- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Critical thinking in...

Critical Thinking in medical education: When and How?

Rapid response to:

Critical thinking in healthcare and education

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive skill for the individuals involved in various healthcare domains such as doctors, nurses, lab assistants, patients and so on, as is emphasized by the Authors. Recent evidence suggests that critical thinking is being perceived/evaluated as a domain-general construct and it is less distinguishable from that of general cognitive abilities [1].

People cannot think critically about topics for which they have little knowledge. Critical thinking should be viewed as a domain-specific construct that evolves as an individual acquires domain-specific knowledge [1]. For instance, most common people have no basis for prioritizing patients in the emergency department to be shifted to the only bed available in the intensive care unit. Medical professionals who could thinking critically in their own discipline would have difficulty thinking critically about problems in other fields. Therefore, ‘domain-general’ critical thinking training and evaluation could be non-specific and might not benefit the targeted domain i.e. medical profession.

Moreover, the literature does not demonstrate that it is possible to train universally effective critical thinking skills [1]. As medical teachers, we can start building up student’s critical thinking skill by contingent teaching-learning environment wherein one should encourage reasoning and analytics, problem solving abilities and welcome new ideas and opinions [2]. But at the same time, one should continue rather tapering the critical skills as one ascends towards a specialty, thereby targeting ‘domain-specific’ critical thinking.

For the benefit of healthcare, tools for training and evaluating ‘domain-specific’ critical thinking should be developed for each of the professional knowledge domains such as doctors, nurses, lab technicians and so on. As the Authors rightly pointed out, this humongous task can be accomplished only with cross border collaboration among cognitive neuroscientists, psychologists, medical education experts and medical professionals.

References 1. National Research Council. (2011). Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop. J.A. Koenig, Rapporteur. Committee on the Assessment of 21st Century Skills. Board on Testing and Assessment, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2. Mafakheri Laleh M, Mohammadimehr M, Zargar Balaye Jame S. Designing a model for critical thinking development in AJA University of Medical Sciences. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2016 Oct;4(4):179–87.

Competing interests: No competing interests

Critical Thinking in Medicine and Health

- First Online: 01 March 2020

Cite this chapter

- Louise Cummings 2

741 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter addresses why there is a need for experts and lay people to think critically about medicine and health. It will be argued that illogical, misleading, and contradictory information in medicine and health can have pernicious consequences, including patient harm and poor compliance with health recommendations. Our cognitive resources are our only bulwark to the misinformation and faulty logic that exists in medicine and health. One resource in particular—reasoning—can counter the flawed thinking that pervades many medical and health issues. This chapter examines how concepts such as reasoning, logic and argument must be conceptualised somewhat differently (namely, in non-deductive terms) to accommodate the rationality of the informal fallacies. It also addresses the relevance of the informal fallacies to medicine and health and considers how these apparently defective arguments are a source of new analytical possibilities in both domains.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Albano, J. D., Ward, E., Jemal, A., Anderson, R., Cokkinides, V. E., Murray, T., et al. (2007). Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99 (18), 1384–1394.

Article Google Scholar

Coxon, J., & Rees, J. (2015). Avoiding medical errors in general practice. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 6 (4), 13–17.

Google Scholar

Croskerry, P. (2003). The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Academic Medicine, 78 (8), 775–780.

Cummings, L. (2002). Reasoning under uncertainty: The role of two informal fallacies in an emerging scientific inquiry. Informal Logic, 22 (2), 113–136.

Cummings, L. (2004). Analogical reasoning as a tool of epidemiological investigation. Argumentation, 18 (4), 427–444.

Cummings, L. (2009). Emerging infectious diseases: Coping with uncertainty. Argumentation, 23 (2), 171–188.

Cummings, L. (2010). Rethinking the BSE crisis: A study of scientific reasoning under uncertainty . Dordrecht: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Cummings, L. (2011). Considering risk assessment up close: The case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Health, Risk & Society, 13 (3), 255–275.

Cummings, L. (2012a). Scaring the public: Fear appeal arguments in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 32 (1), 25–50.

Cummings, L. (2012b). The public health scientist as informal logician. International Journal of Public Health, 57 (3), 649–650.

Cummings, L. (2013a). Public health reasoning: Much more than deduction. Archives of Public Health, 71 (1), 25.

Cummings, L. (2013b). Circular reasoning in public health. Cogency, 5 (2), 35–76.

Cummings, L. (2014a). Informal fallacies as cognitive heuristics in public health reasoning. Informal Logic, 34 (1), 1–37.

Cummings, L. (2014b). The ‘trust’ heuristic: Arguments from authority in public health. Health Communication, 29 (10), 1043–1056.

Cummings, L. (2014c). Coping with uncertainty in public health: The use of heuristics. Public Health, 128 (4), 391–394.

Cummings, L. (2014d). Circles and analogies in public health reasoning. Inquiry, 29 (2), 35–59.

Cummings, L. (2014e). Analogical reasoning in public health. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 3 (2), 169–197.

Cummings, L. (2015). Reasoning and public health: New ways of coping with uncertainty . Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Fowler, F. J., Jr., Levin, C. A., & Sepucha, K. R. (2011). Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Affairs, 30 (4), 699–706.

Graber, M. L., Franklin, N., & Gordon, R. (2005). Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165 (13), 1493–1499.

Hamblin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies . London: Methuen.

Johnson, R. H. (2011). Informal logic and deductivism. Studies in Logic, 4 (1), 17–37.

Kahane, H. (1971). Logic and contemporary rhetoric: The use of reason in everyday life . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Loucks, E. B., Buka, S. L., Rogers, M. L., Liu, T., Kawachi, I., Kubzansky, L. D., et al. (2012). Education and coronary heart disease risk associations may be affected by early life common prior causes: A propensity matching analysis. Annals of Epidemiology, 22 (4), 221–232.

Saposnik, G., Redelmeier, D., Ruff, C. C., & Tobler, P. N. (2016). Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: A systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16, 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1 .

Trowbridge, R. L. (2008). Twelve tips for teaching avoidance of diagnostic errors. Medical Teacher, 30, 496–500.

Walton, D. N. (1985a). Are circular arguments necessarily vicious? American Philosophical Quarterly, 22 (4), 263–274.

Walton, D. N. (1985b). Arguer’s Position . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1987). The ad hominem argument as an informal fallacy. Argumentation, 1 (3), 317–331.

Walton, D. N. (1991). Begging the question: Circular reasoning as a tactic of argumentation . New York: Greenwood Press.

Walton, D. N. (1992). Plausible argument in everyday conversation . Albany: SUNY Press.

Walton, D. N. (1996). Argumentation schemes for presumptive reasoning . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Walton, D. N. (2010). Why fallacies appear to be better arguments than they are. Informal Logic, 30 (2), 159–184.

Weingart, S. N., Wilson, R. M., Gibberd, R. W., & Harrison, B. (2000). Epidemiology of medical error. Western Journal of Medicine, 172 (6), 390–393.

Woods, J. (1995). Appeal to force. In H. V. Hansen & R. C. Pinto (Eds.), Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings (pp. 240–250). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Woods, J. (2004). The death of argument: Fallacies in agent-based reasoning . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Woods, J. (2007). Lightening up on the ad hominem. Informal Logic, 27 (1), 109–134.

Woods, J. (2008). Begging the question is not a fallacy. In C. Dégremont, L. Keiff, & H. Rükert (Eds.), Dialogues, logics and other strange things: Essays in honour of Shahid Rahman (pp. 523–544). London: College Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Louise Cummings

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Louise Cummings .

Chapter Summary

Medicine and health have tended to be overlooked in the critical thinking literature . And yet robust critical thinking skills are needed to evaluate the large number and range of health messages that we are exposed to on a daily basis.

An ability to think critically helps us to make better personal health choices and to uncover biases and errors in health messages and other information. An ability to think critically allows us to make informed decisions about medical treatments and is vital to efforts to reduce medical diagnostic errors.

A key element in critical thinking is the ability to distinguish strong or valid reasoning from weak or invalid reasoning. When an argument is weak or invalid, it is called a ‘fallacy’ or a ‘fallacious argument’.

The informal fallacies are so-called on account of the presence of epistemic and dialectical flaws that cannot be captured by formal logic . They have been discussed by many generations of philosophers and logicians , beginning with Aristotle .

Historically, philosophers and logicians have taken a pejorative view of the informal fallacies. Much of the criticism of these arguments is related to a latent deductivism in logic , the notion that arguments should be evaluated according to deductive standards of validity and soundness . Against deductive standards and norms, many reasonable arguments are judged to be fallacies.

