Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Treated without Medication – John

Severe OCD since 4th Grade

John was a very bright young fellow who was heading off to an Ivy League university in the fall. He was suffering from very severe OCD since 4th grade. He had tried Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, however it didn’t help. He refused exposure and response prevention therapy. Eventually, his OCD became so severe that he refused to extend his elbow because of his belief that such an action would cause harm to someone he loved. He also refused medication.

Headaches, GI Problems, and Weight Problems

His Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive scores was= 29 (obsessive=12, compulsive=17). He complained of headache, many gastrointestinal problems (nausea, diarrhea, constipation, stomach pains, flatulence, reflux, and perhaps related, and inability to gain weight, despite a well balanced and healthy diet).

Family History of OCD

John’s family history revealed OCD in his grandmother, a suicide by that grandmother’s sister, using a gun. His father was anxious, depressed and impulsive, but high functioning and successful. His father’s sister was described as very intense, persistent, and obsessive. His other grandmother was depressed and his grandfather’s father was alcoholic.

Other Health Problems

John’s physical exam revealed an obvious contracture in his right elbow, with the right hand being cyanotic and colder than the left. His skin was dry, with severe acne on his face and back. His tongue was coated white, suggestive of Candida overgrowth, and his throat was red. He had bilaterally swollen cervical lymph nodes, white spots on his nails, hyper-pigmented scars suggestive of excessive ACTH output and adrenal insufficiency. He had chronic sinusitis.

Evaluation Points to Nutrition, Digestion, Immune Systems

In summary, my initial evaluation, (a three hour history and physical and laboratory testing), suggested problems in the areas of nutrition, digestion and immune/inflammatory processes. I suspected genetic problems in his methylation.

Lab Results Show Health Issues

The laboratory evaluation showed the following: Nutrition: Low vitamin D, L-tryptophan was low, B5, B2; B12, folate, Kryptopyrolles were elevated at 40.6 (consistent with acne, immune system problems), iron was low normal, low red blood cell size ( 83). Genetic: ++MTHFR Gastrointestinal: Candidiasis, anti-gliadin antibodies, WBC’s + in stool, HLA DQ2 (Coeliac’s). Immune/Infection: 5 infections: salmonella, Endolimax Nana, Bartonella, Babesia, Candida, plus chronic sinus infections, delayed food sensitivities (IgG mediated). Hormones: TSH: 4.11, melatonin was 7.1, ACTH was 42 ([norm=7-50], cortisol output was low at 20 [23-42], DHEA low normal (4), cholesterol was 131.

Now Willing to Do Everything

John was now willing to implement all of the recommendations because he had an understanding of what was causing his problems. He was a model patient. At his first 1st visit to review his lab results in May of 2007 I recommended L-tryptophan, D, B-vitamins (per his test results), high dose L-methylfoalte, inositol, three antibiotics for infections, candidiasis as well as anti-parasitics, probiotics, and a medical food product to support healthy bacteria and strengthen the gut-immune barrier.

Sleep back on Track

At his 2nd Visit on June 23rd 2007 he reported that his GI problems were gone, and his sleep was “back on track”, however his anxiety was unchanged. I recommended exposure and response prevention therapy.

Headaches Gone, Sinuses Cleared

At his 3rd Visit on July 19th 2007 he had had exposure and response prevention therapy and he reported his anxiety was “way down”. His headaches—which he had not told me about earlier—were gone. His sinuses had cleared completely.

By August 21st of 2007, John was still on his antibiotics, and he reported that the OCD was “ a million times better”, and no longer interfering with his activities”. He later was able to do cognitive behavioral therapy with exposure and response prevention.

Free of OCD without Medication

At follow up 3 ½ years (after his father’s death) he continued to be free of OCD, however at that time he was having some anxiety, which a short course of CBT was able to address. No medications were used in his treatment.

A True Story of Living With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

An authentic and personal perspective of the internal battles within the mind..

Posted April 3, 2017

- What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

- Take our Generalized Anxiety Disorder Test

- Find a therapist to treat OCD

Contributed by Tiffany Dawn Hasse in collaboration with Kristen Fuller, M.D.

The underlying reasons why I have to repeatedly re-zip things, blink a certain way, count to an odd number, check behind my shower curtain to ensure no one is hiding to plot my abduction, make sure that computer cords are not rat tails, etc., will never be clear to me. Is it the result of a poor reaction to the anesthesiology that was administered during my wisdom teeth extraction? These aggravating thoughts and compulsions began immediately after the procedure. Or is it related to PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infection) which is a proposed theory connoting a strange relationship between group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection with rapidly developing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the basal ganglia? Is it simply a hereditary byproduct of my genetic makeup associated with my nervous personality ? Or is it a defense tactic I developed through having an overly concerned mother?

The consequences associated with my OCD

Growing up with mild, in fact dormant, obsessive-compulsive disorder, I would have never proposed such bizarre questions until 2002, when an exacerbated overnight onset of severe OCD mentally paralyzed me. I'd just had my wisdom teeth removed and was immediately bombarded with incessant and intrusive unwanted thoughts, ranging from a fear of being gay to questioning if I was truly seeing the sky as blue. I'm sure similar thoughts had passed through my mind before; however, they must have been filtered out of my conscious, as I never had such incapacitating ideas enter my train of thought before. During the summer of 2002, not one thought was left unfiltered from my conscious. Thoughts that didn't even matter and held no significance were debilitating; they prevented me from accomplishing the simplest, most mundane tasks. Tying my shoe only to untie it repetitively, continuously being tardy for work and school, spending long hours in a bathroom engaging in compulsive rituals such as tapping inanimate objects endlessly with no resolution, and finally medically withdrawing from college, eventually to drop out completely not once but twice, were just a few of the consequences I endured.

Seeking help

After seeing a medical specialist for OCD, I had tried a mixed cocktail of medications over a 10-year span, including escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), risperidone (Risperdal), aripiprazole (Abilify), sertraline (Zoloft), clomipramine (Anafranil), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and finally, after a recent bipolar disorder II diagnosis, lurasidone (Latuda). The only medication that has remotely curbed my intrusive thoughts and repetitive compulsions is lurasidone, giving me approximately 60 to 70 percent relief from my symptoms.

Many psychologists and psychiatrists would argue that a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacological management might be the only successful treatment approach for an individual plagued with OCD. If an individual is brave enough to undergo exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), a type of CBT that has been shown to relieve symptoms of OCD and anxiety through desensitization and habituation, then my hat is off to them; however, I may have an alternative perspective. It's not a perspective that has been researched or proven in clinical trials — just a coping mechanism I have learned through years of suffering and endless hours of therapy that has allowed me to see light at the end of the tunnel.

In my experience with cognitive behavioral therapy, it may be semi-helpful by deconstructing or cognitively restructuring the importance of obsessive thoughts in a hierarchical order; however, I still encounter many problems with this type of technique, especially because each and every OCD thought that gets stuck in my mind, big or small, tends to hold great importance. Thoughts associated with becoming pregnant , seeing my family suffer, or living with rats are deeply rooted within me, and simply deconstructing them to meaningless underlying triggers was not a successful approach for me.

In the majority of cases of severe OCD, I believe pharmacological management is a must. A neurological malfunction of transitioning from gear to gear, or fight-or-flight, is surely out of whack and often falsely fired, and therefore, medication works to help balance this misfiring of certain neurotransmitters.

Exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP) is an aggressive and abrasive approach that did not work for me, although it may be helpful for militant-minded souls that seek direct structure. When I was enrolled in the OCD treatment program at UCLA, I had an intense fear of gaining weight, to the point that I thought my body could morph into something unsightly. I remember being encouraged to literally pour chocolate on my thighs when the repetitive fear occurred that chocolate, if touching my skin, could seep through the epidermal layers, and thus make my thighs bigger. While I boldly mustered up the courage to go through with this ERP technique recommended by my specialist, the intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors associated with my OCD still and often abstain these techniques. Yes, the idea of initially provoking my anxiety in the hope of habituating and desensitizing its triggers sounds great in theory, and even in a technical scientific sense; but as a human with real emotions and feelings, I find this therapy aggressive and infringing upon my comfort level.

How I conquered my OCD

So, what does a person incapacitated with OCD do? If, as a person with severe OCD, I truly had an answer, I would probably leave my house more often, take a risk once in a while, and live freely without fearing the mundane nuances associated with public places. It's been my experience with OCD to take everything one second at a time and remain grateful for those good seconds. If I were to take OCD one day at a time, well, too many millions of internal battles would be lost in this 24-hour period. I have learned to live with my OCD through writing and performing as a spoken word artist. I have taken the time to explore my pain and transmute it into an art form which has allowed me to explore the topic of pain as an interesting and beneficial subject matter. I am the last person to attempt to tell any individuals with OCD what the best therapy approach is for them, but I will encourage each and every individual to explore their own pain, and believe that manageability can come in many forms, from classic techniques to intricate art forms, in order for healing to begin.

Tiffany Dawn Hasse is a performance poet, a TED talk speaker , and an individual successfully living with OCD who strives to share about her disorder through her art of written and spoken word.

Kristen Fuller M.D. is a clinical writer for Center For Discovery.

Facebook image: pathdoc/Shutterstock

Kristen Fuller, M.D., is a physician and a clinical mental health writer for Center For Discovery.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- NeuroLaunch

Unraveling OCD: A Comprehensive Analysis of Case Studies and Examples

- OCD in Popular Culture

- NeuroLaunch editorial team

- July 29, 2024

- Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

From Howard Hughes’s compulsive hand-washing to the silent struggles of millions worldwide, the labyrinth of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder unfolds through a tapestry of compelling case studies that illuminate the complexities of the human mind. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition characterized by persistent, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) that individuals feel compelled to perform to alleviate anxiety or prevent perceived catastrophic outcomes. While the disorder affects approximately 2-3% of the global population, its impact on individuals’ lives can be profound and far-reaching.

Case studies have long been a cornerstone of OCD research, offering invaluable insights into the nuanced manifestations of the disorder and the effectiveness of various treatment approaches. These detailed examinations of individual experiences provide researchers and clinicians with a deeper understanding of OCD’s complexities, helping to refine diagnostic criteria and develop more targeted interventions.

In this comprehensive exploration of OCD case studies, we will delve into the intricate world of obsessions and compulsions, examining notable examples, analyzing patterns, and discussing the implications for research and clinical practice. By unraveling these compelling narratives, we aim to shed light on the diverse presentations of OCD and the ongoing efforts to improve the lives of those affected by this challenging disorder.

The Anatomy of an OCD Case Study

To fully appreciate the value of OCD case studies, it’s essential to understand their key components and the methodologies employed in their creation. A well-constructed OCD case study typically includes several crucial elements:

1. Patient background: This section provides relevant demographic information, medical history, and any significant life events that may have contributed to the development or exacerbation of OCD symptoms.

2. Symptom presentation: A detailed description of the patient’s specific obsessions and compulsions, including their frequency, intensity, and impact on daily functioning.

3. Diagnostic process: An outline of the steps taken to diagnose OCD, including any assessments or screening tools used.

4. Treatment approach: A comprehensive account of the interventions employed, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), or medication management.

5. Treatment outcomes: An evaluation of the patient’s progress, including any changes in symptom severity, quality of life, and overall functioning.

6. Follow-up and long-term prognosis: Information on the patient’s status after treatment completion and any recommendations for ongoing care.

Researchers employ various methodologies when conducting OCD case studies, ranging from single-subject designs to more extensive case series. These approaches allow for in-depth analysis of individual experiences while also identifying patterns across multiple cases. Some common methodologies include:

– Single-case experimental designs: These studies involve repeated measurements of an individual’s symptoms before, during, and after treatment interventions.

– Qualitative case studies: Researchers use interviews and observational techniques to gather rich, descriptive data about a patient’s experiences with OCD.

– Longitudinal case studies: These investigations follow individuals with OCD over extended periods, often years, to track the course of the disorder and the long-term effects of treatment.

It’s crucial to note that ethical considerations play a significant role in OCD case study research. Researchers must obtain informed consent from participants, maintain confidentiality, and ensure that the potential benefits of the study outweigh any risks to the individual. Additionally, researchers must be sensitive to the potential impact of participating in a case study on the individual’s OCD symptoms and overall well-being.

Notable OCD Case Study Examples

One of the most famous OCD case studies is that of Howard Hughes, the American business magnate, aviator, and film producer. Hughes’s struggle with OCD has been well-documented and offers a compelling example of how the disorder can manifest in extreme ways, even in individuals of exceptional talent and success.

Hughes’s OCD symptoms reportedly included:

– Extreme fear of contamination, leading to compulsive hand-washing and elaborate cleaning rituals – Obsessive concerns about germs and disease – Strict control over his environment, including detailed instructions for staff on how to handle objects – Hoarding tendencies, particularly related to tissues and other personal items

The case of Howard Hughes illustrates the potential severity of OCD and how it can significantly impact an individual’s life, regardless of their social status or achievements. It also highlights the importance of early intervention and appropriate treatment in managing OCD symptoms.

While Hughes’s case is well-known, contemporary OCD case studies continue to provide valuable insights into the diverse manifestations of the disorder. For instance, a case study exploring one of the most severe cases of OCD might reveal the extreme lengths to which individuals may go to alleviate their anxiety and the profound impact on their daily functioning.

Other notable OCD case study examples include:

1. The case of “Mary,” a 32-year-old woman with contamination-related OCD who spent up to 8 hours a day showering and cleaning her home. Her case study highlighted the effectiveness of Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) therapy in reducing her symptoms and improving her quality of life.

2. “John,” a 45-year-old man with religious scrupulosity OCD, who experienced intrusive blasphemous thoughts and engaged in excessive prayer and confession rituals. His case demonstrated the importance of tailoring CBT techniques to address specific OCD themes.

3. “Sarah,” a 16-year-old girl with symmetry and ordering compulsions, whose case study showcased the potential benefits of family-based interventions in treating adolescent OCD.

These diverse case studies underscore the heterogeneity of OCD presentations and the need for individualized treatment approaches. They also reveal fascinating aspects of OCD that may not be immediately apparent, such as the wide range of obsessions and compulsions that can manifest in different individuals.

Analyzing OCD Cases: Patterns and Insights

When examining multiple OCD case studies, certain patterns and themes begin to emerge, offering valuable insights into the nature of the disorder and its treatment. Some common themes observed across various OCD cases include:

1. Age of onset: Many case studies report that OCD symptoms often begin in childhood or adolescence, although the disorder can develop at any age.

