- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About International Studies Review

- About the International Studies Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, theoretical predictions, what the empirical evidence says, empirical challenges, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

On the Impact of Inequality on Growth, Human Development, and Governance

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ines A Ferreira, Rachel M Gisselquist, Finn Tarp, On the Impact of Inequality on Growth, Human Development, and Governance, International Studies Review , Volume 24, Issue 1, March 2022, viab058, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab058

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Inequality is a major international development challenge. This is so from an ethical perspective and because greater inequality is perceived to be detrimental to key socioeconomic and political outcomes. Still, informed debate requires clear evidence. This article contributes by taking stock and providing an up-to-date overview of the current knowledge on the impact of income inequality, specifically on three important outcomes: (1) economic growth; (2) human development, with a focus on health and education as two of its dimensions; and (3) governance, with emphasis on democracy. With particular attention to work in economics, which is especially developed on these topics, this article reveals that the existing evidence is somewhat mixed and argues for further in-depth empirical work across disciplines. It also points to explanations for the lack of consensus embedded in data quality and availability, measurement issues, and shortcomings of the different methods employed. Finally, we suggest promising future research avenues relying on experimental work for microlevel analysis and reiterate the need for more region- and country-specific studies and improvements in the availability and reliability of data.

La desigualdad es un desafío importante para el desarrollo internacional. Esto es así desde una perspectiva ética y debido a que la mayor desigualdad se percibe como perjudicial para los resultados políticos y socioeconómicos clave. Aun así, los debates informados requieren pruebas claras. Esta revisión contribuye estudiando la situación y ofreciendo un resumen actualizado del conocimiento actual sobre el impacto de la desigualdad de ingresos, específicamente en tres resultados importantes: (1) el crecimiento económico; (2) el desarrollo humano, con un enfoque en la salud y la educación como dos de sus dimensiones; y (3) la gobernanza, con énfasis en la democracia. Prestando especial atención al trabajo en economía que se desarrolla particularmente sobre estos temas, este ensayo demuestra que las pruebas existentes están mezcladas de alguna manera y argumenta a favor de promover el trabajo empírico en profundidad en todas las disciplinas. También señala las explicaciones para la falta de consenso que están integradas en la calidad y la disponibilidad de los datos, los problemas de medición y los defectos de los diferentes métodos empleados. Finalmente, sugerimos prometedoras vías de investigación para el futuro que dependen del trabajo experimental para el análisis a pequeña escala, y reiteramos la necesidad de realizar más estudios específicos de la región y el país, así como mejoras en la disponibilidad y la confiabilidad de los datos.

L'inégalité est un défi majeur du développement international. Il en est ainsi d'un point de vue éthique et parce qu'une plus grande inégalité est perçue comme allant au détriment des principaux résultats socio-économiques et politiques. Toutefois, des preuves claires sont nécessaires pour débattre en connaissance de cause. Cette analyse y contribue en faisant le bilan et en offrant une présentation à jour des connaissances actuelles sur l'impact de l'inégalité des revenus, en particulier sur trois résultats importants: (1) la croissance économique, (2) le développement humain, en se concentrant sur la santé et l’éducation en tant que deux de ses dimensions, et (3) la gouvernance, en mettant l'accent sur la démocratie. Cet essai accorde une attention particulière aux travaux en économie qui sont particulièrement développés sur ces sujets et révèle que les preuves existantes sont quelque peu mitigées et plaide pour un travail empirique plus approfondi dans toutes les disciplines. Il met également en évidence des explications du manque de consensus inhérent à la qualité et à la disponibilité des données, aux problèmes de mesure et aux lacunes des différentes méthodes employées. Enfin, nous suggérons des pistes de recherches futures prometteuses qui s'appuieraient sur des travaux expérimentaux pour l'analyse au niveau micro et nous réitérons la nécessité de réaliser davantage d’études spécifiques aux régions et aux pays et d'améliorer la disponibilité et la fiabilité des données.

