User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

S.3.2 hypothesis testing (p-value approach).

The P -value approach involves determining "likely" or "unlikely" by determining the probability — assuming the null hypothesis was true — of observing a more extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternative hypothesis than the one observed. If the P -value is small, say less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), then it is "unlikely." And, if the P -value is large, say more than \(\alpha\), then it is "likely."

If the P -value is less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis. And, if the P -value is greater than \(\alpha\), then the null hypothesis is not rejected.

Specifically, the four steps involved in using the P -value approach to conducting any hypothesis test are:

- Specify the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Using the sample data and assuming the null hypothesis is true, calculate the value of the test statistic. Again, to conduct the hypothesis test for the population mean μ , we use the t -statistic \(t^*=\frac{\bar{x}-\mu}{s/\sqrt{n}}\) which follows a t -distribution with n - 1 degrees of freedom.

- Using the known distribution of the test statistic, calculate the P -value : "If the null hypothesis is true, what is the probability that we'd observe a more extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternative hypothesis than we did?" (Note how this question is equivalent to the question answered in criminal trials: "If the defendant is innocent, what is the chance that we'd observe such extreme criminal evidence?")

- Set the significance level, \(\alpha\), the probability of making a Type I error to be small — 0.01, 0.05, or 0.10. Compare the P -value to \(\alpha\). If the P -value is less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If the P -value is greater than \(\alpha\), do not reject the null hypothesis.

Example S.3.2.1

Mean gpa section .

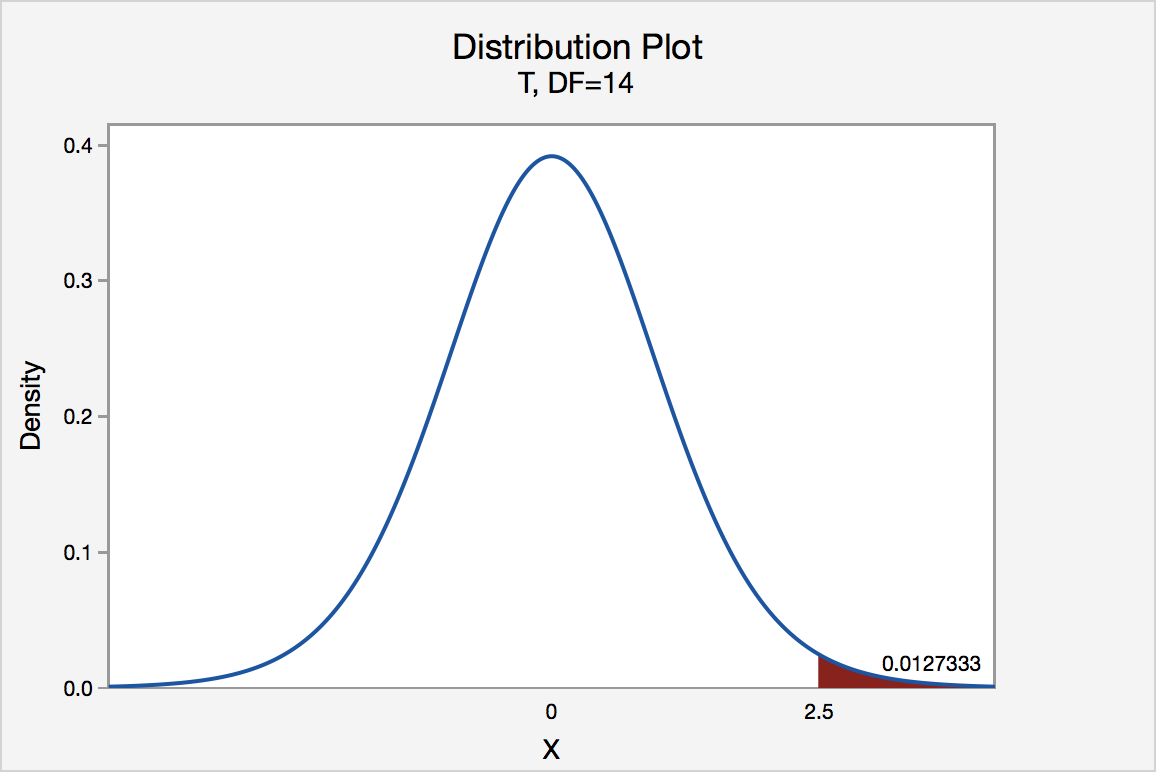

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t * equaling 2.5. Since n = 15, our test statistic t * has n - 1 = 14 degrees of freedom. Also, suppose we set our significance level α at 0.05 so that we have only a 5% chance of making a Type I error.

