In History, The Past is the Present is the Future

If the past is so all terribly bad, then aren’t we lucky in the present?

If history is, as James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, says, “a nightmare from which I am trying to awake”, how and when do we wake up? What, in short, are we going to do about the crimes of the past, the slavery, genocide, ethnic cleansing, colonization? These crimes have contributed to making the world we live in. Attention paid to them is recognition that “what’s past is prologue,” and they have shaped our lives, traditions, institutions, and ideologies.

But what kind of attention? Lately, much has been made of historical injustices around the world. This is, scholar Berber Bevernage writes, “ one of the most remarkable phenomena in current international politics .” Across the globe, initiatives addressing “all kinds of historical evils” have occurred. These range from:

“Symbolic acts such as memorialization programs, truth commissions, and public apologies, to more practical political measures such as reparation payments and historical redress, to straightforward judicial prosecution through tribunals and (inter)national courts.”

Acknowledging that this trend has both its defenders as well as its detractors, Bevernage argues that there is a right way and a wrong way of going about it. “Retrospective politics,” as he calls this tendency, can have negative effects. He is most concerned about a sharp historical division between good and evil, what he calls “temporal Manichaeism.” This positions the past as a place of evil and suggests that evil existed only in the past, and that the present has progressed enough to be free of such horrors as, say, the twentieth century was replete with.

The tendency of an “Evil Past” threatens to “legitimize the present” as the best of all possible worlds. If the past is so all terribly bad, then aren’t we lucky in the present? Bevernage calls this kind of thinking anti-utopian, blighting present- and future-orientated politics. Too much satisfaction about how bad things were may “marginalize claims of victims of contemporary crimes and human rights violations” Bevernage, it should be noted, questions the progressivist views of history, which holds that things inevitably get better over time.

“Ethical Manichaeism and anti-utopianism are not inherent features of all retrospective politics but rather result from an underlying philosophy of history that treats the relation between past, present, and future in antinomic terms and prevents us from understanding ‘transtemporal’ injustices and responsibilities.”

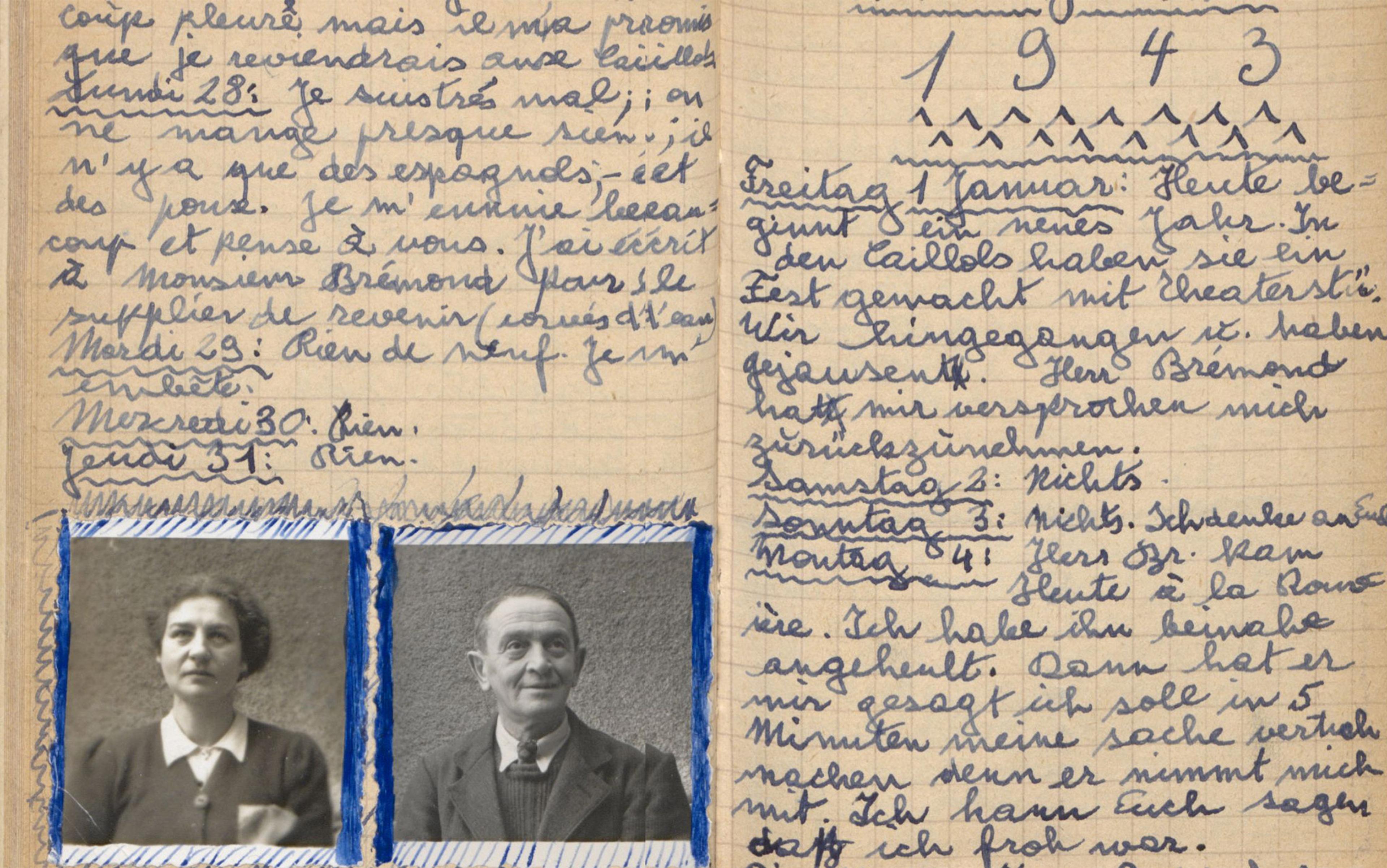

“Transtemporal” suggests the past, present, and future are not mutually exclusive. Bevernage gives the example of the Argentine Madres ( often actually grandmothers, because the mothers were murdered) who have claimed the state kidnapping of children during the Dirty War of the late 1970s does not belong in the past. After all, a six-year-old disappeared by the dictatorship in 1976—the children were given to regime supporters—would be 51 today. Another example is the Khulumni Support Group of South Africa, which advocates for the victims and survivors of apartheid, which was formally repealed in 1991: the group declares “the past to be in the present.” The past made the present and is inseparable from it.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

“We should look for types of retrospective politics that do not oppose but complement or reinforce the emancipatory and utopian elements in present- and future-directed politics—and the other way around: present- and future-oriented politics that do not forget about historical injustices.”

Bevernage’s theoretical discussion doesn’t address the forces opposed to historical redress. It isn’t, after all, just theorists of history who may question the historical moment. Those responsible for historical crimes typically reject accountability, for obvious reasons, and rally around Longfellow’s “Let the dead Past bury its dead.”

The trouble, of course, is that the bones keep turning up.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Islands in the Cash Stream

- Wooden Kings and Winds of Change in Tonga

- Women in the Vijayanagar Empire

The Psychological Problems of Modern Warfare

Recent posts.

- Performing as “Red Indians” in Ghana

- The Long Shadow of the Jolly Bachelors

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- AHR Interview

- History Unclassified

- Submission Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Join the AHR Community

- About The American Historical Review

- About the American Historical Association

- AHR Staff & Editors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Introduction: Histories of the Future and the Futures of History

David C. Engerman is Professor of History at Brandeis University, where he has taught since receiving his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1998. His first two books—most recently Know Your Enemy: The Rise and Fall of America's Soviet Experts (Oxford University Press, 2009)—examined Russia and the USSR in American intellectual and political life. His current project, tentatively titled “The Global Politics of the Modern: India and the Three Worlds of the Cold War,” studies superpower aid competition in postcolonial India. It has been supported by grants from the American Council of Learned Societies, the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, the Harry S. Truman Library Institute, and the American Institute of Indian Studies.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David C. Engerman, Introduction: Histories of the Future and the Futures of History, The American Historical Review , Volume 117, Issue 5, December 2012, Pages 1402–1410, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/117.5.1402

- Permissions Icon Permissions

As regards knowledge, the future … presents itself as an impenetrable medium, an unyielding wall. Karl Mannheim 1

I n spite of K arl M annheim's warning about the difficulties of reckoning with future events, a small but growing number of brave historians have been exploring the place of the future in twentieth-century history. Drawing especially on the vocabulary of the Begriffsgeschichte of Reinhart Koselleck, they have sought to analyze aspects of past “horizons of expectation” rather than limiting themselves to “spaces of experience.” Studies of experience seem more susceptible to historical analysis; they are, in Koselleck's apt phrase, “drenched with reality.” Yet this flood of “reality” is deceptive, he suggests. It is impossible to analyze experience without incorporating expectation; how historical subjects imagined their futures is crucial to understanding their pasts. 2 Thus the contributors to this AHR Forum seek to link experience and expectation, the past and the future, in order to illuminate key moments of possibility in the twentieth century and to offer insights into the methods of historical scholarship.

