Qatar is welcoming 102 countries visa-free, check your visa status here .

Visit Qatar App Explore things to do in Qatar!

Get eVisa info

Select your language

Geography of Qatar

A visit to Qatar means finding that centre point between contrasts few other landscapes can match. With our country’s compact size and unique geography, you’ll find desert dunes in reach of crystal-clear waters, and ultra-modern cities like our capital Doha surrounded with ancient villages and cultural wonders.

Qatar peaks out from the continent to create what many call the pearl of the Arabian Peninsula. Our country’s compact land mass extends north into the Persian Gulf in Western Asia. In the south, Qatar shares a border with Saudi Arabia, and the rest borders only restful waters.

Climate of Qatar

Qatar’s desert climate offers year-round sunshine, with balmy summers and pleasant, refreshing winter temperatures.

A compact peninsula

Qatar is only 11,437 km2 in size, making it easy to explore all its many treasures.

Wave to our neighbours

We share a single 87 km land border in the Middle East with Saudi Arabia, and only a narrow gulf separates us from Bahrain.

Discover Qatar’s rolling desert dunes

Qatar’s striking crescent-shaped dunes move with the sands of time as Al Shamal winds blow across the sloped plains. Ancient hills and mountains surround these plains painted with black and brown tones. The highest peak can be found at Qurain Abu al-Bawl in the south of Qatar, just 103 m above Qatar’s lowest point at 0 m sea level.

BLUE WATERS LIE BEYOND THE DESERT

Qatar’s coastline stretches 563 km with beaches of white sand and serene sea water that ranges from turquoise to deep blue. All along the coast, there are little spots of paradise on ten islands, some of which offer great sights and resorts.

Fuwairit Beach

Khor Al Adaid Beach

Zekreet Beach

Al Safliya Island

Al Aaliya Island

Purple Island

Madinat Ash Shamal

Come and have a closer look at Qatar’s landscapes

Find your way to Qatar

Qatar is blessed with natural resources

Our beautiful country is not just blessed with landscapes fit for geography textbooks, but also with plenty of natural resources – particularly as one of the world’s biggest providers of natural gas.

Qatar holds between 10% and 14% of the world’s known natural gas reserves, and our offshore North Field is one of the world’s largest gas fields. Before the shift towards natural gas, Qatar’s economy was more dependent on the export of oil found along the western coast at Dukhān and offshore from the eastern coast.

The discovery of oil in Qatar in 1939 set about rapid changes and modernisation. It created vast opportunities and Qatar’s population boomed as a result. Today, Qatar is known more for its natural gas than for its oil, but still holds 25 244 000 000 barrels of proven oil reserves, ranking 13th in the world.

Did you know? Qatar has no rivers and only gets about 10 cm of rain on average every year. To make sure there is enough drinking water, Qatar makes use of desalination plants to make seawater drinkable.

Every visit to Qatar starts with a feeling

Go on a journey of the senses through Qatar. We’ll inspire you to start imagining your own story.

Discover the best places to visit with family

Get ready for exciting Qatar adventures

With warm Gulf waters and year-round sunshine, discover you go-to place for unforgettable beach experiences

Qatar is a heart-stirring treasure trove of art and culture like you’ve never experienced before

Excite your taste buds as you dine your way through Qatar’s cuisine-rich peninsula

Indulge your every whim with our guide on Qatar’s best luxury hotels, hammam spas and fine dining

Find a haven of peace at a luxury spa in Qatar, where rejuvenation has become an art form

Make unforgettable memories with our insider guide to places to visit in Qatar for couples

Things to know before travelling

Want to travel visa-free? Check if you qualify here.

Getting here

Planning your trip to Qatar? Check how to get here.

Travel tips

Make the most of your visit with our handy travel guide.

Getting around

From a dhow boat to our world-class metro, here’s how to easily explore Qatar.

- Latest edition

- Media Centre

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy notice

- Corporate website

- Amiri Diwan

- Cookie policy

- Qatar Tourism brand logos

- Subscribe to our newsletter

- Cookie settings

© 2024 Qatar Tourism | All rights reserved

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The Thani dynasty and British protectorate

Independence and final decades of the 20th century, emerging regional influence, international scrutiny and rift with arab allies.

history of Qatar

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Table Of Contents

history of Qatar , a survey of notable events and people in the history of Qatar in the modern era.

Qatar’s modern history begins conventionally in 1766 with the migration to the peninsula of families from Kuwait , notably the Khalifah family. Their settlement at the new town of Al-Zubārah grew into a small pearl-diving and trade centre. In 1783 the Khalifah family led the conquest of nearby Bahrain , where they remained the ruling family throughout the 20th century. Following the departure of the Khalifah dynasty from Qatar, the country was ruled by a series of transitory sheikhs, the most famous of whom was Raḥmah ibn Jābir al-Jalāhimah, known particularly for his maritime warring with the Khalifah family and their associates.

Qatar came to the attention of the British in 1867 when a dispute between the Bahraini Khalifah, who continued to hold some claim to Al-Zubārah, and the Qatari residents escalated into a major confrontation, in the course of which Doha was virtually destroyed. Until the attack, Britain had viewed Qatar as a Bahraini dependency. It then signed a separate treaty with Mohammed ibn Thani in 1868, setting the course both for Qatar’s future independence and for the rule of the Thani dynasty , who until the treaty were only one among several important families on the peninsula.

Ottoman forces, which had conquered the nearby Al-Ḥasā province of Saudi Arabia, occupied Qatar in 1871 at the invitation of the ruler’s son, then left following the Saudi reconquest of Al-Ḥasā in 1913. In 1916 Britain signed a treaty with Qatar’s leader that resembled earlier agreements with other Gulf states, giving Britain control over foreign policy in return for British protection.

In 1935 Qatar signed a concession agreement with the Iraq Petroleum Company; four years later oil was discovered. Oil was not recovered on a commercial scale, however, until 1949. The revenues from the oil company, later named Petroleum Development (Qatar) Limited and then the Qatar Petroleum Company, rose dramatically. The distribution of these revenues stirred serious infighting in the Thani dynasty, prompting the British to intervene in the succession of 1949 and eventually precipitating a palace coup in 1972 that brought Sheikh Khalifa ibn Hamad Al Thani to power.

In 1968 Britain announced plans to withdraw from the Gulf. After negotiations with neighbouring sheikhdoms—those of the present United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.) and Bahrain —Qatar declared independence on September 3, 1971. The earlier agreements with Britain were replaced with a treaty of friendship. That same month Qatar became a member of the Arab League and of the United Nations . In 1981 the emirate joined its five Arab Gulf neighbours in establishing the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), an alliance formed to promote economic cooperation and enhance both internal security and external defense against the threats generated by the Islamic revolution in Iran and the Iran-Iraq War .

Qatari troops participated in the Persian Gulf War of 1990–91, notably in the battle for control of the Saudi border town of Raʾs al-Khafjī on January 30–31. Doha, which served as a base for offensive strikes by French, Canadian, and U.S. aircraft against Iraq and the Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait, remained minimally affected by the conflict.

Renewed arguments over the distribution of oil revenues also caused the 1995 palace coup that brought Sheikh Khalifa’s son, Sheikh Hamad , to power. Although his father had permitted Hamad to take over day-to-day governing some years before, Khalifa contested the coup . Before Hamad fully consolidated his power, he had to weather an attempted countercoup in 1996 and a protracted lawsuit with his father over the rightful ownership of billions of dollars of invested oil revenues, which was finally settled out of court.

During the 1990s Qatar agreed to permit U.S. military forces to place equipment in several sites throughout the country and granted them use of Qatari airstrips during U.S. operations in Afghanistan in 2001. These agreements were formalized in late 2002, and Qatar became the headquarters for American and allied military operations in Iraq the following year.

