Leveraging service design as a multidisciplinary approach to service innovation

Journal of Service Management

ISSN : 1757-5818

Article publication date: 26 September 2019

Issue publication date: 15 November 2019

Service design is a multidisciplinary approach that plays a key role in fostering service innovation. However, the lack of a comprehensive understanding of its multiple perspectives hampers this potential to be realized. Through an activity theory lens, the purpose of this paper is to examine core areas that inform service design, identifying shared concerns and complementary contributions.

Design/methodology/approach

The study involved a literature review in two stages, followed by a qualitative study based on selected focus groups. The first literature review identified core areas that contribute to service design. Based on this identification, the second literature review examined 135 references suggested by 13 world-leading researchers in this field. These references were qualitatively analyzed using the NVivo software. Results were validated and complemented by six multidisciplinary focus groups with service research centers in five countries.

Six core areas were identified and characterized as contributing to service design: service research, design, marketing, operations management, information systems and interaction design. Data analysis shows the various goals, objects, approaches and outcomes that multidisciplinary perspectives bring to service design, supporting them to enable service innovation.

Practical implications

This paper supports service design teams to better communicate and collaborate by providing an in-depth understanding of the multiple contributions they can integrate to create the conditions for new service.

Originality/value

This paper identifies and examines the core areas that inform service design, their shared concerns, complementarities and how they contribute to foster new forms of value co-creation, building a common ground to advance this approach and leverage its impact on service innovation.

- Service innovation

- Multidisciplinary

- Service design

Prestes Joly, M. , Teixeira, J.G. , Patrício, L. and Sangiorgi, D. (2019), "Leveraging service design as a multidisciplinary approach to service innovation", Journal of Service Management , Vol. 30 No. 6, pp. 681-715. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-07-2017-0178

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Maíra Prestes Joly, Jorge Grenha Teixeira, Lia Patrício and Daniela Sangiorgi

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Service design has grown as a human-centered, collaborative, holistic approach focused on improving existing services or creating new ones ( Blomkvist et al. , 2011 ; Mahr et al. , 2013 ; Ostrom et al. , 2015 ; Teixeira et al. , 2017 ; Yu and Sangiorgi, 2018 ). Service design can bring new service ideas to life by understanding customer experiences ( Mahr et al. , 2013 ), envisioning new value propositions ( Ostrom et al. , 2015 ), supporting the introduction of technology into service ( Teixeira et al. , 2017 ) and contributing to the entire new service development (NSD) process ( Yu and Sangiorgi, 2018 ). This approach integrates design thinking with a service perspective ( Wetter-Edman et al. , 2014 ) and brings together multidisciplinary contributions, such as the value proposition offered to the customer ( Edvardsson et al. , 2000 ), service interfaces that embody service offerings ( Secomandi and Snelders, 2011 ), service operations ( Hill et al. , 2002 ) and supportive technologies that fuel service innovation ( Kieliszewski et al. , 2012 ).

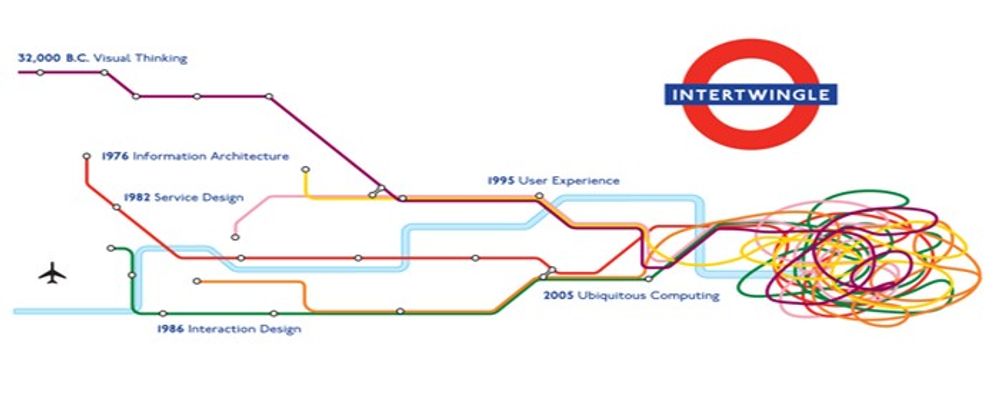

Multidisciplinarity means juxtaposing disciplinary contributions (e.g. concepts and approaches), in order to foster wider knowledge to tackle a common issue ( Gustafsson, Högström, Radnor, Friman, Heinonen et al. , 2016 ; Klein, 2010 ).While an intra-disciplinary approach to research theorizes within the boundaries of a discipline, within a multidisciplinary approach one borrows theory from one discipline to another, advancing knowledge in other fields. However, these disciplines are coordinated to remain separated, maintaining the original identity of their elements and not crossing their existing knowledge structures. A multidisciplinary approach, then, differs from interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary perspectives, where the focus is, respectively, to integrate knowledge from two or more disciplines and to build a comprehensive theory that arises from a common theoretical understanding of the preexisting disciplines ( Gustafsson, Högström, Radnor, Friman, Heinonen et al. , 2016 ).

While service design is considered a multidisciplinary field, its contributions often adapt a specific disciplinary stance, lacking a more complete and integrated approach that encompasses the entire range of multidisciplinary contributions to fully support the design of new value propositions. For instance, while some perspectives focus on the material and design process-oriented aspects of service design ( Kimbell, 2011 ; Secomandi and Snelders, 2011 ), others focus on the customer experience enabled by its approach ( Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010 ; Andreassen et al. , 2016 ) and, still others, on how it can create new operations and technology to support the service delivery ( Sampson, 2012 ; Glushko, 2010 ). These different views offer a valuable contribution for specific aspects of service design. However, considering its holistic approach, there is a lack of a comprehensive understanding about which are the main multidisciplinary perspectives that inform service design and which contributions they bring. The lack of this understanding hinders the dialog and shared ground among service designers coming from different backgrounds, risking for researchers and practitioners to build knowledge in silos ( Anderl et al. , 2009 ).

The lack of a shared understanding among service design perspectives has implications on service innovation, since service design has been championed as a service innovation approach ( Mahr et al. , 2013 ; Ostrom et al. , 2015 ; Teixeira et al. , 2017 ; Yu and Sangiorgi, 2018 ; Patrício, Gustafsson and Fisk, 2018 ). Service innovation has been defined as the creation of new service offerings, service delivery processes and service business models ( Ostrom et al. , 2010 ). From a service-dominant logic (S-D logic) perspective, this definition has been reframed to understand service innovation as a process of integrating resources in novel ways to enable new forms of value co-creation among actors ( Lusch and Nambisan, 2015 ). Due to the multidimensional character of service innovation ( Gustafsson, Kristensson, Schirr and Witell, 2016 ), supporting it from multidisciplinary lenses is a strategic imperative for service researchers and practitioners who aim to understand and generate new forms of value co-creation within service ecosystems ( Lusch and Nambisan, 2015 ).

Service design has a key role in service innovation as it brings new service ideas to life ( Ostrom et al. , 2010, 2015 ). However, it is not clear how different multidisciplinary perspectives contribute to service design and, consequently, how these perspectives support service design to enable service innovation. This challenge demands that service design evolves as a multidisciplinary activity, able to take into account complementary aspects related to service innovation ( Lusch and Nambisan, 2015 ).

This paper addresses the challenges of the lack of a comprehensive understanding about which are the main multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design, and which are cross-cutting areas and complementarities that work as bridges between these multiple perspectives, strengthening service design approach to service innovation. In this sense, this paper presents a study focused on understanding “How do multidisciplinary perspectives contribute to service design and support this approach to enable service innovation?” By addressing these challenges, this paper brings two fundamental contributions to advance service design as a multidisciplinary activity to service innovation: the identification, characterization and systematization of core multidisciplinary perspectives on service design; and an integrative examination of how these perspectives contribute to service design, supporting it as a service innovation approach.

This analysis of the multidisciplinary perspectives on service design was supported by activity theory ( Wertsch, 1979 ; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ). Through an activity theory lens, service design can be understood as an activity composed by goals, objects, approaches and outcomes ( Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ; Wertsch, 1979 ). An activity is developed by a subject who can be a person or a group of people. The subject who acts over an object is part of a community of practice, which is a unit broader than the individual action ( Lave and Wenger, 1991 ; Engeström et al. , 1999 ). Activity theory offers a suitable framework to understand how multidisciplinary communities have different ways of developing the service design activity, which is reflected on their distinct goals, object, approaches and outcomes.

