- Quote of the Day

- Picture Quotes

Homework Quotes

Standart top banner.

Nothing is more powerful for your future than being a gatherer of good ideas and information. That's called doing your homework.

A genius is a talented person who does his homework.

Homework strongly indicates that the teachers are not doing their jobs well enough during the school day. It's not like they'll let you bring your home stuff to school and work on it there. You can't say, 'I didn't finish sleeping at home, so I have to work on finishing my sleep here.

Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration. As a result, a genius is often a talented person who has simply done all of his homework.

Homework is a term that means grown up imposed yet self-afflicting torture.

Persistence is important in every endeavor. Whether it's finishing your homework, completing school, working late to finish a project, or "finishing the drill" in sports, winners persist to the point of sacrifice in order to achieve their goals.

I like a teacher who gives you something to take home to think about besides homework.

Homework, I have discovered, involves a sharp pencil and thick books and long sighs.

You will never get anywhere if you do not do your homework.

We're doing our homework to make sure we're prepared.

Do your homework or hire wise experts to help you. Never jump into a business you have no idea about.

When was the last time you used the words 'teach me'? Maybe not since you started first grade? Here's an irony about school: The daily grind of tests, homework, and pressures sometimes blunts rather than stimulates a thirst for knowledge.

The more you do your homework, the more you're free to be intuitive. But you've got to put the work in.

College is about three things: homework, fun, and sleep...but you can only choose two.

The best schools tend to have the best teachers, not to mention parents who supervise homework, so there is less need for self-organised learning. But where a child comes from a less supportive home environment, where there are family tensions perhaps, their schoolwork can suffer. They need to be taught to think and study for themselves.

One of life's most painful moments comes when we must admit that we didn't do our homework, that we are not prepared.

To overcome stress you have to find out something. You've got to do some research and homework. You need to find out who you are today.

My life is a black hole of boredom and despair." "So basically you've been doing homework." "Like I said, black hole.

Do your homework, study the craft, believe in yourself, and out-work everyone.

Do as much homework as you can. Learn everybody's job and don't just settle.

If you want to be lucky, do your homework.

I'm learning skills I will use for the rest of my life by doing homework...procrastinating and negotiation.

You have got to pay attention, you have got to study and you have to do your homework. You have to score higher than everybody else. Otherwise, there is always somebody there waiting to take your place.

You don’t get rich off your day job, you get rich off your homework.

last adds STANDART BOTTOM BANNER

Send report.

- The author didn't say that

- There is a mistake in the text of this quote

- The quote belongs to another author

- Other error

Homework quotes by:

- Richelle Mead Author

- J. K. Rowling Novelist

- Becca Fitzpatrick Author

- John Green Author

- Barack Obama 44th U.S. President

Top Authors

Get Social with AzQuotes

Follow AzQuotes on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. Every day we present the best quotes! Improve yourself, find your inspiration, share with friends

SIDE STANDART BANNER

- Javascript and RSS feeds

- WordPress plugin

- ES Version AZQuotes.ES

- Submit Quotes

- Privacy Policy

Login with your account

Create account, find your account.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

- Choose your language

- Books in English

- Other languages

- Infographics

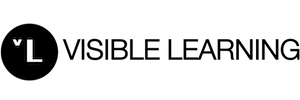

- Hattie Ranking

- John Hattie

John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: “Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero”, says Professor John Hattie. But what does really work in education, schools and classrooms around the world? Every week Sarah Montague interviews the people whose ideas are challenging the future of education, like Sugata Mitra, Sir Ken Robinson and the headmaster of Eton College Tony Little. In August John Hattie, Professor of Education at the University of Melbourne, was her guest at BBC Radio 4. You can listen to the whole interview with John Hattie following this link (28 mins). Here are some quick takeaways. If you want to read further about what works best in education you can order the books Visible Learning and Visible Learning for Teachers .

