Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Paradigm? Types of Research Paradigms with Examples

If you’re a researcher, you’ve probably heard the term “ research paradigm .” And, if you are a researcher, especially if you haven’t been trained under the social sciences, you are probably confused by the concept of a research paradigm . What is a research paradigm? How does it apply to my research? Why is it important?

Research paradigms refer to the beliefs and assumptions that provide the structure for your research. These can be characteristics of your discipline or even your personal beliefs. For example, if you are a physical scientist and you are conducting research on the performance of a newly developed catalyst for removing chemical impurities from drinking water, your study is probably based on the premise that there is one reality, and your results will show that the new product either works better or it doesn’t. However, if your research discipline is education and you’re looking at the effects of parental literacy rates on the literacy or academic success of their children, you will not expect a such a definite result, and you may be examining your topic from different viewpoints, such as cultural or socio-economic. Your findings will then depend on those assumptions, beliefs, and biases.

The rest of this article will try to clarify the concept of research paradigms, provide a research paradigm definition, and offer some examples of different types of research paradigms . While years of study may not completely clear up your confusion about research paradigms , perhaps you will think a little better of them and how they can help you in your work and maybe even in your personal life.

Table of Contents

What is a research paradigm?

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a paradigm is “ a philosophical and theoretical framework of a scientific school or discipline within which theories, laws, and generalizations and the experiments performed in support of them are formulated. ” 1 As applied in the context of research, a research paradigm is a worldview or philosophical framework, including ideas, beliefs, and biases, that guides the research process. The research paradigm in which a study is situated helps determine the manner in which the research will be conducted.

The research paradigm is the framework into which the theories and practices of your discipline fit to create the research plan. This foundation guides all areas of your research plan, including the aim of the study, research question, instruments or measurements used, and analysis methods.

Most research paradigms are based on one of two model types: positivism or interpretivism. These guide the theories and methodologies used in the research project. In general, positivist research paradigms lead to quantitative studies and interpretivist research paradigms lead to qualitative studies. Of course, there are many variations of both of these research paradigm types, some of which lead to mixed-method studies.

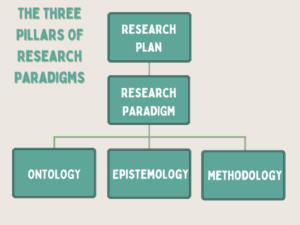

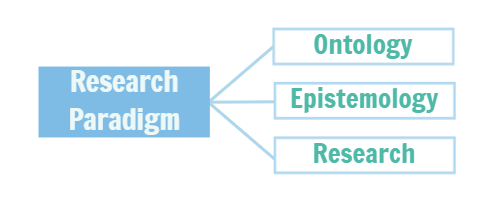

What are the three pillars of research paradigms ?

