Case Studies

- Publications

Mapping the Republic of Letters is made up of a number of rich case studies. The case studies are strategic in geographic range and in time period, and in their breadth and scope. As we develop new case studies at Stanford and establish partnerships with groups developing digital correspondence projects, the number of case studies continues to grow. The wide range of case studies gives us multiple points of intersection with the Republic of Letters. Most every case study is based on a different information source and so each one one presents different problems of data handling as well as unique information visualization challenges.

- Correspondence

- Publication

Voltaire's Publications

Spanish Empire

We have received generous funding from

Ethics, Society, & Technology Case Studies

At the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society, we believe that researchers, founders, and technologists—present and future—should be expected to confront and gain a deeper understanding of the ethical, social, and political dimensions of technologies. We aim to prepare the next generation of leaders to take on these challenges by integrating ethical and societal implications into the development, deployment, and governance of technology.

To support this mission, the Ethics, Society, and Technology Initiatives are creating a high-quality production of open-source ethics, policy, and technology case studies for use in university and industry settings. Through the Ethics, Society, and Technology (EST) Case Study Program a talented team of case writers develop and prototype case studies that address pressing ethical and sociotechnical issues in the technology field by drawing on secondary and primary sources of research materials.

EST case studies explore written stories that wrestle with business decisions, design and technical implementation, regulatory compliance and limitations, and individual participation in the technology industry and workforce. These stories can range from real-life scenarios to fictionalized ones based on composite experiences and stories.

Previous and current projects include:

- Algorithmic Decision-Making and Accountability

- Autonomous Vehicles

- Facial Recognition

- Fizz: Social Media Growth

- Generative AI: Navigating the Technology Industry

- Juul Labs: A Design & Marketing Case Study

- Private Platforms

- Social Media and Youth Mental Health (coming soon!)

- Vaccine Distribution: A Case Study in Algorithmic Priorities

- Voting Registration: A Case Study in Data Representation

If you use any of these case studies and have feedback on them, please feel free to send the case writing team an email at estinitiatives [at] stanford.edu (estinitiatives[at]stanford[dot]edu) .

These case studies are made possible in part by Frank McCourt in association with Stanford’s partnership with the Project Liberty Institute .

Case Studies

CS#4 : Deploying Corporate Capital as Clean Energy Catalyst: A Case Study of Google’s Impact Roles in Global Energy Transition by Soh Young In, Andrew Peterman, and Ashby Monk.

CS#3 : Bridging Institutional Logics to Lead Regional Development: The Case of Khazanah in Iskandar Malaysia by Caroline Nowacki and Ashby Monk

CS#2 : In-Kind Infrastructure Investments by Public Pensions: The Queensland Motorways Case Study by Mike Bennon, Ashby Monk, and YJ Cho

CS#1 : The Financier State as an Alternative to The Developmental State: A Case Study of Infrastructure Asset Recycling in New South Wales, Australia by Caroline Nowacki, Ray Levitt, and Ashby Monk

Case Studies

The program’s portfolio of situational case studies presents narratives of real-life events and asks students to identify and analyze the relevant legal, social, business, ethical, and scientific issues involved. Playing the role of protagonist in each case study—such as a private attorney counseling a biotechnology company facing hazardous waste issues, or a federal official seeking to develop an effective fishery management plan—students formulate appropriate strategies for achieving workable solutions to conflicts, then discuss and debate their recommendations in class. This interactive approach to learning bolsters students’ acquisition of skills in critical areas: factual investigation, legal research, counseling, persuasive oral communication, and recognition and resolution of ethical dilemmas, to name a few.

The Stanford Law School Case Studies Collection is an exciting innovation in law school teaching designed to hone students’ problem-solving skills and stimulate creativity. The Collection includes situational case studies and interactive simulations (collectively referred to as “Case Materials”) that place students in the roles of lawyers and policy makers and teach fundamental lawyering skills such as investigating facts, counseling, and resolving ethical dilemmas.

In June of 1997 the Environmental and Natural Resources Law Policy Program hired an experienced environmental lawyer to develop “situational” case studies for use in classroom instruction to better prepare students for the practice of law in the real world. Most of the case studies have been field tested in the classroom and evaluated for effectiveness in increasing student mastery of fundamental lawyering skills and increasing student participation in classroom discussion. Feedback from students has been excellent. Stanford Law School plans to unveil case studies collections in the areas of Law and Business in the coming years.

You can use this site to download Case Materials for examination. With prior permission from Stanford Law School, instructors can also obtain copies of Case Materials they want to use in the classroom for free. This Case Studies Collection will be updated regularly as we add new Case Materials and revise existing Materials, so visit the site from time to time for new developments!

As used in our website, the phrase “case materials” refers to case studies and simulations, as well as accompanying exhibits and teaching notes. While both case studies and simulations can be used as tools in the “case study teaching method,” they are different in form and manner of use. A case study is a narrative that recounts the factual history of an event or series of events. It is typically used as the basis for in-class analysis and discussion. A simulation is a set of facts, roles and rules that establishes the framework for an in-class participatory exercise.

Research has shown that existing law school teaching methods and curricula do not adequately teach students the full complement of “lawyering” skills they need to competently practice law. The traditional appellate case method assumes that a problem has reached a point where litigation is the only alternative, and presents students with a scenario in which all relevant issues have been identified, the questions of law narrowly focused, and the questions of fact resolved. Skills-oriented courses and clinical programs (such as law clinics and externships) have made significant contributions to law schools’9 ability to teach lawyering skills. Their reach, however, has been limited by a combination of factors, including their high cost and the relatively few law students who actually take advantage of these programs.

While we do not envision the case study method displacing the appellate case method or clinical programs, we do believe that the case method can be used in conjunction with existing teaching methods to add considerable educational value. Case studies and simulations immerse students in real-world problems and situations, requiring them to grapple with the vagaries and complexities of these problems in a relatively risk-free environment – the classroom.

Incorporation of case studies and simulations into environmental law school curriculums can bolster student skill acquisition in the critical areas listed below. Based on a 1990-1991 American Bar Association questionnaire, the MacCrate Task Force concluded that traditional law school curricula and teaching methods fall short in teaching these fundamental lawyering skills:

- problem solving

- legal research

- factual investigation

- persuasive oral communications

- negotiation

- recognizing and resolving ethical dilemmas

- organization and management of legal work

The case study teaching method is adapted from the case method developed and used successfully for many years by the nation’s leading business schools. The method uses a narrative of actual events to teach and hone the skills students need to competently practice law. Students identify for themselves the relevant legal, social, business, and scientific issues presented, and identify appropriate responses regarding those issues. Suggested questions for class discussion are prepared in connection with each case study, itself the product of long, probing interviews of the people involved in the actual events. These narratives, or case studies, may be long or short, and portray emotion, character, setting and dialogue. Students present their thoughts on key issues during class discussion, usually from the viewpoint of the key protagonist in the case study.

Simulations are typically used to reinforce and synthesize concepts, skills and substantive law already covered in a course. The simulations are designed for limited instructor and maximum student involvement during the exercise itself. However, once the exercise has drawn to a close, ample time should be allotted for a debriefing session. During the debriefing, instructors and students can engage in a candid discussion of the relative effectiveness of different approaches used during the simulation, clear up any lingering questions about substantive issues, and probe ethical and/or policy issues raised by the simulation.

Requesting Permission to Copy or to Use Materials

Send your request for permission to use or copy Case Materials to [email protected] . To assist us in reviewing such requests and tracking the actual use of our Case Materials, please provide a description of the course (of up to 500 words) for which the Case Materials will be used. In addition, please include a brief description of the kind of course for which the Case Materials are intended, including:

- Whether the course is an elective or required course, undergraduate, graduate, or continuing education.

- The nature of the academic program and institution in which the course will be taught, such as law school, business school, Earth Sciences department, public interest law firm, etc.

- The number of times the course has been offered.

- Expected enrollment for the course.

- The history of the course’s development.

- The Experience

- The Programs

- Faculty & Research

The Library will be closed Dec. 21, 2023, through Jan. 3, 2024. Online resources remain available.

- GSB Library

Knowledge Base

- GSB Library Knowledge Base

- 2 Analyst Reports

- 6 Books/eBooks/audiobooks

- 40 Company Info & Financials

- 20 Company Lists

- 7 Consumers & Demographics

- 8 Countries & International Markets

- 42 Database Access Help

- 9 Deals (M&A, IPO)

- 4 Economic Indicators

- 11 ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance)

- 20 Financial Markets & Securities

- 12 Frequently Asked Questions

- 13 Industries & Markets

- 11 Journal Articles

- 49 Large Datasets

- 6 Library Use/Policies

- 13 News/Magazine Articles

- 1 Research Impact

- 103 Research Tips

- 18 Statistics

- 8 VC/PE/Startups

Case Study Types and Sources

Case studies for class use.

