Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2018

Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study

- Simone Kühn 1 , 2 ,

- Dimitrij Tycho Kugler 2 ,

- Katharina Schmalen 1 ,

- Markus Weichenberger 1 ,

- Charlotte Witt 1 &

- Jürgen Gallinat 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 24 , pages 1220–1234 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

557k Accesses

110 Citations

2349 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

It is a widespread concern that violent video games promote aggression, reduce pro-social behaviour, increase impulsivity and interfere with cognition as well as mood in its players. Previous experimental studies have focussed on short-term effects of violent video gameplay on aggression, yet there are reasons to believe that these effects are mostly the result of priming. In contrast, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of long-term violent video gameplay using a large battery of tests spanning questionnaires, behavioural measures of aggression, sexist attitudes, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), mental health (depressivity, anxiety) as well as executive control functions, before and after 2 months of gameplay. Our participants played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto V, the non-violent video game The Sims 3 or no game at all for 2 months on a daily basis. No significant changes were observed, neither when comparing the group playing a violent video game to a group playing a non-violent game, nor to a passive control group. Also, no effects were observed between baseline and posttest directly after the intervention, nor between baseline and a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention period had ended. The present results thus provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games in adults and will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective on the effects of violent video gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

The associations between autistic characteristics and microtransaction spending

No effect of short term exposure to gambling like reward systems on post game risk taking

Increasing prosocial behavior and decreasing selfishness in the lab and everyday life

The concern that violent video games may promote aggression or reduce empathy in its players is pervasive and given the popularity of these games their psychological impact is an urgent issue for society at large. Contrary to the custom, this topic has also been passionately debated in the scientific literature. One research camp has strongly argued that violent video games increase aggression in its players [ 1 , 2 ], whereas the other camp [ 3 , 4 ] repeatedly concluded that the effects are minimal at best, if not absent. Importantly, it appears that these fundamental inconsistencies cannot be attributed to differences in research methodology since even meta-analyses, with the goal to integrate the results of all prior studies on the topic of aggression caused by video games led to disparate conclusions [ 2 , 3 ]. These meta-analyses had a strong focus on children, and one of them [ 2 ] reported a marginal age effect suggesting that children might be even more susceptible to violent video game effects.

To unravel this topic of research, we designed a randomised controlled trial on adults to draw causal conclusions on the influence of video games on aggression. At present, almost all experimental studies targeting the effects of violent video games on aggression and/or empathy focussed on the effects of short-term video gameplay. In these studies the duration for which participants were instructed to play the games ranged from 4 min to maximally 2 h (mean = 22 min, median = 15 min, when considering all experimental studies reviewed in two of the recent major meta-analyses in the field [ 3 , 5 ]) and most frequently the effects of video gaming have been tested directly after gameplay.

It has been suggested that the effects of studies focussing on consequences of short-term video gameplay (mostly conducted on college student populations) are mainly the result of priming effects, meaning that exposure to violent content increases the accessibility of aggressive thoughts and affect when participants are in the immediate situation [ 6 ]. However, above and beyond this the General Aggression Model (GAM, [ 7 ]) assumes that repeatedly primed thoughts and feelings influence the perception of ongoing events and therewith elicits aggressive behaviour as a long-term effect. We think that priming effects are interesting and worthwhile exploring, but in contrast to the notion of the GAM our reading of the literature is that priming effects are short-lived (suggested to only last for <5 min and may potentially reverse after that time [ 8 ]). Priming effects should therefore only play a role in very close temporal proximity to gameplay. Moreover, there are a multitude of studies on college students that have failed to replicate priming effects [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] and associated predictions of the so-called GAM such as a desensitisation against violent content [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] in adolescents and college students or a decrease of empathy [ 15 ] and pro-social behaviour [ 16 , 17 ] as a result of playing violent video games.

However, in our view the question that society is actually interested in is not: “Are people more aggressive after having played violent video games for a few minutes? And are these people more aggressive minutes after gameplay ended?”, but rather “What are the effects of frequent, habitual violent video game playing? And for how long do these effects persist (not in the range of minutes but rather weeks and months)?” For this reason studies are needed in which participants are trained over longer periods of time, tested after a longer delay after acute playing and tested with broader batteries assessing aggression but also other relevant domains such as empathy as well as mood and cognition. Moreover, long-term follow-up assessments are needed to demonstrate long-term effects of frequent violent video gameplay. To fill this gap, we set out to expose adult participants to two different types of video games for a period of 2 months and investigate changes in measures of various constructs of interest at least one day after the last gaming session and test them once more 2 months after the end of the gameplay intervention. In contrast to the GAM, we hypothesised no increases of aggression or decreases in pro-social behaviour even after long-term exposure to a violent video game due to our reasoning that priming effects of violent video games are short-lived and should therefore not influence measures of aggression if they are not measured directly after acute gaming. In the present study, we assessed potential changes in the following domains: behavioural as well as questionnaire measures of aggression, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), and depressivity and anxiety as well as executive control functions. As the effects on aggression and pro-social behaviour were the core targets of the present study, we implemented multiple tests for these domains. This broad range of domains with its wide coverage and the longitudinal nature of the study design enabled us to draw more general conclusions regarding the causal effects of violent video games.

Materials and methods

Participants.

Ninety healthy participants (mean age = 28 years, SD = 7.3, range: 18–45, 48 females) were recruited by means of flyers and internet advertisements. The sample consisted of college students as well as of participants from the general community. The advertisement mentioned that we were recruiting for a longitudinal study on video gaming, but did not mention that we would offer an intervention or that we were expecting training effects. Participants were randomly assigned to the three groups ruling out self-selection effects. The sample size was based on estimates from a previous study with a similar design [ 18 ]. After complete description of the study, the participants’ informed written consent was obtained. The local ethics committee of the Charité University Clinic, Germany, approved of the study. We included participants that reported little, preferably no video game usage in the past 6 months (none of the participants ever played the game Grand Theft Auto V (GTA) or Sims 3 in any of its versions before). We excluded participants with psychological or neurological problems. The participants received financial compensation for the testing sessions (200 Euros) and performance-dependent additional payment for two behavioural tasks detailed below, but received no money for the training itself.

Training procedure

The violent video game group (5 participants dropped out between pre- and posttest, resulting in a group of n = 25, mean age = 26.6 years, SD = 6.0, 14 females) played the game Grand Theft Auto V on a Playstation 3 console over a period of 8 weeks. The active control group played the non-violent video game Sims 3 on the same console (6 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 24, mean age = 25.8 years, SD = 6.8, 12 females). The passive control group (2 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 28, mean age = 30.9 years, SD = 8.4, 12 females) was not given a gaming console and had no task but underwent the same testing procedure as the two other groups. The passive control group was not aware of the fact that they were part of a control group to prevent self-training attempts. The experimenters testing the participants were blind to group membership, but we were unable to prevent participants from talking about the game during testing, which in some cases lead to an unblinding of experimental condition. Both training groups were instructed to play the game for at least 30 min a day. Participants were only reimbursed for the sessions in which they came to the lab. Our previous research suggests that the perceived fun in gaming was positively associated with training outcome [ 18 ] and we speculated that enforcing training sessions through payment would impair motivation and thus diminish the potential effect of the intervention. Participants underwent a testing session before (baseline) and after the training period of 2 months (posttest 1) as well as a follow-up testing sessions 2 months after the training period (posttest 2).

