Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

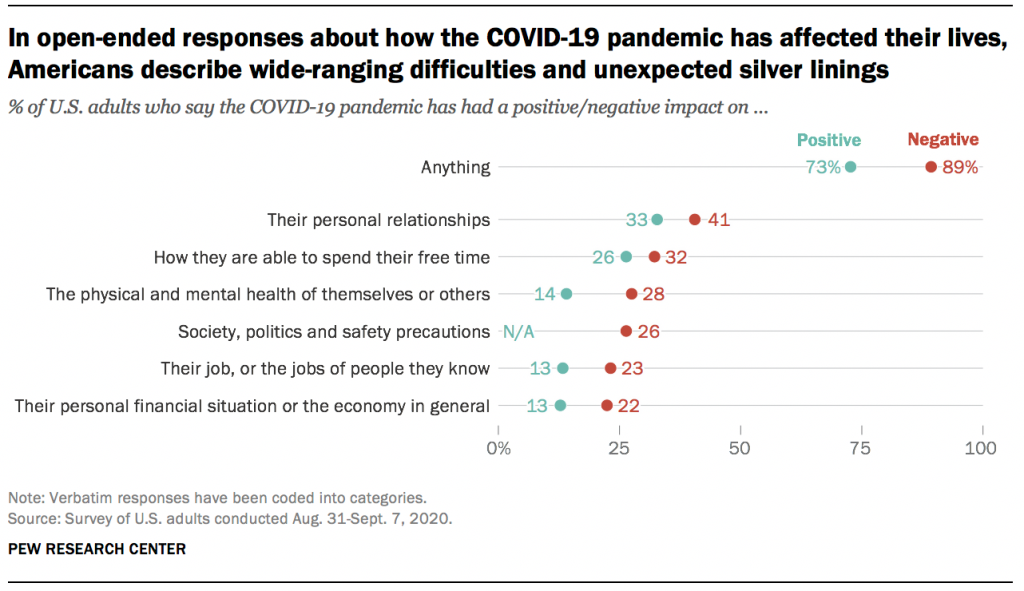

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 76, Issue 2

- COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1512-4471 Emily Long 1 ,

- Susan Patterson 1 ,

- Karen Maxwell 1 ,

- Carolyn Blake 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-4566 Raquel Bosó Pérez 1 ,

- Ruth Lewis 1 ,

- Mark McCann 1 ,

- Julie Riddell 1 ,

- Kathryn Skivington 1 ,

- Rachel Wilson-Lowe 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4409-6601 Kirstin R Mitchell 2

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- 2 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health & Wellbeing , University of Glasgow , Glasgow , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Emily Long, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G3 7HR, UK; emily.long{at}glasgow.ac.uk

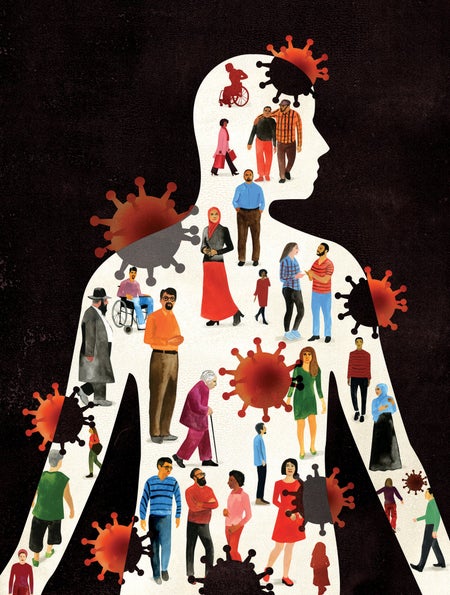

This essay examines key aspects of social relationships that were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It focuses explicitly on relational mechanisms of health and brings together theory and emerging evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic to make recommendations for future public health policy and recovery. We first provide an overview of the pandemic in the UK context, outlining the nature of the public health response. We then introduce four distinct domains of social relationships: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy, highlighting the mechanisms through which the pandemic and associated public health response drastically altered social interactions in each domain. Throughout the essay, the lens of health inequalities, and perspective of relationships as interconnecting elements in a broader system, is used to explore the varying impact of these disruptions. The essay concludes by providing recommendations for longer term recovery ensuring that the social relational cost of COVID-19 is adequately considered in efforts to rebuild.

