- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

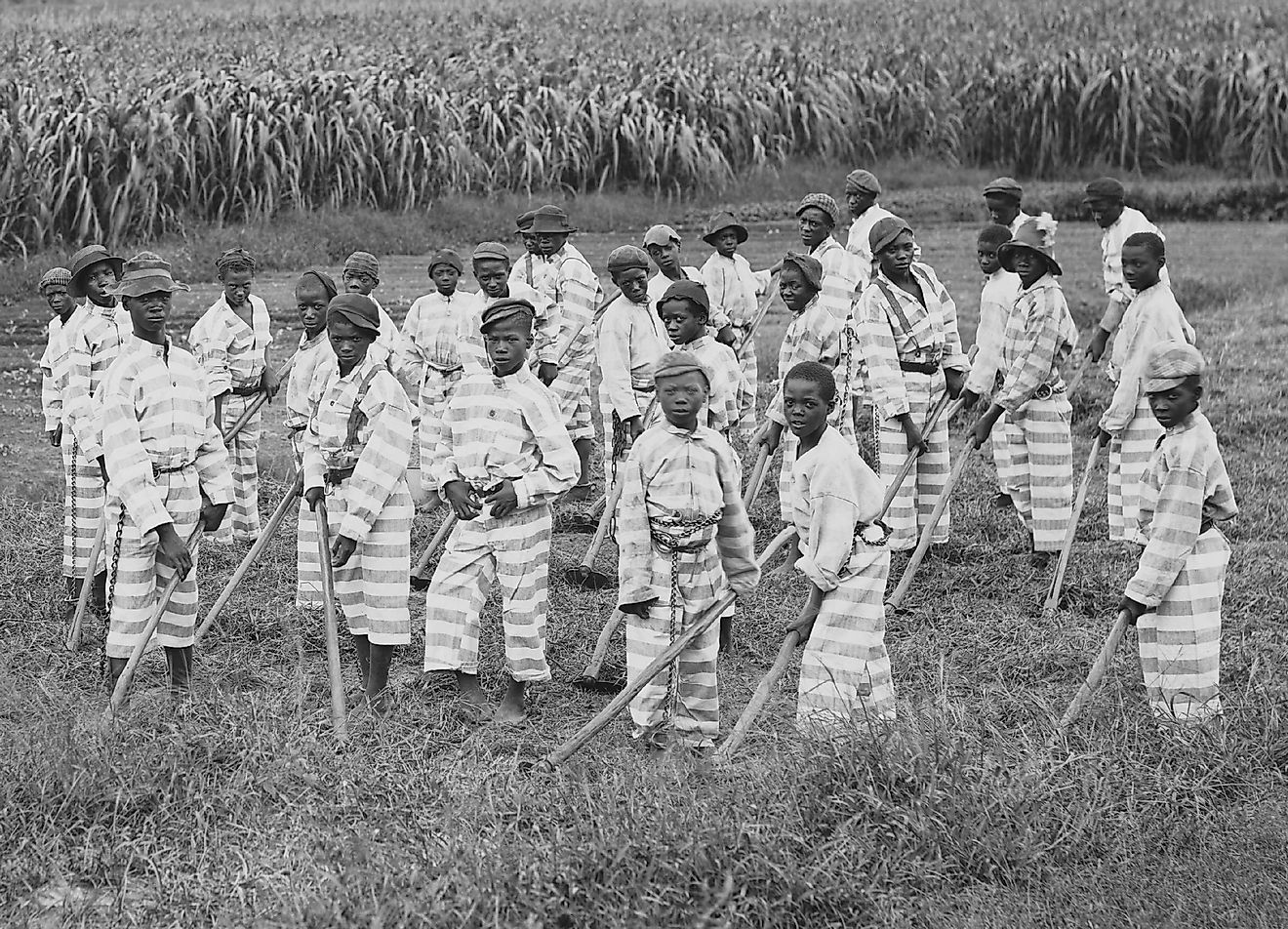

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

16 Political Values

Loek Halman is Associate Professor of Sociology at Tilburg University.

- Published: 02 September 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article discusses political values. The first section provides a working definition of the terms values and political values. This is followed by a discussion of old and new political values. The article also examines modernization and political value changes. The article ends with a section on critical and discontented citizens.

The empirical study of political values has gained momentum since Almond and Verba's (1963) seminal study on the Civic Culture . They introduced the concept of political culture to understand various political systems. They argued that in addition to the institutional and constitutional features of political systems, the political orientations of the individuals who constitute the political system are also relevant. Up to then, students of politics were mainly concerned “with the structure and function of political systems, institutions, and agencies, and their effects on public policy” (Almond and Verba 1963, 31) .

Almond and Verba's pioneering work redirected empirical enquiry from an exclusive preoccupation with institutions and structure and their concept of political culture bridged the gap between macro‐level politics and micro‐politics. “We would like to suggest that this relationship between attitudes and motivations of the discrete individuals who make up the political systems and the character and performance of political systems may be discovered systematically through concepts of political culture” (Almond and Verba 1963, 32) . The concept of political culture refers to “a particular pattern of orientations to political actions” (Pye 1973, 65–6) , and these orientations have major implications for the “way the political system operates—to its stability, effectiveness and so forth” (Almond and Verba 1963, 74) . Carol Pateman (1980) criticized this assumed relationship between people's orientations and political outcomes, arguing that it remained unclear how the values of people should affect the political system. Indeed, as Barry (1978) pointed out, political culture may better be viewed as the effect and not as the cause of political processes. A correlation between civic culture attitudes and democracy does not say anything about the causal chain. The presumption that a civic culture is conducive to democracy can also be interpreted the other way around, but such a conclusion would be less exiting, namely that “ ‘democracy’ produces the ‘civic culture’ ” (Barry 1978, 51–2) . However, Almond and Verba did not consider political culture as determining political structure, but they regarded them as interconnected, mutually dependent, and dynamically interacting. “Political culture is treated as both an independent and a dependent variable, as causing and as being caused by it” (Almond 1980, 29) . Beliefs, feelings, and values are the product as well as the cause of a political system.