Developments in logic , particularly the teaching of logic, forced a reconsideration of the prominence afforded to deductive logic in the evaluation of arguments. New criteria based on presumptive reasoning and plausible argument started to emerge. Against this backdrop, non-fallacious variants of most of the informal fallacies began to be described for the first time.

Today, some argument analysts characterize non-fallacious variants of the informal fallacies in terms of cognitive heuristics . During reasoning , these heuristics function as mental shortcuts, allowing us to bypass knowledge and come to judgement about complex health problems.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Sharples, J. M., Oxman, A. D., Mahtani, K. R., Chalmers, I., Oliver, S., Collins, K., Austvoll-Dahlgren, A., & Hoffmann, T. (2017). Critical thinking in healthcare and education. British Medical Journal, 357 : j2234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2234 .

The authors examine the role of critical thinking in medicine and healthcare, arguing that critical thinking skills are essential for doctors and patients. They describe an international project that involves collaboration between education and health. Its aim is to develop a curriculum and learning resources for critical thinking about any action that is claimed to improve health.

Hitchcock, D. (2017). On reasoning and argument: Essays in informal logic and on critical thinking . Cham: Switzerland: Springer.

This collection of essays provides more advanced reading on several of the topics addressed in this chapter, including the fallacies, informal logic , and the teaching of critical thinking . Chapter 25 considers if fallacies have a place in the teaching of critical thinking and reasoning skills.

Hansen, H. V., & Pinto, R. C. (Eds.). (1995). Fallacies: Classical and contemporary readings . University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

This edited collection of 24 chapters contains historical selections on the fallacies, contemporary theory and criticism, and analyses of specific fallacies. It also examines fallacies and teaching. There are chapters on four of the fallacies that will be examined in this book: appeal to force; appeal to ignorance ; appeal to authority; and post hoc ergo propter hoc .

Diagnostic errors are a significant cause of death and serious injury in patients. Many of these errors are related to cognitive factors. Trowbridge ( 2008 ) has devised twelve tips to familiarize medical students and physician trainees with the cognitive underpinnings of diagnostic errors. One of these tips is to explicitly describe heuristics and how they affect clinical reasoning . These heuristics include the following:

Representativeness —a patient’s presentation is compared to a ‘typical’ case of specific diagnoses.

Availability —physicians arrive at a diagnosis based on what is easily accessible in their minds, rather than what is actually most probable.

Anchoring —physicians may settle on a diagnosis early in the diagnostic process and subsequently become ‘anchored’ in that diagnosis.

Confirmation bias —as a result of anchoring, physicians may discount information discordant with the original diagnosis and accept only that which supports the diagnosis.

Using the above information, identify any heuristics and biases that occur in the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: A 60-year-old man has epigastric pain and nausea. He is sitting forward clutching his abdomen. He has a history of several bouts of alcoholic pancreatitis. He states that he felt similar during these bouts to what he is currently feeling. The patient states that he has had no alcohol in many years. He has normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. He is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. It is eventually discovered that he has had acute myocardial infarction.

Scenario 2: A 20-year-old, healthy man presents with sudden onset of severe, sharp chest pain and back pain. Based on these symptoms, he is suspected of having a dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm. (In an aortic dissection, there is a separation of the layers within the wall of the aorta, the large blood vessel branching off the heart.) He is eventually diagnosed with pleuritis (inflammation of the pleura, the thin, transparent, two-layered membrane that covers the lungs).

Many of the logical terms that were introduced in this chapter also have non-logical uses in everyday language. Below are several examples of the use of these terms. For each example, indicate if the word in italics has a logical or a non - logical meaning or use:

University ‘safe spaces’ are a dangerous fallacy —they do not exist in the real world ( The Telegraph , 13 February 2017).

The MRI findings beg the question as to whether a careful ultrasound examination might have yielded some of the same information on haemorrhages ( British Medical Journal: Fetal & Neonatal , 2011).

The youth justice system is a slippery slope of failure ( The Sydney Morning Herald , 26 July 2016).

The EU countered with its own gastronomic analogy , saying that “cherry picking” the best bits of the EU would not be tolerated ( BBC News , 28 July 2017).

As Ebola spreads, so have several fallacies ( The New York Times , 23 October 2014).

Removing the statue of Confederacy Army General Robert E. Lee no more puts us on a slippery slope towards ousting far more nuanced figures from the public square than building the statue in the first place put us on a slippery slope toward, say, putting up statues of Hitler outside of Holocaust museums or of Ho Chi Minh at Vietnam War memorials ( Chicago Tribune , 16 August 2017).

We can expand the analogy a bit and think of a culture as something akin to a society’s immune system—it works best when it is exposed to as many foreign bodies as possible ( New Zealand Herald , 4 May 2010).

The Josh Norman Bowl begs the question : What’s an elite cornerback worth? ( The Washington Post , 17 December 2016).

The intuition behind these analogies is simple: As a homeowner, I generally have the right to exclude whoever I want from my property. I don’t even have to have a good justification for the exclusion. I can choose to bar you from my home for virtually any reason I want, or even just no reason at all. Similarly, a nation has the right to bar foreigners from its land for almost any reason it wants, or perhaps even no reason at all ( The Washington Post , 6 August 2017).

Legalising assisted suicide is a slippery slope toward widespread killing of the sick, Members of Parliament and peers were told yesterday ( Mail Online , 9 July 2014).

In the Special Topic ‘What’s in a name?’, an example of a question-begging argument from the author’s recent personal experience was used. How would you reconstruct the argument in this case to illustrate the presence of a fallacy?

On 9 July 2017, the effect of coconut oil on health was also discussed in an article in The Guardian entitled ‘Coconut oil: Are the health benefits a big fat lie?’ The following extract is taken from that article. (a) What type of reasoning is the author using in this extract? In your response, you should reconstruct the argument by presenting its premises and conclusion . Also, is this argument valid or fallacious in this particular context?

When it comes to superfoods, coconut oil presses all the buttons: it’s natural, it’s enticingly exotic, it’s surrounded by health claims and at up to £8 for a 500 ml pot at Tesco, it’s suitably pricey. But where this latest superfood differs from benign rivals such as blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado is that a diet rich in coconut oil may actually be bad for us.

The article in The Guardian also makes extensive use of expert opinion. Two such opinions are shown below. (b) What three linguistic devices does the author use to confer expertise or authority on the individuals who advance these opinions?

Christine Williams, professor of human nutrition at the University of Reading, states: “There is very limited evidence of beneficial health effects of this oil”.

Tom Sanders, emeritus professor of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, says: “It is a poor source of vitamin E compared with other vegetable oils”.

The author of the article in The Guardian went on to summarize the findings of a study by two researchers that was published in the British Nutrition Foundation’s Nutrition Bulletin. The author’s summary included the following statement: There is no good evidence that coconut oil helps boost mental performance or prevent Alzheimer’s disease . (c) In what type of informal fallacy might this statement be a premise ?

Scenario 1: An anchoring error has occurred in which the patient is given a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis early in the diagnostic process. The clinician becomes anchored in this diagnosis, with the result that he overlooks two pieces of information that would have allowed this diagnosis to be disconfirmed—the fact that the patient has reported no alcohol use in many years and the presence of normal blood levels of pancreatic enzymes. By dismissing this information, the clinician is also showing a confirmation bias —he attends only to information that confirms his original diagnosis.

Scenario 2: A representativeness error has occurred. The patient’s presentation is typical of aortic dissection. However, this condition can be dismissed in favour of conditions like pleuritis or pneumothorax on account of the fact that aortic dissection is exceptionally rare in 20-year-olds.

(2) (a) non-logical; (b) non-logical; (c) non-logical; (d) non-logical; (e) non-logical; (f) logical; (g) logical; (h) non-logical; (i) logical; (j) logical

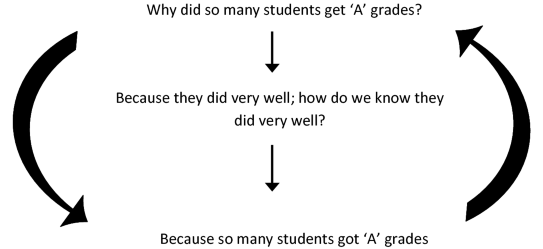

(3) The fallacy can be illustrated as follows. The head of department asks the question ‘Why did so many of these students get ‘A’ grades’? He receives the reply ‘Because they did very well’. But someone might reasonably ask ‘How do we know that they did very well?’ To which the reply is ‘Because so many students got ‘A’ grades’. The reasoning can be reconstructed in diagram form as follows:

The author is using an analogical argument , which has the following form:

P1: Blueberries, goji berries, kale, avocado and coconut oil are natural, exotic, pricey and surrounded by health claims.