- inequalities

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study. Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated or analysed for this essay.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216690

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Infectious disease pandemics, including SARS and COVID-19, demand intrapersonal behaviour change and present highly complex challenges for public health. 1 A pandemic of an airborne infection, spread easily through social contact, assails human relationships by drastically altering the ways through which humans interact. In this essay, we draw on theories of social relationships to examine specific ways in which relational mechanisms key to health and well-being were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Relational mechanisms refer to the processes between people that lead to change in health outcomes.

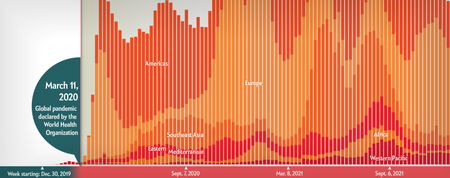

At the time of writing, the future surrounding COVID-19 was uncertain. Vaccine programmes were being rolled out in countries that could afford them, but new and more contagious variants of the virus were also being discovered. The recovery journey looked long, with continued disruption to social relationships. The social cost of COVID-19 was only just beginning to emerge, but the mental health impact was already considerable, 2 3 and the inequality of the health burden stark. 4 Knowledge of the epidemiology of COVID-19 accrued rapidly, but evidence of the most effective policy responses remained uncertain.

The initial response to COVID-19 in the UK was reactive and aimed at reducing mortality, with little time to consider the social implications, including for interpersonal and community relationships. The terminology of ‘social distancing’ quickly became entrenched both in public and policy discourse. This equation of physical distance with social distance was regrettable, since only physical proximity causes viral transmission, whereas many forms of social proximity (eg, conversations while walking outdoors) are minimal risk, and are crucial to maintaining relationships supportive of health and well-being.

The aim of this essay is to explore four key relational mechanisms that were impacted by the pandemic and associated restrictions: social networks, social support, social interaction and intimacy. We use relational theories and emerging research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic response to make three key recommendations: one regarding public health responses; and two regarding social recovery. Our understanding of these mechanisms stems from a ‘systems’ perspective which casts social relationships as interdependent elements within a connected whole. 5

Social networks

Social networks characterise the individuals and social connections that compose a system (such as a workplace, community or society). Social relationships range from spouses and partners, to coworkers, friends and acquaintances. They vary across many dimensions, including, for example, frequency of contact and emotional closeness. Social networks can be understood both in terms of the individuals and relationships that compose the network, as well as the overall network structure (eg, how many of your friends know each other).

Social networks show a tendency towards homophily, or a phenomenon of associating with individuals who are similar to self. 6 This is particularly true for ‘core’ network ties (eg, close friends), while more distant, sometimes called ‘weak’ ties tend to show more diversity. During the height of COVID-19 restrictions, face-to-face interactions were often reduced to core network members, such as partners, family members or, potentially, live-in roommates; some ‘weak’ ties were lost, and interactions became more limited to those closest. Given that peripheral, weaker social ties provide a diversity of resources, opinions and support, 7 COVID-19 likely resulted in networks that were smaller and more homogenous.

Such changes were not inevitable nor necessarily enduring, since social networks are also adaptive and responsive to change, in that a disruption to usual ways of interacting can be replaced by new ways of engaging (eg, Zoom). Yet, important inequalities exist, wherein networks and individual relationships within networks are not equally able to adapt to such changes. For example, individuals with a large number of newly established relationships (eg, university students) may have struggled to transfer these relationships online, resulting in lost contacts and a heightened risk of social isolation. This is consistent with research suggesting that young adults were the most likely to report a worsening of relationships during COVID-19, whereas older adults were the least likely to report a change. 8

Lastly, social connections give rise to emergent properties of social systems, 9 where a community-level phenomenon develops that cannot be attributed to any one member or portion of the network. For example, local area-based networks emerged due to geographic restrictions (eg, stay-at-home orders), resulting in increases in neighbourly support and local volunteering. 10 In fact, research suggests that relationships with neighbours displayed the largest net gain in ratings of relationship quality compared with a range of relationship types (eg, partner, colleague, friend). 8 Much of this was built from spontaneous individual interactions within local communities, which together contributed to the ‘community spirit’ that many experienced. 11 COVID-19 restrictions thus impacted the personal social networks and the structure of the larger networks within the society.

Social support

Social support, referring to the psychological and material resources provided through social interaction, is a critical mechanism through which social relationships benefit health. In fact, social support has been shown to be one of the most important resilience factors in the aftermath of stressful events. 12 In the context of COVID-19, the usual ways in which individuals interact and obtain social support have been severely disrupted.

