The Research Whisperer

Just like the thesis whisperer – but with more money, how to make a simple research budget.

Every research project needs a budget*.

If you are applying for funding, you must say what you are planning to spend that funding on. More than that, you need to show how spending that money will help you to answer your research question .

So, developing the budget is the perfect time to plan your project clearly . A good budget shows the assessors that you have thought about your research in detail and, if it is done well, it can serve as a great, convincing overview of the project.

Here are five steps to create a simple budget for your research project.

1. List your activities

Make a list of everything that you plan to do in the project, and who is going to do it.

Take your methodology and turn it into a step-by-step plan. Have you said that you will interview 50 people? Write it on your list.

Are you performing statistical analysis on your sample? Write it down.

Think through the implications of what you are going to do. Do you need to use a Thingatron? Note down that you will need to buy it, install it, and commission it.

What about travel? Write down each trip separately. Be specific. You can’t just go to ‘South East Asia’ to do fieldwork. You need to go to Kuala Lumpur to interview X number of people over Y weeks, then the same again for Singapore and Jakarta.

Your budget list might look like this:

- I’m going to do 10 interviews in Kuala Lumpur; 10 interviews in Singapore; 10 interviews in Jakarta by me.

- I’ll need teaching release for three months for fieldwork.

- I’ll need Flights to KL, Singapore, Jakarta and back to Melbourne.

- I’ll need Accommodation for a month in each place, plus per diem.

- The transcription service will transcribe the 30 interviews.

- I’ll analysis the transcribed results. (No teaching release required – I’ll do it in my meagre research time allowance.)

- I’ll need a Thingatron X32C to do the trials.

- Thing Inc will need to install the Thingatron. (I wonder how long that will take.)

- The research assistant will do three trials a month with the Thingatron.

- I’ll need to hire a research assistant (1 day per week for a year at Level B1.)

- The research assistant will do the statistical analysis of the Thingatron results.

- I’ll do the writing up in my research allowance time.

By the end, you should feel like you have thought through the entire project in detail. You should be able to walk someone else through the project, so grab a critical friend and read the list to them. If they ask questions, write down the answers.

This will help you to get to the level of specificity you need for the next step.

2. Check the rules again

You’ve already read the funding rules, right? If not, go and read them now – I’ll wait right here until you get back.

Once you’ve listed everything you want to do, go back and read the specific rules for budgets again. What is and isn’t allowed? The funding scheme won’t pay for equipment – you’ll need to fund your Thingatron from somewhere else. Cross it off.

Some schemes won’t fund people. Others won’t fund travel. It is important to know what you need for your project. It is just as important to know what you can include in the application that you are writing right now.

Most funding schemes won’t fund infrastructure (like building costs) and other things that aren’t directly related to the project. Some will, though. If they do, you should include overheads (i.e. the general costs that your organisation needs to keep running). This includes the cost of basics like power and lighting; desks and chairs; and cleaners and security staff. It also includes service areas like the university library. Ask your finance officer for help with this. Often, it is a percentage of the overall cost of the project.

If you are hiring people, don’t forget to use the right salary rate and include salary on-costs. These are the extra costs that an organisation has to pay for an employee, but that doesn’t appear in their pay check. This might include things like superannuation, leave loading, insurance, and payroll tax. Once again, your finance officer can help with this.

Your budget list might now look like this:

- 10 interviews in Kuala Lumpur; 10 interviews in Singapore; 10 interviews in Jakarta by me.

- Teaching release for three months for fieldwork.

- Flights to KL, Singapore, Jakarta and back to Melbourne.

- Accommodation for a month in each place, plus per diem, plus travel insurance (rule 3F).

- Transcription of 30 interviews, by the transcription service.

- Analysis of transcribed results, by me. No teaching release required.

- Purchase and install Thingatron X32C, by Thing Inc . Not allowed by rule 3C . Organise access to Thingatron via partner organistion – this is an in-kind contribution to the project.

- Three trials a month with Thingatron, by research assistant.

- Statistical analysis of Thingatron results, by research assistant.

- Research assistant: 1 day per week for a year at Level B1, plus 25.91% salary on-costs.

- Overheads at 125% of total cash request, as per rule 3H.

3. Cost each item

For each item on your list, find a reasonable cost for it . Are you going to interview the fifty people and do the statistical analysis yourself? If so, do you need time release from teaching? How much time? What is your salary for that period of time, or how much will it cost to hire a replacement? Don’t forget any hidden costs, like salary on-costs.

If you aren’t going to do the work yourself, work out how long you need a research assistant for. Be realistic. Work out what level you want to employ them at, and find out how much that costs.

How much is your Thingatron going to cost? Sometimes, you can just look that stuff up on the web. Other times, you’ll need to ring a supplier, particularly if there are delivery and installation costs.

Jump on a travel website and find reasonable costs for travel to Kuala Lumpur and the other places. Find accommodation costs for the period that you are planning to stay, and work out living expenses. Your university, or your government, may have per diem rates for travel like this.

Make a note of where you got each of your estimates from. This will be handy later, when you write the budget justification.

- 10 interviews in Kuala Lumpur; 10 interviews in Singapore; 10 interviews in Jakarta by me (see below for travel costs).

- Teaching release for three months for fieldwork = $25,342 – advice from finance officer.

- Flights to KL ($775), Singapore ($564), Jakarta ($726), Melbourne ($535) – Blue Sky airlines, return economy.

- Accommodation for a month in each place (KL: $3,500; Sing: $4,245; Jak: $2,750 – long stay, three star accommodation as per TripAdviser).

- Per diem for three months (60 days x $125 per day – University travel rules).

- Travel insurance (rule 3F): $145 – University travel insurance calculator .

- Transcription of 30 interviews, by the transcription service: 30 interviews x 60 minutes per interview x $2.75 per minute – Quote from transcription service, accented voices rate.

- Analysis of transcribed results, by me. No teaching release required. (In-kind contribution of university worth $2,112 for one week of my time – advice from finance officer ).

- Purchase and install Thingatron X32C, by Thing Inc . Not allowed by rule 3C. Organise access to Thingatron via partner organistion – this is an in-kind contribution to the project. ($2,435 in-kind – quote from partner organisation, at ‘favoured client’ rate.)

- Research assistant: 1 day per week for a year at Level B1, plus 25.91% salary on-costs. $12,456 – advice from finance officer.

Things are getting messy, but the next step will tidy it up.

4. Put it in a spreadsheet

Some people work naturally in spreadsheets (like Excel). Others don’t. If you don’t like Excel, tough. You are going to be doing research budgets for the rest of your research life.

When you are working with budgets, a spreadsheet is the right tool for the job, so learn to use it! Learn enough to construct a simple budget – adding things up and multiplying things together will get you through most of it. Go and do a course if you have to.

For a start, your spreadsheet will multiply things like 7 days in Kuala Lumpur at $89.52 per day, and it will also add up all of your sub-totals for you.

If your budget doesn’t add up properly (because, for example, you constructed it as a table in Word), two things will happen. First, you will look foolish. Secondly, and more importantly, people will lose confidence in all your other numbers, too. If your total is wrong, they will start to question the validity of the rest of your budget. You don’t want that.

If you are shy of maths, then Excel is your friend. It will do most of the heavy lifting for you.

For this exercise, the trick is to put each number on a new line. Here is how it might look.

5. Justify it

Accompanying every budget is a budget justification. For each item in your budget, you need to answer two questions:

- Why do you need this money?

- Where did you get your figures from?

The budget justification links your budget to your project plan and back again. Everything item in your budget should be listed in your budget justification, so take the list from your budget and paste it into your budget justification.

