Literary Genres: Definition and Examples of the 4 Essential Genres and 100+ Subgenres

by Joe Bunting | 1 comment

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

What are literary genres? Do they actually matter to readers? How about to writers? What types of literary genres exist? And if you're a writer, how do you decide which genre to write in?

To begin to think about literary genres, let's start with an example.

Let's say want to read something. You go to a bookstore or hop onto a store online or go to a library.

But instead of a nice person wearing reading glasses and a cardigan asking you what books you like and then thinking through every book ever written to find you the next perfect read (if that person existed, for the record, they would be my favorite person), you're faced with this: rows and rows of books with labels on the shelves like “Literary Fiction,” “Travel,” “Reference,” “Science Fiction,” and so on.

You stop at the edge of the bookstore and just stand there for a while, stumped. “What do all of these labels even mean?!” And then you walk out of the store.

Or maybe you're writing a book , and someone asks you a question like this: “What kind of book are you writing? What genre is it?”

And you stare at them in frustration thinking, “My book transcends genre, convention, and even reality, obviously. Don't you dare put my genius in a box!”

What are literary genres? In this article, we'll share the definition and different types of literary genres (there are four main ones but thousands of subgenres). Then, we'll talk about why genre matters to both readers and writers. We'll look at some of the components that people use to categorize writing into genres. Finally, we'll give you a chance to put genre into practice with an exercise .

Table of Contents

Introduction Literary Genres Definition Why Genre Matters (to Readers, to Writers) The 4 Essential Genres 100+ Genres and Subgenres The 7 Components of Genre Practice Exercise

Ready to get started? Let's get into it.

What Are Literary Genres? Literary Genre Definition

Let's begin with a basic definition of literary genres:

Literary genres are categories, types, or collections of literature. They often share characteristics, such as their subject matter or topic, style, form, purpose, or audience.

That's our formal definition. But here's a simpler way of thinking about it:

Genre is a way of categorizing readers' tastes.

That's a good basic definition of genre. But does genre really matter?

Why Literary Genres Matter

Literary genres matter. They matter to readers but they also matter to writers. Here's why:

Why Literary Genres Matter to Readers

Think about it. You like to read (or watch) different things than your parents.

You probably also like to read different things at different times of the day. For example, maybe you read the news in the morning, listen to an audiobook of a nonfiction book related to your studies or career in the afternoon, and read a novel or watch a TV show in the evening.

Even more, you probably read different things now than you did as a child or than you will want to read twenty years from now.

Everyone has different tastes.

Genre is one way we match what readers want to what writers want to write and what publishers are publishing.

It's also not a new thing. We've been categorizing literature like this for thousands of years. Some of the oldest forms of writing, including religious texts, were tied directly into this idea of genre.

For example, forty percent of the Old Testament in the Bible is actually poetry, one of the four essential literary genres. Much of the New Testament is in the form of epistle, a subgenre that's basically a public letter.

Genre matters, and by understanding how genre works, you not only can find more things you want to read, you can also better understand what the writer (or publisher) is trying to do.

Why Literary Genres Matter to Writers

Genre isn't just important to readers. It's extremely important to writers too.

In the same way the literary genres better help readers find things they want to read and better understand a writer's intentions, genres inform writers of readers' expectations and also help writers find an audience.

If you know that there are a lot of readers of satirical political punditry (e.g. The Onion ), then you can write more of that kind of writing and thus find more readers and hopefully make more money. Genre can help you find an audience.

At the same time, great writers have always played with and pressed the boundaries of genre, sometimes even subverting it for the sake of their art.

Another way to think about genre is a set of expectations from the reader. While it's important to meet some of those expectations, if you meet too many, the reader will get bored and feel like they know exactly what's going to happen next. So great writers will always play to the readers' expectations and then change a few things completely to give readers a sense of novelty in the midst of familiarity.

This is not unique to writers, by the way. The great apparel designer Virgil Abloh, who was an artistic director at Louis Vuitton until he passed away tragically in 2021, had a creative template called the “3% Rule,” where he would take an existing design, like a pair of Nike Air Jordans, and make a three percent change to it, transforming it into something completely new. His designs were incredibly successful, often selling for thousands of dollars.

This process of taking something familiar and turning it into something new with a slight change is something artists have done throughout history, including writers, and it's a great way to think about how to use genre for your own writing.

What Literary Genre is NOT: Story Type vs. Literary Genres

Before we talk more about the types of genre, let's discuss what genre is not .

Genre is not the same as story type (or for nonfiction, types of nonfiction structure). There are ten (or so) types of stories, including adventure, love story, mystery, and coming of age, but there are hundreds, even thousands of genres.

Story type and nonfiction book structure are about how the work is structured.

Genre is about how the work is perceived and marketed.

These are related but not the same.

For example, one popular subgenre of literature is science fiction. Probably the most common type of science fiction story is adventure, but you can also have mystery sci-fi stories, love story sci-fi, and even morality sci-fi. Story type transcends genre.

You can learn more about this in my book The Write Structure , which teaches writers the simple process to structure great stories. Click to check out The Write Structure .

This is true for non-fiction as well in different ways. More on this in my post on the seven types of nonfiction books .

Now that we've addressed why genre matters and what genre doesn't include, let's get into the different literary genres that exist (there are a lot of them!).

How Many Literary Genres Are There? The 4 Essential Genres, and 100+ Genres and Subgenres

Just as everyone has different tastes, so there are genres to fit every kind of specific reader.

There are four essential literary genres, and all are driven by essential questions. Then, within each of those essential genres are genres and subgenres. We will look at all of these in turn, below, as well as several examples of each.

An important note: There are individual works that fit within the gaps of these four essential genres or even cross over into multiple genres.

As with anything, the edges of these categories can become blurry, for example narrative poetry or fictional reference books.

A general rule: You know it when you see it (except, of course, when the author is trying to trick you!).

1. Nonfiction: Is it true?

The core question for nonfiction is, “Is it true?”

Nonfiction deals with facts, instruction, opinion/argument reference, narrative nonfiction, or a combination.

A few examples of nonfiction (more below): reference, news, memoir, manuals, religious inspirational books, self-help, business, and many more.

2. Fiction: Is it, at some level, imagined?

The core question for fiction is, “Is it, at some level, imagined?”

Fiction is almost always story or narrative. However, satire is a form of “fiction” that's structured like nonfiction opinion/essays or news. And one of the biggest insults you can give to a journalist, reporter, or academic researcher is to suggest that their work is “fiction.”

3. Drama: Is it performed?

Drama is a genre of literature that has some kind of performance component. This includes theater, film, and audio plays.

The core question that defines drama is, “Is it performed?”

As always, there are genres within this essential genre, including horror films, thrillers, true crime podcasts, and more.

4. Poetry: Is it verse?

Poetry is in some ways the most challenging literary genre to define because while poetry is usually based on form, i.e. lines intentionally broken into verse, sometimes including rhyme or other poetic devices, there are some “poems” that are written completely in prose called prose poetry. These are only considered poems because the author and/or literary scholars said they were poems.

To confuse things even more, you also have narrative poetry, which combines fiction and poetry, and song which combines poetry and performance (or drama) with music.