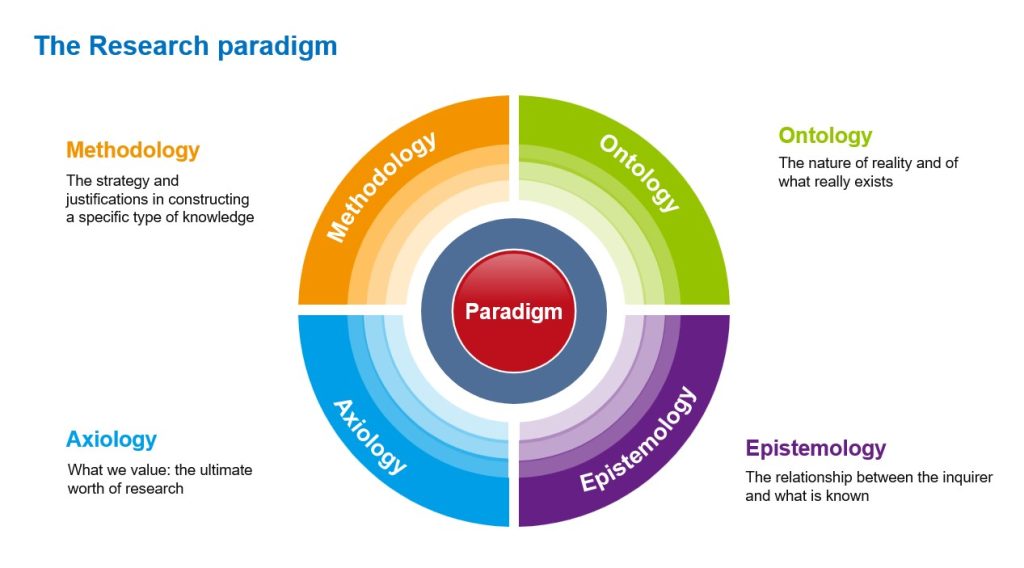

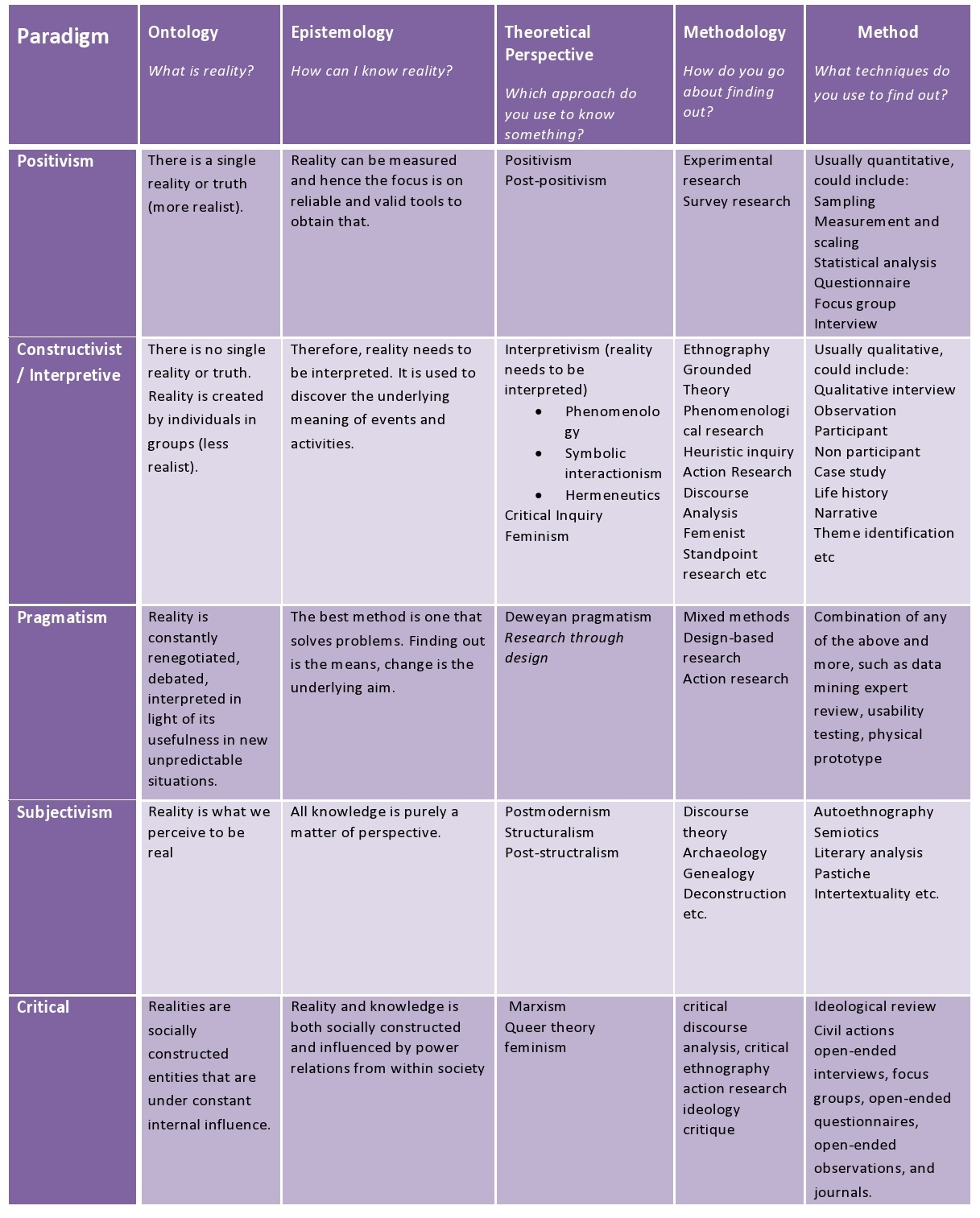

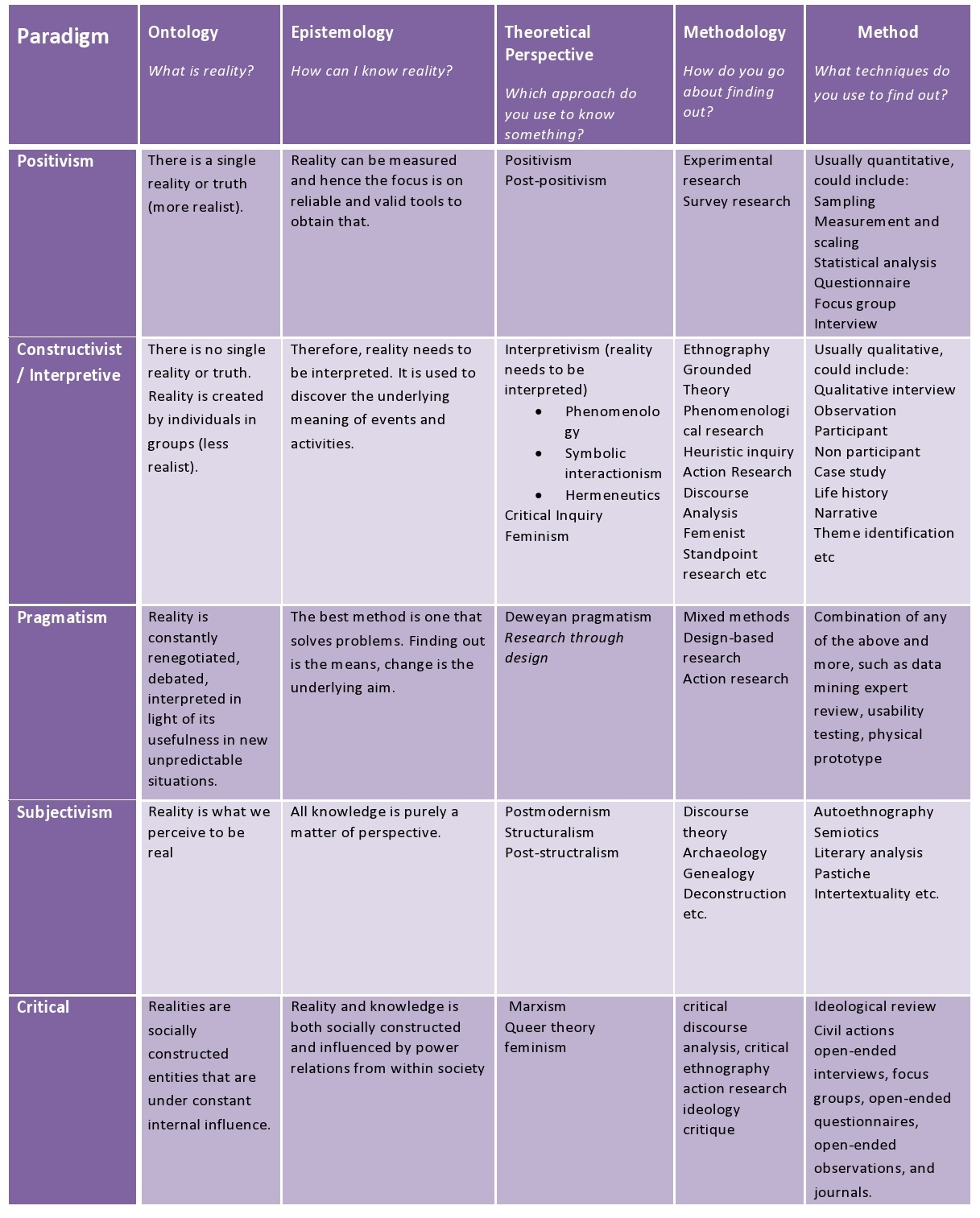

So, now you may be asking, what makes up a research paradigm ? How are they formed and categorized? The research paradigm framework is supported by three pillars: ontology, epistemology, and methodology. Some scholars have recently begun adding another pillar to research paradigms : ethics or axiology. However, this article will only discuss the three traditional aspects, which together define the research paradigm and provide the base on which to build your research project.

Ontology is the study of the nature of reality. Is there a single reality, multiple realities, or no reality at all? These are the questions that the philosophy of ontology attempts to answer. The oft-used example of an ontological question is “Does God exist?” Two possible single realities exist: yes or no.

Think about your research project with this in mind; that is, does a single reality exist within your research? If you’re a medical researcher, the answer is probably yes. You’re looking for specific results that ideally have clear yes or no answers. If you’re an anthropologist, there probably isn’t one clear, specific answer to your research question but multiple possible realities, and the study results are interpreted through the researcher’s viewpoint or paradigm.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge and how we can know reality. It incorporates the extent and ways to gain knowledge and how to validate that knowledge. A frequently used example question in epistemology is “How is it possible to know whether or not God exists?”

The epistemology of your research project will help determine your approach to your study. For example, if the medical researcher believes there is one singular truth, an objective approach will be taken. On the other hand, if the anthropologist believes in multiple realities viewed through a cultural lens, the research results will be more subjective and understood only in the proper context. This difference divides research studies into those using quantitative and qualitative techniques.

Methodology is the study of how one investigates the environment and validates the knowledge gained. It attempts to answer the question “how to go about discovering the answer/reality.” Addressing this pillar leads to specific data collection and analysis plans.

The medical researcher may create a research plan that includes a clinical trial, during which blood tests that measure a specific protein are conducted. These results are then analyzed, with a focus on differences within groups. The anthropologist, on the other hand, may conduct observations, examine artifacts, or set up interviews to determine certain aspects of reality within the context of a group’s culture. In this situation, yes or no answers are not sought but a truth is discovered.

What is the purpose of research paradigms ?

Put all the information about the three pillars of a research paradigm together, and you can see the purpose of research paradigms . Research paradigms establish the structure and foundation for a research project.

Once the research paradigm has been determined, an appropriate research plan can be created. The philosophical basis of the study guides what knowledge is sought, how that knowledge can be discovered, and how to form the collected information or data into the knowledge being sought. The research paradigm clearly outlines the path to investigate your topic. This brings clarity to your study and improves the quality of your methods and analysis.

In addition, it is important for researchers to understand how their own beliefs, assumptions, and biases can affect the research process. The study’s data collection, analysis, and interpretation will be impacted by the worldview of the researcher. Knowing the underlying research paradigm and how it frames the study allows researchers to better understand the effect of their perspective on the study results.

Types of research paradigms

As mentioned previously, there are two basic types of research paradigms , from which other frequently used paradigms are derived. This section will briefly describe these two major research paradigms .

Positivist paradigm – Proponents of a positivist paradigm believe that there is a single reality that can be measured and understood. Therefore, these researchers are likely to utilize quantitative methods in their studies. The research process for positivist paradigm studies tend to propose an empirical hypothesis, which is then supported or refuted through the data collection and analysis. Positivists approach research in an objective manner and statistically investigate the existence of quantitative relationships between variables instead of looking for the qualitative reason behind those relationships. Researchers who subscribe to this paradigm also believe that the results of one study can be generalized to similar situations. Positivist paradigms are most frequently used by physical scientists.

