- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 70, 2019, review article, how to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses.

- Andy P. Siddaway 1 , Alex M. Wood 2 , and Larry V. Hedges 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 70:747-770 (Volume publication date January 2019) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 08, 2018

- Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- APA Publ. Commun. Board Work. Group J. Artic. Rep. Stand. 2008 . Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be?. Am. Psychol . 63 : 848– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF 2013 . Writing a literature review. The Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology MJ Prinstein, MD Patterson 119– 32 New York: Springer, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1997 . Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 3 : 311– 20 Presents a thorough and thoughtful guide to conducting narrative reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ 1995 . Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychol . Bull 118 : 172– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Hedges LV , Higgins JPT , Rothstein HR 2009 . Introduction to Meta-Analysis New York: Wiley Presents a comprehensive introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Higgins JPT , Hedges LV , Rothstein HR 2017 . Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 : 5– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL , Thoemmes FJ , Rosenthal R 2014 . Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 333– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ 1994 . Vote-counting procedures. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 193– 214 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J 2014 . Priming, replication, and the hardest science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 40– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I 2007 . The lethal consequences of failing to make use of all relevant evidence about the effects of medical treatments: the importance of systematic reviews. Treating Individuals: From Randomised Trials to Personalised Medicine PM Rothwell 37– 58 London: Lancet [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collab. 2003 . Glossary Rep., Cochrane Collab. London: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary Presents a comprehensive glossary of terms relevant to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD , Becker BJ 2003 . How meta-analysis increases statistical power. Psychol. Methods 8 : 243– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2003 . Editorial. Psychol. Bull. 129 : 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2016 . Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5th ed.. Presents a comprehensive introduction to research synthesis and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM , Hedges LV , Valentine JC 2009 . The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G 2014 . The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7– 29 Discusses the limitations of null hypothesis significance testing and viable alternative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Earp BD , Trafimow D 2015 . Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front. Psychol. 6 : 621 [Google Scholar]

- Etz A , Vandekerckhove J 2016 . A Bayesian perspective on the reproducibility project: psychology. PLOS ONE 11 : e0149794 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ , Brannick MT 2012 . Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychol. Methods 17 : 120– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL , Berlin JA 2009 . Effect sizes for dichotomous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis H Cooper, LV Hedges, JC Valentine 237– 53 New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R 2014 . Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how. Innovation 27 : 67– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Olkin I 1980 . Vote count methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88 : 359– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Pigott TD 2001 . The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 6 : 203– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT , Green S 2011 . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 London: Cochrane Collab. Presents comprehensive and regularly updated guidelines on systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- John LK , Loewenstein G , Prelec D 2012 . Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 : 524– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Juni P , Witschi A , Bloch R , Egger M 1999 . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282 : 1054– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O , Doyen S , Leys C , Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama PA , Miller S et al. 2012 . Low hopes, high expectations: expectancy effects and the replicability of behavioral experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 : 6 572– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Lau J , Antman EM , Jimenez-Silva J , Kupelnick B , Mosteller F , Chalmers TC 1992 . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 : 248– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ , Smith PV 1971 . Accumulating evidence: procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educ. Rev. 41 : 429– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW , Wilson D 2001 . Practical Meta-Analysis London: Sage Comprehensive and clear explanation of meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE , Cook TD 1994 . Threats to the validity of research synthesis. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 503– 20 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE , Lau MY , Howard GS 2015 . Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean?. Am. Psychol. 70 : 487– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Hopewell S , Schulz KF , Montori V , Gøtzsche PC et al. 2010 . CONSORT explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340 : c869 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , Altman DG PRISMA Group. 2009 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 : 332– 36 Comprehensive reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A , Polisena J , Husereau D , Moulton K , Clark M et al. 2012 . The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28 : 138– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LD , Simmons J , Simonsohn U 2018 . Psychology's renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 511– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Noblit GW , Hare RD 1988 . Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SA , Macedo LG , Gadotti IC , Fuentes J , Stanton T , Magee DJ 2008 . Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 88 : 156– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Open Sci. Collab. 2015 . Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 : 943 [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BL , Thorne SE , Canam C , Jillings C 2001 . Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Patil P , Peng RD , Leek JT 2016 . What should researchers expect when they replicate studies? A statistical view of replicability in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 539– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R 1979 . The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 : 638– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL , Rosenthal R 1989 . Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 44 : 1276– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S , Tatt ID , Higgins JP 2007 . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 : 666– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R , Crooks D , Stern PN 1997 . Qualitative meta-analysis. Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue JM Morse 311– 26 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE , Rodgers JL 2018 . Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 487– 510 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W , Strack F 2014 . The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF , Berlin JA , Morton SC , Olkin I , Williamson GD et al. 2000 . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE): a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 : 2008– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S , Jensen L , Kearney MH , Noblit G , Sandelowski M 2004 . Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 14 : 1342– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Tong A , Flemming K , McInnes E , Oliver S , Craig J 2012 . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12 : 181– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D , Siddaway AP , Meiser-Stedman R , Serpell L , Field AP 2012 . A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32 : 122– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC , Biglan A , Boruch RF , Castro FG , Collins LM et al. 2011 . Replication in prevention science. Prev. Sci. 12 : 103– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Synthesis without meta...

Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline

Linked opinion.

Grasping the nettle of narrative synthesis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Joanne E McKenzie , associate professor 2 ,

- Amanda Sowden , professor 3 ,

- Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi , clinical senior research fellow 1 ,

- Sue E Brennan , research fellow 2 ,

- Simon Ellis , associate director 4 ,

- Jamie Hartmann-Boyce , senior researcher 5 ,

- Rebecca Ryan , senior esearch fellow 6 ,

- Sasha Shepperd , professor 7 ,

- James Thomas , professor 8 ,

- Vivian Welch , associate professor 9 ,

- Hilary Thomson , senior research fellow 1

- 1 MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, UK

- 2 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 3 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 4 Centre for Guidelines, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, UK

- 5 Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 6 School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

- 7 Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 8 Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre, University College London, London, UK

- 9 Bruyere Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- Correspondence to: M Campbell Mhairi.Campbell{at}glasgow.ac.uk

- Accepted 8 October 2019

In systematic reviews that lack data amenable to meta-analysis, alternative synthesis methods are commonly used, but these methods are rarely reported. This lack of transparency in the methods can cast doubt on the validity of the review findings. The Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline has been developed to guide clear reporting in reviews of interventions in which alternative synthesis methods to meta-analysis of effect estimates are used. This article describes the development of the SWiM guideline for the synthesis of quantitative data of intervention effects and presents the nine SWiM reporting items with accompanying explanations and examples.