As such, this paper identifies core multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design, addressing the call to reinforce the foundations of service design as an interdisciplinary research field ( Patrício, Gustafsson and Fisk, 2018 ). Nonetheless, the paper brings a key contribution to service researchers and practitioners by supporting a better understanding of service design as an activity able to tackle complementary levels of complexity of service projects ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ).

2. Theoretical background

This section introduces multiple perspectives associated with service design and service innovation. This literature review presents service design as a multidisciplinary approach and service innovation as a multidimensional phenomenon.

2.1 Service design

The term “service design” was originally employed in the context of service blueprint design ( Shostack, 1982 ) and as a specific step within a NSD process ( Scheuing and Johnson, 1989 ), focused on generating ideas and formulating service concepts ( Johnson et al. , 2000 ). In the 1990s, service design began to be treated as a discipline within the design field, because of the interest among the design community in exploring and understanding the application of design capabilities to the service sector ( Erlhoff et al. , 1997 ; Pacenti, 1998 ). More recently, a renewed interest in service innovation has focused attention on “leveraging service design” as a key research priority in service research ( Ostrom et al. , 2015 ). Service design and innovation can increase the relevance of service research by addressing important real-world problems, whether in organizations or society ( Patrício, Gustafsson and Fisk, 2018 ).

Multidisciplinary perspectives have contributed to service design, focusing on different aspects. Shostack (1982, 1984) addresses service design by systematically planning the sequence of the various events and service evidences that are involved during service operations. Zomerdijk and Voss (2010) discuss service design in the context of experience-centric services, focused on crafting the customer experience to create distinctive service offerings. Glushko (2010) , on the other hand, describes person-to-person, person-to-machine and machine-to-machine interactions as different use cases that service design can be applied to. Kimbell (2011) describes service design as an exploratory process, where designers approach their work as an open-ended inquiry. Secomandi and Snelders (2011) discuss the service interface as the object of service design, which can include material artifacts, environments and embodied human interactions to intermediate service encounters. Andreassen et al. (2016) present a service research perspective on service design, by describing it as an approach that can aid providers in their efforts to become more customer centric. Likewise, Karpen et al. (2017) examine capabilities, practices and abilities which facilitate the use of service design within organizations.

These multiple research efforts provide heterogeneous views and do not reflect a full landscape of multidisciplinary perspectives on service design. Therefore, a fundamental step toward overcoming knowledge silos and leveraging the role of service design in service innovation is to identify, systematize and characterize multidisciplinary perspectives on service design.

2.2 Service innovation

Service innovation can be viewed from an assimilation, a demarcation and a synthesis perspective ( Witell et al. , 2016 ). From an assimilation point of view, early studies have identified new technology as the main driver of service innovation ( Toivonen and Tuominen, 2009 ), adapting theories and instruments developed from traditional product innovation research ( Miozzo and Soete, 2001 ). From a demarcation perspective, service innovation is understood as differing in nature and character from product innovation ( Coombs and Miles, 2000 ), involving new service-specific theories to understand and analyze service innovative solutions ( Tether, 2005 ). Finally, from a synthesis standpoint, research claims for an integrative view of assimilation and demarcation perspectives, arguing that theories on service innovation should encompass innovation in both service and manufacturing ( Gallouj and Savona, 2009 ). Witell et al. (2016) describe a synthesis perspective connected with theories and concepts from a service logic point of view ( Michel et al. , 2008 ). In this context, the focus is placed on the customer role within the value co-creation process, extending it “beyond a simple buyer–seller relationship into value constellations” ( Michel et al. , 2008 , p. 58). In this sense, service innovation can be enabled through the design of new practices and/or resources, which converge to original value propositions from the customers’ point of view ( Skålén et al. , 2015 ).

From a S-D logic perspective, service innovation can be understood as a multifaceted concept, related to multiple phenomena ( Gustafsson, Högström, Radnor, Friman, Heinonen et al. , 2016 ), such as business model innovation ( Hsieh et al. , 2013 ), social innovation ( Windrum et al. , 2016 ), public-sector innovation ( Alves, 2013 ) and institutional innovation ( Vargo et al. , 2015 ). While business innovation is usually supported at the organizational level ( Hsieh et al. , 2013 ), social innovation often involves multi-agent and multilateral networks focused on generating social value ( Windrum et al. , 2016 ), whereas institutional innovation is achieved when new rules and practices are created at an ecosystem level ( Vargo et al. , 2015 ).

Service innovation, therefore, can be enabled at the micro, meso and macro levels of service ecosystems ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ), where service design presents a key role in creating new resources and infrastructures that support new forms of value co-creation ( Wetter-Edman et al. , 2018 ; Kurtmollaiev et al. , 2018 ). The micro level is identified by interactions between dyads of actors, such as an organization and its customers ( Mahr et al. , 2013 ). The meso level refers to the value co-creation context inside service networks ( Akaka et al. , 2012 ). Finally, the macro level is characterized by the context of institutions, rules (often tacit and implicit) and common knowledge that connect actors in the micro and meso levels ( Lusch and Vargo, 2014 ; Vargo et al. , 2015 ).

Research has shown connections between service design and service innovation across these service ecosystem levels ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ) by, for example, the design of new touchpoints and the use of technology to improve customer experience at the micro level ( Bolton et al. , 2018 ; Lo, 2011 ), the conceptualization of networks of service offerings at the meso level ( Caic et al. , 2018 ; Patrício, Pinho, Teixeira and Fisk, 2018 ), as well as through making, breaking and maintaining institutions at the macro level ( Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ; Kurtmollaiev et al. , 2018 ) and shaping mental models ( Vink et al. , 2019 ) at the macro level. However, it is still not clear how multidisciplinary perspectives contribute to service design to foster service innovation across these multiple levels. As such, comprehending the core multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design can enhance the use of this approach to enable service innovation, improving the connections between service design and service innovation research ( Antons and Breidbach, 2018 ). This endeavor is key for service researchers and practitioners to better understand the potential of service design in enabling multiple forms of resource integration within service ecosystems ( Lusch and Nambisan, 2015 ).

3. Methodology

In order to tackle these challenges, the aims of this study were twofold: identify, characterize and systematize the core multidisciplinary perspectives on service design; and provide an integrative examination of how these perspectives contribute to service design, supporting it as a service innovation approach.

Due to the dispersed nature of multidisciplinary contributions to service design in terms of publication outlets (journal articles, conference proceedings, books, etc.), a systematic literature review ( Booth et al. , 2012 ) would not alone provide a comprehensive overview of the relevant scholarship. Furthermore, considering the wide variety of fields that offer contributions to service design, this study focused on the core disciplinary areas connected to service design. For this reason, the research involved two stages of expert-based literature review and a qualitative study with focus groups, developed in three stages, as presented in the Table I .

The phases of the research process are detailed in the following sub-sections.

3.1 Phase 1

The first phase involved a literature review on service design. The selection of publications for this preliminary literature review was based on references selected by the multidisciplinary research team. The sample criterion was the relevance of the publication for service design, in terms of concepts, processes and approaches (e.g. service system, design thinking and service prototyping). After this selection, the content of the references was analyzed in order to identify their associated disciplinary areas. The results of this analysis are presented in Appendix 1.

As the name implies, service design builds on multidisciplinary contributions from service research and design research ( Patrício, Gustafsson and Fisk, 2018 ). Therefore, literature review covered these two research areas, revealing they provide the foundations of service design. A more in-depth examination on the service research stream of literature revealed other areas also contributing to service design, namely, marketing, operations management and information systems. The analysis of literature coming from a design stream also revealed a significant body of publications connecting interaction design to service design. Based on this first round of literature review of multidisciplinary perspectives, six core areas were identified as contributors to service design: service research and design research, as the key research umbrellas to service design, and marketing, operations management, information systems and interaction design as specific research areas connected to these two main streams of literature. The description of each area’s perspective is presented in Section 4.1.

3.2 Phase 2

Building upon this identification of the six areas, the second stage involved a qualitative approach ( Gioia et al. , 2012 ) based on an expert-based literature review, focused on gaining an in-depth understanding of these contributions. This phase was based on the recommendations of 13 leading international researchers in service design from research centers in nine countries in Europe, North America, South America and Asia, as presented in Table AII . These experts were selected based on their leading research roles in the six identified areas, ensuring the selection of a minimum of two experts from each area. Each expert was invited by e-mail to participate in the study by suggesting 10–15 articles that, from his or her field’s perspective, represented the most relevant contributions to service design. In this context, some of these articles may not explicitly address service design as such, but from the experts’ perspectives they developed concepts and approaches that make valuable contributions to this field. The experts’ responses resulted in a set of 135 unique references covering a rich variety of multidisciplinary contributions to service design, including 90 journal articles, 13 conference papers, 30 book chapters and 2 publications from other sources. The total of references per area suggested by the experts are: service research (30), design (37), marketing (17), operations management (18), information systems (26) and interaction design (25).