Interpretivism paradigm – Interpretivists believe in the existence of multiple realities rather than a single reality. This is the research paradigm used by the majority of qualitative studies conducted in the social sciences. Interpretivism holds that because human behavior is so complex, it cannot be studied by probabilistic models, such as those used under positivist paradigms . Knowledge can only be created by interpreting the meanings that people put on behaviors and events. Therefore, studies employing this framework are necessarily subjective and are greatly affected by the researcher’s personal viewpoint. Interpretivist paradigm research is conducted within the reality of those being studied, not in a contrived environment such as a laboratory. Because of the nature of interpretivist studies, their results are only valid under the particular circumstances of the study and are usually not generalizable.

Research paradigm examples

Positivist and interpretivist research paradigms , sometimes referred to as quantitative and qualitative paradigms, are the two major approaches to research. However, many other variations of these have been used. Following are brief descriptions of some of the more popular of these research paradigm variations.

Pragmatism paradigm – Pragmatists believe that reality is continually changing amid the flow of constantly changing situations. Therefore, rather than use a single research paradigm , they employ the framework that is most applicable to the research question they are examining. Both qualitative and quantitative techniques are often used as positivist and interpretivist approaches are combined. Pragmatists believe that the best research method is the one that will most effectively address the research question.

Constructivist paradigm – Like interpretivists, constructivists believe that there are numerous realities, not a single reality. The constructivist paradigm holds that people construct their own understanding of the world through experiencing and reflecting on those experiences. Constructivist research seeks to understand the meanings that people attach to those experiences. Therefore, qualitative techniques, such as interviews and case studies, are frequently used. Constructivists are seeking the “why” of events. Constructivism is also a popular theory of learning that focuses on how children and other learners create knowledge from their experiences and learn better through experimentation than through direct instruction.

Post-positivism paradigm – Post-positivists veer away from the concept of reality as being an absolute certainty and view it instead in a more probabilistic manner, thus taking a more subjective viewpoint. They believe that research outcomes can never be totally objective and a researcher’s worldview and biases can never be completely removed from the research results.

Transformative paradigm – Proponents of transformative research reject both positivism and interpretivism, believing that these frameworks do not accurately represent the experiences of marginalized communities. Transformative researchers generally use both qualitative and quantitative techniques to better understand the disparities in community relationships, support social justice, and ultimately ensure transformative change.

Combining research paradigms

While most research is based on either a positivist (quantitative) or interpretivist (qualitative) foundations, some studies combine both. For example, quantitative and qualitative techniques are frequently used together in psychology studies. These types of studies are referred to as mixed-method research. Some research paradigms are themselves combinations of other paradigms and frequently employ all the associated research methods. Post-positivism combines the paradigms of positivism and interpretivism.

5 steps to a paradigm shift

Research studies aren’t the only things that can be considered to have paradigms. Researchers themselves bring a specific worldview to their work and produce higher quality work when they are aware of the effect their perspective has on their results. Understanding all the aspects of a personal paradigm, including beliefs, habits, and behaviors, can make it possible for that paradigm to be changed. Here are suggested steps to successfully shift your personal paradigm and increase the quality of your research 2 .

- Identify the paradigm element you want to change – what part of your worldview do you want to change? What habitual or hidden behavior may be adversely affecting your research or your life?

- Write down your goals – setting specific desired outcomes and putting them down on paper sets them in your subconscious.

- Adjust your mindset – intentionally influencing your thoughts to support your goals can motivate you to create the change you want. Some suggested activities to help with this include journaling, reading motivational books, and spending time with like-minded people.

- Do uncomfortable things – you need to get out of your comfort zone to effect real change. This will get your subconscious out of its usual habits and move you toward your goal.

- Practice being who you want to be – the change you want will become solidified and part of your new paradigm once you break out of your old habit and keep repeating the new behavior so as to cement it in your subconscious.

References:

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/paradigm [Accessed March 10, 2023]

- What is research paradigm – explanation and examples. Peachy Essay. https://peachyessay.com/blogs/what-is-research-paradigm/ [Accessed March 10, 2023]

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

The Four Types of Research Paradigms: A Comprehensive Guide

5-minute read

- 22nd January 2023

In this guide, you’ll learn all about the four research paradigms and how to choose the right one for your research.

Introduction to Research Paradigms

A paradigm is a system of beliefs, ideas, values, or habits that form the basis for a way of thinking about the world. Therefore, a research paradigm is an approach, model, or framework from which to conduct research. The research paradigm helps you to form a research philosophy, which in turn informs your research methodology.

Your research methodology is essentially the “how” of your research – how you design your study to not only accomplish your research’s aims and objectives but also to ensure your results are reliable and valid. Choosing the correct research paradigm is crucial because it provides a logical structure for conducting your research and improves the quality of your work, assuming it’s followed correctly.

Three Pillars: Ontology, Epistemology, and Methodology

Before we jump into the four types of research paradigms, we need to consider the three pillars of a research paradigm.

Ontology addresses the question, “What is reality?” It’s the study of being. This pillar is about finding out what you seek to research. What do you aim to examine?

Epistemology is the study of knowledge. It asks, “How is knowledge gathered and from what sources?”

Methodology involves the system in which you choose to investigate, measure, and analyze your research’s aims and objectives. It answers the “how” questions.

Let’s now take a look at the different research paradigms.

1. Positivist Research Paradigm

The positivist research paradigm assumes that there is one objective reality, and people can know this reality and accurately describe and explain it. Positivists rely on their observations through their senses to gain knowledge of their surroundings.

In this singular objective reality, researchers can compare their claims and ascertain the truth. This means researchers are limited to data collection and interpretations from an objective viewpoint. As a result, positivists usually use quantitative methodologies in their research (e.g., statistics, social surveys, and structured questionnaires).

This research paradigm is mostly used in natural sciences, physical sciences, or whenever large sample sizes are being used.

2. Interpretivist Research Paradigm

Interpretivists believe that different people in society experience and understand reality in different ways – while there may be only “one” reality, everyone interprets it according to their own view. They also believe that all research is influenced and shaped by researchers’ worldviews and theories.

As a result, interpretivists use qualitative methods and techniques to conduct their research. This includes interviews, focus groups, observations of a phenomenon, or collecting documentation on a phenomenon (e.g., newspaper articles, reports, or information from websites).

3. Critical Theory Research Paradigm

The critical theory paradigm asserts that social science can never be 100% objective or value-free. This paradigm is focused on enacting social change through scientific investigation. Critical theorists question knowledge and procedures and acknowledge how power is used (or abused) in the phenomena or systems they’re investigating.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Researchers using this paradigm are more often than not aiming to create a more just, egalitarian society in which individual and collective freedoms are secure. Both quantitative and qualitative methods can be used with this paradigm.

4. Constructivist Research Paradigm

Constructivism asserts that reality is a construct of our minds ; therefore, reality is subjective. Constructivists believe that all knowledge comes from our experiences and reflections on those experiences and oppose the idea that there is a single methodology to generate knowledge.

This paradigm is mostly associated with qualitative research approaches due to its focus on experiences and subjectivity. The researcher focuses on participants’ experiences as well as their own.

Choosing the Right Research Paradigm for Your Study

Once you have a comprehensive understanding of each paradigm, you’re faced with a big question: which paradigm should you choose? The answer to this will set the course of your research and determine its success, findings, and results.

To start, you need to identify your research problem, research objectives , and hypothesis . This will help you to establish what you want to accomplish or understand from your research and the path you need to take to achieve this.

You can begin this process by asking yourself some questions:

- What is the nature of your research problem (i.e., quantitative or qualitative)?

- How can you acquire the knowledge you need and communicate it to others? For example, is this knowledge already available in other forms (e.g., documents) and do you need to gain it by gathering or observing other people’s experiences or by experiencing it personally?

- What is the nature of the reality that you want to study? Is it objective or subjective?

