- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2018

Household latrine utilization and its association with educational status of household heads in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Cheru Tesema Leshargie 1 ,

- Animut Alebel 2 ,

- Ayenew Negesse 3 ,

- Getachew Mengistu 4 ,

- Amsalu Taye Wondemagegn 5 ,

- Henok Mulugeta 2 ,

- Bekele Tesfaye 2 ,

- Nakachew Mekonnen Alamirew 1 ,

- Fasil Wagnew 2 ,

- Yihalem Abebe Belay 1 ,

- Aster Ferede 1 ,

- Mezinew Sintayehu 2 ,

- Getnet Dessie 2 ,

- Dube Jara Boneya 1 ,

- Molla Yigzaw Birhanu 1 &

- Getiye Dejenu Kibret 1

BMC Public Health volume 18 , Article number: 901 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

29 Citations

Metrics details

Ethiopia has been experiencing a high prevalence of communicable diseases, which resulted in high morbidity, mortality, and hospital admission rates. One of the highest contributing factors for this is lower level of latrine utilization. There had been significantly varying finding reports with regard to the level of latrine utilization and its association with education level from different pocket studies in the country. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of household latrine utilization and its association with education status of household heads, in Ethiopia using available studies.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted using available data from the international databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Science direct, Cochrane library and unpublished reports. All observational studies reporting the prevalence of latrine utilization in Ethiopia were included. Four authors independently extracted all necessary data using a standardized data extraction format. STATA 13 statistical software was used to analyze the data. The Cochrane Q test statistics and I 2 test were used to assess the heterogeneity between the studies. A random effect model was computed to estimate the pooled level of latrine utilization in Ethiopia. In addition, the association between latrine utilization and the educational level of the users was analyzed.

After reviewing of 1608 studies, 17 studies were finally included in our meta-analysis. The result of 16 studies revealed that the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization level in Ethiopia was 50.02% (95%CI: 40.23, 59.81%). The highest level (67.4%) of latrine utilization was reported from Southern Nations Nationality and People regional state, followed by Amhara regional state (50.1%). Participants who completed their high school and above education were more likely (OR: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.05, 3.05) to utilize latrine compared to those who did not attend formal education.

In Ethiopia, only half of the households utilize latrine and the level of utilization has significant association with educational status.

Peer Review reports

Communicable diseases are serious public health problems, affecting billions of people around the world, mainly the third world countries [ 1 , 2 ]. Latrine utilization, the main determinant for communicable diseases control, is still at its lower level in developing countries including Ethiopia [ 3 ]. Access to safe drinking water and sanitation is a basic necessity that is vital for human health and among the basic human rights declared by the United Nations. Ensuring sanitation demands the availability of facilities and services for the safe disposal of human excreta. It is one of the components of the sustainable development goals that are set to be achieved by 2030 [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ].

Worldwide, a tremendous progress has been made in increasing access to facilities that ensure hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact. More than half of the global population used basic sanitation services and nearly two out of five people (39%) utilized safely managed sanitation services. Nevertheless, billions of people still remained without even the basic sanitation services and around 800 million people used unimproved facilities. Most countries are moving off the track to attain the desired coverage for sanitation set in the sustainable development goals [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

In communities where access to improved sanitation facilities is low, people are forced to engage in unsafe practice of open defecation. This practice continues to be a major challenge and about 2.3 billion people who still lack basic sanitation service either practice open defecation (892 million) or use unimproved facilities such as pit latrines without a slab or platform, hanging latrines or bucket latrines (856 million) [ 11 ]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people who defecate in the open field rose from 204 to 220 million by 2015 [ 8 , 9 , 12 , 13 ]. Diarrheal and other communicable diseases are often linked with poor sanitation and open defecation. Moreover, higher rates of open defecation are also associated with significant socioeconomic, environmental and major public health consequences affecting the overall health and dignity of mankind, the most vulnerable groups being women and children [ 1 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Increasing availability and proper utilization of latrines is essential and a cost-effective strategy to overcome disease burden associated with improper excreta management [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. The use of latrines can be affected by a range of behavioral, cultural, social, geographic and economic factors differing across communities [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ].

According to the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys report, 56% of the rural households use unimproved toilet facilities. One in every three households in the country has no toilet facility [ 30 ]. The inauguration of the health extension program in 2003 and the national water supply, sanitation and hygiene [ 31 ] program contributed much to the improved coverage of latrines across the country. However, achieving real gains in increasing latrine use and quality remained as a challenge [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ].

In Ethiopia, different fragmented and small studies have been conducted to assess the level of latrine utilization. Nevertheless, the findings of these studies reported highly varying figures. Some of the findings showed as the level of latrine utilization is at a good progress, while some others revealed the awkward aspect. The previous studies also indicated the presence of significant variability in latrine utilization from region to region [ 36 , 37 ].

Determining the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization at a country level will provide an overall figure with better estimation accuracy. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed at estimating the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization and its association with education level. The findings from this study will have a paramount importance for decision makers revealing at what level the country is with regard to latrine utilization.

Searching strategies

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization and its association with educational level of the user in Ethiopia. To conduct this study, all potentially relevant articles, grey literatures, and government reports were meticulously searched. The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist guideline was used to ensure the scientific rigor [ 38 ]. We searched articles from international databases including Cochrane library, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Science direct. The reviewers used the following keywords “prevalence”, “(“toilet facilities“[MeSH Terms] OR (“toilet“[All Fields] AND “facilities“[All Fields]) OR “toilet facilities“[All Fields] OR “latrine“[All Fields]) AND (“utilization“[Subheading] OR “utilization”[All Fields]) AND (“ethiopia“[MeSH Terms] OR “ethiopia”[All Fields]) to get published articles from above mentioned databases.

“The search was carried out from September to October, 2017. All articles published until October, 2017 were included in the review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The current meta-analysis and systematic review included studies conducted only in Ethiopia and that reported the level of latrine utilization, articles published in the scientific journals and grey literatures. Studies written in English language and full-text articles only were considered. In addition, the review considered all observational study designs (Cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort) reported the level of latrine utilization in Ethiopia. We excluded articles which were not able to be accessed for full article text after communicating the principal investigator of the primary studies by email at least three times.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of interest was the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization. The prevalence was computed from the proportion in which the number of individuals who had proper latrine utilization to the total number of households with functional latrine multiplied by 100. Estimate of the association between educational status and level of latrine utilization was also a second outcome.

Study setting

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in Ethiopia. The country is located in the Horn of Africa with projected population of 107,421,970 by 2018 year. The country is divided into nine regions and two administrative cities. The regions are Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, Harari, Oromia, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples of Ethiopia, and two city administrates are Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa [ 39 ].

Operational definitions

Improved sanitation facilities ( Latrine) are those designed to hygienically separate excreta from human contact. These include wet sanitation technologies (flush and pour flush toilets connecting to sewers, septic tanks or pit latrines) and dry sanitation technologies (ventilated improved pit latrines; pit latrines with slabs; or composting toilets) [ 11 ].

Latrine utilization – households with either shared or private functional latrines functional latrines and the family disposed the faeces of under-five children in a latrine, no observable faeces in the compound, no observable fresh faeces on the inner side of the squatting hole and the presence of clear foot-path to the latrine is uncovered with grasses or other barriers of walking [ 1 ].

Education categories : The primary studies classified education for the head of the households as 1) not attended formal education, 2) attended primary education (1–8), 3) attended secondary Educations and 4) college and above.

Data abstraction

Four authors (CTL, AA, AF and HM) independently searched the studies, articles, and reports, and extracted all necessary data using a standardized data extraction format using Microsoft Excel. The extracted parameters were: primary author, publication year, region where the study was conducted, the study design used, sample size, level of latrine utilization, and quality of each study. Then, three authors (AT, GDK and NM) checked the data extraction process. Finally, nine authors (AN, BT, FW, DJB, GM, YA, GDK, MYB and MS) participated in resolving the disagreement.

Quality assessment of the studies

We used Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies quality assessment to assess the quality of each study [ 40 ]. The tool has mainly three sections; the first section grades from five stars and mainly focuses on the methodological quality of each study (sample size, response rate and sampling technique). The second section deals with the comparability of the studies, with a possibility of two stars to be gained. The last section deals with the outcomes and statistical analysis of the original study with a possibility of three stars to be gained (Additional file 1 ). Two authors independently assessed the quality of each original study. Disagreements between two authors were resolved by taking the mean score of the two authors. Finally, researches with a scale of ≥6 out of 10 were considered as achieving high quality. This cut-off point was declared after reviewing relevant literatures.

