- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2023

The management of healthcare employees’ job satisfaction: optimization analyses from a series of large-scale surveys

- Paola Cantarelli 1 ,

- Milena Vainieri 1 &

- Chiara Seghieri 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 428 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4372 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Measuring employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and working environment have become increasingly common worldwide. Healthcare organizations are not extraneous to the irreversible trend of measuring employee perceptions to boost performance and improve service provision. Considering the multiplicity of aspects associated with job satisfaction, it is important to provide managers with a method for assessing which elements may carry key relevance. Our study identifies the mix of factors that are associated with an improvement of public healthcare professionals’ job satisfaction related to unit, organization, and regional government. Investigating employees’ satisfaction and perception about organizational climate with different governance level seems essential in light of extant evidence showing the interconnection as well as the uniqueness of each governance layer in enhancing or threatening motivation and satisfaction.

This study investigates the correlates of job satisfaction among 73,441 employees in healthcare regional governments in Italy. Across four cross sectional surveys in different healthcare systems, we use an optimization model to identify the most efficient combination of factors that is associated with an increase in employees’ satisfaction at three levels, namely one’s unit, organization, and regional healthcare system.

Findings show that environmental characteristics, organizational management practices, and team coordination mechanisms correlates with professionals’ satisfaction. Optimization analyses reveal that improving the planning of activities and tasks in the unit, a sense of being part of a team, and supervisor’s managerial competences correlate with a higher satisfaction to work for one’s unit. Improving how managers do their job tend to be associated with more satisfaction to work for the organization.

Conclusions

The study unveils commonalities and differences of personnel administration and management across public healthcare systems and provides insights on the role that several layers of governance have in depicting human resource management strategies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Measuring employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and working environment have become increasingly common worldwide among government and public organizations across fields, including healthcare [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Designing personnel policies that fit workers’ perceptions turned out to be uncontroversially relevant. Even more so during challenging times such as those generated by budget cuts and increased demands for public service provision [ 1 ] or caused by health and economic emergencies such as the COVID-19 outbreak [ 5 ]. The Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey administered by the United States Office of Personnel Management to federal civil servants is just the most famous example of how organizations can monitor workers’ attitudes and perceptions to manage human capital effectively [ 6 , 7 ]. Among the OECD governments administering surveys to their employees, the most common focus is on job satisfaction. Indeed, the number of countries that center the items of questionnaires on employees’ satisfaction is larger than those centering on work-life balance, employee motivation, or management effectiveness [ 1 ].

Public healthcare organizations are not extraneous to the irreversible trend of measuring employee perceptions to boost performance and improve service provision [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Indeed, asking employees to express their opinion on the work environment in which they operate daily to provide social and health services to citizens make them involved in the management and planning of activities. At the same time, employees’ feedback become a valuable resource for organizational management and an important tool to initiate targeted, efficient and effective improvement processes based on staff needs and expectations. Considering the multiplicity of aspects associated with job satisfaction, it is important to provide management with a method for assessing which elements it may be useful to focus on.

Our study is dedicated to identifying the mix of factors that are associated with an improvement of health professionals’ job satisfaction related to unit, organization, and regional government in the context of a series of large-scale surveys. Investigating employees’ satisfaction and perception about organizational climate with different governance levels seems essential in light of extant evidence showing the interconnection as well as the uniqueness of each governance layer in enhancing or threatening motivation and satisfaction across public administration fields, including government [ 12 , 13 ] and healthcare [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Our work provides several contributions to existing knowledge on the correlates of job satisfaction among civil servants in health organizations. Our findings may prove useful to scholars and practitioners alike. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first that employs optimization models for this purpose. In doing so, we espouse recent invitations to develop research projects that are context-sensitive and practical so to be able to develop middle range theories because optimization analyses is primarily meant to speak to managers and healthcare professionals [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Indeed, the main objective of the calculation of the optimization function is to provide some indications with a managerial value on the most efficient group of predictors – organizational variables – that can drive a preset level of improvement in job satisfaction so to close the science-practice gap in healthcare management work. In other words, the calculation provides a numerical information that shows how much organizational aspects weigh on the level of satisfaction. It was introduced for the first time in the field of health performance analysis by a group of researchers from the Ontario Ministry of Health in Canada [ 20 , 21 ] and subsequently used in the Italian context to analyze patient satisfaction emergency departments and nursing homes [ 22 , 23 ]. The use of optimization techniques in public administration is largely unexplored at the moment. Secondly, although unable to collect data across healthcare systems in the world, we account for common critiques about the external validity of findings in public administration research by combining large samples and survey replications in our research design [ 24 , 25 ]. Even in the country where the study is set, the number of respondents in our work is rather unique.

Job satisfaction in mission-driven organizations: a literature overview

Job satisfaction is one of the most investigated constructs by practitioners and scholars alike across disciplines such as health services [ 2 , 26 ], public administration [ 27 ] and applied psychology [ 28 , 29 ]. In the words of Hal Rainey [ 30 ], “thousands of studies and dozens of different questionnaire measures have made job satisfaction one of the most intensively studied variables in organizational research, if not the most studied” (p. 298).

Scholars across fields such as public administration, mainstream management, and psychology agree that work satisfaction construct includes facets related to the fulfillment of various and evolving individual needs and to the fit with numerous and changing organizational level variables [ 28 ]. Recent definitions by public administration and management scholars portray job satisfaction as an “affective or emotional response toward various components of one’s job” [ 31 ] (p. 246) or as “how an individual feels about his or her job and various aspects of it usually in the sense of how favorable – how positive or negative – those feelings are” [ 30 ] (p. 298). Previous definitions in mainstream management and applied psychology describe job satisfaction as “the feelings a worker has about his job” [ 32 ] (p. 100) or as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state, resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” [ 33 ] (p. 1304).

The breadth and depth of scholarship onto job satisfactions has nurtured efforts to synthesize and systematize available knowledge through meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews in recent years. For instance, Cantarelli and colleagues [ 27 ], collected quantitative information from primary studies published in 42 public administration and management journals since 1969 and performed a meta-analysis of the relationships between job satisfaction and 43 correlates, which span from mission valence, job design features, work motivation, person job-fit, and demographic characteristics. Furthermore, Vigan and Giauque [ 34 ] present results from a systematic review of the association between work environment attributes, personal characteristics, and work features on the job satisfaction of public employees in African countries. Then, meta-analytic findings show a positive correlation between job satisfaction and public service motivation [ 35 ] and pay satisfaction [ 36 ].

At the same time, novel studies on work satisfaction among employees across typologies of organizations do not seem to have come to an end. To the contrary, for example, observational work still investigate the individual and organizational correlates of employees’ satisfaction in public healthcare organizations [ 3 , 16 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] and government institutions more in general [ 7 , 43 , 44 ]. A similar interest pertains to employees’ preferences in experimental scholarship in public hospital [ 45 ] and public organizations [ 46 ].

Based on the evidence summarized above, we investigate the association between public employees’ job satisfaction to work for their unit, organization, and government system and variables that pertains to the following broad domains: workplace safety, human resource management practices at the team level, supervisors’ managerial capabilities, management practices at the organizational level, and training opportunities.