Visible Learning: Buy the book VL for Teachers: Buy the book

John Hattie about class size

“Well, the first thing is, reducing class size does enhance achievement. However, the magnitude of that effect is tiny. It’s about a hundred and fifth out of a hundred and thirty odd different effects out there and it’s just one of those enigmas and the only question to ask is why is that effect so small? Because it is small. And the reason, we’ve found out, that it’s so small is because teachers don’t change how they teach when they go from a class of thirty to fifteen and perhaps it’s not surprising.”

John Hattie about public vs private schools

“Here in England, if you take out the prior differences from going to a private school where they tend to get parents who choose, as oppose to them sent to the local school, they tend to get a brighter student, you take that out, there’s not much difference. In many places the government school would be better. So, it’s kind of ironic, in the last twenty years where we’ve pushed this notion that parents have choice, so they can choose the school that may not be in the best interest of their student.”

John Hattie about homework

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, “Is it really making a difference?” If you try and get rid of homework in primary schools many parents judge the quality of the school by the presence of homework. So, don’t get rid of it. Treat the zero as saying, “It’s probably not making much of a difference but let’s improve it”. Certainly I think we get over obsessed with homework. Five to ten minutes has the same effect of one hour to two hours. The worst thing you can do with homework is give kids projects. The best thing you can do is to reinforce something you’ve already learnt.”

John Hattie about streaming

“It doesn’t make a difference.” Sarah Montague: “But bright kids aren’t held back by less bright and less bright not suffering?” “No. No difference at all. No. Teachers think it’s easier for them and it may be but in terms of the effects of students, no. Now you’ve got to remember that a lot of students gain a tremendous amount of their learning from their other students in the class and variability is the way that you get more of that kind of learning from other students.”

Listen to the whole interview with John Hattie at BBC Radio 4 . If you want to read further you can order the books Visible Learning and Visible Learning for Teachers.

BBC Radio 4: The Educators . Sarah Montague interviews the people whose ideas are challenging the future of education. Episode 2: John Hattie Duration: 28 minutes First broadcast: 20 August 2014 Presenter: Sarah Montague Producer: Joel Moors.

38 comments on “ John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: “Homework in primary school has an effect of zero” ”

John Hattie Homework I beg to differ, depends on what type ! E.g. Cook a meal with mum or day, explain today’s Math to a family member, read the last chapter of a book, make a touch cast report of your pet, use time laps photography with your iPad to show the growth of a seed into a plant, find Mars using an iPad app, create a billboard online that promotes one of the current issues ….

And I quote: So, don’t get rid of it. Treat the zero as saying, “It’s probably not making much of a difference but let’s improve it”.

I agree. What can we do to give it a greater effect? “Flipped” classrooms for example have a great effect on student learning as modern research shows.

Spot on.I work in Dubai and that’s how we plan homework. No rote but just enriching linkage to lessons learnt. Our kids enjoy these and are eager to share their experiences and learn tremendously from each other! !

All well and good if the parents can afford an iPad……….

Spot on John. Also, maybe let them chose from several options an activity which is of interest to them.

Why Is no one pointing out the fact of once these kids go to a higher grades the shock of how much of a load of homework will be a complete wreck them. My son was in 4th and he had homework and he hated doing it now he’s in 5th and the no homework rule is in place but once he hits 6th grade he will have it as again and i know sixth grade is always a shock for most kids. So I strongly disagree so we give him reading every night and review with him what he learned in class each day

Good revision routines prepare kids adequately

I use to be an advocate for streaming but I was wrong… kids learn best when there are varied abilities in the room. Class sizes don’t matter… quality instruction … minimal instruction .. maximum participation for students… and yes homework is over rated.

Based on what research? Im not saying you’re wrong, just curious what facts you’re using to support your opinion.

very simple data and anecdotal evidence.

Empirical research from over 800 meta-analysis — hardly “simple data” nor “anecdotal”. Evidence-based.

It’s John Hattie, are you a dinosaur? What current educational research sites don’t draw on his ongoing research?