One such disruption has been to opportunities for spontaneous social interactions. For example, conversations with colleagues in a break room offer an opportunity for socialising beyond one’s core social network, and these peripheral conversations can provide a form of social support. 13 14 A chance conversation may lead to advice helpful to coping with situations or seeking formal help. Thus, the absence of these spontaneous interactions may mean the reduction of indirect support-seeking opportunities. While direct support-seeking behaviour is more effective at eliciting support, it also requires significantly more effort and may be perceived as forceful and burdensome. 15 The shift to homeworking and closure of community venues reduced the number of opportunities for these spontaneous interactions to occur, and has, second, focused them locally. Consequently, individuals whose core networks are located elsewhere, or who live in communities where spontaneous interaction is less likely, have less opportunity to benefit from spontaneous in-person supportive interactions.

However, alongside this disruption, new opportunities to interact and obtain social support have arisen. The surge in community social support during the initial lockdown mirrored that often seen in response to adverse events (eg, natural disasters 16 ). COVID-19 restrictions that confined individuals to their local area also compelled them to focus their in-person efforts locally. Commentators on the initial lockdown in the UK remarked on extraordinary acts of generosity between individuals who belonged to the same community but were unknown to each other. However, research on adverse events also tells us that such community support is not necessarily maintained in the longer term. 16

Meanwhile, online forms of social support are not bound by geography, thus enabling interactions and social support to be received from a wider network of people. Formal online social support spaces (eg, support groups) existed well before COVID-19, but have vastly increased since. While online interactions can increase perceived social support, it is unclear whether remote communication technologies provide an effective substitute from in-person interaction during periods of social distancing. 17 18 It makes intuitive sense that the usefulness of online social support will vary by the type of support offered, degree of social interaction and ‘online communication skills’ of those taking part. Youth workers, for instance, have struggled to keep vulnerable youth engaged in online youth clubs, 19 despite others finding a positive association between amount of digital technology used by individuals during lockdown and perceived social support. 20 Other research has found that more frequent face-to-face contact and phone/video contact both related to lower levels of depression during the time period of March to August 2020, but the negative effect of a lack of contact was greater for those with higher levels of usual sociability. 21 Relatedly, important inequalities in social support exist, such that individuals who occupy more socially disadvantaged positions in society (eg, low socioeconomic status, older people) tend to have less access to social support, 22 potentially exacerbated by COVID-19.

Social and interactional norms

Interactional norms are key relational mechanisms which build trust, belonging and identity within and across groups in a system. Individuals in groups and societies apply meaning by ‘approving, arranging and redefining’ symbols of interaction. 23 A handshake, for instance, is a powerful symbol of trust and equality. Depending on context, not shaking hands may symbolise a failure to extend friendship, or a failure to reach agreement. The norms governing these symbols represent shared values and identity; and mutual understanding of these symbols enables individuals to achieve orderly interactions, establish supportive relationship accountability and connect socially. 24 25

Physical distancing measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 radically altered these norms of interaction, particularly those used to convey trust, affinity, empathy and respect (eg, hugging, physical comforting). 26 As epidemic waves rose and fell, the work to negotiate these norms required intense cognitive effort; previously taken-for-granted interactions were re-examined, factoring in current restriction levels, own and (assumed) others’ vulnerability and tolerance of risk. This created awkwardness, and uncertainty, for example, around how to bring closure to an in-person interaction or convey warmth. The instability in scripted ways of interacting created particular strain for individuals who already struggled to encode and decode interactions with others (eg, those who are deaf or have autism spectrum disorder); difficulties often intensified by mask wearing. 27

Large social gatherings—for example, weddings, school assemblies, sporting events—also present key opportunities for affirming and assimilating interactional norms, building cohesion and shared identity and facilitating cooperation across social groups. 28 Online ‘equivalents’ do not easily support ‘social-bonding’ activities such as singing and dancing, and rarely enable chance/spontaneous one-on-one conversations with peripheral/weaker network ties (see the Social networks section) which can help strengthen bonds across a larger network. The loss of large gatherings to celebrate rites of passage (eg, bar mitzvah, weddings) has additional relational costs since these events are performed by and for communities to reinforce belonging, and to assist in transitioning to new phases of life. 29 The loss of interaction with diverse others via community and large group gatherings also reduces intergroup contact, which may then tend towards more prejudiced outgroup attitudes. While online interaction can go some way to mimicking these interaction norms, there are key differences. A sense of anonymity, and lack of in-person emotional cues, tends to support norms of polarisation and aggression in expressing differences of opinion online. And while online platforms have potential to provide intergroup contact, the tendency of much social media to form homogeneous ‘echo chambers’ can serve to further reduce intergroup contact. 30 31