Building on such experiences as the Federal Employees Viewpoint Survey [ 47 ] and the NHS staff survey, several healthcare systems in Italian Regions administer organizational climate questionnaires to all employees on a routine basis thanks to their collaboration with the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy). Italy currently features a national health service with three main hierarchical levels. The first layer is that of the national health departments that define general strategies, laws, and regulations and set general targets. Regional governments, then, are the second hierarchical level. They are in charge of implementing such strategies and meeting such targets. The 21 Italian Regions are autonomous in this implementation phase. As a result, the variation in the governance structures and healthcare services is large among regional health systems. The third layer includes all organizations (i.e., local health authorities, hospitals, and teaching hospitals) that are at the front-line of health services provision to the population.

The decision to administer an organizational climate survey pertains to the regional government. Members of the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (authors included) design organizational climate surveys together with regional healthcare systems, which, at its core, are interested in using results for sustaining managerial change across the healthcare system. The rationale behind the analysis of region-wide data is multifaceted. First of all, the measurement instrument used in our study has been validated [ 48 , 49 ] and used in previous work [ 9 ] for data analysis at the regional and subsequently organizational level. Secondly, our presentation of results tends to score high on ecological validity because of the mechanisms that govern the provision of healthcare services in Italy where decisions taken at the regional level are binding for organizations within the region. Thirdly, the presentation of results by region resonates with well-established practices on the international stage. Just as an example, NHS staff results are presented at the national level also. As a consequence, our survey includes management variables—such as communication, information sharing, training, budget procedures – that tend to cross the borders of professions. The participation of healthcare employees to the questionnaire is voluntary and anonymous. The survey is composed of statements to which respondents indicate their level of agreement on a 1 to 5 Likert-type sale (1 means full disagreement and 5 full agreement). The questionnaire measures employees’ perceptions about their job, organization, management practices, communication and information sharing processes, training opportunities, budget system, and working conditions [ 9 , 50 ].

The outcome variables in this study relate to employees’ job satisfaction for three hierarchical levels, namely satisfaction with one’ unit, organization, and regional health service. These layers are key in the Italian healthcare system. In fact, all three levels hold levers that can be pulled to affect job satisfaction. In particular, we used the following statements:

I am satisfied to work in my unit.

I am proud to tell others that I work in this organization.

I am proud to work for the health service of my Region.

We regress each of these three outcome variables on the following list of correlates, which are survey items that tap into different theoretical domains and represent dimensions that can be modified through organizational change initiatives:

The equipment in my unit is adequate.

My workplace is safe (electrical systems, fire and emergency measures, etc.).

My workload is manageable.

Meetings are organized regularly in my unit.

Work is well planned in my unit and this allows us to achieve goals.

Periodically I am given feedback from my supervisor on the quality of my work and the results achieved.

My suggestions for improvement are considered by my supervisor.

I feel like I'm part of a team that works together to achieve common goals.

My supervisor knows how to handle conflict.

I agree with the criteria adopted by my supervisor to evaluate my work.

My supervisor is fair in managing subordinates.

I believe that my supervisor carries out his job well.

My organization encourages change and innovation.

The organization encourages information sharing.

My supervisor encourages information sharing.

I know annual organizational goals.

I know annual organizational accomplishments.

The training activities offered by my organizations are useful in enhancing my competences.

The training activities offered by my organizations are useful in improving my communication skills with colleagues.

I appreciate how managers manage the organization.

My organization stimulates me to give my best in my work.

I am motivated to achieve organizational goals.

In my organization, merit is a fundamental value.

In my organization, the professional contribution of everyone is adequately recognized.

Following the methodology of Brown and colleagues [ 20 ], the first phase for the calculation of the optimization function consists of an ordinal logistic regression in which satisfaction is predicted by the organizational variables of interest listed above. The second phase, then, combines the regression coefficients with the average values of the items of interest to identify, under certain pre-established mathematical constraints, the set of organizational variables that, with a certain improvement (always less than 15% for constraints required by the type of analysis) allows to reach a fixed level of overall satisfaction. Thus, optimization techniques allow the identification of the most efficient mix of predictors of employees’ satisfaction to help guide improvement efforts. An important information to consider when reading the results of these types of surveys is that improving the score of a variable that is very close to its benchmark is more difficult than that of a variable that is far from it. It is important to underline that the model is built on the average of the answers, so it does not refer to the strategies to be adopted in cases of falling perceptions related to the organizational climate. In other words, the model does not focus on ways to recover the satisfaction of particularly unsatisfied staff. As for the second phase of the statistical analysis, we used a 5 percent improvement of the job satisfaction outcome variables.

The two phases of analysis listed above have been repeated for each of the four Regions that are included in this study. Region A administered the organizational survey in April and May 2018, Region B in December 2018 and January 2019, Region C in March and April 2019, and Region D between mid-October and mid-December 2019. Respondents are 73,441 healthcare employees, of which 24,869 work in Region A; 5,078 in Region B; 21,272 in Region C; and 22,222 in Region D. The response rates are as follows: 28 percent for Region A, 27 percent for Region B, 39 percent for Region C, and 45 percent for Region D.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of respondents for each of the four healthcare systems included in our study. In all four cases separately, the average age of participants is not significantly different from the corresponding regional average of all healthcare professionals. Female professionals are slightly overrepresented in all regions compared to the national average of female healthcare professionals. The distribution of respondents across job families in each of the four samples is comparable to the national distribution of healthcare employees [ 51 ].

Table 2 displays the average job satisfaction, by regional healthcare system and by governance level – namely unit, organization, and Region – along with average standard deviation in parenthesis. Overall, the satisfaction to serve one’s organization is lower than the satisfaction to work for the unit and the regional healthcare system.

Table 3 presents the results of the logistic regression on the satisfaction to work for one’s unit across regional healthcare systems. In all regions, keeping everything else constant, professionals’ satisfaction to serve their unit is strongly and positively associated with the following constructs: adequate equipment, work safety, manageable workload, well-planned work, consideration of one’s improvement proposals, sense of being part of a team, agreement with the criteria for individual performance assessment, appreciation for the competences of one’s supervisor, organizational stimulation to give one’s best, and motivation to achieve organizational goals. All relationships are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. In Region A, coeteris paribus, training activities to enhance one’s competences and appreciation for how managers manage the organization are also positively related to job satisfaction at the unit level ( p < 0.001 and p = 0.001 , respectively). As for Region B, keeping everything else the same, supervisor’s fairness in managing subordinates and training opportunities are additional positive correlates ( p = 0.003 and p = 0.004 , respectively). In Region C, everything else equal, the following items also correlates positively with the outcome: supervisor’s fairness in managing subordinates ( p < 0.001 ), supervisors’ encouragement of information sharing ( p = 0.018 ), training opportunities to improve one’s skills ( p < 0.001 ), and appreciation for how managers manage the organization ( p = 0.033 ). Lastly, in Region D, everything else equal, the additional positive correlates of job satisfaction are the following: supervisor’s ability to fairly treat subordinates ( p < 0.001 ), training opportunity to improve professional competences ( p < 0.001 ), and appreciations for managers ( p < 0.001 ).

Table 4 sows the results of the optimization function, set for a 5 percent improvement in average value of the item “I am satisfied to work in my unit.” Predictions tend to be consistent across regional healthcare systems. In all regions, in fact, keeping everything else the same, the job satisfaction improvement at the unit level is associated with an improvement in the mean value of the following constructs: well-planned work in the team, perception of being part of a team that work towards shared goals, and perception that the supervisor can carry out the job well. More precisely, the percentages of improvement for these three correlates are as follows, respectively: 1, 15, and 12 for Region A, 1, 15, and 14 for Region B; 7, 15, and 13 for Region C; and 2, 15, and 13 for Region D.