The three essays that follow all concern themselves with explication and analysis of horizons of expectation in the past: how did their historical subjects envision the future, and what do those visions reveal about their own time? The articles by Jenny Andersson and by Matthew Connelly and his nine co-authors (termed, for convenience, “Team Connelly”) focus upon the latter half of the twentieth century in the North Atlantic world, and especially upon state sponsorship of studies of the future. Not surprisingly given their chronological and geographic emphases, the Cold War plays a prominent, even dominant, role in these essays. The third article, by Manu Goswami, focuses on the earlier twentieth century, offering a subtle and penetrating analysis of the prolific Indian social scientist Benoy Kumar Sarkar. Goswami is concerned with horizons of expectation for a world order no longer defined around empires.

Individually and together, the forum articles draw our attention to the politics of the future—how visions of the future both reveal and shape the exercise of power. Each of the essays operates at two levels of political analysis: geopolitics, on the one hand, and state politics, on the other. First in prominence and scale is the focus on geopolitics. The articles document creative imaginings of new world orders, post-imperial in Goswami's case, post–Cold War in the cases of Andersson and (in a very different way) Team Connelly. The authors thus build on the insights of anthropologist Johannes Fabian, whose landmark critique of anthropological time contained the observation that “ geopolitics has its ideological foundations in chronopolitics .” Notions of time, Fabian continued, are not “natural resources” but “ideologically construed instruments of power.” 3 These instruments, in turn, underwrote the world order, whether imperial or Cold War. Thus at the geopolitical level, the essays focus on ways in which creative imaginings of the future offered sites of resistance to a dominant world order—as well as the boundaries of that resistance. These boundaries were guarded at the next level of political analysis: state politics. State power is the central category in Team Connelly's essay, and is present in Andersson's and Goswami's as well. Government officials underwrote studies of the future (for Team Connelly), shaped future studies (for Andersson), and presented a conceptual obstacle for anti-imperialism (for Goswami). The tensions between state politics and geopolitics appear in all three articles; interrogation of these tensions can generate substantial insights.

T he title of J enny A ndersson's essay , “The Great Future Debate and the Struggle for the World,” reflects the self-perceptions of its subjects, a disparate group of futurologists in the North Atlantic who considered studies of the future to be the central task of not just social scientists but societies. The futurologists ranged widely in terms of politics, geography, their relationships to state power, and their place in their respective nations' intellectual lives. Celebrated in a 1972 account by American Alvin Toffler, these students of the future prided themselves on not just predicting the future but also (in Toffler's breathless prose) outlining “the alternatives facing man as the human race collides with an onrushing future.” 4 The activities and the ideas of Andersson's subjects reveal a certain parallelism: just as they sought to identify trends that affected the whole world (crossing, in particular, the divide between the Cold War East and West), they frequently crossed borders themselves and self-consciously sought to establish a transnational discourse on the human future. 5

Andersson's subjects attempted to overcome the Cold War divide through at least two gambits, one transnational and one global. The transnational move of futurologists such as Bertrand de Jouvenel was to identify common ground between the industrial nations of the East and West. De Jouvenel was joined by many American and Western European scholars and commentators from the right and the left. His critique thus echoed Herbert Marcuse: both saw the emergence of massive bureaucratic states as impinging upon “the future of democratic institutions.” 6 The second, global, form of futurology among Andersson's subjects identified common trends that took place beyond the level of individual states. Foremost here were environmental issues, concerned with humankind's effects on the earth; the major issues were environmental degradation, on the one hand, and fear that the earth's human population would outstrip its resources, on the other. Both approaches constituted critiques of the Cold War global order.

Other challenges to Cold War geopolitics were even more explicit, and here Andersson's accounts of Eastern European futurologists are especially interesting. “Social forecasting” grew in the Soviet Union and across the Eastern Bloc in the 1950s and especially the 1960s. Just as “concrete social research” transformed studies of Soviet society from derivations of Marxist ideology into something resembling research into actual social conditions, prognostik used quantitative measures rather than ideological presuppositions at its core. The notion that the Communist future would be discerned through quantitative metrics rather than Marxist eschatology was itself a challenge to party power. Andersson shows how Eastern European futurologists, particularly those in Poland and Czechoslovakia, used future studies for “critique and dissent.” 7 These studies, in turn, quickly found enthusiasts among Western Europeans engaged in critique of their own societies—most notably Ossip Flechtheim, who had coined the term “futurology” during World War II. By the 1970s, futurologists East and West hoped that their field could serve what Flecht-heim called a “critical emancipatory function.” They created numerous institutes and working groups, including the World Futures Studies Federation, and developed a circuit of international conferences with portentous titles like “Mankind 2000.” 8

Yet hopes for global emancipation were no match for Cold War state power, as was amply illustrated at the 1972 conference “The Common Future of Man” in Bucharest. Japanese government officials ensured that their nation's delegates adhered to the country's pro-growth policies; they were not critics but closer to bureaucrats. The Romanian hosts maintained close surveillance on participants and intervened directly to challenge the notion of plural futures; there could be only one, state-sanctioned, future. Anti-establishment futurology could go only so far. Powerfully imagined futures could not surmount actually existing state power. Just as states sought to control the narratives of their past (a familiar topic for historians), they also sought to restrict studies of their future. 9

S tate power is unambiguously at the core of Team Connelly's article, which analyzes official American views of the Soviet threat. In cataloguing the series of unfortunate predictions about Soviet nuclear capabilities and intentions, this essay offers a spirited critique of the so-called “Soviet estimate,” as well as of historians who ignore past futures. Unlike Andersson's subjects, who included critics of the status quo, Team Connelly's key subjects are comfortably ensconced in the state apparatus. Hence one key element of the article is the bureaucratic politics of the future—as suggested by the wonderful title quote from Alain Enthoven, an economist who rejected the claims of uniformed officers that they had any unique insight into fighting a nuclear war. While well-attuned to the internal disputes over the Soviet estimate—competing visions of the USSR's ability and desire to engage in nuclear conflict—Team Connelly also seeks to identify the contributions of histories of prediction to broader histories of state power. The essay contains, at the start and again at the end, highly suggestive references to the ways in which state power constituted itself “in the mystique of clairvoyance.” The state's efforts to reinforce political authority and control its subjects are visible, Team Connelly suggests, in endeavors such as the civil defense programs of the 1950s. Evident in easily satirized cartoons like “Duck and Cover” as well as the official and unofficial promotion of home fallout shelters, talk of civil defense was ubiquitous in the 1950s and remained a presence throughout the Cold War. Yet civil defense was not just a strategy for legitimation or mobilization. As American nuclear strategy shifted from “Massive Retaliation” to “Counterforce/No Cities” and beyond, the question of how many civilians could survive a nuclear exchange was of pressing (if morbid) concern. And its results were complex and at times counterintuitive; historian Dee Garrison suggests that reactions against civil defense drills helped broaden the peace movement in the late 1950s. 10 But for nuclear strategists, estimates of Soviet civil defense programs provided clues about Soviet strategy—at the same time that they shaped American efforts.

The lack of reliable information about Soviet nuclear plans, furthermore, created a divisive bureaucratic politics of the future within the dubiously named “intelligence community”—which was actually a fractious group of analysts from a dozen or so agencies. (The divisions in this group are perhaps best summed up in a joke about the Soviet estimate: as one wag had it, the State Department believed that the Russians were not coming; the CIA insisted that the Russians were coming but would not be able to get to Washington; the Defense Intelligence Agency countered that the Russians could get to Washington and indeed were almost there; and the Air Force believed that the Russians were already in Washington—where they were hard at work in the State Department.) 11 The gaps in reliable intelligence meant that estimates of Soviet strength and strategies were rooted in assumptions of varying degrees of plausibility. Such predictions—“previsions,” in the language of the article—were all the more uncertain because they were so hard to falsify. No one could disprove a prevision in its own time, and Team Connelly notes that there was little effort on the part of the Soviet experts to review the often dismal record of past predictions. Given such interpretive freedom—or, better put, unaccountability—it is hardly a surprise that predictions were based in large part on presuppositions; previsions of the future depended less on past patterns and more on present priorities. Even concrete estimates, like Soviet nuclear capabilities, prompted significant disagreement among American analysts.