These comments are reflecting what research the Sutton trust has accumulated. It shows that homework and class size make no difference and the thing that makes the most difference is noticing children’s responses and adjusting immediately according to them. In my head, this is obviously easier to do well with a smaller class. So if you want good teaching and not burn teachers out trying to individually respond to 32 children in each lesson, then reducing class size will make a difference. But class size in itself doesn’t. I also think that we have a large number of children who need nurturing not just teaching facts. So again a smaller class is beneficial to this end.

When a class size goes down to 5 then there are massive differences in learning. I was on a college course and for some reason, which I have forgotten, there were only 5 students on my engineering course. The teacher had a much better understanding of what we knew and on the effect of his teaching. We all got straight A’s.

It’s all about the quality of what is happening in the learning environment not the number students. A good teacher will have a good impact with 14 or 40 kids. You have to change what you do to meet the needs of the students.

I believe class size does make a difference. It certainly did with my daughter. Not from a teaching perspective, but from a learning perspective. The more students in a classroom, the more distractions and behavioral issues there are. My daughter is not a child who is easily distracted, but two years ago, she left public school and switched to online learning with a small amount of students in her class. She said there is a huge difference in the number of times the teacher has to stop the lesson in order to reprimand a student.

If students spent the first 3 years K-2 learning to get along in a classroom-how to work as a group and other social skills, there would be less disruptions in classrooms. Sone children at that you age are not neurologically developed enough to handle all of the reading, writing and math thrown at the lower grade levels. Throw some numbers and letters at them while building on their social skills and they will be much more successful students from 3rd grad and up.

The problem with Hattie’s research is that it is not primary school based but rather based across all schools from preschool to tertiary. Smaller classes make a huge difference especially in the junior school and it is covert teacher bashing to say that the teachers don’t change with smaller classes. They can and they do. They can’t with larger classes no matter how skilled they are. It’s the same with home work. If the homework is being encouraged to work with mum or dad in the kitchen or the garden por encouraging parents to read and act out stories with their children these will make massive differences to achievement.

I agree completely. Last year I was lucky enough to have a class of 18 for the best part of the year. I do believe the spring in my step made me a better teacher. A number of my D students became B’s. I believe in a normal class grouping I would have been lucky to get them to a C. I don’t think Prof. Hattie can measure my stress levels. There was so much joy in teaching my little group of children!

Jules, I completely agree with you. Hattie has, as far as I’m aware, never done research on the effect of larger/smaller class sizes on teacher stress levels and less/more time to think, prepare and spend more time with individual students. Of course, there are methods designed to maximise the learning of larger classes, but there is a huge time saving in marking a class of 18 essays to marking, say, 30. The time saved can be invested in lesson preparation, or even, time to just think! John Hattie was a maths teacher, though, so I guess he didn’t mark too many essays…

Jules you are so right! With the complexities of children’s personal lives having a smaller class enables us to have time to address their individual needs both personally and academically. We can then feel happier in our ability to fulfill each child’s needs which gives another avenue to help reduce our stress levels.

Not a fan of homework, except as a little revision, especially in primary school. My 5 children attended a state primary school, which had multi-age classrooms, which assisted children to learn at their own pace. It worked. It was also a Glasser school, which helped with socialisation. My eldest child is 27, and has Asperger’s Syndrome. The other 4 have all been accepted at tertiary institutions. All but one of those 4 were educated completely at state schools, with 1 attending a private school for her last 3 years of school, at her own request, for social (not academic) reasons. Perhaps children, especially boys, should begin school at a later age.

