An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- World Psychiatry

- v.21(3); 2022 Oct

Psychiatric diagnosis and treatment in the 21st century: paradigm shifts versus incremental integration

Dan j. stein.

1 South African Medical Research Council Unit on Risk and Resilience in Mental Disorders, Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town South Africa

Steven J. Shoptaw

2 Division of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles CA, USA

Daniel V. Vigo

3 Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, Canada

4 Centre for Global Mental Health, Health Service and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London UK

Pim Cuijpers

5 Department of Clinical, Neuro and Developmental Psychology, Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam The Netherlands

Jason Bantjes

6 Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town South Africa

Norman Sartorius

7 Association for the Improvement of Mental Health Programmes, Geneva Switzerland

8 Department of Psychiatry, University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli”, Naples Italy

Psychiatry has always been characterized by a range of different models of and approaches to mental disorder, which have sometimes brought progress in clinical practice, but have often also been accompanied by critique from within and without the field. Psychiatric nosology has been a particular focus of debate in recent decades; successive editions of the DSM and ICD have strongly influenced both psychiatric practice and research, but have also led to assertions that psychiatry is in crisis, and to advocacy for entirely new paradigms for diagnosis and assessment. When thinking about etiology, many researchers currently refer to a biopsychosocial model, but this approach has received significant critique, being considered by some observers overly eclectic and vague. Despite the development of a range of evidence‐based pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, current evidence points to both a treatment gap and a research‐practice gap in mental health. In this paper, after considering current clinical practice, we discuss some proposed novel perspectives that have recently achieved particular prominence and may significantly impact psychiatric practice and research in the future: clinical neuroscience and personalized pharmacotherapy; novel statistical approaches to psychiatric nosology, assessment and research; deinstitutionalization and community mental health care; the scale‐up of evidence‐based psychotherapy; digital phenotyping and digital therapies; and global mental health and task‐sharing approaches. We consider the extent to which proposed transitions from current practices to novel approaches reflect hype or hope. Our review indicates that each of the novel perspectives contributes important insights that allow hope for the future, but also that each provides only a partial view, and that any promise of a paradigm shift for the field is not well grounded. We conclude that there have been crucial advances in psychiatric diagnosis and treatment in recent decades; that, despite this important progress, there is considerable need for further improvements in assessment and intervention; and that such improvements will likely not be achieved by any specific paradigm shifts in psychiatric practice and research, but rather by incremental progress and iterative integration.

Psychiatry has over the course of its history been characterized by a range of different models of and approaches to mental disorder, each perhaps bringing forward some advances in science and in services, but at the same time also accompanied by considerable critique from within and without the field.

The shift away from psychoanalysis in the latter part of the 20th century was accompanied by key scientific and clinical advances, including the introduction of a wide range of evidence‐based pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies for the treatment of mental disorders. However, there has also been an extensive critique of pharmacological and cognitive‐behavioral interventions, whether focused on concerns about their “medical model” foundations, or emphasizing the need to build community psychiatry and to scale up these treatments globally 1 .

In the 21st century, global mental health has become an influential novel perspective on mental disorders and their treatment. This emergent discipline builds on advances in cross‐cultural psychiatry, psychiatric epidemiology, implementation science, and the human rights movement 2 . Global mental health has given impetus to a wide range of mental health research as well as to clinical strategies such as task‐shifting, with evidence that these are effective in diverse contexts and may be suitable for roll‐out at scale 3 . It is noteworthy, however, that global mental health has in turn been critiqued for inappropriate and imperial exportation of Western constructs to the global South 4 .

Psychiatric nosology has been a particular focus of both advances in and critique from the field. The 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III) was paramount, providing an approach that attempted to eschew different models of etiology, focusing instead on reliable diagnostic constructs 5 . These constructs became widely used in epidemiological studies of mental illness, in psychiatric research on etiology and treatment, as well as in daily clinical practice throughout the world. The most recent editions of the DSM (DSM‐5) and of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐11) by the World Health Organization (WHO) have drawn on and given impetus to a considerable body of work in nosological science 6 , 7 .

Early on, psychoanalytic psychiatry criticized DSM diagnostic constructs for missing core psychic phenomena. With increasing concerns that these constructs have insufficient validity, neuroscientifically informed psychiatry has put forward approaches to assessing behavioral phenomena that emphasize laboratory models 8 . Despite the growing body of nosology science instantiated by the DSM‐5 and ICD‐11, many have argued for new paradigms of classification and assessment – e.g., the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) and other novel statistical approaches, and digital phenotyping.

Where do things stand currently with regard to psychiatry's models of and approaches to mental disorder? What are current clinical practices? What novel perspectives are being proposed, and what is the evidence base for them? To what extent will newly introduced models of clinical intervention, such as shared decision‐making or transdiagnostic psychotherapies, and novel approaches in psychiatric research, such as the use of “big data” in neurobiological research and treatment outcome prediction, have transformative impact for clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

In this paper we discuss proposed shifts to clinical neuroscience and personalized pharmacotherapy, innovative statistical approaches to psychiatric nosology and assessment, deinstitutionalization and community mental health care, the scale‐up of evidence‐based psychotherapy, digital phenotyping and digital therapies, and global mental health and task‐sharing approaches. We chose these novel perspectives because they have achieved particular prominence recently, and because many have argued that they will significantly impact psychiatric practice and research in the future.

We consider the extent to which proposed transitions from current practices to these novel perspectives reflect hype or hope, and whether they represent paradigm shifts or iterative progress in psychiatric research and practice. Although the contrast between hype and hope is itself likely oversimplistic, with many newly proposed models and approaches in psychiatry representing neither of these polar extremes, our point of departure is that false promises of paradigm shifts in health care may entail significant costs, while hope may justifiably be considered an important virtue for health professions 9 . We begin with a brief consideration of current models and approaches in psychiatric practice.

CURRENT MODELS AND APPROACHES IN PSYCHIATRY

Current practice in psychiatry varies in different parts of the world, but there are some important universalities. The duration and depth of training in psychiatry during the undergraduate and postgraduate years also differ across countries, but typically a general training in medicine and surgery is followed by specialized training in psychiatry, with exposure to both inpatient and outpatient settings. Globally, inpatient psychiatry focuses predominantly (but not exclusively) on severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, while outpatient psychiatry focuses predominantly (but again not exclusively) on common mental disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. In inpatient settings, psychiatrists are often leaders of a multidisciplinary team, with the extent and depth of this multidisciplinarity dependent on local resources. There are differences in sub‐specialization across the globe, but in many countries recognized sub‐specialties include child and adolescent psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, and forensic psychiatry 10 .

A particularly important shift in the 20th century has been the process of deinstitutionalization, particularly in high‐income countries. Thus, there has been a decrease of bed numbers in specialized psychiatric hospitals, but an increase of these numbers in general medical hospitals, with variable strengthening of community services. It has been argued that, when it comes to mental health services, all countries are “developing”, since there is a relative underfunding of such services in relation to the burden of disease 1 .

Currently, the two major classification systems in psychiatry are the DSM‐5 and the ICD‐11. The DSM system is more commonly used by researchers, while the ICD is a legally mandated health data standard. The operational criteria and diagnostic guidelines included in the DSM‐III, the ICD‐10, and subsequent editions of the manuals have exerted considerable influence on modern psychiatry. They not only increase reliability of diagnosis, but also have clinical utility, since they provide clinicians with an approach to conceptualizing disorders and to communicating about them 11 , 12 . They have also played a key role in research, ranging from studies of the neurobiology of mental disorders, through to studies of interventions for particular conditions, and on to clinical and community epidemiological surveys.