P2: Blueberries, goji berries, kale and avocado have health benefits.

C: Coconut oil has health benefits.

This is a false analogy , or a fallacious analogical argument , because coconut oil does not share with these other superfoods the property or attribute < has health benefits >.

The author uses academic rank, field of specialization, and university affiliation to confer authority or expertise on individuals who advance expert opinions.

This statement could be a premise in an argument from ignorance .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cummings, L. (2020). Critical Thinking in Medicine and Health. In: Fallacies in Medicine and Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28513-5_1

Published : 01 March 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-28512-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-28513-5

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Medical Student Guide For Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an essential cognitive skill for every individual but is a crucial component for healthcare professionals such as doctors, nurses and dentists. It is a skill that should be developed and trained, not just during your career as a doctor, but before that when you are still a medical student.

To be more effective in their studies, students must think their way through abstract problems, work in teams and separate high quality from low quality information. These are the same qualities that today's medical students are supposed to possess regardless of whether they graduate in the UK or study medicine in Europe .

In both well-defined and ill-defined medical emergencies, doctors are expected to make competent decisions. Critical thinking can help medical students and doctors achieve improved productivity, better clinical decision making, higher grades and much more.

This article will explain why critical thinking is a must for people in the medical field.

Definition of Critical Thinking

You can find a variety of definitions of Critical Thinking (CT). It is a term that goes back to the Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates and his teaching practice and vision. Critical thinking and its meaning have changed over the years, but at its core always will be the pursuit of proper judgment.

We can agree on one thing. Critical thinkers question every idea, assumption, and possibility rather than accepting them at once.

The most basic definition of CT is provided by Beyer (1995):

"Critical thinking means making reasoned judgements."

In other words, it is the ability to think logically about what to do and/or believe. It also includes the ability to think critically and independently. CT is the process of identifying, analysing, and then making decisions about a particular topic, advice, opinion or challenge that we are facing.

Steps to critical thinking

There is no universal standard for becoming a critical thinker. It is more like a unique journey for each individual. But as a medical student, you have already so much going on in your academic and personal life. This is why we created a list with 6 steps that will help you develop the necessary skills for critical thinking.

1. Determine the issue or question

The first step is to answer the following questions:

- What is the problem?

- Why is it important?

- Why do we need to find a solution?

- Who is involved?

By answering them, you will define the situation and acquire a deeper understanding of the problem and of any factors that may impact it.

Only after you have a clear picture of the issue and people involved can you start to dive deeper into the problem and search for a solution.

2. Research

Nowadays, we are flooded with information. We have an unlimited source of knowledge – the Internet.

Before choosing which medical schools to apply to, most applicants researched their desired schools online. Some of the areas you might have researched include:

- If the degree is recognised worldwide

- Tuition fees

- Living costs

- Entry requirements

- Competition for entry

- Number of exams

- Programme style

Having done the research, you were able to make an informed decision about your medical future based on the gathered information. Our list may be a little different to yours but that's okay. You know what factors are most important and relevant to you as a person.

The process you followed when choosing which medical school to apply to also applies to step 2 of critical thinking. As a medical student and doctor, you will face situations when you have to compare different arguments and opinions about an issue. Independent research is the key to the right clinical decisions. Medical and dentistry students have to be especially careful when learning from online sources. You shouldn't believe everything you read and take it as the absolute truth. So, here is what you need to do when facing a medical/study argument:

- Gather relevant information from all available reputable sources

- Pay attention to the salient points

- Evaluate the quality of the information and the level of evidence (is it just an opinion, or is it based upon a clinical trial?)

Once you have all the information needed, you can start the process of analysing it. It’s helpful to write down the strong and weak points of the various recommendations and identify the most evidence-based approach.

Here is an example of a comparison between two online course platforms , which shows their respective strengths and weaknesses.

When recommendations or conclusions are contradictory, you will need to make a judgement call on which point of view has the strongest level of evidence to back it up. You should leave aside your feelings and analyse the problem from every angle possible. In the end, you should aim to make your decision based on the available evidence, not assumptions or bias.

4. Be careful about confirmation bias

It is in our nature to want to confirm our existing ideas rather than challenge them. You should try your best to strive for objectivity while evaluating information.

Often, you may find yourself reading articles that support your ideas, but why not broaden your horizons by learning about the other viewpoint?

By doing so, you will have the opportunity to get closer to the truth and may even find unexpected support and evidence for your conclusion.

Curiosity will keep you on the right path. However, if you find yourself searching for information or confirmation that aligns only with your opinion, then it’s important to take a step back. Take a short break, acknowledge your bias, clear your mind and start researching all over.

5. Synthesis

As we have already mentioned a couple of times, medical students are preoccupied with their studies. Therefore, you have to learn how to synthesise information. This is where you take information from multiple sources and bring the information together. Learning how to do this effectively will save you time and help you make better decisions faster.

You will have already located and evaluated your sources in the previous steps. You now have to organise the data into a logical argument that backs up your position on the problem under consideration.

6. Make a decision

Once you have gathered and evaluated all the available evidence, your last step is to make a logical and well-reasoned conclusion.

By following this process you will ensure that whatever decision you make can be backed up if challenged

Why is critical thinking so important for medical students?

The first and most important reason for mastering critical thinking is that it will help you to avoid medical and clinical errors during your studies and future medical career.

Another good reason is that you will be able to identify better alternative options for diagnoses and treatments. You will be able to find the best solution for the patient as a whole which may be different to generic advice specific to the disease.

Furthermore, thinking critically as a medical student will boost your confidence and improve your knowledge and understanding of subjects.

In conclusion, critical thinking is a skill that can be learned and improved. It will encourage you to be the best version of yourself and teach you to take responsibility for your actions.

Critical thinking has become an essential for future health care professionals and you will find it an invaluable skill throughout your career.

We’ll keep you updated

Science-Based Medicine

Exploring issues and controversies in the relationship between science and medicine

Critical Thinking in Medicine

Cognitive Errors and Diagnostic Mistakes is a superb new guide to critical thinking in medicine written by Jonathan Howard. It explains how our psychological foibles regularly bias and betray us, leading to diagnostic mistakes. Learning critical thinking skills is essential but difficult. Every known cognitive error is illustrated with memorable patient stories.

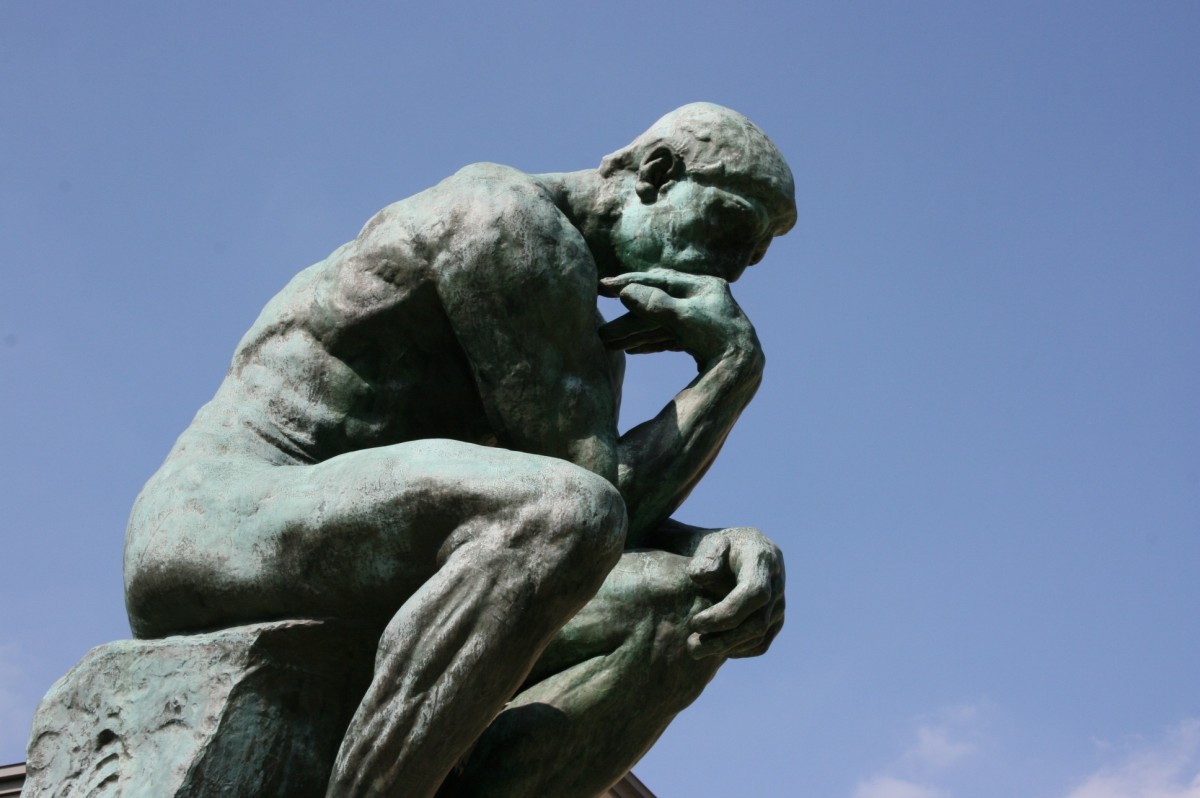

Rodin’s Thinker is doing his best to think but if he hasn’t learned critical thinking skills, he is likely to make mistakes. The human brain is prone to a multitude of cognitive errors.