The Civic Culture was one of the first empirical studies using the recently developed research technology “of sample surveys, which led to a much sharper specification and elaboration of the subjective dimensions of stable democratic politics” (Almond 1980, 22) . For the first time in history it was possible to “establish whether there were indeed distinctive nation ‘marks’ and national characters; whether and in what respects and degrees nations were divided into distinctive subcultures; whether social class, functional groups, and specific elites had distinctive orientations towards politics and public policy, and what role was played by what socialization agents in the development of these orientations” (Almond 1980, 15) .

The rise of the political culture concept during the 1950s and 1960s was part of the more general ascension of the idea that culture is a prominent explanatory power in the social sciences and history. “Culture was given causal efficacy as well as being caused and political culture … acquired the same traits” (Formisano 2001, 397 quoting Berkhofer) . As such, the recent emphasis on the importance of the cultural factor, and the growing awareness that culture in general and values in particular play an important role in human life is far from new. The idea that culture matters was prominent in Weber's intriguing work on the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism more than a century ago and earlier, de Tocqueville wrote about the importance of culture in his Democracy in America . During the 1940–50s, a rich literature was developed by scholars like Mead, Benedict, McCelland, Banfield, Inkeles, and Lipset, who regarded culture as “a crucial element in understanding societies, analyzing differences among them, and explaining their economic and political development” (Huntington 2000, xiv) .

However, during the 1960s and 1970s, interest in culture as a determining factor declined and rational choice theories became dominant. Following the logic of economics, social phenomena were explained as the result of rational calculations made by self‐interested individuals who aim at maximizing their own individual utility. Such theories claim that people anticipate the outcomes of alternative courses of action and then decide which of these alternatives will yield the best outcome for them. People choose the alternative that is likely to produce the greatest satisfaction.

In more recent years, interest in the cultural factor rose again, not in the last place because rational choice models appeared to have limited explanatory power, for example, to understand collective action (why do individuals join many groups and associations?), or to understand the survival of social norms such as altruism, reciprocity, and trust. Apparently people are not driven by a narrowly conceived self‐interest and thus are not purely rationally calculating and maximizing their own interests. The renaissance of culture as an important factor and the rediscovery of the cultural approach to politics can be seen as a way of counterbalancing the rational choice approach that dominated the sixties and seventies (Lane and Ersson 2005, 2) .

The cultural factor was also rediscovered because of the failure of economic factors to explain cross‐cultural differences and the differential trajectories of cultural changes over time. As Inglehart (1988, 1203) noted, “there is no question that economic factors are politically important, but they are only part of the story.” He referred to the importance of political attitudes, beliefs, orientations, preferences, and priorities that “have major political consequences, being closely linked to the viability of democratic institutions”. Culture was again regarded as an important source in human life and treated as a powerful active agent. As a proponent of this view, Wildavsky argued that people's basic orientations, their preferences, beliefs, and interests in particular should be taken into account. He stated, “I wish to make what people want [his italics]—their desires, preferences, values, ideals—into the central subject of our inquiry” because preferences “in regard to political objects are not external to political life; on the contrary, they constitute the very internal essence, the quintessence of politics: the construction and reconstruction of our lives together” (Wildavsky 1987, 5) .

The unexpected and rapid collapse of communist or socialist authoritarian regimes in central and eastern European countries and the rash unification of both Germanies have further triggered the idea that culture really matters. These events marked the end of the “Cold War” and evoked new or renewed contacts and relationships between East and West. Above all they “have drawn attention to the way regimes legitimate themselves and the way citizens identify themselves, both processes which suggest an important mediating role for culture” (Street 1994, 96) . Salient examples in this respect are of course the dramatic events that took place in Yugoslavia and many of the former Soviet countries. Such events are a sad illustration of what can happen when hidden forces and large differences in values within the collective consciousness of people explode into hatred and violence.

The importance of the cultural factor has also been demonstrated more recently in the European process of unification. The integration of nation‐states into one Europe has mainly been confined to the political and economic dimensions and this process is not welcomed with great enthusiasm by all Europeans. As soon as the cultural dimension is included, citizens become more reluctant regarding their support for Europe and the European ideal. Many people fear that a further European integration beyond economic and political cooperation undermines the role of the nation‐state and that “national” identities, habits, and cultures will slowly disappear. Recent analyses of data collected within the framework of the European Values Study suggest, however, that Europe is far from a cultural unity. European unity appears to be a unity of diversity. There remain significant differences in the basic value orientations of the Europeans ( Arts, Hagenaars, and Halman 2003 ; Arts and Halman 2004 ; Halman, Luijkx, and Van Zundert 2005 ). So it will be a demanding task of European leaders to ensure that the European project is in harmony with and reflection of the values of European citizens. That the European project is endangered from this cultural diversity is recognized. Recently, the President of the European Commission installed a reflection group on the Spiritual and Cultural Dimension of Europe. In their concluding remarks this group writes that “because an economic order never evolves in a value‐free environment … an effective and just economic order must also be embedded in the morals, customs, and expectations of human beings, as well as in their social institutions. So the manner in which the larger European economic area—the common market—is in harmony with the values of European citizens, as varied as these may be, is no mere academic problem; it is a fundamental and political one” (Biedenkopf, Geremek, and Michalski 2004, 7) .