These articles were analyzed with a qualitative approach that aimed to integrate the information that emerged from the data analysis and establish connections with theory to build robust results. This involved two types of coding – initial and focused coding – using NVivo software. Within this process, fragments of data like segments of text were first coded close to their analytical import (initial coding), and then finally condensed, integrated and synthesized into more meaningful categories (focused coding) ( Charmaz, 2014 ).

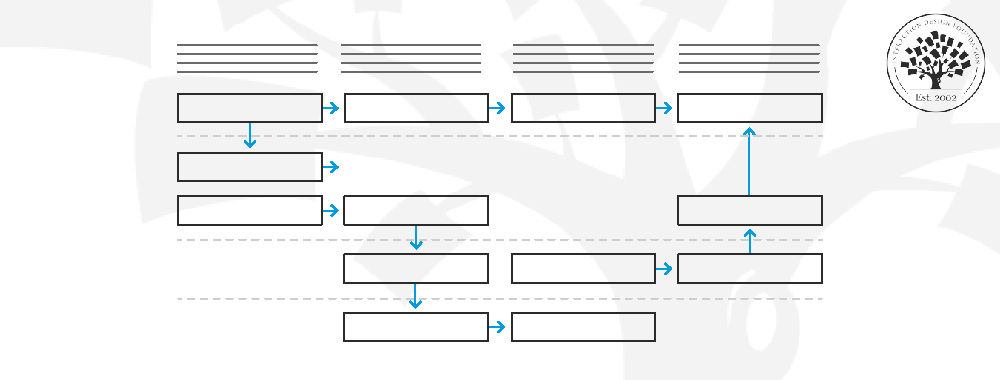

The results of data analysis were then structured into a conceptual model composed by four main categories (goals, objects, approaches and outcomes). This conceptual model was framed adopting the activity theory framework ( Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ; Wertsch, 1979 ) and, therefore, examining service design as an activity (see Section 4.2.1).

3.3 Phase 3

Building upon the results of the previous phases, the third stage involved focus group ( Krueger and Casey, 2015 ) with six research centers with leading roles in the identified areas ( Table AIII ), in five different countries. The aims of the focus groups were to provide feedback on the results of the previous stages and to further explore how multidisciplinary perspectives contribute to advance service design as an approach to service innovation. Each local facilitator invited expert researchers from his/her network to the focus group, resulting in a total of 40 participants. Data were audio-recorded, transcribed and qualitatively analyzed, as described in the Results section.

This section presents the identification, systematization and characterization of the core multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design. It starts with the six core areas contributing to service design that were identified in the first stage of research, followed by an in-depth examination of these contributions that resulted from the expert-based literature review and the focus groups.

4.1 Phase 1: identification of core multidisciplinary perspectives on service design

The first stage of literature review enabled the identification of six core areas contributing to service design: service research, design, marketing, operations management, information systems and interaction design. The analysis of this first set of literature showed that service research perspective provides the focus and context to service design, bringing definitions such as the concept of service as the application of the competences of one entity for the benefit of another entity ( Vargo and Lusch, 2008 ), the service concept ( Edvardsson et al. , 2000 ) or value propositions ( Frow et al. , 2014 ) that enable value co-creation. Service research also highlights the central role of service systems, which involve a set of inter-related structures that support and enable value co-creation among actors ( Edvardsson et al. , 2012 ). A design perspective instead provides the mindset, processes and tools that offer a holistic, iterative approach to creating new services. The literature review in the design research sphere revealed the coexistence of an exploratory inquire perspective to creating new services and a more rational problem-solving approach that is closer to engineering design ( Kimbell, 2011 ). This design perspective contributes to understanding and visualizing user experiences ( Blomkvist and Segelström, 2014 ), and offers collaborative design practices and participatory design principles ( Holmlid, 2007 ).

