- Skip to Page Content

- Skip to Navigation

- Skip to Search

- Skip to Footer

- COVID-19 Health and Safety

- Admissions and Ticketing

- Temporary Hall Closures

- Accessibility

- Field Trips

- Adult Group Visits

- Guided Tours

- Transportation

- Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium

- Invisible Worlds: Immersive Experience

- The Secret World of Elephants

- Turtle Odyssey

- Worlds Beyond Earth: Space Show

- Extinct and Endangered: Insects in Peril

- Grounded by Our Roots

- Ice Cold: An Exhibition of Hip-Hop Jewelry

- Opulent Oceans

- What's in a Name?

- Children & Family Programs

- Teen Programs

- Higher Education

- Adult Programs

- Educator Programs

- Evaluation, Research, & Policy

- Master of Arts in Teaching

- Online Courses for Educators

- Urban Advantage

- Climate Week NYC

- Viruses, Vaccines, and COVID-19

- The Science of COVID-19

- OLogy: The Science Website for Kids

- News & Blogs

- Science Topics

- Margaret Mead Festival

- Origami at the Museum

- Astrophysics

- Earth and Planetary Sciences

- Herpetology

- Ichthyology

- Ornithology

- Richard Gilder Graduate School

- Hayden Planetarium

- Center for Biodiversity and Conservation

- Institute for Comparative Genomics

- Southwestern Research Station

- Research Library

- Darwin Manuscripts Project

- Microscopy and Imaging Facility

- Science Conservation

- Computational Sciences

- Staff Directory

- Scientific Publications

- Ways to Donate

- Membership FAQ

- Benefit Events

- Corporate Support

- Planned Giving

- At the Museum

- Biodiversity

- Data Visualizations

- Dinosaurs and Fossils

- Earth and Climate

- In the Field

- Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate

- Kid Science

- Research and Collections

- SciCafe / Lectures

The Scientific Process

1. define a question to investigate.

As scientists conduct their research, they make observations and collect data. The observations and data often lead them to ask why something is the way it is. Scientists pursue answers to these questions in order to continue with their research. Once scientists have a good question to investigate, they begin to think of ways to answer it.

2. Make Predictions

Based on their research and observations, scientists will often come up with a hypothesis. A hypothesis is a possible answer to a question. It is based on: their own observations, existing theories, and information they gather from other sources. Scientists use their hypothesis to make a prediction, a testable statement that describes what they think the outcome of an investigation will be.

3. Gather Data

Evidence is needed to test the prediction. There are several strategies for collecting evidence, or data. Scientists can gather their data by observing the natural world, performing an experiment in a laboratory, or by running a model. Scientists decide what strategy to use, often combining strategies. Then they plan a procedure and gather their data. They make sure the procedure can be repeated, so that other scientists can evaluate their findings.

4. Analyze the Data

Scientists organize their data in tables, graphs, or diagrams. If possible, they include relevant data from other sources. They look for patterns that show connections between important variables in the hypothesis they are testing.

Chapter 1: Scientific Inquiry

Back to chapter, the scientific method, previous video 1.2: levels of organization, next video 1.4: inductive reasoning.

The scientific method is a detailed, stepwise process for answering questions. For example, a scientist makes an observation that the slugs destroy some cabbages but not those near garlic.

Such observations lead to asking questions, "Could garlic be used to deter slugs from ruining a cabbage patch?" After formulating questions, the scientist can then develop hypotheses —potential explanations for the observations that lead to specific, testable predictions.

In this case, a hypothesis could be that garlic repels slugs, which predicts that cabbages surrounded by garlic powder will suffer less damage than the ones without it.

The hypothesis is then tested through a series of experiments designed to eliminate hypotheses.

The experimental setup involves defining variables. An independent variable is an item that is being tested, in this case, garlic addition. The dependent variable describes the measurement used to determine the outcome, such as the number of slugs on the cabbages.

In addition, the slugs must be divided into groups, experimental and control. These groups are identical, except that the experimental group is exposed to garlic powder.

After data are collected and analyzed, conclusions are made, and results are communicated to other scientists.

The scientific method is a detailed, empirical problem-solving process used by biologists and other scientists. This iterative approach involves formulating a question based on observation, developing a testable potential explanation for the observation (called a hypothesis), making and testing predictions based on the hypothesis, and using the findings to create new hypotheses and predictions.

Generally, predictions are tested using carefully-designed experiments. Based on the outcome of these experiments, the original hypothesis may need to be refined, and new hypotheses and questions can be generated. Importantly, this illustrates that the scientific method is not a stepwise recipe. Instead, it is a continuous refinement and testing of ideas based on new observations, which is the crux of scientific inquiry.

Science is mutable and continuously changes as scientists learn more about the world, physical phenomena and how organisms interact with their environment. For this reason, scientists avoid claiming to ‘prove' a specific idea. Instead, they gather evidence that either supports or refutes a given hypothesis.

Making Observations and Formulating Hypotheses

A hypothesis is preceded by an initial observation, during which information is gathered by the senses (e.g., vision, hearing) or using scientific tools and instruments. This observation leads to a question that prompts the formation of an initial hypothesis, a (testable) possible answer to the question. For example, the observation that slugs eat some cabbage plants but not cabbage plants located near garlic may prompt the question: why do slugs selectively not eat cabbage plants near garlic? One possible hypothesis, or answer to this question, is that slugs have an aversion to garlic. Based on this hypothesis, one might predict that slugs will not eat cabbage plants surrounded by a ring of garlic powder.

A hypothesis should be falsifiable, meaning that there are ways to disprove it if it is untrue. In other words, a hypothesis should be testable. Scientists often articulate and explicitly test for the opposite of the hypothesis, which is called the null hypothesis. In this case, the null hypothesis is that slugs do not have an aversion to garlic. The null hypothesis would be supported if, contrary to the prediction, slugs eat cabbage plants that are surrounded by garlic powder.