However, there has also been considerable critique of the reliance of modern psychiatry on the DSM and the ICD. The notion that psychiatric diagnosis is itself “in crisis” has come both from within the field and from external critics. Two somewhat contradictory critiques have been that in daily practice the DSM and ICD criteria or guidelines are seldom applied formally by clinicians, and that over‐reliance on those criteria or guidelines leads to a checklist approach to assessment that ignores relevant symptoms and important contextual issues falling outside the focus of the nosologies. Additional key critiques have been that psychiatric diagnoses lack scientific validity, and that current nosologies are biased by influences such as that of the pharmaceutical industry 13 , 14 .

When thinking about etiology, many clinicians and researchers currently default to a biopsychosocial model acknowledging that a broad range of risk and protective factors are involved in the development and perpetuation of mental disorders. This model was introduced by G. Engel in an attempt to move from a reductionistic biomedical approach to include also psychological and social dimensions 15 . The model has important strengths insofar as it takes a systems‐based approach that considers a broad range of variables influencing disease onset and course, and attends to both the relevant biomedical disease and the patient's experience of illness 16 .

Nevertheless, the biopsychosocial approach has received significant critique. In particular, it has been argued that the biomedical model critiqued by Engel is a straw man, and that the biopsychosocial approach is overly eclectic and vague. By saying that all mental disorders have biological, psychological and social contributory factors, we are unable to be specific about any particular condition, and to target treatments accordingly 17 , 18 . While there are few data available on how rigorously psychiatrists consider the range of risk and protective factors in clinical work, a review of the research literature indicates ongoing work on multiple “difference‐makers”, distributed across a wide range of categories 19 .

Psychiatrists are trained to provide a range of both pharmacological and psychological interventions. However, data from psychiatric practice networks and from epidemiological surveys indicate that there has been a growing emphasis on pharmacotherapy interventions 20 , albeit with some exceptions 21 . Furthermore, the number of psychiatrists varies considerably from country to country, and from region to region within any particular country 22 . While primary care practitioners are also trained to deliver mental health treatments, and indeed provide the bulk of prescriptions for mental disorders in some regions, there is considerable evidence of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of such conditions in primary care settings.

Indeed, despite the development of a range of evidence‐based pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies in the last several decades, current data point to both a treatment gap and a research‐practice gap in mental health. The treatment gap refers to findings that, across the globe, many individuals with mental disorders do not have access to mental health care 23 . The research‐practice gap, also known as the “science‐practice” or “evidence‐practice gap”, refers to differences between treatments delivered in standard care and those supported by scientific evidence 24 . In particular, clinical practitioners have been criticized for employing an eclectic approach to choosing interventions, for not sufficiently adhering to evidence‐based clinical guidelines, and for not employing measurement‐based care.

The treatment gap and the research‐practice gap are of deep concern, given evidence of underdiagnosis and undertreatment, of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment, and of inadequate quality of treatment 25 , 26 . There are, however, some justifiable reasons for a gap between practice and research, including that the evidence base is relatively sparse for the management of treatment‐refractory and comorbid conditions, the relative lack of pragmatic “real‐world” research trials in psychiatry, and the possibly modest positive impact of guideline implementation on patient outcomes 27 , 28 . Indeed, several scholars have emphasized that including clinical experience and addressing patient values are key components of appropriate decision‐making 27 , 29 .

Considerably more research is needed to inform our knowledge of current psychiatric practice and its outcomes. Data from psychiatric practice networks have been useful in providing fine‐grained information in some settings, but much further work is warranted along these lines 30 . Data from randomized controlled trials indicate that psychiatric treatments are as effective as those in other areas of health care, but further evidence should be acquired using pragmatic designs in real‐world contexts 31 . Epidemiological data from across the globe suggest that individuals with mental disorders who received specialized, multi‐sector care are more likely than other patients to report being helped “a lot”, but there is an ongoing need for more accurate estimates of effective treatment coverage globally 32 .

In the interim, evidence of the treatment gap and the research‐practice gap in current mental health services has given impetus to the development of a number of novel diagnostic and treatment models and approaches, ranging from clinical neuroscience through to global mental health. Some of these models and approaches have achieved particular prominence in recent times, with proponents arguing that they will significantly impact psychiatric practice and research in the future. At times advocates for these perspectives and proposals have limited aims, while at other times they speak of paradigm shifts that will drastically alter or wholly reshape current clinical practices 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . We next consider a number of these perspectives and proposals in turn.

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCE AND PERSONALIZED PHARMACOTHERAPY

A key shift in 20th century psychiatry, at least in some parts of the world, was from psychoanalytic to biological psychiatry. The serendipitous discovery of a range of psychiatric medications in the mid‐20th century, and advances in molecular, genetic and neuroimaging methods, propelled this shift. More recently, terms such as clinical neuroscience, translational psychiatry, precision psychiatry, and personalized psychiatry have emerged, helping to articulate the conceptual foundations for a proposed psychiatric perspective aiming to replace or significantly augment current practice 37 , 38 , 39 .

The proposed paradigm of clinical neuroscience rests in part on a critique of current standard approaches. First, in terms of diagnosis, it has been argued that the DSM and ICD constructs are not sufficiently based on neuroscience 40 . Thus, for example, particular symptoms, which may involve quite specific neurobiological mechanisms, may be present across different diagnoses. Conversely, research findings demonstrate that there is considerable overlap of genetic architecture across different DSM and ICD mental disorders 41 . If current diagnostic constructs are not natural kinds, then arguably attempts to find specific biomarkers and develop targeted treatments for them are doomed to fail 42 , 43 .

The proposed new paradigm views psychiatry as a clinical neuroscience, which should rest on a firm foundation of neurobiological knowledge 44 . With advances in neurobiology, we will be better able to target relevant mechanisms and develop specific treatments for mental disorders. Neuroimaging and genomic research offer opportunities for personalizing psychiatric intervention: those with specific genetic variants may require tailoring of psychopharmacological intervention, while particular alterations in neural signatures may be used to choose a therapeutic modality or to alter parameters for neurostimulation.

The RDoC project, developed by the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), has provided an influential conceptual framework for this proposed new paradigm 8 . Whereas the DSM‐III relied on the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) in order to operationalize mental disorders, the RDoC project emphasizes domains of functioning that are underpinned by specific neurobiological mechanisms. Disruptions in these domains may lead to various symptoms and impairments. Domains of functioning are found across species, and their neurobiological substrates are sufficiently known to allow translational neuroscience, or productive movement from bench to bedside and back. Each domain of functioning can be assessed with specific laboratory paradigms.

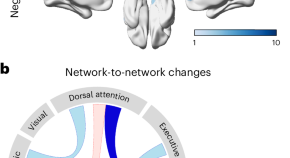

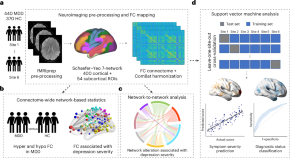

The RDoC matrix initially included five domains of functioning and several “units of analysis” for assessing these domains (see Figure 1 ) 45 . Each domain in turn comprises a number of different “constructs” (or rows of the matrix): these were included on the basis of evidence that they entail a validated behavioral function, and that a neural circuit or system implements the function. Different “units of analysis” (or columns of the matrix) can be used to assess each construct: the center column refers to brain circuitry, with three columns to the left focusing on the genes, molecules and cells that comprise circuits, and three columns to the right focusing on circuit outputs (behavior, physiological responses, and verbal reports). A column to list paradigms is also included.