Intimacy relates to the feeling of emotional connection and closeness with other human beings. Emotional connection, through romantic, friendship or familial relationships, fulfils a basic human need 32 and strongly benefits health, including reduced stress levels, improved mental health, lowered blood pressure and reduced risk of heart disease. 32 33 Intimacy can be fostered through familiarity, feeling understood and feeling accepted by close others. 34

Intimacy via companionship and closeness is fundamental to mental well-being. Positively, the COVID-19 pandemic has offered opportunities for individuals to (re)connect and (re)strengthen close relationships within their household via quality time together, following closure of many usual external social activities. Research suggests that the first full UK lockdown period led to a net gain in the quality of steady relationships at a population level, 35 but amplified existing inequalities in relationship quality. 35 36 For some in single-person households, the absence of a companion became more conspicuous, leading to feelings of loneliness and lower mental well-being. 37 38 Additional pandemic-related relational strain 39 40 resulted, for some, in the initiation or intensification of domestic abuse. 41 42

Physical touch is another key aspect of intimacy, a fundamental human need crucial in maintaining and developing intimacy within close relationships. 34 Restrictions on social interactions severely restricted the number and range of people with whom physical affection was possible. The reduction in opportunity to give and receive affectionate physical touch was not experienced equally. Many of those living alone found themselves completely without physical contact for extended periods. The deprivation of physical touch is evidenced to take a heavy emotional toll. 43 Even in future, once physical expressions of affection can resume, new levels of anxiety over germs may introduce hesitancy into previously fluent blending of physical and verbal intimate social connections. 44

The pandemic also led to shifts in practices and norms around sexual relationship building and maintenance, as individuals adapted and sought alternative ways of enacting sexual intimacy. This too is important, given that intimate sexual activity has known benefits for health. 45 46 Given that social restrictions hinged on reducing household mixing, possibilities for partnered sexual activity were primarily guided by living arrangements. While those in cohabiting relationships could potentially continue as before, those who were single or in non-cohabiting relationships generally had restricted opportunities to maintain their sexual relationships. Pornography consumption and digital partners were reported to increase since lockdown. 47 However, online interactions are qualitatively different from in-person interactions and do not provide the same opportunities for physical intimacy.

Recommendations and conclusions

In the sections above we have outlined the ways in which COVID-19 has impacted social relationships, showing how relational mechanisms key to health have been undermined. While some of the damage might well self-repair after the pandemic, there are opportunities inherent in deliberative efforts to build back in ways that facilitate greater resilience in social and community relationships. We conclude by making three recommendations: one regarding public health responses to the pandemic; and two regarding social recovery.

Recommendation 1: explicitly count the relational cost of public health policies to control the pandemic

Effective handling of a pandemic recognises that social, economic and health concerns are intricately interwoven. It is clear that future research and policy attention must focus on the social consequences. As described above, policies which restrict physical mixing across households carry heavy and unequal relational costs. These include for individuals (eg, loss of intimate touch), dyads (eg, loss of warmth, comfort), networks (eg, restricted access to support) and communities (eg, loss of cohesion and identity). Such costs—and their unequal impact—should not be ignored in short-term efforts to control an epidemic. Some public health responses—restrictions on international holiday travel and highly efficient test and trace systems—have relatively small relational costs and should be prioritised. At a national level, an earlier move to proportionate restrictions, and investment in effective test and trace systems, may help prevent escalation of spread to the point where a national lockdown or tight restrictions became an inevitability. Where policies with relational costs are unavoidable, close attention should be paid to the unequal relational impact for those whose personal circumstances differ from normative assumptions of two adult families. This includes consideration of whether expectations are fair (eg, for those who live alone), whether restrictions on social events are equitable across age group, religious/ethnic groupings and social class, and also to ensure that the language promoted by such policies (eg, households; families) is not exclusionary. 48 49 Forethought to unequal impacts on social relationships should thus be integral to the work of epidemic preparedness teams.