Critical thinking in medicine is what the Science-Based Medicine ( SBM ) blog is all about. Jonathan Howard has written a superb book, Cognitive Errors and Diagnostic Mistakes: A Case-Based Guide to Critical Thinking in Medicine , that epitomizes the message of SBM . In fact, in the Acknowledgements, he credits the entire team at SBM for teaching him “an enormous amount about skepticism and critical thinking”, and he specifically thanks Steven Novella, Harriet Hall (moi!), and David Gorski.

Dr. Howard is a neurologist and psychiatrist at NYU and Bellevue Hospital. The book is a passionate defense of science and a devastating critique of Complementary and Alternative Medicine ( CAM ) and pseudoscience. Its case-based approach is a stroke of genius. We humans are story-tellers; we are far more impressed by stories than by studies or by textbook definitions of a disease. Dr. Howard points out that “Anecdotes are part of the very cognition that allows us to derive meaning from experience and turn noise into signal.” They are incredibly powerful from an emotional standpoint. That’s why he chose to begin every discussion of a cognitive error with a patient’s case, an anecdote.

CAM knows how effective this can be; that’s why it relies so heavily on anecdotes. When doctors think of a disease, they are likely to think of a memorable patient they treated with that disease, and that patient’s case is likely to bias their thinking about other patients with the same disease. If there is a bad outcome with a treatment, they will remember that and may reject that treatment for the next patient even if it is the most appropriate one. Dr. Howard uses patient stories to great advantage, first providing the bare facts of the case and then letting the patient’s doctors explain their thought processes so we can understand exactly where and why they went wrong. Then he goes on to explain the psychology behind the cognitive error, with study findings, other examples, and plentiful references. If readers remember these cases, they might avoid similar mishaps.

An encyclopedia of cognitive errors

The book is encyclopedic, running to 30 chapters and 588 pages. I can’t think of anything he failed to mention, and whenever an example or a quotation occurred to me, he had thought of it first and included it in the text. I couldn’t begin to list all the cognitive errors he covers, but they fall roughly into these six categories:

- Errors of overattachment to a particular diagnosis

- Errors due to failure to consider alternative diagnoses.

- Errors due to inheriting someone else’s thinking.

- Errors in prevalence perception or estimation.

- Errors involving patient characteristics or presentation context.

- Errors associated with physician affect, personality, or decision style.

A smattering of examples

There is so much information and wisdom in this book! I’ll try to whet your appetite with a few excerpts that particularly struck me.

- Discussing an issue with others who disagree can help us avoid confirmation bias and groupthink.

- Negative panic: when a group of people witness an emergency and fail to respond, thinking someone else will.

- Reactance bias: doctors who object to conventional practices and want to feel independent may reject science and embrace pseudoscience.

- Cyberchondria: using the Internet to interpret mundane symptoms as dire diagnoses.

- Motivated reasoning: People who “know” they have chronic Lyme disease will fail to believe 10 negative Lyme tests in a row and then believe the 11 th test if it is positive.

- The backfire effect: “encountering contradictory information can have the paradoxical effect of strengthening our initial belief rather than causing us to question it.”

- Biases are easy to see in others but nearly impossible to detect in oneself.

- Checklists for fake diseases take advantage of the Forer effect . As with horoscopes and cold readings, vague, nonspecific statements convince people that a specific truth about them is being revealed. Fake diseases are unfalsifiable: there is no way to rule them out.

- When presenting risk/benefit data to patients, don’t present risk data first; it will act as an “anchor” to make them fixate on risk.

- The doctor’s opinion of the patient will affect the quality of care.

- Randomness is difficult to grasp. The hot hand and the gambler’s fallacy can both fool doctors. If the last two patients had disease X and this patient has similar symptoms, the doctor will think he probably has disease X too. Or if the doctor has just seen two cases of a rare disease, it will seem unlikely that the next patient with similar symptoms will have it too.

- Apophenia : the tendency to perceive meaningful patterns with random information, like seeing the face on Mars.

- Information bias: doctors tend to think the more information, the better. But tests are indicated only if they will help establish a diagnosis or alter management. They should not be ordered out of curiosity or to make the clinician feel better. Sometimes doctors don’t know what to do with the information from a test. This should be a lesson for doctors who practice so-called functional medicine : they order all kinds of nonstandard tests whose questionable results give no evidence-based guidance for treating the patient. Doctors should ask “How will this test alter my management?” and if they can’t answer, they shouldn’t order the test.

- Once a treatment is started, it can be exceedingly difficult to stop. A study showed that 58% of medications could be stopped in elderly patients and only 2% had to be re-started.

- Doctors feel obligated to “do something” for the patient, but sometimes the best course is to do nothing. “Just don’t do something, stand there.” At the end of their own life, 90% of doctors would refuse the treatments they routinely give to patients with terminal illnesses.

- Incidentalomas: when a test reveals an unsuspected finding, it’s important to remember that abnormality doesn’t necessarily mean pathology or require treatment.

- Fear of possible unknown long-term consequences may lead doctors to reject a treatment, but that should be weighed carefully against the well-known consequences of the disease itself.

- It’s good for doctors to inform patients and let them participate in decisions, but too much information can overwhelm patients. He gives the example of a patient with multiple sclerosis whose doctor describes the effectiveness and risks of 8 injectables, 3 pills, and 4 infusions. The patient can’t choose; she misses the follow-up appointment and returns a year later with visual loss that might have been prevented.

- Most patients don’t benefit from drugs; the NNT tells us the Number of patients who will Need to be Treated for one person to benefit.

- Overconfidence bias: in the Dunning-Kruger effect, people think they know more than the experts about things like climate change, vaccines and evolution. Yet somehow these same people never question that experts know how to predict eclipses.

- Patient satisfaction does not measure effectiveness of treatment. A study showed that the most satisfied patients were 12% more likely to be admitted to the hospital, had 9% higher prescription costs, and were 26% more likely to die.

- The availability heuristic and the frequency illusion: “Clinicians should be aware that their experience is distorted by recent or memorable [cases], the experiences of their colleagues, and the news.” He repeats Mark Crislip’s aphorism that the three most dangerous words in medicine are “in my experience”.

- Illusory truth: people are likely to believe a statement simply because they have heard it many times.

- What makes an effective screening test? He covers concepts like lead time bias, length bias, and selection bias. Screening tests may do more harm than good. The PSA test is hardly better than a coin toss.

- Blind spot bias: Everyone has blind spots; we recognize them in others but can’t see our own. Most doctors believe they won’t be influenced by gifts from drug companies, but they believe others are unconsciously biased by such gifts. Books like this can make things worse: they give us false confidence. “Being inclined to think that you can avoid a bias because you [are] aware of it is a bias in itself.”

- He quotes from Contrived Platitudes: “Everything happens for a reason except when it doesn’t. But even then you can in hindsight fabricate a reason that will satisfy your belief system.” This is the essence of what CAM does, especially the versions that attribute all diseases to a single cause.

Some juicy quotes

Knowledge of bias should contribute to your humility, not your confidence.

Only by studying treatments in large, randomized, blinded, controlled trials can the efficacy of a treatment truly be measured.

When beliefs are based in emotion, facts alone stand little chance.

CAM , when not outright fraudulent, is nothing more than the triumph of cognitive biases over rationality and science.

Reason evolved primarily to win arguments, not to solve problems.

He includes a thorough discussion of the pros and cons of limiting doctors’ work hours, with factors most people have never considered, and a thorough discussion of financial motivations.