Right Tailed

The P -value for conducting the right-tailed test H 0 : μ = 3 versus H A : μ > 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic greater than t * = 2.5 if the population mean \(\mu\) really were 3. Recall that probability equals the area under the probability curve. The P -value is therefore the area under a t n - 1 = t 14 curve and to the right of the test statistic t * = 2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P -value is 0.0127. The graph depicts this visually.

The P -value, 0.0127, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t * in the direction of H A if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P -value, 0.0127, is less than \(\alpha\) = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis H A : μ > 3.

Note that we would not reject H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of H A : μ > 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to \(\alpha\) = 0.01 instead, as the P -value, 0.0127, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

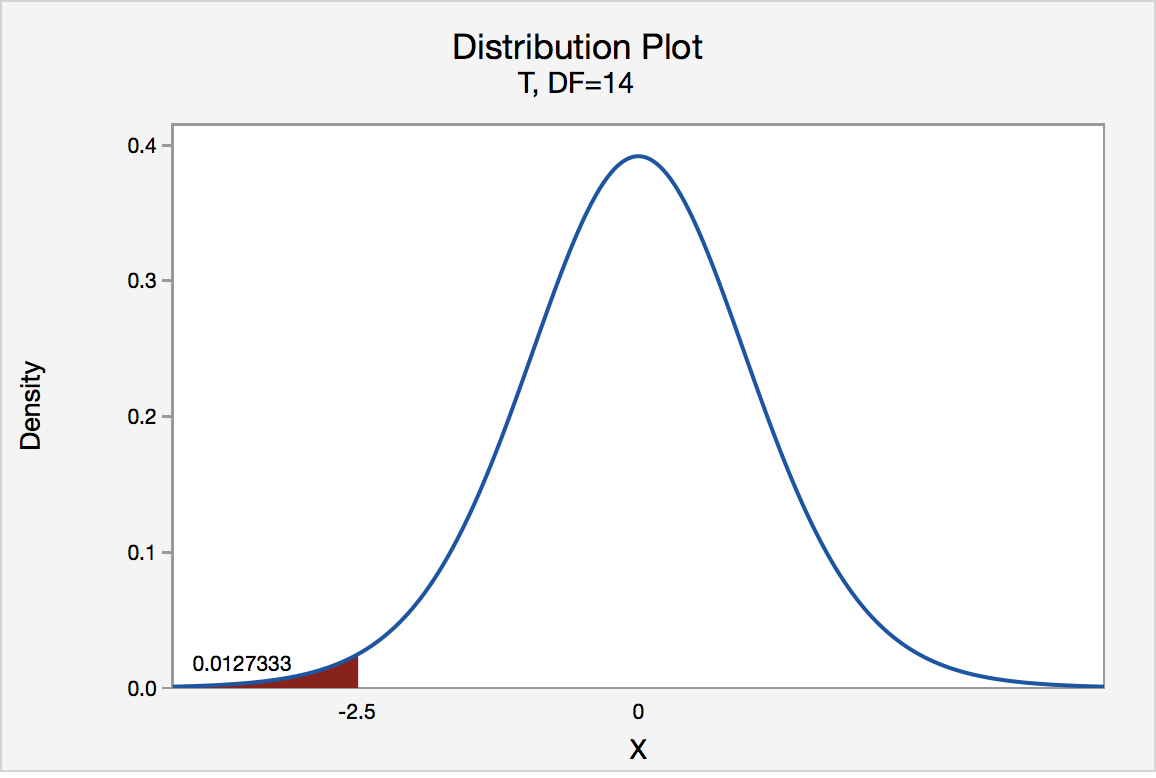

Left Tailed

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t * instead of equaling -2.5. The P -value for conducting the left-tailed test H 0 : μ = 3 versus H A : μ < 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic less than t * = -2.5 if the population mean μ really were 3. The P -value is therefore the area under a t n - 1 = t 14 curve and to the left of the test statistic t* = -2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P -value is 0.0127. The graph depicts this visually.