Depending on the problem and objective, other questions may arise during this process that lead you to a suitable paradigm. Ultimately, you must be able to state, explain, and justify the research paradigm you select for your research and be prepared to include this in your dissertation’s methodology and design section.

Using Two Paradigms

If the nature of your research problem and objectives involves both quantitative and qualitative aspects, then you might consider using two paradigms or a mixed methods approach . In this, one paradigm is used to frame the qualitative aspects of the study and another for the quantitative aspects. This is acceptable, although you will be tasked with explaining your rationale for using both of these paradigms in your research.

Choosing the right research paradigm for your research can seem like an insurmountable task. It requires you to:

● Have a comprehensive understanding of the paradigms,

● Identify your research problem, objectives, and hypothesis, and

● Be able to state, explain, and justify the paradigm you select in your methodology and design section.

Although conducting your research and putting your dissertation together is no easy task, proofreading it can be! Our experts are here to make your writing shine. Your first 500 words are free !

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

Free email newsletter template (2024).

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Research Paradigm: An Introduction with Examples

This article provides a detailed and easy-to-understand introduction to research paradigms, including examples.

If you are considering writing a research paper, you should be aware that you must set criteria for constructing the approach you will use as a methodology in your work, which is why you must comprehend the concept of the research paradigm .

A research paradigm , in simplest terms, is the process of constructing a research plan that can assist you in quickly understanding how the theories and practices of your research project work.

The purpose of this article is to introduce you to research paradigms and explain them to you in the most descriptive way possible using examples.

What is a research paradigm?

A research paradigm is a method, model, or pattern for conducting research. It is a set of ideas, beliefs, or understandings within which theories and practices can function. The majority of paradigms derive from one of two research methodologies: positivism or interpretivism . Every research project employs one of the research paradigms as a guideline for creating research methods and carrying out the research project most legitimately and reasonably.

Though there were essentially two paradigms, various new paradigms have arisen from these two, particularly in social science research. Keep in mind that selecting one of the paradigms for your research project demands a thorough understanding of the unique characteristics of each approach.

What are the 3 paradigms of research?

To select the best research paradigm for your project, you must first comprehend the three pillars: ontology, epistemology, and methodology.

Ontology is a philosophical theory regarding the nature of reality, asserts that there is either a single reality or none at all. To be more specific, ontology answers the question, “ What is reality? ”

Epistemology

Epistemology is the study of knowledge, focusing on the validity, extent, and ways of gaining knowledge. Epistemology seeks to address the question, “ How can we know reality? “

Methodology

Methodology refers to general concepts that underpin how one explores the social environment and proves the validity of the knowledge gained. The methodological question is “ How to go about discovering the reality/answer? “

What is the purpose of a research paradigm?

The importance of choosing a paradigm for a research project stems from the fact that it establishes the foundation for the study’s research and its methodologies.

A paradigm investigates how knowledge is understood and researched, and it explicitly outlines the objective, motivation, and expected outcomes of the research.

The proper implementation of a research paradigm in research provides researchers with a clear path to examine the topic of interest.

As a result, it gives a logical and deliberate structure for carrying it out, besides improving the quality of your work and your proficiency.

Research paradigms examples

Now that you understand the three pillars and the importance of the research paradigm, let’s look at some examples of paradigms that you may use in your research.

Positivist Paradigm

Positivists believe in a single reality that can be measured and understood. As a result, quantitative approaches are utilized to quantify this reality.

Positivism in research is a philosophy related to the concept of real inquiry. A positivism-based research philosophy employs a rigorous approach to the systematic study of data sources.

Interpretivism or Constructivism Paradigm

The interpretivism approach is used in the majority of qualitative research conducted in the social sciences; it is predicated on the existence of numerous realities rather than a single reality.

According to interpretivists, human behavior is complex and cannot be predicted by predefined probability.

Human behavior is not like a scientific variable that can be easily controlled. The word interpretivism refers to methods of gaining knowledge of the universe that rely on interpreting or comprehending the meanings that humans attach to their behaviors.

Pragmatism Paradigm

The research question determines pragmatism. Depending on the nature of the research issue, pragmatics may incorporate both positivism and interpretivism approaches within a single study.

It is a problem-solving philosophy that maintains that the best research techniques are those that contribute to the most effective answer to the research issue. This is followed by an examination of many aspects of a research problem using a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Postpositivism Paradigm

The positivism paradigm gave way to the postpositivism paradigm, which is more concerned with the subjectivity of reality and departs from the logical positivists’ objective perspective.

Postpositivism seeks objective answers by striving to recognize and deal with such biases in the ideas and knowledge developed by researchers.

Build a graphical abstract that perfectly represents your findings

Graphic abstracts are becoming significantly important. But where to begin? How should you go about creating the appropriate graphical abstract for your article?

Mind The Graph is the ideal tool for this; utilize templates to easily create the most qualified graphical abstract for your target audience.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

Research Philosophy & Paradigms

Positivism, Interpretivism & Pragmatism, Explained Simply

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Research philosophy is one of those things that students tend to either gloss over or become utterly confused by when undertaking formal academic research for the first time. And understandably so – it’s all rather fluffy and conceptual. However, understanding the philosophical underpinnings of your research is genuinely important as it directly impacts how you develop your research methodology.

In this post, we’ll explain what research philosophy is , what the main research paradigms are and how these play out in the real world, using loads of practical examples . To keep this all as digestible as possible, we are admittedly going to simplify things somewhat and we’re not going to dive into the finer details such as ontology, epistemology and axiology (we’ll save those brain benders for another post!). Nevertheless, this post should set you up with a solid foundational understanding of what research philosophy and research paradigms are, and what they mean for your project.

Overview: Research Philosophy

- What is a research philosophy or paradigm ?

- Positivism 101

- Interpretivism 101

- Pragmatism 101

- Choosing your research philosophy

What is a research philosophy or paradigm?

Research philosophy and research paradigm are terms that tend to be used pretty loosely, even interchangeably. Broadly speaking, they both refer to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study (whether that’s a dissertation, thesis or any other sort of academic research project).

For example, one philosophical assumption could be that there is an external reality that exists independent of our perceptions (i.e., an objective reality), whereas an alternative assumption could be that reality is constructed by the observer (i.e., a subjective reality). Naturally, these assumptions have quite an impact on how you approach your study (more on this later…).

The research philosophy and research paradigm also encapsulate the nature of the knowledge that you seek to obtain by undertaking your study. In other words, your philosophy reflects what sort of knowledge and insight you believe you can realistically gain by undertaking your research project. For example, you might expect to find a concrete, absolute type of answer to your research question , or you might anticipate that things will turn out to be more nuanced and less directly calculable and measurable . Put another way, it’s about whether you expect “hard”, clean answers or softer, more opaque ones.

So, what’s the difference between research philosophy and paradigm?

Well, it depends on who you ask. Different textbooks will present slightly different definitions, with some saying that philosophy is about the researcher themselves while the paradigm is about the approach to the study . Others will use the two terms interchangeably. And others will say that the research philosophy is the top-level category and paradigms are the pre-packaged combinations of philosophical assumptions and expectations.

To keep things simple in this video, we’ll avoid getting tangled up in the terminology and rather focus on the shared focus of both these terms – that is that they both describe (or at least involve) the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study .

Importantly, your research philosophy and/or paradigm form the foundation of your study . More specifically, they will have a direct influence on your research methodology , including your research design , the data collection and analysis techniques you adopt, and of course, how you interpret your results. So, it’s important to understand the philosophy that underlies your research to ensure that the rest of your methodological decisions are well-aligned .

So, what are the options?

We’ll be straight with you – research philosophy is a rabbit hole (as with anything philosophy-related) and, as a result, there are many different approaches (or paradigms) you can take, each with its own perspective on the nature of reality and knowledge . To keep things simple though, we’ll focus on the “big three”, namely positivism , interpretivism and pragmatism . Understanding these three is a solid starting point and, in many cases, will be all you need.