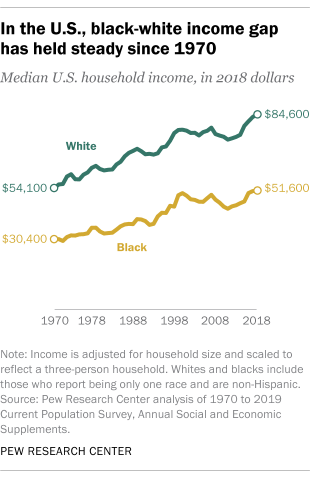

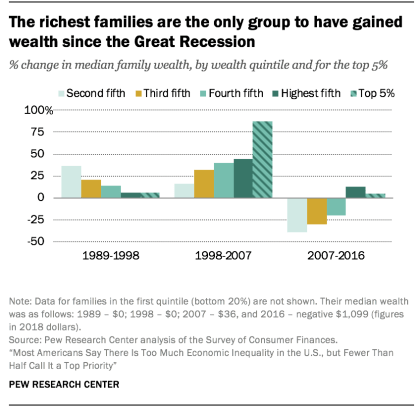

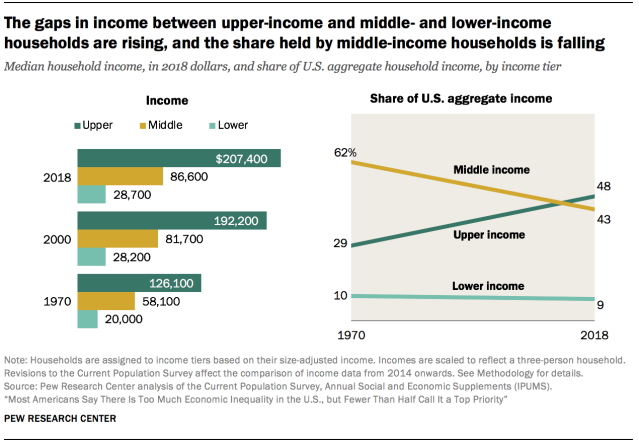

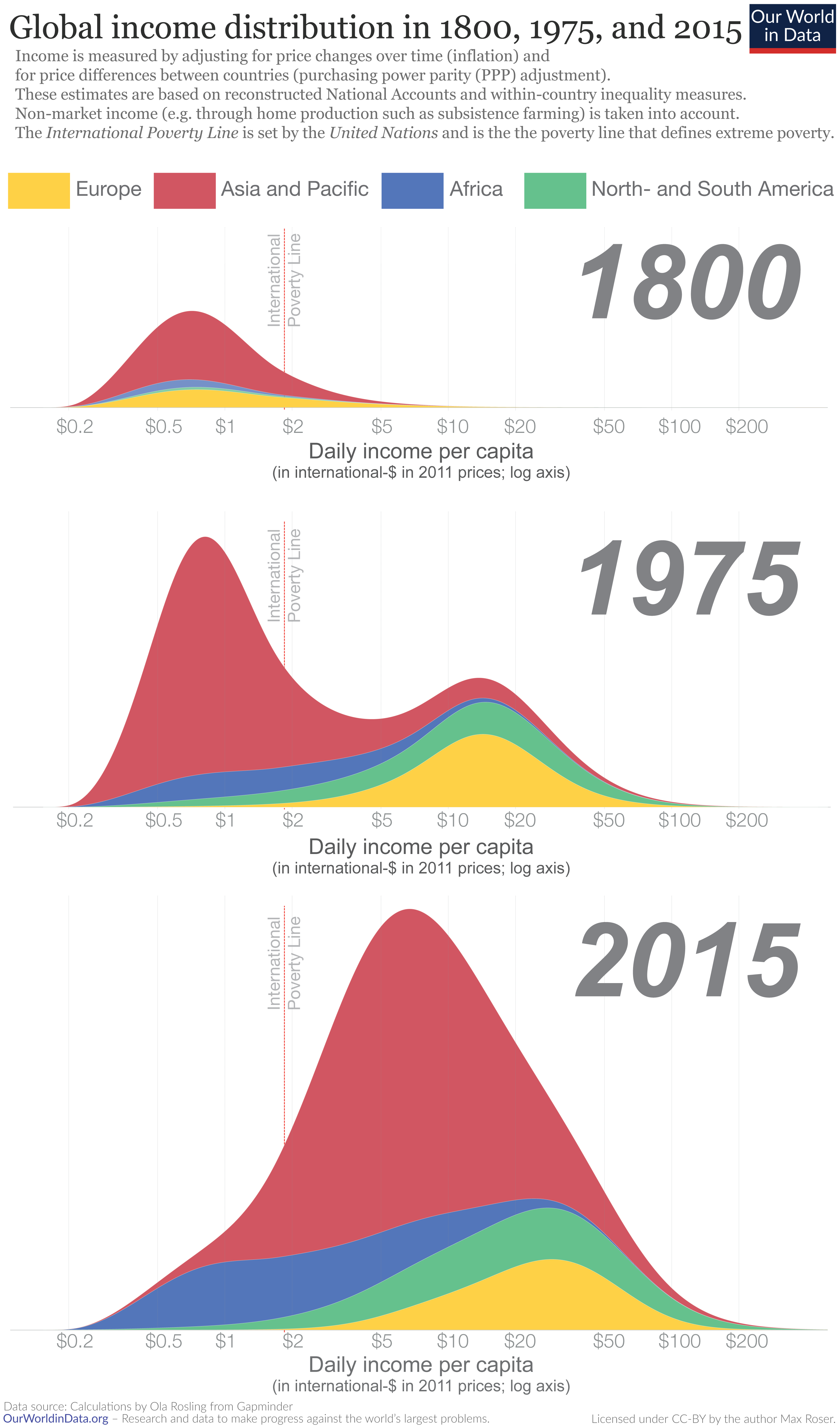

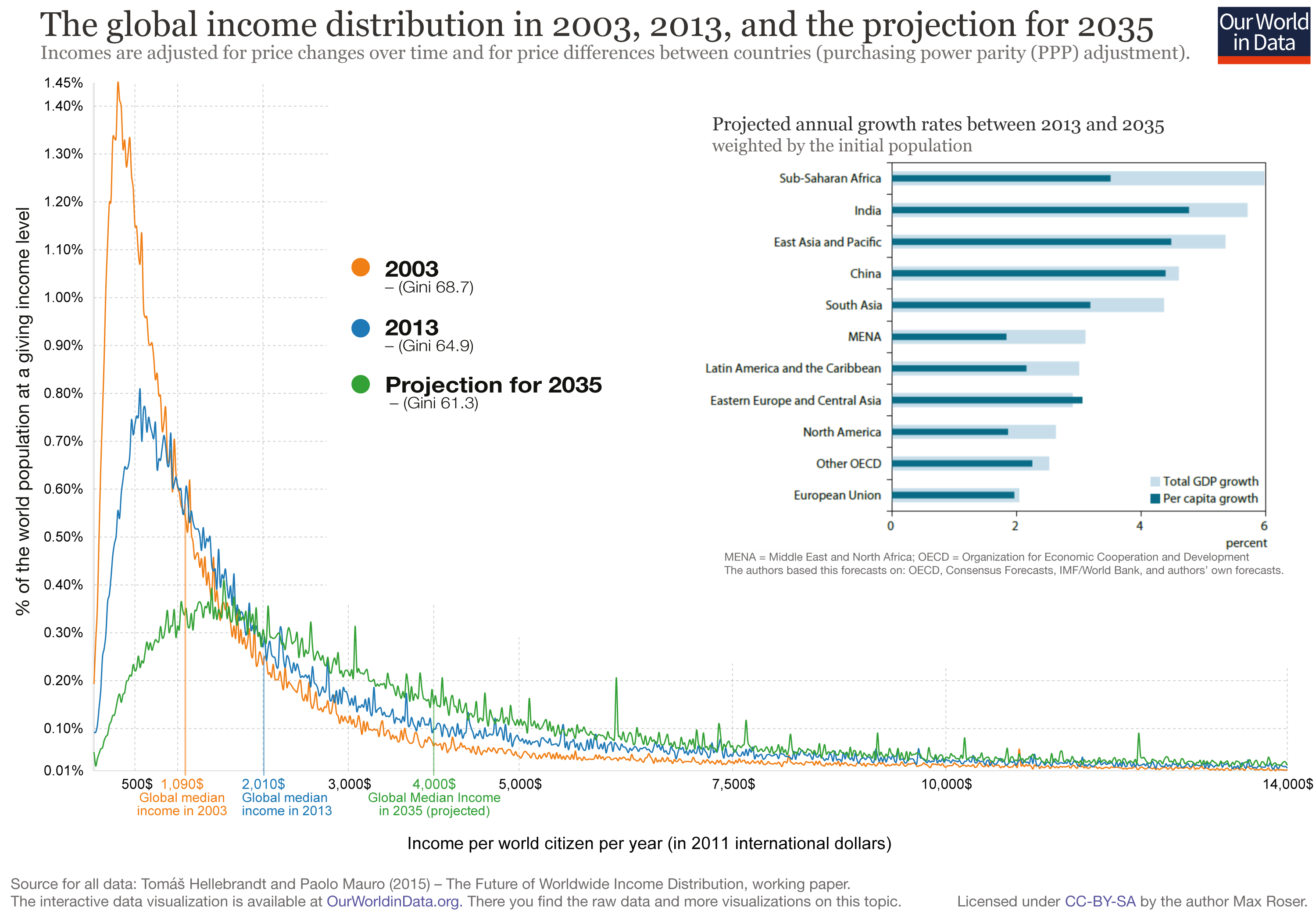

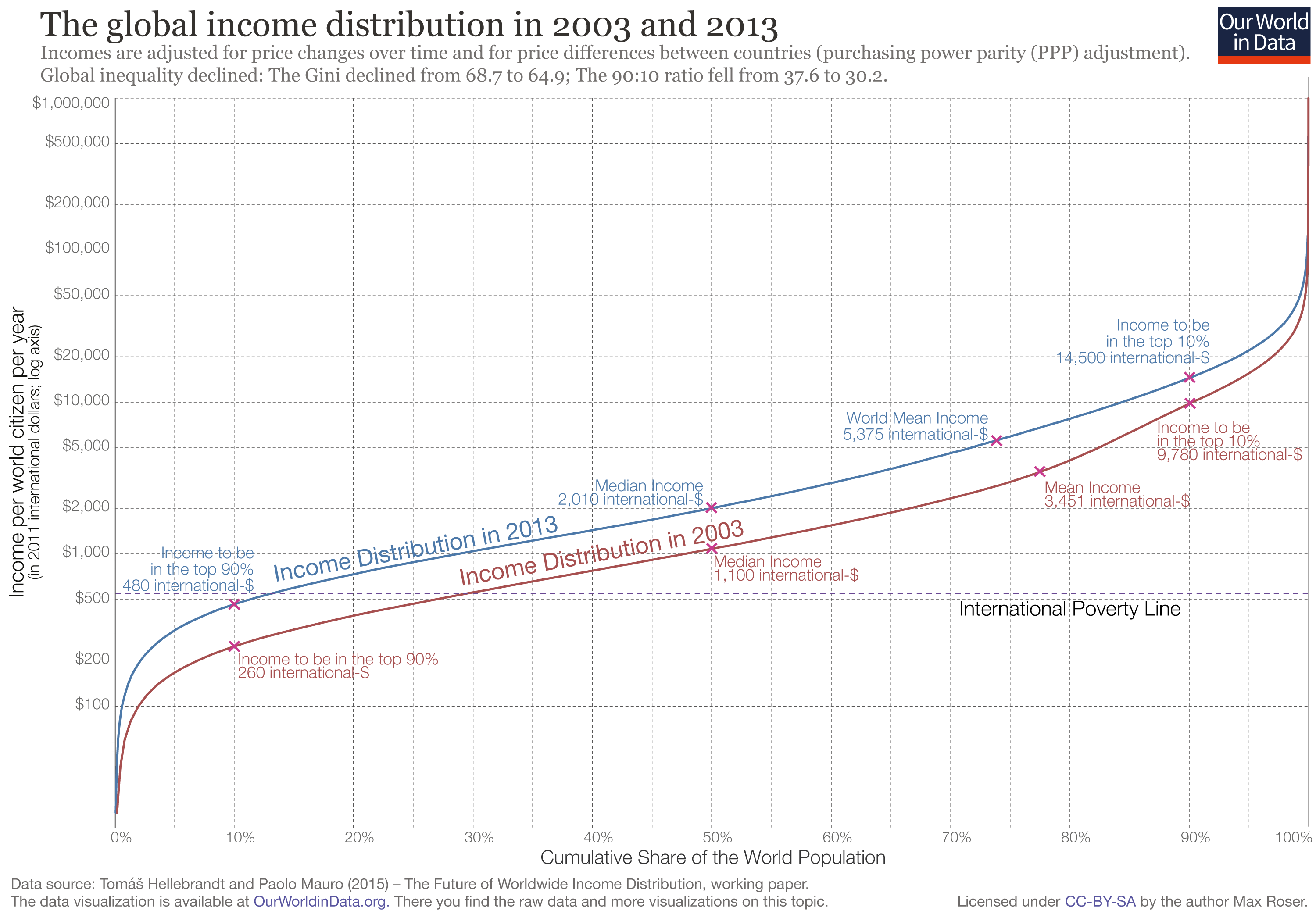

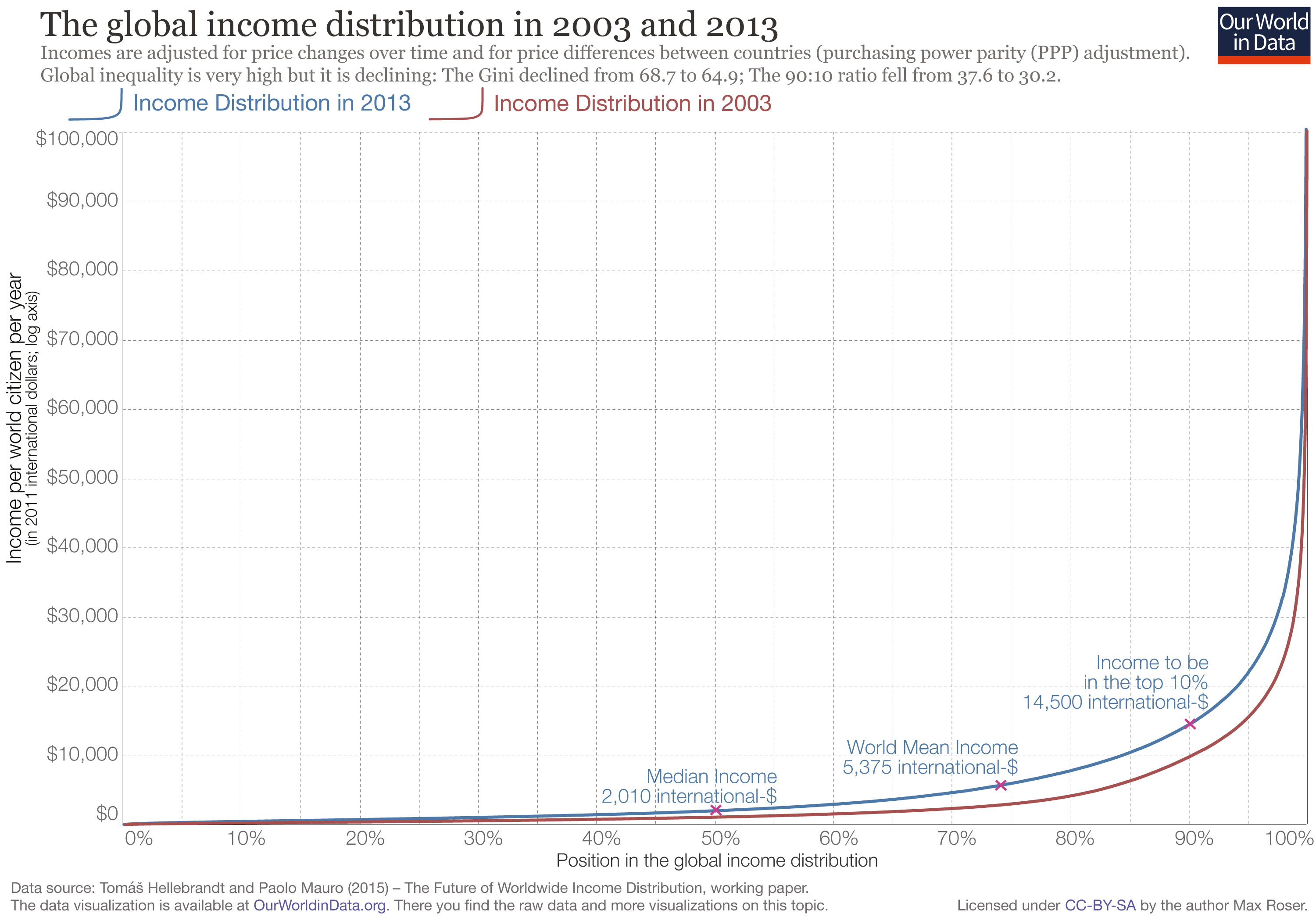

Recent decades have witnessed sharp rises in inequality of income and wealth in many countries (though neither globally nor everywhere) as well as in the observed level of inequality of opportunities in access to basic services, such as health and education. Concern with these trends is paramount in Goal 10 of the Sustainable Development Goals approved by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, aiming at “reducing inequality within and among countries.” The COVID-19 pandemic, which has both reflected and exacerbated inequalities, further spotlights this objective.