The discussion on values is also triggered by the recent influx of migrant minorities and the multicultural society that is developing in many advanced industrial societies. These provoked in many European countries an open debate on the consequences of value diversity and what exactly comprises the cultural entity and identity of nation‐states. Also, the disappearance of internal borders between European Union member states, the demise of communism in the east, and the enlargement and further integration of the European Union in the center and the west have put the issues of identity and the survival of national cultures high on the European agenda. The European project seems to have awakened nationalistic sentiments and movements from their slumber and massive migration waves into Europe seem to have triggered exclusionist reactions toward new cultural and ethnic minorities and increased intercultural and interethnic conflict.

Apart from this, globalization of society makes sometimes painfully clear that people around the globe are not the same and adhere to very distinct values. Cultural conflicts over basic human values are frequently in the news and seem to confirm what Huntington predicted in his Clash of Civilizations . Major dividing lines in the contemporary world are defined by culture and no longer by ideological, economic, and political features. “In the post‐Cold War world, the most important distinctions among peoples are not ideological, political, or economic. They are cultural … The most important groupings of states are no longer the three blocs of the Cold War but rather the world's seven or eight major civilizations” (Huntington 1996, 21) .

The discussion of values is often fuelled by a growing preoccupation with the decline of values, in particular those values that make us good citizens and make society and human life good. “Widespread feelings of social mistrust, citizens turning away from prime institutions and political authorities, and engaging less in informal interactions are seen as indicators of the decline of the traditional civic ethic” ( Ester, Mohler, and Vinken 2006: 17 ; Bellah et al. 1992 ; Etzioni 1996 ; 2001 ; Fukuyama 2000 ; Putnam 2000 ; 2002 ). In the current, sometimes heated, debate, the discussion is not so much on the decline of values as such, but more on the decline of decent, (pro‐) social behavior. Many politicians and society watchers claim that a growing number of citizens is indifferent and skeptical about politics, and too narrowly focused on pure self‐interest. They consider this a severe threat for respect for human rights and human dignity, liberty, equality, and solidarity. In their view, the “good” values have declined or have even vanished and the wrong, “bad” values triumph in today's highly individualized society.

Major causes for this decline are found in modernization processes of individualization, secularization, and globalization that are assumed to have had severe consequences for the values, preferences, beliefs, and ideas that people adhere to. It is also in this vein that we look at political values and will decide on what old and new political values are. But before we enter into that discussion, it seems necessary to shed some light on the concept of values, for it remains unclear what values are. Therefore we start our discussion on old and new values with a short introduction of the concept of values in general and political values in particular.

1 What are Values and What are Political Values?

Since little theory has developed on values (Dietz and Stern 1995, 264) , the concept is not very clear. It is more or less a commonplace to state that values are hard to define properly. The sociological and psychological literature on the subject reveals a terminological jungle. To a large extent, this conceptual confusion is grounded in the nature of values. One obvious problem in (social) research is that values can only be postulated or inferred, because values, as such, are not visible or measurable directly. As a consequence, a value is a more or less open concept. There is no empirically grounded theory of values, which stimulated efforts to distinguish values from closely‐related concepts like attitudes, beliefs, opinions and and other orientations. The common notion, however, is that values are somehow more basic or more existential than these related concepts. Attitudes, for example, are considered to refer to a more restricted complex of objects and/or behaviors than values (Reich and Adcock 1976, 20) . This type of theoretical argument assumes a more or less hierarchical structure in which values are more basic than attitudes. “A value is seen to be a disposition of a person just like an attitude, but more basic than an attitude, often underlying it” (Rokeach 1968, 124) . The same applies to the relations between values and theoretical concepts such as norms, beliefs, opinions, and so on. Most social scientists agree that values are deeply rooted motivations or orientations guiding or explaining certain attitudes, norms, and opinions which, in turn, direct human action or at least part of it. Adhering to a specific value constitutes a disposition, or a propensity to act in a certain way ( Halman 1991, 27 ; Ester, Mohler, and Vinken 2006, 7 ; van Deth and Scarbrough 1995 ). Such a definition of values is a functional one and although it is more a description of what values do rather than what they actually are , it enables us to measure values as latent constructs, that can be observed indirectly, that is, in the way in which people evaluate states, activities, or outcomes.

Having made clear what values are, we need to define political values. Rokeach (1973, 25) argued that values can be classified in domains or institutional spheres. Accordingly, political values can be defined as the category of values that pertain to the political sphere. In line with our values concept, political values can be seen as the foundations of people's political behaviors such as voting and/or protesting or as Almond and Verba (1963) indicated, political values are people's orientations towards political objects. Hence, the individual's concrete political behavior can (at least partly) be explained from his or her political values or orientations. Thus, political values can be seen as perceptions of a desirable order (van Deth 1984) , and determining “whether a political situation or a political event is experienced as favorable or unfavorable, good or bad” (Inglehart and Klingemann 1979, 207) . Political values enable us to make political judgments.

2 Old and New?

It is not easy to decide what is old and new when it comes to values. If “old” means that certain values have been emphasized in the past, while “new” refers to the values that have more recently gained prominence, it remains a question if such a qualification makes sense. Old in the sense that in the past certain values were investigated does not mean that other values or orientations did not exist at that moment in time. It may simply mean that these other orientations were not an object of study because no one was interested in these orientations while in more contemporary settings such values have drawn attention and have become fashionable to focus on. For instance, a popular theme nowadays is sustainable development and many studies focus on issues of pollution, saving energy, climate changes, or water management. In times that the environment becomes an important issue, for whatever reason, environmental values come to the fore.

The distinction between old and new may be seen in terms of former versus contemporary, or in terms of traditional versus modern. Former values are those that have been recognized and focused on in the past, while “new” refers to orientations that have been identified recently and that dominate the current discourse. In that sense, “old” does not necessarily imply old and forgotten, but “old” would mean that these values have lost attention or have become less attractive to focus on, while “new” would apply to those values that match the emerging new issues and phenomena in contemporary society.

