Can document characteristics affect motivations for literature usage?

- Published: 27 May 2024

Cite this article

- ↓Xia Peng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8560-7818 1 , 2 ,

- Zequan Xiong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4349-371X 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Li Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6694-8281 1

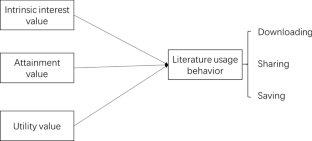

Beyond citations, the impact of scientific publications is often measured by usage metrics, such as downloads, save counts and sharing counts. However, the motivations behind the utilization of these publications and their influencing factors have not yet been well studied. Therefore, it remains questionable whether and to what extent usage metrics can reflect the impact of publications. Based on expectancy-value theory, the aim of the present study was to examine the differences in behavioral characteristics and driving factors between article downloading, sharing, and saving, especially document characteristics. For the present study, survey data from 480 respondents across Chinese universities were collected and investigated in terms of the frequency and purpose of three literature usage behaviors, namely, downloading, sharing, and saving. Additionally, 11 document characteristics were used to construct three variables in the research models: intrinsic interest value, attainment value, and utility value. Their effects on three usage behaviors were examined based on path analysis via SmartPLS. The results showed that the overall frequency of article downloading and saving was greater than that of article sharing. The primary purposes of downloading and saving were closely related to scientific research, such as for review and citing. The sharing of articles on social media was mainly for agreeing with their opinions. Both intrinsic interest value and utility value exhibited a significant positive influence on article-downloading, whereas attainment value and intrinsic interest value showed a significant relationship with sharing and saving, respectively. In conclusion, different literature usage behaviors can be triggered and driven by the distinct values of research articles. The results obtained in this study could help to clarify the determinants of different usage behaviors; additionally, they might promote the reasonable application of usage metrics or altmetrics in scientific evaluation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Akbar, A., Malik, A., & Warraich, N. F. (2023). Big five personality traits and knowledge sharing intentions of academic librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 49 (2), 102632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102632

Article Google Scholar

Case, D. O., & Higgins, G. M. (2000). How can we investigate citation behavior? A study of reasons for citing literature in communication. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 51 (7), 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(2000)51:7%3c635::AID-ASI6%3e3.0.CO;2-H

Ceyhan, G. D., & Tillotson, J. W. (2020). Early year undergraduate researchers’ reflections on the values and perceived costs of their research experience. International Journal of Stem Education, 7 (1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00248-x

Chen, B. (2018). Usage pattern comparison of the same scholarly articles between Web of Science (WoS) and Springer. Scientometrics, 115 (1), 519–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2616-3

Chen, B., Deng, D., Zhong, Z., & Zhang, C. (2020). Exploring linguistic characteristics of highly browsed and downloaded academic articles. Scientometrics, 122 (3), 1769–1790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03361-4

Chi, P., & Glänzel, W. (2018). Comparison of citation and usage indicators in research assessment in scientific disciplines and journals. Scientometrics, 116 (1), 537–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2708-8

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295 (2), 295–336.

Google Scholar

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

de Winter, J. C. F. (2015). The relationship between tweets, citations, and article views for PLoS ONE articles. Scientometrics, 102 (2), 1773–1779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1445-x

Duy, J., & Vaughan, L. (2006). Can electronic journal usage data replace citation data as a measure of journal use? An empirical examination1. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32 (5), 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2006.05.005

Eccles, J. S. (2009). Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educational Psychologist, 44 (2), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832368

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 , 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Eldakar, M. A. M. (2019). Who reads international Egyptian academic articles? An altmetrics analysis of Mendeley readership categories. Scientometrics, 121 (1), 105–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03189-7

Fiala, D., Král, P., & Dostal, M. (2021). Are papers asking questions cited more frequently in computer science? Computers, 10 (8), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers10080096

Fong, S. W. L., Ismail, H. B., & Kian, T. P. (2023). Reflective-formative hierarchical component model for characteristic-adoption model. SAGE Open, 13 (2), 1935513981. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231180669

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Galbraith, Q., Butterfield, A. C., & Cardon, C. (2023). Judging journals: How impact factor and other metrics differ across disciplines. College & Research Libraries, 84 (6), 888–906. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.84.6.888

Glänzel, W., & Gorraiz, J. (2015). Usage metrics versus altmetrics: Confusing terminology? Scientometrics, 102 (3), 2161–2164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1472-7

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (5), 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19 (2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Haustein, S., Costas, R., & Larivière, V. (2015). Characterizing social media metrics of scholarly papers: The effect of document properties and collaboration patterns. PLoS ONE, 10 (3), 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120495

Haustein, S., Peters, I., Sugimoto, C. R., Thelwall, M., & Larivière, V. (2014). Tweeting biomedicine: An analysis of tweets and citations in the biomedical literature. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65 (4), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23101

Heard, S. B., Cull, C. A., & White, E. R. (2023). If this title is funny, will you cite me? Citation impacts of humour and other features of article titles in ecology and evolution. Facets, 8 , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2022-0079

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116 (1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Hu, H., Wang, D., & Deng, S. (2021). Analysis of the scientific literature’s abstract writing style and citations. Online Information Review, 45 (7), 1290–1305. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-05-2020-0188

Jamali, H. R., & Nikzad, M. (2011). Article title type and its relation with the number of downloads and citations. Scientometrics, 88 (2), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0412-z

Khan, M. S., & Younas, M. (2017). Analyzing readers behavior in downloading articles from IEEE digital library: A study of two selected journals in the field of education. Scientometrics, 110 (3), 1523–1537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2232-7

Kim, Y. (2018). An empirical study of biological scientists’ article sharing through ResearchGate: Examining attitudinal, normative, and control beliefs. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70 (5), 458–480. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2018-0126

Kim, Y., & Sir, Oh. (2020). Researchers’ article sharing through institutional repositories and ResearchGate: A comparison study. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 53 (3), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620962840

Kyari, B. A., Othman, I., & Faisal, S. H. M. (2021). Behavioral intention model for green information technology adoption in Nigerian manufacturing industries. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74 (1), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2021-0128

Lee, J., Oh, S., Dong, H., Wang, F., & Burnett, G. (2019). Motivations for self-archiving on an academic social networking site: A study on researchgate. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70 (6), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24138

Lemke, S., Brede, M., Rotgeri, S., & Peters, I. (2022). Research articles promoted in embargo e-mails receive higher citations and altmetrics. Scientometrics, 127 (1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04217-1

Mehdi, H., Mohammad, T., Sajjad, S., & Sina, S. (2022). Who one is, whom one knows? Evaluating the importance of personal and social characteristics of influential people in social networks. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 75 (6), 1008–1032. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-12-2021-0382

Mohammadi, E., & Thelwall, M. (2014). Mendeley readership altmetrics for the social sciences and humanities: Research evaluation and knowledge flows. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65 (8), 1627–1638. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23071