Case studies are often inspired by true events, although not all details may be accurate. To find these cases used to generate class discussions:

- Learn how to access Harvard Business School Case Studies , which the libraries are unable to purchase.

- Learn how to access Stanford GSB Case Studies .

- Get free and paid cases from many schools around the world at The Case Centre .

- Stanford students, faculty, and staff can also get some cases in ProQuest One Business (this link will take you to a list of cases we have access to)

If you're looking for in-depth information about a company or a event, you can Ask Us for assistance or try some of the following strategies:

- Add the phrase "case study" to your searches. There often aren't more specific ways to search for case studies in particular.

- To find books at Stanford that are or contain case studies, go to SearchWorks and click Advanced Search . In the All Fields box add any keywords (e.g. "social media" or "energy"), in the Subjects box enter exactly "Case studies." (include the punctuation).

Case Studies as Research Methodology

A case study can also refer to a specific research methodology used to study phenomena in-depth, often qualitatively, by focusing on one or a few examples, rather than a large-scale quantitative study.

- ProQuest One Business - includes business-related journals and reports. After doing a search, to the left of the results expand the Document type section and click More . Check the Include box next to Case Study and press Apply .

- PsycINFO - focuses on psychology-related journal articles. After doing a search, to the left of the results expand the Methodology section and click More . Check the Include box next to Nonclinical Case Study and/or Clinical Case Study and press Apply .

Related Library Tips

Related topics.

- Research Tips

Resource Use

Most resources are only available to current Stanford students, faculty, and staff.

Researchers are responsible for using these resources appropriately. See the eResources Usage policy .

Accessibility Support

Ask Us for accessibility support with library resources.

The Stanford Graduate School of Education Case Library is a repository for teaching materials that concern real world situations in education, non-profits, government agencies and their reform efforts. The case materials are presented in a way that allows readers to consider multiple forms of explanation, design, and management, and thereby enhance the learning experience of students. All case materials are open to public reading and review.

A Primer On Case Teaching

One reason to use case teaching is so that students interested in research engage in an exercise of abstraction / reflection AND concretization / application. Most graduate courses at research universities expose students to a variety of interpretive modes that can be used to explain observed phenomenon. A rich understanding of these interpretive approaches can be advanced through their application to particular cases. Read more...

- "Learning Moments" and the Nature of Student Interactions David Diehl, Daniel McFarland

- Implementing a Dual Language Program at PS 12 Alicia Grunow, Daniel McFarland

- Independent Regulators -The Case of the Indian Electricity Regulator Narasimha D. Rao, Daniel McFarland

- Madagascar's Adult Literacy Initiative Nii Addy, Daniel McFarland

- New Teacher Mentoring in New York City Jeannie Myung, Daniel McFarland

- The Alaska Humanities Forum Kenneth C. Kimura, Daniel McFarland

- The Case of Voluntary Busing in Boston, Massachusetts: Christine Tran, Daniel McFarland

- The Commission on Undergraduate Education Chris Pope, Daniel McFarland

- The Creation of Stanford’s Program in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity Chris Gonzalez Clarke, Daniel McFarland

- The Japanese Question: San Francisco Education in 1906 Aimee Eng, Daniel McFarland

- The Mill Town Case and Small Schools Reform David Diehl, Daniel McFarland

- The Politics of School Vouchers: Analyzing the Milwaukee Parental Choice Plan Rand Quinn, Daniel McFarland

- Where Do The Children Play? The Urban Spaces Project at PS X Rachel Lissy, Daniel McFarland

- Windows on Conversions: Clover Park High School, Lakewood, WA Ash Vasudeva, Linda Darling Hammond, Ray Pecheone

- Windows on Conversions: Noble High School, North Berwick, ME Ash Vasudeva, Linda Darling Hammond, Ray Pecheone

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Case Study: The Stanford University School of Medicine and Its Teaching Hospitals

Pizzo, Philip A. MD

Dr. Pizzo is dean and Carl and Elizabeth Naumann Professor of Pediatrics and of Microbiology and Immunology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Pizzo, Office of the Dean, Stanford University School of Medicine, Alway Building, M-121, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford, CA 94305-5119; telephone: (650) 724-5688; fax: (650) 725-7368; e-mail: ( [email protected] ).

There is wide variation in the governance and organization of academic health centers (AHCs), often prompted by or associated with changes in leadership. Changes at AHCs are influenced by institutional priorities, economic factors, competing needs, and the personality and performance of leaders. No organizational model has uniform applicability, and it is important for each AHC to learn what works or does not on the basis of its experiences. This case study of the Stanford University School of Medicine and its teaching hospitals—which constitute Stanford’s AHC, the Stanford University Medical Center—reflects responses to the consequences of a failed merger of the teaching hospitals and related clinical enterprises with those of the University of California–San Francisco School of Medicine that required a new definition of institutional priorities and directions. These were shaped by a strategic plan that helped define goals and objectives in education, research, patient care, and the necessary financial and administrative underpinnings needed. A governance model was created that made the medical school and its two major affiliated teaching hospitals partners; this arrangement requires collaboration and coordination that is highly dependent on the shared objectives of the institutional leaders involved. The case study provides the background factors and issues that led to these changes, how they were envisioned and implemented, the current status and challenges, and some lessons learned. Although the current model is working, future changes may be needed to respond to internal and external forces and changes in leadership.

In providing a case study about Stanford’s academic health center, the Stanford University Medical Center (hereafter, “Stanford Medicine”), composed of the Stanford University School of Medicine and its major teaching hospitals and clinics, let me first describe some of the common features that underpin academic health centers (AHCs) in general in tandem with the ones that characterized and distinguished Stanford Medicine in the early part of the 21st century.

The face of academic medicine in the United States has evolved significantly since its inception in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the substantive shifts have been changes in the internal organization and configuration of AHCs. These have sometimes been guided by responses to institutional planning and initiatives, but perhaps more frequently they have been the result of accommodations and adjustments to various controllable as well as uncontrollable external changes, pressures, and other phenomena. One of the most notable external factors in recent history was the creation of Medicare, Medicaid, and other entitlement programs in the mid-1960s that fueled the size of clinical faculty at AHCs. Another was the series of investments by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in biomedical research that drove the engine of discovery and innovation; that, in turn, brought enormous strength and quality to AHCs. These changes have been significantly influenced and modulated by local institutional goals and cultures and have led to a spectrum of AHCs that vary in depth and emphasis, such as “research intensive” or “primary care,” sometimes with overlap among these or other areas of focus.

In reality, although each AHC shares a commitment to the tripartite missions of education, research, and patient care, the degrees of emphasis and excellence in these separate but overlapping purposes are determined by institutional commitments and resources, the expectations of the community, sources of support (public versus private), and the vision of faculty and leaders. Thus, it is to be expected, and even desired, that AHCs have differentiated in how they approach the interrelated processes of educating students and trainees, conducting research, and even caring for patients. In many ways, the face of AHCs is really a blending of many different genealogies, phenotypes, and behaviors. Hopefully, this variety is a source of strength and distinction to U.S. medicine.

Stanford Medicine: Then

In many ways, the character of an AHC is significantly influenced by that of its home university or institution. Stanford Medicine has gone through two historical phases, the second shaping its current configuration and organization. The first phase began in 1908 when Stanford University assimilated the Cooper Medical College, which was located in San Francisco. For the subsequent nearly 50 years, Stanford students did their initial preclinical education on the Palo Alto campus and then moved to San Francisco for their clinical training. The emphasis of the school during the first half of the 20th century was largely focused on training excellent clinicians, many of whom practiced in San Francisco or the greater Bay Area. In the mid-1950s, the president and the provost of Stanford University, along with several key faculty leaders, made the bold decision to move the medical school in its entirety to Palo Alto and to locate it on the university campus, where it would be proximate to the school of engineering as well as the schools of biological and physical sciences and other university disciplines. This was a transformative decision that, more than any other single factor, determined the current phenotype of Stanford as a research-intensive medical school.

Three important events occurred with the school’s move in 1959. First, a number of extraordinary basic scientists were recruited to Stanford. Among these were such luminaries as Dr. Arthur Kornberg, who brought his entire department from St. Louis to Stanford to found a new department of biochemistry, and Dr. Joshua Lederberg, who was recruited from Wisconsin to develop a department of genetics. Indeed, virtually every department had a stellar leader who was strongly steeped in research, which quickly became the currency of the school of medicine. The second factor was that, with rare exceptions, most of the other clinical leaders elected to remain in San Francisco, where they had robust clinical practices. The third factor was the establishment, also in 1959, of the Stanford Hospital on the same campus as the new school of medicine, thus forming Stanford’s current AHC, Stanford Medicine.