The P -value, 0.0127, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t * in the direction of H A if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P -value, 0.0127, is less than α = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis H A : μ < 3.

Note that we would not reject H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of H A : μ < 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to α = 0.01 instead, as the P -value, 0.0127, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

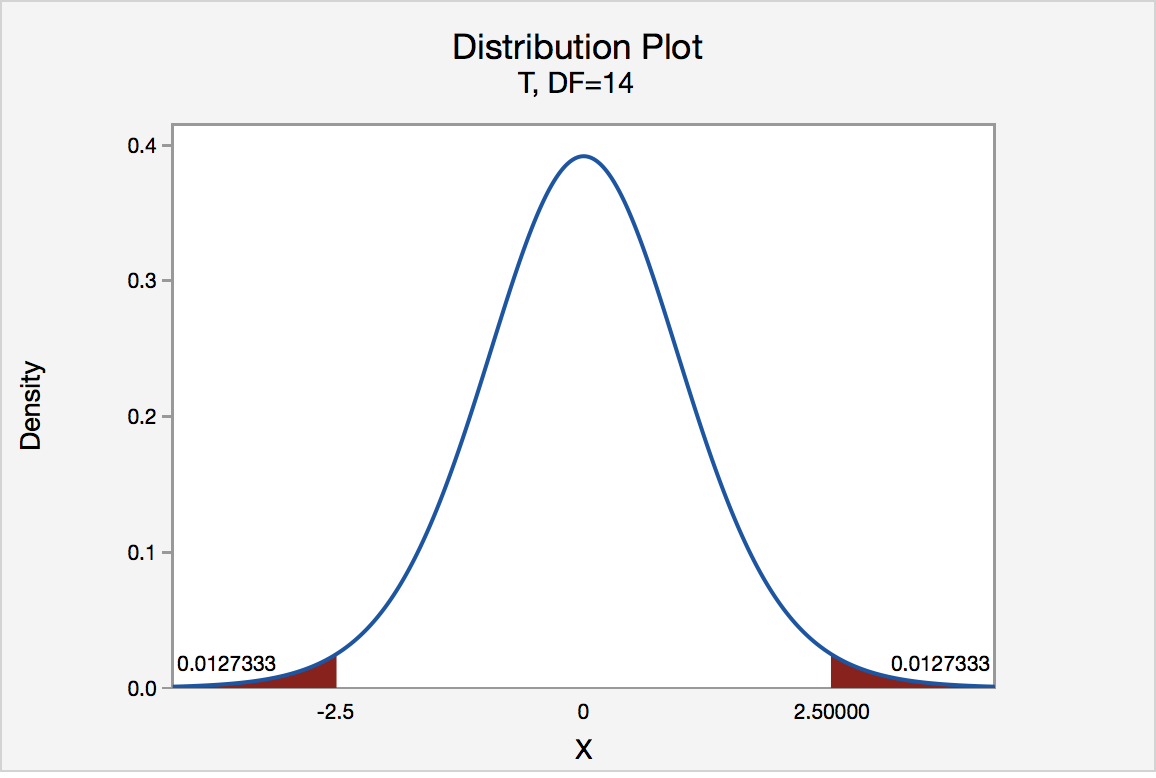

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose again that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t * instead of equaling -2.5. The P -value for conducting the two-tailed test H 0 : μ = 3 versus H A : μ ≠ 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic less than -2.5 or greater than 2.5 if the population mean μ really was 3. That is, the two-tailed test requires taking into account the possibility that the test statistic could fall into either tail (hence the name "two-tailed" test). The P -value is, therefore, the area under a t n - 1 = t 14 curve to the left of -2.5 and to the right of 2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P -value is 0.0127 + 0.0127, or 0.0254. The graph depicts this visually.

Note that the P -value for a two-tailed test is always two times the P -value for either of the one-tailed tests. The P -value, 0.0254, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t * in the direction of H A if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P -value, 0.0254, is less than α = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis H A : μ ≠ 3.

Note that we would not reject H 0 : μ = 3 in favor of H A : μ ≠ 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to α = 0.01 instead, as the P -value, 0.0254, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

Now that we have reviewed the critical value and P -value approach procedures for each of the three possible hypotheses, let's look at three new examples — one of a right-tailed test, one of a left-tailed test, and one of a two-tailed test.