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA)

GTA is an action-adventure video game situated in a fictional highly violent game world in which players are rewarded for their use of violence as a means to advance in the game. The single-player story follows three criminals and their efforts to commit heists while under pressure from a government agency. The gameplay focuses on an open world (sandbox game) where the player can choose between different behaviours. The game also allows the player to engage in various side activities, such as action-adventure, driving, third-person shooting, occasional role-playing, stealth and racing elements. The open world design lets players freely roam around the fictional world so that gamers could in principle decide not to commit violent acts.

The Sims 3 (Sims)

Sims is a life simulation game and also classified as a sandbox game because it lacks clearly defined goals. The player creates virtual individuals called “Sims”, and customises their appearance, their personalities and places them in a home, directs their moods, satisfies their desires and accompanies them in their daily activities and by becoming part of a social network. It offers opportunities, which the player may choose to pursue or to refuse, similar as GTA but is generally considered as a pro-social and clearly non-violent game.

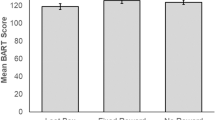

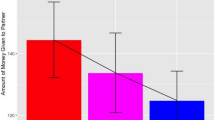

Assessment battery

To assess aggression and associated constructs we used the following questionnaires: Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [ 19 ], State Hostility Scale [ 20 ], Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [ 21 , 22 ], Moral Disengagement Scale [ 23 , 24 ], the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Test [ 25 , 26 ] and a so-called World View Measure [ 27 ]. All of these measures have previously been used in research investigating the effects of violent video gameplay, however, the first two most prominently. Additionally, behavioural measures of aggression were used: a Word Completion Task, a Lexical Decision Task [ 28 ] and the Delay frustration task [ 29 ] (an inter-correlation matrix is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 1). From these behavioural measures, the first two were previously used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay. To assess variables that have been related to the construct of impulsivity, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale [ 30 ] and the Boredom Propensity Scale [ 31 ] as well as tasks assessing risk taking and delay discounting behaviourally, namely the Balloon Analogue Risk Task [ 32 ] and a Delay-Discounting Task [ 33 ]. To quantify pro-social behaviour, we employed: Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 34 ] (frequently used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay), Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale [ 35 ], Reading the Mind in the Eyes test [ 36 ], Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire [ 37 ] and Richardson Conflict Response Questionnaire [ 38 ]. To assess depressivity and anxiety, which has previously been associated with intense video game playing [ 39 ], we used Beck Depression Inventory [ 40 ] and State Trait Anxiety Inventory [ 41 ]. To characterise executive control function, we used a Stop Signal Task [ 42 ], a Multi-Source Interference Task [ 43 ] and a Task Switching Task [ 44 ] which have all been previously used to assess effects of video gameplay. More details on all instruments used can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

On the basis of the research question whether violent video game playing enhances aggression and reduces empathy, the focus of the present analysis was on time by group interactions. We conducted these interaction analyses separately, comparing the violent video game group against the active control group (GTA vs. Sims) and separately against the passive control group (GTA vs. Controls) that did not receive any intervention and separately for the potential changes during the intervention period (baseline vs. posttest 1) and to test for potential long-term changes (baseline vs. posttest 2). We employed classical frequentist statistics running a repeated-measures ANOVA controlling for the covariates sex and age.

Since we collected 52 separate outcome variables and conduced four different tests with each (GTA vs. Sims, GTA vs. Controls, crossed with baseline vs. posttest 1, baseline vs. posttest 2), we had to conduct 52 × 4 = 208 frequentist statistical tests. Setting the alpha value to 0.05 means that by pure chance about 10.4 analyses should become significant. To account for this multiple testing problem and the associated alpha inflation, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. According to Bonferroni, the critical value for the entire set of n tests is set to an alpha value of 0.05 by taking alpha/ n = 0.00024.

Since the Bonferroni correction has sometimes been criticised as overly conservative, we conducted false discovery rate (FDR) correction [ 45 ]. FDR correction also determines adjusted p -values for each test, however, it controls only for the number of false discoveries in those tests that result in a discovery (namely a significant result).

Moreover, we tested for group differences at the baseline assessment using independent t -tests, since those may hamper the interpretation of significant interactions between group and time that we were primarily interested in.

Since the frequentist framework does not enable to evaluate whether the observed null effect of the hypothesised interaction is indicative of the absence of a relation between violent video gaming and our dependent variables, the amount of evidence in favour of the null hypothesis has been tested using a Bayesian framework. Within the Bayesian framework both the evidence in favour of the null and the alternative hypothesis are directly computed based on the observed data, giving rise to the possibility of comparing the two. We conducted Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVAs comparing the model in favour of the null and the model in favour of the alternative hypothesis resulting in a Bayes factor (BF) using Bayesian Information criteria [ 46 ]. The BF 01 suggests how much more likely the data is to occur under the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using the JASP software package ( https://jasp-stats.org ).

Sex distribution in the present study did not differ across the groups ( χ 2 p -value > 0.414). However, due to the fact that differences between males and females have been observed in terms of aggression and empathy [ 47 ], we present analyses controlling for sex. Since our random assignment to the three groups did result in significant age differences between groups, with the passive control group being significantly older than the GTA ( t (51) = −2.10, p = 0.041) and the Sims group ( t (50) = −2.38, p = 0.021), we also controlled for age.

The participants in the violent video game group played on average 35 h and the non-violent video game group 32 h spread out across the 8 weeks interval (with no significant group difference p = 0.48).

To test whether participants assigned to the violent GTA game show emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes, we present the results of repeated-measure ANOVA time x group interaction analyses separately for GTA vs. Sims and GTA vs. Controls (Tables 1 – 3 ). Moreover, we split the analyses according to the time domain into effects from baseline assessment to posttest 1 (Table 2 ) and effects from baseline assessment to posttest 2 (Table 3 ) to capture more long-lasting or evolving effects. In addition to the statistical test values, we report partial omega squared ( ω 2 ) as an effect size measure. Next to the classical frequentist statistics, we report the results of a Bayesian statistical approach, namely BF 01 , the likelihood with which the data is to occur under the null hypothesis that there is no significant time × group interaction. In Table 2 , we report the presence of significant group differences at baseline in the right most column.

Since we conducted 208 separate frequentist tests we expected 10.4 significant effects simply by chance when setting the alpha value to 0.05. In fact we found only eight significant time × group interactions (these are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 ).