Recommendation 2: intelligently balance online and offline ways of relating

A key ingredient for well-being is ‘getting together’ in a physical sense. This is fundamental to a human need for intimate touch, physical comfort, reinforcing interactional norms and providing practical support. Emerging evidence suggests that online ways of relating cannot simply replace physical interactions. But online interaction has many benefits and for some it offers connections that did not exist previously. In particular, online platforms provide new forms of support for those unable to access offline services because of mobility issues (eg, older people) or because they are geographically isolated from their support community (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) youth). Ultimately, multiple forms of online and offline social interactions are required to meet the needs of varying groups of people (eg, LGBTQ, older people). Future research and practice should aim to establish ways of using offline and online support in complementary and even synergistic ways, rather than veering between them as social restrictions expand and contract. Intelligent balancing of online and offline ways of relating also pertains to future policies on home and flexible working. A decision to switch to wholesale or obligatory homeworking should consider the risk to relational ‘group properties’ of the workplace community and their impact on employees’ well-being, focusing in particular on unequal impacts (eg, new vs established employees). Intelligent blending of online and in-person working is required to achieve flexibility while also nurturing supportive networks at work. Intelligent balance also implies strategies to build digital literacy and minimise digital exclusion, as well as coproducing solutions with intended beneficiaries.

Recommendation 3: build stronger and sustainable localised communities

In balancing offline and online ways of interacting, there is opportunity to capitalise on the potential for more localised, coherent communities due to scaled-down travel, homeworking and local focus that will ideally continue after restrictions end. There are potential economic benefits after the pandemic, such as increased trade as home workers use local resources (eg, coffee shops), but also relational benefits from stronger relationships around the orbit of the home and neighbourhood. Experience from previous crises shows that community volunteer efforts generated early on will wane over time in the absence of deliberate work to maintain them. Adequately funded partnerships between local government, third sector and community groups are required to sustain community assets that began as a direct response to the pandemic. Such partnerships could work to secure green spaces and indoor (non-commercial) meeting spaces that promote community interaction. Green spaces in particular provide a triple benefit in encouraging physical activity and mental health, as well as facilitating social bonding. 50 In building local communities, small community networks—that allow for diversity and break down ingroup/outgroup views—may be more helpful than the concept of ‘support bubbles’, which are exclusionary and less sustainable in the longer term. Rigorously designed intervention and evaluation—taking a systems approach—will be crucial in ensuring scale-up and sustainability.

The dramatic change to social interaction necessitated by efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 created stark challenges but also opportunities. Our essay highlights opportunities for learning, both to ensure the equity and humanity of physical restrictions, and to sustain the salutogenic effects of social relationships going forward. The starting point for capitalising on this learning is recognition of the disruption to relational mechanisms as a key part of the socioeconomic and health impact of the pandemic. In recovery planning, a general rule is that what is good for decreasing health inequalities (such as expanding social protection and public services and pursuing green inclusive growth strategies) 4 will also benefit relationships and safeguard relational mechanisms for future generations. Putting this into action will require political will.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS)

- Ford T , et al

- Riordan R ,

- Ford J , et al

- Glonti K , et al

- McPherson JM ,

- Smith-Lovin L

- Granovetter MS

- Fancourt D et al

- Stadtfeld C

- Office for Civil Society

- Cook J et al

- Rodriguez-Llanes JM ,

- Guha-Sapir D

- Patulny R et al

- Granovetter M

- Winkeler M ,

- Filipp S-H ,

- Kaniasty K ,

- de Terte I ,

- Guilaran J , et al

- Wright KB ,

- Martin J et al

- Gabbiadini A ,

- Baldissarri C ,

- Durante F , et al

- Sommerlad A ,

- Marston L ,

- Huntley J , et al

- Turner RJ ,

- Bicchieri C

- Brennan G et al

- Watson-Jones RE ,

- Amichai-Hamburger Y ,

- McKenna KYA

- Page-Gould E ,

- Aron A , et al

- Pietromonaco PR ,

- Timmerman GM

- Bradbury-Jones C ,

- Mikocka-Walus A ,

- Klas A , et al

- Marshall L ,

- Steptoe A ,

- Stanley SM ,

- Campbell AM

- ↵ (ONS), O.f.N.S., Domestic abuse during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, England and Wales . Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabuseduringthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicenglandandwales/november2020

- Rosenberg M ,

- Hensel D , et al

- Banerjee D ,

- Bruner DW , et al

- Bavel JJV ,

- Baicker K ,

- Boggio PS , et al

- van Barneveld K ,

- Quinlan M ,

- Kriesler P , et al

- Mitchell R ,

- de Vries S , et al

Twitter @karenmaxSPHSU, @Mark_McCann, @Rwilsonlowe, @KMitchinGlasgow

Contributors EL and KM led on the manuscript conceptualisation, review and editing. SP, KM, CB, RBP, RL, MM, JR, KS and RW-L contributed to drafting and revising the article. All authors assisted in revising the final draft.