Qatar in the 21st century

Rising demand for natural gas propelled the economy to new heights in the first decade of the 21st century and provided funds for Qatar’s efforts to lift itself from relative obscurity to a position of greater prominence in the Middle East . The Qatari government invested heavily in development with a special focus on prestigious cultural projects, including museums and extension campuses for foreign universities. Qatar also sought to cultivate a reputation for openness and political independence; this effort was perhaps exemplified by Qatar’s sponsorship of Al Jazeera , a popular satellite television network known for its largely independent news coverage, which often included criticism of authoritarian Arab governments and U.S. policy in the Middle East . Notably absent from the network’s broadcasts was criticism of Qatar, although the country remained an absolute monarchy and continued to host a large U.S. military base.

One hallmark of Qatar’s foreign policy was its cordial ties with a wide range of Middle Eastern countries and groups, which in some cases required balancing between regional rivals such as Iran and Saudi Arabia or between secular governments and Islamist opposition groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood . With a reputation for impartiality, Qatar sought out opportunities to bolster its international standing by serving as a mediator in Middle East disputes. These efforts met with mixed success: a 2007 accord brokered by Qatar between the Yemeni government and Houthi rebels fell apart within months, but in 2008 Qatar proved instrumental in resolving a factional standoff in Lebanon that had threatened to develop into armed conflict.

The outbreak of popular uprisings against many of the entrenched regimes of the Middle East in 2011 provided new opportunities for Qatar to shape events in the region. In Libya Qatar took an active role in supporting the rebellion against the regime of Muammar al-Qaddafi , providing weapons and funds to the rebels and contributing military assets to the NATO -led mission to enforce a no-fly zone. In Syria Qatar played an important part in the Arab League ’s attempts to broker a peace agreement between the regime of Bashar al-Assad and the opposition. When the agreement failed in 2012, Qatar took the side against Assad, sending weapons and financial aid to the rebels. In Egypt, Qatar continued its long-standing support of the Muslim Brotherhood, providing billions of dollars to the Muslim Brotherhood-led government of Mohamed Morsi , elected in 2012.

In June 2013 the 61-year-old Hamad announced his abdication in favour of his 33-year-old son, Sheikh Tamim , the crown prince, citing the need to make way for a new generation of Qatari leaders. The transfer of power was seen as unusual for the Gulf Arab region, where rulers typically occupied their positions for life.

Tamim’s leadership was tested early in his reign by a series of setbacks to Qatar’s activist foreign policy. In Egypt, Morsi was ousted by a coup in July 2013, and the Muslim Brotherhood was driven underground by a harsh crackdown, while Libya and Syria—two countries where Qatar had been arming opposition groups—sank into chaos . In March 2014, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates—Qatar’s neighbours and fellow members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)—registered their irritation with Qatar’s independent foreign policy and its support of the Muslim Brotherhood by withdrawing their ambassadors from Doha. The ambassadors were reinstated in November after Qatar showed a willingness to distance itself slightly from the Muslim Brotherhood and reconcile with the new government of Egypt led by Pres. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi .

Tensions between Qatar and its Gulf neighbours reached a new level in June 2017 when a coalition of countries led by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Bahrain cut diplomatic ties with Qatar and imposed an economic blockade. Saudi and U.A.E. officials justified the blockade as a necessary measure to counter Qatar’s alleged support for militant Islamist groups and its friendly relations with Iran , Saudi Arabia’s primary regional rival.

Qatar remained defiant, though, refusing to comply with a list of demands that it dismissed as placing unacceptable restrictions on Qatari sovereignty . Despite an initial shock to the country’s economy, Qatar’s wealth and business-friendly environment enabled it to absorb early losses and reorient its economy. For example, while dairy products disappeared from shelves at the onset of the blockade, Qatar used its wealth to fly thousands of cows into the country and became self-sufficient in dairy. In 2018 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that the impact of the blockade on Qatar’s economy was “manageable” because of measures undertaken by the government to mitigate its effects.

Moreover, Qatar readjusted its international relationships. It shifted its trade away from its neighbours and increased trade with Turkey , Iran, Kuwait , and Oman as well as with countries in Southeast Asia . Qatar announced in December 2018 that in the following month it would leave OPEC , a multinational organization that coordinates petroleum policies and wherein Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are two of the top producers. Days later Qatar’s emir skipped the annual summit of the GCC (of which Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain are also members) and was represented instead by an envoy .

After several years under the blockade, Qatar showed little sign that it would accede to demands. Its growing ties with Iran, meanwhile, undermined efforts by the United States and the Arab Gulf countries to isolate Iran.

In January 2021 the blockade was lifted amid mounting pressure on Qatar’s neighbours. But despite the relief in tensions in the region, Qatar faced renewed international scrutiny over human rights issues as it prepared to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup .

- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Qatar

Culture Name

Orientation.

Identification. Residents of Qatar can be divided into three groups: the Bedouin, Hadar, and Abd. The Bedouin trace their descent from the nomads of the Arabian Peninsula. The Hadar's ancestors were settled town dwellers. While some Hadar are descendants of Bedouin, most descend from migrants from present-day Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan and occasionally are referred to as lrani-Qataris. Alabd , which literally means "slaves," are the descendants of slaves brought from east Africa. All three groups identify themselves as Qatari and their right to citizenship is not challenged, but subtle sociocultural differences among them are recognized and acknowledged.

Location and Geography. Qatar is a small peninsula on the western shore of the Arabian Gulf that covers approximately 4,247 square miles (6,286 square kilometers). The landmass forms a rectangle that local folklore describes as resembling the palm of a right hand extended in prayer. Neighboring countries include Bahrain to the northwest, Iran to the northeast, and the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia to the south. Qatar and Bahrain both claim the uninhabited Hawar Islands just west of Qatar. Until recently, only small semipermanent seasonal encampments existed in the interior desert. Water resources near the coast combined with opportunities for fishing, pearl diving, and seagoing trade have supported larger, more permanent settlements. These settlement patterns have contributed to the social differentiation between Bedouin and Hadar.

Demography. In 1998, the population was estimated at 579,000. Most estimates agree that only about 20 percent of the population are Qatari, with the remainder being foreign workers. A total of 91.4 percent live in urban areas, mostly in the capital. Because male foreign laborers come without their families, there is an imbalance of males and females in the total population. The foreign workers, mostly from India and Pakistan, cannot obtain citizenship and reside in the country on temporary visas.

Linguistic Affiliation. The official language is Arabic. English, Farsi, and Urdu are widely spoken. Arabic is closely associated with the Islamic faith; thus, its use reinforces the Islamic identity of the nation and its citizens. The Qatari dialect of Arabic is similar to the version spoken in the other Gulf States and is called Arabic. The adjective khaleeji ("of the Gulf") that is used to describe the local dialect also distinguishes citizens of the six Gulf States from north African and Levantine Arabs.

Farsi, the official language of Iran, is also widely spoken by families that trace their descent from that country. As a result of the influx of foreign workers, many other languages are commonly spoken, including English, Urdu and Hindi, Malalayam, and Tagalog. While many Qataris speak more than one language, it is very rare for immigrants to learn Arabic. Interactions between Arabs and foreign workers are conducted in English or the language of the expatriate.

The date on which Qatar received independence from Great Britain in 1971 and the anniversary of the ruler's accession to office are celebrated as national holidays. The nation's flag, the state seal, and photographs of the rulers are displayed prominently in public places and local publications. Qataris also celebrate Islamic holidays.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. In the 1760s, members of the Al-Khalifa of the Utub tribe migrated to Qatar from Kuwait and central Arabia and established a pearling and commercial base in Zubarah in the north. From there the Al-Khalifa expanded their territory by occupying Bahrain, which they have ruled ever since. The Al-Thai, the current ruling family, established themselves after years of contention with the Al-Khalifa, who still held claims to the Qatar peninsula through most of the nineteenth century. In 1867, Britain recognized Mohammad bin Thani as the representative of the Qatari people. A few years later, Qasim Al-Thani (Mohammad's son) accepted the title of governor from the Ottoman Turks, who were trying to establish authority in the region. Qasim Al-Thani's defeat of the Turks in 1893 usually is recognized as a confirmation of Qatar's autonomy. In 1916, Abdullah bin Qasim Al-Thani (Qasim's son) entered an agreement with Britain that effectively established the Al-Thani as the ruling family. That agreement provided for British protection and special rights for British subjects and ensured that Britain would have a say in Qatar's foreign relations. The increase in state income from oil concessions strengthened the Al-Thani's position.