Over the course of the Cold War, estimates of Soviet intentions were less and less present in the major intelligence estimates: the first National Intelligence Estimate of the series was “Soviet Intentions and Capabilities” (1950), but later reports in the 1950s were limited to “Soviet Capabilities and Probable Programs”; by the 1960s, these estimates focused almost exclusively on “Soviet Capabilities for Strategic Attack.” One of the rare public controversies over the Soviet estimate—the creation of a “Team B” of outside experts to challenge CIA analysts in 1974—revolved around the estimates' typical emphasis on capabilities as opposed to intentions. Originally framed as a technical exercise to recalibrate official estimates of the Soviet threat, the core issue soon became, as one CIA official put it, “conflicting interpretations of the Soviet stance in the world today”—that is, around divergent a priori assumptions about Soviet intentions. Team B participants, most publicly the Harvard historian Richard Pipes, declared total victory over CIA analysts. In a 1986 article, Pipes claimed that after Team B “badly mauled” the CIA's in-house team, the National Intelligence Estimates took a “more somber” view of Soviet intentions. 12

Connelly et al. offer a different example of how horizons of expectation could alter spaces of experience. Briefly describing the career of Andrew Marshall, an economist who worked for the semi-official RAND Corporation before becoming the Pentagon's director of net assessment, they show how Marshall sought to understand Soviet defense policymaking in order to “game that system.” 13 Predictions about the future could be a weapon in the Cold War, not just in bureaucratic battles.

Team Connelly's attention to the ways in which the Cold War was fought through visions of the future is itself a significant insight. There are, however, more important, if at times less tangible, ways that the Cold War was as much about the future as the present. The Soviet Union and the United States battled on an ideological plane, offering contradictory visions of the future. Thus the Cold War was a battle as much over future time as over present-day space. Nikita Khrushchev's infamous boast “We will bury you” revealed his absolute certainty about the ultimate (i.e., future) superiority of Communism; it was not a threat of imminent attack. 14 By the same token, American liberalism insisted that the brightest future was possible only through free markets and democratic systems. 15 The future was not just a weapon in the Cold War, as Team Connelly's article amply demonstrates, but indeed one battleground of that conflict.

M anu G oswami's article offers a different sort of consideration of the tensions between geopolitics and state power, and focuses on the realm of the production of knowledge in the social sciences broadly defined. In “Imaginary Futures and Colonial Internationalisms,” Goswami reports on the battle between colonizer and colonized by explicating some of the texts of the prolific Indian social scientist Benoy Kumar Sarkar. She documents Sarkar's creative imaginings of a post-imperial future that looked beyond autonomous nation-states. Devoting himself to crossing national boundaries and bridging cultural traditions—he spent most of the decade after 1915 away from India—Sarkar insisted that cultural and intellectual interchange, not celebrations of age-old autonomous national traditions, was the best course to a post-imperial future. Through his own interactions with American and European intellectuals, he incorporated the North Atlantic “revolt against formalism” into his own ideas—emphasizing pluralism over monism, social selves over fully bounded individuals, cosmopolitanism over patriotism, and contingency over certainty. Just as Sarkar's ideas were shaped in conversation with some of the most important European and American intellectuals of his day, so too did he insist that nations “are moulded through constant interactions and intercourses of life and thought.” 16

Sarkar's vision stood in contrast to that of anticolonial nationalists who used the rhetoric of Woodrow Wilson to insist upon national self-determination. Independence, Sarkar insisted, could not be achieved without the participation of others: “The political emancipation of India will be achieved,” he wrote in 1922, “not so much in the Indus Valley or on the Deccan Plateau as in the Chinese plains, the Russian steppes or the Mississippi Valley.” While he presciently identified the Cold War powers that would loom so large in postcolonial India, he notably excluded Britain (or perhaps, in his syntax, the Salisbury Plain). Indeed, his intellectual and political attachments seem to have ranged across the United States and much of Europe to the exclusion of Britain. Soviet Russia, which was not on Sarkar's itinerary, was one important reference point for not just political but also cultural revolution. He also looked to Italy and Germany—in spite of their rising fascism—for inspiration in creating an independent and yet interconnected India. 17 Others from Europe's Asian colonies sought different interlocutors. Indian National Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru, for instance, joined with other anticolonial agitators in organizations such as the League against Imperialism; originally a nonpartisan left-wing organization based in Brussels, by the late 1920s the League was under the control of card-carrying Communists. 18 The intense and extreme politics of interwar continental Europe, then, cast a long shadow on the struggle for independent India—but did so by looking toward post-imperial futures beyond the nation-state.

Sarkar frequently critiqued the nation-state—the second level of political analysis—along the lines of his geopolitical vision. He called for a “futuristic reconstruction of the problem of external sovereignty,” a reconstruction that would reimagine the state without rigid and absolute external boundaries, and without presumed homogeneity within those boundaries. Sarkar's cosmopolitanism here drew not only on his geopolitics, but also on his immersion in the modernist artistic and literary currents of early-twentieth-century Europe and the United States. This is an important observation, as Goswami illustrates how Sarkar's geopolitics were closely connected to his aesthetic positions. Here, of course, he found good company during his decade-long peregrinations. New York City alone was awash in writers and artists questioning the relationship between nations and cultures, and between politics and aesthetics. 19 Goswami frequently notes how Sarkar and his interlocutors “anticipated” or “prefigured” later academic critiques. Sarkar's criticism of “orientalisme” in Western scholarship, for instance, clearly has more in common with Edward Said's famous critique than just the name. Similarly, his interrogations of Western intellectual traditions clearly resonate with the critiques of Dipesh Chakrabarty and others. Postcolonialism, in other words, did not need to wait for the demise of the colonies. By drawing historians' attention to the more fluid visions of post-imperial futures, Goswami breaks the necessary link between anticolonialism and nationalism. This link is, as she points out, not just an artifact of imperial histories, but an essential exercise for the nations that ultimately emerged from the wreckage of European empires. 20

I f S arkar anticipated some key intellectual moves of the late twentieth century, what can we historians anticipate for studies of past futures? Taken together, the three essays in this forum offer powerful analyses of the politics of the future. The articles of Andersson, Goswami, and Team Connelly hardly exhaust the possibilities of incorporating the future into studies of the past. For the future is a subject not just for political analysis, but for economic and cultural analysis as well. Take, for instance, the example of economic forecasting, a key enterprise of twentieth-century economics and political economy. Economists' increasing use of mathematical tools and quantitative measures in the first half of the twentieth century facilitated efforts to anticipate the direction of these measures. Thus the era saw the rise of economic forecasts, as business leaders sought to predict the future for their own gain. 21 Even the politics of the future, as Andersson discusses, could entail economic forecasts. A debate about the earth's carrying capacity and the threat of “overpopulation” in the 1970s ultimately took the form of a wager between a biologist and an economist over the future direction of commodity prices. 22

Economists' visions of the future were hardly limited to prediction; theories and practices of national economic planning were also ubiquitous in the twentieth century. Wars occasioned the expanding reach of the state in national economic life. And between the world wars, Soviet economic organization prompted extensive debates about the costs and benefits of central planning. These debates took place among economists as well as ideologues waving the flags of Soviet Communism, Nazism, imperialism, and anticolonial nationalism. Even the United States, with its strong laissez-faire traditions, instituted extensive wage, price, and production controls during World War II. The newly independent nations of the so-called Third World took up the cause of planning in the 1950s, to such an extent that one American economist noted in 1967 that planning “has become so popular and has been applied so widely” that it could “refer to almost any kind of economic analysis or policy thinking in almost any country in the world.” 23 This statement, though, was more about the past than the future; central planning would be on the defensive around the world by the 1970s.

While economists spent much of the twentieth century trying to bring the future within cognitive if not literal control, artists and writers took almost the opposite tack. Utopian (and occasionally dystopian) visions of the future abounded in the 1920s: in the cultural and social experimentation of post-Revolutionary (and pre-Stalinist) Soviet Russia, in fascist Italy, and around the world—not least at World's Fairs providing concrete visions of the future. Futurist movements have been the subject of extended aesthetic and literary analysis, which would facilitate their consideration by historians of the future. 24

Forecasting the study of the future beyond political and economic histories would be a difficult task indeed. On the basis of this forum, though, it seems safe to say that even without central planning, the histories of the future will multiply, expanding our knowledge of past hopes and dreams.

1 Karl Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge , trans. Louis Wirth and Edward Shils (1935; repr., London, 1991), 234.

2 Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time , trans. Keith Tribe (Cambridge, Mass., 1985), esp. 270–275.

3 Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (1983; repr., New York, 2002), 144.