Data analysis

The extracted data were compiled in Microsoft Excel format and analyzed using STATA version 13 statistical software. The binomial distribution formula was used to calculate standard error for each eligible original article. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q- statistics and Higgins’ and Thompson’s I 2 test [ 41 ]. As the preliminary output of the test statistics revealed a significant heterogeneity among studies ( I 2 = 99.5%, p = 0.00), random Effects meta-analysis model was used for approximation of the Der Simonian and Laird’s pooled effect. Subgroup analysis was also performed among regions, study setting and education in relation to the latrine utilization as well as trends of latrine utilization was made. To reduce the random variations between the individual point estimates of the primary study, a subgroup analysis was carried out based on study settings (regions). Possible source of heterogeneity was also identified by Univariate Meta-regression by taking the sample size and year of publication as covariates. Furthermore, Egger and Begg tests at 5% significant level were employed to assess publication bias [ 42 ]. The point prevalence with its corresponding 95% confidence interval was presented using forest plot. In this forest plot, the size of each individual box revealed the weight of the study, while each crossed line refers to 95% confidence interval. We conducted log-odd ratio for the second outcome (the relationship between latrine utilization and educational status of the households.

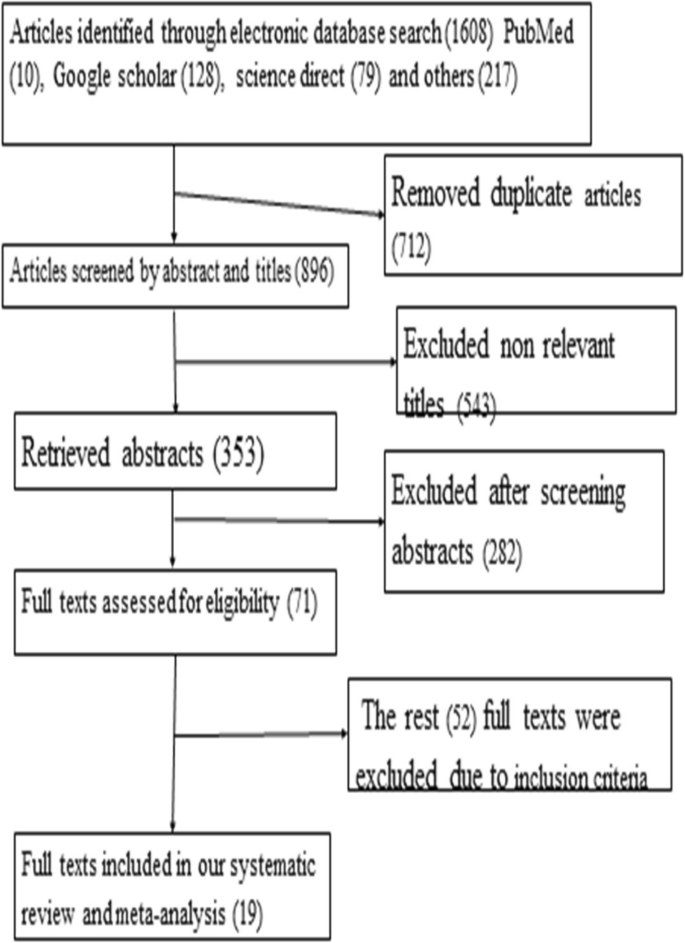

One thousand six hundred eight (1608) primary studies that addressed latrine utilization and associated factors were searched using both through PubMed, Google Scholar, science direct and grey as well as the government reports. Seven hundred twelve (42.3%) of these identified articles were excluded because of similarity and duplicated articles. Among the remaining 896articles, 543 articles were excluded after reviewing their titles for a reason of relevance for our objective. The rest 353 articles were screened for abstracts and 286 were excluded after reading their abstract sections. Therefore, 71 full-text articles were accessed and assessed for eligibility based on the pre-set criteria, and from these 52 were excluded for not fitting the inclusion criteria. Finally, 19 studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria and included in the final meta-analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow chart to describe the selection of studies for a systematic review and meta-analysis of the level of latrine utilization and is association with educational status at Ethiopia

Overview of included studies

These 19 (of which 2 were unpublished) studies were published from 1999 to 2017. In the current meta-analysis, 966,362 study participants were involved to estimate the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization in Ethiopia in which the lowest (30.99%) latrine utilization was observed from a study conducted at Akaki, Oromia region [ 43 ] while the highest prevalence (99.4%) was reported from a study conducted in Dembia district of Amhara region [ 44 ]. Regarding the study design, all (100%) of the studies were cross-sectional study designs. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 355 to 955,985. This meta-analysis and systematic review used data taken from primary studies of five (5) (Amhara, south nation and nationality people of Ethiopia, Oromia, Tigray and Harari) regions of Ethiopia that shares eight (42%), 4 (21%), 4 (21%), 2 (1%) and 1 (0.5%) respectively (see the Additional file 2 ).

- Meta-analysis

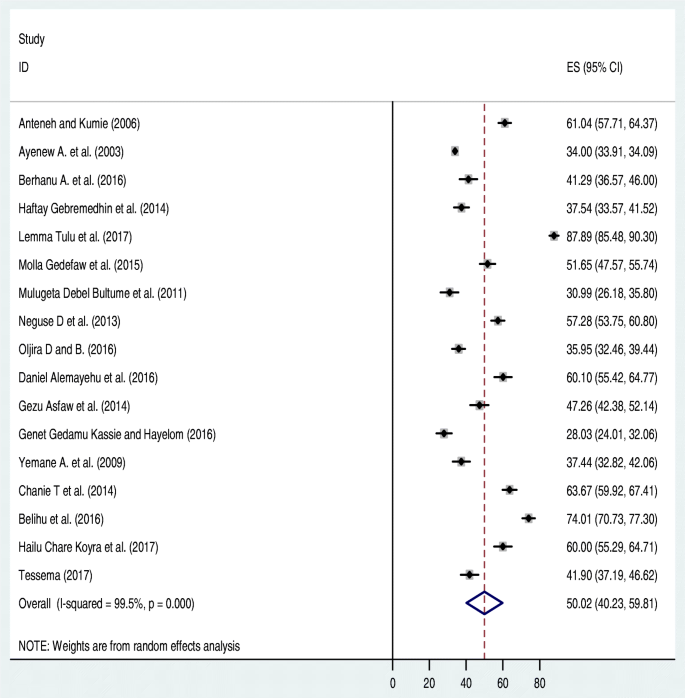

As indicated above in the Additional file 2 , 19 studies were found to be eligible for the analysis. Of these, two studies [ 44 , 45 ] were excluded from forest plot of the pooled level of latrine utilization after we did sensitiy analysis. The sensitivity analysis for Amhara, Tigray, SNNP and others (Oromia and Harar) regions were revealed as (I 2 = 98.3, p value = 0.001), (I 2 = 98.9, p value = 0.001), (I 2 = 62.7, p value = 0.001) respectively. Seventeen articles were considered to determine the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization in Ethiopia that found to be 50.2% (95% CI: 40.23, 59.81%). High heterogeneity, (I 2 = 99.5, p value < 0.001), was observed between 17 primary studies included in this review. As a result, to reduce it, we performed a subgroup analysis (I 2 = 99.5, p value = 0.001) and come up a slight improvement. The regional subgroup analysis revealed that significant regional variation regarding latrine utilization was observed across the country. Southern nation nationalities and people of Ethiopian have better latrine utilization while Oromia utilizes least. As a result, a random effect model was employed to estimate the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization in Ethiopia.