When Britain announced its intention to withdraw from the region, Qatar considered joining a federation with Bahrain and the seven Trucial States. However, agreement could not be reached on the terms of federation, and Qatar adopted a constitution declaring independence in 1971. The constitution states that the ruler will always be chosen from the Al-Thani family and will be assisted by a council of ministers and a consultative council. The consultative council was never elected; instead, there is an advisory council appointed by the ruler. Despite periodic protests against the concentration of power and occasional disputes within the ruling family, the Al-Thani's size, wealth, and policies have maintained a stable regime.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Doha, the capital, houses more than 80 percent of the population. Its parks, promenade, and award-winning waterfront architecture are considered as the centerpiece of Doha. The large-scale land reclamation project undertaken by the government to create those waterfront properties is recognized as a major engineering feat and a symbol of the country's economic and technological advancements.

Smaller towns such as Dukhan, Um Said, and Al Khor have become centers of the oil industry, and Wakrah, Rayyan, and Um Slal Mohammad have grown as suburban extensions of Doha. Smaller villages are spread throughout the desert interior. Village homes often are kept as weekend retreats for urban residents and as links to the tradition of desert nomads.

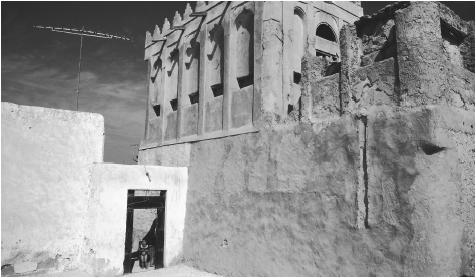

Doha's cityscape represents an attempt to fuse the modern with the traditional. At the start of the building boom in the 1960s, little thought was given to aesthetics; the objective was to build as quickly as possible. As the pace of development slowed, more consideration was given to developing a city that symbolized Qatar's new urban character and global integration. Designs were solicited that used modern technologies to evoke the nation's past. The main building of the university has cube-shaped towers on the roof. Those towers, with stained glass and geometric gratings, are a modernist rendition of traditional wind towers. The university towers are decorative rather than functional; however, they are highly evocative of Qatar's commitment to the lifestyles of the past while encouraging economic and technological development. Similar examples are found in government and private buildings. Many building designs incorporate architectural elements resembling desert forts and towers or have distinctively Islamic decorative styles executed in modern materials.

Homes also symbolize people's identities. The homes of Qatari citizens are distinct from the residences of foreign workers. The state provides citizens with interest-free loans to build homes in areas reserved for low-density housing. Foreign workers live in rental units or employer-provided housing and dormitories.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. The presence of foreign workers has introduced foods from all over the world. Qatar's cuisine has been influenced by close links to Iran and India and more recently by the arrival of Arabs from North Africa and the Levant as well as Muslim dietary conventions. Muslims generally refrain from eating pork and drinking alcohol, and neither is served publicly.

Foods central to Qatar's cuisine include the many native varieties of dates and seafood. Other foods grown locally or in Iran are considered local delicacies, including sour apples and fresh almonds. The traditional dish machbous is a richly spiced rice combined with meat and/or seafood and traditionally served from a large communal platter.

The main meal is eaten at midday, with lighter meals in the morning and late evening. However, with more Qataris entering the workforce, it is becoming more common to have family meals in the evenings. The midday meal on Friday, after prayers, is the main gathering of the week for many families. During the month of Ramadan, when Muslims fast from dawn to dusk, elaborate and festive meals are served at night.

Coffee is a central feature of the cuisine. Arabian coffee made of a lightly roasted bean that is sweetened and spiced with cardamon is served in small thimble-shaped cups to guests in homes and offices. Most households keep a vacuum jug of coffee and sometimes tea ready for visitors. Another beverage, qahwa helw (sweet coffee), a vivid orange infusion of saffron, cardamon, and sugar, is served on special occasions and by the elite.

In recent years, restaurants and fast-food franchises have opened. Those establishments primarily serve foreign workers. Qataris, especially women, are reluctant to eat in public places; but will use the drive-through and delivery services of restaurants. Qatari men sometimes socialize and conduct business in restaurants and coffeehouses.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The primary axes of social stratification are the nationality and occupation. The practice of hiring foreign workers has created a system in which certain nationalities are concentrated in particular jobs, and salaries differ depending on nationality. The broadest division is between citizens and foreigners, with subdivisions based on region of origin, genealogy, and cultural practices.

Despite this inequality, the atmosphere is one of comfortable and tolerant coresidence. Foreign workers retain their national dress. Their children can attend school with instruction in their native languages. Markets carry a broad range of international foods, music, and films. Foreigners are permitted to practice their religion publicly, and many expatriate religious institutions sponsor community activities and services.

Political Life

Government. Qatari is technically an "Emirate," ruled by an Emir. Since independence the country's rulers have been of one particular family, the Al Thani. The Emir and many of the cabinet of ministers, as well as other high ranking officials are members of the Al Thani family (a large patrilineally related kin group) and are overwhelmingly male. However, some high level appointments have been made outside of the ruling family. Because of the concentration of power within the Al Thani, divisions or disputes among members of this large kin group will influence political relations. In 1998, Qatar held open elections for a "municipal council." This was the first election ever held in Qatar, and the campaigning was not only lively but drew in large portions of Qatar's citizenry. While a number of women ran for office, none were elected in this first vote. Both women and men turned out to vote for representatives from their residential sectors. The Municipal Council represents local residential sectors to other governmental bodies.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

After independence, Qatar developed extensive social welfare programs, including free health care, education through university, housing grants, and subsidized utilities. Improvements in utility services, road networks, sewage treatment, and water desalination have resulted in a better quality of life. In recent years, institutions have been established to support low-income families and disabled individuals through educational and job training programs.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

A number of international NGO's have offices and operations in Qatar, such as UNESCO, UNICEF, and the Red Crescent Society. Since 1995, the Emir's wife Shaikh Mouza, has been instrumental in encouraging and facilitating the establishment of organizations to serve women, children, family and the disabled. These service organizations have made significant headway particularly in the areas of health and education.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Schooling is gender-segregated. After completing schooling, men and women can obtain employment in government agencies or private enterprise. Qatari women tend to take government jobs, particularly in the ministries of education, health, and social affairs. High-level positions are held predominantly by men. While the presence of the foreign workforce has put more women in the public sphere, those women work primarily in occupations that reinforce the division of labor by gender. Foreign females are hired mostly as maids, nannies, teachers, nurses, and clerical or service workers.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Gender roles are relatively distinct. Men engage in the public sphere more frequently than do women. Women have access to schooling and employment and have the right to drive and travel outside the country. However, social mores influenced by Islam and historical precedent leave many women uncomfortable among strangers in public. Instead, their activities are conducted in private spaces. To provide women with more access to public services, some department stores, malls, parks, and museums designate "family days" during which men are allowed entry only if they accompany their families.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Most marriages are arranged. Usually the mother and sisters of the groom make initial inquiries about prospective brides, discuss the possibilities with the young man, and, if he is interested, approach the family of the prospective bride. That woman has the opportunity to accept or refuse the proposal. Marriages often are arranged between families with similar backgrounds, and it is common for several members of two lineages to be married to each other. Marriages between Qataris and other Gulf Arabs are common, but the government discourages marriage to non-Gulf citizens. One must get official permission to marry a noncitizen, and the citizen may have to give up the promise of government employment and other benefits.

Polygyny is religiously and legally sanctioned. While it remains common among the ruling family, the number of polygynous marriages has dropped in recent years. A wife can divorce her husband if he takes another wife, and with more education and economic options, women are more likely to do that now than they were in the past. Another reason for the decrease in polygyny may be the rising cost of maintaining more than one household.