Summary points

Systematic reviews of health related interventions often use alternative methods of synthesis to meta-analysis of effect estimates, methods often described as “narrative synthesis”

Serious shortcomings in reviews that use “narrative synthesis” have been identified, including a lack of description of the methods used; unclear links between the included data, the synthesis, and the conclusions; and inadequate reporting of the limitations of the synthesis

The Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guideline is a nine item checklist to promote transparent reporting for reviews of interventions that use alternative synthesis methods

The SWiM items prompt users to report how studies are grouped, the standardised metric used for the synthesis, the synthesis method, how data are presented, a summary of the synthesis findings, and limitations of the synthesis

The SWiM guideline has been developed using a best practice approach, involving extensive consultation and formal consensus

Decision makers consider systematic reviews to be an essential source of evidence. 1 Complete and transparent reporting of the methods and results of reviews allows users to assess the validity of review findings. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) statement, consisting of a 27 item checklist, was developed to facilitate improved reporting of systematic reviews. 2 Extensions are available for different approaches to conducting reviews (for example, scoping reviews 3 ), reviews with a particular focus (for example, harms 4 ), and reviews that use specific methods (for example, network meta-analysis. 5 ) However, PRISMA provides limited guidance on reporting certain aspects of the review, such as the methods for presentation and synthesis, and no reporting guideline exists for synthesis without meta-analysis of effect estimates. We estimate that 32% of health related systematic reviews of interventions do not do meta-analysis, 6 7 8 instead using alternative approaches to synthesis that typically rely on textual description of effects and are often referred to as narrative synthesis. 9 Recent work highlights serious shortcomings in the reporting of narrative synthesis, including a lack of description of the methods used, lack of transparent links between study level data and the text reporting the synthesis and its conclusions, and inadequate reporting of the limitations of the synthesis. 7 This suggests widespread lack of familiarity and misunderstanding around the requirements for transparent reporting of synthesis when meta-analysis is not used and indicates the need for a reporting guideline.

Scope of SWiM reporting guideline

This paper presents the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline. The SWiM guideline is intended for use in systematic reviews examining the quantitative effects of interventions for which meta-analysis of effect estimates is not possible, or not appropriate, for a least some outcomes. 10 Such situations may arise when effect estimates are incompletely reported or because characteristics of studies (such as study designs, intervention types, or outcomes) are too diverse to yield a meaningful summary estimate of effect. 11 In these reviews, alternative presentation and synthesis methods may be adopted, (for example, calculating summary statistics of intervention effect estimates, vote counting based on direction of effect, and combining P values), and SWiM provides guidance for reporting these methods and results. 11 Specifically, the SWiM guideline expands guidance on “synthesis of results” items currently available, such as PRISMA (items 14 and 21) and RAMESES (items 11, 14, and 15). 2 12 13 SWiM covers reporting of the key features of synthesis including how studies are grouped, synthesis methods used, presentation of data and summary text, and limitations of the synthesis.

SWiM is not intended for use in reviews that synthesise qualitative data, for which reporting guidelines are already available, including ENTREQ for qualitative evidence synthesis and eMERGe for meta-ethnography. 14 15

Development of SWiM reporting guideline

A protocol for the project is available, 10 and the guideline development was registered with the EQUATOR Network, after confirmation that no similar guideline was in development. All of the SWiM project team are experienced systematic reviewers, and one was a co-author on guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis (AS). 9 A project advisory group was convened to provide greater diversity in expertise. The project advisory group included representatives from collaborating Cochrane review groups, the Campbell Collaboration, and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (see supplementary file 1).

The project was informed by recommendations for developing guidelines for reporting of health research. 16 We assessed current practice in reporting synthesis of effect estimates without meta-analysis and used the findings to devise an initial checklist of reporting items in consultation with the project advisory group. We invited 91 people, all systematic review methodologists or authors of reviews that synthesised results from studies without using meta-analysis, to participate in a three round Delphi exercise, with a response rate of 48% (n=44/91) in round one, 54% (n=37/68) in round two, and 82% (n=32/39) in round three. The results were discussed at a consensus meeting of an expert panel (the project advisory group plus one additional methodological expert) (see supplementary file 1). After the meeting, we piloted the revised guideline to assess ease of use and face validity. Eight systematic reviewers with varying levels of experience, who had not been involved in the Delphi exercise, were asked to read and apply the guideline. We conducted short interviews with the pilot participants to identify any clarification needed in the items or their explanations. We subsequently revised the items and circulated them for comment among the expert panel, before finalising them. Full methodological details of the SWiM guideline development process are provided in supplementary file 1.

Synthesis without meta-analysis reporting items

We identified nine items to guide the reporting of synthesis without meta-analysis. Table 1 shows these SWiM reporting items. An online version is available at www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines . An explanation and elaboration for each of the reporting items is provided below. Examples to illustrate the reporting items and explanations are provided in supplementary file 2.

Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) items: SWiM is intended to complement and be used as an extension to PRISMA

- View inline

Item 1: grouping studies for synthesis

1a) description.

Provide a description of, and rationale for, the groups used in the synthesis (for example, groupings of interventions, population, outcomes, study design).

1a) Explanation

Methodological and clinical or conceptual diversity may occur (for example, owing to inclusion of diverse study designs, outcomes, interventions, contexts, populations), and it is necessary to clearly report how these study characteristics are grouped for the synthesis, along with the rationale for the groups (see Cochrane Handbook Chapter 3 17 ). Although reporting the grouping of study characteristics in all reviews is important, it is particularly important in reviews without meta-analysis, as the groupings may be less evident than when meta-analysis is used.

Providing the rationale, or theory of change, for how the intervention is expected to work and affect the outcome(s) will inform authors’ and review users’ decisions about the appropriateness and usefulness of the groupings. A diagram, or logic model, 18 19 can be used to visually articulate the underlying theory of change used in the review. If the theory of change for the intervention is provided in full elsewhere (for example, in the protocol), this should be referenced. In Cochrane reviews, the rationale for the groups can be outlined in the section “How the intervention is expected to work.”

1b) Description

Detail and provide rationale for any changes made subsequent to the protocol in the groups used in the synthesis.

1b) Explanation

Decisions about the planned groups for the syntheses may need to be changed following study selection and data extraction. This may occur as a result of important variations in the population, intervention, comparison, and/or outcomes identified after the data are collected, or where limited data are available for the pre-specified groupings, and the groupings may need to be modified to facilitate synthesis (Cochrane Handbook Chapter 2 20 ). Reporting changes to the planned groups, and the reason(s) for these, is important for transparency, as this allows readers to assess whether the changes may have been influenced by study findings. Furthermore, grouping at a broader level of (any or multiple) intervention, population, or outcome will have implications for the interpretation of the synthesis findings (see item 8).

Item 2: describe the standardised metric and transformation method used

Description.

Describe the standardised metric for each outcome. Explain why the metric(s) was chosen, and describe any methods used to transform the intervention effects, as reported in the study, to the standardised metric, citing any methodological guidance used.