Having read and used Professor Hattie’s research in order to make positive impacts on student learning and outcomes, and having listened to many interviews, I can honestly say I have never felt that he covertly bashes teachers with his findings. The opposite in fact. I have always found Professor Hattie to speak positively of teachers. As a teacher, I wish more people in the public arena would validate what we do.

hang on. I remember like it was yesterday that when I was put down a group I immediately sank down to the equivalent level in that group. Ie in footballing terms, relegation zone in premiership led to relegation zone in championship. And how come nobody mentions the threat of being beaten up (let’s call it bullied) for doing well in the “second set” group? That was also a very real threat. You certainly didnt want to shine once you were relegated. Why does nobody mention this? Presumably this is a neutral site?

I agree as a parent i believe homework makes a difference….provided parent/s are involved. 1. I know what my child is learning in school. 2. I can pick up what my child needs extra attention to work on, help her with it and bring this to the teacher’s attention. 3. Show an interest in what my child is doing during her day. Only helps build on a stronger family unit.

Why is it, that never is there a word about student behaviour and the huge effect it has on learning, not just for the behaviour problem students, but for all children within that classroom! Unacceptable behaviour can keep a classroom in an upheaval . Also, the undesirable effects of hard drugs while in the womb…also alcohol! Then we have undernourishment and exhausted children. And we must not forget the trauma many are experiencing…separated parents, bickering parents, living in households where adults are smoking inside, eating a diet of processed foods, a parent or parents drinking to extremes on a daily basis, sexual abuse, seeing a parent being abused… and I could go on! All of these things and more are what many children are experiencing on a daily basis. Change will take place in the classroom and learning will take place when things change first in our homes and in our lives. It is the parents responsibility and we need to hand it back to them!

Couldn’t agree more with Elizabeth’s comments – but when you have an inspired and passionate teacher who can see beyond the behaviour and identify the effects of trauma in a youngster – the impact on that child, that class can be huge! Critical skills training can be invaluable – visible learning at worst can lead to children becoming statistics in the forensic analysis of data when actually they will gain more and teachers will have more of an impact with 5 minutes of care and concern and perhaps being the only person that has spent 5 minutes 1:1 with that child! Real relational trust takes time and genuine concern and interest in children developing and progressing – what is an assessment capable learner? Sounds like a robot!

Behavior is a big learning factor for the student with behaviors and those around them. Our son has a diagnoses with multiple co-morbids ADHD/Anxiety/OCD/Depresson/PTSD/Sensory disorder. The depression and PTSD was brought on in his therapist’s opinion by using peers to assist in helping other students, which doesn’t always have a positive impact and bullying at school.

It got to the point where he was taking 3 stimulants, a mood stabilizer and an anxiety med just to make it through the school day. And then he’d come home and have so much homework he never got to go outside to run off his excessive energy and then 3 more pills to bring him down so he could sleep. Not to mention the ill side effects of weight gain (he’s a 7th grader now 5’5 and weighs 200 pounds thats horrifying).

We pulled him out of mainstream school last year, weaned him off all meds and home school now. His self confidence is building, the weight is slowly coming off and he’ll be done early with the program we bought mainly because he can fly thru what interests him and he already has a wealth of information on and he can spend more time working on new information. We APPLY his lessons to his every day life.

All that being said maybe less pressure should be put on the child having homework and more time spent on educating parents about what their child is being taught and how to apply it to their every day life. As a daycare provider I know that not all parents will back a teacher up but I do think that they’d be surprised how many parents would.

Very interesting thoughts. To say it has zero effect seems a bit far fetched for all students. It depends on the quality of the school and quality of life at home. I work with low income students who seem to not have much education at home. The homework the teachers send helps us evaluate where the children are and help increase their education even if the parents are not involved in their education. Children with strong support systems probably benefit by helping around the house more and being a great part of the community.