However, “old” and “new” in the sense of traditional versus modern may be understood in terms of changing values and shifting value adherences among populations. These value changes are linked to significant transformations of economic and social structures and the idea is that the values that prevailed during feudalism are not the same as those associated with industrialism or post‐industrialism. In such a view, the distinction between old and new is connected with the themes of modernization and post‐modernization. The traditional orientations stressing security, order, respect for authority, and conformity are considered to slowly shifting away whereas values stressing personal autonomy, individual freedom, self‐fulfillment, independence, and emancipation are assumed to be on the the rise ( Inglehart 1977 , 1990 , 1997 ; van Deth 1995 ).

Certain political values may turn out to be more resistant than others and have not vanished. Thus, in the Civic Culture , Almond and Verba identified a number of democratic attitudes that were already identified as important by de Tocqueville, and that are considered (again or still) highly relevant today. Such attitudes of trust, political partisanship, and societal involvement are key concepts of what is recognized as social capital, a notion that regained prominence since the recent works of Putnam, Fukuyama, and others.

3 Old Political Values?

Since the Enlightenment, liberalism was one of the dominant political forces. Socialism and social democracy are the two other classical ideological schools of thought which have dominated social and political behaviors of people and politics (see also Rush 1992, 190) . Classic themes in politics are of course freedom versus authoritarianism, equality versus inequality, the cleavage of labor and capital in society in general, and the class conflict in particular. It has become more or less common practice to classify political opinions on these issues in terms of left and right. The concepts of left and right are “generally seen as instruments that citizens can use to orient themselves in a complex political world” (Fuchs and Klingemann 1989, 203) ; they “summarize one's stands on the important political issues of the day. It serves the function of organizing and simplifying a complex political reality, providing an overall orientation toward a potentially limitless number of issues, political parties, and social groups. The pervasive use of the Left–Right concept throughout the years in Western political discourse testifies to its usefulness” (Inglehart 1990, 292–3) .

In the beginning left and right referred to the distinction between “the clergy (right) and the nobility (left)” (Nevitte and Gibbins 1990, 29) . With industrialization, the left–right continuum became associated with the cleavage of labor and capital in general and the class conflict in particular and the core issue in the left–right distinction became equality (Bobbio 1996, 60) . Left represents the part of society that stresses greater equality, whereas right is supportive of a “more or less hierarchical social order, and opposing change toward greater equality” (Lipset et al. 1954, 1135) . Both notions became increasingly associated with issues like the (re‐) distribution of income and wealth and the role of the government in the economy and society. “Left” favors a more just distribution of income and wealth and welcomes state intervention to achieve this, while “right” stresses the principles of a free market economy and independent individuals, and thus strongly favors a reduction of state control. Such cleavages between left and right are still highly relevant in today's society.

The polarization between left and right not only applies to political conflicts; the different outlooks also appear in all kinds of social, moral, and ethical issues, like abortion, euthanasia, nuclear energy, etc. Particularly the development of modern welfare states resulted in a growing number of social issues that are interpreted in terms of the left and right polarity, despite the fact that these issues are not associated with the traditional class conflicts. Issues like the quality of life, environment, nuclear energy, disarmament, foreigners, asylum seekers, and various moral issues have become important topics where left and right express fundamentally different views. Left is regarded to take the sides of the poor, the disadvantaged, the deprived, and minority groups; they are most concerned about the environment and opposed to nuclear energy and arms, and in moral issues left represents the liberal stances. Right is commonly seen as more restrictive and in favor of traditional standpoints. They are the strongest proponents of authority, order, maintaining the status quo, and a strong moral society.

Knutsen argues that the basic conflicts embedded in what he called old left–right were economic in nature, “referring in particular to the role of government in the economy” ( Knutsen 1995, 161 ; 2006, 115 ). These emerged particularly in industrial society. The main conflict centered around state control and improving equality versus freedom of enterprise and individual achievement. New dividing lines circle around conflicts emerging from advanced industrial and post‐industrial society and relate to conflicts between conservative moral and social beliefs versus individual and social freedom ( King 1987 ; Levitas 1986 ; Knutsen 1995 ; 2006 ).

Thus, also with regard to contemporary controversial issues, the left–right schema appears a useful tool to classify people's opinions. However, the left–right distinction is increasingly understood in terms of progressive versus conservative. For example, political parties, their adherents are often described in terms of left–right distinctions. It seems that an “old” concept has survived and can still be applied in contemporary society. In fact, the terms left and right remained popular in political discourse and in the mass media, but in political studies the interest in this left–right dimension appears to have declined.

4 New Political Values?

The main reason for the decreased interest in the left–right schema is the claim that a large number of new phenomena cannot be fitted into the ideological struggle between left and right. New issues have emerged on the political agenda and “the simple concepts ‘left’ and ‘right’ are too general for analyzing change in value orientations as between industrial and advanced industrial society” (van Deth 1995, 10) . Energy, the Cold War, the collapse of communism, the environment, sustainable development, welfare state, the European unification, globalization and internationalization, gay rights, equality for women, international migration, flows of refugees, became topics that increasingly needed serious attention, often resulting in new cleavages: the struggle between the sexes (men against women), active versus inactive people, the division of rich and poor countries, natives versus (im)migrants. These new topics that attracted widespread attention were not the core of the “old” traditional political ideologies that emerged from the French Revolution—that is, conservatism, liberalism and socialism. The old ideologies and traditional values lost their attractiveness and much of the political values inquiries focused on the value orientations that were connected with what is commonly denoted new politics. “New politics, various scholars argued, could only be understood as the reflection of new values” (Lane and Ersson 2005, 258) , which center around conflicts emerging from post‐industrial society and issues about the meaning of life in such a society (Knutsen 2006) . What values classify as new? An even more important question is why these new values have emerged?