Explanation

The term “standardised metric” refers to the metric that is used to present intervention effects across the studies for the purpose of synthesis or interpretation, or both. Examples of standardised metrics include measures of intervention effect (for example, risk ratios, odds ratios, risk differences, mean differences, standardised mean differences, ratio of means), direction of effect, or P values. An example of a statistical method to convert an odds ratio to a standardised mean difference is that proposed by Chinn (2000). 21 For other methods and metrics, see Cochrane Handbook Chapter 6. 22

Item 3: describe the synthesis methods

Describe and justify the methods used to synthesise the effects for each outcome when it was not possible to undertake a meta-analysis of effect estimates.

For various reasons, it may not be possible to do a meta-analysis of effect estimates. In these circumstances, other synthesis methods need to be considered and specified. Examples include combining P values, calculating summary statistics of intervention effect estimates (for example, median, interquartile range) or vote counting based on direction of effect. See table 2 for a summary of possible synthesis methods (for further details, see McKenzie and Brennan 2019 11 ). Justification should be provided for the chosen synthesis method.

Questions answered according to types of synthesis methods and types of data used

Item 4: criteria used to prioritise results for summary and synthesis

Where applicable, provide the criteria used, with supporting justification, to select particular studies, or a particular study, for the main synthesis or to draw conclusions from the synthesis (for example, based on study design, risk of bias assessments, directness in relation to the review question).

Criteria may be used to prioritise the reporting of some study findings over others or to restrict the synthesis to a subset of studies. Examples of criteria include the type of study design (for example, only randomised trials), risk of bias assessment (for example, only studies at a low risk of bias), sample size, the relevance of the evidence (outcome, population/context, or intervention) pertaining to the review question, or the certainty of the evidence. Pre-specification of these criteria provides transparency as to why certain studies are prioritised and limits the risk of selective reporting of study findings.

Item 5: investigation of heterogeneity in reported effects

State the method(s) used to examine heterogeneity in reported effects when it is not possible to do a meta-analysis of effect estimates and its extensions to investigate heterogeneity.

Informal methods to investigate heterogeneity in the findings may be considered when a formal statistical investigation using methods such as subgroup analysis and meta-regression is not possible. Informal methods could involve ordering tables or structuring figures by hypothesised modifiers such as methodological characteristics (for example, study design), subpopulations (for example, sex, age), intervention components, and/or contextual/setting factors (see Cochrane Handbook Chapter 12 11 ). The methods used and justification for the chosen methods should be reported. Investigations of heterogeneity should be limited, as they are rarely definitive; this is more likely to be the case when informal methods are used. It should also be noted if the investigation of heterogeneity was not pre-specified.

Item 6: certainty of evidence

Describe the methods used to assess the certainty of the synthesis findings.

The assessment of the certainty of the evidence should aim to take into consideration the precision of the synthesis finding (confidence interval if available), the number of studies and participants, the consistency of effects across studies, the risk of bias of the studies, how directly the included studies address the planned question (directness), and the risk of publication bias. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) is the most widely used framework for assessing certainty (Cochrane Handbook Chapter 14 23 ). However, depending on the synthesis method used, assessing some domains (for example, consistency of effects when vote counting is undertaken) may be difficult.

Item 7: data presentation methods

Describe the graphical and tabular methods used to present the effects (for example, tables, forest plots, harvest plots).

Specify key study characteristics (for example, study design, risk of bias) used to order the studies, in the text and any tables or graphs, clearly referencing the studies included

Study findings presented in tables or graphs should be ordered in the same way as the syntheses are reported in the narrative text to facilitate the comparison of findings from each included study. Key characteristics, such as study design, sample size, and risk of bias, which may affect interpretation of the data, should also be presented. Examples of visual displays include forest plots, 24 harvest plots, 25 effect direction plots, 26 albatross plots, 27 bubble plots, 28 and box and whisker plots. 29 McKenzie and Brennan (2019) provide a description of these plots, when they should be used, and their pros and cons. 11

Item 8: reporting results

For each comparison and outcome, provide a description of the synthesised findings and the certainty of the findings. Describe the result in language that is consistent with the question the synthesis addresses and indicate which studies contribute to the synthesis.

For each comparison and outcome, a description of the synthesis findings should be provided, making clear which studies contribute to each synthesis (for example, listing in the text or tabulated). In describing these findings, authors should be clear about the nature of the question(s) addressed (see table 2 , column 1), the metric and synthesis method used, the number of studies and participants, and the key characteristics of the included studies (population/settings, interventions, outcomes). When possible, the synthesis finding should be accompanied by a confidence interval.An assessment of the certainty of the effect should be reported.

Results of any investigation of heterogeneity should be described, noting if it was not pre-planned and avoiding over-interpretation of the findings.

If a pre-specified logic model was used, authors may report any changes made to the logic model during the review or as a result of the review findings. 30

Item 9: limitations of the synthesis

Report the limitations of the synthesis methods used and/or the groupings used in the synthesis and how these affect the conclusions that can be drawn in relation to the original review question.

When reporting limitations of the synthesis, factors to consider are the standardised metric(s) used, the synthesis method used, and any reconfiguration of the groups used to structure the synthesis (comparison, intervention, population, outcome).

The choice of metric and synthesis method will affect the question addressed (see table 2 ). For example, if the standardised metric is direction of effect, and vote counting is used, the question will ask “is there any evidence of an effect?” rather than “what is the average intervention effect?” had a random effects meta-analysis been used.

Limitations of the synthesis might arise from post-protocol changes in how the synthesis was structured and the synthesis method selected. These changes may occur because of limited evidence, or incompletely reported outcome or effect estimates, or if different effect measures are used across the included studies. These limitations may affect the ability of the synthesis to answer the planned review question—for example, when a meta-analysis of effect estimates was planned but was not possible.

The SWiM reporting guideline is intended to facilitate transparent reporting of the synthesis of effect estimates when meta-analysis is not used. The guideline relates specifically to transparently reporting synthesis and presentation methods and results, and it is likely to be of greatest relevance to reviews that incorporate diverse sources of data that are not amenable to meta-analysis. The SWiM guideline should be used in conjunction with other reporting guidelines that cover other aspects of the conduct of reviews, such as PRISMA. 31 We intend SWiM to be a resource for authors of reviews and to support journal editors and readers in assessing the conduct of a review and the validity of its findings.

The SWiM reporting items are intended to cover aspects of presentation and synthesis of study findings that are often left unreported when methods other than meta-analysis have been used. 7 These include reporting of the synthesis structure and comparison groupings (items 1, 4, 5, and 6), the standardised metric used for the synthesis (item 2), the synthesis method (items 3 and 9), presentation of data (item 7), and a summary of the synthesis findings that is clearly linked to supporting data (item 8). Although the SWiM items have been developed specifically for the many reviews that do not include meta-analysis, SWiM promotes the core principles needed for transparent reporting of all synthesis methods including meta-analysis. Therefore, the SWiM items are relevant when reporting synthesis of quantitative effect data regardless of the method used.