2. Comorbidity: A significant number of individuals with OCD also experience other mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety disorders, or eating disorders. This raises important questions about whether OCD should be classified as an anxiety disorder or as a distinct entity.

3. Impact on relationships: OCD frequently affects interpersonal relationships, with many case studies highlighting the strain placed on family members and partners.

4. Fluctuating symptom severity: Case studies often reveal that OCD symptoms can wax and wane over time, influenced by various factors such as stress, life events, and treatment adherence.

5. Treatment response variability: While many individuals respond well to evidence-based treatments like CBT and ERP, case studies also illustrate that some patients may require more intensive or prolonged interventions.

Despite these common themes, each OCD case presents unique aspects that contribute to our understanding of the disorder. For example:

– Specific trigger events: Some case studies describe particular life events or traumas that seemed to precipitate or exacerbate OCD symptoms, providing insights into potential environmental factors in OCD development.

– Cultural influences: Cases from diverse cultural backgrounds highlight how OCD manifestations can be shaped by cultural beliefs and practices, emphasizing the need for culturally sensitive assessment and treatment approaches.

– Atypical presentations: Certain case studies document unusual or less common OCD symptoms, expanding our understanding of the disorder’s potential manifestations.

By analyzing multiple OCD case studies, researchers and clinicians can draw valuable lessons that inform both theory and practice. These insights include:

1. The importance of early identification and intervention in improving long-term outcomes for individuals with OCD.

2. The need for personalized treatment plans that address the specific obsessions and compulsions of each individual.

3. The potential benefits of involving family members or support systems in the treatment process.

4. The value of long-term follow-up and maintenance strategies to prevent relapse and manage residual symptoms.

5. The significance of addressing comorbid conditions alongside OCD symptoms for comprehensive care.

These lessons derived from case studies contribute to the ongoing refinement of OCD treatment approaches and help clinicians better understand the complexities of the disorder.

Treatment Approaches Highlighted in OCD Case Studies

OCD case studies have been instrumental in showcasing the effectiveness of various treatment approaches and highlighting areas for improvement. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), particularly Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), emerges as a cornerstone of OCD treatment in many case studies.

For instance, a case study of a 28-year-old man with severe contamination OCD demonstrated how ERP techniques, such as gradually touching “contaminated” objects without washing, led to significant symptom reduction over 16 weeks of treatment. This case highlighted the importance of a structured, gradual approach to exposure exercises and the role of the therapist in providing support and encouragement throughout the process.

Another case study focused on a 42-year-old woman with checking compulsions related to fear of harming others. This study illustrated the effectiveness of combining traditional ERP with cognitive restructuring techniques to address the patient’s overinflated sense of responsibility. The case emphasized the importance of tailoring CBT interventions to address specific OCD themes and underlying beliefs.

Medication management, particularly the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), is another treatment approach frequently discussed in OCD case studies. For example, a case series examining the use of fluoxetine in treating pediatric OCD demonstrated the potential benefits of medication in reducing symptom severity and improving overall functioning. However, these cases also highlighted the variability in individual responses to medication and the need for careful monitoring and dose adjustments.

Some case studies have also explored innovative treatment methods for OCD. For instance:

1. A case study of a 35-year-old woman with treatment-resistant OCD documented the successful use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) as an adjunct to traditional CBT, resulting in significant symptom improvement.

2. Another case report described the application of virtual reality exposure therapy for a patient with OCD related to fear of contamination in public spaces, demonstrating the potential of technology-enhanced interventions.

3. A case series examining the use of mindfulness-based interventions for OCD showed promising results in reducing symptoms and improving overall well-being, particularly for individuals who had not fully responded to traditional CBT approaches.

These case studies not only showcase the effectiveness of established treatments but also point to potential new directions in OCD management, emphasizing the importance of continued research and innovation in the field.

The Impact of OCD Case Studies on Research and Practice

OCD case studies have had a profound impact on both research and clinical practice, influencing diagnostic criteria, treatment protocols, and our overall understanding of the disorder. One significant contribution of case studies has been their role in informing and refining the diagnostic criteria for OCD.

For example, case studies have helped to elucidate the diverse manifestations of OCD, leading to a broader recognition of less common symptom presentations in diagnostic manuals. This expanded understanding has improved clinicians’ ability to accurately identify and diagnose OCD, even in cases where symptoms may not align with more stereotypical presentations.

Case studies have also played a crucial role in shaping OCD treatment protocols. By providing detailed accounts of treatment successes and challenges, these studies have:

1. Helped to establish the efficacy of CBT and ERP as first-line treatments for OCD. 2. Informed the development of treatment guidelines and best practices. 3. Highlighted the importance of tailoring interventions to individual needs and symptom presentations. 4. Demonstrated the potential benefits of combining multiple treatment modalities, such as psychotherapy and medication.

Furthermore, OCD case studies have influenced future research directions by:

1. Identifying gaps in current knowledge and treatment approaches. 2. Generating hypotheses for larger-scale studies. 3. Providing preliminary evidence for novel interventions or treatment combinations. 4. Highlighting the need for research on specific OCD subtypes or populations.

As we look to the future, case study research in OCD continues to evolve. Emerging trends include:

1. Increased focus on long-term follow-up studies to better understand the course of OCD over the lifespan. 2. Exploration of the role of new technologies, such as smartphone apps and wearable devices, in OCD assessment and treatment. 3. Investigation of the neurobiological correlates of OCD through case studies incorporating neuroimaging and other biological measures. 4. Examination of the impact of cultural factors on OCD presentation and treatment outcomes through diverse, cross-cultural case studies.

These ongoing efforts in case study research promise to further enhance our understanding of OCD and improve outcomes for individuals living with the disorder.

In conclusion, the examination of OCD case studies provides a wealth of insights into the complex nature of this challenging disorder. From the famous case of Howard Hughes to the countless unnamed individuals whose experiences have been documented in research, these studies offer a window into the diverse manifestations of OCD and the ongoing efforts to improve diagnosis and treatment.

Key takeaways from our exploration of OCD case studies include:

1. The importance of individualized assessment and treatment approaches, given the heterogeneity of OCD presentations. 2. The effectiveness of evidence-based treatments like CBT and ERP, as well as the potential of innovative interventions. 3. The value of long-term follow-up and comprehensive care that addresses comorbid conditions. 4. The ongoing need for research to refine our understanding of OCD and develop more effective treatments.

As we continue to unravel the complexities of OCD through case studies and other research methodologies, it is crucial to maintain a sense of empathy and awareness for individuals living with this disorder. By sharing these stories and insights, we not only advance scientific understanding but also help to reduce stigma and promote compassion for those affected by OCD.

The journey to fully understand and effectively treat OCD is ongoing, and case studies will undoubtedly continue to play a vital role in this process. As we look to the future, the lessons learned from these individual narratives will guide researchers, clinicians, and individuals with OCD towards more effective management strategies and, ultimately, improved quality of life for all those affected by this challenging disorder.

References:

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

2. Abramowitz, J. S., Taylor, S., & McKay, D. (2009). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Lancet, 374(9688), 491-499.

3. Veale, D., & Roberts, A. (2014). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMJ, 348, g2183.

4. Öst, L. G., Havnen, A., Hansen, B., & Kvale, G. (2015). Cognitive behavioral treatments of obsessive–compulsive disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published 1993–2014. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 156-169.