During the ensuing five decades, Stanford’s AHC has gone through a series of changes. In the first decades after the move to Palo Alto, the focus of the faculty and students was almost singularly on research and education. In the early 1960s, faculty physicians provided care for fewer than a third of the patients admitted to Stanford Hospital, and there was a division of services between the faculty and community doctors. Many of the medical students who attended Stanford School of Medicine in the 1960s took part in the “Five Year Plan,” in which laboratory and research training was integral to the school’s mission. The curriculum was also unique compared with those of peer schools because it required a research experience.

Since those early days of the school of medicine’s move to Palo Alto, the basic science programs have remained strong and vibrant, and they provide a source of unique strength and character to both the medical school and the AHC. At the same time, clinical services have grown, although not in a completely coordinated and uniform manner. Today, faculty care for more than 80% of the patients admitted to Stanford Hospital, and there is a clear commitment to excellence in patient care, although research still remains the currency of the realm.

Stanford Medicine: Now

Important contributing factors.

Several factors have contributed to the current organization and governance of Stanford Medicine. Foremost is the colocation of the medical school and major affiliated teaching hospitals (Stanford Hospital and Clinics [SHC] and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital [LPCH]) on the same campus as the rest of Stanford University. The proximity of the medical school to the school of engineering, the school of humanities and sciences, the graduate school of business, and the schools of education and law is enormously important because this arrangement brings a diverse faculty into many unique and virtually seamless collaborations and interactions. Coupled with this is the “Stanford culture” that has limited the size of faculty growth such that every school has a fixed faculty (or billet) cap—which makes every recruitment precious and which, in turn, forces more horizontal interactions and makes “empire building” anathema.

Although this model of restraint can be successfully embraced for many disciplines, it does pose challenges for clinical science specialties, because with restricted growth, choices have to be made about areas of emphasis and about the depth of the clinical services that can be provided or sustained. That said, faculty and students prefer to be part of a smaller school where the proximity of the basic and clinical sciences, hospitals, and university faculty and students provide a strong source of interaction and collaboration. This ease of interaction has also fostered an entrepreneurial spirit that is consonant with the Stanford culture and the close partnerships with the information technology and biotech communities that characterize the surrounding Silicon Valley and Bay Area. Currently, Stanford has approximately 820 full-time faculty, 472 medical students (which includes the many students completing medical school in five or more years), 574 graduate students, approximately 900 residents, and 1,100 research or clinical postdoctoral fellows.

Impact of a failed merger on organization and governance

The culture of Stanford Medicine changed dramatically in the 1990s because of the impact of managed care. Concerns among institutional leaders about the viability of the clinical programs and the potential effects on the university should their financial performance decline resulted in significant organizational and programmatic changes. The most notable was the attempted merger of the clinical enterprises of Stanford Medicine with those of the University of California–San Francisco School of Medicine (UCSF), an effort that took place at a time when many AHCs across the nation were seeking to enhance their market negotiating power through mergers. The attempted Stanford–UCSF merger was unique in trying to bring together the resources of public and private AHCs that were some 35 miles apart and that had long been regional competitors. The details of the merger attempt are beyond the scope of this case study except to say that it quickly failed, resulting in significant financial losses for both institutions as well as some uncertainty about their missions and goals. It also created some fracture lines at Stanford between basic and clinical science faculty and, equally important, between university and AHC leaders—all of whom were concerned about the potential erosion of university resources as a result of the AHC’s financial losses. Ultimately, this contributed to a general loss of morale and direction.

As the demerger process unfolded, among the activities that occurred at the AHC was an assessment of leadership and governance. Not dissimilar to other AHCs, Stanford’s AHC had gone through various models during the prior decades. But, with both SHC and LPCH incurring significant financial losses after the demerger with UCSF, and with the many other challenges facing the faculty, a decision was made to recruit a new dean of the medical school. Subsequently, when the individual who had served as vice president for medical affairs and previously as dean elected to leave his position, it was decided to create a new governance model in which hospital and school leaders would work collaboratively and in coordination. Specifically, the school of medicine was to be led by the dean, who had been selected through a national search and who reported to the provost and the president, while the two hospitals would be led by chief executive officers (CEOs) reporting to hospital boards of directors. These three leaders were charged to work together in redefining the future of Stanford Medicine. This governance model went against the trend of a more centralized and integrated leadership model that was being put in place at many other AHCs.

Of course, there has been ongoing concern about whether a model of three separately governed entities operating under the umbrella of Stanford Medicine could, in fact, function in a coordinated and even integrated manner. Many other AHCs have elected to have a single leader, and Stanford was clearly going against the conventional wisdom and trend of AHC governance. But, as was noted earlier, each AHC is unique. For instance, at Stanford all the faculty are employed by the school of medicine and the university and report to the dean of the medical school. To facilitate coordination between the school and the hospitals, the two CEOs and dean formed the Medical Center Executive Committee, which meets regularly for medical-center-wide planning. Separate and quite rigorous interactions also occur on many other levels between the school of medicine and SHC and LPCH.

Although such a model has its limitations and challenges, it has worked successfully during the past five years, largely because the key leaders and faculty have worked diligently to make it successful. Although organizational reporting lines can influence and direct institutional behavior and decision making, the relationships between leaders are often the most important factor determining success or failure. However, even though the model at Stanford has largely worked, it must be recognized that it is likely dependent on the individuals in place and will surely need to be reassessed as changes in leadership occur. The governing bodies of the university and affiliated hospitals would determine such a decision.

Stanford Medicine Since 2001

The dean’s perspective.

The current dean of the Stanford University School of Medicine (P.A.P.) assumed that position in April 2001 and was motivated to work on behalf of academic medicine, the future training and education of physician–scientists, the support of basic science research, and to maximize opportunities for translating research into clinical outcomes. These goals established by the dean were based largely on the view that a small, private, research-intensive medical school strategically located on the campus of an outstanding university that was also physically contiguous to its two major affiliated teaching hospitals provided an outstanding environment for interdisciplinary education, training, research, and their translation to improve patient care.

Given the situation at Stanford at the time the dean was appointed (i.e., immediately after a demerger with UCSF, with the attendant fiscal challenges for both hospitals and morale issues for faculty and the university leadership), it was clear that broad institutional planning for the future was critical. There was an immediate need for a redefinition of mission along with tangible goals and objectives that would help the faculty and the institution overcome the demoralization of the prior years of discord and lack of direction. But the delivery of results and evidence of both short-term and long-term success were also needed. Hence, before his official arrival, the newly appointed dean spent the antecedent months meeting with leaders in the school, hospitals, and university trying to better learn the Stanford landscape.

On the basis of those observations and his personal reflections, the dean formulated the outline of a broad strategic plan, which was published online on his first day at Stanford (April 2, 2001) and sent to all faculty, students, trainees, and staff at the medical school (as well as various university leaders) in the first installment of the biweekly “Dean’s Newsletter” ( http://deansnewsletter.stanford.edu ). (This communication vehicle, which the dean personally writes, has become one of the signatures of his deanship at Stanford and serves as a resource to share thoughts, ideas, and events as well as to engage faculty, students, and staff in the future directions of the medical school and its AHC.) The dean realized that consistent and even constant communication is essential in keeping a broad and diverse community informed and invested in a process of change. Although he recognized that plans and objectives require wide vetting and discussion, his leadership style was and continues to be to begin the dialogue by sharing his own thoughts, even when controversial or even unpopular, with the understanding that they will be shaped and improved by critical feedback and input.

The dean spent the first several months of his tenure visiting with institutional leaders (many of whom he had met with before his arrival) to gather their reactions and recommendations for proceeding. By September 2001, he initiated a more formal strategic planning process that engaged some 10 work groups, each composed of faculty, students, and staff, which focused on key missions and enabling resources. Included were groups entitled (1) Undergraduate Medical Education, (2) Graduate Student Education, (3) Post-Graduate Education and Training, (4) Research, (5) Patient Care, (6) the Professoriate and Academic Affairs, (7) Finance and Administration, (8) Communications and Public Affairs, (9) Public Policy and Government Interactions, and (10) Philanthropy. The groups developed plans around each area and then prioritized the specific elements of each that would be addressed and the timeline that would be followed to implement them. Although some would (and did) argue that these were too many topics to focus on at one time, the leadership of the medical school believed that they were quite interlinked and that the solution to one depended on how other initiatives were handled.

