Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

How to write a research proposal

2006, European Diabetes Nursing

Related Papers

European Diabetes Nursing

Nermin Olgun

Dean Whitehead

Janeth Leksell

Viviane Josewski

sifiso sithole

Nasrin Parsian

Journal of Commonwealth Law and Legal Education

Kingsley O M O T E Mrabure

The establishment of sixteen law clinics in Nigerian universities law faculties (NULF) by the pioneering efforts of Network of University Legal Aid Institutions (NULAI) though commendable is still a far cry from the desired expectation towards establishing more Governmental efforts, private initiatives and alumni endowments in the provision of resources are needed in galvanizing the establishing of law clinics in all NULF. The plausible reason being that clinical legal education (CLE) gears towards the inculcation of practical legal skills, a needed virtue in this 21st century to achieving a virile and an impactful legal education that is relevant to society.

Anna Olinder

RELATED PAPERS

Interacting future visions and decisions in World Heritage management and spatial planning: a case study of the Antonine Wall World Heritage

Roland Láposi

The Free School

Qualitative Health Research

Janice Morse

Xinxing Jiang

Heike Felzmann

Sarah Hope Lincoln

Geraldine MacCarrick

Qualitative Social Work

Alex Barnes

Office of the …

Saoirse Nic Gabhainn

Peter Vaessen

Operations Management for Business Excellence

Godfrey Bridger

IEC. LGBRIMH

Kamal N Kalita

Regenia Boykins

Hester C Klopper

Quality Research in Literacy and Science …

Donna Alvermann , Christine Mallozzi

J. Apelqvist , M. Gershater

Mark alalibo

Mariana Kruger

Margo Paterson

owais kazmi

Agata Gurzawska , David M Douglas , Faridun Sattarov

M. Gershater

Research on Social Work Practice

European Diabetes …

Joshua Sewell

Holly L Northam

Teresa Whitaker , Marjorie Fitzpatrick

Lily Xiao , Julie Henderson

Journal of Advanced Nursing

katie featherstone

MONIKA NIELSEN

PsycEXTRA Dataset

Carmen Samuel-hodge , Derek Griffith

S Vasantha Kumari

NIHR Health Service Delivery Research 2013; 1(7) DOI: 10.3310/hsdr01070

Glenn Robert , Michael D Fischer , Ian Norman

Jasmina Brankovic

British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing)

nikolaos tsourounakis

Getachew Gobena

Jon Bannister

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

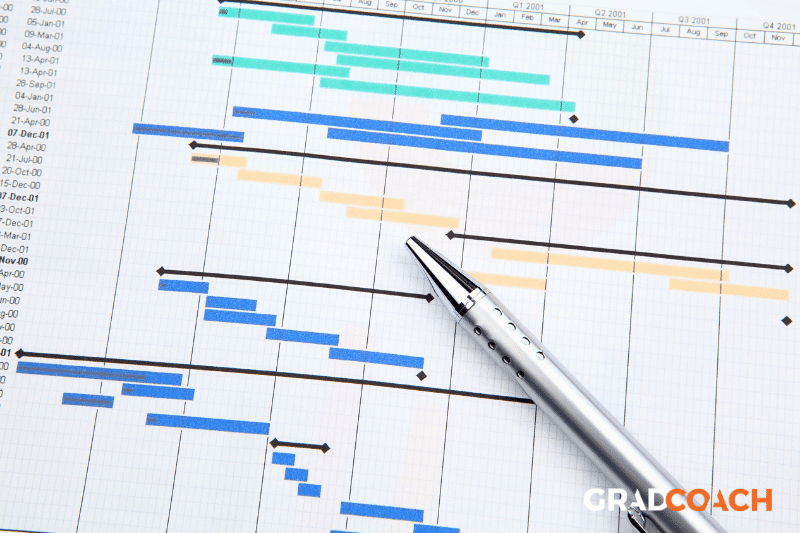

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Thank you very much, this is very insightful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

How to write a research proposal

How to write a research proposal?

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

- PMID: 27729688

- PMCID: PMC5037942

- DOI: 10.4103/0019-5049.190617

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or 'blueprint' for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

Keywords: Guidelines; proposal; qualitative; research.

Publication types

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.

Appendices are documents that support the proposal and application. The appendices will be specific for each proposal but documents that are usually required include informed consent form, supporting documents, questionnaires, measurement tools and patient information of the study in layman's language.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your proposal. Although the words ‘references and bibliography’ are different, they are used interchangeably. It refers to all references cited in the research proposal.