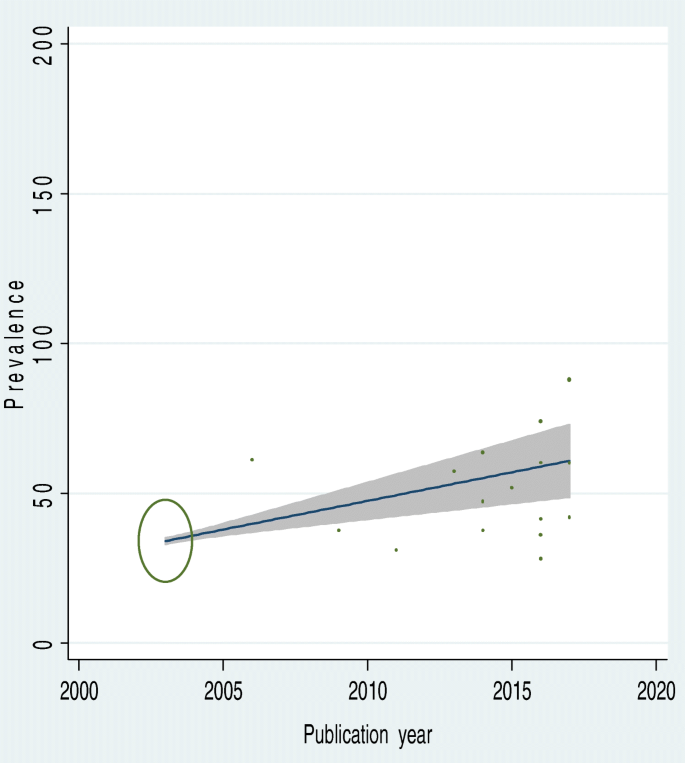

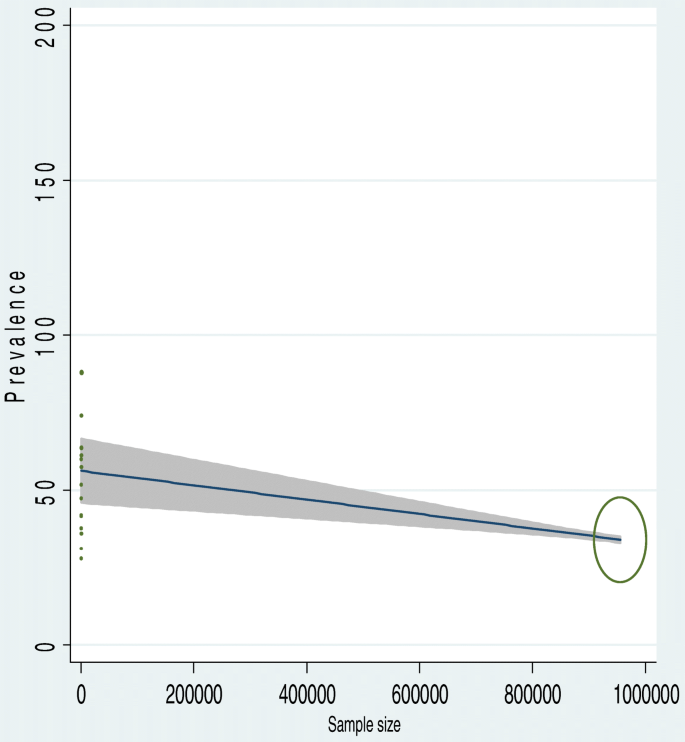

To identify the possible source of heterogeneity, different factors associated with the heterogeneity such as publication year and sample size of the study were investigated by using Univariate meta-regression models, but none of these variables were found to be statistically significant. Even though it is not statistically significant for the increments of both sample size and publication year, as sample size, increase the level of latrine utilization was showed slightly decreased, whereas the proportion showed level of latrine utilization increments as publication years does also (Table 1 ). Moreover, Publication bias was also assessed using Begg and Egger tests. The result of Begg and Egger tests were not statistically significant for estimating the level of latrine utilization ( p = 0.15) and ( p = 0.3) respectively (Figs. 2 , 3 , 4 ).

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization in Ethiopia

The Univariate Meta regression to identify possible source of heterogeneity by publication year

The Univariate Meta regression to identify possible source of heterogeneity by sample size

Subgroup analysis

In order to appreciate the heterogeneity of individual studies, subgroup analysis was conducted based on the region where the studies were conducted. The output of subgroup analysis revealed that, the highest latrine utilization was observed in south nation and nationalities and peoples of Ethiopia with a prevalence of 67.4% (95% CI: 50.3, 84.5) followed by Amhara with pooled latrine utilization of 50.1% (95% CI: 39.7, 62.2). Besides, subgroup analysis based on the sample size (≥500 and<500) of studies revealed that subgroup of sample size ≥500, 55.9% (95% CI: 40.0, 71.8%) revealed a higher latrine utilization than the subgroup of sample size < 500, 43.4% (95% CI: 34.9, 59.8%) (Table 2 ).

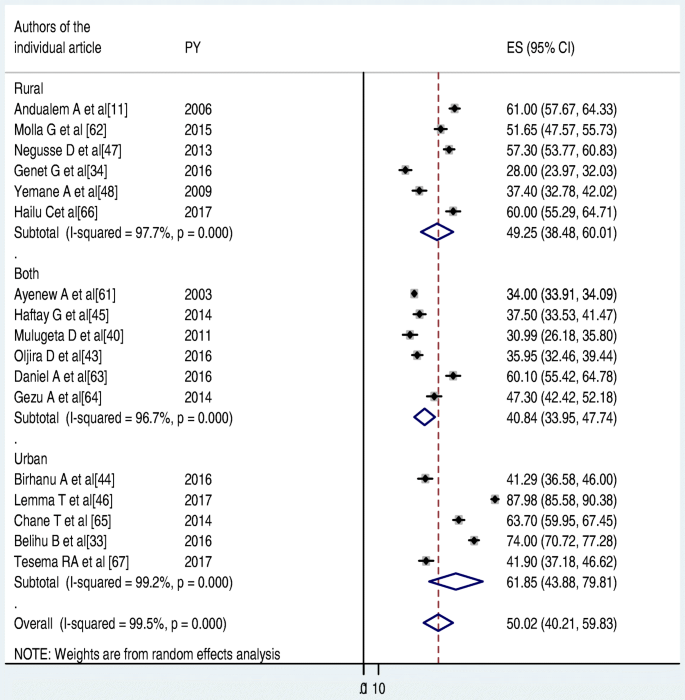

Similarly, subgroup analysis was also performed between study settings (urban, rural and both). The pooled latrine utilization for study settings that means rural, both and urban were found to be 49.25(38.48, 60.01), 40.84(33.95, 47.74) and 61.85(43.88, 79.81) respectively (Fig. 5 ).

The subgroup analysis of latrine utilization status by study settings (rural, both urban and rural, and urban) in Ethiopia

The association between latrine utilization and educational status

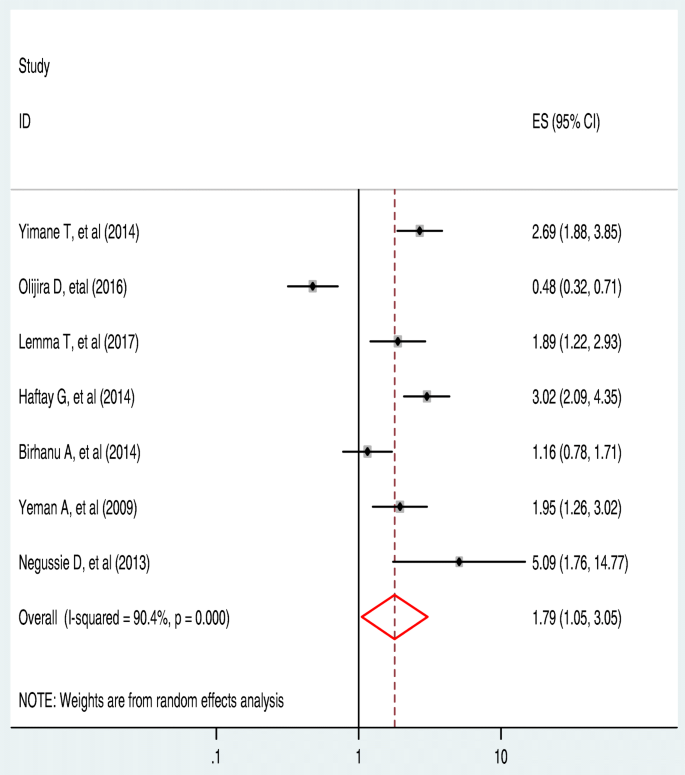

A total of 7(41.2%) studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and which were considered for determining the pooled level of latrine utilization assessed the association between education and latrine utilization practice. Only one (14.3%) of the studies estimated that education has a negative association with latrine utilization. That is, respondents who are literate are less likely to utilize latrine compared with the illiterate respondents [ 46 ].