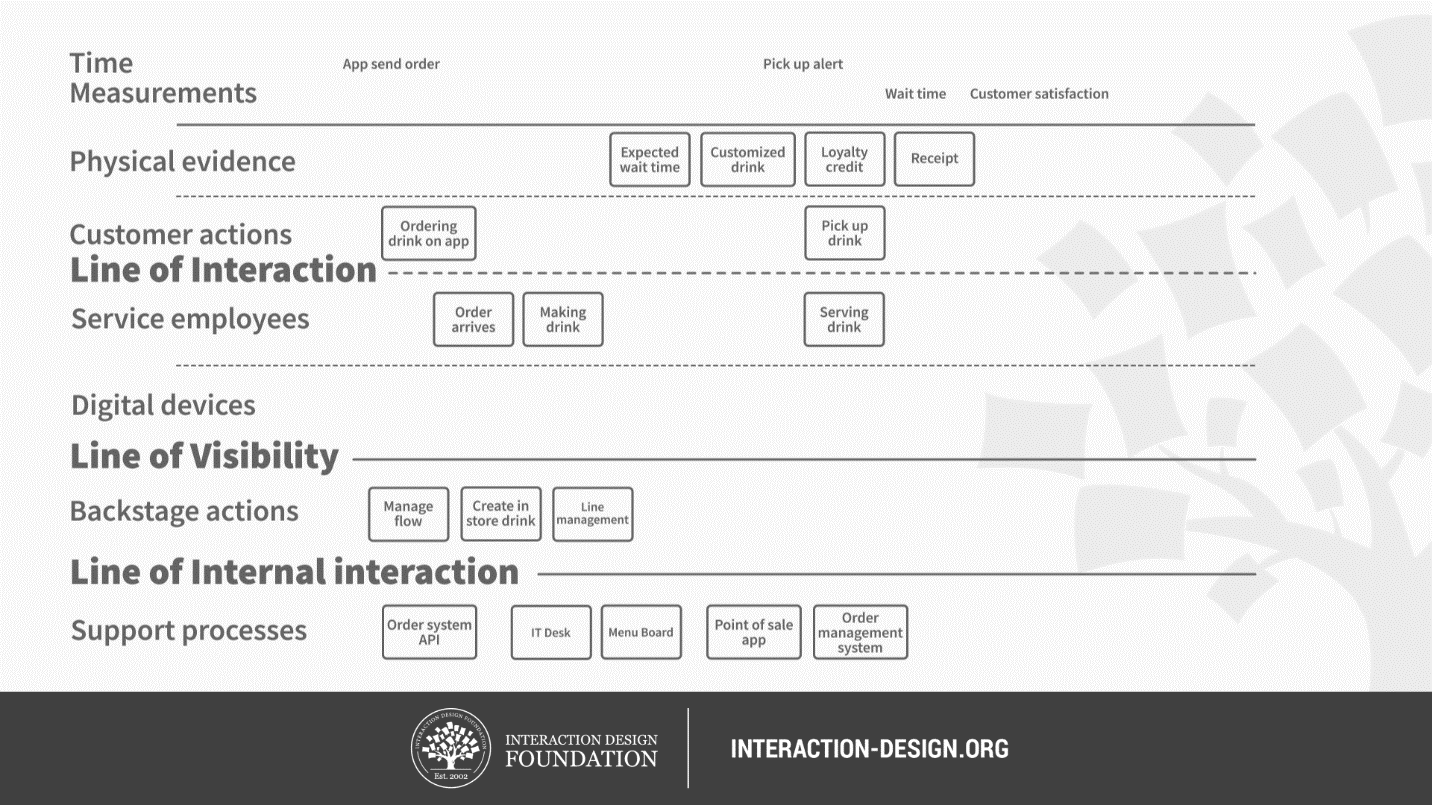

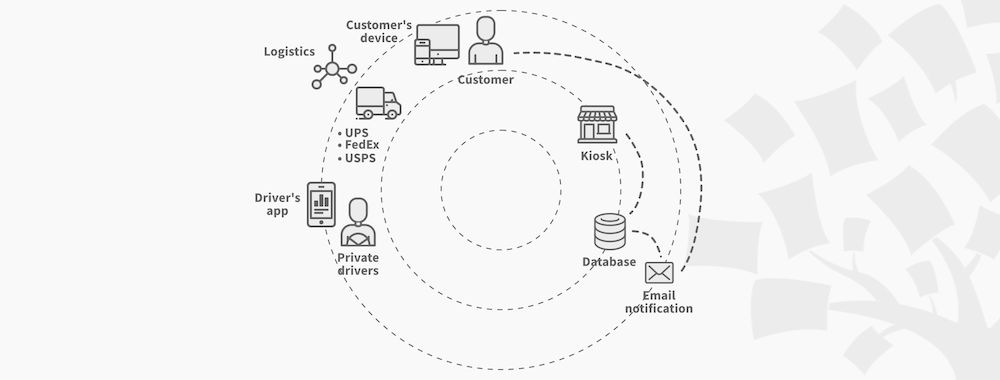

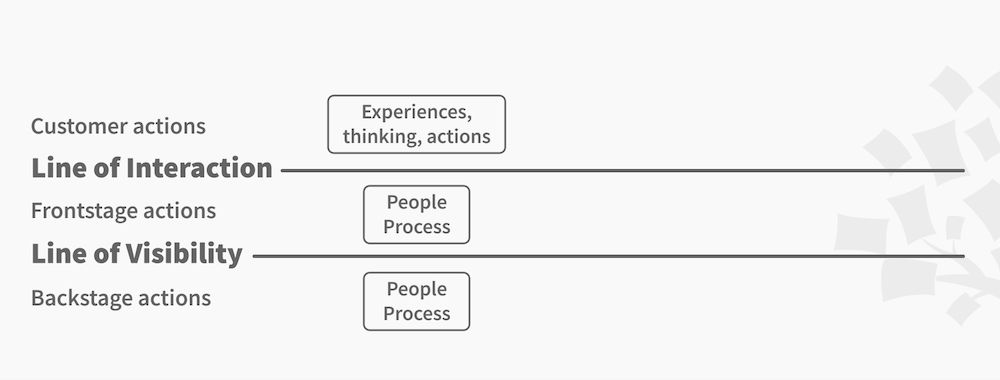

A service marketing perspective addresses the design of service concepts and multi-interface service systems focused on the customer experience, with techniques and concepts such as service blueprinting ( Bitner et al. , 2008 ) and service clues ( Berry et al. , 2002 ). An operations management perspective focuses on designing service processes, making the connection between service in the front and back stages through models such as the process chain network ( Sampson, 2012 ). Some service literature connected to information systems also addresses the technological and back-office processes that support person-to-person, person-to-machine and machine-to-machine interactions ( Glushko, 2010 ). Finally, literature review identified an interaction design perspective as one of the pioneering influences on service design ( Pacenti and Sangiorgi, 2010 ), contributing to design service interfaces for the user experience with tools such as storyboarding ( Truong et al. , 2006 ) and experience prototyping ( Buchenau and Suri, 2000 ). These six areas contributing to service design served as the basis for the subsequent research stages.

4.2 Phases 2 and 3: multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design

The qualitative analysis of the 135 references recommended by the 13 experts in the second stage and the focus groups from the third stage enabled an understanding of service design as an activity ( Wertsch, 1979 ; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ) that can incorporate multidisciplinary contributions. The following sub-sections present the conceptual model that resulted from data analysis through an activity theory lens, with the description of the goals, objects, approaches and outcomes of core multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design.

4.2.1 Service design conceptual model

The iterative process of the research Phases 2 and 3 enabled the development of a conceptual model, which was used to characterize core multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design. This conceptual model examines service design as an activity ( Wertsch, 1979 ; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ). According to activity theory, an activity is composed of a sequence of steps, defined as actions that are guided by goals ( Wertsch, 1979 ). Kaptelinin and Nardi (2012 , p. 30) define a goal as “what directs the activity” being developed by a subject, who can be a person or a group of people. Objects, on the other hand, “motivate and direct activities, around them activities are coordinated, and in them activities are crystallized when the activities are complete” ( Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 , p. 29). Kaptelinin and Nardi (2012) also describe approaches as the mediational means that intermediate the subject-object interaction. Finally, the outcome of the activity system is described as “a transformation of the object produced by the activity in question into an intended result, which can be utilized by other activity systems” ( Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 , p. 34). The conceptual model that resulted from examining service design through activity theory is presented in Figure 1 , being composed by goals (designing for), objects (focus of design), approaches (designing through) and outcomes (intended or emergent changes that can be viewed as innovations).

This conceptual model was used for a more detailed data analysis of the multidisciplinary contributions to service design. This resulted in a structure of sub-categories within goals, objects, approaches and outcomes, which were used to characterize each perspective, as presented in Tables II–VI in the following sub-sections. These tables present indirect quotations (collected during Phase 2 of the Methodology) which illustrate distinctive aspects of how each multidisciplinary perspective contribute to service design, according to the results.

4.2.2 Goals

As presented in Table II , results indicate designing for enhancing customer experience, strategic value co-creation and supporting service as the main goals shared by all the areas. Likewise, designing for improving service quality is cited by service research, marketing, operations and information systems perspectives as a relevant goal for service design.

A service research perspective demonstrates a focus on enhancing customer experience by developing theory and conceptual frameworks that explore, for instance, “emotional responses as mediating factors between the physical and relational elements and loyalty behaviors” ( Pullman and Gross, 2004 , p. 551). Along with service research, marketing literature has a strong focus on designing for enhancing customer experience. The literature notes, for instance, the planning of dramatic structures for service events, coupling back-stage employees with front-stage processes, which provide customized service ( Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010 ). Literature analysis shows service research and marketing also devoting attention to designing for supporting service and improving service quality, through the design and rigorous analysis of service delivery systems to identify problems before they happen ( Bitner et al. , 2008 ; Shostack, 1982, 1984 ).

The operations management literature analyzed, instead, offers knowledge on how to apply design to support service delivery by planning, visualizing, implementing and managing the service delivery processes that enable value co-creation within organizations and with their partners ( Sampson, 2012 ; Lovelock and Wirtz, 2016 ). Service Research Center 2 confirms that: “from an operations” perspective, we look at design at the level of the processes, so the contribution design can bring to innovation naturally appears in our literature more focused on the design of service operations. The data indicate how this area contributes to managing service capacity and creating flexible processes to deal with customer variability so as to maintain or improve operational efficiency and efficacy ( Frei, 2006 ; Sampson and Froehle, 2006 ).

Furthermore, the focus of information systems literature resulted the one of designing for supporting service delivery, for instance, by creating service-oriented architectures and web services to support business-to-business collaborations ( Chesbrough and Spohrer, 2006 ). In addition, literature from this perspective reports the use of web-based technological solutions to enhance the customer experience during service delivery processes, by increasing the power of choice of customers through a self-service approach ( Davis et al. , 2011 ).

Designing for enabling service interactions appears as a common goal in both design and interaction design perspectives. They both contribute to enabling service interactions through the application of “design methods and skills to improve the user experience” ( Meroni and Sangiorgi, 2011 , p. 9), by dealing with one-to-one, many-to-many and open-ended service relations within and among organizations ( Sangiorgi, 2009 ). In addition, the results describe these areas as contributing to improving the service design process, by creating and exploring the use of tools and techniques to visualize and analyze the user experience ( Miettinen and Koivisto, 2009 ), as well as by researching and facilitating co-design activities, where the user plays “a large role in knowledge development, idea generation and concept development” ( Sanders and Stappers, 2008 , p. 8).

Finally, results also show that a design perspective is turning the focus of service design toward improving societal well-being. This is reported in the literature as the active participation of designers in local communities, contributing with “specific design knowledge [like] design skills, capabilities and sensitivities” able to support new service models and social innovation ( Jégou and Manzini, 2008 , p. 41). Social innovation is here described as the “changes in the way individuals or communities act to solve a problem or to generate new opportunities” ( Jégou and Manzini, 2008 , p. 29).

4.2.3 Objects

As shown in Table III , results indicate service system, service interface and service concept/value proposition as service design objects in all areas. Likewise, service delivery process is cited by service research, design, marketing, operations and information systems perspectives as relevant objects for service design.

Results show that a service research perspective focuses on understanding the service interface, especially in terms of service clues ( Berry and Bendapudi, 2003 ) and servicescape ( Bitner, 1992 ). In recent years, the interest in service systems is also reported, expanding its focus from an organizational level ( Ding et al. , 2009 ; Kaltcheva and Weitz, 2006 ) to also include the study of value networks ( Akaka et al. , 2012 ) and service ecosystems ( Edvardsson and Tronvoll, 2013 ).

Along with service research, the marketing analyzed literature reports an interest in orchestrating all the “clues” of the service interface during the buying process ( Berry et al. , 2002 ). Results also show a marketing focus on service systems, for instance, by assessing value creation within the service delivery system ( Kleijnen et al. , 2007 ).

Data analysis demonstrates a design and interaction design foci on the service interface, by highlighting, for instance, the importance of “service evidence and physical cues in the servicescapes to interpret both intended and unintended relational messages that communicate the service providers’ perceptions about customers” ( Lo, 2011 , p. 05). Likewise, literature analysis suggests how a design perspective contributes to creating service systems, service concepts and service delivery processes, proposing dedicated tools as the business model canvas that “easily describe and manipulate business models to create new strategic alternatives” ( Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010 , p. 15).