Successful, qualitative research proposals should communicate the researcher's knowledge of the field and method and convey the emergent nature of the qualitative design. The proposal should follow a discernible logic from the introduction to presentation of the appendices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

How to write a research proposal

- M Annersten

A structured written research proposal is a necessary requirement when making an application for research funding or applying to an ethics committee for approval of a research project. A proposal is built up in sections of theoretical background; aim and research questions to be answered; a description and justification of the method chosen to achieve the answer; awareness of the ethical implications of the research; experience and qualifications of the team members to perform the intended study; a budget and a timetable.

This paper describes the common steps taken to prepare a written proposal as attractively as possible to achieve funding.

American Association of Diabetes Educators Education and Research Foundation. Application Form. http://www.aadenet.org [Accessed 1 February 2006].

Polit DF, Hungler BP. Nursing Research. Principles and Methods, 4th edn. Pennsylvania: JB Lippincott Company, 1991.

Lemne C. Handbook for Clinical Investigators. Sweden, Lund: Studentlitteratur, 1999.

Bell J. Doing your Research Project. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1999.

Directive 90/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data. http://www.cdt.org/privacy/eudi-rective/EU_Directivehtml [Accessed 1 February 2006].

Declaration of Helsinki. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm [Accessed 1 February 2006].

International Council of Nurses. Ethical Guidelines for Nursing Research. Geneva: ICN, 2003.

ICH Topic E6: Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/ich/013595en.pdf [Accessed 1 February 2006].

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2006 Copyright © 2006 FEND

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- H Grill-Wikell, M Annersten, A Frid, Pain in connection with capillary blood test at different sites in the palm , International Diabetes Nursing: Vol. 2 No. 2 (2005)

About the Journal

International Diabetes Nursing is the official peer-reviewed journal of the Foundation of European Nurses in Diabetes (FEND). The journal is nurse-led, multidisciplinary in scope, and provides a platform for nurses and other professionals to share knowledge and innovations to improve the care of people with diabetes. Learn more >>

Make a Submission

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Published by the Foundation of European Nurses in Diabetes under the terms of a Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Editor-in-Chief: Prof Davide Ausili Co-Editors: Prof Angus Forbes and Dr Magdalena Annersten Gershater eISSN 2057-3324 (print volumes 2003–2013: ISSN 2057-3316).

Contact | Privacy Policy | Follow @FEND_diabetes

- Faculty of Environment

- School of Food Science and Nutrition

- Research degrees

Writing a research proposal

What is a research proposal .

Getting your research proposal right is a critical part of the PhD application process if you’re not choosing an advertised project and want to conduct your own research idea.

It’s essentially your sales pitch to showcase your proposed research topic, why it’s relevant to the wider world – and why you’re the best person to carry it out. It’s the first time the School will see your project idea, so it’s vital this proposal conveys the importance and originality of your research, based on current knowledge and existing literature surrounding the topic.

As well as the ‘why’, you’ll also detail how you’re going to approach your research, what you hope to achieve and the potential impact your project will have.

What should your proposal include?

Below is an outline of the elements a research proposal might typically include:

Title page – A clear and succinct description of your research

Introduction (250-350 words) – A brief explanation of what you propose to research, why the research is of value, where its originality lies and how it contributes to the literature. You can also demonstrate any aims and objectives of your research in this section.

Literature review (1,200-1,400 words) – A thorough examination of key, recent contributions in research periodicals relating to the area of research in question. You should use the literature review to identify gaps in – or problems with – existing research to justify why further or new research is required. You should include a clear statement of your research questions.

Research Method (1,200-1,400 words) – A description of your choice of methodology, including details of methods of data collection and analysis.

Conclusion (200-250 words) – A summary of your project which collates the key points clearly. Remember, this is your final chance to convey why the School should choose your project – so make it compelling.

Bibliography/ References – Any literature cited in the proposal should be listed at the end of the document. Broadly speaking, Harvard referencing is the preferred style.

Top tips to making your proposal great

Keep it succinct and clear – try not to overcomplicate or go into excessive detail at this stage. The proposal is the starting point so make sure you’re getting across the key points in a structured, concise and clear way.