For each item, give a short paragraph that says why you need it. Refer back to the project plan and expand on what is there. For example, if you have listed a research assistant in your application, this is a perfect opportunity to say what the research assistant will be doing.

Also, for each item, show where you got your figures from. For a research assistant, this might mean talking about the level of responsibility required, so people can understand why you chose the salary level. For a flight, it might be as easy as saying: “Blue Sky airlines economy return flight.”

Here is an example for just one aspect of the budget:

Fieldwork: Kuala Lumpur

Past experience has shown that one month allows enough time to refine and localise interview questions with research partners at University of Malaya, test interview instrument, recruit participants, conduct ten x one-hour interviews with field notes. In addition, the novel methodology will be presented at CONF2015, to be held in Malaysia in February 2015.

Melbourne – Kuala Lumpur economy airfare is based on current Blue Sky Airlines rates. Note that airfares have been kept to a minimum by travelling from country to country, rather than returning to Australia.

1 month accommodation is based on three star, long stay accommodation rates provided by TripAdvisor.

30 days per diem rate is based on standard university rates for South-East Asia.

Pro tip: Use the same nomenclature everywhere. If you list a Thingatron X32C in your budget, then call it a Thingatron X32C in your budget justification and project plan. In an ideal world, someone should be able to flip from the project plan, to the budget and to the budget justification and back again and always know exactly where they are.

- Project plan: “Doing fieldwork in Malaysia? Whereabouts?” Flips to budget.

- Budget: “A month in Kuala Lumpur – OK. Why a month?” Flips to budget justification.

- Budget justification: “Ah, the field work happens at the same time as the conference. Now I get it. So, what are they presenting at the conference?” Flips back to the project description…

So, there you have it: Make a list; check the rules; cost everything; spreadsheet it; and then justify it. Budget done. Good job, team!

This article builds on several previous articles. I have shamelessly stolen from them.

- Constructing your budget – Jonathan O’Donnell.

- What makes a winning budget ? – Jonathan O’Donnell.

- How NOT to pad your budget – Tseen Khoo.

- Conquer the budget, conquer the project – Tseen Khoo.

- Research on a shoestring – Emily Kothe.

- How to make a simple Gantt chart – Jonathan O’Donnell.

* Actually, there are some grant schemes that give you a fixed amount of money, which I think is a really great idea . However, you will still need to work out what you are going to spend the money on, so you will still need a budget at some stage, even if you don’t need it for the application.

Also in the ‘simple grant’ series:

- How to write a simple research methods section .

- How to make a simple Gantt chart .

Share this:

28 comments.

This has saved my day!

Happy to help, Malba.

Like Liked by 1 person

[…] you be putting in a bid for funding? Are there costs involved, such as travel or equipment costs? Research Whisperer’s post on research budgets may help you […]

I’ve posted a link to this article of Jonathan’s in the Australasian Research Management Society LinkedIn group as well, as I’m sure lots of other people will want to share this.

Thanks, Miriam.

This is great! Humorous way to talk explain a serious subject and could be helpful in designing budgets for outreach grants, as well. Thanks!

Thanks, Jackie

If you are interested, I have another one on how to do a timeline: https://theresearchwhisperer.wordpress.com/2011/09/13/gantt-chart/

[…] really useful information regarding budget development can be found on the Research Whisperer Blog here. Any other thoughts and suggestions are welcome – what are your tips to developing a good […]

[…] it gets you to the level of specificity that you need for a detailed methods section. Similarly, working out a budget for your workshops will force you to be specific about how many people will be attending (venue […]

A friend of mine recently commented by e-mail:

I was interested in your blog “How to make a simple research budget”, particularly the statement: “Think through the implications of what you are going to do. Do you need to use a Thingatron? Note down that you will need to buy it, install it, and commission it.”

From my limited experience so far, I’d think you could add:

“Who else is nearby who might share the costs of the Thingatron? If it’s a big capital outlay, and you’re only going to use it to 34% of it’s capacity, sharing can make the new purchase much easier to justify. But how will this fit into your grant? And then it’s got to be maintained – the little old chap who used to just do all that odd mix of electrickery and persuasion to every machine in the lab got retrenched in the last round. You can run it into the ground. But that means you won’t have a reliable, stable Thingatron all ready to run when you apply for the follow-on grant in two years.”

[…] (For more on this process, take a look at How to Write a Simple Project Budget.) […]

[…] Source: How to make a simple research budget […]

This is such a big help! Thank You!

No worries, Claudine. Happy to help.

Would you like to share the link of the article which was wrote about funding rules? I can’t find it. Many thanks!

Hello there – do you mean this post? https://theresearchwhisperer.wordpress.com/2012/02/14/reading-guidelines

Thank @tseen khoo, very useful tips. I also want to understand more about 3C 3F 3H. What do they stand for? Can you help me find out which posts talk about that. Thank again.

[…] mount up rapidly, even if you are in a remote and developing part of the world. Putting together a half decent budget early on and being aware of funding opportunities can help to avoid financial disaster half way […]

This is so amazing, it really helpful and educative. Happy unread this last week before my proposal was drafted.

Happy to help, Babayomi. Glad you liked it.

really useful! thanks kate

[…] “How to Make a Simple Research Budget,” by Jonathan O’Donnell on The Research Whisperer […]

[…] offering services that ran pretty expensive. until I found this one. It guided me through making a simple budget. The information feels sort of like a university graduate research paper but having analysed […]

[…] Advice on writing research proposals for industry […]

[…] research serves as the bedrock of informed budgeting. Explore the average costs of accommodation, transportation, meals, and activities in your chosen […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Looking for RFP360? Log in here

How to Estimate a Proposal Budget: Considerations, Calculators, Communication

Why You Need the Ultimate Library for Your RFP Responses

Respond to RFPs , Responding to RFPs

Updated: Feb 8th, 2024

Creating an effective proposal budget is key to writing a winning proposal.

But it’s not exactly easy.

Your proposal budget has to be accurate, justifiable, and appealing … all while ensuring profitability for your organization.

(Learn how RFP360 can help you streamline the proposal management process.)

But what exactly is a proposal budget?

A proposal budget is the budget you put forth in a business proposal. It serves as an estimate of the cost your prospect will pay if they select your organization.

Below, we’ll provide advice to help you create an effective proposal budget in the form of considerations, calculators, and communication tips.

5 Key Proposal Budget Considerations

When creating a proposal budget, you must consider five key factors.

- Research and development.

- Travel costs.

- Operational expenses.

- Profit margin.

1. Salary Costs

To calculate the salary cost for your proposal, determine who will be involved in the project.

For example, an ad agency might support their clients with:

- Account executives.

- Creative directors.

- Art directors.

- Copywriters.

- Media buyers.

A software company, on the other hand, might rely on:

- Customer success representatives.

- Support representatives.

- Implementation specialists.

Once you know who will support the prospect if they select your organization, determine how much they make per hour.

Then, simply multiply that figure by the number of hours they will need to work.

2. Research and development

Your proposal budget should also take research and development costs into consideration.

How much did your organization invest in determining whether you had a viable market and offering? How much did you spend actually creating the offering?

While you won’t put the burden of recouping these costs on a single client, they are important to keep in mind.

3. Travel costs

If your employees must travel to satisfy your proposal, factor in these costs, as well.

This may include salespeople, implementation specialists, trainers, account managers, or anyone else who does on-site visits with the client.

4. Operational expenses

Operational expenses are crucial to remember when creating a proposal budget. After all, you have to keep the lights on.

Calculate costs such as marketing, sales, rent, utilities, maintenance, general staff, and any other expenses your organization must incur to continue operations.

5. Profit margin

Finally, understand your target profit margin.

While your business objective likely centers around your customers, you can’t serve anyone if you don’t stay in business.