Reporting guidelines are sometimes interpreted as providing guidance on conduct or used to assess the quality of a study or review; this is not an appropriate application of a reporting guideline, and SWiM should not be used to guide the conduct of the synthesis. For guidance on how to conduct synthesis using the methods referred to in SWiM, we direct readers to the second edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, specifically chapter 12. 11 Although an overlap inevitably exists between reporting and conduct, the SWiM reporting guideline is not intended to be prescriptive about choice of methods, and the level of detail for each item should be appropriate. For example, investigation of heterogeneity (item 5) may not always be necessary or useful. In relation to SWiM, we anticipate that the forthcoming update of PRISMA will include new items covering a broader range of synthesis methods, 32 but it will not provide detailed guidance and examples on synthesis without meta-analysis.

The SWiM reporting guideline emerged from a project aiming to improve the transparency and conduct of narrative synthesis (ICONS-Quant: Improving the CONduct and reporting of Narrative Synthesis). 10 Avoidance of the term “narrative synthesis” in SWiM is a deliberate move to promote clarity in the methods used in reviews in which the synthesis does not rely on meta-analysis. The use of narrative is ubiquitous across all research and can serve a valuable purpose in the development of a coherent story from diverse data. 33 34 However, within the field of evidence synthesis, narrative approaches to synthesis of quantitative effect estimates are characterised by a lack of transparency, making assessment of the validity of their findings difficult. 7 Together with the recently published guidance on conduct of alternative methods of synthesis, 11 the SWiM guideline aims to improve the transparency of, and subsequently trust in, the many reviews that synthesise quantitative data without meta-analysis, particularly for reviews of intervention effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Delphi survey and colleagues who informally piloted the guideline.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of SWiM. HT had the idea for the study. HT, SVK, AS, JEM, and MC designed the study methods. JT, JHB, RR, SB, SE, SS, and VW contributed to the consensus meeting and finalising the guideline items. MC prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. HT is the guarantor.

Project advisory group members: Simon Ellis, Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Mark Petticrew, Rebecca Ryan, Sasha Shepperd, James Thomas, Vivian Welch.

Expert panel members: Sue Brennan, Simon Ellis, Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, Rebecca Ryan, Sasha Shepperd, James Thomas, Vivian Welch.

Funding: This project was supported by funds provided by the Cochrane Methods Innovation Fund. MC, HT, and SVK receive funding from the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12017-13 and MC_UU_12017-15) and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU13 and SPHSU15). SVK is supported by an NHS Research Scotland senior clinical fellowship (SCAF/15/02). JEM is supported by an NHMRC career development fellowship (1143429). RR’s position is funded by the NHMRC Cochrane Collaboration Funding Program (2017-2010). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of their employer/host organisations or of Cochrane or its registered entities, committees, or working groups.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: funding for the project as described above; HT is co-ordinating editor for Cochrane Public Health; SVK, SE, JHB, RR, and SS are Cochrane editors; JEM is co-convenor of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group; JT is a senior editor of the second edition of the Cochrane Handbook; VW is editor in chief of the Campbell Collaboration and an associate scientific editor of the second edition of the Cochrane Handbook; SB is a research fellow at Cochrane Australia; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee (reference number 400170060).

Transparency: The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Patient and public involvement: This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop outcomes or interpret the results.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The authors plan to disseminate the research through peer reviewed publications, national and international conferences, webinars, and an online training module and by establishing an email discussion group.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- Donnelly CA ,

- Campbell P ,

- Liberati A ,

- Altman DG ,

- Tetzlaff J ,

- Tricco AC ,

- Zorzela L ,

- Ioannidis JP ,

- PRISMAHarms Group

- Salanti G ,

- Caldwell DM ,

- Shamseer L ,

- Campbell M ,

- Katikireddi SV ,

- Katikireddi S ,

- Roberts H ,

- Higgins J ,

- Chandler J ,

- McKenzie J ,

- Greenhalgh T ,

- Westhorp G ,

- Buckingham J ,

- Flemming K ,

- McInnes E ,

- France EF ,

- Cunningham M ,

- Schulz KF ,

- Higgins JPT ,

- McKenzie JE ,

- Brennan SE ,

- Anderson LM ,

- Petticrew M ,

- Rehfuess E ,

- Schünemann HJ ,

- Ogilvie D ,

- Thomson HJ ,

- Harrison S ,

- Martin RM ,

- Higgins JPT

- Schriger DL ,

- Schroter S ,

- Rehfuess EA ,

- Brereton L ,

- PRISMA Group

- ↵ Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, et al. Updating the PRISMA reporting guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: study protocol. 2018. https://osf.io/xfg5n .

- Melendez-Torres GJ ,

- O’Mara-Eves A ,

- Petticrew M

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

“narrative synthesis” of quantitative effect data in cochrane reviews: current issues and ways forward.

In these videos, the presenters give an overview of current use of, and reasons for using narrative approaches to synthesis. They describe use of the term “narrative synthesis” and common issues in narrative synthesis including transparency in reporting and ambiguity about narrative synthesis as a method. They also provide an overview of how transparency can be improved and finish by introducing the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline, which is the focus of the second webinar. The work presented is from the ICONS-Quant (Improving the Conduct and reporting of Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative data) project which is funded by the Cochrane Strategic Methods Fund (May 2017-May 2019).

The webinar was delivered in February 2020 and below you will find the videos from the webinar, together with accompanying slides to download [PDF].

Part 1: Definition and use of ‘narrative synthesis’ Part 2: Reasons for using ‘narrative synthesis’ Part 3: Common issues in ‘narrative synthesis’ Part 4: Improving transparency in synthesis without meta-analysis; moving from ‘narrative synthesis’ to SWiM Part 5: Questions and answers

Presenter bios.

Dr Hilary Thomson , co-ordinating editor of Cochrane Public Health, Senior Research Fellow, University of Glasgow. Hilary Thomson has extensive experience in conducting large complex reviews of questions about the health impacts of social policy interventions such as housing, transport, and welfare. Her work focusses on ways to improve the reliability and utility of systematic reviews that address public health policy relevant questions.

Mhairi Campbell , Systematic Reviewer, University of Glasgow. Mhairi Campbell has broad experience of conducting complex systematic reviews, including: qualitative evidence of policy interventions, review of theories linking income and health, and research investigating the reporting of narrative synthesis methods of quantitative data in public health systematic reviews.

Part 1: Definition and use of ‘narrative synthesis’

Part 2: Reasons for using ‘narrative synthesis’

Part 3: Common issues in ‘narrative synthesis’

Part 4: Improving transparency in synthesis without meta-analysis; moving from ‘narrative synthesis’ to SWiM

Part 5: Questions and answers

Additional materials

Download the slides from the webinar [PDF]

Which review is that? A guide to review types

- Which review is that?