4 Alvin Toffler, The Futurists (New York, 1973), 3.

5 This species-wide vision suggests a continuation of the trends in mid-century American social science; see David A. Hollinger, “How Wide the Circle of the ‘We’? American Intellectuals and the Problems of the Ethnos since World War II,” American Historical Review 98, no. 2 (April 1993): 317–337.

6 For citations on varieties of convergence theories after World War II, see David C. Engerman, “To Moscow and Back: American Social Scientists and the Concept of Convergence,” in Nelson Lichtenstein, ed., American Capitalism: Social Thought and Political Economy in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia, 2006), 47–68.

7 On the rise of Soviet “concrete social research,” see Ilya Zemtsov, IKSI: Ocherk istorii razvitiia sovetskoi sotsiologii (Jerusalem, 1976).

8 Mario Kessler, “Zur Futurologie von Ossip K. Flechtheim,” in Bernd Greiner, Tim B. Müller, and Claudia Weber, eds., Macht und Geist im Kalten Krieg (Hamburg, 2011), 239–257. For other futurological organizations, see Kaya Tolon, “Futures Studies: A New Social Science Rooted in Cold War Strategic Thinking,” in Mark Solovey and Hamilton Cravens, eds., Cold War Social Science: Knowledge Production, Liberal Democracy, and Human Nature (New York, 2012), 45–62.

9 On historians and nationalism, see David A. Hollinger, “The Historian's Use of the United States, and Vice Versa,” in Thomas Bender, ed., Rethinking American History in a Global Age (Berkeley, Calif., 2002), 381–395; and Prasenjit Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China (Chicago, 1995).

10 Lawrence Freedman, The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy (New York, 1981), 132–137; Laura McEnaney, Civil Defense Begins at Home: Militarization Meets Everyday Life in the Fifties (Princeton, N.J., 2000); Dee Garrison, “‘Our Skirts Gave Them Courage’: The Civil Defense Protest Movement in New York City, 1955–1961,” in Joanne Meyerowitz, ed., Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945–1960 (Philadelphia, 1994), 201–226.

11 Ann Hessing Cahn, Killing Detente: The Right Attacks the CIA (University Park, Pa., 1998), 89–90.

12 Raymond L. Garthoff, “Estimating Soviet Military Intentions and Capabilities,” in Gerald K. Haines and Robert E. Leggett, eds., Watching the Bear: Essays on CIA's Analysis of the Soviet Union (Washington, D.C., 2003), 135–186; Howard Stoertz, Jr., to Robert W. Galvin, December 23, 1975, Anne Cahn Collection, National Security Archive, Washington, D.C.; Cahn, Killing Detente , chaps. 7–9; John Prados, The Soviet Estimate: U.S. Intelligence Analysis and Russian Military Strength (New York, 1982), 248–257; Richard Pipes, “Team B: The Reality behind the Myth,” Commentary 82, no. 4 (October 1986): 25–40, here 32–34.

13 This gambit is not mentioned in two antithetical evaluations of Marshall's work: Ken Silverstein, Private Warriors (New York, 2000), 9–21; and George E. Pickett, James G. Roche, and Barry D. Watts, “Net Assessment: A Historical Review,” in Andrew W. Marshall, J. J. Martin, and Henry S. Rowen, eds., On Not Confusing Ourselves: Essays on National Security Strategy in Honor of Albert and Roberta Wohlstetter (Boulder, Colo., 1991), 158–185.

14 William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York, 2003), 427–433.

15 Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (Cambridge, 2005), chaps. 1–3.

16 Morton White, Social Thought in America: The Revolt against Formalism (New York, 1949). On European-American connections, see especially James T. Kloppenberg, Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870–1920 (Oxford, 1986). Benoy Kumar Sarkar, The Science of History and the Hope of Mankind (London, 1912), 66–67.

17 Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford, 2007); Benoy Kumar Sarkar, The Futurism of Young Asia, and Other Essays on the Relations between the East and the West (Berlin, 1922), 306–307. Kris Krishnan Manjapra, “Mirrored Worlds: Cosmopolitan Encounter between Indian Anti-Colonial Intellectuals and German Radicals, 1905–1939” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2009), chap. 7; Mario Prayer, “Creative India and the World: Bengali Internationalism and Italy in the Interwar Period,” in Sugata Bose and Kris Manjapra, eds., Cosmopolitan Thought Zones: South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas (New York, 2010), 236–259, esp. 236–242.

18 Michele L. Louro, “At Home in the World: Jawaharlal Nehru and Global Anti-Imperialism” (Ph.D. diss., Temple University, 2011).

19 Benoy Kumar Sarkar, The Politics of Boundaries and Tendencies in International Relations (Calcutta, 1926), ix. In addition to Goswami's citations, see Ann Douglas, Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s (New York, 1995); George Hutchinson, The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (Cambridge, Mass., 1995); and for an “Arab-American Renaissance” akin to the Harlem Renaissance, Nicoletta Karam, “Kahlil Gibran's ‘Pen Bond’: Modernism and the Manhattan Renaissance of Arab-American Literature” (Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University, 2005).

20 Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, N.J., 2000); Vinay Lal, The History of History: Politics and Scholarship in Modern India (New Delhi, 2003), chap. 2.

21 On the American case, see Walter A. Friedman, “The Rise of Business Forecasting Agencies in the United States” (Harvard Business School Working Paper 07-045, 2007); Eli Cook, “The Pricing of Progress: Economic Indicators and the Capitalization of America” (Ph.D. dissertation-in-progress, Harvard University). Both works are cited with permission.

22 Paul Sabin, The Bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon, and the Gamble over the Earth's Future (New Haven, Conn., forthcoming 2013).

23 Max F. Millikan, “Introduction,” in Millikan, ed., National Economic Planning: A Conference of the Universities–National Bureau Committee for Economic Research (New York, 1967), 3–11, here 3. The historical literature on planning tends to focus on individual national cases too numerous to cite here. For a helpful overview, see Dirk van Laak, “Planung: Geschichte und Gegenwart des Vorgriffs auf die Zukunft,” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 34, no. 3 (July 2008): 305–326.

24 Richard Stites, Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution (Oxford, 1989); Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West (Cambridge, Mass., 2000); Christine Poggi, Inventing Futurism: The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism (Princeton, N.J., 2009); Marjorie Perloff, The Futurist Moment: Avante-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture (Chicago, 2003). On New York's World's Fairs, see David Gelernter, 1939: The Lost World of the Fair (New York, 1995); Lawrence R. Samuel, The End of the Innocence: The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair (Syracuse, N.Y., 2007).

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 2 |

| January 2017 | 10 |

| February 2017 | 26 |

| March 2017 | 48 |

| April 2017 | 12 |

| May 2017 | 21 |

| June 2017 | 11 |

| July 2017 | 22 |

| August 2017 | 39 |

| September 2017 | 30 |

| October 2017 | 17 |

| November 2017 | 47 |

| December 2017 | 46 |

| January 2018 | 67 |

| February 2018 | 50 |

| March 2018 | 14 |

| April 2018 | 31 |

| May 2018 | 10 |

| June 2018 | 28 |

| July 2018 | 9 |

| August 2018 | 10 |

| September 2018 | 32 |

| October 2018 | 27 |

| November 2018 | 18 |

| December 2018 | 15 |

| January 2019 | 12 |

| February 2019 | 13 |

| March 2019 | 36 |

| April 2019 | 27 |

| May 2019 | 32 |

| June 2019 | 28 |

| July 2019 | 7 |

| August 2019 | 58 |

| September 2019 | 17 |

| October 2019 | 27 |

| November 2019 | 44 |

| December 2019 | 4 |

| January 2020 | 10 |

| February 2020 | 11 |

| March 2020 | 7 |

| April 2020 | 7 |

| May 2020 | 8 |

| June 2020 | 6 |

| July 2020 | 12 |

| August 2020 | 37 |

| September 2020 | 18 |

| October 2020 | 45 |

| November 2020 | 30 |

| December 2020 | 32 |

| January 2021 | 30 |

| February 2021 | 51 |

| March 2021 | 30 |

| April 2021 | 12 |

| May 2021 | 42 |

| June 2021 | 28 |

| July 2021 | 17 |

| August 2021 | 10 |

| September 2021 | 26 |

| October 2021 | 21 |

| November 2021 | 19 |

| December 2021 | 24 |

| January 2022 | 13 |

| February 2022 | 9 |

| March 2022 | 23 |

| April 2022 | 31 |

| May 2022 | 26 |

| June 2022 | 33 |

| July 2022 | 24 |

| August 2022 | 31 |

| September 2022 | 30 |

| October 2022 | 24 |

| November 2022 | 54 |

| December 2022 | 15 |

| January 2023 | 22 |

| February 2023 | 13 |

| March 2023 | 21 |

| April 2023 | 15 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 21 |

| September 2023 | 11 |

| October 2023 | 6 |

| November 2023 | 17 |

| December 2023 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 12 |

| February 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| April 2024 | 23 |

| May 2024 | 10 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Editorial Board

- Author Guidelines

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1937-5239

- Print ISSN 0002-8762

- Copyright © 2024 The American Historical Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Why History Matters: Understanding Our Past to Shape Our Future

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on April 6, 2024

Categories Culture , History , Society

History isn’t just a dusty collection of names and dates from the past. It’s a mirror reflecting our societal evolution, a guidebook to our present, and a compass pointing to our future. Let’s explore why history holds the key to understanding ourselves and the world we inhabit.