Mohammadi, E., Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2016). Can Mendeley bookmarks reflect readership? A survey of user motivations. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67 (5), 1198–1209. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23477

Na, J. (2015). User motivations for tweeting research articles: A content analysis approach. In R. Allen, J. Hunter, & M. Zeng (Eds.), Digital libraries: Providing quality information. ICADL (pp. 197–208). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-27974-9_20

Chapter Google Scholar

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Pearson, W. S. (2021). Quoted speech in linguistics research article titles: Patterns of use and effects on citations. Scientometrics, 126 (4), 3421–3442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03827-5

Reijo, S. (2012). Expectancy-value beliefs and information needs as motivators for task-based information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 68 (4), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211239075

Sagi, I., & Yechiam, E. (2008). Amusing titles in scientific journals and article citation. Journal of Information Science, 34 (5), 680–687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551507086261

Said, A., Bowman, T. D., Abbasi, R. A., Aljohani, N. R., Hassan, S., & Nawaz, R. (2019). Mining network-level properties of Twitter altmetrics data. Scientometrics, 120 (1), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03112-0

Sáinz, M., Fàbregues, S., Rodó-de-Zárate, M., Martínez-Cantos, J., Arroyo, L., & Romano, M. (2018). Gendered motivations to pursue male-dominated STEM careers among Spanish young people: A qualitative study. Journal of Career Development, 47 (4), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845318801101

Savolainen, R. (2013). Approaching the motivators for information seeking: The viewpoint of attribution theories. Library & Information Science Research, 35 (1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.07.004

Shema, H., Bar-Ilan, J., & Thelwall, M. (2015). How is research blogged? A content analysis approach. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66 (6), 1136–1149. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23239

Sigaard, K. T., & Skov, M. (2015). Applying an expectancy-value model to study motivators for work-task based information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 71 (4), 709–732. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2014-0047

Subotic, S., & Mukherjee, B. (2013). Short and amusing: The relationship between title characteristics, downloads, and citations in psychology articles. Journal of Information Science, 40 (1), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551513511393

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2013). Scholars and faculty members’ lived experiences in online social networks. The Internet and Higher Education, 16 , 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.01.004

Wang, X., Fang, Z., & Sun, X. (2016). Usage patterns of scholarly articles on Web of Science: A study on Web of Science usage count. Scientometrics, 109 (2), 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2093-0

Wang, X., Peng, L., Zhang, C., Xu, S., Wang, Z., Wang, C., & Wang, X. (2013). Exploring scientists’ working timetable: A global survey. Journal of Informetrics, 7 (3), 665–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.04.003

Xiong, Z., Peng, X., Yang, L., Lou, W., & Zhao, S. X. (2023). Motivation for downloading academic publications. Library & Information Science Research, 45 (2), 101239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2023.101239

Yang, S., Zheng, M., Yu, Y., & Wolfram, D. (2021). Are Altmetric.com scores effective for research impact evaluation in the social sciences and humanities? Journal of Informetrics, 15 (1), 101120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2020.101120

Yu, H., Wang, Y., Hussain, S., & Song, H. (2023). Towards a better understanding of Facebook Altmetrics in LIS field: Assessing the characteristics of involved paper, user and post. Scientometrics, 128 (5), 3147–3170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04678-6

Zahedi, Z., & Haustein, S. (2018). On the relationships between bibliographic characteristics of scientific documents and citation and Mendeley readership counts: A large-scale analysis of Web of Science publications. Journal of Informetrics, 12 (1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.12.005

Zahra, S., Karim, S. M., & Reza, A. M. (2022). Application of theory of planned behavior in identifying factors affecting online health information seeking intention and behavior of women. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 74 (4), 727–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-07-2021-0209

Zhang, L., & Wang, J. (2021). What affects publications’ popularity on Twitter? Scientometrics, 126 (11), 9185–9198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04152-1

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the help and contribution of all anonymous respondents. This research is funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 23BTQ084).

Funding was provided by National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 23BTQ084).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Library, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

↓Xia Peng, Zequan Xiong & Li Yang

Interdisciplinary Frontier Research Promotion Center, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

↓Xia Peng & Zequan Xiong

School of Economics and Management, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

Zequan Xiong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zequan Xiong .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 23 KB)

Appendix A. Questionnaire on three types of literature usage behavior

Supplementary file2 (DOCX 16 KB)

Appendix B. Abbreviations of document characteristics and corresponding descriptions.

Supplementary file3 (DOCX 31 KB)

Appendix C. Supplementary data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Peng, ↓., Xiong, Z. & Yang, L. Can document characteristics affect motivations for literature usage?. Scientometrics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05044-w

Download citation

Received : 10 January 2024

Accepted : 26 April 2024

Published : 27 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-05044-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Downloading

- Literature usage behaviors

- Document characteristics

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Social media use and depression in adolescents: a scoping review

There have been increases in adolescent depression and suicidal behaviour over the last two decades that coincide with the advent of social media (SM) (platforms that allow communication via digital media), which is widely used among adolescents. This scoping review examined the bi-directional association between the use of SM, specifically social networking sites (SNS), and depression and suicidality among adolescents. The studies reviewed yielded four main themes in SM use through thematic analysis: quantity of SM use, quality of SM use, social aspects associated with SM use, and disclosure of mental health symptoms. Research in this field would benefit from use of longitudinal designs, objective and timely measures of SM use, research on the mechanisms of the association between SM use and depression and suicidality, and research in clinical populations to inform clinical practice.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, adolescent depression and suicidal behaviours have increased considerably. In the USA, depression diagnoses among youth increased from 8.7% in 2005 to 11.3% in 2014 ( Mojtabai, Olfson, & Han, 2016 ). Additionally, suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth between the ages of 10 and 34 ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2017 ), with a 47.5% increase since 2000 ( Miron, Yu, Wilf-Miron, & Kohane, 2019 ). One suggested cause for this rise in adolescent depression and suicide is the advent of social media (SM) ( McCrae, Gettings, & Purssell, 2017 ; Twenge, Joiner, Rogers, & Martin, 2018 ).

The term ‘social media’ describes types of media that involve digital platforms and interactive participation. SM includes forms such as email, text, blogs, message boards, connection sites (online dating), games and entertainment, apps, and social networking sites (SNS) ( Manning, 2014 ). Over the past decade, SNS platforms designed to help people communicate and share information online have become ubiquitous. Among youth, 97% of all adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 use at least one of the following seven SNS platforms: YouTube (85% of adolescents), Instagram (72%), Snapchat (69%), Facebook (51%), Twitter (32%), Tumblr (9%) or Reddit (7%) ( Pew Research Center, 2018a ).