The remaining 6(85.7%) of the studies reported that [ 44 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ] as people get education they use a latrine (Positive association). The heterogeneity (I 2 = 90.4% and P -value < 0.001) became lower during this subgroup analysis when compared with the pooled latrine use analysis result. However, lower heterogeneity (compared with the pooled results of all 17 studies) was observed during subgroup analysis, a random effect meta-analysis model was employed to determine the association between latrine utilization and educational status of the respondents. The overall effect of educational status (as indicated in this subgroup analysis) showed that individual educational status was significantly associated with latrine utilization (OR: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.05, 3.05) (Fig. 6 ).

The pooled odds ratio of the association between latrine utilization and educational status in Ethiopia

This systematic review and meta-analysis disclosed that the pooled level of latrine utilization in Ethiopia was 50.0% (95% CI: 40.23, 59.81%). This finding is lower than a study conducted in Ghana which revealed that 66.5% of the community had proper latrine utilization [ 52 ]. Similarly, the finding of this meta-analysis is slightly lower that a study conducted in Sub-Saharan African countries revealed that proper latrine utilization was estimated to be 63%). Likewise, the finding is much lower than a community-based study conducted in Nepal (94.3%) [ 53 ]. The possible explanation for the above-observed discrepancy between the current meta-analysis and comparable findings might be due to the difference in the Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. A report from other sub-Saharan African countries contained a data mostly collected from the urban population while in this study; both urban and rural settings were considered. The other possible explanation for the above variation could be due to the difference in study design.

However, the current pooled analysis of latrine utilization is higher than a the world health organization report (39%) [ 10 ]. Similarly, the current pooled latrine utilization result is slightly higher than from southern Asia countries reported by the world health organization [ 54 ] and Indian where only 47% of the respondents use latrine always [ 55 ]. The observed discrepancy could be resulted from time, study setting, sample size and socioeconomic difference among the different settings. The additional possible justification for the discrepancy might be because of half the population of in developing world lacks basic sanitation [ 56 ]. In addition, in Ethiopia, the government has been implementing different interventions to improve the level of latrine utilization (basic sanitation) for example, the implementation of health extension package since 2003. The health policy (focused on prevention of diseases and promotion of health using the provision of basic sanitation in all level of the country) of Ethiopia could be also another determinant factor for the slight improvement of the latrine utilization level in the country [ 57 ].

The pooled prevalence of latrine utilization level in Southern Nation and nationalities and People region of Ethiopia (SNNRPE) was 67.4% which is higher than the pooled prevalence of latrine utilization level than other regions of the country Ethiopia; in Amhara 50.1%, in Tigray 41.5% and others 36.3%. The possible explanations for this variation might be due to the difference in socioeconomic and sociocultural difference between the regions. The other possible explanation for this variation might be due to differences in the study period in which data collection period for all studies taken from the SNNRPE is recent than the others. On top of the above possible justification, almost half of the studies conducted at south nation nationality and people of Ethiopia were conducted in urban set-up including the capital city of the region. In addition, from this subgroup analysis, it was observed that the estimated latrine utilization level in the SNNRPE was 64.7%, which is higher than the estimated report on latrine utilization by the Min Ethiopian demographic health survey 2014 which was 54% [ 58 ] of the community use latrine. The subgroup analysis also revealed that latrine utilization was better in Amhara region next to the SNNRPE followed by Tigray. This finding was directly related with the educational development of the regions. Currently, the quality of education reported better at Tigray, Amhara region, Oromia and SNNPE, while bringing quality education on the rest regions are still challenging due to their living style. People living other than these detailed above lives a nomadic and pastoral life.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we performed a subgroup analysis by study settings (urban, both setting and rural). However, the finding was not statistically significant despite a slight discrepancy. Latrine utilization was found to be better in the urban setting (61.85%) as compared to rural (49.25%) and both (40.84%). Better latrine utilizations in urban setting might be due to high literate populations reside urban than the counterpart settings.

Educational level of the respondents has a significant association with latrine utilization. The finding of this study is supported by other similar study conducted on the impact of sanitation intervention on latrine coverage and uses a worldwide report that means education level has an effect on the community latrine utilization [ 59 ]. This might be due to that education has a significant influence on human behavior towards behaving health activities. Similarly as peoples’ educational status increases, their knowledge on the diseases causation, transmission and the role of human waste to the occurrence of communicable diseases increases. Therefore, to keep their health well they manage and dispose of every type of wastes (including human excreta) safely wherein properly constructed latrine. On the contrary to this study, educational status of the respondents (head of the household) has no any significant association with latrine utilization in one study conducted in Nepal [ 60 ]. This might be due to the fact that even though slightly more than half of the participates were illiterate (51.7%), the government of Nepal is committed to improving sanitation throughout the country, one priority campaign is improving latrine coverage towards attaining open defecation free areas all over the country by 2017 [ 17 ]. Despite the fact that a lot activities and strategies(like training manpower, ONE WASH, Health Extension Package and Community Lead Total Sanitation and Hygiene Behavioral Change) have been conducted in the country Ethiopia, latrine utilization was remain on half of the country vision which was 100% basic sanitation (including proper latrine utilization) [ 61 ].

Education and creating awareness is one among the 16 packages included in the health extension packages. Health extension workers employed to implement this packages provide a routine health education to improve the community awareness to increase latrine utilizations [ 62 ]. This implies that as the educational level of individual increased latrine utilization will increase.

Limitations of the study

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we recognized some limitations. The first concern was the use of only English language articles as inclusion criteria. The other constraint is the cross sectional nature of the included articles, which can affect the second objective due to the presence of confounders. In addition, the pooled prevalence might not represent the whole country as the included articles were only from six administrative regions.

Only half of the community has had latrine utilization practice and which is lower compared with the country target 100% set to be met by 2015. This meta-analysis also showed that educational status of the community has a significant association with latrine utilization; that is, attending formal education is a positive predictor for community latrine utilization.

Abbreviations

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

Millennium Development Goals

Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Southern Nation and Nationalities People region of Ethiopia

Water Sanitation and hygiene

Anteneh A, Kumie A. Assessment of the impact of latrine utilization on diarrhoeal diseases in the rural community of Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara region. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24(2)

Ammar FJH: Identifying and supporting the most disadvantaged people in CLTS: a case study of Bangladesh .. 2010.

Google Scholar

Ethiopia briefing: Economic impact of water and sanitation - unicef, Sanitation and Water for all. 2011.

Wateraid sf, [cited on oct 09 2017]; Available form: www.wateraid.org/publications .

Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(5):275–81.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Demeke A, Abebe A, Wale A, Kaba E, Sime E, Addis H, Admassu S, Steenhuis T. Sanitation promotion and household latrine, November 2011. (accessible at website: https://wateraidethiopia.org )

Assembly UG: The human right to water and sanitation UN resolution 2010, 64:292 2010.

Organization WH. Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment: World Health Organization; 2015.

Organization WH, UNICEF: progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and SDG baselines. 2017.

Supply WUJW, Programme SM. Progress on drinking water and sanitation: 2014 update: World Health Organization; 2014.

Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; 2017.

Galan DI, Kim S-S, Graham JP. Exploring changes in open defecation prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa based on national level indices. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):527.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

UNICEF: Water,sanitation and hygiene, annual results report 2016; [cited 9th oct 2017], available form: https://www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/2016arr_wash.pdf . 2016.

Bartram J, Cairncross S. Hygiene, sanitation, and water: forgotten foundations of health. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000367.

Eshete N, Beyene A, Terefe G. Implementation of community-led Total sanitation and hygiene approach on the prevention of diarrheal disease in Kersa District, Jimma Zone Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2015;3(5):669–76.

Article Google Scholar

Karn SK, Harada H. Field survey on water supply, sanitation and associated health impacts in urban poor communities-a case from Mumbai City, India. Water Sci Technol. 2002;46(11–12):269–75.

Mara D, Lane J, Scott B, Trouba D. Sanitation and health. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000363.

Prüss-Ustün A, Bartram J, Clasen T, Colford JM, Cumming O, Curtis V, Bonjour S, Dangour AD, De France J, Fewtrell L. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low-and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Tropical Med Int Health. 2014;19(8):894–905.

Ziegelbauer K, Speich B, Mäusezahl D, Bos R, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Effect of sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(1):e1001162.

Clasen TF, Bostoen K, Schmidt WP, Boisson S, Fung ICH, Jenkins MW, Scott B, Sugden S, Cairncross S. Interventions to improve disposal of human excreta for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Libr. 2010;

Hulton G, Organization WH: Global costs and benefits of drinking-water supply and sanitation interventions to reach the MDG target and universal coverage. 2012.

Hutton G, Haller L, Water S, Organization WH: Evaluation of the costs and benefits of water and sanitation improvements at the global level. 2004.