The divorce rate has risen sharply since 1980. Both women and men may seek a divorce, and custody is granted in accordance with Islamic law. Young children are kept with the mother; once they reach adolescence, custody reverts to the father.

Domestic Unit. Extended, joint, and nuclear households are all found today. The preference is to live with or at least near the members of the husband's family. This patrilineal proximity is accomplished by means of a single extended household, walled family compounds with separate houses, or simply living in the same neighborhood.

Kin Groups. "Family" in Qatar refers to a group larger than the domestic unit. Descent is reckoned through the male line, and so one is a member of his or her father's lineage and maintains close ties to that lineage. After marriage, women remain members of the father's lineage but are partially integrated into the lineages of their husbands and children. Children of polygynous marriages often identify most closely with siblings from the same mother. As children mature, such groups sometimes establish separate households or compounds.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Children are important in family life. If a marriage is barren, the couple may resort to medically-assisted conception, polygyny, or divorce. Child care is the province of adult females, although children have close ties to their male relatives as well. The employment of foreign nannies has introduced new child care practices and foreign influences.

Higher Education. Public schooling has been available since the 1950s. In 1973, a teacher's college was opened and in 1977 the colleges of Humanities and Social Sciences, Science, and Sharia and Islamic were added to form the University of Qatar. Subsequently the College of Engineering, College of Administrative Sciences and Economics, and the College of Technology were added to the original four. Qataris can attend kindergarten through university for free. Students who qualify for higher education abroad can obtain scholarships to offset the costs of tuition, travel, and living abroad.

Social behavior is conducted in a manner respectful of family privacy, hospitality, and the public separation of genders. Visits with unrelated persons occur outside the house or in designated guest areas separate from the areas regularly used by the family. One does not inquire unnecessarily about another person's family. Despite this strong sense of family privacy, it is considered rude not to extend hospitality to strangers. Tea, coffee, food, and a cool place to sit should be offered to any visitor. Conversely, it is rude not to accept hospitality. When greeting a member of the opposite sex, it is best to act with reserve, following the Qatari's lead. Some Qatari women feel comfortable shaking hands with a man, but others refrain. Similarly, men may refrain from extending the hand to women or sitting beside them.

Religious Beliefs. The majority of the citizens and the ruling family are Sunni Muslims, specifically Wahhabis. There is, however, a large minority of Shi'a Muslims. Recent events such as the Iranian Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War, and alleged discrimination against Shi'a Muslims have exacerbated sectarian tensions. These divisions are rarely discussed openly.

Bibliography

Crystal, Jill. Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar , 1990.

Ferdinand, Klaus. The Bedouins of Qatar , 1993.

Field, Michael. The Merchants: The Big Business Families of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States , 1985.

Grill, N. C. Urbanisation in the Arabian Peninsula , 1984.

Kanafani, Aida. Aesthetics and Ritual in the United Arab Emirates , 1983.

Kay, Sandra, and Dariush Zandi. Architectural Heritage of the Gulf , 1991.

Lawless, R. I. The Gulf in the Early 20th Century: Foreign Institutions and Local Responses , 1986.

Lorimer, J. G. Gazetter of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia , 1970 [1915].

Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. Persian Gulf States: Country Studies , 1993.

Montigny-Kozlowska, A. "Les lieux de l'identite des Al-Na'im de Qatar." Maghreb-Machrek 123: 132–143, 1989.

——. "Les Determinates d'un fait de la notion de territorie et son evolution chez les Al-Naim de Qatar." Production Pastorale et Societe 13:111–113, 1983.

Nagy, Sharon. "Social Diversity and Changes in the Form and Appearance of the Qatari House." Visual Anthropology 10:281–304, 1997.

——. Social and Spatial Process: An Ethnographic Study of Housing in Qatar , 1997.

Palgrave, B. W. Personal Narrative of a Year's Journey through Central and Eastern Arabia , 1868.

Peck, Malcolm. Historical Dictionary of the Gulf Arab States , 1997.

Schofield, R., and G. Blake, eds. Arabian Boundaries Primary Documents .

Zahlan, Rosemarie. The Creation of Qatar , 1979.

—S HARON N AGY

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

We've updated our privacy policy. Please read here

The Economist Intelligence Unit

This website is no longer live. For all your latest EIU content and data, please log in to EIU Viewpoint here

Attend a live demo of the new website, and learn where to find insights and data. Register for a EIU Viewpoint showcase here .

Need assistance? Contact EIU customer services.

email: [email protected]

London: +44 (0) 20 7576 8181 | New York + 1 212 698 9717 | Hong Kong + 852 2802 7288

EIU expects the emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, to remain secure in office, supported by strong public backing (helped by a generous social contract with Qataris) and his handling of regional challenges, including rebuilding of relations with the Gulf countries and Egypt. We expect the elected Advisory Council to remain loyal to the emir. The Qatar National Vision 2030, which forms the centrepiece of the government's strategy to develop and diversify the economy and to advance environmental management and social development, will shape policy in 2024-28. The long-term plan is to generate a favourable business environment to support higher investment and employment. Occasional riyal volatility might occur on the offshore market, but the ample reserves of the Qatar Investment Authority (the sovereign wealth fund) mean that the Qatar Central Bank will be able to easily defend the peg to the US dollar throughout 2024-28.

Read more: What to watch in 2024: Qatar

Read more: Qatar Energy accelerates its international expansion drive

Featured analysis

Gulf co-operation council's expanding african footprint, does an improving business environment boost gdp, qatar and france set to bolster bilateral relations, economic growth.

| (% unless otherwise indicated) | |||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US GDP | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| Developed economies GDP | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| World GDP | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| World trade | -0.9 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit | |||

Expenditure on GDP

Forecast updates

Oil prices will remain above us$80/b until late 2025, qatar pauses liquefied natural gas shipments via red sea, qatari defence procurements emphasise naval capabilities, quick links.

- Forecast summary

- Market outlook

Origin of GDP

28 Interesting Facts About Qatar to Spark Your Curiosity

Destguides may receive commissions from purchases made through affiliate links in this article.

One of the smallest but mightiest countries in the Persian Gulf, Qatar is a country full of many interesting facts and exciting things to see and do. It is one of the wealthiest countries in the world and was the first Arab country to host the FIFA World Cup in 2022.

From the history behind the Qatari flag to a giant teddy bear housed at the country's main international airport, you will find some very interesting facts about Qatar down below. These Qatar facts just might intrigue you enough to make you think about visiting this luxurious and rich country soon!

28 Interesting Qatar Facts

Qatar is the safest country in the world, machboos is the national dish of qatar, qatar airways is the best airline in the world, a giant teddy bear lives at hamad international airport, hamad international airport is the third best airport in the world, there are no forests in qatar, qatar is the second flattest country in the world, it is a country where the sea meets the desert, qatar will be the first arab country to host the fifa world cup, it is the first country that made purple shellfish dye, the national animal is the arabian oryx, qatar has very cheap gas, it has the longest drilled oil well in the world, qatar's flag is very unique and holds great significance, men outnumber women 3 to 1 in qatar, only 12 percent of the population are qataris, 99% of the qatari population lives in doha, the capital city, the doha tower has no central core, the country name dates back to 50 ad, qatar's national day wasn't always celebrated on the same day, the weekend falls on fridays and saturdays, doha has the longest continuous cycle path in the world, they are obsessed with falcons, qatar has a beautiful string of pearls, the ruling family has been in power since 1868, they love to use robots for camel racing, you can eat your heart out at a 100-meter-long buffet, qatar owns a lot of properties in london, england.

Chevron Circle Down Show all

One fun fact about Qatar is that it was ranked as the safest country in the world for the third time in 2020. Previously, this accolade was given to Qatar in 2017 and again in 2019.

This fact comes from the Numbeo Crime Index , in which Qatar had the lowest score globally. It is one of the main reasons why a lot of tourists and ex-pats are attracted to Qatar. Surely, this is something to be proud of, don't you think?

One of the most fun facts about Qatar is that it has a delicious meal called Machboos as its national dish. This dish is incredibly popular amongst both locals and tourists.