Pursuing this goal can obviously be justified from an ethical perspective. The case is also made in instrumental terms, with reference to potential negative effects of inequality on a variety of socioeconomic and political outcomes. The World Development Report (2006) drew attention to the implications of high levels of inequality for long-term development ( World Bank 2006 ). Indeed, economists in particular have long been concerned with the relationship between equity and efficiency 1 ; interestingly, the old classical view, contrary to the 2006 report, suggests a contradiction between equality and development.

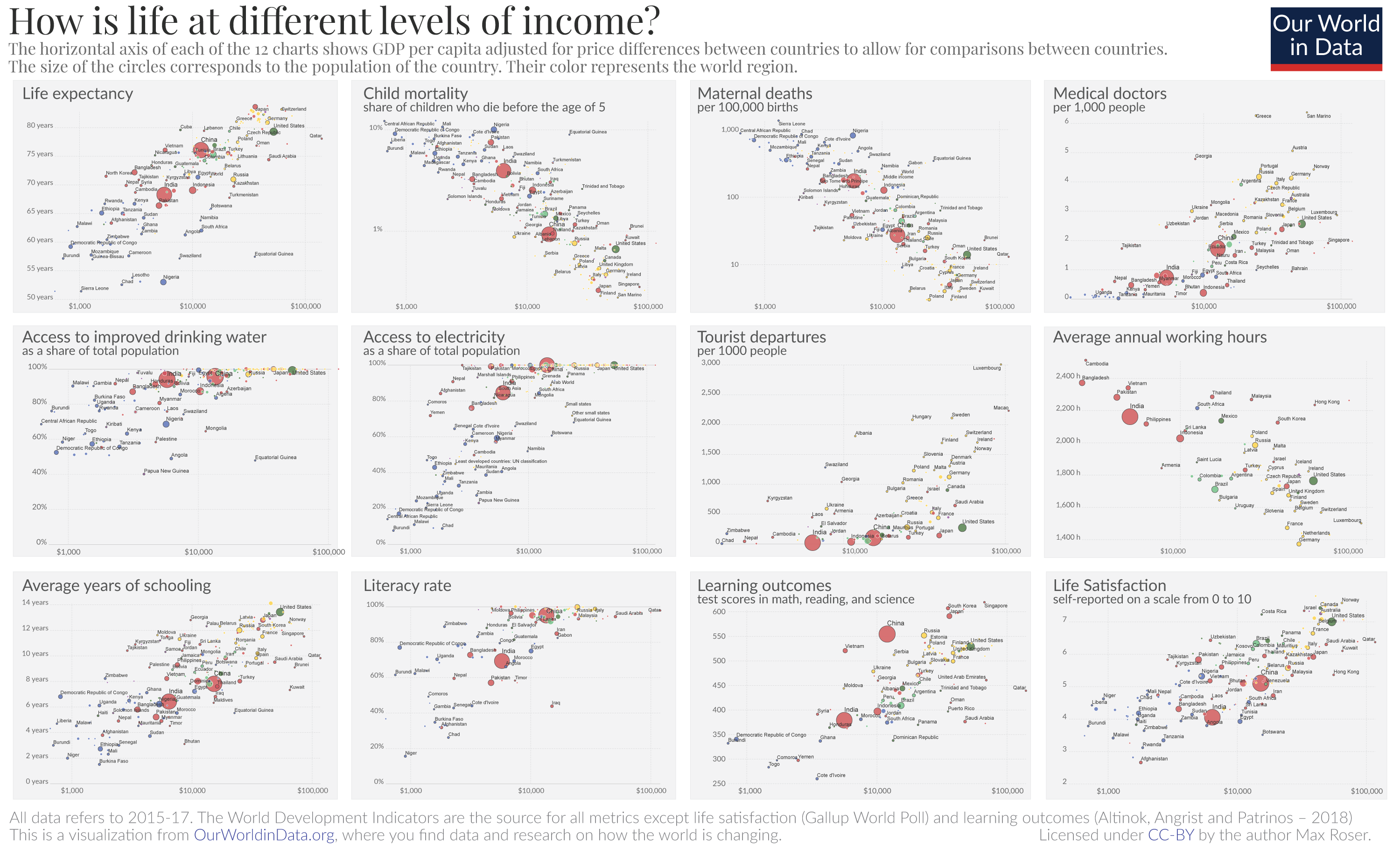

Informed policy debate requires clear evidence on these impacts. This analytical essay provides a “state-of-art” on research on this big question. While recent reviews of the literature tend to focus on the impact of inequality on one specific outcome, we have a broader scope; we aim to bring new clarity to the debate by taking stock of the current knowledge on the effects on three important outcomes: (1) economic growth; (2) human development, with a focus on health and education as two of its dimensions; and (3) governance, with emphasis on democracy. While we start by highlighting how the various processes are connected, we address the impacts of inequality on these outcomes separately, developing an overview of the core arguments and underlying mechanisms, and of the existing evidence, with a particular focus on cross-country insights.

We draw in particular on the large and well-developed literature on these topics in economics while also taking key insights from other disciplines. 2 Our focus is on broad outcomes that are of particular importance for international development and that received great attention in studies examining the impact of inequality across disciplines. The effects of inequality on economic growth have been extensively debated in economics, the main disciplinary focus of this article. However, health and education—two important channels with high policy relevance—have also been the object of investigation in public health studies. Moreover, the field of political science has greatly contributed to the debate addressing the effects of inequality on political aspects, including those related to democratic governance. 3

Building on previous reviews focusing on specific outcomes (e.g., Voitchovsky 2011 ; Neves and Silva 2014 ; O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti 2015 ; Scheve and Stasavage 2017 ), but adopting the broader outlook of the seminal review by Thorbecke and Charumilind (2002) , this article provides an updated and comprehensive perspective on the consequences of inequality in three core areas of concern for international studies. 4

We combine the main theoretical arguments on the impact of inequality and underlying transmission channels in a general framework, providing a simplified view while emphasizing the connections between different processes. Overall, our review of an extensive body of work suggests there is no clear consensus emerging from the empirical evidence, and we argue there is room for additional in-depth work to uncover the effects through specific mechanisms of transmission. In particular, there is no consensus from the results of studies using reduced-form equations to examine the effect on growth, and less work has been dedicated to exploring the channels of transmission. Moreover, the negative link between inequality and secondary school enrolment is confirmed by the evidence, but further research is needed in terms of other education outcomes. The economic and public health literatures disagree on whether the negative effect of inequality on health is confirmed by the existing evidence, and there are mixed results emerging from political scientists for the effects of inequality on democracy and political participation. We advance the underlying explanations for this state of affairs, related to the challenges inherent in data quality and availability, measurement issues, and shortcomings of the different estimation methods employed, and suggest avenues for further research.

In the second section, we offer an outline of the main theoretical predictions of the effects of inequality on socioeconomic outcomes and on governance, presenting different channels of transmission. The third section follows the same structure and reviews the existing empirical evidence. We reflect on key empirical challenges of estimating the effects of inequality in the fourth section. The fifth section concludes.

Several theoretical explanations exist across disciplines for the effects of inequality on socioeconomic and political outcomes. Before we describe in more detail these channels of influence and the resulting outcomes, we highlight a broader set of arguments, which act as a roadmap for the rest of the section. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview.

Diagram with main outcomes of inequality

Source : Authors’ elaboration.

Starting from the left- to the right-hand side, the diagram represents different channels of transmission of the effects of higher levels of inequality, their intermediate effects, and the resulting positive or negative impact on our three outcomes of interest: growth, 5 human development, and democracy. We broadly divide these channels according to their underlying drivers: the poor, the population at large or the average, and the wealthy.

Overall, the diagram suggests that high inequality has predominantly harmful effects on our three outcomes of interest, according to theoretical explanations advanced in the literature. The dominant view then runs contra the expectations of the classical theorists, i.e., that inequality has a positive impact on growth, via savings and investment (shown at the top of figure 1 ). We highlight six main transmission channels.

First, inequality affects incentives for savings and investment and the overall level of institutional quality through its influence on policy making and increased political instability, and consequent effects on property rights and the regulatory framework. This has implications for growth both directly and indirectly via governance.

Second, by favoring private over public investment, inequality affects investment in public goods, namely health and education, with implications across the three outcomes. Third, and related, inequality results in underinvestment on human capital resulting from credit constraints, and high fertility, which affects education levels and overall economic growth.

Fourth, high taxation will be demanded by a well-endowed median voter and the likelihood of transition to and stability of democracy will also depend on the pressure for redistribution, which is higher with lower levels of equality. Moreover, and fifth, a small middle class will affect the demand not only for democracy but also for manufactures.