Demonstrate your expertise – this proposal is your chance to really showcase your knowledge and skills in the area you’re hoping to research so don’t hold back. Use this opportunity to demonstrate exactly why you’re the best person to conduct this project.

Proof your work – ensuring your proposal is free of spelling or grammar errors is so important. You want to explain your project in the best way possible, without mistakes distracting the flow and, therefore, the impact of what you’re saying. Plus, it shows you have a critical eye which is one of the key skills you’ll need for your PhD.

Make it compelling – Yes, your proposal is a factual document, but it also needs to stand out. Letting your passion, originality and drive for your chosen topic shine through will help give your proposal the edge in this highly competitive process.

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Components of a research proposal.

In general, the proposal components include:

Introduction: Provides reader with a broad overview of problem in context.

Statement of problem: Answers the question, “What research problem are you going to investigate?”

Literature review: Shows how your approach builds on existing research; helps you identify methodological and design issues in studies similar to your own; introduces you to measurement tools others have used effectively; helps you interpret findings; and ties results of your work to those who’ve preceded you.

Research design and methods: Describes how you’ll go about answering your research questions and confirming your hypothesis(es). Lists the hypothesis(es) to be tested, or states research question you’ll ask to seek a solution to your research problem. Include as much detail as possible: measurement instruments and procedures, subjects and sample size.

The research design is what you’ll also need to submit for approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) if your research involves human or animal subjects, respectively.

Timeline: Breaks your project into small, easily doable steps via backwards calendar.

Preparing your research proposal

Embarking on a research project can be both exciting and daunting. Whether applying for graduate school , seeking funding, or preparing for your thesis , a well-prepared research proposal is your first step toward academic success. This guide will provide you with the fundamental concepts and tools to construct a coherent and persuasive research proposal. You’ll understand the structure and learn how to articulate a clear vision for your study, ensuring your ideas are presented logically and effectively.

We invite you to explore the enriching journey of research proposal preparation. By diving into this article, you will gain valuable insights into creating a document that meets academic standards and intrigues your audience, laying a solid groundwork for your research ambitions.

Overview of a research proposal

A research proposal is a detailed blueprint that outlines your research project, clarifying the investigation’s objectives, significance, and methodological approach. While formats can vary across academic or professional fields, most research proposals share common components that structure your research narrative effectively:

- Title page . Acts as the proposal’s cover, detailing essential aspects such as the project title, your name, your supervisor’s name, and your institution.

- Introduction . Set the stage by introducing the research topic , background, and the core problem your study addresses.

- Literature review . Evaluates relevant existing research to position your project within the broader academic conversation.

- Research design . Details the methodological process , including how data will be collected and analyzed.

- Reference list . Ensures all sources and citations supporting your proposal are clearly documented.

These elements form the structure of your research proposal, each contributing uniquely to the These elements create the framework of your research proposal, each playing a unique role in building a convincing and well-organized argument. In the sections that follow, we’ll explore each component in detail, explaining their purposes and showing you how to implement them effectively.

Objectives of a research proposal

Developing a research proposal is essential for securing funding and advancing in graduate studies. This document outlines your research agenda and demonstrates its significance and practicality to crucial stakeholders such as funding bodies and academic committees. Here’s how each component of the research proposal serves a strategic purpose:

- Relevance . Highlight the originality and significance of your research question. Articulate how your study introduces new perspectives or solutions, enriching the existing body of knowledge in your field. This ties directly to the compelling introduction you prepared, setting the stage for a strong justification of your project’s worth.

- Context . Show a deep understanding of the subject area. Being familiar with the main theories, important research, and current debates helps anchor your study in the scholarly landscape and boosts your credibility as a researcher. This builds on the basic knowledge from the literature review, connecting past studies to your proposed research.

- Methodological approach . Detail the techniques and tools you will employ to collect and analyze data. Explain your chosen methodologies as the most appropriate for addressing your research questions, supporting the design choices explained in the research design section of the research proposal.

- Feasibility . Consider the practical aspects of your research, such as time, resources, and logistics, within the limits of your academic program or funding guidelines. This evaluation ensures that your project is realistic and achievable, which is crucial for funders and institutions.

- Impact and significance . Outline the broader implications of your research. Discuss how the expected outcomes can influence the academic field, contribute to policy-making, or address societal challenges.