Table 5 displays the logistic regression results for professionals’ satisfaction to work for their organization. In all regions, everything else equal, the positive correlates at the 0.05 or smaller significance level are the following: adequate equipment, workplace safety, sense of being part of a team, supervisor’ abilities to do a good job, training opportunities to enhance competences, appreciation for how managers manage the organization, organizational stimuli to give one’s best on the job, and motivation to achieve organizational goals. The relationship between the satisfaction to work for one’s organization and the degree to which one’s work is manageable is positive at the 0.05 significance level for all regions except Region A, everything else constant. Having a well-planned work is a significant correlate in Region D only ( p = 0.020 ), ceteris paribus. Participants’ perceptions that their suggestions for improvement are taken into consideration are significantly related to satisfaction in Regions A and B only, keeping everything else constant ( p = 0.001 and p = 0.043 respectively). Region C is the only that displays an association between the outcome of interest and respondents’ agreement with the criteria adopted to evaluate individual performance, ceteris paribus ( p = 0.025 ). Further, everything else equal, job satisfaction to work for one’s organization is positively associated with the degree to which the organization encourages change and innovation in Region A ( p < 0.001 ), in Region C ( p = 0.003 ), and Region D ( p < 0.001 ). Lastly, respondents in Region A and D show a significant association between the outcome and what supervisors do to encourage information sharing, everything else kept constant ( p = 0.041 , p = 0.038 , and p = 0.038 , respectively).

Table 6 presents the results of the optimization analysis for a 5 percent increase in the average value of the item “I am proud to tell others that I work in this organization.” Maintaining everything else constant, improving the mean of employees’ appreciation for how managers manage the organization is correlated to an enhanced job satisfaction at the organization level in all regions. In particular, the percentage improvement for the former statement are 12 percent for Region A, 9 percent for Region B, and 13 percent for all of the remaining regions. Furthermore, in Region B, ceteris paribus, a 9 percent percent improvement in the level of agreement with the statement that the organization stimulates employees to give their best on the job is related to the betterment of the outcome.

Table 7 displays estimates from a logistic regression model for public employees’ satisfaction to work for the health service of their regional government. Keeping everything else equal, across regions, the positive correlates at the 0.05 significance level are the following: workplace safety, supervisor’ adequate competences to carry out the job, effective training in improving one’s skills, appreciation for how managers run the organization, organizational stimuli to give one’s best on the job, and motivation to achieve organizational mission. Having an adequate equipment is positively associated with the satisfaction to work for the health care system at the standard statistical levels in all regions but C and D. The relationship between the satisfaction to work for one’s organization and the degree to which one’s work is manageable is positive at the 0.05 significance level for all regions except Region B, where the relationship is marginally significant ( p = 0.054 ). Employees’ perceptions that their suggestions for improvement are taken into consideration by their supervisors are significantly related to satisfaction in regions B, C, and D ( p = 0.009 , p = 0.008 , and p = 0.024 respectively). Region C is the only that displays a positive correlation between the satisfaction to serve the health systems and an agreement with the criteria adopted to evaluate individual performance, ceteris paribus ( p = 0.001 ). Regions C shows a positive correlation between information sharing at the organizational level and work satisfaction ( p = 0.003 ), whereas team-level information sharing is relevant in Region D ( p = 0.006 ). Then, awareness of the organizational goals is a relevant predictor of the satisfaction to work for the health service on one’s regional government in Region D ( p = 0.006 ).

Similarly, to Tables 3 and 6 , Table 8 displays the findings from an optimization algorithm aimed at improving the mean value of the satisfaction to work for the health service of one’s regional government by 5 percent. Improving positive perceptions about how managers run the organization and the motivation to achieve the organizational mission are correlated to an enhanced job satisfaction. In particular, the percentage improvement for the former statement are 11 percent for Region A, 7 percent for Region B, 13 percent for Region C, and 7 percent for Region D. As to the latter, the percentages are, respectively; 12, 15, 12, and 15. In Regions A and D, improving by 1 percent and 2 percent the mean value associated with the usefulness of training for competence enhancement are linked to a higher satisfaction. In Region B, instead, an improvement of the 6 percent of the organizational stimuli to give the best in one’s work correlated with an increased satisfaction. Lastly, improving personnel’s perceptions about workplace settings by 1 percent is associated with a higher satisfaction in Region B.

Overall, our analyses present three main key findings. First, within dependent variables, the correlates of job satisfaction tend to be the same across the health services of four regional governments. Second, the correlates of job satisfaction seem to differ among outcomes, namely hierarchical level at which employees’ satisfaction is measured. Third, context-specific associations emerge from our models.

Our work aimed at (i) investigating the correlates of health professionals’ job satisfaction at three hierarchical levels, namely satisfaction to work for one’s unit, organization, and health system of the regional government, and (ii) predicting how the improvement of the average value of correlates may relate with the improvement in the outcome variables. We employed large-scales observational surveys across healthcare systems in Italy. A series of logistic regressions reveal that environmental characteristics, management practices at the organizational level, and management practices at the team level correlates with work satisfaction. The pattern of results seems to replicate across outcome variables and healthcare systems. A series of optimization algorithms show that improving how the work is organized at the unit level, the degree to which employees perceive a sense of being part of a team with shared goals, and the supervisor’s abilities in carrying out the job may correlate with a better satisfaction to work for one’s unit. To the contrary, improving how managers perform their job tend to be associated with more satisfaction to work for one’s organization. As to the satisfaction to serve one’s regional health system, then, an improved work satisfaction correlates with an improved appreciation for the top management and the motivation to achieve the organizational mission.

The correlates that may relate to a higher job satisfaction are, therefore, in part different among hierarchical levels [ 2 , 18 , 52 ]. Within outcome variables, the largest variation in the correlates of job satisfaction is to the regional government level. Taken together, these findings align with two well established literature streams. On the one hand, attitudes and needs are so deeply seated in the human nature that they tend to be invariant for work satisfaction at the micro-level [ 8 , 43 ]. On the other hand, then, characteristics contingent to the macro-level may be relevant in prioritizing some attitudes and needs over others [ 6 , 9 , 16 ].

Further on the previous point, our work seems to suggest that all governance levels can play a role in employees’ job satisfaction, which continues to be a topic of interest for research syntheses attempts at the international level [ 53 , 54 , 55 ]. Some of the levers may overlap whereas other are different. As to the former, for instance, the quality and competence of managers at the unit and organizational level both correlated with work satisfaction. Thus, the mix of levers and the extent to which they are used may vary across regional healthcare system, which ultimately represent the highest governance level. Research on this consideration seems to have become even more prominent in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 56 ].