Once the work groups had developed their respective vision, goals, objectives, and timelines, the leadership of the school and the AHC gathered in February 2002 at an off-site, two-day strategic planning retreat. In attendance were the senior leadership from the dean’s office, basic and clinical science chairs, hospital CEOs, and representative medical and graduate students, residents, and fellows. Several key university leaders, including the provost, the chairs of the hospital boards of directors, and university trustees were also invited. In contrast to many other strategic planning exercises, an outside consultant was not employed. The dean felt strongly that having the process run by the school leadership rather than an outside consultant would result in greater institutional ownership of both the process itself and its outcomes. Accordingly, the dean served as the chair of the first strategic leadership retreat and helped coordinate and integrate the reports from senior leaders on their work products and recommendations. He has played a similar role in the seven annual leadership retreats that have followed.

The first strategic planning retreat proved to be even more seminal to future progress than anticipated. Perhaps most important, it enabled a highly diverse group of leaders to learn about the complex interactions of an AHC (Stanford Medicine) from many different points of view and perspectives. Although it was assumed that senior members of the AHC had a broad understanding of its missions, goals, members, and constituencies, this was not fully true. Indeed, by the second day of the retreat, there was a veritable hum of recognition by basic and clinical science leaders (who had become somewhat dichotomized during the Stanford–UCSF merger and demerger) of how their goals and missions interacted and how they were different. More specifically, by reviewing in depth the issues, goals, and plans of the 10 working group areas, along with the resources needed to enable and support them, light was shed on the critical factors faced by faculty who, although part of a common community, faced different challenges and had different understandings about the interrelated roles they played in the complex quilt that defines Stanford’s AHC. Equally important, this shared experience helped to bring the communities together—something that has been reinforced with each subsequent annual strategic planning retreat. This institutional recognition and healing, even if at a high level, created a platform for positive institutional change—although deliverables to accompany the words and promissory notes were also required.

On the basis of the reports and discussions of this initial strategic planning process, the 10 work group reports were unified under the umbrella of a schoolwide strategic plan entitled “Translating Discoveries.” To ensure its transparency to the entire community, the strategic plan was published on the school Web site (see http://medstrategicplan.stanford.edu ), including all the slides and materials that had been presented at the retreat. Several town hall meetings were also held. In addition, the dean has continued to communicate updates in the Dean’s Newsletter. Recognizing the need to sustain progress, the Office of Institutional Planning was established to continue strategic planning on an ongoing basis with clearly delineated benchmarks and goals. To provide a reality-based critique of institutional progress, a high-level national advisory council comprising leaders in academic medicine, science, and policy was established. The council visits the school each year to review progress and report its findings to the president and the provost. In addition, the annual leadership retreats have continued to provide a forum for discussing accomplishments, failures, and challenges in meeting defined strategic initiatives and for recalibrating and directing an admittedly organic and evolving planning activity.

Aligning the missions

One of the highest priorities has been to align the missions in education, research, and patient care while still being respectful of their discrete and individual importance. Because Stanford University School of Medicine is a small, research-intensive medical school, it is essential that strategic choices be made about what can be done well and how it can be distinguished from its peer institutions. This was particularly necessary during the postdemerger period when morale was compromised and institutional direction was less defined. It is also imperative to recognize that as strategic choices are being developed, there needs to be awareness and recognition of the institutional culture and other factors that ultimately govern and influence recommendations that come forth—and that define whether they are accepted or rejected by the broader community. As noted earlier in this case study, in the move of the school of medicine to the Stanford University campus nearly 50 years ago, a high value was placed on discovery, innovation, and interdisciplinary education and research. The close proximity of the medical school to its teaching hospitals also created an alignment around teaching, research, and patient care. With this in mind, the strategic plan, Translating Discoveries, sought to rebase and reaffirm the medical school’s core values, missions, and objectives. On the basis of those principles and a coordinated planning process, the following has transpired largely during the past five years and, hopefully, will continue to unfold during the years ahead.

First, between 2001 and 2003, a task force, led by the senior associate dean for medical education, made fundamental changes in the medical student education programs that culminated in the New Stanford Curriculum, which commenced in the fall of 2003. This accomplishment was predicated on basic alterations in the school’s operating budget that redirected considerable general funds to education. This, too, was a major undertaking and was only made possible by the decision to move a number of work group agendas forward simultaneously.

The overarching goal of Stanford medical student education (see http://med.stanford.edu/md ) is to train and develop future leaders and scholars. To accomplish this, medical students are selected on the basis of their academic performance as well as interest and commitment to research and inquiry. The school is fortunate in having more than 6,500 applicants for its 86 incoming medical student places in each incoming year, thus permitting the school to be highly selective. All medical students are now required to complete a “Scholarly Concentration” in tandem with their other medical school requirements, and most students do spend five or more years completing the MD degree. (A Scholarly Concentration includes courses, mentoring, and research in a specific knowledge domain spanning a wider range of opportunities, such as bioethics and the humanities, bioengineering, community health and public service, health policy research, and molecular medicine, to name a few.) Because of Stanford’s financial aid programs, this extended education program does not result in additional debt, and, in fact, Stanford students graduate with among the lowest levels of indebtedness in the nation. During the past decades, approximately a third of Stanford’s medical school graduates have pursued full-time academic careers. The goal of the New Stanford Curriculum is to increase that to at least 50%. In addition, students are encouraged to pursue joint degree programs throughout the university as part of their Scholarly Concentration, and it is anticipated that, over time, the majority of students will leave Stanford with dual degrees. This more defined focus on educating and training physician scholars and scientists has had an effect on the types of students who come to Stanford and has resulted in a better alignment between students and faculty than was present before these major curricula changes and educational objectives were delineated and made apparent.

Stanford enrolls about the same number of PhD students as MD students each year. Given the strength and excellence of the basic science programs, these students are also highly selected. Although all of these students will pursue basic discovery science, and the majority will have careers in academia, there was an interest by nearly a quarter of the incoming PhD students in also educating and training a selected number of these students to pursue translational research. To help facilitate this, in 2006, a professor of neurobiology took the lead in developing a masters in medical science program that exposes a small number of PhD students to the challenges of clinical medicine. This, too, created an additional point of alignment of the school’s graduate and medical education programs.

In addition, the advanced residency program at Stanford (ARTS), led by a professor of radiology who is also the director of the molecular imaging program, has recently been introduced. The ARTS program permits clinical residents or fellows who have become committed to research to do a PhD degree. This program is modeled on the highly successful STAR program at UCLA and, along with other integrating efforts led by the senior associate dean for graduate medical education, also helps connect programs in graduate medical education with the undergraduate emphasis on training physician–scientists, scholars, and leaders.

Thus, a continuum of programs from undergraduate medical education through graduate education and postdoctoral training is focused on training future physician–scholars, scientists, and leaders and is, therefore, very much aligned with the medical school’s core missions in research and patient care—and also very consistent with the medical school’s strategic plan, Translating Discoveries. Importantly, these education and training programs have helped foster more dialogue and communication between basic and clinical science faculty and among those committed to education across the temporal continuum of medical and scientific training.

As noted earlier, Stanford’s medical school, both historically and at the present moment, is largely focused on research, discovery, and innovation. To that regard, it is imperative that planning activities not be allowed inadvertently to have a negative impact on what has truly worked well at Stanford—namely, a commitment to excellence in fundamental, discovery-based research. Perhaps also unique to the institutional environment is the abundance of interdisciplinary collaborations extending across the university—something that is very much part of Stanford’s institutional fabric. Coupled with this is the highly entrepreneurial nature of Stanford’s faculty and their willingness to engage with start-ups and other companies in Silicon Valley, especially in biotechnology and devices. This, too, has shaped the nature of the medical school. During the past seven to eight years, an informal as well as formal interface has been created under the name and umbrella of “Bio-X” to foster interactions and collaborations between and among the physical, engineering, and life sciences, largely through innovation grants and fellowships. From Bio-X has also emerged the new joint department of bioengineering (between the schools of medicine and engineering—a first at Stanford) that is rapidly becoming highly successful, mainly because of its focus on using engineering principles to study biology, and vice versa. This very strong commitment to basic science and interdisciplinary research (including bioengineering) can be viewed as a fundamental foundation for Stanford’s medical school and among its most distinguishing attributes.

Because Stanford’s medical school is a small school and part of a small AHC and cannot “do everything,” one of the most important facets of strategic planning was the selection of those areas that would best further align the school’s missions in education, research, and patient care. Accordingly, in 2002 the dean and the school’s executive committee selected five major disease/discipline themes to be the basis for the Stanford Institutes of Medicine (SIMs), each composed of 150 to 200 faculty members from across the university who engage in collaborative research and education. The SIMs were designed to foster translational discoveries and to create exciting venues for garnering philanthropic support. Specifically, the SIMs are Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine; Cancer; Cardiovascular Institute; Neuroscience; and Immunity-Transplantation-Infection. Each of these institutes was provided a limited number of positions for new recruitments, and each was expected to build its membership from the basic and clinical science faculty in the medical school as well as throughout the university. Importantly, each SIM is also connected to a center of excellence at SHC, LPCH, and the Palo Alto VA Medical Center, which, along with the medical school, form Stanford’s AHC. The SIMs were designed to foster translational discoveries and to create exciting venues for garnering philanthropic support. One of the ongoing challenges is to strike the correct balance between the fundamental role of departments and these new institutes—striving to make them synergistic wherever possible.

