the Board of Regents – then called the Board of Directors – on June 1, a Saturday morning.

“I knew something was in the wind from that,” Shine remembered. “Why would they want me to appear?”

To Shine's astonishment, he was named a Horn Professor, now known as a Horn Distinguished Professor, the highest academic honor Texas Tech can bestow. He was the first in his department; in the entire university, only four others were named before him. The inaugural class in 1967 consisted of Carl Hammer in classical and romance languages; Antarctic explorer Alton Wade in geology, Ernest Wallace in history and Elo J. Urbanovsky, namesake of Texas Tech's Urbanovsky Park, in park administration, horticulture and entomology.

While Shine was away, Dennis, the department head, nominated him. Without Shine's knowledge, Dennis read his publications to see whom he frequently quoted, then reached out to more than 20 of those people for recommendation letters. Dennis even searched Shine's office to find a photo of him. It's the same procedure Shine went through eight years later when nominating the department's next Horn Distinguished Professor, Pill-Soon Song. But Shine followed in Dennis' footsteps in more ways than just that.

After Grover Murray began as Texas Tech president in 1966, he decided department heads, previously an essentially lifetime appointment, would now become department chairs, reviewable by the dean of their respective college. Dennis, who had been a department head for 17 years, was not fond of the change. As he told Shine, “If I've got the responsibility, I want the authority” – and he didn't find the positions comparable. So, after two years as chair, Dennis resigned in 1969.

Shine replaced him.

Challenges as Chair

As it turned out, Shine's term as department chair fell squarely during a transformational time for Texas Tech.

The university was working toward a medical school since the 1950s, and in 1969, it finally came to fruition. The Texas Tech University School of Medicine – which later grew into the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center – was established by state law on Sept. 1, 1969, as its own university whose president and board were the same individuals who held those posts at Texas Tech.

“When the planning for the medical school was begun, I, as the chair of chemistry, was appointed as a consultant, meaning that I would attend the planning meetings and voice my advice and feelings,” Shine said.

Part of the initial plan for the medical school involved shared facilities between the School of Medicine and existing Texas Tech departments. So, Shine had to figure out how to accommodate the varying educational needs of students at both universities.

“The degrees in the sciences were supposed to be offered in Texas Tech, not the medical school,” Shine explained. “There were to be science departments in the medical school, such as biochemistry, physiology, etc., but the classes were to be offered on the main campus. The School of Medicine was planned to be unlike traditional medical schools, but that plan was completely disregarded by the faculty who were first appointed to it; they wanted a traditional medical school.

“Insofar as biochemistry was concerned, in the School of Medicine, there was no interest whatsoever in having classes taught in the chemistry department of Texas Tech. So, we were asked by President Murray and the Graduate Dean Knox Jones to try to fashion a curriculum that suited the medical school but was based on a degree to be granted in the chemistry department.”

Shine tapped two biochemists in the department to work with the School of Medicine's biochemists to settle on a common curriculum, but no satisfactory agreement could be reached.

An exacerbating factor was space as Shine tried to balance the research needs of both his own department and the science departments of the medical school. A recent addition to the Chemistry building had created extra laboratory space, but the facilities were unfinished. Money had run out, leaving a number of research laboratories partly furnished.

“I told Dr. Murray more space would be available if we had the money to furnish those unfinished research labs,” Shine recalled. “He gave us the money, about $100,000, taking it from the medical school budget. That solved the space problem but was not pleasing financially to the dean of the medical school.”

Ultimately, there were just too many points of contention, and the only solution was the complete academic separation of the chemistry and other Texas Tech departments from the School of Medicine's science departments – which eventually happened.

“We must have all been pretty stubborn in those days certainly,” Shine said. “As for the School of Medicine, I felt then that they had betrayed the original planners of a nontraditional medical school.