Understand and consider your profit margin before finalizing your proposal budget.

Proposal Calculators

To help you accurately estimate your proposal budget, we’ve compiled a list of calculator tools.

NFWF Indirect Cost Calculator

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation offers this Indirect Cost Calculator tool “to assist applicants with calculating the allowable amount of indirect costs that can be included in proposal budgets.”

Price&Cost

Price&Cost is a software solution that offers “painless project budgeting and cost tracking.”

While the solution costs $90 per month in their lowest pricing tier, they offer a 14-day free trial.

Here’s a short, one-minute video that explains how it works:

Omnic Calculator

This tool is designed to work as an overall business budget calculator that “you can treat as a business budget worksheet to plan out the budget for upcoming months or to quickly reassess your priorities.”

It can, however, serve as your proposal budget calculator. Just ignore the income sections and focus on one-time costs, salaries, and monthly expenses.

Understanding Client Needs Through Communication

Effectively communicating your proposal budget is key.

One often-overlooked step in this process comes during the client discovery period: Understanding your prospect’s budget.

Creating a proposal budget that’s wildly out of line with their expectations won’t help anyone.

But how do you get your prospects to open up about their budget before you respond to their requests for proposals (RFPs)?

According to sales expert Lilly Ferrick , “You could come right out and ask, ‘What is your budget?’ But in doing so, unless you’ve already established a high degree of trust, you are likely to encounter obstacles.”

Instead, she suggests:

- Providing a typical budget range and asking if that falls in line with their expectations.

- Asking open-ended questions, like “What kind of budget do you have in mind?”

- Asking if they have determined a budget, and helping them determine one if they haven’t.

Approaching the topic in this manner allows prospects to engage in a fluid conversation, instead of locking them into a specific figure before they’re comfortable.

Use the insights gained from this discussion to tailor your proposal to their needs and limitations.

Once you’re ready to present your proposal budget, you’ll want to create a budget narrative — also known as a budget justification.

According to the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), a budget narrative serves two purposes:

- Explaining how you estimated the cost.

- Justifying the cost.

The key to writing a budget narrative that appeals to prospects is providing adequate detail and tying everything back to return on investment (ROI).

In most cases, organizations aren’t trying to avoid spending money — they’re trying to avoid wasting money.

As long as you can prove the money they invest in your organization will bring value, they’ll happily accept the cost.

How RFP360 can help

RFP360 — the only full-circle RFP management system on the market today — streamlines the entire proposal management process, empowering users to focus on creating compelling content that leads to wins.

“RFP360 has really helped us handle dramatic influxes,” said Technolutions Chief of Staff Laura Gardner. “For example, at one point last year, we had 12 RFPs due in one month, and we were able to submit responses to all of them.”

Learn how RFP360 can improve the proposal management process at your organization.

As RFP360’s sales director, Pat is responsible for implementing strategic growth initiatives, mentoring sales staff, and driving revenue. Before joining RFP360, he led the sales team for a growing tech firm as they launched their North American presence and new go-to-market strategies. When he’s not working or chasing down his one-and-a-half-year-old and three-and-a-half-year-old children, he enjoys golfing and watching live music.

- Product & Best Practices

- Selling & Enablement

- Content & Storytelling

- People & Teams

- Company & Events

- Customer Stories

Related Post

What proposal management tools do you need in your stack?

Without the right proposal management tools, responding to RFPs, RFIs and other information requests...

Why RFPs are a cornerstone in the enterprise sales cycle

Responders play a pivotal role in winning new business for enterprise organizations. You are a key...

Reducing RFx response time for a health insurance company from days to hours

Improving RFx response outcomes through automation, advanced content management, and winning trust from all users. Health insurance is one of...

See how it feels to respond with confidence

Why do 250,000+ users streamline their response process with Responsive? Schedule a demo to find out.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- Marketing Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

To learn more read our Cookie Policy .

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalized ads or content, and analyze our traffic. By choosing to leave these enabled, you consent to our use of cookies.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

- About Grants

- How to Apply - Application Guide

- Write Application

Develop Your Budget

Cost considerations, budgets: getting started.

- Allowable direct vs. allowable F&A costs

- Modular vs. Detailed Budgets

Modular Budgets

- Detailed Budget: Personnel (Sec A & B)

- Detailed Budget: Equipment, Travel, and Trainee Costs (Sec C, D, and E)

- Detailed Budget: Other Direct Costs (Sec F)

Consortiums/Subawards

Understanding the out years.

- Other resources

As you begin to develop a budget for your research grant application and put all of the relevant costs down on paper, many questions may arise. Your best resources for answering these questions are the grants or sponsored programs office within your own institution, your departmental administrative officials, and your peers. They can answer questions such as:

- What should be considered a direct cost or indirect cost?

- What is the fringe benefit rate?

- What is the graduate student stipend rate?

- What Facilities and Administrative (F&A) costs rate should I use?

Below are some additional tips and reminders we have found to be helpful for preparing a research grant application, mainly geared towards the SF424 (R&R) application. (Note: these tips do not supersede the budget instructions found in the relevant application instruction guide found on the How to Apply - Application Guide page.

An applicant's budget request is reviewed for compliance with the governing cost principles and other requirements and policies applicable to the type of recipient and the type of award. Any resulting award will include a budget that is consistent with these requirements. Information on the applicable cost principles and on allowable and unallowable costs under NIH grants is provided in the NIH Grants Policy Statement, Section 7.2 The Cost Principles Statement under Cost Considerations /grants/policy/nihgps/HTML5/section_7/7_cost_consideration.htm . In general, NIH grant awards provide for reimbursement of actual, allowable costs incurred and are subject to Federal cost principles /grants/policy/nihgps/HTML5/section_7/7.2_the_cost_principles.htm .

The cost principles address four tests that NIH follows in determining the allowability of costs. Costs charged to awards must be allowable, allocable, reasonable, necessary, and consistently applied regardless of the source of funds. NIH may disallow the costs if it determines, through audit or otherwise, that the costs do not meet the tests of allowability, allocability, reasonableness, necessity, and consistency.

- II.1 (Mechanism of Support),

- II.2 (Funds Available),

- III.2 (Cost Sharing or Matching), and

- IV.5 (Funding Restrictions).

- Identify all the costs that are necessary and reasonable to complete the work described in your proposal.

- Throughout the budgeting process, round to whole dollars and use only U.S. dollars.

- Reviewers look for reasonable costs and will judge whether your request is justified by your aims and methods.

- Reviewers will consider the person months you've listed for each of the senior/key personnel and will judge whether the figures are in sync with reviewer expectations, based on the research proposed.

- Significant over- or under-estimating suggests you may not understand the scope of the work. Despite popular myth, proposing a cost-sharing (matching) arrangement where you only request that NIH support some of the funding while your organization funds the remainder does not normally impact the evaluation of your proposal. Only a few select programs require cost-sharing, and these programs will address cost-sharing in the funding opportunity.

Direct Costs: Costs that can be identified specifically with a particular sponsored project, an instructional activity, or any other institutional activity, or that can be directly assigned to such activities relatively easily with a high degree of accuracy.

F&A Costs: Necessary costs incurred by a recipient for a common or joint purpose benefitting more than one cost objective, and not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefitted, without effort disproportionate to the results achieved. To facilitate equitable distribution of indirect expenses to the cost objectives served, it may be necessary to establish a number of pools of F&A (indirect) costs. F&A (indirect) cost pools must be distributed to benefitted cost objectives on bases that will produce an equitable result in consideration of relative benefits derived.