The Research Domain Criteria matrix (from Cuthbert 45 )

The RDoC matrix is intended to include two further critical dimensions for integrating neuroscience and psychopathology, i.e. developmental trajectories and environmental effects 45 . Thus, from an RDoC perspective, many mental illnesses can be viewed as neurodevelopmental disorders, with maturation of the nervous system interacting with a range of external influences from the time of conception. Several key “pillars” of the RDoC framework, including its translational and dimensional focuses 8 , have been emphasized.

Anxiety, for example, can be studied in laboratory paradigms, and ranges from normal responses to threat through to pathological conditions. Indeed, a clinical neuroscience approach has contributed to the reconceptualization of several anxiety and related disorders 46 , 47 , 48 and to the introduction of novel therapeutic approaches for these conditions 49 . Further, work on stressors has usefully emphasized that environmental exposures become biologically embedded, with early adversity associated to alterations in both body and brain that occur irrespective of the DSM diagnostic category 50 , 51 .

The NIMH has linked the RDoC to funding applications, and this framework has given impetus to a range of clinical neuroscience research. Translational research will certainly advance our empirical knowledge of the neurobiology of behavior and of psychopathology. The RDoC has also prompted conceptual work related to the neurobiology of mental disorders, and the development of measures and methods. Indeed, to the extent that constructs in the RDoC matrix have validity as behavioral functions, and map onto specific biological systems such as brain circuits, the project summarizes key advances in the field, and provides useful guidance for ongoing research.

At the same time, it is relevant to note important limitations of the RDoC approach. First, the RDoC seems less an entirely new paradigm than a re‐articulation of existing ideas in biological psychiatry. Certainly, the importance of cross‐diagnostic neurobiological investigations of domains of functioning has long been emphasized 52 . Second, the neurobiology of any particular RDoC construct, such as social communication, may be enormously complex, so that alternative approaches to delineating the mechanisms involved in particular mental disorders may provide greater traction 53 . Third, methods used to measure domains in the RDoC framework may not be readily available to clinicians. The further one moves from academic centers to the practice of psychiatry in primary care settings around the globe, the less relevant an RDoC framework may be to daily clinical work.

Personalized and precision psychiatry are important aspirations of clinical neuroscience. The notion that psychiatric interventions need to be rigorously tailored to each individual patient makes good sense, given the substantial inter‐individual variability in the genome and exposome of those suffering from psychiatric disorders, as well as the considerable variation in response to current psychiatric interventions. With advances in genomic methods and findings, and the possibility that whole genome sequencing will become a standard clinical tool, with polygenic risk scores readily available, it is particularly relevant to consider the application of genomics to optimizing pharmacological and other treatments 54 .

The Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has already provided a range of clinical guidelines for drugs used in psychiatry. For example, a CPIC guideline recommends that, given the association between the HLA‐B*15:02 variant and Stevens‐Johnson syndrome as well as toxic epidermal necrolysis after exposure to carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, these drugs should be avoided in patients who are HLA‐B*15:02 positive and carbamazepine‐ or oxcarbazepine‐naïve 55 . The evidence base that pharmacogenomic testing improves outcomes is gradually beginning to accumulate, and recent guidelines have started to recommend a number of specific tests 56 .

From an RDoC perspective, particular domains of functioning involve specific neural circuits, which are in turn modulated by a range of molecular pathways. One notable recent development in these fields has been a focus on “big data”. Large collaborations in basic and clinical sciences have been established, which provide sufficient statistical power to advance the field in important ways.

Examples of such “big data” collaborations are the Enhancing Neuroimaging Meta‐analysis Consortium (ENIGMA) 57 , which includes tens of thousands of scans from across the world, and the Psychiatric Genetics Consortium (PGC) 58 , which includes hundreds of thousands of DNA samples from across the globe. The work of ENIGMA and PGC has been at the cutting edge of scientific research in psychiatry, and has provided crucial insights into mental disorders. Certain biological pathways, such as immune and metabolic systems, appear to play a role across different mental disorders, and genomic methods have contributed to delineating causal and modifiable mechanisms underlying these conditions 58 , 59 . At the same time, it must be acknowledged that to date few findings from this work have been successfully translated into daily clinical practice 36 , 54 , 60 .

In summary, clinical neuroscience provides an important conceptual framework that may generate some useful clinical insights, and that may be particularly helpful in guiding clinical research. This framework has contributed to the reconceptualization of a number of mental disorders, and has on occasion contributed to the introduction of new therapies 61 . As clinical neuroscience generates new evidence, this may be incorporated in nosological systems in the future. There are already good arguments for including advances in this area in the curriculum of psychiatric training, and for updating clinicians on progress in the field 62 .

At the same time, there are currently few biomarkers with clinical utility in psychiatry, and methods such as functional neuroimaging and genome sequencing, which are key for future advances in frameworks such as the RDoC, are not readily available to or useful for practicing clinicians 63 . The vast majority of clinical neuroscience publications appear to have little link to clinical practice. At best, therefore, we can expect that ongoing advances in clinical neuroscience will contribute to clinical practice via iterative advances in our conceptualization of mental disorders, and via the ongoing introduction of new insights and new molecules that emerge from laboratory studies.

Indeed, the claim that any particular laboratory, neuroimaging or genetic finding will dramatically change clinical practice should raise a red flag. The neurobiology of behaviors and psychopathology is complex, reproducibility of findings is an ongoing important issue, and clinical neuroscience investigations only occasionally impact clinical practice 64 . Indeed, we should be careful not to be over‐optimistic about clinical neuroscience constituting a paradigm shift. Neurobiological research has not to date provided a rich pipeline of accurate biomarkers for mental disorders, nor speedily found new molecular entities that are efficacious for these conditions, and we cannot, for example, expect that the DSM and ICD will be replaced by the RDoC anytime soon.

NOVEL STATISTICAL APPROACHES TO PSYCHIATRIC NOSOLOGY, ASSESSMENT AND RESEARCH

Disease taxonomies are particularly complex, and may not be able to follow historical models of scientific taxonomies, which have defined all elements of a given set. An often‐used example of the latter taxonomies is the periodic table of elements. Another venerable example is Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae and the resulting nomenclature of biological species. The periodic table of elements has the simplicity of small numbers plus the hard and fast rules of chemistry, while the Systema Naturae , despite having to deal with an ever‐expanding number of entities, is arguably based on direct observation of beings. In contrast, a disease taxonomy deals with thousands of unruly entities (versus 118 elements), which cannot be directly observed, apprehended or dissected (as animals or plants can).

Despite these challenges, disease taxonomies have sought to provide a shared, evidence‐based, clinically meaningful, comprehensive classification that is informed by etiology and therapeutics. The notion that underneath the observable syndrome lies a causal entity, that we should investigate and treat, lies at the heart of the practice of medicine 65 . Such “disease entities” have specific characteristics that make them clear and distinct from others (i.e., presentation, etiology, response to intervention), are transparent to the clinician, and are well‐grounded in evidence.