5. Brakoulias, V., Starcevic, V., Belloch, A., Brown, C., Ferrao, Y. A., Fontenelle, L. F., … & Kyrios, M. (2017). Comorbidity, age of onset and suicidality in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD): An international collaboration. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 76, 79-86.

6. Sookman, D., & Steketee, G. (2010). Specialized cognitive behavior therapy for treatment resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. In D. Sookman & R. L. Leahy (Eds.), Treatment resistant anxiety disorders: Resolving impasses to symptom remission (pp. 31-74). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

7. Fineberg, N. A., Brown, A., Reghunandanan, S., & Pampaloni, I. (2012). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 15(8), 1173-1191.

8. Pallanti, S., & Grassi, G. (2014). Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidities. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 15(17), 2543-2552.

9. Hirschtritt, M. E., Bloch, M. H., & Mathews, C. A. (2017). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA, 317(13), 1358-1367.

10. Skapinakis, P., Caldwell, D. M., Hollingworth, W., Bryden, P., Fineberg, N. A., Salkovskis, P., … & Lewis, G. (2016). Pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for management of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 730-739.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

About NeuroLaunch

- Copyright Notice

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise With Us

- Mental Health

IV supply information; Hurricane Milton updates for Florida patients

IV fluid supply: Like many medical facilities across the nation, our supply chain is feeling the effects of Hurricane Helene’s aftermath. Johns Hopkins Medicine currently has a sufficient IV fluid supply to meet treatment, surgical and emergency needs. However, we have put proactive conservation measures into place to ensure normal operations, always with patient safety as our first priority.

Hurricane Milton: Get updates about Hurricane Milton’s impact on Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital and our outpatient centers in Florida.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Clinical Care. Research. Advocacy.

The goals of the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Program are to provide the most effective clinical care to individuals with OCD, to conduct research to identify its causes with the aim of developing more effective treatments and preventive measures, and advocating through education for those suffering from OCD.

The Johns Hopkins Difference

Request an Appointment: 410-955-5212

What is obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental disorder afflicting 1-3% of the population. Symptoms usually begin in childhood or adolescence and may affect people throughout their lives, varying from mild to severely disabling. Patients are often embarrassed by their symptoms and misunderstood by others. Effective treatments (medication and behavioral) are available, but the search for better treatment options continues.

Meet Our Co-Director Gerald Nestadt, M.B.B.Ch., M.P.H.

Dr. Gerald Nestadt, a psychiatrist, co-directs the OCD Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital and is the Principal Investigator of the OCD Family/Genetic Studies. He has over 20 years of experience providing treatment for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and other psychiatric disorders as well as extensive experience conducting clinical research in psychiatry.

Contact the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Program

For research information:.

Dr. Jack Samuels JHU Psychiatry Research 550 Building, Room 902 Baltimore, MD 21205

Phone: 410-614-4942 Email: [email protected]

For clinical information:

The Johns Hopkins Hospital 600 N. Wolfe Street, Meyer 13 Baltimore, MD 21287

Phone: 410-955-5212

CLINICAL CASE STUDY article

A clinical case study of the use of ecological momentary assessment in obsessive compulsive disorder.

- Brain, Behaviour and Mental Health Research Group, School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

Accurate assessment of obsessions and compulsions is a crucial step in treatment planning for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). In this clinical case study, we sought to determine if the use of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) could provide additional symptom information beyond that captured during standard assessment of OCD. We studied three adults diagnosed with OCD and compared the number and types of obsessions and compulsions captured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) compared to EMA. Following completion of the Y-BOCS interview, participants then recorded their OCD symptoms into a digital voice recorder across a 12-h period in reply to randomly sent mobile phone SMS prompts. The EMA approach yielded a lower number of symptoms of obsessions and compulsions than the Y-BOCS but produced additional types of obsessions and compulsions not previously identified by the Y-BOCS. We conclude that the EMA-OCD procedure may represent a worthy addition to the suite of assessment tools used when working with clients who have OCD. Further research with larger samples is required to strengthen this conclusion.

Introduction

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a disabling anxiety disorder characterized by upsetting, unwanted cognitions (obsessions) and intense and time consuming recurrent compulsions ( American Psychiatric Association, 2000 ). The idiosyncratic nature of the symptoms of OCD ( Whittal et al., 2010 ) represents a challenge to completing accurate and comprehensive assessments, which if not achieved, can have a deleterious effect on the provision of effective treatment for the disorder ( Kim et al., 1989 ; Taylor, 1995 ; Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ; Deacon and Abramowitz, 2005 ).

Accurately assessing the full range of symptoms of OCD requires reliable and psychometrically sound diagnostic instruments and measures ( Taylor, 1995 , 1998 ; Rees, 2009 ) alongside the standard clinical interview. Although the most commonly used psychometric instrument for assessing OCD, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) ( Goodman et al., 1989a , b ), has acceptable reliability and convergent validity, it has been criticized by Taylor (1995) for weak discriminant validity. Taylor also highlighted that it remains susceptible to administration variance, relies on client memory recall, and is time consuming to administer. As with all measures completed retrospectively, selective memory biases affect the type of information reported by clients about their symptoms ( Clark, 1988 ; Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ; Stone et al., 2004 ). Glass and Arnkoff (1997 , p. 912) have summarized several disadvantages of structured inventories; first, they contain prototypical statements which may fail to capture the idiosyncratic nature of the client's actual thoughts; second, they can be affected by post-hoc reappraisals of what clients feel, as the data is subject to memory recall biases; and finally they may fail to adequately capture the client's internal dialog due to the limitations of the best fit question structure.

Discrepancies have been reported between data collected in the client's natural environment ( in situ ) and those based on the client's later recall ( de Beurs et al., 1992 ; Marks and Hemsley, 1999 ; Stone et al., 2004) . Such discrepancies may be further affected by factors such as the complexity and diversity of obsessions and compulsions, not to mention the ego-dystonic nature of many OCD clients' obsessional thoughts. It seems likely that clients with distressing ego-dystonic obsessions, for example, those involving sexual, aggressive, and/or religious themes may experience a heightened level of discomfort in reporting their obsessions in a face to face assessment with a clinician, thus reducing their willingness to accurately report ( Taylor, 1995 ; Newth and Rachman, 2001 ; Grant et al., 2006 ; Rees, 2009 ). This may contribute to an underreporting of these obsessions, and hence an inaccurate understanding and a restriction of the clinician's ability to adequately treat the client ( Grant et al., 2006 ; Rachman, 2007 ).

Exposure and response prevention, cognitive therapy, and pharmacological interventions have been shown to be effective in the treatment of OCD ( Abramowitz, 1997 , 2001 ; Foa and Franklin, 2001 ; Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ; Fisher and Wells, 2008 ; Chosak et al., 2009 ). Self-monitoring is a useful therapeutic technique that provides essential information to assist in the development of exposure hierarchies and behavioral experiments used in cognitive therapy ( Tolin, 2009 ). Clients typically observe and record their experiences of target behaviors, including triggers, environmental events surrounding those experiences, and their response to those experiences ( Cormier and Nurius, 2003 ). Such self-monitoring can be used to both assist assessment and/or as an intervention. Cormier and Nurius (2003) explained that the mere act of observing and monitoring one's own behavior and experiences can produce change. As people observe themselves and collect data about what they observe, their behavior may be influenced.