Many restaurants around the country serve Machboos. When you're in Qatar, it would definitely be a very wise decision to try it. The dish is made of rice, meat, onions, and tomatoes, mixed with spices, and is sure to leave you wanting more.

Qatar Airways, the national airline of Qatar, has been named the best airline in the world for three consecutive years. It operates domestic flights as well as international flights to all seven continents.

It is the only airline that takes passengers to countries on all of the continents. At one point, Qatar airlines had the longest scheduled flight in the world, which was between Doha and Auckland. It took 16 hours and 30 minutes to complete.

When you come to Qatar on its national airline, you will experience luxury and comfort like nowhere else.

One of the first interesting things you will see when you arrive in Doha, Qatar, is a giant teddy bear in the main terminal building of the airport. The teddy bear has a lamp on its head and sits proudly in the Hamad International Airport.

The giant artwork has been reported to cost $6.8 million and weighs almost 20 tonnes. It is sure to catch your eye and has become a very popular picture destination for tourists.

Qatar's main airport, the Hamad International Airport, has been ranked as the third-best airport in the world . It is also the best airport in the whole of the Middle East.

Hamad Airport is located in the capital of Qatar, Doha, and serves as the first impression of Qatar for many tourists visiting the country.

The airport is known for making journeys smoother and offering loads of entertainment. It also has the longest runway in western Asia, which is the 6th longest in the world.

Now, this fun fact about Qatar shouldn't be the most surprising to you. Pretty much all of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates is a desert landscape with very few forests and greenery. Most of the trees and green landscapes are human-made.

Qatar is one of the only four territories in the world where there are no forests . They do have some greenery, but a forest is something that you will never see in the country. There are a lot of stunning sand landscapes that you can still enjoy, though!

If you love to hike, Qatar may not be the country for you. It is the second flattest country in the world , behind the Maldives. It has an average elevation of 91.9 feet, with the highest elevation at about 338 feet.

When you visit Qatar, you won't be seeing any rolling hills or cliffs. You will instead have to rely on skyscrapers to give you a sense of the grandeur of the place. The country is full of flat expanses, though, and those are pretty amazing to look at as well.

One of the more interesting facts of Qatar is that it is one of the few places in the world where the sea meets the desert. While the expansive sand dunes in the country are a sight to behold themselves, Khor Al-Adaid is a different story altogether.

The area was declared a natural reserve in 2007 and is also known as the Inland Sea. There is a thriving ecology in the area, with some endangered marine species and grazing camels around. Khor Al Adaid has different cultural and archaeological sites to explore as well.

One of the most exciting events in the world of football is the FIFA World Cup . Countries worldwide hope to be the next ones to host it, and in 2022, Qatar will be the first Arab country to hold this major sporting event.

Not only that, but it will also be the smallest country ever to host it and the only one to hold it in the wintertime. Furthermore, it will be the first-ever carbon neutral World Cup. Qatar has invested in this event heavily, and it promises to be a great World Cup when the time comes.

One of the most interesting facts on Qatar is that the country is known for being the first to make purple dye out of shellfish. The inhabitants of Al Khor Island hold this honor.

Al Khor Island is one of the most beautiful and popular tourist destinations in Qatar. There have been discoveries of items from the second millennium BC, and the island is called the Purple Island due to the dye production that happens here.

If you have ever seen the Qatar airlines logo or the mascot for the 2006 Asian Games, you will have seen the Arabian Oryx being represented as the national animal of Qatar.

This beautiful animal was saved from extinction in the 1970s by different zoos and reserves. It is an antelope with a long straight horn and a tasseled tail. Wherever you go in Qatar, you are bound to come across images of their national animal.

Qatar is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, and most of that wealth comes from petroleum and natural gas. The exports of these two things account for 60 percent of their GDP, and there are many perks that the people of Qatar enjoy because of this.

One of the best perks is the cheap petrol . Qataris enjoy very low prices on their petrol and don't have to splash out a lot of cash to fill up their tanks. In fact, you would probably find that filling up your tank in Qatar is cheaper than enjoying a few lattes at Starbucks.

Most of the countries in the UAE are understood to have oil wells, as that is how they tend to make their money. Qatar is no different, but a fun fact about Qatar is that it has the longest drilled oil well in the world.

The oil well is named BD-04-A and has a total length of 40,320 ft MDRT. It is located in the Al-Shaheen offshore oil field off the coast of Qatar. The oil well also holds a Guinness World Record , cementing its place as the longest in the world.

You will notice in Qatar that their flag is displayed almost everywhere, no matter where you are. The flag is nice to look at, but it also has a lot of significance.

The nine serrated edges represent the inclusion of Qatar as the ninth member of the reconciled Emirates under a treaty that was signed with the British in 1916.

The maroon color is called Qatar maroon, or Pantone 1955 C, which represents the purple dye industry on Al Khor Island. The flag is unique as it is the only flag in the world twice as wide as it is high.

Here's a fun fact! When you're in Qatar, you will notice that there are many more men than women around. According to the most recent census in September 2020, there are three men for every one woman in Qatar .

The population of women is just 754,592 out of the whole population of 2,723,624. Qatar is, in fact, a country that has the highest male-to-female ratio in the world.

One of the most well-known facts about Qatar is that it is immensely popular with ex-pats. Many people move to the country to take advantage of the great weather, the laidback lifestyle, and the tax-free salaries.

Qatar is so popular with ex-pats that there are about two million of them living in the country. This figure means that Qataris themselves have now become the minority. At just 12 percent of the total population, Qatar has become a melting pot of different cultures and traditions.

You've already learned that the Qatari population is the minority, but another amazing fact about Qatar is that most of this population lives in the capital city, Doha. Around 99%, to be exact!

This is partly because most of the country is desert and cannot sustain too much life. The other part is that almost all the Qataris are filthy rich and can afford to live in the capital. The rest of them, well, wouldn't you love to meet them and hear their stories? I know I would!

One of the best things that tourists and locals alike love to look at is the Doha skyline. During the day, it looks commanding, and at night, it's lit up and stunning. Among the structures on the West Bay, there is the Doha Tower.

The Doha Tower is a structure that was designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel . It was named the best tall building in 2012. The 46-story tower has several unique features.

The building has no central core and is the first skyscraper in the world to use internal reinforced concrete diagrid columns. The façade is a nod to the ancient Islamic design, Mashrabiya, and it is just an incredible building to look at.

One of the more interesting Qatar facts has to do with the country's name. In the mid-first century, the Roman writer Pliny the Elder called the inhabitants of this area 'Catharrei'.

The name has gone through many iterations since then. Up until the 18th century, the name Catara was used until Katara became the more common spelling.

More variations followed and were quickly adopted as the common name up until Qatar officially became the country's name.

Qatar's National Day is celebrated on December 18, and it is a day of top deals and fantastic firework displays all around. But, a fun fact about Qatar is that this day wasn't always celebrated in December.

Before 2007, when it was officially changed, the National Day was celebrated on September 3. This was the day when Qatar gained independence from the British in 1971.

December 18 is when Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani unified the local tribes and succeeded his father as the ruler in 1878.

Throughout most of the Western world, there are five working days and two days for the weekend. Saturday and Sunday are the days we most associate with the weekend, right? Well, another fun fact about Qatar , their weekends fall on Fridays and Saturdays.

Most of the countries in the UAE don't have the standard weekends that the West knows of. In Islam, Friday is a blessed day, and so many of these countries, including Qatar, don't work on those days. The workweek starts from Sunday and goes up to Thursday.

The Olympic Cycling Track in Doha holds a Guinness World Record for having the longest continuous cycle path in the world. It was completed in 2020 and is 33 km long.

The cycling path has a variety of straight paths, underpasses, and overpasses, as well as 100 benches and 20 areas for resting. It was created by Ashghal, a Public Works Authority in the capital city of Qatar.

The track holds a record for the longest piece of asphalt concrete laid continuously as well, which measures 25.3 km. The network of cycling paths is a great way to spend the day in Qatar, exploring the different areas and being away from the busy roads of the capital.