Paradigm 1: Positivism

When you think positivism, think hard sciences – physics, biology, astronomy, etc. Simply put, positivism is rooted in the belief that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements . In other words, the positivist philosophy assumes that answers can be found by carefully measuring and analysing data, particularly numerical data .

As a research paradigm, positivism typically manifests in methodologies that make use of quantitative data , and oftentimes (but not always) adopt experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Quite often, the focus is on causal relationships – in other words, understanding which variables affect other variables, in what way and to what extent. As a result, studies with a positivist research philosophy typically aim for objectivity, generalisability and replicability of findings.

Let’s look at an example of positivism to make things a little more tangible.

Assume you wanted to investigate the relationship between a particular dietary supplement and weight loss. In this case, you could design a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where you assign participants to either a control group (who do not receive the supplement) or an intervention group (who do receive the supplement). With this design in place, you could measure each participant’s weight before and after the study and then use various quantitative analysis methods to assess whether there’s a statistically significant difference in weight loss between the two groups. By doing so, you could infer a causal relationship between the dietary supplement and weight loss, based on objective measurements and rigorous experimental design.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that knowledge and insight can be obtained through carefully controlling the environment, manipulating variables and analysing the resulting numerical data . Therefore, this sort of study would adopt a positivistic research philosophy. This is quite common for studies within the hard sciences – so much so that research philosophy is often just assumed to be positivistic and there’s no discussion of it within the methodology section of a dissertation or thesis.

Paradigm 2: Interpretivism

If you can imagine a spectrum of research paradigms, interpretivism would sit more or less on the opposite side of the spectrum from positivism. Essentially, interpretivism takes the position that reality is socially constructed . In other words, that reality is subjective , and is constructed by the observer through their experience of it , rather than being independent of the observer (which, if you recall, is what positivism assumes).

The interpretivist paradigm typically underlies studies where the research aims involve attempting to understand the meanings and interpretations that people assign to their experiences. An interpretivistic philosophy also typically manifests in the adoption of a qualitative methodology , relying on data collection methods such as interviews , observations , and textual analysis . These types of studies commonly explore complex social phenomena and individual perspectives, which are naturally more subjective and nuanced.

Let’s look at an example of the interpretivist approach in action:

Assume that you’re interested in understanding the experiences of individuals suffering from chronic pain. In this case, you might conduct in-depth interviews with a group of participants and ask open-ended questions about their pain, its impact on their lives, coping strategies, and their overall experience and perceptions of living with pain. You would then transcribe those interviews and analyse the transcripts, using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns. Based on that analysis, you’d be able to better understand the experiences of these individuals, thereby satisfying your original research aim.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that insight can be obtained through engaging in conversation with and exploring the subjective experiences of people (as opposed to collecting numerical data and trying to measure and calculate it). Therefore, this sort of study would adopt an interpretivistic research philosophy. Ultimately, if you’re looking to understand people’s lived experiences , you have to operate on the assumption that knowledge can be generated by exploring people’s viewpoints, as subjective as they may be.

Paradigm 3: Pragmatism

Now that we’ve looked at the two opposing ends of the research philosophy spectrum – positivism and interpretivism, you can probably see that both of the positions have their merits , and that they both function as tools for different jobs . More specifically, they lend themselves to different types of research aims, objectives and research questions . But what happens when your study doesn’t fall into a clear-cut category and involves exploring both “hard” and “soft” phenomena? Enter pragmatism…

As the name suggests, pragmatism takes a more practical and flexible approach, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings , rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position. This allows you, as the researcher, to explore research aims that cross philosophical boundaries, using different perspectives for different aspects of the study .

With a pragmatic research paradigm, both quantitative and qualitative methods can play a part, depending on the research questions and the context of the study. This often manifests in studies that adopt a mixed-method approach , utilising a combination of different data types and analysis methods. Ultimately, the pragmatist adopts a problem-solving mindset , seeking practical ways to achieve diverse research aims.

Let’s look at an example of pragmatism in action:

Imagine that you want to investigate the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes. In this case, you might adopt a mixed-methods approach, which makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques. One part of your project could involve comparing standardised test results from an intervention group (students that received the new teaching method) and a control group (students that received the traditional teaching method). Additionally, you might conduct in-person interviews with a smaller group of students from both groups, to gather qualitative data on their perceptions and preferences regarding the respective teaching methods.

As you can see in this example, the pragmatist’s approach can incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data . This allows the researcher to develop a more holistic, comprehensive understanding of the teaching method’s efficacy and practical implications , with a synthesis of both types of data . Naturally, this type of insight is incredibly valuable in this case, as it’s essential to understand not just the impact of the teaching method on test results, but also on the students themselves!

Wrapping Up: Philosophies & Paradigms

Now that we’ve unpacked the “big three” research philosophies or paradigms – positivism, interpretivism and pragmatism, hopefully, you can see that research philosophy underlies all of the methodological decisions you’ll make in your study. In many ways, it’s less a case of you choosing your research philosophy and more a case of it choosing you (or at least, being revealed to you), based on the nature of your research aims and research questions .

- Research philosophies and paradigms encapsulate the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that guide the way you, as the researcher, approach your study and develop your methodology.

- Positivism is rooted in the belief that reality is independent of the observer, and consequently, that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements.

- Interpretivism takes the (opposing) position that reality is subjectively constructed by the observer through their experience of it, rather than being an independent thing.

- Pragmatism attempts to find a middle ground, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings, rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position.

If you’d like to learn more about research philosophy, research paradigms and research methodology more generally, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your research, consider our private coaching service , where we guide you through each stage of the research journey, step by step.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

21 Comments

was very useful for me, I had no idea what a philosophy is, and what type of philosophy of my study. thank you

Thanks for this explanation, is so good for me

You contributed much to my master thesis development and I wish to have again your support for PhD program through research.

the way of you explanation very good keep it up/continuous just like this

Very precise stuff. It has been of great use to me. It has greatly helped me to sharpen my PhD research project!

Very clear and very helpful explanation above. I have clearly understand the explanation.

Very clear and useful. Thanks

Thanks so much for your insightful explanations of the research philosophies that confuse me

I would like to thank Grad Coach TV or Youtube organizers and presenters. Since then, I have been able to learn a lot by finding very informative posts from them.

thank you so much for this valuable and explicit explanation,cheers

Hey, at last i have gained insight on which philosophy to use as i had little understanding on their applicability to my current research. Thanks

Tremendously useful

thank you and God bless you. This was very helpful, I had no understanding before this.

USEFULL IN DEED!

Explanations to the research paradigm has been easy to follow. Well understood and made my life easy.

Very useful content. This will make my research life easy.

The explanation is very efficacy to those who were still not understanding the research philosophy. Very clear explanations on the types of research paradigms.

The explanation is very efficacy to those who were still not understanding the research philosophy.

thank you for this informative page.

thank you:)

Very well explained.I am grateful for the understanding I gained from this scholarly writeup.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Med Sci Educ

- v.30(1); 2020 Mar

A Medical Science Educator’s Guide to Selecting a Research Paradigm: Building a Basis for Better Research

Megan e.l. brown.

Health Professions Education Unit, Hull York Medical School, John Hughlings Jackson Building, University Road, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD UK

Angelique N. Dueñas

A research paradigm, or set of common beliefs about research, should be a key facet of any research project. However, despite its importance, there is a paucity of general understanding in the medical sciences education community regarding what a research paradigm consists of and how to best construct one. With the move within medical sciences education towards greater methodological rigor, it is now more important than ever for all educators to understand simply how to better approach their research via paradigms. In this monograph, a simplified approach to selecting an appropriate research paradigm is outlined. Suggestions are based on broad literature, medical education sources, and the author’s own experiences in solidifying and communicating their research paradigms. By assisting in detailing the philosophical underpinnings of individuals research approaches, this guide aims to help all researchers improve the rigor of their projects and improve upon overall understanding in research communication.

