- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2018

Teaching and learning mathematics through error analysis

- Sheryl J. Rushton 1

Fields Mathematics Education Journal volume 3 , Article number: 4 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

25 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

For decades, mathematics education pedagogy has relied most heavily on teachers, demonstrating correctly worked example exercises as models for students to follow while practicing their own exercises. In more recent years, incorrect exercises have been introduced for the purpose of student-conducted error analysis. Combining the use of correctly worked exercises with error analysis has led researchers to posit increased mathematical understanding. Combining the use of correctly worked exercises with error analysis has led researchers to posit increased mathematical understanding.

A mixed method design was used to investigate the use of error analysis in a seventh-grade mathematics unit on equations and inequalities. Quantitative data were used to establish statistical significance of the effectiveness of using error analysis and qualitative methods were used to understand participants’ experience with error analysis.

The results determined that there was no significant difference in posttest scores. However, there was a significant difference in delayed posttest scores.

In general, the teacher and students found the use of error analysis to be beneficial in the learning process.

For decades, mathematics education pedagogy has relied most heavily on teachers demonstrating correctly worked example exercises as models for students to follow while practicing their own exercises [ 3 ]. In more recent years, incorrect exercises have been introduced for the purpose of student-conducted error analysis [ 17 ]. Conducting error analysis aligns with the Standards of Mathematical Practice [ 18 , 19 ] and the Mathematics Teaching Practices [ 18 ]. Researchers posit a result of increased mathematical understanding when these practices are used with a combination of correctly and erroneously worked exercises [ 1 , 4 , 8 , 11 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 23 ].

Review of literature

Correctly worked examples consist of a problem statement with the steps taken to reach a solution along with the final result and are an effective method for the initial acquisitions of procedural skills and knowledge [ 1 , 11 , 26 ]. Cognitive load theory [ 1 , 11 , 25 ] explains the challenge of stimulating the cognitive process without overloading the student with too much essential and extraneous information that will limit the working memory and leave a restricted capacity for learning. Correctly worked examples focus the student’s attention on the correct solution procedure which helps to avoid the need to search their prior knowledge for solution methods. Correctly worked examples free the students from performance demands and allow them to concentrate on gaining new knowledge [ 1 , 11 , 16 ].

Error analysis is an instructional strategy that holds promise of helping students to retain their learning [ 16 ]. Error analysis consists of being presented a problem statement with the steps taken to reach a solution in which one or more of the steps are incorrect, often called erroneous examples [ 17 ]. Students analyze and explain the errors and then complete the exercise correctly providing reasoning for their own solution. Error analysis leads students to enact two Standards of Mathematical Practice, namely, (a) make sense of problems and persevere in solving them and (b) attend to precision [ 19 ].

Another of the Standards of Mathematical Practice suggests that students learn to construct viable arguments and comment on the reasoning of others [ 19 ]. According to Große and Renkl [ 11 ], students who attempted to establish a rationale for the steps of the solution learned more than those who did not search for an explanation. Teachers can assist in this practice by facilitating meaningful mathematical discourse [ 18 ]. “Arguments do not have to be lengthy, they simply need to be clear, specific, and contain data or reasoning to back up the thinking” [ 20 ]. Those data and reasons could be in the form of charts, diagrams, tables, drawings, examples, or word explanations.

Researchers [ 7 , 21 ] found the process of explaining and justifying solutions for both correct and erroneous examples to be more beneficial for achieving learning outcomes than explaining and justifying solutions to correctly worked examples only. They also found that explaining why an exercise is correct or incorrect fostered transfer and led to better learning outcomes than explaining correct solutions only. According to Silver et al. [ 22 ], students are able to form understanding by classifying procedures into categories of correct examples and erroneous examples. The students then test their initial categories against further correct and erroneous examples to finally generate a set of attributes that defines the concept. Exposing students to both correctly worked examples and error analysis is especially beneficial when a mathematical concept is often done incorrectly or is easily confused [ 11 ].

Große and Renkl [ 11 ] suggested in their study involving university students in Germany that since errors are inherent in human life, introducing errors in the learning process encourages students to reflect on what they know and then be able to create clearer and more complete explanations of the solutions. The presentation of “incorrect knowledge can induce cognitive conflicts which prompt the learner to build up a coherent knowledge structure” [ 11 ]. Presenting a cognitive conflict through erroneously worked exercises triggers learning episodes through reflection and explanations, which leads to deeper understanding [ 29 ]. Error analysis “can foster a deeper and more complete understanding of mathematical content, as well as of the nature of mathematics itself” [ 4 ].

Several studies have been conducted on the use of error analysis in mathematical units [ 1 , 16 , 17 ]. The study conducted for this article differed from these previous studies in mathematical content, number of teachers and students involved in the study, and their use of a computer or online component. The most impactful differences between the error analysis studies conducted in the past and this article’s study are the length of time between the posttest and the delayed posttest and the use of qualitative data to add depth to the findings. The previous studies found students who conducted error analysis work did not perform significantly different on the posttest than students who received a more traditional approach to learning mathematics. However, the students who conducted error analysis outperformed the control group in each of the studies on delayed posttests that were given 1–2 weeks after the initial posttest.

Loibl and Rummel [ 15 ] discovered that high school students became aware of their knowledge gaps in a general manner by attempting an exercise and failing. Instruction comparing the erroneous work with correctly worked exercises filled the learning gaps. Gadgil et al. [ 9 ] conducted a study in which students who compared flawed work to expertly done work were more likely to repair their own errors than students who only explained the expertly done work. This discovery was further supported by other researchers [8, 14, 24]. Each of these researchers found students ranging from elementary mathematics to university undergraduate medical school who, when given correctly worked examples and erroneous examples, learned more than students who only examined correctly worked examples. This was especially true when the erroneous examples were similar to the kinds of errors that they had committed [ 14 ]. Stark et al. [ 24 ] added that it is important for students to receive sufficient scaffolding in correctly worked examples before and alongside of the erroneous examples.

The purpose of this study was to explore whether seventh-grade mathematics students could learn better from the use of both correctly worked examples and error analysis than from the more traditional instructional approach of solving their exercises in which the students are instructed with only correctly worked examples. The study furthered previous research on the subject of learning from the use of both correctly worked examples and error analysis by also investigating the feedback from the teacher’s and students’ experiences with error analysis. The following questions were answered in this study:

What was the difference in mathematical achievement when error analysis was included in students’ lessons and assignments versus a traditional approach of learning through correct examples only?

What kind of benefits or disadvantages did the students and teacher observe when error analysis was included in students’ lessons and assignments versus a traditional approach of learning through correct examples only?

A mixed method design was used to investigate the use of error analysis in a seventh-grade mathematics unit on equations and inequalities. Quantitative data were used to establish statistical significance of the effectiveness of using error analysis and qualitative methods were used to understand participants’ experience with error analysis [ 6 , 27 ].

Participants

Two-seventh-grade mathematics classes at an International Baccalaureate (IB) school in a suburban charter school in Northern Utah made up the control and treatment groups using a convenience grouping. One class of 26 students was the control group and one class of 27 students was the treatment group.

The same teacher taught both the groups, so a comparison could be made from the teacher’s point of view of how the students learned and participated in the two different groups. At the beginning of the study, the teacher was willing to give error analysis a try in her classroom; however, she was not enthusiastic about using this strategy. She could not visualize how error analysis could work on a daily basis. By the end of the study, the teacher became very enthusiastic about using error analysis in her seventh grade mathematics classes.

The total group of participants involved 29 males and 24 females. About 92% of the participants were Caucasian and the other 8% were of varying ethnicities. Seventeen percent of the student body was on free or reduced lunch. Approximately 10% of the students had individual education plans (IEP).

A pretest and posttest were created to contain questions that would test for mathematical understanding on equations and inequalities using Glencoe Math: Your Common Core Edition CCSS [ 5 ] as a resource. The pretest was reused as the delayed posttest. Homework assignments were created for both the control group and the treatment group from the Glencoe Math: Your Common Core Edition CCSS textbook. However, the researcher rewrote two to three of the homework exercises as erroneous examples for the treatment group to find the error and fix the exercise with justifications (see Figs. 1 , 2 ). Students from both groups used an Assignment Time Log to track the amount of time which they spent on their homework assignments.