Psychiatry has long faced the challenges of producing a causal nosology that is able to direct treatment 66 . Pinel developed the first comprehensive nosology for people with severe mental disorders, along with moral treatment, the first therapeutic framework of the scientific era 67 . Soon afterward, Kahlbaum, Kraepelin and Bleuler laid a firm groundwork for clinical psychiatry through close observation and systematic documentation of the natural history of severe mental illness. Arguably, Freud further advanced nosology and therapeutics by focusing on a different set of disorders (usually milder but much more prevalent), which he termed neuroses (to highlight their difference from psychoses ), and by developing the concept and practice of psychotherapy. These frameworks gave impetus to subsequent advances in our understanding of and interventions for mental disorders.

Perceptions of insufficiently rapid and robust advances in treatments have led to criticism of current nosology 68 . In particular, the DSM and ICD have been criticized for overly focusing on reliability at the expense of validity. In this view, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may be genuine disease entities, but our syndromic definition lacks specificity, and there are likely different causal pathways that lead to clinically meaningful subtypes of these disorders. Major depressive disorder, on the other hand, is likely to be a hodgepodge of mood syndromes, some non‐dysfunctional (i.e., non‐disorders) or non‐specific (i.e., combining depressive with anxiety symptoms), including only a few true but potentially diverse disease entities (e.g., melancholia, psychotic depression). And when it comes to, say, personality disorders, the disease‐entity concept is even more distant, and the search for new approaches is seen as particularly key.

One such novel paradigm is the HiTOP. This proposes a hierarchical framework that, based on the observed covariation of dimensional traits, is able to identify latent super‐spectra and spectra (supra‐syndromes), syndromes (our current disorders), and lower‐level components 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 . In this conceptual framework, a dimension consists of a continuous space in which an element occurs in differences of degree, but not of kind, between the normal and the pathological.

The HiTOP relies on factor analysis and related techniques, which tap into the covariation of observable traits to identify an unobserved, common factor that, once included in the model, explains the covariation 73 . Costa and McCrae's studies leading to the identification of five personality domains were a prime example of this approach. There is a common underlying reason that explains a person's tendency to worry about many things, think that the future looks bleak, be bothered by intrusive thoughts, and be grouchy 74 . That unobserved factor was conceptualized as “neuroticism”, and fully explains the covariation of these traits in any given individual. A similar approach to the study of childhood psychopathology led to the binary characterization of an “internalizing” and an “externalizing” dimension to childhood disorders 75 .

The HiTOP paradigm seeks to leverage these well‐established lines of research to develop a data‐driven nosology that is free from the theory‐driven dead weight built into current approaches. The key conceptual departure relies on the premise that, since evidence points towards psychopathological dimensions existing on a continuum, disorders should be similarly conceptualized, and nosology should move away from a focus on categorical entities. Instead of insisting on questionable boundaries, this approach proposes dimensional thresholds, which are empirically determined and do not involve any difference “in kind”. By grouping co‐occurring symptoms within the same syndrome, and non‐co‐occurring symptoms separately, within‐disorder heterogeneity is reduced. And by assigning overlapping syndromes to the same unobserved spectra, excess comorbidity found when using current categories is explained.

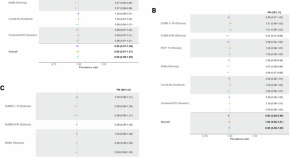

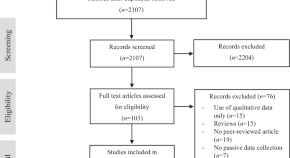

The resulting dimensional classification, the proponents of HiTOP argue, is consistent with evidence on risk factors, biomarkers, course of illness, and treatment response 69 . Figure 2 shows a schema of the proposed new nosology. An intriguing element of this approach is what has been termed “p”, or general psychopathology factor (at the top of Figure 2 ). In addition to super‐spectra and spectra, factor analysis ultimately points towards the existence of a single latent trait that would explain all psychopathology, comparable to the well‐established “g” factor for general intelligence 76 , 77 .

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) model (from Krueger et al 69 )

If dimensional nosologies seek to overturn categorical ones, network analysis arguably aims to overturn both, insofar as it posits that the notion of an unobserved underlying construct is unwarranted, be it a categorical disease entity or a dimensional latent factor 78 . The network approach to psychopathology holds that mental disorders can be conceived as “problems in living”, and are best understood at the level of what is observable. Rather than by latent entities, disordered states are fully explained by the interaction between signs and symptoms (the “nodes” of the networks). These interactions are themselves the causal elements (i.e., a symptom causes another symptom, then another symptom, and so on), and a disorder is simply an alternative “stable state” of strongly connected symptom networks (as opposed to the “normal” steady state of health).

A conceptualization of disorders as “problems in living” does away with the medical notion of a disease as an underlying causal entity. In this view, deficiencies in our understanding of etiology are not necessarily due to diagnostic limitations or insufficiently accurate models for the unobserved but, on the contrary, may be due to our lack of attention to the surface, i.e. the symptoms themselves, which go about reinforcing each other while we are distracted by peeking behind imaginary curtains.

Unlike dimensional approaches, proponents of network analysis disavow any nosological hierarchy (super‐spectra, spectra, disorders, symptoms, etc.), and posit that there is only one level, that of symptoms, which can all cause and reinforce one another. Of note, network analysis posits that symptoms (or interacting nodes) can be activated by disturbances emerging from the “external field” (i.e., “external” to the symptom network, not necessarily to the body or person), such as the loss of a loved one (which may activate the symptom depressed mood, setting in motion the depressive network) or a brain abnormality (which may activate the symptom hallucination, setting in motion the psychotic network).

Whether an individual develops a new strongly connected network of symptoms in the face of a stressor depends on his/her “vulnerability”, which is based on the network's connectivity. Given a dataset with symptoms and/or signs for disorders, a network analysis can quantify all relevant nodes and interactions, including the frequency and co‐occurrence of symptoms, the strength and number of their associations, and the centrality of each symptom (i.e., the sum of the interactions with other nodes). Empirical work using network analysis potentially provides rigorous accounts of vulnerability to and evolution of mental disorders.

A number of other novel statistical approaches have also been put forward as potentially facilitating paradigm shifts in psychiatry. Psychiatry has long relied on linear models to explore associations and develop theories of risk and resilience for mental disorders. However, causal inference methods have now been developed in statistics, and provide new approaches to delineating causal relationships 79 . In genetics, Mendelian randomization provides an innovative method for addressing the causal relationships of different phenotypes, and has increasingly been employed in psychiatric research 80 . Neural networks and deep learning have played a key role in advancing artificial intelligence, and are increasingly being applied to the investigation of psychiatric disorders, including prediction of treatment outcomes 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 . While many view such techniques as allowing iterative advances, some are persuaded that they allow an entirely novel perspective and so constitute a paradigm shift in the field 85 .

Work on the HiTOP and network analysis has been important and useful in a number of respects. First, unbiased data‐driven approaches have an important role in strengthening the relevant science, whether of nosology, or of areas such as genetics. A focus on fear‐related anxiety disorders, for example, offers interesting avenues for research, both from a neuroscience and a therapeutic perspective, and network analysis has contributed insights into the presentation of some disorders 48 . Second, some dimensional constructs, including those of internalizing and externalizing disorders, have clinical utility. The “distress” subfactor reflects the notable overlap between depressive and anxious symptoms, and the association between symptoms from two different disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) may be stronger than associations “within” each disorder 86 . Third, the use of novel statistical methods to draw causal inferences has provided important insights into risk for and resilience to mental disorders 59 . For instance, network analysis offers a nuanced foundation for targeted treatment of the core symptoms of some mental disorders (e.g., reframing specific automatic thoughts through cognitive‐behavioral interventions).