Introduction

There has been a recent movement within medical education towards greater methodological rigor [ 1 , 2 ]. Many scholars argue that in order to achieve “academic legitimacy” [ 3 ] strong theoretical frameworks [ 4 , 5 ] engaging in discussion concerning the nature of knowledge within a piece of work are required [ 6 ]. Put simply, clear research principles assist others in understanding your research.

The nature of knowledge within a piece of work is detailed and explored within a research project’s paradigm . A research paradigm may be defined as “the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed” [ 7 ]. A paradigm is an assumption about how things work, sometimes illustrated as a “worldview” involving “shared understandings of reality” [ 8 , 9 ]. Detailing one’s research paradigm is essential, as paradigms “guide how problems are solved” [ 10 ], and directly influence an author’s choice of methods. All researchers make assumptions about the state of the world before undertaking research. Regardless of whether that research is quantitative or qualitative, these assumptions are important as they impact upon the interpretation of a study’s results. Mitroff and Bonoma summarize this position and put forth “the power of an experiment is only as strong as the clarity of the basic assumptions which underlie it. Such assumptions not only underlie laboratory experimentation but social… research as well” [ 11 ]. Paradigms also assist in setting ground rules for the application of theory when observing phenomena. Such ground rules “set the scene” for research, providing information as to how best evaluate new concepts [ 7 ].

Medicine and, as a consequence, health professions education, has traditionally been conducted from a positivist or post-positivist paradigm, detailed later in this paper, both of which maintain a universal truth exists, as, “in medicine, the emphasis on… body parts, conditions and treatments assumes that these are universally constant replicable facts” [ 12 ]. Given the dominance of this belief, there has been a relative dearth of literature within medical sciences education explicitly detailing paradigmatic assumptions. This is changing, with an increasingly widespread recognition of the important role assumptions play in result interpretation and in setting ground rules, both in research and in classrooms [ 13 , 14 ]. As such, explicitly acknowledging one’s paradigm is becoming an expected element of medical science education research.

In order to detail your work’s paradigm, it is important to consider what a paradigm consists of. The paradigm of a piece of work is constructed of several “building blocks,” detailed in Fig. 1 . The first set of these building blocks (axiology, ontology, epistemology, methodology) are composed of philosophical assumptions that “direct thinking and action” such as selecting one’s methods [ 16 ].

The building blocks forming a piece of work’s research paradigm and how they interrelate. Image is an adapted version of Grix’s paradigmatic building blocks [ 15 ]. Image adapted by authors to include axiology as an important block not originally detailed

Axiology, the first “brick” in the construction of a project’s paradigm involves the study of value and ethics [ 17 ]. Once an area of value to study has been identified, and research ethics considered, ontology, which questions “the nature of reality” [ 3 ] must be contemplated. Once you possess a firm philosophical understanding of your study area’s reality, the nature of knowledge within that reality needs determining—this is known as the epistemology of a piece of work.

Frank discussion of a work’s ontology and epistemology allows an appropriate methodological approach to be selected and reduces the ambiguity surrounding result interpretation [ 18 ]. Without such regulation “even carefully collected results can be misleading” as the “underlying context of assumptions” is unclear [ 19 ]. This monograph will detail a series of considerations, forming a how-to guide, for selecting an appropriate paradigm for your medical sciences education research.

Select your Research Paradigm Before You Begin Researching

Given that paradigms inform the design of, and fundamentally underpin, both quantitative and qualitative research, it is important to select your paradigm before you begin researching. Teherani et al. emphasize the need for this nicely: “alignment between the belief system underpinning the research approach, the research question, and the research approach itself is a prerequisite for rigorous… research” [ 20 ]. Such alignment can only be assured prospectively.

One frequently cited argument for not considering the research paradigm of a piece of work is the time-consuming nature of this process. Admittedly, selecting a research paradigm does (and should if done well) take time. Ensure you factor this consideration into your plans when drafting a timeline for your research project. It is difficult to provide guidance on how much time one should spend selecting a research paradigm as, depending upon the project in question and research team, this may vary. We recommend threading consideration of your research paradigm into the “design” phase of your research. Using the present work will also contribute to reducing the time-consuming aspect of this work; for many novices, approaching the language and process of paradigms can prove daunting and take time. However, this work is designed to ease that process.

Try Thinking About Research Paradigms Using the Metaphor of a Glass Box

Research paradigms can seem overwhelming—indeed, even experienced academics may struggle to distinguish between the various building blocks constituting a paradigm. Thinking of one’s research paradigm using the metaphor of a glass box, as described by Varpio [ 21 ], may assist in better visualizing and understanding the constituent elements of a paradigm. Using this metaphor, your paradigm is the glass box in which you stand, framing how you see the outside world. One’s beliefs regarding the ontology and epistemology of knowledge color the glass box in different ways, lending different lights to the same situation for different individuals. Given this, you may research a topic using a different approach to your colleague within the same area.

Think About your Reason for Carrying Out the Research

This may seem like an obvious consideration, but it is an area that is often not consciously reflected upon within medical science education research. What is your motivation to study this topic? Have you been practically, academically, or politically motivated? In other words, is it something you have noticed in your day to day work that requires further study; are you simply passionate to know more; or is there a political “hot topic” you or others are interested in researching?

Building upon your initial thoughts regarding your motivation, try to reflect more deeply regarding what you are really trying to achieve. Chilisa compares different paradigmatic reasons for doing research, as can be seen in Table Table1 1 [ 23 ]. Thinking of your own reason for doing research and comparing this with Chilisa’s reasons should begin to cast light on which paradigm may be an appropriate choice for your research.

Adapted from Chilisa’s comparison of paradigmatic reasons for doing research [ 22 ]

| Paradigm | Positivist and post-positivist | Constructivist | Critical theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for doing the research | To discover laws that are generalizable and govern the universe | To understand and describe human nature | To destroy myths and empower people to change society radically |

Consider your Axiological Approach

The next step in the consideration of an appropriate paradigm for your research is reflecting upon your axiological approach. Traditionally, Guba and Lincoln describe a paradigm as involving three building blocks: ontology, epistemology, and methodology [ 24 ]. However, there has been a move towards including axiology as a fourth defining characteristic of a paradigm [ 25 ]. Axiology involves ethical considerations and “asks what ought to be” within a field of research [ 26 ]. It is an important starting point for any proposed research, as it considers what would be of value to research and how to go about conducting ethical research within that area [ 27 ]. Given this, we modified Grix’s paradigmatic building blocks [ 15 ] to include axiology as a key early consideration in paradigm selection (Fig. (Fig.1 1 ).

Considering your axiological approach is best done in a designated reflective space with all members of your research team during the planning phase of a research proposal. Building on considering your purpose in doing research, you must consider the personal values informing your proposal. Ask yourself the following:

- Why is this research worth my time and attention?

- What motivates me? Am I driven by imperatives (e.g. funding, social justice)?

- Or, do I believe education to be inherently valuable, providing justification for any research that informs educational practice? [ 28 ]

Once the values underpinning your inquiry are clear and it is evident your research is justified, potential ethical issues should also be considered. For example, if your axiological reflection reveals you are being driven by an external motivator, it may be appropriate to disclose this within your research design. Most journals mandate inclusion of detail regarding any funding underpinning your research and any conflicts of interest (which could include sources of personal funding). Kirkman et al. include a detailed “competing interests” statement in their systematic review evaluating the outcomes of recent patient safety interventions for junior doctors and medical students [ 29 ]. Particularly relevant are two author’s affiliations with the General Medical Council (GMC), the UK’s regulatory body for physicians, and consultancy work several authors had undertaken previously on the topic of patient safety for a variety of institutions. These institutional affiliations could color the author’s perspectives and interpretations in tacit ways, in line with institutional values. As such, considering any such competing interests or associations within your team’s axiological reflection is the key.