The book is profusely illustrated with pictures, diagrams, posters, and images from the Internet like “The Red Flags of Quackery” from sci-ence.org. Many famous quotations are presented with pictures of the person quoted, like Christopher Hitchens and his “What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence”.

He never goes beyond the evidence. Rather than just giving study results, he tells the reader when other researchers have failed to replicate the findings.

We rely on scientific evidence, but researchers are not immune from bias. He describes the many ways research can go astray: 235 biases have been identified that can lead to erroneous results. As Ioannidis said, most published research findings are wrong. But all is not lost: people who understand statistics and the methodologies of science can usually distinguish a good study from a bad one.

He tells the infamous N-ray story. He covers the file drawer effect, publication bias, conflicts of interest, predatory journals, ghostwriting, citation plagiarism, retractions, measuring poor surrogates instead of meaningful clinical outcomes, and outright fraud. Andrew Wakefield features prominently. Dr. Howard’s discussions of p-hacking, multiple variables, random chance, and effect size are particularly valuable. HARKing is Hypothesizing After the Results are Known. It can be exploited to create erroneous results.

He tells a funny story that was new to me. Two scientists wrote a paper consisting entirely of the repeated sentence “Get me off your fucking mailing list” complete with diagrams of that sentence. It was rated as excellent and was accepted for publication!

Conclusion: Well worth reading for doctors and for everyone else

As the book explains, “The brain is a self-affirming spin-doctor with a bottomless bag of tricks…” Our brains are “pattern-seeking machines that fill in the gaps in our perception and knowledge consistent with our expectations, beliefs, and wishes”. This book is a textbook explaining our cognitive errors. Its theme is medicine but the same errors occur everywhere. We all need to understand our psychological foibles in order to think clearly about every aspect of our lives and to make the best decisions. Every doctor would benefit from reading this book, and I wish it could be required reading in medical schools. I wish everyone who considers trying CAM would read it first. I wish patients would ask doctors to explain why they ordered a test.

The book is not inexpensive. The price on Amazon is $56.99 for both softcover and Kindle versions. But it might be a good investment: you might save much more money that that by applying the principles it teaches, and critical thinking skills might even save your life. Well-written, important, timely, easy, and entertaining to read, lots of illustrations, packed with good stuff. Highly recommended.

View all posts

- Posted in: Book & movie reviews , Critical Thinking , Neuroscience/Mental Health , Science and Medicine

- Tagged in: bias , CAM , cognitive errors , diagnostic mistakes , Jonathan Howard

Posted by Harriet Hall

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Critical thinking: what it is and why it counts. 2020. https://tinyurl.com/ybz73bnx (accessed 27 April 2021)

Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Curriculum for training for advanced critical care practitioners: syllabus (part III). version 1.1. 2018. https://www.ficm.ac.uk/accps/curriculum (accessed 27 April 2021)

Guerrero AP. Mechanistic case diagramming: a tool for problem-based learning. Acad Med.. 2001; 76:(4)385-9 https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00020

Harasym PH, Tsai TC, Hemmati P. Current trends in developing medical students' critical thinking abilities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci.. 2008; 24:(7)341-55 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70131-1

Hayes MM, Chatterjee S, Schwartzstein RM. Critical thinking in critical care: five strategies to improve teaching and learning in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc.. 2017; 14:(4)569-575 https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1009AS

Health Education England. Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England. 2017. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/multi-professionalframeworkforadvancedclinicalpracticeinengland.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England, NHS England/NHS Improvement, Skills for Health. Core capabilities framework for advanced clinical practice (nurses) working in general practice/primary care in England. 2020. https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/images/services/cstf/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England. Advanced practice mental health curriculum and capabilities framework. 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/AP-MH%20Curriculum%20and%20Capabilities%20Framework%201.2.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Jacob E, Duffield C, Jacob D. A protocol for the development of a critical thinking assessment tool for nurses using a Delphi technique. J Adv Nurs.. 2017; 73:(8)1982-1988 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13306

Kohn MA. Understanding evidence-based diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl).. 2014; 1:(1)39-42 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0003

Clinical reasoning—a guide to improving teaching and practice. 2012. https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/201201/45593

McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 4th edn. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2018

Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med.. 2017; 92:(1)23-30 https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

Papp KK, Huang GC, Lauzon Clabo LM Milestones of critical thinking: a developmental model for medicine and nursing. Acad Med.. 2014; 89:(5)715-20 https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000220

Rencic J, Lambert WT, Schuwirth L., Durning SJ. Clinical reasoning performance assessment: using situated cognition theory as a conceptual framework. Diagnosis.. 2020; 7:(3)177-179 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0051

Examining critical thinking skills in family medicine residents. 2016. https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol48Issue2/Ross121

Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Emergency care advanced clinical practitioner—curriculum and assessment, adult and paediatric. version 2.0. 2019. https://tinyurl.com/eps3p37r (accessed 27 April 2021)

Young ME, Thomas A, Lubarsky S. Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ.. 2020; 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02012-9

Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Sadie Diamond-Fox

Senior Lecturer in Advanced Critical Care Practice, Northumbria University, Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Co-Lead, Advanced Critical/Clinical Care Practitioners Academic Network (ACCPAN)

View articles

Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now a regular feature in healthcare practice. This article explores some of the key concepts and terminology that have evolved over the last four decades and have led to our modern day understanding of this topic. It also considers how clinical reasoning is vital for improving evidence-based diagnosis and subsequent effective care planning. A comprehensive guide to applying diagnostic reasoning on a body systems basis will be explored later in this series.

The Multi-professional Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice highlights clinical reasoning as one of the core clinical capabilities for advanced clinical practice in England ( Health Education England (HEE), 2017 ). This is also identified in other specialist core capability frameworks and training syllabuses for advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) roles ( Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, 2018 ; Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2019 ; HEE, 2020 ; HEE et al, 2020 ).

Rencic et al (2020) defined clinical reasoning as ‘a complex ability, requiring both declarative and procedural knowledge, such as physical examination and communication skills’. A plethora of literature exists surrounding this topic, with a recent systematic review identifying 625 papers, spanning 47 years, across the health professions ( Young et al, 2020 ). A diverse range of terms are used to refer to clinical reasoning within the healthcare literature ( Table 1 ), which can make defining their influence on their use within the clinical practice and educational arenas somewhat challenging.

The concept of clinical reasoning has changed dramatically over the past four decades. What was once thought to be a process-dependent task is now considered to present a more dynamic state of practice, which is affected by ‘complex, non-linear interactions between the clinician, patient, and the environment’ ( Rencic et al, 2020 ).

Cognitive and meta-cognitive processes

As detailed in the table, multiple themes surrounding the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning have been identified. Central to these processes is the practice of critical thinking. Much like the definition of clinical reasoning, there is also diversity with regard to definitions and conceptualisation of critical thinking in the healthcare setting. Facione (2020) described critical thinking as ‘purposeful reflective judgement’ that consists of six discrete cognitive skills: analysis, inference, interpretation, explanation, synthesis and self–regulation. Ross et al (2016) identified that critical thinking positively correlates with academic success, professionalism, clinical decision-making, wider reasoning and problem-solving capabilities. Jacob et al (2017) also identified that patient outcomes and safety are directly linked to critical thinking skills.

Harasym et al (2008) listed nine discrete cognitive steps that may be applied to the process of critical thinking, which integrates both cognitive and meta-cognitive processes:

- Gather relevant information

- Formulate clearly defined questions and problems

- Evaluate relevant information

- Utilise and interpret abstract ideas effectively

- Infer well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Pilot outcomes against relevant criteria and standards

- Use alternative thought processes if needed

- Consider all assumptions, implications, and practical consequences

- Communicate effectively with others to solve complex problems.

There are a number of widely used strategies to develop critical thinking and evidence-based diagnosis. These include simulated problem-based learning platforms, high-fidelity simulation scenarios, case-based discussion forums, reflective journals as part of continuing professional development (CPD) portfolios and journal clubs.

Dual process theory and cognitive bias in diagnostic reasoning

A lack of understanding of the interrelationship between critical thinking and clinical reasoning can result in cognitive bias, which can in turn lead to diagnostic errors ( Hayes et al, 2017 ). Embedded within our understanding of how diagnostic errors occur is dual process theory—system 1 and system 2 thinking. The characteristics of these are described in Table 2 . Although much of the literature in this area regards dual process theory as a valid representation of clinical reasoning, the exact causes of diagnostic errors remain unclear and require further research ( Norman et al, 2017 ). The most effective way in which to teach critical thinking skills in healthcare education also remains unclear; however, Hayes et al (2017) proposed five strategies, based on well-known educational theory and principles, that they have found to be effective for teaching and learning critical thinking within the ‘high-octane’ and ‘high-stakes’ environment of the intensive care unit ( Table 3 ). This is arguably a setting that does not always present an ideal environment for learning given its fast pace and constant sensory stimulation. However, it may be argued that if a model has proven to be effective in this setting, it could be extrapolated to other busy clinical environments and may even provide a useful aide memoire for self-assessment and reflective practices.