Finally, high levels of polarization will lead to weak social cohesion via their effects on social capital, as well as low trust and potential high levels in violent crime, which affect health directly and indirectly via investment in public health. Additionally, the concentration of power on the rich leads to increased probability of political violence and affects political engagement.

Some of these channels affect all of the outcomes. For instance, the effect through investment in public goods has detrimental effects on human development, and on growth and democracy. Moreover, the resulting polarization and social discontent, which increase the chances of political violence, again negatively impact the three outcomes. However, there is also some indication that, when it comes to growth, the effect might be ambiguous depending on the predominance of the effects of transmission mechanisms. The channel through savings (and investment) points to a potential positive effect, while the different effects through public investment, taxation, the structure of demand, imperfect credit markets, fertility, and social discontent suggest potential negative consequences for growth.

This section uncovers more details about these different theoretical predictions. It starts by introducing the main hypotheses advanced for the effects of inequality on growth. While the approach in this article considers the three outcomes separately, we recognize that they are not disjointed or orthogonal and refer to the links between them. Nevertheless, a full discussion of these interlinkages is beyond the scope of this article. As suggested in figure 1 and described in more detail below, some of these channels point to the impact of inequality on our remaining outcomes of interest, namely education and health, or governance. We return to them in the remaining two subsections, where we expand to consider the insights from other strands of literature.

How Inequality Affects Growth

An extensive literature examines the effects of inequality on growth, 6 highlighting multiple channels of transmission. 7 The early studies, referred to as the classical approach, argued that there is a positive effect of inequality on growth, explained via savings or incentives. However, subsequent work questioned this view, challenging some of its assumptions and proposing different channels of influence. Most of this work has predicted a negative effect of inequality. We briefly outline these channels in the next paragraphs and refer to Bourguignon (2015) , Neves and Silva (2014) , and Voitchovsky (2011) for complementary detail and reviews. 8

High inequality is growth enhancing

We start by drawing attention to the view of classical economists on income inequality, according to which there was a contradiction between equality and development (for a discussion of the trade-off between efficiency and equity, see Thorbecke 2016 ). Adam Smith defended that inequality had benefits based on arguments of (1) “trickle-down effects”—the increase in wealth will eventually benefit the poor, (2) incentive effects—inequality is necessary to encourage competition and to provide incentives for innovation, and (3) social stability—the different ranks in wealth distribution ensure peace and stability in society ( Walraevens 2021 , 3–6). The famous Kuznets curve ( Kuznets 1955 ), shaped like an inverted U-relationship between growth and inequality (as per capita income increases), seemed to reinforce this view. 9

Developed in the 1950s and 1960s, the so-called classical approach followed a similar line of thinking, based on arguments related to savings and incentives. The prominent work by Kaldor (1956) suggests a positive link between inequality and growth via saving rates, based on the assumption that the higher the level of income, the higher is the marginal propensity to save ( Aghion, Caroli, and García-Peñalosa 1999 , 1620). At the core of this assumption that the rich have a higher marginal propensity to save relative to the poor are two hypotheses: (1) consumption smoothing cannot occur unless the subsistence level of consumption is achieved, and therefore the poor cannot save, and (2) the possibility to save is conditioned by the previous generations, which leads to a concentration of savings in rich households ( Thorbecke and Charumilind 2002 , 1483).

Under this assumption, the redistribution of resources toward the rich leads to higher savings, which, in turn, improves growth via investment. This link is particularly important if one considers limited borrowing possibilities, initial setup costs, and the large investments involved in risky and high-return opportunities ( Aghion, Caroli, and García-Peñalosa 1999 , 1620; Voitchovsky 2011 , 558). Big investment projects involve large sunk costs, and therefore investment relies on the concentration of wealth in individuals to be able to afford them.

A second argument drew on the role of incentives and on the trade-off between efficiency and social justice mentioned earlier ( Aghion, Caroli, and García-Peñalosa 1999 , 1620). At the microlevel, in a simple moral hazard model, if output depends on unobserved effort, then setting a constant reward (in the form of wage) discourages effort, whereas linking the reward to output can be inefficient due to agents’ risk aversion. The same argument maintains at the aggregate level, assuming identical agents and/or perfect capital markets. As explained by Aghion, Caroli, and García-Peñalosa (1999 , 1620), redistribution will have a direct negative effect on growth as well as a negative indirect effect through the reduction in the incentives to accumulate wealth (resulting from redistribution through income tax).

High inequality has a negative effect on growth

Credit market imperfections and fertility.

The effects of inequality on growth via credit market imperfections and via fertility are linked by their focus on the circumstances of the poor and on human capital investment ( Voitchovsky 2011 ). The first channel addresses the impact of credit imperfections on investment decisions. If one considers the high fixed costs associated with, for instance, education, limitations on the access to credit may lead to underinvestment in human capital, which implies a negative impact on growth ( Neves and Silva 2014 , 3). This was the argument resulting from the Galor and Zeira (1993) model. Assuming that credit markets are imperfect and that investment in human capital is indivisible, they conclude that the distribution of wealth has an impact on aggregate investment in human capital and therefore on growth, both in the short and in the long run.

The reasoning behind the link between inequality and growth through fertility was similar. Poor families might not have the resources to invest in their children's education and, thus, their income depends on having bigger families; for richer families, it might be optimal to invest more in education and, consequently, to have fewer children ( Gründler and Scheuermeyer 2018 , 295). In this line of thinking, de la Croix and Doepke (2003) argued that a high fertility differential between the rich and the poor lowered average education. Thus, inequality leads to lower levels of human capital accumulation via the increased fertility differential and, therefore, to lower growth.

Taxation and regulatory policies

Seminal work by Alesina and Rodrik (1994) as well as Persson and Tabellini (1994) pointed to a negative link between inequality and growth through government expenditure and taxation, combining endogenous growth theory with political economy insights. They proposed two different mechanisms that Perotti (1996 , 151) termed “political” and “economic,” respectively. The Alesina and Rodrik (1994) model drew on the median voter theorem and considered tax revenues equally distributed among all individuals. Given that the tax rate is proportional to income, individuals with a lower share of capital income (relative to labor income) prefer higher taxes. Thus, the more equitable the distribution in the economy, the better endowed is the median voter, and the lower the equilibrium level of taxation. A lower rate of tax corresponds to a higher growth rate, which led them to conclude that there is an inverse relationship between inequality and subsequent economic growth.

Persson and Tabellini (1994) reached the same conclusion considering the role of incentives for productive accumulation and for growth. According to them, the incentives necessary for private savings and investment rely on individuals’ ability to “appropriate privately the fruits of their efforts” ( Persson and Tabellini 1994 , 600), which are in turn influenced by tax and regulatory policies. Inequality gives rise to policies that do not protect property rights or allow full appropriation of returns to investment and is therefore associated with lower economic growth.

Still, this result was defied by Li and Zou (1998) . They offered a more general framework than that proposed by Alesina and Rodrik (1994) , considering that government spending could be directed not only to production services—which entered the production function—but also to consumption services—which entered the utility function. Adding this extension, they showed that a more equal distribution could lead to lower growth via higher taxation and that the effect of income inequality on growth is, therefore, ambiguous.

The view outlined in Alesina and Rodrik (1994) and in Persson and Tabellini (1994) was also challenged by an alternative perspective suggesting that redistributive policies might also have a positive effect on growth in the presence of imperfect credit and insurance markets and that the popular support for these policies decreases with inequality ( Bénabou 2000 ). When combined, these two mechanisms could lead to multiple steady states, while the correlation with growth depends on the balance between incentive distortions and credit constraints ( Neves and Silva 2014 , 4). Voitchovsky (2011 , 556) lists the criticism toward the median voter argument and highlights how the channel through redistribution does not gather consensus.

The structure of demand

Zweimüller (2000) described the role of redistribution on growth through innovation. Building on the assumption of hierarchical preferences, the distribution of income affects the structure of demand: poor people spend mainly on basic needs whereas rich people spend on luxury goods. According to the author, inequality affects growth through its effect on the time path faced by an innovator. When a new and expensive good is introduced in the market, only rich consumers can afford it, until the increasing demand drives the price–wage ratio down (due to economies of scale), opening up the market to mass consumers ( Voitchovsky 2011 , 557). The optimal consumption levels of those affected by redistribution dictate the overall effect of changes in income inequality on long-run growth ( Zweimüller 2000 ). An earlier study by Murphy, Shleifer, and Vishny (1989) had already highlighted the importance of the middle class to the consumption of domestic manufactures and, therefore, to industrialization.

Sociopolitical instability and rent seeking

Another group of studies suggested a link between inequality and growth through sociopolitical instability, drawing attention to the effects on property rights. According to Alesina and Perotti (1996) , social unrest—resulting from social discontent caused by income inequality—can lead to an increasing probability of political violence as well as policy uncertainty and threats to property rights, which, in turn, have a negative impact on investment and thus on growth. Keefer and Knack (2002) claimed that income inequality leads to instability in government policies, namely those related to security of property rights, which affects the decisions of economic actors, and consequently slows the rate of growth. Relatedly, the Glaeser, Scheinkman, and Shleifer (2003) model showed a detrimental effect of inequality on property rights through the subversion of political regulatory and legal institutions by the rich for their own benefit.

The effect depends

Finally, we highlight contributions suggesting that different mechanisms might be present at different points. Galor and Moav (2004) proposed a unified theory between the credit market imperfections and the saving rate channels described earlier. According to them, the positive effect of inequality on growth suggested by classical theories corresponded to early stages of industrialization when physical capital accumulation is the primary driver of economic growth. However, at later stages, human capital accumulation becomes the main determinant of growth and credit constraints are largely binding, which explains the negative link between inequality and growth through credit market imperfections. As credit constraints become less binding due to wage increases, the aggregate effect of income distribution on growth is less significant.

A decade later, Halter, Oechslin, and Zweimüller (2014) presented a parsimonious theoretical model that takes into account both a short-term and a long-term effect of asset inequality. According to them, the short-term effect is positive and it occurs through an economic channel, whereas the long-term effect is negative and stems from a political economy channel.