Testing a Hypothesis

When possible, scientists test hypotheses using controlled experiments that include independent and dependent variables, as well as control and experimental groups.

An independent variable is an item expected to have an effect (e.g., the garlic powder used in the slug and cabbage experiment or treatment given in a clinical trial). Dependent variables are the measurements used to determine the outcome of an experiment. In the experiment with slugs, cabbages, and garlic, the number of slugs eating cabbages is the dependent variable. This number is expected to depend on the presence or absence of garlic powder rings around the cabbage plants.

Experiments require experimental and control groups. An experimental group is treated with or exposed to the independent variable (i.e., the manipulation or treatment). For example, in the garlic aversion experiment with slugs, the experimental group is a group of cabbage plants surrounded by a garlic powder ring. A control group is subject to the same conditions as the experimental group, with the exception of the independent variable. Control groups in this experiment might include a group of cabbage plants in the same area that is surrounded by a non-garlic powder ring (to control for powder aversion) and a group that is not surrounded by any particular substance (to control for cabbage aversion). It is essential to include a control group because, without one, it is unclear whether the outcome is the result of the treatment or manipulation.

Refining a Hypothesis

If the results of an experiment support the hypothesis, further experiments may be designed and carried out to provide support for the hypothesis. The hypothesis may also be refined and made more specific. For example, additional experiments could determine whether slugs also have an aversion to other plants of the Allium genus, like onions.

If the results do not support the hypothesis, then the original hypothesis may be modified based on the new observations. It is important to rule out potential problems with the experimental design before modifying the hypothesis. For example, if slugs demonstrate an aversion to both garlic and non-garlic powder, the experiment can be carried out again using fresh garlic instead of powdered garlic. If the slugs still exhibit no aversion to garlic, then the original hypothesis can be modified.

Communication

The results of the experiments should be communicated to other scientists and the public, regardless of whether the data support the original hypothesis. This information can guide the development of new hypotheses and experimental questions.

The Scientific Method Tutorial

| | |

The Scientific Method

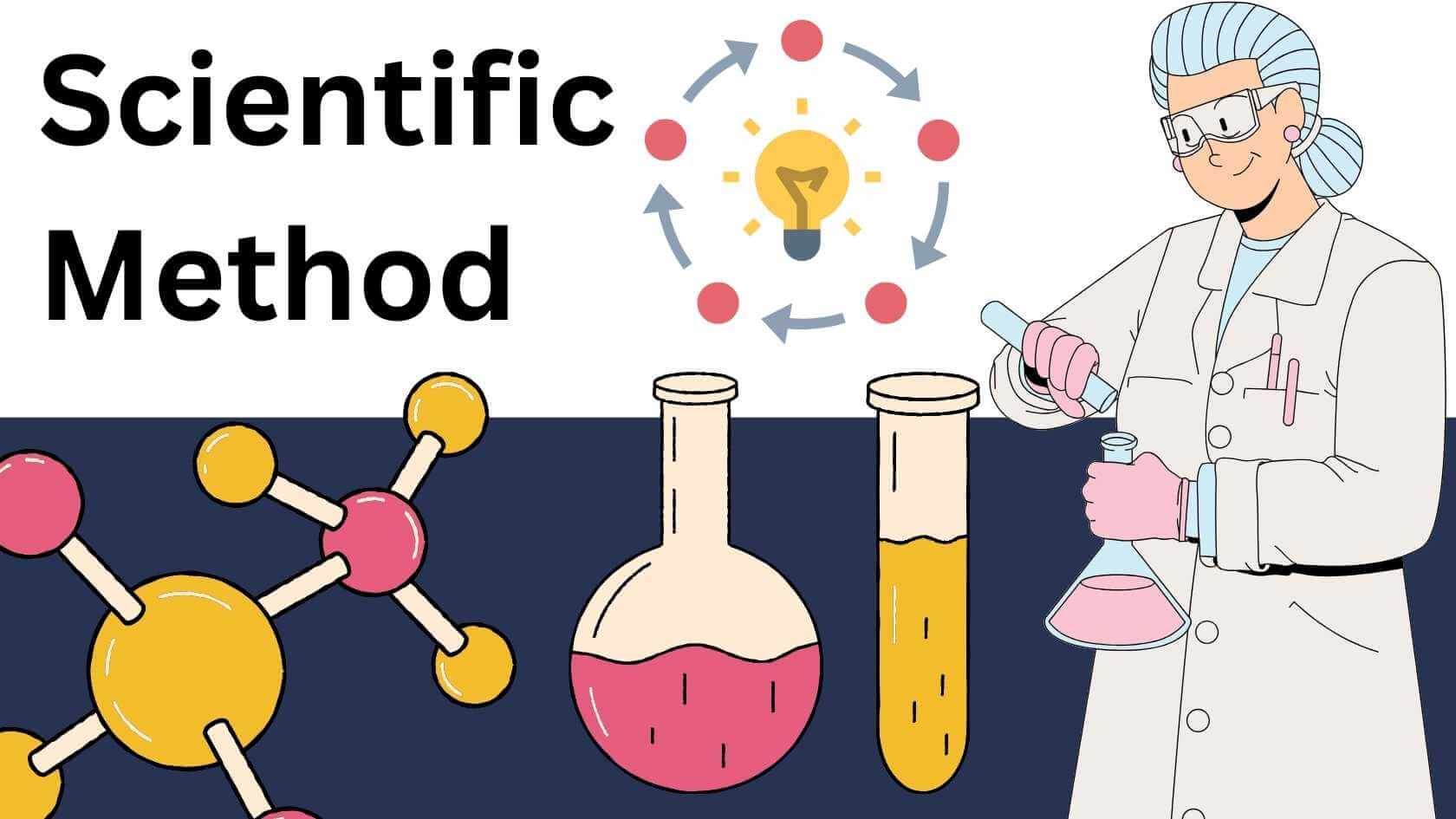

Steps in the scientific method.