Example of the rewritten homework exercises as equation erroneous examples

Example of the rewritten homework exercises as inequality erroneous examples

Both the control and the treatment groups were given the same pretest for an equations and inequality unit. The teacher taught both the control and treatment groups the information for the new concepts in the same manner. The majority of the instruction was done using the direct instruction strategy. The students in both groups were allowed to work collaboratively in pairs or small groups to complete the assignments after instruction had been given. During the time she allotted for answering questions from the previous assignment, she would only show the control group the exercises worked correctly. However, for the treatment group, the teacher would write errors which she found in the students’ work on the board. She would then either pair up the students or create small groups and have the student discuss what errors they noticed and how they would fix them. Often, the teacher brought the class together as a whole to discuss what they discovered and how they could learn from it.

The treatment group was given a homework assignment with the same exercises as the control group, but including the erroneous examples. Students in both the control and treatment groups were given the Assignment Time Log to keep a record of how much time was spent completing each homework assignment.

At the end of each week, both groups took the same quiz. The quizzes for the control group received a grade, and the quiz was returned without any further attention. If a student asked how to do an exercise, the teacher only showed the correct example. The teacher graded the quizzes for the treatment group using the strategy found in the Teaching Channel’s video “Highlighting Mistakes: A Grading Strategy” [ 2 ]. She marked the quizzes by highlighting the mistakes; no score was given. The students were allowed time in class or at home to make corrections with justifications.

The same posttest was administered to both groups at the conclusion of the equation and inequality chapter, and a delayed posttest was administered 6 weeks later. The delayed posttest also asked the students in the treatment group to respond to an open-ended request to “Please provide some feedback on your experience”. The test scores were analyzed for significant differences using independent samples t tests. The responses to the open-ended request were coded and analyzed for similarities and differences, and then, used to determine the students’ perceptions of the benefits or disadvantages of using error analysis in their learning.

At the conclusion of gathering data from the assessments, the researcher interviewed the teacher to determine the differences which the teacher observed in the preparation of the lessons and students’ participation in the lessons [ 6 ]. The interview with the teacher contained a variety of open-ended questions. These are the questions asked during the interview: (a) what is your opinion of using error analysis in your classroom at the conclusion of the study versus before the study began? (b) describe a typical classroom discussion in both the control group class and the treatment group class, (c) talk about the amount of time you spent grading, preparing, and teaching both groups, and (d) describe the benefits or disadvantages of using error analysis on a daily basis compared to not using error analysis in the classroom. The responses from the teacher were entered into a computer, coded, and analyzed for thematic content [ 6 , 27 ]. The themes that emerged from coding the teacher’s responses were used to determine the kind of benefits or disadvantages observed when error analysis was included in students’ lessons and assignments versus a traditional approach of learning through correct examples only from the teacher’s point of view.

Findings and discussion

Mathematical achievement.

Preliminary analyses were carried out to evaluate assumptions for the t test. Those assumptions include: (a) the independence, (b) normality tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and (c) homogeneity of variance tested using the Levene Statistic. All assumptions were met.

The Levene Statistic for the pretest scores ( p > 0.05) indicated that there was not a significant difference in the groups. Independent samples t tests were conducted to determine the effect error analysis had on student achievement determined by the difference in the means of the pretest and posttest and of the pretest and delayed posttest. There was no significant difference in the scores from the posttest for the control group ( M = 8.23, SD = 5.67) and the treatment group ( M = 9.56, SD = 5.24); t (51) = 0.88, p = 0.381. However, there was a significant difference in the scores from the delayed posttest for the control group ( M = 5.96, SD = 4.90) and the treatment group ( M = 9.41, SD = 4.77); t (51) = 2.60, p = 0.012. These results suggest that students can initially learn mathematical concepts through a variety of methods. Nevertheless, the retention of the mathematical knowledge is significantly increased when error analysis is added to the students’ lessons, assignments, and quizzes. It is interesting to note that the difference between the means from the pretest to the posttest was higher in the treatment group ( M = 9.56) versus the control group ( M = 8.23), implying that even though there was not a significant difference in the means, the treatment group did show a greater improvement.

The Assignment Time Log was completed by only 19% of the students in the treatment group and 38% of the students in the control group. By having such a small percentage of each group participate in tracking the time spent completing homework assignment, the results from the t test analysis cannot be used in any generalization. However, the results from the analysis were interesting. The mean time spent doing the assignments for each group was calculated and analyzed using an independent samples t test. There was no significant difference in the amount of time students which spent on their homework for the control group ( M = 168.30, SD = 77.41) and the treatment group ( M = 165.80, SD = 26.53); t (13) = 0.07, p = 0.946. These results suggest that the amount of time that students spent on their homework was close to the same whether they had to do error analyses (find the errors, fix them, and justify the steps taken) or solve each exercise in a traditional manner of following correctly worked examples. Although the students did not spend a significantly different amount of time outside of class doing homework, the treatment group did spend more time during class working on quiz corrections and discussing error which could attribute to the retention of knowledge.

Feedback from participants

All students participating in the current study submitted a signed informed consent form. Students process mathematical procedures better when they are aware of their own errors and knowledge gaps [ 15 ]. The theoretical model of using errors that students make themselves and errors that are likely due to the typical knowledge gaps can also be found in works by other researchers such as Kawasaki [ 14 ] and VanLehn [ 29 ]. Highlighting errors in the students’ own work and in typical errors made by others allowed the participants in the treatment group the opportunity to experience this theoretical model. From their experiences, the participants were able to give feedback to help the researcher delve deeper into what the thoughts were of the use of error analysis in their mathematics classes than any other study provided [ 1 , 4 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 29 ]. Overall, the teacher and students found the use of error analysis in the equations and inequalities unit to be beneficial. The teacher pointed out that the discussions in class were deeper in the treatment group’s class. When she tried to facilitate meaningful mathematical discourse [ 18 ] in the control group class, the students were unable to get to the same level of critical thinking as the treatment group discussions. In the open-ended question at the conclusion of the delayed posttest (“Please provide some feedback on your experience.”), the majority (86%) of the participants from the treatment group indicated that the use of erroneous examples integrated into their lessons was beneficial in helping them recognize their own mistakes and understanding how to correct those mistakes. One student reported, “I realized I was doing the same mistakes and now knew how to fix it”. Several (67%) of the students indicated learning through error analysis made the learning process easier for them. A student commented that “When I figure out the mistake then I understand the concept better, and how to do it, and how not to do it”.

When students find and correct the errors in exercises, while justifying themselves, they are being encouraged to learn to construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others [ 19 ]. This study found that explaining why an exercise is correct or incorrect fostered transfer and led to better learning outcomes than explaining correct solutions only. However, some of the higher level students struggled with the explanation component. According to the teacher, many of these higher level students who typically do very well on the homework and quizzes scored lower on the unit quizzes and tests than the students expected due to the requirement of explaining the work. In the past, these students had not been justifying their thinking and always got correct answers. Therefore, providing reasons for erroneous examples and justifying their own process were difficult for them.

Often teachers are resistant to the idea of using error analysis in their classroom. Some feel creating erroneous examples and highlighting errors for students to analyze is too time-consuming [ 28 ]. The teacher in this study taught both the control and treatment groups, which allowed her the perspective to compare both methods. She stated, “Grading took about the same amount of time whether I gave a score or just highlighted the mistakes”. She noticed that having the students work on their errors from the quizzes and having them find the errors in the assignments and on the board during class time ultimately meant less work for her and more work for the students.

Another reason behind the reluctance to use error analysis is the fact that teachers are uncertain about exposing errors to their students. They are fearful that the discussion of errors could lead their students to make those same errors and obtain incorrect solutions [ 28 ]. Yet, most of the students’ feedback stated the discussions in class and the error analyses on the assignments and quizzes helped them in working homework exercises correctly. Specifically, they said figuring out what went wrong in the exercise helped them solve that and other exercises. One student said that error analysis helped them “do better in math on the test, and I actually enjoyed it”. Nevertheless, 2 of the 27 participating students in the treatment group had negative comments about learning through error analysis. One student did not feel that correcting mistakes showed them anything, and it did not reinforce the lesson. The other student stated being exposed to error analysis did, indeed, confuse them. The student kept thinking the erroneous example was a correct answer and was unsure about what they were supposed to do to solve the exercise.