Hattie’s work should be taken for what it is–superficial with blunders https://ollieorange2.wordpress.com/2014/09/24/half-of-the-statistics-in-visible-learning-are-wrong-part-2/

Yes I agree with Hattie when he says, “a lot of students gain a tremendous amount of their learning from their other students in the class.” Empirical evidence in my class has shown for those who are “not into” a particular subject, their influence (teaching) on others to fall behind, not engage in activities and not do the work is infectious. Make it more interesting people say, how interesting can you make a football game for those wanting to do ballet? Put them on the field and they will learn though, they will learn to avoid playing against the Alphas at all costs so the best solution, get into trouble to avoid having to integrate, cause trouble so the lessons gets dragged out. All of these theories I’m sure work, but it needs a tag line: They work “in the ideal world.” The fact is that we don’t live in one.

I’m not sure what you mean by integrate? Please forgive me if I’m wrong. I take your comment to say that if a child doesn’t itegrate into the classroom setting, they’ll fail at adulthood?

We have two older children with ADHD and they never truly integrated into the school system but outside school in their ongoing education and career’s they’ve chose career’s in fast paced, every changing fields one medical, one education and they’re excelling. Failure to integrate into a classroom setting does not automatically set a child up for failure in their adult life.

It’s parents who drive the homework. They think it’ll make their kids smarter. Teachers are under pressure to give kids extra work. A lot of teachers would rather not give homework. Reading with an adult is the best thing you can do for your child.

Teaching kids to be happy versus give them more work so they dont have time to find out for themselves or worse keeping them miserable

Homework that reinforces the application of skills and knowlegde already taught will prove to be purposeful. The time spent on homework must be in keeping with the concentration span of the child. It should not be an extension of the school day. 6 to 9 year olds learn best through play. Written tasks rob them of that opportunity to explore whilst developing valuable life skills.

When we know better, our moral obligation is to do better. Saying, “Yeah, I see this research. It just doesn’t fit with what I believe” is a profession of non-professionalism.

Hattie is a fraud. Unfortunately, many seem to have been taken in by his profoundly flawed research and his political motives.

11 other websites write about for "John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: “Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”"

[…] What really works in education, schools and classrooms around the world? Every week Sarah Montague interviews the people whose ideas are challenging the future of education, like Sugata Mitra, Sir Ken Robinson and the headmaster of Eton College Tony Little.…Read more › […]

[…] may be interested in John Hattie’s homework interview on the BBC recently. Professor Hattie is a leading and highly regarded educationalist and his […]

[…] What really works in education, schools and classrooms around the world? […]

[…] synest å seie at elevar med mykje lekser får dårlegare karakterar, medan velkjende John Hattie konkluderer med at “homework in primary school has an effect of […]

[…] John Hattie […]

[…] Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. John Hattie BBC interview. […]

[…] John Hattie, Professor of Education at the University of Melbourne, was her guest at BBC Radio 4. Read more or listen to the full […]

[…] educational researcher John Hattie interviewed on a few matters including Homework. Here’s the clip to listen […]

[…] prøver å være må vi ta inn over oss den forskning som er på lekser. Tradisjonelle lekser er verdiløse læringsinstrumenter i småskolen. Forskeren John Hattie (Det er han vi bruker for å fortelle at «forskning viser at […]

[…] First we explore our memories of homework as students, then our experiences as teachers, before introducing an outside source, in this episode,it’s ASCD’s article which quotes the The National PTA and the National Education Association “10-minute rule.” Also, check out John Hattie’s research on homework “effect size” here. […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- شيخ روحاني on Hattie Ranking: 252 Influences And Effect Sizes Related To Student Achievement

- Pete Gabriella on Professor John Hattie

- Steve Capone on Video: John Hattie’s keynote at the Whole Education Annual Conference

- Phillip Cowell on Collective Teacher Efficacy (CTE) according to John Hattie

- simon on The Economist: John Hattie’s research and “Teaching the teachers”

- Susan Begin on Visible Learning World Conference 2019

- Anna on What is your experience?