The central values of old politics largely relate to economic growth, public order, national security, and traditional lifestyles, conformity, and authority, while the values of new politics emphasize individual freedom, social equality and in particular quality of life ( Inglehart 1977 , 1990 , 1999 ; and chapter in this volume). For Knutsen (2006) , both the materialist–postmaterialist value orientation and libertarian/authoritarian values can be regarded as value orientations associated with new politics. The materialist–postmaterialist dimension reflects the “shift from a preoccupation with physical sustenance and safety values towards a greater emphasis on belonging, self‐expression and quality of life issues” ( Knutsen 2006, 116 ; Inglehart 1977 , 1990 , 1997 ). Similarly, the libertarian‐authoritarian dimension distinguishes between an emphasis on “autonomy, openness, and self betterment” (Knutsen 2006, 116) on the libertarian side and “concerns for security and order, … respect for authority, discipline and dutifulness, patriotism, and intolerance for minorities, conformity to customs, and support for traditional religious and moral values” (Flanagan 1987, 1305) on the authoritarian side. The latter dimension reflects the shift of values from authoritarian to libertarian. More and more people turn away from traditions, the traditional authoritarian institutions, and the prescribed values and norms and increasingly they want to decide for themselves and determine on their own how to live their own lives.

Why have these modern orientations gained prominence? The answer can be found in the major social and political changes that gradually transformed society into postmodern society. There is widespread acceptance of the idea that modernization processes such as individualization, secularization, and globalization have had profound impact on people's (political) values.

5 Modernization and Political Value Changes

Most perspectives on value changes begin with the observation that there are fundamental qualitative differences between modern industrialized society and late modern, advanced industrial, postmodern society. Further, most perspectives link structural transformations to fundamental shifts in basic value orientations. As for the structural features, most advanced societies have recently experienced unprecedented increases in levels of affluence, growth of the tertiary economic sector at the cost of the first and secondary sectors, improving educational opportunities and rising levels of education, growing use of communication‐related technologies, and all have experienced what is known as the “information revolution”. Further, these changes resulted in expanding social welfare networks and increasing geographic, economic, and social mobility, specialization of job‐related knowledge, and professionalization.

These fundamental structural changes are related with or accompanied by a process in which individuals are increasingly able and willing to develop their own values and norms that do not necessarily correspond to the traditional, institutional (religious) ones. This process seems to be a universal (western) process that brings about not only more modern views, but also more diversity, and it is triggered and strongly pushed by rising levels of education of the population. More education increases people's “breadth of perspective” (Gabennesch 1972, 183) , their abilities and cognitive and political skills, which makes them more independent from the traditional suppliers of values, norms, and beliefs, and more open to new ideas and arguments, other providers of meanings, values, and norms. People's actions and behaviors are increasingly rooted in and legitimized by their own personal preferences, convictions, and goals. There is an unrestrained endeavor to pursue private needs and aspirations, resulting in assigning top priority to personal need fulfillment. Self‐development and personal happiness have become the ultimate criteria for individual actions and attitudes. Individualization thus entails a process in which opinions, beliefs, attitudes, and values grow to be matters of personal choice. As such, it denotes increasing levels of personal autonomy, self‐reliance, and an emphasis on individual freedom and the Self (Giddens 1991) . Individualized persons no longer take for granted the rules and prescriptions imposed by traditional institutions which means that the traditional options are less likely to be selected by an increasing number of people. This process of de‐traditionalization is characterized by a decline of traditional views in a variety of life domains. The “disciplined, self‐denying, and achievement‐oriented norms … are giving way to an increasingly broad latitude for individual choice of lifestyles and individual self‐expression” (Inglehart 1997, 28) .

People's values, beliefs, attitudes, and behavior are based increasingly on personal choice and are less dependent on tradition and social institutions. In other words, a process of privatization causes individual choices to be based increasingly on personal convictions and preferences. Waters (1994, 206) portrayed this as follows: “We may no longer be living under the aegis of an industrial or capitalist culture which can tell us what is true, right and beautiful, and also what our place is in the grand scheme, but under a chaotic, mass‐mediated, individual‐preference‐based culture of post‐modernity.” Voting, for instance “is no longer the confirmation of ‘belonging’ to a specific social group but becomes an individual choice …, an affirmation of a personal value system: the ‘issue voter’ tends to replace the traditional ‘party identification voter’ ” (Ignazi 1992, 4) . Since the saliency of ideology has diminished, the once strong ties between party and voter have weakened significantly. The modern voter has become an “issue voter” and politics has become “issue politics” which appears from the gradual shift that has occurred from membership of older style or traditional social movements, such as churches, ethnic groups, unions, or political parties towards membership of issue movements to protect or fight for certain causes, such as sexual liberties, feminism, environment, or even stopping the expansion of an airport or the building of a railroad or road (Barnes 1998, 122) . In modern or postmodern societies, old cleavages have disappeared, but increasingly new arenas of conflict have emerged, quite often related to concrete causes (Barnes 1998, 122) . Economic development increases this interest in new issues. Inglehart (1997) similarly maintains that economic development and the development of the modern welfare state has led to increasing interest in new issues dealing with the quality of life. People are less concerned with material wealth, and more and more concerned with the environment, emancipation, and personal interests. New groups and organizations will develop to protect these new interests.