- Review Comparison Chart

- Decision Tool

- Critical Review

- Integrative Review

- Narrative Review

- State of the Art Review

- Narrative Summary

- Systematic Review

- Meta-analysis

- Comparative Effectiveness Review

- Diagnostic Systematic Review

- Network Meta-analysis

- Prognostic Review

- Psychometric Review

- Review of Economic Evaluations

- Systematic Review of Epidemiology Studies

- Living Systematic Reviews

- Umbrella Review

- Review of Reviews

- Rapid Review

- Rapid Evidence Assessment

- Rapid Realist Review

- Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

- Qualitative Interpretive Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Research Synthesis

- Framework Synthesis - Best-fit Framework Synthesis

- Meta-aggregation

- Meta-ethnography

- Meta-interpretation

- Meta-narrative Review

- Meta-summary

- Thematic Synthesis

- Mixed Methods Synthesis

Narrative Synthesis

- Bayesian Meta-analysis

- EPPI-Centre Review

- Critical Interpretive Synthesis

- Realist Synthesis - Realist Review

- Scoping Review

- Mapping Review

- Systematised Review

- Concept Synthesis

- Expert Opinion - Policy Review

- Technology Assessment Review

- Methodological Review

- Systematic Search and Review

Narrative’ synthesis’ refers to an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis. Whilst narrative synthesis can involve the manipulation of statistical data, the defining characteristic is that it adopts a textual approach to the process of synthesis to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from the included studies. As used here ‘narrative synthesis’ refers to a process of synthesis that can be used in systematic reviews focusing on a wide range of questions, not only those relating to the effectiveness of a particular intervention. (Popay et al. 2006)

Further Reading/Resources

Guidelines Campbell, M., McKenzie, J. E., Sowden, A., Katikireddi, S. V., Brennan, S. E., Ellis, S., ... & Thomson, H. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. bmj , 368 . Full Text Other

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., ... & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version , 1 (1), b92. Full Text

Thomson H, Campbell M. “Narrative synthesis” of quantitative effect data in Cochrane reviews: Current issues and ways forward [Internet]. Cochrane Learning Live Webinar Series 2020 Feb. Full Text

Morley, G., Ives, J., Bradbury-Jones, C., & Irvine, F. (2019). What is 'moral distress'? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nursing ethics , 26 (3), 646–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017724354 Link

References Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., ... & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version , 1 (1), b92. Full Text

- << Previous: Mixed Methods Synthesis

- Next: Meta-narrative Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 19, 2024 1:08 PM

- URL: https://unimelb.libguides.com/whichreview

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 March 2019

A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis on the risks of medical discharge letters for patients’ safety

- Christine Maria Schwarz 1 ,

- Magdalena Hoffmann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1668-4294 1 , 2 ,

- Petra Schwarz 3 ,

- Lars-Peter Kamolz 1 ,

- Gernot Brunner 1 &

- Gerald Sendlhofer 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 158 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

51 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The medical discharge letter is an important communication tool between hospitals and other healthcare providers. Despite its high status, it often does not meet the desired requirements in everyday clinical practice. Occurring risks create barriers for patients and doctors. This present review summarizes risks of the medical discharge letter.

The research question was answered with a systematic literature research and results were summarized narratively. A literature search in the databases PubMed and Cochrane Library for Studies between January 2008 and May 2018 was performed. Two authors reviewed the full texts of potentially relevant studies to determine eligibility for inclusion. Literature on possible risks associated with the medical discharge letter was discussed.

In total, 29 studies were included in this review. The major identified risk factors are the delayed sending of the discharge letter to doctors for further treatments, unintelligible (not patient-centered) medical discharge letters, low quality of the discharge letter, and lack of information as well as absence of training in writing medical discharge letters during medical education.

Conclusions

Multiple risks factors are associated with the medical discharge letter. There is a need for further research to improve the quality of the medical discharge letter to minimize risks and increase patients’ safety.

Peer Review reports

The medical discharge letter is an important communication medium between hospitals and general practitioners (GPs) and an important legal document for any queries from insurance carriers, health insurance companies, and lawyers [ 1 ]. Furthermore, the medical discharge letter is an important document for the patient itself.

A timely transmission of the letter, a clear documentation of findings, an adequate assessment of the disease as well as understandable recommendations for follow-up care are essential aspects of the medical discharge letter [ 2 ]. Despite this importance, medical discharge letters are often insufficient in content and form [ 3 ]. It is also remarkable that writing of medical discharge letters is often not a particular subject in the medical education [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, the medical discharge letter is an important medical document as it contains a summary of the patient’s hospital admission, diagnosis and therapy, information on the patient’s medical history, medication, as well as recommendations for continuity of treatment. A rapid transmission of essential findings and recommendations for further treatment is of great interest to the patient (as well as relatives and other persons that are involved in the patients’ caring) and their current and future physicians. In most acute care hospitals, patients receive a preliminary medical discharge letter (short discharge letter) with diagnoses and treatment recommendations on the day of discharge [ 5 ]. Unfortunately, though, the full hospital medical discharge letter, which is often received with great delay, is an area of constant conflict between GPs and hospital doctors [ 1 ]. Thus the medical discharge letter does not only represent a feature of process and outcome quality of a clinic, but also influences confidence building and binding of resident physicians to the hospital [ 6 ].

Beside the transmission of patients’ findings from physician to physician, the delivery of essential information to the patient is an underestimated purpose of the medical discharge letter [ 7 ]. The medical discharge letter is often characterized by a complex medical language that is often not understood by the patients. In recent years, patient-centered/patient-directed medical discharge letters are more in discussion [ 8 ]. Thus, the medical discharge letter points out risks for patients and physicians while simultaneously creating barriers between them.

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to identify patient safety risks associated with the medical discharge letter.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the electronic databases PubMed and Cochrane Database. Additionally, we scanned the reference lists of selected articles (snowballing). The following search terms were used: “discharge summary AND risks”, “discharge summary AND risks AND patient safety” and “discharge letter AND risks” and “discharge letter AND risks AND patient safety”. We reviewed relevant titles and abstracts on English and German literature published between January 2008 and May 2018 and started the search at the beginning of February 2018 and finished it at the end of May 2018.

Eligibility criteria

In this systematic review, articles were included if the title and/or abstract indicated the report of results of original research studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method approaches. Studies in paediatric settings or studies that do not handle possible risks of the medical discharge letter were excluded, as well as reports, commentaries and letters. Electronic citations, including available abstracts of all articles retrieved from the search, were screened by two authors to select reports for full-text review. Duplicates were removed from the initial search. Nevertheless, during the search of articles the selection, publication as well as language bias must be considered. Thereafter, full-texts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed to determine eligibility for inclusion. In the following Table 1 inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies are listed. Afterwards, key outcomes and main results were summarized. Differences were resolved by consensus. Finally, a narrative synthesis of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was conducted. Reference management software MENDELEY (Version 1.19.3) was used to organise and store the literature.