When applying a conservative Bonferroni correction, none of those tests survive the corrected threshold of p < 0.00024. Neither does any test survive the more lenient FDR correction. The arithmetic mean of the frequentist test statistics likewise shows that on average no significant effect was found (bottom rows in Tables 2 and 3 ).

In line with the findings from a frequentist approach, the harmonic mean of the Bayesian factor BF 01 is consistently above one but not very far from one. This likewise suggests that there is very likely no interaction between group × time and therewith no detrimental effects of the violent video game GTA in the domains tested. The evidence in favour of the null hypothesis based on the Bayes factor is not massive, but clearly above 1. Some of the harmonic means are above 1.6 and constitute substantial evidence [ 48 ]. However, the harmonic mean has been criticised as unstable. Owing to the fact that the sum is dominated by occasional small terms in the likelihood, one may underestimate the actual evidence in favour of the null hypothesis [ 49 ].

To test the sensitivity of the present study to detect relevant effects we computed the effect size that we would have been able to detect. The information we used consisted of alpha error probability = 0.05, power = 0.95, our sample size, number of groups and of measurement occasions and correlation between the repeated measures at posttest 1 and posttest 2 (average r = 0.68). According to G*Power [ 50 ], we could detect small effect sizes of f = 0.16 (equals η 2 = 0.025 and r = 0.16) in each separate test. When accounting for the conservative Bonferroni-corrected p -value of 0.00024, still a medium effect size of f = 0.23 (equals η 2 = 0.05 and r = 0.22) would have been detectable. A meta-analysis by Anderson [ 2 ] reported an average effects size of r = 0.18 for experimental studies testing for aggressive behaviour and another by Greitmeyer [ 5 ] reported average effect sizes of r = 0.19, 0.25 and 0.17 for effects of violent games on aggressive behaviour, cognition and affect, all of which should have been detectable at least before multiple test correction.

Within the scope of the present study we tested the potential effects of playing the violent video game GTA V for 2 months against an active control group that played the non-violent, rather pro-social life simulation game The Sims 3 and a passive control group. Participants were tested before and after the long-term intervention and at a follow-up appointment 2 months later. Although we used a comprehensive test battery consisting of questionnaires and computerised behavioural tests assessing aggression, impulsivity-related constructs, mood, anxiety, empathy, interpersonal competencies and executive control functions, we did not find relevant negative effects in response to violent video game playing. In fact, only three tests of the 208 statistical tests performed showed a significant interaction pattern that would be in line with this hypothesis. Since at least ten significant effects would be expected purely by chance, we conclude that there were no detrimental effects of violent video gameplay.

This finding stands in contrast to some experimental studies, in which short-term effects of violent video game exposure have been investigated and where increases in aggressive thoughts and affect as well as decreases in helping behaviour have been observed [ 1 ]. However, these effects of violent video gaming on aggressiveness—if present at all (see above)—seem to be rather short-lived, potentially lasting <15 min [ 8 , 51 ]. In addition, these short-term effects of video gaming are far from consistent as multiple studies fail to demonstrate or replicate them [ 16 , 17 ]. This may in part be due to problems, that are very prominent in this field of research, namely that the outcome measures of aggression and pro-social behaviour, are poorly standardised, do not easily generalise to real-life behaviour and may have lead to selective reporting of the results [ 3 ]. We tried to address these concerns by including a large set of outcome measures that were mostly inspired by previous studies demonstrating effects of short-term violent video gameplay on aggressive behaviour and thoughts, that we report exhaustively.

Since effects observed only for a few minutes after short sessions of video gaming are not representative of what society at large is actually interested in, namely how habitual violent video gameplay affects behaviour on a more long-term basis, studies employing longer training intervals are highly relevant. Two previous studies have employed longer training intervals. In an online study, participants with a broad age range (14–68 years) have been trained in a violent video game for 4 weeks [ 52 ]. In comparison to a passive control group no changes were observed, neither in aggression-related beliefs, nor in aggressive social interactions assessed by means of two questions. In a more recent study, participants played a previous version of GTA for 12 h spread across 3 weeks [ 53 ]. Participants were compared to a passive control group using the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, a questionnaire assessing impulsive or reactive aggression, attitude towards violence, and empathy. The authors only report a limited increase in pro-violent attitude. Unfortunately, this study only assessed posttest measures, which precludes the assessment of actual changes caused by the game intervention.

The present study goes beyond these studies by showing that 2 months of violent video gameplay does neither lead to any significant negative effects in a broad assessment battery administered directly after the intervention nor at a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention. The fact that we assessed multiple domains, not finding an effect in any of them, makes the present study the most comprehensive in the field. Our battery included self-report instruments on aggression (Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, State Hostility scale, Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance scale, Moral Disengagement scale, World View Measure and Rosenzweig Picture Frustration test) as well as computer-based tests measuring aggressive behaviour such as the delay frustration task and measuring the availability of aggressive words using the word completion test and a lexical decision task. Moreover, we assessed impulse-related concepts such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness and associated behavioural measures such as the computerised Balloon analogue risk task, and delay discounting. Four scales assessing empathy and interpersonal competence scales, including the reading the mind in the eyes test revealed no effects of violent video gameplay. Neither did we find any effects on depressivity (Becks depression inventory) nor anxiety measured as a state as well as a trait. This is an important point, since several studies reported higher rates of depressivity and anxiety in populations of habitual video gamers [ 54 , 55 ]. Last but not least, our results revealed also no substantial changes in executive control tasks performance, neither in the Stop signal task, the Multi-source interference task or a Task switching task. Previous studies have shown higher performance of habitual action video gamers in executive tasks such as task switching [ 56 , 57 , 58 ] and another study suggests that training with action video games improves task performance that relates to executive functions [ 59 ], however, these associations were not confirmed by a meta-analysis in the field [ 60 ]. The absence of changes in the stop signal task fits well with previous studies that likewise revealed no difference between in habitual action video gamers and controls in terms of action inhibition [ 61 , 62 ]. Although GTA does not qualify as a classical first-person shooter as most of the previously tested action video games, it is classified as an action-adventure game and shares multiple features with those action video games previously related to increases in executive function, including the need for hand–eye coordination and fast reaction times.

Taken together, the findings of the present study show that an extensive game intervention over the course of 2 months did not reveal any specific changes in aggression, empathy, interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs, depressivity, anxiety or executive control functions; neither in comparison to an active control group that played a non-violent video game nor to a passive control group. We observed no effects when comparing a baseline and a post-training assessment, nor when focussing on more long-term effects between baseline and a follow-up interval 2 months after the participants stopped training. To our knowledge, the present study employed the most comprehensive test battery spanning a multitude of domains in which changes due to violent video games may have been expected. Therefore the present results provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games. This debate has mostly been informed by studies showing short-term effects of violent video games when tests were administered immediately after a short playtime of a few minutes; effects that may in large be caused by short-lived priming effects that vanish after minutes. The presented results will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective of the real-life effects of violent video gaming. However, future research is needed to demonstrate the absence of effects of violent video gameplay in children.

