- Clerc Center | PK-12 & Outreach

- KDES | PK-8th Grade School (D.C. Metro Area)

- MSSD | 9th-12th Grade School (Nationwide)

- Gallaudet University Regional Centers

- Parent Advocacy App

- K-12 ASL Content Standards

- National Resources

- Youth Programs

- Academic Bowl

- Battle Of The Books

- National Literary Competition

- Youth Debate Bowl

- Youth Esports Series

- Bison Sports Camp

- Discover College and Careers (DC²)

- Financial Wizards

- Immerse Into ASL

- Alumni Relations

- Alumni Association

- Homecoming Weekend

- Class Giving

- Get Tickets / BisonPass

- Sport Calendars

- Cross Country

- Swimming & Diving

- Track & Field

- Indoor Track & Field

- Cheerleading

- Winter Cheerleading

- Human Resources

- Plan a Visit

- Request Info

- Areas of Study

- Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- American Sign Language

- Art and Media Design

- Communication Studies

- Criminal Justice

- Data Science

- Deaf Studies

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Programs

- Educational Neuroscience

- Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Information Technology

- International Development

- Interpretation and Translation

- Linguistics

- Mathematics

- Philosophy and Religion

- Physical Education & Recreation

- Public Affairs

- Public Health

- Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Theatre and Dance

- World Languages and Cultures

- B.A. in American Sign Language

- B.A. in Biology

- B.A. in Communication Studies

- B.A. in Communication Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Deaf Studies

- B.A. in Deaf Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Early Childhood Education

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Elementary Education

- B.A. in English

- B.A. in English for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Government

- B.A. in Government with a Specialization in Law

- B.A. in History

- B.A. in Interdisciplinary Spanish

- B.A. in International Studies

- B.A. in Mathematics

- B.A. in Philosophy

- B.A. in Psychology

- B.A. in Psychology for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Social Work (BSW)

- B.A. in Sociology with a concentration in Criminology

- B.A. in Theatre Arts: Production/Performance

- B.A. or B.S. in Education with a Specialization in Secondary Education: Science, English, Mathematics or Social Studies

- B.S. in Accounting

- B.S. in Accounting for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Biology

- B.S. in Business Administration

- B.S. in Business Administration for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Data Science

- B.S. in Information Technology

- B.S. in Mathematics

- B.S. in Physical Education and Recreation

- B.S. in Public Health

- B.S. in Risk Management and Insurance

- General Education

- Honors Program

- Peace Corps Prep program

- Self-Directed Major

- M.A. in Counseling: Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- M.A. in Counseling: School Counseling

- M.A. in Deaf Education

- M.A. in Deaf Education Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Cultural Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Language and Human Rights

- M.A. in Early Childhood Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Early Intervention Studies

- M.A. in Elementary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Interpretation: Combined Interpreting Practice and Research

- M.A. in Interpretation: Interpreting Research

- M.A. in Linguistics

- M.A. in Secondary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Sign Language Education

- M.S. in Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

- Master of Public Administration

- Master of Social Work (MSW)

- Au.D. in Audiology

- Ed.D. in Transformational Leadership and Administration in Deaf Education

- Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology

- Ph.D. in Critical Studies in the Education of Deaf Learners

- Ph.D. in Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Ph.D. in Linguistics

- Ph.D. in Translation and Interpreting Studies

- Ph.D. Program in Educational Neuroscience (PEN)

- Psy.D. in School Psychology

- Individual Courses and Training

- National Caregiver Certification Course

- CASLI Test Prep Courses

- Course Sections

- Certificates

- Certificate in Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Educating Deaf Students with Disabilities (online, post-bachelor’s)

- American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education

- Early Intervention Studies

- Online Degree Programs

- ODCP Minor in Communication Studies

- ODCP Minor in Deaf Studies

- ODCP Minor in Psychology

- ODCP Minor in Writing

- University Capstone Honors for Online Degree Completion Program

Quick Links

- PK-12 & Outreach

- NSO Schedule

Guide to Writing Introductions and Conclusions

202.448-7036

First and last impressions are important in any part of life, especially in writing. This is why the introduction and conclusion of any paper – whether it be a simple essay or a long research paper – are essential. Introductions and conclusions are just as important as the body of your paper. The introduction is what makes the reader want to continue reading your paper. The conclusion is what makes your paper stick in the reader’s mind.

Introductions

Your introductory paragraph should include:

1) Hook: Description, illustration, narration or dialogue that pulls the reader into your paper topic. This should be interesting and specific.

2) Transition: Sentence that connects the hook with the thesis.

3) Thesis: Sentence (or two) that summarizes the overall main point of the paper. The thesis should answer the prompt question.

The examples below show are several ways to write a good introduction or opening to your paper. One example shows you how to paraphrase in your introduction. This will help you understand the idea of writing sequences using a hook, transition, and thesis statement.

» Thesis Statement Opening

This is the traditional style of opening a paper. This is a “mini-summary” of your paper.

For example:

» Opening with a Story (Anecdote)

A good way of catching your reader’s attention is by sharing a story that sets up your paper. Sharing a story gives a paper a more personal feel and helps make your reader comfortable.

This example was borrowed from Jack Gannon’s The Week the World Heard Gallaudet (1989):

Astrid Goodstein, a Gallaudet faculty member, entered the beauty salon for her regular appointment, proudly wearing her DPN button. (“I was married to that button that week!” she later confided.) When Sandy, her regular hairdresser, saw the button, he spoke and gestured, “Never! Never! Never!” Offended, Astrid turned around and headed for the door but stopped short of leaving. She decided to keep her appointment, confessing later that at that moment, her sense of principles had lost out to her vanity. Later she realized that her hairdresser had thought she was pushing for a deaf U.S. President. Hook: a specific example or story that interests the reader and introduces the topic.

Transition: connects the hook to the thesis statement

Thesis: summarizes the overall claim of the paper

» Specific Detail Opening

Giving specific details about your subject appeals to your reader’s curiosity and helps establish a visual picture of what your paper is about.

» Open with a Quotation

Another method of writing an introduction is to open with a quotation. This method makes your introduction more interactive and more appealing to your reader.