“I look back in regret at not achieving a sensible pathway more quickly. If I had been a wiser man then, we may have achieved an amicable solution sooner. As it happens, history has shown that the original concept was idealistic and unworkable. Change was inevitable and has been a tremendous success. The medical school has become a phenomenal development, not only in its clinical but also in its science departments, particularly its Department of Cell Biology & Biochemistry .”

The Battle Over Tenure

After six years of departmental administration, during which his own research was forced to take a back seat, Shine resigned as chair in 1975. He went back to what he probably thought would be a quieter life, conducting his own research and teaching students.

But in the early years of the next decade, another pivotal moment in university history disrupted the peace. The matter was faculty tenure.

It began in March 1981, when the five-member Faculty Tenure & Privilege Committee resigned over a matter in which the upper administration had failed to exercise what the committee considered due process. In the early months of 1984, a draft of a new tenure policy was devised by President Lauro Cavazos and placed before the faculty. The draft caused a storm of protest.

To properly appreciate the events of that time, it is necessary to understand how the concept of tenure had been achieved.

“When I joined Texas Technological College in 1954, there was no such thing as tenure, and there was no drive in Texas Tech toward it,” Shine said. “But, in 1957, I think, the Board of Directors voted not to renew the contracts of three members of the faculty. The members were Herb Greenberg, Per Stensland and Byron Abernethy. They learned of their dismissal in the Sunday newspaper. Because of that, Texas Tech was placed on a blacklist by the American Association of University Professors for something like 10 years.

“When Grover Murray was offered the presidency of Texas Tech, he made getting off the blacklist and tenure conditions of acceptance, as well as accommodating the three who had been fired.

“Thus, tenure became a hard-won concept for the faculty, and to change the tenure policy inappropriately in 1984 was unacceptable to them.”

One criticism of the policy was the notion that a young faculty member could work hard, achieve tenure – essentially securing a lifetime appointment – then coast for the remainder of their career. It's something that probably happened occasionally, the faculty felt, but it was not common and certainly not a sufficient reason to discontinue tenure altogether.

So, as the faculty pushed back, they saw Cavazos' stance as a betrayal. William Mayer-Oakes, then the chair of the Faculty Senate, asked Shine to speak at a large faculty gathering in September 1984 and propose a motion calling for a mail ballot of the voting faculty as to whether or not the faculty had confidence in Cavazos. The motion was passed with no opposition.

“His reason for asking me, I think, was that I was then the senior Horn Professor,” Shine said.

But Shine also had other qualities Mayer-Oakes probably recognized.

“Henry Shine got up and gave an impassioned argument against the new policy,” remembered Gary Elbow , a retired geography professor and former associate vice provost. “Henry was not the sort of person who would get into a brawl like that if he didn't feel very strongly about it, and he is a very highly principled sort of guy and extremely articulate, so when he gets up and condemns something, you know it's been condemned.”

The mail ballot with the motion expressing no confidence in Cavazos was indeed placed before the voting faculty and was passed overwhelmingly.

“Afterwards, I felt very much lost, as if we had taken a most unusual step,” Shine said. “I remember saying to the faculty that it was the most somber occasion of my life at Texas Tech.”

Continuing Education

Fortunately, most of Shine's career memories are highlights – moments of success in the classroom and the laboratory. As you might expect, he received numerous recognitions for both teaching and research.

Shine was awarded the Faculty Research Award in 1982, the Texas Tech Dads Association Distinguished Faculty Research Award in 1983, the President's Academic Achievement Award in 1991 and the Faculty Distinguished Leadership Award in 1994 from the Texas Tech Dads and Moms Association, now known as the Texas Tech Parents Association .

In 1986, he received a Senior Distinguished U.S. Scientist Award from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, enabling Shine and his wife to spend a year in Germany with a position at the University of Hamburg. The American Chemical Society's Division of Organic Chemistry listed Shine among the 300 famous organic chemists who contributed to the fundamentals of organic chemistry. He taught student after student who went on to their own auspicious careers, some in industry, some in academia.