At the same time, such approaches have important limitations. Notably, categorical and dimensional approaches are interchangeable: any dimension can be converted into a category, and any category can be converted into a dimension 87 . There is no reason to conceptualize mental disorders as exclusively dimensional. In physics, matter itself is sometimes better conceived in terms of waves (a dimensional concept) and other times in terms of particles (a categorical one). Similarly, in psychiatry, a pluralist approach that allows the employment of a range of different dichotomous and continuous constructs seems appropriate 88 , 89 .

Remarkably, the HiTOP employs DSM terminology at the disorder level. “Number‐driven” psychopathologies and their resulting nosologies may not necessarily lead to a shift in constructs grounded in long‐standing clinical practice and research. In the same vein, network analysis offers a useful model to understand the distribution of symptoms, identify therapeutic targets, and explain the effectiveness of symptomatic interventions. However, network analysis does not specify the particular levels of explanation that underlie a network structure; so, while it may be a useful organizing framework, it is unclear that it will provide novel insights into underlying etiological mechanisms.

Consider a set of patients presenting with the following symptoms, among others: headaches, vomiting and seizures. A factor analysis may point towards a latent factor explaining the covariation among them. Any clinician will know that, unless the cause is substance‐related, the first thing to rule out in these patients is a space‐occupying lesion in the brain, and that this unobserved element is only an intermediary that can itself be caused by multiple disease entities, most notably hemorrhage, infection and cancer. The fact that a latent factor may explain the covariation between anxious and depressive symptoms does not exclude that these symptoms are in fact caused by very different dysfunctions (upstream of the latent factor), and that other accompanying symptoms will hold the clue to the ultimate cause (just as high blood pressure, fever or weight loss would hold clues for a space‐occupying lesion syndrome).

Relatedly, consider the focus of the HiTOP on a general psychopathology factor “p”. This focus can be countered by a reductio ad absurdum argument suggesting that a latent factor “i” explains the covariation of any and all human illnesses. Given some datasets, we may find that the covariation of nausea, hemoptysis, jaundice and myocardial infarction is explained by a latent dimensional trait. We may choose to call this “sybaritism”, dimensionally distributed between one extreme (temperance) and another (debauchery). Readers who focus on values‐based medicine might well criticize the choice of words here, while those focused on evidence‐based medicine are unlikely to be persuaded that an approach that elides disease entities will advance studies of psychiatry, gastroenterology and cardiology 29 .

In a latent class analysis of depressive and anxious syndromes, Eaton et al 90 proposed an approach called “guided empiricism”, whereby they explicitly imposed a theory‐driven structure on various statistical models, compared them, and obtained the best empirical fit. Perhaps using such explicitly theory‐driven constraints is preferable to accepting hidden theoretical constructs. For example, rather than assuming that all the DSM depressive and some anxiety/stress related disorders are explained by a latent factor called “distress”, itself under a spectrum called “internalizing disorders”, a theory‐grounded structure can be imposed on the models to try to identify what is driving the overlap. Indeed, it should be emphasized that purportedly “number‐driven” nosologies all have built‐in qualitative components: from the questions in the scales used to measure traits, to the labels chosen for the latent factors, these classifications are theory‐laden.

In summary, the solution to nosologic challenges in psychiatry may not reside in the building of new nosologies or psychopathologies from scratch 91 , nor in the banishment of the “disease entity” concept, but rather in continuing the humble, laborious, iterative work of systematic clinical observation, painstaking research, and creative thinking, while purposefully comparing dimensional, categorical and hybrid models applied to the same datasets. The claim that a “quantitative” nosology is somehow “atheoretical” raises a red flag: where theory is seemingly absent, it is often hidden. Instead, we need thoughtful and explicit combinations of theories grounded on clinical practice and confirmatory quantitative evidence. Hypothesis formulation is a qualitative, creative, theory‐laden endeavour, while quantitative research helps us discard false theories and refine what we know (by proving hypotheses wrong or quantifying associations).

Similarly, etiological and treatment challenges in psychiatry are unlikely to be addressed merely by the employment of larger and larger datasets, using more and more sophisticated statistical methods. Certainly, big data consortia and sophisticated statistical analyses have yielded valuable insights into the nature of psychiatric disorders. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of any empirical dataset and any analytic method, as well as the value of a wide range of complementary research designs and statistical approaches – including the age‐old single‐case study, which may sometimes provide clinical insights that outweigh those from big data analyses 92 .

Indeed, the claim that a new statistical, bioinformatic or computational method will provide entirely novel insights that enable a paradigm shift in psychiatry should again raise a red flag. Furthermore, where solutions reside within a black box, there is ongoing uncertainty about the extent to which they will be able to provide clinically useful assistance 93 , 94 . Thoughtful and explicit combinations of existing and novel research designs and statistical methods should be employed, with the aim of achieving iterative and integrative progress in our diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION AND COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH CARE

The last 70 years have seen a seismic shift in models of mental health care delivery around the world. The first half of the 20th century was dominated by the growth of psychiatric hospitals, particularly in high‐income Western countries. By 1955, there were 558,239 severely mentally ill people living in psychiatric hospitals in the US, with a total population of 164 million at the time 95 . In the years that followed, there was a significant reduction in psychiatric hospital bed numbers in many high‐income countries, as part of a trend that came to be known as deinstitutionalization. In the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand and countries in Western Europe, there was an 80‐90% reduction in psychiatric hospital beds between the mid‐1950s and the 1990s 96 .

Deinstitutionalization refers to the downscaling of large psychiatric institutions and the transition of patients into community‐based care. This is said to include three components: the discharge of people residing in psychiatric hospitals to care in the community, the diversion of new admissions to alternative facilities, and the development of new community‐based specialized services for those in need 97 . More recently, a focus in community‐based care has also been the development of models for integrating mental health into primary care, as well as of shared decision‐making and recovery approaches 98 . To the extent that these models propose new ways of addressing mental illness, as well as extensive scale‐up of community‐based services, many would argue that they constitute a crucial paradigm shift.

Deinstitutionalization was driven by three main forces. First, the introduction of new medications made it increasingly possible for people with severe and enduring mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder to live reasonably well in community settings. Second, the mushrooming of psychiatric hospitals had come with high costs, and deinstitutionalization was seen by many governments as a cost‐saving strategy. Third, the growth of the human rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s generated increasing public concern about practices in psychiatric institutions, including involuntary care. Films such as One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest drew public attention to the conditions in those facilities and provided support to the idea that people living with mental disorders should have a choice over the nature and locus of their care. This trend was reinforced by research demonstrating that community‐based models of care, including for people with severe mental disorders, could be delivered effectively, in a manner that was more acceptable to service users, and in some cases less costly 97 .

However, in many regions of the world, these developments have not actually occurred. Particularly in many post‐colonial low‐income countries, for example in sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia, large psychiatric hospitals have been left behind by departing administrations, and have remained the main locus of care. In these countries, there has been little substantial deinstitutionalization, and very limited scaling up of community‐based and primary care mental health services 22 . In low‐income countries, there were 0.02 psychiatric beds per 100,000 population in 2001, and this increased to 1.9 beds per 100,000 population in 2020.

The success of deinstitutionalization programmes in transitioning to community‐based care has been highly varied around the world. In some countries, such as Italy, legislation has mandated the establishment of community‐based services, and consequently these services have been widely implemented, although with substantial variation across the country 99 . In many other countries, funding did not follow people who were discharged from psychiatric hospitals into community settings. For example, in many parts of the US, deinstitutionalization has been associated with a burgeoning population of homeless mentally ill and mentally ill prisoners 95 .