The good news is that, whenever possible, we will take advantage of the test statistics and P -values reported in statistical software, such as Minitab, to conduct our hypothesis tests in this course.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Statistics and probability

Course: statistics and probability > unit 12, hypothesis testing and p-values.

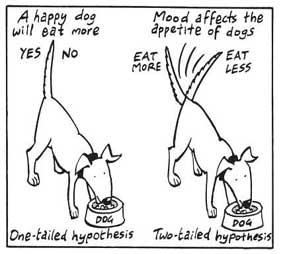

- One-tailed and two-tailed tests

- Z-statistics vs. T-statistics

- Small sample hypothesis test

- Large sample proportion hypothesis testing

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and significance.

Jacob Shreffler ; Martin R. Huecker .

Affiliations

Last Update: March 13, 2023 .

- Definition/Introduction

Medical providers often rely on evidence-based medicine to guide decision-making in practice. Often a research hypothesis is tested with results provided, typically with p values, confidence intervals, or both. Additionally, statistical or research significance is estimated or determined by the investigators. Unfortunately, healthcare providers may have different comfort levels in interpreting these findings, which may affect the adequate application of the data.

- Issues of Concern

Without a foundational understanding of hypothesis testing, p values, confidence intervals, and the difference between statistical and clinical significance, it may affect healthcare providers' ability to make clinical decisions without relying purely on the research investigators deemed level of significance. Therefore, an overview of these concepts is provided to allow medical professionals to use their expertise to determine if results are reported sufficiently and if the study outcomes are clinically appropriate to be applied in healthcare practice.

Hypothesis Testing

Investigators conducting studies need research questions and hypotheses to guide analyses. Starting with broad research questions (RQs), investigators then identify a gap in current clinical practice or research. Any research problem or statement is grounded in a better understanding of relationships between two or more variables. For this article, we will use the following research question example:

Research Question: Is Drug 23 an effective treatment for Disease A?

Research questions do not directly imply specific guesses or predictions; we must formulate research hypotheses. A hypothesis is a predetermined declaration regarding the research question in which the investigator(s) makes a precise, educated guess about a study outcome. This is sometimes called the alternative hypothesis and ultimately allows the researcher to take a stance based on experience or insight from medical literature. An example of a hypothesis is below.

Research Hypothesis: Drug 23 will significantly reduce symptoms associated with Disease A compared to Drug 22.

The null hypothesis states that there is no statistical difference between groups based on the stated research hypothesis.

Researchers should be aware of journal recommendations when considering how to report p values, and manuscripts should remain internally consistent.

Regarding p values, as the number of individuals enrolled in a study (the sample size) increases, the likelihood of finding a statistically significant effect increases. With very large sample sizes, the p-value can be very low significant differences in the reduction of symptoms for Disease A between Drug 23 and Drug 22. The null hypothesis is deemed true until a study presents significant data to support rejecting the null hypothesis. Based on the results, the investigators will either reject the null hypothesis (if they found significant differences or associations) or fail to reject the null hypothesis (they could not provide proof that there were significant differences or associations).

To test a hypothesis, researchers obtain data on a representative sample to determine whether to reject or fail to reject a null hypothesis. In most research studies, it is not feasible to obtain data for an entire population. Using a sampling procedure allows for statistical inference, though this involves a certain possibility of error. [1] When determining whether to reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis, mistakes can be made: Type I and Type II errors. Though it is impossible to ensure that these errors have not occurred, researchers should limit the possibilities of these faults. [2]

Significance

Significance is a term to describe the substantive importance of medical research. Statistical significance is the likelihood of results due to chance. [3] Healthcare providers should always delineate statistical significance from clinical significance, a common error when reviewing biomedical research. [4] When conceptualizing findings reported as either significant or not significant, healthcare providers should not simply accept researchers' results or conclusions without considering the clinical significance. Healthcare professionals should consider the clinical importance of findings and understand both p values and confidence intervals so they do not have to rely on the researchers to determine the level of significance. [5] One criterion often used to determine statistical significance is the utilization of p values.

P values are used in research to determine whether the sample estimate is significantly different from a hypothesized value. The p-value is the probability that the observed effect within the study would have occurred by chance if, in reality, there was no true effect. Conventionally, data yielding a p<0.05 or p<0.01 is considered statistically significant. While some have debated that the 0.05 level should be lowered, it is still universally practiced. [6] Hypothesis testing allows us to determine the size of the effect.