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: a meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:353–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, et al. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:151–73.

Article Google Scholar

Ferguson CJ. Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:646–66.

Ferguson CJ, Kilburn J. Much ado about nothing: the misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: comment on Anderson et al. (2010). Psychol Bull. 2010;136:174–8.

Greitemeyer T, Mugge DO. Video games do affect social outcomes: a meta-analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:578–89.

Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J. Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:960–71.

DeWall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1:245–58.

Sestire MA, Bartholow BD. Violent and non-violent video games produce opposing effects on aggressive and prosocial outcomes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:934–42.

Kneer J, Elson M, Knapp F. Fight fire with rainbows: The effects of displayed violence, difficulty, and performance in digital games on affect, aggression, and physiological arousal. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;54:142–8.

Kneer J, Glock S, Beskes S, Bente G. Are digital games perceived as fun or danger? Supporting and suppressing different game-related concepts. Cyber Beh Soc N. 2012;15:604–9.

Sauer JD, Drummond A, Nova N. Violent video games: the effects of narrative context and reward structure on in-game and postgame aggression. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2015;21:205–14.

Ballard M, Visser K, Jocoy K. Social context and video game play: impact on cardiovascular and affective responses. Mass Commun Soc. 2012;15:875–98.

Read GL, Ballard M, Emery LJ, Bazzini DG. Examining desensitization using facial electromyography: violent video games, gender, and affective responding. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;62:201–11.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Hake M, Kneer J, Samii A, Munte TF, et al. Excessive users of violent video games do not show emotional desensitization: an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11:736–43.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Munte TF, Te Wildt BT. Lack of evidence that neural empathic responses are blunted in excessive users of violent video games: an fMRI study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:174.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Failure to demonstrate that playing violent video games diminishes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68382.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Video games and prosocial behavior: a study of the effects of non-violent, violent and ultra-violent gameplay. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:8–13.

Kühn S, Gleich T, Lorenz RC, Lindenberger U, Gallinat J. Playing super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:265–71.

Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452.

Anderson CA, Deuser WE, DeNeve KM. Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:434–48.

Payne DL, Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myth acceptance: exploration of its structure and its measurement using the illinois rape myth acceptance scale. J Res Pers. 1999;33:27–68.

McMahon S, Farmer GL. An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Res. 2011; 35:71–81.

Detert JR, Trevino LK, Sweitzer VL. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:374–91.

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:364–74.

Rosenzweig S. The picture-association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustration. J Pers. 1945;14:23.

Hörmann H, Moog W, Der Rosenzweig P-F. Test für Erwachsene deutsche Bearbeitung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1957.

Anderson CA, Dill KE. Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:772–90.

Przybylski AK, Deci EL, Rigby CS, Ryan RM. Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:441.

Bitsakou P, Antrop I, Wiersema JR, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Probing the limits of delay intolerance: preliminary young adult data from the Delay Frustration Task (DeFT). J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151:38–44.

Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:401–14.

Farmer R, Sundberg ND. Boredom proneness: the development and correlates of a new scale. J Pers Assess. 1986;50:4–17.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl. 2002;8:75–84.

Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. J Exp Anal Behav. 1999;71:121–43.

Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

Google Scholar

Mehrabian A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES). (Available from Albert Mehrabian, 1130 Alta Mesa Road, Monterey, CA, USA 93940); 1996.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:241–51.

Buhrmester D, Furman W, Reis H, Wittenberg MT. Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:991–1008.

Richardson DR, Green LR, Lago T. The relationship between perspective-taking and non-aggressive responding in the face of an attack. J Pers. 1998;66:235–56.

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med. 2015;73:133–8.

Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Worall H, Keller F. Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI). Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI): Testhandbuch der deutschen Ausgabe. Bern: Huber; 1995.

Spielberger CD, Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999.

Lorenz RC, Gleich T, Buchert R, Schlagenhauf F, Kuhn S, Gallinat J. Interactions between glutamate, dopamine, and the neuronal signature of response inhibition in the human striatum. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4031–40.

Bush G, Shin LM. The multi-source interference task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:308–13.

King JA, Colla M, Brass M, Heuser I, von Cramon D. Inefficient cognitive control in adult ADHD: evidence from trial-by-trial Stroop test and cued task switching performance. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:42.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300.

Wagenmakers E-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:779–804.

Hay DF. The gradual emergence of sex differences in aggression: alternative hypotheses. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1527–37.

Jeffreys H. The Theory of Probability. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1961.

Raftery AE, Newton MA, Satagopan YM, Krivitsky PN. Estimating the integrated likelihood via posterior simulation using the harmonic mean identity. In: Bernardo JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman D, Smith AFM, et al., editors. Bayesian statistics. Oxford: University Press; 2007.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Barlett C, Branch O, Rodeheffer C, Harris R. How long do the short-term violent video game effects last? Aggress Behav. 2009;35:225–36.

Williams D, Skoric M. Internet fantasy violence: a test of aggression in an online game. Commun Monogr. 2005;72:217–33.

Teng SK, Chong GY, Siew AS, Skoric MM. Grand theft auto IV comes to Singapore: effects of repeated exposure to violent video games on aggression. Cyber Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:597–602.

van Rooij AJ, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Shorter GW, Schoenmakers TM, Van, de Mheen D. The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:157–65.

Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Froyland LR. Is video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, or conduct problems? J Behav Addict. 2014;3:27–32.

Green CS, Sugarman MA, Medford K, Klobusicky E, Bavelier D. The effect of action video game experience on task switching. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:984–94.

Strobach T, Frensch PA, Schubert T. Video game practice optimizes executive control skills in dual-task and task switching situations. Acta Psychol. 2012;140:13–24.

Colzato LS, van Leeuwen PJ, van den Wildenberg WP, Hommel B. DOOM’d to switch: superior cognitive flexibility in players of first person shooter games. Front Psychol. 2010;1:8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hutchinson CV, Barrett DJK, Nitka A, Raynes K. Action video game training reduces the Simon effect. Psychon B Rev. 2016;23:587–92.

Powers KL, Brooks PJ, Aldrich NJ, Palladino MA, Alfieri L. Effects of video-game play on information processing: a meta-analytic investigation. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20:1055–79.

Colzato LS, van den Wildenberg WP, Zmigrod S, Hommel B. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improvement in working memory but not action inhibition. Psychol Res. 2013;77:234–9.

Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Beste C, Colzato LS. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improved action cascading but not inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144364.