- The total costs requested in your budget will include allowable direct costs (related to the performance of the grant) plus allowable F&A costs. If awarded, each budget period of the Notice of Award will reflect direct costs, applicable F&A, and in the case of SBIR or STTR awards, a "profit" or fee .

- For most institutions the negotiated F&A rate will use a modified total direct cost base, which excludes items such as: equipment, student tuition, research patient care costs, rent, and sub-recipient charges (after the first $25,000). Check with your sponsored programs office to find out your negotiated direct cost base.

- When calculating whether your direct cost per year is $500,000 or greater, do not include any sub-recipient F&A in the base but do include all other direct costs as well as any equipment costs. NOTE: Direct cost requests equal to or greater than $500,000 require prior approval from the NIH Institute/Center before application submission. For more information, see NIH Guide Notice NOT-OD-02-004 .

- For many SBIR/STTR recipients, 40% of modified total direct costs is a common F&A rate, although rates at organizations may vary.

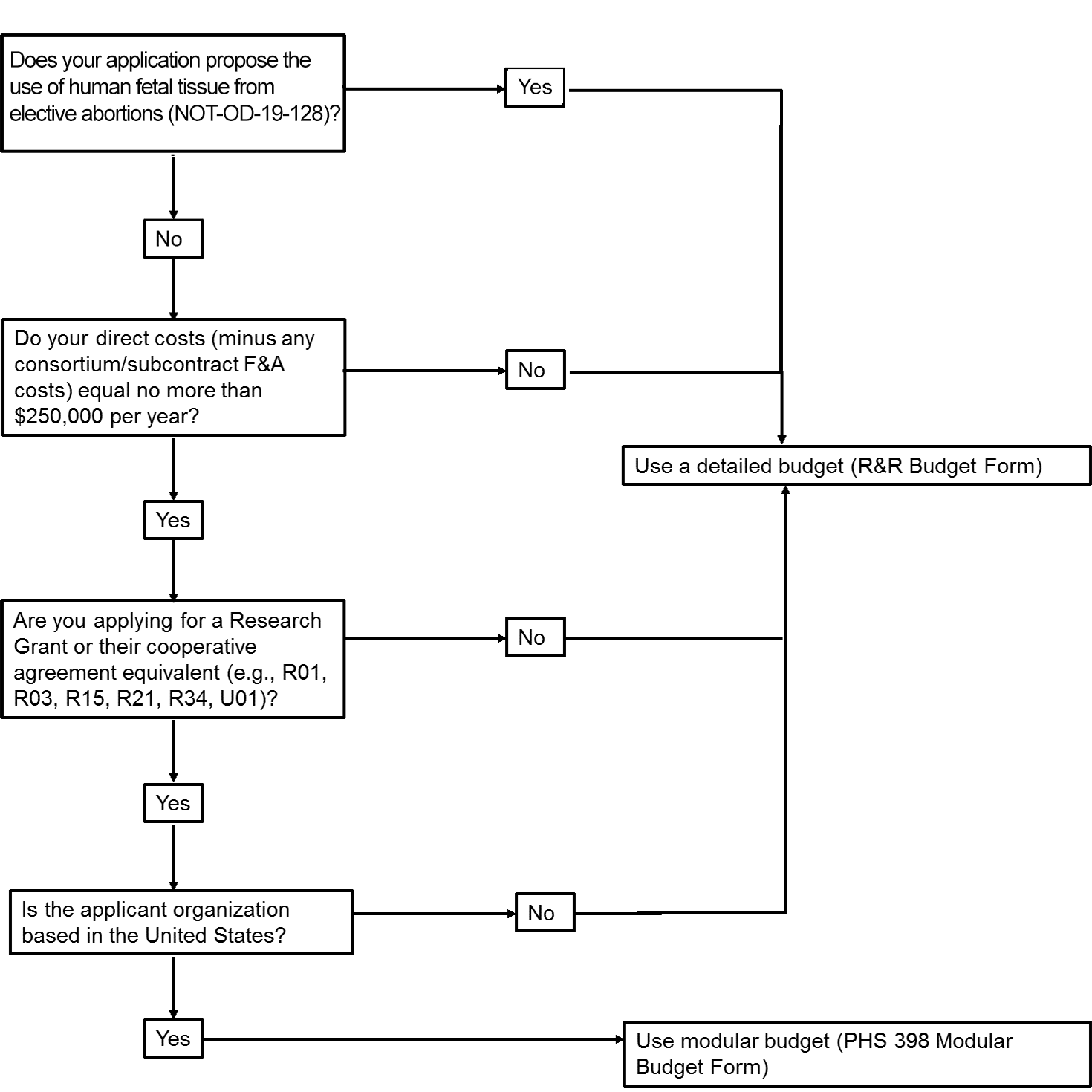

Modular versus Detailed Budgets

The NIH uses 2 different formats for budget submission depending on the total direct costs requested and the activity code used.

The application forms package associated with most NIH funding opportunities includes two optional budget forms—(1) R&R Budget Form; and, (2) PHS 398 Modular Budget Form. NIH applications will include either the R&R Budget Form or the PHS 398 Modular Budget Form, but not both. To determine whether to use a detailed versus modular budget for your NIH application, see the flowchart below.

NIH uses a modular budget format to request up to a total of $250,000 of direct costs per year (in modules of $25,000, excluding consortium F&A costs) for some applications, rather than requiring a full detailed budget. The modular budget format is NOT accepted for

- SBIR and STTR grant applications,

- applications from foreign (non-U.S.) institutions (must use detailed budget even when modular option is available), or

- applications that propose the use of human fetal tissue (HFT) obtained from elective abortions (as defined in NOT-OD-19-128 for HFT) whether or not costs are incurred.

Creating a modular budget

- Select the PHS398 Modular Budget form for your submission package, and use the appropriate set of instructions from the electronic application user's guide. You do not need to submit the SF424 (R&R) Budget form if you submit the PHS398 Modular Budget form.

- Consider creating a detailed budget for your own institution's use including salaries, equipment, supplies, graduate student tuition, etc. for every year of funds requested. While the NIH will not ask for these details, they are important for you to have on hand when calculating your F&A costs base and writing your justification, and for audit purposes.

- In order to determine how many modules you should request, subtract any consortium F&A from the total direct costs, and then round to the nearest $25,000 increment.

A modular budget justification should include:

- Personnel Justification: The Personnel Justification should include the name, role, and number of person-months devoted to this project for every person on the project. Do not include salary and fringe benefit rate in the justification, but keep in mind the legislatively mandated salary cap when calculating your budget. [When preparing a modular budget, you are instructed to use the current cap when determining the appropriate number of modules.]

- Consortium Justification: If you have a consortium/subcontract, include the total costs (direct costs plus F&A costs), rounded to the nearest $1,000, for each consortium/subcontract. Additionally, any personnel should include their roles and person months; if the consortium is foreign, that should be stated as well.

- Additional Narrative Justification: Additional justification should include explanations for any variations in the number of modules requested annually. Also, this section should describe any direct costs that were excluded from the total direct costs (such as equipment, tuition remission) and any work being conducted off-site, especially if it involves a foreign study site or an off-site F&A rate.

See the NIH Modular Research Grant Applications page and the NIH Grants Policy Statement for more information.

Detailed Budget: Personnel (Sections A & B)

Personnel make up sections A and B of the SF424 (R&R) Budget form. All personnel from the applicant organization dedicating effort to the project should be listed on the personnel budget with their base salary and effort, even if they are not requesting salary support.

- Effort : Effort must be reported in person months. For help converting percent effort to person months, see Usage of Person Months FAQs .