How Inequality Affects Education and Health

Inequality can have both positive and negative effects on education.

While the literature examining the effects of education on inequality is extensive, the same is not true for studies looking at the other direction of causality. We distinguish between the arguments on the effects of inequality through expenditure on education and through school enrolment and attainment.

The provision of education depends on the willingness of citizens to redistribute resources via taxation, in line with Alesina and Rodrik (1994) and Perotti (1996 ). According to this political economy mechanism, increasing inequality will lead to lower availability of resources, as the rich will prefer not to contribute to public education, favoring private schools ( Mayer 2001 , 5). 10 Gutiérrez and Tanaka (2009) modeled the effect of inequality on school enrolment, and the preferred tax rate and expenditure per student focusing on parents’ decisions in developing countries. According to the authors, beyond a certain level of inequality, there is no longer support for public education. The model shows that, when considering the fact that parents can make a choice of sending their children either to work or to private or public schools, high inequality results in exiting public education, which has implications for the tax rate and expenditure per student. 11

According to the credit market imperfections’ channel discussed in section “How Inequality Affects Growth,” inequality creates obstacles in terms of access to education. In the presence of imperfect credit markets, the distribution of wealth affects the aggregate investment in human capital ( Galor and Zeira 1993 ; García-Peñalosa 1995 ). Additionally, inequality can affect enrolment by determining the number of poor who are able to substitute the return of child labor for school attendance ( Gutiérrez and Tanaka 2009 , 56). The Tanaka (2003) model shows that in contexts of high inequality, there is low support for public provision of schooling, which, in equilibrium, leads to a higher level of child labor.

The expected returns to the family from schooling will also affect the demand for education, as educated children are likely to have higher future income ( Birdsall 1999 , 17). If inequality is induced in part by increased returns to schooling, then there will be an incentive for children to stay in school and one could expect a positive relationship between an increase in inequality and educational attainment ( Mayer 2001 ; Thorbecke and Charumilind 2002 ; Dabla-Norris et al. 2015 ). 12

Inequality negatively affects health

The interest in understanding how income inequality affects health has instigated a broad range of work both in economics and in the fields of public health and sociology, 13 and different hypotheses are available. Generally, they suggest that inequality negatively affects health. Following O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti (2015) and Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding (2011) , we distinguish between hypotheses that imply that the health of all individuals is affected and those that do not require that the health of every individual in society is under threat. 14

The first group of hypotheses proposes three different channels: public goods provision, social capital, and violent crime. 15 The effect through public goods provision can be negative or positive ( Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding 2011 , 390). There will be a negative effect if inequality causes a reduction in the average value of publicly provided goods due to more heterogeneous preferences or if it enables the rich to acquire more political influence and, consequently, to pressure for a reduction in public spending on health. However, it can also be positive, given that as inequality increases among voters, the median voter will tend to support spending on health.

The effect through social capital builds on the assumption that income inequality leads to decreased social cohesion and, therefore, affects health through social 16 and psychosocial support, mechanisms of informal insurance, and diffusion of information ( O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti 2015 , 1501). Low trust can lead to disbelief about the improvements in health via public spending and links to higher mortality via smaller friendship networks as well ( Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding 2011 , 390). Finally, although only a small percentage of deaths in developed countries results from violent crime, Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding (2011 , 389) highlight the potentially larger secondary effects via increased stress about experiencing crime in the future. 17

In the second group of hypotheses, health depends on income at the individual level. The Wagstaff and van Doorslaer (2000) seminal review describes different interpretations. First, the absolute income hypothesis, which was also termed the “income artefact” hypothesis, suggests that the observed correlation between inequality and health is a result of the concave relationship between income and health; that is, the health gains of an additional unit of income are diminishing in an individual's income level. The term “artefact” applies to the fact that a redistribution of income leads to an increase in average population health even though there is no effect on the health of any individual, given their income. Second, the relative income hypothesis builds on the idea that psychosocial effects that result from individuals comparing their income with that of others (the mean income of the population or the community) affect health. Third, the deprivation hypothesis is a variation of the relative income hypothesis, and it argues that the crucial aspect is the extent of deprivation measured by the income gap. Fourth, and related, the relative position hypothesis states that what is important is the position of the individual in the income distribution.

How Inequality Affects Democratic Governance

In this section, we delve more deeply into the relationship between inequality and governance outcomes, democracy in particular, which have attracted considerable attention, especially within political economy and political science (see Bermeo 2009 ; Karl 2000 ). We start by focusing on the effects on democratic stability and democratic transition and then zoom in on the effects on political participation.

First, we refer back to the link between inequality and growth through political instability and social conflict described in section “High inequality has a negative effect on growth”. As highlighted by Fukuyama (2011 , 84), “[a] more likely reason why inequality is bad for growth is directly political: highly unequal countries are polarized between rich and poor, and the resulting social conflict destabilizes them, undermines democratic legitimacy, and reduces economic growth.” The summary in Thorbecke and Charumilind (2002 , 1486) suggests two main mechanisms: the relative deprivation hypothesis and resource mobilization. According to the first, discontent resulting from the gap between individual expected and achieved well-being leads to collective political violence. Inequality might deepen the grievances of certain groups or reduce the opportunity cost of engaging in violent conflict ( Dabla-Norris et al. 2015 , 9). Nevertheless, the second mechanism points to the ability of dissident groups to organize themselves as the key element.

The theoretical literature largely suggests negative effects of inequality on the likelihood of transition to and stability of democracy. It attributes an important role to democratic values and access to education, which are more likely to characterize citizens and the situation in equal societies, and to the middle class, which is more likely to promote tolerance and avoid extremist positions ( Houle 2015 , 145).

Two of the most prominent arguments for the link between inequality and democracy were presented in Boix (2003) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) . 18 The former argues that increasing levels of economic equality lead to a higher probability of democracy through redistribution. According to the theoretical predictions, the pressure for redistribution from the poor decreases with higher levels of equality, which means that a turn to democracy would be less costly for the holders of the most productive assets; that is, the payment of tax is less costly than repression.

The Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) predictions indicate a nonlinear, inverted U-shaped relationship. On the one hand, greater intergroup inequality increases the appeal of a revolution for citizens to increase their share in the income of the economy, thus increasing the likelihood of democracy. On the other hand, higher inequality also means higher aversion to democracy by elites as their tax burden is greater, thus discouraging democratization. Accordingly, the authors suggested that, for high levels of equality, there is no incentive for citizens to challenge the system and the interests of the elites are preserved. In societies with high levels of inequality, citizens try to rise up against the system, but this meets great repression from the elite, leading to a repressive non-democracy or a revolution, in certain cases. Therefore, the likelihood of democracy is higher for middle levels of inequality.

However, Houle (2009) highlighted three problems with these theories. First, they do not apply to transitions that are driven from above (e.g., from intra-elite competition). Second, the net effect of inequality is ambiguous because it makes redistribution more costly for the elites but, at the same time, it increases the population's demand for regime change. Finally, they ignore collective action problems and the challenges of mobilizing the population. More recently, Ansell and Samuels (2010) departed from Boix (2003) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) and proposed a contractarian approach that placed the focus on the citizens’ demand for protection against expropriation. According to these authors, democracy emerges from land equality and income inequality.

We briefly refer to a related group of studies examining the link from inequality to institutional quality and refer to Chong and Gradstein (2019) for details. Chong and Gradstein (2007 , 2019 ) argue that there is double causality: while inequality leads to subversion of institutions through the political power of the elite, poor institutional quality also causes a higher level of inequality. Furthermore, Kotschy and Sunde (2017) have proposed that inequality interacts with political institutions in shaping institutional quality. Some have also suggested that a link exists between inequality and corruption, via self-reinforcing mechanisms and social norms (e.g., Jong-sung and Khagram 2005 ) as well as via low trust (e.g., Rothstein and Uslaner 2005 ). 19

Finally, a strand of studies in political science has argued that there is a link between inequality and political participation. As reviewed in Solt (2008) , the theoretical predictions lead to different possible outcomes of economic inequality on political engagement 20 : a negative effect, a positive effect, or an effect that depends on the level of income of the individual. The first outcome is a result of the concentration of power: societies that are more unequal have a higher concentration of power, which has implications for how the issues that separate the rich from the poor are addressed in the political sphere. The rich will have a lower need to engage in the political process whereas the poor will feel removed from politics. The prediction of a positive effect results from the fact that the divergence in the views of the rich and the poor will be more apparent in societies with higher inequality, which should lead to higher participation in the political process. Finally, the last prediction hinges on the fact that political engagement entails the use of resources. Thus, with higher levels of inequality, one should expect greater engagement from the rich, who have more resources available, and lower political engagement from the poor. 21

We now move on to discuss the main insights from empirical analyses following the structure of the previous section. Although we focus here on cross-country analysis, which makes up a significant part of the evidence base, we also refer to studies examining these links at the regional level, especially in the United States.

Direct link

where |$g$| is the average annual growth rate, frequently measured as the log difference of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita; INEQ is a measure of income inequality (usually the Gini coefficient); Z m is a set of other variables commonly used in standard growth regressions; and u is the usual error term. This was then estimated, typically using basic ordinary least squares. To avoid reverse causation, inequality was measured at the beginning of the time span for growth, which usually considers a period of twenty to thirty years, and in some cases, authors employed instrumental variables to address endogeneity concerns.