When the researcher asked the teacher if there were any benefits or disadvantages to using error analysis in teaching the equations and inequalities unit, she said that she thoroughly enjoyed teaching using the error analysis method and was planning to implement it in all of her classes in the future. In fact, she found that her “hands were tied” while grading the control group quizzes and facilitating the lessons. She said, “I wanted to have the students find their errors and fix them, so we could have a discussion about what they were doing wrong”. The students also found error analysis to have more benefits than disadvantages. Other than one student whose response was eliminated for not being on topic and the two students with negative comments, the other 24 of the students in the treatment group had positive comments about their experience with error analysis. When students had the opportunity to analyze errors in worked exercises (error analysis) through the assignments and quizzes, they were able to get a deeper understanding of the content and, therefore, retained the information longer than those who only learned through correct examples.

Discussions generated in the treatment group’s classroom afforded the students the opportunity to critically reason through the work of others and to develop possible arguments on what had been done in the erroneous exercise and what approaches might be taken to successfully find a solution to the exercise. It may seem surprising that an error as simple as adding a number when it should have been subtracted could prompt a variety of questions and lead to the students suggesting possible ways to solve and check to see if the solution makes sense. In an erroneous exercise presented to the treatment group, the students were provided with the information that two of the three angles of a triangle were 35° and 45°. The task was to write and solve an equation to find the missing measure. The erroneous exercise solver had created the equation: x + 35 + 45 = 180. Next was written x + 80 = 180. The solution was x = 260°. In the discussion, the class had on this exercise, the conclusion was made that the error occurred when 80 was added to 180 to get a sum of 260. However, the discussion progressed finding different equations and steps that could have been taken to discover the missing angle measure to be 100° and why 260° was an unreasonable solution. Another approach discussed by the students was to recognize that to say the missing angle measure was 260° contradicted with the fact that one angle could not be larger than the sum of the angle measures of a triangle. Analyzing the erroneous exercises gave the students the opportunity of engaging in the activity of “explaining” and “fixing” the errors of the presented exercise as well as their own errors, an activity that fostered the students’ learning.

The students participating in both the control and treatment groups from the two-seventh-grade mathematics classes at the IB school in a suburban charter school in Northern Utah initially learned the concepts taught in the equations and inequality unit statistically just as well with both methods of teaching. The control group had the information taught to them with the use of only correctly worked examples. If they had a question about an exercise which they did wrong, the teacher would show them how to do the exercise correctly and have a discussion on the steps required to obtain the correct solutions. On their assignments and quizzes, the control group was expected to complete the work by correctly solving the equations and inequalities in the exercise, get a score on their work, and move on to the next concept. On the other hand, the students participating in the treatment group were given erroneous examples within their assignments and asked to find the errors, explain what had been done wrong, and then correctly solve the exercise with justifications for the steps they chose to use. During lessons, the teacher put erroneous examples from the students’ work on the board and generated paired, small groups, or whole group discussion of what was wrong with the exercise and the different ways to do it correctly. On the quizzes, the teacher highlighted the errors and allowed the students to explain the errors and justify the correct solution.

Both the method of teaching using error analysis and the traditional method of presenting the exercise and having the students solve it proved to be just as successful on the immediate unit summative posttest. However, the delayed posttest given 6 weeks after the posttest showed that the retention of knowledge was significantly higher for the treatment group. It is important to note that the fact that the students in the treatment group were given more time to discuss the exercises in small groups and as a whole class could have influenced the retention of mathematical knowledge just as much or more than the treatment of using error analysis. Researchers have proven academic advantages of group work for students, in large part due to the perception of students having a secure support system, which cannot be obtained when working individually [ 10 , 12 , 13 ].

The findings of this study supported the statistical findings of other researchers [ 1 , 16 , 17 ], suggesting that error analysis may aid in providing a richer learning experience that leads to a deeper understanding of equations and inequalities for long-term knowledge. The findings of this study also investigated the teacher’s and students’ perceptions of using error analysis in their teaching and learning. The students and teacher used for this study were chosen to have the same teacher for both the control and treatment groups. Using the same teacher for both groups, the researcher was able to determine the teacher’s attitude toward the use of error analysis compared to the non-use of error analysis in her instruction. The teacher’s comments during the interview implied that she no longer had an unenthusiastic and skeptical attitude toward the use of error analysis on a daily basis in her classroom. She was “excited to implement the error analysis strategy into the rest of her classes for the rest of the school year”. She observed error analysis to be an effective way to deal with common misconceptions and offer opportunities for students to reflect on their learning from their errors. The process of error analysis assisted the teacher in supporting productive struggle in learning mathematics [ 18 ] and created opportunity for students to have deep discussions about alternative ways to solve exercises. Error analysis also aided in students’ discovery of their own errors and gave them possible ways to correct those errors. Learning through the use of error analysis was enjoyable for many of the participating students.

According to the NCTM [ 18 ], effective teaching of mathematics happens when a teacher implements exercises that will engage students in solving and discussing tasks that promote mathematical reasoning and problem solving. Providing erroneous examples allowed discussion, multiple entry points, and varied solution strategies. Both the teacher and the students participating in the treatment group came to the conclusion that error analysis is a beneficial strategy to use in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Regardless of the two negative student comments about error analysis not being helpful for them, this researcher recommends the use of error analysis in teaching and learning mathematics.

The implications of the treatment of teaching students mathematics through the use of error analysis are that students’ learning could be fostered and retention of content knowledge may be longer. When a teacher is able to have their students’ practice critiquing the reasoning of others and creating viable arguments [ 19 ] by analyzing errors in mathematics, the students not only are able to meet the Standard of Mathematical Practice, but are also creating a lifelong skill of analyzing the effectiveness of “plausible arguments, distinguish correct logic or reasoning from that which is flawed, and—if there is a flaw in an argument—explain what it is” ([ 19 ], p. 7).

Limitations and future research

This study had limitations. The sample size was small to use the same teacher for both groups. Another limitation was the length of the study only encompassed one unit. Using error analysis could have been a novelty and engaged the students more than it would when the novelty wore off. Still another limitation was the study that was conducted at an International Baccalaureate (IB) school in a suburban charter school in Northern Utah, which may limit the generalization of the findings and implications to other schools with different demographics.

This study did not have a separation of conceptual and procedural questions on the assessments. For a future study, the creation of an assessment that would be able to determine if error analysis was more helpful in teaching conceptual mathematics or procedural mathematics could be beneficial to teachers as they plan their lessons. Another suggestion for future research would be to gather more data using several teachers teaching both the treatment group and the control group.

Adams, D.M., McLaren, B.M., Durkin, K., Mayer, R.E., Rittle-Johnson, B., Isotani, S., van Velsen, M.: Using erroneous examples to improve mathematics learning with a web-based tutoring system. Comput. Hum. Behav. 36 , 401–411 (2014)

Article Google Scholar

Alcala, L.: Highlighting mistakes: a grading strategy. The teaching channel. https://www.teachingchannel.org/videos/math-test-grading-tips

Atkinson, R.K., Derry, S.J., Renkl, A., Wortham, D.: Learning from examples: instructional Principles from the worked examples research. Rev. Educ. Res. 70 (2), 181–214 (2000)

Borasi, R.: Exploring mathematics through the analysis of errors. Learn. Math. 7 (3), 2–8 (1987)

Google Scholar

Carter, J.A., Cuevas, G.J., Day, R., Malloy, C., Kersaint, G., Luchin, B.M., Willard, T.: Glencoe math: your common core edition CCSS. Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, Columbus (2013)

Creswell, J.: Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2014)

Curry, L. A.: The effects of self-explanations of correct and incorrect solutions on algebra problem-solving performance. In: Proceedings of the 26th annual conference of the cognitive science society, vol. 1548. Erlbaum, Mahwah (2004)

Durkin, K., Rittle-Johnson, B.: The effectiveness of using incorrect examples to support learning about decimal magnitude. Learn. Instr. 22 (3), 206–214 (2012)

Gadgil, S., Nokes-Malach, T.J., Chi, M.T.: Effectiveness of holistic mental model confrontation in driving conceptual change. Learn. Instr. 22 (1), 47–61 (2012)

Gaudet, A.D., Ramer, L.M., Nakonechny, J., Cragg, J.J., Ramer, M.S.: Small-group learning in an upper-level university biology class enhances academic performance and student attitutdes toward group work. Public Libr. Sci. One 5 , 1–9 (2010)