- Salary Caps: NIH will not pay requested salary above the annual salary cap, which can be found at Salary Cap Summary . If salary is requested above the salary cap, NIH will reduce that line item to the salary cap, resulting in a reduced total award amount. In future years, if the salary cap increases, recipients may rebudget to pay investigator salaries up to the new salary cap, but NIH will not increase the total award amount. If you are preparing a detailed budget, you are instructed to base your request on actual institutional base salaries (not the cap) so that NIH staff has the most current information in hand at the time of award and can apply the appropriate salary cap at that time.

- Fringe Benefits: The fringe benefits rate is based on your institution's policy; the NIH does not have a pre-set limit on fringe benefits. More information on what is included as fringe benefits can be found in the Grants Policy Statement at /grants/policy/nihgps/HTML5/section_12/12.8.1_salaries_and_fringe_benefits.htm . If you have questions about what rate to use, consult your institution's sponsored programs office.

- Senior/Key Personnel: The Senior/Key Personnel section should include any senior or key personnel from the applicant organization who are dedicating effort to this project. "Other Significant Contributors" who dedicate negligible effort should not be included. Some common significant contributors include: 1) CEOs of companies who provide overall leadership, but no direct contribution to the research; and 2) mentors for K awardees, who provide advice and guidance to the candidate but do not work on the project. Likewise, any consultants or collaborators who are not employed by the applicant organization should not be included in section A, but rather should be included in section F.3 of the budget (for consultants) or in section A of the consortium/subaward budget page (for collaborators).

- Postdoctoral Associates: Postdocs can be listed in either section A or B depending on their level of involvement in project design and execution. If listed in section B, include the individuals' names and level of effort in the budget justification section.

- Other Personnel: Other personnel can be listed by project role. If multiple people share the same role such as "lab technician", indicate the number of personnel to the left of the role description, add their person months together, and add their requested salaries together. The salaries of secretarial/clerical staff should normally be treated as F&A costs. Direct charging of these costs may be appropriate where a major project or activity explicitly budgets for administrative or clerical services and individuals involved can be specifically identified with the project or activity [see Exhibit C of OMB Circular A-21 (relocated to 2 CFR, Part 220)]. Be specific in your budget justifications when describing other personnel's roles and responsibilities.

Detailed Budget: Equipment, Travel, and Trainee Costs (Sections C, D, and E)

- Generally equipment is excluded from the F&A base, so if you have something with a short service life (< 1 year), even if it costs more than $5,000, you are better off including it under "supplies".

- If you request equipment that is already available (listed in the Facilities & Other Resources section, for example), the narrative justification must explain why the current equipment is insufficient to accomplish the proposed research and how the new equipment's use will be allocated specifically to the proposed research. Otherwise, NIH may disallow this cost.

- General purpose equipment, such as desktop computers and laptops, that will be used on multiple projects or for personal use should not be listed as a direct cost but should come out of the F&A costs, unless primarily or exclusively used in the actual conduct of the proposed scientific research.

- While the application does not require you to have a price quote for new equipment, including price quotes in your budget justification can aid in the evaluation of the equipment cost to support the project.

- Trainee Costs: Leave this section blank unless otherwise stated in the funding opportunity. Graduate student tuition remission can be entered in section F.8.

Detailed Budget: Other Direct Costs (Section F)

- Materials and Supplies: In the budget justification, indicate general categories such as glassware, chemicals, animal costs, including an amount for each category. Categories that include costs less than $1,000 do not have to be itemized.

- Animal Costs: While included under "materials and supplies", it is often helpful to include more specific details about how you developed your estimate for animal costs. Include the number of animals you expect to use, the purchase price for the animals (if you need to purchase any), and your animal facility's per diem care rate, if available. Details are especially helpful if your animal care costs are unusually large or small. For example, if you plan to follow your animals for an abnormally long time period and do not include per diem rates, the reviewers may think you have budgeted too much for animal costs and may recommend a budget cut.

- Publication Costs: You may include the costs associated with helping you disseminate your research findings from the proposed research. If this is a new application, you may want to delay publication costs until the later budget periods, once you have actually obtained data to share.

- Consultant Services: Consultants differ from Consortiums in that they may provide advice, but should not be making decisions for the direction of the research. Typically, consultants will charge a fixed rate for their services that includes both their direct and F&A costs. You do not need to report separate direct and F&A costs for consultants; however, you should report how much of the total estimated costs will be spent on travel. Consultants are not subject to the salary cap restriction; however, any consultant charges should meet your institution's definition of "reasonableness".

- ADP/Computer Services: The services you include here should be research specific computer services- such as reserving computing time on supercomputers or getting specialized software to help run your statistics. This section should not include your standard desktop office computer, laptop, or the standard tech support provided by your institution. Those types of charges should come out of the F&A costs.

- Justify basis for costs, itemize by category.

- Enter the total funds requested for alterations and renovations. Where applicable, provide the square footage and costs.

- If A&R costs are in excess of $300,000 further limitations apply and additional documentation will be required.

- The names of any hospitals and/or clinics and the amounts requested for each.

- If both inpatient and outpatient costs are requested, provide information for each separately.

- Provide cost breakdown, number of days, number of patients, costs of tests/treatments.

- Justify the costs associated with standard care or research care. (Note: If these costs are associated with patient accrual, restrictions may be justified in the Notice of Award.) (See NIH Grants Policy Statement NIH Grants Policy Statement, Research Patient Care Costs )

- Tuition: In your budget justification, for any graduate students on your project, include what your school's tuition rates are. You may have to report both an in-state and out-of-state tuition rate. Depending on your school stipend and tuition levels, you may have to budget less than your school's full tuition rate in order to meet the graduate student compensation limit (equivalent to the NRSA zero-level postdoctorate stipend level).

- Human Fetal Tissue (HFT) from elective abortions: If your application proposes the use of human fetal tissue obtained from elective abortions (as defined in NOT-OD-19-128 ), you must include a line item titled “Human Fetal Tissue Costs” on the budget form and an explanation of those costs in the budget justification.

- Other: Some types of costs, such as entertainment costs, are not allowed under federal grants. NIH has included a list of the most common questionable items in the NIH Grants Policy Statement ( /grants/policy/nihgps/HTML5/section_7/7_cost_consideration.htm ). If NIH discovers an unallowable cost in your budget, generally we will discount that cost from your total award amount, so it is in your best interest to avoid requesting unallowable costs. If you have any question over whether a cost is allowable, contact your sponsored programs office or the grants management specialist listed on the funding opportunity.

If you are using the detailed budget format, each consortium you include must have an independent budget form filled out.

- In the rare case of third tier subawards, section F.5 "subawards/consortium/contractual" costs should include the total cost of the subaward, and the entire third tier award is considered part of the direct costs of the consortium for the purposes of calculating the primary applicant's direct costs.

- Cost Principles. Regardless of what cost principles apply to the parent recipient, the consortium is held to the standards of their respective set of cost principles.

- Consortium F&A costs are NOT included as part of the direct cost base when determining whether the application can use the modular format (direct costs < $250,000 per year), or determining whether prior approval is needed to submit an application (direct costs $500,000 or more for any year). NOTE: The $500K prior approval policy does not apply to applications submitted in response to RFAs or in response to other funding opportunities including specific budgetary limits above $500K.

- F&A costs for the first $25,000 of each consortium may be included in the modified total direct cost base, when calculating the overall F&A rate, as long as your institution's negotiated F&A rate agreement does not express prohibit it.

- If the consortium is a foreign institution or international organization, F&A for the consortium is limited to 8%.

- Consortiums should each provide a budget justification following their detailed budget. The justification should be separate from the primary recipient's justification and address just those items that pertain to the consortium.

- We do not expect your budget to predict perfectly how you will spend your money five years down the road. However, we do expect a reasonable approximation of what you intend to spend. Be thorough enough to convince the reviewers that you have a good sense of the overall costs.