Reflect upon your Ontological Assumptions

We all hold ontological assumptions, even if we do not explicitly consider or detail them. Reflecting upon them allows you to choose a paradigm in keeping with your beliefs regarding the nature of reality [ 3 ]. Reality refers to the social world in which you wish to conduct your research [ 22 ].

Different paradigms adopt different approaches to defining the nature of reality. There are many paradigms research may operate within, with some scholars even attempting to define new, albeit contested, paradigms within the social sciences in recent years [ 30 ]. Given this, detailing the ontology of every available paradigm is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, we will focus upon the four paradigms most commonly used within general medical education [ 3 ]: positivism, post-positivism, constructivism/interpretivism, and critical theory.

To assess your ontological assumptions, ask yourself this: do you believe there is “one verifiable reality,” or that “multiple socially constructed realities” exist? [ 21 , 31 ] The former stance is sometimes referred to as a “realist” ontological position, with the latter stance known as “anti-realism” or “relativism” [ 32 ]. Broadly speaking, the four paradigms most commonly used within medical education fall into either of these two categories, but there are differences in how they frame their position, detailed in Table Table2 2 .

Ontological assumptions of positivism, post-positivism, constructivism/interpretivism, and critical theory [ 30 , 33 – 39 ]

| Paradigm | Positivist | Post-positivist | Constructivist/interpretivist | Critical theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontological assumptions | There is a single, objective reality that can be observed through science. | There is a single, objective reality. However, scientific observations involve error so reality can only be known imperfectly. | There are multiple subjective realities, each of which is socially constructed by and between individuals. | There are multiple subjective realities influenced by power relations in society. Reality is shaped by social, political, cultural, economic, ethnic, and gender values. |

Reflect upon your Epistemological Assumptions

Once you are aware of your assumptions regarding the nature of reality, reflecting upon your epistemological assumptions regarding the nature of knowledge is necessary. When considering your research epistemology, it may be useful to reflect upon “what counts as knowledge within the world” [ 40 ]. Epistemology seeks to answer two questions—one, what is knowledge , and two, how is knowledge acquired ? [ 41 ].

Again, the epistemological approaches of positivism, post-positivism, constructivism, and critical theory differ. These are outlined within Table Table3 3 .

Epistemological assumptions of positivism, post-positivism, constructivism/interpretivism, and critical theory [ 27 , 34 ]

| Paradigm | Positivist | Post-positivist | Constructivist/interpretivist | Critical theory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistemological assumptions | Neutral knowledge can be obtained through the use of reliable and valid measurement tools. | Obtaining knowledge is subject to human error. Therefore, human knowledge is imperfect and only “probable” truths can be established. | Knowledge is subjective and formed at an individual level. | Knowledge is also subjective, but created and negotiated between individuals and within groups. |

Become Familiar with Different Types of Paradigm to Evaluate Where You and Your Work Fit

Above, we have focused on positivism, post-positivism, constructivism, and critical theory as four common paradigms in medical education [ 37 ]. These are only a subset of paradigms that might align with an individual’s medical education research aims [ 42 ]. We recommend researchers to familiarize themselves with as many different types of paradigms as possible, to best understand where you as a researcher, but also your team and project fit.

Given the complexity of paradigms, rather than delving too deeply into the nuances of philosophy associated with paradigms, seeking simple infographics and metaphors can make exploration more manageable. We have already introduced some simple tables and the glass house metaphor [ 21 ], but you may find it helpful to seek other visualizations, such as the

“research onion” [ 43 , 44 ]. In brief, the “research onion” depicts paradigmatic considerations as layers, in lieu of building blocks or glass walls.

Another helpful way to explore paradigms is to be mindful of such in your own reviews of literature. Are authors explicitly discussing their paradigms? If so, do you agree? If not, how would you categorize their paradigm based on their study details? Zaidi and Larsen provide an excellent commentary where they categorize papers based on research paradigms, using their own interpretations [ 45 ]. Such an activity may prove useful to those wishing to improve their understanding of paradigms, in a practical fashion.

Use your Chosen Paradigm to Select an Appropriate Methodology

How you can go about “acquiring” knowledge, so that it aligns naturally with your paradigm, might be considered next. For example, if an individual is a strict positivist, believing that there are single truths, and that such truths can be measured, you would expect them to utilize stricter forms of experimental research, with explicit hypothesis testing. Different methodologies align best with different paradigms [ 46 ].

Consideration of research teams’ methodologies can also be helpful in understanding your paradigm, prior to moving forward with research projects. Following the example above, if your research team most often utilizes experimental design in your projects, what might this say about your regard for what knowledge and information you place value in?

Examine your Methodology in Order to Select an Appropriate Data Gathering Technique

Too often, methodology and methods are used interchangeably by novice researchers, when they should be regarded as distinct concepts [ 47 ]. Methodology is the strategy or overall plan to acquire knowledge, and methods are the actual techniques used to gather and analyze data [ 33 ].

For example, a research team interested in examining interprofessionalism in a healthcare setting may identify most with a constructivist paradigm, believing reality is subjectively constructed by individuals. Such a team might consider ethnography to be an appropriate methodology. But the actual research methods they undertake might be a variety of observations with field notes, audio or video recordings, or qualitative interviews [ 48 ]. These methods align with the methodology, although eventual selection of methods may also be highly associated with the practicality of such techniques, in addition to paradigm considerations.

The above sections have provided an overview of the “building blocks” of a research project’s paradigm. For ease of reference, these building blocks are summarized for the four main paradigms used within medical science education, in Fig. Fig.2 2 [ 30 , 36 , 49 , 50 ].

The building blocks of a research project’s paradigm within the four main medical science education paradigms summarized. Each shape in the figure refers to one of the four main medical science paradigms. Each color refers to an element of a piece of research’s paradigm. Please see the key to this figure to aid with interpretation

Clearly Detail Your Paradigm and its Building Blocks When You Write about your Research

A paradigm does no good if it only exists in the mind of the researcher and is not clearly communicated. Clearly detail your paradigm, for your own understanding as a researcher. It is often helpful to describe your paradigm by answering the questions outlined in the building blocks, as shown in Fig. Fig.1 1 .

But also keep in mind to make any details of your paradigm accessible and understandable for your target audience when disseminating your research. Depending on the scope and goals of your research, description of your paradigm could range from a paragraph or two in a research report designed for publication, to a multipage subchapter of a larger report or thesis assignment. In either case, writing about the paradigm is key for the audience to understand the context of your research, although the level of detail in which you communicate your paradigm may vary.

Locating accessible literature to draw upon when writing about your paradigm can prove difficult. The field is littered with philosophical jargon that can act as a barrier to entry into the world of paradigms, as earlier addressed in time consideration of paradigm selection. We hope this guide will assist you in beginning to understand some of the foundational terms within this field. If you are interested and have time, there is a wealth of literature within the field of “Philosophy of Science” that explicitly discusses the nature of knowledge and varying paradigmatic stances. Some seminal texts include The Foundations of Social Research [ 36 ], The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [ 7 ], Bruno Latour: Hybrid thoughts in a Hybrid world [ 51 ], and The Paradigm Dialog [ 52 ].

Several introductory textbooks and articles offer integrated summaries of these seminal texts including, but not limited to Kivunja and Kuyini’s “Understanding and Applying Research Paradigms in Educational Contexts” [ 53 ]; Avramidis and Smith’s “An introduction to the major research paradigms and their methodological implications for special needs research” [ 54 ]; Denzin and Lincoln’s The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research [ 55 ]; and Philosophy of Science: A Very Short Introduction [ 56 ].

Move from Philosophy to Practicality

For those involved in the day-to-day aspects of healthcare teaching, many times one of the first questions that comes to mind around the philosophical underpinnings of research is: how can this be practically applied to my work? Beyond improving rigor and understanding, as thoroughly discussed, there are two key ways to approach the practical side of research: from the before and the after.