Integrating the clinical reasoning process into the clinical consultation

Linn et al (2012) described the clinical consultation as ‘the practical embodiment of the clinical reasoning process by which data are gathered, considered, challenged and integrated to form a diagnosis that can lead to appropriate management’. The application of the previously mentioned psychological and behavioural science theories is intertwined throughout the clinical consultation via the following discrete processes:

- The clinical history generates an initial hypothesis regarding diagnosis, and said hypothesis is then tested through skilled and specific questioning

- The clinician formulates a primary diagnosis and differential diagnoses in order of likelihood

- Physical examination is carried out, aimed at gathering further data necessary to confirm or refute the hypotheses

- A selection of appropriate investigations, using an evidence-based approach, may be ordered to gather additional data

- The clinician (in partnership with the patient) then implements a targeted and rationalised management plan, based on best-available clinical evidence.

Linn et al (2012) also provided a very useful framework of how the above methods can be applied when teaching consultation with a focus on clinical reasoning (see Table 4 ). This framework may also prove useful to those new to the process of undertaking the clinical consultation process.

Evidence-based diagnosis and diagnostic accuracy

The principles of clinical reasoning are embedded within the practices of formulating an evidence-based diagnosis (EBD). According to Kohn (2014) EBD quantifies the probability of the presence of a disease through the use of diagnostic tests. He described three pertinent questions to consider in this respect:

- ‘How likely is the patient to have a particular disease?’

- ‘How good is this test for the disease in question?’

- ‘Is the test worth performing to guide treatment?’

EBD gives a statistical discriminatory weighting to update the probability of a disease to either support or refute the working and differential diagnoses, which can then determine the appropriate course of further diagnostic testing and treatments.

Diagnostic accuracy refers to how positive or negative findings change the probability of the presence of disease. In order to understand diagnostic accuracy, we must begin to understand the underlying principles and related statistical calculations concerning sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratios.

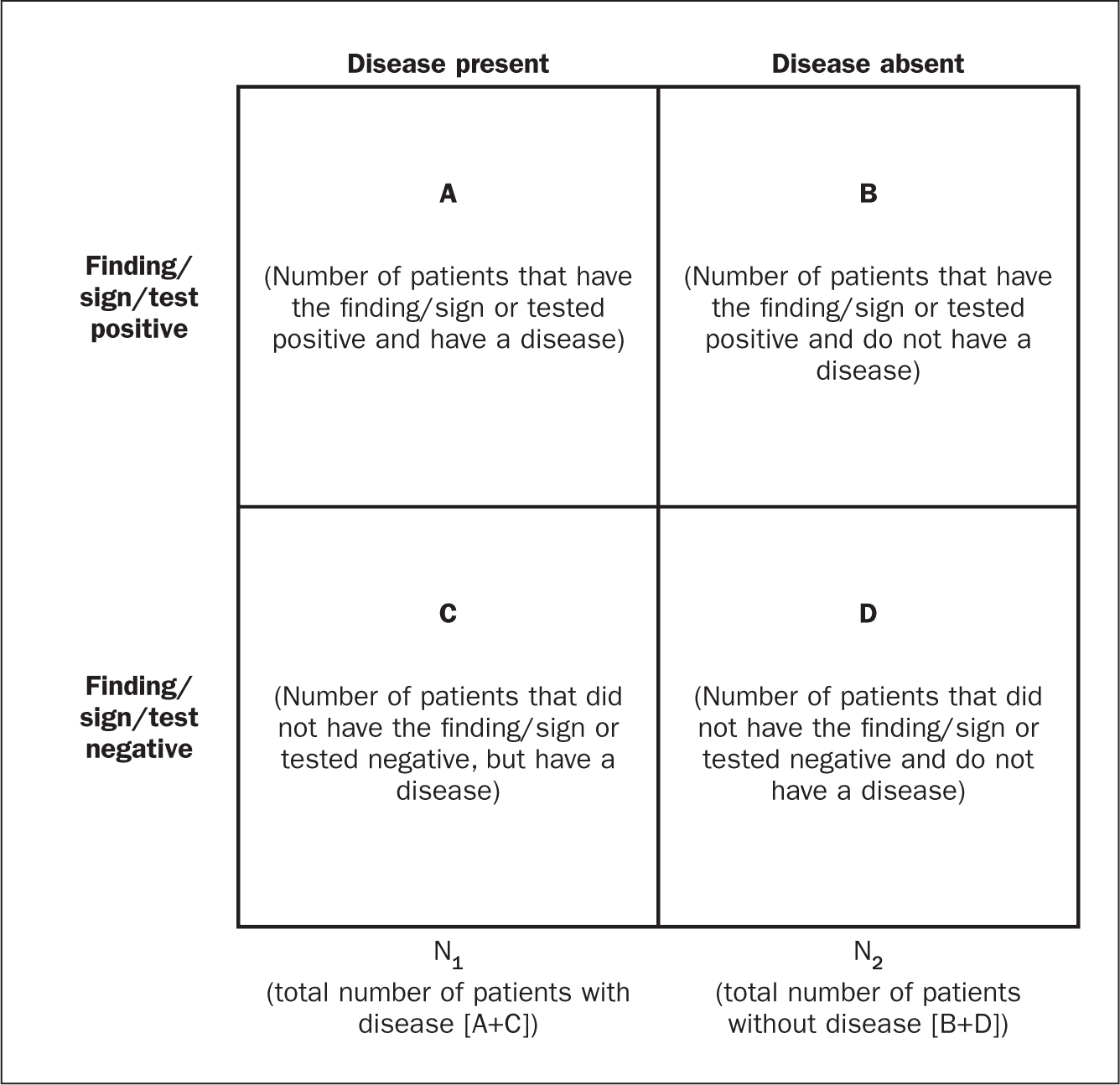

The construction of a two-by-two square (2 x 2) table ( Figure 1 ) allows the calculation of several statistical weightings for pertinent points of the history-taking exercise, a finding/sign on physical examination, or a test result. From this construct we can then determine the aforementioned statistical calculations as follows ( McGee, 2018 ):

- Sensitivity , the proportion of patients with the diagnosis who have the physical sign or a positive test result = A ÷ (A + C)

- Specificity , the proportion of patients without the diagnosis who lack the physical sign or have a negative test result = D ÷ (B + D)

- Positive predictive value , the proportion of patients with disease who have a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease who also have the same sign = A ÷ (A + B)

- Negative predictive value , proportion of patients with disease lacking a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease also lacking the sign = D ÷ (C + D)

- Likelihood ratio , a finding/sign/test results sensitivity divided by the false-positive rate. A test of no value has an LR of 1. Therefore the test would have no impact upon the patient's odds of disease

- Positive likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a positive finding/sign/test, divided by proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (A ÷ N1) ÷ (B÷ N2), or sensitivity ÷ (1 – specificity) The more positive an LR (the further above 1), the more the finding/sign/test result raises a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds of ≥ 4 are often considered to be significant when focusing a clinician's interest on the most pertinent positive findings, clinical signs or tests

- Negative likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a negative finding/sign/test result, divided by the proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (C ÷ N1) ÷ (D÷N1) or (1 – sensitivity) ÷ specificity The more negative an LR (the closer to 0), the more the finding/sign/test result lowers a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds <0.4 are often considered to be significant when focusing clinician's interest on the most pertinent negative findings, clinical signs or tests.

There are various online statistical calculators that can aid in the above calculations, such as the BMJ Best Practice statistical calculators, which may used as a guide (https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/ebm-toolbox/statistics-calculators/).

Clinical scoring systems

Evidence-based literature supports the practice of determining clinical pretest probability of certain diseases prior to proceeding with a diagnostic test. There are numerous validated pretest clinical scoring systems and clinical prediction tools that can be used in this context and accessed via various online platforms such as MDCalc (https://www.mdcalc.com/#all). Such clinical prediction tools include:

- 4Ts score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

- ABCD² score for transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

- CHADS₂ score for atrial fibrillation stroke risk

- Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS).