There is a great deal of variation in the specific techniques scientists use explore the natural world. However, the following steps characterize the majority of scientific investigations:

Step 1: Make observations Step 2: Propose a hypothesis to explain observations Step 3: Test the hypothesis with further observations or experiments Step 4: Analyze data Step 5: State conclusions about hypothesis based on data analysis

Each of these steps is explained briefly below, and in more detail later in this section.

Step 1: Make observations

A scientific inquiry typically starts with observations. Often, simple observations will trigger a question in the researcher's mind.

Example: A biologist frequently sees monarch caterpillars feeding on milkweed plants, but rarely sees them feeding on other types of plants. She wonders if it is because the caterpillars prefer milkweed over other food choices.

Step 2: Propose a hypothesis

The researcher develops a hypothesis (singular) or hypotheses (plural) to explain these observations. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation of a phenomenon or observation(s) that can be supported or falsified by further observations or experimentation.

Example: The researcher hypothesizes that monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed compared to other common plants. (Notice how the hypothesis is a statement, not a question as in step 1.)

Step 3: Test the hypothesis

The researcher makes further observations and/or may design an experiment to test the hypothesis. An experiment is a controlled situation created by a researcher to test the validity of a hypothesis. Whether further observations or an experiment is used to test the hypothesis will depend on the nature of the question and the practicality of manipulating the factors involved.

Example: The researcher sets up an experiment in the lab in which a number of monarch caterpillars are given a choice between milkweed and a number of other common plants to feed on.

Step 4: Analyze data

The researcher summarizes and analyzes the information, or data, generated by these further observations or experiments.

Example: In her experiment, milkweed was chosen by caterpillars 9 times out of 10 over all other plant selections.

Step 5: State conclusions

The researcher interprets the results of experiments or observations and forms conclusions about the meaning of these results. These conclusions are generally expressed as probability statements about their hypothesis.

Example: She concludes that when given a choice, 90 percent of monarch caterpillars prefer to feed on milkweed over other common plants.

Often, the results of one scientific study will raise questions that may be addressed in subsequent research. For example, the above study might lead the researcher to wonder why monarchs seem to prefer to feed on milkweed, and she may plan additional experiments to explore this question. For example, perhaps the milkweed has higher nutritional value than other available plants.

Return to top of page

The Scientific Method Flowchart

The steps in the scientific method are presented visually in the following flow chart. The question raised or the results obtained at each step directly determine how the next step will proceed. Following the flow of the arrows, pass the cursor over each blue box. An explanation and example of each step will appear. As you read the example given at each step, see if you can predict what the next step will be.

Activity: Apply the Scientific Method to Everyday Life Use the steps of the scientific method described above to solve a problem in real life. Suppose you come home one evening and flick the light switch only to find that the light doesn’t turn on. What is your hypothesis? How will you test that hypothesis? Based on the result of this test, what are your conclusions? Follow your instructor's directions for submitting your response.

The above flowchart illustrates the logical sequence of conclusions and decisions in a typical scientific study. There are some important points to note about this process:

1. The steps are clearly linked.

The steps in this process are clearly linked. The hypothesis, formed as a potential explanation for the initial observations, becomes the focus of the study. The hypothesis will determine what further observations are needed or what type of experiment should be done to test its validity. The conclusions of the experiment or further observations will either be in agreement with or will contradict the hypothesis. If the results are in agreement with the hypothesis, this does not prove that the hypothesis is true! In scientific terms, it "lends support" to the hypothesis, which will be tested again and again under a variety of circumstances before researchers accept it as a fairly reliable description of reality.

2. The same steps are not followed in all types of research.

The steps described above present a generalized method followed in a many scientific investigations. These steps are not carved in stone. The question the researcher wishes to answer will influence the steps in the method and how they will be carried out. For example, astronomers do not perform many experiments as defined here. They tend to rely on observations to test theories. Biologists and chemists have the ability to change conditions in a test tube and then observe whether the outcome supports or invalidates their starting hypothesis, while astronomers are not able to change the path of Jupiter around the Sun and observe the outcome!

3. Collected observations may lead to the development of theories.

When a large number of observations and/or experimental results have been compiled, and all are consistent with a generalized description of how some element of nature operates, this description is called a theory. Theories are much broader than hypotheses and are supported by a wide range of evidence. Theories are important scientific tools. They provide a context for interpretation of new observations and also suggest experiments to test their own validity. Theories are discussed in more detail in another section.

| . . |

The Scientific Method in Detail

In the sections that follow, each step in the scientific method is described in more detail.

Step 1: Observations

Observations in science.

An observation is some thing, event, or phenomenon that is noticed or observed. Observations are listed as the first step in the scientific method because they often provide a starting point, a source of questions a researcher may ask. For example, the observation that leaves change color in the fall may lead a researcher to ask why this is so, and to propose a hypothesis to explain this phenomena. In fact, observations also will provide the key to answering the research question.

In science, observations form the foundation of all hypotheses, experiments, and theories. In an experiment, the researcher carefully plans what observations will be made and how they will be recorded. To be accepted, scientific conclusions and theories must be supported by all available observations. If new observations are made which seem to contradict an established theory, that theory will be re-examined and may be revised to explain the new facts. Observations are the nuts and bolts of science that researchers use to piece together a better understanding of nature.

Observations in science are made in a way that can be precisely communicated to (and verified by) other researchers. In many types of studies (especially in chemistry, physics, and biology), quantitative observations are used. A quantitative observation is one that is expressed and recorded as a quantity, using some standard system of measurement. Quantities such as size, volume, weight, time, distance, or a host of others may be measured in scientific studies.

Some observations that researchers need to make may be difficult or impossible to quantify. Take the example of color. Not all individuals perceive color in exactly the same way. Even apart from limiting conditions such as colorblindness, the way two people see and describe the color of a particular flower, for example, will not be the same. Color, as perceived by the human eye, is an example of a qualitative observation.