An operations’ perspective focus on the service delivery process, by designing and managing all the activities and service evidences that support the service encounter ( Shostack, 1984 ; Lovelock and Wirtz, 2016 ). Data analysis shows, from an information systems’ perspective, a focus on service systems, service interface and service delivery process, such as by the application of service-oriented architecture methodologies to deploy web services that allow service system operations to be efficient and scalable ( Glushko, 2008 ).

Nevertheless, technology is a common object brought by information systems, operations and interaction design perspectives. For instance, an IT perspective describes the design of a CAD tool to evaluate and improve product–service systems ( Hara et al. , 2009 ), and an operations’ one contributes to understand how technology can change and enhance service delivery systems ( Zomerdijk and de Vries, 2007 ). Service Research Center 1, from an information systems’ background, points out that “new technology can end literally into innovation,” describing that “it is just a question of finding a new technology and a market gap and put them together to design something out of it.” In parallel, an interaction design perspective places its focus on understanding interactions between technological solutions (e.g. robots and cell phone app) and their users ( Lee et al. , 2010 ).

Finally, results also show that design and interaction design perspectives bring a focus on improving the service design process, such as by creating new service design approaches, methods and tools. Literature reports, for instance, these areas exploring the use of tools and techniques to make future service situations tangible (as through role play, desktop walkthrough, prototyping), in order to facilitate the involvement and analysis of user experience ( Steen et al. , 2011 ; Blomkvist, 2015 ). This literature on the service design process is quite different from the literature on the service delivery process. Although the first focuses on developing new approaches, models and tools to improve the process of service design, the latter focuses on using service design to improve the process of service delivery.

4.2.4 Approaches

Results indicate that service design approaches can be characterized by their customer-centered and systemic approach in all areas, as summarized in Tables IV and V .

Literature analysis in service research introduces both customer- and employee-centered foci to service design by describing, for instance, an integrated view of the organizational service delivery system, including the roles of service providers and customers ( Bitner et al. , 2008 ). Service researchers acknowledge both NSD ( Edvardsson and Olsson, 1996 ) and design thinking ( Dorst, 2011 ) as two approaches to designing for service.

Human, customer and user centeredness are associated with a design perspective, by employing Design Thinking and Participatory Design approaches that “use visual methods to explore and generate ideas” ( Kimbell, 2011 , p. 42). In this context, literature describes design for social innovation as an approach employed by designers to “recognize and support solutions developed autonomously by groups of people to solve their own problems in their local contexts” ( Cipolla and Bartholo, 2014 , p. 87).

A marketing perspective, on the other hand, brings a strong customer orientation to service design, defined as “the set of beliefs that puts the customer’s interest first” ( Deshpande et al. , 1993 , p. 27). Data analysis reflects also an interest in a systemic approach, for instance, by using service system as a theoretical construct to understand “configurations of people, technology, and value propositions” ( Mahr et al. , 2013 , p. 437). The analyzed marketing literature describes experience design as an approach to create emotional connections with customers through the careful planning of tangible and intangible service elements ( Berry et al. , 2002 ).

Literature analysis from an operations’ perspective refers to both customer and employee-centered foci to service design, by presenting studies that systematically manage the flow of resources along the service delivery system, in order to guarantee that operations in the back and front stages occur as planned ( Zomerdijk and de Vries, 2007 ). In this sense, results show that this perspective contributes with systemic and procedural approaches to service design, with tools such as blueprint, flowcharts and diagrams to visually represent the flow of resources along the service operation, facilitating decision making during service projects ( Shostack, 1984 ; Sampson, 2012 ).

An information systems’ perspective refers to customer, user and employee-centered views on service design. Service Research Center 1 also reported a technology-centered approach associated with this area, which is interested in the “design of the service where two machines are interacting to each other […] focusing primarily on the technology and how to design what works best for these two machines.” Results refer to a systemic process, using service system as an abstraction to understand value co-creation ( Spohrer and Kwan, 2009 ) and an experience design approach to improve the usability of service interfaces ( Constantine and Lockwood, 2001 ).

Interaction design literature characterizes a mostly user-centered approach, illustrated by the claim that “the main and distinctive focus of service design tools concerns the design, description and visualization of the user experience, including the potentials of different interaction modes, paths and choices” ( Maffei et al. , 2005 , p. 6). Participatory design and co-creation are also associated approaches with design and interaction design, while a systemic approach is highlighted by the interest in understanding and contextualizing interactions within user systems ( Sangiorgi, 2009 ).

4.2.5 Outcomes

Data analysis enabled the identification of service design outcomes which can be positioned at different levels of service ecosystems ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ). This positioning is not rigid as service design may simultaneously impact at distinct service ecosystem levels simultaneously, and value co-creation is a dynamic process, which changes according to the context ( Edvardsson and Tronvoll, 2013 ). Nevertheless, the organization of the service design outcomes across the micro, meso and macro levels of service ecosystems ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ) was useful to reflect the analyzed literature main foci and facilitate the interpretation of results. In this sense, if the literature under analysis focused more on service design outcomes based on dyadic interactions between users and service providers, as well as more specific organizational service processes, it was categorized at the micro level. On the other hand, if it described service design outcomes based on many-to-many interactions or value propositions in the value network, then it was considered as having a meso focus. Finally, if service design outcomes were identified as connected to institutional change, then this literature was characterized as having an impact on the macro level ( Lusch and Vargo, 2014 ). These service design outcomes are presented in Table VI .

As shown in Table VI , at a micro level of service ecosystems, all perspectives are reported to bring knowledge that support changing the service encounter, in terms of new service clues and servicescape ( Bitner, 1992 ), new service interfaces ( Secomandi and Snelders, 2011 ), new brand-related stimuli ( Brakus et al. , 2009 ), new service evidences ( Shostack, 1982 ), new user interfaces ( Glushko, 2010 ) and new configurations of people, products and information that support the user experience ( Sangiorgi, 2009 ). Operations management and information systems are the perspectives that mostly contribute to designing new service delivery processes, by reducing variability in service operations ( Frei, 2006 ) and using technology to increase service performance ( Schmenner, 2004 ). Moreover, both these areas and interaction design show a focus on supporting service design to designing new technology ( Hara et al. , 2009 ) to improve service operations ( Roth and Menor, 2003 ) and to innovate service interactions ( Zimmerman et al. , 2011 ). A marketing perspective also contributes to create new service clues that integrate the service encounter ( Berry et al. , 2002 ).

At a meso level of service ecosystems, operations management and information systems’ perspectives are reported to support service design to conceptualize new service delivery processes within supply chains ( Sampson, 2012 ) and leverage technology to enable new interactions that support service network change ( Davis et al. , 2011 ; Von Ahn and Dabbish, 2008 ). Moreover, a design perspective brings a social innovation orientation to service design ( Jégou and Manzini, 2008 ), through the creation of service platforms that support new value co-creation interactions between actors, strengthening novel social and economic networks ( Baek et al. , 2015 ). Service Research Center 6 highlights, for instance, that “in projects, such as Nutrire Milano, designers have created platforms to support new forms of interactions between actors enabling social innovation inside communities.”

At a macro level of service ecosystems, a design perspective contributes to enable institutional change, by envisioning new services ecosystems that support more sustainable lifestyles and consumption habits (e.g. distributed power generation systems, programs of urban and regional development) ( Manzini, 2009 ), as well as new service concepts that change citizens’ practices and routines ( Manzini and Staszowski, 2013 ; Cipolla et al. , 2015 ). On the other hand, a service research stream offers expertise that supports service design to understand and enable institutional change, through the questioning of existing socially constructed systems of norms, values and definitions, as well as by reconfiguring novel service ecosystems based on new practices and beliefs ( Vargo et al. , 2015 ; Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ). Service Research Center 4, from a service research perspective, argues that “service design can be really part of questioning, breaking institutions, creating prerequisites for new ones, new behaviors, new practices and new norms.”

5. Discussion

After identifying, characterizing and systematizing the core multidisciplinary perspectives on service design in terms of goals, objects, approaches and outcomes ( Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012 ), this section provides an integrative examination of the research and managerial implications that these multiple contributions bring to service design.

5.1 Research implications

This paper builds a multidisciplinary perspective to service design sustained by the systematization of multiple contributions that service research, design, marketing, operations, information systems and interaction design bring to this approach. By focusing on the relations between these multiple perspectives, it is possible to identify cross-cutting research areas and complementarities, which are discussed in the following sub-sections.