An example of findings reported with p values are below:

Statement: Drug 23 reduced patients' symptoms compared to Drug 22. Patients who received Drug 23 (n=100) were 2.1 times less likely than patients who received Drug 22 (n = 100) to experience symptoms of Disease A, p<0.05.

Statement:Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 experienced fewer symptoms (M = 1.3, SD = 0.7) compared to individuals who were prescribed Drug 22 (M = 5.3, SD = 1.9). This finding was statistically significant, p= 0.02.

For either statement, if the threshold had been set at 0.05, the null hypothesis (that there was no relationship) should be rejected, and we should conclude significant differences. Noticeably, as can be seen in the two statements above, some researchers will report findings with < or > and others will provide an exact p-value (0.000001) but never zero [6] . When examining research, readers should understand how p values are reported. The best practice is to report all p values for all variables within a study design, rather than only providing p values for variables with significant findings. [7] The inclusion of all p values provides evidence for study validity and limits suspicion for selective reporting/data mining.

While researchers have historically used p values, experts who find p values problematic encourage the use of confidence intervals. [8] . P-values alone do not allow us to understand the size or the extent of the differences or associations. [3] In March 2016, the American Statistical Association (ASA) released a statement on p values, noting that scientific decision-making and conclusions should not be based on a fixed p-value threshold (e.g., 0.05). They recommend focusing on the significance of results in the context of study design, quality of measurements, and validity of data. Ultimately, the ASA statement noted that in isolation, a p-value does not provide strong evidence. [9]

When conceptualizing clinical work, healthcare professionals should consider p values with a concurrent appraisal study design validity. For example, a p-value from a double-blinded randomized clinical trial (designed to minimize bias) should be weighted higher than one from a retrospective observational study [7] . The p-value debate has smoldered since the 1950s [10] , and replacement with confidence intervals has been suggested since the 1980s. [11]

Confidence Intervals

A confidence interval provides a range of values within given confidence (e.g., 95%), including the accurate value of the statistical constraint within a targeted population. [12] Most research uses a 95% CI, but investigators can set any level (e.g., 90% CI, 99% CI). [13] A CI provides a range with the lower bound and upper bound limits of a difference or association that would be plausible for a population. [14] Therefore, a CI of 95% indicates that if a study were to be carried out 100 times, the range would contain the true value in 95, [15] confidence intervals provide more evidence regarding the precision of an estimate compared to p-values. [6]

In consideration of the similar research example provided above, one could make the following statement with 95% CI:

Statement: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22; there was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

It is important to note that the width of the CI is affected by the standard error and the sample size; reducing a study sample number will result in less precision of the CI (increase the width). [14] A larger width indicates a smaller sample size or a larger variability. [16] A researcher would want to increase the precision of the CI. For example, a 95% CI of 1.43 – 1.47 is much more precise than the one provided in the example above. In research and clinical practice, CIs provide valuable information on whether the interval includes or excludes any clinically significant values. [14]

Null values are sometimes used for differences with CI (zero for differential comparisons and 1 for ratios). However, CIs provide more information than that. [15] Consider this example: A hospital implements a new protocol that reduced wait time for patients in the emergency department by an average of 25 minutes (95% CI: -2.5 – 41 minutes). Because the range crosses zero, implementing this protocol in different populations could result in longer wait times; however, the range is much higher on the positive side. Thus, while the p-value used to detect statistical significance for this may result in "not significant" findings, individuals should examine this range, consider the study design, and weigh whether or not it is still worth piloting in their workplace.

Similarly to p-values, 95% CIs cannot control for researchers' errors (e.g., study bias or improper data analysis). [14] In consideration of whether to report p-values or CIs, researchers should examine journal preferences. When in doubt, reporting both may be beneficial. [13] An example is below:

Reporting both: Individuals who were prescribed Drug 23 had no symptoms after three days, which was significantly faster than those prescribed Drug 22, p = 0.009. There was a mean difference between the two groups of days to the recovery of 4.2 days (95% CI: 1.9 – 7.8).

- Clinical Significance

Recall that clinical significance and statistical significance are two different concepts. Healthcare providers should remember that a study with statistically significant differences and large sample size may be of no interest to clinicians, whereas a study with smaller sample size and statistically non-significant results could impact clinical practice. [14] Additionally, as previously mentioned, a non-significant finding may reflect the study design itself rather than relationships between variables.

Healthcare providers using evidence-based medicine to inform practice should use clinical judgment to determine the practical importance of studies through careful evaluation of the design, sample size, power, likelihood of type I and type II errors, data analysis, and reporting of statistical findings (p values, 95% CI or both). [4] Interestingly, some experts have called for "statistically significant" or "not significant" to be excluded from work as statistical significance never has and will never be equivalent to clinical significance. [17]

The decision on what is clinically significant can be challenging, depending on the providers' experience and especially the severity of the disease. Providers should use their knowledge and experiences to determine the meaningfulness of study results and make inferences based not only on significant or insignificant results by researchers but through their understanding of study limitations and practical implications.

- Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

All physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals should strive to understand the concepts in this chapter. These individuals should maintain the ability to review and incorporate new literature for evidence-based and safe care.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Jacob Shreffler declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Martin Huecker declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Shreffler J, Huecker MR. Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance. [Updated 2023 Mar 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- The reporting of p values, confidence intervals and statistical significance in Preventive Veterinary Medicine (1997-2017). [PeerJ. 2021] The reporting of p values, confidence intervals and statistical significance in Preventive Veterinary Medicine (1997-2017). Messam LLM, Weng HY, Rosenberger NWY, Tan ZH, Payet SDM, Santbakshsing M. PeerJ. 2021; 9:e12453. Epub 2021 Nov 24.

- Review Clinical versus statistical significance: interpreting P values and confidence intervals related to measures of association to guide decision making. [J Pharm Pract. 2010] Review Clinical versus statistical significance: interpreting P values and confidence intervals related to measures of association to guide decision making. Ferrill MJ, Brown DA, Kyle JA. J Pharm Pract. 2010 Aug; 23(4):344-51. Epub 2010 Apr 13.

- Interpreting "statistical hypothesis testing" results in clinical research. [J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012] Interpreting "statistical hypothesis testing" results in clinical research. Sarmukaddam SB. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2012 Apr; 3(2):65-9.

- Confidence intervals in procedural dermatology: an intuitive approach to interpreting data. [Dermatol Surg. 2005] Confidence intervals in procedural dermatology: an intuitive approach to interpreting data. Alam M, Barzilai DA, Wrone DA. Dermatol Surg. 2005 Apr; 31(4):462-6.

- Review Is statistical significance testing useful in interpreting data? [Reprod Toxicol. 1993] Review Is statistical significance testing useful in interpreting data? Savitz DA. Reprod Toxicol. 1993; 7(2):95-100.

Recent Activity

- Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance - StatPearl... Hypothesis Testing, P Values, Confidence Intervals, and Significance - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is P-Value?

Understanding p-value.

- P-Value in Hypothesis Testing

The Bottom Line

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Analysis

P-Value: What It Is, How to Calculate It, and Why It Matters

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/100378251brianbeersheadshot__brian_beers-5bfc26274cedfd0026c00ebd.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

In statistics, a p-value is defined as a number that indicates how likely you are to obtain a value that is at least equal to or more than the actual observation if the null hypothesis is correct.

The p-value serves as an alternative to rejection points to provide the smallest level of significance at which the null hypothesis would be rejected. A smaller p-value means stronger evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

P-value is often used to promote credibility for studies or reports by government agencies. For example, the U.S. Census Bureau stipulates that any analysis with a p-value greater than 0.10 must be accompanied by a statement that the difference is not statistically different from zero. The Census Bureau also has standards in place stipulating which p-values are acceptable for various publications.

Key Takeaways

- A p-value is a statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data.

- A p-value measures the probability of obtaining the observed results, assuming that the null hypothesis is true.

- The lower the p-value, the greater the statistical significance of the observed difference.

- A p-value of 0.05 or lower is generally considered statistically significant.

- P-value can serve as an alternative to—or in addition to—preselected confidence levels for hypothesis testing.