Key Takeaways

- Historical study fosters an understanding of societal trends and human nature.

- A sense of identity and a shared narrative are cultivated through history.

- History is crucial for developing analytical and critical thinking skills.

Understanding the Value of History

The value of history lies in its power to elucidate the past events, inform the present conditions, and guide future decisions. Through a structured analysis and application of historical context, one appreciates its role as an essential discipline.

Analyzing Past, Present, and Future

History provides a detailed record of past events which significantly influence present societal structures and future trajectories. Historical research identifies patterns that have shaped societies, cultures, and traditions. This analysis allows individuals to learn from past decisions and understand the possible implications for future outcomes.

The Importance of Historical Context

Understanding historical context is crucial for interpreting events accurately. It ensures a nuanced view of past actions and decisions within the context of their time. Recognizing the value of historical context prevents the misrepresentation of events and promotes a deeper appreciation for the complexities of past societies and their decisions.

History as a Discipline

Studying history as a discipline involves meticulous research and fact-checking . It equips historians with frameworks and techniques to construct accurate accounts of the past. This discipline underscores the credibility of historical narratives and validates their relevance to current understandings. It fosters an awareness that present conditions result from human choices that can be influenced by further action.

The Role of History in Society

History serves a critical role in society by fostering informed citizens, preserving the collective memory, and enhancing an understanding of cultural and religious diversity. Each of these aspects contributes to a society that values its past while shaping its future.

Developing Informed Citizens

Informed citizens are the bedrock of a healthy democracy. Historical knowledge equips them with the context necessary to understand current policies and their impact on rights and responsibilities. They learn not only about historical events but also how to engage critically with sources and discern patterns that influence modern governance. Recognizing the evolution of societal norms and laws from historical precedents contributes to a more engaged and analytical electorate.

- Key Point : History teaches critical thinking skills.

- Impact : Engaged citizens contribute to a more robust democracy.

Preserving Collective Memory

Societies with a strong sense of their history possess a collective memory that safeguards against cultural and memory loss. The preservation of this memory through documentation, oral traditions, and historical landmarks helps communities maintain a sense of identity and continuity. Without this, societies risk becoming rootless, lacking the connection to shared experiences that guide collective values and traditions.

Examples of Collective Memory Preservation :

- Historical literature

Understanding Cultural and Religious Diversity

History illuminates the traditions and beliefs of different cultures and religions, revealing the rich tapestry of human experience. By studying the historical contexts of societies, it becomes possible to appreciate the diversity of perspectives and practices that exist. This understanding fosters tolerance and can help mitigate conflicts arising from cultural or religious misunderstandings.

Benefits of Historical Understanding :

- Enhances social cohesion.

- Promotes mutual respect.

Collectively, the role of history in society is multifaceted, playing a pivotal part in shaping the narratives that societies live by, guiding principles of democracy, and contributing to the rich mosaic of human cultures and religions.

Learning from Historical Events

Historical events offer invaluable insights into the complexities of human experience, from the sobering repercussions of wars and conflicts to the transformative power of significant milestones.

Lessons from Wars and Conflicts

Wars and conflicts stand as stark reminders of both human frailty and resilience. For instance:

- The Holocaust encapsulates the extremity of human cruelty and the importance of empathy and courage. Remembering the Holocaust is essential for understanding the impact of prejudice and the necessity of standing up against it.

- Courage is highlighted by stories of resistance and survival, which provide a deeper understanding of the Jewish experience and the capacity for individuals to enact change amidst adversity.

The Impact of Significant Historical Milestones

Significant historical milestones shape the course of world history and inform current societal norms. They are moments that echo through time, prompting reflection and adaptation.

- The end of slavery in the United States marked a drastic turn in human rights and freedoms, encouraging a global reassessment of racial equality.

- Signified the end of the Cold War and the start of a new era in international relations, and it serves as a potent symbol of liberation and the desire for unity.

Connecting Personal and Collective Histories

Connecting personal and collective histories enhances understanding of societies by intertwining individual experiences with broader historical narratives. This synthesis fosters empathy and helps individuals appreciate the depth of the human experience.

Embracing a Broader Human Experience

Individuals often perceive history through the lens of their personal stories, which are fundamentally tied to the larger tapestry of society’s past. For instance, the Holocaust is not merely a chapter in a history book, but a profound part of many personal histories that still resonate today. Examining both personal memories and collective histories allows people to engage more deeply with being human. Such engagement provides grounding, as histories give context to present circumstances, ensuring that individuals are not rootless but connected to a continuum that defines cultures and communities.

The Dangers of Historical Amnesia

Forgetting or ignoring the past, a condition akin to societal memory loss, poses a significant risk to societies. It is crucial to remember the trials and lessons of history, such as the horrors of the Holocaust, to build resilience against repeating past atrocities. Neglecting to connect personal experiences with the collective memory of societies can lead to a lack of empathy and understanding. This disconnect also stymies learning and growth, as historical amnesia prevents societies from effectively rooting themselves in history, which can guide better decision-making and foster a more inclusive understanding of the human experience.

Educational Perspectives on History

The study of history occupies a crucial role in academic curriculums, offering methodologies that cross into various disciplines and fostering a wide range of competencies critical to intellectual development.

History’s Place in Academic Curriculums

History, as an academic discipline, grounds students in the temporal dimensions of human experience. Educational systems globally include history to various extents, recognizing its role in cultivating critical thinking and an understanding of how societies have evolved. The reasons to include history in curriculums hinge on its ability to provide context for current events and to enhance civic literacy .

Methodologies and Approaches in Historical Studies

Historical research harnesses diverse methodologies ranging from diachronic analysis , which tracks changes and continuities over time, to comparative historical study , which juxtaposes past and present to foster deeper understanding. The approach to studying history typically emphasizes the diachro-mesh of events, ideas, and figures, offering students a toolkit for discerning and interpreting complex narratives.

The Interplay between History and Other Academic Disciplines

History does not exist in isolation. It actively engages with and enriches other fields, like economics, literature, and political science. This interplay underscores the multidisciplinary essence of historical education, thereby illuminating the interconnectedness of knowledge and the multiplicity of perspectives. By situating historical events within broader intellectual landscapes , students learn to appreciate the nuanced interdependencies that have shaped human societies.

Essays About History: Top 5 Examples and 7 Prompts

History is the study of past events and is essential to an understanding of life and the future; discover essays about history in our guide.