5.1.1 Building a shared ground with cross-cutting research areas

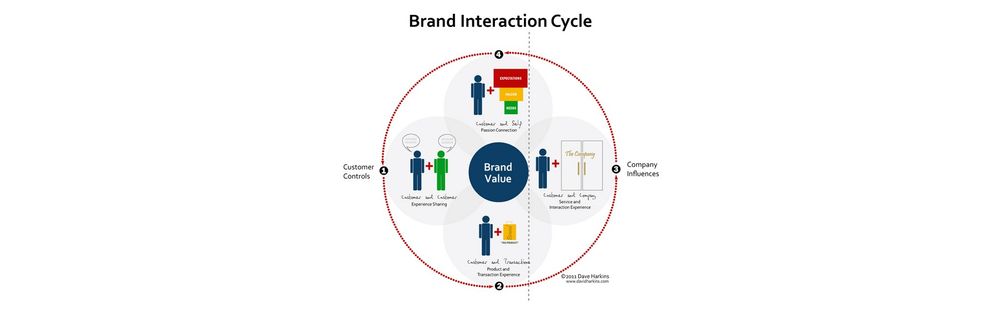

The cross-cutting research areas show that there is a common ground that can build the foundations to strengthen service design as a multidisciplinary activity to service innovation. These shared concerns are represented by the convergent foci that the multidisciplinary perspectives have on value co-creation, customer experience and service system, supported by a human-centered approach, which reflect on interconnected aspects of the service design activity in terms of goals, objects, approaches and outcomes.

In terms of goals, all areas contribute to design for value co-creation, enhance the customer experience and support service. Service design understanding about the customer experience, for instance, is enriched by a marketing’s expertise on designing experience-centric services ( Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010 ) and a design view on the application of approaches to conceptualize and improve the experience from a human-centered point of view ( Holmlid, 2007 ; Miettinen and Koivisto, 2009 ). This is also reflected on the employment of web-based solutions to enhance value co-creation with users, from an information systems standpoint ( Davis et al. , 2011 ).

Regarding the cross-cutting objects, all areas refer to service system as an integrative abstraction, focusing on its different components, namely the value proposition, the service interface and the service delivery process. Value propositions, for instance, are approached in different ways from a design, a service research, a marketing and an information systems perspective. As such, these perspectives address value propositions in the form of service offerings to social and economic problems ( Burns et al. , 2006 ), as new modes of value co-creation within service networks ( Akaka et al. , 2012 ) and as new service solutions supported by online systems to increase operations’ efficiency ( Chesbrough and Spohrer, 2006 ), respectively.

Regarding service design approaches, the cross-cutting area is the human-centricity, with each perspective focusing on designing solutions for the various roles people can assume within service systems. From a user-centered point of view, service design can integrate users’ needs and design for user experiences ( Segelström, 2009 ; Glushko, 2008 ), integrating design, information systems and interaction design perspectives. Through a customer-centered standpoint supported by all areas, service design turns the attention to understanding customers’ desires and cultures, as well as to stimulating new customers’ roles ( Zomerdijk and de Vries, 2007 ). Finally, service research, marketing, operations and information systems bring attention to an employee perspective, which contribute to understand and design employees’ roles in the service delivery system, as well as use employees’ knowledge as sources of customer experience innovation ( Bitner et al. , 2008 ; Shostack, 1984 ).

In terms of service design outcomes, the cross-cutting areas result from the objects’ transformations and, therefore, are similar to the service design objects. As such, cross-cutting outcomes are the service encounter, the service delivery process and the value proposition changes, which converge to innovate service networks. In this integration of multidisciplinary perspectives, service designers can profit, for instance, from a design view to create new service models based on social innovation initiatives ( Jégou and Manzini, 2008 ), from an information systems contribution to integrate networked peer-to-peer collaborations ( IfM and IBM, 2007 ), or even from an operations’ perspective to implement new service delivery systems ( Roth and Menor, 2003 ).

5.1.2 Complementarities that support a service design holistic approach

The study results show the richness of contributions that multiple perspectives can bring to service design, making service design a multidisciplinary field able to get a broad and holistic understanding of service related challenges. These multiple areas also provide complementary perspectives, which taken together support the foundations for an actual holistic service design approach that could not be achieved by each perspective by itself. The systematization of these multiple perspectives enhances the dialog and shared ground among service designers coming from different backgrounds, elucidating the connections between the various approaches and concepts of their communities of practice.

A service research perspective informs service designers with the conceptual frameworks to understand, analyze and design new forms of value co-creation within service systems ( Edvardsson and Tronvoll, 2013 ). Complementary to this perspective, a design view brings tools and methods ( Miettinen and Koivisto, 2009 ) to understand, envision and create new forms of value co-creation within socio-material configurations ( Kimbell, 2011 ). For that, designers contribute to creating service interfaces ( Secomandi and Snelders, 2011 ) and to facilitating co-design processes ( Steen et al. , 2011 ) that concretize and sustain the interactions between actors in service systems ( Wetter-Edman et al. , 2014 ).

A marketing perspective, on the other hand, brings an extensive knowledge on understanding and designing the customer experience ( Zomerdijk and Voss, 2010 ). This area’s perspective supports service designers to conceptualize customer-centric service systems ( Mahr et al. , 2013 ), for instance, by planning the tangible and intangible service elements that increase service quality ( Bitner et al. , 2008 ). An operations’ view to service design supports to build the customer experience, by creating operational strategies ( Roth and Menor, 2003 ), planning and controlling service operations ( Shostack, 1984 ) and designing the entire service delivery system, which sustain the quality of the service encounter ( Sampson, 2012 ). In parallel, an information systems view contributes to designing the technology that supports these service delivery systems to run ( Glushko and Nomorosa, 2013 ). By bringing a technology-perspective, this area increases the service delivery performance ( Schmenner, 2004 ), as well as creates new user interfaces ( Glushko, 2010 ) and designs service monitoring systems to evaluate the customer satisfaction ( Glushko and Nomorosa, 2013 ).

Nonetheless, an interaction design perspective contributes to understand and design service interactions that support the user experience ( Zimmerman et al. , 2011 ). This area’s contributions range from creating approaches that facilitate co-design activities ( Sanders and Stappers, 2008 ), to the visualization and interpretation of user journeys within service systems ( Sangiorgi, 2009 ).

5.2 Managerial implications

The identification and characterization of the goals, objects and approaches that service design multidisciplinary perspectives can deal with during service design projects demonstrate the diversity of complementary contributions this approach can bring to service innovation. Understanding these perspectives can help to articulate which kind of contribution is useful along the service innovation process ( Gustafsson, Kristensson, Schirr and Witell, 2016 ), in order to coordinate resources to create new service. For instance, if the goal is designing for supporting service with improved service operations, it may be interesting to integrate knowledge from capacity and customer variability ( Frei, 2006 ), with an understanding of how to articulate resources along the customer journey to enhance customer experience ( Truong et al. , 2006 ), from operations and interaction design areas, respectively. These perspectives can also be complemented by designing the technology that will support the service delivery system ( Glushko, 2010 ), with an information systems point of view.

This paper brings a valuable contribution to organizations which are interested in enabling diverse forms of innovation, by describing how a service design multidisciplinary approach can have a wide impact on service innovation, reflected in: new service interfaces ( Secomandi and Snelders, 2011 ), technological innovation ( Zimmerman et al. , 2011 ), new value propositions, new service networks ( Patrício, Pinho, Teixeira and Fisk, 2018 ), social innovation ( Baek et al. , 2015 ), public-sector innovation ( Manzini and Staszowski, 2013 ) and institutional innovation ( Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ). Likewise, the paper identifies approaches, such as systemic and participatory design ( Kimbell, 2011 ), experience design ( Berry et al. , 2002 ) and design thinking ( Dorst, 2011 ), which can be used by teams to coordinate the integration of resources during service design projects.

This characterization and systematization supports a better understanding of service design as an innovation practice, which can incorporate multidisciplinary perspectives to enable new forms of value co-creation ( Lusch and Nambisan, 2015 ) at different levels of service ecosystems ( Chandler and Vargo, 2011 ). In this sense, this paper clarifies which multiple contributions service management researchers and practitioners can integrate to tackle complementary levels of complexity of service projects.

Finally, the paper supports creating a common ground that enables service designers from different backgrounds to better communicate and understand each other when collaborating, which boosts the involvement of multidisciplinary teams during service design and innovation projects ( Ostrom et al. , 2015 ). Therefore, this comprehensive discussion contributes to pave the way to advance service design as an interdisciplinary field better connected to service innovation ( Gustafsson, Högström, Radnor, Friman, Heinonen et al. , 2016 ; Ostrom et al. , 2015 ; Patrício, Gustafsson and Fisk, 2018 ).