A form of self-monitoring and alternative to the typical clinic-based assessment of OCD is the use of sampling from the client's real-world experiences, a procedure known as Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) ( Schwartz and Stone, 1998 ; Stone and Shiffman, 1994 , 2002 ). EMA does not rely on measurements using memory recall within the clinical setting, but rather allows for collection of information about the client's experiences in their natural setting, potentially improving the assessment's ecological validity ( Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ). In situ sampling techniques have been successfully used in psychology, psychiatry, and occupational therapy (for a more detailed account see research by Morgan et al., 1990 ; de Beurs et al., 1992 ; Kamarack et al., 1998 ; Litt et al., 1998 ; Kimhy et al., 2006 ; Gloster et al., 2008 ; Putnam and McSweeney, 2008 ; Trull et al., 2008 ). Generally it is agreed that EMA offers broader assessment within the client's natural environment, as it includes random time sampling of the client's experience, recording of events associated with the client's experience, and self-reports regarding the client's behaviors and physiological experiences ( Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ). Because this assessment method accesses information about the client's situation, the difficulties of memory distortions like recall bias are reduced ( Schwartz and Stone, 1998 ; Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ).

Given that accurate assessment of obsessions and compulsions is a critical aspect of treatment planning and that reliance on self-report and clinician interview has some known limitations, the purpose of this study was to investigate the utility of EMA as a potential adjunct to the conventional assessment of OCD. Specifically, we sought to compare the amount and type of information regarding obsessions and compulsions collected via EMA vs. standard assessment using the gold-standard symptom interview for OCD. As this is a pilot clinical case study, we offer the following tentative hypothesis: (1) EMA will yield additional types of obsessions and compulsions not captured by the Y-BOCS.

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited through clients presenting to the OCD clinic at Curtin University. They were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) ( First et al., 1997 ). Inclusion in the study was based on receiving a primary diagnosis of OCD, and a Y-BOCS ( Goodman et al., 1989a , b ) score of more than 16, placing their OCD symptom severity within the clinical range ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ). Participants were excluded if they presented with current suicidal ideation, psychotic disorders, apparent organic causes of anxiety, were severely depressed, or if they had an intellectual disability. One potential participant was excluded post evaluation despite meeting the inclusion criteria, as she did not own a mobile phone, and reported having “blackouts” throughout the day. The three participants all had OCD symptoms in the “severe” range according to the YBOCS. In order to ensure that participants remain anonymous, pseudonyms have been used.

Participant A

Mary was a 28-year-old female who lived with her husband and small dog. She reported that for approximately 1 year she had been experiencing distressing intrusive thoughts in relation to harming her loved ones, herself, or her dog; for example, by stabbing, electrocution, or breaking the dog's neck. Mary said that she also had reoccurring thoughts and images that her husband or other family members might die. She reported engaging in some rituals, for example straightening pillows and rearranging tea-towels; but mostly reported using “safety nets” in response to her unwanted cognitions; for example ensuring that she was not alone (to prevent self-harm); avoidance and removal of feared object; extensive reassurance seeking from family members. According to the Y-BOCS measure, Mary scored a subtotal of 14 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 18 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 32, classifying her symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

Mary reported that her OCD first occurred after her grandmother passed away about 6 years ago. She explained they had a very close relationship, she said she found it “unbearably distressing” to visit her while she was dying. Mary reported that on one occasion whilst in a coma, her grandmother sat up and gasped, which she found extremely frightening and still remembers it in vivid detail. She reported that she experienced thoughts that her grandmother was in pain and was going “into the unknown, to a scary place.” Mary reported feeling afraid of death and that if someone “even closer” to her died she “would not be able to cope” and that she would “lose control completely.” She stated that her biggest fear was that her husband, mother or father might die. Mary reported that she has been on various anti-depressants for about 10 years. She stated that recently her psychiatrist prescribed Solian (an antipsychotic) which she tried, and found was very effective at blocking out the intrusive thoughts. However, she ceased taking the medication due to nausea.

Participant B

John was a 5-year-old man who lived with his wife and adult son. He reported a long history of distressing intrusive thoughts, and compulsive behaviors. They are summarized in three ways. First, those that relate to religious obsessions, specifically the occult and satanic experiences/fear of being “possessed.” He reported responding to these unwanted cognitions by either washing his hands to cleanse himself; using more than six pieces of toilet paper to wipe after defecating to prevent the devil entering him via his anus; or looking for the number “555,” which represents “God. This is good.” John reported that failing to act in these ways would risk causing harm to his wife and son. Second, those that relate to checking compulsions, specifically when driving, and also checking that doors are locked—which he reported doing 4–12 times per night. He reported that if he thought he heard a “bump” when driving he would have to turn back to check he had not run anyone over, or would seek reassurance from his son or wife if they were passengers in the car with him. He stated that he feared that harm would come to his wife and son if he didn't perform these checks. Third, John said that he arranged shoes so that they were “lined up” and that the clothes in the cupboard were in the “right order.” He also reported the need to compulsively clean his son's bedroom, and that he wouldn't feel “right” until he had done so. According to the Y-BOCS measure, John scored a subtotal of 13 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 15 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 28, classifying his symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

John reported that his symptoms have been present for at least the last 29 years. He reported that his OCD first occurred after he had a “break-down” and tried to commit suicide by stabbing himself in the stomach before he turned 25 years of age. In the years leading up to this, John reported two poignant experiences which appear relevant to the development of his symptoms; he reported being involved in the euthanizing of two dogs whilst working as a Ranger's assistant; and that when he was young, he and his girlfriend at the time had a pregnancy termination. John reported feeling that these were “blasphemous” acts, and posed the question “Is God punishing me?” John reported that he had been on several different anti-depressants for about 19 years, with varying degrees of success and side-effects. He reported that he had seen a psychiatrist every 6 weeks for “many years” and finds being able to talk helpful.

Participant C

Paul was a 35-year-old man, who reported distressing intrusive thoughts and images in relation to harm coming to others as a consequence of him not checking that he had done what he is “supposed to do.” For example, he was concerned that someone at work would be harmed if he forgot to adequately cover shifts on the roster (something he is responsible for); or when a client of the service he coordinates was recently given a stereo, Paul reported that he feared that harm would come to the client if he didn't correctly check it to see if it was faulty, something he felt responsible to do.

Paul reported that only his partner knew of his difficulties. He stated that he did not allow his anxiety to interfere too much with his occupational functioning; however he did report that the main reason he does not practice in his profession is because of his OCD. According to the Y-BOCS measure, Paul scored a subtotal of 12 for Obsessions and a subtotal of 13 for Compulsions, giving an overall total of 25, classifying his symptoms as “severe” ( Steketee and Barlow, 2002 ).

Paul reported that his intrusive thoughts have “always been there.” He explained that one of the first clear memories he has of them, was when he was seven years old and he saw the film the “The Omen.” He reported remembering checking his head for the numbers “666.” Additionally, he reported remembering that he was concerned for his mother's safety. He reported that he had never taken medication for his OCD. He stated that he saw two therapists when he lived in the UK at an OCD center in London approximately 18 months ago. Paul said that he did not gain much from the first therapist, but believes that second therapist assisted him to look at his cognitions as “just thoughts.”