Download references

Acknowledgements

SK has been funded by a Heisenberg grant from the German Science Foundation (DFG KU 3322/1-1, SFB 936/C7), the European Union (ERC-2016-StG-Self-Control-677804) and a Fellowship from the Jacobs Foundation (JRF 2016–2018).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Lentzeallee 94, 14195, Berlin, Germany

Simone Kühn, Katharina Schmalen, Markus Weichenberger & Charlotte Witt

Clinic and Policlinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Clinic Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistraße 52, 20246, Hamburg, Germany

Simone Kühn, Dimitrij Tycho Kugler & Jürgen Gallinat

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simone Kühn .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kühn, S., Kugler, D., Schmalen, K. et al. Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study. Mol Psychiatry 24 , 1220–1234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Download citation

Received : 19 August 2017

Revised : 03 January 2018

Accepted : 15 January 2018

Published : 13 March 2018

Issue Date : August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Far from the future: internet addiction association with delay discounting among adolescence.

- Huaiyuan Qi

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2024)

The effect of competitive context in nonviolent video games on aggression: The mediating role of frustration and the moderating role of gender

- Jinqian Liao

- Yanling Liu

Current Psychology (2024)

Geeks versus climate change: understanding American video gamers’ engagement with global warming

- Jennifer P. Carman

- Marina Psaros

- Anthony Leiserowitz

Climatic Change (2024)

Exposure to hate speech deteriorates neurocognitive mechanisms of the ability to understand others’ pain

- Agnieszka Pluta

- Joanna Mazurek

- Michał Bilewicz

Scientific Reports (2023)

The effects of violent video games on reactive-proactive aggression and cyberbullying

- Yunus Emre Dönmez

Current Psychology (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

October 2, 2018

Do Violent Video Games Trigger Aggression?

A study tries to find whether slaughtering zombies with a virtual assault weapon translates into misbehavior when a teenager returns to reality

By Melinda Wenner Moyer

Getty Images

Intuitively, it makes sense Splatterhouse and Postal 2 would serve as virtual training sessions for teens, encouraging them to act out in ways that mimic game-related violence. But many studies have failed to find a clear connection between violent game play and belligerent behavior, and the controversy over whether the shoot-‘em-up world transfers to real life has persisted for years. A new study published on October 1 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences tries to resolve the controversy by weighing the findings of two dozen studies on the topic.

The meta-analysis does tie violent video games to a small increase in physical aggression among adolescents and preteens. Yet debate is by no means over. Whereas the analysis was undertaken to help settle the science on the issue, researchers still disagree on the real-world significance of the findings.

This new analysis attempted to navigate through the minefield of conflicting research. Many studies find gaming associated with increases in aggression, but others identify no such link. A small but vocal cadre of researchers have argued much of the work implicating video games has serious flaws in that, among other things, it measures the frequency of aggressive thoughts or language rather than physically aggressive behaviors like hitting or pushing, which have more real-world relevance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Jay Hull, a social psychologist at Dartmouth College and a co-author on the new paper, has never been convinced by the critiques that have disparaged purported ties between gaming and aggression. “I just kept reading, over and over again, [these] criticisms of the literature and going, ‘that’s just not true,’” he says. So he and his colleagues designed the new meta-analysis to address these criticisms head-on and determine if they had merit.

Hull and colleagues pooled data from 24 studies that had been selected to avoid some of the criticisms leveled at earlier work. They only included research that measured the relationship between violent video game use and overt physical aggression. They also limited their analysis to studies that statistically controlled for several factors that could influence the relationship between gaming and subsequent behavior, such as age and baseline aggressive behavior.

Even with these constraints, their analysis found kids who played violent video games did become more aggressive over time. But the changes in behavior were not big. “According to traditional ways of looking at these numbers, it’s not a large effect—I would say it’s relatively small,” he says. But it’s “statistically reliable—it’s not by chance and not inconsequential.”

Their findings mesh with a 2015 literature review conducted by the American Psychological Association, which concluded violent video games worsen aggressive behavior in older children, adolescents and young adults. Together, Hull’s meta-analysis and the APA report help give clarity to the existing body of research, says Douglas Gentile, a developmental psychologist at Iowa State University who was not involved in conducting the meta-analysis. “Media violence is one risk factor for aggression,” he says. “It's not the biggest, it’s also not the smallest, but it’s worth paying attention to.”

Yet researchers who have been critical of links between games and violence contend Hull’s meta-analysis does not settle the issue. “They don’t find much. They just try to make it sound like they do,” says Christopher Ferguson, a psychologist at Stetson University in Florida, who has published papers questioning the link between violent video games and aggression.

Ferguson argues the degree to which video game use increases aggression in Hull’s analysis—what is known in psychology as the estimated “effect size”—is so small as to be essentially meaningless. After statistically controlling for several other factors, the meta-analysis reported an effect size of 0.08, which suggests that violent video games account for less than one percent of the variation in aggressive behavior among U.S. teens and pre-teens—if, in fact, there is a cause-and effect relationship between game play and hostile actions. It may instead be that the relationship between gaming and aggression is a statistical artifact caused by lingering flaws in study design, Ferguson says.

Johannes Breuer, a psychologist at GESIS–Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences in Germany, agrees, noting that according to “a common rule of thumb in psychological research,” effect sizes below 0.1 are “considered trivial.” He adds meta-analyses are only as valid as the studies included in them, and that work on the issue has been plagued by methodological problems. For one thing, studies vary in terms of the criteria they use to determine if a video game is violent or not. By some measures, the Super Mario Bros. games would be considered violent, but by others not. Studies, too, often rely on subjects self-reporting their own aggressive acts, and they may not do so accurately. “All of this is not to say that the results of this meta-analysis are not valid,” he says. “But things like this need to be kept in mind when interpreting the findings and discussing their meaning.”

Hull says, however, that the effect size his team found still has real-world significance. An analysis of one of his earlier studies, which reported a similar estimated effect size of 0.083, found playing violent video games was linked with almost double the risk that kids would be sent to the school principal’s office for fighting. The study began by taking a group of children who hadn’t been dispatched to the principal in the previous month and then tracked them for a subsequent eight months. It found 4.8 percent of kids who reported only rarely playing violent video games were sent to the principal’s office at least once during that period compared with 9 percent who reported playing violent video games frequently. Hull theorizes violent games help kids become more comfortable with taking risks and engaging in abnormal behavior. “Their sense of right and wrong is being warped,” he notes.

Hull and his colleagues also found evidence ethnicity shapes the relationship between violent video games and aggression. White players seem more susceptible to the games' putative effects on behavior than do Hispanic and Asian players. Hull isn’t sure why, but he suspects the games' varying impact relates to how much kids are influenced by the norms of American culture, which, he says, are rooted in rugged individualism and a warriorlike mentality that may incite video game players to identify with aggressors rather than victims. It might “dampen sympathy toward their virtual victims,” he and his co-authors wrote, “with consequences for their values and behavior outside the game.”

Social scientists will, no doubt, continue to debate the psychological impacts of killing within the confines of interactive games. In a follow-up paper Hull says he plans to tackle the issue of the real-world significance of violent game play, and hopes it adds additional clarity. “It’s a knotty issue,” he notes—and it’s an open question whether research will ever quell the controversy.

Do Violent Video Games Contribute to Youth Violence?