6. Limitations and future research

This paper supports the understanding of service design as a multidisciplinary activity able to foster service innovation, by bringing together complementary contributions. However, in spite of the effort to systematize multidisciplinary contributions to service design, this study has limitations. First, the research process was expert based, which means that a sample of service design experts was selected, influencing the selection of suggested literature and, consequently, the results. This limitation was partially overcome by strengthening the analysis of the literature review through focus groups involving 40 researchers from 6 service research areas in 5 countries. As the service design community grows, future research could accompany its multidisciplinary evolution and its new efforts toward supporting service innovation.

Second, the research process concentrated on collecting multidisciplinary contributions from the point of view of service design scholars. Therefore, further research could focus on understanding how multidisciplinarity is dealt in the practice of service design, as well as how service designers actually enable service innovation at different levels of service ecosystems through their projects. This could be complemented by studies that investigate other areas connected to service design which were not considered in this study.

Finally, the results also indicate emerging research areas that are not yet shared by all perspectives. One of these emerging research topics that seem especially important is the connection between service design and service ecosystem. Currently, this research area is mainly supported by design ( Burns et al. , 2006 ; Sangiorgi, 2011 ) and service research ( Vargo et al. , 2015 ; Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ). From a design perspective, service design brings a transformational approach ( Burns et al. , 2006 ; Sangiorgi, 2011 ), focused on enabling society-driven innovation, by addressing social challenges and creating solutions that support more sustainable service ecosystems ( Baek et al. , 2015 ). In this sense, service design can be used not just as an approach to innovate dyadic relations between customers and service providers, but a process for radical change through the envisioning and design of new service systems ( Burns et al. , 2006 ; Manzini, 2009 ). More recently, a design perspective has also been developed to support the connection between service design and institutions, claiming that changes at the micro level are critical to catalyze institutional change at the macro level of service ecosystems ( Wetter-Edman et al. , 2018 ). Therefore, in terms of social innovation outcomes it is possible to notice that the distinction between meso and macro levels of service ecosystems is getting increasingly blurred, since the efforts on fostering socially innovative service networks ( Baek et al. , 2015 ) and stimulating institutional change ( Cipolla et al. , 2015 ) are inter-related.

From a service research perspective, the emerging concern about service ecosystems focuses on social structures ( Edvardsson and Tronvoll, 2013 ) and on breaking down existing institutional arrangements, reconfiguring new service ecosystems based on novel practices and beliefs ( Koskela-Huotari et al. , 2016 ). Public policies can also consolidate institutional change and shape the macro level of service ecosystem, as highlighted by Trischler and Charles (2019) , since they coordinate the collective, multi-actor and systemic phenomenon of value co-creation between actors. Therefore, understanding users and their value co-creation processes are key to public policy design, in order to identify the most suitable configuration of resources to integrate and support emergent solutions within service ecosystems ( Trischler and Charles, 2019 ). Building on this emerging area, further research is needed to explore the connections between service design and service ecosystems, by bringing supportive knowledge from other research perspectives beyond service research and design.

Service design activity conceptual model

Research process and summary of findings

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Literature review | Systematic literature review based on experts’ suggestions | Focus groups |

| Sample design | References identified by multidisciplinary research team | References identified by 13 international leading service design researchers from 9 countries in Europe, North America, South America and Asia (covering the 6 core service design areas, at least 2 per research area) | 6 service design research groups that represent the identified areas in Phase 1, in Sweden (2), Portugal (1), Germany (1), Netherlands (1) and Italy (1) |

| Data collection | Selection of 40 references that represent multidisciplinary contributions to service design | 10–15 articles that from the experts’ perspectives represent the most relevant contributions to service design, resulting in a total of 135 references | Audio recording and literal transcription of focus group interviews with a total of 40 participants |

| Data analysis | Qualitative data analysis based on the articles’ content | Qualitative data analysis supported by data coding on the NVivo software | Qualitative data analysis of interviews’ transcriptions |

| Results | Identification of 6 core areas that contribute to service design: service research, design, marketing, operations management, information systems and interaction design | Characterization of the multidisciplinary perspectives and their contributions to service design, in terms of an activity (with goals, objects, approaches and outcomes) | Refinement and validation of results from Phase 2 and interpretation of how multidisciplinary perspectives contribute to advance service design as an approach to service innovation |

Service design multidisciplinary goals

| Goals | Definition | Service research | Design | Marketing | Operations management | Information systems | Interaction design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designing for enhancing customer experience | Designing the contextual elements ( , 2008) and the service performance ( ) to enable an experience | Creating conceptual frameworks to understand customer experience ( ) | Applying design methods and skills to improve the customer experience ( ) | Planning of dramatic structures for service events ( ) | Dealing with customer variability so as to improve service operations ( ) | Use of web-based solutions to enhance the customer experience ( , 2011) | Using modeling techniques to conceptualize customer experience ( ) |

| Designing for strategic value co-creation | Designing service concepts, value propositions and strategies to enable value co-creation ( , 2011; , 2014) | Creating new service offerings ( , 2011) | Creating new kinds of value relation between diverse actors within a socio-material configuration ( ) | Conceptualizing customer-centric service systems ( , 2013) | Creating operational strategies for multichannel service delivery systems ( ) | Designing automated service systems ( ) | Designing interactional strategies between technological solutions and their users ( , 2010) |

| Designing for supporting service | Designing for operationalizing the value proposition ( ) | Exploring service systems and service delivery processes connected to organizations ( ) | Designing service systems that meet users’ needs ( , 2011) | Analyzing service delivery process and improving service quality ( , 2008) | Planning, visualizing and implementing service delivery processes ( ) | Creating service-oriented architectures to support business-to-business collaborations ( ) | Designing service interactions to support customer experience ( , 2011) |

| Designing for improving service quality | Designing for guaranteeing service quality in terms of service efficiency and efficacy. ( ) | Improving customer experience as a means of attaining service quality ( , 2009) | – | Systematically measuring and rewarding customer-centric behavior in front-line personnel ( ) | Rigorously analyzing and controlling of service operations ( ) | Designing service monitoring systems to evaluate customer satisfaction ( ) | – |

| Designing for enabling service interactions | Designing for intermediating service encounters between actors. ( , 2011) | – | Designing service interfaces ( ) | – | – | – | Designing service interactions within and among organizations ( ) |

| Designing for improving societal well-being | Designing for public and societal value, achieved through service that involves a large set of stakeholders. ( , 2006; ) | – | Supporting new service models and social innovation initiatives within communities ( ) | – | – | – | – |

| Designing for improving service design process | Contributing to better develop the process of designing service as through researching the benefits of co-design, design tools and service representations. ( ; ; ) | – | Creating and exploring the use of tools and techniques to visualize and analyze the user experience ( ) | Using service theater to design and execute memorable service experiences ( ) | – | – | Facilitating co-design activities ( ) |

Service design multidisciplinary objects

| Objects | Definition | Service research | Design | Marketing | Operations management | Information systems | Interaction design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service system | A set of inter-related structures that support and enable value co-creation among actors ( , 2012) | Social structures in service systems are key to understand and enhance value co-creation ( ) | Socio-technical systems ( ) | Customer-oriented experience systems ( , 2013) | Back-office and front-office of service delivery systems ( ) | Service system is a basic theoretical construct in service science ( ) | Service interactions cannot be separated from the overall service system ( ) |

| Service interface | Service interface includes material artifacts, environments, embodied human interactions, diffuse phenomena appealing to the senses (as the tastes, smells, sounds) and all the service evidences that intermediate service encounters. ( ) | Service clues and servicescape ( ) | Materiality of service interface ( ) | Conceptualizing brand experience as sensations, feelings, cognitions, and behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli ( , 2009) | Service evidences ( ) | User interfaces ( ) | Service interface is made up of people, products, information and environments that support the user experience ( ) |

| Service concept/value proposition | Set of potential benefits offered to customers and/or other stakeholders. ( , 2011; , 2014) | Value propositions ( , 2014) | Service offerings that address social and economic problems ( , 2006) | New forms of value co-creation within service networks ( , 2012) | Service concept defines the how and the what of service design ( , 2002) | New service offerings supported by online tracking systems to increase operations efficiency. ( ) | Service as a mean for new forms of interactions between stakeholders ( , 2011) |

| Service delivery process | Process of applying specialized competences (knowledge and skills) to enable service among actors. ( , 2009) | New forms of value co-creation throughout the service delivery process ( , 2011) | Design of customer journeys ( , 2011) | Design of employees’ roles as key supporters of customer experience in the service delivery system ( , 2008) | Design of service operations ( ) | Design of information-intensive service delivery processes ( ) | – |

| Technology | All the IT artifacts/systems used to enable the service and/or the service design process. ( , 2009; ) | – | – | – | Technology that supports the service delivery system ( ) | Systems of human-ware, hardware and software in services ( , 2009) | Crowd-sourcing social computing systems to support service ( , 2011) |

| Service design process | Process to create new service or improve existing one. ( ) | – | Use of co-design to support engagement of stakeholders ( , 2011) | Use of aesthetic design to appeal to the human senses and create meaning for service ( ) | – | – | Using of prototyping as external representations ( ) |