The individual in advanced postmodern society also faces a multitude of alternatives as a consequence of internationalization, transnationalization, and globalization. Today's world is a “global village,” denoting that the world is a compressed one, and that the consciousness of the world as a whole has intensified tremendously (Robertson 1992, 8) . The globalization of social reality is a main effect of the rapid evolution of modern communication technology. Technological developments and innovations in telecommunications, the spread and popularity of computers, and also the increased mobility of major companies and people, as well as the growing exposure to television, radio, video and movies have intensified worldwide social relations and flows of information. In the modern world people encounter a great variety of alternative cultural habits and a broad range of lifestyles and modes of conduct. As such, globalization, “exhausted the old ideas, the traditional ideas, which had therefore lost their truth on the power to persuade” (Rush 1992, 187) . Globalization makes people aware of an expanding range of beliefs and moral convictions and thus with a plurality of choices. Because it has been argued that individualized and secularized people are liberated from the constraints imposed by traditional institutions (e.g. religion), globalization implies that people can pick and choose what they want from a global cultural marketplace. Globalization, thus, may be favorable to pluralism because people's choices are increasingly dependent upon personal convictions and preferences.

The emancipation of the individual, the growing emphasis on personal autonomy and individual freedom, the de‐unification of collective standards and the fragmentation of private pursuits seem advantageous to “a declining acceptance of the authority of hierarchical institutions, both political and non‐political” (Inglehart 1997, 15) . Thus, citizens are increasingly questioning the traditional sources of authority and no longer bound by common moral principles. From this, a society emerged where people are mainly concerned in their private matters and they feel no longer committed to the public case. As Fukuyama (2000, 14) says, “a culture of intense individualism … ends up being bereft of community.” The calculating citizen chooses to “bowl alone” and is increasingly disconnected from the once strong social ties. Because social responsibilities have declined and individual citizens are less embedded in associative relations, a process of deinstitutionalization has occurred appearing as weaker social bonds, people being detached from society, non‐affiliated, and without any loyalty to the wider community. Such a society is threatened by disintegration and the individual is threatened by anomie. Durkheim recognized this problem a long time ago, and, more recently, among others Fukuyama warned about the dangers of an individualized society. “A society dedicated to the constant upending of norms and rules in the name of increasing individual freedom of choice will find itself increasingly disorganized, atomized, isolated, and incapable of carrying out common goals and tasks” (Fukuyama 2000, 15) .

This unbridled pursuit of private goals and the erosion of collective community life concerns not only many politicians, but also many social scientists. The current debate on the future of citizenship and civil society is directed strongly towards the negative effects of these developments. Individual freedom is “held responsible for rising criminality, political apathy, lack of responsibility, hedonism and moral obtrusion” (Arts, Muffels, and ter Meulen 2001, 467) . Communitarians also have expressed their concern for the ultimate consequences of this development towards hedonism, privatism, consumerism, and the “I” culture. They fear a trend towards radical individualism and ethical relativism and the withdrawal of the individual from community life. The only way to solve the problem of individualistic, modern society is, according to proponents of the communitarian theories, the re‐establishment of a firm moral order in society by (re‐)creating a strong “we” feeling and the (re‐)establishment of a “spirit of community” (Etzioni 1996 ; 2001) . What present society needs, they argue, is “a strong moral voice speaking for and from a set of shared core values, that guides community members to pro‐social behavior” (Ester, Mohler, and Vinken 2006, 18) .

6 Critical and Discontented Citizens

Apart from pursuing their own interests, being disengaged, and disconnected, contemporary publics are said to be more critical (e.g. Norris 1999) . In advanced modern welfare state, people's basic needs are satisfied, which according to some resulted in rising levels of postmaterialism (cf. Inglehart 1997) , but which also resulted in increasing demands from citizens towards government. The unprecedented high levels of subjective well‐being and wide range of welfare state provisions for unemployment, income maintenance, health, housing, and old age allowed people to take survival and security for granted. Because they can take survival and security for granted, postmaterialist value priorities are rising. These values emphasize individual self‐expression and quality of life issues and these bring “new, more demanding standards to the evaluation of political life and confront political leaders with more active, articulate citizens” (Inglehart 1997, 297–8) .

The expanded role of the state to protect the individual's interest undermined private initiative and individual responsibility while welfare provisions are increasingly regarded as self‐evident and considered a right and entitlement. Unrestrained self‐interest makes people not only more demanding but also makes the demands more diverse. It becomes more and more difficult for the government to satisfy all these competing, conflicting, and incompatible demands and needs. The economic crisis has reduced the capacity of the state to guarantee social provisions for all people in society and satisfy their needs. In fact, most welfare states have turned into overloaded political economies, meaning that governments cannot meet both public and private claims. Increasingly there is what Dalton calls a representation gap: the differences between citizens preferences and government policy outputs (Dalton 2004, 66) . Such a gap between what people expect from their government and what the government can provide easily results in growing dissatisfaction, public doubts about government, widespread disillusionment with political representatives and political parties, and declining public support. The rise of support for extremist leaders and extremist political parties is often regarded to reflect these feelings of discomfort with government, the current policy, and governing parties.

The economic crisis, the reduction of social security, and the declining levels of public support not only threaten democracy, they also threaten humanitarian solidarity. Fuelled by the process of individualization which induces egocentric, hedonistic, individualistic, and consumeristic behavioral patterns, it is often assumed that cleavages emerge between the employed and unemployed, the older and young people, the sick and disabled versus the healthy people, and between natives and foreigners. Historical processes such as ongoing globalization, the collapse of communism, increasing rates of immigration, and the enlargement of the European Union have been the occasions of a revival of nationalist sentiments, the rise of racial discrimination and ethnic prejudice (Arts and Halman 2005) . These have become of great concern to national as well as European Community politicians. The ethnic conflicts in Russia and the Balkans, the increased support for extreme right‐wing political parties, the growing popularity among the young of racist and fascist movements in many European countries, and hostilities and assaults towards immigrants delineate major problems contemporary Europe has to cope with and seem to have rapidly fostered feelings of intolerance, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and nationalistic sentiments. Issues of ethnicity, identity, and nationalism have come to dominate European politics because they are considered to be the most explosive and divisive cleavages for the future of European integration (Berglund, Aarebrot, and Koralewicz 1995, 375) . Such diversities are regarded as important sources of miscommunication, misunderstandings, intolerance, polarization, intergroup conflict, and violence. The immigration flows are assumed to have triggered ethnocentric and xenophobic counteractions of not only extreme nationalists but also of established populations. If the latter would be the case, bitter cultural (and hence social and political) conflicts could come into being.