Conclusions

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role. They are complex processes and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories. There are multiple constructs to guide these processes, not all of which will be suitable for the vast array of specialist areas in which ANMPs practice. There are multiple opportunities throughout the clinical consultation process in which ANMPs can employ the principles of critical thinking and clinical reasoning in order to improve patient outcomes. There are also multiple online toolkits that may be used to guide the ANMP in this complex process.

- Much like consultation and clinical assessment, the process of the application of clinical reasoning was once seen as solely the duty of a doctor, however the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role crosses those traditional boundaries

- Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the ANMP role

- The processes underlying clinical reasoning are complex and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories

- Through the use of the principles underlying critical thinking and clinical reasoning, there is potential to make a significant contribution to diagnostic accuracy, treatment options and overall patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- What assessment instruments exist for the measurement of cognitive bias?

- Think of an example of when cognitive bias may have impacted on your own clinical reasoning and decision making

- What resources exist to aid you in developing into the ‘advanced critical thinker’?

- What resources exist to aid you in understanding the statistical terminology surrounding evidence-based diagnosis?

- Educational advances in emergency medicine

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2020

How to think like an emergency care provider: a conceptual mental model for decision making in emergency care

- Nasser Hammad Al-Azri 1

International Journal of Emergency Medicine volume 13 , Article number: 17 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

14 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

General medicine commonly adopts a strategy based on the analytic approach utilizing the hypothetico-deductive method. Medical emergency care and education have been following similarly the same approach. However, the unique milieu and task complexity in emergency care settings pose a challenge to the analytic approach, particularly when confronted with a critically ill patient who requires immediate action. Despite having discussions in the literature addressing the unique characteristics of medical emergency care settings, there has been hardly any alternative structured mental model proposed to overcome those challenges.

This paper attempts to address a conceptual mental model for emergency care that combines both analytic as well as non-analytic methods in decision making.

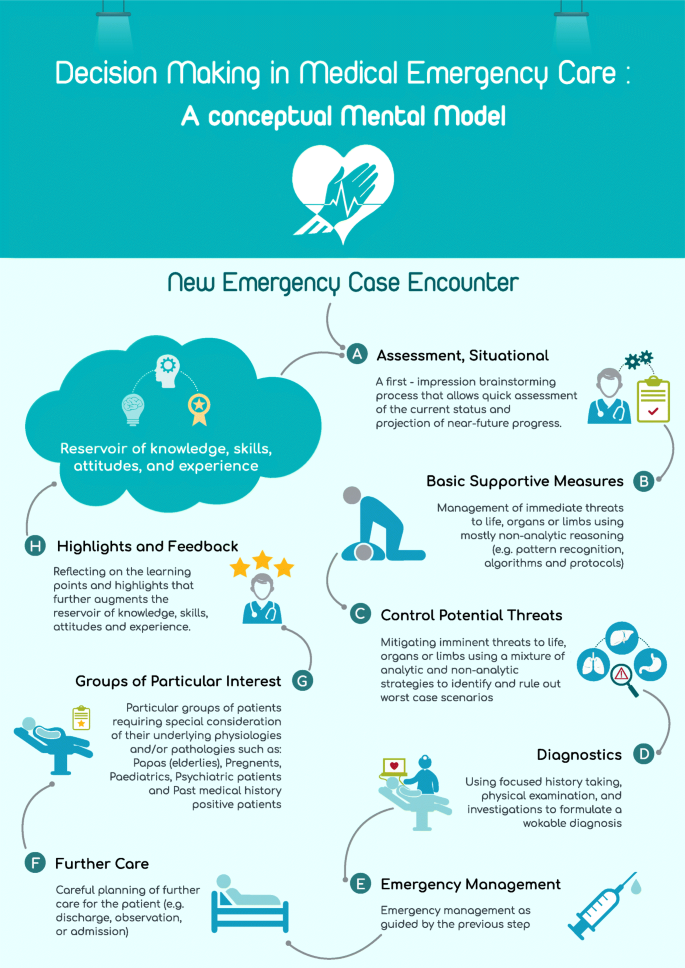

The proposed model is organized in an alphabetical mnemonic, A–H. The proposed model includes eight steps for approaching emergency cases, viz., awareness, basic supportive measures, control of potential threats, diagnostics, emergency care, follow-up, groups of particular interest, and highlights. These steps might be utilized to organize and prioritize the management of emergency patients.

Metacognition is very important to develop practicable mental models in practice. The proposed model is flexible and takes into consideration the dynamicity of emergency cases. It also combines both analytic and non-analytic skills in medical education and practice.

Combining various clinical reasoning provides better opportunity, particularly for trainees and novices, to develop their experience and learn new skills. This mental model could be also of help for seasoned practitioners in their teaching, audits, and review of emergency cases.

“It is one thing to practice medicine in an emergency department; it is quite another to practice emergency medicine. The effective practice of emergency medicine requires an approach, a way of thinking that differs from other medical specialties” [ 1 ]. Yet, common teaching trains future emergency practitioners to “practice medicine in an emergency department.”

Emergency care is a complex activity. Emergency practitioners are like circus performers who have to “spin stacks of plates, one on top of another, of all different shapes and weights” [ 2 ]. This can be further complicated by simultaneous demands from various and multiple stakeholders such as administrators, patients, and colleagues. Add to that the time-bound interventions and parallel tasks required and it can be thought of no less than being chaotic.

There is a tendency to distinguish emergency care from other medical practices as being more action-driven than thought-oriented [ 3 ]. This probably stems from the presumption that emergency medicine follows the same strategy as other medical disciplines so it is judged within the same parameters. Another explanation for this is that emergency practitioners are seen to act immediately on their patients when other medical specialties might take longer time preparing for this action. However, the chaotic environment is different and it requires complex decision-making skills and strategies. Unlike general medical settings, in EM, often a history is unobtainable, and a physical examination and medical investigations are not readily available in a critically ill patient. Despite this, emergency medicine is still being taught using the conceptual model of general medicine that follows an information-gathering approach seeking optimal decision-making. In medical decision-making, the commonly adopted hypothetico-deductive method involving history taking, physical examination, and investigations corresponds to the general approach of medicine.

Importance of rethinking existing medical emergency care mental model

Education in medical emergency care adopts a strategy similar to that of general medicine despite the fact that it is not optimal in emergency departments. Emergency care providers cannot anticipate what condition their patients will be in and they cannot follow the steps of detailed history taking, complete physical examination, ordering required investigations, and, using the results, plan the management of their patient. Classical clinical decision theory may not fit dynamic environments like emergency care. Patients in the emergency department are usually critical, time is limited, and information is scarce or even absent, and decisions are still urgently required.

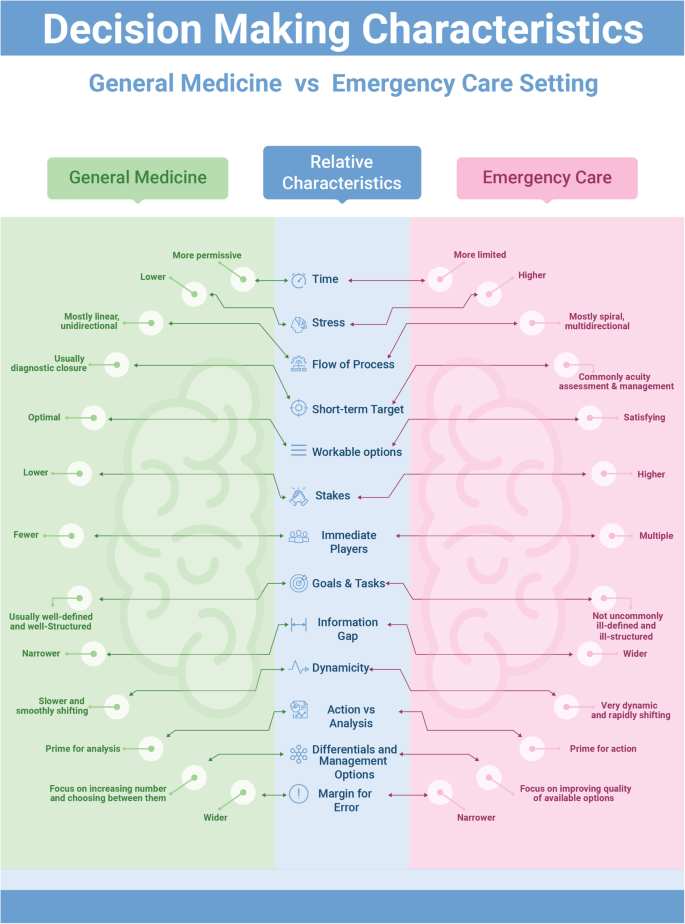

Croskerry (2002) has noted: “In few other workplace settings, and in no other area of medicine, is decision density as high” [ 4 ] as in emergency medicine. In an area where an information gap can be found in one third of emergency department visits, and more so in critical cases [ 5 ], an information-seeking strategy is unlikely to succeed. Moreover, diagnostic closure is usually the short-term target in the hypothetico-deductive method while this is less of a concern in emergency care. Instead, the short-term priorities in emergency care include assessment of acuity and life-saving [ 6 ]. Figure 1 presents a comparison of the conventional general medicine decision-making approach and how emergency care setting differs relatively with regard to those basic characteristics.