In Central and Eastern Europe, even with recent reforms, studies have criticized the uneven pace of deinstitutionalization, the lack of investment in community‐based care, and the “reinstitutionalization” of many people with severe mental illness or intellectual disability 100 . In a tragic case in South Africa, deinstitutionalization of 2,000 people with severe mental illness or intellectual disability from the Life Esidimeni facility into unlicensed and unregulated community organizations led to the death of over 140 people, sparking a public outcry and a national enquiry by the Human Rights Commission 101 .

Importantly, deinstitutionalization has been associated with “revolving door” patterns of care, in which people are discharged from hospital after admission for an acute episode, but do not have adequate care and support in the community, and therefore relapse and need to be readmitted. Indeed, readmission rates have been an important indicator for service managers to monitor in the post‐deinstitutionalization era, and the focus of several intervention studies 102 .

The WHO has advocated for the development of community‐based services for mental disorders for many decades. In the early 2000s, it produced a set of guidelines for countries to develop national mental health policies, plans and services 103 . This included the now widely cited “optimal mix of services” to guide countries on how to balance hospital‐ and community‐based care. This model proposed a pyramid structure, in which specialist psychiatric inpatient care represents only a small proportion of services at the apex of the pyramid, and is supported by psychiatric services in general hospitals, specialist community outreach, primary care services, and self‐care at the base of the pyramid. Others have developed similar “balanced care” models 104 .

The 21st century has also seen the development of models for integrating mental health into primary care, such as collaborative care models 105 . These latter initially focused on managing people with comorbid depression and other chronic diseases. Subsequently this work has been expanded to include other mental disorders, through models in which a mental health specialist provides support to non‐specialist health care providers, who are the main point of contact for people needing care. The WHO has endorsed this approach, particularly through its flagship mhGAP programme, which provides clinical guidelines for the delivery of mental health care through non‐specialist health care platforms in primary care and general hospital settings 106 . The mhGAP Intervention Guide has now been implemented in over 100 countries.

In parallel, the latter part of the 20th century and early 21st century have seen the rapid development of shared decision‐making and recovery approaches to mental health care. Shared decision‐making involves clinicians and people with mental disorders working together to make decisions, particularly about care needs, in a collaborative, mutually respectful manner 98 . This approach is consistent with an emphasis on human rights, as well as on the importance of patients’ lived experience, explanatory models and specific values, and clearly deserves support 107 , 108 . Recovery models have challenged traditional roles of “patients” to reframe recovery as a way of living a satisfying, hopeful life that makes a contribution even within the limitations of illness 109 . The recovery movement has been highly influential, is now incorporated into mental health policies, and has shaped the design of mental health systems in several countries 109 .

Yet, despite the strong scientific and ethical principles supporting community‐based care, collaborative care and moves towards shared decision‐making and recovery approaches, there remain major challenges, and the proposed paradigm shift remains to a large extent aspirational. While community care models have been developed, tested and shown to be effective in landmark studies, there are few cases of countries systematically investing in these models at scale, in a manner that substantially influences the mental health of populations. In addition, although there are apparent advantages to approaches such as shared decision‐making, a wide range of barriers across individual, organizational and system levels have been reported 110 , and implementation remains limited in mental health care 98 .

Indeed, it has been noticed that the agreement about the concept of shared decision‐making among stakeholders is only superficial 98 . After all, clinicians may not support this approach if it leads to patients being more empowered, but less adherent to treatment recommendations. This example raises broader questions about community‐based care models: is the failure to systematically scale up these models just due to a lack of political will and related scarcity of resources, or are there fundamental concerns with the model? Our view is that both of these may be true.

There is certainly a lack of political will and investment. Despite the courageous campaigning by people with lived experience for their rights to make decisions about their care, together with the robust evidence of improved outcomes associated with community‐based collaborative care models, governments often remain indifferent 1 . In 2020, 70% of total government expenditure on mental health in middle‐income countries was allocated to mental hospitals, compared to 35% in high‐income countries 22 . These differences need to be viewed in the context of massive global inequities in governments’ commitments to mental health more broadly. While high‐income countries spend US$ 52.7 per capita on mental health, low‐income countries spend US$ 0.08 per capita 22 .

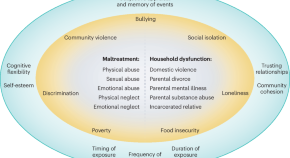

On the other hand, it may also be the case that community‐based care does not go far enough in addressing the social determinants of mental health. While many community‐based care models focus on individuals with a mental disorder and their immediate family, very few address the fundamental structural drivers of mental illness in populations, such as inequality, poverty, food insecurity, violence, and hazardous living conditions 111 , 112 . Successful community‐based mental health services arguably require the existence of viable communities.

The strategy of deinstitutionalization was founded on the premise that communities can provide a safe, supportive environment in which people with severe mental illness can thrive. In countries marked by high levels of poverty, inequality, civil conflict and domestic violence, this is certainly not the case. Advocating for community‐based care requires addressing the fundamental social injustices which precipitate and sustain mental illness in populations.

Furthermore, community‐based service planners may have not gone far enough in considering demand‐side drivers of mental health care. For example, in many low‐ and middle‐income countries, traditional and faith‐based healers continue to be major providers of care for people with severe mental disorders, due to the scarcity of mainstream mental health professionals, and shared beliefs about the causes and treatments of such conditions.

The effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of collaborative shared care models with traditional and faith‐based healers has been documented in Ghana and Nigeria 113 . Similarly, the possibility of addressing demand‐side barriers by implementing a community informant detection tool, based on local idioms of distress and vignettes to identify people with various mental health conditions, has been demonstrated in Nepal 114 . These innovations from low‐ and middle‐income countries provide potential lessons for high‐income countries in developing collaborative care models that are aligned with the belief systems of mental health care users and address demand‐side barriers to care.

In summary, despite the development of community‐based services, collaborative care, shared decision‐making and recovery models, a paradigm shift towards the implementation of well‐functioning and effective community mental health care around the globe has not occurred. A red flag should be raised when plans for community‐based services are under‐resourced (for example, not providing sufficient human resources to do the work), or are over‐optimistic about implementation (for example, overlooking important barriers to shared decision‐making) 115 .

Nevertheless, community‐based models have many strengths, and should be incorporated into attempts to iteratively improve clinical practices and society responses to mental disorder. Indeed, it has been argued that the shift to community‐based services has not been a sudden change, but rather the culmination of a slow, gradual, evolutionary development, which has old historical roots and will hopefully continue over time 116 . Efforts to strengthen community‐based approaches around the world are needed to consolidate and extend the advances that have been achieved.

Taken together, the slow transition from institutional to community‐based mental health care is partly attributable to the failure of governments in low‐, middle‐ and high‐income countries to adequately invest in such care – to mandate the funding to follow people with mental disorders into their communities and provide them with the support and choices they need to live productive meaningful lives – and strategies are needed to persuade them to do so. But, perhaps to an equally important degree, there are shortcomings in models of community care, with unrealistic expectations of a dramatic paradigm shift.