Data extraction

The data extraction in form of a table was used to summarize study results. The two authors extracted the data relating to author, country, year, study design, and outcome measure as well as potential risk factors to patient safety directly into a pre-formatted data collection form. After data extraction, the literature was discussed and synthesized into themes. The evaluation of the single studies was done using checklists [STROBE (combined) and the Cochrane Data collection form for intervention reviews (RCTs and non-RCTs)]. Meta-analysis was not considered appropriate for this body of literature because of the wide variability of studies in relation to research design, study population, types of interventions and outcomes.

Then a narrative synthesis was performed to synthesize the findings of the different studies. Because of the range of very different studies that were included in this systematic review, we have decided that a narrative synthesis constitutes the best instrument to synthesise the findings of the studies. First, a preliminary synthesis was undertaken in form of a thematic analysis involving searching of studies, listing and presenting results in tabular form. Then the results were discussed again and structured into themes. Afterwards, summarizing of included studies in a narrative synthesis within a framework was performed by one author.

This framework consisted of the following factors: the individuals and the environment involved in the studies (doctors, hospitals), the tools and technology (such as discharge letter delivery systems), the content of the medical discharge letter (such as missing content, quality of content), the accuracy and timeliness of transfer. These themes were discussed in relation to potential risks for patient’s safety. All articles that were included in this review were published before. The framework of this study was chosen following a previously published systematic review dealing with patient risks associated with telecare [ 9 ].

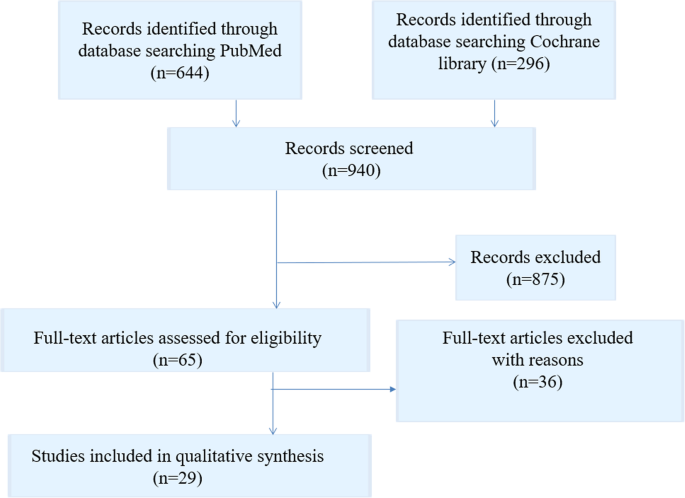

The initial literature search in the two online databases identified 940 records. From these records, 65 full text articles were screened for eligibility. Then 36 full-text articles were excluded because they pertained to patient transfer within the hospital or to another hospital, or to patient hand-over situations. Finally, 29 studies were included in this review. Included studies are listed in Table 2 . All document types were searched with a focus on primary research studies. The results of the search strategy are shown in Fig. 1 .

Flow chart literature search strategy

From these 29 studies, 13 studies dealt with the quality analysis of discharge letters, 12 studies with delayed transmission of medical discharge letters and just as many with the lack of information in medical discharge letters. Only few studies dealt with training on writing medical discharge letters and with understanding of patients of their medical discharge letters. The descriptive information of the included articles is presented in Table 2 . Overall quality of the articles was found to be acceptable, with clearly stated research questions and appropriate used methods.

Risk factors

In the following the identified major risk factors concerning the medical discharge letter are presented in a narrative summary.

Delayed delivery

The medical discharge letters should arrive at the GP soon after hospital discharge to ensure the quickest possible further treatment [ 4 ]. If letters are delivered weeks after the hospital stay, a continuous treatment of the patient cannot be ensured. Furthermore, the author of the medical discharge letter will no longer have current data after the discharge of the patient, which may result in a loss of important information [ 10 ]. Interfaces between different treatment areas and organizational units are known to cause a loss of information and a lack of quality in patient handling [ 11 ]. The improvement of information transfer between different healthcare providers during the transition of patients has been recommended to improve patient care [ 12 , 13 ]. Delayed communication of findings may lead to a lack of continuity of care and suboptimal outcomes, as well as decreased satisfaction levels for both patients and GPs [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. In a review of Kripalani et al., it was shown that 25% of discharge summaries were never received by GPs [ 17 ]. This has several negative consequences for patients. Li et al. [ 18 ] found that a delayed transmission or absence of the medical discharge summary is related to patient readmission, and a study by Gilmore-Bykovskyi [ 19 ] found a strong relationship between patients whose discharge summaries omitted designation of a responsible clinician/clinic for follow-up care and re-hospitalisation and/or death. A Swedish study by Carlsson et al. [ 20 ] points out that a lack of accuracy and continuity in discharge information on eating difficulties may increase risk of undernutrition and related complications. A study of Were et al. [ 18 ] investigated pending lab results in medical discharge summaries and found that only 16% of tests with pending results were mentioned in the discharge summaries, and Walz et al. [ 21 ] found that approximately one third of the sub-acute care patients had pending lab results at discharge, but only 11% of these were documented in the medical discharge summaries.

Quality, lack of information

Medical discharge letters are a key communication tool for patient safety issues [ 17 ]. Incomplete and insufficient medical discharge letters increase the risks of readmission and myriad other complications [ 22 ]. Langelaan et al. (2017) evaluated more than 2000 medical discharge letters and found that in about 60% of the letters essential information was missing, such as a change of the existing medication, laboratory data, and even data on the patients themselves [ 23 ]. Accurate and complete medical discharge summaries are essential for patient safety [ 17 , 24 , 25 ]. Addresses; patient data, including duration of stay; diagnoses; procedures; operations; epicrisis and therapy recommendations; as well as findings in the appendix; are minimum requirements that are supposed to be included in the medical discharge letter [ 4 ]. However, it was found that key components are often lacking in medical discharge letters, including information about follow-up and management plans [ 23 , 26 ], test results [ 27 , 28 , 29 ], and medication adjustments [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. In a review of Wimsett et al. [ 36 ] key components of a high-quality medical discharge summary were identified in 32 studies. These important components were discharge diagnosis, the received treatment, results of investigations as well as follow-up plans.

Accuracy of patients’ medication information is important to ensure patient safety. Hospital doctors expect GPs to continue with the prescribed (or modified) drug therapy. However, the selection of certain drugs is not always transparent for the GPs. A study by Grimes et al. [ 30 ] found that a discrepancy in medication documentation at discharge occurred in 10.8% of patients. From these patients nearly 65.5% were affected by discrepancies in medication documentation. The most prevalent inconsistency was drug omission (20.9%). Only 2% of patients were contacted, although general patient harm was assessed. A Swedish study of 2009 [ 37 ] investigated the quality improvement of medical discharge summaries. A higher quality of discharge letter led to an average of 45% fewer medication errors per patient.

A recent study by Tong et al. [ 38 ] revealed a reduced rate of medication errors in medical discharge summaries that were completed by a hospital pharmacist. Hospital pharmacists play a key role in preparing the discharge medication information transferred to GPs upon patient discharge and should work closely with hospital doctors to ensure accurate medication information that is quickly communicated to GPs at transitions of care [ 39 ]. Most hospitals have introduced electronic systems to improve the discharge communication, and many studies found a significant overall improvement in electronic transfer systems due to better documentation of information about follow-up care, pending test results, and information provided to patients and relatives [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Mehta et al. [ 43 ] found that the changeover to a new electronic system resulted in an increased completeness of discharge summaries from 60.7 to 75.0% and significant improvements in levels of completeness in certain categories.

Writing of medical discharge letter is missing in medical education

Both junior doctors as well as medical students reported that they received inadequate guidance and training on how to write medical discharge summaries [ 44 , 45 ] and recognized that higher priority is often given to pressing clinical tasks [ 46 ]. Research into the causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors at hospitals in the UK has revealed that latent conditions like organizational processes, busy environments, and medical care for complex patients can lead to medication errors in the medical discharge summary [ 47 ].

Fortunately, some study results demonstrate that information and education on writing medical discharge letters would enhance communication to the GPs and prevent errors during the patient discharge process [ 37 ]. Minimal formal teaching about writing medical discharge summaries is common in most medical schools [ 39 , 46 ]; however, a study by Shivji et al. has shown that simple, intensive educational sessions can lead to an improvement in the writing process of medical discharge summaries and communication with primary care [ 48 ].

Since the medical discharge letter should meet specific quality criteria, senior physicians and/or the head physician correct(s) and validate(s) the letter. The medical discharge letter therefore represents an essential learning target [ 8 ]. Training activities and workshops are necessary for junior doctors to improve writing medical discharge letters [ 44 , 49 ]. It might be also useful for young doctors to use checklists or other structured procedures to improve writing [ 4 ]. Maher et al. showed that the use of a checklist enhanced the quality (content, structure, and clarity) of medical discharge letters written by medical students [ 50 ].

In the following Table 3 main risk factors of the medical discharge letter are summarized.

The results of this systematic literature research indicate notable risk factors relating to the medical discharge letter. In a study by Sendlhofer et al., 360 risks were identified in hospital settings [ 51 ]. From these, 176 risks were scored as strategic and clustered into “top risks”. Top risks included medication errors, information errors, and lack of communication, among others. During this review, these potential risk factors were also identified in terms of the medical discharge letter.

Delayed sending and low quality of medical discharge letters to the referring physicians, may adversely affect the further course of treatment. However, a study of Spencer et al. has determined rates of failures in processing actions requested in hospital discharge summaries in general practice. It was found that requested medication changes were not made in 17% and patient harm occurred in 8% in relation to failures [ 52 ].

Despite the existence of reliable standards [ 53 ] many physicians are not adequately trained for writing medical discharge letters during their studies. Regular trainings and workshops and standardized checklists may optimize the quality of the medical discharge letter. Furthermore, electronic discharge letters have the potential to easily and quickly extract important information such as diagnoses, medication, and test results into a structured discharge document, and offer important advantages such as reliability, speed of information transfer, and standardization of content. Comprehensive discharge letters reduce the readmission rate and increase safety and quality by discharging of the patient. A missing structure, as well as a complex language, illegible handwriting, and unknown abbreviations, make reading medical discharge letters more complicated [ 4 ]. At least, poor patient understanding of their diagnosis and treatment plans and incomprehensible recommendations can adversely impact clinical outcome following hospital discharge. Many studies confirm that inadequate communication of findings [ 3 , 39 , 54 ] is an important risk factor in patients’ safety [ 51 ].

Most medical information in the discharge letter is not understood by patients (as well as relatives and other persons that are involved in the patients’ caring) and patients themselves do not receive a comprehensible medical discharge letter. The content of the medical discharge letter is often useless for the patient due to its medical terminology and content that is not matching with the patient’s level of knowledge or health literacy [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. Poor understanding of diagnoses and related discharge plans are common among patients and family members and often accompanied by unplanned hospital readmissions [ 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 ]. In a study by Lin et al., it was shown that a patient-directed discharge letter enhanced understanding for hospitalization and for recommendations. Furthermore, verbal communication of the letter contents, explanation of every section of the medical discharge letter, and the opportunity for discussion and asking questions improved patient comprehension [ 7 ]. A study by O’Leary et al. showed that roughly 80–95% of patients with breast tumours want to be informed and educated about their illness, treatment, and prognosis [ 62 ].

High quality of care is characterized by a patient-centered communication, where the patient’s personal needs are also in focus [ 63 ]. Translation of medical terms in reports and letters leads to a better understanding of the disease and, interestingly, the avoidance of medical terms did not lead to deterioration in the transmission of information between the treating physicians. Moreover, it was found that the minimisation of medical terminology in medical discharge letters improved understanding and perception of patients’ ability to manage chronic health conditions [ 64 ]. In effect, it is clear that patient-centered communication improves outcome, mental health, patient satisfaction and reduces the use of health services [ 65 ].

Strengths and limitations

We have identified key problems with the medical discharge summaries that negatively impact patients’ safety and wellbeing. However, there is a heterogeneous nature of the included studies in terms of study design, sample size, outcomes, and language. Only two reviewers screened the studies for eligibility and only full-text articles were included in the literature review; furthermore, only the databases Pubmed and Cochrane library were screened for appropriate studies. Due to these constraints, there is a chance that other relevant studies may have been missed.

High-quality medical discharge letters are essential to ensure patient safety. To address this, the current review identified the major risk factors as delayed sending and low quality of medical discharge letters, lack of information and patient understanding, and inadequate training in writing medical discharge letters. In future, research studies should focus on improving the communication of pending test results and findings at discharge, and on evaluating the impact that this improved communication has on patient outcomes. Moreover, a simple patient-centered medical discharge letter may improve the patient’s (as well as family members’ and other caregivers’) understanding of disease, treatment and post-discharge recommendations.

Abbreviations

General practitioner

Randomized Controlled Trial

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

United Kingdom

Kreße B, Dinser R. Anforderungen an Arztberichte- ein haftungsrechtlicher Ansatz. Medizinrecht. 2010;28(6):396–400.

Google Scholar

Möller K-H, Makoski K. Der Arztbrief - Rechtliche Rahmen- Bedingungen. 2015;5:186–94.

Van Walraven C, Weinberg AL. Quality assessment of a discharge summary system. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1437–42.

PubMed Google Scholar

Unnewehr M, Schaaf B, Friederichs H. Die Kommunikation optimieren. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(37):831–4.

Roth-Isigkeit A, Harder S. Die Entlassungsmedikation im Arztbrief. Eine explorative Befragung von Hausärzten/−innen. Vol. 100, Medizinische Klinik. 2005. p. 87–93.