Gebremedhin. Latrine utilization and associated factors in south east zone of tigray region, north ethiopia. Eur J Biomed Pharmac Sci. 2016;3(6):120–6.

CAS Google Scholar

Asfaw G, Molla E, Vata PK. Assessing privy (Latrine’s) utilization and associated factors among households in Dilla town, Ethiopia. Int J Health Sci Res. 2015;5(6):537–44.

Budhathoki SS, Shrestha G, Bhattachan M, Singh SB, Jha N, Pokharel PK. Latrine coverage and its utilisation in a rural village of eastern Nepal: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):209.

Debesay N, Ingale L, Gebresilassie A, Assefa H, Yemane D. Latrine Utilization and Associated Factors in the Rural Communities of Gulomekada District, Tigray Region, North Ethiopia, 2013: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Community Med Health Educ. 5:338.

Gedefaw M, Amsalu Y, Tarekegn M, Awoke W. Opportunities, and challenges of latrine utilization among rural communities of Awabel District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014. Open J Epidemiol. 2015;5(02):98.

Koyra HC, Sorato MM, Unasho YS, Kanche ZZ. Latrine utilization and associated factors in rural Community of Chencha District, southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Amer J Public Health Res. 2017;5(4):98–104.

Yimam YT, Gelaye KA, Chercos DH. Latrine utilization and associated factors among people living in rural areas of Denbia district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2013, a cross-sectional study. Pan Afric Med J. 2014;18

Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016 report.

UNICEF W, sanitation and hygiene, annual results report 2016; [cited 9th oct 2017], available form: https://www.unicef.org/publicpartnerships/files/2016arr_wash.pdf .

Gebru T, Taha M, Kassahun W. Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease in under-five children among health extension model and non-model families in Sheko district rural community, Southwest Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):395.

King JD, Endeshaw T, Escher E, Alemtaye G, Melaku S, Gelaye W, Worku A, Adugna M, Melak B, Teferi T. Intestinal parasite prevalence in an area of Ethiopia after implementing the SAFE strategy, enhanced outreach services, and health extension program. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(6):e2223.

Tibebu T: Evaluation The Impact Of World Vision Ethiopia, Water, Sanitation And Hygiene Project On The Community: The Case Of Amhara Region, West Gojam Zone, Jabi Tehnane Woreda. St. Mary's University; 2016.

Workie NW, Ramana GN: The health extension program in Ethiopia. 2013.

Belihu B, S Mohammed, W Godana: Latrine utilization and associated factors among households in Melo Koza District, Southern Ethiopia: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. 2012.

Kassie GG, Hayelom DH. Assessment of water handling and sanitation practices among rural communities of Farta Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia. Amer J Health Res. 2017;5(5)

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34.

Worldatlas: Where Is Ethiopia? 2015.

Newcastle: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale customized for cross-sectional studies In. available from https://static-content.springer.com/esm/.../12889_2012_5111_MOESM3_ESM.doc . 2012.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synt Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111.

Mulugeta Debel Bultume, David Sanders, D. HM: Utilization of the Health Extension program Services in Akaki District, Ethiopia. 2011.

Yimam T, Kassahun A. DH. C: latrine utilization and associated factors among people living in rural areas of Denbia district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2013, a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2014;

Sahlu C, Worku A, M. H: Latrine Utilization and Associated Factors in Rural Community of Amhara Region , Ethiopia : A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study. 2016.

Oljira D, B. T: latrine use and determinant factors in Southwest Ethiopia .. Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Rev 2016, 1(6).

Berhanu A, Muluken A. B. G: latrine access and utilization among people with limited mobility: a cross sectional study .. Archives of . Public Health. 2016;74(9)

Haftay Gebremedhin, Teame Abay, Tesfay Gebregzabher, Dejen Yemane, Gebremedhin Gebreegziabiher, S. B: Latrine utilization and associated factors in south East Zone of Tigray region, North Ethiopia . European Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016, 3(6).

Lemma Tulu AK, Hawas SB, Demissie HF, Segni MT. latrine utilization and associated factors among kebeles implementing and non implementing Urban Community led Total sanitation and hygiene in Hawassa town, Ethiopia. Afr J Environ Sci Technol. 2017;11(3)

Neguse D, Lalit i, Azeb G, HDY A. latrine utilization and associated factors in the rural communities of Gulomekada District, Tigray region, North Ethiopia, 2013: a community based cross-sectional study. Community Medicine & Health Educ. 2015;5(2)

Yemane A, Hardeep Rai S, Kassahun AKG. Latrine use among rural households in northern Ethiopia: a case study in Hawzien district. Tigray International Journal of Environmental Studies. 2013;70(40)

Okechukwu OI, Okechukwu AA, Noye-Nortey H, Owusu-Agyei. toilet practices among the inhabitants of Kintampo District of northern Ghana. J Med and Med Sciences. 2012;3(8):524.

Anne N, Charles BN, Nyenje PM, Robinah NK, BTKF J. Are pit latrines in urban areas of Sub-Saharan Africa performing? A review of usage, filling, insects and odor nuisances. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(120) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2772-z .

The Millennium Development Goals Report asdf United States . 2015.

Sharmani B, Parimita R, Fiona M, Rachel P, Sophie B, Antara SCT: Impact of Indian Total Sanitation Campaign on LatrineCoverage and Use: A Cross-Sectional Study in OrissaThree Years following Programme Implementation.

The Millennium Development Goals Report 2017.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health: Health Sector Development Programme IV 2010/11–2014/15. FINAL DRAFT October 2010, version 19 March.

Report Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2014.

OV. Garna, GD. Sclar a, MC. Freemana, G Penakalapati a, KT. Alexander a, P Brooks a, EA. Rehfuess b, S Boissonc, KO. Medlicott c, TF. Clasena: The impact of sanitation interventions on latrine coverage and latrine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis 2013.

SS Budhathoki, M Bhattachan, SB Singh, N Jha, APK O: Latrine coverage and its utilisation in a rural village of Eastern Nepal: a community-based cross-sectional study.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health: Ministry of Health National Hygiene and Sanitation Strategy Ethiopia. 2004.

packages. HE. Health extension and education center Federal Ministry of Health Addis Ababa. In: Ethiopia; 2007.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this work would like to forward great and deepest gratitude for Debremarkos University for creating convenient environment and internet service. Last but not least, we would like to forward our acknowledgement for Dr. Belete Tafesse, who is a fluent in English and experienced academics in editing a manuscript for his time spent and willingness to edit this manuscript and made the necessary revision.

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon request of the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

Cheru Tesema Leshargie, Nakachew Mekonnen Alamirew, Yihalem Abebe Belay, Aster Ferede, Dube Jara Boneya, Molla Yigzaw Birhanu & Getiye Dejenu Kibret

Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

Animut Alebel, Henok Mulugeta, Bekele Tesfaye, Fasil Wagnew, Mezinew Sintayehu & Getnet Dessie

Department of Human Nutrition and Food Science, College of Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

Ayenew Negesse

Department of Medical Laboratory technology, College of Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

Getachew Mengistu

Department of Biomedical Science, School of Medicine, Debre Markos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

Amsalu Taye Wondemagegn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CTL: Conception of research protocol, study design, literature review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation and drafting the manuscript. AA, AN, GM, AT, HM, BT, NM, FW, YAB, AF, MS, GDA, DJB, MYB and GDK: data extraction and quality assessment, data analysis and reviewing manuscript. MYB: revised the entire section of the final manuscript critically. And also he gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cheru Tesema Leshargie .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Quality assessment of 19 included studies. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 2:

Descriptive summary of 19 studies included in the meta-analysis of the level of latrine utilizations and its association with educational status in Ethiopia. (DOCX 22 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Leshargie, C.T., Alebel, A., Negesse, A. et al. Household latrine utilization and its association with educational status of household heads in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 18 , 901 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5798-6

Download citation

Received : 01 March 2018

Accepted : 04 July 2018

Published : 20 July 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5798-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Latrine-utilizations

- Educational-status

- Systematic-review

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Nurs

- v.9; Jan-Dec 2023

- PMC10201159

A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study on Latrine Utilization and Associated Factors Among Rural Community of East Meskan District, Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia

Elsabet negussie zewede.

1 Department of Public Health, Adama Hospital Medical College, Adama, Ethiopia

Nardos Tilahun Bekele

Yohannes mekuria negussie.