CBT AND THE SCALE‐UP OF EVIDENCE‐BASED PSYCHOTHERAPY

Since its development in the 1970s, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been at the core of an important shift in clinical practice towards the use of evidence‐based psychotherapies. Hundreds of randomized controlled trials have examined the effects of CBT for a wide range of mental disorders, including depression, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, and also other conditions, such as anger and aggression, chronic pain, and fatigue 117 . CBT has also been tested across age groups and specific target groups, such as women with perinatal conditions and people with general medical disorders 117 .

Several other types of psychotherapy have also been rigorously investigated, and even psychotherapies that had not traditionally been explored using randomized controlled trials, such as psychoanalytically oriented therapies and experiential therapies, have now also been tested using such methods 118 , 119 , 120 . Nevertheless, CBT is by far the best examined type of psychotherapy and therefore dominates the transition of the field towards the use of evidence‐based psychotherapies 121 .

CBT is highly consistent with a neurobiological model of mental disorders, insofar as it focuses on symptom reduction, improvement in functioning, and remission of the disorder. Furthermore, the literature on the neurobiological bases of behavioral and cognitive interventions has become increasingly sophisticated 122 , 123 , and a more recent literature on process‐based CBT aligns well with the focus of RDoC on transdiagnostic mechanisms 124 . CBT can therefore be readily combined with neurobiologically oriented approaches, especially pharmacotherapy.

However, despite the strength of the evidence and its compatibility with other evidence‐based interventions, CBT has not been integrated into mental health systems globally. In many countries, it is still often seen as a reductionist approach that does not tackle the real underlying problems. Psychoanalytic approaches remain dominant, for example, in France and in Latin America 125 .

In low‐ and middle‐income countries, psychotherapies in general are often not available for people suffering from mental disorders, due to lack of resources and trained clinicians. Even in high‐income countries such as the US, the uptake of psychotherapies has declined since the 1990s 20 , while the use of antidepressant medication has increased considerably 126 , despite the fact that most patients prefer psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy 127 .

In most treatment guidelines, CBT is recommended as a first‐line treatment for several mental disorders. However, the actual implementation of such guidelines in routine care has been consistently shown to be suboptimal 128 , 129 , 130 . In addition, when CBT is employed, it is unclear whether therapists actually use it as detailed in standardized treatment protocols, or whether they combine it with other approaches.

The Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program in the UK represents the most ambitious attempt to address the barriers faced by evidence‐based psychotherapy, with scaling up of CBT across an entire country. The main goal of the program was to massively increase accessibility to evidence‐based psychotherapies for individuals suffering from common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders.

An important argument for massively scaling up evidence‐based therapies was economic. Depression and anxiety disorders often start during the working age, and therefore the economic costs associated with them are large, due to production losses and costs of welfare benefits. If these conditions are treated timeously, costs of treatment are balanced by increased productivity and reduced welfare costs 131 . A global return on investment analysis confirmed this assumption cross‐nationally, indicating that every invested US dollar would result in a benefit of 2.3 to 3 dollars when only economic costs are considered, and 3.3 to 5.7 dollars when the value of health returns is included 132 . Hence, the hope was that IAPT would pay for itself.

The IAPT model has a number of key features 133 . First, patients can be referred by a general practitioner or another health professional, but can also be self‐referred. People with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, mixed anxiety/depression, social anxiety disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive‐compulsive disorder, and health anxiety receive a person‐centered assessment that identifies the key problems, and an agreed‐upon course of treatment is defined 131 .

Second, IAPT works according to a stepped‐care model. Patients are first treated with an evidence‐based low‐intensity intervention, typically a self‐help intervention based on CBT. Only if this is not appropriate or patients do not recover, they receive a high‐intensity psychological treatment. Low‐intensity therapies are delivered by “psychological well‐being practitioners” who are trained to deliver guided self‐help interventions, either digitally, by telephone, or face to face. High‐intensity therapies are delivered by therapists who are fully trained in CBT or other evidence‐based interventions.

Third, the therapies offered by IAPT are those recommended by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). When the NICE recommends different therapies for a mental disorder, patients are offered a choice of which therapy they prefer. This means that IAPT does not only deliver CBT, although a recurring criticism has been that the program is overly focused on that type of psychotherapy.

Fourth, outcome data are routinely collected in IAPT. Patients are asked to fill in various validated questionnaires before each session, so that clinicians can review the outcomes and use them in treatment planning.

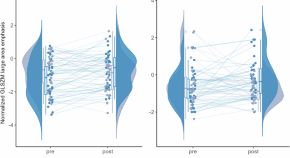

Between April 1, 2019 and March 31, 2020, 1.69 million patients were referred to IAPT, of whom 1.17 million started treatment, with 606 thousand completing treatment, and 51% of them reporting recovery. The proportion of those recovered, however, is substantially lower (26%) when it is calculated based on those who started treatment (assuming that dropouts did not recover), and it has been argued that IAPT outcomes have been reported in an overly positive way 134 , 135 .

An important issue is that the outcomes vary considerably across IAPT services. In 2015/2016, the lowest recovery rate was 21% and the highest was 63%. There is some evidence that recovery rates are higher with an increasing number of sessions and more patients stepping up to more intensive therapy 136 . Other variables that are associated with better outcomes include shorter waiting times, lower number of missed appointments, and a greater proportion of patients who go on with treatment after assessment 137 .

A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of the IAPT program identified 60 open studies, of which 47 could be used to pool pre‐post outcome data 138 . Large pre‐post treatment effect sizes were found for depression (d=0.87, 95% CI: 0.78‐0.96) and anxiety (d=0.88, 95% CI: 0.79‐0.97), and a moderate effect for functional impairment (d=0.55, 95% CI: 0.48‐0.61).

The IAPT program arguably represents the state‐of‐the‐art for implementation of evidence‐based psychotherapy in routine clinical care. Indeed, it has served as a model for the development of similar programs in other countries 138 , including Australia 139 , Canada 140 , Norway 141 , and Japan 142 . More broadly, IAPT indicates recognition of the importance of mental health and of the allocation of sufficient resources to treatment of mental disorders, as well as acknowledgement of the importance of psychotherapies and their role in addressing mental disorders.

There are other large scale implementation programs of CBT, especially in digital mental health care. For example, MoodGYM 143 , an online CBT program for depression, had acquired over 850,000 users by 2015. Psychological task‐sharing interventions developed by the WHO, especially Problem Management Plus, have been tested in several randomized trials and are now being implemented in low‐ and middle‐income countries on a broad scale 144 , 145 . However, the IAPT program is still the largest systematic implementation program of psychotherapies across the world.

Given the ambitiousness of IAPT, with extensive and rigorous roll‐out across an entire country, it seems reasonable to raise the key question of whether this program has had real‐world impacts, including a reduction in the disease burden of mental disorders. A first issue, however, is that comparison of IAPT with other treatment services would require a community intervention trial in which people are randomized to either IAPT or “regular” mental health care. Such a trial has not been conducted and probably never will be. Thus, although it is possible to claim on the basis of outcome data from routine care that other services are as effective as IAPT 146 , or that IAPT services may not provide interventions that match the level of complexity of the problems of patients 147 , it is difficult to validate such claims.

A second issue is whether any mental health treatments, including IAPT, are truly capable of reducing the disease burden of mental disorders. A key modeling study has estimated that current treatments only reduce about 13% of the disease burden of mental disorders at a population level 148 . In optimal conditions, in which all those with a mental disorder receive an evidence‐based treatment, this percentage can be increased to 40%. So, even under optimal conditions of 100% uptake and 100% evidence‐based treatments, reduction of disease burden is not expected to be more than 40%. This is true for IAPT as well as other programs disseminated on a broad scale.