Qualitative observations note qualities associated with subjects or samples that are not readily measured. Other examples of qualitative observations might be descriptions of mating behaviors, human facial expressions, or "yes/no" type of data, where some factor is present or absent. Though the qualities of an object may be more difficult to describe or measure than any quantities associated with it, every attempt is made to minimize the effects of the subjective perceptions of the researcher in the process. Some types of studies, such as those in the social and behavioral sciences (which deal with highly variable human subjects), may rely heavily on qualitative observations.

Question: Why are observations important to science?

Limits of Observations

Because all observations rely to some degree on the senses (eyes, ears, or steady hand) of the researcher, complete objectivity is impossible. Our human perceptions are limited by the physical abilities of our sense organs and are interpreted according to our understanding of how the world works, which can be influenced by culture, experience, or education. According to science education specialist, George F. Kneller, "Surprising as it may seem, there is no fact that is not colored by our preconceptions" ("A Method of Enquiry," from Science and Its Ways of Knowing [Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1997], 15).

Observations made by a scientist are also limited by the sensitivity of whatever equipment he is using. Research findings will be limited at times by the available technology. For example, Italian physicist and philosopher Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) was reportedly the first person to observe the heavens with a telescope. Imagine how it must have felt to him to see the heavens through this amazing new instrument! It opened a window to the stars and planets and allowed new observations undreamed of before.

In the centuries since Galileo, increasingly more powerful telescopes have been devised that dwarf the power of that first device. In the past decade, we have marveled at images from deep space , courtesy of the Hubble Space Telescope, a large telescope that orbits Earth. Because of its view from outside the distorting effects of the atmosphere, the Hubble can look 50 times farther into space than the best earth-bound telescopes, and resolve details a tenth of the size (Seeds, Michael A., Horizons: Exploring the Universe , 5 th ed. [Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1998], 86-87).

Construction is underway on a new radio telescope that scientists say will be able to detect electromagnetic waves from the very edges of the universe! This joint U.S.-Mexican project may allow us to ask questions about the origins of the universe and the beginnings of time that we could never have hoped to answer before. Completion of the new telescope is expected by the end of 2001.

Although the amount of detail observed by Galileo and today's astronomers is vastly different, the stars and their relationships have not changed very much. Yet with each technological advance, the level of detail of observation has been increased, and with it, the power to answer more and more challenging questions with greater precision.

Question: What are some of the differences between a casual observation and a 'scientific observation'?

Step 2: The Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a statement created by the researcher as a potential explanation for an observation or phenomena. The hypothesis converts the researcher's original question into a statement that can be used to make predictions about what should be observed if the hypothesis is true. For example, given the hypothesis, "exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation increases the risk of skin cancer," one would predict higher rates of skin cancer among people with greater UV exposure. These predictions could be tested by comparing skin cancer rates among individuals with varying amounts of UV exposure. Note how the hypothesis itself determines what experiments or further observations should be made to test its validity. Results of tests are then compared to predictions from the hypothesis, and conclusions are stated in terms of whether or not the data supports the hypothesis. So the hypothesis serves a guide to the full process of scientific inquiry.

The Qualities of a Good Hypothesis

- A hypothesis must be testable or provide predictions that are testable. It can potentially be shown to be false by further observations or experimentation.

- A hypothesis should be specific. If it is too general it cannot be tested, or tests will have so many variables that the results will be complicated and difficult to interpret. A well-written hypothesis is so specific it actually determines how the experiment should be set up.

- A hypothesis should not include any untested assumptions if they can be avoided. The hypothesis itself may be an assumption that is being tested, but it should be phrased in a way that does not include assumptions that are not tested in the experiment.

- It is okay (and sometimes a good idea) to develop more than one hypothesis to explain a set of observations. Competing hypotheses can often be tested side-by-side in the same experiment.

Question: Why is the hypothesis important to the scientific method?

|

grow well in a lighted incubator maintained at 90 F. A culture of was accidentally left uncovered overnight on a laboratory bench where it was dark and temperatures fluctuated between 65 F and 68 F. When the technician returned in the morning, all the cells were dead. Which of the following statements is the hypothesis to explain why the cells died, based on this observation? | cells to die. | |

Step 3: Testing the Hypothesis

A hypothesis may be tested in one of two ways: by making additional observations of a natural situation, or by setting up an experiment. In either case, the hypothesis is used to make predictions, and the observations or experimental data collected are examined to determine if they are consistent or inconsistent with those predictions. Hypothesis testing, especially through experimentation, is at the core of the scientific process. It is how scientists gain a better understanding of how things work.

Testing a Hypothesis by Observation

Some hypotheses may be tested through simple observation. For example, a researcher may formulate the hypothesis that the sun always rises in the east. What might an alternative hypothesis be? If his hypothesis is correct, he would predict that the sun will rise in the east tomorrow. He can easily test such a prediction by rising before dawn and going out to observe the sunrise. If the sun rises in the west, he will have disproved the hypothesis. He will have shown that it does not hold true in every situation. However, if he observes on that morning that the sun does in fact rise in the east, he has not proven the hypothesis. He has made a single observation that is consistent with, or supports, the hypothesis. As a scientist, to confidently state that the sun will always rise in the east, he will want to make many observations, under a variety of circumstances. Note that in this instance no manipulation of circumstance is required to test the hypothesis (i.e., you aren't altering the sun in any way).

Testing a Hypothesis by Experimentation

An experiment is a controlled series of observations designed to test a specific hypothesis. In an experiment, the researcher manipulates factors related to the hypothesis in such a way that the effect of these factors on the observations (data) can be readily measured and compared. Most experiments are an attempt to define a cause-and-effect relationship between two factors or events—to explain why something happens. For example, with the hypothesis "roses planted in sunny areas bloom earlier than those grown in shady areas," the experiment would be testing a cause-and-effect relationship between sunlight and time of blooming.