2 Department of Medicine, Adama General Hospital and Medical College, Adama, Ethiopia

Mihiret Shawel Getahun

3 Department of Nursing, Adama General Hospital and Medical College, Adama, Ethiopia

Abenet Menene Gurara

4 Department of Nursing, Arsi University, Asella, Ethiopia

Using sanitary facilities is proven to enhance health and halt the spread of fecal-to-oral disease. Despite efforts to improve the availability of latrine facilities in developing countries like Ethiopia, finding a village that is entirely free of open defecation remains difficult. To determine the need for intervention programs and promote regular latrine usage, local data is essential.

This study aimed to assess latrine utilization and associated factors among households in East Meskan District, Southern Ethiopia.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 630 households from April 15 to May 30, 2022. A simple random sampling technique was used to select the study households. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire and an observational checklist. The collected data were then entered into Epi-Info version 7.1 and analyzed using SPSS version 21. In binary logistic regression analysis, independent variables with a P -value < .25 were considered candidates for multiple logistic regression analysis. The association was expressed in odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI), and significance was declared at P -value < .05 in the final model.

The magnitude of latrine utilization was 73.3% (95% CI: 69.7, 76.8) in the study district. Husband being family head (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 12.9; 95% CI: 5.78 ,28.90), being female (AOR = 16.4; 95% CI: 6.52, 41.27), family size less than 5 (AOR = 24.2; 95% CI: 11.49, 51.09), absence of school children (AOR = 0.3; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.51), and greater than 2 years since latrine was constructed (AOR = 14; 95% CI: 7.18, 27.41) had a significant association with latrine utilization.

In this study, utilization of latrines was low compared to the national target plan. Family head, sex, family size, presence of school children, and length of years in which the latrine was constructed were factors associated with latrine utilization. Thus, regular supervision of early latrine construction and utilization in communities is essential.

Latrines are excreta disposal facilities that can safely separate human excreta from human and insect contact. The use of sanitation facilities is known to halt the spread of fecal-to-oral disease. In addition to their physical presence, effective sanitation facility utilization enhances health ( Tamene & Afework, 2021 ).

More than 2.5 billion people worldwide lack access to sanitation and hygienic facilities, particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have the highest percentages of these people. Diseases attributed to inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene account for more than 4% of all disease burdens and deaths ( Abebe et al., 2020 ; Garn et al., 2017 ). In SSA countries like Ethiopia, 76% of the rural population did not have access to proper sanitary facilities, and a high burden of diarrheal infections existed ( Nunbogu et al., 2019 ). The percentage of households with latrine facilities increased nationwide from 55% in 2011 to 61% in 2016, according to the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Surveys (EDHS) report. In rural areas, 59% of families utilize unimproved toilet facilities ( Girma et al., 2018 ; Tamene & Afework, 2021 ). The progress, however, fell far short of the national target, which was set at 100% ( Gebremariam & Tsehaye, 2019 ).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.5 million children die each year from diarrhea, which is caused by a combination of poor sanitation and poor personal hygiene ( Farah et al., 2015 ). In developing nations, 88% of all deaths from diarrheal diseases are caused by inadequate access to sanitation, the use of contaminated drinking water, and poor hygiene combined. Improvements in sanitation alone, according to sanitation and health experts, have the potential to reduce parasite infections that harm children’s development and the global prevalence of diarrheal disease, which is a primary cause of death for children, by one-third ( Beyene et al., 2015 ; Islam et al., 2018 ). Because of inadequate sanitation, 15% of all fatalities result from diarrhea, primarily among a large number of children under the age of five. In addition to diarrheal illnesses, worm infestations are very common and significantly increase malnutrition levels ( Godana & Mengistie, 2017 ; Ssekamatte et al., 2019 ).

Review of Literature

The combined global economic loss in 2015 attributed to early deaths connected to sanitation, medical costs for diseases related to sanitation, output lost due to illness, and time lost to use sanitation facilities was projected to be 222.9 billion dollars ( Godana & Mengistie, 2017 ; Nyanza et al., 2018 ; Tamene & Afework, 2021 ).

Studies conducted in several regions of Ethiopia to evaluate latrine utilization and associated factors indicated that the prevalence of latrine utilization is unsatisfactory and ranges from 60% to 71% in various settings ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ; Koyra et al., 2017 ). The use of latrines can be affected by a range of behavioral, cultural, social, geographic, and economic factors differing across communities ( Leshargie et al., 2018 ).

Despite years of effort to increase the availability of latrine facilities, it is still difficult to find a village that is completely free from open defecation. The country's report points out a large discrepancy between the availability and utilization of latrine facilities in rural communities ( Beyene et al., 2015 ). It is necessary to conduct such studies because the government's regular report on both latrine coverage and utilization has indicated a gap between what is real and what is desired. Open defecation and unsafe excreta disposal continue to be widespread in the study area, with major public health and economic consequences. Data on the utilization of latrines is still inadequate. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the utilization of latrine facilities and identify the associated factors that are helpful strategies to fill the identified gaps. Moreover, the findings of this study will help the health sectors at different levels, communities, and local decision-makers for health intervention programs with a view of adding to the existing body of knowledge to improve sanitation facilities in the study area in particular and reduce open defecation through different strategies.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 15 to May 30, 2022. East Meskan district is located 155 kilometers southeast of Addis Ababa, 90 kilometers east of Wolkite town, the administrative center of the Gurage zone, and 20 kilometers east of Butajira town. In 2021, the district administration office reports a total population of approximately 67,891 people, 34,624 females, and 33,267 males. The district has 15 kebeles (a small administrative unit in Ethiopia) , (one urban and 14 rural), and the total number of households is 13,855. There are three health centers and 14 health posts in the district. The current study was conducted on seven rural kebeles namely Elle, Bati Legano, Waja Bati, Bati futo, Ensenousme, Bamo, and Yemrwach.

Research Questions

- What is the magnitude of latrine utilization and associated factors among the rural community of East Meskan District, Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia?

- What are the factors that are associated with latrine utilization and associated factors among the rural community of East Meskan District, Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia?

An independent sample size was calculated for the two specific objectives of the current study and the largest sample was taken. The largest sample size was the one calculated using the single population proportion formula with the following assumptions: Based on a similar study done in Chencha District, SNNPR state where 60% of rural communities utilized latrines ( Koyra et al., 2017 ), with margin of error of 4% at the 95% confidence level, and with a 10% non-response rate, thus the total sample size required is 640 households.

Using a simple random sampling technique, seven kebeles were chosen at random from a total of 14 kebeles . Each of the selected kebeles received a consecutive sample size based on a proportional allocation to household number. Following that, study households were chosen from each selected kebele using simple random sampling from lists of households obtained from each kebele office executed via the lottery method. The household heads were then interviewed in the selected households, and observations were made ( Figure 1 ).

Schematic presentation of sampling procedure to assess latrine utilization and associated factors in East Meskan district Gurage zone, Southern, Ethiopia, 2022.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The study populations were all households that have latrines in the selected kebeles of East Meskan District. Household heads that had lived for more than 6 months were included in the study. Members of each household who were less than 18 years old during the data collection period were excluded as study participants.

Data Collection

The data were collected by using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire and observational checklist, which were developed after reviewing previous studies and different literature ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ; Beyene et al., 2015 ). The questionnaire was initially prepared in English then translated into Amharic and then translated back into English by different experienced persons to check the consistency of meaning. Data were collected by seven diploma nurses and supervised by two BSc Environmental Health professionals. The questionnaires were pre-tested on 5% of the total sample size of the study households in non-selected Beche bulchano kebele to ensure consistency in terms of easy understandability, coherence, and completeness to households. Data collectors and supervisors received one-day training on the data collection process. Supervisors reviewed and checked the collected data every day for completeness and consistency.

Study Variables

In the present study, the dependent variable is latrine utilization, and the independent variables are age, sex, religion, ethnicity, occupational status, educational status, marital status, average, monthly income, family size, presence of under-five children, and presence of schoolchildren.

Operational Definitions

Latrine utilization: Households with functioning latrines of any design must exhibit at least these indicators of use: a functional footpath to the toilet or pavement covered in grass, the presence of fresh feces near the squat hole, the absence of a spider web in the gate, wetness of the slab, visible anal cleansing materials, and the presence of flies ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ; Omer et al., 2022 ).

School children: Refers to whether there are any children in the household who are enrolled in formal education at the elementary school level or higher ( Woyessa et al., 2022 ).