One of the most interesting Qatar fun facts is that the Qataris love to hunt falcons and keep them as pets. There is even a dedicated market called the Falcon Souq where people can buy not only falcons, but also hunting materials such as hoods, leather gauntlets, and hunting pouches.

The sport of falconry is deemed an important sport in Qatar, and many Qataris actively take part in it in their spare time. When you're out in Qatar, don't forget to visit the Falcon Souq to get an idea of how seriously it is taken here.

In the olden days, before Qatar discovered its natural gas and oil reserves, the money used to come from pearls. The country was known for good pearls that could be found here, and they made money through diving for pearls for a long time.

To pay homage to that part of their history, Qatar has made an artificial island on top of one of the most famous pearl diving spots in the past. The string of islands is collectively known as The Pearl , and it is a beautiful island to visit.

Ruling families around the world have changed throughout history. A fun fact about Qatar, though is that their ruling family has stayed the same since 1868 when Mohammed Bin Thani signed a treaty with the British.

The House of Thani , as the royal family is known, is the most powerful family in Qatar. It has high amounts of political and economic influence. When you go to Qatar, you will see that the people are loyal to the ruling family and have enjoyed a prosperous life under them.

Another sport that is hugely popular in Qatar is camel racing . A fun fact about the camel races in Qatar is that they use robots for the jockeys. In the early days, children were used as jockeys, but after it was deemed too dangerous for kids, robots were brought in to take their place.

Since 2004, these robots have been acting as the jockeys. They are controlled by the camel herders remotely, and often these herders will drive alongside the track to have two different perspectives. It is a sight to see when in Qatar and will surely leave you amazed.

One of the most interesting yet random fun facts about Qatar is that it has a 100-meter long buffet. The Doha Marriott features this amazing buffet line where you can find every cuisine under the sun, from a full English breakfast to sushi and tacos.

Even if you feel like you can't sample all the dishes on display, you should just visit to marvel at the sheer size of the buffet when you're in Qatar. The Marriott hotel itself is a luxurious place to visit, and it only makes sense that they have this 100-meter buffet as well.

The last interesting fact about Qatar is indeed a very mind-boggling one. Qatar has many real estate investments around the world, but most of them are in London. The Qatari Royal Family's new home is also being built in London for an estimated $313 million.

The Mayor of London's office and the Queen own a lot of real estate in London, but Qatar tops them on this. The country possesses more than three times the properties that the Queen owns in London, making Qatar the biggest landlord in London.

I hope you enjoyed reading the amazing facts about Qatar above, which are sure to leave you curious enough to travel to the country now.

Qatar has unmatched luxury and decadence, and on your visit here, you will see quite a few things that stand out and make you appreciate the history and culture of the Qatari people.

This article was edited by Loredana Elena .

Feedback Give us feedback about this article

Written by Nawaal R. Khan

Nawaal_RK FORMER WRITER Currently based in Pakistan and working as a freelance writer, Nawaal has travelled all across the globe and enjoys learning about cultures, discovering hidden gems, and roaming the streets of beautiful cities.

Want to keep exploring?

Subscribe for our latest guides .

Thank you for subscribing

We will be in touch soon with our latest guides .

Related Articles

The State of Qatar.

Sep 01, 2014

1.86k likes | 4.22k Views

The State of Qatar. Katrina Camiling. 8B. Facts about Qatar. Location: a peninsula that lies upon the Persian Gulf. Populatio n: 928,635 people. Climate: pleasant winters and hot, and humid summers. Religion: 77.5% - Islam, 8.75 – Christianity, …

Share Presentation

- educational terms

- social terms

- economical terms

- al thani family

- qatar national football team

Presentation Transcript

The State of Qatar. Katrina Camiling. 8B.

Facts about Qatar. • Location:a peninsula that lies upon the Persian Gulf. • Population: 928,635 people. • Climate:pleasant winters and hot, and humid summers. • Religion: 77.5% - Islam, 8.75 – Christianity, … • Language:Arabic, and English is used as a 2nd language. • Time: GMT +3

Qatar’s History. • It is known that the first indications that there was life in Qatar all the way back to around 4000 B.C. was found by many archaeological journeys from different branches of Europeans. Those expeditions have shown old pottery and rock carvings. • Other indications is that Qatar used to appear on ancient maps and historical pieces of text have been found as well. • The historical texts were said to have come from the first inhabitants, the Canaanites.

Qatar’s History. (contd.) • The people of Qatar’s past grew and developed over centuries by trading, diving for pearls, and weaving different styles of cloths. • Qatari’s were ruled both by the Ottoman Empire and the British, but at separate times in history.

Qatar Now:Economical Terms • Qatar’s economy has been flourishing greatly over the past decades. • From pearl diving and tough lifestyles, Qatar’s economy is now built up of oil, petroleum and other industries. • Qatar is the home of the Al Jazeera Channel. The Al Jazeera Channel is a vastly popular and notorious Arabic satellite television network. • Qatar is aiming to become a role model for economic and transformation in the Middle Eastern region. This will hopefully improve Qatar’s position in the financial market.

Qatar Now:Economical Terms (contd.) • The Qatar Financial Centre is now one of the most sophisticated and moderns financial organizations in the world. • One large project that Qatar is dealing with now is the building and developing of the new town, Lusail.

Qatar Now:Social Terms • Qatar is a tolerant country but visitors will avoid giving offence if they observe a few courtesies, especially with regard to dress. • Cover knees and shoulders, except within hotel grounds where more casual clothing is acceptable. • At business and social functions, traditional Qatari coffee is served as part of the ritual welcome.

Qatar Now:Social Terms (contd.) • Qatar is a very hospitable country that welcomes all of its tourists, inhabitants and visitors. • Both law and Islamic customs closely restrict the activities of Qatari women, who are largely limited to roles within the home. Women are not allowed to obtain a driver's license without the permission of her husband. • However, growing numbers of woman are receiving government scholarships to study abroad, and some women work in education, medicine, and the media. • Women comprise two-thirds of the student body at Qatar University. • Although domestic violence occurs, it is not a widespread problem.

Qatar Now:Political Terms • Qatar is now ruled by H.H. Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani, who was put to power in 1995. • Qatar gained its independence when the British withdrew back in September 3rd 1971. • Qatar rules with a hereditary system – the Al Thani family (also a dynasty). • Along with the hereditary system, Qatar also contains an advisory council and many smaller councils and ministries.

Qatar Now:H.H. Sheikh Hamad • H.H. Sheikh Hamad is a very popular emir to his people because of his loyalty and kindness to his country. • He began his education in Qatar then continued his college years in Sandhurst Military Academy in England. • He tried his best to develop Qatar, and he has succeeded. • He is one of the many reasons of why Qatar is now one of the most developed countries in the Middle East.

Qatar Now:H.H. Sheikh Hamad (contd.) • H.H. Sheikh Hamad has been a very busy man over the past years. • He has been visiting many leaders and places abroad. He recently visited the residents in New Orleans that were victims of the Hurricane Katrina. • As a very keen sportsman and a man who encourages education, he has been doing his best to support this in Qatar.

Qatar Now:Educational Terms • Qatar has many educational centres and schools for people of all ages. • Probably one of the biggest of Qatar’s educational centres would have to be Qatar Foundation. • Qatar Foundation is headed by H.H. Sheikah Mozah. • It consists of American universities, Qatar Academy, and some other Qatari schools.

Qatar Now:Educational Terms (contd.) • Qatar offers many other schools for expats. • British schools are available like Doha College. • American schools are available as well such as the American School of Doha. • Interschool events are held on an annual basis for both students and staff.

Qatar Now: Sports • Football is probably the most popular game/sport in the state of Qatar. • The Qatar National Football team is the national team of Qatar and is controlled by the Qatar Football Association. • Qatar is divided up by its cities into different teams as well. Like Al Sadd, Al Gharaffa, Um Salal… • Yearly, there is one tournament where all teams play against each other which is called the Emir’s Cup.