Summary of results from selected empirical work testing the link between inequality and growth

| General finding . | Reference . | Data (no. countries; period) . | Measure of inequality . | Data source . | Data structure; estimation method(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative effect | = 46/70; 1960–1985 | Gini for land and income | ; | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |

| = 56; 1960–1985 | Pre-tax income share accruing to the third quintile (note: measure of equality) | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |||

| = 74/81; 1970–1978 | Coefficient of variation; Theil's index; Gini; share of income of the poorest 40% to the share of income of the richest 20% | United Nations Indicator of Social Development; ; | Cross-section; OLS, WLS, 2SLS | ||

| ) | = 67; 1960–1985 | Combined share of the third and fourth quintiles | ; | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |

| = 31; 1970–2010 | Gini; bottom inequality; top inequality | OECD income distribution dataset | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| = 153; 1960–2009 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| = 164; 1965–2014 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; two-step Sys-GMM | ||

| Positive effect | = 46; 1960–1990 | Gini | DS | Panel; FE, RE | |

| = 45; 1966–1995 | Gini | DS | Panel; FE, RE, Diff-GMM | ||

| = 123; 1960–2010 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; LSDV | ||

| It depends | |||||

| Controls | = 87/66; 1960–1992 | Gini; land distribution | DS | Cross-section; OLS | |

| Level of income | = 84; 1965–1995 | Gini; quintile shares | DS | Panel; 3SLS | |

| = 102/23; 1960–2000 | Gini; percentile ratios | WIID; LIS | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| Non-linear effects | = 45; 1965–1995 | Gini | DS | Panel; RE, GMM, Kernel regression | |

| Profile of inequality | = 21; 1975–2000 | Gini; top-end and bottom-end inequality | LIS | Panel; Sys-GMM | |

| Time | = 106; 1965–2005 | Gini | DS; WIID | Panel; Diff-GMM, Sys-GMM |

| General finding . | Reference . | Data (no. countries; period) . | Measure of inequality . | Data source . | Data structure; estimation method(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative effect | = 46/70; 1960–1985 | Gini for land and income | ; | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |

| = 56; 1960–1985 | Pre-tax income share accruing to the third quintile (note: measure of equality) | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |||

| = 74/81; 1970–1978 | Coefficient of variation; Theil's index; Gini; share of income of the poorest 40% to the share of income of the richest 20% | United Nations Indicator of Social Development; ; | Cross-section; OLS, WLS, 2SLS | ||

| ) | = 67; 1960–1985 | Combined share of the third and fourth quintiles | ; | Cross-section; OLS, 2SLS | |

| = 31; 1970–2010 | Gini; bottom inequality; top inequality | OECD income distribution dataset | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| = 153; 1960–2009 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| = 164; 1965–2014 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; two-step Sys-GMM | ||

| Positive effect | = 46; 1960–1990 | Gini | DS | Panel; FE, RE | |

| = 45; 1966–1995 | Gini | DS | Panel; FE, RE, Diff-GMM | ||

| = 123; 1960–2010 | Gini | SWIID | Panel; LSDV | ||

| It depends | |||||

| Controls | = 87/66; 1960–1992 | Gini; land distribution | DS | Cross-section; OLS | |

| Level of income | = 84; 1965–1995 | Gini; quintile shares | DS | Panel; 3SLS | |

| = 102/23; 1960–2000 | Gini; percentile ratios | WIID; LIS | Panel; Sys-GMM | ||

| Non-linear effects | = 45; 1965–1995 | Gini | DS | Panel; RE, GMM, Kernel regression | |

| Profile of inequality | = 21; 1975–2000 | Gini; top-end and bottom-end inequality | LIS | Panel; Sys-GMM | |

| Time | = 106; 1965–2005 | Gini | DS; WIID | Panel; Diff-GMM, Sys-GMM |

Notes : DS, Deininger and Squire (1996) ; LIS, Luxemburg Income Study; OLS, ordinary least squares; 2SLS, two-stage least squares; WLS, weighted least squares; 3SLS, three-stage least squares; LSDV, least squares dummy variable; FE, fixed effects; RE, random effects; Sys-GMM, system GMM; Diff-GMM, difference GMM.

Source : Authors’ elaboration, inspired from Cingano (2014) and Neves and Silva (2014) .

The aim was to estimate the coefficient of the income inequality variable δ , and most of these studies found a negative effect of inequality on growth. Persson and Tabellini (1994) obtained evidence for this effect using historical panel data and postwar cross-sectional analysis. Both the studies by Alesina and Rodrik (1994) and Clarke (1995) confirm this relationship using data from, among others, Jain (1975) and Lecaillon et al. (1984) . Clarke (1995) showed that this was robust to different measures and empirical specifications.

Given the challenges imposed by scarce data, some authors turned to an analysis between states in the United States. Partridge (1997) tested the robustness of the Persson and Tabellini (1994) findings, and the results suggested a positive link between inequality and subsequent growth when considering either the Gini coefficient or the share of income of the middle quintile. 23 Using tax data at the state level for the period 1940–1980, Panizza (2002) warned that both the data and the methodology used led to significant differences in the estimated coefficients for the effect of inequality on growth.

While the quality and reliability of the data are important challenges pertaining to early studies ( Knowles 2005 ), the introduction of an improved and expanded dataset by Deininger and Squire (1996) led to a surge in new studies using panel estimators. In contrast with previous work, these studies found a positive link between inequality and growth. Li and Zou (1998) showed that the coefficient for lagged Gini has a positive sign and is significant in most growth regressions. Forbes (2000) confirmed this result using similar data and generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators. 24 Still, using the same dataset, Deininger and Squire (1998) found a negative effect of initial income inequality on growth, although the coefficient lost significance once they add regional dummies to the specification.

Offering a starting point to reconcile the differing views, some studies have argued that the relationship between inequality and growth depends on other factors. According to Barro (2000) , the effect of inequality on growth depends on the level of income of the country: panel evidence suggests growth-enhancing effects of inequality in richer countries (GDP per capita: above $2,000, 1985 US dollars) and negative effects in poorer countries (below $2,000). Moreover, Banerjee and Duflo (2003) have raised concerns about the functional form used in the literature, arguing against using a linear specification for the relationship between inequality and growth. Their empirical work suggests an inverted U-shaped function between changes in inequality and lower future growth rates. Using a small sample of industrialized countries, Voitchovsky (2005) showed empirical support for the hypothesis that the profile of inequality influenced its relationship with growth: top-end inequality seems to have a positive effect and bottom-end inequality a negative effect.

The debate has continued in the literature ever since. Cingano (2014) lends support to a negative effect of inequality on growth using data from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) income distribution dataset. Additionally, the author suggests that reducing inequality by focusing on income disparities at the bottom of the income distribution has a greater positive effect on growth than by focusing on the top of the distribution. The Castelló-Climent (2010) results concur with this when considering the full sample of countries, but the results also find support for the argument of a differentiated effect according to the level of development. Halter, Oechslin, and Zweimüller (2014) argue that there is a time dimension to the link between inequality and growth, showing a positive coefficient for the current Gini coefficient and a negative coefficient for lagged Gini.

Some studies have used data from an additional dataset proposed by Solt (2009) , the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID). Yet, results also mirror the lack of consensus of earlier work. Applying system GMM, work from the International Monetary Fund finds a robust negative effect of inequality on growth ( Ostry, Berg, and Tsangarides 2014 ; Berg et al. 2018 ). While Gründler and Scheuermeyer (2018) concur with this result, Jäntti, Pirtillä, and Rönkkö (2020) raise concerns about the results in Berg et al. (2018) , resulting from the use of the SWIID dataset. El-Shagi and Shao (2019) criticize previous studies using system GMM and argue for the advantages of using a least-squares dummy variable estimation instead. In contrast, their results show a positive effect of inequality on growth over the medium term, primarily driven by market-based inequality.

Barro's (2000) view that the effect depends on the level of development in the country, confirmed in later analysis by the same author using the WIID dataset ( Barro 2008 ), has also been verified in some recent work. Gründler and Scheuermeyer (2018) see a negative and significant marginal effect of net inequality on growth in poor economies, which is, however, nonsignificant in high-income countries. 25

Channels of transmission

As discussed in section “How Inequality Affects Growth,” the theory proposes different channels through which inequality may affect growth. Although these specific mechanisms have received less attention in empirical work, we highlight the main findings, also summarized in table 2 .

Summary of empirical evidence on the different channels linking inequality and growth

| Hypothesis . | Channel . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|---|

| High inequality is growth enhancing | Savings | Some evidence using household micro-data, but mixed results using cross-country aggregate data ( , 1482). rejects this hypothesis. |

| High inequality has a negative effect on growth | Credit market imperfections | Support in , to some extent in ) and in . |

| Fertility | Confirmed by , ), , and . | |

| Government expenditure and taxation | The fiscal policy channel received less support by ) and it was rejected by . showed support for this hypothesis in the short run but not in the long run. | |

| Structure of demand | No specific empirical evidence on this channel. | |

| Sociopolitical instability and rent seeking | Support in ), , and . |

| Hypothesis . | Channel . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|---|

| High inequality is growth enhancing | Savings | Some evidence using household micro-data, but mixed results using cross-country aggregate data ( , 1482). rejects this hypothesis. |

| High inequality has a negative effect on growth | Credit market imperfections | Support in , to some extent in ) and in . |

| Fertility | Confirmed by , ), , and . | |

| Government expenditure and taxation | The fiscal policy channel received less support by ) and it was rejected by . showed support for this hypothesis in the short run but not in the long run. | |

| Structure of demand | No specific empirical evidence on this channel. | |

| Sociopolitical instability and rent seeking | Support in ), , and . |

Starting with the savings channel, while there is evidence of a positive link between inequality and personal savings when using household micro-data, studies based on cross-country aggregate data have found mixed results (see references in Thorbecke and Charumilind, 2002 ). Barro (2000) found that the investment ratio does not depend significantly on inequality. The channel via market imperfections and borrowing constraints found support in Deininger and Squire (1998) , who added that the effect through the investment in human capital seems more important than that via physical capital, as well as to some extent in Perotti (1996 ). 26 This channel also suggests that asset inequality matters for growth ( Ravallion 2001 , 1810), shown in both Birdsall and Londoño (1997) and Deininger and Olinto (2000) .

Moreover, there is published support for the channels related to sociopolitical instability ( Perotti 1996 ). Using data from a sample of seventy-one countries over the period 1960–1985, Alesina and Perotti (1996) found that a wealthy middle class is associated with lower levels of political instability, conducive to higher investment. Keefer and Knack (2002) showed evidence of a negative effect of inequality on growth and suggested that property rights are an important channel for this relationship.