Which is all to say, poetry is challenging to classify, but again, you usually know it when you see it.

Next, let's talk about the genres and subgenres within those four essential literary genres.

The 100+ Literary Genres and Subgenres with Definitions

Genre is, at its core, subjective. It's literally based on the tastes of readers, tastes that change over time, within markets, and across cultures.

Thus, there are essentially an infinite number of genres.

Even more, genres are constantly shifting. What is considered contemporary fiction today will change a decade from now.

So take the lists below (and any list of genres you see) as an incomplete, likely outdated, small sample size of genre with definitions.

1. Fiction Genres

Sorted alphabetically.

Action/Adventure. An action/adventure story has adventure elements in its plot line. This type of story often involves some kind of conflict between good and evil, and features characters who must overcome obstacles to achieve their goals .

Chick Lit. Chick Lit stories are usually written for women who interested in lighthearted stories that still have some depth. They often include romance, humor, and drama in their plots.

Comedy. This typically refers to historical stories and plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a happy ending, often with a wedding.

Commercial. Commercial stories have been written for the sole purpose of making money, often in an attempt to cash in on the success of another book, film, or genre.

Crime/Police/Detective Fiction. Crime and police stories feature a detective, whether amateur or professional, who solves crimes using their wits and knowledge of criminal psychology.

Drama or Tragedy. This typically refers to historical stories or plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a sad or tragic ending, often with one or more deaths.

Erotica. Erotic stories contain explicit sexual descriptions in their narratives.

Espionage. Espionage stories focus on international intrigue, usually involving governments, spies, secret agents, and/or terrorist organizations. They often involve political conflict, military action, sabotage, terrorism, assassination, kidnapping, and other forms of covert operations.

Family Saga. Family sagas focus on the lives of an extended family, sometimes over several generations. Rather than having an individual protagonist, the family saga tells the stories of multiple main characters or of the family as a whole.

Fantasy. Fantasy stories are set in imaginary worlds that often feature magic, mythical creatures, and fantastic elements. They may be based on mythology, folklore, religion, legend, history, or science fiction.

General Fiction. General fiction novels are those that deal with individuals and relationships in an ordinary setting. They may be set in any time period, but usually take place in modern times.

Graphic Novel. Graphic novels are a hybrid between comics and prose fiction that often includes elements of both.

Historical Fiction. Historical stories are written about imagined or actual events that occurred in history. They usually take place during specific periods of time and often include real or imaginary characters who lived at those times.

Horror Genre. Horror stories focus on the psychological terror experienced by their characters. They often feature supernatural elements, such as ghosts, vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, monsters, and aliens.

Humor/Satire. This category includes stories that have been written using satire or contain comedic elements. Satirical novels tend to focus on some aspect of society in a critical way.

LGBTQ+. LGBTQ+ novels are those that feature characters who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or otherwise non-heterosexual.

Literary Fiction. Literary fiction novels or stories have a high degree of artistic merit, a unique or experimental style of writing , and often deal with serious themes.

Military. Military stories deal with war, conflict, combat, or similar themes and often have strong action elements. They may be set in a contemporary or a historical period.

Multicultural. Multicultural stories are written by and about people who have different cultural backgrounds, including those that may be considered ethnic minorities.

Mystery G enre. Mystery stories feature an investigation into a crime.

Offbeat/Quirky. An offbeat story has an unusual plot, characters, setting, style, tone, or point of view. Quirkiness can be found in any aspect of a story, but often comes into play when the author uses unexpected settings, time periods, or characters.

Picture Book. Picture book novels are usually written for children and feature simple plots and colorful illustrations . They often have a moral or educational purpose.

Religious/Inspirational. Religious/ inspirational stories describe events in the life of a person who was inspired by God or another supernatural being to do something extraordinary. They usually have a moral lesson at their core.

Romance Genre. Romance novels or stories are those that focus on love between two people, often in an ideal setting. There are many subgenres in romance, including historical, contemporary, paranormal, and others.

Science Fiction. Science fiction stories are usually set in an imaginary future world, often involving advanced technology. They may be based on scientific facts but they are not always.

Short Story Collection . Short story collections contain several short stories written by the same or different authors.

Suspense or Thriller Genre. Thrillers/ suspense stories are usually about people in danger, often involving crimes, natural disasters, or terrorism.

Upmarket. Upmarket stories are often written for and/or focus on upper class people who live in an upscale environment.

Western Genre. Western stories are those that take place in the west during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Characters include cowboys, outlaws, native Americans, and settlers.

2. Nonfiction Genres

From the BISAC categories, a globally accepted system for coding and categorizing books by the Book Industry Standards And Communications group.

Antiques & Collectibles. Nonfiction books about antiques and collectibles include those that focus on topics such as collecting, appraising, restoring, and marketing antiques and collectibles. These books may be written for both collectors and dealers in antique and collectible items. They can range from how-to guides to detailed histories of specific types of objects.

Architecture. Architecture books focus on the design, construction, use, and history of buildings and structures. This includes the study of architecture in general, but also the specific designs of individual buildings or styles of architecture.

Art. Art books focus on visual arts, music, literature, dance, film, theater, architecture, design, fashion, food, and other art forms. They may include essays, memoirs, biographies, interviews, criticism, and reviews.

Bibles. Bibles are religious books, almost exclusively Christian, that contain the traditional Bible in various translations, often with commentary or historical context.

Biography & Autobiography. Biography is an account of a person's life, often a historical or otherwise famous person. Autobiographies are personal accounts of people's lives written by themselves.

Body, Mind & Spirt. These books focus on topics related to human health, wellness, nutrition, fitness, or spirituality.

Business & Economics. Business & economics books are about how businesses work. They tend to focus on topics that interest people who run their own companies, lead or manage others, or want to understand how the economy works.

Computers. The computer genre of nonfiction books includes any topics that deal with computers in some way. They can be about general use, about how they affect our lives, or about specific technical areas related to hardware or software.

Cooking. Cookbooks contain recipes or cooking techniques.

Crafts & Hobbies. How-to guides for crafts and hobbies, including sewing, knitting, painting, baking, woodworking, jewelry making, scrapbooking, photography, gardening, home improvement projects, and others.

Design. Design books are written about topics that include design in some way. They can be about any aspect of design including graphic design, industrial design, product design, fashion, furniture, interior design, or others.

Education. Education books focus on topics related to teaching and learning in schools. They can be used for students or as a resource for teachers.

Family & Relationships. These books focus on family relationships, including parenting, marriage, divorce, adoption, and more.

Foreign Language Study. Books that act as a reference or guide to learning a foreign language.

Games & Activities. Games & activities books may be published for children or adults, may contain learning activities or entertaining word or puzzle games. They range from joke books to crossword puzzle books to coloring books and more.

Gardening. Gardening books include those that focus on aspects of gardening, how to prepare for and grow vegetables, fruits, herbs, flowers, trees, shrubs, grasses, and other plants in an indoor or outdoor garden setting.

Health & Fitness. Health and fitness books focus on topics like dieting, exercise, nutrition, weight loss, health issues, medical conditions, diseases, medications, herbs, supplements, vitamins, minerals, and more.