A major advantage of setting up an experiment versus making observations of what is already available is that it allows the researcher to control all the factors or events related to the hypothesis, so that the true cause of an event can be more easily isolated. In all cases, the hypothesis itself will determine the way the experiment will be set up. For example, suppose my hypothesis is "the weight of an object is proportional to the amount of time it takes to fall a certain distance." How would you test this hypothesis?

The Qualities of a Good Experiment

- The experiment must be conducted on a group of subjects that are narrowly defined and have certain aspects in common. This is the group to which any conclusions must later be confined. (Examples of possible subjects: female cancer patients over age 40, E. coli bacteria, red giant stars, the nicotine molecule and its derivatives.)

- All subjects of the experiment should be (ideally) completely alike in all ways except for the factor or factors that are being tested. Factors that are compared in scientific experiments are called variables. A variable is some aspect of a subject or event that may differ over time or from one group of subjects to another. For example, if a biologist wanted to test the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, he would apply different amounts of nitrogen fertilizer to several plots of grass. The grass in each of the plots should be as alike as possible so that any difference in growth could be attributed to the effect of the nitrogen. For example, all the grass should be of the same species, planted at the same time and at the same density, receive the same amount of water and sunlight, and so on. The variable in this case would be the amount of nitrogen applied to the plants. The researcher would not compare differing amounts of nitrogen across different grass species to determine the effect of nitrogen on grass growth. What is the problem with using different species of plants to compare the effect of nitrogen on plant growth? There are different kinds of variables in an experiment. A factor that the experimenter controls, and changes intentionally to determine if it has an effect, is called an independent variable . A factor that is recorded as data in the experiment, and which is compared across different groups of subjects, is called a dependent variable . In many cases, the value of the dependent variable will be influenced by the value of an independent variable. The goal of the experiment is to determine a cause-and-effect relationship between independent and dependent variables—in this case, an effect of nitrogen on plant growth. In the nitrogen/grass experiment, (1) which factor was the independent variable? (2) Which factor was the dependent variable?

- Nearly all types of experiments require a control group and an experimental group. The control group generally is not changed in any way, but remains in a "natural state," while the experimental group is modified in some way to examine the effect of the variable which of interest to the researcher. The control group provides a standard of comparison for the experimental groups. For example, in new drug trials, some patients are given a placebo while others are given doses of the drug being tested. The placebo serves as a control by showing the effect of no drug treatment on the patients. In research terminology, the experimental groups are often referred to as treatments , since each group is treated differently. In the experimental test of the effect of nitrogen on grass growth, what is the control group? In the example of the nitrogen experiment, what is the purpose of a control group?

- In research studies a great deal of emphasis is placed on repetition. It is essential that an experiment or study include enough subjects or enough observations for the researcher to make valid conclusions. The two main reasons why repetition is important in scientific studies are (1) variation among subjects or samples and (2) measurement error.

Variation among Subjects

There is a great deal of variation in nature. In a group of experimental subjects, much of this variation may have little to do with the variables being studied, but could still affect the outcome of the experiment in unpredicted ways. For example, in an experiment designed to test the effects of alcohol dose levels on reflex time in 18- to 22-year-old males, there would be significant variation among individual responses to various doses of alcohol. Some of this variation might be due to differences in genetic make-up, to varying levels of previous alcohol use, or any number of factors unknown to the researcher.

Because what the researcher wants to discover is average dose level effects for this group, he must run the test on a number of different subjects. Suppose he performed the test on only 10 individuals. Do you think the average response calculated would be the same as the average response of all 18- to 22-year-old males? What if he tests 100 individuals, or 1,000? Do you think the average he comes up with would be the same in each case? Chances are it would not be. So which average would you predict would be most representative of all 18- to 22-year-old males?

A basic rule of statistics is, the more observations you make, the closer the average of those observations will be to the average for the whole population you are interested in. This is because factors that vary among a population tend to occur most commonly in the middle range, and least commonly at the two extremes. Take human height for example. Although you may find a man who is 7 feet tall, or one who is 4 feet tall, most men will fall somewhere between 5 and 6 feet in height. The more men we measure to determine average male height, the less effect those uncommon extreme (tall or short) individuals will tend to impact the average. Thus, one reason why repetition is so important in experiments is that it helps to assure that the conclusions made will be valid not only for the individuals tested, but also for the greater population those individuals represent.

"The use of a sample (or subset) of a population, an event, or some other aspect of nature for an experimental group that is not large enough to be representative of the whole" is called sampling error (Starr, Cecie, Biology: Concepts and Applications , 4 th ed. [Pacific Cove: Brooks/Cole, 2000], glossary). If too few samples or subjects are used in an experiment, the researcher may draw incorrect conclusions about the population those samples or subjects represent.

Use the jellybean activity below to see a simple demonstration of samping error.

Directions: There are 400 jellybeans in the jar. If you could not see the jar and you initially chose 1 green jellybean from the jar, you might assume the jar only contains green jelly beans. The jar actually contains both green and black jellybeans. Use the "pick 1, 5, or 10" buttons to create your samples. For example, use the "pick" buttons now to create samples of 2, 13, and 27 jellybeans. After you take each sample, try to predict the ratio of green to black jellybeans in the jar. How does your prediction of the ratio of green to black jellybeans change as your sample changes?

Measurement Error

The second reason why repetition is necessary in research studies has to do with measurement error. Measurement error may be the fault of the researcher, a slight difference in measuring techniques among one or more technicians, or the result of limitations or glitches in measuring equipment. Even the most careful researcher or the best state-of-the-art equipment will make some mistakes in measuring or recording data. Another way of looking at this is to say that, in any study, some measurements will be more accurate than others will. If the researcher is conscientious and the equipment is good, the majority of measurements will be highly accurate, some will be somewhat inaccurate, and a few may be considerably inaccurate. In this case, the same reasoning used above also applies here: the more measurements taken, the less effect a few inaccurate measurements will have on the overall average.