Materials and Methods

All screening of participants, interviewing and assessment, as well as administration of the study, was conducted by the first author, who was a provisionally registered psychologist undergoing postgraduate training at the time of the research, and was supervised by the second author, an experienced OCD clinician and academic. Potential participants were recruited from the Curtin OCD clinic. They were screened via telephone to ascertain their suitability for the study. A face-to-face assessment session using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First et al., 1997 ) was conducted to determine a primary OCD diagnosis, followed by the administration of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) interview and checklist ( Goodman et al., 1989b ) to identify the participants' obsessions and compulsions and their symptom severity. The Y-BOCS is the most widely used scale for OCD symptoms assessment and is considered by researchers to be the “gold standard” measure for symptom severity ( Deacon and Abramowitz, 2005 ; Himle and Franklin, 2009 ). It consists of two parts; a checklist of prelisted types of obsessions, usually endorsed by the clinician based on disclosures made by the client; and the severity scale which requires the client to rate the severity of their experience by answering the questions based on their recall. Goodman et al. (1989) note that the Y-BOCS has shown adequate interrater agreement, internal consistency, and validity.

Suitable participants then attended a second session where they signed consent forms and were given instructions about the study procedure. During the data collection using the Ecological Momentary Assessment data (EMA-OCD), participants used an Olympus WS-110 digital voice recorder to record their experiences throughout a 12 h period. Participants used their existing mobile phones to receive prompts via the mobile phone Short Message Service (SMS) to record their responses to the research questions. All three participants were then provided with an envelope containing the Olympus WS-100 digital voice recorder, a spare battery, and the participant prompt questions (see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Prompt questions .

Participants were asked to turn their mobile phones on during the data collection day by 10 am, ready to receive their SMS prompts. The researcher manually sent SMS prompts to the participants at random intervals; at least every 2 h (across 1 day, from 10 am to 10 pm), for a minimum of 10 data entries in keeping with research using EMA procedures (see, Stone and Shiffman, 2002 ); asking them to complete their responses to all four questions as details on the EMA-OCD Participant Questions Sheet. Participants were instructed not to respond to the SMS prompts if driving, and were asked to respond as quickly as possible to the prompts. Data was then downloaded from the voice recorder to the researcher's computer, and transcribed. During this process all identifying details were removed. During the debrief session open-ended questions were used to gather as much information as possible regarding the participant's experiences of the study, and suggestions for improvements. During the data collection day the researcher completed a journal to record his observations and reflections related to the use of the EMA. At the completion of the EMD-OCD data collection, each of the participants was provided with a debrief session (Mary by phone, and John and Paul, face to face). The debrief session focused on their experiences of the research and use of the digital voice recorder; and provided the opportunity for them to discuss anything else that arose they wished to tell the researcher. As stated above, the data was downloaded and transcribed by the first author. The Y-BOCS obsession and compulsion categories were used as a framework to compare the data generated from the EMA-OCD procedure. After the complete de-identified data set was tabled, it was provided to a second person who was an expert in OCD for verification of categories. In the case of any discrepancies agreement was reached via consensus.

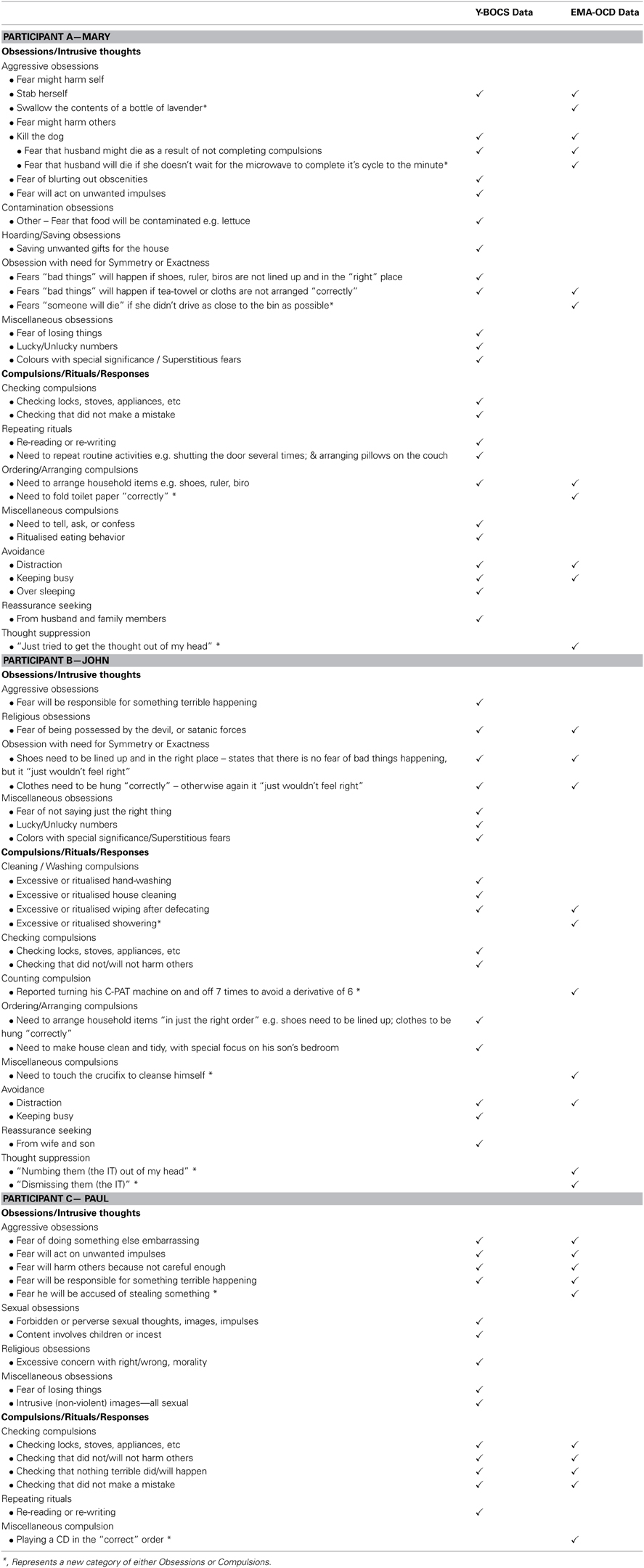

Number of reported symptoms

Table 2 provides a summary of the frequency and type of symptoms recorded during both the face-to-face session, which will be referred to as the Y-BOCS data and the EMA-OCD phase for the study, which will be referred to as the EMA–OCD data. As can be seen when comparing the data contained in the two columns, there are variations between the Y-BOCS data and the EMA-OCD data. All three participants reported more categories of both obsessions and compulsions in the Y-BOCS data, compared to that reported in the EMA-OCD data.

Table 2. Summary by participant of Y-BOCS data and EMA-OCD data .

Mary reported experiencing five categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and six categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data she reported experiencing two categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and three categories of Y-BOCS Compulsions. John reported experiencing four categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and five categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data he reported experiencing two categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and five categories of Y-BOCS Compulsions. Paul reported experiencing four categories of Y-BOCS Obsessions and two categories of Compulsions in the Y-BOCS data. In the EMA-OCD data he reported experiencing one category of Y-BOCS Obsessions, and two categories of Compulsions.

Comparison of content of symptoms

Both Mary and Paul reported previously unidentified Obsessions or intrusive thoughts in the EMA-OCD data, compared to the Y-BOCS data; and all three participants reported previously unidentified compulsions/rituals/responses in the EMA-OCD data. As can be seen in Table 2 , Mary reported two intrusive thoughts in the EMA-OCD data that were not recorded in the Y-BOCS data. Additionally, she reported a previously unreported obsession under the obsession category Obsession with need for Symmetry or Exactness , not reported in the Y-BOCS data. Mary also reported variations on her compulsive behaviors and the presence of thought suppression not identified during the administration of the Y-BOCS. The EMA-OCD data indicated that John substituted one of his compulsions for an alternative anxiety reducing act, which was not recorded in the Y-BOCS data and suggests the identification of a previously unreported compulsion. Additionally, the EMA-OCD data indicated that John engaged in thought suppression to neutralize his intrusive thoughts. Likewise, John's reported compulsive behaviors also varied between data sets. In the EMA-OCD data he reported three previously unreported compulsive behaviors, and like Mary also the presence of thought suppression. In addition to the above, the EMA-OCD data indicated that John substituted one of his rituals for another, when he touched a crucifix instead of performing his usual hand washing ritual to cleanse him-self of the potential satanic possession. This was not something reported in the Y-BOCS data.

This study investigated the utility of EMA as an adjunct assessment approach for OCD. Each of our study hypotheses was supported. As predicted the EMA procedure resulted in the identification of additional types of obsessions and compulsions not captured by the Y-BOCS interview. The finding that the EMA procedure identifies obsession and compulsion symptoms not captured by the Y-BOCS suggests that further studies in this area are warranted. As a pilot case study we cannot generalize from these initial findings but our results indicate that a larger study replicating the procedure used here, is justified. Importantly, the three participants in our study were representative of quite typical OCD clients in that they had severe levels of symptoms and had OCD for a number of years. The EMA procedure we used was found to be satisfactory to all three participants. Feedback from the participants at the de-briefing session included suggestions that this process would be helpful for therapy because it would provide the therapist and client with rich and current material regarding their symptom patterns. From a clinician's point of view, collecting the EMA data is not onerous because the entries are simply short answers collected on 12 occasions and thus is not a time-consuming exercise.

The EMA procedure as used in this study could provide clinicians with a new method by which to gain a current and accurate snap-shot of clients symptoms as they occur in real-time. This information could augment information gained from standard pencil and paper measures but also provide an “active” process which may help to engage clients in the therapeutic process. It seems likely that using a procedure like EMA with OCD clients will assist in understanding their OCD experiences, and thus assist in generating valuable information, supporting accurate assessment, client conceptualization, and ultimately treatment.

Despite these valuable findings, there are limitations of this study. As a pilot study and exploratory in nature, it is only possible to draw limited interpretations from the data provided. However, the preliminary findings of this study support the benefit of conducting further research into this procedure, where it may be possible to draw more empirically valid findings from a larger and more statistically powerful sample. Second, due to the lack of availability of date stamping, participants were asked to record the time they made each recording. Unfortunately this was not routinely provided by all participants, and hence creates an unanswerable question regarding the accuracy of the data recorded. As Stone and Shiffman (2002) discuss, a potential problem relates to participants recording their data based on their recall of what was occurring at the time of the SMS prompt, rather than immediately. Hence introducing possible memory bias, and undermining the premise of the study. Although this is certainly an unwanted variable, based on the EMA-OCD data provided it seems that except for Mary, both John and Paul responded promptly to the SMS messages, or recorded the time if they didn't. Mary on the other hand, reported during the debrief session that she was unable to record the time for the initial targets, but did so for subsequent SMS prompts. It was not possible to ascertain from her data the delay in time between the first SMS prompts and her recordings. In future applications of this procedure, it is recommended that the device used provides automatic date-stamping to address this limitation. Indeed, it may be possible to adapt the EMA methodology for use with smart phones via a dedicated OCD application.

Concluding Remarks

The findings from this study of three patients with severe OCD suggest that the use of EMA provides important additional information regarding obsessions and compulsions and may thus be a useful adjunct to the clinical assessment of OCD.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three participants for taking part in this study.

Abramowitz, J. S. (1997). Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a quantitative review. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol . 65, 44–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.44

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Abramowitz, J. S. (2001). Treatment of scrupulous obsessions and compulsions using exposure and response prevention: a case report. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 8, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80046-8

CrossRef Full Text

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn . Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Chosak, A., Marques, L., Fama, J., Renaud, S., and Wilhelm, S. (2009). Cognitive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case example. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.01.005

Clark, D. A. (1988). The validity of measures of cognition: a review of the literature. Cogn. Ther. Res . 12, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01172777

Cormier, S., and Nurius, P. S. (2003). Interviewing and Change Strategies for Helpers: Fundamental Skills and Cognitive Behavioral Interventions . Pacific Grove, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Deacon, B. J., and Abramowitz, J. S. (2005). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: factor analysis, construct validity, and suggestions for refinement. J. Anxiety Disord . 19, 573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.04.009

de Beurs, E., Lange, A., and Van Dyck, R. (1992). Self-monitoring of panic attacks and retrospective estimates of panic: discordant findings. Behav. Res. Ther . 30, 411–413. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90054-K

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., and Williams, J. B. W. (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Patient Edition (SCID-IP Version 2.0) . New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Fisher, P. L., and Wells, A. (2008). Metacognitive therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: a case series. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 39, 117–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.12.001

Foa, E. B., and Franklin, M. E. (2001). “Obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Clinical Handbook Of Psychological Disorders , ed D. H. Barlow (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 209–263.

Glass, C. R., and Arnkoff, D. B. (1997). Questionnaire methods of cognitive self-statement assessment. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol . 65, 919–927. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.6.911

Gloster, A. T., Richard, D. C. S., Himle, J., Koch, E., Anson, H., Lokers, L., et al. (2008). Accuracy of retrospective memory and covariation estimation in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther . 46, 642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.010

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., Heninger, G. R., et al. (1989a). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: ii. validity. Arch Gen. Psychiatry 46, 1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., et al. (1989b). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: i. development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen. Psychiatry 46, 1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007

Grant, J. E., Pinto, A., Gunnip, M., Mancebo, M. C., Eisen, J. L., and Rasmussen, S. A. (2006). Sexual obsessions and clinical correlates in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehen. Psychiatry 47, 325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.01.007

Himle, M. B., and Franklin, M. E. (2009). The more you do it, the easier it gets: exposure and response prevention for OCD. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.03.002

Kamarack, T. W., Shiffman, S. M., Smithline, L., Goodie, J. L., Paty, J. A., Gyns, M., et al. (1998). Effects of task strain, social conflict, and emotional activation on ambulatory cardiovascular activity: daily life consequences of recurring stress in a multiethnic adult sample. Health Psychol . 17, 17–29. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.17

Kim, J. A., Dysken, M. W., and Katz, R. (1989). Rating scales for obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiat. Anna . 19, 74–79.

Kimhy, D., Delespaul, P., Corcoran, C., Ahn, H., Yale, S., and Malaspina, D. (2006). Computerized experience sampling method (ESMc): assessing feasibility and validity among individuals with schizophrenia. J. Psychiat. Res . 40, 221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.007

Litt, M. D., Cooney, N. L., and Morse, P. (1998). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) with treated alcoholics: methodological problems and potential solutions. Health Psychol . 17, 48–52. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.48

Marks, M., and Hemsley, D. (1999). Retrospective versus prospective self-rating of anxiety symptoms and cognitions. J. Anxiety Disord . 13, 463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00015-8

Morgan, J., McSharry, K., and Sireling, L. (1990). Comparison of a system of staff prompting with a programmable electronic diary in a patient with Korsakoff's Syndrome. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 36, 225–229. doi: 10.1177/002076409003600308

Newth, S., and Rachman, S. (2001). The concealment of obsessions. Behav. Res. Ther . 39, 457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00006-1

Putnam, K. M., and McSweeney, L. B. (2008). Depressive symptoms and baseline prefrontal EEG alpha activity: a study utilizing Ecological Momentary Assessment. Biol. Psychol . 77, 237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.010

Rachman, S. (2007). Unwanted intrusive images in obsessive compulsive disorders. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 38, 402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.008

Rees, C. S. (2009). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Practical Guide to Treatment . East Hawthorn, VIC: IP Communications.

Schwartz, J. E., and Stone, A. A. (1998). Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol . 17, 6–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.17.1.6

Steketee, G., and Barlow, D. H. (2002). “Obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Anxiety and its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic, 2nd Edn . ed D. H. Barlow (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 516–550.

Stone, A., and Shiffman, S. (2002). Capturing momentary, self-report data: a proposal for reporting guidelines. Ann. Behav. Med . 24, 236–243. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2403_09

Stone, A. A., Broderick, J. E., Shiffman, S. S., and Schwartz, J. E. (2004). Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain , 107, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.020

Stone, A. A., and Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Ann. Behav. Med . 16, 199–202.

Taylor, S. (1995). Assessment of obsessions and compulsions: reliability, validity, and sensitivity to treatment effects. Clin. Psychol. Rev . 15, 261–296. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(95)00015-h

Taylor, S. (1998). “Assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder,” in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Theory, Research, and Treatment , eds R. P. Swinson, M. M. Antony, S. Rachman, and M. A. Richter (New York, NY: Guildford Press), 229–258.

Tolin, D. F. (2009). Alphabet Soup: ERP, CT, and ACT for OCD. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 16, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.07.001

Trull, T. J., Solhan, M. B., Tragesser, S. L., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Piasecki, T. M., et al. (2008). Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. J. Abnorm. Psychol . 117, 647–661. doi: 10.1037/a0012532

Whittal, M. L., Robichaud, M., and Woody, S. R. (2010). Cognitive treatment of obsessions: enhancing dissemination with video components. Cogn. Behav. Pract . 17, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.07.001

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), ecological momentary assessment, ecological momentary assessment data, anxiety disorders, assessment

Citation: Tilley PJM and Rees CS (2014) A clinical case study of the use of ecological momentary assessment in obsessive compulsive disorder. Front. Psychol . 5 :339. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00339

Received: 10 March 2014; Accepted: 01 April 2014; Published online: 17 April 2014.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2014 Tilley and Rees. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Clare S. Rees, Brain, Behaviour and Mental Health Research Group, School of Psychology and Speech Pathology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia e-mail: [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ind Psychiatry J

- v.22(2); Jul-Dec 2013

Juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report

Vikas menon.

Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is one of the more disabling and potentially chronic anxiety disorders that occurs in several medical settings. However, it is often under-recognized and under-treated. The condition is now known to be prevalent among children and adolescents. Obsessional images as a symptom occur less frequently than other types of obsessions. In this report, we describe a young boy who presented himself predominantly with obsessional images. The diagnostic and treatment challenges in juvenile OCD are discussed.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a clinically heterogeneous disorder with many possible subtypes.[ 1 ] The lifetime prevalence of OCD is around 2-3%.[ 2 ] Evidence points to a bimodal distribution of the age of onset, with studies of juvenile OCD finding a mean age at onset of around 10 years, and adult OCD studies finding a mean age at onset of 21 years.[ 2 , 3 ] Treatment is often delayed in childhood OCD as sufferers tend to view their symptoms as nonsensical and are often embarrassed to talk about it. Among the different forms of obsessions described, obsessional images are encountered less frequently in clinical practice. In this report, we discuss the case of a young boy who presented himself with predominantly obsessional images.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old boy studying in the 8 th grade was brought to the Psychiatry Outpatient Department with complaints of academic decline. Upon exploration the boy reported 2 years duration of symptoms that were characterized by intrusive, unpleasant and repetitive gory images of people engaged in violence or soaked in blood that interfered with his ability to study. He would have distressing palpitations, tremors and fearfulness simultaneously when he experiences these images and stated that they were contrary to his innate “peaceful nature” and “habitual thinking patterns.” He recognized these as absurd and irrational but claimed to be powerless in stopping them. Techniques to counter them like chanting hymns did not provide any tangible relief. Other repetitive behaviors like putting on switches repeatedly and counting objects in sets of five were being done by him as it “just didn’t feel right otherwise.” Of these, he clearly identified the repeated occurrence of the unpleasant images as the one that distressed him the most. When he presented to us, his scholastic performance was on the decline and this had led to strained relations with his parents. Initial explanations by the patient that he was “unable to concentrate” cut no ice with his family. It was only when the child mustered enough courage to tell his mother the details about the repeated images that his parents decided to seek help for him. The child was developmentally normal. Physical examination was unremarkable. Screening for organicity was negative. We made a diagnosis of OCD and he was started on 50 mg of fluvoxamine which was subsequently hiked to 100 mg. In addition, 0.5 mg of clonazepam was added to control the anxiety symptoms. Psychoeducation was given to the parents and child in order to alleviate their distress and reduce critical/hostile comments by the family. Currently with this regimen, the patient reports 50% improvement and his school performance has improved to their subjective satisfaction.

The above case is being reported for its rather unique and different presentation and to highlight the issues involved in diagnosis and management of pediatric OCD cases. Washing, grooming, checking rituals, and preoccupation with disease, danger, and doubt are the most commonly reported symptoms in childhood onset OCD.[ 4 ] However, in this case, obsessional images were the predominant symptom. OCD in children often takes inordinate time to come to clinical attention because patients may not readily describe their symptoms and family may not be willing to consider psychological causation as in the present case. Often family may inadvertently reinforce the compulsive behaviors of their off springs by compensating/participating in them and thus allowing them to continue functioning thinking that these behaviors will die a natural death. This phenomenon has been referred to as “family accommodation” in OCD and has been found to be correlated with poor family functioning and negative attitudes towards the patient.[ 5 ] Therefore, it is important to interview the parents and other associated family members about the context and burden of the obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children. This must be combined with a detailed assessment of the dysfunction in various areas – scholastic/self-care and socialization in order to elicit the true impact of symptoms. Structured instruments like the Children's Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale[ 6 ] are available to measure the symptom severity in young. Recently, a self-report version has been developed and found to correlate well with the original version.[ 7 ] This may be beneficial in settings like ours where clinician time and resources are limited. It has been proposed that juvenile OCD may be a developmental subtype of the disorder with its own unique correlates that differ from adult OCD. Some of the differences noted are the higher male preponderance, increased familial loading, frequent lack of insight, comorbidity with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders, major depression, tic disorders, and poorer response to treatment with antiobsessional medications in juvenile OCD.[ 3 , 8 ] This could have important implications for case management and research. More work needs to be done to outline the course of juvenile OCD and to ascertain the persistence of clinical features into adulthood.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a common disabling psychiatric condition that occurs across the life span. The diagnosis and management of pediatric OCD cases offer unique challenges. Clinicians must be alert to the possibility of obsessive-compulsive symptoms when evaluating children with emotional and behavioral disorders. We propose that screening questions to rule out OCD must be a part of routine mental status examination in children and adolescents. The management must include a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments that are likely to have variable success rates.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.