Qatar Now: Football • World Cup record • 1930 to 1974 - Did not enter • 1978 to 2006 - Did not qualify • 2010 - Playing Third Stage • Asian Cup record • 1956 to 1972 - Did not enter • 1976 - Did not qualify • 1980 to 1992 - Round 1 • 1996 - Did not qualify • 2000 - Quarterfinals • 2004 to 2007 - Round 1 • 2011 - Qualified

Bibliography: • https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/qa.html • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qatar • http://www.everyculture.com/images/ctc_03_img0897.jpg • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Hamad_ibn_khalifa_n_bush.jpg • http://www.qf.org.qa/output/page301.asp

Bibliography:(contd.) • http://www.international.ucla.edu/cms/images/Khalifa-Al-Thani.jpg • http://www.education.gov.qa/images/los1.jpg • http://galen-frysinger.com/middle_east/qatar16.jpg • http://www.fullpassport.com/Trip2002/images3/jillpearl.jpg • http://www.ameinfo.com/gallery/images/qatar-1.jpg • http://www.football-wallpapers.com/wallpapers2/qatar_3_1024x768.jpg

- More by User

By. Qatar. Cadet. Newman. Area:. total: 11,437 sq km land: 11,437 sq km water: 0 sq km . Qatar is a peninsula. It is has 563 km of shoreline and 60 km of border line with Saudi Arabia. Which would mean that Qatar is not land locked. . Area Comparitive:.

708 views • 11 slides

QATAR. Qatar is mostly Desert. About 89.9 % of its land is all deserts. The most common animal you see in Qatar is Camels and desert animals such as snakes and tarantula’s.

1.47k views • 10 slides

State of the State

State of the State. Sarah Heath [email protected] General CTE Email [email protected]. CTE Career and Technical Education CCCS Colorado Community College System CACTE Colorado Association for CTE (state affiliate of ACTE & we are region five). Match your CTE Content Area. Divisions.

458 views • 33 slides

State of Qatar: Introduction to Key Indicators and Regulatory System

State of Qatar: Introduction to Key Indicators and Regulatory System . Dr. Ali Al Amari Sr. Director Supervision, Authorization &AML. IFN Asia Forum: Kuala Lumpur, October 2011 . Major Points. Key Indicators Regulatory System In the State of Qatar. Introduction QFCRA,QCB,QFMA and MBT

477 views • 26 slides

Strategy for the Dissemination of 2010 Census Results for State of Qatar

Strategy for the Dissemination of 2010 Census Results for State of Qatar. Dr. Ahmed Hussein Mark Grice Pervaiz Ahmad Malik. Contents. Why 2010 Census is Important for Qatar Strategy Vision Strategy Aims Who are the Users Uses Utilization Framework Products Analysis Services.

406 views • 28 slides

The State of the State of NC

The State of the State of NC. Presented by: Lindsey Fults ESL/Title III Consultant. Objectives. Overview Demographics WIDA English Language Development Standards DPI Initiatives For ELLs SIOP ExC -ELL LinguaFolio. LEP Students in NC. LEP Students in NC. 300 Languages

642 views • 51 slides

State of the State. APIC Meeting January 25, 2013. Agenda. 1:35 – 1:45 pm Introduction and MEDSIS – Shoana/Sara 1:45 – 1:55 pm Vaccine Preventable Disease – Karman Tam 1:55 – 2:05 pm Cocci –Clarisse Tsang 2:05 – 2:15 pm Flu – Shane Brady

1.84k views • 167 slides

State of the State. Sue Murphy Chief Executive Officer February 2011. Presentation to WSAA members meeting. Winter 2010. Water for the Pilbara. Western Australia. Newman BHP WTP, BHP expansion, Shire WWTP. East Pilbara Port Hedland / South Hedland

242 views • 14 slides

State of the State. Ann Robbins HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch August 6, 2012. National HIV/AIDS Strategy. Reduc ing new HIV infections Increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for people living with HIV Reducing HIV-related health disparities

331 views • 21 slides

The State of the State of NC. Presented by: Ivanna Mann Thrower Anderson ESL/Title III Consultant. Presentation Overview. ESL Wiki State Led Initiatives RtI and ELLs Common Core & ELL Federal Update Q&A. NC Demographics WIDA Consortium ACCESS for ELLs RttT /Standard 6

354 views • 22 slides

State of the State. Global California Online with the World Conference April 25, 2008. Chantal Ramsay, Consul. Ontario and California. A strong and productive relationship already exists: The Governor visited in May 2007 and the Premier will visit later this year

212 views • 8 slides

Management of Coastal Aquifers The Case of a Peninsula State of Qatar

20th Salt Water Intrusion Meeting Naples, 23 - 27 June 2008. Dr. Kamel M. Amer Mr. Abdul A. Aziz Al Muraikhi Dept. of Agri. & Water Research Ministry of Municipal Affairs & Agriculture State of Qatar Nauman Rashid Schlumberger Water Services Middle East & Asia.

337 views • 15 slides

State of the State. Kathleen Wayne, MS RD Family Nutrition Program Manager. FNP Program Vision. Vision: To support Alaskan Families in making nutrition decisions for life-long Health and Wellbeing. 06 Initiatives & Accomplishments. Progress in AKWIC Reports Vendor Management

150 views • 7 slides

State of the State. Filing Stats, Budgetary Issues, Reimbursements, Mileage Caps, & Donated Funds. Thank you for all that you do. It was a great, if challenging, tax season, with good results. Our program could not succeed without the leadership you provide. 2011 Tax Season.

314 views • 18 slides

Communities of Qatar Academy

Communities of Qatar Academy. By: Ghaida Odah, Omar Al-Mulla and Rawda Al-Thani 8C. What Is A Community?. A community is a group that consists of more than one person that share an interest.

190 views • 10 slides

MERS from Middle East to Europe & Tunisia (as of 8 June 2013). Qatar. Lucey D.R., A.G.

181 views • 1 slides

State of the State. Stuart Bernstein Associate Professor, UNL, COE Affiliate Director, Nebraska. 2011 - Year in Review. New Schools Millard Public Schools, Reg. 2010, Std. 2011 Kearney High School, Reg. 2010, Started 2011 Papillion-LaVista School District, Reg. 2011, Std. 2012

271 views • 17 slides

Qatar. Authored by: Ben Connolly Illustrated By: Google Images. What is Qatar?. Qatar is a country just outside Saudi Arabia and is near Iraq. its the only country in the world that starts with a q. What makes Qatar famous?

398 views • 5 slides

The State of the State

The State of the State. A “State of the State” speech by the “Governor” of Texas in 1860. INTRODUCTION. The state Constitution of Texas requires that the governor give a speech at the beginning of each legislative session. This speech is called the “State of the State” address.

327 views • 10 slides

Qatar is an independent country in the Arab region. The country is known for its rich economy, its history and importantly its tourist destinations. Millions of people from all over the world come to Qatar to experience this beauty of Qatar. Also a lot of Qatar residents move from Qatar to other countries. Qatar police clearance certificate is one the documents that need to be submitted before any foreign government when you are migrating from Qatar.

86 views • 2 slides

305 views • 28 slides

Explore the Attractions of Qatar with the Best Tour Operator in Qatar

Qatar is an Islamic country and a great spot for the tourists if you are intended to spend a few days. This place is blessed with the best climatic features and many historical and cultural monuments.

73 views • 4 slides

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Let’s learn about Qatar

Published by Finn Ibsen Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Let’s learn about Qatar"— Presentation transcript:

Physical Geography Of Southwest Asia.

The Arabian Peninsula Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain.

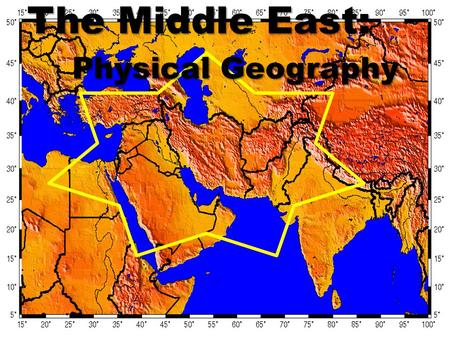

The Middle East: Physical Geography Israel Jordan Lebanon Syria Turkey Iraq Saudi Arabia Yemen Oman UAE Qatar.