- In general, NIH does not have policy on salary escalation submitted in an application. We advise applicants to request in the application the actual costs needed for the budget period and to request cost escalations only if the escalation is consistent with institutional policy. See Salary Cap Summary and https://grants.nih.gov/faqs#/fy2012_salary_cap_faqs.htm .

- Any large year-to-year variation should be described in your budget justification. For example, if you have money set aside for consultants only in the final year of your budget, be sure to explain why in your justification (e.g. the consultants are intended to help you with the statistical interpretation of the data and therefore are not needed before the final year).

- In general, NIH recipients are allowed a certain degree of latitude to rebudget within and between budget categories to meet unanticipated needs and to make other types of post-award changes. Some changes may be made at the recipient's discretion as long as they are within the limits established by NIH. In other cases, NIH prior written approval may be required before a recipient makes certain budget modifications or undertakes particular activities (such as change in scope). See NIH Grants Policy Statement - Changes in Project and Budget .

Other resources to help you create your budget

This page last updated on: September 11, 2019

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Help Downloading Files

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

- Develop a research budget

- Research Expertise Engine

- Precursors to research

- Funding Opportunities

- Grants vs contracts

- Sample Applications Library

- Factors to consider

- Internal Approval (formerly SFU Signature Sheet)

- Develop a research proposal

- Institutional support

- Review & submission

- Award & approval

- Award management

- Contracts & agreements

- Inventions & commercialization

- Ethics - human research

- Ethics - animal research

- Research safety

- Mobilizing Research

- Prizes & awards

- Training & events

- Forms & documents

On this page:

Basic components of a research budget, two models of budget development, other factors affecting your budget.

- Additional Resources

Budgets should provide the sponsor with an accurate assessment of all cost items and cost amounts that are deemed necessary and reasonable to carry out your project. They should be based upon your description or the statement of work. Budget justification provides more in-depth detail and reason for each cost and is often considered by reviewers as a good indicator of the feasibility of the research.

A research budget contains both direct costs and indirect costs (overhead), but the level of detail varies from sponsor to sponsor. The first step in developing a budget is to carefully read the guidelines of the funding opportunity being pursued.

There is no magic formula available for developing a budget but there are some basic steps to follow in order to develop an accurate budget:

- Define project tasks, timelines and milestones and determine the actual resources and costs required to complete these. Consider whether contingencies are needed (and confirm they are eligible expenses).

- Determine the eligible expense categories and maximum amount allowed by the sponsor. Adjust scope of the project to make sure proposed activities fit within the allowance.

- Categorize these costs (e.g., salaries, supplies, equipment…) per year, in some cases by quarter.

- Ensure that project scope and budget match. Include indirect costs of research as permitted by sponsor and the University policy.

The examples below developed by the University of British Columbia demonstrate two ways to include indirect costs in your budget.

- Price model: Indirect cost is built into each budget line item.

- Cost model: Indirect cost of research is presented as a separate line item.

Unless the sponsor specifies in writing that they require the indirect costs of research to be presented as a separate line item (Cost Model), the indirect cost should be built into each budget line item (Price Model). Indirect costs are normally included in the price of goods and services worldwide.

For example, you are developing a budget for a funding opportunity with an indirect cost rate of 25%. Your direct costs are $201,000 broken down by expense categories shown in the second column of the table below. The third and fourth colums present the two ways you can include the 25% overhead in your budget using the Price Model or the Cost Model, respectively:

In-kind and cash contributions, like other costs to the sponsored project, must be eligible and must be treated in a consistent and uniform manner in proposal preparation and in financial reporting.

Cash contributions

Cash contributions are actual cash transactions that can be documented in the accounting system. Examples of cash contributions include:

- allocation of compensated faculty and staff time to projects, or

- the purchasing of equipment by the university or other eligible sponsor for the benefit of the project.

In-kind contributions

In-kind contributions are both non-monetary or cash equivalent resources that can be given a cash value, such as goods and/or services in support of a research project or proposal. It is challenging to report on in-kind contribution, please make sure the numbers you use are well supported, consistent and easy to quantitate.

Examples of an in-kind contribution may include:

- Access to unique database or information

- Professional, analytical, and other donated services

- Employee salaries including benefits for time allocated to the project

- Study materials, technologies, or components

- Patents and licenses for use

- Use of facilities (e.g., lab or meeting spaces)

- Partner organization time spent participating in the project

- Eligible infrastructure items

Matching on sponsored projects

Some sponsored projects require the university and/or a third party to contribute a portion of the project costs–this contribution is known as matching.

Matching requirements may be in the form of an actual cash expenditure of funds or may be an “in-kind” match. For example:

- A 1:1 match would require $100 of a third-party matching for every $100 received from an agency.

- A 30% match would mean that of a total budget of $100, the agency would provide $70 and a third party would need to match $30.

Examples of agency programs that include some form of matching from a third party are:

- NSERC Collaborative Research and Development Grants

- NSERC Idea to Innovation Grants

- SSHRC Partnership Grants

- CIHR Industry Partnered Collaborative Research Program, and

- CIHR Proof of Principle Grants

Additional resources

- Current salary and benefit rates for graduate students and postdocs/research associates

- SFU Business and Travel Expense Policy

- Animal care services

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

Creating a Budget

In general, while your research proposal outlines the academic significance of your study, the budget and budget narrative show that you have an understanding of what it will cost for you to be able to perform this research. Your proposed budget should identify all the expenses that are necessary and reasonable for the success of your project—no more and no less. The Office of Undergraduate Research understands that estimates, by definition, are imprecise, yet we encourage students applying for funding to research all aspects of their budgets with honest diligence.

If your research requires you to be in the field or in another city, state, or country, travel expenses may include transportation (airline, train, taxi, etc.), passport and visa fees, as well as fees for any vaccinations you may need to travel. Be sure to include anticipated major incidental expenses, such as printing, copying, fees for accessing archives, etc.

Please note that our funding restrictions prevent us from providing support for lab materials, equipment, software, hardware, etc.

Keep in mind these tips:

Convert all foreign currency figures to U.S. dollars.

Round all figures to whole dollars.

Make sure your budget and your proposal are consistent.

Identify areas where you are making efforts to save money!

Browse through these sample budgets for a better idea of how to outline your expenses and contact us if you have questions!

Sample Budget 1

Sample Budget 2

Sample Budget 3

Sample Budget 4

- Vice-Chancellor

- Leadership and Governance

- Education Quality

- Sustainability

- Staff Directory

- Staff Profiles

- Staff Online

- Office of Human Resources

- Important Dates

- Accept and Enrol

- Student Forms

- Jobs for Students

- Future Students

- Scholarships

- Class Registration

- Online Courses

- Password Management

- Western Wifi - Wireless

- Accommodation

- The College

- Whitlam Institute

- Ask Western

- Staff Email

- WesternNow Staff Portal

- ResearchMaster

- Citrix Access

- Student Management System

- Exam Timetable

- Oracle Financials

- Casual Room Bookings

- Staff Profile Editor

- Vehicle Bookings

- Form Centre

- WSU SharePoint Portal

- Learning Guide Management System (LGMS)

- Student Email

- My Student Records (MySR)

- WesternLife

- WesternNow Student Portal

- My Exam Timetable

- Student Forms (eForms)