Funding The research reported in this publication was supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/1, MC_UU_00022/3) and the Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU11, SPHSU14). EL is also supported by MRC Skills Development Fellowship Award (MR/S015078/1). KS and MM are also supported by a Medical Research Council Strategic Award (MC_PC_13027).

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

The degree for investment bankers.

Andrew Bauld May 31, 2024

States' Responses to FAFSA Delays

Sarah Wood May 30, 2024

Nonacademic Factors in College Searches

Sarah Wood May 28, 2024

Takeaways From the NCAA’s Settlement

Laura Mannweiler May 24, 2024

New Best Engineering Rankings June 18

Robert Morse and Eric Brooks May 24, 2024

Premedical Programs: What to Know

Sarah Wood May 21, 2024

How Geography Affects College Admissions

Cole Claybourn May 21, 2024

Q&A: College Alumni Engagement

LaMont Jones, Jr. May 20, 2024

10 Destination West Coast College Towns

Cole Claybourn May 16, 2024

Scholarships for Lesser-Known Sports

Sarah Wood May 15, 2024

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The best — and worst — criticisms of trump’s conviction, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, what’s really happening to grocery prices right now, big milk has taken over american schools, we need to talk more about trump’s misogyny, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Why the uncanny “All eyes on Rafah” image went so viral

Leaked video reveals the lie of Miss Universe’s empowerment promise

The Sympathizer takes on Hollywood’s Vietnam War stories

The NCAA’s proposal to pay college athletes is fair. That's the problem.

Your favorite brand no longer cares about being woke

The WNBA’s meteoric rise in popularity, in one chart

Billie Eilish vs. Taylor Swift: Is the feud real? Who’s dissing who?

What Trump really thinks about the war in Gaza

What ever happened to the war on terror?

The MLB’s long-overdue decision to add Negro Leagues’ stats, briefly explained

How COVID Changed the World

Lessons from two years of emergency science, upheaval and loss

Olena Shmahalo

Pandemic-Era Research Will Pay Off for Years

The COVID research infrastructure will help fight all sorts of pathogens

Britt Glaunsinger

Introducing 21 Ways COVID Changed the World

The pandemic didn’t bring us together, but it did show us what we need to change the most

Jen Schwartz

COVID Pushed Global Health Institutions to Their Limits

The need to reinvent the World Health Organization has become abundantly clear

Lawrence O. Gostin

COVID Has Made Global Inequality Much Worse

The poor, no matter where they live, will suffer the greatest lasting toll

Joseph E. Stiglitz

COVID Changed the World of Work Forever

People realized their jobs don’t have to be that way

Christina Maslach, Michael P. Leiter

The Pandemic Set Off a Boom in Diagnostics

COVID accelerated the development of cutting-edge PCR tests—and made the need for them urgent

Roxanne Khamsi

A High-Speed Scientific Hive Mind Emerged from the COVID Pandemic

The pandemic pushed researchers into new forms of rapid communication and collaboration

Joseph Bak-Coleman, Carl T. Bergstrom

COVID’s Uneven Toll Captured in Data

Visualizing ongoing stories of loss, adaptation and inequality

Amanda Montañez, Jen Christiansen, Sabine Devins, Mariana Surillo, Ashley P. Taylor

COVID Revealed the Fragility of American Public Health

What happens when a deadly virus hits a vulnerable society

Wendy E. Parmet

The Pandemic Showed the Promise of Cities with Fewer Cars

Residents learned what was possible. Some politicians fought to keep it that way

Andrea Thompson

How a Virus Exposed the Myth of Rugged Individualism

Humans evolved to be interdependent, not self-sufficient

Robin G. Nelson

The Pandemic Deepened Fault Lines in American Society

COVID energized the Black Lives Matter movement—and provoked a dangerous backlash

Aldon Morris

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and respiratory illness

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- The positive effects...