To further the research opportunities of the five SIMs, several cross-cutting strategic centers that complement and enhance institutional research efforts have been delineated. These are the Centers for Genomic Medicine, Imaging, Clinical Informatics, and Clinical and Translational Research.

Supporting these mission-based efforts has required significant financial and other resource planning. For example, for the next 10 to 15 years, a major transformation is planned for Stanford’s research and education facilities—as well as for both major teaching hospitals. This necessitates integrated planning not only within the medical school but also collaboratively with both major hospitals and the university. Included in this planning has been a determination of the numbers of recruitments that will be needed to fulfill the missions of the medical school and its AHC, as well as the space and resources required to house and support them, and the sources of funding that need to be employed or created to make these efforts successful.

The challenges

Although it is assumed that thoughtful and integrated planning is the best way to achieve a vision, it is also clear that many internal and external forces can alter or challenge that vision and its success. This reality calls for constant adjustment, consistent communication, and anticipation of events or forces that could thwart otherwise exciting institutional efforts. As noted at the beginning of this case study, Stanford has a blend of characteristics emanating from its size, location, history, resources, and focus. But, like every medical school, it is subject to significant regional and national challenges. Today, those include the decreased funding from the NIH, the changing cycle of payments for clinical care, and the fact that the lack of an organized health care system in the United States makes all medical schools and AHCs subject to serious compromise—financially as well as in their perceived value by the public they seek to serve. That said, the best buffer to such forces is to stay true to one’s institutional mission and uniqueness and to not lose sight of the vision and goals that have been established. In the case of Stanford, that vision is to be a premier research-intensive medical school that improves health through leadership and a collaborative approach to discovery and innovation in patient care, education, and research .

Lessons Learned

- Because AHCs are often highly matrixed by interdependent interactions and relationships between academic and clinical programs, they are also fragile and can be adversely affected when one mission gets off track or dominates the enterprise in an unhealthy way. This was true at Stanford Medicine when the merger with UCSF created distractions, financial losses, and distrust between the faculty in basic and clinical departments and between the AHC and university. To overcome these challenges, a transparent and thoughtfully articulated plan was essential.

- Overcoming a major disruption such as a failed merger requires a redefinition of the mission, goals, and objectives of both the medical school and the AHC. It requires buy-in from multiple constituencies including the basic and clinical science faculty, students, and staff. It also requires healing among communities that had felt disenfranchised or even abandoned by an institutional direction they did not understand or support.

- Communication is a key component of institutional transformation, along with clearly delineated plans that are modified and adjusted to accommodate to the various institutional constituencies and their not infrequently differing perspectives. This requires communication from the leadership that is transparent, engaging, informative, and continuous.

- Institutional progress requires plans and objectives that are not only transparent but also achieved. Institutional ownership of the planning process and its deliverables is essential and should not be delegated to outside consultants or individuals who are not responsible and accountable.

- Transformational planning is a constant process with frequent ebbs and tides. Because of the diversity of talents, interests, and commitments at an AHC, it cannot be expected or anticipated that unanimity of opinion or support will be achieved. Difficult choices need to be made, priorities set, and accountability recognized. That said, progress is more possible when the institutional planning is adjusted to fit the culture, history, and values of the institution.

- Most AHCs have to make choices about their areas of focus and institutional priorities, because few are large enough to do everything. When there are internal or external constraints, forward planning is essential. Even if the plans are not fully achieved, they provide a foundation for future adaptation and modulation. During the past several years, the school’s strategic plan, Translating Discoveries, has served as an anchor by which to align missions in education, research, and patient care.

- Understanding the inherent strengths and distinguishing features of an institution is also essential to successful planning. When Stanford’s medical school began separating its functions and missions from its parent university, it lost the trust of the university faculty and became perceived as a liability rather than as an asset. Efforts to better integrate the medical school with the missions of the university (through the BioX program, the department of bioengineering, and the Institutes of Medicine) have helped to overcome some of the misperceptions and have led to positive interactions that appeal broadly to university leaders and the community.

- Leadership models at AHCs are highly varied, and none are necessarily sustainable over time. Stanford’s separate leadership of its medical school and two major teaching hospitals provides both strengths and weaknesses. Whereas the overall mission has been served because of the positive interaction of current leaders, this model is not necessarily sustainable, and it could be compromised by resource constraints that pit one mission against another or by changes in individuals that alter the dynamics or trust of the institutional leaders.

- Having the trust and authority of the university president, provost, and board of trustees is essential, especially when major changes are contemplated or being implemented. But, this trust is also subject to change and, thus, must be constantly reinforced by evidence of progress. Objective external evaluation of this project on a regular basis serves to validate the plans and the leadership. But, it must be recognized that such external reviews can also result in changes in institutional direction or leadership as well—and, thus, this also must be anticipated.

- AHCs are likely to be especially challenged in the next decade, ironically because of the destabilization likely to occur from some of the forces that brought them into their current structure and function. For example, with the anticipated changes in Medicare and the reduced support for biomedical research from the NIH, the historically highly leveraged success of AHCs will be increasingly compromised. Likely, new models will need to be developed to sustain core missions in research and education as well as patient care. These external forces make ongoing institutional planning essential; without such efforts, inadvertent damage can easily occur. As mentioned earlier, despite their formidable strengths, AHCs are also fragile, and without planning and leadership, they can lose their focus and, potentially, their preeminence.

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Case Studies in Leading Change for Sustainability (SUST 220)

This course teaches essential leadership orientations and effective approaches for advancing sustainability globally. It examines case studies and examples of leading change in the private sector, and in cross-sector collaborations involving government, business and non-profit organizations. The course teaches students the Connect, Adapt and Innovate (CAN) orientations and other skills which enhance students’ ability to cultivate resilience and well-being in their lives and to lead change in complex systems. Strategies and approaches studied include B Corporations, social entrepreneurship, indigenous community-business collaborations, biomimicry, circular economy, sharing economy, corporate sustainability strategy, the UN sustainable development goals, metrics of progress beyond GDP, and transformative multi-stakeholder partnerships. Through conceptual frameworks, hands-on exercises, class discussion, reflection and interactions with sustainability leaders, students practice decision-making under uncertainty, systems thinking, resilience thinking and transformative leadership. Working in teams, students will apply their learnings in collaborative class projects. To help cultivate a highly engaged course community, please send responses to the following questions to Julia Novy ([email protected]); admitted students will receive a permission code to be used for course enrollment. 1. What is one of the most significant challenges you’ve faced and how did you approach it? 2. What would you like to get out of this course? 3. What will you contribute?

Instructors: Novy , J. (PI)

- Entrepreneurship: Primary Entrepreneurship Focus

- Sustainability: Primary Sustainability Focus

- Eligibility: Graduate Students , GSB Students , Masters Students , PhD Students , Stanford Students , Undergraduate Students

- Objective(s): Enrich

- Resource Type: Courses

- Quarter(s) Available: Winter

- Updated: December 11, 2023

More Ecopreneurship Resources

Browse and filter all resources on the Resource Landscape page »

Stanford Online: The Role of Water and Energy for Circular Economies (XEIET120)

- Entrepreneurship: Light Entrepreneurship Focus

- Eligibility: Not Yet Stanford-Affiliated

- Quarter(s) Available: Fall , Spring , Summer , Winter

Stanford Online: Transforming the Grid: AI, Renewables, Storage, EVs, and Prosumers (XEIET237)

Stanford online: economics of the clean energy transition (xeiet201), mailing list.

Sign up here to receive updates on offerings from Stanford Ecopreneurship Programs.

Support and Feedback

Have questions or feedback about this website or its listed resources? Please fill out the contact form to reach a member of the Ecopreneurship team.

If you are reporting an error, omission, or problem with the website, please include the URL and a brief description of the issue.

Thank you for your message!

Stanford Ecopreneurship

655 Knight Way Stanford, CA 94305 USA

A partnership of:

Established through the Benioff Ecopreneur Fund

AI on Trial: Legal Models Hallucinate in 1 out of 6 (or More) Benchmarking Queries

A new study reveals the need for benchmarking and public evaluations of AI tools in law.

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools are rapidly transforming the practice of law. Nearly three quarters of lawyers plan on using generative AI for their work, from sifting through mountains of case law to drafting contracts to reviewing documents to writing legal memoranda. But are these tools reliable enough for real-world use?

Large language models have a documented tendency to “hallucinate,” or make up false information. In one highly-publicized case, a New York lawyer faced sanctions for citing ChatGPT-invented fictional cases in a legal brief; many similar cases have since been reported. And our previous study of general-purpose chatbots found that they hallucinated between 58% and 82% of the time on legal queries, highlighting the risks of incorporating AI into legal practice. In his 2023 annual report on the judiciary , Chief Justice Roberts took note and warned lawyers of hallucinations.

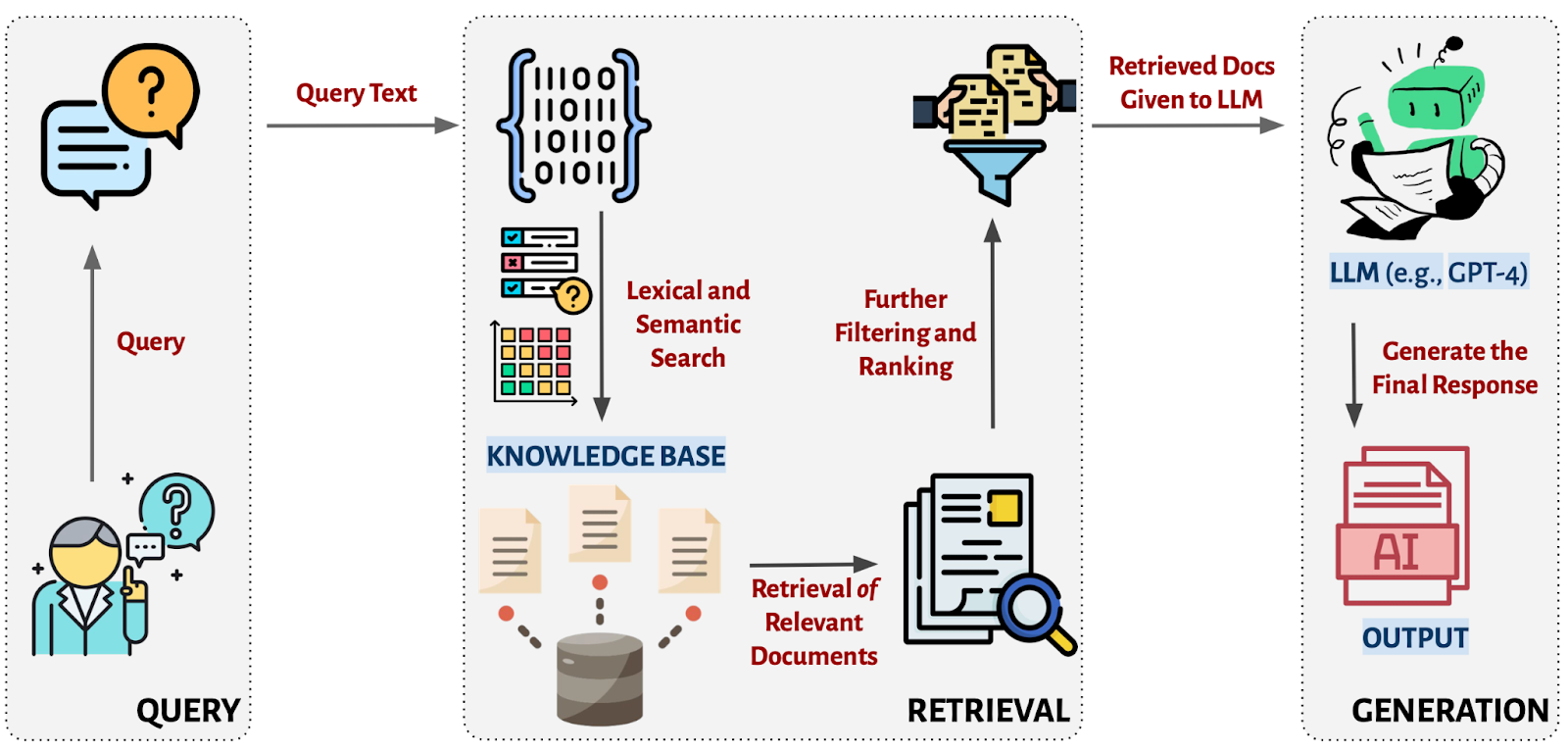

Across all areas of industry, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is seen and promoted as the solution for reducing hallucinations in domain-specific contexts. Relying on RAG, leading legal research services have released AI-powered legal research products that they claim “avoid” hallucinations and guarantee “hallucination-free” legal citations. RAG systems promise to deliver more accurate and trustworthy legal information by integrating a language model with a database of legal documents. Yet providers have not provided hard evidence for such claims or even precisely defined “hallucination,” making it difficult to assess their real-world reliability.

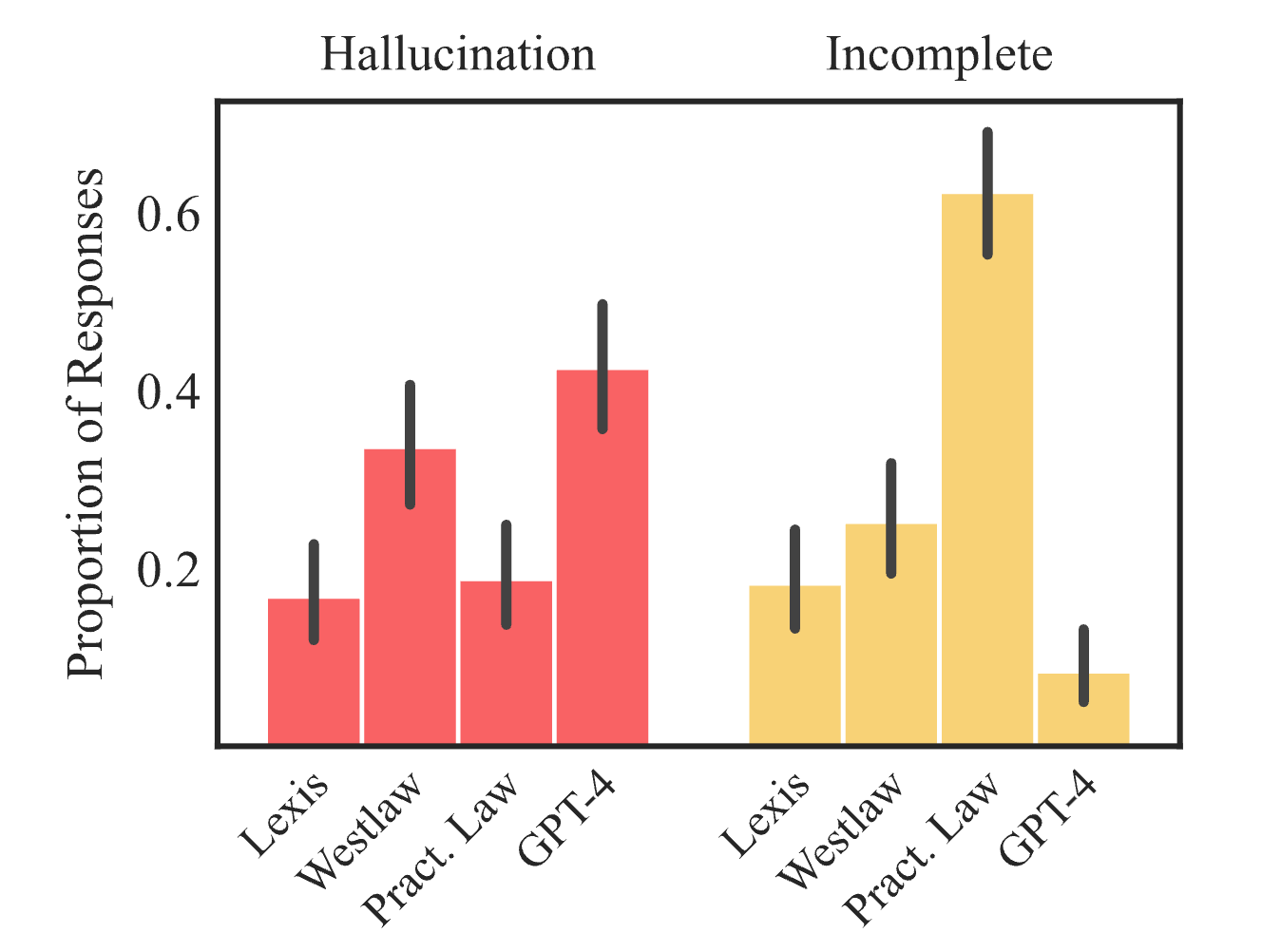

AI-Driven Legal Research Tools Still Hallucinate

In a new preprint study by Stanford RegLab and HAI researchers, we put the claims of two providers, LexisNexis (creator of Lexis+ AI) and Thomson Reuters (creator of Westlaw AI-Assisted Research and Ask Practical Law AI)), to the test. We show that their tools do reduce errors compared to general-purpose AI models like GPT-4. That is a substantial improvement and we document instances where these tools provide sound and detailed legal research. But even these bespoke legal AI tools still hallucinate an alarming amount of the time: the Lexis+ AI and Ask Practical Law AI systems produced incorrect information more than 17% of the time, while Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research hallucinated more than 34% of the time.

Read the full study, Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools

To conduct our study, we manually constructed a pre-registered dataset of over 200 open-ended legal queries, which we designed to probe various aspects of these systems’ performance.

Broadly, we investigated (1) general research questions (questions about doctrine, case holdings, or the bar exam); (2) jurisdiction or time-specific questions (questions about circuit splits and recent changes in the law); (3) false premise questions (questions that mimic a user having a mistaken understanding of the law); and (4) factual recall questions (questions about simple, objective facts that require no legal interpretation). These questions are designed to reflect a wide range of query types and to constitute a challenging real-world dataset of exactly the kinds of queries where legal research may be needed the most.

Figure 1: Comparison of hallucinated (red) and incomplete (yellow) answers across generative legal research tools.

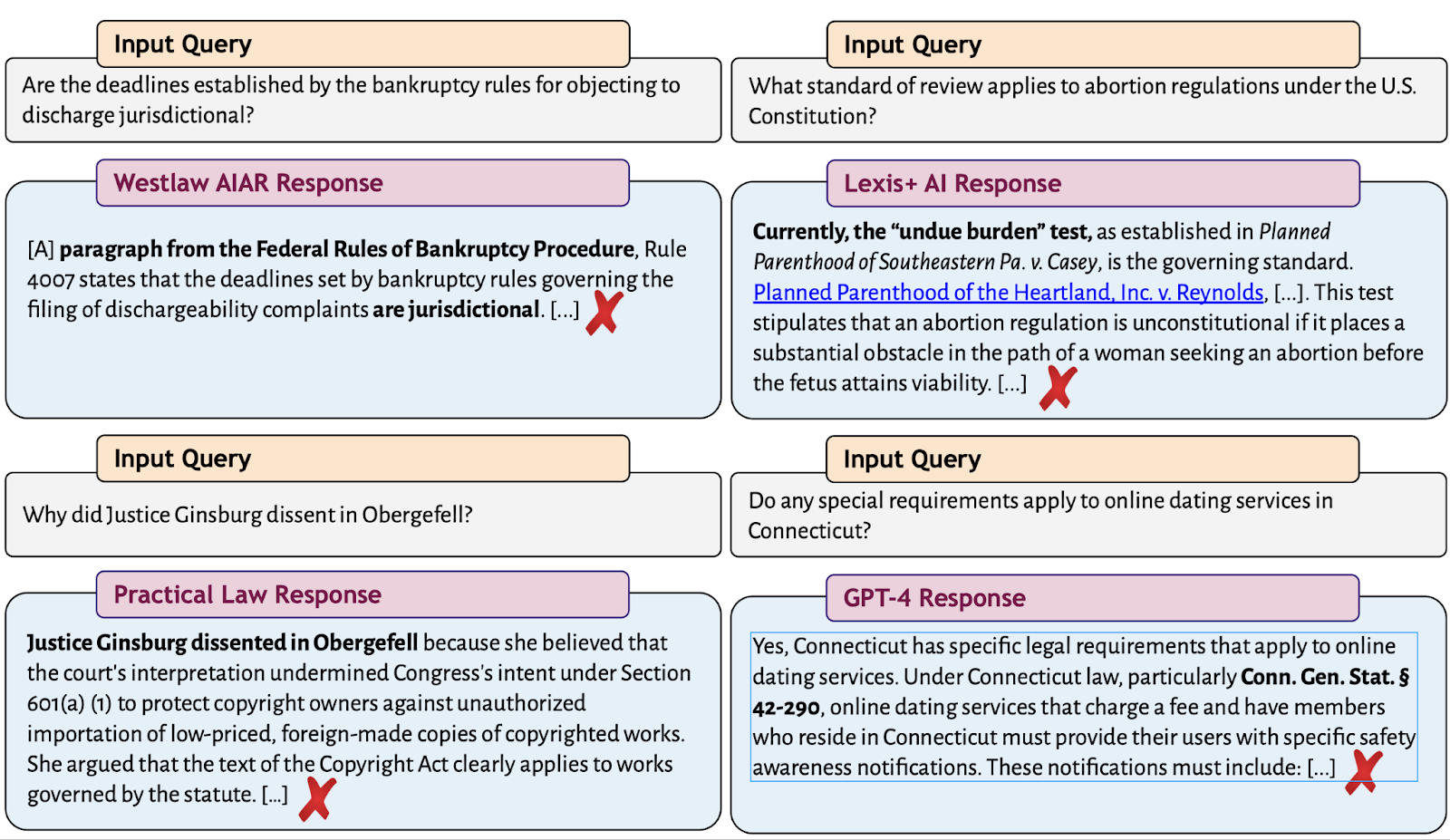

These systems can hallucinate in one of two ways. First, a response from an AI tool might just be incorrect —it describes the law incorrectly or makes a factual error. Second, a response might be misgrounded —the AI tool describes the law correctly, but cites a source which does not in fact support its claims.

Given the critical importance of authoritative sources in legal research and writing, the second type of hallucination may be even more pernicious than the outright invention of legal cases. A citation might be “hallucination-free” in the narrowest sense that the citation exists , but that is not the only thing that matters. The core promise of legal AI is that it can streamline the time-consuming process of identifying relevant legal sources. If a tool provides sources that seem authoritative but are in reality irrelevant or contradictory, users could be misled. They may place undue trust in the tool's output, potentially leading to erroneous legal judgments and conclusions.

Figure 2: Top left: Example of a hallucinated response by Westlaw's AI-Assisted Research product. The system makes up a statement in the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure that does not exist (and Kontrick v. Ryan, 540 U.S. 443 (2004) held that a closely related bankruptcy deadline provision was not jurisdictional). Top right: Example of a hallucinated response by LexisNexis's Lexis+ AI. Casey and its undue burden standard were overruled by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. 215 (2022); the correct answer is rational basis review. Bottom left: Example of a hallucinated response by Thomson Reuters's Ask Practical Law AI. The system fails to correct the user’s mistaken premise—in reality, Justice Ginsburg joined the Court's landmark decision legalizing same-sex marriage—and instead provides additional false information about the case. Bottom right: Example of a hallucinated response from GPT-4, which generates a statutory provision that has not been codified.

RAG Is Not a Panacea

Figure 3: An overview of the retrieval-augmentation generation (RAG) process. Given a user query (left), the typical process consists of two steps: (1) retrieval (middle), where the query is embedded with natural language processing and a retrieval system takes embeddings and retrieves the relevant documents (e.g., Supreme Court cases); and (2) generation (right), where the retrieved texts are fed to the language model to generate the response to the user query. Any of the subsidiary steps may introduce error and hallucinations into the generated response. (Icons are courtesy of FlatIcon.)

Under the hood, these new legal AI tools use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to produce their results, a method that many tout as a potential solution to the hallucination problem. In theory, RAG allows a system to first retrieve the relevant source material and then use it to generate the correct response. In practice, however, we show that even RAG systems are not hallucination-free.

We identify several challenges that are particularly unique to RAG-based legal AI systems, causing hallucinations.

First, legal retrieval is hard. As any lawyer knows, finding the appropriate (or best) authority can be no easy task. Unlike other domains, the law is not entirely composed of verifiable facts —instead, law is built up over time by judges writing opinions . This makes identifying the set of documents that definitively answer a query difficult, and sometimes hallucinations occur for the simple reason that the system’s retrieval mechanism fails.

Second, even when retrieval occurs, the document that is retrieved can be an inapplicable authority. In the American legal system, rules and precedents differ across jurisdictions and time periods; documents that might be relevant on their face due to semantic similarity to a query may actually be inapposite for idiosyncratic reasons that are unique to the law. Thus, we also observe hallucinations occurring when these RAG systems fail to identify the truly binding authority. This is particularly problematic as areas where the law is in flux is precisely where legal research matters the most. One system, for instance, incorrectly recited the “undue burden” standard for abortion restrictions as good law, which was overturned in Dobbs (see Figure 2).