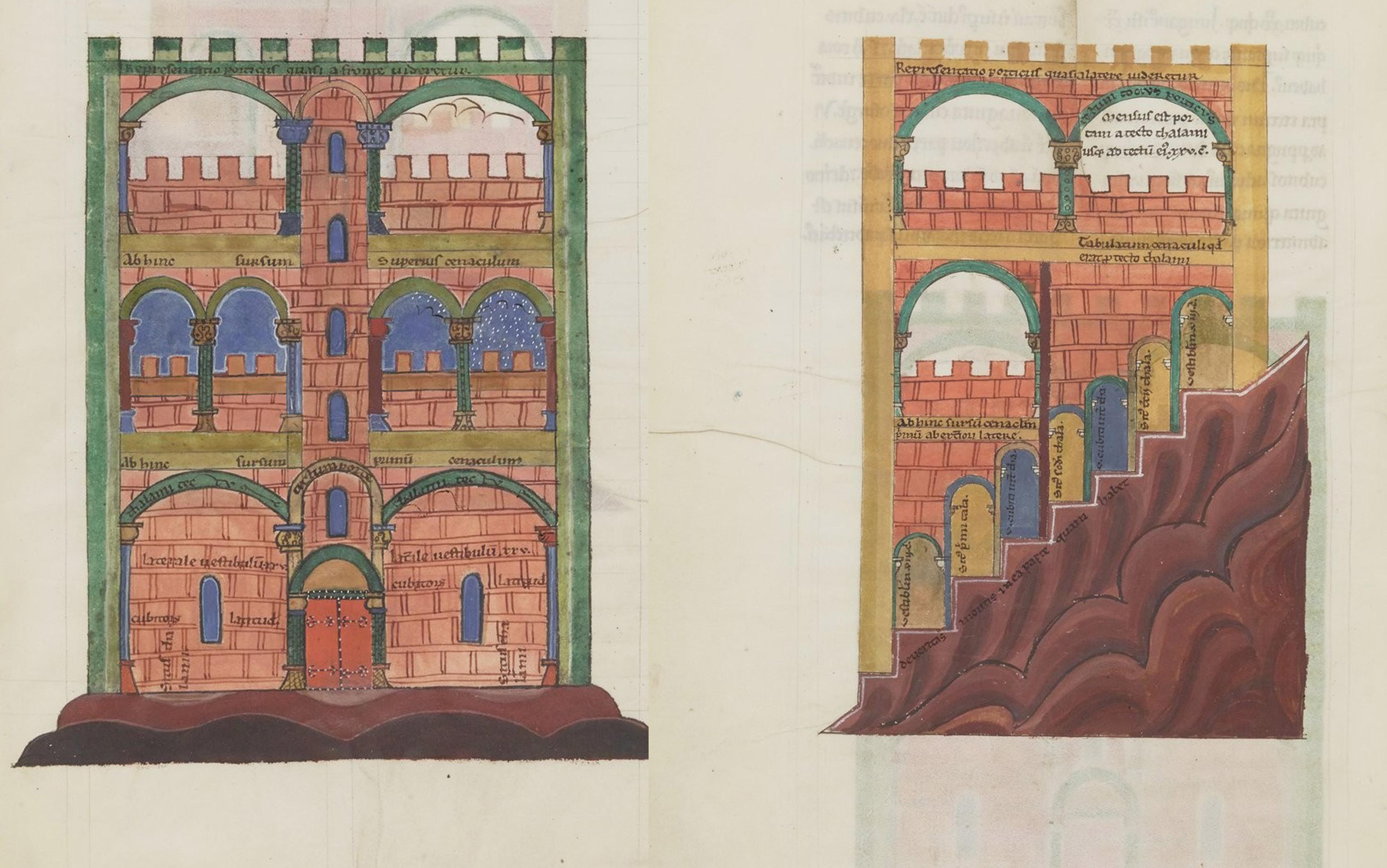

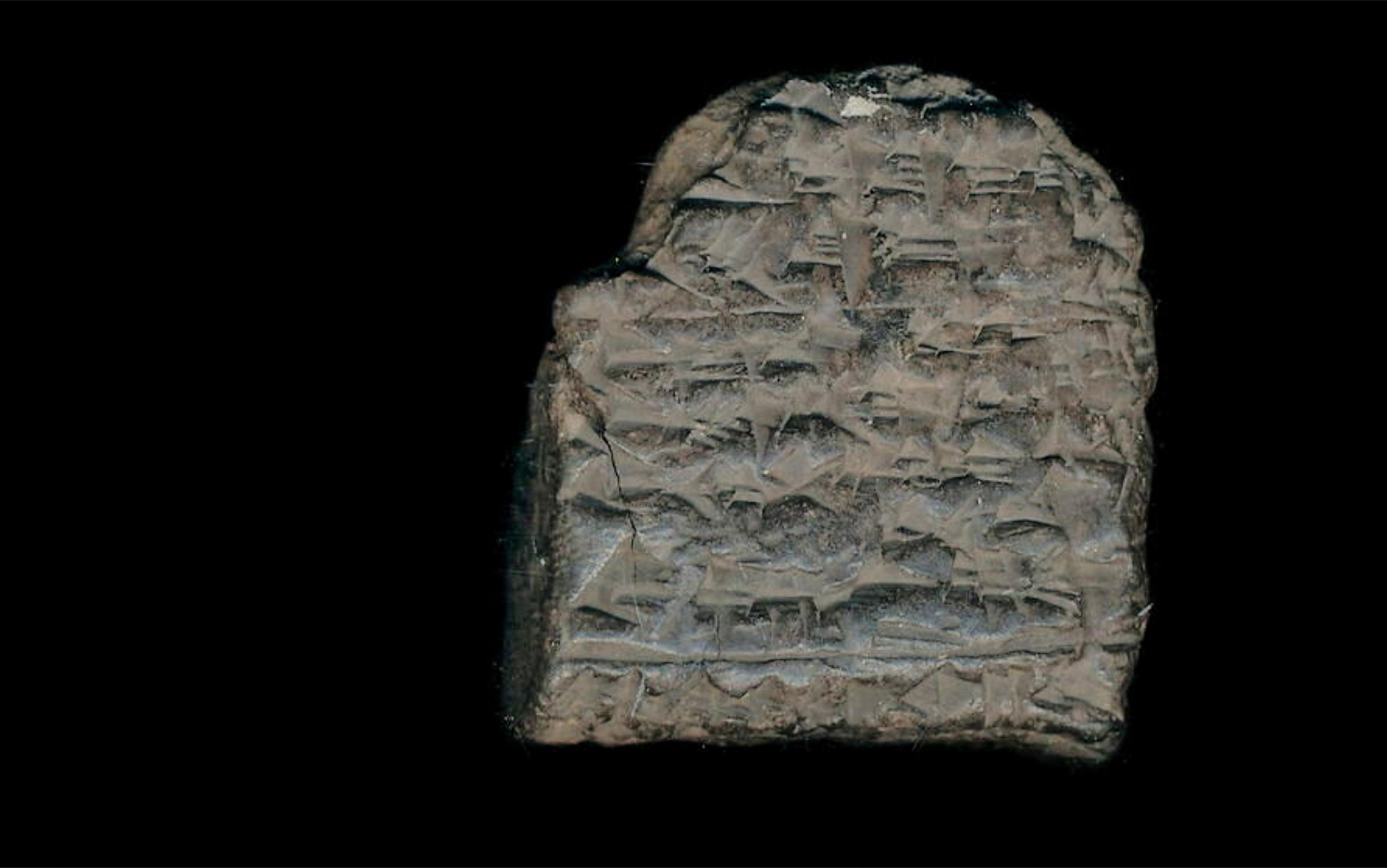

In the thousands of years, humans have been on earth, our ancestors have left different marks on the world, reminders of the times they lived in. Curiosity is in our nature, and we study our history on this planet by analyzing these marks, whether they be ancient artifacts, documents , or grand monuments.

History is essential because it tells us about our past. It helps us to understand how we evolved on this planet and, perhaps, how we may develop in the future. It also reminds us of our ancestors’ mistakes so that we do not repeat them. It is an undisputed fact that history is essential to human society, particularly in the world we live in today.

If you are writing essays about history , start by reading the examples below.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

5 Examples On Essays About History

1. history of malta by suzanne pittman, 2. why study history by jeff west, 3. history a reflection of the past, and a teacher for the future by shahara mcgee, 4. the most successful crusade by michael stein, 5. god, plagues and pestilence – what history can teach us about living through a pandemic by robyn j. whitaker, writing prompts for essays about history, 1. what we can learn from history, 2. analyzing a historical source, 3. reflection on a historical event, 4. your country’s history, 5. your family history, 6. the impact of war on participating nations, 7. the history of your chosen topic.

“The famous biblical figure St. Paul came to Malta due to his ship getting wrecked and he first set foot on Malta at the beautiful location of what it know called St. Paul’s bay. St Paul spread Christianity throughout Malta which at the time has a mostly pagan population and the vast majority of Malta inhabitants have remained Christian since the days that St Paul walked the streets of Malta.”

Short but informative, Pittman’s essay briefly discusses key events in the history of Malta, including its founding, the spread of Christianity, and the Arab invasion of the country. She also references the Knights of Malta and their impact on the country.

“Every person across the face of this Earth has been molded into what they are today by the past. Have you ever wondered sometime about why humanity is the way it is, or why society works the way it does? In order to find the answer, you must follow back the footprints to pinpoint the history of the society as a whole.”

West’s essay explains history’s importance and why it should be studied. Everything is how it is because of past events, and we can better understand our reality with context from the past. We can also learn more about ourselves and what the future may hold for us. West makes essential points about the importance of history and gives important insight into its relevance.

“While those stories are important, it is vital and a personal moral imperative, to share the breadth and depth of Black History, showing what it is and means to the world. It’s not just about honoring those few known for the 28 days of February. It’s about everyday seizing the opportunities before us to use the vastness of history to inspire, educate and develop our youth into the positive and impactful leaders we want for the future.”

In her essay , McGee explains the importance of history, mainly black history, to the past and the future. She writes about how being connected to your culture, history, and society can give you a sense of purpose. In addition, she reflects on the role black history had in her development as a person; she was able to learn more about black history than just Martin Luther King Jr. She was able to understand and be proud of her heritage, and she wishes to use history to inspire people for the future.