7 Conclusions

The aim of this article was to write about old and new political values put in context. It appeared difficult, not only to decide what values and thus what political values are, but also to define what is old and what is new in this regard. I argued that “old” should not be understood in terms of forgotten and vanished, but more in terms of traditional, while “new” should no be seen as values that are replacing the old ones, but denote values that prevail in contemporary society. Defined in such a way, old and new reflect the changes in values and value priorities. These changes are embedded in broader fundamental societal transformations that often are referred to as modernization of society.

The central claim of modernization theory is that contemporary, modern, post‐industrial society differs in many respects from traditional and industrial society, and political values are no longer grounded in political cleavages based on social class conflict but on cleavages based on cultural issues and quality of life concerns. Economic conflicts are likely to remain important, but they are increasingly sharing the stage with new issues that were almost invisible a generation ago: environmental protection, abortion, ethnic conflicts, women's issues, and gay and lesbian emancipation are heated issues today.

As a result, a new dimension of political conflict has become increasingly salient. It reflects a polarization between modern and postmodern issue preferences. This new dimension is distinct from the traditional left–right conflict over ownership of the means of production and distribution of income. A new political cleavage pits culturally conservative against change‐oriented progressive individuals, groups, and political parties.

The trajectories of modernization in general and processes of individualization, secularization, and globalization in particular, have transformed the value orientations and priorities in the political realm. In contemporary, highly individualized, secular and globalized order, the “grand world views” have become irrelevant for political orientation. The significance of traditional structures and ties, such as religion, family, class, has receded, enlarging the individual's freedom and autonomy in shaping personal life. People have gradually become self‐decisive and self‐reliant, no longer forced to accept the traditional authorities as taken for granted. The absoluteness of any kind of external authority, be it religious or secular, has eroded. Authority becomes internalized and deference to authority pervasively declined (Inglehart 1999) .

The unrestrained striving to realize personal desires and aspirations, giving priority to individual freedom and autonomy and the emphasis on personal need fulfillment are assumed to have made contemporary individualized people mainly interested in their own lucrative careers and devoting their lives to conspicuous consumption, immediate gratification, personal happiness, success, and achievement. Such people neglect the public interests and civic commitment to the common good is eroding. Evidence of this development is found in increasing crime rates, marital breakdowns, drug abuse, suicide, tax evasion, and other deviant behaviors and practices and the increasing disconnection from family, friends, neighbors, and social structures, such as the church, recreation clubs, political parties, and even bowling leagues (Putnam 2000) . Because civic virtues, such as trust, social engagement, and solidarity are on the decline, and since these virtues are considered basic requirement for democracy to survive or to work properly (Putnam 1993) , contemporary society suffers a democratic deficit. Democracy is endangered because people are less and less inclined to engage in civic actions.

In Europe, the further integration and intended enlargement of the European Union have fuelled nationalistic sentiments and movements. The recent migration waves into Europe have advanced exclusionist reactions toward new cultural and ethnic minorities and fostered intercultural and interethnic conflicts. These gave rise to new and acute cultural cleavages; and it is precisely because the nations of Europe have failed to become genuine melting pots that so much of European politics now revolves around issues of multiculturalism. Not perpetual peace but nationalist, ethnic, and religious conflicts will occur. So, the ghosts of the past, such as nationalism and racial or religious struggle, still haunt Europe's darker corners, reappear everywhere. In this respect one could speak about the “return of history” ( Joffe 1992 ; Rothschild 1999 ) for European history is a story of conflicts. Such issues generated interest in and studies on multicultural society (European and multiple) identity, tolerance, and patriotic, nationalistic, ethnocentric, and xenophobic attitudes.

Such orientations are far from new and have been studied before extensively. For example, Stouffer's (1955) classic study of tolerance in America dates back to the fifties, while Sumner (1906/1959) introduced the term ethnocentrism already early in the twentieth century (also see chapter in this volume by Gibson). The question therefore is whether such orientations classify as “new” or “old.” It seems better to conclude that there is a renewed interest in such orientations. The same counts for attitudes of trust, civic actions, and societal involvement. Such orientations were already identified as important for democracy in the Civic Culture by Almond and Verba (1963) . Again, there is nothing really new under the sun. The types of issues that are most salient in the politics of the societies define the values at that moment.

Thus, it seems that it does not make much sense to define and distinguish old and new political values. Old orientations are not replaced by new ones, but value orientations are changing as a result of the transformations of society and modernization processes like individualization, secularization, and globalization. People in modern post‐industrial society are no longer constrained in their choices and they favor personal autonomy, individual freedom, and self‐direction, quality of life, and the pursuit of subjective well‐being. This centrality of the individual generated the rise of values such as emancipation, self‐expression, postmaterialism, gender equality, environmentalism, feminism, and ecologism etc. As van Deth (1995, 8) concluded, these new orientations have risen in addition to traditional value orientations.

Almond, G. A. 1980 . The intellectual history of the civic culture concept. Pp. 1–26 in The Civic Culture Revisited , ed. G. A. Almond and S. Verba . Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

—— and Verba, S. 1963 . The Civic Culture . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arts, W. , Hagenaars, J. , and Halman, L. eds. 2003 . The Cultural Diversity of European Unity . Leiden: Brill.

—— and Halman, L. eds. 2004 . European Values at the Turn of the Millennium . Leiden: Brill.