Step 4: Data Analysis

In any experiment, observations are made, and often, measurements are taken. Measurements and observations recorded in an experiment are referred to as data . The data collected must relate to the hypothesis being tested. Any differences between experimental and control groups must be expressed in some way (often quantitatively) so that the groups may be compared. Graphs and charts are often used to visualize the data and to identify patterns and relationships among the variables.

Statistics is the branch of mathematics that deals with interpretation of data. Data analysis refers to statistical methods of determining whether any differences between the control group and experimental groups are too great to be attributed to chance alone. Although a discussion of statistical methods is beyond the scope of this tutorial, the data analysis step is crucial because it provides a somewhat standardized means for interpreting data. The statistical methods of data analysis used, and the results of those analyses, are always included in the publication of scientific research. This convention limits the subjective aspects of data interpretation and allows scientists to scrutinize the working methods of their peers.

Why is data analysis an important step in the scientific method?

Step 5: Stating Conclusions

The conclusions made in a scientific experiment are particularly important. Often, the conclusion is the only part of a study that gets communicated to the general public. As such, it must be a statement of reality, based upon the results of the experiment. To assure that this is the case, the conclusions made in an experiment must (1) relate back to the hypothesis being tested, (2) be limited to the population under study, and (3) be stated as probabilities.

The hypothesis that is being tested will be compared to the data collected in the experiment. If the experimental results contradict the hypothesis, it is rejected and further testing of that hypothesis under those conditions is not necessary. However, if the hypothesis is not shown to be wrong, that does not conclusively prove that it is right! In scientific terms, the hypothesis is said to be "supported by the data." Further testing will be done to see if the hypothesis is supported under a number of trials and under different conditions.

If the hypothesis holds up to extensive testing then the temptation is to claim that it is correct. However, keep in mind that the number of experiments and observations made will only represent a subset of all the situations in which the hypothesis may potentially be tested. In other words, experimental data will only show part of the picture. There is always the possibility that a further experiment may show the hypothesis to be wrong in some situations. Also, note that the limits of current knowledge and available technologies may prevent a researcher from devising an experiment that would disprove a particular hypothesis.

The researcher must be sure to limit his or her conclusions to apply only to the subjects tested in the study. If a particular species of fish is shown to consume their young 90 percent of the time when raised in captivity, that doesn't necessarily mean that all fish will do so, or that this fish's behavior would be the same in its native habitat.

Finally, the conclusions of the experiment are generally stated as probabilities. A careful scientist would never say, "drug x kills cancer cells;" she would more likely say, "drug x was shown to destroy 85 percent of cancerous skin cells in rats in lab trials." Notice how very different these two statements are. There is a tendency in the media and in the general public to gravitate toward the first statement. This makes a terrific headline and is also easy to interpret; it is absolute. Remember though, in science conclusions must be confined to the population under study; broad generalizations should be avoided. The second statement is sound science. There is data to back it up. Later studies may reveal a more universal effect of the drug on cancerous cells, or they may not. Most researchers would be unwilling to stake their reputations on the first statement.

As a student, you should read and interpret popular press articles about research studies very carefully. From the text, can you determine how the experiment was set up and what variables were measured? Are the observations and data collected appropriate to the hypothesis being tested? Are the conclusions supported by the data? Are the conclusions worded in a scientific context (as probability statements) or are they generalized for dramatic effect? In any researched-based assignment, it is a good idea to refer to the original publication of a study (usually found in professional journals) and to interpret the facts for yourself.

|

|

Qualities of a Good Experiment

- narrowly defined subjects

- all subjects treated alike except for the factor or variable being studied

- a control group is used for comparison

- measurements related to the factors being studied are carefully recorded

- enough samples or subjects are used so that conclusions are valid for the population of interest

- conclusions made relate back to the hypothesis, are limited to the population being studied, and are stated in terms of probabilities

| by Stephen S. Carey. |

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

scientific hypothesis

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - On the scope of scientific hypotheses

- LiveScience - What is a scientific hypothesis?

- The Royal Society - Open Science - On the scope of scientific hypotheses

scientific hypothesis , an idea that proposes a tentative explanation about a phenomenon or a narrow set of phenomena observed in the natural world. The two primary features of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability and testability, which are reflected in an “If…then” statement summarizing the idea and in the ability to be supported or refuted through observation and experimentation. The notion of the scientific hypothesis as both falsifiable and testable was advanced in the mid-20th century by Austrian-born British philosopher Karl Popper .

The formulation and testing of a hypothesis is part of the scientific method , the approach scientists use when attempting to understand and test ideas about natural phenomena. The generation of a hypothesis frequently is described as a creative process and is based on existing scientific knowledge, intuition , or experience. Therefore, although scientific hypotheses commonly are described as educated guesses, they actually are more informed than a guess. In addition, scientists generally strive to develop simple hypotheses, since these are easier to test relative to hypotheses that involve many different variables and potential outcomes. Such complex hypotheses may be developed as scientific models ( see scientific modeling ).

Depending on the results of scientific evaluation, a hypothesis typically is either rejected as false or accepted as true. However, because a hypothesis inherently is falsifiable, even hypotheses supported by scientific evidence and accepted as true are susceptible to rejection later, when new evidence has become available. In some instances, rather than rejecting a hypothesis because it has been falsified by new evidence, scientists simply adapt the existing idea to accommodate the new information. In this sense a hypothesis is never incorrect but only incomplete.

The investigation of scientific hypotheses is an important component in the development of scientific theory . Hence, hypotheses differ fundamentally from theories; whereas the former is a specific tentative explanation and serves as the main tool by which scientists gather data, the latter is a broad general explanation that incorporates data from many different scientific investigations undertaken to explore hypotheses.