Our study may provide a few contributions to extant scholarship and practice on job satisfaction in public service. Firstly, we investigate the correlates of satisfaction at three hierarchical levels. To the best of our knowledge, while most research analyzed satisfaction using hierarchical models [ 9 ], they tend to focus on one level only. Secondly, our analyses tap into many correlates of job satisfaction. This has the potential to uncover unexpected associations. Routine and large-scale survey on public employees’ perceptions provide a natural opportunity to engage in broad and deep understanding of organizational phenomena in the management of human resources. Thirdly, we introduce optimization models as a way to provide practitioners-friendly predictions on combinations of job satisfaction constructs that may be worth considering together to improve well-being. We are not aware of any such approach as far as managing public personnel is concerned. Fourthly, unlike most scholarship, our work is based on large-sample surveys and replication efforts aimed at the testing the generalizability of the findings.

Limitations

From a practitioner standpoint, the main limitation of our study is that it provides valuable insights targeted to decision makers at the regional level. In other words, it is beyond the scope of this investigation providing analyses at the organizational level. The degree to which findings aggregated by region generalize to results aggregated by organization within regions remains to be tested. Similarly, providing analysis across typologies of health professionals – also through customized survey instruments – is outside the scope of our work, though an avenue of future work that might be worth pursuing.

Then, we must acknowledge that our work suffers from the same limitations that affect observational studies and combine logistic regression analyses with optimization techniques. Most notably, we are unable to establish cause-effect relationships between job satisfaction and its determinants or consequences. As to the representativeness of the sample, the inability to compare demographic statistics between the sample and the exact population of reference is due to the general data protection regulation—defined at the European Union level and detailed in national states—that is fully binding when doing research with real organizations. The regulation prohibits analyzing variables before the data collection is closed and storing any information of non-respondents. Although, a response rate of 80% or more is desired to establish scientific validity in epidemiology, researchers demonstrated that reaching that response rate is not always possible and can lead to other problems [ 57 ]. In addition, the response rates in our samples appear to be in line with those of established surveys, such as the NHS survey – where the lates response rate reached 46% or the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey – which registered a 34% participation in the latest edition. Of course, readers are encouraged to always keep in mind this feature when considering our work. Furthermore, concerns about the generalizability of results across operations (importantly of the job satisfaction variables), settings, and samples are legitimate. Similarly, the generalizability of our findings from the optimization analyses to other healthcare systems around the world is unknown because, to the best of our knowledge, this has no prior in the literature. Unfortunately, we are unable, at the moment, to expand our work by adding data collected in other countries around the globe. We very much encourage replication studies, which would serve as rigorous and challenging external validity tests of the current work. In fact, replication efforts are common practice for other topics in the healthcare management domains. As to regression analyses, omitted variable biases may impinge on the validity of the findings. Moreover, our analyses are nested within regions and comparisons across regions must be done with caution. In fact, our logistic regressions do not account for variables such as socio-demographic items that may be distributed differently in different regional healthcare systems.

As to the optimization techniques, we acknowledge that its sensitivity to changes in the magnitude of regression coefficients and the lack of cost structure impose a warning in deriving implications for practice. Indeed, the optimization model selects the best combination of correlates that might associate with an improved outcome based on their mean value and relative strength. This influences the stability of the optimization results. Also, the algorithm identifies a set of factors that together generate a preset level of increase in the overall satisfaction measures. Although these results are optimal within the context in which they were presented, they may not be the best possible from a cost perspective. Lacking cost information, the algorithm assumes that the cost to improve each of the predictors is equivalent. Form a practical perspective, however, implementing changes suggested by our findings may not translate into the most cost-effective reforms. To the contrary, there might be other interventions that improve job satisfaction and are less costly.

Our work on the job satisfaction correlates of about 73,000 public health employees paves the way for a more extensive use of work satisfaction and organizational climate survey among typologies of mission-driven organizations. Whereas questionnaires measuring the attitudes and the perceptions of government personnel such as the Federal Employee Viewpoint in the United States or of health professionals such as the survey of National Health System in the United Kingdom are now spread around the globe, similar inquiry are not yet common practice in other public institutions. Our study may be a systematic attempt to fill this gap. Furthermore, we emphasize the need to use any such survey for managerial efforts aimed at improving the quality of the organization and the well-being of their employees. In this regard, the optimization model seems helpful in deriving implications for practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available to maintain employers' and employees' confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Engaging Public Employees for a High-Performing Civil Service. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2016.

Ommen O, Driller E, Köhler T, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Neumann M, ..., Pfaff H. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and physician job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9(1):1–9.

Tyssen R, Palmer KS, Solberg IB, Voltmer E, Frank E. Physicians’ perceptions of quality of care, professional autonomy, and job satisfaction in Canada, Norway, and the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–10.

Article Google Scholar

Tsai Y. Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1–9.

Schuster C, Weitzman L, Sass Mikkelsen K, Meyer‐Sahling J, Bersch K, et al. Responding to COVID‐19 Through Surveys of Public Servants. Public Adm Rev. 2020;80(5):792-6.

Batura N, Skordis-Worrall J, Thapa R, Basnyat R, Morrison J. Is the Job Satisfaction Survey a good tool to measure job satisfaction amongst health workers in Nepal? Results of a validation analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–13.

Fernandez S, Resh WG, Moldogaziev T, Oberfield ZW. Assessing the past and promise of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey for public management research: a research synthesis. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(3):382–94.

Battaglio RP, Belle N, Cantarelli P. Self-determination theory goes public: experimental evidence on the causal relationship between psychological needs and job satisfaction. Public Manag Rev 2021:1–18.

Vainieri M, Ferre F, Giacomelli G, Nuti S. Explaining performance in health care: How and when top management competencies make the difference. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(4):306.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Vainieri M, Seghieri C, Barchielli C. Influences over Italian nurses’ job satisfaction and willingness to recommend their workplace. Health Serv Manage Res. 2021;34(2):62–9.

Angelis J, Glenngård AH, Jordahl H. Management practices and the quality of primary care. Public Money Manag. 2021;41(3):264–71.

Moynihan DP, Fernandez S, Kim S, LeRoux KM, Piotrowski SJ, Wright BE, Yang K. Performance regimes amidst governance complexity. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2011;21(suppl_1):i141–55.

Thomann E, Trein P, Maggetti M. What’s the problem? Multilevel governance and problem-solving. Eur Policy Anal. 2019;5(1):37–57.

Bevan G, Evans A, Nuti S. Reputations count: why benchmarking performance is improving health care across the world. Health Econ Policy Law. 2019;14(2):141–61.

Giacomelli G, Vainieri M, Garzi R, Zamaro N. Organizational commitment across different institutional settings: how perceived procedural constraints frustrate self-sacrifice. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2020:0020852320949629.

Glenngård AH, Anell A. The impact of audit and feedback to support change behaviour in healthcare organisations-a cross-sectional qualitative study of primary care centre managers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Abner GB, Kim SY, Perry JL. Building evidence for public human resource management: Using middle range theory to link theory and data. Review of Public Personnel Administration. 2017;37(2):139–59.

Krueger P, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, Edward HG, Lewis D, Tjam E. Organization specific predictors of job satisfaction: findings from a Canadian multi-site quality of work life cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2(1):1–8.

Raimondo E, Newcomer K. Mixed-methods inquiry in public administration: The interaction of theory, methodology, and praxis. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2017;37(2):183–201.

Brown AD, Sandoval GA, Levinton C, Blackstien-Hirsch P. Developing an efficient model to select emergency department patient satisfaction improvement strategies. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(1):3–10.