“Shortly afterwards, Egyptians and Khwarazmians defeated an alliance of Crusaders-States and Syrians near Gaza. After Gaza, the Crusaders States were finished as a political force, although some cities along the coast hung on for more than forty years. The Egyptian Ayyubids occupied Jerusalem itself in 1247. The city now was not much more than a heap of ruins, becoming an unimportant backwater for a long time.”

Stein describes the Sixth Crusade, during which Emperor Frederick II could resolve the conflict through diplomacy, even gaining Christian control of Jerusalem by negotiating with the Sultan. He describes important figures, including the Popes of the time and Frederick himself, and the events leading up to and after the Crusade. Most importantly, his essay explains why this event is noteworthy: it was largely peaceful compared to the other Crusades and most conflicts of the time.

“Jillings describes the arrest of a Scottish preacher in 1603 for refusing to comply with the government’s health measures because he thought they were of no use as it was all up to God. The preacher was imprisoned because he was viewed as dangerous: his individual freedoms and beliefs were deemed less important than the safety of the community as a whole.”

In her essay , Whitaker explains the relevance of history in policymaking and attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic. She first discusses the human tendency to blame others for things beyond our control, giving historical examples involving discrimination against particular groups based on race or sexual orientation. She then describes the enforcement of health measures during the black plague, adding that religion and science do not necessarily contradict each other. From a historical perspective, we might just feel better about the situations we are in, as these issues have repeatedly afflicted humanity.

In your essay , write about the lessons we can learn from studying history. What has history taught us about human nature? What mistakes have we made in the past that we can use to prevent future catastrophes? Explain your position in detail and support it with sufficient evidence.

We have been left with many reminders of our history, including monuments, historical documents , paintings, and sculptures. First, choose a primary historical source , explain what it is, and discuss what you can infer about the period it is from. Then, provide context by using external sources , such as articles.

What historical event interests you? Choose one, whether it be a devastating war, the establishment of a new country, or a groundbreaking new invention, and write about it. Explain what exactly transpired in the event and explain why you chose it. You can also include possible lessons you could learn from it. You can use documentaries, history books, and online sources to understand the topic better.

Research the history of a country of your choice and write your essay on it. Include how it was formed, essential people, and important events. The country need not be your home country; choose any country and write clearly. You can also focus on a specific period in your country’s history if you wish to go more in-depth.

For a personal angle on your essay , you can write about your family’s history if there is anything you feel is noteworthy about it. Do you have any famous ancestors? Did any family members serve in the military? If you have the proper sources , discuss as much as you can about your family history and perhaps explain why it is essential to you.

Throughout history, war has always hurt one or both sides. Choose one crucial historical war and write about its effects. Briefly discuss what occurred in the war and how it ended, and describe its impact on either or both sides. Feel free to focus on one aspect, territory, culture, or the economy.

From the spread of Christianity to the horrible practice of slavery, research any topic you wish and write about its history. How did it start, and what is its state today? You need not go too broad; the scope of your essay is your decision, as long as it is written clearly and adequately supported.

For help with your essay , check our round-up of best essay writing apps .If you’re looking for inspiration, check out our round-up of essay topics about nature .

How to Write a History Essay with Outline, Tips, Examples and More

Samuel Gorbold

Before we get into how to write a history essay, let's first understand what makes one good. Different people might have different ideas, but there are some basic rules that can help you do well in your studies. In this guide, we won't get into any fancy theories. Instead, we'll give you straightforward tips to help you with historical writing. So, if you're ready to sharpen your writing skills, let our history essay writing service explore how to craft an exceptional paper.

What is a History Essay?

A history essay is an academic assignment where we explore and analyze historical events from the past. We dig into historical stories, figures, and ideas to understand their importance and how they've shaped our world today. History essay writing involves researching, thinking critically, and presenting arguments based on evidence.

Moreover, history papers foster the development of writing proficiency and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively. They also encourage students to engage with primary and secondary sources, enhancing their research skills and deepening their understanding of historical methodology. Students can benefit from utilizing essay writers services when faced with challenging assignments. These services provide expert assistance and guidance, ensuring that your history papers meet academic standards and accurately reflect your understanding of the subject matter.

History Essay Outline

.png)

The outline is there to guide you in organizing your thoughts and arguments in your essay about history. With a clear outline, you can explore and explain historical events better. Here's how to make one:

Introduction

- Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote related to your topic.

- Background Information: Provide context on the historical period, event, or theme you'll be discussing.

- Thesis Statement: Present your main argument or viewpoint, outlining the scope and purpose of your history essay.

Body paragraph 1: Introduction to the Historical Context

- Provide background information on the historical context of your topic.

- Highlight key events, figures, or developments leading up to the main focus of your history essay.

Body paragraphs 2-4 (or more): Main Arguments and Supporting Evidence

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific argument or aspect of your thesis.

- Present evidence from primary and secondary sources to support each argument.

- Analyze the significance of the evidence and its relevance to your history paper thesis.

Counterarguments (optional)

- Address potential counterarguments or alternative perspectives on your topic.

- Refute opposing viewpoints with evidence and logical reasoning.

- Summary of Main Points: Recap the main arguments presented in the body paragraphs.

- Restate Thesis: Reinforce your thesis statement, emphasizing its significance in light of the evidence presented.

- Reflection: Reflect on the broader implications of your arguments for understanding history.

- Closing Thought: End your history paper with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

References/bibliography

- List all sources used in your research, formatted according to the citation style required by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include both primary and secondary sources, arranged alphabetically by the author's last name.

Notes (if applicable)

- Include footnotes or endnotes to provide additional explanations, citations, or commentary on specific points within your history essay.

History Essay Format

Adhering to a specific format is crucial for clarity, coherence, and academic integrity. Here are the key components of a typical history essay format:

Font and Size

- Use a legible font such as Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri.

- The recommended font size is usually 12 points. However, check your instructor's guidelines, as they may specify a different size.

- Set 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Double-space the entire essay, including the title, headings, body paragraphs, and references.

- Avoid extra spacing between paragraphs unless specified otherwise.

- Align text to the left margin; avoid justifying the text or using a centered alignment.

Title Page (if required):

- If your instructor requires a title page, include the essay title, your name, the course title, the instructor's name, and the date.

- Center-align this information vertically and horizontally on the page.

- Include a header on each page (excluding the title page if applicable) with your last name and the page number, flush right.

- Some instructors may require a shortened title in the header, usually in all capital letters.

- Center-align the essay title at the top of the first page (if a title page is not required).

- Use standard capitalization (capitalize the first letter of each major word).

- Avoid underlining, italicizing, or bolding the title unless necessary for emphasis.

Paragraph Indentation:

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches or use the tab key.

- Do not insert extra spaces between paragraphs unless instructed otherwise.

Citations and References:

- Follow the citation style specified by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include in-text citations whenever you use information or ideas from external sources.

- Provide a bibliography or list of references at the end of your history essay, formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

- Typically, history essays range from 1000 to 2500 words, but this can vary depending on the assignment.

How to Write a History Essay?

Historical writing can be an exciting journey through time, but it requires careful planning and organization. In this section, we'll break down the process into simple steps to help you craft a compelling and well-structured history paper.

Analyze the Question

Before diving headfirst into writing, take a moment to dissect the essay question. Read it carefully, and then read it again. You want to get to the core of what it's asking. Look out for keywords that indicate what aspects of the topic you need to focus on. If you're unsure about anything, don't hesitate to ask your instructor for clarification. Remember, understanding how to start a history essay is half the battle won!

Now, let's break this step down:

- Read the question carefully and identify keywords or phrases.

- Consider what the question is asking you to do – are you being asked to analyze, compare, contrast, or evaluate?

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or requirements provided in the question.

- Take note of the time period or historical events mentioned in the question – this will give you a clue about the scope of your history essay.

Develop a Strategy

With a clear understanding of the essay question, it's time to map out your approach. Here's how to develop your historical writing strategy:

- Brainstorm ideas : Take a moment to jot down any initial thoughts or ideas that come to mind in response to the history paper question. This can help you generate a list of potential arguments, themes, or points you want to explore in your history essay.

- Create an outline : Once you have a list of ideas, organize them into a logical structure. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and presents your thesis statement – the main argument or point you'll be making in your history essay. Then, outline the key points or arguments you'll be discussing in each paragraph of the body, making sure they relate back to your thesis. Finally, plan a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your history paper thesis.