Selecting the right proposal length

The appropriate length of a research proposal varies based on its purpose and audience. Proposals for academic coursework might be straightforward, whereas those intended for Ph.D. research or significant funding applications are typically more detailed. Consult with your academic advisor or follow the guidelines from your institution or funding agency to measure the necessary scope. Think of your research proposal as a shorter version of your future thesis or dissertation —without the results and discussion sections. This approach helps you structure it well and cover everything important without adding unnecessary details.

Having outlined the key objectives and structure of a research proposal, let’s delve into the first essential component: the title page. This in your research proposal serves as the cover and first impression of your project. It includes essential information such as:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

Including this information not only identifies the document but also provides context for the reader. If your proposal is extensive, consider adding an abstract and a table of contents to help navigate your work. The abstract offers a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting key points and objectives, while the table of contents provides an organized list of sections, making it easier for readers to find specific information.

By presenting a clear and informative title page, you set a professional tone and ensure that all necessary details are readily available to those reviewing your research proposal.

Introduction

With the title page complete, we move on to the introduction, the initial pitch for your project. This section sets the stage for your entire research proposal, clearly and concisely outlining what you plan to investigate and why it is important. Here’s what to include:

- Introduce your topic. Clearly state the subject of your research. Provide a brief overview that captures the essence of what you are investigating.

- Provide necessary background and context. Offer a concise summary of the existing research related to your topic. This helps situate your study within the broader academic landscape and shows that you are building on a solid foundation of existing knowledge.

- Outline your problem statement and research questions. Clearly describe the specific problem or issue your research will address. Present your main research questions that will guide your study.

To effectively guide your introduction, consider including the following information:

- Interest in the topic. Identify who might be interested in your research, such as scientists, policymakers, or industry professionals. This shows the broader relevance and potential impact of your work.

- Current state of knowledge. Summarize what is already known about your topic. Highlight key studies and findings that are relevant to your research.

- Gaps in current knowledge. Point out what is missing or not well understood in the existing research. This helps explain the need for your study and shows that your research will contribute new insights.

- New contributions. Explain what new information or perspectives your research will provide. This could include new data, a novel theoretical approach, or innovative methods.

- Significance of your research. Communicate why your research is worth pursuing. Discuss the potential implications and benefits of your findings, both for advancing knowledge in your field and for practical applications.

A well-prepared introduction outlines your research agenda and engages your readers, encouraging them to see the value and importance of your proposed study.

Literature review

Having introduced your research topic and its significance, the next step is to set the academic foundation for your study through a comprehensive literature review. This section demonstrates your familiarity with key research, theories, and debates relevant to your topic, placing your project within the broader academic context. Below are guidelines on how to effectively compose your literature review.

Purpose of the literature review

The literature review serves multiple purposes:

- Foundation building. It provides a solid grounding in existing knowledge and highlights the context for your research.

- Identifying gaps. It helps identify gaps or inconsistencies in the current body of research that your study aims to address.

- Justifying your study. It justifies the need for your research by showing that your work will contribute new insights or methods.

Key elements to include

To construct a thorough literature review, incorporate these essential elements:

- Survey of key theories and research. Begin by summarizing the major theories and key pieces of research related to your topic. Highlight influential studies and seminal works that have shaped the field.

- Comparative analysis. Compare and contrast different theoretical perspectives and methodologies. Discuss how these approaches have been applied in previous studies and what their findings suggest.

- Evaluation of strengths and weaknesses. Critically evaluate the strengths and limitations of existing research. Point out methodological flaws, gaps in data, or theoretical inconsistencies that your study will address.

- Positioning your research. Explain how your research builds on, challenges, or synthesizes previous work. Clearly articulate how your study will advance understanding in your field.

Strategies for writing your literature review

Organize and present your literature review effectively using these strategies:

- Organize thematically. Structure your review around themes or topics rather than chronologically. This approach allows you to group similar studies together and provide a more coherent analysis.

- Use a conceptual framework. Develop a conceptual framework to organize your literature review. This framework helps link your research questions to the existing literature and provides a clear rationale for your study.

- Highlight your contribution. Make sure to highlight what new perspectives or solutions your research will bring to the field. This could involve introducing novel methodologies, theoretical frameworks, or addressing previously unexplored areas.

Practical tips

Improve the clarity and impact of your literature review with these practical tips:

- Be selective. Focus on the most relevant and impactful studies. Avoid including every piece of research you encounter, and instead, highlight those that are most relevant to your topic.

- Be critical. Don’t just summarize existing research; critically engage with it. Discuss the implications of previous findings and how they inform your research questions.