- Rebekah Camp on Hattie Ranking: 252 Influences And Effect Sizes Related To Student Achievement

- Effective School Communications In The Summer | The Blogging Adviser on Hattie Ranking: 252 Influences And Effect Sizes Related To Student Achievement

- Sebastian Waack on Hattie Ranking: 252 Influences And Effect Sizes Related To Student Achievement

share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

New fish species discovered in Mauritanian deep-water coral reefs

1 minute ago

New supramolecular polymer shows spontaneous unfolding and aggregation

'Molecular Compass' points way to reduction of animal testing

Pioneering research discovers PFOS chemical pollution in platypuses

5 minutes ago

New research analyzes 'Finnegans Wake' for novel spacing between punctuation marks

17 minutes ago

Genomic research focuses on medical potential for scorpion venom

36 minutes ago

New forensics technique measures individual DNA shedding to aid criminal investigations

38 minutes ago

Novel ratchet mechanism uses a geometrically symmetric gear driven by asymmetric surface wettability

43 minutes ago

'Amazon' algae shed light on what happens to populations when females switch to asexual reproduction

51 minutes ago

New simulations shed light on stellar destruction by supermassive black holes

54 minutes ago

Relevant PhysicsForums posts

Incandescent bulbs in teaching.

19 hours ago

How to explain Bell's theorem to non-scientists

Aug 18, 2024

Free Abstract Algebra curriculum in Urdu and Hindi

Aug 17, 2024

Sources to study basic logic for precocious 10-year old?

Jul 21, 2024

Kumon Math and Similar Programs

Jul 19, 2024

AAPT 2024 Summer Meeting Boston, MA (July 2024) - are you going?

Jul 4, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

Statistical analysis can detect when ChatGPT is used to cheat on multiple-choice chemistry exams

Aug 14, 2024

Larger teams in academic research worsen career prospects, study finds

The 'knowledge curse': More isn't necessarily better

Aug 7, 2024

Visiting an art exhibition can make you think more socially and openly—but for how long?

Aug 6, 2024

Autonomy boosts college student attendance and performance

Jul 31, 2024

Study reveals young scientists face career hurdles in interdisciplinary research

Jul 29, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

The New York Times

Advertisement

The Opinion Pages

Homework’s diminishing returns.

Harris Cooper is chairman of the department of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University and author of "The Battle Over Homework."

Updated December 12, 2010, 7:00 PM

The horror stories I hear from parents and students about five or more hours spent on homework a night fly in the face of evidence of what’s best for kids, even what’s best for promoting academic achievement.

After a certain amount of homework the positive effect on achievement disappears, and even might turn negative.

My colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students’ scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. This happens regardless of grade level and subject matter.

Yet other studies simply correlate the amount of homework students do and their achievement. These studies don’t attempt to control for student differences. About three-quarters find the link between homework and achievement is positive. But, most interesting, these results also suggest that after a certain amount of homework the positive relationship disappears and might even get negative.

So, research is consistent with the notion that homework can be a good thing if the dose is appropriate to the student’s age or developmental level.

How much homework should students do? The National PTA and the National Education Association have a parent guide that suggests 10-20 minutes of homework in grades K-2, 30 to 60 minutes in grades 3-6. Many school district policies state that high school students should expect about 30 minutes of homework for each academic course they take, a bit more for honors or advanced placement courses. Educators refer to this as “the 10 Minute Rule”: multiply a child’s grade by 10 and that’s the rough guide for minutes of homework a night. That recommendation is consistent with the conclusions reached by our research analysis.

A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits and learn skills developed through practice. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and two and half hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can help students develop good study habits as their cognitive capacities mature, foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents opportunity to see what’s going on at school.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects, like increasing boredom with schoolwork and reducing the time students have to spend on leisure activities that teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework — pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques from those used by the teacher.

My feeling is that the effects of homework depends on how well, or poorly, it is used. In general, teachers should avoid extremes. All children can benefit from homework but it is a very rare child who will benefit from hours and hours of homework. The fact is, too much homework not only crowds out time for other activities and increases stress on kids but there is no evidence that those last three hours of a five hour homework binge accomplishes what it set out to do, improve learning.