- Accept My Offer

Study with Us

- International

- Research Portal

- ResearchDirect

- Research Theme Program

- Researcher Development

- Funding Opportunities

- Preparing a Grant Application

- Research Ethics & Integrity

- Research Project Risk & Compliance

- Foreign Arrangements Scheme

- Managing Your Research Project

- Research Data Management

- Business Services

- Research Infrastructure

- Office of the DVC REI

- Research Services Update

- Contact Research Services

- Master of Research

- Research Degrees

- Find a Supervisor

- Graduate Research School

- Apply for a Research Degree

- Candidate Support and Resources

- HDR Knowledge Directory

- Research Ethics

- HDR Workshops

- Forms, Policies and Guidelines

- Giving to Western

- Bushfire and Natural Hazards

- Digital Health

- Future Food Systems

- RoZetta Institute

- Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment

- Ingham Institute

- Institute for Australian and Chinese Arts and Culture

- Institute for Culture and Society

- NICM Health Research Institute

- The MARCS Institute

- Translational Health Research Institute

- Australia India Water Centre

- Centre for Educational Research

- Centre for Infrastructure Engineering

- Centre for Research in Mathematics and Data Science

- Centre for Smart Modern Construction (c4SMC)

- Centre for Western Sydney

- Chinese Medicine Centre

- Global Centre for Land-Based Innovation

- International Centre for Neuromorphic Systems

- National Vegetable Protected Cropping Centre

- Transforming early Education And Child Health Research Centre (TeEACH)

- Urban Transformations Research Centre

- Writing and Society Research Centre

- Young and Resilient Research Centre

- Digital Humanities Research Group

- Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative (HADRI)

- Nanoscale Organisation and Dynamics Research Group

- Research at Western

- Research Impact

- - Research Portal

- - ResearchDirect

- - Researcher Development

- - Funding Opportunities

- - Definition of Research

- - Research or Consultancy Activity?

- - Writing a Project Description

- - Track Record Statement

- - Tips for ECRs

- - Developing a Budget

- - Budget Justification

- - Research Contracts

- - Research Codes

- - Research Project Risk and Compliance

- - Foreign Arrangements Scheme

- - Managing Your Project

- - Research Data Management

- Research Ethics and Integrity

- Research Management Solution (RMS)

- Research Participation Opportunities

Developing a Budget for Your Research Application

Budgets and budget justifications demonstrate feasibility, value for money and detail why you need an item for your project, as well as how you arrived at the costings.

Every research project has two budget categories: direct costs and indirect costs.

The University determines a set percentage for the indirect costs of funded research. Contact Grants Services for the correct figure to use.

Direct costs are costs integral to achieving the research objectives of a grant. The costs directly address the research objectives of the grant and relate to the research plan.

Direct cost examples:

- Personnel, e.g. research assistants, student stipends for PhDs, and staff costs. You need to factor in salary increases, on-costs (superannuation and payroll) and casual loadings . Always use the salary level and step corresponding with the skills and tasks required for the role. See the Position Descriptors in the relevant University Enterprise Agreement .

- Equipment, maintenance and travel (outline why you are going and for how long)

- Teaching relief

- Other (e.g. Consumables).

Indirect costs are institution costs that benefit and support research activities at the institution. Although they are necessary for the conduct of research and may be incurred during the project, they are costs that do not directly address the approved research objectives of a grant.

Indirect cost examples:

- Operations and maintenance of buildings (e.g. libraries, labs, meeting venues, IT such as computer access, specialist software, databases, secure cloud storage)

- Insurance, legal and financial services

- Hazardous waste disposal, and

- Regulatory and research compliance and administration of research services

All external research activities are expected to contribute to indirect costs except :

- Nationally competitive grants, such as ARC and NHMRC. This includes all Category 1 schemes.

- Registered charities listed on the ACNC register (opens in a new window)

- Grants transferred from another university

- Funding bodies that exclude or limit overheads or administrative costs (i.e. indirect costs) in their rules or guidelines

- Scholarships and internships

- Official Western Partnership projects

- Travel award type grants or facility usage type grants (e.g. Endeavour Fellowships, AINSE grants)

- Projects costed under $100,000 are discounted by waiving Western’s portion of the indirect costs.

Indirect costs are calculated by determining the direct costs first and then applying the indirect costs formula:

e.g. Direct costs = $50,000 x (indirect cost % figure) = Total project cost

Cash and in-kind support

Your project budget needs to include all cash and in-kind items it requires.

In-kind support is any non-cash contributions that a party gives to the project. In-kind can be contributed by Western Sydney University or by an external party, and can include:

- staff (e.g. time committed to the project which is not funded by the project)

- non-staff/infrastructure (e.g. if you are using lab space to conduct the project but are not receiving direct payment from the project to 'buy out' lab space)

- indirect costs

How to budget personnel and salaries

On-costs are direct costs associated with salary. These costs relate to superannuation, sick leave, payroll tax etc. and must be included your budget.

Access this link for more detail about Western on-costs

For the latest salary figures, please check with the Office of People

An example:

You are a Lead Chief Investigator (CI) on a non-Category 1 funding body project for one year. You commit 0.4 (FTE) of your time to the research = 2 days per week. You are paid at Academic Level E, Step 2, which is $188,944 per annum. You can calculate your salary inclusive of 28% on-costs as follows:

0.4 x 0.28 x 188,944 = 21,161.73

The budgeting of your salary, a direct cost of the research, should be listed as $21,161.73.

If your project covers three years, with the same or differing time commitments, you calculate this figure for each year of your project. Remember to factor in pay rises according to Step increases in multi-year grants.

You may also have a research assistant employed full-time for seven weeks at HEW Level 5, Step 3. You hire the assistant at the casual hourly rate of $48.97, which includes 25% leave loading. You add 16.5% on-costs to this figure:

48.97 x (35 x 7) = 11,997.65

11,997.65 x .165 = 1,979.50

1,979.50 + 11,997.65 = 13,977.15

The total cost to employ the research assistant is $13,977.15.

Note 1: the maximum period a person can be employed on a casual rate is 6 months.

Note 2: For some schemes, the funding provider stipulates a specific maximum rate for funding of salary on-costs, e.g. the Australian Research Council (ARC) funds on-costs at a rate of 30%, so you must use this figure.

- Grant Budget Calculator (Staff Login Required) (opens in a new window)

^ Back to top

Mobile options:

- Return to standard site

- Back to Top

International Students

Launch your career at UWS

- University Life

- Our Campuses

- Business and Community

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- HDR Research

- Student Life

- Why Western

- The Academy

- Western Sydney University Online

- Misconduct Rule

- Study with Integrity

- Student Completions

- Student Support

- Services and Facilities

- Working with us

- Career Development

- Salary and Benefits

- Manager/Supervisor Toolkit

- Future Staff

- Staff Services

- Researchers

- Current Students

- Community and Industry

- Alumni Awards

- Alumni Spotlight

- Alumni Benefits

- Alumni Affinity Groups

- Alumni Publications

- Alumni Giving

Western Sydney University

- Emergency Help

- Right to Information

- Complaints Unit

- Accessibility

- Website Feedback

- Compliance Program

- Admissions Transparency

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Outline Expenses/Budget in Your Dissertation Plan

4-minute read

- 9th May 2023

When drafting your dissertation outline plan , there’s a lot to consider. One crucial section not to overlook is your budget and expenses. A comprehensive budget shows that you have thought through your study thoroughly and are prepared to execute your research plan successfully. Here, we’ll go through the steps you’ll need to take to craft a budget, including a few examples of common budget structures.

Steps to Take to Create Your Budget

1. consult your adviser, committee members, and funding sources for guidelines.

The source or sources responsible for funding your dissertation research will likely have guidelines on what is and isn’t a billable expense. Before defining your projected costs, check your funding organization’s specifications on allowable expenses. It can also help to speak with your adviser and potentially other dissertation committee members about the specifics and general guidelines to ensure everyone’s on the same page when it comes to your anticipated costs.