Concerns have arisen around the effects of SM on adolescents’ mental health, due to SM’s association with decreased face-to-face interpersonal interactions ( Baym, 2010 ; Kraut et al., 1998 ; Nie, Hillygus, & Erbring, 2002 ; Robinson, Kestnbaum, Neustadtl, & Alvarez, 2002 ), addiction-like behaviours ( Anderson, Steen, & Stavropoulos, 2017 ), online bullying ( Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2012 ), social pressure through increased social comparisons ( Guernsey, 2014 ), and contagion effect through increased exposure to suicide stories on SM ( Bell, 2014 ).

Conversely, others have described potential benefits of SM use in adolescents such as feelings of greater connection to friends and interactions with more diverse groups of people who can provide support ( Pew Research Center, 2018b ). In fact, higher internet use has been associated with positive social well-being, higher use of communication tools, and increased face-to-face conversations and social contacts in college students ( Baym, Zhang, & Lin, 2004 ; Kraut et al., 2002 ; Wang & Wellman, 2010 ). These findings suggest that internet use, including SM, may provide opportunities for social connection and access to information ( Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016 ).

Recent systematic reviews examining the association between online technologies and depression have found a ‘general correlation’ between SM use and depression in adolescents, but with conflicting findings in some domains (e.g. the association between time spent on SM and mental health problems), overall limited quality of the evidence ( Keles, McCrae, & Grealish, 2019 ), and a relative absence of studies designed to show causal effects ( Best, Manktelow, & Taylor, 2014 ). The scope of search in these reviews is broader in topic, including online technologies other than SM ( Best et al., 2014 ) or focussed on a select number of studies in order to meet the requirements of a systematic review ( Keles et al., 2019 ). With this scoping review, we aim to expand the inclusion of studies with a range of designs, while narrowing the scope of the topic of SM to those studies that specifically included SNS use. Additionally, we aim to expand the understanding and potential research gaps on the bi-directional association between SM and depression and suicidal behaviours in adolescents, including studies that consider SM use as a predictor as well as an outcome. A better understanding of this relationship can inform interventions and screenings related to SM use in clinical settings.

This scoping review was initiated by a research team including 3 mental health professionals with clinical expertise in treating depression and suicidality in adolescents. We followed the framework suggested by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for scoping reviews. The review included five steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

Research question

The review was guided by the question: What is known from the existing literature about the association between depression and suicidality and use of SNS among adolescents? Given that much of the literature used SM and SNS interchangeably, this review used the term ‘social media’ or ‘SM’ when it was difficult to discern if the authors were referring exclusively to SNS.

Data sources and search strategy

The team conceived the research question through a series of discussions, and the first author (CV) consulted an informationist to identify the appropriate search terms and databases. A search of the database PsychINFO limited to peer-reviewed articles was conducted on 5 June 2019 (see Table 1 for search strategy). No additional methods were identified through other sources. The search was broad to include articles measuring depression as an outcome variable, and as a co-variate or independent variable. There was no restriction on the type of study design included, and English and Spanish language articles were included in the search. Articles were organized using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia).

Search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

(1) The study examined SM (versus internet use in general) and made specific mention of SNS; (2) participants were between the ages of 10 and 18. If adults were included, the majority of the study population was between 10–18 years of age, or the mean participant age was 18 or younger; (3) the study examined the association between SM use and depression and/or suicidality; (4) the study included at least one measure of depression; and (5) if the focus of the study was on SM addiction or cyberbullying, it included mention and a measure of depressive symptoms. We did not include articles in which: (1) the study primarily focussed on media use other than SM, or that did not specifically mention inclusion of SNS (e.g. studies that focussed only on TV, video game, smartphone use, blogging, email); (2) included primarily adult population; (3) was not an original study, but a case report, review, commentary, erratum, or letter to the editor; (4) focussed on addiction and cyberbullying exclusively without a depression measure; and (5) the method used was content analysis of SM posts without specification of the population age range.

Title and abstract relevance screening

The search yielded 728 articles of which six duplicates were removed. One author (CV) screened the remainder of the articles by title and abstract and a second author (TL) reviewed every 25th article for agreement. All authors screened full-text articles and extracted data from those that met the inclusion criteria. The authors met over the course of the full-text review process to resolve conflicts and maintain consistency among the authors themselves and with the research question. Of the total number of studies included for full-text review, 505 articles were excluded. Out of the 223 full-text studies assessed for eligibility, 175 were excluded. A total of 42 articles were eligible for review (see Figure 1 : PRISMA flow chart for details). A form was developed to extract the characteristics of each study that included author and year of publication, objectives of the study, study method, country where the study was conducted, depression scale used, number of participants, participant age, and results (see Table 2 for details).

PRISMA flow chart of data selection process.

Data charting form including author and year of publication, objectives of the study, method used, country where the study was conducted, depression scale used, number of participants, participant age, results and main social media focus.

AIU = Addictive internet Use; BIU = Borderline Addictive Internet Use; BSMAS = Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale; BIU = Borderline addictive internet use; CBP = Cyberbullying Perpetration; CERM = Cuestionario de Experiencias Relacionadas con el móvil (Questionnaire of Experiences Related to the cellphone); DIB = Dysfunctional Internet Behaviour; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, Text Revision); FOMO = Fear of Missing Out; HVSM = Highly Visual Social Media; SNI = Intensity of social network use; IA = Internet Addiction; IAB = Internet Addictive Behaviour; OSNA = Online social networking addiction; PSMU = Problematic Social Media Use; RADS-2 = Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale - Version 2; SITBs = self-injurious thoughts and behaviours; SNS = social networking sites.

Data summary and synthesis

After reviewing the table, each study was labelled according to the main focus of research related to SM, based on the objectives, variables used, and results of the study. The topics were classified into nine different categories based on the main SM focus of the article; categories were discussed and reviewed by two authors (TL and CV) ( Table 2 ). All authors then discussed the categories and grouped them into four main themes of studies looking at SM and depression in adolescents.

A total of 42 studies published between 2011 and 2019 met the inclusion criteria. Of the studies included, 16 were conducted in European Countries, 14 in the USA, 5 in Asia, 3 in Canada, 2 in Australia, and 2 in Latin American Countries. The number of participants per study ranged from 23 in a qualitative study (94 in the smallest quantitative study) to 118,545 participants in the largest study ( Table 2 ).

The studies reviewed were grouped into four themes with nine categories according to the main focus of the research. The themes and categories were: (1) quantity of SNS use: effects of the frequency of SM use and problematic SM use (or evidence of addictive engagement with SM); (2) quality of SM use: characteristics of SNS use and social comparisons; (3) social aspects of SM use: cyberbullying, social support, and parental involvement; and (4) disclosure of mental health symptoms: online disclosure and prediction of symptoms and suicide contagion effect ( Figure 2 ).

Number of studies by theme (quantity, quality, social and disclosure) and time period (2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016 and 2017–2018).

Quantity of SM use

The majority of studies ( n = 24) examined quantity of SM use by measuring either frequency or time spent on SM ( n = 17), or problematic or addictive engagement with SM ( n = 7).