Große, C.S., Renkl, A.: Finding and fixing errors in worked examples: can this foster learning outcomes? Learn. Instr. 17 (6), 612–634 (2007)

Janssen, J., Kirschner, F., Erkens, G., Kirschner, P.A., Paas, F.: Making the black box of collaborative learning transparent: combining process-oriented and cognitive load approaches. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 22 , 139–154 (2010)

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T.: An educational psychology success story: social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ. Res. 38 , 365–379 (2009)

Kawasaki, M.: Learning to solve mathematics problems: the impact of incorrect solutions in fifth grade peers’ presentations. Jpn. J. Dev. Psychol. 21 (1), 12–22 (2010)

Loibl, K., Rummel, N.: Knowing what you don’t know makes failure productive. Learn. Instr. 34 , 74–85 (2014)

McLaren, B.M., Adams, D., Durkin, K., Goguadze, G., Mayer, R.E., Rittle-Johnson, B., Van Velsen, M.: To err is human, to explain and correct is divine: a study of interactive erroneous examples with middle school math students. 21st Century learning for 21st Century skills, pp. 222–235. Springer, Berlin (2012)

Chapter Google Scholar

McLaren, B.M., Adams, D.M., Mayer, R.E.: Delayed learning effects with erroneous examples: a study of learning decimals with a web-based tutor. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 25 (4), 520–542 (2015)

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM): Principles to actions: ensuring mathematical success for all. Author, Reston (2014)

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers (NGA Center and CCSSO): Common core state standards. Authors, Washington, DC (2010)

O’Connell, S., SanGiovanni, J.: Putting the practices into action: Implementing the common core standards for mathematical practice K-8. Heinemann, Portsmouth (2013)

Siegler, R.S.: Microgenetic studies of self-explanation. Microdevelopment: transition processes in development and learning, pp. 31–58. Cambridge University Press, New York (2002)

Silver, H.F., Strong, R.W., Perini, M.J.: The strategic teacher: Selecting the right research-based strategy for every lesson. ASCD, Alexandria (2009)

Sisman, G.T., Aksu, M.: A study on sixth grade students’ misconceptions and errors in spatial measurement: length, area, and volume. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 14 (7), 1293–1319 (2015)

Stark, R., Kopp, V., Fischer, M.R.: Case-based learning with worked examples in complex domains: two experimental studies in undergraduate medical education. Learn. Instr. 21 (1), 22–33 (2011)

Sweller, J.: Cognitive load during problem solving: effects on learning. Cognitive Sci. 12 , 257–285 (1988)

Sweller, J., Cooper, G.A.: The use of worked examples as a substitute for problem solving in learning algebra. Cognit. Instr. 2 (1), 59–89 (1985)

Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C.: Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2010)

Book Google Scholar

Tsovaltzi, D., Melis, E., McLaren, B.M., Meyer, A.K., Dietrich, M., Goguadze, G.: Learning from erroneous examples: when and how do students benefit from them? Sustaining TEL: from innovation to learning and practice, pp. 357–373. Springer, Berlin (2010)

VanLehn, K.: Rule-learning events in the acquisition of a complex skill: an evaluation of CASCADE. J. Learn. Sci. 8 (1), 71–125 (1999)

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

A spreadsheet of the data will be provided as an Additional file 1 : Error analysis data.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All students participating in the current study submitted a signed informed consent form.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Weber State University, 1351 Edvalson St. MC 1304, Ogden, UT, 84408, USA

Sheryl J. Rushton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sheryl J. Rushton .

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Error analysis data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rushton, S.J. Teaching and learning mathematics through error analysis. Fields Math Educ J 3 , 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40928-018-0009-y

Download citation

Received : 07 March 2017

Accepted : 16 January 2018

Published : 30 January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40928-018-0009-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Error analysis

- Correct and erroneous examples

- Mathematics teaching practices

- Standards of mathematical practices

Error Analysis

- First Online: 17 September 2021

Cite this chapter

- Maurizio Petrelli 2

Part of the book series: Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment ((STEGE))

Chapter 10 is about errors and error propagation. It defines precision, accuracy, standard error, and confidence intervals. Then it demonstrates how to report uncertainties in binary diagrams. Finally, it shows two approaches to propagate the uncertainties: the linearized and Monte Carlo methods.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

https://www.pcg-random.org .

https://numpy.org/doc/stable/reference/random/bit_generators/ .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physics and Geology, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

Maurizio Petrelli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maurizio Petrelli .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Petrelli, M. (2021). Error Analysis. In: Introduction to Python in Earth Science Data Analysis. Springer Textbooks in Earth Sciences, Geography and Environment. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78055-5_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78055-5_10

Published : 17 September 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-78054-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-78055-5

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2023

Deep fake detection and classification using error-level analysis and deep learning

- Rimsha Rafique 1 ,

- Rahma Gantassi 2 ,

- Rashid Amin 1 , 3 ,

- Jaroslav Frnda 4 , 5 ,

- Aida Mustapha 6 &

- Asma Hassan Alshehri 7

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 7422 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

19 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Energy science and technology

- Mathematics and computing

Due to the wide availability of easy-to-access content on social media, along with the advanced tools and inexpensive computing infrastructure, has made it very easy for people to produce deep fakes that can cause to spread disinformation and hoaxes. This rapid advancement can cause panic and chaos as anyone can easily create propaganda using these technologies. Hence, a robust system to differentiate between real and fake content has become crucial in this age of social media. This paper proposes an automated method to classify deep fake images by employing Deep Learning and Machine Learning based methodologies. Traditional Machine Learning (ML) based systems employing handcrafted feature extraction fail to capture more complex patterns that are poorly understood or easily represented using simple features. These systems cannot generalize well to unseen data. Moreover, these systems are sensitive to noise or variations in the data, which can reduce their performance. Hence, these problems can limit their usefulness in real-world applications where the data constantly evolves. The proposed framework initially performs an Error Level Analysis of the image to determine if the image has been modified. This image is then supplied to Convolutional Neural Networks for deep feature extraction. The resultant feature vectors are then classified via Support Vector Machines and K-Nearest Neighbors by performing hyper-parameter optimization. The proposed method achieved the highest accuracy of 89.5% via Residual Network and K-Nearest Neighbor. The results prove the efficiency and robustness of the proposed technique; hence, it can be used to detect deep fake images and reduce the potential threat of slander and propaganda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adversarial explanations for understanding image classification decisions and improved neural network robustness

A comparative study on image-based snake identification using machine learning

Towards a universal mechanism for successful deep learning

Introduction.

In the last decade, social media content such as photographs and movies has grown exponentially online due to inexpensive devices such as smartphones, cameras, and computers. The rise in social media applications has enabled people to quickly share this content across the platforms, drastically increasing online content, and providing easy access. At the same time, we have seen enormous progress in complex yet efficient machine learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms that can be deployed for manipulating audiovisual content to disseminate misinformation and damage the reputation of people online. We now live in such times where spreading disinformation can be easily used to sway peoples’ opinions and can be used in election manipulation or defamation of any individual. Deep fake creation has evolved dramatically in recent years, and it might be used to spread disinformation worldwide, posing a serious threat soon. Deep fakes are synthesized audio and video content generated via AI algorithms. Using videos as evidence in legal disputes and criminal court cases is standard practice. The authenticity and integrity of any video submitted as evidence must be established. Especially when deep fake generation becomes more complex, this is anticipated to become a difficult task.

The following categories of deep fake videos exist: face-swap, synthesis, and manipulation of facial features. In face-swap deep fakes, a person's face is swapped with that of the source person to create a fake video to target a person for the activities they have not committed 1 , which can tarnish the reputation of the person 2 . In another type of deep fake called lip-synching, the target person’s lips are manipulated to alter the movements according to a certain audio track. The purpose of lip-syncing is to simulate the victim's attacker's voice by having someone talk in that voice. With puppet-master, deep fakes are produced by imitating the target's facial expressions, eye movements, and head movements. Using fictitious profiles, this is done to propagate false information on social media. Last but not least, deep audio fakes or voice cloning is used to manipulate an individual's voice that associates something with the speaker they haven’t said in actual 1 , 3 .