The limited ability of current treatments to reduce the disease burden of mental disorders raises the so‐called “treatment‐prevalence paradox” 149 . This refers to the fact that clinical treatment rates have increased in the past decades, while population prevalence rates of mental disorders have not decreased. Increased availability of treatments could shorten episodes, prevent relapses, and reduce recurrences, in turn leading to lower point prevalence estimates of depression, but this has not transpired. Most meta‐analyses indicate stable prevalence rates or even small increases in prevalence, despite increased uptake of services 150 and the demonstrated efficacy of psychiatric treatments 31 .

There are several possible explanations for this “treatment‐prevalence paradox” 149 . First, it is possible that prevalence rates of depression have dropped, but that at the same time incidence has increased due to societal changes. Second, it is possible that prevalence rates have dropped, but that emotional distress has been more often diagnosed as a depressive disorder over the past decades, thereby masking the drop. Third, it is possible that prevalence rates have not dropped, because treatments may not be as effective as the field would like 151 . Indeed, treatment effects may be overestimated in trials due to publication bias, selective outcome reporting, use of inappropriate control groups, or the allegiance effect. Moreover, treatments may not benefit chronic depressive patients, or treatments may have iatrogenic effects that block natural recovery and prolong depressive episodes 152 .

Taken together, the development of evidence‐based psychotherapies has been a remarkable step forward for psychiatry, and the scale‐up of such effective psychotherapies in IAPT and other large‐scale implementation programs has contributed to consolidating this advancement. That said, the several criticisms of IAPT suggest that it is by no means a panacea. Instead, the implementation of evidence‐based psychotherapies is arguably best conceptualized as representing incremental progress. The impact of evidence‐based treatments on the disease burden of mental disorders currently appears to be modest; and the time horizons for introduction of interventions that are notably more successful is unclear.

DIGITAL PHENOTYPING AND DIGITAL THERAPIES

Rapid technological advances and the expansion of the Internet have spurred the development and widespread use of a host of digital devices with the potential to transform psychiatric research and practice 153 . Indeed, the fourth industrial revolution and the nudge towards telepsychiatry by the COVID‐19 pandemic have already revealed that digital technologies provide novel opportunities to improve psychiatric diagnosis, expand the delivery of mental health care, and collect large quantities of data for psychiatric research 154 , 155 .

There are many examples of how these advances have enabled digital solutions in psychiatry 156 , 157 . To name a few, virtual reality can facilitate exposure therapy for phobias and PTSD 158 , chatbots can deliver remote CBT anonymously day‐and‐night 159 , computer analysis of closed circuit television (CCTV) images can identify suicide attempts in progress at suicide hot‐spots 160 , voice and facial recognition software may enhance psychiatric diagnosis 161 , 162 , wearable devices may enable real‐time monitoring and evaluation of patients 163 , analyses of human‐computer interaction may detect manic and depressive episodes in real‐time 164 , and suicide risk may be assessed by analysis of social media posts 165 .

Furthermore, the widespread use of digital medical records, the collection of vast quantities of data from individuals via smart devices, the ability to link multiple databases, and the use of machine learning algorithms have redefined the use of big data in psychiatry with the promise of overcoming the failures of conventional statistical methods and small samples to capture the underlying heterogeneity of psychiatric phenotypes 81 , 82 , 83 . The ability to access, store and manipulate data, together with the use of machine learning algorithms, promises to advance the practice of individualized medicine in psychiatry by allowing matching of patients with the most appropriate therapies 81 , 82 , 83 .

Smartphone use is now ubiquitous even in remote and resource‐constrained environments across the globe 166 , making these devices a powerful medium to improve access to psychiatric care 167 . Smartphones are already being used to deliver interventions for common mental disorders 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 , and more than 10,000 mental health apps are available in the commercial marketplace 172 . There is considerable potential to turn smartphones into cost‐effective and cost‐efficient treatment portals by literally placing mental health interventions in the hands of the 6,378 billion people who own these devices (i.e., 87% of the world's population), many of whom do not currently have access to mental health care.

As communication devices, smartphones can be used to facilitate peer support, deliver personalized messages, provide access to psychoeducational resources, and facilitate timely referrals to appropriate in‐person clinical care 153 . The communication capabilities of smartphones have enabled the expansion of telepsychiatry via high‐quality low‐cost voice and video calls 173 , with evidence indicating that the use of video conferencing is not inferior to in‐person psychiatric consultations 174 .

Because smartphones are equipped with a range of sensors and the ability to store and upload data, they can be easily used to collect real‐time active data (i.e., data which the user deliberately and actively provides in response to prompts). Active data collected via smartphones are already being used in psychiatry for ecological momentary assessments, cognitive assessments, diagnosis, symptom monitoring, and relapse prevention 175 , 176 . Beyond these clinical applications, smartphones are also powerful tools for data collection in psychiatric research 177 , 178 .

Digital devices, including smartphones and wearables, can also collect and store a host of passive data (that is, data generated as a by‐product of using the device for everyday tasks, without the active participation of the user) with near zero marginal costs. These passive data have been likened to fingerprints or digital footprints. They provide objective continuous longitudinal measures of individuals’ moment‐to‐moment behavior in their natural environments and could be used to develop precise and temporally dynamic markers of psychiatric illness, a practice known as digital phenotyping 155 , 179 .

If digital phenotyping delivers on its promises, it will enable continuous inexpensive surveillance of mental disorders in large populations, early identification of at‐risk individuals who can then be nudged to access psychiatric treatment, and early identification of treatment failure to prompt timely individualized treatment decisions 180 . These potential applications are important, given the dearth of accurate real‐time psychiatric surveillance systems in many parts of the world, individuals’ reluctance to seek treatment at the early stages of psychiatric illness, and the high rates of treatment failure which necessitate timely adjustments to management.

Identifying digital markers for mental disorders is, however, not without potential pitfalls, that will need to be mapped and navigated before digital phenotyping can realize its full potential. There are still unanswered questions about the sensitivity, reliability and validity of smartphone sensors for health monitoring and diagnosis 181 . Furthermore, there appears to be a bias in measurement of everyday activities from smartphone sensors, because of variations in how people use their devices 182 . It still remains to be seen if actuarial models developed from population level digital footprints are clinically useful at the level of individual patients, as well as how digital phenotyping can be meaningfully integrated into routine clinical practice, and how patients will respond to and accept passive monitoring of their day‐to‐day activities 180 , 183 .

Digital solutions are not without shortcomings, and a digital intervention is not necessarily better than no intervention 184 , 185 , 186 . Reviews of the quality and efficacy of mental health apps indicate that there is often little evidence to support the effectiveness of direct‐to‐consumer apps 184 , 185 , 186 . Even when mental health apps seem to be useful, data indicate that many of them suffer from high rates of attrition and are not used long enough or consistently enough to be effective 187 .

Concerns about data privacy and security are a significant obstacle to expanding the use of digital technologies in psychiatric practice and research 188 , 189 . Psychiatry is often concerned with deeply personal, sensitive, and potentially embarrassing information, that requires secure data storage and stringent privacy safeguards. The risks associated with collecting and storing digital mental health information need to be clearly articulated in terms that patients understand, so that they can provide informed consent. Privacy policies in digital solutions such as smartphone apps are unfortunately often written in inaccessible language and “legalese”, making them incomprehensible to many users 189 , and there is as yet insufficient regulation of mental health apps and no minimum safety standards 188 .