Jessica Olah / Investopedia

P-values are usually found using p-value tables or spreadsheets/statistical software. These calculations are based on the assumed or known probability distribution of the specific statistic tested. The sample size, which determines the reliability of the observed data, directly influences the accuracy of the p-value calculation. he p-value approach to hypothesis testing uses the calculated he p-value approach to hypothesis testing uses the calculated P-values are calculated from the deviation between the observed value and a chosen reference value, given the probability distribution of the statistic, with a greater difference between the two values corresponding to a lower p-value.

Mathematically, the p-value is calculated using integral calculus from the area under the probability distribution curve for all values of statistics that are at least as far from the reference value as the observed value is, relative to the total area under the probability distribution curve. Standard deviations, which quantify the dispersion of data points from the mean, are instrumental in this calculation.

The calculation for a p-value varies based on the type of test performed. The three test types describe the location on the probability distribution curve: lower-tailed test, upper-tailed test, or two-tailed test . In each case, the degrees of freedom play a crucial role in determining the shape of the distribution and thus, the calculation of the p-value.

In a nutshell, the greater the difference between two observed values, the less likely it is that the difference is due to simple random chance, and this is reflected by a lower p-value.

The P-Value Approach to Hypothesis Testing

The p-value approach to hypothesis testing uses the calculated probability to determine whether there is evidence to reject the null hypothesis. This determination relies heavily on the test statistic, which summarizes the information from the sample relevant to the hypothesis being tested. The null hypothesis, also known as the conjecture, is the initial claim about a population (or data-generating process). The alternative hypothesis states whether the population parameter differs from the value of the population parameter stated in the conjecture.

In practice, the significance level is stated in advance to determine how small the p-value must be to reject the null hypothesis. Because different researchers use different levels of significance when examining a question, a reader may sometimes have difficulty comparing results from two different tests. P-values provide a solution to this problem.

Even a low p-value is not necessarily proof of statistical significance, since there is still a possibility that the observed data are the result of chance. Only repeated experiments or studies can confirm if a relationship is statistically significant.

For example, suppose a study comparing returns from two particular assets was undertaken by different researchers who used the same data but different significance levels. The researchers might come to opposite conclusions regarding whether the assets differ.

If one researcher used a confidence level of 90% and the other required a confidence level of 95% to reject the null hypothesis, and if the p-value of the observed difference between the two returns was 0.08 (corresponding to a confidence level of 92%), then the first researcher would find that the two assets have a difference that is statistically significant , while the second would find no statistically significant difference between the returns.

To avoid this problem, the researchers could report the p-value of the hypothesis test and allow readers to interpret the statistical significance themselves. This is called a p-value approach to hypothesis testing. Independent observers could note the p-value and decide for themselves whether that represents a statistically significant difference or not.

Example of P-Value

An investor claims that their investment portfolio’s performance is equivalent to that of the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 Index . To determine this, the investor conducts a two-tailed test.

The null hypothesis states that the portfolio’s returns are equivalent to the S&P 500’s returns over a specified period, while the alternative hypothesis states that the portfolio’s returns and the S&P 500’s returns are not equivalent—if the investor conducted a one-tailed test , the alternative hypothesis would state that the portfolio’s returns are either less than or greater than the S&P 500’s returns.

The p-value hypothesis test does not necessarily make use of a preselected confidence level at which the investor should reset the null hypothesis that the returns are equivalent. Instead, it provides a measure of how much evidence there is to reject the null hypothesis. The smaller the p-value, the greater the evidence against the null hypothesis.

Thus, if the investor finds that the p-value is 0.001, there is strong evidence against the null hypothesis, and the investor can confidently conclude that the portfolio’s returns and the S&P 500’s returns are not equivalent.

Although this does not provide an exact threshold as to when the investor should accept or reject the null hypothesis, it does have another very practical advantage. P-value hypothesis testing offers a direct way to compare the relative confidence that the investor can have when choosing among multiple different types of investments or portfolios relative to a benchmark such as the S&P 500.

For example, for two portfolios, A and B, whose performance differs from the S&P 500 with p-values of 0.10 and 0.01, respectively, the investor can be much more confident that portfolio B, with a lower p-value, will actually show consistently different results.

Is a 0.05 P-Value Significant?

A p-value less than 0.05 is typically considered to be statistically significant, in which case the null hypothesis should be rejected. A p-value greater than 0.05 means that deviation from the null hypothesis is not statistically significant, and the null hypothesis is not rejected.

What Does a P-Value of 0.001 Mean?