Comparing conventional decision-making in general medicine vs. emergency care setting

Hence, a different mental model with a distinctive approach for emergency care is required. Mental models are important to describe, explain, and predict situations [ 7 ]. This is the roadmap through the wilderness of emergency care rather than a guide on driving techniques. Experts are differentiated from novices in several aspects: sorting and categorizing problems, using different reasoning processes, developing mental models, and organizing content knowledge better [ 8 ]. In addition, experienced physicians form more rapid, higher quality working hypotheses and plans of management than novices do. Novices are especially challenged in this area, since teaching general problem solving was replaced with problem-based learning, as the emphasis shifted toward “helping students acquire a functional organization of content with clinically usable schemas” [ 9 ]. The proposed model is intended to better organize the knowledge and approach required in emergency care, which may eventually help improve the practice, particularly of novices.

Clinical decision-making in emergency care requires a unique approach that is sensitive to the distinctive milieu where emergency care takes place [ 10 ]. Xiao et al. (1996) have identified four components of task complexity in emergency medical care [ 11 ]. These include multiple and concurrent tasks, uncertainty, changing plans of management, and compressed work procedures with high workload. Such complex components require an approach that accommodates such factors and balances the various needs in a timely and priority-based, situationally adaptable methodology.

A different model for emergency care

This article addresses a general mental approach involving eight steps arranged with an initialism mnemonic, A–H. Figure 2 presents an infographic of the lifecycle of this A–H decision-making process. These steps represent the lifecycle of decision-making in emergency practice and form the core of the proposed conceptual model. Every emergency care encounter starts with the first step of situational awareness (A) where the provider starts to build up a workable mental template of the case presentation. This process is ongoing throughout the encounter to reflect the dynamic nature of emergency cases. The second to fourth steps (B–D) involve a triaging process in order to prioritize the most appropriate management at that point in time, through a series of risk-stratification stages. Then, additional emergency management (E) follows based on the flow of the case from earlier steps. Following emergency management, a planning step regarding further care (F) for the patient is required. The following step concerns emergency patients who may represent special high risk groups (G) with special precautions and particular diagnostic and management approaches to be considered. This step is, in fact, a mandate throughout the process but included here as a reminder. The final step is a reflection of the entire process that highlights (H) the learning aspects from the case management. Throughout the process, the first and last steps are ongoing as they reflect the dynamicity of the situation.

Situational decision-making model lifecycle

A: (awareness, situational)

It is likely that the first thought of an emergency care provider, when confronted with an acutely ill patient, is the issue of time: “how much time do I have to act and how much time do I have to think?” [ 12 ]. The mental brainstorming that takes place in a matter of seconds is a very valuable and indispensable part of every single emergency encounter. Providers’ prior beliefs, expectations, emotions, knowledge, skills, and experience all contribute to the initial approach adopted. Individuals vary in the importance they attach to different factors [ 13 ], and this variation is reflected in the decisions they make. The importance of this mental process is, unfortunately, not reflected in either general medicine or emergency medicine education and research. Traditionally, “medical education has focused on the content rather than the process of clinical decision making” [ 6 ].

The notion of “situational awareness” (SA) is a useful concept to borrow from aviation sciences. Situational awareness has been defined as the individual’s “perception of the elements of the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning and the projection of their status in the near future” [ 14 ]. As noted from the definition, SA tries to amalgamate the experiences and background of the practitioner with the current situation in order to enable a more educated prediction of what will happen next. Although the concept originated outside of the medical field, it has already been utilized in several medical disciplines including surgery, anesthesiology, as well as quality care, and patient safety [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, SA has been discussed in several emergency care mandates and it is recommended for inclusion in the non-technical skills training of teams in acute medicine [ 15 ].

This emphasizes that an attentiveness to the dynamic nature of priorities in emergency management is as important as knowledge and skills. As such, SA provides a mental model that encourages emergency care practitioners to stay alert for changes in the surrounding environment and relate those changes to case management. The importance of this step in the model is that it prods us to go beyond our immediate perceptions and gut feelings and develop an overall view of the situation [ 18 ]. Practically, decision-making in emergency care has historically depended more on rapid situational assessment rather than optimal decision-making strategies as in the hypothetico-deductive method [ 19 ]. SA is probably one of the most neglected, yet distinguishing, skills in emergency medicine education.

B: (basic life, organ, and limb supportive measures)

The second step in emergency decision-making involves a clinical triaging process. The purpose of this triage is to prioritize time-bound interventions or treatment for the patient. Immediate risks to life, organs, or limbs take priority in case management. This precedes any analytical thinking provided by detailed history taking, physical examination, or investigations, even though a focused approach might be necessary. This step maintains the dynamicity of the process of decision-making and allows the practitioner a holistic view of available and appropriate options rather than ordinary linear thinking. It also provides flexibility of movement between treatment options in response to dynamic changes in the condition.

Life-threatening conditions always take precedence in emergency management. The next priority is to manage immediate risks to body organs or limbs; this is the essence of medical emergency management. Therefore, the aim of this step on basic supportive action (B) is to save the vitals of the patient. This is where advanced cardiac and trauma life support algorithms and emergency management protocols are important.

A useful approach at this step is pattern recognition. In real practice, when confronted with a critically ill or crashing patient, the emergency care provider usually abandons the time-consuming hypothetico-deductive method; pattern recognition offers a rapid assessment and clinical plan that permits immediate life-, organ-, or limb-saving measures to take place [ 20 ]. Pattern recognition, known also as non-analytic reasoning, is a central feature of the expert medical practitioner’s ability to rapidly diagnose and respond appropriately, compared to novices who struggle with linear thinking skills [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. This approach could be further augmented by the availability of algorithms and protocols that allow immediacy of perception and initiation of management [ 4 ], as well as by including it in clinical teaching and education.

C: (control potential life, organ, and limb threats)

While emergency care providers must prioritize immediate threats to life, organs, and limbs, they must also anticipate and recognize imminent threats to the same and control them (C). This is one of the biggest challenges in emergency care compared to other medical settings; oftentimes, the grey cases are the hidden tigers. In fact, seasoned emergency care providers know that even the most unremarkable patients may have a catastrophic outcome within moments [ 24 ]. Emergency care providers usually adopt mental templates for the top diagnoses that they need to exclude for every particular presentation. This is a step of “ruling out” worst diagnoses before proceeding. Croskerry (2002) asserts that this “rule out the worst case” strategy is almost pathognomonic of decision-making in the emergency department [ 4 ]. Many emergency presentations (e.g., poisoning, head injury, and chest pain) are true time bombs that any emergency care provider should be alert to.

This step presents an intermediate stage between the previous step (B) where pattern recognition and non-analytic reasoning dominates decision-making, and the next step (D) where the hypothetico-deductive approach with its analytic reasoning starts to play a major role in decision-making. As such, this step utilizes a mixture of the analytic and non-analytic reasoning to aid emergency care practitioners the “rule out the worst case” scenario in their patients. Examples of presentation-wise “worst case” scenarios are illustrated in Table 1 .

Once a potential threat is discovered, the practitioner will be situationally more aware and this will help to initiate measures that could prevent further deterioration of the condition. Again, this step is another that is practiced commonly by expert practitioners but is presented informally or insufficiently in emergency medicine training or education. Emergency care practitioners should focus more on this step due to its centrality in emergency care practice as well as its importance for ensuring safety of patients.

D: (diagnostics)

Once immediate and/ or imminent threats have either been excluded or managed, the emergency care provider may move on to the next step of formulating a workable clinical diagnosis (D) through the commonly adopted hypothetico-deductive medical model via a focused history taking, physical examination, and investigations. This is basically what all medical students are trained for in their undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. This step involves the utilization of existing tools for optimal decision-making within the available resources in the emergency department. Nevertheless, a final diagnosis may not be reachable in the emergency department setting.

E: (emergency management)