The positive effects of covid-19

Read our latest coverage of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Bryn Nelson , science journalist

- Seattle, WA, USA

- bdnelson{at}nasw.org

As the coronavirus pandemic continues its deadly path, dramatic changes in how people live are reducing some instances of other medical problems. Bryn Nelson writes that the irony may hold valuable lessons for public health

Doctors and researchers are noticing some curious and unexpectedly positive side effects of the abrupt shifts in human behaviour in response to the covid-19 pandemic. Skies are bluer, fewer cars are crashing, crime is falling, and some other infectious diseases are fading from hospital emergency departments.

Other changes are unquestionably troubling. American doctors have expressed alarm over a nosedive in patients presenting to emergency departments with heart attacks, strokes, and other conditions, leading to fears that patients are too afraid of contracting covid-19 to seek necessary medical care. 1 Calls to poison control centres are up by around 20%, attributed to a rise in accidents with cleaners and disinfectants even before President Trump questioned whether injected disinfectants might stop the virus. 2 Calls to suicide prevention lines are skyrocketing, while health experts are fretting about signs of rising alcohol and drug use, poorer diets, and a lack of exercise among those cooped-up at home. 3 Millions of people are hungry and unemployed.

But doctors, researchers, and public health officials say the pandemic is also providing a unique window through which to view some positive health effects from major changes in human behaviour. And the pandemic may lead to a public more willing to accept and act on public health messages.

Alice Pong, a paediatric infectious disease physician and the medical director for infection control at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, California, said the hospital has seen a sharp decline in paediatric admissions for respiratory illnesses. These include diseases such as influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and human metapneumovirus.

“We track positive viral tests through our hospital lab and those numbers have gone down dramatically since everybody went into quarantine,” Pong told The BMJ . “We do think that’s a reflection of kids not being in day care or school.” The hospital is testing fewer patients, she said, which could be because more children might be staying home with respiratory symptoms. But more serious cases and intensive care unit admissions are down as well, suggesting a true decline in life threatening illnesses.

Beyond the disease reducing effects of social distancing, Pong said she believes children and families are taking advice on hand washing, personal hygiene, and other prevention measures seriously. “I think this is going to be a good lesson for everybody,” she said. ‘‘The public is seeing why public health officials have advised them stay home when they feel sick, for example, and why they’ve emphasised hand washing and covering a cough or sneeze. Kids growing up now will know this is how germs are spread,” Pong said. That message could spread to their families and broaden awareness.

Fewer cars, blue skies

With covid-19 shutting down economic activity in most parts of the world and people staying closer to home, street crimes like assault and robbery are down significantly, though domestic violence has increased. 4 Traffic has plummeted as well. As a result, NASA satellites have documented significant reductions in air pollution—20-30% in many cases—in major cities around the world. 5 Based on those declines, Marshall Burke, an environmental economist at Stanford University, predicted in a blog post that two months’ worth of improved air quality in China alone might save the lives of 4000 children under the age of 5 and 73 000 adults over the age of 70 (a more conservative calculation estimated about 50 000 saved lives). 6

Although baseline pollution levels in the US are lower, Burke said a similar 20-30% reduction in pollution would still likely yield significant health benefits. “A pandemic is a terrible way to improve environmental health,” he emphasised. It may, however, provide an unexpected vantage to help understand how environmental health can be altered. “It may help bring into focus the effect of business as usual on health outcomes that we care about,” he told The BMJ . “In some sense, it helps us imagine the future.” Getting there, he says, could instead come through better regulation and technology.

A separate report coauthored by Fraser Shilling, director of the Road Ecology Center at the University of California at Davis, found that highway accidents—including those involving an injury or fatality—fell by half after the state’s shelter-in-place order on 19 March. 7 “The reduction in traffic accidents is unparalleled,” and yielded an estimated $40m (£32m; €37m) in public savings every day, the report asserted.

Whereas average traffic speeds increased by only a few miles per hour, traffic volume fell by 55%. Hospitals in the Sacramento region reported fewer trauma related admissions while other reports indicated fewer car collisions with pedestrians and cyclists.

In Washington, collisions on state highways fell even further—by 62%—in the month after the state’s stay-at-home order went into effect on 23 March, compared with the previous year, according to the Washington State Patrol. The question, Shilling said, is whether researchers can learn from the information to design safer transportation patterns. “We’re not going to be guessing anymore about what happens when you take half the cars away,” he said.