» Open with an Interesting Statistic

Statistics that grab the reader help to make an effective introduction.

» Question Openings

Possibly the easiest opening is one that presents one or more questions to be answered in the paper. This is effective because questions are usually what the reader has in mind when he or she sees your topic.

Source : *Writing an Introduction for a More Formal Essay. (2012). Retrieved April 25, 2012, from http://flightline.highline.edu/wswyt/Writing91/handouts/hook_trans_thesis.htm

Conclusions

The conclusion to any paper is the final impression that can be made. It is the last opportunity to get your point across to the reader and leave the reader feeling as if they learned something. Leaving a paper “dangling” without a proper conclusion can seriously devalue what was said in the body itself. Here are a few effective ways to conclude or close your paper. » Summary Closing Many times conclusions are simple re-statements of the thesis. Many times these conclusions are much like their introductions (see Thesis Statement Opening).

» Close with a Logical Conclusion

This is a good closing for argumentative or opinion papers that present two or more sides of an issue. The conclusion drawn as a result of the research is presented here in the final paragraphs.

» Real or Rhetorical Question Closings

This method of concluding a paper is one step short of giving a logical conclusion. Rather than handing the conclusion over, you can leave the reader with a question that causes him or her to draw his own conclusions.

» Close with a Speculation or Opinion This is a good style for instances when the writer was unable to come up with an answer or a clear decision about whatever it was he or she was researching. For example:

» Close with a Recommendation

A good conclusion is when the writer suggests that the reader do something in the way of support for a cause or a plea for them to take action.

202-448-7036

At a Glance

- Quick Facts

- University Leadership

- History & Traditions

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Our 10-Year Vision: The Gallaudet Promise

- Annual Report of Achievements (ARA)

- The Signing Ecosystem

- Not Your Average University

Our Community

- Library & Archives

- Technology Support

- Interpreting Requests

- Ombuds Support

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Profile & Web Edits

Visit Gallaudet

- Explore Our Campus

- Virtual Tour

- Maps & Directions

- Shuttle Bus Schedule

- Kellogg Conference Hotel

- Welcome Center

- National Deaf Life Museum

- Apple Guide Maps

Engage Today

- Work at Gallaudet / Clerc Center

- Social Media Channels

- University Wide Events

- Sponsorship Requests

- Data Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Gallaudet Today Magazine

- Giving at Gallaudet

- Financial Aid

- Registrar’s Office

- Residence Life & Housing

- Safety & Security

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- University Communications

- Clerc Center

Gallaudet University, chartered in 1864, is a private university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Copyright © 2024 Gallaudet University. All rights reserved.

- Accessibility

- Cookie Consent Notice

- Privacy Policy

- File a Report

800 Florida Avenue NE, Washington, D.C. 20002

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an essay introduction paragraph with paperpal – step -by -step, how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an essay introduction:

- Start with a Hook : Begin your introduction paragraph with an attention-grabbing statement, question, quote, or anecdote related to your topic. The hook should pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to continue reading.

- Provide Background Information : This helps the reader understand the relevance and importance of the topic.

- State Your Thesis Statement : The last sentence is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and directly address the topic of your essay.

- Preview the Main Points : This gives the reader an idea of what to expect and how you will support your thesis.

- Keep it Concise and Clear : Avoid going into too much detail or including information not directly relevant to your topic.

- Revise : Revise your introduction after you’ve written the rest of your essay to ensure it aligns with your final argument.

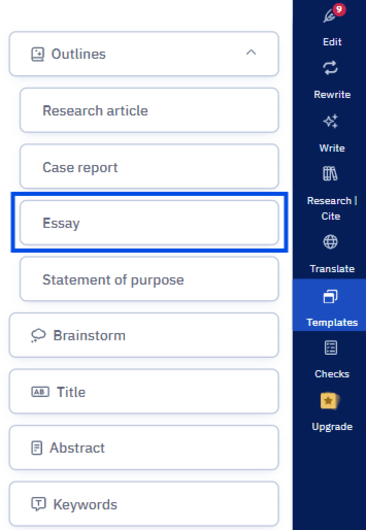

Unsure of how to start your essay introduction? Leverage Paperpal’s Generative AI templates to provide a base for your essay introduction. Here’s an example of an essay outline generated by Paperpal.

Use Paperpal’s Preditive AI writing features to maintain your writing flow

This is one of the key steps in how to write an essay introduction. Crafting a compelling hook is vital because it sets the tone for your entire essay and determines whether your readers will stay interested. A good hook draws the reader in and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

- Avoid Dry Fact : Instead of simply stating a bland fact, try to make it engaging and relevant to your topic. For example, if you’re writing about the benefits of exercise, you could start with a startling statistic like, “Did you know that regular exercise can increase your lifespan by up to seven years?”

- Avoid Using a Dictionary Definition : While definitions can be informative, they’re not always the most captivating way to start an essay. Instead, try to use a quote, anecdote, or provocative question to pique the reader’s interest. For instance, if you’re writing about freedom, you could begin with a quote from a famous freedom fighter or philosopher.

- Do Not Just State a Fact That the Reader Already Knows : This ties back to the first point—your hook should surprise or intrigue the reader. For Here’s an introduction paragraph example, if you’re writing about climate change, you could start with a thought-provoking statement like, “Despite overwhelming evidence, many people still refuse to believe in the reality of climate change.”

Write essays 2x faster with Paperpal. Try for free

Including background information in the introduction section of your essay is important to provide context and establish the relevance of your topic. When writing the background information, you can follow these steps:

- Start with a General Statement: Begin with a general statement about the topic and gradually narrow it down to your specific focus. For example, when discussing the impact of social media, you can begin by making a broad statement about social media and its widespread use in today’s society, as follows: “Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of users worldwide.”

- Define Key Terms : Define any key terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to your readers but are essential for understanding your argument.

- Provide Relevant Statistics: Use statistics or facts to highlight the significance of the issue you’re discussing. For instance, “According to a report by Statista, the number of social media users is expected to reach 4.41 billion by 2025.”