The importance of discovering the truth in the digital realm has therefore increased. Dealing with deep fakes is significantly more difficult because they are mostly utilized for harmful objectives and virtually anyone can now produce deep fakes utilizing the tools already available. Many different strategies have been put out so far to find deep fakes. Since most are also based on deep learning, a conflict between bad and good deep learning applications has developed 4 . Hence, to solve this problem, the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched a media forensics research plan to develop fake digital media detection methods 5 . Moreover, in collaboration with Microsoft, Facebook also announced an AI-based deep fake detection challenge to prevent deep fakes from being used to deceive viewers 6 .

Over the past few years, several researchers have explored Machine Learning and Deep Learning (DL) areas to detect deep fakes from audiovisual media. The ML-based algorithms use labor-intensive and erroneous manual feature extraction before the classification phase. As a result, the performance of these systems is unstable when dealing with bigger databases. However, DL algorithms automatically carry out these tasks, which have proven tremendously helpful in various applications, including deep fake detection. Convolutional neural network (CNN), one of the most prominent DL models, is frequently used due to its state-of-the-art performance that automatically extracts low-level and high-level features from the database. Hence, these methods have drawn the researcher’s interest in scientists across the globe 7 .

Despite substantial research on the subject of deep fakes detection, there is always potential for improvement in terms of efficiency and efficacy. It may be noted that the deep fake generation techniques are improving quickly, thus resulting in increasingly challenging datasets on which previous techniques may not perform effectively. The motivation behind developing automated DL based deep fake detection systems is to mitigate the potential harm caused by deep fake technology. Deep fake content can deceive and manipulate people, leading to serious consequences, such as political unrest, financial fraud, and reputational damage. The development such systems can have significant positive impacts on various industries and fields. These systems also improve the trust and reliability of media and online content. As deep fake technology becomes more sophisticated and accessible, it is important to have reliable tools to distinguish between real and fake content. Hence, developing a robust system to detect deep fakes from media has become very necessary in this age of social media. This paper is a continuation of to study provided by Rimsha et al. 8 . The paper compares the performance of CNN architectures such as AlexNet and VGG16 to detect if the image is real of has been digitally altered. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

In this study, we propose a novel deep fake detection and classification method employing DL and ML-based methods.

The proposed framework preprocesses the image by resizing it according to CNN’s input layer and then performing Error Level Analysis to find any digital manipulation on a pixel level.

The resultant ELA image is supplied to Convolutional Neural Networks, i.e., GoogLeNet, ResNet18 and SqueezeNet, for deep feature extraction.

Extensive experiments are conducted to find the optimal hyper-parameter setting by hyper-parameter tuning.

The performance of the proposed technique is evaluated on the publically available dataset for deep fake detection

Related work

The first ever deep fake was developed in 1860, when a portrait of southern leader John Calhoun was expertly altered for propaganda by swapping his head out for the US President. These manipulations are typically done by splicing, painting, and copy-moving the items inside or between two photos. The appropriate post-processing processes are then used to enhance the visual appeal, scale, and perspective coherence. These steps include scaling, rotating, and color modification 9 , 10 . A range of automated procedures for digital manipulation with improved semantic consistency are now available in addition to these conventional methods of manipulation due to developments in computer graphics and ML/DL techniques. Modifications in digital media have become relatively affordable due to widely available software for developing such content. The manipulation is in digital media is increasing at a very fast pace which requires development of such algorithms to robustly detect and analyze such content to find the difference between right and wrong 11 , 12 , 13 .

Despite being a relatively new technology, deep fake has been the topic of investigation. In recent years, there had been a considerable increase in deep fake articles towards the end of 2020. Due to the advent of ML and DL-based techniques, many researchers have developed automated algorithms to detect deep fakes from audiovisual content. These techniques have helped in finding out the real and fake content easily. Deep learning is well renowned for its ability to represent complicated and high-dimensional data 11 , 14 . Matern et al. 15 employed detected deep fakes from Face Forensics dataset using Multilayered perceptron (MLP) with an AUC of 0.85. However, the study considers facial images with open eyes only. Agarwal et al. 16 extracted features using Open Face 2 toolkit and performed classification via SVM. The system obtained 93% AUC; however, the system provides incorrect results when a person is not facing camera. The authors in Ciftci et al. 17 extracted medical signal features and performed classification via CNN with 97% accuracy. However, the system is computationally complex due to a very large feature vector. In their study, Yang et al. 18 extracted 68-D facial landmarks using DLib and classified these features via SVM. The system obtained 89% ROC. However, the system is not robust to blurred and requires a preprocessing stage. Rossle et al. 19 employed SVM + CNN for feature classification and a Co-Occurrence matrix for feature extraction. The system attained 90.29% accuracy on Face Forensics dataset. However, the system provides poor results on compressed videos. McCloskey et al. 20 developed a deep fake detector by using the dissimilarity of colors between real camera and synthesized and real image samples. The SVM classifier was trained on color based features from the input samples. However, the system may struggle on non-preprocessed and blurry images.

A Hybrid Multitask Learning Framework with a Fire Hawk Optimizer for Arabic Fake News Detection aims to address the issue of identifying fake news in the Arabic language. The study proposes a hybrid approach that leverages the power of multiple tasks to detect fake news more accurately and efficiently. The framework uses a combination of three tasks, namely sentence classification, stance detection, and relevance prediction, to determine the authenticity of the news article. The study also suggests the use of the Fire Hawk Optimizer algorithm, a nature-inspired optimization algorithm, to fine-tune the parameters of the framework. This helps to improve the accuracy of the model and achieve better performance. The Fire Hawk Optimizer is an efficient and robust algorithm that is inspired by the hunting behavior of hawks. It uses a global and local search strategy to search for the optimal solution 21 . The authors in 22 propose a Convolution Vision Transformer (CVT) architecture that differs from CNN in that it relies on a combination of attention mechanisms and convolution operations, making it more effective in recognizing patterns within images.The CVT architecture consists of multi-head self-attention and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) layers. The self-attention layer learns to focus on critical regions of the input image without the need for convolution operations, while the MLP layer helps to extract features from these regions. The extracted features are then forwarded to the output layer to make the final classification decision. However, the system is computationally expensive due to deep architecture. Guarnera et al. 23 identified deep fake images using Expectation Maximization for extracting features and SVM, KNN, LDA as classification methods. However, the system fails in recognizing compressed images. Nguyen et al. 24 proposed a CNN based architecture to detect deep fake content and obtained 83.7% accuracy on Face Forensics dataset. However, the system is unable to generalize well on unseen cases. Khalil et al. 25 employed Local Binary Patterns (LBP) for feature extraction and CNN and Capsule Network for deep fake detection. The models were trained on Deep Fake Detection Challenge-Preview dataset and tested on DFDC-Preview and Celeb- DF datasets. A deep fake approach developed by Afchar et al. 26 employed MesoInception-4 and achieved 81.3% True Positive Rate via Face Forensics dataset.

However, the system requires preprocessing before feature extraction and classification. Hence, results in a low overall performance on low-quality videos. Wang et al. 27 evaluated the performance of Residual Networks on deep fake classification. The authors employed ResNet and ResNeXt, on videos from Face forensics dataset. In another study by Stehouwer et al. 28 , the authors presented a CNN based approach for deep fake content detection that achieved 99% overall accuracy on Diverse Fake Face Dataset. However, the system is computationally expensive due to a very large size feature vector. Despite significant progress, existing DL algorithms are computationally expensive to train and require high-end GPUs or specialized hardware. This can make it difficult for researchers and organizations with limited resources to develop and deploy deep learning models. Moreover, some of the existing DL algorithms are prone to overfitting, which occurs when the model becomes too complex and learns to memorize the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns. This can result in poor performance on new, unseen data. The limitations in the current methodologies prove there is still a need to develop a robust and efficient deep fake detection and classification method using ML and DL based approaches.

Proposed methodology

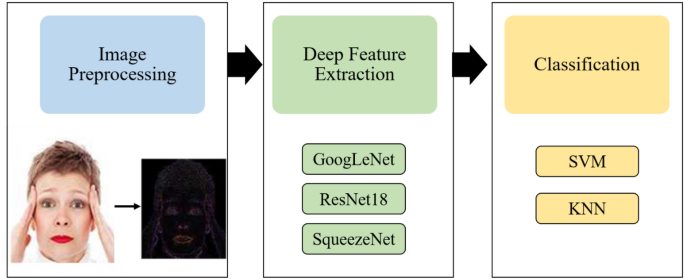

This section discusses the proposed workflow employed for deep fakes detection. The workflow diagram of our proposed framework is illustrated in Fig. 1 . The proposed system comprises of three core steps (i) image preprocessing by resizing the image according to CNN’s input layer and then generating Error Level Analysis of the image to determine pixel level alterations (ii) deep feature extraction via CNN architectures (iii) classification via SVM and KNN by performing hyper-parameter optimization.

Workflow diagram of the proposed method.

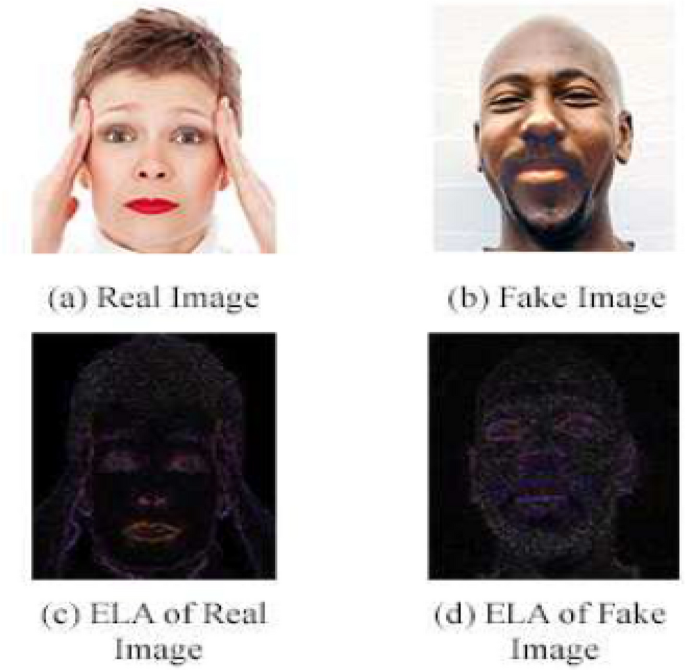

(i) Error level analysis

Error level analysis, also known as ELA, is a forensic technique used to identify image segments with varying compression levels. By measuring these compression levels, the method determines if an image has undergone digital editing. This technique works best on .JPG images as in that case, the entire image pixels should have roughly the same compression levels and may vary in case of tampering 29 , 30 .

JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group) is a technique for the lossy compression of digital images. A data compression algorithm discards (loses) some of the data to compress it. The compression level could be used as an acceptable compromise between image size and image quality. Typically, the JPEG compression ratio is 10:1. The JPEG technique uses 8 × 8 pixel image grids independently compressed. Any matrices larger than 8 × 8 are more difficult to manipulate theoretically or are not supported by the hardware, whereas any matrices smaller than 8 × 8 lack sufficient information.

Consequently, the compressed images are of poor quality. All 8 × 8 grids for unaltered images should have a same error level, allowing for the resave of the image. Given that uniformly distributed faults are throughout the image, each square should deteriorate roughly at the same pace. The altered grid in a modified image should have a higher error potential than the rest 31 .

ELA. The image is resaved with 95% error rate, and the difference between the two images is computed. This technique determines if there is any change in cells by checking whether the pixels are at their local minima 8 , 32 . This helps determine whether there is any digital tampering in the database. The ELA is computed on our database, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Result of ELA on dataset images.

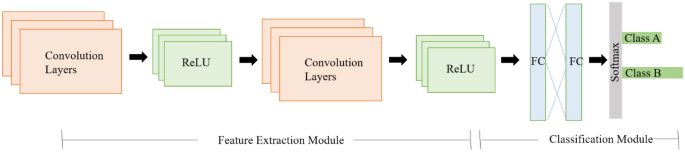

(ii) Feature extraction using convolutional neural networks

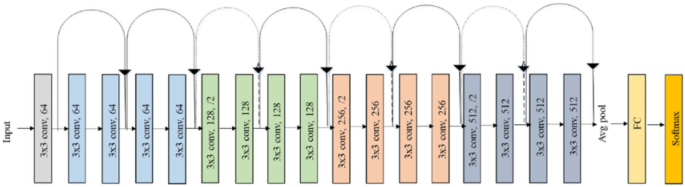

The discovery of CNN has raised its popularity among academics and motivated them to work through difficult problems that they had previously given up on. Researchers have designed several CNN designs in recent years to deal with multiple challenges in various research fields, including deep fake detection. The general architecture of CNN as shown in Fig. 3 , is usually made up of many layers stacked on top of one another. The architecture of CNN consists of a feature extraction module composed of convolutional layers to learn the features and pooling layers reduce image dimensionality. Secondly, it consists of a module comprising a fully connected (FC) layer to classify an image 33 , 34 .

General CNN architecture.

The image is input using the input layer passed down to convolution for deep feature extraction. This layer learns the visual features from the image by preserving the relationship between its pixels. This mathematical calculation is performed on an image matrix using filter/kernel of the specified size 35 . The max-pooling layer reduces the image dimensions. This process helps increase the training speed and reduce the computational load for the next stages 36 . Some networks might include normalization layers, i.e., batch normalization or dropout layer. Batch normalization layer stabilizes the network training performance by performing standardization operations on the input to mini-batches. Whereas, the dropout layer randomly drops some nodes to reduce the network complexity, increasing the network performance 37 , 38 . The last layers of the CNN include an FC layer with a softmax probability function. FC layer stores all the features extracted from the previous phases. These features are then supplied to classifiers for image classification 38 . Since CNN architectures can extract significant features without any human involvement, hence, we used pre-trained CNNs such as GoogLeNet 39 , ResNet18 31 , and SqueezeNet 40 in this study. It may be noted that developing and training a deep learning architecture from scratch is not only a time-consuming task but requires resources for computation; hence we use pre-trained CNN architectures as deep feature extractors in our proposed framework.

Microsoft introduced Residual Network (ResNet) architecture in 2015 that consists of several Convolution Layers of kernel size 3 × 3, an FC layer followed by an additional softmax layer for classification. Because they use shortcut connections that skip one or more levels, residual networks are efficient and low in computational cost 41 . Instead of anticipating that every layer stack will instantly match a specified underlying mapping, the layers fit a residual mapping. As a result of the resulting outputs being added to those of the stacked layers, these fast connections reduce loss of value during training. This functionality also aids in training the algorithm considerably faster than conventional CNNs.

Furthermore, this mapping has no parameters because it transfers the output to the next layer. The ResNet architecture outperformed other CNNs by achieving the lowest top 5% error rate in a classification job, which is 3.57% 31 , 42 . The architecture of ResNet50 is shown in Fig. 4 43 .

ResNet18 architecture 44 .

SqueezNet was developed by researchers at UC Berkeley and Stanford University that is a very lightweight and small architecture. The smaller CNN architectures are useful as they require less communication across servers in distributed training. Moreover, these CNNs also train faster and require less memory, hence are not computationally expensive compared to conventional deep CNNs. By modifying the architecture, the researchers claim that SqueezeNet can achieve AlexNet level accuracy via a smaller CNN 45 . Because an 1 × 1 filter contains 9× fewer parameters than a 3 × 3 filter, the 3 × 3 filters in these modifications have been replaced with 1 × 1 filters. Furthermore, the number of input channels is reduced to 3 × 3 filters via squeeze layers, which lowers the overall number of parameters.

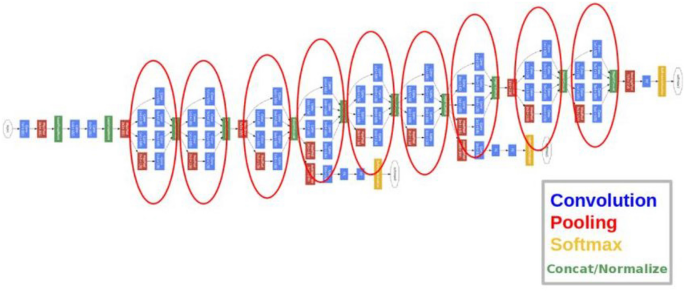

Last but not least, the downsampling is carried out very late in the network so the convolution layers’ large activation maps which is said to increase classification accuracy 40 . Developed by Google researchers, GoogLeNet is a 22-layer deep convolutional neural network that uses a 1 × 1 convolution filter size, global average pooling and an input size of 224 × 224 × 3. The architecture of GoogLeNet is shown in Fig. 5 . To increase the depth of the network architecture, the convolution filter size is reduced to 1 × 1. Additionally, the network uses global average pooling towards the end of the architecture, which inputs a 7 × 7 feature map and averages it to an 1 × 1 feature map. This helps reduce trainable parameters and enhances the system's performance. A dropout regularization of 0.7 is also used in the architecture, and the features are stored in an FC layer 39 .

GoogLeNet architecture 46 .

CNNs extract features from images hierarchically using convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. The features extracted by CNNs can be broadly classified into two categories: low-level features and high-level features. Low-level features include edges, corners, and intensity variations. CNNs can detect edges by convolving the input image with a filter that highlights the edges in the image. They can also detect corners by convolving the input image with a filter that highlights the corners. Morever, CNNs can extract color features by convolving the input image with filters that highlight specific colors. On the other hand, high-level features include texture, objects, and contextual and hierarchical features. Textures from images are detected by convolving the input image with filters that highlight different textures. The CNNs detect objects by convolving the input image with filters highlighting different shapes. Whereas, contextual features are extracted by considering the relationships between different objects in the image. Finally, the CNNs can learn to extract hierarchical features by stacking multiple convolutional layers on top of each other. The lower layers extract low-level features, while the higher layers extract high-level features.

(iii) Classification via support vector machines and k-nearest neighbors

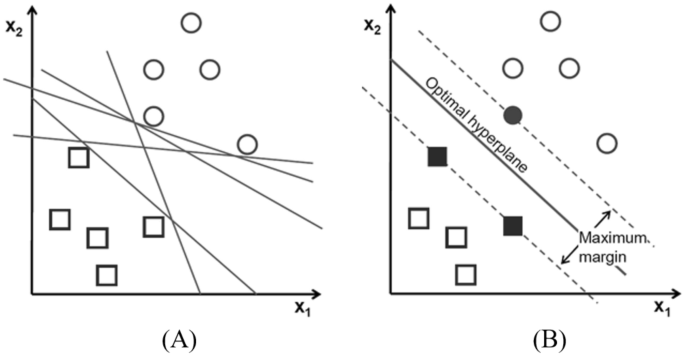

We classified the deep CNN features via SVM and KNN classifiers in this phase. KNN has gained much popularity in the research community in classification and regression tasks since it outperforms many other existing classifiers due to its simplicity and robustness. KNN calculates the distance between a test sample (k) with its neighbours and then groups the k test sample to its nearest neighbour. The KNN classifier is shown in Fig. 6

The second classifier used in this study is SVM, a widely popular classifier used frequently in many research fields because of its faster speeds and superior prediction outcomes even on a minimal dataset. The classifier finds the plane with the largest margin that separates the two classes. The wider the margin better is the classification performance of the classifier 30 , 47 . Figure 7 A depicts potential hyperplanes for a particular classification problem, whereas Fig. 7 B depicts the best hyperplane determined by SVM for that problem.

Possible SVM hyperplanes 30 .

Results and discussion

This study uses a publicly accessible dataset compiled by Yonsei University's Computational Intelligence and Photography Lab. The real and fake face database from Yonsei University's Computational Intelligence and Photography Lab is a dataset that contains images of both real and fake human faces. The dataset was designed for use in the research and development of facial recognition and verification systems, particularly those designed to detect fake or manipulated images. Each image in the dataset is labelled as either real or fake, and the dataset also includes additional information about the image, such as the age, gender, and ethnicity of the subject, as well as the manipulation technique used for fake images. Moreover, the images contain different faces, split by the eyes, nose, mouth, or entire face. The manipulated images further subdivided into three categories: easy, mid, and hard images as shown in Fig. 8 48 .

Image samples from the dataset showing real and edited images.

Evaluation metrics

Evaluation metrics are used in machine learning to measure the performance of a model. Machine learning models are designed to learn from data and make predictions or decisions based on that data. It is important to evaluate the performance of a model to understand how well it is performing and to make necessary improvements. One of the most commonly used techniques is a confusion matrix, a table to evaluate the performance of a classification model by comparing the actual and predicted classes for a set of test data. It is a matrix of four values: true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN). The proposed framework is evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score. Even though accuracy is a widely used metric, but is suitable in the case of a balanced dataset; hence, we also evaluated our proposed methods using F1-Score that combines both recall and precision into a single metric. All the evaluation metrics that we used to assess our models are calculated from Eq. ( 1 ) to Eq. ( 4 ).

Proposed method results

The escalating problems with deep fakes have made researchers more interested in media forensics in recent years. Deep fake technology has various applications in the media sector, including lip sync, face swapping, and de-aging humans. Although advances in DL and deep fake technology have various beneficial applications in business, entertainment, and the film industry, they can serve harmful goals and contribute to people's inability to believe what's true 49 , 50 . Hence, finding the difference between real and fake has become vital in this age of social media. Finding deep fake content via the human eye has become more difficult due to progress in deep fake creation technologies. Hence, a robust system must be developed to classify these fake media without human intervention accurately.

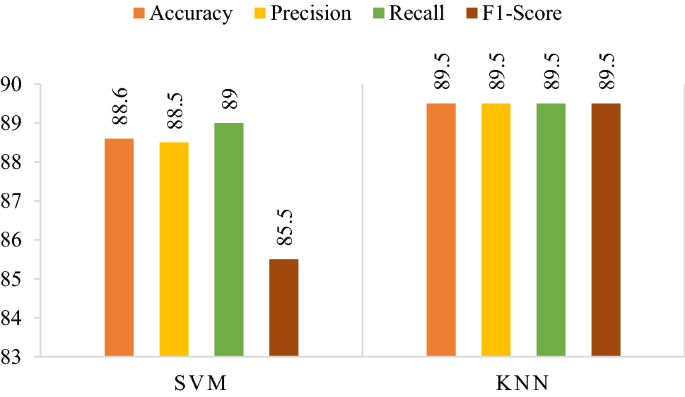

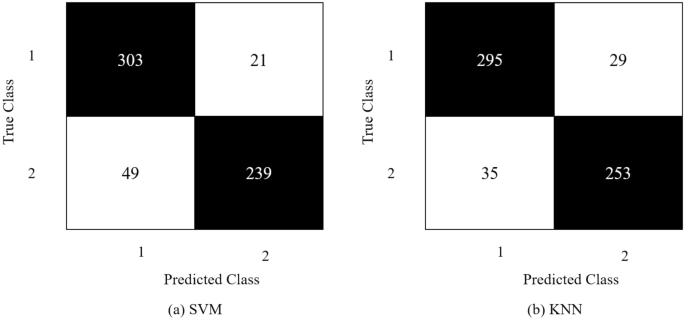

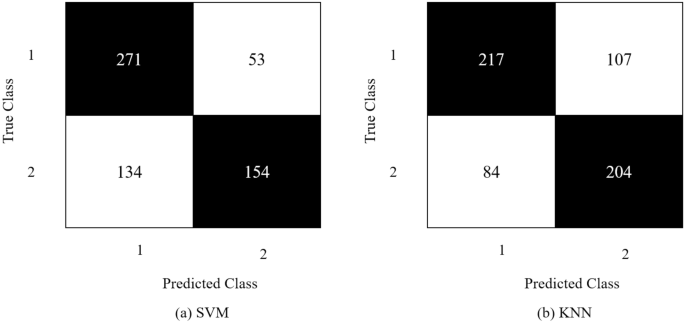

In this study, we propose a novel and robust architecture to detect and classify deep fake images using ML and DL-based techniques. The proposed framework employs a preprocessing approach to find ELA. ELA helps find if any portion of the image has been altered by analyzing the image on a pixel level. These images are then supplied to deep CNN architectures (SqueezeNet, ResNet18 & GoogLeNet) to extract deep features. The deep features are then classified via SVM and KNN. The results obtained from ResNet’s confusion matrix and ML classifiers is shown in Fig. 9 . The feature vector achieved highest accuracy of 89.5% via KNN. We tested our various hyper-parameters for both classifiers before reaching the conclusion. The proposed method achieved 89.5% accuracy via KNN on Correlation as a distance metric and total 881 neighbors. SVM achieved 88.6% accuracy on Gaussian Kernel with a 2.3 scale.

Results obtained from ResNet18's confusion matrix.

Hyperparameter optimization is the process of selecting the best set of hyperparameters for automated algorithms. Optimization is crucial for models because the model's performance depends on the choice of hyperparameters. We optimized parameters such as kernel functions, scale, no. of neighbors, distance metrics, etc., for KNN and SVM. The results obtained from the best parametric settings for different feature vectors are highlighted in bold text and shown in Table 1 . Confusion matrices of both (a) SVM and (b) KNN are illustrated in Fig. 10 .

ResNet18's confusion matrix via ( a ) SVM, ( b ) KNN.

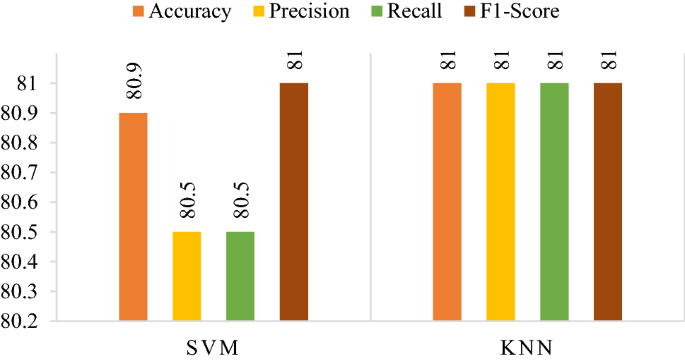

Moreover, the feature vector obtained from GoogLeNet’s obtained the highest accuracy of 81% via KNN on Chebyshev as a distance metric with a total number of 154 neighbours. The SVM classified the feature vector with 80.9% accuracy on Gaussian kernel with a 0.41 kernel scale. The tested and optimal metrics (highlighted in bold) are mentioned in Table 2 . Detailed results in other evaluation metrics are mentioned in Fig. 11 , whereas Fig. 12 shows its confusion matrices.

GoogLeNet’s results in terms of ACC, PRE, REC and F1-Score.

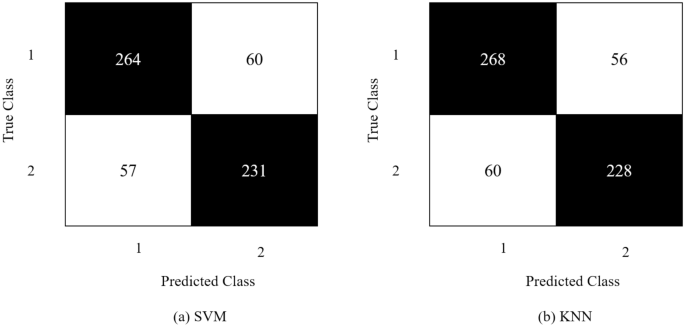

Confusion matrix obtained from GoogLeNet.

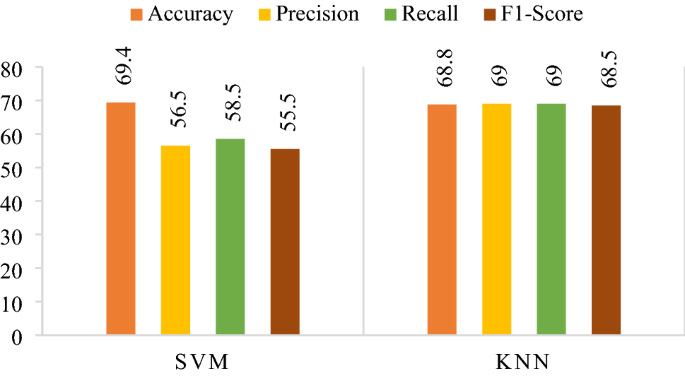

SVM and KNN classified the feature vector from SqueezeNet via 69.4% and 68.8%, respectively. The classifiers were evaluated on different parameters, as mentioned in Table 3 and achieved maximum performance on the parameters highlighted in bold text. The results in accuracy, precision, recall and f1-score are mentioned in Fig. 13 . The confusion matrix is shown in Fig. 14 .

Results obtained from SqueezeNet's confusion matrices.

Confusion matrix obtained from SqueezeNet.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

This paper proposes a novel architecture to detect and classify deep fake images via DL and ML-based techniques. The proposed framework initially preprocesses the image to generate ELA, which helps determine if the image has been digitally manipulated. The resultant ELA image is then fed to CNN architectures such as GoogLeNet, ResNet18 and ShuffleNet for deep feature extraction. The classification is then performed via SVM and KNN. The proposed method achieved highest accuracy of 89.5% via ResNet18 and KNN. Residual Networks are very efficient and lightweight and perform much better than many other traditional classifiers due to their robust feature extraction and classification techniques. The detailed comparison is shown in Table 4 . Mittal et al. 51 employed Alex Net for deepfake detection. However, the study resulted in a very poor performance. Chandani et al. 50 used a residual network framework to detect deep fake images. Similary, MLP and Meso Inception 4 by Matern et al. 15 and Afchar et al. 26 obtained more than 80% accuracy respectively. Despite being a deep CNN, Residual Networks perform much faster due to their shortcut connections which also aids in boosting the system’s performance. Hence, the proposed method performed much better on the features extracted from ResNet18.

Deep faking is a new technique widely deployed to spread disinformation and hoaxes amongst the people. Even while not all deep fake contents are malevolent, they need to be found because some threaten the world. The main goal of this research was to discover a trustworthy method for identifying deep fake images. Many researchers have been working tirelessly to detect deep fake content using a variety of approaches. However, the importance of this study lies in its use of DL and ML based methods to obtain good results. This study presents a novel framework to detect and classify deep fake images more accurately than many existing systems. The proposed method employs ELA to preprocess images and detect manipulation on a pixel level. The ELA generated images are then supplied to CNNs for feature extraction. These deep features are finally classified using SVM and KNN. The proposed technique achieved highest accuracy of 89.5% via ResNet18’s feature vector & SVM classifier. The results prove the robustness of the proposed method; hence, the system can detect deep fake images in real time. However, the proposed method is developed using image based data. In the future, we will investigate several other CNN architectures on video-based deep fake datasets. We also aim to acquire real life deep fake dataset from the people in our community and use ML and DL techniques to distinguish between deep fake images and regular images to make it more useful and robust. It is worth mentioning that the ground-breaking work will have a significant influence on our society. Using this technology, fake victims can rapidly assess whether the images are real or fake. People will continue to be cautious since our work will enable them to recognize the deep fake image.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Boylan, J. F. Will Deep-Fake Technology Destroy Democracy (The New York Times, 2018).

Google Scholar

Harwell, D. Scarlett Johansson on fake AI-generated sex videos:‘Nothing can stop someone from cutting and pasting my image’. J. Washigton Post 31 , 12 (2018).

Masood, M. et al. Deepfakes generation and detection: State-of-the-art, open challenges, countermeasures, and way forward. Appl. Intell. 53 , 1–53 (2022).

Amin, R., Al Ghamdi, M. A., Almotiri, S. H. & Alruily, M. Healthcare techniques through deep learning: Issues, challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 9 , 98523–98541 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Turek, M.J. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency . https://www.darpa.mil/program/media-forensics . Media Forensics (MediFor). Vol. 10 (2019).

Schroepfer, M. J. F. Creating a data set and a challenge for deepfakes. Artif. Intell. 5 , 263 (2019).

Kibriya, H. et al. A Novel and Effective Brain Tumor Classification Model Using Deep Feature Fusion and Famous Machine Learning Classifiers . Vol. 2022 (2022).

Rafique, R., Nawaz, M., Kibriya, H. & Masood, M. DeepFake detection using error level analysis and deep learning. in 2021 4th International Conference on Computing & Information Sciences (ICCIS) . 1–4 (IEEE, 2021).

Güera, D. & Delp, E.J. Deepfake video detection using recurrent neural networks. in 2018 15th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS) . 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Aleem, S. et al. Machine learning algorithms for depression: Diagnosis, insights, and research directions. Electronics 11 (7), 1111 (2022).

Pavan Kumar, M. & Jayagopal, P. Generative adversarial networks: A survey on applications and challenges. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. 10 (1), 1–24 (2021).

Mansoor, M. et al. A machine learning approach for non-invasive fall detection using Kinect. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81 (11), 15491–15519 (2022).

Thies, J., Zollhofer, M., Stamminger, M., Theobalt, C. & Nießner, M. Face2face: Real-time face capture and reenactment of rgb videos. in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition . 2387–2395 (2016).

Shad, H.S. et al. Comparative Analysis of Deepfake Image Detection Method Using Convolutional Neural Network. Vol. 2021 (2021).