Around 73% of American kids age 2-17 played video games in 2019, a 6% increase over 2018. Video games accounted for 17% of kids’ entertainment time and 11% of their entertainment spending. The global video game industry was worth contributing $159.3 billion in 2020, a 9.3% increase of 9.3% from 2019.

Violent video games have been blamed for school shootings , increases in bullying , and violence towards women. Critics argue that these games desensitize players to violence, reward players for simulating violence, and teach children that violence is an acceptable way to resolve conflicts.

Video game advocates contend that a majority of the research on the topic is deeply flawed and that no causal relationship has been found between video games and social violence. They argue that violent video games may provide a safe outlet for aggressive and angry feelings and may reduce crime. Read more background…

Pro & Con Arguments

Pro 1 Playing violent video games causes more aggression, bullying, and fighting. 60% of middle school boys and 40% of middle school girls who played at least one Mature-rated (M-rated) game hit or beat up someone, compared with 39% of boys and 14% of girls who did not play M-rated games. [ 2 ] A peer-reviewed study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that habitual violent video game playing had a causal link with increased, long-term, aggressive behavior. [ 63 ] Several peer-reviewed studies have shown that children who play M-rated games are more likely to bully and cyberbully their peers, get into physical fights, be hostile, argue with teachers, and show aggression towards their peers throughout the school year. [ 2 ] [ 31 ] [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ 67 ] [ 73 ] [ 76 ] [ 80 ] Read More

Pro 2 Simulating violence such as shooting guns and hand-to-hand combat in video games can cause real-life violent behavior. Video games often require players to simulate violent actions, such as stabbing, shooting, or dismembering someone with an ax, sword, chainsaw, or other weapons. [ 23 ] Game controllers are so sophisticated and the games are so realistic that simulating the violent acts enhances the learning of those violent behaviors. [ 23 ] A peer-reviewed study found “compelling evidence that the use of realistic controllers can have a significant effect on the level of cognitive aggression.” [ 118 ] Two teenagers in Tennessee who shot at passing cars and killed one driver told police they got the idea from playing Grand Theft Auto III . [ 48 ] Bruce Bartholow, professor of psychology at the University of Missouri, spoke about the effects of simulating violence: “More than any other media, these [violent] video games encourage active participation in violence. From a psychological perspective, video games are excellent teaching tools because they reward players for engaging in certain types of behavior. Unfortunately, in many popular video games, the behavior is violence.” [ 53 ] Read More

Pro 3 Many perpetrators of mass shootings played violent video games. Kevin McCarthy, former U.S. Representative (R-CA), states: “But the idea of these video games that dehumanize individuals to have a game of shooting individuals and others – I’ve always felt that is a problem for future generations and others. We’ve watched from studies shown before of what it does to individuals. When you look at these photos of how it [mass shootings] took place, you can see the actions within video games and others.” [ 146 ] Many mass shootings have been carried out by avid video game players: Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold in the Columbine High School shooting (1999); James Holmes in the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooting (2012); Jared Lee Loughner in the Arizona shooting that injured Rep. Gabby Giffords and killed six others (2011); and Anders Breivik, who killed 77 people in Norway (2011) and admitted to using the game Modern Warfare 2 for training. [ 43 ] [ 53 ] An FBI school shooter threat assessment stated that a student who makes threats of violence should be considered more credible if he or she also spends “inordinate amounts of time playing video games with violent themes.” [ 25 ] Dan Patrick, Republican Lieutenant Governor of Texas, stated: “We’ve always had guns, always had evil, but I see a video game industry that teaches young people to kill.” [ 145 ] Read More

Pro 4 Violent video games desensitize players to real-life violence. Desensitization to violence was defined in a Journal of Experimental Social Psychology peer-reviewed study as “a reduction in emotion-related physiological reactivity to real violence.” [ 51 ] [ 111 ] [ 112 ] The study found that just 20 minutes of playing a violent video game “can cause people to become less physiologically aroused by real violence.” People desensitized to violence are more likely to commit a violent act. [ 51 ] [ 111 ] [ 112 ] By age 18, American children will have seen 16,000 murders and 200,000 acts of violence depicted in violent video games, movies, and television. [ 110 ] A peer-reviewed study found a causal link between violent video game exposure and an increase in aggression as a result of a reduction in the brain’s response to depictions of real-life violence. [ 52 ] Studies have found reduced emotional and physiological responses to violence in both the long and short term. [ 55 ] [ 58 ] In a peer-reviewed study, violent video game exposure was linked to reduced P300 amplitudes in the brain, which is associated with desensitization to violence and increases in aggressive behavior. [ 24 ] Read More

Pro 5 By inhabiting violent characters in video games, children are more likely to imitate the behaviors of those characters and have difficulty distinguishing reality from fantasy. Violent video games require active participation and identification with violent characters, which reinforces violent behavior. Young children are more likely to confuse fantasy violence with real world violence, and without a framework for ethical decision making, they may mimic the actions they see in violent video games. [ 59 ] [ 4 ] Child Development and Early Childhood Education expert Jane Katch stated in an interview with Education Week , “I found that young children often have difficulty separating fantasy from reality when they are playing and can temporarily believe they are the character they are pretending to be.” [ 124 ] U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer wrote in his dissent in Brown v. ESA that “the closer a child’s behavior comes, not to watching, but to acting out horrific violence, the greater the potential psychological harm.” [ 124 ] Read More

Pro 6 Exposure to violent video games is linked to lower empathy and decreased kindness. Empathy, the ability to understand and enter into another’s feelings is believed to inhibit aggressive behavior. In a study of 150 fourth and fifth graders by Jeanne Funk, professor of psychology at the University of Toledo, violent video games were the only type of media associated with lower empathy. [ 32] A study published in the American Psychological Association’s Psychological Bulletin found that exposure to violent video games led to a lack of empathy and prosocial behavior (positive actions that benefit others). [ 65] [ 66] Eight independent tests measuring the impact of violent video games on prosocial behavior found a significant negative effect, leading to the conclusion that “exposure to violent video games is negatively correlated with helping in the real world.” [ 61] Several studies have found that children with high exposure to violent media display lower moral reasoning skills than their peers without that exposure. [ 32] [ 69] A meta-analysis of 130 international studies with over 130,000 participants concluded that violent video games “increase aggressive thoughts, angry feelings, and aggressive behaviors, and decrease empathic feelings and prosocial behaviors.” [ 123] Read More

Pro 7 Video games that portray violence against women lead to more harmful attitudes and sexually violent actions towards women. A peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence found that video games that sexually objectify women and feature violence against women led to a statistically significant increase in rape-supportive attitudes, which are attitudes that are hostile towards rape victims. [ 68 ] Another study found that 21% of games sampled involved violence against women, while 28% portrayed them as sex objects. [ 23 ] Exposure to sexual violence in video games is linked to increases in violence towards women and false attitudes about rape, such as that women incite men to rape or that women secretly desire rape. [ 30 ] Carole Lieberman, a media psychiatrist, stated, “The more video games a person plays that have violent sexual content, the more likely one is to become desensitized to violent sexual acts and commit them.” [ 64 ] Target Australia stopped selling Grand Theft Auto V in response to customer complaints about the game’s depiction of women, which includes the option to kill a prostitute to get your money back. [ 70 ] Read More