Frequency of use

The majority of studies found a positive correlation between time spent on SNS and higher levels of The majority of studies found a positive correlation between time spent on SNS and higher levels of depression ( Akkın Gürbüz, Demir, Gökalp Özcan, Kadak, & Poyraz, 2017 ; Marengo, Longobardi, Fabris & Settanni, 2018 ; Pantic et al., 2012 ; Twenge et al., 2018 ; Woods & Scott, 2016 ). Higher frequency of SM use (≥2 h a day) was also found to be positively associated with suicidal ideation ( Sampasa-Kanyinga & Lewis, 2015 ) and attempts ( Sampasa-Kanyinga & Hamilton, 2015 ), in addition to deficits in self-regulation ( Lee, Ho, & Lwin, 2017 ). Factors such as the number of SM accounts and the frequency of checking SM ( Barry, Sidoti, Briggs, Reiter, & Lindsey, 2017 ) were associated with a variety of symptoms, including depression.

A study ( Oberst, Wegmann, Stodt, Brand, & Chamarro, 2017 ) examining SM use as an outcome suggested that depression may affect SM use both directly, and indirectly, mediated by the Fear of Missing Out (or the apprehension of missing rewarding experiences that others might be enjoying) ( Przybylski, Murayama, DeHaan, & Gladwell, 2013 ). Adolescents with depression were also found to have more difficulty regulating their SM use ( Lee et al., 2017 ).

Longitudinal studies suggested a reciprocal relationship between quantity of SM use and depression. Frison and Eggermont (2017) found that frequency of Instagram browsing at baseline predicted depressed mood six months later and depressed mood at baseline predicted later frequency of photo posting. Additionally, heavy use (>4 h per day) of the internet to communicate (including social networking) and play games (gaming) predicted depressive symptoms a year later ( Romer, Bagdasarov, & More, 2013 ). Further, depressive symptoms predicted increased internet use and decreased participation in non-screen activities (e.g. sports). Finally, Salmela-Aro, Upadyaya, Hakkarainen, Lonka, and Alho (2017) found that school burnout increased the risk for later excessive internet use and depressive symptoms. Conversely, Houghton et al. (2018) found small, positive bi-directional associations between depressive symptoms and screen use 1 year later, but their final model did not support a longitudinal association.

Yet, not all studies found a positive association between frequency of use and depressed mood. While Blomfield-Neira and Barber (2014) reported a link between adolescents having a SM profile and depressed mood, they found no correlation between SM frequency of use and depressed mood. Rather, investment in SM (a measure of how important SM is to an adolescent) was linked to poorer adjustment, lower self-esteem and depressed mood. Moderate SM use (a stable trend in the time spent on SM during adolescence and into early adulthood that did not interfere with functioning) was associated with better emotional self-regulation ( Coyne, Padilla-Walker, Holmgren, & Stockdale, 2018 ) and healthier development, especially when used to acquire information ( Romer et al., 2013 ). Finally, Rodriguez Puentes and Parra (2014) found a positive association between SM and externalizing behaviours, but no significant association between SM use and depression.

Additionally, age moderated the effects of frequency of use on depression. For example, in one study, older adolescents with higher SM use had higher ‘offline’ social competence, while younger adolescents with higher SM use had more internalizing problems and diminished academics and activities ( Tsitsika, Janikian, et al., 2014 ).

Problematic SM use

Seven studies explored problematic use or engagement with SM or the internet in an addictive manner (a dysfunctional pattern of behaviour similar to that of impulse control disorders, which causes distress and/or functional impairment) ( Critselis et al., 2014 ).

An addiction-like pattern of internet use (including SM use) was associated with emotional maladjustment ( Critselis et al., 2014 ), internalizing and externalizing symptoms ( Tsitsika, Tzavela, et al., 2014 ), and depressive mood ( Van Rooij, Ferguson, Van de Mheen, & Schoenmakers, 2017 ). Further, depressive mood predicted problematic internet use (both SM and gaming, independently) ( Kırcaburun et al., 2018 ; Van Rooij et al., 2017 ).

Bányai et al. (2017) assessed the prevalence of problematic internet use conducting a latent profile analysis to describe classes of users and found that the class described as ‘at risk’ for problematic internet and SM use tended to be female, use the internet for longer periods, and have lower self-esteem and more depressive symptoms. Yet, while Banjanin, Banjanin, Dimitrijevic, and Pantic (2015) found a positive correlation between internet addiction and depression in high school students (particularly for females), no such correlation was found with engagement with SM (measured by number of pictures posted).

Several studies examined mediators of the association of problematic SM use and depression. Wang et al. (2018) found that rumination mediated the relationship between SM addiction and adolescent depression, with a stronger effect among adolescents with low self-esteem. Additionally, insomnia partially mediated the association between SM addiction and depressive symptoms ( Li et al., 2017 ). Woods and Scott (2016) found that nighttime-specific SM use (in addition to overall use and emotional investment in SM) was associated with poorer sleep quality, anxiety and depressive symptoms. Finally, problematic SM use mediated the association between depressive symptoms and cyberbullying perpetration ( Kırcaburun et al., 2018 ).

Quality of SNS use

In addition to the frequency of adolescents’ engagement with SM, another focus of research has been the ways in which adolescents engage with SM. Of the studies selected, four primarily examined engagement styles with SM and two specifically examined social comparisons with other users.

Characteristics of SM use

The ways in which adolescents use SM may also have an effect on depression. One study ( Frison & Eggermont, 2016 ) characterized SM use as public (e.g. updating one’s status on a profile) vs private (e.g. messaging), and active (e.g. interacting with others on SM) vs passive (e.g. browsing on SM) and found that public Facebook use was associated with adolescent depressed mood. Among girls, passive use of Facebook yielded negative outcomes such as depressed mood, while active use yielded positive outcomes such as perceived social support ( Frison & Eggermont, 2016 ). A longitudinal study of Flemish adolescents by the same group ( Frison & Eggermont, 2017 ) found passive SM use at baseline to predict depressive symptoms 7 months later, while depressive symptoms predicted active use of SM. Interestingly, there was no association between depressive symptoms and Facebook use (frequency of use, network size, self-presentation, and peer interaction) in a study conducted among healthy adolescents ( Morin-Major et al., 2016 ).

Romer et al. (2013) found that the types of internet activities utilized (e.g. SNS, blogs, etc.) were associated with the frequency of self-reported depression-like symptoms. Additionally, using the internet for information searching was associated with higher grades, more frequent participation in clubs, and lower reports of depressive symptoms, while using the internet more than 4 h per day to communicate or play games was associated with greater depression-like symptoms, suggesting that Internet use for acquiring information is associated with healthy development.