Latrine maintenance: Maintaining the existing functional latrine in case of broken sub or superstructures without digging a new hole ( Koyra et al., 2017 ).

Shared latrines: Sanitation facilities shared between two or more households. Shared facilities include public toilets.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were entered into Epi-Info version 7 and then exported to SPSS version 21 for analysis. Before analysis, data processing activities such as cleaning and coding were performed. Normality for continuous variables was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the magnitude of latrine utilization. Binary logistic regression was used to model the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variable. The statistical assumptions for binary logistic regression (adequacy of sample in each cross-tabulated result, expected count in each cell) were assessed, and multi-collinearity was checked using variation inflation factor (VIF) at VIF > 10 indicating the presence of multi-collinearity. Simple logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent variables with a P -value < .25 considered a candidate for the multiple logistic regression analysis. Multiple logistic regression was applied to estimate the effects of independent variables on latrine utilization after adjusting for the effects of possible confounding effects. The regression model was fitted using the standard model-building approach. In the process of fitting the model, variables that didn’t have a significant association with latrine utilization at P -value < .05 were excluded from the model. The odds of latrine utilization were estimated using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). At this level, the significance of associations was declared at a P -value of .05. The model fitness test was checked by the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test at P -value ≥ .05.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

In this study, a total of 630 households participated, giving a 98.4% response rate. Of these 504 (80%) respondents were female, 546 (86%) respondents were Gurage by ethnicity, and 567 (89.4%) respondents were Muslim. Regarding marital status, 589 (89%) of respondents were married. The study showed that a family size less than 5 was 357 (56.7%) and 420 (66%) of households have under-five children. About 301 (47.6%) of heads of household were farmers and 357 (56.7%) of them were unable to read and write ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents in a Rural Community of East Meskan District, 2022 ( n = 630).

Note. HHs = households; ETB = Ethiopian birr.

Behavioral Factors

Five hundred and forty-six (86.7%) of the respondents who had latrines explained that they were advised by health extension workers to construct latrines. All 100% of respondents explained that the importance of having a latrine is to prevent disease and to keep a clean village. In this study, 323 (70%) respondents washed their hands after using the latrine and 267 (82.8%) of them washed their hands after using the latrine with only water ( Table 2 ) .

Table 2.

Behavioral Factors of the Rural Households in East Meskan District 2022 ( n = 630).

Characteristics of Latrine Facilities

Among the household latrines, 441 (70%) of them needed maintenance. Latrine superstructures made of wood and plastic accounted for 231 (36.7%), while wood and cloth accounted for 169 (26.8%). A total of 567 latrines (90%) were privately owned, 441 (70%) of latrines had a door and in 147 (23.3%) of latrines, feces were observed on the floor. 525 (83.3%) had been more than two years since the construction of the latrine ( Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Latrine Facilities in Rural Households of East Meskan District, 2022 ( n = 630).

Research Question Results

Latrine utilization.

The result of this study showed that the magnitude of latrine utilization among the East Meskan district rural community was 73.3% (95% CI: 69.7, 76) ( Figure 2 ). Of those who did not practice latrine utilization 105 (62.5%) participants claimed that the unreasonable unpleasant odor was their reason ( Figure 3 ).

Latrine utilization in a rural community of East Meskan district, Gurage zone, Southern, Ethiopia, 2022.

Study participant's reasons for not practicing latrine utilization in a rural community of East Meskan district, Gurage zone, Southern, Ethiopia, 2022 ( n = 168).

Factors Associated with Latrine Utilization

Family head, sex, occupation, educational status, family size, under-five children, presence of school children, privately owned latrine, the component of latrine, years since latrine was constructed, and status of latrine were the variables that fulfilled the criteria P < .25 and transferred to multivariable analysis. After adjusting for confounder variables in the multivariable analysis, family head, sex of respondent, family size, presence of school children, and years since the latrine was constructed were significantly associated with latrine utilization.

Accordingly, in the multivariable analysis respondents with a family head being a husband were 12.9 (AOR = 12.9, 95% CI: 5.78, 28.90) times more likely to utilize a latrine than a family head being a wife. Regarding the sex of respondents, females were 16.4 (AOR = 16.4, 95% CI: 6.52, 41.27) times more likely to utilize latrines than males. Regarding family size, those households who had a family size of less than five were 24 (AOR = 24.2, 95% CI: 11.49, 51.09) times more likely to utilize a latrine than a family size more than and equal to five. Households who do not have school children were 70% (AOR = 0.3, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.51) less likely to utilize a latrine than Households who have school children. Households with more than two years since the construction of the latrine were 14 (AOR = 14, 95% CI: 7.18, 27.41) times more likely to utilize a latrine than those who constructed their latrine less than or equal to two years ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Latrine Utilization in a Rural Community of East Meskan District, 2022.

Abbreviations: COR = crude odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

Note. *Significant at P -value < .25 in unadjusted logistic regression analysis, **significant at P < .05 in adjusted logistic regression analysis, 1 = Reference.

The main objective of this study was to assess the level of latrine utilization and its associated factors in the East Meskan District. Accordingly, the present study revealed that the level of latrine utilization in the community of the study area was 73.3% [(95% CI: 69.6–76.97)]. This study's findings were higher than those of Chencha District (60%) ( Koyra et al., 2017 ), Dembia District (61.2%) ( Yimam et al., 2014 ), and Aneded District (63%) in North West Ethiopia ( Chanie et al., 2016 ). However, it was lower than the finding in Derashe District (88.7%) ( Godana & Mengistie, 2017 ), Mahal Meda (91.2%) ( Abebe et al., 2020 ), and a report from the rural village of Vietnam (79.2%) ( Le & Makarchev, 2020 ).

This variation could be explained by the fact that the study population of these areas could have socioeconomic and cultural differences and may also be due to sample size and study period differences. The relatively higher prevalence of latrine utilization could be attributed to the fact that the majority of residents in this area are Muslim; Muslims in general have extremely high personal hygiene standards, as Islam places a high value on both physical and spiritual cleanliness and purification. While humankind in general usually considers cleanliness to be a pleasing attribute, Islam insists on it.

The study revealed that respondents with the head of the family being the husband were 12.9 times more likely to utilize a latrine compared to the head of the family the wife. The result was supported by a similar study conducted in a rural village in Vietnam ( Le & Makarchev, 2020 ). The reason could be that in many female-headed households, low income combined with a lack of technical expertise or physical ability to dig soil and erect latrines severely limits the sanitation options available to them.

According to this study, females were 16.4 times more likely to utilize a latrine than males. This could be because many of the men and a few of the women work in their farm fields from dawn to dusk. For many, the lack of community-level public latrines near their farms encouraged open defecation. They do not return to their residence to use the latrine when they are on the farm because it is too far away.

Households with a family size of less than five were 24 times more likely to utilize a latrine than households with a family size greater and equal to five. This result was supported by a similar study conducted in semi-urban areas of northeastern Ethiopia ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ). This could be because the family size is too large, and if there aren't enough squat holes, the chances of finding a latrine that isn't already occupied by another member decrease. Sharing a latrine among a small number of family size results in less frequent latrine usage, which increases the chance of the latrine being cleaner, this in turn increases latrine utilization. Sharing a latrine with a large family, on the other hand, increases the number of times the latrine is used daily and puts a person's sense of responsibility to use the latrine properly in danger, resulting in the latrine being dirty, which may decrease latrine utilization. Furthermore, because latrines in rural areas are built at a shallow depth, they will be out of service sooner ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ).

Households who do not have school children were 70% less likely to utilize latrines than households who have school children. This study was supported by other studies Achefer District Amhara Region ( Kishiru et al., 2019 ) and Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda ( Anteneh & Kumie, 2010 ). The justification could be school children may have gotten information from the school about sanitation and implemented it with their parents and developed awareness in the community ( Koyra et al., 2017 ).

Households with more than two years since the construction of the latrine were 14 times more likely to utilize a latrine than their counterpart. This result was supported by other studies done Mahal Meda ( Abebe et al., 2020 ) and Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda ( Anteneh & Kumie, 2010 ). This could be because behavioral changes in the community require a lot of time. The longer they use the latrine, the more comfortable they become with it and the more they notice the positive effects of using it ( Asnake & Adane, 2020 ).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The main strength of this study was its attempt to address a neglected health concern in the study area by obtaining data from primary sources. As a limitation, the study was cross-sectional; therefore, it is difficult to establish a temporal relationship between the dependent and independent variables. In the absence of follow-up, the magnitude of latrine utilization and other independent variables may be greatly underestimated or overestimated in this study. Although on-the-spot observation was used to determine latrine utilization during the study period, it was difficult to determine whether there was the consistent use of the latrine using.