Bohnenkamp B. Arbeitsorganisation: Der Arztbrief - Viel mehr als nur lästige Pflicht. Vol. 113, Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2016. p. 2–4.

Lin R, Tofler G, Spinaze M, Dennis C, Clifton-Bligh R, Nojoumian H, Gallagher R, et al. Patient-directed discharge letter (PADDLE)-a simple and brief intervention to improve patient knowledge and understanding at time of hospital discharge. Hear Lung Circ. 2012;21:S312.

Hammerer P. Patientenverständliche Arztbriefe und Befunde. Springer Medizin. 2018;33(2):119–23.

Guise V, Anderson J, Wiig S. Patient safety risks associated with telecare: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):588.

Raab, A., & Drissner A. Einweiserbeziehungsmanagement: Wie Krankenhäuser erfolgreich Win-Win-Beziehungen zu niedergelassenen Ärzten aufbauen. Kohlhammer Verlag; 2011. 240 p.143.

Hart D. Vertrauen, Kooperation, Organisation. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2006. p. 845–7.

Cook RI. Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):791–4.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Duggan C, Feldman R, Hough J, Bates I. Reducing adverse prescribing discrepancies following hospital discharge. Int J Pharm Pract. 1998;6(2):77–82.

Polyzotis PA, Suskin N, Unsworth K, Reid RD, Jamnik V, Parsons C, et al. Primary care provider receipt of cardiac rehabilitation discharge summaries are they getting what they want to promote long-term risk reduction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(1):83–9.

Poon EG, Gandhi TK, Sequist TD, Murff HJ, Karson AS, Bates DW. “I wish i had seen this test result earlier!”: Dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Vol. 164, Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004. p. 2223–8.

Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: Challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Vol. 141, Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004. p. 533–6.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Were MC, Li X, Kesterson J, Cadwallader J, Asirwa C, Khan B, et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow-up providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1002–6.

Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Kennelty KA, Dugoff E, Kind AJH. Hospital discharge documentation of a designated clinician for follow-up care and 30-day outcomes in hip fracture and stroke patients discharged to sub-acute care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1).

Carlsson E, Ehnfors M, Eldh AC, Ehrenberg A. Accuracy and continuity in discharge information for patients with eating difficulties after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(1–2):21–31.

Walz SE, Smith M, Cox E, Sattin J, Kind AJH. Pending laboratory tests and the hospital discharge summary in patients discharged to sub-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):393–8.

Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, Chen C, Kanade S, Van Ness PH, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):436–43.

Alderton M, Callen JL. Are general practitioners satisfied with electronic discharge summaries? Vol. 36, Health Information Management Journal. 2007. p. 7–12.

Harel Z, Wald R, Perl J, Schwartz D, Bell CM. Evaluation of deficiencies in current discharge summaries for dialysis patients in Canada. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:77–84.

Philibert I, Barach P. The European HANDOVER Project: A multi-nation program to improve transitions at the primary care - Inpatient interface. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21(SUPPL. 1).

Greer RC, Liu Y, Crews DC, Jaar BG, Rabb H, Boulware LE. Hospital discharge communications during care transitions for patients with acute kidney injury: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:449.

Belleli E, Naccarella L, Pirotta M. Communication at the interface between hospitals and primary care: a general practice audit of hospital discharge summaries. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(12):886–90.

Roy CL, Poon EC, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–8.

Gandara E, Moniz T, Ungar J, Lee J, Chan-Macrae M, O’Malley T, et al. Communication and information deficits in patients discharged to rehabilitation facilities: an evaluation of five acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E28–33.

Grimes T, Delaney T, Duggan C, Kelly JG, Graham IM. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharge: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir J Med Sci. 2008;177(2):93–7.

Uitvlugt EB, Siegert CEH, Janssen MJA, Nijpels G, Karapinar-Çarkit F. Completeness of medication-related information in discharge letters and post-discharge general practitioner overviews. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1206–12.

Ooi CE, Rofe O, Vienet M, Elliott RA. Improving communication of medication changes using a pharmacist-prepared discharge medication management summary. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(2):394–402.

Perren A, Previsdomini M, Cerutti B, Soldini D, Donghi D, Marone C. Omitted and unjustified medications in the discharge summary. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18(3):205–8.

CAS Google Scholar

Garcia BH, Djønne BS, Skjold F, Mellingen EM, Aag TI. Quality of medication information in discharge summaries from hospitals: an audit of electronic patient records. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(6):1331–7.

Monfort AS, Curatolo N, Begue T, Rieutord A, Roy S. Medication at discharge in an orthopaedic surgical ward: quality of information transmission and implementation of a medication reconciliation form. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):838–47.

Wimsett J, Harper A, Jones P. Review article: Components of a good quality discharge summary: A systematic review. Vol. 26, EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2014. p. 430–8.

Bergkvist A, Midlöv P, Höglund P, Larsson L, Bondesson Å, Eriksson T. Improved quality in the hospital discharge summary reduces medication errors-LIMM: Landskrona integrated medicines management. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):1037–46.

Tong EY, Roman CP, Mitra B, Yip GS, Gibbs H, Newnham HH, et al. Reducing medication errors in hospital discharge summaries: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2017;206(1):36–9.

Yemm R, Bhattacharya D, Wright D, Poland F. What constitutes a high quality discharge summary? A comparison between the views of secondary and primary care doctors. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:125–31.

O’Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, Liss DT, Evans DB, Kulkarni N, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):219–25.

Chan S. P Maurice a, W pollard C, Ayre SJ, Walters DL, Ward HE. Improving the efficiency of discharge summary completion by linking to preexisiting patient information databases. BMJ Qual Improv Reports. 2014;3(1):1–5.

Lehnbom EC, Raban MZ, Walter SR, Richardson K, Westbrook JI. Do electronic discharge summaries contain more complete medication information? A retrospective analysis of paper versus electronic discharge summaries. Heal Inf Manag J. 2014;43(3):4–12.

Mehta RL, Baxendale B, Roth K, Caswell V, Le Jeune I, Hawkins J, et al. Assessing the impact of the introduction of an electronic hospital discharge system on the completeness and timeliness of discharge communication: A before and after study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1).

Heaton A, Webb DJ, Maxwell SRJ. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: the views of 2413 UK medical students and recent graduates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):128–34.

Maxwell S, Walley T. Teaching safe and effective prescribing in UK medical schools: A core curriculum for tomorrow’s doctors. Vol. 55, British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2003. p. 496–503.

Frain JP, Frain AE, Carr PH. Experience of medical senior house officers in preparing discharge summaries. Br Med J. 1996;312(7027):350.

Dornan T, Investigator P, Ashcroft D, Lewis P, Miles J, Taylor D, et al. An in depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. EQUIP study. Vol. 44, Methods. 2010.

Shivji FS, Ramoutar DN, Bailey C, Hunter JB. Improving communication with primary care to ensure patient safety post-hospital discharge. Br J Hosp Med. 2015;76(1):46–9.