Pro 8 Violent video games reinforce fighting as a means of dealing with conflict by rewarding the use of violent action with increased life force, more weapons, moving on to higher levels, and more. Studies suggest that when violence is rewarded in video games, players exhibit increased aggressive behavior compared to players of video games where violence is punished. [ 23 ] [ 59 ] The reward structure is one distinguishing factor between violent video games and other violent media such as movies and television shows, which do not reward viewers nor allow them to actively participate in violence. [ 23 ] [ 59 ] An analysis of 81 video games rated for teens ages 13 and up found that 73 games (90%) rewarded injuring other characters, and 56 games (69%) rewarded killing. [ 71 ] [ 72 ] People who played a video game that rewarded violence showed higher levels of aggressive behavior and aggressive cognition as compared with people who played a version of the same game that was competitive but either did not contain violence or punished violence. [ 71 ] [ 72 ] Read More

Pro 9 The US military uses violent video games to train soldiers to kill. The U.S. Marine Corps licensed Doom II in 1996 to create Marine Doom in order to train soldiers. In 2002, the U.S. Army released first-person shooter game America’s Army to recruit soldiers and prepare recruits for the battlefield. [ 6 ] While the military may benefit from training soldiers to kill using video games, kids who are exposed to these games lack the discipline and structure of the armed forces and may become more susceptible to being violent. [ 79 ] Dave Grossman, retired lieutenant colonel in the United States Army and former West Point psychology professor, stated: “[T]hrough interactive point-and-shoot video games, modern nations are indiscriminately introducing to their children the same weapons technology that major armies and law enforcement agencies around the world use to ‘turn off’ the midbrain ‘safety catch’” that prevents most people from killing. [ 77 ] Read More

Con 1 Studies have shown violent video games may cause aggression, not violence. Further, any competitive video game or activity may cause aggression. Lauren Farrar, producer for KQED Learning’s YouTube series Above the Noise , stated: “Often times after tragic mass shooting, we hear politicians turn the blame to violent video games, but the reality is that the research doesn’t really support that claim… In general, violence usually refers to physical harm or physical acts that hurt someone– like hitting, kicking, punching, and pushing. Aggression is a more broad term that refers to angry or hostile thoughts, feelings or behaviors. So everything that is violent is aggressive, but not everything that is aggressive is violent. For example, getting frustrated, yelling, talking back, arguing those are all aggressive behaviors, but they aren’t violent. The research on the effects of violent video games and behavior often looks at these milder forms of aggressive behavior.” [ 140 ] A peer-reviewed study in Psychology of Violence determined that the competitive nature of a video game was related to aggressive behavior, regardless of whether the game contained violent content. The researchers concluded: “Because past studies have failed to equate the violent and nonviolent video games on competitiveness, difficulty, and pace of action simultaneously, researchers may have attributed too much of the variability in aggression to the violent content.” [ 125 ] A follow-up study tracked high school students for four years and came to the same conclusion: the competitive nature of the games led to the increased hostile behavior. [ 126 ] Read More

Con 2 Violent video games are a convenient scapegoat for those who would rather not deal with the actual causes of violence in the US. Patrick Markey, psychology professor at Villanova University, stated: “The general story is people who play video games right after might be a little hopped up and jerky but it doesn’t fundamentally alter who they are. It is like going to see a sad movie. It might make you cry but it doesn’t make you clinically depressed… Politicians on both sides go after video games it is this weird unifying force. It makes them look like they are doing something… They [violent video games] look scary. But research just doesn’t support that there’s a link [to violent behavior].” [ 138 ] Markey also explained, “Because video games are disproportionately blamed as a culprit for mass shootings committed by White perpetrators, video game ‘blaming’ can be viewed as flagging a racial issue. This is because there is a stereotypical association between racial minorities and violent crime.” [ 141 ] Andrew Przybylski, associate professor, and director of research at the Oxford Internet Institute at Oxford University, stated: “Games have only become more realistic. The players of games and violent games have only become more diverse. And they’re played all around the world now. But the only place where you see this kind of narrative still hold any water, that games and violence are related to each other, is in the United States. [And, by blaming video games for violence,] we reduce the value of the political discourse on the topic, because we’re looking for easy answers instead of facing hard truths.” [ 139 ] Hillary Clinton, Former Secretary of State and First Lady, tweeted, “People suffer from mental illness in every other country on earth; people play video games in virtually every other country on earth. The difference is the guns.” [ 142 ] Read More

Con 3 Simple statistics do not support the claim that violent video games cause mass shootings or other violence. Katherine Newman, dean of arts and sciences at Johns Hopkins University, explained: “Millions of young people play video games full of fistfights, blazing guns, and body slams… Yet only a minuscule fraction of the consumers become violent.” [ 84 ] [ 86 ] [ 87 ] [ 91 ] [ 92 ] A report by the U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education examined 37 incidents of targeted school violence between 1974 and 2000. Of the 41 attackers studied, 27% had an interest in violent movies, 24% in violent books, and 37% exhibited interest in their own violent writings, while only 12% showed interest in violent video games. The report did not find a relationship between playing violent video games and school shootings. [ 35 ] Patrick M. Markey, director of the Interpersonal Research Laboratory at Villanova University, stated, “90% of young males play video games. Finding that a young man who committed a violent crime also played a popular video game, such as Call of Duty, Halo, or Grand Theft Auto, is as pointless as pointing out that the criminal also wore socks.” [ 84 ] Further, gun violence is less prevalent in countries with high video game use. A study of the countries representing the 10 largest video game markets internationally found no correlation between playing video games and gun-related killings. Even though US gun violence is high, the nine other countries with the highest video game usage have some of the lowest violent crime rates (and eight of those countries spend more per capita on video games than the United States). [ 97 ] Read More

Con 4 As sales of violent video games have significantly increased, violent juvenile crime rates have significantly decreased. In 2019, juvenile arrests for violent crimes were at an all-time low, a decline of 50% since 2006. Meanwhile, video game sales set a record in Mar. 2020, with Americans spending $5.6 billion on video game hardware, accessories, and assorted content. Both statistics continue a years-long trend. [ 143 ] [ 144 ] Total U.S. sales of video game hardware and software increased 204% from 1994 to 2014, reaching $13.1 billion in 2014, while violent crimes decreased 37% and murders by juveniles acting alone fell 76% in that same period. [ 82 ] [ 83 ] [ 133 ] [ 134 ] [ 135 ] The number of high school students who had been in at least one physical fight decreased from 43% in 1991 to 25% in 2013, and student reports of criminal victimization at school dropped by more than half from 1995 to 2011. [ 106 ] [ 107 ] A peer-reviewed study found that: “Monthly sales of video games were related to concurrent decreases in aggravated assaults.” [ 84 ] Read More