2. List All of the Costs Associated With Implementing Your Desired Dissertation Plan

Depending on your type of research, setting, and particular project, a wide range of items might be appropriate to add to your budget. Go through your dissertation project plan from beginning to end and list all of the required tasks, along with who will complete them, to ensure you don’t miss any expenses. Although the list below is not comprehensive, and your items might vary depending on your research project, some standard costs to consider are:

● Salaries and wages for all personnel involved in the project (including time and other resources that will be expected from your adviser and committee members).

● Equipment and lab fees.

● Recruitment costs for study participants.

● Participant compensation.

● Software costs for data collection, storage, and analysis.

● Office supplies (including any printing of recruitment materials, study information pamphlets, or conference posters).

● Travel (including transport to and from field sites, conference registration fees, transportation, lodging, and meals).

● Journal or conference submission and publication fees for papers created from your dissertation research.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Costs involved with writing, editing, and proofreading services for your dissertation .

Additionally, while it’s advisable to work within the constructs of your funding sources, don’t sell your research study short. After writing down all of the essential costs needed to complete your research plan, ask yourself how you would use any further financial backing. Could you make a good argument as to why supplementary funding would add significant value to your work? If so, consider adding these line items to your budget as well. If you have to negotiate your budget, you can always circle back and reconsider these extra items.

3. Construct Your Budget

The institution overseeing your dissertation project might require your budget to be submitted in a specified structure or template. However, if this isn’t the case, there are several possible approaches to organizing and presenting it – just make sure to check with your institution for any specific guidelines or requirements.

A standard request is to list your expenses by grouping them into direct costs , such as equipment, travel, and wages for people working on the project, and indirect costs , which are expenses that aren’t solely associated with your research project, such as general administration, utilities, and the use of shared services or spaces like libraries. It’s also common to arrange your direct and indirect costs into a Line-Item Budget (LIB) , which simply means that you list each of your projected expenses as a line in your budget.

There are many types of budget templates available for free online. Some designs will include a column to provide more details about each item, while other approaches will list the justifications for the expenses at the end. If you have multiple funding sources, it may be helpful to have columns for each funder and the percentage or amount of each expense they will be expected to be responsible for. Some templates will calculate the total costs for you , but no matter which presentation method you choose, make sure your costs are entered and totaled correctly.

Although the individual items will vary from project to project, these three steps will lead you on your way to preparing a persuasive proposal budget:

● Consult your adviser, committee members, and funding sources for guidelines.

● List all the costs associated with implementing your desired dissertation plan (including the items you hope to get funded if they are justifiable).

● Construct your budget with direct and indirect costs with justifications for each using an appropriate template and confirm your expenses are calculated correctly.

We wish you the best of luck with your budget writing and dissertation proposal. For more help, check out our comprehensive Dissertation Writing Guide . And if you’re interested in using our services here at Proofed, you can try them for free .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Research and Economic Development

Preparing proposal budgets & budget justifications.

- SPA Departmental Assignments

Frequently Asked Questions

Contract and Grant Lifecycle

- Roles and Responsibilities Matrix

- Proposal Preparation/Submission

- Preaward Administration

- Award Negotiation and Setup

- Post-Award Administration

- Outgoing Subawards

- Award Closeout

Core Information

- Clinical Trials

- Data Management Resources

- DOE's Disclosure Requirements for Current & Pending Support

- Ethical and Responsible Conduct of Research

- Export Control

- Foreign Engagement

- Kuali Research

- Material Transfer Agreements

- NASA Restrictions on Funding Activity with China

- NIH Changes to Biosketch and Other Support

- NSF Broader Impacts

- PI and Award Transfers

General Information

- Reports (Annual, On Demand)

- Research Administrators INC

- Staff Directory

- UCR Contracting Guide

- Uniform Guidance

Outside Links

- UC Research Website

- UCOP AB20 Webpage

General Information for Preparing Proposal Budgets

Topics covered, definition of a budget, project costs, budgeting facilities and administrative costs as direct costs, cost estimation, escalation factors, cost assignment and allocation, documentation.

A categorical list of anticipated project costs that represent the Principal Investigator's best estimate of the funds needed to support the work described in a proposal. A budget consists of all direct costs, facilities and administrative costs, and cost sharing commitments proposed.

All proposed costs must clearly benefit the project and must be allowable under OMB Circular A-21 , sponsor policies, and University policies.

A facilities and administrative cost may be budgeted as a direct cost only when special circumstances exist that would necessitate or require treating the cost as a direct cost. In such a case, the budget justification must explain the special circumstances and the Principal Investigator and department are responsible for maintaining and retaining all appropriate documation that evidence such special circumstances.

Use generally accepted cost estimation methods such as catalog prices, price quotations, or historical or current costs and appropriately escalate costs over time.

Use inflationary or escalation factors as appropriate.

- The current escalation rate for non-personnel cost categories is 3% (excluding vivaria sales and service rates). Effective November 1, 2012, please use a 10% annual escalation rate for vivaria sales and services.

- Personnel costs should be escalated in accordance with guidance provided on the Quick Reference page.

When developing a budget, it is necessary to estimate how the project will incur costs during each phase or year. The budget must itemize costs by major cost category for each project year as required by the sponsor's guidelines.

When assigning costs to proposal budget categories, use UCR's financial system budget categories, unless a sponsor's proposal budget form or policies require more detailed categorization.

As appropriate, describe the details of the costs proposed within each major cost category. Use general descriptions that can be tracked and reported through UCR's financial system. The budget justification should disclose the details that make up each cost category, and may include more detailed information regarding the items in each general description, as well as explain the method used to estimate these costs.

The principal investigator and/or department must maintain supporting documentation related to project cost estimates (on a proposal-by-proposal basis) for negotiation and audit purposes. This documentation should clearly describe or demonstrate the processes, methods and data used to estimate project costs.

Examples of supporting documentation include:

- Current University salary and wage scales

- Projected range adjustments (cost of living increases) and merit increases for personnel costs and the periods to which they apply

- Source of the benefit rate used (composite rate or actual rate)

- Vendor quotes

- Catalog prices

- Historical records indicating the supply/material costs incurred for like projects

Guidance by Budget Category

Salary and wages, topics included, project personnel, calculating salaries, calculating merit increases and range adjustments, summer salaries for nine-month appointees, cost sharing personnel costs, employee salary range projections.

When providing information about project personnel, follow the sponsor's guidelines and University policies.

List only UCR project personnel in this category. Salary and wage costs associated with non-UCR personnel must be treated either as consultant costs or as a subcontract. Project personnel usually includes faculty, technicians, post-docs, graduate students and other personnel who are essential to perform the project.

Calculate all project personnel costs using actual salaries. If the individual who will fill a position is not known, calculate the salary by using the mid-point salary from the appropriate UCR salary scale.

Never express personnel costs or effort in terms of hours, except for student, casual and per diem employees who are paid by the hour.

Project anticipated merit increases and range adjustments as appropriate for each position in each budget period. There is a six- to nine-month delay between proposal submission and award, so remember to calculate personnel costs using current actual salaries plus any merit or cost of living increases anticipated between proposal submission and the proposed start date.

List summer salary for nine-month instruction and research appointees using one-ninth, two-ninths or three-ninths of the base salary or apporpirate fractions thereof (e.g., half of a summer month) to calculate the amount requested. Some sponsors (e.g., NSF) restrict summer salary compensation to no more than two months.

Cost sharing that is offered and quantified anywhere in a proposal will become a legally binding obligation upon UCR if the sponsor makes an award in response to the proposal. This obligation includes the requirement to track and report the costs that UCR shared to fulfill its commitment. Please note the University does not cost share on projects proposed to, or funded by, for-profit sponsors.