- Discuss the Evolution: Mention previous research or studies that have been conducted on the topic, especially those that are relevant to your argument. Mention key milestones or developments that have shaped its current impact. You can also outline some of the major effects of social media. For example, you can briefly describe how social media has evolved, including positives such as increased connectivity and issues like cyberbullying and privacy concerns.

- Transition to Your Thesis: Use the background information to lead into your thesis statement, which should clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay. For example, “Given its pervasive influence, it is crucial to examine the impact of social media on mental health.”

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other type of academic writing. It appears near the end of the introduction. Here’s how to write a thesis statement:

- Identify the topic: Start by identifying the topic of your essay. For example, if your essay is about the importance of exercise for overall health, your topic is “exercise.”

- State your position: Next, state your position or claim about the topic. This is the main argument or point you want to make. For example, if you believe that regular exercise is crucial for maintaining good health, your position could be: “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining good health.”

- Support your position: Provide a brief overview of the reasons or evidence that support your position. These will be the main points of your essay. For example, if you’re writing an essay about the importance of exercise, you could mention the physical health benefits, mental health benefits, and the role of exercise in disease prevention.

- Make it specific: Ensure your thesis statement clearly states what you will discuss in your essay. For example, instead of saying, “Exercise is good for you,” you could say, “Regular exercise, including cardiovascular and strength training, can improve overall health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

Examples of essay introduction

Here are examples of essay introductions for different types of essays:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

Topic: Should the voting age be lowered to 16?

“The question of whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 has sparked nationwide debate. While some argue that 16-year-olds lack the requisite maturity and knowledge to make informed decisions, others argue that doing so would imbue young people with agency and give them a voice in shaping their future.”

Expository Essay Introduction Example

Topic: The benefits of regular exercise

“In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. From improving physical health to boosting mental well-being, the benefits of exercise are numerous and far-reaching. This essay will examine the various advantages of regular exercise and provide tips on incorporating it into your daily routine.”

Text: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“Harper Lee’s novel, ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ is a timeless classic that explores themes of racism, injustice, and morality in the American South. Through the eyes of young Scout Finch, the reader is taken on a journey that challenges societal norms and forces characters to confront their prejudices. This essay will analyze the novel’s use of symbolism, character development, and narrative structure to uncover its deeper meaning and relevance to contemporary society.”

- Engaging and Relevant First Sentence : The opening sentence captures the reader’s attention and relates directly to the topic.

- Background Information : Enough background information is introduced to provide context for the thesis statement.

- Definition of Important Terms : Key terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to the audience or are central to the argument are defined.

- Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement presents the main point or argument of the essay.

- Relevance to Main Body : Everything in the introduction directly relates to and sets up the discussion in the main body of the essay.

Write strong essays in academic English with Paperpal. Try it for free

Writing a strong introduction is crucial for setting the tone and context of your essay. Here are the key takeaways for how to write essay introduction: 3

- Hook the Reader : Start with an engaging hook to grab the reader’s attention. This could be a compelling question, a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or an anecdote.

- Provide Background : Give a brief overview of the topic, setting the context and stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement : State your thesis, which is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

- Preview the Structure : Outline the main points or arguments to help the reader understand the organization of your essay.

- Keep it Concise : Avoid including unnecessary details or information not directly related to your thesis.

- Revise and Edit : Revise your introduction to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance. Check for grammar and spelling errors.

- Seek Feedback : Get feedback from peers or instructors to improve your introduction further.

The purpose of an essay introduction is to give an overview of the topic, context, and main ideas of the essay. It is meant to engage the reader, establish the tone for the rest of the essay, and introduce the thesis statement or central argument.

An essay introduction typically ranges from 5-10% of the total word count. For example, in a 1,000-word essay, the introduction would be roughly 50-100 words. However, the length can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the overall length of the essay.

An essay introduction is critical in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. To ensure its effectiveness, consider incorporating these key elements: a compelling hook, background information, a clear thesis statement, an outline of the essay’s scope, a smooth transition to the body, and optional signposting sentences.

The process of writing an essay introduction is not necessarily straightforward, but there are several strategies that can be employed to achieve this end. When experiencing difficulty initiating the process, consider the following techniques: begin with an anecdote, a quotation, an image, a question, or a startling fact to pique the reader’s interest. It may also be helpful to consider the five W’s of journalism: who, what, when, where, why, and how. For instance, an anecdotal opening could be structured as follows: “As I ascended the stage, momentarily blinded by the intense lights, I could sense the weight of a hundred eyes upon me, anticipating my next move. The topic of discussion was climate change, a subject I was passionate about, and it was my first public speaking event. Little did I know , that pivotal moment would not only alter my perspective but also chart my life’s course.”

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your introduction paragraph is crucial to grab your reader’s attention. To achieve this, avoid using overused phrases such as “In this paper, I will write about” or “I will focus on” as they lack originality. Instead, strive to engage your reader by substantiating your stance or proposition with a “so what” clause. While writing your thesis statement, aim to be precise, succinct, and clear in conveying your main argument.

To create an effective essay introduction, ensure it is clear, engaging, relevant, and contains a concise thesis statement. It should transition smoothly into the essay and be long enough to cover necessary points but not become overwhelming. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to assess its effectiveness.

References

- Cui, L. (2022). Unit 6 Essay Introduction. Building Academic Writing Skills .

- West, H., Malcolm, G., Keywood, S., & Hill, J. (2019). Writing a successful essay. Journal of Geography in Higher Education , 43 (4), 609-617.

- Beavers, M. E., Thoune, D. L., & McBeth, M. (2023). Bibliographic Essay: Reading, Researching, Teaching, and Writing with Hooks: A Queer Literacy Sponsorship. College English, 85(3), 230-242.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- How to Write a Good Hook for Essays, with Examples

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

Similarity Checks: The Author’s Guide to Plagiarism and Responsible Writing

Types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid it in your writing , you may also like, what are the types of literature reviews , abstract vs introduction: what is the difference , mla format: guidelines, template and examples , machine translation vs human translation: which is reliable..., dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal.

21 Writing an Introduction and Conclusion

The introduction and conclusion are the strong walls that hold up the ends of your essay. The introduction should pique the readers’ interest, articulate the aim or purpose of the essay, and provide an outline of how the essay is organised. The conclusion mirrors the introduction in structure and summarizes the main aim and key ideas within the essay, drawing to a logical conclusion. The introduction states what the essay will do and the conclusion tells the reader what the essay has achieved .