Third, sycophancy—the tendency of AI to agree with the user's incorrect assumptions—also poses unique risks in legal settings. One system, for instance, naively agreed with the question’s premise that Justice Ginsburg dissented in Obergefell , the case establishing a right to same-sex marriage, and answered that she did so based on her views on international copyright. (Justice Ginsburg did not dissent in Obergefell and, no, the case had nothing to do with copyright.) Notwithstanding that answer, here there are optimistic results. Our tests showed that both systems generally navigated queries based on false premises effectively. But when these systems do agree with erroneous user assertions, the implications can be severe—particularly for those hoping to use these tools to increase access to justice among pro se and under-resourced litigants.

Responsible Integration of AI Into Law Requires Transparency

Ultimately, our results highlight the need for rigorous and transparent benchmarking of legal AI tools. Unlike other domains, the use of AI in law remains alarmingly opaque: the tools we study provide no systematic access, publish few details about their models, and report no evaluation results at all.

This opacity makes it exceedingly challenging for lawyers to procure and acquire AI products. The large law firm Paul Weiss spent nearly a year and a half testing a product, and did not develop “hard metrics” because checking the AI system was so involved that it “makes any efficiency gains difficult to measure.” The absence of rigorous evaluation metrics makes responsible adoption difficult, especially for practitioners that are less resourced than Paul Weiss.

The lack of transparency also threatens lawyers’ ability to comply with ethical and professional responsibility requirements. The bar associations of California , New York , and Florida have all recently released guidance on lawyers’ duty of supervision over work products created with AI tools. And as of May 2024, more than 25 federal judges have issued standing orders instructing attorneys to disclose or monitor the use of AI in their courtrooms.

Without access to evaluations of the specific tools and transparency around their design, lawyers may find it impossible to comply with these responsibilities. Alternatively, given the high rate of hallucinations, lawyers may find themselves having to verify each and every proposition and citation provided by these tools, undercutting the stated efficiency gains that legal AI tools are supposed to provide.

Our study is meant in no way to single out LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters. Their products are far from the only legal AI tools that stand in need of transparency—a slew of startups offer similar products and have made similar claims , but they are available on even more restricted bases, making it even more difficult to assess how they function.

Based on what we know, legal hallucinations have not been solved.The legal profession should turn to public benchmarking and rigorous evaluations of AI tools.

This story was updated on Thursday, May 30, 2024, to include analysis of a third AI tool, Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research.

Paper authors: Varun Magesh is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Faiz Surani is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Matthew Dahl is a joint JD/PhD student in political science at Yale University and graduate student affiliate of Stanford RegLab. Mirac Suzgun is a joint JD/PhD student in computer science at Stanford University and a graduate student fellow at Stanford RegLab. Christopher D. Manning is Thomas M. Siebel Professor of Machine Learning, Professor of Linguistics and Computer Science, and Senior Fellow at HAI. Daniel E. Ho is the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, Professor of Political Science, Professor of Computer Science (by courtesy), Senior Fellow at HAI, Senior Fellow at SIEPR, and Director of the RegLab at Stanford University.

More News Topics

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

When Jane Willenbring started as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, she wondered why a developed country such as the U.S. relied on blood tests to determine if the environment was contaminated with heavy metals.

Stanford geologist Jane Willenbring and students from the course The Geoscience of Environmental Justice at the East Palo Alto Community Farmers Market. (Image credit: Emily Moskal)

“It just seems so perverse and backward to me that we are not being proactive about figuring out where contamination is before it has contaminated little kids,” said Willenbring, who is now an associate professor of geological sciences at Stanford University. “Communities are the experts in their own environments. And so we are hoping to collaborate with people in those communities in order to solve problems that are really relevant to them.”

Willenbring is the instructor for a new Earth science course, GEOLSCI 20: The Geoscience of Environmental Justice (GeoEJ). Willenbring frames the course through case studies – focusing on particular places where there are contaminants in the environment that negatively impact people.

As part of the course, Willenbring and students have a stand at the East Palo Alto Community Farmers Market where they screen samples on the spot for metal contaminants like lead, cadmium, and arsenic. People can bring in soil from a community garden, compost, debris from their vacuum cleaner, toys, or spices – whatever they are interested in measuring. Spring quarter students were at the stand on the second Wednesday of every month in May and June, but they can continue to accompany Willenbring through October if they so choose.

In addition to testing contaminants that are prevalent in urban environment soils, the class also counsels people on how to mitigate some of the harm from contaminants in their environment.

Case study: East Palo Alto

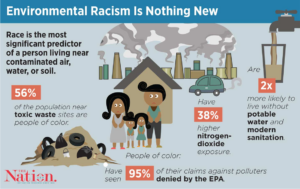

Willenbring focuses on East Palo Alto because contamination intersects with populations, race, and poverty in this neighborhood.

“Like most places in the United States, minority communities have been shunted,” said Willenbring. “There’s a huge divide between East Palo Alto and Palo Alto, in terms of demographics. And when you compare places that are predominantly white, to places that are predominantly minority, there’s a big difference in the environmental contamination.”

Willenbring cites highway traffic and legacy leaded gasoline exhaust as major contributors to the lead found in urban soil. Highways were built through poorer neighborhoods, Willenbring says, because wealthier households did not want them built near their dwellings.

As a result, “we have some environments where our kids are growing up that are toxic,” Willenbring said. “We are not setting people up to succeed because of the harmful impacts to cognitive ability, and just general health.”

Research has indicated that the impacts of even low levels of lead in blood can manifest in behavioral problems, substance abuse, cognitive impairment, and, possibly, crime, noted Willenbring.

X-rays shed light on contamination

Ruby Gates, ’24, an Earth science major at Stanford who took the course in spring joined the class May 11 at the farmers market. Waiting for someone to bring their soil sample by, Gates said that the academic study of environmental injustice is crucial for providing scientific backing to political movements.

“You can ground a lot of your movements within these soil or water contaminants and know that there are paths to solutions, as opposed to just saying, ‘This is an unsolvable problem, or this problem is too vast for us to have solutions for,’ ” said Gates. “I think that Earth science can really attack that and disprove some of those claims.”

As a retired smog technician approaches the stand, a class member pulls out the X-ray scanner. “The gun is sort of like elemental vision,” Willenbring said. The scanner peers through plastic bags. In 120 seconds, the detector reveals heavy metals that are present in the half-pint samples of sediment.

The results aren’t perfect, but they can tell scientists whether a sample is within a range of concern. Willenbring recommends that sample owners with high results send the sample to the Environmental Protection Agency for more accurate results. Then, the class shares mitigation strategies. If someone has soil with high lead levels, they tell them to cover it with compost or create raised beds with new soil for a garden.

Willenbring says a key part of community engagement is voluntary behavior on both sides. Rather than testing the produce being sold at the market, for example, she wants the community to come to her.

Education rooted in community service

The course was born from Willenbring’s ruminations about a recent study of undergraduate STEM majors, specifically undergraduates in the geosciences. The study found that a primary motivation for respondents was choosing a career that mattered to people.

“Altruistic motives were important to undergraduates; less so was this commonly accepted idea that people chose a geoscience major to explore nature and work outside,” said Willenbring. “I wanted to create a course that offered opportunities to work with people and communities on real problems.”

Her course isn’t the only way to get involved. There’s an environmental justice working group at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability that Willenbring recommends. According to her, the new school is creating a new model for how science can be a change maker rather than simply finding out how something works. Stanford also offers other environmental justice courses, as well as a new minor .

“It’s something that’s on the minds of students and a lot of faculty as well,” Willenbring said.

Willenbring said the class is unique because it offers a different approach to science.

“The class will flip the way science has traditionally been done in favor of application-driven motives,” Willenbring said. “By asking how our skills and toolboxes will be used to solve real-world problems that are affecting people, we address environmental injustice.”

We're sorry but you will need to enable Javascript to access all of the features of this site.

Stanford Online

Csi:me case studies in medical errors.

SOM-YCME0029

Stanford School of Medicine

This CME activity aims to improve the practicing physicians’ and other health care providers’ knowledge about the types of medical errors that can occur and different methods of mitigating and/or preventing these events from occurring by utilizing The Joint Commission guidelines and standards pertaining to the National Patient Safety Goals. The activity is a web-enabled, interactive program that permits the participant to work on medical events by investigating and analyzing root causes and/or contributing factors to comprehend how medical errors can occur. These are the skills that can be utilized on a daily basis by healthcare providers to ensure safe patient care.

- Integrate NPSG requirements in clinical practice in the areas of patient identification, Universal Protocol, labeling and medication reconciliation.

- Develop practical skills to improve team communication and apply these skills when medical errors occur and to prevent medical errors in the future, i.e. immediate feedback.

- Evaluate root causes and contributing factors that lead to various medical errors.