History. History books focus on historical events and people, and may be written for entertainment or educational purposes.

House & Home. House & home books focus on topics like interior design, decorating, entertaining, and DIY projects.

Humor. Humor books are contain humorous elements but do not have any fictional elements.

Juvenile Nonfiction. These are nonfiction books written for children between six and twelve years old.

Language Arts & Disciplines. These books focus on teaching language arts and disciplines. They may be used for elementary school students in grades K-5.

Law. Law books include legal treatises, casebooks, and collections of statutes.

Literary Criticism. Literary criticism books discuss literary works, primarily key works of fiction or memoir. They may include biographies of authors, critical essays on specific works, or studies of the history of literature.

Mathematics. Mathematics books either teach mathematical concepts and methods or explore the history of mathematics.

Medical. Medical books include textbooks, reference books, guides, encyclopedias, and handbooks that focus on fields of medicine, including general practice, internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, and more.

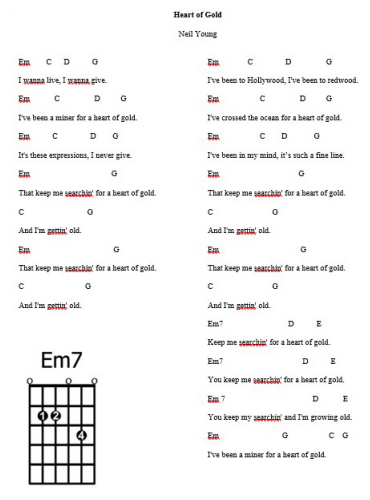

Music. Music books are books that focus on the history, culture, and development of music in various countries around the world. They often include biographies, interviews, reviews, essays, and other related material. However, they may also include sheet music or instruction on playing a specific instrument.

Nature. Nature books focus on the natural world or environment, including natural history, ecology, or natural experiences like hiking, bird watching, or conservation.

Performing Arts. Books about the performing arts in general, including specific types of performance art like dance, music, and theater.

Pets. Pet books include any book that deals with animals in some way, including dog training, cat care, animal behavior, pet nutrition, bird care, and more.

Philosophy. Philosophy books deal with philosophical issues, and may be written for a general audience or specifically for scholars.

Photography. Photography books use photographs as an essential part of their content. They may be about any subject.

Political Science. Political science books deal with politics in some way. They can be about current events, historical figures, or theoretical concepts.

Psychology. Psychology books are about the scientific study of mental processes, emotion, and behavior.

Reference. Reference books are about any subject, topic, or field and contain useful information about that subject, topic or field.

Religion. These books deal with religion in some way, including religious history, theology, philosophy, and spirituality.

Science. Science books focus on topics within scientific fields, including geology, biology, physics, and more.

Self-Help. Self-help books are written for people who want to improve their lives in some way. They may be about health, relationships, finances, career, parenting, spirituality, or any number of topics that can help readers achieve personal goals.

Social Science. Focus on social science topics.

Sports & Recreation. Sports & Recreation books focus on sports either from a reporting, historical, or instructional perspective.

Study Aids. Study aids are books that provide information about a particular subject area for students who want to learn more about that topic. These books can be used in conjunction with classroom instruction or on their own.

Technology & Engineering. Technology & engineering nonfiction books describe how technology has changed our lives and how we can use that knowledge to improve ourselves and society.

Transportation. Focus on transportation topics including those about vehicles, routes, or techniques.

Travel. Travel books are those that focus on travel experiences, whether from a guide perspective or from the author's personal experiences.

True Crime. True Crime books focus on true stories about crimes. These books may be about famous cases, unsolved crimes, or specific criminals.

Young Adult Nonfiction. Young adult nonfiction books are written for children and teenagers.

3. Drama Genres

These include genres for theater, film, television serials, or audio plays.

As a writer, I find some of these genres particularly eye-roll worthy. And yet, this is the way most films, television shows, and even theater productions are classified.

Action. Action genre dramas involve fast-paced, high-energy sequences in which characters fight against each other. They often have large-scale battles, chase scenes, or other high-intensity, high-conflict scenes.

Horror. Horror dramas focus on the psychological terror experienced by their characters. They often feature supernatural elements, such as ghosts, vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, monsters, and aliens.

Adventure. Adventure films are movies that have an adventurous theme. They may be set in exotic locations, feature action sequences, and/or contain elements of fantasy.

Musicals (Dance). Musicals are dramas that use music in their plot and/or soundtrack. They may be comedies, dramas, or any combination.

Comedy (& Black Comedy). Comedy dramas feature humor in their plots, characters, dialogue, or situations. It sometimes refers to historical dramas (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek drama, etc) that contain a happy ending, often with a wedding.

Science Fiction. Science fiction dramas are usually set in an imaginary future world, often involving advanced technology. They may be based on scientific facts but do not have to be.

Crime & Gangster. Crime & Gangster dramas deal with criminals, detectives, or organized crime groups. They often feature action sequences, violence, and mystery elements.

War (Anti-War). War (or anti-war) dramas focus on contemporary or historical wars. They may also contain action, adventure, mystery, or romance elements.

Drama. Dramas focus on human emotions in conflict situations. They often have complex plots and characters, and deal with serious themes. This may also refer to historical stories (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a sad or tragic ending, often with one or more deaths.

Westerns. Westerns are a genre of American film that originated in the early 20th century and take place in the west during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Characters include cowboys, outlaws, native Americans, and settlers.

Epics/Historical/Period. These are dramas based on historical events or periods but do not necessarily involve any real people.

Biographical (“Biopics”). Biopics films are movies that focus on real people in history.

Melodramas, Women's or “Weeper” Films, Tearjerkers. A type of narrative drama that focuses on emotional issues, usually involving love, loss, tragedy, and redemption.

“Chick” Flicks. Chick flicks usually feature romantic relationships and tend to be lighthearted and comedic in nature.

Road Stories. Dramas involving a journey of some kind, usually taking place in contemporary setting, and involving relationships between one or more people, not necessarily romantic.

Courtroom Dramas. Courtroom dramas depict legal cases set in courtrooms. They usually have a dramatic plot line with an interesting twist at the end.

Romance. Romance dramas feature love stories between two people. Romance dramas tend to be more serious, even tragic, in nature, while romantic comedies tend to be more lighthearted.

Detective & Mystery. These dramas feature amateur or professional investigators solving crimes and catching criminals.

Sports. Sports dramas focus on athletic competition in its many forms and usually involve some kind of climactic tournament or championship.

Disaster. Disaster dramas are adventure or action dramas that include natural disasters, usually involving earthquakes, floods, volcanoes, hurricanes, tornadoes, or other disasters.

Superhero. Superhero dramas are action/adventure dramas that feature characters with supernatural powers. They usually have an origin story, the rise of a villain, and a climactic battle at the end.

Fantasy. Fantasy dramas films are typically adventure dramas that feature fantastical elements in their plot or setting, whether magic, folklore, supernatural creatures, or other fantasy elements.