Introduction

The primary functions of the introduction are to introduce the topic and aim of the essay, plus provide the reader with a clear framework of how the essay will be structured. Therefore, the following sections provide a brief overview of how these goals can be achieved. The introduction has three basic sections (often in one paragraph if the essay is short) that establish the key elements: background, thesis statement, and essay outline.

The background should arrest the readers’ attention and create an interest in the chosen topic. Therefore, backgrounding on the topic should be factual, interesting, and may use supporting evidence from academic sources . Shorter essays (under 1000 words) may only require 1-3 sentences for backgrounding, so make the information specific and relevant, clear and succinct . Longer essays may call for a separate backgrounding paragraph. Always check with your lecturer/tutor for guidelines on your specific assignment.

Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is a theory, put forward as a position to be maintained or proven by the writing that follows in the essay. It focuses the writer’s ideas within the essay and all insights, arguments and viewpoints centre around this statement. The writer should refer back to it both mentally and literally throughout the writing process, plus the reader should see the key concepts within the thesis unfolding throughout the written work. A separate section about developing the thesis statement has been included below.

Essay Outline Sentence/s

The essay outline is 1-2 sentences that articulate the focus of the essay in stages. They clearly explain how the thesis statement will be addressed in a sequential manner throughout the essay paragraphs. The essay outline should also leave no doubt in the readers’ minds about what is NOT going to be addressed in your essay. You are establishing the parameters, boundaries, or limitations of the essay that follows. Do not, however, use diminishing language such as, “this brief essay will only discuss…”, “this essay hopes to prove/will attempt to show…”. This weakens your position from the outset. Use strong signposting language, such as “This essay will discuss… (paragraph 1) then… (paragraph 2) before moving on to… (paragraph 3) followed by the conclusion and recommendations”. This way the reader knows from the outset how the essay will be structured and it also helps you to better plan your body paragraphs (see Chapter 22).

Brief Example

(Background statement) Nuclear power plants are widely used throughout the world as a clean, efficient source of energy. (Thesis with a single idea) It has been proven that thermonuclear energy (topic) is a clean, safe alternative to burning fossil fuels. (Essay outline sentence) This essay will discuss the environmental, economic, social impacts of having a thermonuclear power plant providing clean energy to a major city.

- Background statement

- Thesis statement – claim

- Essay outline sentence (with three controlling ideas )

Regardless of the length of the essay, it should always have a thesis statement that clearly articulates the key aim or argument/s in the essay. It focuses both the readers’ attention and the essay’s purpose. In a purely informative or descriptive essay, the thesis may contain a single, clear claim. Whereas, in a more complex analytical, persuasive, or critical essay (see Chapter 15) there may be more than one claim, or a claim and counter-claim (rebuttal) within the thesis statement (see Chapter 25 – Academic Writing [glossary]). It is important to remember that the majority of academic writing is not only delivering information, it is arguing a position and supporting claims with facts and reliable examples. A strong thesis will be original, specific and arguable. This means it should never be a statement of the obvious or a vague reference to general understandings on a topic.

Weak Thesis Examples

The following examples are too vague and leave too many questions unanswered because they are not specific enough.

“Reading is beneficial” – What type of reading? Reading at what level/age? Reading for what time period? Reading what types of text? How is it beneficial, to who?

“Dogs are better than cats” – Better in what way? What types of dogs in what environment? Domesticated or wild animals? What are the benefits of being a dog owner? Is this about owning a dog or just dogs as a breed?

“Carbon emissions are ruining our planet” – Carbon emissions from where/what? In what specific way is our planet suffering? What is the timeframe of this problem?

A strong thesis should stand up to scrutiny. It should be able to answer the “So what?” question. Why should the reader want to continue reading your essay? What are you going to describe, argue, contest that will fix their attention? If no-one can or would argue with your thesis, then it is too weak, too obvious.

Your thesis statement is your answer to the essay question.

A strong thesis treats the topic of an essay in-depth. It will make an original claim that is both interesting and supportable, plus able to be refuted. In a critical essay this will allow you to argue more than one point of view (see Chapter 27 – Writing a Discursive Essay ). Again, this is why it is important that you complete sufficient background reading and research on your topic to write from an informed position.

Strong Thesis Examples

“Parents reading to their children, from age 1-5 years, enhance their children’s vocabulary, their interest in books, and their curiosity about the world around them.”

“Small, domesticated dogs make better companions than domesticated cats because of their loyal and intuitive nature.”

“Carbon emissions from food production and processing are ruining Earth’s atmosphere.”

As demonstrated, by adding a specific focus, and key claim, the above thesis statements are made stronger.

Beginner and intermediate writers may prefer to use a less complex and sequential thesis like those above. They are clear, supportable and arguable. This is all that is required for the Term one and two writing tasks.

Once you become a more proficient writer and advance into essays that are more analytical and critical in nature, you will begin to incorporate more than one perspective in the thesis statement. Again, each additional perspective should be arguable and able to be supported with clear evidence. A thesis for a discursive essay (Term Three) should contain both a claim AND counter-claim , demonstrating your capacity as a writer to develop more than one perspective on a topic.

A Note on Claims and Counter-claims

Demonstrating that there is more than one side to an argument does not weaken your overall position on a topic. It indicates that you have used your analytical thinking skills to identify more than one perspective, potentially including opposing arguments. In your essay you may progress in such a way that refutes or supports the claim and counter-claim.

Please do not confuse the words ‘claim’ and ‘counter-claim’ with moral or value judgements about right/wrong, good/bad, successful/unsuccessful, or the like. The term ‘claim’ simply refers to the first position or argument you put forward, and ‘counter-claim’ is the alternate position or argument.

Discursive Essay Thesis – Examples adapted from previous students

“ Although it is argued that renewable energy may not meet the energy needs of Australia, there is research to indicate the benefits of transitioning to more environmentally favourable energy sources now.”