Perotti (1996 ) confirmed the link between inequality and growth via fertility. Testing the same hypothesis, de la Croix and Doepke (2003) used Deininger and Squire's (1996) improved dataset and showed that the negative and significant effect of initial inequality on subsequent growth does not survive the inclusion of the differential fertility variable, which is negative and significant. They interpret this as meaning that the differential fertility is an important factor explaining the link between inequality and growth.

The fiscal policy channel received less support by Perotti (1996 ) while Persson and Tabellini (1994) also obtained coefficients with the expected sign but statistically insignificant for the links from inequality to redistributive policies and from redistribution to growth. Sylwester (2000) showed results from cross-country analysis that indicated that higher inequality is associated with higher subsequent expenditures for public education relative to GDP, which in turn has a negative effect on current growth but a long-term positive impact.

Recent studies have shown evidence that corroborates the theoretical effects via human capital accumulation ( Berg et al. 2018 ), via credit market imperfections ( Gründler and Scheuermeyer 2018 ), and via fertility ( Berg et al. 2018 ; Gründler and Scheuermeyer 2018 ) as channels through which inequality affects growth. Using data from twenty-one OECD countries over the period 1870–2011, Madsen, Islam, and Doucouliagos (2018) find support for the hypothesis that income inequality affects growth through different channels, namely savings, investment, education, and ideas production. Additionally, they concur with the arguments on differentiated effects. Although the negative impacts are significant in financially underdeveloped countries, there is little effect of inequality on the four outcomes in countries with highly developed financial markets.

Education and Health

In a recent paper, Castells-Quintana, Royuela, and Thiel (2019) estimated the effects of the Gini coefficient on the human development index (HDI) and found a negative effect in the long run, whereas in the short run the results change for different components of the index: a positive effect on income and a negative effect on educational outcomes. Moreover, they concur with the aforementioned studies that found distinct effects depending on the level of development. We are not aware of any other studies pursuing a similar analysis for the HDI, but in the remainder of this section, we discuss the empirical results on the link between inequality and education and health. We summarize the main conclusions in table 3 .

Summary of empirical evidence on the different hypotheses on the effects of inequality on education and health

| Outcome . | Effect . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Inequality affects expenditure on education | In contrast with theory, suggests that a high level of inequality is correlated with higher spending for public education. |

| Inequality affects education enrolment and attainment | Several studies find a negative link between inequality and secondary school enrolment ( ; ; ; ; ; ). A study from the United States links an increase in inequality with an increase in the gap in the educational attainment between rich and poor ( ). | |

| Health | Inequality affects the health of all individuals | There is strong support from Wilkinson and Pickett in different studies ( ; ) and weak support in . Concerns have been raised in reviews by ), , , and . |

| Inequality affects the population health but not necessarily of all individuals | Strong support exists for the absolute income hypothesis, resulting from the concave relationship between average income and average health ( ). | |

| No evidence exists for the relative income hypothesis; that is, that there is an effect on health resulting from individuals comparing their income with that of others ( ). | ||

| The hypothesis that what matters is the relative position of the individual in the income distribution has not been tested ( ). |

| Outcome . | Effect . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Inequality affects expenditure on education | In contrast with theory, suggests that a high level of inequality is correlated with higher spending for public education. |

| Inequality affects education enrolment and attainment | Several studies find a negative link between inequality and secondary school enrolment ( ; ; ; ; ; ). A study from the United States links an increase in inequality with an increase in the gap in the educational attainment between rich and poor ( ). | |

| Health | Inequality affects the health of all individuals | There is strong support from Wilkinson and Pickett in different studies ( ; ) and weak support in . Concerns have been raised in reviews by ), , , and . |

| Inequality affects the population health but not necessarily of all individuals | Strong support exists for the absolute income hypothesis, resulting from the concave relationship between average income and average health ( ). | |

| No evidence exists for the relative income hypothesis; that is, that there is an effect on health resulting from individuals comparing their income with that of others ( ). | ||

| The hypothesis that what matters is the relative position of the individual in the income distribution has not been tested ( ). |

Although there is an extensive body of empirical literature examining education as a determinant of income inequality, the evidence on the link from income inequality to educational outcomes is scarcer ( Thorbecke and Charumilind 2002 , 1488; Gutiérrez and Tanaka 2009 , 56). However, there is evidence that income inequality is reproduced in inequality in education, both in terms of achievements in primary and secondary school and in terms of access to tertiary education (see Buchmann and Hannum 2001 and references in Stewart 2016 ).

Regarding the links proposed in the theoretical work reviewed in the previous section, Sylwester (2000) reported a positive link between inequality and public expenditures on education. Considering the demand side, some studies have found a negative link between inequality and secondary school enrolment. Flug, Spilimbergo, and Wachtenheim (1998) and Easterly (2007) used cross-country analysis, while Esposito and Villaseñor (2018) used data from the 2010 Mexican Census. The study by Madsen, Islam, and Doucouliagos (2018) shows a negative impact of inequality on the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary school enrolment rate in financially underdeveloped countries (using a sample from OECD). Concurring with these findings, Berg et al. (2018) show a negative correlation between inequality and human capital, measured as the average years of primary and secondary schooling. Checchi (2003) provided support for the link between inequality and growth via borrowing constraints and showed evidence of a negative effect of inequality on access to secondary education. 27 Finally, using data from the United States for the period 1970–1990, Mayer (2001) found that the increase in inequality aggravates the gap in educational attainment between rich and poor children.

Given that the literature is extensive and stems from different fields of literature (including, public health), we summarize the main conclusions from different reviews, which distinguish between aggregate level and multilevel studies as well as cross-country and within-country empirical analyses. 28 Wagstaff and van Doorslaer (2000) highlighted that studies at the population level are limited in what they can reveal about the effects on individual health and that data at the individual level are required to disentangle the effects of the different hypotheses described in section “Inequality negatively affects health.” Still, existing evidence on these different channels remains inconclusive.

Lynch et al. (2004) found weak support for a direct effect of income inequality on health, although inequality contributes directly to some health outcomes (e.g., homicides). Furthermore, they underlined that the reduction of income inequality via income rises for the more disadvantaged contributes to improved health of these individuals and increases average population health. Rowlingson (2011) concludes that there is some evidence of an independent effect on health and social problems, but in line with Subramanian and Kawachi (2004) , also highlights the lack of consensus in the results and the need for further work. Still, from a systematic review of 155 published peer-review studies, Wilkinson and Pickett (2006) concluded that there is a link between greater income inequality and poorer health. Almost ten years later, the authors provided further support for the existence of a causal link between income inequality and health and reinforced their argument of the size of status and social class differences as an important mechanism ( Pickett and Wilkinson 2015 ).

The conclusions from the economics literature have pointed to no evidence of a causal relationship ( Nolan and Valenzuela 2019 ). From a detailed review of the literature, Deaton (2003 , 150) argued that “the stories about income inequality affecting health are stronger than the evidence” and that there is no robust evidence showing that income inequality in itself is an important determinant of population health, although it had effects through poverty. The review in Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding (2011) concurred. However, they warned that given the data challenges and the limitations of the methods used to test the link between inequality and health, one should not jump to definite conclusions. Focusing on morbidity and mortality, the comprehensive review of empirical literature by O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti (2015) concludes that even though population health is negatively associated with income inequality, there is little evidence to support the hypothesis of a negative impact of income inequality on health.

We start this section by noting that the focus on voting underlying the political economy mechanism linking inequality and growth suggests that the effects should be observed in democracies ( Houle 2015 , 143). Thus, some of the early empirical literature on the relationship between inequality and growth also tested whether this effect was dependent on the regime type (e.g., see Alesina and Rodrik 1994 ; Persson and Tabellini 1994 ; Clarke 1995 ; Perotti 1996 ; Deininger and Squire 1998 ).

The results were mixed. Persson and Tabellini (1994) suggested that the negative link between inequality and growth is only present in democracies and that the transmission channel through government redistributive policies should be further investigated. However, Perotti (1996 ) counterargued that, although the data showed a stronger relationship between equality and growth in democracies, the effect of the democracy variable did not appear to be robust. Further criticism was advanced by Knack and Keefer (1997) , who, after some regime reclassification and deletion of doubtful observations, concluded that there is no evidence of a differential effect of inequality on growth in democracies and non-democracies. Østby (2013) and Stewart (2016) argued that there is compelling evidence for the link between horizontal inequality (i.e., inequality among groups) and civil conflict as well as other forms of group violence. However, more recent reviews suggest that the evidence on the link between inequality and political violence is mixed ( Lengfelder 2019 ).

We now turn to what the empirical evidence on the government outcomes described in section “How inequality affects democratic governance” shows, and summarize the main conclusions in table 4 . Using data from two panels on the periods 1950–1990 and 1850–1980, Boix (2003) showed empirical evidence for a positive link between equality (proxied by an adjusted Gini coefficient) and democratization and, particularly, democratic consolidation. In an extension of this analysis, Boix and Stokes (2003) concluded that economic equality, proxied by farm ownership (distribution of agricultural property) and literacy rates (quality of human capital), has a positive effect on both the probability of a democratic transition and the stability of democracy.