A qualitative study further explored positive and negative aspects of SM use among adolescents diagnosed with clinical depression ( Radovic, Gmelin, Stein, & Miller, 2017 ). Participants described positive SM use as including searching for positive content (e.g. entertainment, humour, content creation) or social connection, while they described negative SM use as sharing risky behaviours, cyberbullying, or making self-denigrating comparisons with others. Furthermore, this study found that adolescents’ use of SM shifted from negative to positive during the course of treatment.

Social comparisons

Two studies examined social comparisons made through SM and the association with depression. Nesi and Prinstein (2015) found that technology-based social comparison and feedback-seeking were associated with depressive symptoms, even when controlling for the effects of overall frequency of technology use, offline excessive reassurance-seeking, and prior depressive symptoms. This association was strongest among females and adolescents low in popularity (as measured by peer report). Niu et al. (2018) found that negative social comparisons mediated the association between Qzone use (a Chinese SM site) and depression, and that the association between Qzone use and negative social comparisons was stronger among individuals with low self-esteem. However, there was no direct effect of Qzone use on depression. An additional study that primarily focussed on studying frequency of use ( Marengo et al., 2018 ) found that increased use of highly visual SM (e.g. Instagram) predicted internalizing symptoms and body image concerns in a student sample. Moreover, in this study, the effect of highly visual SM on internalizing symptoms was mediated by body image concerns.

Social aspects of SM use

Several studies looked at the social aspects of engagement with SM, either by evaluating the effects of cybervictimization ( n = 4) on depression, parental involvement both through monitoring of SM use or direct engagement with the adolescent ( n = 3), and aspects of social support received by the adolescent within and outside of SNS ( n = 2).

Cyberbullying/cybervictimization

Four studies examined cyberbullying via SM and depressive symptoms. Duarte, Pittman, Thorsen, Cunningham, and Ranney (2018) found that symptoms of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation were more prevalent among participants who reported any past-year cyberbullying (either victimization or perpetration). After adjusting for a range of demographic factors, only lesbian, gay, and bisexual status correlated with cyberbullying involvement or adverse mental health outcomes. Another study found that cyberbullying victimization fully mediated the association between SM use and psychological distress and suicide attempts ( Sampasa-Kanyinga & Hamilton, 2015 ). Furthermore, a 12-month longitudinal study found that cybervictimization predicted later depressive symptoms ( Cole et al., 2016 ). Depressive symptoms have also been shown to be a risk factor (rather than an outcome) for cybervictimization on Facebook ( Frison, Subrahmanyam, & Eggermont, 2016 ), showing evidence of the bi-directionality of this association.

Social support

While many studies examined potential negative effects of SM use, some studies examined the positive effects of SM use on youth outcomes, including social support. Frison and Eggermont (2015) found that adolescents seeking social support through Facebook had improved depressive symptoms if support was received, but worsened symptoms if support was not received. This pattern was not found in non-virtual social support contexts, suggesting differences in online and traditional social support contexts. A later study that primarily focussed on the characteristics of SM use ( Frison & Eggermont, 2016 ) found that perception of online support was particularly protective against depressive symptoms in girls with ‘active’ Facebook use (e.g. those who update their status or instant message on Facebook). Finally, Frison et al. (2016) showed that support from friends can be a protective factor of Facebook victimization.

Parental involvement/parental monitoring

Studies examining parent and family role in adolescent SM use and its outcomes were heterogeneous. One study ( Coyne, Padilla-Walker, Day, Harper, & Stockdale, 2014 ) explored adolescent use of SM with parents and found lower internalizing behaviours in participants who used SNS with their parents (mediated by feelings of parent/child connection). Another study ( Fardouly, Magson, Johnco, Oar, & Rapee, 2018 ) examined parent control over preadolescents’ time spent on SM and found no association between parental control and preadolescent depressive symptoms.

Family relationships offline were also associated with adolescent outcomes. Isarabhakdi and Pewnil (2016) examined adolescents’ engagement with offline relationships and found improved mental health outcomes with higher involvement in family activities and with peers, while internet use did not significantly improve mental well-being. This finding suggests that in-person support systems were more effective for the promotion of mental well-being. Interestingly, in Szwedo, Mikami, and Allen (2011) , negative interactions with mothers during early adolescence were associated with youth preferring online versus face-to-face communication, experiencing more negative interactions on webpages, and forming close friendships with someone they met online 7 years later. An additional study that primarily focussed on suicide contagion ( Tseng & Yang, 2015 ) found that family support was protective for both males and females, while friend support was protective only for females. However, ‘significant other’ support was a risk factor for suicidal plans among females.

Disclosure of mental health symptoms on SM

A few of the studies selected focussed on studying the disclosure of depressive symptoms on SM and explored the potential of disclosure of symptoms of distress on SM to predict depression and suicide, in addition to the phenomenon of suicide contagion.

Online disclosure and prediction of mental health symptoms

Although content analysis is a method theorized to have potential to predict and prevent non-suicidal and suicidal self-injurious behaviours, the data are mixed. Ophir, Asterhan, and Schwarz (2019) examined the predictive validity of explicit references to personal distress in adolescents’ Facebook postings, comparing these postings with external, self-report measures of psychological distress (e.g. depression) and found that most depressed adolescents did not publish explicit references to depression. Additionally, adolescents published less verbal content than adult users of SNS. Conversely, Akkın Gürbüz et al. (2017) found that while disclosures of depressed mood were frequent among both depressed and non-depressed adolescents, those who were depressed shared more negative feelings, anhedonia, and suicidal thoughts on SM than those who were not depressed.

Suicide contagion effect

One longitudinal study examined suicide contagion effects ( Dunlop, More, & Romer, 2011 ) finding that even though traditional SNS (e.g. Facebook or MySpace) were a significant source of exposure to suicide stories, this exposure was not associated with increases in suicidal ideation one year later. On the other hand, exposure to online discussion forums (including self-help forums) did predict increases in suicidal ideation over time. Notably, this study found that in a quarter of the sample, the exposure to suicide stories took place through SM. Another study ( Tseng & Yang, 2015 ) found that higher importance attributed to web communication (e.g. chatting or making friends online) was associated with increased risk of self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in boys.

The recent rise in the prevalence of depression and suicide among adolescents has coincided with an increase in screen-related activities, including SM use ( Twenge et al., 2018 ), sparking an interest in investigating the effects of SM use on adolescent mental health. This interest has given rise to a broad scope of research, ranging from observational to experimental and qualitative studies through interviews or analysis of SM content, and systematic studies. This scoping review aimed to understand the breadth of research in the area of depression and SM (with a focus on SNS) and to identify the existing research gaps.

We identified four main themes of research, including (1) the quantity of SM use; (2) the quality of SM use; (3) social aspects associated with SM use; and (4) SM as a tool for disclosure of mental health symptoms and potential for prediction and prevention of depression and suicide outcomes.

Most research on SM and depressive symptoms has focussed on the effects of frequency of SM use and problematic SM use. The majority of articles included in this review demonstrated a positive and bi-directional association between frequency of SM use and depression and in some instances even suicidality. Yet some questions remain to be determined, including to what degree adolescents’ personal vulnerabilities and characteristics of SM use moderate the association between SM use and depression or suicidality, and whether other environmental factors, such as family support and/or monitoring, or cultural differences influence this association. Although moderate SM use may be associated with better self-regulation, it is unclear if this is due to moderate users being better at self-regulation.

Findings from the studies examining problematic SM use were consistent with prior studies linking problematic internet use with a variety of psychosocial outcomes including depressive symptoms ( Reid Chassiakos et al., 2016 ). Though limited in number, studies reviewed here suggested that problematic or addictive SM use may be more common in females ( Banyai et al., 2017 ; Kırcaburun et al., 2018 ) and in those starting use at a younger age ( Tsitsika, Janikian, et al., 2014 ). These findings suggest a possible role of screening for addictive SM use, with a particular focus on risk stratification for younger and female adolescents.

With respect to the effects of patterns and types of SM use, studies reviewed here suggest possible differential effects between passive and active, and private versus public SM use. This suggests that screening only for time spent on SM may be insufficient. Moreover, though there are types of SM use that have adverse mental health effects for adolescents (e.g. addictive patterns, nighttime use), other types of SM use, such as for information searching or receiving social support, may have a positive effect ( Coyne et al., 2018 ; Frison & Eggermont, 2016 ; Romer et al., 2013 ). Furthermore, over time, depressed adolescents can successfully shift their use of SM from negative (e.g. cyberbullying) to positive (e.g. searching for humour), possibly through increasing awareness of the effect of SM use on their mood ( Radovic et al., 2017 ). Given the ubiquity of SM use, these results suggest that interventions targeting changes in adolescents’ use of SM may be fruitful in improving their mental health.

Consistent with prior research ( Feinstein et al., 2013 ), studies examining social comparisons found significant associations between social comparisons made via SM and depression. The tendency of individuals to share more positive depictions of themselves on SM ( Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008 ), and the increased opportunities for comparisons ( Steers, Wickham, & Acitelli, 2014 ) may suggest a confluence of risks for depression and an important avenue for interventions. Moreover, the studies reviewed and previous findings ( Buunk & Gibbons, 2007 ) suggest that individuals with low self-esteem may be at higher risk for the negative effects of social comparisons on mental health.

As previously shown ( Cénat et al., 2014 ), most studies found cyberbullying (either perpetration or victimization) was either associated with mental health problems ( Cole et al., 2016 ; Duarte et al., 2018 ) or moderated the relationship between SM use and depression and suicidality ( Sampasa-Kanyinga & Hamilton, 2015 ). Additionally, cyberbullying may be a distinctive form of victimization that requires further investigation in order to understand its impact on adolescent mental health ( Dempsey, Sulkowski, Nichols, & Storch, 2009 ).

Studies examining social support highlight the association of both depressed mood and low in-person social support with social networking and online support-seeking ( Frison & Eggermont, 2015 ). Moreover, while social support online can be beneficial ( Frison & Eggermont, 2015 ), excessive reliance on online communication and support may be problematic ( Twenge et al., 2018 ). Of note, parental involvement both positively and negatively affected SM use and adolescent outcomes. These mixed findings suggest a need to include parental relationships in research (both via online and ‘offline’ communication), to better understand their role in adolescents’ SM use and depression.

Surprisingly, depressed adolescents were not more likely to publish explicit references to depression on SM platforms than their healthy peers ( Ophir et al., 2019 ) which suggests that screening for depression via SM may not be useful when used alone. However, some depressed adolescents posted more negative feelings, anhedonia and suicidal ideation ( Akkın Gürbüz et al., 2017 ), suggesting that SM may be used as a supplemental tool to track the course of depressive mood over time and start discussions about mental health.

Suicide contagion effect is a relatively understudied area, despite concerns raised that increased exposure to SM may amplify this effect ( Bell, 2014 ). Given that adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the group contagion effect of suicide ( Stack, 2003 ) and the potential for increased exposure to suicide stories online ( Dunlop et al., 2011 ), interventions to limit this exposure could decrease suicide contagion.

The studies reviewed identified several potential moderators of the association between SM use and adolescent depression, including age and gender. The differential effects of SM use on mental health depending on the age of the adolescent ( Tsitsika, Tzavela, et al., 2014 ) are not surprising given the developmental differences in social and mood regulation skills between younger and older adolescents. Likewise, potential mediators of the effects of SM on mental health such as social comparisons ( Niu et al., 2018 ), body image concerns ( Marengo et al., 2018 ), perceived support online ( Frison & Eggermont, 2015 ), and parent–child relationship ( Coyne et al., 2014 ) may also be important targets for future interventions.

The studies reviewed present several limitations. Most studies were cross-sectional and could not elucidate the directionality of the association between SM use and depression. Most of the studies included self-report rather than clinician-administered measures of depression, and retrospective reports, asking participants to report on past activities. Newer methods that measure actual (and not just reported) use (e.g. news feed activity, number of likes and comments) and more frequent and timely reports of SM use (e.g. diaries) could more accurately explain these associations. Another limitation is that many of the studies recruited participants in schools, limiting the generalizability to clinical samples. It is possible that those students not in school were spending more time on SM and/or experiencing more depressive symptoms. Most studies included general assessments of SM without specifying whether the use was limited to SNS or other forms of SM or internet use. While we tried to narrow our search to studies that explicitly included questions on SNS use, many also asked about other types of SM use. Separating the different types of SM use may be difficult when asking for adolescents’ self-reports, but more immediate measures of mood symptoms and SNS use could be more specific and informative. Finally, while some studies included contextual factors such as the educational and family environments, other contextual factors such as ethnicity and cultural context are areas of potential for investigation.

Conclusions

In summary, extensive research on the quantity and quality of SM use has shown an association between SM use and depression in adolescents. Given that most studies are cross-sectional, longitudinal research would help assess the direction of this association. At the same time, some aspects of SM use may have a beneficial effect on adolescent well-being, such as the ability to have diversity of friendships and easily accessed supports. Furthermore, the use of SM content to detect symptoms has potential in depression and suicide prevention. Finally, moderators of the association between SM and adolescent depression and suicidality (e.g. gender, age, parental involvement) are areas to explore that would allow more targeted interventions. Since SM will remain an important facet of adolescents’ lives, a better understanding of the mechanisms of its relationship with depression could be beneficial to increase exposure to mental health interventions and promote well-being.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of Jaime Blanck, MLIS, MPA for her help with the search and retrieval of full-text articles.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Vidal is supported by the Stravos Niarchos Foundation. Ms. Lhaksampa and Dr. Miller are supported by the Once Upon a Time Foundation. Drs. Miller and Dr. Platt are supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Dr. Platt is supported by the NIMH 1K23MH118431 and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

- Akkın Gürbüz HG, Demir T, Gökalp Özcan B, Kadak MT, & Poyraz BC (2017). Use of social network sites among depressed adolescents . Behaviour & Information Technology , 36 , 517–523. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2016.1262898 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson EL, Steen E, & Stavropoulos V (2017). Internet use and problematic internet use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood . International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , 22 , 430–454. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework . International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 ( 1 ), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Banjanin N, Banjanin N, Dimitrijevic I, & Pantic I (2015). Relationship between internet use and depression: Focus on physiological mood oscillations, social networking and online addictive behavior . Computers in Human Behavior , 43 , 308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.013 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, … Demetrovics Z (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample . PLoS One , 12 ( 1 ), e0169839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barry CT, Sidoti CL, Briggs SM, Reiter SR, & Lindsey RA (2017). Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives . Journal of Adolescence , 61 , 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.005 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baym NK (2010). Personal connections in the digital age . Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baym NK, Zhang YB, & Lin MC (2004). Social interactions across media: Interpersonal communication on the internet, telephone and face-to-face . New Media & Society , 6 , 299–318. doi: 10.1177/1461444804041438 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell J (2014). Harmful or helpful? The role of the Internet in self-harming and suicidal behaviour in young people . Mental Health Review Journal , 19 ( 1 ), 61–71. doi: 10.1108/MHRJ-05-2013-0019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Best P, Manktelow R, & Taylor B (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review . Children and Youth Services Review , 41 , 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blomfield-Neira CJ, & Barber BL (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood . Australian Journal of Psychology , 66 ( 1 ), 56–64. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12034 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buunk AP, & Gibbons FX (2007). Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field . Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 102 ( 1 ), 3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2017). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online] . Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars . Accessed July 19, 2019.

- Cénat JM, Hébert M, Blais M, Lavoie F, Guerrier M, & Derivois D (2014). Cyberbullying, psychological distress and self-esteem among youth in Quebec schools . Journal of Affective Disorders , 169 , 7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.019 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole DA, Zelkowitz RL, Nick E, Martin NC, Roeder KM, Sinclair-McBride K, & Spinelli T (2016). Longitudinal and incremental relation of cybervictimization to negative self-cognitions and depressive symptoms in young adolescents . Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology , 44 , 1321–1332. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0123-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, Day RD, Harper J, & Stockdale L (2014). A friend request from dear old dad: Associations between parent–child social networking and adolescent outcomes . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 17 ( 1 ), 8–13. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0623 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyne SM, Padilla-Walker LM, Holmgren HG, & Stockdale LA (2018). Instagrowth: A longitudinal growth mixture model of social media time use across adolescence . Journal of Research on Adolescence , 29 , 897–907. doi: 10.1111/jora.12424 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Critselis E, Janikian M, Paleomilitou N, Oikonomou D, Kassinopoulos M, Kormas G, & Tsitsika A (2014). Predictive factors and psychosocial effects of Internet addictive behaviors in Cypriot adolescents . International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health , 26 , 369–375. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0313 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dempsey AG, Sulkowski ML, Nichols R, & Storch EA (2009). Differences between peer victimization in cyber and physical settings and associated psychosocial adjustment in early adolescence . Psychology in the Schools , 46 , 962–972. doi: 10.1002/pits.20437 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duarte C, Pittman SK, Thorsen MM, Cunningham RM, & Ranney ML (2018). Correlation of minority status, cyberbullying, and mental health: A cross-sectional study of 1031 adolescents . Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma , 11 ( 1 ), 39–48. doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0201-4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunlop SM, More E, & Romer D (2011). Where do youth learn about suicides on the Internet, and what influence does this have on suicidal ideation . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 52 , 1073–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02416.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fardouly J, Magson NR, Johnco CJ, Oar EL, & Rapee RM (2018). Parental control of the time preadolescents spend on social media: Links with preadolescents’ social media appearance comparisons and mental health . Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 47 , 1456–1468. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0870-1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feinstein BA, Hershenberg R, Bhatia V, Latack JA, Meuwly N, & Davila J (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism . Psychology of Popular Media Culture , 2 , 161–110. doi: 10.1037/a0033111 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frison E, & Eggermont S (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents’ depressed mood: The role of social support seeking through Facebook . Computers in Human Behavior , 44 , 315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frison E, & Eggermont S (2016). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood . Social Science Computer Review , 34 , 153–171. doi: 10.1177/0894439314567449 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frison E, & Eggermont S (2017). Browsing, posting, and liking on Instagram: The reciprocal relationships between different types of Instagram use and adolescents’ depressed mood . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 20 , 603–609. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0156 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frison E, Subrahmanyam K, & Eggermont S (2016). The short-term longitudinal and reciprocal relations between peer victimization on Facebook and adolescents’ well-being . Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 45 , 1755–1771. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0436-z [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guernsey L (2014). Garbled in translation: Getting media research to the press and public . Journal of Children and Media , 8 ( 1 ), 87–94. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2014.863486 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Houghton S, Lawrence D, Hunter SC, Rosenberg M, Zadow C, Wood L, & Shilton T (2018). Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence . Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 47 , 2453–2467. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0901-y [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Isarabhakdi P, & Pewnil T (2016). Engagement with family, peers, and Internet use and its effect on mental well-being among high school students in Kanchanaburi Province , Thailand. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , 21 ( 1 ), 15–26. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2015.1024698 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keles B, McCrae N, & Grealish A (2019). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents . International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , 25 , 79–93. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kırcaburun K, Kokkinos CM, Demetrovics Z, Király O, Griffiths MD, & Çolak TS (2018). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors . International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , 17 , 891–908. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9894-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kowalski RM, Limber S, & Agatston PW (2012). Cyberbullying: Bullying in the digital age (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, Cummings J, Helgeson V, & Crawford A (2002). Internet paradox revisited . Journal of Social Issues , 58 ( 1 ), 49–74. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00248 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukophadhyay T, & Scherlis W (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist , 53 , 1017–1031. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1017 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee EW, Ho SS, & Lwin MO (2017). Extending the social cognitive model—Examining the external and personal antecedents of social network sites use among Singaporean adolescents . Computers in Human Behavior , 67 , 240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.030 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li JB, Lau JT, Mo PK, Su XF, Tang J, Qin ZG, & Gross DL (2017). Insomnia partially mediated the association between problematic Internet use and depression among secondary school students in China . Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 6 , 554–563. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.085 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manning J (2014). Social media, definition and classes of In Harvey K (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social media and politics (pp. 1158–1162). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marengo D, Longobardi C, Fabris MA, & Settanni M (2018). Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns . Computers in Human Behavior , 82 , 63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCrae N, Gettings S, & Purssell E (2017). Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review . Adolescent Research Review , 2 , 315–330. doi: 10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miron O, Yu K, Wilf-Miron R, & Kohane IS (2019). Suicide rates among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2000–2017 . JAMA , 321 , 2362–2364. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5054 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, & Han B (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults . Pediatrics , 138 , e20161878. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin-Major JK, Marin MF, Durand N, Wan N, Juster RP, & Lupien SJ (2016). Facebook behaviors associated with diurnal cortisol in adolescents: Is befriending stressful? Psychoneuroendocrinology , 63 , 238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.005 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nesi J, & Prinstein MJ (2015). Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms . Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology , 43 , 1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nie NH, Hillygus DS, & Erbring L (2002). Internet use, interpersonal relations, and sociability: A time diary study In Wellman B & Haythornthwaite C (Eds.), The Internet in everyday life (pp. 215–243). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ]

- Niu GF, Luo YJ, Sun XJ, Zhou ZK, Yu F, Yang SL, & Zhao L (2018). Qzone use and depression among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model . Journal of Affective Disorders , 231 , 58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.013 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oberst U, Wegmann E, Stodt B, Brand M, & Chamarro A (2017). Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out . Journal of Adolescence , 55 , 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ophir Y, Asterhan CS, & Schwarz BB (2019). The digital footprints of adolescent depression, social rejection and victimization of bullying on Facebook . Computers in Human Behavior , 91 , 62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.09.025 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, Topalovic D, Bojovic-Jovic D, Ristic S, & Pantic S (2012). Association between online social networking and depression in high school students: Behavioral physiology viewpoint . Psychiatria Danubina , 24 ( 1 ), 90–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center. (2018a). Teens, social media and technology 2018 . Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- Pew Research Center. (2018b). Teens’ social media habits and experiences . Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/11/28/teens-social-media-habits-and-experiences/

- Przybylski AK, Murayama K, DeHaan CR, & Gladwell V (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out . Computers in Human Behavior , 29 , 1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Radovic A, Gmelin T, Stein BD, & Miller E (2017). Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media . Journal of Adolescence , 55 , 5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reid Chassiakos YL, Radesky J, Christakis D, Moreno MA, Cross C; Council on Communications and Media. (2016). Children and adolescents and digital media . Pediatrics , 138 , e20162593. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2593 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson JP, Kestnbaum M, Neustadtl A, & Alvarez AS (2002). The Internet and other uses of time In Wellman B & Haythornthwaite C (Eds.), The Internet in everyday life (pp. 244–262). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodriguez Puentes AP, & Parra AF (2014). Relación entre el tiempo de uso de las redes sociales en internet yla salud mental en adolescentes colombianos . Acta Colombiana de Psicología , 17 ( 1 ), 131–140. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2014.17.1.13 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Romer D, Bagdasarov Z, & More E (2013). Older versus newer media and the well-being of United States youth: Results from a national longitudinal panel . Journal of Adolescent Health , 52 , 613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Salmela-Aro K, Upadyaya K, Hakkarainen K, Lonka K, & Alho K (2017). The dark side of internet use: Two longitudinal studies of excessive internet use, depressive symptoms, school burnout and engagement among Finnish early and late adolescents . Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 46 , 343–357. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0494-2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, & Hamilton HA (2015). Social networking sites and mental health problems in adolescents: The mediating role of cyberbullying victimization . European Psychiatry , 30 , 1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.09.011 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, & Lewis RF (2015). Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 18 , 380–385. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0055 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stack S (2003). Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide . Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health , 57 , 238–240. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.238 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steers MLN, Wickham RE, & Acitelli LK (2014). Seeing everyone else’s highlight reels: How Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms . Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 33 , 701–731. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.8.701 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Subrahmanyam K, & Greenfield P (2008). Online communication and adolescent relationships . The Future of Children , 18 ( 1 ), 119–146. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0006 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szwedo DE, Mikami AY, & Allen JP (2011). Qualities of peer relations on social networking websites: Predictions from negative mother–teen interactions . Journal of Research on Adolescence , 21 , 595–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00692.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tseng FY, & Yang HJ (2015). Internet use and web communication networks, sources of social support, and forms of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: Different patterns between genders . Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior , 45 , 178–191. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12124 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsitsika A, Janikian M, Schoenmakers TM, Tzavela EC, Ólafsson K, Wójcik S, … Richardson C (2014). Internet addictive behavior in adolescence: A cross-sectional study in seven European countries . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 17 , 528–535. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0382 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsitsika AK, Tzavela EC, Janikian M, Ólafsson K, Iordache A, Schoenmakers TM, … Richardson C (2014). Online social networking in adolescence: Patterns of use in six European countries and links with psychosocial functioning . Journal of Adolescent Health , 55 ( 1 ), 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.010 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, & Martin GN (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time . Clinical Psychological Science , 6 ( 1 ), 3–17. doi: 10.1177/2167702617723376 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Rooij AJ, Ferguson CJ, Van de Mheen D, & Schoenmakers TM (2017). Time to abandon Internet Addiction? Predicting problematic Internet, game, and social media use from psychosocial well-being and application use . Clinical Neuropsychiatry , 14 ( 1 ), 113–121. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang P, Wang X, Wu Y, Xie X, Wang X, Zhao F, … Lei L (2018). Social networking sites addiction and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of rumination and self-esteem . Personality and Individual Differences , 127 , 162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang H, & Wellman B (2010). Social connectivity in America: Changes in adult friendship network size from 2002 to 2007 . American Behavioral Scientist , 53 , 1148–1169. doi: 10.1177/0002764209356247 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woods HC, & Scott H (2016). #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem . Journal of Adolescence , 51 , 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Software Engineering

Title: systematic literature review of commercial participation in open source software.

Abstract: Open source software (OSS) has been playing a fundamental role in not only information technology but also our social lives. Attracted by various advantages of OSS, increasing commercial companies take extensive participation in open source development and have had a broad impact. This paper provides a comprehensive systematic literature review (SLR) of existing research on company participation in OSS. We collected 92 papers and organized them based on their research topics, which cover three main directions, i.e., participation motivation, contribution model, and impact on OSS development. We found the explored motivations of companies are mainly from economic, technological, and social aspects. Existing studies categorize companies' contribution models in OSS projects mainly through their objectives and how they shape OSS communities. Researchers also explored how commercial participation affects OSS development. We conclude with research challenges and promising research directions on commercial participation in OSS. This study contributes to a comprehensive understanding of commercial participation in OSS development.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) de ne social media as "a group of Internet-based. applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web. 2.0, and that allow the creation and ...

In business world social media became popular after 2012 and academic literature also indicates social media evolved after 2000 ( Boyd & Ellison, 2007 ). Therefore, the document published in 2000 and after had been considered for the review only. Firstly the keyword "social media" was searched in Scopus database.

This systematic literature review has revealed that the second-most used theory in social media for knowledge sharing research, is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). This model explains the perceptions of using new technologies, with a focus on ease of use and usefulness, in turn effecting the intention of adopting social media as a tool ...