Countless hypotheses have been developed and tested throughout the history of science . Several examples include the idea that living organisms develop from nonliving matter, which formed the basis of spontaneous generation , a hypothesis that ultimately was disproved (first in 1668, with the experiments of Italian physician Francesco Redi , and later in 1859, with the experiments of French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur ); the concept proposed in the late 19th century that microorganisms cause certain diseases (now known as germ theory ); and the notion that oceanic crust forms along submarine mountain zones and spreads laterally away from them ( seafloor spreading hypothesis ).

What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

If...,Then...

Angela Lumsden/Getty Images

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for an observation. The definition depends on the subject.

In science, a hypothesis is part of the scientific method. It is a prediction or explanation that is tested by an experiment. Observations and experiments may disprove a scientific hypothesis, but can never entirely prove one.

In the study of logic, a hypothesis is an if-then proposition, typically written in the form, "If X , then Y ."

In common usage, a hypothesis is simply a proposed explanation or prediction, which may or may not be tested.

Writing a Hypothesis

Most scientific hypotheses are proposed in the if-then format because it's easy to design an experiment to see whether or not a cause and effect relationship exists between the independent variable and the dependent variable . The hypothesis is written as a prediction of the outcome of the experiment.

Null Hypothesis and Alternative Hypothesis

Statistically, it's easier to show there is no relationship between two variables than to support their connection. So, scientists often propose the null hypothesis . The null hypothesis assumes changing the independent variable will have no effect on the dependent variable.

In contrast, the alternative hypothesis suggests changing the independent variable will have an effect on the dependent variable. Designing an experiment to test this hypothesis can be trickier because there are many ways to state an alternative hypothesis.

For example, consider a possible relationship between getting a good night's sleep and getting good grades. The null hypothesis might be stated: "The number of hours of sleep students get is unrelated to their grades" or "There is no correlation between hours of sleep and grades."

An experiment to test this hypothesis might involve collecting data, recording average hours of sleep for each student and grades. If a student who gets eight hours of sleep generally does better than students who get four hours of sleep or 10 hours of sleep, the hypothesis might be rejected.

But the alternative hypothesis is harder to propose and test. The most general statement would be: "The amount of sleep students get affects their grades." The hypothesis might also be stated as "If you get more sleep, your grades will improve" or "Students who get nine hours of sleep have better grades than those who get more or less sleep."

In an experiment, you can collect the same data, but the statistical analysis is less likely to give you a high confidence limit.

Usually, a scientist starts out with the null hypothesis. From there, it may be possible to propose and test an alternative hypothesis, to narrow down the relationship between the variables.

Example of a Hypothesis

Examples of a hypothesis include:

- If you drop a rock and a feather, (then) they will fall at the same rate.

- Plants need sunlight in order to live. (if sunlight, then life)

- Eating sugar gives you energy. (if sugar, then energy)

- White, Jay D. Research in Public Administration . Conn., 1998.

- Schick, Theodore, and Lewis Vaughn. How to Think about Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age . McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2002.

- Scientific Method Flow Chart

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

- What Are Examples of a Hypothesis?

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Hypothesis Examples

- Scientific Variable

- Scientific Method Vocabulary Terms

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- What Is an Experimental Constant?

- What Is a Controlled Experiment?

- What Is the Difference Between a Control Variable and Control Group?

- DRY MIX Experiment Variables Acronym

- Random Error vs. Systematic Error

- The Role of a Controlled Variable in an Experiment

Microbe Notes

Scientific Method: Definition, Steps, Examples, Uses

Sir Francis Bacon, an English philosopher, developed modern scientific research and scientific methods. He is also known as “the Father of modern science.”

He was influenced by Galileo Galilei and Nicholas Copernicus’ writings throughout his study.

The scientific method is a powerful analytical or problem-solving method of learning more about the natural world.

The scientific method is a combined method, which consists of theoretical knowledge and practical experimentation by using scientific instruments, analysis and comparisons of results, and then peer reviews.

- The scientific method is a procedure that the scientists use to conduct research.

- Scientific investigators play a crucial role in following a series of steps such as asking questions, setting hypothesis to answer questions, performing multiple experiments to confirm the reliability of data/ results, data collection and interpretation, and developing conclusions based on the hypothesis.

Table of Contents

Interesting Science Videos

Steps of Scientific Method

There are seven steps of the scientific method such as:

- Make an observation

- Ask a question

- Background research/ Research the topic

- Formulate a hypothesis

- Conduct an experiment to test the hypothesis

- Data record and analysis

- Draw a conclusion

1. Make an observation

- Before asking a question, you need a proper observation to get information about some topic, which may help to identify the question.

- Proper observation in the area of investigation or about something you are interested in is required, whether you recognize it or not.

2. Ask a question

- The scientific method follows a step by asking a question. Based on what you observe, Asking questions starts with Wh- such as What, When, Who, Which, Why, How, Does or Where?

- A question helps to identify a core problem and form a hypothesis . The question should be relatable and specific as much as possible.

- Why is this thing happening?

- What is the reason behind this?

- How does this happen?

- Does it need to happen?

3. Background research/ Research the topic

- Background research on the experiment/ topic is necessary to analyze and answer the questions.

- Many scientists are employing various techniques and equipment, such as libraries and Internet research (research papers, articles, journals, etc.), that push how to investigate, design, and understand the experiment.

- In addition, you can learn from other experiences, research, or experiments, which helps you not repeat the same mistakes and be aware of doing things further.

- It helps to predict what will happen in the future. It also helps to understand the theory and background history of the experiment.

4. Formulate a hypothesis

- A Hypothesis is an idea or a guess to explain a specific occurrence, natural event, or particular experience based on prior observation.

- It is another step in the scientific method. A hypothesis allows you to make a prediction. Scientists predict what will be the outcome.

- It outlines the objectives of the experiment, the variables used, and the expected outcome of the experiment. The hypothesis must be either falsifiable or testable. It also answers the previous question.