Service design multidisciplinary approaches – centeredness

| Approaches | Definition | Service research | Design | Marketing | Operations management | Information systems | Interaction design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer centered | A customer-centered approach seeks to analyze people in the context of consumption, understanding service through customers’ perspective, in order to satisfy customer needs and wants, therefore, improving customer experience. ( ) | Customer as a co-creator of value ( ) | Solving customer problems and satisfying customer needs with new value propositions ( ) | Strong customer orientation to service design ( , 1993) | Systematically managing the flow of human resources along the service delivery system ( ) | Supporting interactions with customers with web-based service ( , 2011) | Focus on designing and describing potential interactions modes and paths of customers ( , 2005) |

| Employee centered | An employee-centered approach highlights employees’ participation during service, by designing their roles within the service delivery system, training and giving them the conditions (e.g. physical space; scripts) so they can better perform their work. ( ; , 2002; ) | Involve users and front-line workers in the design process ( , 2006) | – | An integrated view of the organizational service delivery system, including the roles of employees and customers ( , 2008) | Systematically processing customers along the service delivery system ( ) | Technology in itself does not create world class service organizations. Recruiting, training and retaining educated employees are also prerequisites for success. ( , 2011) | – |

| User centered | An user-centered approach seeks to see and analyze people in the context of usage, in order to understand users’ experiences in their own terms. ( ; , 2011) | – | Focus on understanding and engaging users in co-design activities ( ) | – | – | User-centered design emphasizes issues about the usability of the service ( ) | Visualization of user research ( ) |

| Human centered | A human-centered design approach consists of the capacity and methods to investigate understand and engage with people’s experiences, interactions and practices as well as their values and dreams. ( ) | – | Focus on understanding human beings as active agents of their contexts. ( ) | – | – | – | Focus on humans as resources to “infrastructuring” design endeavors. ( , 2012) |

Service design multidisciplinary approaches – process

| Approaches | Definition | Service research | Design | Marketing | Operations management | Information systems | Interaction design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic approach | Approach to understand and analyze phenomena not in an isolated way, but in relation with contextual elements and their inter-relations. ( ) | Integrating physical environment improvements with organizational and operational changes ( , 2010) | Understanding business organizational structures, processes, and related systems ( ) | Using service system as a theoretical construct to understand configurations of actors and resources ( , 2013) | Visually representing the flow of resources along service operations ( ) | Using service system as an abstraction to understand value co-creation ( ) | Understanding and contextualizing interactions within user systems ( ) |

| Experience design | An approach to create emotional connection with customers through careful planning of tangible and intangible service elements. ( , p. 551) | – | – | Creating emotional connections with customers through the careful planning of tangible and intangible service elements ( , 2002) | – | Experience design approach to improve the usability of service interfaces ( ) | Designing game-like interactions to increase enjoyment and engagement with software ( ) |

| Participatory design or other co-creation practices | An approach that seeks to actively involve stakeholders (e.g. employees, partners, customers, citizens, end users) in the design process to help ensure results meet their needs. ( ) | – | Designer is not only a facilitator but rather a co-actor within a co-design process ( ) | Use of co-creation workshops ( , 2013) | – | – | Design process s laid out to support users’ interests, and the services designed are to be supportive of these interests as well ( , 2012) |

| Design thinking | Application of the design ability ( ) – deal with ill-defined problems, solution-focused strategy, abductive thinking, visual ways of communication, constructivist thinking-, which may be represented in the form of an iterative method of exploration, creation, reflection and implementation. ( ) | Developing together both the formulation of a problem and ideas for a solution, with constant iteration of analysis and synthesis, between the two notional design “spaces” – problem space and solution space ( ) | Frame problems and opportunities from a human-centered perspective, use visual methods to explore and generate ideas, and engage potential users and stakeholders ( ) | – | – | – | Systematically applying design methodology and principles ( ) |

| New service development | NSD is the overall process of developing new service offerings ( , 2000) and is concerned with the complete set of stages from idea to launch. ( , 2002, p. 122) | New Service Development as an approach to create new service ( ) | – | Understanding how customer input may be obtained in the various stages of the NSD process ( ) | Managing NSD process or performance ( , 2002) | – | – |

| Design for social innovation | Everything that expert design can do to activate, sustain, and orient processes of social change toward sustainability ( , p. 62) | – | Design for social innovation supports solutions developed autonomously by groups of people to solve their own problems ( ) | – | – | – | – |

Service design multidisciplinary outcomes

| Definitions | Service research | Design | Marketing | Operations management | Information systems | Interaction design | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service encounter change | Changes in the service encounter. e.g.: new interfaces ( ); new service delivery channels – e.g. mobile channel. ( , 2007) | New service clues and servicescape ( ) | New service interfaces ( ) | New brand-related stimuli ( , 2009) | New service evidence ( ) | New user interfaces ( ) | New configurations of people, products and information ( ) |

| Service delivery process change | New service delivery processes and operations that structure and support value co-creation ( ) | Designing new forms of value co-creation ( , 2011) | Designing new customer journeys ( , 2011) | Designing new employees roles ( , 2008) | Reducing variability in service operations ( ) | Using technology to increase service performance ( ) | Designing new service interactions ( , 2011) |

| Technological change | New technology created, or used, to improve service delivery process, the customer experience or the service design process. e.g.: personalization of technology ( ), use of new CAD systems to improve Service Design process. ( , 2009) | Studies of the impact of technologies on service ( ) | – | Assessment of value creation in mobile service delivery ( , 2007) | Using technology to improve service delivery processes efficiency ( ) | Designing web-based services to support new forms of value co-creation with users ( , 2011) | Using technology to support new forms of user interactions ( , 2011) |

| Value proposition change | New service concepts and strategies that support new value propositions ( , 2014), e.g., new electricity service concept ( , 2015) | Design of new service offerings ( , 2011) | Design of new service models based on social innovation initiatives ( ) | Conceptualizing new forms of value co-creation with customer ( , 2013) | Design of new service delivery systems ( ) | Using technology to support new service models ( ) | Design of new interactional strategies between users and robots ( , 2010) |

| Service network change | Changes in the service network ( , 2012), which involve new forms to promote multi-actors’ service that extend the dyad organization-customer ( ) | Conceptualizing new value networks ( , 2012) | Design of service platforms that strengthen novel social and economic networks ( , 2015) | Innovation of complex healthy food experiences involving many stakeholders ( , 2013) | Design of new supply chains ( ) | Creating networked peer-to-peer collaboration through internet mediated tools ( ) | Networked individuals accomplishing work online through open-source software-development projects ( ) |

| Institutional change | New ways of thinking and doing ( ) and changes in the shared institutional logics that permeate service exchanges ( ) | Questioning existing systems of norms and reconfiguring novel ones based on new practices and beliefs ( , 2016) | Envisioning new service ecosystems that support more sustainable lifestyles ( ) | – | – | – | – |

Results of Phase 1

| Publication | Main area(s) |

|---|---|

| 1. Bitner, M.J., Ostrom, A.L. and Morgan, F.N. (2008), “Service Blueprinting: a practical technique for service innovation”, , Vol. 50 No. 3, pp. 66-95. | Service research, marketing |

| 2. Beyer, H. and Holtzblatt, K. (1997), , Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, San Franscisco. | Marketing |

| 3. Blomberg, J. and Darrah, C. (2015), “Towards an anthropology of services”, , Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 171-192. | Design |

| 4. Blomkvist, J. and Segelström, F. (2014), “Benefits of external representations in service design: a distributed cognition perspective”, , Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 331-346. | Design, interaction design |

| 5. Brown, T. (2008), “Design thinking”, , Vol. 86 No. 6, pp. 84-94. | Design |

| 6. Buchenau, M. and Suri, J.F. (2000), “Experience prototyping”, , ACM Press, pp. 424-433. | Interaction design |

| 7. Burns, C., Cottam, H., Vanstone, C. and Winhall, J. (2006), , Design Council, London. | Design |

| 8. Carbone, L.P. and Haeckel, S.H. (1994), “Engineering customer experiences”, , Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 8–19. | Marketing |

| 9. Dubberly, H. and Evenson, S. (2008), “On modeling: the analysis-systhesis bridge model”, , Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 57-61. | Interaction design |