“It is argued that multiculturalism is beneficial for Australian society, economy and culture, however some members of society have a negative view of multiculturalism‘s effects on the country.”

“The widespread adoption of new technologies is inevitable and may benefit society, however , these new technologies could raise ethical issues and therefore might be of detriment .”

Note the use of conjunctive terms (underlined) to indicate alternative perspectives.

In term three you will be given further instruction in developing a thesis statement for a discursive essay in class time.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of the essay and it summarizes and synthesizes the topic and key ideas, including the thesis statement. As such, no new information or citations should be present in the conclusion. It should be written with an authoritative , formal tone as you have taken the time to support all the claims (and counter-claims) in your essay. It should follow the same logical progression as the key points in your essay and reach a clear and well-written conclusion – the statement within the concluding paragraph that makes it very clear you have answered the essay question. Read the marking criteria of your assignment to determine whether you are also required to include a recommendation or prediction as part of the conclusion. If so, make recommendations relevant to the context and content of the essay. They should be creative, specific and realistic. If you are making a prediction, focus on how the information or key arguments used in the essay might impact the world around you, or the field of inquiry, in a realistic way.

A strong, well-written conclusion should draw all of the threads of the essay together and show how they relate to each other and also how they make sense in relation to the essay question and thesis.

make clear, distinct, and precise in relation to other parts

Synonyms: catch and hold; attract and fix; engage

researched, reliable, written by academics and published by reputable publishers; often, but not always peer reviewed

concise expressed in few words

assertion, maintain as fact

a claim made to rebut a previous claim

attract and hold

used to link words or phrases together See 'Language Basics'

able to be trusted as being accurate or true; reliable

decision reached by sound and valid reasoning

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Current Students

- News & Press

- Exam Technique for In-Person Exams

- Revising for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Before the 24 Hour Take Home Exam

- Exam Technique for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Structuring a Literature Review

- Writing Coursework under Time Constraints

- Reflective Writing

- Writing a Synopsis

- Structuring a Science Report

- Presentations

- How the University works out your degree award

- Accessing your assignment feedback via Canvas

- Inspera Digital Exams

- Writing Introductions and Conclusions

- Paragraphing

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting

- Proofreading

- Working with a Proofreader

- Writing Concisely

- The 1-Hour Writing Challenge

- Editing strategies

- Apostrophes

- Semi-colons

- Run-on sentences

- How to Improve your Grammar (native English)

- How to Improve your Grammar (non-native English)

- Independent Learning for Online Study

- Reflective Practice

- Academic Reading

- Strategic Reading Framework

- Note-taking Strategies

- Note-taking in Lectures

- Making Notes from Reading

- Using Evidence to Support your Argument

- Integrating Scholarship

- Managing Time and Motivation

- Dealing with Procrastination

- How to Paraphrase

- Quote or Paraphrase?

- How to Quote

- Referencing

- Responsible and Ethical use of AI

- Acknowledging use of AI

- Numeracy, Maths & Statistics

- Library Search

- Search Techniques

- Keeping up to date

- Evaluating Information

- Managing Information

- Understanding Artificial Intelligence

- Getting started with prompts

- Thinking Critically about AI

- Using Information generated by AI

- SensusAccess

- Develop Your Digital Skills

- Digital Tools to Help You Study

Read a text summary on how to write introductions and conclusions.

- Newcastle University

- Academic Skills Kit

- Academic Writing

Introductions and conclusions can be tricky to write. They do not contain the main substance of your assignment, but they do play a key role in helping the reader navigate your writing. The usual advice is

- Introduction: say what you're going to say

- Main body: say it

- Conclusion: say that you've said it

However, this approach can feel repetitive and is not very rewarding to write or read.

A more engaging approach is to think about the perspective of the reader and what they need to know in order to make sense of your writing. In academic writing, it is the writer’s job to make their meaning clear (unlike in literature and fiction, where it is the reader’s job to interpret the meaning) so that the reader can concentrate on deciding what they think of your work and marking it. Introductions and conclusions play an important role in explaining your aims and approach, so to help you write them well, you could think about what questions the reader has for you as they pick up your work for the first time, and when they have finished reading it.

Introductions

The introductions are the first part of your assignment that the reader encounters, so it needs to make a good impression and set the scene for what follows. Your introduction is about 10% of the total word count. It can be difficult to think what that first opening sentence should be, or what an introduction should include.

From your reader’s perspective, they have three questions when they first pick up your assignment.

You could approach this question in a number of ways:

- Although your lecturer knows the assignment questions they’ve set, they don’t know how you have understood and interpreted it. To demonstrate that you’ve read it accurately, you can echo back the question to your reader, paraphrased in your own words so they know you have really understood it rather than just copying and pasting it.

- There might also be different ways to interpret the assignment, and clarifying for the reader how you’ve interpreted it would be helpful. Perhaps different angles on it are possible, there is more than one definition you could be working to, or you have been given a range of options within the assessment brief, and you need to tell the reader which approach you are taking.

- It’s also common to give a brief overview of a topic in the introduction, providing the reader with some context so they can understand what is to follow. Of course, your lecturer is already likely to know this basic information, so you could think of it as giving the reader confidence that you also share that foundational knowledge and have got your facts right. This aspect needs to be as brief as possible, as it can be very descriptive (which will not get you higher marks) and if it extends too far, can take up too much space in your essay which would be better used for analysis, interpretation or argumentation. A rough guide is to ask yourself which information is built on later in your assignment and cut anything that doesn’t get ‘used’ later on.

The obvious answer to this question is "because you told me to write this assignment”! A more interesting response, though, is to show that you've really understood why your lecturer has set that question and why it’s worth asking. None of the questions you are set at University will be simple or straightforward, but will be complex and problematic, and many have no single clear answer or approach. In responding thoughtfully to the question “why are you doing this”, you are reflecting on why it is significant, complex and worth doing, that you've understood the complexity of the assignment you’ve been set and recognise the lecturer’s aims in setting it.

Every student who answers a particular assignment will produce a different answer, with a different structure, making different points and drawing on different information. Your reader wants to know what your own particular approach to the assignment will be.

- You might answer this question in terms of what your structure is going to be, signalling how many sections you use and what order they appear in, signposting how you have broken the assignment down and organised it, so the reader knows what to expect.