Summary of empirical evidence on the effects of inequality on different governance outcomes

| Outcome . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|

| Democracy | Mixed results are found for the effect through redistributive policies. While some studies find support for a negative link between inequality and democratization ( ) and democratic consolidation ( ), others have challenged the robustness of the effect of inequality on democracy (e.g., ; ) and suggested that this effect is conditional on certain factors, such as the state of the macroeconomy ( ). |

| Institutional quality | There is some evidence of a negative link between inequality and institutional quality ( ; ), and corruption in particular ( ), but there is a need for further research ( ). |

| Political participation | Recent evidence from developed economies suggests a negative effect of inequality on political participation ( ; ; ), support for democracy ( ; ), and political inequality ( ), but there is limited support for an impact on electoral turnout ( ; ). |

| Outcome . | Empirical evidence . |

|---|---|

| Democracy | Mixed results are found for the effect through redistributive policies. While some studies find support for a negative link between inequality and democratization ( ) and democratic consolidation ( ), others have challenged the robustness of the effect of inequality on democracy (e.g., ; ) and suggested that this effect is conditional on certain factors, such as the state of the macroeconomy ( ). |

| Institutional quality | There is some evidence of a negative link between inequality and institutional quality ( ; ), and corruption in particular ( ), but there is a need for further research ( ). |

| Political participation | Recent evidence from developed economies suggests a negative effect of inequality on political participation ( ; ; ), support for democracy ( ; ), and political inequality ( ), but there is limited support for an impact on electoral turnout ( ; ). |

Others found low support for a significant link between the two (e.g., Bollen and Jackman 1985 ). 29 Barro (1999) showed a negative, but only marginally significant coefficient for the effect of inequality on democracy, proxied as electoral rights and civil liberties, for the period 1972–1995. However, when entered alongside the share of income accruing to the middle class, the coefficient is nonsignificant. The empirical analysis in Houle (2009) went against previous results on the negative link between inequality and democracy and showed a weak positive and nonsignificant relationship. Using the capital share of the value added in the industrial sector as a measure of inequality to overcome the data limitations in previous studies, the author also did not find support for Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) ’s inverted U-shaped relationship but rather for a weakly U-shaped one.

More recently, Haggard and Kaufman (2012) used causal process observation to examine the association between inequality and transitions to and from democratic rule and found limited evidence supporting the link via distributive conflict between elites and masses. Additionally, the evidence in Scheve and Stasavage (2017) does not support the hypothesis of a link between wealth inequality and democracy. Dorsch and Maarek (2020) offer an explanation for the abundancy of null results found for the link between inequality and democratization, showing that higher levels of inequality are associated with higher probabilities of democratic improvements following economic downturns (“windows of opportunity”). However, following growth periods, the effect of inequality is null or small and negative.

Considering a broader approach to governance, we briefly refer to the literature linking inequality and institutional quality. 30 Both Easterly (2007) and Chong and Gradstein (2007 ) tested the causal relationship between these variables using an instrumental variables approach and system GMM methods, respectively, and found support for the effect of inequality on institutions. More recently, Kotschy and Sunde (2017) showed evidence of the importance of equality as a determinant of the effect of democratic institutions on institutional quality, measured by an index of economic freedom and an indicator of civil liberties. 31 It has also been shown that countries with more income inequality have more corruption ( Jong-Sung and Khagram 2005 ), and, in particular, survey evidence links perceptions of corruption and inequality to lower political trust ( Uslaner 2017 ).

Finally, there is evidence from advanced industrial democracies of a negative link between inequality and political participation ( Lengfelder 2019 ). Solt (2008) showed a negative effect of economic inequality on political engagement, namely political interest, the frequency of political discussion, and participation in elections among all citizens except the richest, using data from advanced industrial countries. Using cross-sectional data from OECD countries and within-country data for Germany and a range of methods, the recent study by Schäfer and Schwander (2019) finds support for the negative link between economic inequality and political participation. Relatedly, empirical work suggests that economic inequality harms support for democracy (e.g., Andersen 2012 ; Krieckhaus et al. 2014 ) and political inequality (e.g., Houle 2018 ). Still, there appears to be limited evidence of an effect of inequality on electoral turnout ( Stockemer and Scruggs 2012 ; Cancela and Geys 2016 ).

The lack of consensus in the literature, especially about the effect of inequality on growth, is notable. What explains this divergence, and what can be done to contribute to the existing knowledge? In this section, we discuss the key empirical challenges of estimating the effects of inequality: data quality and availability, conceptual and measurement issues, and the methodological difficulties of dealing with confounding variables and endogeneity.

Data quality and availability

Early studies drew on secondary datasets provided, for example, by the World Bank ( Jain 1975 ) or the International Labour Office ( Lecaillon et al. 1984 ). The expanded dataset proposed by Deininger and Squire (1996) was crucial in opening possibilities for panel methods. Additionally, databases offering secondary data compilations on income inequality provided by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, WIID (based on household surveys), and SWIID, developed by Solt (2020) and resulting from multiple imputations of the WIID data, have been frequently used in empirical studies. The World Inequality Database ( WID.world 2017 ) has emerged as an additional database providing data on income shares captured by top income groups.

Atkinson and Brandolini (2001 , 2009 ) and Ferreira, Lustig, and Teles (2015) offer comprehensive analyses on secondary datasets on income distribution, drawing attention to issues of data quality and consistency linked to differences in the definitions used, sources of data, and the processing used to obtain “ready-made” income distribution statistics. 32 Atkinson and Brandolini (2001 ) focused mainly on the Deininger and Squire dataset and on data for OECD member countries. Jenkins (2015) follows a similar line of reasoning and compares the WIID and the SWIID, noting that for the latter it is also critical to consider issues relating to the quality of imputations. Jäntti, Pirtillä, and Rönkkö (2020) stress that, in most developing countries, the actual redistribution is only rarely measured, so figures in the SWIID reflect questionable imputations.

As demonstrated in Atkinson and Brandolini (2001 , 2009 ) and Jenkins (2015) , issues of noncomparability have consequences for econometric analysis and for trends over time. Voitchovsky (2011 , 566) warns that data scarcity and limitations in terms of data availability may lead to a trade-off between sources of bias and precision in inequality studies. Ravallion (2001 , 1809) notes, however, that measurement errors, including those resulting from comparability problems, will have a greater impact on analyses that allow for country fixed-effects rather than on standard growth regressions given that the signal-to-noise ratio is likely to be low for changes in measured inequality.

The challenges are even more striking for tests that require data at the individual level, namely those related to the relative hypotheses linking inequality to health. These hypotheses also lead to questions about the appropriate reference groups—how they are defined and formed—as well as in terms of endogeneity, as the position of the individual in relation to the reference may be affected by group membership ( O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti 2015 , 1505).

Concept and measurement of inequality

Issues of concept and measurement are also consequential. 33 Atkinson and Brandolini (2001 ) provide a useful summary of eight parameters to be chosen when defining an income distribution, among which are the unit of observation, concept of resource (e.g., income versus expenditure), and tax treatment of income. These closely link to measurement choices. Different mechanisms require a specific concept of inequality and this should be reflected in the measure of inequality used in the empirical analysis ( Voitchovsky 2011 , 567). Additionally, different parts of the distribution receive importance depending on the inequality measure used, and even the concept of income is open to measurement issues ( Deaton 2003 , 135).

Knowles's (2005) account of the relationship between inequality and growth illustrates these concerns. The author warns that the results in previous studies should be regarded with some degree of caution given that they failed to measure inequality in a consistent manner, mixing measures of the distributions of income before and after tax and the distribution of expenditure. Considering six different measures of inequality (three Gini coefficients and three top ten income shares), a recent study by Blotevogel et al. (2020) shows that the choice of the inequality indicator has important implications for the results obtained in empirical analysis, namely when considering different transmission channels between inequality and growth. In terms of the link between inequality and democratic governance, there is a concern that frequently used measures do not capture interclass inequality, which precludes the testing of theoretical hypotheses that hinge on this ( Houle 2015 , 147).

Criticism has also been directed at specific measures, in particular the widely used Gini coefficient. In light of the observations above, Gini coefficients will provide different information depending on how they are calculated, for example, if based on net income or on gross income ( Houle 2015 , 147). Moreover, some have argued that the use of absolute rather than relative measures might better capture perceptions of inequality on the ground (e.g., Bosmans et al. 2014 ; Atkinson and Brandolini 2004 ; Niño-Zarazúa, Roope, and Tarp 2017 ).

Estimation methods

A review of empirical studies on the inequality–growth link highlights contrasting findings between the early cross-country studies and those that employed panel estimation techniques, after the Deininger and Squire (1998) dataset became available. Some explanations have been advanced for this divergence.

Measurement error may affect the estimation results in cross-country estimation (country- or regional-specific measurement error), and also in panel data estimation, given that inequality tends to be persistent over time; thus, this method relies on more limited time-series variation in the data. The coefficients in cross-country studies may be biased due to time-invariant omitted variables ( Voitchovsky 2011 , 565), while if we consider that inequality is related to underlying determinants of development that are persistent, then fixed-effect estimates may be biased upward when considering long-run effects ( Castells-Quintana, Royuela, and Thiel 2019 , 454).

Additional explanations included the argument for the misspecification of the linearity in the effect of inequality and growth ( Banerjee and Duflo 2003 ) and the suggestion that the two methods capture different time effects, given the short- and long-term lag structures in panel and cross-country analyses, respectively ( Voitchovsky 2011 , 565).

Finally, several concerns have been raised regarding the use of different instruments to tackle reverse causality in the relationship between inequality and growth (see Easterly 2007 ) as well as health ( O'Donnell, van Doorslaer, and van Ourti 2015 , 1505) and democracy ( Houle 2015 , 147). While different attempts have been made using instrumental variable approaches, finding a valid instrument for inequality is certainly not straightforward. Furthermore, even if GMM has often been used to try to tackle these issues, Roodman (2009) warns about the risk of instrument proliferation and the possibility for generating false-positive results. As an illustration, he reexamined the analysis in Forbes (2000) and raised concerns over the positive effect of inequality on growth found in the original paper.

This review combined the different theoretical hypotheses concerning the impact of inequality on three core socioeconomic and political outcomes in a simplified framework and highlighted the mixed empirical evidence. We summarize the main conclusions as follows. First, in line with previous findings, the debate on whether there is a positive or a negative effect on growth remains open, with recent studies mirroring the disagreement in decades of empirical work. With the exception of the classical approach, most of the transmission channels between inequality and growth point to a negative effect of inequality. However, the evidence from reduced-form equations is not consensual and the channels of transmission have received less attention.

Second, while there seems to be some consensus in the evidence that there is a negative link between inequality and secondary school enrolment, there is need for further research in terms of other education outcomes. Although theory generally points toward a negative effect of inequality on health, the existing evidence does not provide clear support to this relationship, in the economic literature in particular, and there is a lot to be uncovered in terms of the mechanisms of transmission at the individual level. Third, theoretical predictions and empirical evidence show mixed results for the effects of inequality on democracy and political participation.