Considering the practical problems and questions you face as a medical sciences educator, then considering how different paradigms could be used to approach problems in different ways, is a practical “before” way to consider paradigms. To elucidate the ways in which real-world problems can be approached from a paradigm-informed perspective, we’ve included some examples in Fig. Fig.3. 3 . For somevarious real-world examples, at different educational levels, we have provided some different examples of research approaches, that would naturally align with different paradigms.

Examples of real-world educational scenarios at a macro-, mid-, and microlevel and how consideration of different paradigms could be aligned to varying research aims and processes

From the “after” research perspective, praxeology is the last -ology you may wish to reflect upon. Concerned with the more practical recommendations that often arise from research, praxeology is concerned with not just understanding human actions, but interpreting them in meaningful ways [ 45 ]. If your research has contributed to “knowledge,” what does this mean for your day-to-day role as a medical sciences educator? In this way, practicality can be also important after the research process. Using the mid-level example from Fig. 2 , if you completed research from a constructivist approach, you may have discovered that self-guided methods in virtual histology labs was not leading to a conducive learning environment. This may lead to your decision to create video guides to accompany virtual histology resources, so students have instructor-led examples to initially guide their learning.

In addition to the above ways of practically approaching paradigms, researchers may also wish to contemplate the practical paradigm of pragmatism. Pragmatism focuses on research outcomes and, as such, does not place value on considering either epistemology or ontology. Instead, pragmatism strives to focus on what works best for understanding and solving problems [ 57 ]. Pragmatists rely on the methods that work best in practice to answer specific research questions, focusing most heavily on the practicalities of the chosen approach, not just paradigmatic alignment [ 58 ]. However, it is the view of some that pragmatism should be viewed as more of an approach, rather than a “true” paradigm. Consequently, the present work has not explored pragmatism in detail as it has other common paradigms [ 30 ].

Collaborate with or Consult Experienced Researchers Where Possible

While paradigms might seem complex and novel for many in the medical education community, they are a key facet of research, and certainly not new to other disciplines, such as sociology and general education [ 59 – 61 ]. Given this, collaboration can prove fruitful and may be the final key to success. When possible, collaborating with experienced researchers, particularly those who focus upon methodology, can be very beneficial. Experienced scholars can provide guidance regarding the philosophical questions associated with paradigms, while keeping in mind which methodology and methods may be best utilized by the research team. Where collaboration is not feasible, you may wish to contact a methodologist or experienced researcher to enquire as to whether they provide consultation services to review your research approach.

Although immensely helpful for those wishing to develop their research skills, collaboration with regard to paradigm choice can generate tension, especially if researchers disagree concerning which paradigm would be best suited for their research. We recommend that, prior to agreeing upon any collaborative projects, potential collaborators meet to develop a “shared agenda.” Shared agendas include a set of common objectives, a list of available resources, research questions of interest, and discussion as to each researcher’s personal paradigm. Compromise may be required on the behalf of one, or several, researchers, who may need to research within a paradigm unfamiliar to their personal stance, but best befitting the shared agenda of the collaborative team. For example, if you consider yourself to be a strict pragmatist, as introduced above, you might find extensive discussions about ontology and reality to be an unproductive use of research time. However, if working with a team of interpretivists, this may be viewed as a key part of their research efforts and study design. Through recognizing personal stances and being able to clearly express them in a dedicated reflexive space, collaboration may be eased, and even enhanced.

Lastly, when writing for publication, we recommend transparency as to each team member’s paradigmatic stance and inclusion of detail regarding how reflexivity was used to navigate any tensions. This monograph may be used as an example of collaborative writing. The authors approached this topic neutrally but have different personal paradigms. One author (MB) is a constructivist, and the other (AD) is a pragmatist. In the conception and construction of this work, the authors began with reflexive discussions on their paradigmatic assumptions, including personal views regarding the philosophy of science discussed in this paper. It was determined the shared agenda of this work was to remain as neutral as possible, while acknowledging potential assumptions each author holds. We hope this allows for a more transparent presentation of this monograph.

Conclusions

While initially complex, identification of a research paradigm is an essential aspect of any rigorous research project. Further, beyond individual projects, association of knowledge with specific paradigms may lead to a better overall understanding of research within medical education, furthering the advancement of the entire field.

Through this article, we have attempted to outline some initial tips for researchers looking to improve on projects via identification of a research paradigm. With consideration of these tips, and more open discussions within research teams, your research can take on new purpose and be understood with greater depth.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 Research Paradigms and Philosophical Assumptions

Research involves answering questions, and the approach utilised is based on paradigms, philosophical assumptions, and distinct methods or procedures. Researchers’ approaches are influenced by their worldviews which comprise their beliefs and philosophical assumptions about the nature of the world and how it can be understood. 9 These ways of thinking about the world are known as research paradigms, and they inform the design and conduct of research projects. 10,11 A paradigm constitutes a set of theories, assumptions, and ideas that contribute to one’s worldview and approach to engaging with other people or things. It is the lens through which a researcher views the world and examines the methodological components of their research to make a decision on the methods to use for data collection and analysis. 12 Research paradigms consist of four philosophical elements: axiology, ontology, epistemology, and methodology. 10 These four elements inform the design and conduct of research projects (Figure 1.1), and a researcher would have to consider the paradigms within which they would situate their work before designing the research.

Ontology is defined as how reality is viewed (nature of reality) – accurately captured as an entity or entities. It is the study of being and describes how the researcher perceives reality and the nature of human engagement in the world. 13,14 It is focused on the assumptions researchers make to accept something as true. These assumptions aid in orientating a researcher’s thinking about the research topic, its importance and the possible approach to answering the question. 12 It makes the researcher ask questions such as:

- What is real in the natural or social world?

- How do I know what I know?

- How do I understand or conceptualise things?

In healthcare, researchers’ ontological stance shapes their beliefs about the nature of health, illness, and healthcare practices. Here are a few examples of ontological stances that are commonly adopted by researchers in healthcare:

- Biomedical ontological stance: This ontological stance assumes that biological mechanisms can explain health and illness and that the body is a machine that can be studied and fixed when it malfunctions. 11 Researchers who take a biomedical ontological stance tend to focus on medical interventions such as drugs, surgeries, and medical devices.

- Social constructivist ontological stance: This ontological stance assumes that health and illness are social constructs that are shaped by cultural and social factors. 13 Researchers who take a social constructivist ontological stance tend to focus on understanding the social and cultural context of health and illness, including issues such as health disparities, patient-provider communication, and the role of social determinants of health.

- Critical realist ontological stance: This ontological stance assumes that there is a reality that exists independently of our perceptions but that our understanding of that reality is always partial and mediated by our social context. 11,14 Researchers who take a critical realist ontological stance tend to focus on understanding the complex interactions between social and biological factors in health and illness.

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with the study of knowledge and belief. It describes the ways knowledge about reality is acquired, understood, and utilised. 15 This paradigm highlights the relationship between the inquirer and the known –what is recognised as knowledge. Epistemology is important because it helps to increase the researcher’s level of confidence in their data. It influences how researchers approach identifying and finding answers while conducting research. 12 In considering the epistemology of research, the researcher may ask any of the following questions:

- What is Knowledge?

- How do we acquire knowledge and what are its limits?

- Is it trustworthy? Do we need to investigate it further?

- What is acceptable knowledge in our discipline?

The epistemological stance of healthcare researchers refers to their fundamental beliefs about knowledge and how it can be acquired. There are several epistemological stances that researchers may take, including positivism, interpretivism, critical theory, and pragmatism.

- Positivism: This epistemological stance is grounded in the idea that knowledge can be gained through objective observation and measurement. 11 Researchers who adopt a positivist stance aim to create objective, measurable, and replicable research that can be used to predict and control phenomena. For example, a researcher studying the effectiveness of a medication might conduct a randomized controlled trial to measure its impact on patient outcomes.