- You might also explain to the reader which choices and decisions you have made to narrow it down to a manageable, focussed assignment. You might have chosen to set yourself particular limits on the scope of your assignment (for example, a focussing on a particular context, timespan, or type), or which examples and case studies you’ve chosen to illustrate your answer with, and why they are appropriate for this assignment.

- If relevant, you might also tell the reader about your methodology, the theories, models, definitions or approaches you have applied in order to answer the assignment question.

Your introduction may not include all these elements, or include them in the same balance or in this order, but if you address the reader’s three questions, your introduction will fulfil its purpose. Make sure you’re not jumping into your argument too early. Your introduction should introduce your argument but not actually do the work of making it yet; that is the job of the main body of the assignment.

Conclusions

Conclusions can feel a bit repetitive, as you need to revisit the points you’ve already made, but not include any new material. Again, the conclusion is usually about 10% of your total word count. The challenge is to make them engaging to read for your marker, but also interesting for you to write, so they feel purposeful. You cannot include any new material as conclusions should close a discussion down, not open up new avenues or leave points unresolved. If a point is important, it should be dealt with in the main body rather than as an afterthought.

As they read, your marker is focussing on each paragraph in detail, identifying the point you’re making, analysing and evaluating the evidence you’re using, and the way you explain, interpret and argue, to see if it makes sense. They’re also thinking about the quality of your work and what mark they’re going to give it, looking to see that you’ve met the marking criteria. University assignments are long enough that the reader will find it hard to give each point this kind of detailed scrutiny and keep the whole assignment in their mind at the same time. The job of the conclusion is to help them move from that close-up reading and zoom out to give them a sense of the whole.

Again, a good approach is to think of the questions that your reader has when they reach the end of your assignment.

Your conclusion is the overall answer to the original assignment question you were set. See if you can summarise your overall answer in one sentence. This might be the first line of your conclusion. Make sure that your concluding answer does match the question you were set in the assessment.

Having told the reader where they've got to, you will need to remind them of how you got there. To strengthen their confidence in your overall answer, you can remind them of the points you made and how together they build your conclusion.

Although you cannot include new information in your conclusion, you can show your thinking in a new light. One question your reader may have is “where does that leave me’? or “so what?”. You could therefore briefly discuss the significance of your conclusion. Now that you’ve demonstrated your answer to the question, how does that add to our overall understanding of this topic? What do we know, what can we do now, that we couldn’t before? If we hadn’t explored this topic, where would we be? Why is this conclusion important? This might resolve the issues you raised in the introduction when you answered the question ‘why am I doing this?’

A possible follow-on to this question is to examine what work might come next, if you didn’t have time constraints or word limits. This is particularly relevant in second and third year and masters level assignments, especially dissertations. This is a good way to show awareness of how your own thinking fits in the wider context of scholarship and research and how it might be developed. It might be a way to touch on aspects you had to cut out, or areas you couldn’t cover.

When to write the introduction and conclusion

You don’t have to write your assignment in order. If you find that the introduction is hard to start, then you could write it at the end of the process, which will ensure that it matches the assignment you’ve actually written. However, it might be a useful approach to at least begin by thinking about the introduction questions above, as it will help you in the planning process. Likewise, you could start with writing the conclusion if you have done extensive thinking and planning, as formulating your end goal might help to keep you on track (although be open to your overall answer changing a little in the process). Again, thinking about the conclusion questions above at the start of the process is a useful planning tool to clarify your thinking, even if you don’t write it until the end.

Download this guide as a PDF

Writing introductions and conclusions.

Read a text summary on how to write introductions and conclusions. **PDF Download**

Search type

University Wide

Faculty / School Portals

- Online Guides and Tutorials

Introductions and Conclusions

This resource focuses on writing introductions and conclusions for essays. We also have guidance for intros and conclusions in science writing.

Introductions

Essay introductions.

Your introduction creates the reader’s first impression of your essay and previews the essay’s content. It serves three important functions :

- it engages the reader’s interest

- it provides context for your topic

- it articulates the argument you intend to develop, via a thesis statement.

By being clear, organized, engaging and robust, a good introduction will make it obvious to the reader that you will respect their attention and that they are in good hands for the duration of the paper.

Wondering what a good introduction looks like in practice? Pay attention to academic articles and books—and also novels, short stories, and media pieces—and notice what others do to engage your attention and invite you into a piece of writing.

Provide context

Your introduction should include the basic details necessary to the reader’s understanding of your topic. For example, it should identify:

- the author and title of a literary work you are analyzing

- the time frame and geographical location of a social movement or historical event you are examining

- particular scholars or theories you will reference

- perhaps the research question that prompted your work

- any other essential contextual information.

An introduction should also provide any other context that will help the reader to make sense of the discussion to follow, such as your theoretical framework, relevant historical details, the way you will use particular terms or concepts, or the current state of debate about your topic.

Note, however, that the introduction is not the place to go into a detailed discussion of your argumentative points or minutiae related to your topic. A concise, well-focused introduction will engage your reader far more than will a wordy, rambling one. Save your detailed discussion for the body of the essay . You may provide a contextual paragraph or paragraphs following the introduction, to flesh out important context in more detail, but be concise.

Engage your reader’s interest

Beginning your essay with a general statement and narrowing to a more specific focus as the introduction progresses (the “funnel model”) is a common strategy. With this approach, ensure that your opening statement makes a direct comment about your topic; avoid opening with a statement that is too general. Statements that begin with phrases such as “Throughout human history” likely have little to do with your particular argument, and will repel rather than engage your reader’s interest.

For example, say you are writing about the representation of racialized people in Suzan Lori-Parks’ Venus . Here is an example of an opening statement that is too broad :

- In the 21 st century, many playwrights wrote about race and racial themes .

Instead, try one of these opening lines:

- Suzan Lori-Parks’ Venus considers the enduring impact of colonialization on the representation and reception of Black women’s bodies.

- Suzan Lori-Parks’ Venus demonstrates the tension between exploitation and celebrity in its depiction of Sarah Baartman’s performances in early nineteenth-century England.