Sandoval GA, Levinton C, Blackstien-Hirsch P, Brown AD. Selecting predictors of cancer patients’ overall perceptions of the quality of care received. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):151–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seghieri C, Sandoval GA, Brown AD, Nuti S. Where to focus efforts to improve overall ratings of care and willingness to return: the case of Tuscan emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(2):136–44.

Barsanti S, Walker K, Seghieri C, Rosa A, Wodchis WP. Consistency of priorities for quality improvement for nursing homes in Italy and Canada: A comparison of optimization models of resident satisfaction. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):862–9.

Walker RM, Brewer GA, Lee MJ, Petrovsky N, Van Witteloostuijn A. Best practice recommendations for replicating experiments in public administration. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2019;29(4):609–26.

Zhu L, Witko C, Meier KJ. The public administration manifesto II: Matching methods to theory and substance. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2019;29(2):287–98.

Chamberlain SA, Hoben M, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Individual and organizational predictors of health care aide job satisfaction in long term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–9.

Cantarelli P, Belardinelli P, Belle N. A meta-analysis of job satisfaction correlates in the public administration literature. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2016;36(2):115–44.

Judge TA, Heller D, Mount MK. Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):530.

Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(3):376.

Rainey HG. Understanding and managing public organizations. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley; 2009.

Google Scholar

Kim S. Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2005;15:245–61.

Smith PC, Kendall LM, Hulin CL. The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1969.

Locke EA. The nature and cause of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, editor. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1976. p. 1297–343.

Vigan FA, Giauque D. Job satisfaction in African public administrations: a systematic review. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2018;84(3):596–610.

Homberg F, McCarthy D, Tabvuma V. A meta-analysis of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(5):711–22.

Judge TA, Piccolo RF, Podsakoff NP, Shaw JC, Rich BL. The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(2):157–67.

Djukic M, Jun J, Kovner C, Brewer C, Fletcher J. Determinants of job satisfaction for novice nurse managers employed in hospitals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(2):172–83.

Kalisch B, Lee KH. Staffing and job satisfaction: nurses and nursing assistants. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22:465Y471.

Noblet AJ, Allisey AF, Nielsen IL, Cotton S, LaMontagne AD, Page KM. The work-based predictors of job engagement and job satisfaction experienced by community health professionals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(3):237–46.

Poikkeus T, Suhonen R, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Relationships between organizational and individual support, nurses’ ethical competence, ethical safety, and work satisfaction. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):83–93.

Vainieri M, Smaldone P, Rosa A, Carroll K. The role of collective labor contracts and individual characteristics on job satisfaction in Tuscan nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(3):224.

Zhang M, Yang R, Wang W, Gillespie J, Clarke S, Yan F. Job satisfaction of urban community health workers after the 2009 healthcare reform in China: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(1):14–21.

Chordiya R, Sabharwal M, Battaglio RP. Dispositional and organizational sources of job satisfaction: a cross-national study. Public Manag Rev. 2019;21(8):1101–24.

Esteve M, Schuster C, Albareda A, Losada C. The effects of doing more with less in the public sector: evidence from a large-scale survey. Public Adm Rev. 2017;77(4):544–53.

Cantarelli P, Belle N, Longo F. Exploring the motivational bases of public mission-driven professions using a sequential-explanatory design. Public Manag Rev. 2019;22(10):1535-59.

Belle N, Cantarelli P. The role of motivation and leadership in public employees’ job preferences: evidence from two discrete choice experiments. Int Public Manag J. 2018;21(2):191–212.

Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. https://www.opm.gov/fevs/ [Last accessed March 2023].

Nuti S. La valutazione della performance in Sanità, Edizione Il Mulino. 2008.

Pizzini S, Furlan M. L’esercizio delle competenze manageriali e il clima interno. Il caso del Servizio Sanitario della Toscana. Psicologia Sociale. 2012;3(1):429–46.

Giacomelli G, Ferré F, Furlan M, Nuti S. Involving hybrid professionals in top management decision-making: How managerial training can make the difference. Health Serv Manage Res. 2019;32(4):168–79.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vardè AM, Mennini FS. Analysis evolution of personnel in the Italian National Healthcare Service with a view to health planning. MECOSAN. 2019;110:9–43. https://doi.org/10.3280/MESA2019-110002 .

Aloisio LD, Gifford WA, McGilton KS, Lalonde M, Estabrooks CA, Squires JE. Individual and organizational predictors of allied healthcare providers’ job satisfaction in residential long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–18.

van Diepen C, Fors A, Ekman I, Hensing G. Association between person-centred care and healthcare providers’ job satisfaction and work-related health: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042658.

Cunningham R, Westover J, Harvey J. Drivers of job satisfaction among healthcare professionals: a quantitative review. Int J Healthcare Manag. 2022:1–9.

Rowan BL, Anjara S, De Brún A, MacDonald S, Kearns EC, Marnane M, McAuliffe E. The impact of huddles on a multidisciplinary healthcare teams’ work engagement, teamwork and job satisfaction: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(3):382–93.

Sharma A, Borah SB, Moses AC. Responses to COVID-19: the role of governance, healthcare infrastructure, and learning from past pandemics. J Bus Res. 2021;122:597–607.

Hendra R, Hill A. Rethinking response rates: new evidence of little relationship between survey response rates and nonresponse bias. Eval Rev. 2019;43(5):307–30.

Download references

Acknowledgements

All authors are grateful to the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna) and its Network delle Regioni .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Management and Healthcare Laboratory, Institute of Management and L’EMbeDS, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Piazza Martiri Della Libertà 33, Pisa, 56127, Italy

Paola Cantarelli, Milena Vainieri & Chiara Seghieri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All Authors contributed equally. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paola Cantarelli .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval is unnecessary according to national legislation D. Lgs. 150/2009, art. 14.

The Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003 Code of Privacy requires public institutions to conduct employee viewpoint surveys and authorizes the use of employees’ data to evaluate the quality of service and identify organizational improvement actions. This legislative act does not ask for permission from an Ethical Committee when interviewing workers with regard to job satisfaction and related perceptions. This survey is considered as a service quality measurement activity and does not require an Ethics committee involvement. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, in written form. In other words, as human data are used, we confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cantarelli, P., Vainieri, M. & Seghieri, C. The management of healthcare employees’ job satisfaction: optimization analyses from a series of large-scale surveys. BMC Health Serv Res 23 , 428 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09426-3

Download citation

Received : 18 January 2023

Accepted : 19 April 2023

Published : 03 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09426-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Job satisfaction

- Healthcare employees

- Healthcare governance

- Large-scale viewpoint surveys

- Optimization analysis

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management – based on the study of Polish employees

- Open access

- Published: 28 March 2023

- Volume 19 , pages 1069–1100, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Barbara Sypniewska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8846-1183 1 ,

- Małgorzata Baran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8081-9512 2 &

- Monika Kłos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0663-0671 3

29k Accesses

15 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) views employees as a very important resource for the organisation, while paying close attention to their preferences, needs, and perspectives. The individual is an essential element of SHRM. The article focuses on analyzing selected SHRM issues related to the individual employee's level of job engagement and employee satisfaction. The main objective of our study was to identify individual-level correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction, such as: workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, job engagement, and employee satisfaction. Based on the results of a systematic literature review, we posed the following research question: is there any relation between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction in the SHRM context? To answer the research question, we have conducted a quantitative study on the sample of 1051 employees in companies in Poland and posed five hypotheses (H1-H5). The research findings illustrate that higher level of employee workplace well-being (H1), employee development, (H2), employee retention (H3) was related to higher level of employee engagement (H4), which in turn led to higher level of employee satisfaction. The results show the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee satisfaction (H5). The presented results contribute to the development of research on work engagement and job satisfaction in the practice of SHRM. By examining the impact of individual-level factors on job satisfaction, we explain which workplace factors should be addressed to increase an employee satisfaction and work engagement. The set of practical implications for managers implementing SHRM in the organization is discussed at the end of the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Work–Life Balance: Definitions, Causes, and Consequences

Employee Engagement: Keys to Organizational Success

Effect of green human resource management practices on organizational sustainability: the mediating role of environmental and employee performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) is of great importance for implementing sustainable development principles in an efficient and effective way. SHRM strategies lay the foundations to achieve it by raising employee awareness and forming desirable pro-social and environmental attitudes (Bombiak, 2020 ; Sharma et al., 2009 ).

The inclusion of the concept of sustainability in the management of organisations is a consequence of institutional pressures that have forced significant changes in this area as part of the drive for social acceptance (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 , p.1; Meyer & Rowan, 1977 ).

The term sustainability has different meanings depending on the perspective from which it is examined. The Resource Based View (RBV) inscribes the term in the strategic analysis of business, in relation to competitiveness in economic terms, and from an ecological perspective, in the environmental impact of the activities of various institutions (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 ). However, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) gives a definition of sustainability that refers to an organisation's activities and development in such a way that, while meeting the needs of the present, they do not endanger the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 , p.1; Ehnert, 2009 ; Barney, 1991 ).

From a strategic point of view, the human aspect is essential to build an effective and healthy organization (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ; Järlström et al., 2018 ; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ). Sustainable HRM views employees as a very important resource for the organisation, while paying close attention to their preferences, needs, and perspectives. SHRM activities are carried out with the aim of improving organisational performance by enabling the development of long-term relationships with employees. It follows that sustainable HRM demonstrates in companies a path of organisational development that is based on human development (Lestari et al., 2021 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 67; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ;).

Companies that are committed to their employees receive their work engagement in return. Organisations where HRM takes care of employees and their health retain more engaged, satisfied, and productive employees, with good overall health and well-being (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ; Sheraz et al., 2021 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 67;Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ).

Many authors argue that HR sustainability requires a focus on positive human/social outcomes identified at the individual, organizational, and societal level (Browning & Delahaye, 2011 ; Donnelly & Proctor-Thomson, 2011 ; Ehnert, 2009 ; Wells, 2011 ). The sustainable HRM seeks to achieve positive human outcomes by implementing sustainable work systems. Thus, it facilitates employees’ work-life balance without compromising performance (Indiparambil, 2019 ; Järlström et al., 2018 ). The sustainable HRM organisational practice manifests itself in employee’s commitment, employee’s satisfaction, and engagement (Chen & Chen, 2022 ; Parakandi & Behery, 2015 ). It is emphasized that by attracting and retaining talent, developing employee skills, and maintaining a healthy and productive workforce, SHRM practices in an organisation also affect employee satisfaction (Macke & Genari, 2019 ; Ehnert, 2006 ).

The article focuses on analyzing selected SHRM issues related to the individual employee's level of job engagement and employee satisfaction.

The main objective of our study was to identify individual-level correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction, such as workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, job engagement, and employee satisfaction.

The existing state of knowledge in the field of SHRM in the context of the individual employee, examined through a systematic literature review, has shown that there are current cognitive research gaps:

The organizational perspective dominates the research of SHRM, while a research gap has emerged in terms of research at the individual level in the literature.

The employee satisfaction in the context of SHRM has not been sufficiently studied in the literature.

Little research has been devoted to humanity in a sustainable work environment.

In particular, there is a lack of research focused on the relationship between employee workplace well-being, employee development and retention, and all those related to employee satisfaction and engagement in a sustainable work environment.

There is no such research (examining SHRM from the perspective of employees) conducted in Poland.

Based on the results of a systematic literature review, we posed the following research question: is there any relation between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction in the SHRM context? To answer the research question, we have conducted a quantitative study on the sample of 1051 employees from companies in Poland. We formulated the following hypotheses:

H1: Employee workplace well-being positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H2: Employee development positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H3: Employee retention positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H4: Employee engagement positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H5: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, and employee satisfaction.

The article presents the theoretical framework of the SHRM concept along with the research model (theoretical chapters). Section 3 is devoted to the methodological approach description. Section 4 contains the research sample characteristic, procedures for data analysis description, and study results presentation. The end of the paper is focused on conclusions with a discussion of the implications that follow from the results and paper limitations with directions of further scientific research.

The presented research results contribute to the development of research on work engagement and job satisfaction in the practice of SHRM. Firstly, by examining the impact of individual-level factors on job satisfaction, we explain how to motivate employees and which factors at work to focus on in order to increase employee satisfaction and work engagement.

Another of our contributions is a deeper understanding of the mediating role that employee engagement plays in job satisfaction. Our results showed that engagement and its dimensions mediate the relationship between individual factors (employee development well-being, retention, overall commitment) and job satisfaction.

Finally, our contribution is the set of practical implications for managers implementing SHRM in the organization, discussed at the end of the paper.

Theoretical framework

The very term sustainable HRM has been used for more than a decade. The literature is fragmented, diverse, and fraught with difficulties (Ehnert, 2009 ). No precise definition of the term exists and it has been used in a variety of ways. A number of notions have been used to link sustainability and HRM activities (Kramar, 2014 ). These include sustainable work systems (Abid et al., 2020 ; Docherty et al., 2002 ; Docherty et al.,; 2009 ), HR sustainability (Gollan, 2000 ; Wirtenberg et al., 2007 ), sustainable HR management (Kramar, 2014 ; Ehnert, 2011 , 2006 ), sustainable leadership (Avery, 2005 ; Avery & Bergsteiner, 2010 ;) and sustainable HRM (Mariappanadar, 2012 , 2003 ), HR aspects of sustainable organization (Dunphy et al., 2007 ), sustainable HRM policies (Mariappanadar, 2012 , 2003 ; Avery & Bergsteiner, 2010 ; Stanton et al., 2010 ; Ehnert, 2009 ; Dunphy et al., 2007 ; Purcell & Hutchinson, 2007 ; Teo & Rodwell, 2007 ), sustainable HRM practices (Jackson et al., 2011 ), sustainable work environment (Dunphy et al., 2007 ). Table 1 summarises the different contexts of the definition of sustainable HRM.

Linking sustainability and HRM is related to constantly increasing challenges inside and outside the organization. The challenges directly or indirectly affect the quality and the quantity of human resources. Sustainability is chosen for HRM due to its potential to overcome troubles and develop, to regenerate and preserve human resources in the organization.