- Be clear and concise. Write clearly and concisely, ensuring that your review is easy to follow and understand. Avoid jargon and overly complex language.

Conclusion of the literature review

Summarize the key points from your literature review, restating the gaps in knowledge that your study will address. This sets the stage for your research design and methodology, demonstrating that your study is both necessary and well-founded in the existing academic discourse.

Methodology and research design

After selecting the academic foundation in your literature review, the next step is to focus on the methodology and research strategy. This section is crucial as it outlines how you will conduct your research and provides a clear roadmap for your study. It ensures that your project is feasible, methodologically sound, and capable of addressing your research questions effectively. Here’s how to structure this important section:

- Restate your objectives . Begin by restating the main objectives of your research. This reaffirms the focus of your study and transitions smoothly from the literature review to your research design.

- Outline your research strategy. Provide a detailed description of your overall research approach. Specify whether your research will be qualitative, quantitative, or a mix of both. Clarify whether you conducting original data collection or analyzing primary and secondary sources. Describe whether your study will be descriptive, correlational, or experimental in nature.

- Describe your population and sample . Clearly define who or what you will study. Identify your study subjects (e.g., undergraduate students at a large university or historical documents from the early 20th century). Explain how you will select your subjects, whether through probability sampling, non-probability sampling, or another method. Specify when and where you will collect your data.

- Detail your research methods . Explain the tools and procedures you will use to collect and analyze your data. Describe the instruments and techniques (such as surveys, interviews, observational studies, or experiments). Explain why you have chosen these particular methods as the most effective for answering your research questions.

- Address practical considerations . Consider and outline the practical aspects of your research to ensure it is achievable. Estimate the time required for each stage of your study. Discuss how you will get access to your population or data sources and consider any permissions or ethical clearances needed. Identify any potential obstacles you might face and propose strategies to address them.

- Ensuring methodological precision . Ensure your approach is well-planned and capable of producing reliable and valid results. Highlight how your chosen methods align with your research objectives and address the gaps identified in the literature review.

Providing a comprehensive methodology and research strategy section assures reviewers of your project’s feasibility and shows your readiness to undertake the study.

Research impact and significance

The expected impact of this research proposal extends beyond academic circles into policy formulation and societal benefit, reflecting its broad relevance and significance. By addressing [specific topic], the study aims to contribute significantly to the existing body of knowledge while providing practical solutions that can be implemented in real-world settings.

Field influence

The findings of the research proposal are expected to challenge and potentially reshape current theories and practices within the field of [relevant field]. By exploring innovative methodologies or uncovering new data, the study could pave the way for more effective strategies in [specific application], influencing academic research and practical applications.

Policy impact

The project is ready to inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations that policymakers can directly use. For example, insights derived from the study could influence [specific policy area], leading to improved [policy outcome], which could significantly enhance [specific aspect of public life].

Societal contributions

The societal implications of the research proposal are profound. It aims to address [key societal challenge], thereby improving quality of life and promoting long-lasting practices. The potential for widespread adoption of the study’s outcomes could lead to significant improvements in [area of societal impact], such as increasing access to [critical resources] or improving public health standards.

Overall, the significance of the research proposal lies in its dual ability to advance academic understanding and produce real, beneficial changes in policy and society. By funding the project, [funding body] will be supporting a groundbreaking study with the potential to deliver significant results that match broader goals of social progress and innovation.

Reference list

After highlighting the potential impacts of the research, it is crucial to acknowledge the foundation underpinning these insights: the sources. This section of the research proposal is vital for substantiating the arguments presented and upholding academic integrity. Here, every source and citation used throughout your proposal should be carefully documented. This documentation provides a roadmap for validation and further exploration, ensuring that every claim or statement can be traced back to its source.

Such thorough documentation improves the proposal’s credibility, allowing readers and reviewers to verify the sources of your ideas and findings easily. By diligently keeping a detailed reference list, you uphold academic standards and strengthen the scholarly basis of your research proposal. This practice supports transparency and encourages deeper engagement and follow-up by interested students and practitioners.

Detailed timeline for research project execution

After detailing the components of the research proposal structure, it’s crucial to set a clear timeline for the research project. This example schedule guides you through the necessary steps to meet typical academic and funding cycle deadlines:

- Objective . Conduct initial meetings with your advisor, extensively review relevant literature, and refine your research questions based on the insights earned.