These statements provide more specific starting points for your discussion (and yet they are, appropriately, broader than a thesis statement). The key to an effective opening paragraph is to signal your essay’s precise focus early .

Other effective openings

Other effective opening strategies include:

- offering an interesting quotation that is directly relevant to your topic

- posing a question to which you will offer an answer (or provisional answer) as the introduction progresses

- presenting a shocking fact or statistic that grabs the reader’s attention and anchors the topic in a concrete way

- introducing a point of view that you disagree with, to establish your own contrasting perspective

- employing an analogy or illustration to familiarize your reader with your topic, particularly if your topic is abstract or potentially outside of the reader’s experience.

Articulate the argument you intend to develop

The most important feature of your introduction is the thesis statement , which usually (but not always) appears towards the end of the introductory paragraph. Ensure that your thesis statement clearly expresses the point of your paper (your claim), and that, having read your introduction, your reader has a good grasp of what you intend to discuss and why it matters . You might lead up to your thesis statement by identifying a problem or question and how current research doesn’t fully address it. Demonstrating why this problem or question matters lends context to your paper, sets up your argument, and helps engage your reader’s interest.

You could write your introduction first, to map out the essay to follow and firm up your thesis statement as you prepare to write the body paragraphs. However, if you do write your introduction first, count on revising it after you’ve finished drafting your essay. Ensure that whatever you included in your introduction appears in the body of the essay, and that whatever you included in the body of the essay is previewed in your introduction. It is often a good idea to write the introduction last, once you have a firm grasp of the essay’s contents.

The length of your finished introduction should be in proportion to the overall length of your essay (e.g., a brief essay necessitates a brief introduction). Finally, proofread carefully—a well-crafted, error-free introduction will make a favourable impression on your reader.

Conclusions

Essay conclusions.

Conclusions are meant to provide a satisfying and graceful close to an essay—but no-one we know of finds them easy to write. Writers often approach the end of the essay wondering what is left to say about their topic and, consequently, put the least amount of effort into the essay’s concluding paragraph(s). However, an essay’s conclusion is very important—it is, after all, the last thing a reader reads, and a poorly written conclusion can undermine the positive impression created by the rest of the essay. These are the jobs of the conclusion:

- briefly re-state your claim and its main points

- briefly explain why this research / your ideas matter

- perhaps suggest a practical application of your claim

- identify queries for future related research.

Keep your conclusion a bit shorter than your introduction, and don’t introduce new ideas at this point.

Helpful strategies

If your essays tend to end “not with a bang, but a whimper” (apologies to T.S. Eliot), the following strategies may be helpful.

- Provide a brief summary of the essay’s thesis and main points, but reformulate these ideas in a new way, focusing on the way your ideas fit together, new connections, and the growth of your understanding about your topic.

- Consider the larger implications of the argument you have presented—how does your argument fit into the bigger picture? Ask yourself, “So what?” and “What is the significance of what I’ve said?” Think of how your argument aligns with the larger themes of your course or the wider issue of which your analysis is a part. The things you write about do matter, so try to convey that significance to your reader.

- Propose a potential solution (or solutions) to a problem you have identified in your essay. You might also pose questions for further study. These strategies demonstrate that the issue you have examined is not finite, and that, rather than attempting to have the last word on the subject, you are opening the door to further inquiry.

- Include an apt quotation that reflects or expands on the essay’s thesis. If you used a quotation in your introduction, employing a parallel strategy to end your essay can provide a pleasing sense of symmetry.

- Similarly, if you began your essay with a question, return to that question in the conclusion and provide a direct answer . Using such a rhetorical strategy demonstrates your mastery of not just your essay’s content but of its structure, as well.

Try to avoid...

In writing your conclusion, avoid:

- mechanically repeating the original thesis and argumentative points.

- failing to demonstrate that, by the conclusion, you have reached a fuller understanding of the original idea.

- introducing completely new ideas, subtopics, evidence that should have been explored in the body of the paper, or minor (usually irrelevant) details.

- bringing up a contradiction. If you address the “other side” of the issue or debate in your essay, do so early on (often immediately after the introduction, before you present your own argument). Mentioning the “other side” in your conclusion will only confuse the reader and undermine what you have said in the body of the essay.

- concluding with sentimental, emotional, or hyperbolic commentary that is out of keeping with the analytical nature of the essay. Instead, offer your reader measured, thoughtful, and useful final comments that demonstrate your credibility as a writer.

We encourage you to further explore this topic via the articles and books under “Resources” below.

Booth, W.C., Colomb, G.G., Williams, J.M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W.T. (2016). The Craft of Research, Fourth Edition . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Casson, L.E. (2012). A Writer’s Handbook: Developing Writing Skills for University . Broadview Press.

Lori-Parks, S. (1998). Venus . Dramatists Play Service, Inc.

Sword, H. (2012). Stylish Academic Writing . Harvard University Press.

Turabian, K. (2018). A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. University of Chicago Press.

Conclusions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate conclusions you’ve drafted, and suggest approaches to avoid.

About conclusions

Introductions and conclusions can be difficult to write, but they’re worth investing time in. They can have a significant influence on a reader’s experience of your paper.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion:

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go: You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass. Friend: So what? You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen. Friend: Why should anybody care? You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally. You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize. Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help them to apply your info and ideas to their own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

Strategies to avoid

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

Four kinds of ineffective conclusions

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” them with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. New York: Dover.

Hamilton College. n.d. “Conclusions.” Writing Center. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.hamilton.edu//academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/conclusions .

Holewa, Randa. 2004. “Strategies for Writing a Conclusion.” LEO: Literacy Education Online. Last updated February 19, 2004. https://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Introductions and Conclusions

Have you ever read something that you couldn’t put down and then continued to think about it long after you finished? Good writing has that effect in general, but a strong introduction and conclusion are essential to engaging the reader from start to finish.

The introduction of a paper introduces the topic and scope of the discussion to prepare the reader for what follows, and the conclusion offers thoughtful analytic commentary or a synopsis that wraps up the discussion with final thoughts. In other words, the introduction and conclusion depend on everything that comes between them. With this in mind, an effective strategy for composing an introduction and a conclusion is to write everything that comes between them first. With the body of the paper drafted, you will know the topic well enough to introduce it effectively and you can also more readily determine where and how the discussion should end.