Con 5 Studies have shown that violent video games can have a positive effect on kindness, civic engagement, and prosocial behaviors. Research shows that playing violent video games can induce a feeling of guilt that leads to increased prosocial behavior (positive actions that benefit others) in the real world. [ 104 ] A study published in Computers in Human Behavior discovered that youths exposed to violence in action games displayed more prosocial behavior and civic engagement, “possibly due to the team-oriented multiplayer options in many of these games.” [ 103 ] Read More

Con 6 Many risk factors are associated with youth violence, but video games are not among them. The U.S. Surgeon General’s list of risk factors for youth violence included abusive parents, poverty, neglect, neighborhood crime, being male, substance use, and mental health problems, but not video games. [ 118 ] A peer-reviewed study even found a “real and significant” effect of hot weather on homicides and aggravated assaults, showing that heat is a risk factor for violence. [ 124 ] Read More

Con 7 Violent video game players know the difference between virtual violence in the context of a game and appropriate behavior in the real world. By age seven, children can distinguish fantasy from reality, and can tell the difference between video game violence and real-world violence. [ 99 ] [ 100 ] Video game players understand they are playing a game. Kids see fantasy violence all the time, from Harry Potter and the Minions to Bugs Bunny and Tom and Jerry. Their ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality prevents them from emulating video game violence in real life. [ 9 ] Exposure to fantasy is important for kids. Fisher-Price toy company stated: “Pretending is more than play: it’s a major part of a child’s development. Fantasy not only develops creative thinking, it’s also a way for children to deal with situations and problems that concern them.” [108] Read More

Con 8 Violent video games provide opportunities for children to explore consequences of violent actions, develop their moral compasses and release their stress and anger (catharsis) in the game, leading to less real world aggression. Violent games allow youth to experiment with moral issues such as war, violence, and death without real world consequences. A researcher at the Harvard Medical School Center for Mental Health and Media wrote about her research: “One unexpected theme that came up multiple times in our focus groups was a feeling among boys that violent games can teach moral lessons… Many war-themed video games allow or require players to take the roles of soldiers from different sides of a conflict, perhaps making players more aware of the costs of war.” [ 2 ] [ 38 ] A peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health found that children, especially boys, play video games as a means of managing their emotions: “61.9% of boys played to ‘help me relax,’ 47.8% because ‘it helps me forget my problems,’ and 45.4% because ‘it helps me get my anger out.” [ 37 ] Researchers point to the cathartic effect of video games as a possible reason for why higher game sales have been associated with lower crime rates. [ 84 ] A peer-reviewed study in the Journal of Adolescent Research concluded that “Boys use games to experience fantasies of power and fame, to explore and master what they perceive as exciting and realistic environments (but distinct from real life), to work through angry feelings or relieve stress, and as social tools.” The games serve as a substitute for rough-and-tumble play. [ 36 ] Read More

Con 9 Studies claiming a causal link between video game violence and real life violence are flawed. Many studies failed to control for factors that contribute to children becoming violent, such as family history and mental health, plus most studies do not follow children over long periods of time. [ 10 ] [ 95 ] Video game experiments often have people playing a game for as little as ten minutes, which is not representative of how games are played in real life. In many laboratory studies, especially those involving children, researchers must use artificial measures of violence and aggression that do not translate to real-world violence and aggression, such as whether someone would force another person eat hot sauce or listen to unpleasant noises. [ 84 ] [ 94 ] According to Christopher J. Ferguson, a psychology professor at Stetson University, “matching video game conditions more carefully in experimental studies with how they are played in real life makes VVG’s [violent video games] effects on aggression essentially vanish.” [ 95 ] [ 96 ] Read More

| Did You Know? | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Video game sales set a record in Mar. 2020, with Americans spending $5.6 billion on hardware, accessories, and content, a continuation of a years-long upward trend. [ ] |

| 2. | The global video game industry was worth contributing $159.3 billion in 2020, a 9.3% increase of 9.3% from 2019. [ ] |

| 3. | Around 73% of American kids age 2-17 played video games in 2019, a 6% increase over 2018 and a continuation of a years-long upward trend. [ ] |

| 4. | An Aug. 2015 report from the American Psychological Association determined that playing violent video games is linked to increased aggression, but it did not find sufficient evidence of a link between the games and increased violence. [ ] |

| 5. | Video games accounted for 17% of kids’ entertainment time and 11% of their entertainment spending in 2019. [ ] |

| People who view this page may also like: |

|---|

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

Our Latest Updates (archived after 30 days)

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Video Games – Pros & Cons

- Pro & Con Quotes

- History of Video Games

- Did You Know?

- Entertainment Software Rating Board Categories

Cite This Page

- Artificial Intelligence

- Private Prisons

- Space Colonization

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

The evidence that video game violence leads to real-world aggression

A 2018 meta-analysis found that there is a small increase in real-world physical aggression among adolescents and pre-teens who play violent video games. Led by Jay Hull, a social psychologist at Dartmouth College, the study team pooled data from 24 previous studies in an attempt to avoid some of the problems that have made the question of a connection between gaming and aggression controversial.

Many previous studies, according to a story in Scientific American, have been criticized by “a small but vocal cadre of researchers [who] have argued much of the work implicating video games has serious flaws in that, among other things, it measures the frequency of aggressive thoughts or language rather than physically aggressive behaviors like hitting or pushing, which have more real-world relevance.”

Hull and team limited their analysis to studies that “measured the relationship between violent video game use and overt physical aggression,” according to the Scientific American article .

The Dartmouth analysis drew on 24 studies involving more than 17,000 participants and found that “playing violent video games is associated with increases in physical aggression over time in children and teens,” according to a Dartmouth press release describing the study , which was published Oct. 1, 2018, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

The studies the Dartmouth team analyzed “tracked physical aggression among users of violent video games for periods ranging from three months to four years. Examples of physical aggression included incidents such as hitting someone or being sent to the school principal’s office for fighting, and were based on reports from children, parents, teachers, and peers,” according to the press release.

The study was almost immediately called in to question. In an editorial in Psychology Today , a pair of professors claim the results of the meta-analysis are not statistically significant. Hull and team wrote in the PNAS paper that, while small, the results are indeed significant. The Psychology Today editorial makes an appeal to a 2017 statement by the American Psychological Association’s media psychology and technology division “cautioning policy makers and news media to stop linking violent games to serious real-world aggression as the data is just not there to support such beliefs.”

It should be noted, however, that the 2017 statement questions the connection between “serious” aggression while the APA Resolution of 2015 , based on a review of its 2005 resolution by its own experts, found that “the link between violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior is one of the most studied and best established. Since the earlier meta-analyses, this link continues to be a reliable finding and shows good multi-method consistency across various representations of both violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior.”