A p-value of 0.001 indicates that if the null hypothesis tested were indeed true, then there would be a one-in-1,000 chance of observing results at least as extreme. This leads the observer to reject the null hypothesis because either a highly rare data result has been observed or the null hypothesis is incorrect.

How Can You Use P-Value to Compare 2 Different Results of a Hypothesis Test?

If you have two different results, one with a p-value of 0.04 and one with a p-value of 0.06, the result with a p-value of 0.04 will be considered more statistically significant than the p-value of 0.06. Beyond this simplified example, you could compare a 0.04 p-value to a 0.001 p-value. Both are statistically significant, but the 0.001 example provides an even stronger case against the null hypothesis than the 0.04.

The p-value is used to measure the significance of observational data. When researchers identify an apparent relationship between two variables, there is always a possibility that this correlation might be a coincidence. A p-value calculation helps determine if the observed relationship could arise as a result of chance.

U.S. Census Bureau. “ Statistical Quality Standard E1: Analyzing Data .”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/shutterstock_67023106-5bfc2b9846e0fb005144dd87.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of hypothesis

Did you know.

The Difference Between Hypothesis and Theory

A hypothesis is an assumption, an idea that is proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested to see if it might be true.

In the scientific method, the hypothesis is constructed before any applicable research has been done, apart from a basic background review. You ask a question, read up on what has been studied before, and then form a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is usually tentative; it's an assumption or suggestion made strictly for the objective of being tested.

A theory , in contrast, is a principle that has been formed as an attempt to explain things that have already been substantiated by data. It is used in the names of a number of principles accepted in the scientific community, such as the Big Bang Theory . Because of the rigors of experimentation and control, it is understood to be more likely to be true than a hypothesis is.

In non-scientific use, however, hypothesis and theory are often used interchangeably to mean simply an idea, speculation, or hunch, with theory being the more common choice.

Since this casual use does away with the distinctions upheld by the scientific community, hypothesis and theory are prone to being wrongly interpreted even when they are encountered in scientific contexts—or at least, contexts that allude to scientific study without making the critical distinction that scientists employ when weighing hypotheses and theories.

The most common occurrence is when theory is interpreted—and sometimes even gleefully seized upon—to mean something having less truth value than other scientific principles. (The word law applies to principles so firmly established that they are almost never questioned, such as the law of gravity.)

This mistake is one of projection: since we use theory in general to mean something lightly speculated, then it's implied that scientists must be talking about the same level of uncertainty when they use theory to refer to their well-tested and reasoned principles.

The distinction has come to the forefront particularly on occasions when the content of science curricula in schools has been challenged—notably, when a school board in Georgia put stickers on textbooks stating that evolution was "a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things." As Kenneth R. Miller, a cell biologist at Brown University, has said , a theory "doesn’t mean a hunch or a guess. A theory is a system of explanations that ties together a whole bunch of facts. It not only explains those facts, but predicts what you ought to find from other observations and experiments.”

While theories are never completely infallible, they form the basis of scientific reasoning because, as Miller said "to the best of our ability, we’ve tested them, and they’ve held up."

- proposition

- supposition

hypothesis , theory , law mean a formula derived by inference from scientific data that explains a principle operating in nature.

hypothesis implies insufficient evidence to provide more than a tentative explanation.

theory implies a greater range of evidence and greater likelihood of truth.

law implies a statement of order and relation in nature that has been found to be invariable under the same conditions.

Examples of hypothesis in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'hypothesis.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Greek, from hypotithenai to put under, suppose, from hypo- + tithenai to put — more at do

1641, in the meaning defined at sense 1a

Phrases Containing hypothesis

- counter - hypothesis

- nebular hypothesis

- null hypothesis

- planetesimal hypothesis

- Whorfian hypothesis

Articles Related to hypothesis

This is the Difference Between a...

This is the Difference Between a Hypothesis and a Theory

In scientific reasoning, they're two completely different things

Dictionary Entries Near hypothesis

hypothermia

hypothesize

Cite this Entry

“Hypothesis.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypothesis. Accessed 4 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of hypothesis, medical definition, medical definition of hypothesis, more from merriam-webster on hypothesis.

Nglish: Translation of hypothesis for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of hypothesis for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about hypothesis

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 31, pilfer: how to play and win, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, etymologies for every day of the week, games & quizzes.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.