This study concluded that latrine utilization was found to be low. Family head, sex, family size, presence of school children, and the length of years in which the latrine was constructed were the major predictors affecting the utilization of latrines. East Meskan District Health Office should conduct regular supervision of early latrine construction and use in the communities.

Implications for Practice and Research

Open defecation and inadequate sanitation are frequently connected to diarrhea and other communicable diseases. Increased open defecation rates are also linked to serious economic, environmental, and substantial public health effects that have an impact on the general well-being and dignity of mankind. Regular supervision of early latrine construction and utilization in communities should be conducted. Households with latrines should have enough latrines to accommodate the number of people living in the same household and adapt to latrine usage.

To enhance knowledge regarding the causes, modes of transmission, and contribution of human waste to the incidence of infectious illnesses, a variety of diverse actions, strategies, and programs must be implemented. Having said that, nurses design initiatives to promote community health and educate people about the risks associated with not using latrines. Changing habits that can significantly affect someone's health is the ultimate goal. Researchers should further investigate with qualitative research to understand the behavioral aspects of the community and the effective utilization of latrines and associated factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the East Meskan District Health Office and the kebele administrative for their invaluable assistance in providing necessary information and facilitating data collection. We are extremely grateful to the participants and data collectors.

Authors’ Contributions: ENZ worked on the conception and design of the study, training and supervising the data collectors, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. NTB redid the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. NTB and YMN critically reviewed the draft manuscript and wrote the final version. MSG and AMG advised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethical approval and clearance were obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Adama Hospital Medical College, and a letter was submitted to the Gurage Zone health department and East Meskan District Health office, and respective Kebele administrators. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, the importance, and the duration of the study to get their free time. The information sheet and consent were provided for respondents for those who can read and the interviewer read for those who can’t read. Verbal consent from all study subjects was obtained before data collection. Participants were informed that they have the full right to discontinue or refuse to participate in the study or to be interviewed. To ensure confidentiality, the name of the interviewee was not written on the questionnaire.

ORCID iDs: Nardos Tilahun Bekele https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6303-1347

Yohannes Mekuria Negussie https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1332-670X

Mihiret Shawel Getahun https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2758-2760

- Abebe A. M., Kassaw M. W., Mekuria A. D., Yehualshet S. S., Fenta E. A. (2020). Latrine utilization and associated factors in Mehal Meda Town in North Shewa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia, 2019 . BioMed Research International , 2020 ( 1 ), 1–9. 10.1155/2020/7310925 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anteneh A., Kumie A. (2010). Assessment of the impact of latrine utilization on diarrhoeal diseases in the rural community of Hulet Ejju Enessie Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region . Ethiopian Journal of Health Development , 24 ( 2 ). 10.4314/ejhd.v24i2.62959 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asnake D., Adane M. (2020). Household latrine utilization and associated factors in semi-urban areas of northeastern Ethiopia . PLoS One , 15 ( 11 ), e0241270. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241270 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beyene A., Hailu T., Faris K., Kloos H. (2015). Current state and trends of access to sanitation in Ethiopia and the need to revise indicators to monitor progress in the post-2015 era . BMC Public Health , 15 ( 1 ), 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2458-15-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chanie T., Gedefaw M., Ketema K. (2016). Latrine utilization and associated factors in rural community of Aneded district, North West Ethiopia, 2014 . Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education , 6 ( 478 ), 1–12. 10.4172/2161-0711.1000478 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farah S., Karim M., Akther N., Begum M., Begum N. (2015). Knowledge and practice of personal hygiene and sanitation: A study in selected slums of Dhaka city . Delta Medical College Journal , 3 ( 2 ), 68–73. 10.3329/dmcj.v3i2.24425 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garn J. V., Sclar G. D., Freeman M. C., Penakalapati G., Alexander K. T., Brooks P., Clasen T. F. (2017). The impact of sanitation interventions on latrine coverage and latrine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis . International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health , 220 ( 2 ), 329–340. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.001 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gebremariam B., Tsehaye K. (2019). Effect of community led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH) implementation program on latrine utilization among adult villagers of North Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study . BMC Research Notes , 12 ( 1 ), 1–6. 10.1186/s13104-018-4038-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Girma A., Tegegn B., Nigatu C. (2018). Consumer drivers and barriers of WASH products use in rural Ethiopia. Paper presented at the Transformation towards sustainable and resilient WASH services: Proceedings of the 41st WEDC International Conference, Nakuru, Kenya. [ Google Scholar ]

- Godana W., Mengistie B. (2017). Exploring barriers related to the use of latrine and health impacts in rural Kebeles of Dirashe district Southern Ethiopia: Implications for community lead total sanitations . Health Science Journal , 11 ( 2 ), 0–0. 10.21767/1791-809X.1000492 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Islam M., Ercumen A., Ashraf S., Rahman M., Shoab A. K., Luby S. P., Unicomb L. (2018). Unsafe disposal of feces of children< 3 years among households with latrine access in rural Bangladesh: Association with household characteristics, fly presence and child diarrhea . PLoS One , 13 ( 4 ), e0195218. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195218 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kishiru A., Azage M., Zewale T. A., Bogale K. A. (2019). Latrine utilization and its associated factors among Rural Communities of North Achefer District, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia.

- Koyra H. C., Sorato M. M., Unasho Y. S., Kanche Z. Z. (2017). Latrine utilization and associated factors in rural community of Chencha district, southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study . American Journal of Public Health Research , 5 ( 4 ), 98–104. 10.12691/ajphr-5-4-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Le D. A., Makarchev N. (2020). Latrine use practices and predictors in rural Vietnam: Evidence from Giong Trom district, Ben Tre . International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health , 228 , 113554. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113554 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leshargie C. T., Alebel A., Negesse A., Mengistu G., Wondemagegn A. T., Mulugeta H., Tesfaye B., Alamirew N. M., Wagnew F., Belay Y. A., Ferede A., Sintayehu M., Dessie G., Boneya D. J., Birhanu M. Y., Kibret G. D. (2018). Household latrine utilization and its association with educational status of household heads in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis . BMC Public Health , 18 ( 1 ), 1–12. 10.1186/s12889-018-5798-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nunbogu A. M., Harter M., Mosler H.-J. (2019). Factors associated with levels of latrine completion and consequent latrine use in northern Ghana . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 16 ( 6 ), 920. 10.3390/ijerph16060920 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nyanza E. C., Jahanpour O., Hatfield J., van der Meer F., Allen-Scott L., Orsel K., Bastien S. (2018). Access and utilization of water and sanitation facilities and their determinants among pastoralists in the rural areas of northern Tanzania . Tanzania Journal of Health Research , 20 ( 1 ), 1–10. 10.4314/thrb.v20i1.2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Omer N., Bitew B. D., Engdaw G. T., Getachew A. (2022). Utilization of latrine and associated factors among rural households in Takussa district, Northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study . Environmental Health Insights , 16 , 11786302221091742. 10.1177/11786302221091742 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ssekamatte T., Isunju J. B., Balugaba B. E., Nakirya D., Osuret J., Mguni P., Mugambe R., van Vliet B. (2019). Opportunities and barriers to effective operation and maintenance of public toilets in informal settlements: Perspectives from toilet operators in Kampala . International Journal of Environmental Health Research , 29 ( 4 ), 359–370. 10.1080/09603123.2018.1544610 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamene A., Afework A. (2021). Exploring barriers to the adoption and utilization of improved latrine facilities in rural Ethiopia: An integrated behavioral model for water, sanitation, and hygiene (IBM-WASH) approach . PLoS One , 16 ( 1 ), e0245289. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245289 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woyessa E. T., Ashenafi T., Ashuro Z., Ejeso A. (2022). Latrine utilization and associated factors among community-led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH) implemented Kebeles in Gurage zone, Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study . Environmental Health Insights , 16 , 11786302221114819. 10.1177/11786302221114819 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yimam Y. T., Gelaye K. A., Chercos D. H. (2014). Latrine utilization and associated factors among people living in rural areas of Denbia district, Northwest Ethiopia, 2013, a cross-sectional study . The Pan African medical journal , 18 . 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.334.4206 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Previous Article

- Next Article

INTRODUCTION

Methodology, results and discussion, data availability statement, conflict of interest, a historical and critical review of latrine-siting guidelines.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions

- Search Site