—— —— 2005 . National identity in Europe today. International Journal of Sociology , 35: 69–93. 10.2753/IJS0020-7659350404

—— Muffels, R. , and ter Meulen, R. 2001 . Epilogue: the Future of solidaristic health and social care in Europe. Pp. 473–7 in Solidarity in Health and Social Care in Europe , ed. R. ter Meulen , W. Arts , and R. Muffels . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Barnes, S. H. 1998 . The mobilization of political identity in new democracies. Pp. 117–38 in, The Postcommunist Citizen , ed. S. H. Barnes and J. Simon Budapest: Erasmus Foundation and IPAS of HAS.

Barry, B. 1978 . Sociologists, Economists, and Democracy . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bellah, R. N. , Madsen, R. , Sullivan, W. M. , Swidler, A. , and Tipton, S. M. 1992 . The Good Society . New York: Vintage Books.

Berglund, S. , Aarebrot, F. , and Koralewicz, J. 1995 . The view from EFTA. Pp. 368–401 in Public Opinion and Internationalized Governance , ed. O. Niedermayer and R. Sinnott . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biedenkopf, K. , Geremek, B. , and Michalski, K. 2004 . The Spiritual and Cultural Dimension of Europe . Vienna/Brussels: Institute for Human Sciences and European Commission.

Bobbio, N. 1996 . Left & Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dalton, R. J. 2004 . Democratic Challenges: Democratic Choices . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001

Dietz, T. , and Stern, P. C. 1995 . Toward a theory of choice: socially embedded preference construction. Journal of Socio‐Economics , 24: 261–79.

Ester, P. , Mohler, P. , and Vinken, H. 2006 . Values and the social sciences: a global world of global values? Pp. 3–29 in Globalization, Value Change, and Generations , ed. P. Ester , M. Braun , and P. Mohler . Leiden: Brill.

Etzioni, A. 1996 . The New Golden Rule: Community and Morality in a Democratic Society . New York: Basic Books.

—— 2001 . The Monochrome Society . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Flanagan, S. C. 1982 . Changing values in advanced industrial societies: Inglehart's silent revolution from the perspective of Japanese findings. Comparative Political Studies , 14: 403–44. 10.1177/0010414082014004001

—— 1987 . Value changes in industrial societies. American Political Science Review , 81: 1303–19.

Formisano, R. P. 2001 . The concept of political culture. Journal of Interdisciplinary History , 31: 393–426. 10.1162/002219500551596

Fuchs, D. , and Klingemann, H. D. 1989 . The left–right schema. Pp. 203–34 in Continuities in Political Action , ed. J. W. van Deth and M. K. Jennings . Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Fukuyama, F. 2000 . The Great Disruption . New York: Touchstone.

Gabennesch, H. 1972 . Authoritarianism as world view. American Journal of Sociology , 77: 857–75. 10.1086/225228

Giddens, A. 1991 . Modernity and Self‐Identity . Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Halman, L. 1991 . Waarden in de Westerse wereld . Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

—— Luijkx, R. and van Zundert, M. 2005 . Atlas of European Values . Leiden: Brill.

Huntington, S. P. 1996 . The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order . New York: Simon & Schuster.

—— 2000 . Cultures Count. Pp. xiii–xvi in Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress , ed. L. E. Harrison and S. P. Huntington . New York: Basic Books.

Ignazi, P. 1992 . The silent counter‐revolution: hypotheses on the emergence of extreme right‐wing parties in Europe. Pp. 3–34 in, European Journal of Political Research, Special Issue: Extreme Right‐Wing Parties in Europe , ed. P. Ignazi & C. Ysmal . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Inglehart, R. 1977 . The Silent Revolution . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—— 1988 . The renaissance of political culture. American Political Science Review , 82: 1203–30. 10.2307/1961756

—— 1990 . Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—— 1997 . Modernization and Postmodernization . Princeton: Princeton Universy Press.

—— 1999 . Postmodernization erodes respect for authority, but increases support for democracy. Pp. 236–56 in Critical Citizens , ed. P. Norris . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/0198295685.003.0012

—— and Klingemann, H. D. 1979 . Ideological conceptualization and value priorities. Pp. 203–14 in Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies , ed. S. M. Barnes , M. Kaase , et al. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

Joffe, J. 1992 . The new Europe: yesterday's ghosts. Foreign Affairs , 72: 29–43.

King, D. S. 1987 . The New Right: Politics, Markets and Citizenship . Basingstoke: Macmillan Education Ltd.

Knutsen, O. 1995 . Left‐right materialist value orientations. Pp. 160–96 in, The Impact of Values , ed. J. W. van Deth and E. Scarbrough . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—— 2006 . The end of traditional political values?. Pp. 115–50 in Globalization, Value Change, and Generations , ed. P. Ester , M. Braun and P. Mohler . Leiden: Brill.

Lane, J.‐E. , and Ersson, S. 2005 . Culture and Politics . Aldershot: Ashgate.

Levitas, R. ed. 1986 . The Ideology of the New Right . Oxford: Polity Press.

Lipset, S. M. , Lazarsfeld, P. F. Barton, A. H. , and Linz, J. 1954 . The psychology of voting: an analysis of political behavior. Pp. 1124–76 in The Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. II , ed. G. Lindzey and A. H. Barton . Reading, Mass.: Addison‐Wesley.

Nevitte, N. , and Gibbins, R. 1990 . New Elites in Old States: Ideologies in the Anglo‐American Democracies . Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. ed. 1999 . Critical Citizens . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/0198295685.001.0001

Pateman, C. 1980 . The civic culture: a philosophic critique. Pp. 57–102 in The Civic Culture Revisited , ed. G. A. Almond and S. Verba . Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

Putnam, R. 1993 . Making Democracy Work . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—— 2000 . Bowling Alone . New York: Simon & Schuster.

—— ed. 2002 . Democracies in Flux . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/0195150899.001.0001