In conjunction with economic performance, SHRM intervenes to address issues of engagement with environmental and social impacts. Strategic HRM emphasises the monitoring of human capital through accessible HR practices, taking the economic performance of employees as a basis. Sustainable HRM focuses on the development of an innovative workplace that provides a basis for internal and external social engagement and allows for greater environmental awareness and responsibility. These activities translate into promoting organisational success in a competitive environment. The development of new human resource management strategies and practices leads to economic, social, and environmental progress (Giang & Dung, 2022 ; Podgorodnichenko et al., 2020 ; Chamsa & García-Blandónb, 2019 , p. 111; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68)

Based on the literature review, we identified three approaches of sustainable HRM (Poon & Law, 2022 ; Chamsa & García-Blandónb, 2019 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 69)

A responsibility-oriented approach, namely, the well-being of employees, communities,and work-life balance,

Corporate objectives oriented towards efficiency and innovation, namely,the link between economic performance and sustainability expressed through environmental changes, quality of services and products, technological progress,

Resource-oriented approach, namely, responsible consumption.

In turn, Järlström et al. ( 2018 ) identify four dimensions of sustainable HRM, that is, fairness and equity, transparent HR practices, profitability, and employee well-being. The dimension of employee well-being promotes caring for and supporting employees with due respect. This shows that employees are not just a resource to be used, but an asset to be developed. Employee well-being here means well-being, health, protecting work relationships with others, and work-life balance. Moreover, in the individual sphere of employees, HRM promotes practices that foster mental and physical health, giving importance to the well-being of employees (Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68; Järlström et al., 2018 ). Sustainable HRM increases employee productivity while improving organisational capabilities by offering innovative HR practices. The individual employee is an essential element of SHRM, as it maximises the integration of employee goals with those of the organisation. An enterprise is considered sustainable when the legitimate needs of the enterprise, that is, productive employees, as well as employees, i.e., fair treatment, remuneration, mentoring (Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 68; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ;) are met.

The use of sustainable HRM practices becomes particularly important to ensure the proper development and well-being of employees. Moreover, many authors indicate a link between specific HRM practices, high levels of employee well-being, and employment (Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 ; Strenitzerová & Achimský, 2019 , p. 3; Cooper et al., 2019 ; Stankeviciute & Savaneviciene, 2018 , p. 8; Guest, 2017 ). In this aspect, the following groups of well-being-oriented practices become the most relevant, namely: training and development; mentoring, career support; creating challenging and autonomous work; providing information and receiving feedback; positive social and physical environment; employee voice; and organisational support (Cooper et al., 2019 ; Guest, 2017 ; Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 ;).

Sustainable HRM contributes to attracting and retaining human resource over time (Lopez-Cabrales & Valle-Cabrera, 2020 ; Ehnert, 2009 , p. 180). Employee development, remaining in a competitive work environment, increasing efficiency, and employee work well-being can only be ensured by meeting the needs of employees and providing them with sustainable working environment (Ali et al., 2021 ; Cantele & Zardini, 2018 ; Chatzopoulou et al., 2015 ; Ehnert, 2009 , 2014 ; Guerci et al., 2014 ; Lorincova et al., 2018 ; Mariappanadar, 2014 ; Monusova, 2008 ; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, 2015 ).

At the same time, employee satisfaction itself becomes one of the fundamental aspects of overall well-being and employee sustainable development. Human resources bring talent and expertise to an organization, and these are developed over the course of a career. In the long run, employee development and organisational contributions can translate into higher employee satisfaction and hence organisational commitment (Jaskeviciute et al., 2021 , p. 120; Abid et al., 2020 ; Davidescu et al., 2020 ; Cannas et al., 2019 ; Indiparambil et al., 2019 , p. 69;).

Job satisfaction is a complex and controversial construct, on which there is no single definition. Consensually, it is considered one of the most positive attitudes towards work itself. Currently, there is a predominance of a multidimensional approach that understands satisfaction as a tripartite psychological response composed of feelings, ideas, and intentions to act, by which people evaluate their work experiences in an emotional and/or cognitive way (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012 ). Specialists agree on the positive impact and beneficial consequences of satisfaction in the workplace. (Böckerman & Ilmakunnas, 2012 ).

Job satisfaction is defined as a positive or pleasant emotional state resulting from job evaluation (Locke, 1976 ) and acquired experiences on the job (Makin et al., 2000 , pp. 82–83). It is an expression of emotional attitude towards the job and the tasks performed, and an emotional response to the job (Spector, 1985 ). It is also an emotional response to the performance of tasks and roles, and in crisis situations, employees with higher job satisfaction will have more strength and energy (Rhéaume, 2021 ; Bańka, 1996 , p.69;).

A review of the literature shows that job satisfaction is also related to engagement (Chordiya et al., 2017 ), intentions to remain in the company (Zhang et al., 2016 ), and trust in the supervisor (Gockel et al., 2013 ).

There are two main approaches to measuring job satisfaction: an overall measure of satisfaction and one that relates to specific aspects of satisfaction. The literature recommends measuring not only overall job satisfaction, but also how its individual components are experienced by employees and affect overall satisfaction. Such multidimensional measures contribute more to a better and deeper understanding of the issue and highlight the importance of job satisfaction especially in the context of sustainable HRM.

It is recognized that job satisfaction is the degree to which employees feel that their needs and expectations are being met. Satisfaction develops through cognitive and emotional responses.

The person-environment fit theory can be a useful framework for understanding why some practices of SHRM have the ability to generate employee satisfaction. This theory holds that the degree of fit between employee needs and organizational supplies impacts employees’ attitudes. Hence, it is likely that positive job satisfaction arises when the degree of perceived fit between the person and the work environment is high, while negative attitudes would develop when the person-environment adjustment is perceived to be low (Salanova et al., 2012 ).

Ensuring that these practices are implemented results in positive outcomes for the individual and the organisation. As part of the successful application of sustainable HRM practices, great importance is placed on aspects related to employee individual development and employee well-being. These strongly influence employee satisfaction and engagement (Zaugg et al., 2001 , p. 3; Cleveland & Cavanagh, 2015 ).

In this article, we focus on job satisfaction, as it is seen as particularly important for the sustainability of workplaces and entire organizations.

Research model

In order to build research conceptual model, we used a systematic literature review methodology (Czakon, 2011 ). According to the adopted methodology, we carried out the procedure in three stages. The first stage included: (a) definition of the database and the set of publications; (b) selection of publications; (c) elaboration of the final publication database; (d) bibliometric and content analysis of selected materials. Publications for analysis were collected from the EBSCO database. Scientific publications (articles, book chapters) that contained the phrases [sustainable* or sustainable HRM* humanity* job satisfaction* engagement*] were searched. Eligibility criteria were fixed so that studies published in peer-reviewed full-length articles, written in English, were selected for the review process. The search at this stage resulted in over 496 publications in total. In the second step, the we applied the following selection criteria: publications in the field of personnel management, HRM, job satisfaction. This allowed the number of publications to be narrowed down for in-depth substantive analysis, which was carried out in the third stage of the systematic literature review. An accumulated collection of 158 publications was used for this purpose.

The different approaches are not mutually exclusive. Despite their differences, they have one thing in common: understanding that sustainability refers to a long-term and sustainable outcome (Kramar, 2014 , p. 1076).

Based on the results of the literature review, we identified two levels of sustainable HRM contributions – organizational level and individual employee level. The summary is presented in the Table 2 .

The presented issues based on the systematic literature review, have become the basis for hypotheses The authors have focused on the individual employee level of analyses.