The Arabian Peninsula Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Yemen.

The Arabian Peninsula and Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan Chapter 16-4 Chapter 16-5.

Jordan By: Lilian Nahas 6 th Grade Mrs. Emily. General Information General Information o Where is Jordan? Jordan, a Middle Eastern kingdom, is sandwiched.

All about Qatar in minutes By Sama Galib 6 th grade Ms. Emily.

By: Liam Fitzgerald Tamarac High School, 9 th Grade RPI EcoEd Research Project Spring 2013 “The Good, The Bad, and The Environmentally Ugly”

By: Liam Fitzgerald Tamarac High School, 9 th Grade RPI EcoEd Research Project Spring 2013.

GEOGRAPHY & THE MIDDLE EAST

A society is like a puzzle, it is made of different pieces. Those pieces are: Economics Government Varieties of religions Education Recreation and play.

Contents Introduction Geography History Religions Famous Monuments Music in India.

Saudi Arabia Capital City: Riyadh Population: 26.6 million Languages: Arabic and English Religions: Sunni Muslim and Shi’te Muslim.

Kuwait By Grant Johnson. Geography 17,820 sq kilometers 6,880 sq miles It is about the size of New Jersey. The capital is Kuwait City. It is entirely.

The Geography of the Middle East.

Leah Stanisz 5/6 The flag of Oman Leah Stanisz Block 5/6.

Are YOU ready? Middle East Test Review. Why is fresh water such a valuable resource to the people living in the Middle East?

Saudi Arabia facts…… In 1985 prince Sultan Ibn Salman became the first Arab and first Muslim to travel into space. Saudi women are forbidden to drive.

SOUTH ASIA Economy People & Environment Sherpa Family in Nepal Traditional Bengali Man & woman in Sari. Pakistani Women Indian Women Indian Men Sri Lankan.

CHAPTER 23 SECTION 4 Arabian Peninsula. I can explain how the discovery of oil changed the Arabian Peninsula. I can describe how Saudi Arabia has tried.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Global Insights

Qatar: Introduction

Qatar is a country in the Middle East occupying the Qatar Peninsula on the larger Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf. Much of the country is desert. The government system is an emirate; the chief of state is the amir or sheikh and the head of government is the prime minister. Qatar is a member of the League of Arab States (Arab League) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

Country Comparator

Select variable and countries to compare in table format.

Country Rankings

Rank ordering and interactive map. Show how this country compares to others.

From the Blog rss_feed

A Look into the Advertising Business of the 2022 World Cup

10/26/2022 10:00:17 AM

The 2022 World Cup - Should We be Spending This Much?

10/24/2022 10:00:09 AM

More Blog Entries

Quick Links

Qatar: U.S. Commercial Service - Country Commercial Guide open_in_new

Qatar: World Bank - Doing Business Indicators open_in_new

Qatar: BBC - Country Profile open_in_new

Qatar: U.S. Department of State - Country Travel Information open_in_new

Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies

- Download PDF (English) XML (English)

- Alt. Display

Research Article

Presentation of qatari identity at national museum of qatar: between imagination and reality.

- Mariam I. Al-Hammadi

This article discusses the proposal of the presentation of a single homogenous identity at the new National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ), due to open in 2019, presenting a discussion of Qatari identity and the historical factors that create such an identity. The article raises a series of questions for the theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of presentation of the Qatari identity, such as which form of Qatari identity should be presented at NMoQ: a single homogenous identity, or the diversity that exists within the national population? If the Museum’s presentation focused on a single identity, how far would such a presentation be accepted and perceived by the Qatari public? This paper also considers the impact of the current political crisis, the blockade against Qatar by some of its neighbours and the severing of diplomatic relationships, which has resulted in Qatari citizens coming together in a show of unity.

- National Identity

- National Museum of Qatar

- Blockade of Qatar

- Social Structure

Introduction

Recently, national museums have mushroomed in the Arabian Gulf to become a regional phenomenon. Evident within this phenomenon is the intention of the Arabian Gulf countries to exhibit their national identities, a challenging process in terms of representing the diverse national communities; such a focus reflects the important roles that museums play in the politics of culture. In the Arabian Gulf, museums are principally founded and financed by the state, which makes the state the main architect and policy-maker of the museums’ ideologies. States in the Gulf refer precisely to the power and interest of the ruling families; therefore, the ruling family in Qatar has full sovereignty and ultimate authority over museums and national cultural representation policies. Cultural representation and museums in Qatar thus follow the ruling family’s interests, who initiate policies that support them by connecting loyalty to the state with loyalty to the ruling family. This is the case especially if we consider that since its establishment in 2005, the head of the Museums Authority in Qatar has been HE Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the sister of the current Emir. Furthermore, the organisation of Qatar Museums is supervised directly by the Emiri Diwan, the seat of Government, which is unlike other organisations in Qatar.

This article discusses the concept and challenges of presenting a single Qatari identity within the forthcoming National Museum of Qatar, due to open in 2019, a concept that assumes that Qataris traditionally lived a dual lifestyle as one people, moving seasonally between the sea and desert. This single-identity concept and its assumed presentation at the National Museum was first developed by a political scientist based in Qatar, Jocelyn Sage-Mitchell, in a paper entitled ‘We’re all Qataris here: the Nation-Building Narrative of the National Museum of Qatar’ ( 2016 ), and has been subsequently discussed at academic workshops; the National Museum itself has not disclosed its approach to the narrative of Qatari identity. Therefore, this paper considers whether such a theoretical presentation of identity is a good fit for the complex reality of Qatari identity, and what might the challenges be if the National Museum followed this approach.

The National Museum of Qatar

Since 2007, the Qatar National Museum has been under undergoing redevelopment as the new National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ), designed by the French architect, Jean Nouvel. The NMoQ project is scheduled to open in April 2019 with a series of galleries representing different aspects of Qatar’s history and heritage. The Museum is the vision of the Father Emir, HH Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani and his daughter, the Chairperson of the Qatar Museums, HE Sheikha Al Mayassa. The new architecture is built around the historic palace of the previous ruler, Sheikh Abdulla bin Jassim Al Thani (1913–1948), which also housed the old Qatar National Museum (1975–2007) in a renovation that won the Agha Khan Prize for Architecture. The palace has political significance as the place from where Sheikh Abdulla ruled the country during the presence of two political competitors in the region: the Ottomans and the British. Through its programmes, exhibitions, media and publications, the first Qatar National Museum strived to develop experiences that showcased Qatari communities, identities, heritage and culture, distinguishing Bedouin and Hadar , two distinct forms of Qatari identity connected to life on the coast ( Hadar ) and life in the desert ( Bedouin ). The museum was developed to interpret Qatar’s history through objects and archaeology. The first section included the Old Emiri Palace, and consisted of nine buildings which presented the material culture of Hadar , including everyday objects, jewellery, domestic interior and decoration, costumes and traditional architecture. In addition to that, the Old Emiri Palace displayed and presented the history of the royal family and their personal objects, as well as their diplomatic relationships, especially with the British during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second section was a new building called the Museum of the State that presented the chronological development of Qatar from pre-history to the discovery of oil in the mid-twentieth century, and included archaeology, Islamic history, natural history, geology, oil and the material culture of the Bedouin . The third section was the Marine section, added in 1977, that included an aquarium and the historic pearling industry, representing the longstanding relationship between Qatar and the sea. This continued in the fourth section, the Lagoon, a natural extension of the sea which was used to exhibit different types of historic dhows and boats used by Hadar in their pearl fishing and trading. The fifth section was the Garden, which was built for scientific as well as aesthetic purposes. The Garden contained all kinds of desert plants, especially those of economic importance, such as palm trees, medicinal plants and plants protecting the desert soil from the creeping sand dunes ( Exell 2016 ; Al-Mulla 2013 ; Al-Khulaifi 1990 ; Al-Far 1979 ).