Supernatural. Supernatural dramas feature paranormal phenomena in their plots, including ghosts, mythical creatures, and mysterious or extraordinary elements. This genre may overlap with horror, fantasy, thriller, action and other genres.

Film Noir. Film noir refers to a style of American crime drama that emerged in the 1940s. These dramas often featured cynical characters who struggled, often fruitlessly, against corruption and injustice.

Thriller/Suspense. Thriller/suspense dramas have elements of suspense and mystery in their plot. They usually feature a character protagonist who must overcome obstacles while trying to solve a crime or prevent a catastrophe.

Guy Stories. Guy dramas feature men in various situations, usually humorous or comedic in nature.

Zombie . Zombie dramas are usually action/adventure dramas that involve zombies.

Animated Stories . Dramas that are depicted with drawings, photographs, stop-motion, CGI, or other animation techniques.

Documentary . Documentaries are non-fiction performances that attempt to describe actual events, topics, or people.

“Foreign.” Any drama not in the language of or involving characters/topics in your country of origin. They can also have any of the other genres listed here.

Childrens – Kids – Family-Oriented . Dramas with children of various ages as the intended audience.

Sexual – Erotic . These dramas feature explicit sexual acts but also have some kind of plot or narrative (i.e. not pornography).

Classic . Classic dramas refer to dramas performed before 1950.

Silent . Silent dramas were an early form of film that used no recorded sound.

Cult . Cult dramas are usually small-scale, independent productions with an offbeat plot, unusual characters, and/or unconventional style that have nevertheless gained popularity among a specific audience.

4. Poetry Genres

This list is from Harvard's Glossary of Poetic Genres who also has definitions for each genre.

Dramatic monologue

Epithalamion

Light verse

Occasional verse

Verse epistle

What Are the Components of Genre In Literature? The 7 Elements of Genre

Now that we've looked, somewhat exhaustively, at examples of literary genres, let's consider how these genres are created.

What are the elements of literary genre? How are they formed?

Here are seven components that make up genre.

- Form . Length is the main component of form (e.g. a novel is 200+ pages , films are at least an hour, serialized episodes are about 20 minutes, etc), but may also be determined by how many acts or plot lines they have. You might be asking, what about short stories? Short stories are a genre defined by their length but not their content.

- Intended Audience . Is the story meant for adults, children, teenagers, etc?

- Conventions and Tropes . Conventions and tropes describe patterns or predictable events that have developed within genres. For example, a sports story may have a big tournament at the climax, or a fantasy story may have a mentor character who instructs the protagonist on the use of their abilities.

- Characters and Archetypes. Genre will often have characters who serve similar functions, like the best friend sidekick, the evil villain , the anti-hero , and other character archetypes .

- Common Settings and Time Periods . Genre may be defined by the setting or time period. For example, stories set in the future tend to be labelled science fiction, stories involving the past tend to be labelled historical or period, etc.

- Common Story Arcs . While every story type may use each of the six main story arcs , genre tends to be defined by specific story arcs. For example, comedy almost always has a story arc that ends positively, same with kids or family genres. However, dramas often (and when referring to historical drama, always) have stories that end tragically.

- Common Elements (such as supernatural elements, technology, mythical creatures, monsters, etc) . Some genres center themselves on specific elements, like supernatural creatures, magic, monsters, gore, and so on. Genre can be determined by these common elements.

As you consider these elements, keep in mind that genre all comes back to taste, to what readers want to consume and how to match the unlimited variations of story with the infinite variety of tastes.

Read What You Want, Write What You Want

In the end, both readers and writers should use genre for what it is, a tool, not as something that defines you.

Writers can embrace genre, can use genre, without being controlled by it.

Readers can use genre to find stories or books they enjoy while also exploring works outside of that genre.

Genre can be incredibly fun! But only if you hold it in tension with your own work of telling (or finding) a great story.

What are your favorite genres to read in? to write in? Let us know in the comments!

Now that we understand everything there is to know about literary genres, let's put our knowledge to use with an exercise. I have two variations for you today, one for readers and one for writers.

Readers : Think of one of your favorite stories. What is the literary genre of that story? Does it have multiple? What expectations do you have about stories within that genre? Finally, how does the author of your favorite story use those expectations, and how do they subvert them?

Writers : Choose a literary genre from the list above and spend fifteen minutes writing a story using the elements of genre: form, audience, conventions and tropes, characters and archetypes, setting and time periods, story arcs, and common elements.

When you’re finished, share your work in the Pro Practice Workshop here . Not a member yet? Join us here !

Join 100 Day Book

Enrollment closes May 14 at midnight!

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

So how big does an other-genre element need to get before you call your book “cross-genre”? Right now, I’m writing a superhero team saga (which is already a challenge for platforms that don’t recognize “superhero” as a genre, since my team’s powers lie in that fuzzy land where the distinction between science and magic gets more than a little blurry), so it obviously has action/adventure in it, but it’s also sprouting thriller and mystery elements. I’m wondering if they’re big enough to plug the series to those genres.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Secondary Menu

Genres of writing.

We use the term genres to describe categories of written texts that have recognizable patterns, syntax, techniques, and/or conventions. This list represents genres students can expect to encounter during their time at Duke. The list is not intended to be inclusive of all genres but rather representative of the most common ones. Click on each genre for detailed information (definition, questions to ask, actions to take, and helpful links).

- Abstract (UNC)

- Academic Email

- Annotated Bibliography

- Argument Essay

- Autobiographical Reflection

- Blogs (Introduction)

- Blogs (Academic)

- Book Review

- Business Letter (Purdue)

- Close Reading

- Compare/Contrast: see Relating Multiple Texts

- Concert Review

- Cover Letter

- Creative Non-fiction

- Creative Writing

- Curriculum Vitae

- Essay Exams (Purdue)

- Ethnography

- Film Review

- Grant Proposals (UNC)

- Group Essays

- Letters to the Editor

- Literature Review

- Mission Statement

- Oral Presentations

- Performance Review

- Personal Statement: Humanities

- Personal Statement: Professional School/Scholarship

- Poetry Explication

- Policy Memo

- Presentation: Convert your Paper into a Talk

- Program II Duke Application Tips

- Relating Multiple Texts

- Research and Grant Proposals

- Response/Reaction Paper

- Resume, Non-academic ( useful list of action verbs from Boston College)

- Scientific Article Review

- Scientific Writing for Scientists (quick tips)

- Scientific Writing for Scientists: Improving Clarity

- Scientific Writing for a Popular Audience

- Scientific Jargon

- Timed Essays/Essay Exams

- Visual Analysis

- Job Opportunities

- Location & Directions

- Writing 101: Academic Writing

- "W" Codes

- TWP Writing Studio

- Duke Reader Project

- Writing Resources

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Deliberations 2020: Meet the Authors

- Deliberations 2021: Meet the Authors

- TWP & Duke Kunshan University

- Writing in the Disciplines

- Upcoming WID Pedagogy Workshops

- WID Certificate

- Course Goals and Practices

- Faculty Guide

- First-Year Writing & The Library

- Guidelines for Teaching

- Applying for "W" Code

- Faculty Write Program

- Teaching Excellence Awards

- Writing 101: Course Goals and Practices

- Choosing a Writing 101 Course

- Writing 101 and Civic Engagement

- Applying and Transferring Writing 101 Knowledge

- Approved Electives

- Building on Writing 101

- Crafting Effective Writing Assignments

- Responding to Student Writing

- Thinking & Praxis Workshops

- About the Writing Studio

- What to Expect

- Schedule an Appointment

- View or Cancel an Appointment

- Graduate Writing Lab

- Undergraduate Writing Accountability Group

- Consultant Bios

- Resources for Faculty

- Community Outreach

- Frequently Asked Questions

- About the Faculty Write Program

- Writing Groups

- How I Write

- Course List

- Instructors

- Think-Aloud Responses Examples

- TWP Courses

- Approved Non-TWP Courses

- Graduate Student Instructors

- Faculty Selected Books

- Featured Publications

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Your In-Depth Guide

.png)

Essays, as a literary form, have deep historical roots. Their origins can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, where philosophers and scholars penned texts that shared knowledge, insights, and reflections. Over the centuries, essays have evolved into a versatile medium for expressing ideas, emotions, and information. This evolution has led to the development of various essay genres, each tailored to serve a distinct purpose.

Imagine the ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle or the Roman statesman and philosopher Seneca using essays to convey their profound thoughts and philosophical musings. Fast forward to modern times, and we see how essays have adapted to our changing world, becoming a cornerstone of communication and education.

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Short Description

In this article, we'll unravel various essay genres, from narrative to expository, argumentative to descriptive, and many more. We'll break them down by explaining what they are and what makes them unique. You'll find examples that show how these essays work in the real world, along with tips to help you become a pro at writing them. Whether you're a student looking to ace your assignments or a writer seeking to sharpen your skills, we've got you covered with all you need to know about different kinds of essays.

What Type of Essays Are There: The Diversity of Essay Genres

Before we dive into the specifics of different essay genres, let's take a moment to appreciate the rich tapestry of essay writing. Essays come in various forms, each with its own unique characteristics and purposes. From narratives that tell compelling stories to expository essays that explain complex topics and persuasive essays that aim to change minds, custom essay writers of our persuasive essay writing service will explore this diverse landscape to help you understand which genre suits your needs and how to master it.

- Essays Are Like Handy Tools : Think of essays as tools that can help you communicate in many different ways. Just like a Swiss Army knife has different functions, essays can be used for various purposes in writing.

- Choose Your Words Wisely : Different situations need different ways of talking or writing. Essays let you choose the best way to say what you want, whether you're telling a personal story, explaining something, or trying to convince someone of your point of view.

- Boost Your Writing Skills : Learning about different essay types can make you a better writer. It can help you write more effectively, whether you're working on a school assignment, a blog post, or an important letter.

- Essays Have Made History : Throughout history, essays have been a big deal. They've shaped our culture and society. From old classics to modern essays, they've had a big impact.

- Stand Out in the Online World : In today's digital world, where there's a lot of information and not much time, knowing how to write different types of essays can help you get noticed. Being good at different styles of writing is a useful skill in a world full of information.

The Descriptive Essay

In a descriptive essay, the objective is to immerse the reader in the experience of what you're describing. For instance, when contemplating how to write an article review , utilizing descriptive writing allows you to vividly depict the subject matter, creating a rich and immersive portrayal through words.

A. Definition and Characteristics

- What is it? A descriptive essay is like a word painting. It uses lots of details and vivid words to create a picture in the reader's mind.

- Characteristics:

- Lots of sensory details: Descriptive essays make you feel like you're right there by using words that describe what you can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch.

- Vivid language and imagery: They use colorful words and phrases to make the reader really imagine what's being described.

B. Examples and Use Cases

- When do we use it? Imagine describing your favorite place, like a cozy cabin in the woods, or a memorable experience, like your first day at school. These are common subjects for descriptive essays.

- Describing a beautiful sunset over the ocean.

- Painting a picture of your childhood home, room by room.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Descriptive Essay

- Show, Don't Tell: Instead of just saying something is 'nice,' show why it's nice by describing the details that make it special.

- Organize Details: Arrange your descriptions in an order that makes sense. Start with the big picture and then focus on the smaller details.

Engage the Senses: Make sure your writing appeals to all the senses. Describe how things look, sound, smell, taste, and feel to create a complete picture.

Ready to Craft a One-of-a-Kind Essay?

Order now for a tailored essay - Our expert wordsmiths are armed with creativity, precision, and a sprinkle of genius!

The Expository Essay

In an expository essay, your job is to be a great teacher. You're presenting information in a way that's easy to understand and follow so the reader can learn something new or gain a deeper insight into a subject.

- What is it? An expository essay is like a friendly explainer. It provides clear and factual information about a topic, idea, or concept.

- It's all about facts: Expository essays rely on solid evidence, data, and information to explain things.

- Clear and organized: They follow a logical structure with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

- When do we use it? Think of when you need to explain something, like how photosynthesis works, how to bake a cake, or the causes of climate change. These topics are perfect for expository essays.

- Explaining the steps to solve a math problem.

- Describing the history and significance of a famous landmark.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Expository Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong and clear thesis statement that tells the reader what your essay is all about.

- Organized Structure: Divide your essay into clear sections or paragraphs that each cover a specific aspect of the topic.

- Supporting Evidence and Citations: Use reliable sources and provide evidence like facts, statistics, or examples to back up your explanations.

The Argumentative Essay

In this example of essay type, your goal is to persuade the reader to agree with your point of view or take action on a specific issue. It's like being a lawyer presenting your case in court, but instead of a judge and jury, you have your readers.

- What is it? An argumentative essay is like a debate on paper. It's all about taking a clear stance on a controversial topic and providing strong reasons and evidence to support your point of view.

- A strong thesis statement: Argumentative essays start with a clear and assertive thesis statement that tells the reader your position.

- Counter Arguments: They also consider opposing viewpoints and then refute them with evidence.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to convince someone that your favorite book is the best ever or that recycling should be mandatory. These are situations where you'd use an argumentative essay.

- Arguing for or against a particular law or policy.

- Debating the pros and cons of a controversial technology like artificial intelligence.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Argumentative Essay

- Strong Thesis: Make sure your thesis is clear, specific, and debatable.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence and use logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and explain why your perspective is more valid.

The Narrative Essay

In a narrative essay, you assume the role of the storyteller, guiding your readers through your personal experiences. This style is particularly apt when contemplating how to write a college admission essay . It offers you the opportunity to share a piece of your life story and forge a connection with your audience through the captivating art of storytelling.

- What is it? A narrative essay is like sharing a personal story. It's all about recounting an experience, event, or moment in your life in a way that engages the reader.

- It's personal: Narrative essays often use 'I' because they're about your own experiences.

- Storytelling: They have a beginning, middle, and end, just like a good story.

- When do we use it? Think of moments in your life that you want to share, like a funny incident, a life-changing event, or a memorable trip. These are perfect for narrative essays.

- Sharing a personal childhood memory that taught you a valuable lesson.

- Describing an adventure-filled vacation that had a big impact on your life.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Narrative Essay

- Engaging Start: Begin with a captivating hook to draw the reader into your story.

- Show, Don't Tell: Use descriptive language to help the reader visualize the events and feel the emotions.

- Reflect and Conclude: Wrap up your narrative by reflecting on the experience and why it was meaningful or significant.

The Contrast Essay

In this type of essays, your goal is to help the reader understand how two or more things are distinct from each other. It's a way to bring out the unique qualities of each subject and make comparisons that highlight their differences.

- What is it? A contrast essay is like a spotlight on differences. It's all about showing how two or more things are different from each other.

- Comparison: Contrast essays focus on comparing two or more subjects and highlighting their dissimilarities.

- Clear Structure: They often use a structured format, discussing one point of difference at a time.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to explain how two cars you're considering for purchase are different, or you're comparing two historical figures for a school project. These are situations where you'd use a contrast essay.

- Contrasting the pros and cons of two different smartphone models.

- Comparing the lifestyles and philosophies of two famous authors.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Contrast Essay

- Choose Clear Criteria: Decide on the specific criteria or aspects you'll use to compare the subjects.

- Organized Structure: Use a clear and organized structure, such as a point-by-point comparison or a subject-by-subject approach.

- Highlight Key Differences: Ensure you emphasize the most significant differences between the subjects.

The Definition Essay

In a definition essay, you take on the role of a language detective, seeking to unravel the intricate layers of meaning behind a term. It's a chance to explore the nuances and variations in how people understand and use a specific word or concept.

- What is it? A definition essay is like a word detective. It's all about explaining the meaning of a specific term or concept, often one that's abstract or open to interpretation.

- Clarity: Definition essays aim to provide a clear, precise, and comprehensive definition of the chosen term.

- Exploration: They explore the various facets, interpretations, and nuances of the term.

- When do we use it? Think of terms or concepts that people might misunderstand or have different opinions about, like 'freedom,' 'happiness,' or 'justice.' These are great candidates for definition essays.

- Defining the concept of 'success' and what it means to different people.

- Exploring the various definitions and interpretations of 'love' in different cultures and contexts.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Definition Essay

- Choose a Complex Term: Select a term that has multiple meanings or interpretations.

- Research and Explore: Investigate the term thoroughly, including its history, etymology, and various definitions.

- Provide Examples: Use real-life examples, anecdotes, or scenarios to illustrate your definition.

The Persuasive Essay

In a persuasive essay, your goal is to be a persuasive speaker through your writing. You're trying to win over your readers and get them to agree with your perspective or take action on a particular issue. It's all about presenting a compelling argument that makes people see things from your point of view.

- What is it? A persuasive essay is like a friendly argument with facts. It's all about convincing the reader to agree with your point of view on a particular topic or issue.

- Strong Opinion: Persuasive essays start with a clear and strong opinion or position.

- Evidence-Based: They rely on solid evidence, logic, and reasoning to support their argument.

- When do we use it? Think of situations where you want to persuade someone to see things your way, like convincing your parents to extend your curfew or advocating for a cause you believe in. These are scenarios where you'd use a persuasive essay.

- Arguing for stricter environmental regulations to combat climate change.

- Convincing readers to support a specific charity or volunteer for a cause.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong thesis statement that clearly states your opinion.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence, statistics, and logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing views to strengthen your argument.

How to Identify the Genre of an Essay

Identifying the genre of an essay is like deciphering the code that unlocks its purpose and style. This skill is crucial for both readers and writers because it helps set expectations and allows for a deeper understanding of the text. Here are some insightful tips on how to identify the genre of an essay from our thesis writing help :

1. Analyze the Introduction:

- The introductory paragraph often holds valuable clues. Look for keywords, phrases, or hints that reveal the writer's intention. For example, a narrative essay might start with a personal anecdote, while a synthesis essay may introduce a topic with a concise explanation.

2. Examine the Tone and Language

- The tone and language used in the essay provide significant clues. A persuasive essay may employ passionate and convincing language, whereas an informative essay tends to maintain a neutral and factual tone.

3. Check the Structure

- Different genres of essays follow specific structures. Narrative essays typically have a chronological structure, while argumentative essays present a clear thesis and structured arguments. Understanding the essay's organizational pattern can help pinpoint its genre.

4. Consider the Content

- The subject matter and content of the essay can also indicate its genre. Essays discussing personal experiences or emotions often lean towards the narrative or descriptive genre, while those presenting facts and analysis typically fall into the expository or argumentative category.

5. Identify the Author's Intent

- Sometimes, the author's intent becomes apparent when considering why they wrote the essay. Are they trying to entertain, inform, persuade, or reflect on a personal experience? Understanding the author's purpose can be a powerful tool for genre identification.

6. Recognize Genre Blending

- Keep in mind that some essays may blend multiple genres. For instance, a personal essay might incorporate elements of both narrative and descriptive writing. In such cases, it's essential to identify the dominant genre and any secondary influences.

7. Seek Contextual Clues

- Context can provide valuable insights. Consider where you encountered the essay — in a literature class, a news outlet, or a personal blog. The context can often hint at the intended genre.

8. Ask Questions

- Don't hesitate to ask questions as you read. What is the author trying to achieve? Is the focus on storytelling, providing information, arguing a point, or something else? Questions like these can guide you toward identifying the genre.

Final Thoughts

In the tapestry of writing, we've unraveled the threads of diverse essay styles, from the vivid descriptions of the descriptive essay to the informative clarity of expository pieces. Each genre brings its unique charm to the literary world. Embrace this versatility in your own writing journey, adapting your style to engage, inform, and persuade. In the realm of essays, your creative potential has boundless opportunities. Should you ever require help with the request, ' write papers for me ,' you can be confident that our professional writers will deliver an exceptional paper tailored to your needs!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.6 Common Sub-Genres of Academic Writing or What You’ll Be Writing

Nancy Ami; Natalie Boldt; Sara Humphreys; Jemma Llewellyn; and Erin Kelly

As promised and at long last, here is an overview of the major conventions of common academic subgenres. You will probably notice similarities and crossovers between the conventions of these sub-genres. Good! If you do, this means you are learning how to navigate genres. As an undergraduate student, much of the writing you do will be academic writing, but it won’t be exactly like the published academic writing (including journal articles, books, or even textbooks) associated with your field of study. It’s helpful to think of academic writing assignments for courses as pieces of, steps toward, or even simplified models of published academic writing. Expect to see more commonalities between your own academic writing and what experts in the field publish as you move into more advanced work in a particular discipline.

But before we get to the sub-genres of academic writing, there are conventional components of these sub-genres that you should get to know: summary writing, paraphrasing, and quoting. If you can manage to follow these conventions, you’ll be well on your way to being an effective academic writer.

Convention One: Summary Writing

Almost every sub-genre of academic writing includes summary writing. The process of summarizing a longer text involves moving “from big to small,” as a University of Victoria Centre for Academic Communication tutor beautifully puts it. Indeed, a summary is like a movie trailer or sports reel version of a longer work. When crafting summaries, writers distill and explain main ideas themselves, using their own phrasing and sentence structure but always citing the source for these ideas.

When Will I Summarize?

In most cases, there are two key goals for a summary:

- Inform readers who haven’t previously read the text you are summarizing its main ideas.

- Offer an accurate and fair overview of those main ideas.

Even so, you will see some variation in summary assignments:

Sometimes, you will be asked to summarize the main ideas of a complex article in a long paragraph (or even the main ideas of a book in a few pages).

Sometimes, you will be asked to write a very brief summary of a long text to help readers decide if it’s worth their time. (This is a common type of summary in the context of an annotated bibliography.)

Sometimes, you summarize to set up your own response to an argument by another writer. In this case, you probably want to make your summary as brief as possible without sacrificing accuracy to allow space for your own ideas.

And sometimes you need to summarize your own longer piece of work – that’s how abstracts for journal articles get written.

So, once you have a draft summary, make sure you fully understand what type of summary your finished product needs to be – and revise accordingly.

What Should I Avoid When Summarizing?

Because the job of a summary is to put another writer’s ideas into your own words – in the process, translating those ideas to meet the needs of your readers – it’s not appropriate or effective to replicate the original language or even sentence structure and overall organizational plan of the original.

When a writer takes sentences from the original document and substitutes synonyms for some words, changes the order of others, and maybe reworks a few phrases, this person isn’t creating a successful summary. Instead, this way of replicating features of the original text too closely is called patch-writing. Even when the source is cited, patch-writing is usually considered plagiarism because the writer is implying they reworked the original text more than they did. A thorough discussion of patchwriting is featured in this Merriam-Webster post . [1]

The best way to avoid patch-writing is to follow the how-to instructions (below) while keeping in mind the purpose of your summary. If your aim is to give your reader an understanding of something you read, then you can see why patch-writing won’t get the job done. To avoid patch-writing, perhaps follow the advice given here.

When you summarize, you cannot rely on the language the author has used to develop his or her points, and you must find a way to give an overview of these points without your own sentences becoming too general. You must also make decisions about which concepts to leave in and which to omit, taking into consideration your purposes in summarizing and also your view of what is important in this text. Here are some methods for summarizing: First, prior to skimming, use some of the previewing techniques.

Include the title and identify the author in your first sentence.

The first sentence or two of your summary should contain the author’s thesis , or central concept, stated in your own words. This is the idea that runs through the entire text–the one you’d mention if someone asked you: “What is this piece/article about?” Unlike student essays, the main idea in a primary document or an academic article may not be stated in one location at the beginning. Instead, it may be gradually developed throughout the piece or it may become fully apparent only at the end.

When summarizing a longer article, try to see how the various stages in the explanation or argument are built up in groups of related paragraphs. Divide the article into sections if it isn’t done in the published form. Then, write a sentence or two to cover the key ideas in each section.

Omit ideas that are not really central to the text. Don’t feel that you must reproduce the author’s exact progression of thought. (On the other hand, be careful not to misrepresent ideas by omitting important aspects of the author’s discussion).

In general, omit minor details and specific examples . (In some texts, an extended example may be a key part of the argument, so you would want to mention it).

Avoid writing opinions or personal responses in your summaries (save these for active reading responses or tutorial discussions).

Be careful not to plagiarize the author’s words. If you do use even a few of the author’s words, they must appear in quotation marks . To avoid plagiarism, try writing the first draft of your summary without looking back at the original text. [2]

We suggest paying close attention to number seven in the advice given above. This is your best bet not to patch-write, which can be construed as plagiarism. Nobody wants that to happen!

Convention Number Two: Paraphrasing

Interestingly, the word “paraphrase” is both a verb and a noun:

When we paraphrase (verb), we explain a concept ourselves. We use our words, our way, to restate an idea. Paraphrasing also occurs when we write a summary. We use our words, our way, moving from big to small, to distill the main points from a longer text to a short text, citing the source.

When we write a paraphrase (noun), we use our words , our way, moving from small to small, to restate an idea from an original sentence/sentences to our own sentence/sentences, citing the source.

To write a paraphrase, focus on the original short excerpt and take note of key ideas. Look away from the original text. Notice the similarities with summary writing? There, too, you need to use your notes to rewrite the original, changing the sentence structure, reordering ideas, and using your words to explain the idea. As with summary writing, integrate the information into your paragraph by introducing the idea, citing the source , and indicating how the paraphrased information fits with the key idea in your paragraph.

Convention Number Three: Quoting

We suggest using quotations sparingly, selecting to quote only when the original writer’s words are so unique and memorable that they can’t be paraphrased. Placing a relevant (yet brief) quotation in your introduction can pique your reader’s interest in the topic you are writing about. You also may want to include an authority’s words as evidence for your claim. Another reason to quote is to respond to those who may disagree with your ideas (naysayers) by quoting them first. Quotes can be powerful additions to your writing.

Here are a few grammatical considerations when quoting (that may save your grade):

- Copy the original words accurately, enclosing them in double quotation marks.

- If you need to omit words to smoothly integrate the quote into a sentence, use ellipses.

- If you wish to add words to integrate the quote seamlessly into a sentence, use square brackets.

- Always, always introduce the quotation and explain its significance: Why are you including this quote?

When Do I Use Direct Quotes and When Do I Paraphrase?

We strongly suggest limiting the number of quotes you use because you want to present your ideas in your own words. If you include too many quotations, your voice can be drowned out. In many disciplines, writers use quotations sparingly (like salt) to support their claims. A little bit of salt makes a dish more appealing, but too much salt makes it inedible. The same can be true with quotations. In fact, in some disciplines, writers almost never quote from original documents.

When writing from sources, you will routinely summarize, paraphrase, and quote, citing your sources every time you draw on others’ ideas. And where will you be summarizing, paraphrasing and quoting? In lots of different academic sub-genres: reports, blogs, forums, book reviews and (drum roll, please), essays.

- “Words We’re Watching: ‘Patchwriting’. Paraphrasing in a Cut-and-Paste World,” Merriam-Webster , accessed June 29, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/words-were-watching-patchwriting . ↵

- Leora Freedman, “Summarizing,” Writing Advice , University of Toronto, 2012, https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/summarize/ . ↵

Why Write? A Guide for Students in Canada Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Ami; Natalie Boldt; Sara Humphreys; Jemma Llewellyn; and Erin Kelly is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

18.1 Mixing Genres and Modes

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Address a range of audiences using a variety of technologies.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of modalities, including textual and digital compositions.

- Match the capacities of different print and electronic environments to varying rhetorical situations.

The writing genre for this chapter incorporates a variety of modalities. A genre is a type of composition that encompasses defined features, follows a style or format, and reflects your purpose as a writer. For example, given the composition types romantic comedy , poetry , or documentary , you probably can think easily of features of each of these composition types. When considering the multimodal genres, you will discover that genres create conventions (standard ways of doing things) for categorizing media according to the expectations of the audience and the way the media will be consumed. Consider film media, for example; it encompasses genres including drama, documentaries, and animated shorts, to name a few. Each genre has its own conventions, or features. When you write or analyze multimodal texts, it is important to account for genre conventions.

A note on text: typically, when referring to text, people mean written words. But in multimodal genres, the term text can refer to a piece of communication as a whole, incorporating written words, images, sounds, and even movement. The following images are examples of multimodal texts.

Multimodal genres are uniquely positioned to address audiences through a variety of modes , or types of communication. These can be identified in the following categories:

Linguistic text : The most common mode for writing, the linguistic mode includes written or spoken text.

Visuals : The visual mode includes anything the reader can see, including images, colors, lighting, typefaces, lines, shapes, and backgrounds.

Audio : The audio mode includes all types of sound, such as narration, sound effects, music, silence, and ambient noise.

Spatial : Especially important in digital media, the spatial mode includes spacing, image and text size and position, white space, visual organization, and alignment.

Gestural : The gestural mode includes communication through all kinds of body language, including movement and facial expressions.

Multimodal composition provides an opportunity for you to develop and practice skills that will translate to future coursework and career opportunities. Creating a multimodal text requires you to demonstrate aptitude in various modes and reflects the requirements for communication skills beyond the academic world. In other words, although multimodal creations may seem to be little more than pictures and captions at times, they must be carefully constructed to be effective. Even the simplest compositions are meticulously planned and executed. Multimodal compositions may include written text, such as blog post text, slideshow text, and website content; image-based content, such as infographics and photo essays; or audiovisual content, including podcasts, public service announcements, and videos.

Multimodal composition is especially important in a 21st-century world where communication must represent and transfer across cultural contexts. Because using multiple modes helps a writer make meaning in different channels (media that communicate a message), the availability of different modes is especially important to help you make yourself understood as an author. In academic settings, multimodal content creation increases engagement, improves equity, and helps prepare you to be a global citizen. The same is true for your readers. Multimodal composition is important in addressing and supporting cultural and linguistic diversity. Modes are shaped by social, cultural, and historic factors, all of which influence their use and impact in communication. And it isn’t just readers who benefit from multimodal composition. Combining a variety of modes allows you as a composer to connect to your own lived experiences—the representation of experiences and choices that you have faced in your own life—and helps you develop a unique voice, thus leveraging your knowledge and experiences.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/18-1-mixing-genres-and-modes

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Writing Program at New College

Genre: Genres are the familiar forms in which writing is organized. A letter is a genre, as is a poem, a personal essay, a proposal, a novel or short story, a memorandum, an editorial, etc. Emails, texts, and tweets are among the most common electronic genres. Any form that is recognizable as a distinct and common way of organizing writing can be considered a genre. Genres have more or less predictable conventions, that is, rules or patterns of structure and style.

Often, in the case of an academic assignment or a professional context, writers do not get to choose the genre they will work in. The overall rhetorical situation will dictate that choice. When there are options to choose from, writers need to carefully consider their choice of genre. Particular genres are suited for particular occasions. You wouldn’t write a poem, most likely, when announcing a new policy or procedure in your workplace..

Remember also that the rules or "conventions" of genres structure the ways readers interact with text. Readers typically know what to expect from a news story or an academic article. Thinking back to our initial definitions of rhetoric, remember that working carefully with genre conventions is an important way to connect with audiences.

[READ MORE] What Are You Making? Genre, Format, Structure, etc.

Writing Program

Select Section

- Departments

- For Students

- For Faculty

- Writing Center

Common Genres for Graduate Students & Faculty

- Online Tutoring

- For Instructors

Many people often see a genre as the sum of textual features; for instance, a lab report includes an introduction, a description of methods, one or more sections on results and discussion, and a conclusion. Scholars in genre theory, however, suggest that there is more to genre. A genre, which includes such textual features, is also part of a genre set, and the genre set is called up by a disciplinary community’s worldview. What do the genre sets suggest about the disciplinary community’s values and beliefs? What is considered significant enough to research, and why? What constitutes valid data and sound logic, and consequently, which research methods are preferred? The answers to these questions vary, of course, depending on the discipline, but the commonality of the following genres also suggests some common values across the university.

In what follows, you’ll find the most common genres that make up most research disciplines’ genre sets. Even as these genres are usually written by graduate students and faculty, I encourage you to also consider how undergraduates are invited into the discipline when asked to write brief or otherwise altered versions of these genres.

Abstract: An abstract is a brief summary of one’s research and, if done well, will tempt readers to read more. The abstract may address the following: What is the research topic, and what does the discipline already know about this topic? What is the writer’s research question, and how will this build on existing knowledge? And how will the writer go about answering that research question? An abstract often needs to abide by strict length requirements (usually one paragraph).

Proposal or Prospectus: A proposal makes a case for one’s research project and is basically an elaborated abstract. The writer will typically (a) introduce her research question, (b) provide a rationale for why the project is needed (often based on past research), (c) describe the methods used to answer the question, (d) discuss practical matters like a timeline or budget (especially if applying for funds), and (e) conclude with the significance of the project. Each proposal, like all writing, should be tailored to its purpose and audience. The length of proposals ranges from a few pages to over thirty pages. Researchers may write proposals to justify dissertation research, to present in a conference, to earn fellowship or grant funds to pursue the research, to garner honors from a professional association, or to get a book published. A major challenge is to forecast the significance of the research before one has fully done the research.

Personal Statement: For researchers, a personal statement narrates how one’s academic inquiry has led up to her current research; the writer needs to present herself as a scholar who contributes to the discipline. Details can help the writer set herself apart from others; such details can include the questions driving the research, the projects and publications that bear out these questions, the awards and other distinctions granted to her based on such research, and so on. When revising personal statements, writers will often work hard to make seemingly separate details fit into a neat narrative and also replace vague assertions with descriptive detail.

Book Review: A book review in an academic journal will discuss the book’s relevance to a particular area of research; this is different from book reviews published in popular media. The writer will typically (a) discuss how the book responds to a pressing question in the field (possibly aligning the book with other books addressing that question), (b) give a synopsis of the book, (c) elaborate on interesting sections whether for the sake of critique or praise, and (d) point to strengths and weaknesses. A related genre is the review essay, where several books may be reviewed together. In the end, a reader of a book review will want to know what she will gain from reading the book.

Literature Review: A literature review is generally a synthesis of research on a given topic. A writer will begin by collecting research on that topic, then classify the research into subgroups (e.g., according to, for instance, dimensions of that topic or methodology or date), and then figure out her purpose. Why would a researcher write a literature review? The first reason is simply to learn about the topic. The second reason (and this is usually the challenge) is to identify a niche from which the writer can then launch her own research; maybe there’s a gap in the research, or maybe we need to explore an offshoot of earlier studies. The challenge is to not only summarize research but to stitch the research together under the writer’s purpose, which is often to assert a new research need. Note: Some disciplines refer to literature reviews as review articles (not to be confused with the book review mentioned above).

Candidacy Exam: Graduate study typically begins with coursework and proceeds with candidacy exams, a research proposal to justify the dissertation, and then dissertation research and writing. During graduate study, students learn to participate in the disciplinary community, so the writing completed for coursework can be seen as early versions of the genres above. The exam, which happens midway through a PhD program, can vary depending on the department; the exam is generally akin to the literature review and possibly the research proposal, too.