Consider the following characteristics of effective introductions and conclusions:

Characteristics of Effective Introductions

Provides relevant background information : Regardless of the topic, readers need a context to understand your remarks. A good introduction will include necessary background information about the topic that enables readers to understand the topic’s importance and why what you have to say about it matters. Providing context such as background information helps the reader feel grounded so that they can easily follow the development of the discussion.

Engages the reader : A good introduction will capture the attention of readers so that they want to read the paragraphs beyond the introduction. Enough specific information is presented so that readers are interested in the topic and what the writer plans to do with it. An engaging introduction invites readers into the world of the writing.

Sets the appropriate tone : The opening paragraph establishes the tone – the spirit and attitude behind the words – that the writer will use in a piece of writing. The tone should be a conscious choice as it reflects how the writer feels about the subject and about the audience, as well as the degree of formality of the writing. In most academic writing, the general tone is formal, but it may be more or less formal depending on the exact purpose of the writing. For example, a piece of writing with the purpose of introducing a new employee will probably be less formal and more personable than, say, a persuasive essay.

Establishes the focus and purpose : The introduction must make the focus and purpose of the paper clear to readers. Many writers include a thesis statement that establishes the focus and purpose and forecasts the main points. Even without an explicit thesis statement, the focus and purpose of the paper need to be just as clear. If readers do not understand the focus or what the writer hopes to accomplish, subsequent paragraphs may not make sense to readers.

Options for Introductions

The following is collection of some rhetorical strategies for writing introductions. Oftentimes an introduction will have characteristics of more than one strategy, so you should treat this list as a compilation of possibilities, not as a prescription of how certain types of beginnings must look. Try out a number of options to get a sense of the possibilities and then determine which would work best for your topic, purpose, and audience. The more you work on your introduction and think about what you are trying to say in your paper as a whole, the easier it will be to write an effective introduction.

Establish the Issue

Use the introduction to help make the case that the topic you are writing about is important and relevant and to provide context for your readers.

In the last decade or so, American culture has become increasingly tolerant of teenage sexuality. Many parents, too busy in their lives, are not proactive in educating their teens on issues related to sexuality. Educators are often left with the role of providing basic information about the subject even as more and more sexual education classes are cut from the curriculum. Where does this leave curious teens? Statistics show that 75 percent of teens have had sex by the time they are nineteen years old. The teenage birth rate continues to climb as do reported cases of sexually transmitted diseases (Healy, 2008). Cleary, it is imperative to develop intervention programs that teach adolescents the effective skills in delaying early sexual behaviors. Early education on delaying sexual activity for teens can drastically decrease teenage pregnancies, prevent the spread of STDs, and help teens to make the right choices that can impact the rest of their lives.

Asking relevant questions can be an excellent way to engage readers and get their attention. In the example below, the writer begins with a universal question that most readers can relate to.

Did you ever think that your life would change dramatically in a matter of twenty-four hours? One day you have a certain kind of life – a home, nearby schools for your kids, a wonderful neighborhood, good job, friends – and the next day it is all gone, irreversibly changed. As a resident of New Orleans, Louisiana, I had always known that a major hurricane could strike, but even knowing this fact could not prepare me for what happened in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Hurricane Katrina demonstrated the need for residents to evacuate when mandated, for local and state authorities to work more efficiently together, and for the federal government to respond in a timely and responsible manner.

Use a narrative Most people enjoy reading a good story, so beginning with a narrative can be an effective way to connect with your readers.

It was a dark and stormy night. The wind whipped through the trees while lightening flashed and thunder boomed. Up ahead on a hill, a rickety old house stood. In an upstairs window, a single, solitary light shone, casting an eerie shadow across the yard. I was in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on business, and was driving to the outskirts of the city to visit my aunt, an old woman I hadn’t seen in nearly twenty years. According to my directions, that rickety old house was my aunt’s house, but I didn’t know if I had the nerve to knock on the door. In fact, I couldn’t remember a time I had been more scared. Everyone experiences fear just as everyone experiences happiness or sadness. Fear is a natural human emotion to the unknown and is characterized by physical changes to the body, an innate need to escape, and acute awareness of one’s surroundings.

Use an Attention Getter

Begin with a statement that will catch your readers’ attention and makes them want to continue reading.

Some children cannot sit still. They appear distracted by every little thing and do not seem to learn from their mistakes. These children disregard rules, even when they are punished repeatedly. It’s simple—their parents must not know how to control them. The truth is that attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD is not understood appropriately. In fact, ADHD is a growing problem that requires more research to understand the issue, better intervention programs to help afflicted children, and improved training and support programs to help parents and educators.

Use an Extended Example or Series of Examples

Providing anecdotal examples can be a very effective way to capture your readers’ attention. Choose relevant, memorable examples.

According to the Federal Highway and Transportation Agency (2008), the majority of Americans, some 57%, do not regularly wear seat belts. Teddy Biro didn’t wear one when the car he was driving skidded on an icy road and hit a utility pole; Biro was catapulted through his front windshield and died of blood loss from a severed jugular vein. The coroner reported he had no other injuries besides minor abrasions. Bob Nettleblatt wasn’t wearing a seat belt when a car rear-ended him at a stop sign. Nettleblatt slammed his head into his front windshield and required 137 stitches to close up the laceration; investigators at the scene said if he had been wearing a seat belt, he would have been virtually unhurt from the 2 mph rear end collision (Fischer, 2007). Despite what is known about the safety of wearing seatbelts, too many Americans still do not buckle up, resulting in enormous emergency medical costs and fatalities that could be avoided. Despite what some people think, wearing a seatbelt is not a choice nor does it violate one’s personal rights. Wearing a seatbelt is the law and more needs to be done to enforce the law, punish those who break it, and educate young drivers to the dangers of not buckling up.

Define an Essential Term

To use this strategy, choose a term that is central to your paper and define it. This will help to engage your readers and make them want to continue reading. In the example below, the writer uses an extended example to define the term “collect.”