- Research : Before diving into writing, gather evidence to support your arguments. Use reputable sources such as books, academic journals, and primary documents to gather historical evidence and examples. Take notes as you research, making sure to record the source of each piece of information for proper citation later on.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate potential counterarguments to your history paper thesis and think about how you'll address them in your essay. Acknowledging opposing viewpoints and refuting them strengthens your argument and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Set realistic goals : Be realistic about the scope of your history essay and the time you have available to complete it. Break down your writing process into manageable tasks, such as researching, drafting, and revising, and set deadlines for each stage to stay on track.

Start Your Research

Now that you've grasped the history essay topic and outlined your approach, it's time to dive into research. Here's how to start:

- Ask questions : What do you need to know? What are the key points to explore further? Write down your inquiries to guide your research.

- Explore diverse sources : Look beyond textbooks. Check academic journals, reliable websites, and primary sources like documents or artifacts.

- Consider perspectives : Think about different viewpoints on your topic. How have historians analyzed it? Are there controversies or differing interpretations?

- Take organized notes : Summarize key points, jot down quotes, and record your thoughts and questions. Stay organized using spreadsheets or note-taking apps.

- Evaluate sources : Consider the credibility and bias of each source. Are they peer-reviewed? Do they represent a particular viewpoint?

Establish a Viewpoint

By establishing a clear viewpoint and supporting arguments, you'll lay the foundation for your compelling historical writing:

- Review your research : Reflect on the information gathered. What patterns or themes emerge? Which perspectives resonate with you?

- Formulate a thesis statement : Based on your research, develop a clear and concise thesis that states your argument or interpretation of the topic.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate objections to your history paper thesis. Are there alternative viewpoints or evidence that you need to address?

- Craft supporting arguments : Outline the main points that support your thesis. Use evidence from your research to strengthen your arguments.

- Stay flexible : Be open to adjusting your viewpoint as you continue writing and researching. New information may challenge or refine your initial ideas.

Structure Your Essay

Now that you've delved into the depths of researching historical events and established your viewpoint, it's time to craft the skeleton of your essay: its structure. Think of your history essay outline as constructing a sturdy bridge between your ideas and your reader's understanding. How will you lead them from point A to point Z? Will you follow a chronological path through history or perhaps dissect themes that span across time periods?

And don't forget about the importance of your introduction and conclusion—are they framing your narrative effectively, enticing your audience to read your paper, and leaving them with lingering thoughts long after they've turned the final page? So, as you lay the bricks of your history essay's architecture, ask yourself: How can I best lead my audience through the maze of time and thought, leaving them enlightened and enriched on the other side?

Create an Engaging Introduction

Creating an engaging introduction is crucial for capturing your reader's interest right from the start. But how do you do it? Think about what makes your topic fascinating. Is there a surprising fact or a compelling story you can share? Maybe you could ask a thought-provoking question that gets people thinking. Consider why your topic matters—what lessons can we learn from history?

Also, remember to explain what your history essay will be about and why it's worth reading. What will grab your reader's attention and make them want to learn more? How can you make your essay relevant and intriguing right from the beginning?

Develop Coherent Paragraphs

Once you've established your introduction, the next step is to develop coherent paragraphs that effectively communicate your ideas. Each paragraph should focus on one main point or argument, supported by evidence or examples from your research. Start by introducing the main idea in a topic sentence, then provide supporting details or evidence to reinforce your point.

Make sure to use transition words and phrases to guide your reader smoothly from one idea to the next, creating a logical flow throughout your history essay. Additionally, consider the organization of your paragraphs—is there a clear progression of ideas that builds upon each other? Are your paragraphs unified around a central theme or argument?

Conclude Effectively

Concluding your history essay effectively is just as important as starting it off strong. In your conclusion, you want to wrap up your main points while leaving a lasting impression on your reader. Begin by summarizing the key points you've made throughout your history essay, reminding your reader of the main arguments and insights you've presented.

Then, consider the broader significance of your topic—what implications does it have for our understanding of history or for the world today? You might also want to reflect on any unanswered questions or areas for further exploration. Finally, end with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action that encourages your reader to continue thinking about the topic long after they've finished reading.

Reference Your Sources

Referencing your sources is essential for maintaining the integrity of your history essay and giving credit to the scholars and researchers who have contributed to your understanding of the topic. Depending on the citation style required (such as MLA, APA, or Chicago), you'll need to format your references accordingly. Start by compiling a list of all the sources you've consulted, including books, articles, websites, and any other materials used in your research.

Then, as you write your history essay, make sure to properly cite each source whenever you use information or ideas that are not your own. This includes direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. Remember to include all necessary information for each source, such as author names, publication dates, and page numbers, as required by your chosen citation style.

Review and Ask for Advice

As you near the completion of your history essay writing, it's crucial to take a step back and review your work with a critical eye. Reflect on the clarity and coherence of your arguments—are they logically organized and effectively supported by evidence? Consider the strength of your introduction and conclusion—do they effectively capture the reader's attention and leave a lasting impression? Take the time to carefully proofread your history essay for any grammatical errors or typos that may detract from your overall message.

Furthermore, seeking advice from peers, mentors, or instructors can provide valuable insights and help identify areas for improvement. Consider sharing your essay with someone whose feedback you trust and respect, and be open to constructive criticism. Ask specific questions about areas you're unsure about or where you feel your history essay may be lacking. If you need further assistance, don't hesitate to reach out and ask for help. You can even consider utilizing services that offer to write a discussion post for me , where you can engage in meaningful conversations with others about your essay topic and receive additional guidance and support.

History Essay Example

In this section, we offer an example of a history essay examining the impact of the Industrial Revolution on society. This essay demonstrates how historical analysis and critical thinking are applied in academic writing. By exploring this specific event, you can observe how historical evidence is used to build a cohesive argument and draw meaningful conclusions.

FAQs about History Essay Writing

How to write a history essay introduction, how to write a conclusion for a history essay, how to write a good history essay.

Samuel Gorbold , a seasoned professor with over 30 years of experience, guides students across disciplines such as English, psychology, political science, and many more. Together with EssayHub, he is dedicated to enhancing student understanding and success through comprehensive academic support.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

The Next Decade Could Be Even Worse

A historian believes he has discovered iron laws that predict the rise and fall of societies. He has bad news.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

P eter Turchin , one of the world’s experts on pine beetles and possibly also on human beings, met me reluctantly this summer on the campus of the University of Connecticut at Storrs, where he teaches. Like many people during the pandemic, he preferred to limit his human contact. He also doubted whether human contact would have much value anyway, when his mathematical models could already tell me everything I needed to know.

But he had to leave his office sometime. (“One way you know I am Russian is that I cannot think sitting down,” he told me. “I have to go for a walk.”) Neither of us had seen much of anyone since the pandemic had closed the country several months before. The campus was quiet. “A week ago, it was even more like a neutron bomb hit,” Turchin said. Animals were timidly reclaiming the campus, he said: squirrels, woodchucks, deer, even an occasional red-tailed hawk. During our walk, groundskeepers and a few kids on skateboards were the only other representatives of the human population in sight.

From the June 2020 issue: We are living in a failed state

The year 2020 has been kind to Turchin, for many of the same reasons it has been hell for the rest of us. Cities on fire, elected leaders endorsing violence, homicides surging—to a normal American, these are apocalyptic signs. To Turchin, they indicate that his models, which incorporate thousands of years of data about human history, are working. (“Not all of human history,” he corrected me once. “Just the last 10,000 years.”) He has been warning for a decade that a few key social and political trends portend an “age of discord,” civil unrest and carnage worse than most Americans have experienced. In 2010, he predicted that the unrest would get serious around 2020, and that it wouldn’t let up until those social and political trends reversed. Havoc at the level of the late 1960s and early ’70s is the best-case scenario; all-out civil war is the worst.

The fundamental problems, he says, are a dark triad of social maladies: a bloated elite class, with too few elite jobs to go around; declining living standards among the general population; and a government that can’t cover its financial positions. His models, which track these factors in other societies across history, are too complicated to explain in a nontechnical publication. But they’ve succeeded in impressing writers for nontechnical publications, and have won him comparisons to other authors of “megahistories,” such as Jared Diamond and Yuval Noah Harari. The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat had once found Turchin’s historical modeling unpersuasive, but 2020 made him a believer: “At this point,” Douthat recently admitted on a podcast, “I feel like you have to pay a little more attention to him.”

Diamond and Harari aimed to describe the history of humanity. Turchin looks into a distant, science-fiction future for peers. In War and Peace and War (2006), his most accessible book, he likens himself to Hari Seldon, the “maverick mathematician” of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, who can foretell the rise and fall of empires. In those 10,000 years’ worth of data, Turchin believes he has found iron laws that dictate the fates of human societies.