It should be noted that despite the extensive discussion in the literature on both the individual and organizational level of SHRM, the research is dominated by the organizational perspective. SHRM is a phenomenon dependent not only on internal organizational conditions, but also on certain characteristics of individual employees. The literature does not provide an answer to the question about the relationship between SHRM on the individual level in the context of employee satisfaction. Moreover, the literature does not explain why higher well-being at work, workforce training, or efforts to retain employees on the part of the company can lead to greater workforce satisfaction.

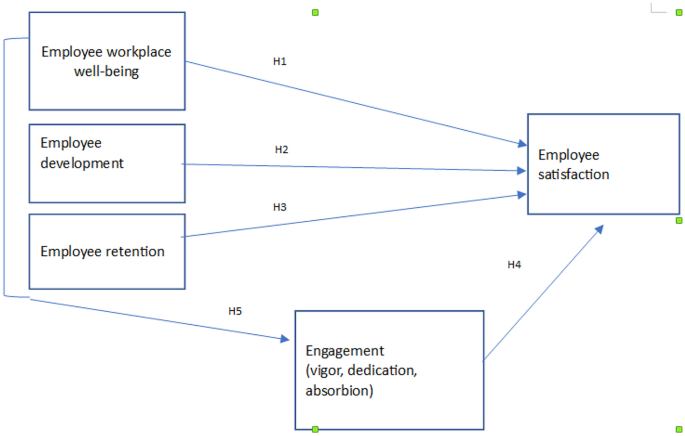

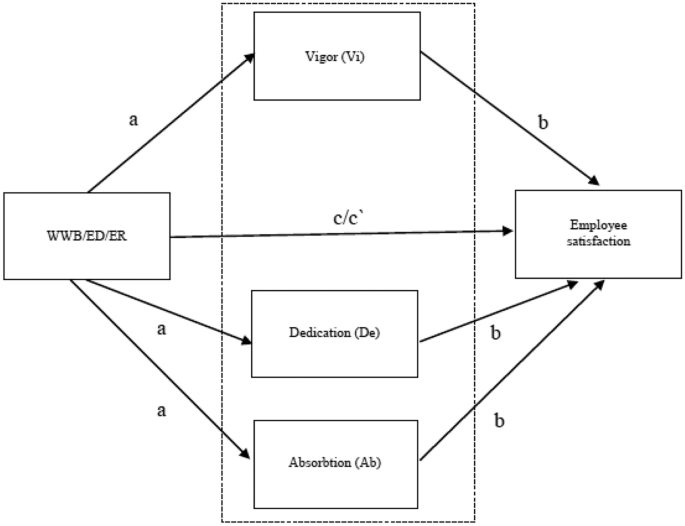

This results in the main research objective of the article, which is recognition of correlations between factors affecting employee satisfaction (employee workplace well-being, employee development, employee retention, work engagement) and employee satisfaction, from the perspective of employee in the sustainable HRM context. Considering the results of systematic literature review, the research model was built to determine the relationships between identified variables (Fig. 1 ).

Source: own elaboration

Research model.

The existing state of knowledge in the field of SHRM in the individual employee context, examined through a systematic literature review has shown that there are current cognitive research gaps. For example, few studies have been devoted to humanity in a sustainable work environment. In particular, there is a lack of research focused on the relationship between employee workplace well-being, employee development and retention, and all these (relationships) related to the employee satisfaction and employee engagement in a sustainable work environment. Therefore, as far as the authors are concerned, there is no such research (from the perspective of employees) conducted in Poland.

The following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1: Employee workplace well-being (EWW) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H2: Employee development (ED) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H3: Employee retention (ER) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H4: Employee engagement (EG) positively correlates with employee satisfaction.

H5: Employee engagement (EG) mediates relationships between employee workplace well-being (EWW), employee development (ED), employee retention (ER) and employee satisfaction.

Based on a review of the well-being literature, Page and Vella-Brodrick ( 2009 ) have argued that employee well-being (EWB) should be measured in terms of social well-being (SWB), psychological well-being (PWB), and work-related affect, that is, workplace well-being (WWB). The last is related to work satisfaction and work-related affect. Employees reporting positive well-being tend to demonstrate higher job satisfaction and job performance as compared to those reporting low levels of well-being (Wright et al., 2007 ).

Raising perceptions of organizational support involves developing leaders and policies that convey consideration for employees' needs, well-being, challenges, and concerns (Eisenberger et al., 1997 ). Workplace well-being is a pleasant or positive emotional state resulting from job evaluation or work experiences (Locke, 1970 ). Bakker and Leiter ( 2010 ) argue that an employee's sense of well-being occurs when they find their job satisfying and when emotions such as joy and happiness prevail. This is supported by studies of the relationship between well-being and job satisfaction, which show that increased well-being accompanies higher job satisfaction (Browne, 2021 ; Machin-Rincon et al., 2020 ; Rhéaume, 2021 ; Wu et al., 2021 ).

A popular analysis of employee well-being includes a concept known as the Vitamin Model of Employee Well-Being by Warr ( 1994 ). The author singles out characteristics of work in the organizational environment that in varying degrees of intensity affect employee well-being (Warr & Clapperton, 2010 ). The model uses comparing work characteristics to vitamins in the human body, which depending on the intensity can positively or negatively affect it. In this case, there is a relationship between their intensity, and job satisfaction. This model focuses on the relationship between job characteristics and mental health of individuals. Employee satisfaction which comes through many ways and one of them is workplace well-being. Employee satisfaction appears in many ways, in various studies. One of them is well-being in the workplace (Siddiqui & Ijaz, 2022 ). Employees in companies implementing wellness programs reported higher work satisfaction rates than those in companies without wellness programs, thereby suggesting that these wellness programs may positively affect job satisfaction for employees (Pawar & Kunte, 2022 ).

Accordingly, we hypothesized that employee workplace well-being positively correlates with employee satisfaction (H1).

Employee-oriented HRM denote the organization’s investment in its human resources, especially in what concerns its growth and professional development.

In organizations characterized by employee centered HRM, given the importance of welfare and development (Clarke & Hill, 2012 ), it would be expected to find higher levels of job satisfaction among its members. Evidence (Hantula, 2015 ) indicates that the most satisfied employees are those who work in positions that offer them freedom, independence, and discretion to schedule work and decide on procedures; autonomy for decision making, as well as opportunities to apply and develop personal skills and competences.

Current changes in the workplace are causing some researchers to take a holistic view of HR culture in an organization to study its impact on employee job satisfaction, and have revealed that there is a correlation between career development and other variables, namely, employee motivation and job satisfaction (Akdere & Egan, 2020 ; Lestari et al., 2021 ; Sheraz et al., 2021 ).

The employees and the management work on the same page and achieve the desired goals. According to Järlström et al. ( 2018 ), sustainable HRM builds a positive path and valuable strategies to maintain progress and employee development. It means a company must be conscious regarding developing their entrepreneurial HR development-based policies and strategies within a workplace.

Development opportunities are a form of recognition for employees' work, which in turn translates into career advancement. Understanding the competencies that will be needed in the future contributes to the design of development plans. Future promotion, which is associated with higher pay, depends on the skills possessed, so allowing employees to develop them can increase employee satisfaction. Increased knowledge and skills can translate into increased satisfaction, due to the achievement of professional goals (satisfaction with one's career) and personal goals (feeling of professional success).

Based on a study conducted by Nguyen and Duong ( 2020 ), it shows that there was a strong positive relationship between training and development element on employee satisfaction.