- Example deadline . January 14th

- Objective . Develop and finalize the data collection methods, such as surveys and interview protocols, and set the analytical approaches for the data.

- Example deadline. February 2nd

- Objective . Start finding participants, distribute surveys, and conduct initial interviews. Make sure all data collection tools are working properly.

- Example deadline . March 10th

- Objective . Process the collected data, including the transcription and coding of interviews. Begin statistical and thematic analysis of the datasets.

- Example deadline . April 10th

- Objective . Collect the initial draft of the results and discussion sections. Review this draft with your advisor and integrate their feedback.

- Example deadline . May 30th

- Objective . Revise the draft based on feedback, complete the final proofreading, and prepare the document for submission, including printing and binding.

- Example deadline . July 10th

These example deadlines serve as a framework to help you organize and manage your time effectively throughout the academic year. This structure ensures that each step of the research proposal is completed methodically and on time, promoting transparency and assisting in meeting educational and financing deadlines.

Budget overview

Following our detailed project timeline, it’s key to note that a budget overview is a standard and crucial part of academic research proposals. This section gives funders a clear view of anticipated costs, showing how money will be carefully used throughout the project. Including a budget makes sure all possible expenses are considered, proving to funders that the project is well-organized and financially sound:

- Personnel costs . Specify the salaries or stipends for research assistants and other team members, including their roles and the employment duration. Clarify the importance of each team member to the project’s success, ensuring their roles are directly linked to specific project outcomes.

- Travel expenses . Detail costs associated with fieldwork or archival visits, including transportation, accommodation, and daily allowances. Explain the necessity of each trip about your research objectives, highlighting how these activities contribute to data collection and overall project success.

- Equipment and materials . List all essential equipment, software, or supplies necessary for the project. Describe how these tools are critical for effective data collection and analysis, supporting the methodological integrity of the research.

- Miscellaneous costs . Account for additional expenses such as publication fees, conference participation, and unforeseen expenses. Include a contingency fund to cover unexpected costs, providing a cause for the estimated amount based on potential project risks.

Each budget item is calculated using data from suppliers, standard service rates, or average salaries for research roles, improving the budget’s credibility and transparency. This level of detail fulfills the funder’s requirements and showcases the thorough planning that backs the research proposal.

By explaining each expense clearly, this budget overview allows funding bodies to see how their investment will directly support the successful performance of your research, aligning financial resources with projected outcomes and milestones.

Potential challenges and mitigation strategies

As we near the conclusion of this research proposal, it’s crucial to predict and plan for potential challenges that could impact the study’s success. Identifying these challenges early and proposing concrete strategies to overcome them, you underscore your commitment to a successful and achievable project.

Identification of potential challenges

In planning the research proposal, you need to consider several potential drawbacks:

- Access to participants. Engaging the target demographic can be challenging due to privacy concerns or lack of interest, which might restrict data collection.

- Data reliability . Keeping the reliability and validity of data is crucial, especially when dealing with subjective responses or observations. Inconsistencies here could compromise the study’s outcomes.

- Technological limitations . Encountering technical issues with data collection tools or analysis software can lead to delays and disrupt the research process, affecting the timeline and quality of findings.

Handling strategies

To effectively address these challenges, the following strategies need to be integrated into the research proposal:

- Building relationships and gaining trust . Early engagement with community leaders or relevant institutions will simplify access to participants. This includes securing the necessary permissions and ethical clearances well in advance of data collection.

- Careful research design . Set up a strong plan for collecting data, including trial runs to improve methods and tools, ensuring the data you collect is reliable.

- Technological preparedness . Create backup systems, and ensure all team members are trained to efficiently handle the necessary technology. Launch partnerships with technical support teams to ensure any issues that arise are quickly resolved.

Actively addressing these challenges, the research proposal shows funders and academic committees that the project is strong and can handle difficulties well. This approach makes the proposal more trustworthy and shows careful planning and foresight.

Ethical considerations in research proposals

As briefly mentioned in the previous section, ethical considerations are critical in your research proposal. It’s crucial to delve deeper into these principles to ensure the protection and respect of all participants, encouraging trust and credibility in your study. Key ethical practices include:

- Informed agreement . Get informed permission from each participant before the study begins. Provide detailed information about the nature of the research, their role in it, potential risks, and benefits. This information is provided verbally and in writing, with consent documented through signed forms.