Topics: Education , schools , students

What Happened to Childhood?

The Home-School Advantage

Stress and the high school student, reconsider attitudes about success.

It Starts Before High School

Change the Pace of the School Day

Related Discussions

Recent Discussions

Homework: An Hour a Day Is All the Experts Say

Too much homework can be counterproductive..

Posted April 20, 2015

- What Is Stress?

- Take our Burnout Test

- Find a therapist to overcome stress

How much time does your teen spend doing busy school work each night? According to a recent study, if it's more than one hour… then it's too much. A study from Spain published in the Journal of Educational Psychology by the American Psychological Association found that spending more than one hour on math and science homework can be counterproductive. Students seem to gain the most benefit when a small amount of homework is consistently assigned, rather than large portions assigned at once.

The study examined the performance of 7,725 public and private school students (mean age 13.78 years). Students answered questions about the frequency of homework assigned and how long it took them to complete assignments. Researchers looked at standardized tests to examine academic performance in math and science. They found that students in Spain spent approximately one to two hours per day doing homework. Compare that to studies that indicate American students spent more than three hours a day doing homework!

Researchers found that teachers who assigned 90-100 minutes of homework per day had students who performed poorer on standardized tests than those with less homework. However when teachers consistently assigned small amounts of homework students scored nearly 50 points higher on standardized test than those who had daunting amounts of homework. Another interesting finding from this study was students who were assigned about 70 minutes of homework, of which they needed help from someone else to complete, scored in the 50th percentile on standardized tests. Whereas those who were assigned the same amount of homework, but could do it independently, scored in the 70th percentile. So clearly, not only is the amount of homework assigned of importance, but so is the ability to master it independently.

There are several possible explanations for these findings. First, teachers may be using homework as a means to cover what was not completed in class. So rather than practicing concepts taught in class, students are left to self-teach material not covered in class. Homework should supplement learning, and not be used as a tool to keep up with a curriculum pacing guide. Another explanation for testing gains is those who work to master material independently experience more academic success.

The study out of Spain supports findings from another study published a year ago published in the Journal of Experimental Education which found that too much homework can have a negative impact on teens’ lives outside of the academic setting. In this study, researchers surveyed 4,317 American high school students’ perceptions about homework, in relation to their well-being and behavioral engagement in school work. On average, these students reported spending approximately 3.1 hours of homework each night—a far reach from the hour per night recommendation by the first study.

This second study found that too much homework can be counterproductive and diminish the effectiveness of learning. The negative effects of lots of homework can far outweigh the positive ones. Researchers found that a lot of homework can result in:

Students reported high levels of stress associated with school work. Below is the breakdown of student responses.

56% of students in this study reported that homework was a primary source of stress 43% of students in this study reported that tests were another source of stress 33% of students in this study reported that pressure to get good grades was a source of stress

• Physical Problems:

Students reported that homework led to:

poor sleep frequent headaches gastro intestinal problems weight loss/gain.

• Social life problems.

How can students expect to spend time with others when they are too busy completing homework? Students reported that having too much school work keeps them from spending time with friends and family.

Plus too much school work keep them from participating in extra-curricular activities and engaging in activities they enjoy doing. Interestingly, many students reported that homework was a “pointless” or “mindless” way to keep their grades up. In other words… it was "busy" work.

When is homework beneficial? If homework is used as a tool to facilitate learning and reinforce concepts taught in the classroom then it enriches students academic experience. While homework does serve a purpose, so does having a life outside of school. Sometimes social development can be just as important as academic development. So the answer may be helping youth find a balance between school and social life.

Journal Reference:

Rubén Fernández-Alonso, Javier Suárez-Álvarez, José Muñiz. Adolescents’ Homework Performance in Mathematics and Science: Personal Factors and Teaching Practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 2015; DOI:10.1037/edu0000032

Raychelle Cassada Lohman n , M.S., LPC, is the author of The Anger Workbook for Teens .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids