Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 January 2022

Wireless power transfer system with enhanced efficiency by using frequency reconfigurable metamaterial

- Dongyong Shan 1 ,

- Haiyue Wang 3 ,

- Ke Cao 1 &

- Junhua Zhang 2

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 331 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

28 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Devices for energy harvesting

- Electrical and electronic engineering

- Electronic devices

- Power distribution

The wireless power transfer (WPT) system has been widely used in various fields such as household appliances, electric vehicle charging and sensor applications. A frequency reconfigurable magnetic resonant coupling wireless power transfer (MRCWPT) system with dynamically enhanced efficiency by using the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is proposed in this paper. The reconfigurability is achieved by adjusting the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor connected in the coil of the system. Finite element simulation results have shown that the frequency reconfigurable electromagnetic metamaterial can manipulate the direction of the electromagnetic field of the system due to its abnormal effective permeability. The ultra-thin frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is designed at different working frequencies of 14.1 MHz, 15 MHz, 16.2 MHz, 17.5 MHz, 19.3 MHz, 21.7 MHz and 25 MHz to enhance the magnetic field and power transfer efficiency (PTE) of the system. Frequency reconfigurable mechanism of the system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is derived by the equivalent circuit theory. Finally, further measurement which verifies the simulation by reasonable agreement is carried out. PTE of the system by adding the metamaterial are 59%, 73%, 67%, 66%, 65%, 60% and 58% at different working frequencies. PTE of the system with and without the metamaterial is 72% and 49% at the distance of 120 mm and the frequency of 15 MHz, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Optimal frequency for magnetic resonant wireless power transfer in conducting medium

A multimode metamaterial for a compact and robust dualband wireless power transfer system

Wireless power transfer system rigid to tissue characteristics using metamaterial inspired geometry for biomedical implant applications

Introduction.

The wireless power transfer (WPT) system is used for the transmission of energy without a direct physical cable connection, which is useful to power loads where using cables is hazardous and inconvenient 1 , 2 , 3 . The magnetic resonant coupling wireless power transfer (MRCWPT) system has relatively high transfer efficiency over relatively long distances, and the MRCWPT system has gained lots of attention. And the MRCWPT system is much promising in the field of charging 4 , 5 , 6 , which has been applied in potential applications such as medical implants, electric vehicle charging, sensor networks and consumer electronics 7 , 8 , 9 .

For conventional MRCWPT systems, both the transmitter and the receiver have the same resonant frequency to maintain relatively high power transfer efficiency (PTE) 10 , 11 . The receiver and the transmitter work at the single resonant frequency. When the electrical energy is transmitted from the transmitter to the receiver at the different working frequency, failures and malfunctions may be caused regardless of receivers’ demands. Also, PTE of the system reduces. In order to solve the problem, the frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with additional control circuits is proposed in 12 by changing the resonant capacitance value. An efficient and reconfigurable rectifier circuit, with the capability of automatically switching from low-power to high-power operation mode, is presented in 13 . The new topology allows the rectifier to convert RF power to DC power efficiently over an extended input power range. The frequency reconfigurable technology is achieved in 14 by varying the distance between the receiver and the transmitter of the MRCWPT system. A shape-reconfigurable MRCWPT system in 15 achieves frequency reconfigurability by different structures of resonant coils. A novel planar-spiral transmitter coil (TX-coil) with an outer-tight and inner-sparse configuration is proposed to achieve a high quality factor and uniform magnetic field, which ensures high efficiency and improves the misalignment tolerance for several-megahertz WPT systems in 16 . The above MRCWPT systems have the frequency reconfigurable property, but volume and complexity of the system increase. In order to obtain higher PTE and power receivers at different frequencies, a frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system is presented by adjusting the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor connected in the coil of the system in this paper.

At present, many researchers proposed MRCWPT systems to further enhance PTE and extend the distance of the system. A kind of method by adding relay resonators is proposed in 17 . It is obvious that the distance and PTE of the system are extended. Intermediate resonators arranged between the transmitter and the receiver are used to transmit the magnetic field. This method is used to improve PTE of the system to maximize the benefits of magnetic field repeaters 18 . In 19 , 20 , 21 , MRCWPT systems with the metamaterial are proposed. Some MRCWPT systems with repeaters and metamaterial are analyzed for applications in 22 . The analysis shows that PTE of MRCWPT systems with repeaters and metamaterial is improved in different ways. Metamaterial can provide the MRCWPT system with various tunable functions. And the MRCWPT system with nonidentical coils using metamaterial is proposed in 21 . However, further investigation should be carried out about MRCWPT systems using metamaterial to improve the PTE and the distance. Investigations about the metamaterial is mainly on the far field, but the metamaterial used in the MRCWPT system on near field is lacking. Recently, some MRCWPT systems using metamateial are reported in 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 . Theoretical analysis and experimental investigation about using metamaterial to improve PTE of the system are shown. In 23 , PTE of the system increases from 17 to 35% by using metamaterial at the working frequency of 27.12 MHz. Maximum 25.4% efficiency enhancement is achieved when the distance between Tx and Rx coils is 15 cm, and in overall distance variation cases, the proposed two-stack hybrid metamaterial slab make the power transfer efficiency increase in 26 . The metamaterial is used in the MRCWPT system, and the enhanced PTE is 54.3% at the distance of 1.0 m in 27 . The performance of the MRCWPT system is improved by using metamaterial in the above work. However, the metamaterial is so thick and large that it limits the application of the system. The conventional metamaterial used for the MRCWPT system to improve the efficiency just works at only single frequency. Also, the research about metamaterial used for frequency reconfigurable magnetic resonant coupling wireless power transfer system is lacking. This paper presents a method for improving the efficiency of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system dynamically by using the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial at the different working frequency. The reconfigurability is achieved by adjusting the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor connected in the coil of the system. The conventional structures of the coil and the metamaterial are used in the system, so the universality of this method is further illustrated.

This paper is organized as follows. The theoretical analysis of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system is illustrated in “ Theoretical analysis of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system ” section. Frequency reconfigurable mechanism of the system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is derived by the equivalent circuit theory. Simulation of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system is presented in “ Simulation of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system ” section. The experimental results compared with simulation results of the MRCWPT system are illustrated in “ Measurement of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system ” section. Finally, conclusions are drawn in “ Conclusion ” section.

Theoretical analysis of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system

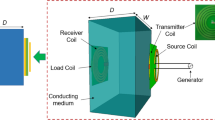

The frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is shown in Fig. 1 . The system includes a drive coil, a transmitter, a receiver, and a load coil. All the coil structures are square spiral coils because of simple fabrication and popular applications. The energy is transmitted from the transmitter to the receiver through the electromagnetic field. The metamaterial shown in Fig. 1 is used to manipulate the direction of the electromagnetic field of the system to enhance the PTE of the system. The variable d represents the distance between the receiver and the transmitter. The variable l represents the distance between the transmitter and the metamaterial. When the reconfigurable metamaterial works at the different frequency, the drive loop, the transmitter, the receiver, and the load loop need to be working at the same frequency with the metamaterial. The control method and strategy of the system is described as follows. The frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system is achieved by adjusting the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor (TZY2K450A001) connected in the coil of the system in this paper. There is a adjustable capacitor connected in the the drive loop, the transmitter, the receiver, and the load loop, respectively. And four identical adjustable capacitors connected in four coils of the metamaterial are used to achieve the frequency reconfigurability of the metamaterial by changing the capacitance value. The capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor is changed from 8 to 45 pf by adjusting the distance between the plate and the fixed plate with screws. When the reconfigurable metamaterial works at the different frequency by changing the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor (TZY2K450A001), the drive loop, the transmitter, the receiver, and the load loop need to be working at the same frequency with the metamaterial by changing the capacitance value of the identical adjustable capacitor (TZY2K450A001).

The frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial.

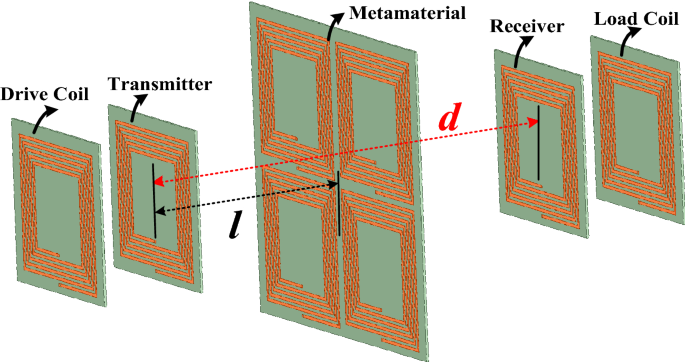

In order to clarify the proposed frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial clearly by using the equivalent lumped circuit model, the schematic structure of the coil unit cell can be modeled into the RLC resonant circuit. Top and bottom view of the coil unit cell are shown in Fig. 2 a and b, respectively. The circuit schematic of the coil unit cell is illustrated in Fig. 2 c, and the equivalent RLC resonant circuit of the coil structure is shown in Fig. 2 d. The equivalent inductance of the copper coil is L i , and the equivalent capacitance of the copper coil is C i . R i is the equivalent resistance in the equivalent RLC resonant circuit. When the capacitance value of the variable capacitor in Fig. 2 b changes, C i will change accordingly. The concrete dimension of the coil unit shown in Fig. 2 is illustrated in Table 1 .

( a ) Top and ( b ) bottom view of the coil unit cell, ( c ) the circuit schematic of the coil unit cell, ( d ) the equivalent RLC resonant circuit of the coil structure.

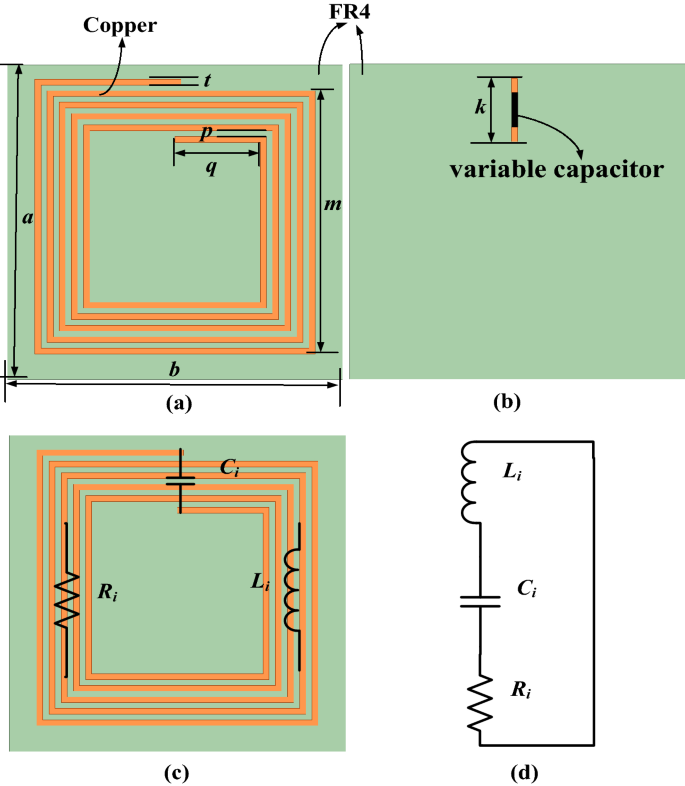

The frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is modeled by using the equivalent circuit theory. The equivalent circuit of the frequency reconfigurable system is presented in Fig. 3 . There are eight equivalent circuits corresponding to eight coil unit cells in the frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial. I i and Z i ( i = 1, 2, …, 4) represent the current and impedance of the coil unit cell of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial. I D , I R , I T , and I L represent the current of the drive coil, the receiver, the transmitter, and the load loop, respectively. Z D , Z R , Z T , and Z L are impedance of the drive coil, the receiver, the transmitter, and the load loop, respectively. L D , L T , L R , L L and L i are equivalent inductance. R D , R T , R R , R L and R i are equivalent resistances. C D , C T , C R , C L and C i are equivalent capacitance. The drive coil and the transmitter is connected by the mutual inductance M DT . The transmitter and the coil unit cell of the metamaterial is connected by the mutual inductance M T i . The drive coil and the coil unit cell of the metamaterial is connected by the mutual inductance M D i . The coil unit cell of the metamaterial and the receiver is connected by the mutual inductance M R i . The coil unit cell of the metamaterial and the load coil is connected by the mutual inductance M Li . The load coil and the receiver is connected by the mutual inductance M RL . In Fig. 3 , the source has the voltage of V S and impedance of R S . R load is connected with the load coil. The variable w represents the resonant frequency of the system.

The equivalent circuit of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial.

According to the Kirchhoff’s voltage law and the mutual coupling theory, equations of voltages and currents can be shown as follows:

The PTE of the system can be calculated by using the scattering parameter | S 21 | by PTE =| S 21 | 2 .

Simulation of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system

The frequency reconfigurable metamaterial.

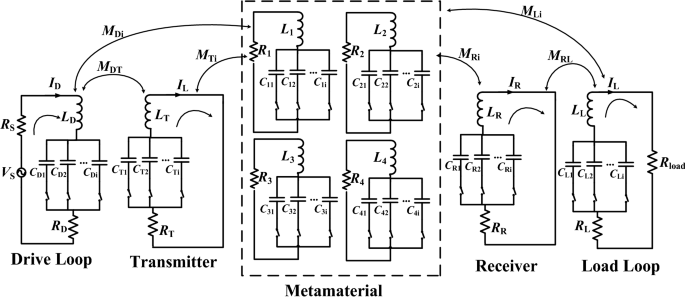

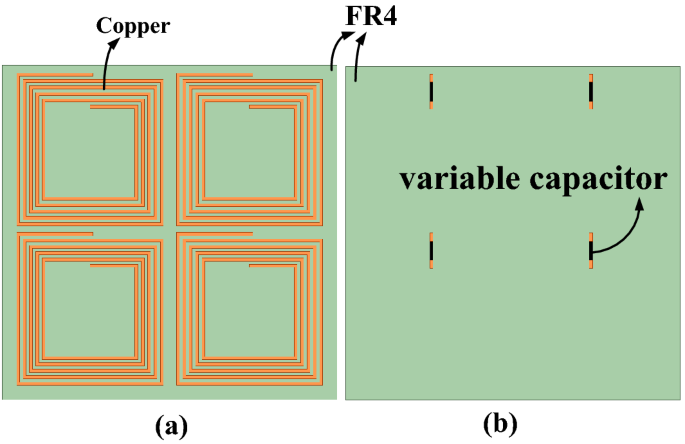

The frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is used to enhance PTE of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system. Top and bottom view of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are shown in Fig. 4 a and b, respectively. There are four copper coil unit cells on the FR4 dielectric substrate. And four identical adjustable capacitors connected in four coils are used to achieve the reconfigurability of the metamaterial by changing their capacitance value.

( a ) Top and ( b ) bottom view of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial.

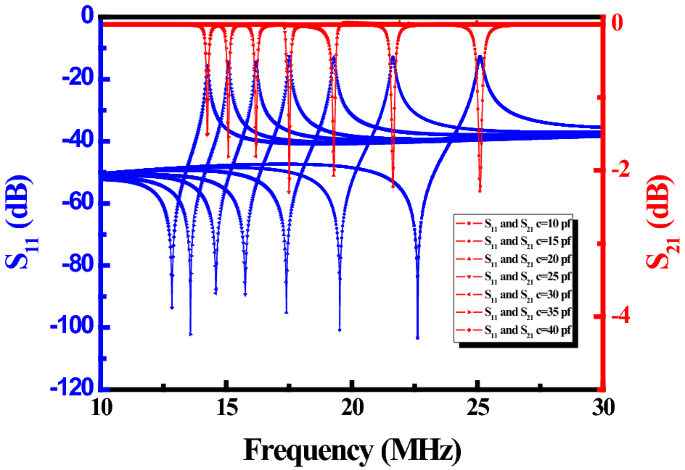

By changing the capacitance value of the adjustable capacitor, the reflection loss S 11 and the transmission coefficient S 21 of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial at different frequencies are illustrated in Fig. 5 . The parameters of the reflection loss S 11 and transmission coefficient S 21 changes dramatically at different frequency bands, which indicates that the metamaterial has some special electromagnetic characteristics at this frequency band. The ultra-thin frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is designed at the different working frequency of 14.1 MHz, 15 MHz, 16.2 MHz, 17.5 MHz, 19.3 MHz, 21.7 MHz and 25 MHz to enhance the magnetic field and PTE of the system.

The reflection loss S 11 and transmission coefficient S 21 of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial at different frequencies.

The general approach to the retrieval of material parameters from S parameters for homogeneous materials is outlined as follows. For the sake of generality, it is useful to first define the one-dimensional transfer matrix, which relates the fields on one side of a planar slab to the other. The transfer matrix can be defined from

E and H red are the complex electric and magnetic field amplitudes located on the right-hand and left-hand faces of the slab. Note that the magnetic field assumed throughout is a reduced magnetic field having the normalization \(H_{red} = ( + i{\text{w}}\mu_{0} )H\) . The transfer matrix for a homogeneous 1D slab has the analytic form.

where n is the refractive index and z is the wave impedance of the slab. n and z are related to the effective permeability μ by the relation

The total field amplitudes are not conveniently probed in measurements, whereas the scattered field amplitudes and phases can be measured in a straightforward manner. A scattering S matrix relates the incoming field amplitudes to the outgoing field amplitudes, and can be directly related to experimentally determined quantities. The elements of the S matrix can be found from the elements of the T matrix as follows:

For a slab of homogeneous material, T11=T22=Ts and det (T)=1, and the S matrix is symmetric. Thus,

Using the analytic expression for the T -matrix elements gives the S parameter

Equations can be inverted to find n and z in terms of the scattering parameters as follows:

Therefore, the effective permeability can be obtained with S 11 and S 21 .

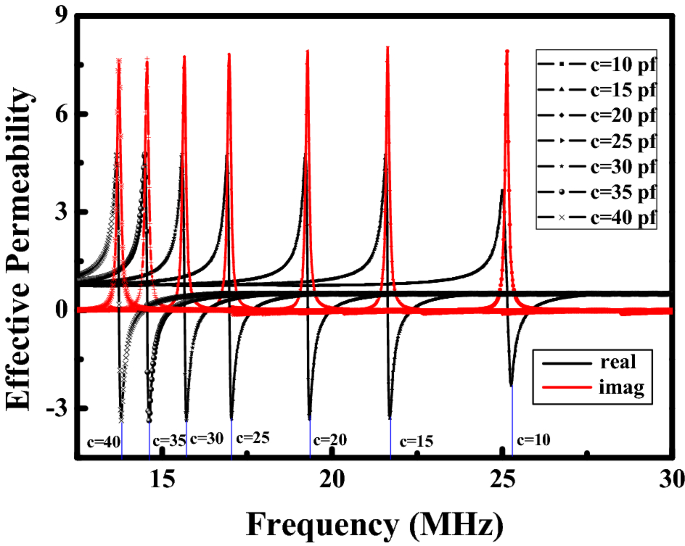

The parameter extraction method is adopted to calculate the effective permeability of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial according to the reflection loss S 11 and the transmission coefficient S 21 in Fig. 5 . The effective permeability of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial at different frequencies is shown in Fig. 6 . The red curve in Fig. 6 represents the imaginary part of the effective permeability. The black curve represent the real part of the effective permeability. The effective permeability of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is negative at the different resonant frequency.

The effective permeability of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial at different frequencies.

The location optimization of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial

The frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is located between the transmitter and the receiver as shown in Fig. 1 . The distance between the metamaterial and the transmitter is l . In order to enhance PTE of the wireless power transfer system, the distance l between the transmitter and the metamaterial should be optimized. The PTE of the wireless power transfer system at the different distance between the transmitter and the metamaterial is presented in Fig. 7 . The distance d between the transmitter and the receiver is 120 mm. The distance l between the transmitter and the metamaterial varies from 10 to 110 mm. When the distance l is 110 mm, the distance between the metamaterial and the receiver is 10 mm. Due to the system symmetry, it can be seen that the efficiency of the system at 10 mm is high and also at 110 mm distance is high. It is shown that the PTE is 77% at the distance of 10 mm and 110 mm. And the PTE at the distance is higher than the PTE at the other different distance. Therefore, the optimized distance between the transmitter and the metamaterial is 10 mm.

The PTE of the system at the different distance between the transmitter and the metamaterial.

The magnetic field distribution of the system

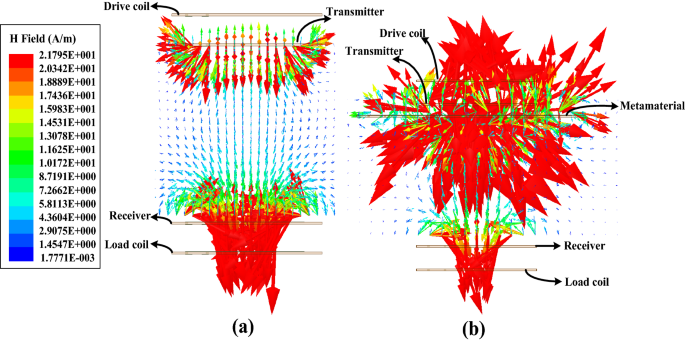

The magnetic field distribution of the system without the metamaterial and the magnetic field distribution of the system with the metamaterial are presented in Fig. 8 a and b, respectively. The magnetic field distribution of the system is shown to better understand the coupling between the transmitter and the receiver. It is shown that the coupling between the transmitter and the receiver with the metamaterial is better than the coupling between the transmitter and the receiver without the metamaterial. Therefore, the metamaterial can be used to manipulate the direction of the electromagnetic field of the system due to its abnormal effective permeability.

( a ) The magnetic field distribution of the system without the metamaterial, ( b ) The magnetic field distribution of the system with the metamaterial.

Measurement of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system

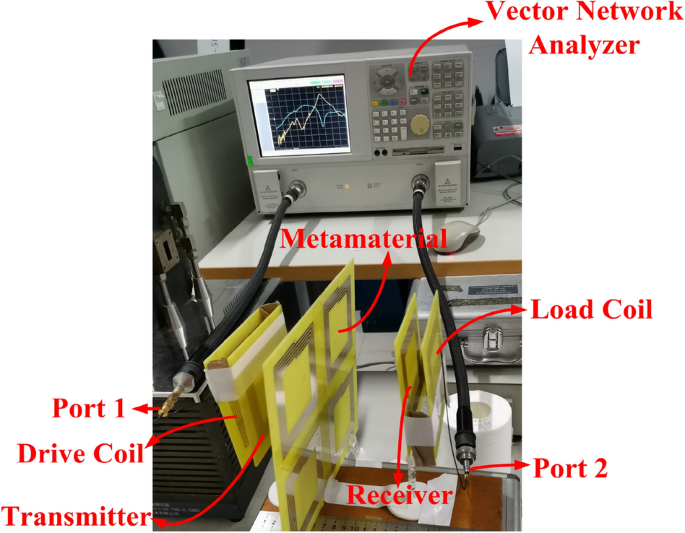

The coils and the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are fabricated by using parameters shown in Table 2 to verify the correctness of the simulation results of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system. The experimental platform of the frequency reconfigurable wireless power transfer system is presented in Fig. 9 . The drive coil and the load coil are connected to the port 1 and the port 2 of the vector network analyzer (Agilent Technologies N5230A), respectively. The drive coil is fixed in a certain position, and the transmitter, the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial, the receiver and the load coil are placed in a coaxial position of the load coil. PTE of the MRCWPT system is calculated by using the equation in 29

The experimental platform of the frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system.

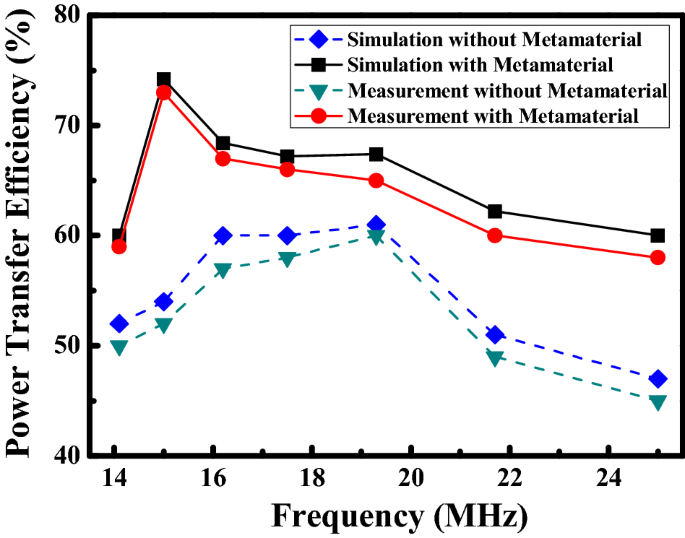

To verify the enhancement of the MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial, the MRCWPT system with and without the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are carried out by the experiments, respectively. PTE of the MRCWPT system at the different frequency with and without the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are presented in Fig. 10 . Obviously, PTE of the MRCWPT system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is higher than PTE of the system without the metamaterial. PTE of the system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are 59%, 73%, 67%, 66%, 65%, 60% and 58% at different frequencies of 14.1 MHz, 15 MHz, 16.2 MHz, 17.5 MHz, 19.3 MHz, 21.7 MHz and 25 MHz, respectively.

Simulated and measured PTE at the different frequency with and without metamaterial.

Simulated and measured PTE of the wireless power transfer system at the different transmission distance with and without the metamaterial are presented in Fig. 11 . Measurement results of the system agree well with simulation results. The deviation may be due to the practical fabrication and measurement errors. The PTE of the wireless power transfer system is improved obviously at the different transmission distance by using the metamaterial. The results indicate that high PTE of the MRCWPT system is carried out by using the metamaterial as the magnetic flux guide. PTE of the system with and without the metamaterial is 72% and 49% at the distance of 120 mm and the frequency of 15 MHz, respectively. Experiment results intuitively verify that PTE of the MRCWPT system is indeed enhanced significantly by using the metamaterial.

PTE of the wireless power transfer system at the different transmission distance with and without metamaterial.

A frequency reconfigurable MRCWPT system with enhanced efficiency by using the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is presented in this paper. Frequency reconfigurable mechanism of the system with the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial is derived by the equivalent circuit theory. Finite element simulation results have shown that the frequency reconfigurable electromagnetic metamaterial can manipulate the direction of the electromagnetic field of the system due to its abnormal effective permeability. The location optimization of the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial shows that the optimized distance between the transmitter and the metamaterial is 10 mm. Further measurement which verifies the simulation by reasonable agreement is carried out. PTE of the system by adding the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial are 59%, 73%, 67%, 66%, 65%, 60% and 58% at different working frequencies of 14.1 MHz, 15 MHz, 16.2 MHz, 17.5 MHz, 19.3 MHz, 21.7 MHz and 25 MHz, respectively. PTE of the system with and without the metamaterial is 72% and 49% at the distance of 120 mm and the frequency of 15 MHz, respectively. PTE is improved obviously at the different frequency and the different transmission distance by using the frequency reconfigurable metamaterial.

Li, Y., Zhang, L., Zhao, T., Zou, L., The electromagnetic compatibility analysis of experimental apparatus based on wireless power transmission. IEEE Indust. Electron. Appl. , pp 2334–2338, (2016).

Kuo, N.-C., Zhao, B. & Niknejad, A. M. Bifurcation analysis in weakly coupled inductive power transfer systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Papers 63 , 727–738 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Zhang, Z., Pang, H., Georgiadis, A. & Cecati, C. Wireless power transfer—An overview. IEEE Trans. Indust. Electron. 66 (2), 1044–1058 (2019).

Zhang, C. & Chen, Y. ‘Wireless power transfer strategies for cooperative relay system to maximize information throughput’. IEEE Access 5 , 2573–2582 (2017).

Hoang, H., Lee, S., Kim, Y., Choi, Y. & Bien, F. An adaptive technique to improve wireless power transfer for consumer electronics. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 58 , 327–332 (2012).

Kurs, A. et al. Wireless power transfer via strongly coupled magnetic resonances. Science 317 , 83–86 (2007).

Article MathSciNet CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Basar, M. R., Ahmadm, M. Y., Cho, J. & Ibrahim, F. ‘Stable and high efficiency wireless power transfer system for robotic capsule using a modified helmholtz coil’. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64 , 1113–1122 (2017).

Yedavalli, P. S., Riihonen, T., Wang, X. & Rabaey, J. M. ‘Far-field RF wireless power transfer with blind adaptive beam forming for Internet of Things devices’. IEEE Access 5 , 1743–1752 (2017).

Monti, G., Che, W., Wang, Q., Costanzo, A. & Chang, Y. Wireless power transfer with three-ports networks: Optimal analytical solutions. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Papers 64 , 494–503 (2017).

Choi, J., Cho, J. K., and Seo, C., Analysis on transmission efficiency of wireless energy transmission resonator based on magnetic resonance. IEEE Microwave Workshop Ser. Innovat. Wireless Power Trans. Technol. , pp. 199–202, (2011).

Kim, J.-M., Han, M. & Sohn, H. Magnetic resonance-based wireless power transmission through concrete structures. J. Electromagn. Eng. Sci. 15 , 104–110 (2015).

Ngo, T., Huang, A. & Guo, Y. Analysis and design of a reconfigurable rectifier circuit for wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 66 (9), 7089–7098 (2019).

Dai, Z., Fang, Z., Huang, H., He, Y. & Wang, J. Selective omnidirectional magnetic resonant coupling wireless power transfer with multiple-receiver system. IEEE Access 6 , 19287–19294 (2018).

Duong, T. P. & Lee, J. W. Experimental results of high-efficiency resonant coupling wireless power transfer using a variable coupling method. IEEE Microw. Wireless Compon. Lett. 8 , 442–444 (2011).

Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Li, J. & Zhao, H. A shape-reconfigurable modularized wireless power transfer array system for multipurpose wireless charging applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 66 , 4252–4259 (2016).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Wu, L. & Zhang, B. Reconfigurable transmitter coil structure for highly efficient and misalignment-insensitive wireless power transfer systems in megahertz range. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 5 (2), 56–62 (2019).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Lee, W. & Yoon, Y.-K. Tunable metamaterial slab for efficiency improvement in misaligned wireless power transfer. IEEE Microwave Wirel. Compon. Lett. 30 (9), 912–915 (2020).

Ahn, D. & Hong, S. A study on magnetic field repeater in wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 60 (1), 360–371 (2013).

Wang, H., Wang, W., Chen, X., Li, Q. & Zhang, Z. Analysis and design of khz-metamaterial for wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Magn. 56 (8), 1–5 (2020).

Google Scholar

Liu, J., Chen, Z., Zhou, J. and Sun, H., Compact triplex-layer metamaterials design for wireless power transfer efficiency enhancement. 2020 IEEE 19th Biennial Conference on Electromagnetic Field Computation (CEFC), 1–4, (2020).

Pham, T. S., Ranaweera, A. K., Lam, V. D. & Lee, J. W. Experiments on localized wireless power transmission using a magneto-inductive wave two-dimensional metamaterial cavity. Appl. Phys. Exp. 9 , 044101 (2016).

Chabalko, M. J., Besnoff, J. & Ricketts, D. S. Magnetic field enhancement in wireless power with metamaterials and magnetic resonant couplers. IEEE Antenna Wireless Propag. Lett. 15 , 452–455 (2016).

Wang, B. et al. Experiments on wireless power transfer with metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98 (25), 254101 (2011).

Jia, L. and Fujimori, K. (2021) Improvement of transmission efficiency by using annular array metamaterial for magnetic coupling wireless power transmission system. 2020 International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation (ISAP), pp. 735–736, (2021).

Wang, B., Yerazunis, W. & Teo, K. H. Wireless power transfer: Metamaterials and array of coupled resonators. Proc. IEEE 101 (6), 1359–1368 (2013).

Lee, S. et al., High efficiency wireless power transfer system using a two-stack hybrid metamaterial slab. 2019 IEEE Wireless Power Transfer Conference (WPTC), pp. 616–619, (2019).

Ranaweera, A. L. A. K., Doung, T. P. & Lee, J. W. Experimental investigation of compact metamaterial for high efficiency midrange wireless power transfer applications. J. Appl. Phys. 116 (4), 043914 (2014).

Ranaweera, A. L. A. K., Moscoso, C. A. & Lee, J. W. Anisotropic metamaterial for efficiency enhancement of mid-range wireless power transfer under coil misalignment. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 48 (45), 455104 (2015).

Sample, A. P., Meyer, D. A. & Smith, J. R. Analysis, experimental results, and range adaptation of magnetically coupled resonators for wireless power transfer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 58 (2), 544–554 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the scientific research project of Hunan provincial health commission 2019 (C2019174).

The scientific research project of Hunan provincial health commission 2019, C2019174.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Postdoctoral Research Station of Clinical Medicine and Department of Oncology Radiotherapy Center, The 3Rd Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, 410000, China

Dongyong Shan & Ke Cao

Department of Blood Transfusion, The Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, 410013, China

Junhua Zhang

School of Physics and Electronics, Central South University, Changsha, 410083, China

Haiyue Wang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.S. proposed the main idea. J.Z. and H.W. checked and discussed the results and the whole manuscript. K.C. contributed to the discussion of this study. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Junhua Zhang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shan, D., Wang, H., Cao, K. et al. Wireless power transfer system with enhanced efficiency by using frequency reconfigurable metamaterial. Sci Rep 12 , 331 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03570-8

Download citation

Received : 08 August 2021

Accepted : 29 November 2021

Published : 10 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03570-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Harnessing metamaterials for efficient wireless power transfer for implantable medical devices.

- Sultan Mahmud

- Ali Nezaratizadeh

- Adam Khalifa

Bioelectronic Medicine (2024)

Optimization of magnetic coupling mechanism of dynamic wireless power transfer based on NSGA-II algorithm

- Weihang Tang

- Hongbin Liao

Scientific Reports (2024)

Multifunctional coil technique for alignment-agnostic and Rx coil size-insensitive efficiency enhancement for wireless power transfer applications

- Seoyeon Yoon

- Yongshik Lee

Scientific Reports (2023)

A Metamaterial Inspired Low-Scattering Electric Quadrupole Antenna

- V. P. Sarin

- Rohith K. Raj

- Kesavath Vasudevan

Wireless Personal Communications (2023)

Homogenization of the vertically stacked medium frequency magnetic metamaterials with multi-turn resonators

- Adam Steckiewicz

Scientific Reports (2022)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- in IES journals

- in IES conferences

- from IES journals

- from IES conferences

- from IES technical committees

- Tutorials & Webinars

- eNewsLetter

- Editorial Board

Wireless Power Transfer – An Overview

Authors: Zhen Zhang; Hongliang Pang; Apostolos Georgiadis; Carlo Cecati

Extended Abstract:

The paper entitled: Wireless Power Transfer – An Overview, has overviewed the WPT techniques, with emphasis on fundamentals, technical challenges, metamaterials, and typical applications. The manuscript firstly introduced the working mechanism of inductive power transfer (IPT) systems, then, it compared four typical capacitive compensation networks, and elaborated the magnetic resonant coupling effect as well as the capacitive coupled power transfer (CCPT) mechanism. Then, it has given the answers to two technical questions, namely

- why the 2-coils IPT system is commonly used for short-range (shorter than the coil diameter) transmission ?

- and why the 4-coils IPT system can extend the transmission distance to the mid-range applications ?

The key technical issues of WPT systems have been summarized in terms of the efficiency, power, distance, misalignment, omni-directional charging, and energy security. In addition, it also offered a survey on the studies of metamaterial-based WPT systems. Lastly, some typical applications have also been discussed, including EVs, biomedical implants, and the portable electronics. By overviewing the development and the current state over past years, this paper is expected to offer readers a big image of WPT techniques based on the inductive coupling effect of non-radiative electromagnetic field. This emerging energy transmission mechanism shows significant meanings on the pervasive application of renewable energies in our daily life.

Meanwhile, a discussion about potential future developments are also given in this paper as follows:

- Transmission distance, which will be the most important concern for both researchers and end-users. A real WPT system should harness e the energy over a long distance rather than the wireless-but-contact charging style. However, a long distance means extremely loosely coupling effect for electromagnetic WPT systems. How to break through this technical bottleneck will be the focus of attention in near future.

- Energy security: as similarity with the development of wireless communication, the security of energy will be another key technical challenge for the further development of WPT systems. Regarding to the IPT system, the energy is transmitted via the open electromagnetic field. In other word, it is possible for all involved receptors to access the energy. Then, how to protect the wirelessly-transmitted energy will be an inevitable research topic.

- Bidirectional exchange: as one of typical applications, EVs will be further developed and wide popularized, even completely replacing the conventional internal combustion engine vehicles. In such a case, the energy acquisition will be increasingly important for EVs. As aforementioned, in addition, the V2G technique can make EVs as movable energy buffers, which can effectively balance the power supply and the load. Thus, the bidirectional EV wireless charging will be next hot research topic after the roadway-powering mechanism.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 51977138), in part by the Humboldt Research Fellowship (Ref 3.5-CHN-1201512-HFST-P), and in part by Project MISE-PON n.F/050220/01-02-03/X32 and n. F/190042/02/X44

2020 Outstanding paper award for IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics

Check full paper at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8357386.

Research on resonance based wireless energy transfer device for small mobile equipments

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- Create Account

Main navigation dropdown

Publications, wireless energy transfer in future networks, publication date, manuscript submission deadline, 18 august 2021, call for papers.

With 5G starting to be commercially deployed, research in 6G mobile networks has started. One of the major key performance indicators for 6G is its extremely massive connectivity for small devices to enable the so-called Internet of Everything (IoE). Most of these IoE devices will be either battery-powered or battery-less. How to prolong the lifetime of these IoE devices becomes a key challenge. This calls for effort into two complementary areas: 1) energy efficiency to reduce IoE device’s energy consumption and 2) wireless energy transfer (WET) to open up new avenues to provide energy to IoE devices. The former area has been intensively researched under the banner of green communications. It is envisioned that 6G will utilize this research and provide WET to massive IoE devices. Emerging 6G technologies such as THz and intelligent reflective surface (IRS) provide great potential to fulfil this vision of WET. For instance, higher THz frequencies will provide better directionality which is more efficient for WET. Intelligent surfaces may be used actively or passively (using backscattering technique) to transmit or relay signals to IoE devices, enabling battery-less devices. IRS may also be manipulated to enable on-demand WET.

This Feature Topic (FT) solicits papers focusing on wireless energy transfer for IoE devices , in terms of both the infrastructure aspect and the device aspect. Areas of interest include, but are not limited to the following:

- Network architecture to support wireless energy transfer (WET) of IoE devices in future wireless networks

- Protocol and resource allocation algorithms to support WET

- Energy efficient THz-based transceiver design for joint information and energy transfer

- Visible light based transceiver design for joint information and energy transfer

- Battery-less massive access

- Prototype and experimental work for IoE device WET

Submission Guidelines

Manuscripts should conform to the standard format as indicated in the Information for Authors section of the Manuscript Submission Guidelines . Please, check these guidelines carefully before submitting since submissions not complying with them will be administratively rejected without review.

All manuscripts to be considered for publication must be submitted by the deadline through Manuscript Central . Select the “Mar2022/Wireless Energy Transfer” topic from the drop-down menu of Topic/Series titles. Please observe the dates specified here below noting that there will be no extension of submission deadline.

Important Dates

Manuscript Submission Deadline : 15 August 2021, 3:00 pm US Eastern Time - extended to 18 August 2021, 3:00 pm US Eastern Time Decision Notification : 15 November, 2021 Final Manuscript Due : 1 January 2022 Publication Date : March 2022

Guest Editors

Kun Yang University of Essex, UK

Jie Hu University of Electronic Sci. and Technology of China (UESTC), China

Burak Kantarci University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Share this page:

Energy Efficient Wireless Communications with Energy Harvesting and Wireless Power Transfer

Submission Deadline: 15 September 2017

IEEE Access invites manuscript submissions in the area of Energy Efficient Wireless Communications with Energy Harvesting and Wireless Power Transfer.

With technological advancements, future wireless communications networks are expected to incorporate densely deployed base stations serving tens of billions of low-power wireless devices, in order to enable the emerging Internet-of-things (IoT) applications. However, this leads to a dramatic increase in energy cost at the wireless networks, and makes it a difficult task to efficiently power massive wireless devices. Therefore, how to reduce the energy cost at the network side and how to provide sustainable energy supply at the wireless device side become two increasingly important issues for the success of IoT. Recently, energy harvesting (EH) from ambient sources (e.g., solar and wind) and dedicated wireless power transfer via radio frequency (RF) signals have emerged as appealing solutions to power base stations and low-power wireless devices. Such techniques have several promising advantages over the traditional grid/battery-powered systems, such as improved energy efficiency, reduced energy and maintenance costs, prolonged lifetime, and even perpetual and uninterrupted operations. Hence, EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications have attracted significant interests recently from both academia and industry.

Different from the conventional fixed and stable energy supplies, such as the grid and the battery, the EH from ambient sources is usually random and intermittent with time-varying energy arrival rate. On the other hand, the end-to-end power transfer efficiency of wireless power transfer is rather limited due to the severe path-loss and fading of wireless channels. Therefore, the integration of these new energy techniques brings new challenges and opportunities in wireless communications networks, and calls for a paradigm shift on joint energy and information management, by taking into account the unique characteristics of ambient energy sources and wireless power transfer. As a result, numerous new research problems need to be addressed from multiple technique aspects across communication theory, information theory, circuit theory, signal processing, and optimization.

This Special Section in IEEE Access will focus on various theoretical and practical design issues for EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications, aiming at bringing together researchers, industry practitioners, and individuals working on the related areas to share their new ideas, latest findings, and state-of-the-art results. Comprehensive surveys and original technical contributions, which are not published previously and not under review by another journal currently, are solicited in the relevant topics including, but not limited to, the following:

- Trends and challenges for EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications

- Cognitive radio networks with EH and wireless power transfer

- Relay channels with EH and wireless power transfer

- Mobile edge networks with EH and wireless power transfer

- Multi-antenna EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications

- Full-duplex EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications

- Security issues in EH wireless communications and wireless powered communications

- Offline and online power allocation in EH wireless communications

- Joint energy and communication cooperation

- Communications and signals design for wireless power transfer

- Simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT)

- Wireless powered communication networks

- Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) with SWIPT

We also highly recommend the submission of multimedia with each article as it significantly increases the visibility, downloads, and citations of articles.

Associate Editor: Jie Xu, Guangdong University of Technology, China

Guest Editors:

- Bruno Clerckx, Imperial College London, UK

- Zhiguo Ding, Lancaster University, UK

- Xin Wang, Fudan University, China

- Yong Zeng, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Relevant IEEE Access Special Sections:

- Exploiting the Benefits of Interference in Wireless Networks: Energy Harvesting and Security

- Energy Harvesting and Scavenging: Technologies, Algorithms, and Communication Protocols

- Resource Management in Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks: Energy Management, Communication Protocol and Future Applications

IEEE Access Editor-in-Chief: Michael Pecht, Professor and Director, CALCE, University of Maryland

Paper submission: Contact Associate Editor and submit manuscript to: http://ieee.atyponrex.com/journal/ieee-access

For inquiries regarding this Special Section, please contact: [email protected]

At a Glance

- Journal: IEEE Access

- Format: Open Access

- Frequency: Continuous

- Submission to Publication: 4-6 weeks (typical)

- Topics: All topics in IEEE

- Average Acceptance Rate: 27%

- Impact Factor: 3.9

- Model: Binary Peer Review

- Article Processing Charge: US $1,995

Featured Articles

DNN Partitioning for Inference Throughput Acceleration at the Edge

View in IEEE Xplore

Effect of Data Characteristics Inconsistency on Medium and Long-Term Runoff Forecasting by Machine Learning

Reducing Losses and Energy Storage Requirements of Modular Multilevel Converters With Optimal Harmonic Injection

Submission guidelines.

© 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this website signifies your agreement to the IEEE TERMS AND CONDITIONS.

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world’s largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity.

AWARD RULES:

NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING.

These rules apply to the “2024 IEEE Access Best Video Award Part 1″ (the “Award”).

- Sponsor: The Sponsor of the Award is The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Incorporated (“IEEE”) on behalf of IEEE Access , 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854-4141 USA (“Sponsor”).

- Eligibility: Award is open to residents of the United States of America and other countries, where permitted by local law, who are the age of eighteen (18) and older. Employees of Sponsor, its agents, affiliates and their immediate families are not eligible to enter Award. The Award is subject to all applicable state, local, federal and national laws and regulations. Entrants may be subject to rules imposed by their institution or employer relative to their participation in Awards and should check with their institution or employer for any relevant policies. Void in locations and countries where prohibited by law.

- Agreement to Official Rules : By participating in this Award, entrants agree to abide by the terms and conditions thereof as established by Sponsor. Sponsor reserves the right to alter any of these Official Rules at any time and for any reason. All decisions made by Sponsor concerning the Award including, but not limited to the cancellation of the Award, shall be final and at its sole discretion.

- How to Enter: This Award opens on January 1, 2024 at 12:00 AM ET and all entries must be received by 11:59 PM ET on June 30, 2024 (“Promotional Period”).

Entrant must submit a video with an article submission to IEEE Access . The video submission must clearly be relevant to the submitted manuscript. Only videos that accompany an article that is accepted for publication in IEEE Access will qualify. The video may be simulations, demonstrations, or interviews with other experts, for example. Your video file should not exceed 100 MB.

Entrants can enter the Award during Promotional Period through the following method:

- The IEEE Author Portal : Entrants can upload their video entries while submitting their article through the IEEE Author Portal submission site .

- Review and Complete the Terms and Conditions: After submitting your manuscript and video through the IEEE Author Portal, entrants should then review and sign the Terms and Conditions .

Entrants who have already submitted a manuscript to IEEE Access without a video can still submit a video for inclusion in this Award so long as the video is submitted within 7 days of the article submission date. The video can be submitted via email to the article administrator. All videos must undergo peer review and be accepted along with the article submission. Videos may not be submitted after an article has already been accepted for publication.

The criteria for an article to be accepted for publication in IEEE Access are:

- The article must be original writing that enhances the existing body of knowledge in the given subject area. Original review articles and surveys are acceptable even if new data/concepts are not presented.

- Results reported must not have been submitted or published elsewhere (although expanded versions of conference publications are eligible for submission).

- Experiments, statistics, and other analyses must be performed to a high technical standard and are described in sufficient detail.

- Conclusions must be presented in an appropriate fashion and are supported by the data.

- The article must be written in standard English with correct grammar.

- Appropriate references to related prior published works must be included.

- The article must fall within the scope of IEEE Access

- Must be in compliance with the IEEE PSPB Operations Manual.

- Completion of the required IEEE intellectual property documents for publication.

- At the discretion of the IEEE Access Editor-in-Chief.

- Disqualification: The following items will disqualify a video from being considered a valid submission:

- The video is not original work.

- A video that is not accompanied with an article submission.

- The article and/or video is rejected during the peer review process.

- The article and/or video topic does not fit into the scope of IEEE Access .

- The article and/or do not follow the criteria for publication in IEEE Access .

- Videos posted in a comment on IEEE Xplore .

- Content is off-topic, offensive, obscene, indecent, abusive or threatening to others.

- Infringes the copyright, trademark or other right of any third party.

- Uploads viruses or other contaminating or destructive features.

- Is in violation of any applicable laws or regulations.

- Is not in English.

- Is not provided within the designated submission time.

- Entrant does not agree and sign the Terms and Conditions document.

Entries must be original. Entries that copy other entries, or the intellectual property of anyone other than the Entrant, may be removed by Sponsor and the Entrant may be disqualified. Sponsor reserves the right to remove any entry and disqualify any Entrant if the entry is deemed, in Sponsor’s sole discretion, to be inappropriate.

- Entrant’s Warranty and Authorization to Sponsor: By entering the Award, entrants warrant and represent that the Award Entry has been created and submitted by the Entrant. Entrant certifies that they have the ability to use any image, text, video, or other intellectual property they may upload and that Entrant has obtained all necessary permissions. IEEE shall not indemnify Entrant for any infringement, violation of publicity rights, or other civil or criminal violations. Entrant agrees to hold IEEE harmless for all actions related to the submission of an Entry. Entrants further represent and warrant, if they reside outside of the United States of America, that their participation in this Award and acceptance of a prize will not violate their local laws.

- Intellectual Property Rights: Entrant grants Sponsor an irrevocable, worldwide, royalty free license to use, reproduce, distribute, and display the Entry for any lawful purpose in all media whether now known or hereinafter created. This may include, but is not limited to, the IEEE A ccess website, the IEEE Access YouTube channel, the IEEE Access IEEE TV channel, IEEE Access social media sites (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, IEEE Access Collabratec Community), and the IEEE Access Xplore page. Facebook/Twitter/Microsite usernames will not be used in any promotional and advertising materials without the Entrants’ expressed approval.

- Number of Prizes Available, Prizes, Approximate Retail Value and Odds of winning Prizes: Two (2) promotional prizes of $350 USD Amazon gift cards. One (1) grand prize of a $500 USD Amazon gift card. Prizes will be distributed to the winners after the selection of winners is announced. Odds of winning a prize depend on the number of eligible entries received during the Promotional Period. Only the corresponding author of the submitted manuscript will receive the prize.

The grand prize winner may, at Sponsor’ discretion, have his/her article and video highlighted in media such as the IEEE Access Xplore page and the IEEE Access social media sites.

The prize(s) for the Award are being sponsored by IEEE. No cash in lieu of prize or substitution of prize permitted, except that Sponsor reserves the right to substitute a prize or prize component of equal or greater value in its sole discretion for any reason at time of award. Sponsor shall not be responsible for service obligations or warranty (if any) in relation to the prize(s). Prize may not be transferred prior to award. All other expenses associated with use of the prize, including, but not limited to local, state, or federal taxes on the Prize, are the sole responsibility of the winner. Winner(s) understand that delivery of a prize may be void where prohibited by law and agrees that Sponsor shall have no obligation to substitute an alternate prize when so prohibited. Amazon is not a sponsor or affiliated with this Award.

- Selection of Winners: Promotional prize winners will be selected based on entries received during the Promotional Period. The sponsor will utilize an Editorial Panel to vote on the best video submissions. Editorial Panel members are not eligible to participate in the Award. Entries will be ranked based on three (3) criteria:

- Presentation of Technical Content

- Quality of Video

Upon selecting a winner, the Sponsor will notify the winner via email. All potential winners will be notified via their email provided to the sponsor. Potential winners will have five (5) business days to respond after receiving initial prize notification or the prize may be forfeited and awarded to an alternate winner. Potential winners may be required to sign an affidavit of eligibility, a liability release, and a publicity release. If requested, these documents must be completed, signed, and returned within ten (10) business days from the date of issuance or the prize will be forfeited and may be awarded to an alternate winner. If prize or prize notification is returned as undeliverable or in the event of noncompliance with these Official Rules, prize will be forfeited and may be awarded to an alternate winner.

- General Prize Restrictions: No prize substitutions or transfer of prize permitted, except by the Sponsor. Import/Export taxes, VAT and country taxes on prizes are the sole responsibility of winners. Acceptance of a prize constitutes permission for the Sponsor and its designees to use winner’s name and likeness for advertising, promotional and other purposes in any and all media now and hereafter known without additional compensation unless prohibited by law. Winner acknowledges that neither Sponsor, Award Entities nor their directors, employees, or agents, have made nor are in any manner responsible or liable for any warranty, representation, or guarantee, express or implied, in fact or in law, relative to any prize, including but not limited to its quality, mechanical condition or fitness for a particular purpose. Any and all warranties and/or guarantees on a prize (if any) are subject to the respective manufacturers’ terms therefor, and winners agree to look solely to such manufacturers for any such warranty and/or guarantee.

11.Release, Publicity, and Privacy : By receipt of the Prize and/or, if requested, by signing an affidavit of eligibility and liability/publicity release, the Prize Winner consents to the use of his or her name, likeness, business name and address by Sponsor for advertising and promotional purposes, including but not limited to on Sponsor’s social media pages, without any additional compensation, except where prohibited. No entries will be returned. All entries become the property of Sponsor. The Prize Winner agrees to release and hold harmless Sponsor and its officers, directors, employees, affiliated companies, agents, successors and assigns from and against any claim or cause of action arising out of participation in the Award.

Sponsor assumes no responsibility for computer system, hardware, software or program malfunctions or other errors, failures, delayed computer transactions or network connections that are human or technical in nature, or for damaged, lost, late, illegible or misdirected entries; technical, hardware, software, electronic or telephone failures of any kind; lost or unavailable network connections; fraudulent, incomplete, garbled or delayed computer transmissions whether caused by Sponsor, the users, or by any of the equipment or programming associated with or utilized in this Award; or by any technical or human error that may occur in the processing of submissions or downloading, that may limit, delay or prevent an entrant’s ability to participate in the Award.

Sponsor reserves the right, in its sole discretion, to cancel or suspend this Award and award a prize from entries received up to the time of termination or suspension should virus, bugs or other causes beyond Sponsor’s control, unauthorized human intervention, malfunction, computer problems, phone line or network hardware or software malfunction, which, in the sole opinion of Sponsor, corrupt, compromise or materially affect the administration, fairness, security or proper play of the Award or proper submission of entries. Sponsor is not liable for any loss, injury or damage caused, whether directly or indirectly, in whole or in part, from downloading data or otherwise participating in this Award.

Representations and Warranties Regarding Entries: By submitting an Entry, you represent and warrant that your Entry does not and shall not comprise, contain, or describe, as determined in Sponsor’s sole discretion: (A) false statements or any misrepresentations of your affiliation with a person or entity; (B) personally identifying information about you or any other person; (C) statements or other content that is false, deceptive, misleading, scandalous, indecent, obscene, unlawful, defamatory, libelous, fraudulent, tortious, threatening, harassing, hateful, degrading, intimidating, or racially or ethnically offensive; (D) conduct that could be considered a criminal offense, could give rise to criminal or civil liability, or could violate any law; (E) any advertising, promotion or other solicitation, or any third party brand name or trademark; or (F) any virus, worm, Trojan horse, or other harmful code or component. By submitting an Entry, you represent and warrant that you own the full rights to the Entry and have obtained any and all necessary consents, permissions, approvals and licenses to submit the Entry and comply with all of these Official Rules, and that the submitted Entry is your sole original work, has not been previously published, released or distributed, and does not infringe any third-party rights or violate any laws or regulations.

12.Disputes: EACH ENTRANT AGREES THAT: (1) ANY AND ALL DISPUTES, CLAIMS, AND CAUSES OF ACTION ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THIS AWARD, OR ANY PRIZES AWARDED, SHALL BE RESOLVED INDIVIDUALLY, WITHOUT RESORTING TO ANY FORM OF CLASS ACTION, PURSUANT TO ARBITRATION CONDUCTED UNDER THE COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION RULES OF THE AMERICAN ARBITRATION ASSOCIATION THEN IN EFFECT, (2) ANY AND ALL CLAIMS, JUDGMENTS AND AWARDS SHALL BE LIMITED TO ACTUAL OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS INCURRED, INCLUDING COSTS ASSOCIATED WITH ENTERING THIS AWARD, BUT IN NO EVENT ATTORNEYS’ FEES; AND (3) UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES WILL ANY ENTRANT BE PERMITTED TO OBTAIN AWARDS FOR, AND ENTRANT HEREBY WAIVES ALL RIGHTS TO CLAIM, PUNITIVE, INCIDENTAL, AND CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, AND ANY OTHER DAMAGES, OTHER THAN FOR ACTUAL OUT-OF-POCKET EXPENSES, AND ANY AND ALL RIGHTS TO HAVE DAMAGES MULTIPLIED OR OTHERWISE INCREASED. ALL ISSUES AND QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE CONSTRUCTION, VALIDITY, INTERPRETATION AND ENFORCEABILITY OF THESE OFFICIAL RULES, OR THE RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS OF ENTRANT AND SPONSOR IN CONNECTION WITH THE AWARD, SHALL BE GOVERNED BY, AND CONSTRUED IN ACCORDANCE WITH, THE LAWS OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY, WITHOUT GIVING EFFECT TO ANY CHOICE OF LAW OR CONFLICT OF LAW, RULES OR PROVISIONS (WHETHER OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION) THAT WOULD CAUSE THE APPLICATION OF THE LAWS OF ANY JURISDICTION OTHER THAN THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. SPONSOR IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY TYPOGRAPHICAL OR OTHER ERROR IN THE PRINTING OF THE OFFER OR ADMINISTRATION OF THE AWARD OR IN THE ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE PRIZES.

- Limitation of Liability: The Sponsor, Award Entities and their respective parents, affiliates, divisions, licensees, subsidiaries, and advertising and promotion agencies, and each of the foregoing entities’ respective employees, officers, directors, shareholders and agents (the “Released Parties”) are not responsible for incorrect or inaccurate transfer of entry information, human error, technical malfunction, lost/delayed data transmissions, omission, interruption, deletion, defect, line failures of any telephone network, computer equipment, software or any combination thereof, inability to access web sites, damage to a user’s computer system (hardware and/or software) due to participation in this Award or any other problem or error that may occur. By entering, participants agree to release and hold harmless the Released Parties from and against any and all claims, actions and/or liability for injuries, loss or damage of any kind arising from or in connection with participation in and/or liability for injuries, loss or damage of any kind, to person or property, arising from or in connection with participation in and/or entry into this Award, participation is any Award-related activity or use of any prize won. Entry materials that have been tampered with or altered are void. If for any reason this Award is not capable of running as planned, or if this Award or any website associated therewith (or any portion thereof) becomes corrupted or does not allow the proper playing of this Award and processing of entries per these rules, or if infection by computer virus, bugs, tampering, unauthorized intervention, affect the administration, security, fairness, integrity, or proper conduct of this Award, Sponsor reserves the right, at its sole discretion, to disqualify any individual implicated in such action, and/or to cancel, terminate, modify or suspend this Award or any portion thereof, or to amend these rules without notice. In the event of a dispute as to who submitted an online entry, the entry will be deemed submitted by the authorized account holder the email address submitted at the time of entry. “Authorized Account Holder” is defined as the person assigned to an email address by an Internet access provider, online service provider or other organization responsible for assigning email addresses for the domain associated with the email address in question. Any attempt by an entrant or any other individual to deliberately damage any web site or undermine the legitimate operation of the Award is a violation of criminal and civil laws and should such an attempt be made, the Sponsor reserves the right to seek damages and other remedies from any such person to the fullest extent permitted by law. This Award is governed by the laws of the State of New Jersey and all entrants hereby submit to the exclusive jurisdiction of federal or state courts located in the State of New Jersey for the resolution of all claims and disputes. Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, G+, YouTube, IEEE Xplore , and IEEE TV are not sponsors nor affiliated with this Award.

- Award Results and Official Rules: To obtain the identity of the prize winner and/or a copy of these Official Rules, send a self-addressed stamped envelope to Kimberly Rybczynski, IEEE, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854-4141 USA.

- International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT)

- Mission & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Peer-Review Policy

- Publication Ethics Policy

- Journal Policies

- Join as Reviewer

- Conference Partners

- Call for Papers

- Journal Statistics – 2023-2024

- Submit Manuscript

- Journal Charges (APC)

- Register as Volunteer

- Upcoming Conferences

- CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS

- Thesis Archive

- Thesis Publication FAQs

- Thesis Publication Charges

- Author Login

- Reviewer Login

SAETM-24 (Volume 12 - Issue 03)

Wireless power transfer system by using optical technology for electric vehicles.

- Article Download / Views: 1

- Authors : C.Alakesan, P.Hemalatha, S.Shanthiya, M.Vaishnavi

- Paper ID : IJERTCONV12IS03081

- Volume & Issue : Volume 12, Issue 03 (March 2023)

- Published (First Online): 24-05-2024

- ISSN (Online) : 2278-0181

- Publisher Name : IJERT

Abstract This research introduces a dynamic Optical Wireless Power Transfer (OWPT) system for charging both aerial and ground electric vehicles (EVs). Laser transmitters installed on an overhead facility track and charge vehicles continuously using tracking cameras. Analytical formulas are developed to analyze power and energy transmission, demonstrating the existence of maximum points inversely dependent on environmental conditions. Numerical simulations validate the theoretical findings. The study suggests design implications for ground EVs, highlighting the superiority of the dynamic OWPT system over other wireless transfer technologies. This innovation promises efficient, weather-resilient charging solutions for EVs, enhancing sustainability in transportation.

Keywords Dynamic OWPT, Wireless Charging, Laser Transmitters, Renewable Energy, Tracking Cameras, Analytical Formulas, Maximum Power, Environmental Attenuation, Numerical Simulations, Ground EV Design, Comparative Analysis

Introduction

The imperative to address global warming has become a key driver for promoting the widespread adoption of Electric Vehicles . As per the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development , the transportation sector, responsible for over 50% of global oil consumption, contributes to approximately 20% of worldwide carbon dioxide emissions. Consequently, the transportation sector emerges as a primary focus for countries' climate change mitigation policies. In response to mounting environmental apprehensions regarding CO2-induced global warming, policymakers are actively advocating for the adoption of electrified vehicles (EVs) as a strategic measure to curtail these emissions.

The EV Volumes database site records a notable surge in global Electric Vehicle (EV) and Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) sales, reaching 2.1 million units in 2018, reflecting a substantial 64% year-over-year increase and accounting for a 2.2% market share for the year. This rapid adoption is attributed to pivotal factors such as advancements in battery technology, including enhanced energy density, lifespan, and safety, along with significant cost reductions in batteries and power electronics. Additionally, the emergence of Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) in recent years has opened new possibilities.

This report will delve into the discussion of candidate Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) techniques suitable for high-power, near-field wireless Electric Vehicle (EV) applications. A more detailed exploration of these techniques will be presented in a subsequent section of the report.

Power electronics technology is integral to various aspects of Electric Vehicles (EVs) and their chargers, demanding bidirectional capability and grid-forming control for the battery charger, thereby contributing to increased design costs. This functionality enables the battery and charger to collaboratively establish a local microgrid. Nevertheless, a promising alternative solution to address plug-in concerns for charging EVs is the implementation of wireless electric vehicle charging systems (WEVCS).

Therefore, the discussion of Wireless Electric Vehicle Charging Systems (WEVCS) begins by placing initial emphasis on Wireless Power Transfer (WPT). In the operational context of Electric Vehicles (EVs), the BMS becomes indispensable for monitoring battery parameters, including current, voltage, and temperature. Moreover, simultaneous charging of a large number of EVs can lead to utility supply issues, such as deviations in line voltage and frequency, an increase in total harmonic distortion in the line current, and a surge in peak load on the utility.

I.Wireless Power Transfer (WPT)

The transmission of electrical energy from a power source to an electrical load across an air gap, eliminating the need for wires or connectors, characterizes Wireless Power Transfer technology. The essential components of a WPT system encompass the transmitter and receiver coils. Recently, WPT has regained prominence as a viable technology and has undergone extensive investigation and development. Various methods for electrical power transfer, such as capacitive-based WPTs and inductively coupled WPTs, exist. Notably, among these methods, inductively coupled WPTs have emerged as the most widely applied and utilized by researchers.

A.WPT Concept

Figure 2 shows the block diagram of a basic structure of the typical WPT system which consists of several stages to

Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) System

Inductive coupling

Without magnetic core

With magnetic cores on receiver side

With magnetic core

Capacitive coupling

Fig. 1. Classification of WPT system.

wirelessly transfer power from the supply to the load. The key components of the Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) system can be summarized as follows:

The loosely coupled transmitting and receiving coils.

The compensation networks.

The power electronics converters and control electronics.

To attain such high levels of effectiveness, each stage of the system had to function at a 97-98% efficiency level or higher. Achieving this performance required meticulous design to minimize losses at each stage. Nevertheless, in lower power applications, feasibilities of over 80% efficiency and coil-to-coil efficiencies (power transfer efficiency between the transmitter and reception coils) of 90% or more were attainable. [5].

Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) technology holds the promise of eliminating traditional cable connectors or physical connections, ushering in new levels of convenience for the charging of millions of everyday electronic devices. [6], [9]. WPT brings an additional advantage of reducing costs related to the maintenance of direct connectors. It ensures safe power transfer to applications requiring sterility or hermetic sealing while providing robust and consistent power delivery to rotating, highly mobile industrial equipment [4], [5].

B.Highly Resonants WPT Systems

Resonant: In general, resonance involves the oscillation of energy between two modes, as seen in a mechanical pendulum where energy oscillates between potential and kinetic forms. It's possible for a system to be at resonance while still accumulating a significant store of energy.

DC Power Primary Inductive Secondary Rectifier If the system's rate of energy loss was higher than its rate of

Power Converter Compensation Coupling Compensation energy loss surpasses the rate of energy injection, a buildup

occurs. The behavior of an isolated resonator can be defined by two fundamental factors: the resonant frequency o and he intrinsic loss rate, . The resonator's quality factor, denoted as , which gauges its energy storage efficiency (

= o2), is determined by the ratio of these two factors. [5]. Figure 3 is an example of an electromagnetic resonator circuit with an inductor, capacitor and resistor.

Fig. 2. Basic structure of typical WPT system

A typical Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) system

typically employs input DC voltage derived from a DC L

supply or a battery. The DC input voltage is subsequently C

converted into a high-frequency AC voltage form. In this R

process, the current flowing through the transmitting coil

produces an alternating magnetic field, inducing an AC voltage in the receiving coil. The resonating interaction with the secondary compensation network significantly enhances the transferred power and efficiency. Ultimately, the AC voltage is rectified to provide power for DC loads.

Considering the implementation of Wireless Power Transfer (WPT), power transfer efficiency emerges as a crucial practical consideration. Due to the loose coupling between the transmitter and receiver coils, in contrast to

tightly coupled systems with a transformer core, capturing the transmitted electrical power.

Fig. 3. Basic of resonator.

The energy in this circuit is stored in the magnetic field by the inductor and the electric field by the capacitor, and it oscillates at a resonant frequency between both before dissipating in the resistor. This resonator's resonant frequency and quality factor are expressed as:

Several researchers have tackled this issue and have published techniques to enhance the range of power transfer efficiency. These include impedance matching and notably the incorporation of passive, resonant relay coils to amplify the oscillating magnetic flux at the receiving antenna. In essence, when the transmitter and reception coils resonate at the same frequency, the energy transfer can occur over the greatest possible distance.

Demonstrations of end-to-end efficiencies exceeding

90% have been showcased for high-power applications, such as charging plug-in hybrid vehicles. Each

According to the expression for in Equation 2, the quality factor of the system will increase if the circuit's loss, or , is reduced.

Power source

Temperature sensor

Li-ion Cell

shortened by an additional closed-loop CT-CV charging technique.

Fig. 4 Control loop block diagram for CT-CV scheme [19].

A.Charging Technologies

The system depicted in Figure 6 enables charging a car through a single-phase connection, a three-phase connection, or inductive energy transfer. Cars are categorized into level 1, level 2, and level 3 based on their power ratings, as outlined in Table 1. The technology employed in this system allows for both grid assistance and power recovery, supporting bidirectional energy flow and delivery of reactive power. This multifunctional converter facilitates grid connections across wired and wireless networks.

Wired charging: As per [20], wired charging technologies necessitate a direct connection between the electric vehicle (EV) and the charging system through cables. These technologies are categorized into AC charging technologies and DC charging technologies. AC charging technologies involve charging the battery indirectly in electric vehicles (BEVs) by using the onboard charger (OBC) to feed the battery. In these systems, the conversion unit, responsible for converting AC to DC, is situated inside the vehicle, contributing to an increase in the overall system weight. AC charging technologies are typically employed in single-phase on-board (OB) slow charging systems or three-phase OB fast charging systems. In contrast, DC charging technologies have the capability to directly charge the battery, enabling fast- charging capabilities. Two subgroups of DC charging technologies are off-board fast charging and off-board rapid charging systems.