- A hypothesis needs to be testable by gathering evidence. A hypothesis needs to be testable to perform an experiment, whether the evidence supports the hypothesis or not.

5. Conduct an experiment to test a hypothesis

- After formulating a hypothesis, you must design and conduct an experiment. Experiments are the process of investigations to prove or disprove the hypothesis.

- Two variables play a crucial role in conducting experiments to test the hypothesis.

- They are Independent variables (Can be manipulated or controlled by the person, or you can change while experimenting) and dependent variables (one you measure, which may be affected by the independent variable).

- They both are the cause and effect. The dependent variable is dependent on the independent variable.

- All the variables must be under control to ensure that they have no impact on the result.

- You can also set another type of hypothesis, such as a “null hypothesis” or “no difference” hypothesis.

There is no difference in the intense rain and crop destruction.

6. Data Record and Analysis

- During the experiment, data needs to be recorded and collected. Data is a set of values. It should be represented quantitatively (measured in numbers) or qualitatively (an explanation of outcomes).

- After the data collection, you can interpret the data by drawing a chart or constructing a table or graph to show the result.

- After the data representation, you can analyze or interpret the data to understand the meaning of the data.

- You can compare the results with other experiments visually or in graphics form.

7. Draw a Conclusion

- Your Conclusion always showcases whether the experiments support the prediction and hypothesis or contradict.

- Scientists will analyze the experiment’s results and develop a new hypothesis based on the data they collect if they discover that their experiment did not support their hypothesis or that their prediction is not supported.

- While we conclude the experiment, all the collected results will be analyzed, which helps to interpret the hypothesis.

- Did your experiments support or reject your hypothesis?

- Does your hypothesis prove or disprove your study?

- Did your results show a strong correlation?

- Was there any way to change the thing to make a better experiment?

- Are there things that need to be studied further?

- If your hypothesis is supported, then that is fine. You can carry on.

- But If not, do not try to manipulate the result or try to change the result.

- Keep the result to its original form, or you can further repeat the experiment to get better results.

Application of Scientific Method

- It is essential in many sectors, such as social sciences, empirical sciences, statistics, biology, chemistry, and physics. It can be used in the laboratory.

- Scientific methods lead to discoveries, innovations, and improvements in various disciplines.

- The scientific method can be used to solve problems, explain the phenomena of the study, and find and test solutions.

- Scientific methods guarantee that the findings are based on evidence, making the study reliable and replicable and allowing research to occur objectively and systematically.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, March 14). Scientific method | Definition, Steps, & Application. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-method

- Biology Dictionary. (2020, November 6). Scientific method. Retrieved from https://biologydictionary.net/scientific-method/

- Bailey, R. (2019, August 21). Scientific method. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/scientific-method-p2-373335

- Buddies, S., & Buddies, S. (2023, August 17). Writing a Science Fair Project research plan. Retrieved from https://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/science-fair/writing-a-science-fair-project-research-plan

- Buddies, S., & Buddies, S. (2024, January 25). Steps of the scientific method. Retrieved from https://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/science-fair/steps-of-the-scientific-method

- Helmenstine, A. (2023, January 1). Steps of the scientific method. Retrieved from https://sciencenotes.org/steps-scientific-method/

- Cartwright, M., & Greer, R. (2023). Scientific method. World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Scientific_Method/

- https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/ID/ID-507-w.pdf

- GeeksforGeeks. (2024, April 18). Applications of scientific methods. Retrieved from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/applications-of-scientific-methods/

About Author

Prativa Shrestha

1 thought on “Scientific Method: Definition, Steps, Examples, Uses”

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Scientific Method: Steps and Examples

In this video we'll be providing step-by-step instruction on how to conduct an experiment using the scientific method.Visit Study.com for thousands more vide...

The Scientific Method: Steps, Examples, Tips, and Exercise

The scientific method (video)

E-mail. atop [at] chop.edu. Location - People View. Roberts Center for Pediatric Research. 2716 South StreetPhiladelphia, PA19146United States. Virtual Student Offerings. Video: Understanding the Scientific Method. Published on Jul 09, 2020 · Last Updated 3 years 7 months ago. AddtoAny.

The Scientific Method: 5 Steps for Investigating Our World

Steps of the Scientific Method

Four Ways to Teach the Scientific Method

Scientific Method: Observation, Hypothesis and Experiment ...

Units of Measurement. Identify Outcomes and Make Predictions. Scientific Methods. Scientists are always working to better understand the world. They use the scientific method to help them. The scientific method includes making observations, developing hypotheses, designing experiments, collecting data, and then drawing conclusions. Key Vocabulary.

https://patreon.com/freeschool - Help support more content like this!The Scientific Method is a way to ask and answer questions about the world in a logical ...

Scientific Method Tutorial

Scientific method | Definition, Steps, & Application

Scientific method

Scientific hypothesis | Definition, Formulation, & Example

Theory vs. Hypothesis: Basics of the Scientific Method - 2024

Courses on Khan Academy are always 100% free. Start practicing—and saving your progress—now: https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/intro-to-biology/sc...

What Is a Hypothesis? (Science) - Scientific Method

With our list of scientific method examples, you can easily follow along with the six steps and understand the process you may be struggling with. ... Test Hypothesis and Collect Data: To test this hypothesis, you might find a pedestrian-friendly overpass from which you can observe the carpool lane on the freeway. For a 60-minute period during ...

Scientific Method for Kids | Learn all about the Scientific ...

There are seven steps of the scientific method such as: Make an observation. Ask a question. Background research/ Research the topic. Formulate a hypothesis. Conduct an experiment to test the hypothesis. Data record and analysis. Draw a conclusion. 1.

BrainPOP - Animated Educational Site for Kids - Science, Social Studies, English, Math, Arts & Music, Health, and Technology

Observe, hypothesize, experiment, report, and analyze as you sing and dance to this scienterrific song!Subscribe To GoNoodle for more FUN kids videos: https:...